Hope and Heresy

Transcript of Hope and Heresy

Hope and Heresy

Leigh T.I. Penman

Hope and HeresyThe Problem of Chiliasm in Lutheran Confessional Culture, 1570–1630

ISBN 978-94-024-1699-2 ISBN 978-94-024-1701-2 (eBook)https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1701-2

© Springer Nature B.V. 2019This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed.The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.The publisher, the authors, and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This Springer imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature B.V.The registered company address is: Van Godewijckstraat 30, 3311 GX Dordrecht, The Netherlands

Leigh T.I. PenmanInstitute for Advanced Studies in the HumanitiesUniversity of QueenslandSt. Lucia, QLD, Australia

For dido

vii

Acknowledgements

The present work concerns the problematic status of optimistic apocalyptic expec-tations in early modern Lutheran confessional culture. It began life many years ago in a very different form as a doctoral dissertation at the University of Melbourne under the supervision of Charles Zika. It was in Charles’s courses as an undergradu-ate that I first encountered the works of Robin Bruce Barnes, Johannes Wallmann and Carlos Gilly, whose research influenced the development of my own interests. During the research for this book, I was fortunate to spend time at the Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel on multiple occasions, firstly as a guest researcher under the auspices of the Dr. Günther Findel Stiftung and, secondly, with a fellowship from the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD). In Wolfenbüttel, I profited from the advice and friendship of numerous scholars whose thoughts helped to shape this work, including Jill Bepler, Jürgen Beyer, Andreas Corcoran, Warren Dym, Robert Hardwick Weston, Gizella Hoffmann, Grantley McDonald, Alexander Nebrig, Cornelia Niekus-Moore, Beth Plummer, Theo Pronk, Jenny Spinks and Douglas Shantz, as well as the fellow members and co-founders of SAV Wolfenbüttel, especially Ilona Fekete and Márton Szentpéteri. During the term of my DAAD grant, both Manfred Jakubowski-Tiessen and Hartmut Lehmann gave me of their time at the former Max-Planck-Institut für Geschichte in Göttingen, and I am grateful for their advice and interest.

It was not until a postdoctoral fellowship with the Cultures of Knowledge project at the University of Oxford, however, that this book began to take its present shape. This was largely due to the influence of Howard Hotson, as well as the convivial discussions I had concerning matters apocalyptic with Brandon Marriott, Vladimír Urbánek and James Brown. More recently, a fellowship with the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities (formerly the Centre for European Discourses) at the University of Queensland allowed the time for the work to further mature in an ideal intellectual environment, where I benefitted from the wisdom of Philipp Almond, Peter Harrison and Ian Hesketh during the completion of the manuscript. At a late stage, Howard Hotson read and critiqued several key chapters, improving them immensely by asking the hardest of questions. I am grateful as well to the two anonymous readers provided by the publisher; their reports were instrumental in

viii

shifting slightly the tone and focus of the analysis and adding further layers of complexity.

I would like to collectively thank the staff of archives and libraries throughout Australia, Europe and North America, especially in Wolfenbüttel, Erfurt, London, Strasbourg, Wrocław, Prague, Copenhagen, Dresden, Görlitz, Rudolstadt, Steyr, Budapest, Amsterdam, Karlsruhe, Tübingen, Nuremberg, Munich, Vienna and Zittau, all of whom fielded requests for manuscripts, books, reproductions and information helpfully and efficiently and whose own initiative led to the discovery of many new sources which would otherwise have remained unknown to me. Finally, I would like to thank my family, my parents, my brother and my late grand-mother, whose patience, love and support have always been exemplary. To Ilona, Samu and Kata, thanks for making every day amazing. This work is dedicated to the memory of Walter Berezy (1924–2016), a pansophist in the tradition of Comenius who, had he lived in an age not ruined by war and its consequences, might well have written something like it.

Acknowledgements

ix

Introduction

In 1621, Valentin Grießmann (d. 1639), Lutheran pastor in Wählitz near Magdeburg, penned a book against a ‘sudden and inexplicable’ rash of heretical publications that had caused him great concern. Over the last few years, Grießmann had seen more than 100 printed pamphlets, together with many more manuscript works circulating among the local populace, which convinced him that a ‘seditious conspiracy against all good order’ was afoot in the Holy Roman Empire.1 Grießmann believed that these tracts were authored by a ‘secretly confederated and corresponding mob’ (heimliche confoederirte vnd correspondirente Rotte)2 of Weigelians, Rosicrucians, Paracelsians, visionaries, new prophets and theosophers. This ‘mob’ was responsi-ble for ‘fanning the flames of war’ and accelerating the descent of the Empire into chaos and destruction. Additionally, these works betrayed all manner of heresies, ranging from Christological errors to misrepresentations of the nature of the Holy Spirit. Yet there was one heretical doctrine which, Grießmann held, was common to all these books; they anticipated that there would soon occur a golden Reformation (güldene Reformation), a time of peace before the Last Judgment.3 As Grießmann argued, this expectation was the result of a grave and pernicious heresy called chiliasmus or chiliasm. But where Grießmann saw heresy, others saw hope.

The present study investigates the place of optimistic apocalyptic expectations—that is to say, visions of an earthly future felicity before the Last Judgment—within German Lutheranism between approximately 1570 and 1630. This time span is deliberately chosen. Its starting point encompasses the time of the expansion of Lutheran eschatological expectations following Luther’s death and the supernova of

1 Valentin Grießmann, Πρόδρομος εὐμενὴς, καὶ ἀποτρεπτικός Exhibens enneadem quaestionum generalium De Haeresibus ex orco redivivis: Das ist: Getrewer Eckhart/Welcher in den ersten Neun gemeinen Fragen/der Wiedertäufferischen/Stenckfeldischen/Weigelianischen/und Calvino-Photinianischen/Rosen Creutzerischen Ketzereyen/im Landen herumbstreichende und streiffende wüste Heer zu fliehen/und als seelenmörderische Räuberey zu meyden verwarnet. (Gera: Andreas Mamitzsch, 1623), 14.2 Grießmann, Getrewer Eckhart, 48.3 Grießmann, Getrewer Eckhart, 48, 67.

x

1572 and concludes following the aftermath of the many disappointed prophesies that anticipated the commencement of the desired Golden Age sometime during or after the great conjunction of 1623. It incorporates the first 12 years of the Thirty Years’ War and the environmental, political and confessional crises which preceded it. Within lay and clerical cultures, the extensive engagement with ideas of a time of future felicity before the Last Judgment provoked a diverse range of opinions, from approval to approbation.

