How do we heal medicine? · are losing their core focus: actually treating people. Doctor and...

Transcript of How do we heal medicine? · are losing their core focus: actually treating people. Doctor and...

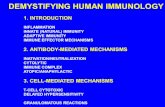

1

How do we heal medicine? March 2012, by Atul Gawande http://www.ted.com/talks/atul_gawande_how_do_we_heal_medicine/transcript?language=en

Our medical systems are broken. Doctors are capable of extraordinary (and expensive) treatments, but they are losing their core focus: actually treating people. Doctor and writer Atul Gawande suggests we take a step back and look at new ways to do medicine — with fewer cowboys and more pit crews.

Section 1 0:00 I got my start in writing and research as a surgical trainee, as someone who was a long ways away from becoming any kind of an expert at anything. So the natural question you ask then at that point is, how do I get good at what I’m trying to do? And it became a question of, how do we all get good at what we’re trying to do? Section 2 0:36 It’s hard enough to learn to get the skills, try to learn all the material you have to absorb at any task you’re taking on. I had to think about how I sew and how I cut, but then also how I pick the right person to come to an operating room. And then in the midst of all this came this new context for thinking about what it meant to be good. Section 3 0:58 In the last few years we realized we were in the deepest crisis of medicine’s existence due to something you don’t normally think about when you’re a doctor concerned with how you do good for people, which is the cost of health care. There’s not a country in the world that now is not asking whether we can afford what doctors do. The political fight that we’ve developed has become one around whether it’s the government that’s the problem or is it insurance companies that are the problem. And the answer is yes and no; it’s deeper than all of that. Section 4 1:43 The cause of our troubles is actually the complexity that science has given us. And in order to understand this, I’m going to take you back a couple of generations. I want to take you back to a time when Lewis Thomas was writing in his book, “The Youngest Science.” Lewis Thomas was a physician-writer, one of my favorite writers. And he wrote this book to explain, among other things, what it was like to be a medical intern at the Boston City Hospital in the pre-penicillin year of 1937. It was a time when medicine was cheap and very ineffective. If you were in a hospital, he said, it was going to do you good only because it offered you some warmth, some food, shelter, and maybe the caring attention of a nurse. Doctors and medicine made no difference at all. That didn’t seem to prevent the doctors from being frantically busy in their days, as he explained. Section 5 2:52 What they were trying to do was figure out whether you might have one of the diagnoses for which they could do something. And there were a few. You might have a lobar pneumonia, for example, and they could give you an antiserum, an injection of rabid antibodies to the bacterium streptococcus, if the intern sub-typed it correctly. If you had an acute congestive heart failure, they could bleed a pint of blood from you by opening up an arm vein, giving you a crude leaf preparation of digitalis and then giving you oxygen by tent. If you had early signs of paralysis and you were really good at asking personal questions, you might figure out that this paralysis someone has is from syphilis, in which case you could give this nice concoction of mercury and arsenic--as long as you didn’t overdose them and kill them. Beyond these sorts of things, a medical doctor didn’t have a lot that they could do.

