Huifeng 2014

Transcript of Huifeng 2014

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

1/54

Shi h uifeng : Dependent Origination = EmptinessNgrjunas Innovation?

1

Dependent Origination = EmptinessNgrjunas Innovation?

An Examination of the Early andMainstream Sectarian Textual Sources

Shh ifng

Abstract

It is claimed that one of the innovative contributions of Ngrjunain his Madhyamaka thought was establishing the equivalence ofemptiness (P:suat, Skt: nyat; kng , kngxng ) anddependent origination (P: paicca samuppda, Skt: prattya samutpda;Ch: ynyn , ynq ). This study examines early andmainstream Buddhist textual sources to discover what relationshipbetween emptiness and dependent origination was established beforeNgrjuna.

In Part 1, we broadly outline the near paradigmatic modern Buddhiststudies discourse on the teachings of emptiness. We then focus on therole of Ngrjunas Madhyamaka within this discourse. Lastly, thisstudy rounds o with a literature review of studies on emptiness anddependent origination before Ngrjuna.

Part 2 covers the early teachings found in the Pli Nikya s and(Chinese translations of) the gama s. It nds that the term emptinesswas sometimes used independently to refer to the process of dependentarising assasric dissatisfaction and cause, and also as dependentcessation intonirva. Emptiness as the profound also describedthese two complementary processes as a whole.

Part 3 continues with the broad range of mainstream sectarianstra and stra literature. Here, the previous relationships are made more

rm and explicit. There is greater association with the two doctrines asrejection of extreme views based on a self. The two are also broughtwithin the Abhidharma methodology of analysis into conventional

x H x H v bH XXXY_]

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

2/54

JCBSSL VOL. XI

2

or ultimate truths, and classi cation as conditioned or unconditionedphenomena.

Part 4 concludes, that while already nascent in the early literature, therelation or equation of emptiness with dependent origination, alongwith related terms, was quite well developed in pre-Ngrjuniansectarian literature, and is strongest in the Sarvstivdin literature.We recommend that aspects of the academic discourse on emptinessshould be recti ed as a result of these ndings.

Keywords: emptiness, dependent origination, Ngrjuna,Madhyamaka, early Buddhism, sectarian Buddhism

x H x H v bH XXXY_

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

3/54

Shi h uifeng : Dependent Origination = EmptinessNgrjunas Innovation?

3

1. Emptiness, Dependent Origination & Ngrjuna

Modern Buddhist studies has an already established academic

discourse and narrative with regard to the teaching of the emptyor emptiness (P:sua, suat, Skt:nya, nyat; Ch: kng /kngxng ). Although this general position on emptiness is seldomstated as a discourse or narrative, and is moreover not a positionheld universally by all scholars, it is nonetheless fairly common, adefault position as it were. The fact of the lack of need to express itas an academic discourse or narrative is perhaps further indication ofits paradigmatic status. Its lines of development and argument often

begin from middle to late Mahyna, and then work backwards throughhistory showing how each stage di ered from the previous. This isbecause it tends to (quite erroneously) argue that emptiness is largelya Mahyna doctrine. This form of teleological approach, wherebyearlier forms are only investigated in as much as they are relevant forlater forms, obviously leads to numerous distortions.

Here, however, we shall use the more natural diachronic presentationin a natural forward historical sequence, noting some of the modernscholars who support the respective elements of the discourse:1. It is stated thatearly Buddhism as found in the Nikyas and gamas

also did not consider the doctrine of emptiness as particularlyimportant.1.1. Time period is from the Buddha to the schism of the Sagha,

approximately 5th to 3rd centurybce .1.2. More often than not, thesutta (and to a much lesser extent the

vinaya) canon of thePli Theravdin tradition alone is used torepresent the doctrines of early Buddhism.1.3. What little early Buddhism so de ned does say regards

emptiness, is by and large merely a synonym for not self.2. Slightly later, mainstream sectarian Buddhism, as typi ed by the

Abhi dharma, referred to with the polemic term Hnayna, alsodid not consider the teaching of emptiness as particularly important.2.1. The alleged time period is from the schism of the Sagha to

the dominance of the Mahyna, approximately 3rd centurybce to 2nd centuryce .

x H x H v bH XXXY__

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

4/54

JCBSSL VOL. XI

4

2.2. It is shown that the Abhidharma dharmavdasystem considersphenomena as a plurality of really existent entities. Althoughrejecting a self (tman) in the person ( pudgala ), known as pudgala nairtmya or pudgala nyat, they considered thedharmas to in fact exist.

2.3. The Northern Abhidharma koa and SouthernVisuddhimaggaare perhaps the most commonly referred to texts of this period,despite their providence of c. 5th cty , quite some centuriesafter the advent of the Mahyna.

3. In contradistinction to the above two historical stages, the notion

of emptiness is an extremely important doctrine in MahynaBuddhism, especially the Prajpramit.3.1. Spans from the turn of the millennia 0ce on, for several

centuries.3.2. As opposed to the Hnayna view espoused above, it is

claimed that the Mahyna notion of emptiness encompassesboth the emptiness of the person ( pudgala nyat, pudgala-nairtmya) and also the emptiness of the phenomenal

(dharmanyat, dharmanairtmya).3.3. This is considered at least a direct refutation against the Abhidharma systems, if not mainstream sectarian Buddhism

as a whole.3.4. Standard explanations of thePrajpramit Sutras are

often based on much later Indian commentaries which havebeen preserved in Sanskrit and Tibetan, particularly the

Abhisamaylakrloka of Haribhadra.

4. The de nitive Mahynic meaning of emptiness is usually sourcedfrom the Madhyamaka texts of Ngrjuna and his doctrinal heirs.4.1. From the time of Ngrjuna, 2nd to 3rd centuryce .4.2. Sometimes Ngrjuna is given the status of a founder or

inspiration for the Mahyna as a whole, or at least its principalsystematizer.

4.3. In particular, Ngrjunas seminal text, the Mlamadhymaka-krik, is taken as de nitive, if not exclusively.

4.4. Often his expression of emptiness is considered revolutionarywhen compared to the realist or substantialist positions of

Abhidhamma Buddhism, or more speci cally, the teachings of

x H x H v bH XXXY_

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

5/54

Shi h uifeng : Dependent Origination = EmptinessNgrjunas Innovation?

5

the Pudgalavdins and the Abhidharma of the Sarvstivda.This was the emptiness doctrine (nyatvda) against theown-nature doctrine (svabhvavda). Some consider theearly teachings to also be his target.

4.5. Later commentaries on the Mlamadhyamakakrik,especially those preserved in Sanskrit and Tibetan, such asCandrakrti, are used to explain Ngrjunas keystra in turn.

5. It is commonly said that Ngrjuna received the inspiration for hisformulation on emptiness from thePraj pramit Stra s.5.1. The relationship between thesestras andstras is sometimes

explained as Ngrjunas Madhyamaka emptiness being asystematic philosophical expression of thePraj pramitStras religious teaching of emptiness.

It was mainly a number of earlier studies, by the likes ofMurti (1955),Stcher batSky (1968) andc onze (1962), who rst established thismodern discourse of emptiness through detailed scholastic studiesfocusing on the source materials available at the time. Recently,WeSterhoff has provided a survey of The Philosophical Study ofNgrjuna in the West, laying out three phases: First is the Kantianphase, then the analytic phase, and nally a post-Wittgensteinian one(WeSterhoff 2009: 9 ). It is noteworthy thatStcherbatSky andMurti ,for instance, fall within the Kantian phase, and thatc onze has strongHegelian credentials. The above discourse is an outline of some of thekey points, as exempli ed in major writings by a number of Buddhiststudies scholars, far too many to list individually here.

For now, we would like to point out that as a whole, the discourse ofemptiness so established is a very useful general outline which mayserve as is when laying out the broad picture of the development ofIndian Buddhist thought. However, it is not without some problems.Over the last few decades, several scholars have shown more nuancedapproaches and proposed amendments to various parts of the discourse,which are worth noting.

1.1. Ngrjunas Madhyamaka as Emptiness and Dependent OriginationWe shall not here attempt to discuss the discourse on emptinessin its entirety, which would be a huge project encompassing much

x H x H v bH XXXY_a

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

6/54

JCBSSL VOL. XI

6

of Buddhism in India and beyond. However, we would like to drawattention to certain aspects of it, which while being commonly acceptedas paradigmatic, are still nonetheless somewhat problematic. Of the vemain elements of the discourse outlined above, we would like to re ecton the general position of Ngrjunas Madhyamaka. In the last fewyears a number of excellent studies in this area have been published,such as those byWeSterhoff (2009), Seyfort r uegg (2010) andSideritS & katSura (2013). However, focusing mainly on Ngrjunasphilosophy, rather than as historical development of Buddhist thought,the Madhyamaka role within the broader discourse is only brie ytouched upon. But despite the progress in nding more appropriateways to read and understand Ngrjuna, in particular his Mla-madhyamakakrik, certain approaches have remained unchanged.Candrakrti, for example, remains the default commentator of choice,and the use of Tibetan sources far exceeds that of the Chinese sources(see Discourse point 4.5). More importantly for our essay here, is thecontinued great emphasis placed uponKrik verse 24:18:

y prattyasamutpda nyat t pracakmahe|s prajaptir updya pratipat saiva madhyam||

That dependent origination, we declare it is emptiness; It isdesignation on a basis, it is indeed the middle way.