Within Lutheranism, ideas of a future respite or Golden Age were often consid-ered heretical because they butted up against the pessimistic apocalypticism that was widely held in the faith.4 Many Lutherans believed that the Millennium of Revelation 20:1–6, one of the great inspirations for visions of a future felicity, was a period that had occurred historically. Orthodox Lutherans typically expected that before the Judgment Day, conditions on earth would worsen, until the true church was finally vindicated following the apocalyptic event. Thus, when Luke 18:8 posed the question ‘when the Son of Man cometh, shall he find faith on the earth?’, the typical Lutheran response was ‘very little or none’.5 These expectations were ini-tially encouraged by Martin Luther (1483–1546). Defending a fledgling faith decried as heretical by its Catholic opponents, he promoted a historical interpreta-tion of the apocalyptic books of the New Testament and considered the Last Judgment imminent. As Robin Bruce Barnes has summarized: ‘For Luther, Christ stood poised to return, to deliver his own, and to deal the final blow to a corrupt world. The faithful could rejoice in the recovery of God’s word and the nearness of their salvation. Meanwhile they were called upon to steel themselves against the final ragings of Satan’s powers on earth’.6 Under the influence of the devil, the world had begun to resemble the time of Noah, ripe for a new flood to wipe away

4 On the character of Lutheran eschatology, and more especially apocalypticism, see Hans-Henning Pflanz, Geschichte und Eschatologie bei Martin Luther (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1939); Ulrich Assendorf, Eschatologie bei Luther (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1967); Robin Bruce Barnes, Prophecy and Gnosis: Apocalypticism in the Wake of the Lutheran Reformation (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988); Gerhard May, ‘“Je länger, je ärger?” Das Ziel der Geschichte im Denken Martin Luthers,’ Zeitwende 60 (1989), 208–218; Robin Bruce Barnes, ‘Der herabstürzende Himmel: Kosmos und Apokalypse unter Luthers Erben um 1600,’ in Jahrhundertwenden: Endzeit- und Zukunftsvorstellungen vom 15. bis zum 20. Jahrhundert. Manfred Jakubowski-Tiessen, et al., eds. (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1999), 129–146; Volker Leppin, Antichrist und Jüngster Tag. Das Profil apokalyptischer Flugshriftenpublizistik im deutschen Luthertum 1548–1618. (Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 1999); Matthias Pohlig, Zwischen Gelehrsamkeit und konfessioneller Identitätsstiftung: lutherische Kirchen- und Universalgeschichtsschreibung 1546–1617 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007).5 Censuren und Bedencken Von Theologischen Faculteten und Doctoren Zu Wittenberg/Königsberg/Jehna/Helmstädt Uber M. Hermanni Rahtmanni Predigers zu S. Catharinen binnen Dantzig außgegangenen Büchern. (Jena: Birckner, 1626), 106.6 Barnes, Prophecy and Gnosis, 3. On the development of Luther’s attitudes and interpretations, see further the useful summary by Bernhard Lohse, ‘Eschatologie’ in Luthers Theologie in ihrer his-torischen Entwicklung und in ihrem systematischen Zusammenhang (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1995), 345–355.

Introduction

xi

sin.7 For Luther, any amelioration of society in this apocalyptic last age was impos-sible: ‘Now we see, that after this time in which the Pope has been revealed [as Antichrist], there is nothing to hope for or to anticipate, than the end of the world’.8

On account of Luther’s historicist apocalypticism, the confession as a whole was largely hesitant to embrace any form of meliorism.9 This pessimistic apocalypticism was enshrined as a dogmatic article of belief in the Confessio Augustana (1530), the earliest systematic creed of the Lutheran faith. Article 17 specifically forbade the expectation that ‘there will be an end to the punishments of condemned men and devils’, in addition to the idea that ‘before the resurrection of the dead the godly shall take possession of the kingdom of the world, the ungodly being everywhere suppressed’.10 Many Lutherans interpreted these statements—which had their ori-gins in very specific social and doctrinal circumstances—as forbidding any expecta-tion of a worldly felicitous future. To them, like Luther before them, there was nothing left for the faithful to do but await the Last Judgment. The postulation of a period of future felicity, no matter how short its duration, threatened to upset these expectations.

Nevertheless, by around 1600, a vocal cadre of individuals raised within Lutheran confessional culture was prepared to embrace a spectrum of optimistic expectations concerning the Last Days. These expectations were promulgated in a variety of ways: in scribal publications, preaching on the streets and through the printing press. They called it by various names: the Millennium, the Golden Age, a New Reformation, the Age of the Holy Spirit or the Time of Lilies. For some, this felici-tous period would be terrestrial in nature; for others, it would be purely spiritual, taking place in the heart of the true believer. Some would base their expectations on scripture, finding inspiration in Revelation 20, Daniel 12, the apocryphal 2 Esdras or the synoptic apocalypse of Matthew 24–25. Others would find their authority in medieval prophecies, or in works of more contemporary figures—like Paracelsus or visionary prophets—who claimed to be inspired by the Holy Spirit directly. Still others claimed to base their expectations on their observations of God’s other cre-ations, such as the celestial firmament. The duration of this future time was simi-

7 Hermann Rahtmann, Christlicher Tugentspiegel, in welchem ihre Art und Eygenschafften zur Gottseligen ubung, nach Gottes Wort furgestellt und erkläret werden (Danzig: Hünefeldt, 1620), 128–129; P.E.N.H. [Paul Egard] Heller/Klarer/Spiegel der Jetzigen Zeit/deß Jetzigen Christenthumbs/Glaubens/Lebens/und Wesens im Newen Testament so mit dem Judenthumb/im Alten Testament/gar richtig ubereinstimmet. (No Place: No Printer, 1623); Georg Rost, Ninivitisch Deutschland/Welchem der Prophet Jonas Schwerdt/Hunger/Pestilentz/und den endlichen Untergang ankündiget (Lübeck: Hallevoord, 1624).8 Martin Luther, Werke: Kritische Gesamtausgabe. Deutsche Bibel. 121 vols. (Weimar and Graz: Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger, 1883–2009), vol. 11, part 2, 113; Melchior Ambach, Vom Ende der Welt und zukunfft des Endtchrists. Wie es vorm Jüngsten tag in der Welt ergehn werde. (No Place: No Printer, [c.1550]).9 Pohlig, Zwischen Gelehrsamkeit und konfessioneller Identitätsstiftung; Barnes, Prophecy and Gnosis.10 Die Bekenntnisschriften der evangelisch-Lutherischen Kirche. 9th ed. (Göttingen: Vandenhoek & Ruprecht, 1982), 72.