2

Section 6 4:04 This was when the core structure of medicine was created--what it meant to be good at what we did and how we wanted to build medicine to be. It was at a time when what was known you could know, you could hold it all in your head, and you could do it all. If you had a prescription pad, if you had a nurse, if you had a hospital that would give you a place to convalesce, maybe some basic tools, you really could do it all. You set the fracture, you drew the blood, you spun the blood, looked at it under the microscope, you plated the culture, you injected the antiserum. This was a life as a craftsman. Section 7 4:46 As a result, we built it around a culture and set of values that said what you were good at was being daring, at being courageous, at being independent and self-sufficient. Autonomy was our highest value. Go a couple generations forward to where we are, though, and it looks like a completely different world. We have now found treatments for nearly all of the tens of thousands of conditions that a human being can have. We can’t cure it all. We can’t guarantee that everybody will live a long and healthy life. But we can make it possible for most. Section 8 5:33 But what does it take? Well, we’ve now discovered 4,000 medical and surgical procedures. We’ve discovered 6,000 drugs that I’m now licensed to prescribe. And we’re trying to deploy this capability, town by town, to every person alive--in our own country, let alone around the world. And we’ve reached the point where we’ve realized, as doctors, we can’t know it all. We can’t do it all by ourselves. Section 9 6:11 There was a study where they looked at how many clinicians it took to take care of you if you came into a hospital, as it changed over time. And in the year 1970, it took just over two full-time equivalents of clinicians. That is to say, it took basically the nursing time and then just a little bit of time for a doctor who more or less checked in on you once a day. By the end of the 20th century, it had become more than 15 clinicians for the same typical hospital patient--specialists, physical therapists, the nurses. Section 10 6:50 We’re all specialists now, even the primary care physicians. Everyone just has a piece of the care. But holding onto that structure we built around the daring, independence, self-sufficiency of each of those people has become a disaster. We have trained, hired and rewarded people to be cowboys. But it’s pit crews that we need, pit crews for patients. Section 11 7:22 There’s evidence all around us: 40 percent of our coronary artery disease patients in our communities receive incomplete or inappropriate care. 60 percent of our asthma and stroke patients receive incomplete or inappropriate care. Two million people come into hospitals and pick up an infection they didn’t have because someone failed to follow the basic practices of hygiene. Our experience as people who get sick, need help from other people, is that we have amazing clinicians that we can turn to--hardworking, incredibly well-trained and very smart--that we have access to incredible technologies that give us great hope, but little sense that it consistently all comes together for you from start to finish in a successful way. Section 12 8:26 There’s another sign that we need pit crews, and that’s the unmanageable cost of our care. Now we in medicine, I think, are baffled by this question of cost. We want to say, “This is just the way it is. This is just what medicine requires.” When you go from a world where you treated arthritis with aspirin, that mostly didn’t do the job, to one where, if it gets bad enough, we can do a hip replacement, a knee replacement that gives you years, maybe decades, without disability, a dramatic change, well is it any surprise that that $40,000 hip replacement replacing the 10-cent aspirin is more expensive? It’s just the way it is. Section 13 9:17 But I think we’re ignoring certain facts that tell us something about what we can do. As we’ve looked at the data about the results that have come as the complexity has increased, we found that the most expensive care

3

is not necessarily the best care. And vice versa, the best care often turns out to be the least expensive--has fewer complications, the people get more efficient at what they do. And what that means is there’s hope. Because if to have the best results, you really needed the most expensive care in the country, or in the world, well then we really would be talking about rationing who we’re going to cut off from Medicare. That would be really our only choice. Section 14 10:15 But when we look at the positive deviants--the ones who are getting the best results at the lowest costs--we find the ones that look the most like systems are the most successful. That is to say, they found ways to get all of the different pieces, all of the different components, to come together into a whole. Having great components is not enough, and yet we’ve been obsessed in medicine with components. We want the best drugs, the best technologies, the best specialists, but we don’t think too much about how it all comes together. It’s a terrible design strategy actually. Section 15 10:59 There’s a famous thought experiment that touches exactly on this that said, what if you built a car from the very best car parts? Well it would lead you to put in Porsche brakes, a Ferrari engine, a Volvo body, a BMW chassis. And you put it all together and what do you get? A very expensive pile of junk that does not go anywhere. And that is what medicine can feel like sometimes. It’s not a system. Section 16 11:32 Now in a system, however, when things start to come together, you realize it has certain skills for acting and looking that way. Skill number one is the ability to recognize success and the ability to recognize failure. When you are a specialist, you can’t see the end result very well. You have to become really interested in data, unsexy as that sounds. Section 17 12:00 One of my colleagues is a surgeon in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and he got interested in the question of, well how many CT scans did they do for their community in Cedar Rapids? He got interested in this because there had been government reports, newspaper reports, journal articles saying that there had been too many CT scans done. He didn’t see it in his own patients. And so he asked the question, “How many did we do?” and he wanted to get the data. It took him three months. No one had asked this question in his community before. And what he found was that, for the 300,000 people in their community, in the previous year they had done 52,000 CT scans. They had found a problem. Section 18 12:47 Which brings us to skill number two a system has. Skill one, find where your failures are. Skill two is devise solutions. I got interested in this when the World Health Organization came to my team asking if we could help with a project to reduce deaths in surgery. The volume of surgery had spread around the world, but the safety of surgery had not. Now our usual tactics for tackling problems like these are to do more training, give people more specialization or bring in more technology. Section 19 13:26 Well in surgery, you couldn’t have people who are more specialized and you couldn’t have people who are better trained. And yet we see unconscionable levels of death and disability that could be avoided. And so we looked at what other high-risk industries do. We looked at skyscraper construction, we looked at the aviation world, and we found that they have technology, they have training, and then they have one other thing: They have checklists. I did not expect to be spending a significant part of my time as a Harvard surgeon worrying about checklists. And yet, what we found were that these were tools to help make experts better. We got the lead safety engineer for Boeing to help us. Section 20 14:19 Could we design a checklist for surgery? Not for the lowest people on the totem pole, but for the folks who were all the way around the chain, the entire team including the surgeons. And what they taught us was that designing a checklist to help people handle complexity actually involves more difficulty than I had

