How important are the'non-traditional'economic roles of agriculture ...

Transcript of How important are the'non-traditional'economic roles of agriculture ...

Discussion PaperNo. 0118

Adelaide UniversitySA 5005, AUSTRALIA

How important are the 'non-traditional'economic roles of agriculture in

development?

Randy Stringer

May 2001

CENTRE FOR INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC STUDIES

The Centre was established in 1989 by the Economics Department of the AdelaideUniversity to strengthen teaching and research in the field of international economics andclosely related disciplines. Its specific objectives are:

• to promote individual and group research by scholars within and outside the AdelaideUniversity

• to strengthen undergraduate and post-graduate education in this field

• to provide shorter training programs in Australia and elsewhere

• to conduct seminars, workshops and conferences for academics and for the widercommunity

• to publish and promote research results

• to provide specialised consulting services

• to improve public understanding of international economic issues, especially amongpolicy makers and shapers

Both theoretical and empirical, policy-oriented studies are emphasised, with a particularfocus on developments within, or of relevance to, the Asia-Pacific region. The Centre’sExecutive Director is Professor Kym Anderson (Email [email protected]) andDeputy Director, Dr Randy Stringer (Email [email protected]).

Further details and a list of publications are available from:

Executive AssistantCIESSchool of EconomicsAdelaide UniversitySA 5005 AUSTRALIATelephone: (+61 8) 8303 5672Facsimile: (+61 8) 8223 1460Email: [email protected]

Most publications can be downloaded from our Home page athttp://www.adelaide.edu.au/cies/

ISSN 1445-3746 series, electronic publication

CIES DISCUSSION PAPER 0118

How important are the 'non-traditional' economic roles ofagriculture in development?

Randy Stringer

School of Economics andCentre for International Economic Studies

University of AdelaideAdelaide SA 5005

Phone + 61 8 8303 [email protected]

May 2001

Copyright 2001 Randy Stringer________________________________________________________________________

This paper has been prepared for FAO’s ESAC Research Project, Socio-Economic Analysisand Policy Implications of the Roles of Agriculture in Developing Countries. The paper waspresented at the 19--21 March 2001 Consultation in Rome. Thanks due to the discussantsfor helpful suggestions and comments, including J. Mellor, R. Pertev, K. Stamoulis and A.Valdés. Responsibility remains with the author. All the papers may be accessed via FAO’sweb site: www.fao.org.

ABSTRACT

How important are the 'non-traditional' economic roles ofagriculture in development?

Randy StringerSome good reasons explain why early approaches to identifying agriculture’s economicroles resulted in a one-way strategic path that involved the flow of resources towards theindustrial sector and urban centres. In an effort to provide a more comprehensive view ofthe roles that agriculture plays in promoting human well-being, FAO initiated the Role ofAgriculture Project (ROA) to provide a new approach to poverty alleviation and socio-economic development.

The purpose of this report is to present examples, suggestions, and possible methods andtools on how to document, measure and identify the functions and values of the ‘non-traditional’ economic roles that agriculture plays in the development process. The report’simmediate aim is to provide a basis for discussion during the ‘Economic Roles of Agriculture’session at the 19-21 March, consultation in Rome. The intent here is to provoke discussion,rather than to capture all of the issues and details that merit analysis.

The paper presents examples to initiate the discussion and allow participants to addsubstance, refine concepts and alter, delete and adapt the analytical framework asappropriate. Six of the contributions listed in Figure 1 are outlined in some detail. Otherexamples may be discussed during the consultation together with those suggested byparticipants. The six examples are agriculture’s economic contributions: (i) to agribusinessactivities not usually considered part of the agricultural sector; (ii) as social welfareinfrastructure; (iii) through rapid productivity growth; (iv) to alleviating poverty; (v) to learningand education; and (vi) to healthy and safe food. The remainder of the paper suggestsalternative methodologies, identifies various indicators and presents ways to measure theireconomic importance.

Using both qualitative and quantitative methods to capture non traditional economic roles issuggested to help understand the various functions, benefits and values . A narrativeapproach would involve analyzing: the economic roles of agriculture in contributing toagribusiness, local trade and service firms, and the social structure of rural communities; thelikely influence of new technology and economic stress on the organization and control ofagricultural resources; the relative importance of agriculture in the economic base of ruralareas; competition for resources between agriculture and other components of the ruraleconomy, and the importance of off-farm employment and income for farm families.

Contact author(s):Randy stringerSchool of Economics andCentre for International Economic StudiesUniversity of AdelaideAdelaide SA 5005Phone + 61 8 8303 [email protected]

How important are the 'non-traditional' economic roles ofagriculture in development?

Randy Stringer

Introduction and Overview

Long before Johnston and Mellor (1961) identified what are today considered the

fundamental economic contributions of agriculture to development, economists

focused on how agriculture could best contribute to overall growth and moderization.

Many of these earlier analysts (Rosenstein-Rodan, 1943; Lewis, 1954; Scitovsky,

1954; Hirschman, 1958; Jorgenson, 1961; and Fei and Ranis, 1961) highlighted

agriculture for its many resource abundances and its ability to transfer surpluses to the

more important industrial sector. By serving as the ‘handmaiden’ to the industrial

sector, agriculture’s primary role in the transformation of a developing economy was

seen as subordinate in the central strategy of accelerating the pace of industrialization.

As Vogel (1994) notes, Hirschman singled out agriculture for its failure to exhibit the

strong forward and backward interindustry linkages needed for development.

Hirschman (1958) argued that, ‘…agriculture certainly stands convicted on the count

of its lack of direct stimulus to the setting up of new activities through linkage effects:

the superiority of manufacturing is crushing’.

Over time, a traditional approach to development emerged that concentrated on

agriculture’s important market-mediated linkages. Several core economic roles for

agriculture formed this traditional approach: (1) provide labour for an urbanized

industrial work force; (2) produce food for expanding populations with higher

incomes; (3) supply savings for industrial investments; (4) enlarge markets for

industrial output; (5) earn export earnings to pay for imported capital goods; and (6)

produce primary materials for agro processing industries (Johnston and Mellor, 1961;

Ranis et al 1990; Delgado et al, 1994; Timmer, 1995).