With emptiness already the accepted core of Ngrjunas Madhyamakathought, this verse now directly associates emptiness with dependentorigination (P: paicca samuppda, Skt: prattya samutpda; Ch:ynyn , ynq ). A large number of scholars indicate

that this verse was not only crucial for a number of classic Buddhisttraditions, but also themselves continue to consider it as central to thetext itself. For example,g arfield states that It is generally, and in myview correctly, acknowledged that chapter 24, the examination of theFour Noble Truths, is the central chapter of the text and the climax ofthe argument (g arfield 2002: 26). Similar claims have been madeby k alupahana (1986: 28f, 31-7),g arfield (1994; 2002: 69-85),WeSterhoff (2009: 91-127), andSideritS & katSura (2013: 13 ),among others. The four noble truths are themselves alocus classicus ofthe principle of dependent arising. The import of this fundamental lawof arising in dependence is further strengthened with reference to thevery opening verses of theKriks, which state:

x H x H v bH XXXY X

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

7/54

Shi h uifeng : Dependent Origination = EmptinessNgrjunas Innovation?

7

anirodham anutpdam anucchedam avatam|anekrtham annrtham angamam anirgamam||

ya prattyasamutpda prapacopaama ivam|deaymsa sabuddhas tavande vadat varam||

I prostrate to the fully awakened one, the best of speakers,who has taught dependent origination, the appeasement ofconceptual proliferation, the auspicious, which is not cessation,not production, not annihilation, not eternalism, not singularity,not plurality, not coming, not going.

As such, the two aspects, namely emptiness and dependent origination,as well as the relationship or even equivalence between them, havelong been considered by most scholars to be of central concern forNgrjuna and the Madhyamaka as a whole. Again, we see this attitudein a large number of studies, such as those ofk alupahana (1986: 28f,31-7);g arfield (1994; 2002: 69-85);WeSterhoff (2009: 91-127); andSideritS & katSura (2013: 13 ).

The discourse on emptiness has largely given thePraj pramit Stra s

as the source of Ngrjunas teachings on emptiness, though much lessso for dependent arising (see Discourse point 5). This naturally ttedwith his status as one of the founders of the Mahyna and a numberof its philosophical systems, not just the Madhyamaka. In tting withthe classical Mahyna vs Hnayna polemic, it was not only thoughtthat his teachings on emptiness (and dependent origination) were notderived from the so-called Hnayna sources, but must be in activeopposition to them (see Discourse point 4.4).

This notion has been challenged in the last decades, with severalscholars rst questioning the Mahyna status of either Ngrjunahimself, or of theKriks. The citation of the Nikya and gama teaching to Katyyana in NgrjunasKriks 15:7 is well known (eg.k alupahana 1991: 232 ;SideritS & katSura 2013: 159 ). Severaldecades ago,Warder heralded a change in English language studieswhen he challenged this fundamental assumption, asking Is Ngrjunaa Mahynist? (Warder 1973). Later, he stated the accepted tradition,yet pointed out the fact of the Mlamadhyamaka Krik as referencingonly Tripiaka materials (Warder 1998: 138). Others have sincefollowed or countered this thesis. However, over half a century ago

x H x H v bH XXXY Y

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

8/54

JCBSSL VOL. XI

8

in China,y nShn had already considered that Ngrjunas seminalwork was written based on the gama s, not Mahyna stras. In theintroduction to his book An Investigation into Emptiness(Kng zhtnju ), y nShn re ected on statements that he had madedecades beforeWarder and others (1985: i; cf.y nShn 1949: 18, 24):

In the last few years, when I was reading thePrajpramitStras for writing my bookThe Origins and Development ofEarly Mahyna Buddhism [1980], I thought of my views in

Modern Discussion on the Madhyamaka over thirty years before[1949]: The*Madhyamaka strais a treatise to elucidate the

gama s; and the*Madhyamaka stratakes the perspective ofthe Mahyna scholars and selectively develops the profoundmeaning of dependent origination in the gama s, and rmlyestablishes the right view of (Mahyna) Buddha Dharma onthe key-stone of dependent origination, the middle way.

This pithy summary again highlights scholars perceived relationshipbetween emptiness and dependent origination in Ngrjunas thought,in particular verse 24:18. Since such recent revisions, some e orts

have been made to seek sources for Ngrjunas thought from earliersources. However, as our outline of the discourse shows, these havesometimes been fraught with source bias issues, in both the earlyBuddhism and mainstream sectarian Buddhism periods.

Most studies and conclusions regarding early Buddhism rely solelyon the Pli canon of the Theravda, and seldom investigate the gama s.ThePliTheravda here referred to is that of the r Lankan Mahvihra,

located some distance from the central lands of Gagetic North India.Seldom are the gama s of other schools used, such as those Chinesetranslations of gama s from the Sarvstivda, the Dharmagupta andMahsaghika.y nShn (1985) andc hoong (1999) are exceptionshere, thoughl aMotte (2001) also makes mention of gama sources.Given the relative dominance of the latter schools in mainstream IndianBuddhism, their texts and doctrines are more relevant to the greaterpicture of mainstream Indic Buddhist, whereas the Theravda wasgeographically more removed. Yet even using these Nikya s or gama soutright is problematic, for they belong to a given Buddhist mainstreamschool. The issue of using these to identify early Buddhism, if not theteachings of the historical Buddha himself, or even a representation

x H x H v bH XXXY Z

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

9/54

Shi h uifeng : Dependent Origination = EmptinessNgrjunas Innovation?

9

of those teachings and tenets held before the various schools split apart,is a very complex and di cult matter.

As for such problems in early Buddhism, likewise too for themainstream period Abhi dharma and commentarial literature. Oftenit is the 5th cty Visuddhimagga of Buddhaghosa and Vasubandhus5th cty Abhidharma koa and Bhya which are cited as representingthe non-Mahyna traditions. But neither the Northern or Southern

Abhidharma traditions began as the alleged fully edged rei ed orsubstantialist positions that may be found in these two works. Thesubstantialist theories which are the supposed target of the Mahynaaccording to the discourse on emptiness only reached this state perhapseven after the early Mahyna and Praj pramit around the turn ofthe millennium was established. How can one anachronistically arguethat the earlierPraj pramit and / or Madhyamaka is a refutationor reaction against later Abhidharma substantialism, when the sourcescited have such an historical relationship? Another important point isthat such Abhidharma theories, in either early or later form, do notrepresent the entirety of pre- and non-Mahyna Buddhist thought.The Theravda and Sarvstivda were originally closely related asSthavra schools, and likewise too, the Pudgalavdins. The plethora ofschools at this time period show a huge range of positions on a widerange of subjects. This includes Mahsghika in uenced works suchas the*Satyasiddhi stra, and other non- Mahyna content from the

Mah praj pramit Upadea (seey nShn 1985: 132f; 92 ).

By studying the precedents to Ngrjunas Madhyamaka thought

with these problems unresolved, it is little wonder that claims ofrevolutionary thought and innovation are made with respect to histeachings on emptiness and dependent arising. But as we have shown,for examining these ideas in both early and mainstream Buddhism,the Pli canon alone will simply not su ce, even if their Abhidhamma and commentarial texts are included, nor will the Abhidharma koa assole representative of the Northern traditions. A deeper understandingof the teaching of emptiness across a broad range of mainstreamschools is required. For this, the large number of Chinese sources needbe utilized to their full extent. Moreover, closer care to the historicalsequence and relationships of texts and doctrines is essential. Only thenwill we be in a position to ascertain the signi cance of Ngrjunas

x H x H v bH XXXY [

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

10/54

JCBSSL VOL. XI

10

Madhyamaka teachings on emptiness and dependent origination as astage of Buddhist doctrinal development within their own historicalcontext.

1.2. Literature ReviewDespite the aforementioned problems of source biases and anachronisms,even sole use of the Pli canon is already su cient to show that emptyand emptiness were not rst coined by the Mahyna, or Ngrjuna.One of the earliest demonstrations of this can be seen ink arunaratne ,who as per the academic discourse equated early Buddhist emptiness

with absence of self or what pertains to self (1956, 1988: 169). Whilewritten in 1956, which would have made it a perfect foil forMurti asmuch as againstStcherbatSky s earlier writings, this was unfortunatelyonly published in 1988. As such, it has been largely overlooked.