4

understood. You have to think about things like pause points. You need to identify the moments in a process when you can actually catch a problem before it’s a danger and do something about it. You have to identify that this is a before-takeoff checklist. And then you need to focus on the killer items. An aviation checklist, like this one for a single-engine plane, isn’t a recipe for how to fly a plane, it’s a reminder of the key things that get forgotten or missed if they’re not checked. Section 21 15:11 So we did this. We created a 19-item, two-minute checklist for surgical teams. We had the pause points immediately before anesthesia is given, immediately before the knife hits the skin, immediately before the patient leaves the room. And we had a mix of dumb stuff in there--making sure an antibiotic is given in the right time frame because that cuts the infection rate by half--and then interesting stuff, because you can’t make a recipe for something as complicated as surgery. Instead, you can make a recipe for how to have a team that’s prepared for the unexpected. And we had items like making sure everyone in the room had introduced themselves by name at the start of the day, because you get half a dozen people or more who are sometimes coming together as a team for the very first time that day that you’re coming in. Section 22 16:01 We implemented this checklist in eight hospitals around the world, deliberately in places from rural Tanzania to the University of Washington in Seattle. We found that after they adopted it the complication rates fell 35 percent. It fell in every hospital it went into. The death rates fell 47 percent. This was bigger than a drug. Section 23 16:34 And that brings us to skill number three, the ability to implement this, to get colleagues across the entire chain to actually do these things. And it’s been slow to spread. This is not yet our norm in surgery--let alone making checklists to go onto childbirth and other areas. There’s a deep resistance because using these tools forces us to confront that we’re not a system, forces us to behave with a different set of values. Just using a checklist requires you to embrace different values from the ones we’ve had, like humility, discipline, teamwork. This is the opposite of what we were built on: independence, self-sufficiency, autonomy. Section 24 17:31 I met an actual cowboy, / by the way. / I asked him, / what was it like / to actually herd / a thousand cattle / across hundreds of miles? / How did you do that? / And he said, / “We have the cowboys / stationed at distinct places all around.” / They communicate electronically constantly, / and they have protocols / and checklists / for how they handle everything / --from bad weather / to emergencies / or inoculations for the cattle. / Even the cowboys / are pit crews now. / And it seemed like time / that we become / that way ourselves. Section 25 18:08 Making systems work is the great task of my generation of physicians and scientists. But I would go further and say that making systems work, whether in health care, education, climate change, making a pathway out of poverty, is the great task of our generation as a whole. In every field, knowledge has exploded, but it has brought complexity, it has brought specialization. And we’ve come to a place where we have no choice but to recognize, as individualistic as we want to be, complexity requires group success. We all need to be pit crews now.