In an effort to provide a more comprehensive view of the roles that agriculture plays

in promoting human well-being, FAO initiated the Role of Agriculture Project (ROA)

to provide a new approach to poverty alleviation and socio-economic development.

The objectives of ROA include providing policy makers with insights and tools for

informing policy options concerning the diverse roles of agriculture in the context of

greater and more sustainable development; producing a common analytical framework

and valuation tools, as well as in-depth documentation from country case studies; and

creating awareness and general appreciation of the diverse roles of agriculture in

society and how their nature, magnitude, and policy implications vary by farming

system, country setting, and through time (FAO, 2001).

The purpose of this draft report is to present examples, suggestions, advice, methods

and tools on how to document, measure and identify values of the ‘non-traditional’

economic roles agriculture plays in the development process. The report’s immediate

aim is to provide a basis for discussion during the ‘Economic Roles of Agriculture’

session at the 19-21 March, consultation in Rome. The intent here is to provoke

discussion, rather than to capture all of the issues and details that merit analysis.

More specifically, the aim of this discussion paper is to suggest answers to the

following questions: (1) What are the key conceptual issues to be addressed in

devising an approach for defining and measuring the non-secular economic impacts of

agriculture? (2) What has been done so far to study and address these issues? (3) Once

the issues have been identified, how analytical framework derives from the issues

identified? (3) What types of indicators could be used or possibly developed to

measure and compare the non-secular economic outputs of agriculture?

What do we mean by agriculture’s non-traditional economic roles?

Some good reasons explain why early approaches to identifying agriculture’s

economic roles resulted in a one way path that involved the flow of resources towards

the industrial sector and urban centres. In agrarian societies with few trading

opportunities, most resources are devoted to the provision of food. Agriculture’s

shares of national output and employment therefore start at high levels. As economic

development proceeds, agriculture’s shares of GDP and employment typically fall.

This is commonly attributed to the slow rise in the demand for food as compared with

other goods and services as incomes rise; and the more rapid development of new

technologies for agriculture, relative to those for other sectors, which leads to

expanding food supplies per hectare and per worker. A third but less-commonly

recognized phenomenon contributing to agriculture's relative decline is the rapid

growth in modernizing economies in the use of intermediate inputs purchased from

other sectors (Anderson, 2000a).

This decline in agriculture’s GDP share results partly because post-farm gate activities

(such as taking produce to market becomes commercialized and taken over by

specialists in the service sector) and partly because producers substitute chemicals and

machines for labour. Producers receive a lower price and in return for which their

households spend less time marketing. As a result, value added by the farm

household's own labour, land and capital, as a share of the gross value of agricultural

output, falls over time as purchased intermediate inputs become more important. This

increasing use of purchased intermediate inputs and off-farm services by farmers adds

to the relative decline of the producing agricultural sector per se in overall GDP and

employment (Timmer 1988, 1997; Pingali, 1997).

Agriculture’s declining share in the economy sends a confusing signal to policymakers

that agriculture is relatively unimportant. And the falling real prices of agricultural

commodities sends the signal to investors that returns are relatively unattractive

(Tyers and Anderson, 1992)

A number of development economists attempted to point that while agriculture’s

share fell relative to industry and services, it nevertheless grew in absolute terms,

evolving increasingly complex linkages to the non-agricultural sectors. This group of

economists (including Kuznets 1968; Kalecki, 1971; Mellor, 1976; Singer, 1979;

Adelman, 1984; de Janvry, 1984; Ranis, 1984; and Vogel, 1994, to name a few)

highlighted the interdependence between agricultural and industrial development and

the potential for agriculture to stimulate industrialization. They argue that

agriculture’s productive and institutional links with the rest of the economy produce

demand incentives (rural household consumer demand) and supply incentives

(agricultural goods without rising prices) promoting modernization.

This broader approach to the economic roles of agriculture suggested that the one-way

path leading resources out of the rural communities ignored the full growth potential

of their agricultural sectors. A two-way path was needed. Resources still must move

towards industry and urban centres, but with attention focused on the capital,

technological, human resource and income needs of agriculture. This required

policymakers to change strategies. Traditional macroeconomic policies that inhibited

rural sector growth through direct and indirect taxation of food producers, traders and

exporters would need to give way to a more a non-discriminatory policy environment

for agriculture (Krueger et al, 1991; Bautista and Valdés, 1993); investments in

producing technological innovations (Hayami and Ruttan, 1971; Pinstrup-Anderson,

1994; Oram, 1995); and public investments in rural incomes generating social and

physical infrastructure (Adelman, 1984; Vogel, 1994).

One aim of the ROA project is to extend our current thinking about the economic

roles of agriculture further. In particular, to identify those economic contributions for

which the market prices of agricultural activities fail to convey enough information to

secure an optimal level of those activities. (Environmental goods and services as well

food security contributions are addressed in a separate report to be presented at the

consultation. See Cooper, 2001 and Lee, 2001. FAO’s web site www.fao.org.)

Agriculture’s under-recognised, non-traditional economic roles

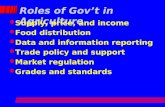

Figure 1 provides one way to map out a conceptual approach to the non-traditional

economic roles of agriculture. Beginning on the left hand side, the traditional

economic roles are listed as direct use contributions. Moving to the right, the next set

of contributions represent what are more commonly know as agribusiness activities,

followed by externalities and public goods on the right hand side. This mapping offers

an approach to introducing and defining the non traditional economic roles of

agriculture.

The importance and weight attached to a given role varies between and within

countries, depending on their particular situation and national priorities. These various

functions and benefits are valued differently by different people and different groups.

Local, national and international interests in agriculture’s economic roles also differ

greatly across landscapes. Moreover, the roles that agriculture is expected to play in

local, national, and global development change over time.

Agriculture’s economic contributions to agribusiness activities

While classified as direct contributions and easily measurable, the many economic

activities of agribusiness are often ignored by governments and policymakers. A large

and increasing part of economic growth during the process of development can be

attributed to those activities that support the production, marketing, and retailing of

food, textiles, clothing, shoes, tobacco, beverages, and related good for both domestic

consumers and exports.

Over time, primary agriculture gives up the processing, storing, merchandising,

transporting, and financing practices, giving way to a more complex, specialised and

integrated process. A long, circular chain evolves. Input providers, farm suppliers,

assemblers, processors, wholesalers, brokers, importers, exporters, retailers,

merchants, distributors, and consumers join the food and agricultural economic links.