For early Buddhism, also working exclusively from the Pli sourcesfor emptiness in early Buddhism, we also have shorter essays suchas g Mez s Proto-Mdhyamika in the Pli Canon (1976), andVlez de c eas Emptiness in the Pli Suttas and the Question of NgrjunasOrthodoxy (2005), both of which show scholars great interest inNgrjunas Madhyamaka. They largely take emptiness as a philosophy,rather than as a matter of meditation, which is the main feature ofemptiness in the early texts (seec hoong 1999: 43-84;y nShn 1985:1-78). Though these attempts to trace earlier sources and contexts forNgrjuna are commendable, by relying only on the Pli canon andneglecting other schools contemporary with it, the results are limited.In the end, thoughVlez de c ea very clearly sees the problems ofmodern scholarship in this area, he really only shows that Ngrjunawould probably not disagree with some basic tenets of the Nikya sand gama s. This would be greatly assisted by broadening the sourcematerial from which comparisons are made.

One of the few more comprehensive studies in English directly relatedto emptiness in early Buddhism isThe Notion of Emptiness in Early

Buddhism , byc hoong (1999). Although the title explicitly states early

Buddhism as the scope, he curiously states in his aims that he shallargue that the teaching of emptiness is not a creation of early Mahyna,but that it has clear antecedents in early Buddhism, and his very last

x H x H v bH XXXY

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

11/54

Shi h uifeng : Dependent Origination = EmptinessNgrjunas Innovation?

11

words on the matter are: emptiness is genuinely a teaching ofthe Buddha himself, and not simply a creation of the Mahyna (pg.2, 88). It has rather the tone of a Mahyna apologetic in the face ofmodern Buddhist studies text-historical criticisms.

Another, di erent kind of apologetic, is found ind haMMajothi sThe Concept of Emptiness in Pli Literature (2008), which seeks toexamine the relation between the concept ofsua in early Buddhismand emptiness in Madhyamaka (pg. iii). He appears to wish to de ectthe criticisms of Ngrjuna and others away from the Theravda, andtowards other mainstream groups (pg. iii, 163). However, again, dueto being specially focused on the PliTipiaka, and theVisuddhi-magga (pg. iii; pp. 100-120), this quite disorganized study can only beseen as representing the Theravda, and neither early Buddhism orthe entirety of mainstream Buddhism. Thus, while the author wishesto de ect Madhyamaka criticisms against the Theravdin tradition,those same criticisms remained unexamined as to their true target andprecedents, and the Hnayna bogeyman remains hidden.

It is to be admitted, lamentably, that there are even fewer systematic anddedicated studies into the doctrine of emptiness within the mainstreamBuddhist period. This in turn re ects the general status of studies inthis period, wherein there has been little research into speci c doctrinalissues. However, let us examine these few relevant studies in order.

Given the supposed Mahyna vs Hnayna polemical claims onemptiness within the discourse, it is not at all surprising that there

are even fewer studies on this topic centered on mainstream sectarianmaterial (source biases aside). In one of the many sub-essays withinhis epic ve volume translation of the Mah praj pramit Upadea (Dzhd ln ), l aMotte breaks the main stream Buddhistschools into three types: 1. The personalists, such as the Pudgala-vdin Vtsputryas and Samittyas; 2. The realists, namely theTheravda and Sarvstivda bhidharmika s; and 3. The nominalists,for instance, the Mahsghika Prajaptivdins, and possibly non-

Abhidharma Sthavira groups. Concerning their respective positionson emptiness,l aMotte establishes two basic positions, which re ectan earlier statement in theUpadea on the meaning of praj : Theteaching of emptiness is the emptiness of beings ( pudgala nyat) and

x H x H v bH XXXY ]

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

12/54

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

13/54

Shi h uifeng : Dependent Origination = EmptinessNgrjunas Innovation?

13

Ngrjuna, including the Mah praj pramit Upadea , which istraditionally attributed to him. As such, it is one of the most completemodern studies on the theme of emptiness. Structurally, it doesfollow the broad historical categories of the discourse, but avoids theanachronistic use of material, and draws on numerous lines of textualtradition. For early Buddhism,y nShn uses both classic Chinesetranslations and modern Chinese translations of the Pli canon, and forthe mainstream period, has mastery over the entire range of sectarianliterature well preserved in Chinese, in addition to modern translationsof Pli Abhidhamma and paracanonical material.

As can be seen, previous studies into the broader question of pre-Mahyna teachings on emptiness are few and often apologetic innature. Very little has been at all on the more speci c question of howemptiness relates to dependent origination. As such, the notion withinthe academic discourse on emptiness, which itself works backwardsfrom the accepted idea that Ngrjunas teachings were rather innovativein the light of the early and mainstream Hnayna positions, remainsunexamined and unchallenged. The next two sections of this essaywill thus examine the pre-Ngrjunian literature on emptiness anddependent origination in two general historical periods, namely earlyBuddhism (Section 2) and mainstream Buddhism (Section 3).The distinction between these periods is as much for convenience asrepresenting a clear cut historical division, and itself partly followsthe modern academic discourse attitude toward phases of Buddhistdoctrinalqua historical development.

2. Emptiness & Dependent Origination in Early BuddhismWe will rst examine the canonical texts of early Buddhism to understandthe relationship between empty / emptiness and dependent origination.By early we do not mean to imply original, the philological holygrail of establishing the original words of the historical Buddha nowbeing somewhat out of vogue. We do believe that by cross comparisonof parallel texts from a number of early Buddhism schools will revealin their commonalities those basic teachings that existed before thedivision into such schools occurred. Taking the rst basic schism ofthe Buddhist community into the Sthaviras and Mahsghika to haveoccurred during the time of Aoka, ie. circa 268-232bce , with later

x H x H v bH XXXY _

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

14/54

JCBSSL VOL. XI

14

splits continuing subsequently, we can give an approximate date forearly Buddhism from the time of the Buddha himself up to the 3rd orperhaps even the 2nd centurybce . This is almost universally regardedas well before the start of the Mahyna, and many centuries before thetime of Ngrjuna himself.

The extant texts of the earlieststra discourses are the ve Nikya s ofthe Pli canon, and also the Chinese translations of the four gama s.The ve Pli Nikya s are: 1. TheSamyutta Nikya (SN); 2. The Majjhima

Nikya (MN); 3. The Dgha Nikya (DN); 4. The Anguttara Nikya (AN); and 5. TheKhuddhaka Nikya (KN), which itself contains a rangeof material, wherein the Dhamma pada andSuttanipta are consideredthe oldest strata. This tradition is what is now commonly known asthe Theravda. The Chinese gama translations are:2 1. TheSayukta

gama (S, T99), translated 435-443ce (two fascicles are missing).There is also the Alternative Translation Sayukta gama (AltS,T100), possibly from the Kyapya school. 2. The Madhyama gama (M, T26), translated 397-398ce . These gama s are considered tobelong to the Sarvstivda traditions. 3. The Drgha gama (D, T1),translated 413ce , of Dharmagupta origins. 4. TheEkottara gama (E,T125), translated 397ce and later revised. This is from a late sect ofthe Mahsghika and already contains some Mahynic philosophy.3 It must thus be used cautiously in any context of early Buddhism.

Before we examine the texts, a note on the topic of dependent arising,the Buddhist law of causality, is in order, for it is a theme which stronglyunderlies much of early Buddhist texts. In fact, there is much evidence

to suggest that the entirety of the Buddhas teachings can be subsumedunder this general principle.4 From the SN in particular, we nd termssuch as stability of Dhamma (dhammahitat), certainty (or law)of Dhamma (dhammaniymat), speci c conditionality (idap-

paccayat ) and Dhammic nature (dhammat) to describe dependentorigination, with the S providing an even greater number of suchsynonyms.5 Therefore, here we shall only focus on this doctrine as faras it is directly related to emptiness and related doctrines.2.1. Profound, Connected with Emptiness

x H x H v bH XXXY

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

15/54

Shi h uifeng : Dependent Origination = EmptinessNgrjunas Innovation?

15

One of the more pithy and explicit connections between emptiness anddependent origination, is that found in SN 20:7 A or S 1258. Init, the Buddha states that his disciples should study those discoursestaught by the Tathgata that are profound, profound in meaning,transmundane, connected with emptiness, rather than those textswhich are mere poetry composed by poets, beautiful in words andphrases, created by outsiders.6

The term profound or deep (gambhra) was originally imbued witha simple prosaic sense, such as the deep ocean. Here, and elsewherein the Pli texts, it is used to describe the Dhamma realized by theBuddha, as expressed in SN 6:1 and MN 26 and 27:7

Profound, hard to see, hard to understand, peaceful and sublime,not within the sphere of reasoning, subtle, to be experiencedby the wise. For such a generation this state is hard to see,that is, speci c conditionality, dependent origination. And thisstate too is hard to see, that is, the stilling of formations, therelinquishing of all acquisitions, the destruction of craving,dispassion, cessation,nibbna.