Introduction

xii

larly contested. Some envisioned it lasting a few decades, others only several years and still others mere months. Most announced that the longed-for felicitous period would dawn in the wake of the great conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in 1623. As might be expected, the literature concerning these optimistic expectations did not go unnoticed by defenders of Lutheran doctrine, who attempted to refute the anticipa-tions of a future felicity and condemn them as heretical. Yet there nevertheless remained Lutherans, among them some clerics, who declared that a Golden Age would soon dawn.

Where did this optimistic apocalypticism come from? How was it justified by its proponents? What are the implications of the debates concerning these expectations for our understanding of Lutheran confessional culture? These are the concerns of the present work, which engages with the writings of Lutheran proponents and opponents of the idea that a period of felicity, however conceived, would precede the Last Judgment. As Robin Barnes first pointed out long ago, optimistic expecta-tions were expressed within lay and clerical culture alike as Lutherans threw them-selves into a search for their own insights into an apocalypse that seemed to recede with the horizon.11 The boundaries between orthodoxy and heresy shifted constantly as new insights were sought and defenders of the faith saw new excesses that had to be curbed. Hope and Heresy documents this process of ongoing negotiation, provid-ing insight into the unstable and at times chaotic disputes that shaped the boundaries of confessional identity. What emerges from this study is that the Lutheran doctrinal position on chiliastic heresy was never uniform. Optimistic apocalyptic expecta-tions had always played a role in the faith. The history of these expectations became entwined with heresy because, as Barnes has argued, what was at stake in these visions was ultimately the issue of authority.12 Barnes’s argument chimes with the incisive observation of the sociologist John R. Hall that ‘the apocalyptic’ is always centred on ‘cultural disjunctures concerned with “the end of the world” and thereafter’.13 The present work documents a particular kind of disjuncture within Lutheran confessional culture. Despite its focus on a particular religious tradition, the debates concerning chiliasm documented in this study have affected the charac-ter of Protestant eschatology and thus European culture more broadly.

Because the present work pursues a diachronic study of apocalyptic ideas in flux, it is important to precisely define the key terms it employs. The most significant of these are Lutheranism and chiliasm. Although each term might appear, at first glance, relatively unproblematic, both have been subject to varying historical, histo-riographical and semantic interpretations.

Chiliasm is an eschatological doctrine, in as much as it relates to the Last Things, but it is more especially an apocalyptic doctrine, for it concerns a particular under-

11 Barnes, Prophecy and Gnosis.12 Barnes, Prophecy and Gnosis. On the significance of contestations of worldly authority as a spur for denunciations of heresy, see the brilliant study of R.I. Moore, The Origins of European Dissent. 2nd ed. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994).13 John R. Hall, Apocalypse. From Antiquity to the Empire of Modernity. (Cambridge and Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2009), 2.

Introduction

xiii

standing of the revelation of world history as standing before a final confrontation between good and evil at the end of time.14 The word ‘chiliasm’ derives from the Greek χίλιοι, meaning thousand. It entered the apocalyptic vocabulary because of the thousand- year period prophesied in Revelation 20:5, in which Satan is cast into the pit and the righteous reign with Christ for 1000 years. Yet its etymology is of relatively limited importance in the context of Lutheran confessional culture of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. For when Lutheran clerics spoke of chiliasts (chiliastae) or used the term chiliasm (chiliasmus), they did so with reference to a heresy that was protean in form. As Chap. 4 of this study documents, before ca. 1574, the word chiliast was by Lutherans to designate an ancient heresy proposed by Church Fathers like Tertullian (160–220 CE) and Papias (70–163 CE), who anticipated that before the Last Judgment, the elect would reign for a literal thou-sand years on earth.15 But after this date, some clerics began to discuss the beliefs of ancient chiliasts in connection with the expectations of more contemporary sects and individuals. In 1614, the Stettin cleric Daniel Cramer (1568–1637) noticed the circulation of a ‘new and subtle chiliastic opinion’ that did not require the expecta-tion of a literal thousand- year time of peace. In 1622, the Jena theologian Johann Gerhard (1582–1637) formally divided the heresy into two categories, chiliasmus crassus and chiliasmus subtilis. The former applied to the ancient heresy, while the latter forbade the anticipation of a future felicity of any duration or nature before the Last Judgment. Given that the rapid expansion of this heresy took place in a polemi-cal religious atmosphere, other, sometimes conflicting, definitions soon followed and circulated simultaneously.

As such, when I use the term chiliasm in this study—and variants like chiliastic and chiliasts—it is with reference to a heresy as understood and defined by Lutherans at that specific time. When describing an expectation of a future felicity before the Last Judgment, of whatever nature, I designate these with phrases like optimistic apocalyptic expectation, expectation of future felicity, Golden Age or similar. These formulations are cumbersome and likely not unproblematic. But they are not intended to be analytical categories. Instead, they are used here to create a vocabu-lary for analysis that does not draw upon the contemporary heresiological terminology.