Additional activities continually service these businesses, including research,

transportation, packaging, storage, futures markets, advertising and promotion (Davis

and Goldberg, 1957; Newman, et. al. 1989; Holt and Pryor, 1989; FAO, 1997).

All these agribusiness activities are totally dependent on primary production. Primary

production grows and evolves reflecting agribusiness, and agribusiness grows and

evolves reflecting primary production. They are inextricably connected. Ignoring the

large economic contributions of primary agriculture to these much faster growing

agribusiness activities presents an incomplete picture of their shared world.

Take for example, how much more agricultural commodities are used as inputs into

food processing in the industrial countries. In Argentina, Brazil, Korea Republic and

the USA, more than 60 percent of total agricultural output is used as an input into

further economic activity. Contrast this with India, where more than two thirds is

consumed directly (Holyt and Pryor, 1999).

Likewise, the more developed agricultural economies depend on more power,

machinery and agro-services. In India, some 70 percent of the total cost of processed

rice is paddy rice. In the USA, the rice is less than 6 percent of the total cost (Holyt

and Pryor, 1999). While the share of service-related input costs in the USA is more

than 20 percent, in Mexico and the Philippines it is less than 1 percent. The overall

importance of agribusiness as a share of total GDP is seen in Table 1. These linkages

may form an important part of the ROA project, providing easily measurable

contributions. In addition, the associated agribusiness industries and firms provide a

ready made interest group able to lobby, argue and articulate the economic importance

of primary producers.

Agriculture’s economic contributions as social welfare infrastructure

Moving further to the right in Figure 1 are a number of economic roles that are

provided by agriculture as semi-externalities or public goods. These are functions

which may not exist without agricultural production, but which producers are not

compensated. For instance, agriculture provides a number of welfare enhancing,

‘income’ transfer and income-shock buffer functions. For instance, a recession or

externally-induced income shock or financial crisis affects households differently,

varying across sector of employment, level of wealth, geographic location, gender,

and various other factors. Household and community welfare is effected through

changes in relative prices, in aggregate labour demand, in the rates of returns on

assets, changes in public transfers, and in the community environment --in terms of

public health or public safety (Ferreira, 1999). During a crisis, agriculture can act as a

buffer, safety net, and as an economic stabiliser (FAO, 2001).

In this way, the agriculture sector can provide a substitute for a welfare system in

those countries unable to provide unemployment insurance or other types of social

services for retiring workers and employees who lose their jobs during structural

change or income shocks. Because primary agriculture tends to be relatively flexible

regarding both the scale of operations and technology, some of the non-agricultural

unemployment caused by a severe income shock can be re-absorbed into agricultural

activities.

Agriculture tends to provide a much wider range of substitutability among factors of

production especially labour and capital, than is the case in much of industry. This

social welfare role often acts as the most important buffer between ‘poverty’ and full

blown chronic undernutrition. Thus this buffer role of agriculture keeps income

distribution within reasonable bounds to help ensure that some of the poor do not fall

below the nutrition threshold.

In addition, agriculture operates as important social welfare infrastructure in remote

locations, creating development opportunities and producing basic necessities for

isolated communities. Agriculture provides basic subsistence occupations for millions

and permits people to supply themselves with the three fundamental human needs:

food, clothing and shelter. National accounting measures too often fail to reflect the

true value of this production and capital creation within agriculture because much of it

does not enter the market as monetized values. Consequently, agriculture is often

downgraded and under recognized.

In a similar vein, agricultural workers bear many of the costs of structural change

during times of strong economic growth. If rural producers are to share in the benefits

of growth, many must leave the countryside and farming. If there were no reduction in

farm employment as economic growth occurs, most of the gains would not be

realized. For example, if primary production employment in the Australia, Canada, the

EU and the US were as high today as it was thirty years ago, the income earned in

farming would be far less. Migrations costs are borne by the migrants, including the

actual cost of moving, finding a job, locating housing, and the psychological costs of

leaving familiar conditions for conditions that are strange and, in some ways,

threatening (Johnston, 1998).

Agriculture’s economic contribution through rapid productivity growth

Over time, agriculture remains more productive than industry so the real price of food

declines, contributing to: increased savings; increased incomes; economic stability;

and overall total factor productivity. Historically, agricultural productivity growth has

been even faster than productivity growth in manufacturing. Farm productivity growth

in the agricultural-exporting rich countries has been comparatively very rapid. In the

United States, for example, total factor productivity growth since the late 1940s has

been nearly four times as fast in farming as in the private non-farm sectors (Jorgenson

and Gollop 1992), and similar performances have been found in Australia and Canada

(Martin and Mitra, 1998). As well, new technologies are capable of making food safer

and raising its quality, and of reducing any harm to the environment caused by

farming. These properties are valued more and more as people's incomes grow and as

the natural environment comes under stress.

In low-income countries where people spend a high proportion of their income on

food, even small food price increases can be detrimental to the well-being of the urban

poor and rural net-food purchasers. Many of the poorest people in low-income

countries also depend on agriculture (directly and indirectly) for their livelihoods, and

rising crop prices may actually increase their real incomes and food intake.

Agriculture’s economic contribution to alleviating poverty

Past evidence suggests that periods of high agricultural growth rates are associated

with falling rural poverty (Binswanger and von Braun, 1991; Timmer, 1992; Bell and

Rich, 1994; Johnson, 1998; Mellor, 2001). Strong agricultural growth leads to: (1)

lower food prices (for urban consumers and rural net-food buyers); (2) increased

income generating opportunities for food producers and jobs for rural workers (thus

reducing rural-urban migration, with positive consequences for real urban wage rates);

and (3) positive intersectoral spillover effects including migration, trade and enhanced

productivity (Lipton and Ravallion, 1995; Timmer, 1992).