This is a complement to the statement that seeing dependent originationis seeing the Dharma itself. The gama equivalent of these Pli textseither do not have this passage, or show only an abbreviated form.8 However, this two-fold meaning of profound as both the law ofconditionality and also paci ed liberation does appear in S 293, whichstates that these twodharmas are known as the conditioned (saskta)and the unconditioned (asaskta).9 The sense of the law of dependent

arising as profound is further emphasized in DN 15 Mah nidna Sutta,and corresponding M 97 and D 13, where nanda on contemplatingdependent co-arising states that it is wonderful and marvelous, howthis dependent origination is profound and appears profound. Yet, tomyself, I see it as clear as clear can be, and was thus berated by theBuddha for under-estimating the profundity of this Dhamma .10

One way to understand this dual aspect of the profound, is to considerit in terms of dependent origination and also dependent cessation,the former as the arising which issasra or dissatisfactiontheconditioned, the latter as its cessation ornibbna the unconditioned.These correspond to the two complementary aspects of the standard

x H x H v bH XXXY a

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

16/54

JCBSSL VOL. XI

16

formula inUdna 1:1-3: When this is, that is; When this arises, thatarises; and When this is not, that is not; When this ceases, thatceases.11

2.2 Emptiness of Self in Dependent CosmogenesisWhy does SN 20:7 A and S 1258 thus make such an emphaticstatement on what seems to imply the identity of dependent arisingand emptiness? A clear candidate to answer this derives from somerecent research byjureWicz into the idea of the Buddhas twelve-folddependent origination as a response toVedic cosmogenetic theories of

the g Veda (X 129), and other pre-Buddhist Brhmaic literature, suchas the atapatha Brhmaa, Bhadrayaka, Aitareya, TaittiryaandChndogya Upaniad s (seejureWicz 2000: 171).

The Vedic cosmogonies all revolve around what we may call thetransformations of thetman, whereas for the Buddhist twist to thistheory, jureWicz considers that the Buddha chose those cosmogonicdescriptions which met two conditions: rst, they explicitly expressthe cosmogony as transformations of thetman; second, they preservetheir cognitive meaning, even if they are taken out of the Vedic content(jureWicz 2000: 80). Likewise saysSchulMan (2008: 297): Ratherthan relating to all that exists, dependent origination related originallyonly to processes of mental conditioning. It was an analysis of the self,not of reality, embedded in theUpaniadic search for thetman.

For the Vedic tradition, nidna referred to the connection between theworld at large and the microcosm represented in the sacri cial re, andthis connection was thetman. But for the Buddhas nidna, thereis notman The negation of the ontologicalnidna constitutes theBuddhasmahnidna (jureWicz 2000: 100). The various twelve linksare broken down byjureWicz into small consecutive groups, each ofwhich is closer to some or other passage in the various Brhmaic textslisted above. Despite this, thetman idea is seen throughout them all,whereas other phenonema such as the purua , re and so forth, havemore or less importance at di erent stages of the dependent arising

process.jureWicz envisages the Buddha using the terminology of theVedic cosmogony, only to conclude: Thats right, this is how the wholeprocess develops. However, the only problem is that no one undergoes

x H x H v bH XXXYaX

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

17/54

Shi h uifeng : Dependent Origination = EmptinessNgrjunas Innovation?

17

a transformation here! This is to deny thetman as the metaphysicalbasis of all cosmogonic transformations as well as its nal forms(jureWicz 2000: 101). Rather than the creative power of the soul, it wasan absurd and pointless cycle of death and rebirth.

As g oMbrich rightly concludes,jureWicz s interpretation through thelight of ancient pre-Buddhist theories, which were no doubt knownto both the Buddha and much of his more learned audiences, showsits function of adding substance and detail to the Buddhas no souldoctrine (g oMbrich 2003: 14; also 2009: 133 ). Thus, referencesto either not self or emptiness in the many expositions on dependentorigination, would have simply been unnecessary for the Buddha atthat time. It would have been implicitly understood that he thus taughtsasric arising without a soul. The process of dependent arising isempty.

2.3. Causality and the Middle WayWe nd other examples of how the Buddha expressly rejects anactor agent in favour of the doctrine of dependent origination in,for example, SN 12:12 or S 372. Here, when asked about agency,as Who consumes the nutrient of cognition? makes contact? feels? craves?, the Buddha declares that the question is invalid.Rather than who?, the question should be For what is the nutrimentcognition [a condition]? etc.12

In the teaching given by nanda to Channa (SN 22:90Channa, S262*Chanda ), which brought about the latters breakthrough intothe Dhamma , is for all purposes a verbatim repetition of that famousdiscourse given by the Buddha himself to Kaccnagotta (SN 12:15) avoiding the two extreme views of existence and non-existence, andpursuing the middle way which is the dependent origination andcessation of dissatisfaction.13 The connection in S 262 betweenemptiness and absence of (extreme) views is oblique, apart fromemptiness as mere absence itself, and is via the doctrine of dependentorigination. The implication being that the views of either existence

or non-existence, of body and soul as identical or di erent, etc. areincompatible with the Buddhas unique teaching of conditionality.

x H x H v bH XXXYaY

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

18/54

JCBSSL VOL. XI

18

The rejection of arising from any one or other of the four categoriesof self, other, both or neither (non-causality), all types of extremes tobe avoided, is a recurring theme throughout SN 12 Nidna samyutta.14 Rejection of arising from self can be seen as further expressionsof emptiness as not self (or what pertains to self), as the usual self-view predominant in non-Buddhist Indian religious-philosophicalsystems was one of existence. For example, in saccid-nanda, andthe uncaused cause. Rejection of arising from other is in e ect justanother self. With these two rejected, naturally arising from both isalso out of the question. Yet the Buddhas strong emphasis on causalityalso meant that an outright rejection of all causality, things beinguncaused, was also totally out of the question.

2.4. Nirva as Empty Paci cationWhere the cosmogenetic causality of the preceding sections representsthe world and its coming into beingdissatisfaction (dukha), thegoal is the cessation of this worldthe liberated release entailingextinguishing the re of a ictions (P:nibbna, Skt:nirva).

A well known passage in SN and S states that the destruction ofdesire, aversion, delusionthis friend is callednibbna, the unconditioned (asakhata) or the fruition of a worthyone (arahanta phala ).15 The second de nition here, that of theunconditioned, elsewhere has another similar statement again in S262, which gives a list of de nitive terms as follows:16

the empty paci cation (*nyaamatha) of all conditionings,

their non-apprehension (*anupalabhyate), the destruction ofcraving, the fading away of desire nirva.

Given that the equivalentsutta in SN has merely the paci cation(samatha) of all formations ,17 one may question both the Chinesetranslators here and their use of the term , and also our Englishtranslation as empty paci cation. Should not the Chinese phrasereally just be paci cation or appeasement (*amatha)? We thinknot. Asy nShn astutely notes, theYogcrabhmi stra on citing

this text veri es that in fact theSarvstivdin S did indeed use theterm empty paci cation (nya*amatha) here. It explains this verystra passage as The term empty means the forsaking of all the

x H x H v bH XXXYaZ

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

19/54

Shi h uifeng : Dependent Origination = EmptinessNgrjunas Innovation?

19

de lements (seey nShn 1985: 118).18 Thus while there is the impliedsense of absence of a ictions and their resultant dissatisfactionin unconditioned release, the S, at least, explicitly refers to this asempty (nya).

2.5. The Emptiness Samdhi as Absence of CausesHere, a term in early Buddhism which later became almost synonymousfor the path to liberation as a whole, is that of mental release (P:ceta-vimutti) or mental meditation (Skt: *cetosamdhi; ). There isalso a connection here between emptiness and causation.

The Pli Nikya term mental release, which appears in the gama sas mental meditation, is the common name given to a set of fourpractices analyzed by several of the Buddhas great disciples in severaltexts.19 Also, at times the Pli also does usecetosamdhi, rather than just cetovimutti, but only for the signless, and not for the other threeimmeasurables.20 For example, in MN 43, when the question is asked asto What is the signless mental release? (-vimutti), the actual answeris given in terms of the signless mental concentration (-samdhi).21 The gama s, on the other hand, do not seem to use the equivalentceto-vimukti (* ) for the four immeasurables, though this term itself isused in other contexts.