Because the analytical focus of this work is on the broader intellectual, social and cultural factors that affected debates on chiliasm and optimistic apocalyptic expec-tations within Lutheran confessional culture, the definitions applied in several learned studies on Calvinist millenarianism by Howard Hotson and Jeffrey Jue will not be employed here.16 These definitions—which distinguish between millenarian,

14 Catherine Wessinger, ‘Millennial Glossary,’ in The Oxford Handbook of Millennialism, Catherine Wessinger, ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 717; Stephen D. O’Leary, Arguing the Apocalypse. A Theory of Millennial Rhetoric (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994). On time, evil, and authority see also Hall, Apocalypse, 47, 59–62, 127–130.15 See further the discussion in Chap. 4.16 Howard Hotson, Johann Heinrich Alsted 1588–1638. Between Renaissance, Reformation, and Universal Reform (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 184, note 9; Howard Hotson, Paradise

Introduction

xiv

quasi-millenarian and semi-millenarian strains of expectation—are essential for understanding apocalyptic thought within Calvinism, where there exists a need to differentiate between general pre-1627 meliorism and specific post-1627 literal mil-lenarianism which emerged in the thought of Johann Heinrich Alsted (1588–1638) and Joseph Mede (1586–1639). But the status of optimistic apocalypticism in Lutheran confessional culture differed fundamentally to that within Reformed con-fessional cultures. Within Lutheranism of the early seventeenth century, whether or not any particular anticipation of a felicitous future was based specifically on Revelation 20, was worldly or spiritual or numbered a literal thousand years or not was immaterial to its potential status as chiliastic heresy. Designations used in recent comparative literature on millennialism, such as ‘catastrophic millennial-ism’, ‘progressive millennialism’, ‘avertive apocalypticism’ and ‘nativist millenni-alism,’ among others, have also not been employed in this study, which focusses on these ideas within a single confessional tradition.17

Another term that will be used throughout this work that requires discussion is Lutheranism. Traditionally, in any particular historical period, this term has been employed to designate a body of beliefs and practices based on the doctrines of Martin Luther, defined in the symbolic books of the faith and adhered to by the Lutheran church. But discourse on heresy, orthodoxy and their definition is inher-ently discourse about the contestation of boundaries of faith, doctrine and identity, and these do not always coincide.18 That there were debates about chiliastic heresy within Lutheranism suggests something of the porous nature of the boundaries between heresy and orthodoxy in this period, and therefore of the boundaries of contemporary Lutheranism itself. Orthodox doctrine, belief and practice were stan-dards to which a believer might strive, but certainly not the baseline of life and existence within the culture which grew up around and supported the confessional faith. Furthermore, doctrine was not static. As the present study shows, the defini-tions of chiliastic heresy could expand and contract based on a variety of circumstances.

Postponed. Johann Heinrich Alsted and the Birth of Calvinist Millenarianism (Dordrecht: Kluwer, 2000), 27, note 88; Jeffrey K. Jue, Heaven Upon Earth. Joseph Mede (1586–1638) and the Legacy of Millenarianism (Dordrecht: Springer, 2006). Similarly, I do not employ postmillennial and premillennial in this study, which would also threaten to confuse the terms of the debate. As early as 1980, questions had been raised concerning their explanatory value, a view that has recently intensified. See Ernest R. Sandeen, ‘The ‘Little Tradition’ and the Form of Modern Millenarianism,’ in The Annual Review of the Social Sciences of Religion. Bryan W. Wilson et al., eds. (The Hague: Mouton, 1980), 165–167; Catherine Wessinger, ‘Millennialism With and Without the Mayhem,’ in Millennium, Messiahs, and Mayhem. Contemporary Apocalyptic Movements. Thomas Robbins and Susan J. Palmer, eds. (London and New York: Routledge, 1997), 47–59; Wessinger, ‘Millennial Glossary,’ 721; Robert K. Whalen, ‘Postmillennialism’ in The Encyclopedia of Millennialism and Millennial Movements. Richard Landes, ed. (New York: Routledge, 2000), 326–329; Robert K. Whalen, ‘Premillennialism’ in Landes, ed., Encyclopedia of Millennialism, 329–332.17 On these, see Wessinger, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Millennialism, 27–109; Richard Landes, Heaven on Earth: The Varieties of Millennial Experience (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).18 Volkhard Wels, Manifestationen des Geistes. Frömmigkeit, Spiritualismus und Dichtung in der Frühen Neuzeit (Göttingen: V&R UniPress, 2014), esp. 51–55.

Introduction

xv

Lutheran confessional culture of the early seventeenth century was not homog-enous or monolithic.19 Since 1980, a somewhat different impression has been encouraged in some scholarly literature by the influence of the confessionalization thesis.20 One of the central tenets of the thesis, as postulated by Heinz Schilling, is that through various processes of social discipline, confessions like Lutheranism, Calvinism and Catholicism ‘developed into internally coherent and externally exclusive communities distinct in institutions, membership and belief’.21 The con-fessionalization thesis has proven invaluable for scholars investigating the synergis-tic relationship between confessional identity and the territorial state in the Holy Roman Empire and the roles played by state churches. However, its utility in other areas has been questioned.22 One shortcoming, identified by Thomas Kaufmann, has been the repercussions of the thesis for investigations of heresy.23 Namely, the pos-tulation of homogenous confessional entities leaves little room for analysing the nuances of identity negotiation or dissimulation in this period. Kaufmann has instead argued that ongoing Lutheran debates concerning heresy contributed to pro-cesses of inner-confessional self-definition (innerkonfessionelle Selbstverständigung), and not necessarily processes of exclusion, as the confession-alization thesis might predict. Kaufman argues persuasively that Lutheran doctrinal-ists did not dismiss the Schwärmer, chiliasts and dissenters that they wrote against