A World Bank review concludes that higher agricultural and rural growth rates are

likely to have a ‘strong, immediate, and favourable impact’ on poverty (World Bank

1996). The review notes that agricultural growth rates exceeding 3 percent a year

produce a decline in the World Bank’s poverty index grouping by more than 1

percent. In no case did poverty decline when agricultural growth was less than 1

percent (World Bank 1996). Even the most populated countries have had great

success. In both China and Indonesia, for example, rapid agricultural growth

substantially reduced rural poverty, improved food security in both rural and urban

sectors, and provided a significant demand side stimulus for non-agricultural goods

and services. No country has been able to sustain the process of rapid economic

growth without solving its problems of marcro food security (Timmer et al, 1983;

World Bank, 1996).

In contrast, countries failing to make progress in agricultural growth experience

stagnating rural sectors, sluggish overall economic growth with declining per caput

incomes, and falling investment in rural services and agricultural infrastructure

(Binswanger and Landell-Mills 1995; FAO 1996). In addition, while rural growth has

important impacts on urban poverty reduction, urban growth has much less impact on

urban poverty reduction (Mellor, 2001).

Agriculture’s economic contribution to labour productivity througheducation

Agriculture’s role in providing jobs, income and food contribute indirectly to

education which in turn provide private and public benefits. The better the education,

the more opportunities for a higher-paying job and the ability to be well-nourished and

to work more, earn more, consume more and save more. Agriculture contributes to

these increased incomes by enhancing food security (production and access via

increased incomes). As incomes increase for subsistence and other rural households,

families increasingly spend to educate their children. Thus rural households contribute

to the overall education and productivity levels of those children who migrate to

cities.

Improving access to food increases learning capacity and school performance and

leads to longer school attendance, fewer school (and work days) lost to sickness,

higher earnings, longer work lives and a more productive work force. These are

essential to economic growth. And economic growth is essential for increasing

incomes and reducing poverty. The manner in which development strategies achieve

growth, however, and the number of people who participate in and benefit from it are

as important as the growth itself.

In contrast, chronic malnutrition kills, blinds, and otherwise debilitates, reducing

physical capacity, lowering productivity, stunting growth, and inhibiting learning. In

the world’s poorest regions and countries, one-third of deaths among children are due

to malnutrition (Del Rosso 1992). Improving access to food and nutrition increases

learning capacity and school performance and leads to longer school attendance, fewer

school and work days lost to sickness, higher earnings, longer work lives and a more

productive work force.

Markets frequently do not reflect the social value of education, research and training.

Agriculture contributes indirectly to education and education is a classic example

where the benefits of increased education to society are higher than the benefits of that

education to an individual. In the case of women, the social returns to investment in

education are higher still. Investing in human capital remains one of the most

important keys to reduce poverty and bring about sustainable economic growth. Few

measures contribute more to economic development and poverty alleviation than

investing in women (World Bank, 1990; Kaito, 1994).

Education, training and access to information are directly linked to productivity and

aggregate output. A study of the determinants of real GDP covering 58 countries

during 1960-85 suggests that an increase of one year in average years of education

may lead to a three percent rise in GDP (World Bank, 1990). Virtually all studies on

agricultural productivity show that better educated farmers get a higher return on their

land. According to one study, African farmers who have completed four years of

education - the minimum for achieving literacy - produce, on average, about 8 percent

more than farmers who have not gone to school. Studies in Malaysia, Republic of

Korea and Thailand confirm that schooling substantially raises farm productivity

(World Bank, 1990).

A World Bank study estimates that the rate of return on investments in women’s

education is of the order of 12 percent in terms of increased productivity (Kaito,

1994). If women and men received the same education, says the study, farm-specific

yields would increase from seven percent to 22 percent. Increasing women’s primary

schooling alone would increase agricultural output by 24 percent (Kaito, 1994).

Women’s education also typically pays off in wage increases, with a consequential

rise in household incomes. According to a recent ILO report, each additional year of

schooling has been shown to raise a woman’s earnings by about 15 percent compared

with 11 percent for a man (Lim, 1996). Female education also has major social

returns, contributing to improved household health and welfare, lower infant and child

mortality, and slower population growth (Subbarao and Raney, 1995).

Agriculture’s economic contributions to health and food safety

Food consumers, whether motivated by green concerns or by concerns for health and

food safety, are increasingly interested in where food comes from and how it is

produced, processed, packaged and distributed. These health and food safety issues,

(together with environmental quality) are often equated to superior goods, helping to

explain why national preferences for private versus public goods consumption is a key

factor influencing production, consumption and trade patterns. Relatively high-income

economies have low income elasticity of demand for goods and services related to

sustenance and it declines as income continue to rise. On the other hand, the income

elasticity of demand for more environmental amenities is high and continues to rise.

This stands is in sharp contrast to poorer countries where the income elasticity of

demand is high for sustenance and low for environmental amenities.

Empirical studies confirm these trends. While economic growth involves increased

pollution associated with production and consumption, rising per capita incomes mean

that societies demand more environmental quality and more income is available to

protect environmental services (World Bank, 1992; Seldon and Song, 1994;

Grossman and Krueger, 1995; and Hettige, et. al. 1998). This does not imply,

however, that lower-income countries desire environmental quality less or have a low

income elasticity of demand for environmental amenities, nor that income elasticity

rises inexorably with income. But it is consistent with the fact that people in relatively

wealthy countries have greater capacity to pay for more of everything, including

higher environmental quality (Anderson, 1992; Stringer and Anderson, 1999).

Like environmental goods, consumer demand for quality attributes in general and for

food safety in particular are superior goods. Demand increases faster with income than

does demand for food in terms of quantity. Consumers in wealthier countries

demonstrate an increasing interest in food characteristics which go beyond nutritional

properties and which respond to three types of utility: health, pleasure and ethics

(Mahé and Ortalo-Magné, 1998). Pleasure is essentially a private goods. Consumers

derive satisfaction related to the hedonistic characteristics of the product itself. Health

and safety have both private and public good aspects. Ethics suggests utility can be

affected by production and processing methods.

The recent problems with BSE and with foot and mouth disease in the EU highlight

the private and public values of animal health and safe food, including the costs

associated with not supplying it.

What has been done so far to study and address these issues?

The references in the six issues presented above show only a small fraction of the

available documentation for these types of non-traditional economic benefits. Most

countries being considered for analysis in the ROA would have large literatures to

draw on. Few studies, however, provide a big picture overview which enables

synthesis and comparisons (the aim of the ROA).