5

6

NOTES Section 3 0:58 deepest crisis, every country: of cost of health care why? government, insurance companies? something else, deeper problem Section 4 1:43 cause: complexity Boston City Hospital,1937 medicine cheap, but ineffective hospital: warm, food, care, nurse, few cures Section 5 2:52 a few curable diseases: lobar pneumonia (antiserum), acute congestive heart failure (digitalis), syphilis (toxic mercury and arsenic) Section 6 4:04 core structure of medicine created early 20th century doctors could know all, do all: set fracture, draw blood, spin blood, use microscope… Section 7 4:46 doctor’s values: courageous, independent, self-sufficient, autonomous now: treatments for 10s of thousands of conditions Section 8 5:33 now: 4,000 medical and surgical procedures, 6,000 drugs, for every person alive doctors can’t know it all, can’t do it all by themselves Section 9 6:11 1970: two full-time equivalents of clinicians/case end of the 20th century: 15 clinicians--specialists, physical therapists, nurses Section 10 6:50 doctors all specialists now everyone just one role still trying to be daring, independent, self-sufficient not cowboys—we need pit crews (cooperation, teamwork, systems) Section 11 7:22 40% coronary artery disease patients: incomplete or inappropriate care 60 % asthma and stroke patients: incomplete or inappropriate care 2 million people get infections in hospitals clinicians hardworking, well-trained, smart, great technologies pieces don’t come together from start to finish Section 12 8:26 pit crews needed to manage cost of course: aspirin cheap, technology expensive Section 13 9:17 most expensive care not necessarily best care least expensive care—often has fewer complications need to control costs or begin rationing

7

Section 14 10:15 cases with best results at the lowest costs = systems different components come together need to think more about how it all comes together Section 15 10:59 Section 16 11:32 evaluation necessary: recognize success, recognize failure specialist can’t see the end results look at data Section 17 12:00 300,000 people in one community got 52,000 CT scans/year problem unnoticed for a long time Section 18 12:47 find where failures happen devise solutions World Health Organization challenge: reduce deaths and complications from surgery usual solution: more specialization, more technology Section 19 13:26 studied other high-risk industries: skyscraper construction, aviation they use checklists! Section 20 14:19 designed checklist for surgery pause points: catch a problem before it’s a danger checklist = reminder, key things forgotten or missed if not checked Section 21 15:11 created a 19-item, two-minute checklist for surgical teams pause points: before anesthesia, before the knife hits the skin, before the patient leaves the room Section 22 16:01 8 hospitals around the world, different kinds of countries checklist use → complication rates down 35 %, every hospital death rates fell 47 percent more effective than a new drug or technology Section 23 16:34 final skill: ability to implement, get colleagues to do it change slow to spread doctors slow to change, deep resistance, conservative still want to be cowboys: independence, self-sufficiency, autonomy. new values needed: humility, discipline, teamwork Section 24 17:31 ironic ending: real cowboys are pit crews now, use cell phones, checklists Section 25 18:08 systems needed in other fields too: education, climate change, reducing poverty complexity and specialization in all fields complexity requires group success

8

In this lecture, Dr. Gawande talked about...

A. Introduction

The problem: increasing complexity = high cost. Cost not about the debate between:

1. socialism (socialized medical care) and 2. capitalism (private insurance companies, individuals paying for their own medical)

Both socialist and capitalist solutions have to deal with increasing complexity and costs. If we can’t manage complexity, we will have to ration health care—which means denying care to some people.

B. How medical practice has changed

THEN NOW knowledge limited, could be known by one person unlimited, impossible for one person to

know all of it drugs limited number, use could be learned

by one person thousands, too many for one person to learn how to use

diagnostics limited knowledge, one person could master diagnostic skills

too complex, too much for one person to learn

treatments few, not very effective, one person could learn all of them

many, very complex, too many for one person to learn all of them

hospital a place to rest, assisted natural recovery, receive some effective treatments

a place to be cured, many effective treatments

no. of clinicians few many

values autonomy, authority: cowboy teamwork, humility, systems: pit crew

C Conclusions

Solutions:

teamwork, pit crews, use data, analyze the big picture, look at the system example: study the use of CT scans in a small city example: checklists, borrow ideas from other professions, no extra training needed, inexpensive but effective Problems: Medical practitioners resist change The medical profession is a hierarchy but teamwork involves equality People like autonomy

9

DICTATION Section 24 17:31

I met (1)_______________ _______________ _______________, by the way. I asked him,

(2)_______________ _______________ _______________ _______________ to actually herd a thousand

cattle (3)_______________ _______________ _______________ _______________? How did you do

that? And he said, “We have the cowboys stationed at (4)_______________ _______________

_______________ _______________.” They communicate electronically constantly, and they

(5)_______________ _______________ _______________ _______________ for how they handle

everything--from (6)_______________ _______________ _______________ _______________ or

inoculations for the cattle. Even the cowboys are pit crews now. And it seemed like time that

(7)_______________ _______________ _______________ _______________ ourselves.