According to SN and S, the four are: 1. Immeasurable (appama- ,aprama-; ) mental release / meditation; 2. Nothingness(kicaa- , kicanya-; ) mental release / meditation;3. Emptiness (suat- , nyat- ; ) mental release / meditation;and 4. Signless mental release / meditation (animitta-; ).22 Inresponse to a question, they are all explained in two senses, rstly asdi erent in meaning and also di erent in phrasing, and secondly asone in meaning and di erent only in phrasing. There are some slightdi erences between answers in the Pli and gama readings, but wewish to draw attention to the second set of answers, where they arealike in meaning and di er only in expression.

As for the four being synonyms, one in meaning and di erent only inphrasing, it is explained that: 1. Desire, aversion and ignorance aremakers of measurement (or limit) ( pama karaa), their absence

x H x H v bH XXXYa[

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

20/54

JCBSSL VOL. XI

20

(sua) is the immeasurable (or unlimited) release; 2. These samethree de lements are causes for something (kicana), a synonymfor sasric becoming, the absence (sua) of something-ness ishence the nothingness release; 3. The emptiness mental release isnot explained here, but is a generic term for all three (see below); 4.The three de lements are also makers of signs (nimittakaraa), theirabsence (sua) is the signless release.

The unifying theme through #1, #2 and #4, is actually #3, the emptinessmental release. While its unifying function is not explained explicitly,it is obviously referred when the other three are described in termsof being empty (sua) of de lements. That is to say, of the otherthree, their ultimate culmination is the immovable mental release (P:akuppa; Skt:akopya) in SN, or non-con ict (*araa; ) in S.23 This is the absence (suat) of the three root de lements which actas makers of measure-limits and signs, and are the basis for becoming.These three termslimit ( pama ), somethingness (kicana) and sign(nimitta)all refer to de lements and their causes, and emptiness,here given as nothingness, is their forsaking.

2.6. The Three Dharma Seals and CharacteristicsAt the end of the early period, when sectarian doctrines already startto make their appearance in the Nikya s and gama s, we shall turn tomaterial that quickly developed into standard criteria for the authentic

Dharma , namely the Dharma seals (mudra) and characteristics(lakkhaa). In many ways, the colloquial use of the term seal (mudr)is similar to both nimitta and lakkhaa in the objective sense, thespecial mark or sign, often of an important o cial, a classic examplebeing the royal seal (rjmudd) (see PTSD 570).

There are several early texts which provided the implicit principlesbehind the later systematized and explicit formation of the three

Dharma seals. We shall deal with the Sarvstivdin S, as it is theonly one to use the term in an early textS 80, the * rya dharma-mudr jna daraa-viuddhi Stra.24 This is perhaps the only earlystra which discusses the dharma seals (dharmamudr) in directrelation to the threesamdhis, headed by thenyatsamdhi. Indeed,the Pli tradition uses the term three characteristics (tilakkahaa)

x H x H v bH XXXYa

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

21/54

Shi h uifeng : Dependent Origination = EmptinessNgrjunas Innovation?

21

for a slightly di erent set of statements with similar overall intention,albeit without the direct association to emptiness. S 80 also dealswith the threesamdhis of emptiness, nothingness and the signless. Itexplains that the emptinesssamdhi is required before proceeding tonothingness and the signless, and that each of the three has a speci ccontemplation:

One, in the emptinesssamdhi they contemplate that each of theaggregates is impermanent and subject to cessation and not solidor stable, but subject to change, they then become detached fromdesire. This is actually more of a contemplation of impermanencethan not self, which is the more common gloss for emptiness.

Two, in the signlesssamdhi they forsake the signs of the six sensoryobjects, form, sound, etc.. This is exactly the same as the earliest idea ofnon-attention to all signs, as found in the exegeticalstra M 211.25 This conforms to the position of S 80 here, as it does not reify thesignless into an object to which one can direct attention, unlike paralleltext MN 43 Mahvedalla .26

Three, in the nothingnesssamdhi they forsake the signs of the threeroot de lements of desire, aversion and delusion. Again, the earlyexplanation of the de lements as somethings, causes for existence insasra. Thus, up to this point in S 80, the signless and nothingnessbasically match SN 41:7 and S 567, which were the precursors to theexegeses in MN 43 and M 211.

However, and more pertinent for our discussion of emptiness anddependent arising here, after these three contemplations,27 one investigates that [notions of] I and mine arise fromeither what is seen, or heard, or smelt, or tasted, or touched,or cognized. Moreover, they investigate in this manner: Bywhatever cause or whatever condition that cognition arises, thosecauses and those conditions are all impermanent. Moreover,when those causes and those conditions of that [cognition]

are all impermanent, how could the cognition itself which hasarisen from them be permanent? Whatever is impermanent isconditioned (*saskta), a formation (*abhisaskra), arisen

x H x H v bH XXXYa]

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

22/54

JCBSSL VOL. XI

22

from conditions ( prattya sautpanna); is subject to decay(*vayadharma), subject to cessation (*kayadharma); subject tofading away (*virgadharma), subject to cessation (*nirodha-

ja dharma). This is known as the purity of gnosis and visionof theryan dharma seals.

So, what exactly here does the phrase dharma seals in S 80 referto? Here, dharma is used in the sense of being subject to some orother principle, as per SN 12:34,28 for whichb odhi has: subject todestruction, vanishing, fading away, and cessation (bodhi 2000: 573).Parts of the Chinese gama , when read alone, are slightly ambiguous.29

These principles mainly refer to cessation, but this is in turn one aspectof causal conditionality.

Thus, S 80 is using a fairly standard set of terms used to describeconditioned phenomena, almost implying the realized goal as the naturalstate of conditioned phenomena. The list is headed by phenomenabeing dependently originated, showing the underlying principle behindthe arising and ceasing ofdharmas, their conditionality. The remainingfour basically synonymous terms indicate the impermanence ofconditioned phenomena. These are contemplations used to eradicatethe view of a self or what pertains to self. Thus, the purity of gnosis andvision of theryan dharma seals is largely about eliminating internaland external de lements, including self view and self conceit, throughvarious forms of contemplation.

2.7. Summary

Between the aforementioned Nikya

and gama

explanations,emptiness and dependent origination were related as a key part of the Dharma from its inception. The previous six sections can perhaps be

divided into three broad groups.

In the rst category, sections 2.1 and 2.6, emptiness relates to boththe process of dependent arising and also cessation. We have seenthat the notion of profound or deep (gambhra) as referring toboth dependent origination and also dependent cessation nibbnic releasewas present though not overly strong in the very early canon.However, the Sthavira traditions considered it important enough at quitean early date, texts and statements which appear to be speci c to both

x H x H v bH XXXYa

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

23/54

Shi h uifeng : Dependent Origination = EmptinessNgrjunas Innovation?

23

the Theravda and Sarvstivda schools. Our examination of the threedharma seals is from the later stages of the early tradition. The textsstill explicitly connect this to dependent origination, that phenomenaare subject to arise and cessation. As seals of conditioneddharmas,there is a gradually movement toward universality.

The second group, in sections 2.2 and 2.3, we see how the Sarvstivdain particular used the term emptiness to refer to dependent arisingin a broad sense. While this mainly focuses on its forwardsasric process, there is still a connection with the reversal intonirva. Recentstudies byjureWicz provide a key connection between the impliedsense of lack of self, ie. emptiness, within the Buddhas standard twelvelimb form of dependent origination, and other expressions thereof, as aparody of Brahmanic cosmogenesis. Included within this broader senseof causality, was the middle way of the absence of extreme views, whichwere considered counter to the position of the Dharma as dependentorigination itself.

Lastly, a third group consisting of sections 2.4 and 2.5 makesstronger the relationship between dependent arising and emptinessas nirvna. Again, it is the Sarvstivdin tradition that makes theexplicit connection of release as empty paci cation. But both thisschool and the Theravda use the emptiness meditation or mind release(respectively) as a catch all term for the practices that bring about thetotal elimination of a ictions as causal factors.

3. Emptiness & Dependent Originationin Mainstream Buddhism

We can now move from the early period, to that of the subsequentmainstream sectarian period. From the last section (2.6) in particular,it is important to recall that this historical distinction is a simple heuristic rather than a hard delineated fact.

As we underscored in our criticisms of the modern academic discourseof emptiness in the introduction, there are several methodologicalproblems with regards to the mainstream period, in particular sourcebiases and anachronist explanations of doctrinal relations and development.Regarding source biases, there is the heavy usage of later Abhidharma literature, particularly that of Vasubandhus Abhi dharmakoabhya

x H x H v bH XXXYa_

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

24/54

JCBSSL VOL. XI

24

and BuddhaghosasVisuddhimagga, as representative of this period asa whole. This refects a more general bias towards viewing only the extant Pli and Sanskrit literature as of value in the study of IndianBuddhism. With respect to historical anachron isms, the Mahyna position is typi ed by the doctrine of emptiness from thePraj pramit andsystematized by Ngrjuna, and the aforementioned Abhi dharma textsrepresent the mainstream period. However, the former texts both hailfrom the 5th century, whereas the latter are from the 1st to 3rd centuries how can the latter be a critical response to the former?