An exception is recent research motivated by ‘non-trade’ concerns with respect to

agriculture and the environment acknowledge the fact that agriculture pollutes, but

that agriculture can contribute simultaneously in positive ways to the environment

(OECD, 1997). A series of studies emerged from these issues to identify various non-

production benefits now commonly called multifunctionality (See Runge, 1999; and

Anderson 200b for important examples).

The issue of multifunctionality is not a new one, but it has attracted more attention in

recent years. In addition to OECD, the WTO Committee on Agriculture highlights

that some agricultural functions: (1) often have public goods characteristics; (ii) are

often specific to the agricultural sector; and (iii) are to a large extent provided as joint

products of the agricultural production activity itself. Some WTO member countries

have suggested specific examples, including agriculture’s contribution to food

security, the viability and development of rural areas, cultural heritage, the agricultural

landscape, agro-biological diversity, land conservation and a healthy plant, animal and

people (Norway, 1999). The question concerning a multifunctional agriculture has

resulted in debate over whether multifunctionality should be rejected or accepted as a

reason for protecting domestic agricultural production.

The joint production relationship is complex and may relate both to certain types of

input use, farming practices and technologies, and agricultural output, as well as a

combination of all these elements. For instance, an authentic agricultural landscape

cannot be provided without agricultural production activity. Moreover, as part of a

country’s long-term food security, a certain degree of domestic food production may

be judged as essential (Norway, 1999; Timmer, 1995).

Timmer (1995) makes several points regarding how markets fail to provide incentives

for agriculture’s non-production benefits. First, international prices do not reflect the

importance attached by most countries to maintaining food security. Second,

agriculture plays a special role in alleviating poverty in most Third World nations.

Third, market prices for agricultural commodities undervalue the indirect effects of

agricultural growth on providing resources for overall investment and for increasing

overall total factor productivity. Fourth, governments need to learn how to make a

market economy work and the agricultural sector offers an ideal environment within

which learning by doing can effectively occur.

How do we capture, measure and promote agriculture’s economicroles?

Agriculture is related to the nonfarm rural sector, the urban sector, and the rest of the

world in complex relationships that continually evolve. The output of agriculture is

not homogeneous. It consists of many different products, goods and services that are

used as food, as raw materials by industry, as exports, as social infrastructure, as

productivity enhancing nutrition, as rural amenities and other related non commodity

specific benefits.

The policy implication of the earlier conception of agriculture as handmaiden to

industry was straightforward. An understanding of the diverse nature of agriculture’s

economic contributions involves recognizing its many linkages and their dynamic

effects on rising incomes, overall development, urban migration, poverty, non-

agricultural growth, wealth and income distribution, as well as how agricultural,

nonagricultural, macroeconomic, and trade policies influence agricultural growth and

linkages.

The conceptual approach to analyzing the economic roles of agriculture presented in

Figure 1 suggest first measuring the direct, non-traditional economic roles of

agriculture. A qualitative and quantitative approach to non traditional economic roles

may be useful to help capture the various functions, benefits and values . A narrative

approach would involve analyzing the economic roles of agriculture in contributing to

agribusiness, local trade and service firms, and the social structure of rural

communities; the likely influence of new technology and economic stress on the

organization and control of agricultural resources; the relative importance of

agriculture in the economic base of rural areas, competition for resources between

agriculture and other components of the rural economy, with emphasis on land use

changes on the urban fringe, competing demands for natural resources (eg water in

arid regions), and competition for labour resources between agriculture and other rural

activities; and the importance of off-farm employment and income for farm families

(SOFA, 1997).

A social accounting matrix (SAM) provides a straightforward way to explore how

agricultural sectors generate the direct use of non-traditional contributions (Figure 1)

to overall economy. SAMs summarizes aggregate structural interrelationships among

the various agents in an economy by mapping the circular flows of income and

expenditures, and supply of goods and services. SAM entries represents the payment

by one account to another account for services rendered or goods supplied. It can also

represent an income transfer for jobs.

SAM data requirements are not problematic for most developing countries. In

addition, a great deal of information can be obtained from the Global Trade Analysis

Project (GTAP) data base. For example, GTAP offers the ability to look at land: (a)

land, labour and capital; (b) processed agricultural goods; (c) non agricultural inputs

used by agriculture; (d) agricultural goods used for the production of other agricultural

goods (e) agricultural outputs used by non agricultural sectors as inputs; (f) domestic

consumption; and (g) exports.

These data present a host of opportunities for analyzing the sector’s non traditional,

direct contributions. One issue with GTAP will be the availability and the quality of

country data from Africa. The upcoming version, GTAP V5, due out in April should

provide an improved data base over past years.

Identifying and measuring the indirect economic contributions are difficult and

present a number of well-known issues. It may be useful in some countries, to take a

specific public goods or externalities (the outputs, or lost potential of that output) and

attempt to measure its value with accessible market valuation techniques. For

example, value added and labour measurements (eg contribution to rural viability via

tourism); production function or human capital techniques (eg productivity increases

via improved education outcomes); replacement cost techniques (eg social welfare

infrastructure substitute and poverty reduction potential).

Some additional issues for discussion

An important issue is not to over generalize about agriculture's role. National

differences conceal great disparities in agricultural structure, the relative importance

of agricultural to the rural economy and national development, resource use conflicts

and the prevalence of off-farm employment, both among regions and among farm

types.

Since tastes and preferences change over time and differ between countries, so too

will society’s valuation of those non-marketed products. And as technologies,

institutions, policy experiences and market sizes change in the process of

development, so does the scope for being able to market some of those previously

unmarketable products that were jointly produced with each sector’s main products

Every productive sector generates both marketed and non-marketed products. Some of

those non-marketed products are considered more desirable than others, and some are

considered undesirable. Anderson (2000) raises important policy questions related to

agriculture’s non-market contributions. Is agricultural production a net contributor in

terms of externalities and public goods? And is it more of a net contributor than other

sectors and especially the sectors that would expand if agricultural supports were to

shrink? Demonstrating that is an almost impossible task, given the difficulties in

obtaining estimates of society’s ever-changing (a) evaluation of the myriad

externalities and public goods generated by the economy’s various sectors and (b)

marginal costs of their provision.

All market failures associated with agriculture in the developed countries are

replicated in the developing ones, but the incapacity to intervene effectively to

regulate is even more evident and more problematic.