19 The idea of Lutheran confessional culture has been adopted from the work of Thomas Kaufmann, Dreißigjähriger Krieg und Westfälischer Friede. Kirchengeschichtliche Studien zur lutherischen Konfessionskultur. (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 1998), and Kaufmann, Konfession und Kultur. Lutherischer Protestantismus in der zweiten Hälfte des Reformationsjahrhunderts. (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2006), 14–21. I rely in this work on Clifford Geertz’s anthropologically derived definition of culture as ‘an historically transmitted pattern of meanings embodied in symbols, a system of inherited conceptions expressed in symbolic forms by means of which men communi-cate, perpetuate, and develop their knowledge about and their attitudes toward life’. See Geertz, Interpretation of Cultures (New York: Basic Books, 1973), 89.20 See Harm Klueting, ‘Die Reformierten in Deutschland des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts und die Konfessionalisierungsdebatte der deutschen Geschichtswissenschaft seit ca. 1980,’ in Profile des reformierten Protestantismus aus vier Jahrhunderten. M. Freudenberg, ed. (Wuppertal: Foedus 1999), 17–47.21 Heinz Schilling, ‘Confessional Europe,’ in Handbook of European History 1400–1600. Thomas A. Brady, Heiko Oberman, James D. Tract, eds. (Leiden: Brill, 1995), 641. See also Wolfgang Reinhard, ‘Gegenreformation als Modernisierung? Prolegomena zu einer Theorie des konfessio-nellen Zeitalters,’ Archiv für Reformationgeschichte 68 (1977): 226–252, and the essays collected in Heinz Schilling, ed. Die Reformierte Konfessionalisierung in Deutschland. Das Problem der “Zweiten Reformation.” (Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus 1986).22 Hartmut Lehmann, ‘Grenzen der Erklärungskraft der Konfessionalisierungsthese,’ in Interkonfessionalität – Transkonfessionalität – binnenkonfessionelle Pluralität. Neue Forschungen zur Konfessionalisierugsthese. Kaspar von Greyerz et al., eds. (Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 2003), 242–250.23 Thomas Kaufmann, ‘Nahe Fremde: Aspekte der Wahrnehmung der “Schwärmer” im früh-neuzeitlichen Luthertum,’ in Greyerz, et al., eds. Interkonfessionalität, 181; Kaufmann, Konfession und Kultur, passim; See also Anne Conrad, ‘Bald papistisch, bald lutherisch, bald schwenkfel-disch. Konfessionalisierung und konfessioneller Eklektizismus,’ Jahrbuch für Schlesische Kirchengeschichte 76/77 (1997/98): 1–25.

Introduction

xvi

as ‘opponents without’ (äußere Gegner). Instead, they were recognized as ‘strang-ers within’ (nahe Fremde).24 Kaufmann’s insight offers a useful paradigm with which to consider the relationship between Lutheran confessional culture and its supposed dissenters.

This still leaves us with the problem of how to position ‘heretics’ in relation to doctrinal Lutheranism. In 1934, Arnold Schleiff (1911–1945) called attention to traditions of ‘internal criticism’ (Selbstkritik) within early modern Lutheranism, thereby drawing attention to the different ways that Lutheran doctrine was promul-gated, understood and even challenged, by confessing Lutherans.25 In 1984, Russell Hvolbek discussed the influential Lusatian theosopher Jacob Böhme (1575–1624) as part of a tradition of ‘outsider Lutheranism,’ that is to say of a reform-oriented culture within Lutheranism potentially receptive to Schwenkfeldian, Franckist or Paracelsian doctrines, which never sought to break from the Lutheran church itself.26 Similarly, in a series of insightful studies concerning the Tübingen bookseller Eberhard Wild (1588–ca. 1635), a Lutheran condemned in 1620 for publishing sus-pect religious literature, Ulrich Bubenheimer and Dieter Fauth applied categories of religiöse Devianz or Kryptoradikalität.27 These terms were coined to designate those personalities who publicly confessed a particular faith—such as Lutheranism—but who advocated beliefs that might have been considered heterodox by some doc-trinal authorities.28 The Zschopau pastor Valentin Weigel (1533–1588) or the

24 Kaufmann, ‘Nahe Fremde’, 181–182.25 Arnold Schleiff, Selbstkritik der lutherischen Kirchen im 17. Jahrhundert (Berlin: Junker & Dünnhaupt, 1937).26 Russell H. Hvolbek, ‘Seventeenth-Century Dialogues: Jacob Boehme and the New Sciences’. Unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Chicago, 1984, 102–103.27 Initially, Bubenheimer and Fauth proposed the terms Kryptoheterodoxie or Kryptodissidentismus but ultimately abandoned them as being too reliant on a prevailing concept of orthodoxy. See Ulrich Bubenheimer, ‘Von der Heterodoxie zur Kryptoheterodoxie. Die nachreformatorische Ketzerbekämpfung im Herzogtum Württemberg und ihre Wirkung im Spiegel des Prozesses gegen Eberhard Wild,’ Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte 110 (1993): 307–341; Ulrich Bubenheimer, ‘Literatur- und Sozialprofil der Krypto-Heterodoxie in Tübingen und Württemberg um 1620,’ Historical Social Research-Historische Sozialforschung 18 (1993): 135–141; Ulrich Bubenheimer, ‘Rezeption und Produktion nonkonformer Literatur in einem protestantischen Dissidentenkreis des 17. Jahrhunderts,’ in Religiöse Devianz in christlich geprägten Gesellschaften. Vom hohen Mittelalter bis zur Frühaufklärung. D. Fauth and D. Müller eds. (Würzburg: Religion & Kultur, 1999), 106–125; Ulrich Bubenheimer, ‘Schwarzer Buchmarkt in Tübingen und Frankfurt: zur Rezeption nonkonformer Literatur in der Vorgeschichte des Pietismus,’ Rottenburger Jahrbuch für Kirchengeschichte 13 (1994): 149–163; Dieter Fauth, ‘Die Typusentwicklung des heterodox Gebildeten im Kontext der Hochorthodoxie: Zur Sozialgeschichte eines Tübinger Kreises um 1620,’ Literaten-Kleriker-Gelehrte. Zur Geschichte der gebildeten im vormodernen Europa. (Cologne: Böhlau, 1996), 245–268; Dieter Fauth, ‘Verbotener Bildung in Tübingen zur Zeit der Hochorthodoxie: eine sozialgeschichtliche Studie zum Zensurfall des Buchhändlers und Druckers Eberhard Wild (1622/23),’ Zeitschrift für württembergische Landesgeschichte 53 (1994): 1–17; Dieter Fauth, ‘Dissidentismus und Familiengeschichte. Eine sozial- und bildungsgeschich-tliche Studie zum kryptoheterodoxen Tübinger Buchdrucker Eberhard Wild (1588-um1635),’ Rottenburger Jahrbuch für Kirchengeschichte, 13 (1994): 165–178.28 Bubenheimer, ‘Von der Heterodoxie zur Kryptoheterodoxie,’ 308, 314. See further Perez Zagorin, Ways of Lying. Dissimulation, Persecution and Conformity in Early Modern Europe

Introduction

xvii

Lutheran devotional author Johann Arndt (1555–1621) are perhaps model examples of the ‘cryptoradical’ personality.