Therefore, in this section, we must pay close attention to textual sources that are deemed to date from before Ngrjunas time (2nd 3rd cty ce ),and even then, be aware of their relative historic relationships. Theprevious section on early Buddhism spanned up to the 3rd, or at thelatest, the 2nd centurybce , as noted at the start of the previous section.Our material here begins with the latter end of this period, when the

Nikya s and gama s were still being compiled by each of the schools.Therefore, though we shall naturally citestra sources which aremore obviously a liated with a given school, we shall rst cite severalstras. These are texts which appear in the gama s of some schools, butare not necessarily found in or approved by other schools, thus lyingoutside of our basic criteria for textual sources of early Buddhism.In particular, this includes severalstras for which we have Chinesetranslations in the Sarvstivdin S and the later Mahyna in uencedMahsghika E (both discussed previously in 2), in addition to thelistamba Stra.

For the mainstream sectarian period, it is admittedly more naturalto refer to the Abhidhamma or Abhidharma literature. The variousschools disagreed as to whether or not it was recited at the rstconvocation. The Mahsghika and two Vibhajyavda schools, theMahsaka and Theravda, did not mention its recitation there in theirrespectiveVinayas, but only spoke of it as the thirdPiaka in their latercommentarial traditions. The Sarvstivda, Haimavata, Dharmaguptaand Mlasarvstivda did include it, but di ered in their details. Inthe commentarial literature, both the Theravda and Sarvstivdastated that the Abhidhamma / Abhidharma was in fact the word ofthe Buddha (seey nShn 1968: 9-11). However, the Theravda meant

x H x H v bH XXXYa

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

25/54

Shi h uifeng : Dependent Origination = EmptinessNgrjunas Innovation?

25

this in the literal sense, whereas theSarvstivda had a more gurativeexplanation.

The core Abhidharma literature thus became even while the Nikya sand gama s were being compiled and nalized, up to the 2nd centurybce . This is still a century or two before the early Mahyna, givingit su cient time to be propagated broadly across the Indian sub-continent. Of the two Abhidharma schools, thePli Theravda hasseven core texts: 1. Dhamma saga ; 2. Vibhaga; 3. Dhtu kath; 4.Puggala paatti ; 5. Yamaka; 6. Pahna; and 7.Kathvatthu.30 Theother Abhidharma school, the Sarvstivda, also had seven Abhidharmastras, albeit di erent to the above: 1. Dharma skandha pda stra (T1537 ); 2. Sagti paryya stra (T1536 ); 3.Prajapti stra (T1538 ); 4.Vijnakya stra (T1539

); 5. Jna prasthna stra (T1543 ) and (T1544); 6.Prakaraa pda stra (T1541 ) and (T1542 );

and 7. Dhtu kaya pda stra (T1540 ).31 Additionally, thereis theriputra Abhidharma stra(T1548 ). This isalso a Vibhajyavdin work, exhibiting clear structural parallels withtheVibhaga and Dharma skandha pda stra , and also the Dhamma-saga andPrakaraa pda , from the other two Abhidharma traditions.It is believed that theriputra Abhidharma stra was probably sharedwith the early Vtsputryas, Dharmaguptas, and other more centralIndian Sthavira Vibhajyavdin schools.32

What we now have of the Theravda commentarial tradition byBuddhaghosa in the Aha kaths is a summary of earlier material. We

still have the Northern Sarvstivdin commentarialVibha literaturein Chinese translation, most notably the Abhidharma Mahvibhastra (T1545 ), with variants Abhi dharma Vibhastra (T1546 ) and Vibha stra (T1547 ).This Vaibhika standard was likely compiled by a large number of

Abhidharma scholars over the course of centuries, in order to establishorthodoxy within their own ranks, as well as counter the views of otherschools, and reached its basic nal form in the mid 2nd cty ce (seey nShn 1968: 209-220;d haMMa joti 2007: 65).

x H x H v bH XXXYaa

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

26/54

JCBSSL VOL. XI

26

As such, the Mahvibha is the last pre-Ngrjunian material that weshall examine here. Citing material later than Ngrjuna would endangerour goal here by potentially falling into anachronistic arguments asdiscussed earlier in the discourse on emptiness above. However, this timeperiod coincides with the formative period of the incipient Mahynamovement, and we can feel the currents of mainstream school notionsof thebodhisattva here referring to kyamuniin uencing the newmovement, even while these mainstream bhidharmika commentariesdid not seem to be aware of the Mahyna as a distinct school in its ownright. We shall see how mainstream notions of thebodhisattva, andhow they involve both emptiness and dependent origination, may havedeveloped in these texts in Section 3.4, below.

3.1. Ultimate EmptinessNeither Coming Nor GoingThe rst sectarianstra under consideration is theParamrthanyatStra, extant as S 335 and E 37:7.33 If we only compared with thePli to nd no equivalent of thisstra, we may be tempted to classifyit as a text of mainstream school origins. However, the fact that theSthavira Sarvstivdin version is nearly word for word identical withthe Mahsghika E versionwith the exception of some juxta-posing of paragraphs which is negligible in terms of contentsuggeststhat the text could also possibly be considered early. It is possiblethat the Theravda tradition may have lost their own version of this textat some point in time. TheParamrthanyat Stra (S 335) states:34

when the eye arises, it does not come from any location;when [the eye] ceases, it does not go to any location. In this

way, the eye is unreal, yet arises; and on having arisen, it endsand ceases. There is action (karma) and result (vipka), and yetno actor agent (kraka). On the cessation of theseskandhas,another set of aggregates continues elsewhere (anyatra). Thereare merelydharmas classi ed as conventional, ie. the ear, nose,tongue, physical body and mind, are also declared as such.

Here, the parallel text E 37:7 also adds These six sense facultiesare also not created by a person (*puria, *pudgala).35 This further

emphasizes the absence of an agent. According tok arunadaSa , suchstatements on neither coming nor going are also found in the laterTheravdin commentarial literature: There is no store (sannidhi) from

x H x H v bH XXXZXX

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

27/54

Shi h uifeng : Dependent Origination = EmptinessNgrjunas Innovation?

27

which they come and there is no receptacle (sannicaya) to which theygo;36 and If they appear it is not that they come from somewhere (nakuto ci gacchanti); if they disappear it is not that they go anywhere(na kuhici gacchanti) (k arunadaSa 2010: 30-31).37 This is the samebasic gloss the commentaries also give to SN 35:246V (= S 1169),which uses a simile of how the music of a lute is dependent on a numberof parts and factors.38

The phrase in translation (dharmas classi ed asconventional) poses some problems for interpretation. We mustexamine the various versions of thisstra and also parallels of thepassage in other texts. The phrase appears in the Bimbisra Stra , whichis in turn cited in the Mla sarvstivdin Vinaya.39 Subsequently, in theKoa and Bhya .40 we conclude that the original term was *dharma-sakheta, which we translate as dharmas classi ed as conventional.This is akin to phenomena being nominal here, though semanticallyat least, it di ers from the Abhidharma usage of prajapti asdesignation, and the implications of it be vis--vis paramrtha , theultimate sense.

The S version of thestra then continues, stating:41

Dharma s classi ed as conventional, that is to sayWhen thisexists, that exists; when this arises, that arises the arising ofthis sheer great mass of dissatisfaction. MoreoverWhenthis does not exist, that does not exist; when this ceases, thatceases the cessation of this sheer great mass of dissatisfaction.O monks! this is named the Dharma Discourse on UltimateEmptiness (Paramrthanyatdharma Stra).

It is thus clear that dharmas classi ed as conventional refers to thedharmas which comprise the limbs of dependent arising itself. Thisis not only in the forward order of arising, but also the reversal intocessation. The cessation of dissatisfaction isnirvna, the unconditioned.Is it any particular one of these aspects which is ultimate emptiness?It is di cult to say, but the overall sense appears that it is the totalityof this situation, the Dharma law of dependent arising and cessationof conventional or nominaldharmas as phenomena, all of which takesplace without recourse to an agent or actor, that is ultimate emptiness.It could be possible to then read this through the two truths system

x H x H v bH XXXZXY

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

28/54

JCBSSL VOL. XI

28

so popular in the mainstream sectarian period, utilized by both the Abhidharma systems as well as the Madhyamaka. In that way, the

ultimate could be juxtaposed against the designated ( prajapti ),giving the underlying principle of dependent origination as the former,whereas the phenomena are the latter.