Gardner (2001) points out several of the long standing controversial issues in the

interlinked causes and effects of economic growth of agriculture that may be

important for ROA policy development. The list includes: (a) understanding the

sources of improvements in technology; (b) explaining the adoption of new

technology; (c) understanding the reasons for changes in the economic organization of

farm enterprises; (d) the economic consequences of technological and organizational

change, particularly the effects on agricultural productivity, farm size, and income

distribution; (e) the role of market integration between the farm and nonfarm

economies, particularly with respect to labour markets -- both migration off farms and

nonfarm sources of income for people who remain on farms; and (f) the role of

government, and more generally, economic incentives, in fostering the creation and

adoption of new technology and the development of changes in the economic

organization of agriculture (Gardner, 2001).

References

Anderson, K. (2000a). ‘Towards and APEC Food System’, Report prepared for NewZealand's Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Wellington, February 2000. Sincepublished on New Zealand government's web site athttp://www.mfat.govt.nz/images/apecfood.pdf.

Anderson, Kym, (2000b) ‘Mulifunctionality' and the WTO’, Australian Journal ofAgricultural and Resource Economics, 44(3): 475-96.

Adelman, I. (1984). ‘Beyond Export-Led Growth’. World Development, 12, 9, 937--49.

Bautista, R. and A. Valdés. (1993). The Bias against Agriculture: Trade andMacroeconomic Policies in Developing Countries, San Francisco: ICS Press.

Bell, C. and R. Rich. (1994). ‘Rural Poverty and Agricultural Performance in Post-Independence India’, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 56(2), pp., 111-133.

Binswanger, H.P. and von Brahn, 1991, ‘Technological Change andCommercialization in Agriculture: The Effect on the Poor’, World Bank ResearchObserver; 6(1), January 1991, pp. 57-80.

Binswanger, H.P. and P. Landell-Mills. (1995) ‘The World Bank’s Strategy forReducing Poverty and Hunger.’ Environmentally Sustainable Development Studies andMonographs Series No. 4. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

Cooper, J. (2001) The Environmental Roles of Agriculture in Developing Countries.Paper prepared for FAO consultation on the Roles of Agriculture in Development, 19-21March 2001, Rome.

Davis, John and Goldberg, Ray. A Concept of Agribusiness. (1957). Chapter 3:‘Agribusiness and Input-Output Economics’

de Janvry, A. (1984). ‘Searching for Styles of Development: Lessons from LatinAmerica and Implications for India’, Working Paper No. 357, Department ofAgricultural and Resource Economics, University of California, Berkeley.

Delgado, C. et al. (1994). Agricultural Growth Linkages in Sub-Saharan Africa,Washington D.C.: US Agency for International Development.

Del Rosso, H. (1992). “Investing in Nutrition with World Bank Assistance”,Washington D.C.: World Bank.

FAO (1996). Food Agriculture and Food Security, The Global Dimension”,WFS96/Tech/1. Rome: FAO.

FAO (1997). ‘The agroprocessing industry and economic development’, SOFASpecial Chapter, FAO: Rome.

Fei, J. C. and Ranis, G. (1961). ’A Theory of Economic Development’, AmericanEconomic Review, 51, 4, 533--65.

Ferreira, F., G. Prennushi and M. Ravallion. ( ) Protecting the Poor fromMacroeconomic Shocks: An Agenda for action in a crisis and beyond World Bank,Washington, DC.

Gardner, B. (2001) How U.S. Agriculture Learned to Grow: Causes andConsequences, Allan Lloyd Address, AARES 2001 Conference, Adelaide.

Grossman, G.M. and A.B. Krueger. 1995. “Economic Growth and the Environment,”Quarterly Journal of Economics 110(2): 353-377, May.

Hayami, Y. and V. Ruttan. (1971). Agricultural Development: An InternationalPerspective, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

Hettige, H., M. Mani and D. Wheeler. 1998. "Industrial Pollution in EconomicDevelopment (Kuznets Revisited)" Paper presented at a World Bank conference onTrade, Global Policy and the Environment, Washington, D.C., 21-22 April

Hirschman, A. O. (1958). The Strategy of Economic Development, Yale UniversityPress, New Haven, Connecticut. In Developing Countries, Washington D.C.

Johnson D. Gale. (1998). China's rural and agricultural reforms in perspective, Paperprepared for presentation at the Land Tenure, Land Market, and Productivity in RuralChina Workshop, Beijing May 15-16.

Johnson, D. Gale. (1998). ‘Food Security and World Trade Prospects’, AmericanJournal of Agricultural Economics, Vol 80, No. 5, pp. 941-947.

Johnston, B.F., and J.W. Mellor. (1961). "The Role of Agriculture in EconomicDevelopment." Amer. Econ. Rev. 51, September, pp. 566-93.

Jorgenson, D. G. (1961). ’The Development of a Dual Economy’, Economic Journal,71, 309--34.

Jorgenson, D.W. and F.M. Gollop. (1992). 'Productivity Growth and US Agriculture:A Postwar Perspective', American Journal of Agricultural Economics 74(3): 745-56,August.

Kalecki, M. (1971). Selected Essays on the Dynamics of the Capitalist Economy1933-1970, Cambridge University Press: London.

Kureger, A.O., M. Schiff and A.. Valdes. (1991). ‘Agricultural Incentives InDeveloping Countries: Measuring the Effects of Sectoral and Economy WidePolicies’, World Bank Economic Review, 2, pp. 255-271.

Kuznets, S. (1968). Toward a Theory of Economic Growth with Reflections on theEconomic Growth of Nations, Norton, New York.

Lee, K. (2001) The Food Security Roles of Agriculture in Development. Paperprepared for FAO consultation on the Roles of Agriculture in Development, 19-21March 2001, Rome.

Lewis, W.A. (1954). ‘Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour’,Manchester School of Economics, 20, 139-91.

Lim, Lin. (1996). ‘Women Swell Ranks of Working Poor’, World of Work, Vol 17,Geneva: ILO.

Lipton, M. and M. Ravallion. (1995). ‘Poverty and Policy.’ In J. Behrman and T.N.Srinivasan, eds., Handbook of Development Economics Vol IIIB, Amsterdam: ElsevierScience B.V.