All of these historians strove to define an analytical space in which to locate persons who were raised within Lutheran confessional culture, who self-identified as Lutherans and yet who, for whatever reason, might not have been regarded as members of that faith by some guardians of orthodoxy. All cultures—social, reli-gious, intellectual or otherwise—possess subcultures and countercultures, which draw on and react to common impulses in the confessional ‘mainstream’. This dynamic exchange is a feature of all cultures, historical and current.29

While the works of those Lutherans who anticipated a felicitous future before the Last Judgment were often anticlerical and thus critical of institutionalized Lutheranism, this hardly distances their authors from their backgrounds in the faith. They were just as much a product of Lutheran confessional culture as a village pas-tor or university-based theologian.30 With this in mind, I use terms like Lutheran and Lutheranism in this study to designate defenders of Lutheran doctrine that com-bated chiliastic heresy, as well as those who were raised within or otherwise adhered to the faith but were critical of it. This definition recognizes the plurality of possible experiences of seventeenth-century Lutheranism, the ‘fractions’ (innerlutherische Fraktionen) that comprised broader Lutheran confessional culture.31 The question of what was acceptable and who was or was not Lutheran between 1570 and 1630 is not always clear-cut. The example of the debates on chiliastic heresy and optimis-tic apocalypticism demonstrate that the line dividing heretic and confessing mem-ber of the faith was mutable.

While several scholars have engaged with the role of pessimistic apocalypticism in early seventeenth century Lutheranism, there has been little attention paid to optimistic expectations.32 A reason for this lack of attention may be historical.

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990); Günther Mühlpfordt and Ulman Weiß, ‘Kryptoradikalität als Aufgabe der Forschung,’ in Kryptoradikalität in der Frühneuzeit. Günther Mühlpfordt and Ulman Weiß, eds. (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2009), 9–16.29 Cass R. Sunstein, Why Societies Need Dissent (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003).30 Kaufmann, Dreißigjähriger Krieg und Westfälischer Friede, 139–154. Further the essays in Greyerz, et al., eds. Interkonfessionalität – Transkonfessionalität – binnenkonfessionelle Pluralität (2003).31 Uwe Korde and John Brian Walmsely, ‘Eine verschollene Gelehrtenbibliothek. Zum Buchbesitz Wolfgang Ratkes um 1620,’ Wolfenbütteler Notizen zur Buchgeschichte 20/2 (1995), 133–171 at 135.32 See Barnes, Prophecy and Gnosis; Hartmut Lehmann, ‘Endzeiterwartungen im Luthertum im späten 16. und im frühen 17. Jahrhundert,’ in Die lutherische Konfessionalisierung in Deutschland. Hans-Christoph Rublack, ed. (Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlaghaus, 1992), 545–554; Leppin, Antichrist und Jüngster Tag. Compare however the literature on Northern Europe, much of which has fruitfully engaged with optimistic and pessimistic apocalyptic expectations; Henrik Sandblad, De eskatologiska föreställningarna i Sverige under reformation och motreformation. (Uppsala: Almqvist, 1942); Sten Lindroth, Paracelsismen i Sverige till 1600-tallets mit. (Uppsala: Almqvist, 1943); Hans Joachim Schoeps, Philosemitismus im Barock. Religions- und Geistesgeschichtliche

Introduction

xviii

Because chiliasm was a heresy, chiliasts were per definitionem not proponents of Lutheran doctrine and therefore were excluded from many considerations of the history of the church by confessional historians. As such, the earliest consideration given to optimistic expectations was restricted to heresiographies like Heinrich Corrodi’s still-valuable Kritische Geschichte des Chiliasmus (1781–1783) or Johann Christoph Adelung’s Geschichte der menschlichen Narrheit (1785–1789), manifes-tations both of the desire to create an Enlightenment pathology of heresy.33 Yet the need for further interrogation of this material is glaring. One recent article consid-ered the terms chiliasmus crassus and chiliasmus subtilis—designations introduced by Lutheran theologians in the seventeenth century—to be an anachronistic distinc-tion first coined in the 1930s.34

It is only recently that scholarly attention has been devoted to the specific issues raised by expectations of a felicitous future within Lutheran confessional culture. The majority of these studies have concentrated on expectations within Pietism, particularly after circa 1675, when Philipp Jakob Spener (1635–1705) introduced the doctrine of a ‘hope for better times’ (Hoffnung besserer Zeiten) into Lutheranism. Spener’s expectations were a clear departure from doctrinal norms and, as such, ignited ferocious contemporary debate about the potential value that such ideas could play within Lutheranism.35

The first notable study on chiliasm and Lutheranism in the period before 1675 was authored by Johannes Wallmann, one of Pietism’s most distinguished scholars. His landmark 1982 article ‘Zwischen Reformation und Pietismus’ provided an ini-tial survey of the place of chiliastic heresy within Lutheranism between 1597 and ca. 1691.36 In addition to providing an initial sketch of the various doctrinal state-

Untersuchungen (Tübingen: Mohr (Siebeck), 1952); Pentti Laasonen, ‘Chiliastische Strömungen aus dem Baltikum nach Skandinavien im 17. Jahrhundert,’ in Makarios-Symposium über das Gebet. J. Martikainen and H.-O. Kvist, eds. (Åbo: Åbo Akademis Forlag, 1989), 158–168; Pentti Laasonen, ‘Die Anfänge des Chiliasmus im Norden,’ Pietismus und Neuzeit 16 (1993): 19–45.33 See Simone Zurbruchen, ‘Heinrich Corrodi’s Critical History of Chiliasm, 1781–1783,’ in Histories of Heresy in Early Modern Europe. For, Against, and Beyond Persecution and Tolerance. Johann Christian Laursen, ed. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002), 189–203.34 Hans-Joachim Müller, ‘Kriegserfahrung, Prophetie und Weltfriedenskonzepte während des Dreißigjährigen Krieges,’ Jahrbuch für Historische Friedensforschung, 6 (1997): 33–34.35 Kevin R. Baxter, ‘From Cooperative Orthodox Optimism to Passive Chiliasm: The Effects of the Evolution in Spener’s Zukunftshoffnung on his Expectations, Ideas, Methods and Efforts in Church Renewal’. Ph.D. dissertation, Northwestern University, 1993; Heike Krauter-Dierolf, Die Eschatologie Philipp Jakob Speners. Der Streit mit der lutherischen Orthodoxie um die ‘Hoffnung besserer Zeiten’. (Tübingen: Mohr (Siebeck), 2005); Heike Krauter-Dierolf, ‘Die Hoffnung künft-iger besserer Zeiten: Die Eschatologie Philipp Jakob Speners im Horizont der zeitgenössischen lutherischen Theologie,’ in Geschichtsbewusstsein und Zukunftserwartung in Pietismus und Erweckungsbewegung. Wolfgang Breul and Jan Carsten Schnurr, eds. (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2013), 56–68.36 Johannes Wallmann, ‘Zwischen Reformation und Pietismus. Reich Gottes und Chiliasmus in der Lutherischen Orthodoxie,’ in Verifikationen: Festschrift für Gerhard Ebeling zum 70. Geburtstag. (Tübingen: Mohr (Siebeck), 1982): 187–205. A revised version of this article was printed as Wallmann, ‘Reich Gottes und Chiliasmus in der lutherischen Orthodoxie,’ in Wallmann, Theologie und Frömmigkeit im Zeitalter des Barock. Gesammelte Aufsätze (Tübingen: Mohr (Siebeck),