DICTATION Section 24 17:31

I met (1)_______________ _______________ _______________, by the way. I asked him,

(2)_______________ _______________ _______________ _______________ to actually herd a thousand

cattle (3)_______________ _______________ _______________ _______________? How did you do

that? And he said, “We have the cowboys stationed at (4)_______________ _______________

_______________ _______________.” They communicate electronically constantly, and they

(5)_______________ _______________ _______________ _______________ for how they handle

everything--from (6)_______________ _______________ _______________ _______________ or

inoculations for the cattle. Even the cowboys are pit crews now. And it seemed like time that

(7)_______________ _______________ _______________ _______________ ourselves.

10

Section 24 17:31

I met an actual cowboy, by the way. I asked him, what was it like to actually herd a thousand cattle across

hundreds of miles? How did you do that? And he said, “We have the cowboys stationed at distinct places all

around.” They communicate electronically constantly, and they have protocols and checklists for how they

handle everything--from bad weather to emergencies or inoculations for the cattle. Even the cowboys are pit

crews now. And it seemed like time that we become that way ourselves.

11

Do statistics tell you the whole picture? Consider this hypothetical situation: If the researcher claims that using checklists led to a 50% decline in the rate of death after surgery, what is the significance of this result? Is the significance the same in every hospital?

Hospital rate of death after surgery before checklists

rate of death after surgery after checklists

change in %

1 200/1000 100/1000 50% 2 50/1000 25/1000 50% 3 6/1000 3/1000 50% 4 2/1000 1/1000 50% 5 40/1000 20/1000 50% 6 300/1000 150/1000 50% 7 20/1000 10/1000 50% 8 42/1000 21/1000 50%

Perhaps training and technical skill are more important in the places where the use of checklists led to the greatest decrease in number of deaths. In some places, the raw number change was not significant. Are the statistics significant in the case of Hospital 3 and 4? In the case of Hospital 1 and 6, the number of lives saved was very significant. Perhaps the use of the checklist forced the hospital staff to see some weak points in their skills and services. In these cases, the checklist was not just reminding them of what they needed to do. It was teaching them what they needed to do. In the case of Hospital 3 and 4 the change was small and perhaps insignificant. The checklist may not be the reason for the improvement in the rate. It could be just a random change. In conclusion, when Dr. Gawande says “the complication rates fell 35 percent” and “death rates fell 47 percent” we need to look more closely at these statistics and consider whether his claim of a causal connection is correct. He might be correct, but there might be other factors hidden in the statistics.

12

Atul Gawande: How do we heal medicine? Japanese translation by Keiichi Kudo, reviewed by YUTAKA KOMATSU. 随筆を書いたり 研究を始めた頃 随筆を書いたり 研究を始めた頃 私は外科研修医で 何をやるにおいても