3.2. Great EmptinessNeither Identity Nor PluralityThe second sectarianstra is another Sarvstivdin text, S 297

Mah nyat Dharma paryya .42 Without a Pli equivalent,y nShn (1971: 651) locates it in the Nidna sayukta, which is supported by

the content and surroundingstras. It has a similar teaching formatto S 262, above. As we would thus expect, it explicitly uses thestandard twelve link formula of dependent arising. However, it alsoties dependent origination in with emptiness:43

What is the Dharma Discourse on Great Emptiness? It is this When this exists, that exists; when this arises, that arises. WhichisFormations are conditioned by ignorance; cognitions areconditioned by formations; and so forth, up to; the amassing of

this sheer mass of dissatisfaction. Then follows a refutation of several positions which appear in the tenor fourteen unanswered questions (avykta), all of which are formsof self-view (tmadi), such as life ( jva ) and body are di erentor identical. A very similar statement occurs in SN 12:35,44 lendingfurther support to placing S 297 in the Nidna sayukta. Thestra stresses dependent origination as the middle path between theseextremes of view based around the idea of a self (as jva ).45 Theconnection between these questions and the rest of the text is mostlikely that such questions are basically predicated on the notion of aself, though often under the guise of the term tathgata (k aruna -daSa 2005). As we have already seen fromjureWicz s studies above,this is obviously one of the key points that the Buddhas formulation ofdependent origination seeks to reject.

The reverse process, the destruction of the dependent cessation process

in reverse sequence ( pratilomika ), is given as thestra ends with:46

With the fading away (*virakt) of ignorance (avidy),knowledge (vidy) arises; on the cessation of ignorance, there

x H x H v bH XXXZXZ

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

29/54

Shi h uifeng : Dependent Origination = EmptinessNgrjunas Innovation?

29

is the cessation of conditionings; up to; the cessation of thesheer, great mass of dissatisfaction. This is named the Dharma

Discourse on Great Emptiness.

Together, these show that existence is dependent arising in forwardorder (anuloma) from self view and desire, and also dependent cessationthrough the reverse order ( pratiloma ) of this process. In the text it isnot altogether clear whether the term emptiness applies to both, ormerely one of, these two processes. However, we have shown earlierhow empty was used as a description of conditioned phenomena,along with impermanence, dissatisfactoriness and not self, and also, that

the absence of the de lements is given as the transmundane meaningof emptiness elsewhere. Therefore, it seems fair to conclude that theterms empty and emptiness refer to both processes.

3.3. Seeing Dependent Origination as Dharma, as BuddhaA third sectarianstra of note is thelistamba Stra. This is oftenclaimed to be a Mahyna stra. While the titles of the earliest recensionsin Chinese are simply listamba, the later Sanskrit recension title

is pre xed with Madhyamaka- . However, asr eat clearly shows,content and structure much of which is found scattered through thePlisuttas, all suggest as the date of thelistamba Stra as a whole,200 bce plus or minus 100 years (r eat 1993: 4-5).47 It thus actuallypre-dates the already self-identifying form of the Mahyna, but waslater widely cited by Mahyna scholars, and formed an importantbasis for their presentation of dependent origination. Note that unlikethe previous two sectarianstras, however, it is not associated with

the S or the Sarvstivda in general. Thestra

famously states that:Whoever sees dependent origination sees the Dharma . Who sees the Dharma , sees the Buddha .48 This is most likely a combination of two

statements concerning seeing thedharma found in the gama s.49

The text has a four-fold structure, considering cause (hetu) andcondition ( pratyaya ) in relation to internal and external phenomena.The predominant simile is that of the growing of a seed, hence thename li-stamba which means rice-stalk, which also hints at adistinction between seed as cause, and other factors as conditions.

x H x H v bH XXXZX[

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

30/54

JCBSSL VOL. XI

30

The di erence between cause and condition is somewhat akin to thatbetween the causal nature of own nature (sabhva) and other nature( parabhva ) in the TheravdinPeakopadesa and Nettip pakaraa (seeWarder in aMoli 1982b: xvii). It is a distinction also found in theSarvstivda.

According to the earliest version of thestra,50 living beings do not go from this life to another life but thereis action (karma) and result, causally conditioned retributionwithout any loss.

There are other paraphrases of statements found in the earlystras.There are passages in the earlier recensions with a variety of termsas direct adjectives for dependent arising, which include notconditioned, not abiding, unconditioned, not an object of mind,paci ed, cessation, signless.51 In the later Sanskrit, this is expandedto include impermanence, dissatisfaction, emptiness, absence ofself.52 The terms of this common pericope are often very closelyassociated with emptiness, in fact, emptiness is often the rst term on

the list, indicating its predominance over the others.53

This means thatthe correct contemplation of dependent origination ensures that thepractitioner will not arise various deluded views about their existencein the past or future. They will remove all the heterodox views whichare based on theories of a soul (tmavda), living being (sattva-), lifeprinciple ( jva- ), person ( pudgala- ), and so forth.54 The implied senseis that of the emptiness of the Self.

The stra nally concludes with statements that one who correctlyenters into receptivity of the Dharma of dependent origination will infact become a fully awakenedbuddha.55 As this statement is found inmost recensions of the text, it is at present di cult to assess whetherthis statement is a later addition or original. Similar to statements in the

Mah vibha stra indicate that dependent arising was the object ofcontemplation for thebodhisattva(s), a point which we shall examine infurther detail below, via the comments of the Vaibhika Master Parva.

x H x H v bH XXXZX

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

31/54

Shi h uifeng : Dependent Origination = EmptinessNgrjunas Innovation?

31

3.4. Abhidharma stra and Mahvibha ExegesisIn addition to the obvious connection that the Sarvstivdin stras

place upon considering dependent origination as emptiness, their Abhidharma also makes this connection. We shall examine this fromthe ancient Dharma skandha pda stra , and the later orthodox stan-dard, the Mahvibha stra.

The Dharma skandha pda is perhaps the earliest of the Northern Abhidharma literature, hailing from around 300bce , contemporary

with the PliVibhaga. The text cites astra which discusses both the

Dharma law of dependent origination ( [ ]) as well as dependentlyoriginateddharmas as phenomena ( ).56 The stra cited,*Prattyasamutpdadharma ( ), appears to be our previouslyencountered S 296, a parallel of the Pli SN 12:20Paccayo. Dealingwith causality (nidna), it suggests a text from the oldest strata of Sand SN, the Nidna sayukt. This samestra is also cited by perhapsthe oldest of all the Abhidharma literature, theriputra Abhidharma,but without elaboration.57

After elucidating both the Dharma principle of the causal relationshipsbetween the phenomenologicaldharma events, and the actualdharmas themselves, it is stated that for one who knows and sees this as it reallyis, it is impossible that they will fall into various forms of thought suchas Did I exist in the past?, Will I exist in the future, and so forth.Both the Sstra itself and also the Dharma skandha pda usage of it,(but neither the Plisutta itself nor theriputra Abhidharma stra citation,) then expressly state that this is because for one who knowsand sees, they have totally removed all these various conceptualizationswhich are connected with the view of a self, a living being and soforth.58 This is thus akin to the points of view rejected in the Mah-nyat Dharma paryya and thelistamba Stra(above).

Together, this is a very strong indicator that vision of dependentarising, and thus not self, was the considered the factor which madeone anryan. This is supported by earlier material such as S 347 and

SN 12:70Susma, which explains that one rst realizes gnosis of thestability of Dharma (dharmasthitat), and then gnosis ofnirva.But despite this seemingly important statement, the Dharma skandha-

p p n Z PPPRPU

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

32/54

JCBSSL VOL. XI

32

pda commentary resigns itself to merely mechanically explainingthe twelve links, and remains silent as these varioustman basedviews. Of approximately the same historical period, the TheravdinPaisambhidmagga also explains this gnosis of stability of Dhamma (dhammahitat) as knowledge of the various dependently relatedconditions.59

The samestra cited by Dharma skandha pda also provides us with anumber of terms for dependent origination which indicate its positionas a kind of natural and immutable law. The S version adds severalterms over and above the Pli, including suchness of Dharma ( ;*dharmatathat), Dharmic nature ( ; *dharmat), factuality( ; *bhtat), and others.60 Elsewhere in the Dharma skandha-

pda , a strikingly similar description which indicates a kind of eternalprinciple, hinting at an unconditioned nature, is also given for theryan truths.61 A shortened list featuring only*dharmasthitit and*dharmat appears in the Mahvibha . Here the authors wish to refute theVibhajyavdin view that dependent origination is an unconditioned(asaskta) dharma, by stating that unlike the unconditioned cessation,etc., dependent origination is still within the sphere of the past, presentand future, and thus conditioned, despite it being a xed and eternalprinciples.62 All this quite possibly has its roots in the Dharma skandha-

pda passages cited above.