Introduction

xix

ments on chiliasm authored by Lutheran theologians during the period, Wallmann identified a trend among authors of devotional literature toward the expression of optimistic apocalyptic ideas. The most important figure in this regard was perhaps Paul Egard (ca. 1578–1655), pastor in Nortorf, Holstein. According to Wallmann, in 1623, Egard became the first Lutheran cleric to attempt to reconcile apocalyptic meliorism with doctrinal Lutheranism.37 The present study confirms Wallmann’s conclusions to a large extent, but it also demonstrates that there were a variety of sources and individuals, both lay and clerical, who advocated optimistic expecta-tions within Lutheranism of this period. Wallmann’s survey, which has inspired a host of studies on the role of apocalypticism in Pietism, demonstrated that fresh questions had to be asked of the relationship between Lutheranism and optimistic apocalypticism and simultaneously showed that Lutheran apocalypticism of the early seventeenth century was far more nuanced than generally recognized. This view has been deepened by more recent studies of Pietism and chiliasm.38

Many of the implications of Wallmann’s study have been taken up by the American historian Robin Bruce Barnes. Barnes’s careful work has drawn attention to the diverse roles played by apocalyptic expectations in the formation of Lutheran confessional identity and also provided key insights into the role of discourse on chiliasm and optimistic apocalyptic expectations during this period. In his Prophecy and Gnosis (1988), Barnes embedded the polemical struggle of doctrinal Lutherans against chiliastic error within the broader matrix of Lutheran confessional culture, emphasizing that the categorization of optimistic apocalyptic visions as a heresy was part of a broader conflict concerning authority and its limits within the Lutheran church.39 This is a key insight that provides perspective on the ‘sudden’ emergence of heresiological discourse on chiliasm in the 1610s, when religious, political and environmental pressures converged on an already-embattled Lutheranism. One part of this conflict was a concerted effort by Lutheran theologians to curb apocalyptic speculations that had once enjoyed ‘virtual doctrinal sanction’ in the sixteenth cen-tury. Barnes noted that although the influence of apocalypticism was largely conser-vative, apocalyptic awareness suffused every aspect of early modern Lutheranism and, as a result, produced members of the confession perfectly happy to entertain scenarios of a future ‘world reformation’.40 Such individuals, as Barnes notes, could

1995), 105–123. I cite from the revised version in the present study, except where the original contains unique information.37 Wallmann, ‘Reich Gottes und Chiliasmus,‘117–119.38 See, for example, Inge Mager, ‘Chiliastische Erwartungen in der lutherischen Theologie und Frömmigkeit des 17. Jahrhunderts. Niedersächsische ‘Gewährsmänner’ für Speners Hoffnung besserer Zeiten in der Kirche,’ Zeitschrift für bayerische Kirchengeschichte 69 (2000): 19–33; Udo Sträter, ‘Philipp Jakob Spener und der Stengersche Streit,’ Pietismus und Neuzeit 18 (1992): 40–79; Martin Friedrich, Zwischen Abwehr und Bekehrung. Die Stellung der deutschen evange-lischen Theologie zum Judentum im 17. Jahrhundert. (Tübingen: Mohr (Siebeck), 1988).39 Barnes, Prophecy and Gnosis, 228–260, 240, 318 n. 29. The topos of authority as a key aspect of apocalyptic rhetoric has since been emphasized by O’Leary, Arguing the Apocalypse and Hall, Apocalypse.40 Barnes, Prophecy and Gnosis, 227.

Introduction

xx

be found in clerical as well as lay circles. In a later study, Barnes used the example of astrology to demonstrate the depth of the Lutheran pursuit of insight into the End Times, revealing a picture of a porous confessional and intellectual culture eventu-ally pulled apart by ‘centrifugal forces,’ with all sides issuing competing claims to divine authority.41

A different approach to the Lutheran engagement with apocalyptic thought was taken by the German theologian and historian Volker Leppin. In his Antichrist und Jüngster Tag (1999)—a survey of the content of a selection of apocalyptic Flugschriften issued between 1548 and 1618—Leppin portrayed the varieties of historicist readings of eschatology and prophecy within Lutheranism as attempts to reduce uncertainty by bringing all events, whether natural, political or theological, within a flexible framework of interpretation.42 For Leppin, apocalyptic expressions were central to Lutheran processes of social discipline as well as confessional iden-tity. While Leppin’s argument is impressively documented, its bibliometric focus means it passes over the specific circumstances of the production of the apocalyptic expressions it characterizes. Equally, Leppin’s categorization of apocalyptic writ-ings risks obscuring the chaotic and diverse reality of these expressions initially documented by Barnes and demonstrated further in the present study. Indeed, the debates concerning chiliasm play only a minor role in Leppin’s representation of Lutheran apocalypticism, which otherwise provides an impressive survey of the apocalyptic material and attitudes during this period.