その道のプロと呼ぶには ほど遠い存在でした そこで知りたかったのは どうしたら 良い医者になれるの

か? 後にそれが どうしたら皆で 良い治療ができるか? という疑問に繋がりました 技術を身につけるだ

けでも 困難なのに 膨大な知識を 吸収しなくてはいけません あらゆるタスクに おいてです 縫合や切開

の仕方を 考えるだけでなく どんな患者に 手術を行うかも 決めなくてはいけません そんなことを 考え

ていたとき 「良い」とは何かを 考えさせられる 新しい状況が 訪れました ここ数年 医療が危機に さら

されていることが 明らかになってきました 患者のために 何が良いかを 第一に考える医者が 見落としが

ちなもの— 医療費の問題です 医療費の問題です 世界中のどこにも 医療費で 悩んでいない国など あり

ません 政治論争では この問題が 政府の問題か 保険会社の問題なのかで 揉めています 答えはイエスで

もあり ノーでもあり もっと深い次元の 問題なのです 実はその原因は 科学によってもたらされた 複雑

さにあります これを理解するために 数世代前を 考えてみましょう ルイス・トマスが 『医学は何ができ

るか』を 書いた時代まで遡ります 彼は医師であると同時に 作家で 私の好きな作家の1人です 彼は著書

の中で ボストン市立病院の インターン医師としての 経験を語っています ペニシリン普及以前の 1937

年のことです まだ薬が安く たいした効果も なかった時代です 彼によると 当時の入院のメリットは 暖

かい部屋と食事 寝る場所 そして 看護婦に気遣ってもらえる ことくらいでした 看護婦に気遣ってもらえ

る ことくらいでした 医者や薬に出来ることは 限られていたのです そんな状態でも 医者は相変わらず

忙しく立ち働いていたと 書かれてあります 医者の仕事は 患者を診て 治療できる病気かどうか 診断する

ことでした 治療できるものも いくつかはありました 例えば 大葉性肺炎の患者には 血清を投与できまし

たし 連鎖状球菌感染症の 患者には ウサギの抗体を 注射できました インターンが菌を正しく 分類でき

ればの話ですが 急性うっ血性 心不全の 患者なら 腕の血管から 血液を 500ml ほど抜き シギタリスの葉

を投与し テントで酸素供給をします 麻痺の前兆が見られ プライベートな質問が 上手にできたとしたら

麻痺の原因が 梅毒だと わかるかもしれません その場合 水銀とヒ素の 混合薬で治療できます やり過ぎ

て 死なせなければですが この種の治療以外では 医者に出来ることは そんなにありませんでした 医療の

基礎が できあがったのは この頃です 良い医療とは何か 医療のあり方が 定義されたのです その頃はま

だ 存在する知識を 全て知り 全てを記憶し 1人で何でもできる時代でした 薬が処方できて 看護師がいて

患者を回復させられる病院や 基本的な器具さえあれば 医者が自分で 何でもできたのです 骨折の処置を

し 採血し 血液を遠心分離機にかけ 顕微鏡で見ることが できました 細菌培養をし 血清を注射し— 医者

は職人だったのです その結果 築き上げられた 文化と価値観は 良い医者とは 度胸があり 勇敢で 1人で

何でも出来る ということでした 自立性が最も 重要だったのです しかし数世代が経って 現在の我々の時

代は すっかり様変わりした ように見えます 何万もある 人間の病気に対する 何万もある 人間の病気に

対する 治療法がわかっています 全てを治癒できる わけではないし 健康長寿を 全人類に保証もできませ

んが それに近いことが 可能になりつつあります それに近いことが 可能になりつつあります でも それ

13

には 何が必要でしょう? 現在4千もの 内科的・外科的 治療法が存在し 認可されている薬は 6千もあ

ります これだけのものを 1つ1つの町の 1人1人に 届けようとしています 自国はもちろん 世界中に

もです また 医療の面でも ついに 医者として 全ての知識を身につけ 全ての処置を 自分で行うことは 無

理な段階に達したのです 入院患者 1人を世話するのに 何名の医療関係者が必要かを 年代別に 調べた研

究があります 1970 年には フルタイムの医療関係者 2人分の仕事量でした とは言っても それは ほとん

どが看護の時間で 通常1日に1度の 医師の回診の時間を 通常1日に1度の 医師の回診の時間を 少し足

したものでした 二十世紀終わりには 同様のごく一般的患者に 15名以上の 医療関係者が 対応するよう

になりました 複数の専門医や 理学療法士 看護師たちです 今や 我々皆が 専門分野を持っていて 家庭医

ですら 専門医と言えます 誰もが治療全体の 一部だけを 受け持っているのです その現状で 大胆で 1人