Mahé L.P. and F. Ortalo-Magné. (1998). International co-operation in the regulationof food quality and safety attributes, OECD Workshop on Emerging Trade Issues inAgriculture Emerging Trade Issues in Agriculture to be held in Paris 26-27 October1998, OECD: Paris.

Martin, W. and D. Mitra (1998). ‘Productivity Growth and Convergence inAgriculture and Manufacturing’, mimeo, Development Research Group, the WorldBank, Washington, D.C., June.

Mellor, J. (1966). The Economics of Agricultural Development. Ithaca NY: CornellUniversity Press.

Mellor, J. (1976). The New Economics of Growth: A Strategy for India and theDeveloping World, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York.

Mellor, J. (2001). Reducing poverty, Buffering Economic Shocks – Agriculture andthe Non-Tradable Economy. Paper prepared for FAO consultation on the Roles ofAgriculture in Development, 19-21 March 2001, Rome.

Newman, M. D., R. Abbott, Liana C. Neff, J. Yeager, M. Menegay, D. Hughes, and J.Brown. (1989). ‘Agribusiness Development in Asia and the Near East’, AgriculturalMarketing Improvement Strategies Project, Abt Associates Inc., Washington, D.C.

Norway. (1999). ‘Appropriate Policy Measure Combinations to Safeguard Non-TradeConcerns of a Multifunctional Agriculture,’ Paper presented by Norway to theInformal Process of Analysis and Information Exchange of the WTO Committee onAgriculture, 28 September 1999.

OECD. (1997). Environmental Benefits from Agriculture: Issues and Policies (TheHelsinki Seminar), Paris: OECD.

Oram, P.(1995). ‘The potential of technology to meet world food needs in 2020’,International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC, April.

Pinstrup-Anderson, Per. (1994). ‘World food trends and future food security’, FoodPolicy Statement, No. 18, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington,D.C., March.

Ranis, G. (1984). ‘Typology in Development Theory: Retrospective and Prospects’, inM. Syrquin, L. Taylor and L. Westphal (eds), Economic Structure and Performance:Essays in Honor of Hollis B. Chenery, Academic Press: New York.

Rosenstein-Rodan, P. N. (1943). ‘Problems of Industrialization of Eastern and South-Eastern Europe’, Economic Journal, 53, 202--11.

Runge, C.F. (1999). Beyond the Green Box: A Conceptual Framework forAgricultural Trade and the Environment, Working Paper WP((-1, Center forInternational Food and Agricultural Policy, University of Minnesota.

Saito, Katrine A. (1994). ‘Raising the Productivity of Women Farmers in Sub-SaharanAfrica’, World Bank Discussion Paper 230, Africa Technical Department Series,Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Seldon, T.M. and D. Song. 1994. "Environmental Quality and Development: Is Therea Kuznets Curve for Air Pollution Emissions?" Journal of Environmental Economicsand Management 27(2): 147-62, September.

Scitovsky, T. (1954). ’Two Concepts of External Economies’, Journal of PoliticalEconomy, 62, 143--51.

Pryor, S. and T. Holt. (1999). ‘Agribusiness As An Engine Of Growth Social Studies’,22, 2, 139--81.

Singer, H. (1979). ‘Policy Implications of the Lima Target’, Industry andDevelopment, 3, 17--23.

Southworth, H.M., and B.F. Johnston, eds. (1967). Agricultural Development andEconomic Growth. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press,.

Stringer, R. and Kym Anderson. (1999). ‘International Developments and SustainableAgriculture in Australia’, Australian Agribusiness Review 7(2) June.

Subbarao, K. and L. Raney, (1995). ‘Social Gains From Female Education: A Cross-National Study’, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 44 (1), October.

Timmer, C.P., (1992). ‘Agriculture and Economic Development Revisited’,Agricultural Systems, 40:21-58.

Timmer, C.P. (1995). Getting agriculture moving: do markets provide the rightsignals? Food Policy, vol 20, No. 5 p 455-472.

Timmer, C.P., W. Falcon and S. Pearson. (1983). Food Policy Analysis, Baltimore:Johns Hopkins Press.

Vogel S. (1994). Structural changes in agriculture: production linkages andagricultural demand-led industrialization. Oxford Economic Papers Jan 1994 v46 n1p136-157.

World Bank. (1990). World Development Report, Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

World Bank. 1992. “Development and the Environment.” World DevelopmentReport 1992, Washington D.C.: World Bank.

World Bank. (1996). Reforming agriculture: The World Bank goes to market,Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Table 1 Share of Agriculture and agribusiness in GDP

Country Share of GDP______________________________________Agriculture Agriculture-

relatedmanufacturingand services

Allagribusiness

Share ofmanufacturingand services inagribusiness

……………………..percent……………..……..Philippines 22 38 60 70India 31 45 76 60Malaysia 17 26 43 73Indonesia 19 29 48 63Thailand 12 37 49 79Republic of Korea 7 22 29 82Chile 7 25 32 79Argentina 6 20 26 73Brazil 8 18 26 79Mexico 7 19 26 75United States 2 4 8 91

Source: Pryor and Holt, 1999).

Agriculture’s Economic Roles

Direct Use Contributions

Traditional

Indirect Use Contributions

Non traditionalExternalities Public Goods

FoodSurplus labourExportsCapital/savings transfersConsumer markets

Produce agroindustrial goodsProduce agroindustrial servicesProduce agroindustrial jobsProvide land for urban expansionProvide safe foodTourism

Provide safe foodTourism

Provide safe foodMore productive work forceWelfare system substituteProductivity growthRural viabilityRecreational amenitiesCultural and heritage valuesLandscape valuesEquity contributionEnhanced learning capacityProvide community spaceHarbour unique ecosystems

Increasingly less tangible values to society; and increasingly more difficult to measure contributions

Food SecurityEnvironmental goodsand services

Joint Products

CIES DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES

The CIES Discussion Paper series provides a means of circulating promptly papers ofinterest to the research and policy communities and written by staff and visitors associatedwith the Centre for International Economic Studies (CIES) at the Adelaide University. Itspurpose is to stimulate discussion of issues of contemporary policy relevance among non-economists as well as economists. To that end the papers are non-technical in nature andmore widely accessible than papers published in specialist academic journals and books.(Prior to April 1999 this was called the CIES Policy Discussion Paper series. Since then theformer CIES Seminar Paper series has been merged with this series.)