As shown in the Dharma skandha pda , although both the Dharma ofdependent arising itself and dependently originateddharmas are ofone substance, they are still di erent objects.63 The Vaibhika

master Vasumitra, in presenting the statement Whosoever sees dependent origination sees the Dharma , where dependent originationis explicitly given in the twelve causal links (nidna) format, claims thatsome [masters] state that realization through the emptiness entranceto release is a case of seeingdharmas but not seeing dependentorigination; whereas realization through the intentionless entranceto release is seeing bothdharmas and dependent origination.64 This would mean that the emptiness release described by Vasumitrarefers to the variousdharmas themselves, but not their mutual causalrelationships.

x H x H v bH XXXZX

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

33/54

Shi h uifeng : Dependent Origination = EmptinessNgrjunas Innovation?

33

Moving ahead several centuries we arrive at the critical Northern Abhidharma commentarial tome, the Mahvibha . Completed in the

middle of the 2nd centuryce , it certainly precedes Ngrjuna (2nd 3rd centuryce ), and would doubtlessly have been a major doctrinal forceacross much of mainland Indian Buddhism during his lifetime. In the

Mah vibha, theSusma Stra was again cited for discussion, but nowthe above position of the Dharma skandha pda became just one ofmany explanations, to be nally supplanted by an explanation more intune with the developing Vaibhika system.65

In the Mahvibha , Parva analyses various personality types, andstates that thebodhisattvas who are followers by desire (*tnusrin)who take the result as the entrance, and also the followers byviews (*dyanusrin) who take the cause as the entrance, bothcontemplate the Dharma of dependent origination, and based on theemptinesssamdhi, they enter into certitude of perfection.66 This isfurther shown by a verse which states:67

The fully awakened ones (sabuddha) of the three periods oftime, break the poison of sorrow, they all emphasize the true

Dharma (*saddharma), always abiding in the nature of Dharma(*dharmat).

While this appears to be speci cally just for those on thebodhisattva path to eventual full awakening, elsewhere other statements seem toimply thatryans as a whole all realize*dharmat.68 But despitethis, the connection between realization of this dependent arisingand theryan stages appears to have become gradually weaker over

time. Perhaps it was more the case that this sort of release through theemptinesssamdhi which contemplates dependent origination as per*dharmat as their object, was a special case for thebodhisattva.

Statements in the Mahvibha stra which explicitly connect theemptinesssamdhi to dependent arising are few,69 when compared withthe extremely common format of this practice being contemplation onthe not self and emptiness aspects of the four truths. In the openingpassages of the Mahvibha , the connection between knowledge ofnot self (emptiness is not mentioned) and dependent origination ismade explicit, as perception of the former gives rise to the latter.70 Rather than a vision of dependent origination, insight into those xed

x H x H v bH XXXZX_

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

34/54

JCBSSL VOL. XI

34

laws that indicated how speci cdharmas arise and cease due to speci cconditions as being the rst stage ofryan status, there was a shifttowards vision of just thedharmas themselves.

Both Parvas position vis--vis thebodhisattva(s), which is no doubtbased on the notion that it was just such a contemplation that led tokyamunis own awakening universally extended to allbodhisattva candidates, and also Vasumitras older source for dependent arising,hint at the antiquity of these two scholars who have a tendency towardsthe earlier works over the later commentarialstras. Both would havebeen approximately 100 years before Ngrjunas own time (circa 2nd 3rd centuriesce ), around the period of the newly forming Mahyna.

3.5. Un/conditioned Status of Dependent OriginationAt this point, we would like to leave aside the citation of individualtexts, and turn to a broader issue. Up to this point, we have seen thatthe Abhidharma methodology of classi cation ofdharma(s) as eitherconditioned (saskta) or unconditioned (asaskta)dharma graduallybecame more signi cant as time progressed. While this dharmavdaapproach should be more narrowly con ned todharmas (plural) asphenomena, it appears that the use ofdharma (singular) as a law orprinciple, was unable to escape such analysis. It thus came to be that thequestion of whether or not the very principle of dependent origination( prattya samutpdadharma) was conditioned or unconditioned,and not just those things that were dependently originated ( prattya-samutpannadharmni), came about. As we have already seen inthe Nikya s and gama s themselves, there were a number of termscommonly taken as synonyms for dependent arising, such as stabilityof Dharma (dharmasthitit) and suchness (tathat). These were alsodrawn into the range of this debate, though as we shall see below, theywere not necessarily seen as exact equivalents.

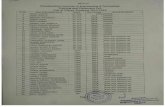

Drawing from the excellent study ofb areau on the jungle of viewsthat makes up sectarian Buddhism, we may tabulate the attribution ofconditioned or unconditioned status to these three notionsdependent

origination, the stability of Dharma , and suchnessas advocated byvarious schools (fromb areau 2005: 287):71

x H x H v bH XXXZX

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

35/54

Shi h uifeng : Dependent Origination = EmptinessNgrjunas Innovation?

35

Conditioned (saskta) Unconditioned (asaskta)Dependent

Origination

Stability

of

Dharma

Suchness Dependent

Origination

Stability

of

Dharma

Suchness

Vtsputriya (#38)

Theravda (#55) (#21) (#186)

Sarvstivda (#6, #28) (#6) (#6)riputra Abhidharma

(#10) (#10) (#10)

Mahsghika (#43) (#43) (#43)

Mahsaka (#19) (#19) (#19)

Uttarpathaka (#32*)

(#32*)Dharmagupta (#13)

Prvaaila (#9)

Vibhajyavda (#8)

On one side, there were the schools which tended towards consideringdependent origination, etc., as conditioned: These are notably the earlierSthavira schools with bhidharmika tendencies, such as the Theravda,Vtsputriya and Sarvstivda. We would probably expect to see theriputra Abhidharma stra among this group, but out of the threethey only considered suchness as conditioned. For the conditionedstatus of the stability of Dharma and suchness, there was also support

from the Mahsghikas and Mahsakas, and a quali ed a rmationfrom the Uttarpathakas.

On the other side, there were also those who inclined to an interpretationof these as unconditioned: The Mahsghikas andriputra

Abhidharma stra had a shared list of nine unconditioned, including:8. The self-nature of the members of conditioned production (*prattya-samutpdgasvabhva); and 9. The self-nature of the factors of thePath (*mrggasvabh).72 However, according tob areau s sourcesat least, both the Mahsghikas and theriputra Abhidharmastra otherwise considered that suchness itself is conditioned. Werethere di erent forms of suchness, such that some were conditioned

x H x H v bH XXXZXa

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

36/54

JCBSSL VOL. XI

36

and others not? The Mahsaka also had nine unconditioned, ona slightly di erent list, although also including: 8. The suchnessof the Path (mrgatathat); and 9. The suchness of dependentorigination ( prattya samutpdatathat).73 The Dharmaguptakas upheldunconditioned status regards dependent origination alone, but there isno mention of their position vis--vis stability of Dharma or suchness.74 The Prvaailas agreed, simply on the basis of astra, which was mostprobably their equivalent of SN 12:20 / S 296.75 They also consideredthat the fourryan truths themselves were unconditioned, for basicallythe same reasons.76 The otherwise unelucidated agreement of so-calledVibhajyavdins,77 makes them appear to be any group other than thethree earlySthavira Abhidharma schools.

In addition to the above points, we also nd some other related doctrinalpositions of the Sthavira traditions. TheKatthvatthu states a positionof the Theravdins against the Andhakas, namely that the formerconsider that emptiness (along with the signless and intentionless)is not included in the aggregate of the mental formations.78 On thegrounds that whatever is a formation (saskra) is also conditioned(saskta), this would seem to mean that the Andhakas consideredeven emptiness itself to be conditioned.

The category of the unconditioned has always been a standard of bhidharmika analysis based on the earlystras. However, the very

notion of anything being unconditioned has always been problematicfor Buddhists who were loathe to run up against their core doctrine ofnot self or non-self, ie. emptiness. Here we have seen how it related to

dependent arising, and its synonyms. But it obviously also extended tothe notion of emptiness, as some form of equivalence had already beenestablished. This di culty can be seen, for example, in Ngrjunasunderstanding of the emptiness of emptiness, the argument that toturn emptiness itself into a rei edunconditioned, not dependent phenomena, is to make perhaps the greatest mistake of all. Much ofthe discourse on the emptiness of emptiness has been an ontologicalone, which has often failed to look to its earlier precedents. It appears tohave its roots in seeing as empty the very insight contemplation whichperceives the emptiness of phenomena. This is quite a di erent matteraltogether, but unfortunately beyond our scope here.

x H x H v bH XXXZYX

-

8/10/2019 Huifeng 2014

37/54