で何でもできる人材を基に 大胆で 1人で何でもできる人材を基に 構成された医療制度は 機能しなくな

っているわけです 我々は一匹狼の カウボーイのような人材を 育て 雇い 賞賛してきました しかし現在

必要とされているのは 患者のための ピットクルーです その証拠は あちこちにあります 我々の社会にお

ける 冠状動脈疾患の 患者の 40% は 不完全あるいは 不適切な治療を受けています 喘息患者や 脳卒中患

者の 60% が 不完全あるいは 不適切な治療を受けています 2百万人もの患者が 元々持っていなかった病

気に 病院で感染しています 誰かが基本的な 感染予防策を 実行しなかったからです 実際の所 病気にな

り 助けが必要になれば 素晴らしい医者を 頼りにすることが出来ます 献身的で 素晴らしい教育を受けた

頭脳明晰な人々です 目を見張るような テクノロジーにも 大いに期待できます でもこれらのものが 治療

のそれぞれのステップで 必要に応じ 上手くまとまり 使われているとは とても思えません ピットクルー

が 必要だという 兆候は他にもあります それは我々の手に余る 医療費です 我々医療関係者からすると

医療費問題には 当惑させられます 「これが現実なんだ」「必要なコストなんだ」と 言いたくなります

「これが現実なんだ」「必要なコストなんだ」と 言いたくなります 時代が変わり 関節炎には大して効

果もない アスピリンを 処方していたのが 今や酷いケースには 股関節・膝関節 置換を施し 数年から数

十年の 不自由のない 生活を与えられるように なりました 劇的な変化です 10 セントのアスピリンより

4万ドルの股関節置換の方が 高価だというのは 驚くことでもない そういうものなのだと でも医療の側

ができる事を 示唆するデータもあるのです 複雑さが増した結果 複雑さが増した結果 何が起きたかデー

タを見て 分かったことは 何が起きたかデータを見て 分かったことは 最も高価な治療法が 最も良い治療

法だとは 限らないということです 逆に 最も良い治療法が 最も安価なもの 合併症の少ない 上手くこな

しやすいもの であったりします つまり 望みはあるわけです もし 最良の結果を 得るためには 国内 ある

いは世界中で 最も高価な治療法が 必要だとしたら 誰を国の医療保険から 振るい落とすか 議論していか

なければ ならないでしょう 他に手はありません しかし「良い逸脱」に目を向け 最も安価で 最高の結果

を出している 治療法を調べてみると— 最もシステム化されたものが 最も成功しているのです つまりそ

こでは 別々の要素 別々の部品を 上手くまとめる方法を 見つけているということです 優れた部品がある

だけでは 不十分なのに 医療に関して我々は 部品にこだわってきました 最高の薬 最高のテクノロジー

最高の専門医を 求めてきました しかしそれらが どう統合されるかは あまり考えて きませんでした お

14

粗末な設計戦略です 有名な思考実験に まさに これを 扱ったものがあります 「最高の部品だけ集めて一

台の車を 組み立てたらどうなるか?」 「最高の部品だけ集めて一台の車を 組み立てたらどうなる

か?」 ブレーキはポルシェ エンジンはフェラーリ 車体はボルボで シャーシは BMW これらを集めて組

み立てたら 何ができるでしょう? 動きもしない 高価なガラクタです これが時に 医療現場で感じること

です システムになっていないのです そのシステムなんですが システムが 上手く働き出すと システムと

して 振る舞うための 特定の能力があることに 気付きます 能力その1は 「成功を認識する能力と 問題

を認識する能力」です 「成功を認識する能力と 問題を認識する能力」です 専門医は 最終的な結果を う

まく予想できません データにとても深い関心を 持つ必要があります 地味な仕事ですね アイオワ州の シ

ーダーラピッズ市で 外科医をしている同僚が 市内で CT スキャンが どれほど 行われているのか 興味を

持ちました その理由は 政府の報告書や 新聞・雑誌記事に CT スキャンが 過度に実施されていると 書か

れていたからです 彼自身の患者には あてはまらないので 「ここではどうなんだろう?」と思い データ

を集めることにしました それには3ヶ月かかりました これを調べた人は いなかったのです データから

分かったのは 地域住民 30 万人に対して 前年に 5万2千回もの CT スキャンが 行われていました 問題

があったわけです そこでシステムが持つ 2番目の能力に移ります 能力その1は 「問題を見つける」で

した 能力その2は 「解決策を作る」です 私がこれに興味を持ったのは 世界保健機関が 私のチームを訪

ね 手術での死亡率を減らす プロジェクトへの 協力を求められた時です 外科手術は 数の上では 世界に