Copies of CIES Policy Discussion Papers may be downloaded from our Web site athttp://www.adelaide.edu.au/cies/ or are available by contacting the Executive Assistant,CIES, School of Economics, Adelaide University, SA 5005 AUSTRALIA. Tel: (+61 8) 83035672, Fax: (+61 8) 8223 1460, Email: [email protected]. Single copies are free onrequest; the cost to institutions is US$5.00 overseas or A$5.50 (incl. GST) in Australia eachincluding postage and handling.For a full list of CIES publications, visit our Web site at http://www.adelaide.edu.au/cies/or write, email or fax to the above address for our List of Publications by CIES Researchers,1989 to 1999 plus updates.0118 Stringer, Randy, "How important are the 'non-traditional' economic roles agriculture

in development?" April 2001.0117 Bird, Graham, and Ramkishen S. Rajan, "Economic Globalization: How Far and

How Much Further?" April 2001. (Forthcoming in World Economics, 2001.)0116 Damania, Richard, "Environmental Controls with Corrupt Bureaucrats," April 2001.0115 Whitley, John, "The Gains and Losses from Agricultural Concentration," April 2001.0114 Damania, Richard, and E. Barbier, "Lobbying, Trade and Renewable Resource

Harvesting," April 2001.0113 Anderson, Kym, " Economy-wide dimensions of trade policy and reform," April

2001. (Forthcoming in a Handbook on Developing Countries and the Next Round ofWTO Negotiations, World Bank, April 2001.)

0112 Tyers, Rod, "European Unemployment and the Asian Emergence: Insights from theElemental Trade Model," March 2001. (Forthcoming in The World Economy, Vol.24, 2001.)

0111 Harris, Richard G., "The New Economy and the Exchange Rate Regime," March2001.

0110 Harris, Richard G., "Is there a Case for Exchange Rate Induced ProductivityChanges?", March 2001.

0109 Harris, Richard G., "The New Economy, Globalization and Regional TradeAgreements", March 2001.

0108 Rajan, Ramkishen S., "Economic Globalization and Asia: Trade, Finance andTaxation", March 2001. (Forthcoming in ASEAN Economic Bulletin, 18(1), April2001.)

0107 Chang, Chang Li Lin, Ramkishen S. Rajan, "The Economics and Politics ofMonetary Regionalism in Asia", March 2001. (Forthcoming in ASEAN EconomicBulletin, 18(1), April 2001.)

0106 Pomfret, Richard, "Reintegration of Formerly Centrally Planned Economies into theGlobal Trading System", February 2001. (Forthcoming in ASEAN Economic

Bulletin, 18(1), April 2001).0105 Manzano, George, "Is there any Value-added in the ASEAN Surveillance Process?"

February 2001. (Forthcoming in ASEAN Economic Bulletin, 18(1), April 2001).0104 Anderson, Kym, "Globalization, WTO and ASEAN", February 2001. (Forthcoming in

ASEAN Economic Bulletin, 18(1): 12-23, April 2001).0103 Schamel, Günter and Kym Anderson, "Wine Quality and Regional Reputation:

Hedonic Prices for Australia and New Zealand", January 2001. (Paper presented atthe Annual Conference of the Australian Agricultural and Resource EconomicsSociety, Adelaide, 23-25 January 2001.)

0102 Wittwer, Glyn, Nick Berger and Kym Anderson, "Modelling the World Wine Marketto 2005: Impacts of Structural and Policy Changes", January 2001. (Paperpresented at the Annual Conference of the Australian Agricultural and ResourceEconomics Society, Adelaide, 23-25 January 2001.)

0101 Anderson, Kym, "Where in the World is the Wine Industry Going?" January 2001.(Opening Plenary Paper for the Annual Conference of the Australian Agriculturaland Resource Economics Society, Adelaide, 23-25 January 2001.)

0050 Allsopp, Louise, "A Model to Explain the Duration of a Currency Crisis", December2000.(Forthcoming in International Journal of Finance and Economics)

0049 Anderson, Kym, "Australia in the International Economy", December 2000.(Forthcoming as Ch. 11 in Creating an Environment for Australia's Growth, editedby P.J. Lloyd, J. Nieuwenhuysen and M. Mead, Cambridge and Sydney: CambridgeUniversity Press, 2001.)

0048 Allsopp, Louise, " Common Knowledge and the Value of Defending a FixedExchange Rate", December 2000.

0047 Damania, Richard, Per G. Fredriksson and John A. List, "Trade Liberalization,Corruption and Environmental Policy Formation: Theory and Evidence", December2000.

0046 Damania, Richard, "Trade and the Political Economy of Renewable ResourceManagement", November 2000.

0045 Rajan, Ramkishen S., Rahul Sen and Reza Siregar, "Misalignment of the Baht,Trade Imbalances and the Crisis in Thailand", November 2000.

0044 Rajan, Ramkishen S., and Graham Bird, "Financial Crises and the Composition ofInternational Capital Flows: Does FDI Guarantee Stability?", November 2000.

0043 Graham Bird and Ramkishen S. Rajan, "Recovery or Recession? Post-DevaluationOutput Performance: The Thai Experience", November 2000.

0042 Rajan, Ramkishen S. and Rahul Sen, "Hong Kong, Singapore and the East AsianCrisis: How Important were Trade Spillovers?", November 2000.

0041 Li Lin, Chang and Ramkishen S. Rajan, "Regional Versus Multilateral Solutions toTransboundary Environmental Problems: Insights from the Southeast Asian Haze",October 2000. (Forthcoming in The World Economy, 2000.)

0040 Rajan, Ramkishen S., "Are Multinational Sales to Affiliates in High Tax CountriesOverpriced? A Simple Illustration", October 2000. (Forthcoming in EconomiaInternazionale, 2000.)

0039 Ramkishen S. Rajan and Reza Siregar, "Private Capital Flows in East Asia: Boom,Bust and Beyond", September 2000. (Forthcoming in Financial Markets andPolicies in East Asia, edited by G. de Brouwer, Routledge Press)

0038 Yao, Shunli, "US Permanent Normal Trade Relations with China: What is at Stake?A Global CGE Analysis", September 2000.