増え広まって いましたが その安全性は 広まっていませんでした 通常 このような 問題の解決には 訓練

時間を増やしたり 人をより専門化させたり テクノロジーを 取り入れたりします しかし 外科医は 皆す

でに専門化しており 十分な訓練を受けています にもかかわらず 異常な水準で 避けられたはずの 死亡や

障害が 発生しています そこで他の ハイリスクな業界に 目を向けました 高層ビル建設や 航空業界を調

べて 我々が発見したのは テクノロジーや訓練の他に もう1つ 使われているものが あることでした チ

ェックリストです ハーバードの 外科医である私が 多くの時間を費やして チェックリストなどに 頭を悩

ませることになろうとは 思いもしませんでしたね しかし我々が発見したのは それが専門家の能力を 更

に引き出す ツールだということです 我々はボーイングの 安全対策エンジニアに 手術用のチェックリス

トは作れるか 聞きました 専門性の低い作業者用 ではありません 外科医を含む チーム全員が使える 外

科医を含む チーム全員が使える チェックリストです 我々が学んだのは 複雑さに対処するための チェッ

クリストを作ることは 考えていたより 難しいということです 皆が立ち止まって リストを確認する タイ

ミングを考える 必要があります 危険が発生する前に 問題を察知し対処すべき タイミングを 見つけ出さ

なければ なりません このチェックリストは 離陸前チェックリストに 相当するものなのです 次に危険因

子に注目します 飛行のチェックリストとは— これは単発機用のものですが 飛行の仕方の 手順ではあり

ません チェックをしないと 忘れられたり見逃される チェックをしないと 忘れられたり見逃される 重要

項目の 備忘録なのです 我々はこれを作りました 手術チーム向けの 19 項目からなる 2分でできる チェ

ックリストです 手を止めて 確認するタイミングは 麻酔開始の直前 皮膚を切開する直前 患者が手術室を

出る直前です 当然あってしかるべき 項目もあれば— 抗生物質の適時投与の 項目などがそうですが これ

15

で感染率が 半分に下がります 一方で変わった項目もあります 手術ほど複雑なものに 決まった手順は作

れませんが チームが想定外のことに 備えるための 手順は作れます 例えば手術室にいる 全員の名前を

手術開始時に紹介し合う 項目を作りました なぜなら 何人ものメンバーが その日初めてチームとして 参

加するという事も あるからです 我々はこのチェックリストを 世界中の8つの病院で 導入しました 意図

して広く タンザニアの田舎から シアトルのワシントン大学まで 選びました 導入後の調査では 合併症発

生率が 35% 下がりました 導入した全ての病院でです 死亡率は 47% 下がりました 投薬より大きい成果で

す (拍手) ここで大切なのが 能力その3です 「実践する能力」です 関係者全員に このチェックリストを

実践してもらうことです でも普及には 時間がかかっており まだ手術時の標準には なっていませんし 分

娩室や他の分野の チェックリストもできていません 強い抵抗があるのです なぜなら こういった ツール

を使うことは 我々がシステムではないことを 直視させ 異なる価値観での行動を 強いるからです 単にチ

ェックリストを 使うことが 新しい価値観の 受け入れを求めるのです 例えば 謙虚さ 規律 チームワーク

などです 我々が育てられたものとは 逆のものです 独立性 自己完結性 自主性などです ところで本物の

カウボーイに 会う機会があって 千頭もの牛を連れ 何百キロもの距離を 移動させるのは どんなものなの

か 尋ねてみました どうしたら そんなことができるのか? 「あちこちにカウボーイを 配置しているん

だ」と彼は答えました 彼らは電子通信で 常に連絡を取り合うし 対応事項全ての 約束事や チェックリス

トがあるんです— (笑) 悪天候から 緊急事態や家畜の予防接種まで 全てにです カウボーイですら 今やピ

ットクルーなんです 私達 医者にも いよいよ そうなる時が 来たようです システムを上手く 働かせるの

は 我々の世代の 医師や科学者の 重大な仕事です 更に こうも感じます 医療 教育 気候の変化 貧困の根絶

などの 問題に当たる システムを上手く 働かせるのは 我々の世代が 一丸となって 携わる必要のある 重

大な仕事なのだと あらゆる分野で 知識が激増しました その結果 複雑さや 専門化がもたらされました

我々はこの問題を認識し 対応していかなくては なりません 人間 ユニークで ありたいものですが 世の

複雑さに 対応するためには 集団としての成功が 大切です 我々は今 皆が ピットクルーになる必要があ

るのです ありがとうございました .