While Matthias Pohlig similarly emphasized the conservative influence of apoc-alyptic ideas within confessional contexts in an essay on patterns of eschatological interpretation during the Thirty Years’ War,43 Walter Sparn showed the importance of optimistic apocalypticism as a framework for interpretation of contemporary events in an article devoted to the social and psychological appeal of such ideas in the seventeenth century.44 For Sparn, these expectations were product of a series of interlocking ‘crises’, social, military and economic, experienced during the early seventeenth century.45 When these perceived crises collided with new devotional strategies and understandings of the role of the self in devotional practice, an entry point was created for ‘individualistic’ apocalyptic hopes within Protestant confes-sions.46 While there has since been much work conducted on the impact of the crises of the late sixteenth century and its ramifications for the seventeenth, Sparn’s short study added to prior attempts to explain the appeal of optimistic eschatological

41 Robin Bruce Barnes, Astrology and Reformation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).42 Leppin, Antichrist und Jüngster Tag, 289–90.43 Matthias Pohlig, ‘Konfessionskulturelle Deutungsmuster internationaler Konflikte um 1600: Kreuzzug, Antichrist, Tausendjähriges Reich,’ Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte 93 (2002): 278–316.44 Walter Sparn, ‘Chiliasmus crassus und Chiliasmus subtilis im Jahrhundert Comenius,’ in Johann Amos Comenius und das moderne Europa. Norbert Kotowski, Jan B. Lasek, eds. (Fürth: Flacius-Verlag 1992), 122–129.45 Sparn, ‘Chiliasmus crassus und Chiliasmus subtilis,’ 124.46 Sparn, ‘Chiliasmus crassus und Chiliasmus subtilis,’ 126.

Introduction

xxi

ideas with reference to events of the Thirty Years’ War, as in the widely cited doc-toral theses of Roland Haase and Herbert Narbuntowicz.47 However, as Barnes has argued powerfully and the present study further demonstrates, Lutheran interest in and debate about optimistic eschatology was a result of features of the confessional culture which existed well before 1618.

Other recent research has drawn attention to the dynamic nature of these negotia-tions by examining the early modern reformatio mundi as an expression of ‘outsid-ers, dissenters, and competing visions of reform’ reaching back to the Middle Ages.48 In this particular view of the ‘long Reformation’ figures like Johann Valentin Andreae (1586–1654), Jacob Böhme and many of the individuals discussed in this volume stand alongside magisterial reformers like Luther, Jean Calvin (1509–1564) and Huldrych Zwingli (1484–1531) as representatives of an ameliorative desire to better the world through the articulation of platforms of religious and worldly reform. The Reformation of Luther and his followers and the debates concerning heresy that followed were an almost inevitable result of the slippage created between colliding philosophies of reform. Seen in this way, Lutheranism’s native pessimistic apocalypticism can be understood as a paradoxical reflection of a melioristic impulse at the heart of the reforming agenda.

Whatever their differences in approach and conclusions, all of the studies men-tioned above demonstrate that apocalyptic doctrines occupied an important, though inherently volatile, basis for confessional identity in the seventeenth century. Hope and Heresy builds on these works to portray the chaotic debates concerning chilias-tic heresy and optimistic expectations that took place within Lutheran confessional culture between 1570 and 1630. At the heart of the study is a paradox. Where pro-ponents of optimistic expectations were often inspired to propose their visions in order to impose order on the world, defenders of Lutheran doctrine were arguably moved by a similar impulse to establish order by curbing these same expressions. A defining factor was authority. Although it focuses specifically on the contested doc-trine of chiliasm and its relationship to optimistic expectations, the implications of this study are broad. This study not only contributes to scholarly debates concerning the status, role and place of eschatological and apocalyptic ideas in European his-tory but also contributes to testing the limits of early modern efforts of confession-

47 Roland Haase, Das Problem des Chiliasmus und der Dreißigjährige Krieg (Leipzig: Gerhardt, 1933); Herbert Narbuntowicz, ‘Reformorthodoxe, spiritualistische, chiliastische und utopische Entwürfe einer menschlichen Gemeinschaft als Reaktion auf den Dreißigjährigen Krieg’. PhD dissertation. Albert-Ludwigs-Universität zu Freiburg im Breisgau, 1994.48 Hans Leube, Die Reformideen in der deutschen lutherischen Kirche zur Zeit der Orthodoxie (Leipzig: Francke, 1924); Hans Leube, Orthodoxie und Pietismus. Gesammelte Studien. Dietrich Blaufuß, ed. (Bielefeld: Luther-Verlag, 1975), 19–35; Fred A. van Lieburg, ‘Conceptualising Religious Reform Movements in Early Modern Europe,’ in Confessionalism and Pietism. Religious Reform in Early Modern Europe. Fred A. van Lieburg, ed. (Mainz: Verlag Philipp van Zabern, 2006), 1–10; Howard Hotson, ‘Outsiders, Dissenters, and Competing Visions of Reform,’ The Oxford Handbook of Protestant Reformations. Ulinka Rublack, ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 301–328.

Introduction

xxii

alization, as well as calling attention to the pluralities of experience possible in early modern religiosity.

∗∗∗

The present study is based upon the evaluation of a selection of contemporary print and manuscript sources. They are listed in the bibliography. These sources were accessed mostly on site in European archives and libraries but also through digitizations accessible through bibliographical databases like Das Verzeichnis der im deutschen Sprachraum erschienenen Drucke des 17. Jahrhunderts (http://www.vd17.de), among others. Throughout this study, I have made use of the extensive secondary literature on religious debates of the seventeenth century. In addition to the scholarly contributions mentioned in the survey of prior research above, I found a great deal of relevant material in more obscure local history journals from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, many of which reprinted manuscripts that are no longer extant.

At the heart of this study is the idea, first postulated by Robin Barnes, that Lutheran confessional culture experienced an intensification and an ever-deepening quest for apocalyptic insight around the turn of the seventeenth century. This inten-sification was built on the back of the search for deeper insights into the Last Days that defined the sixteenth century.49 It manifested itself in the establishment of ad hoc correspondence networks of like-minded individuals and led to the creation of subcultures of scribal publication dedicated to distributing materials in a manuscript form. But this intensification of interest is most apparent when tabulating the num-ber of printed works concerning optimistic apocalyptic thought issued between 1600 and 1630. During these three decades, some 367 printings (both issues and editions) of 300 unique works addressing the topic circulated both, commercially, through booksellers and, privately, through networks of trust.

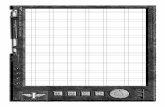

A list of these works—which represents some, but certainly not all, of the mate-rial actually printed during this period—is presented in the appendix. This list pro-vides an indication, however impressionistic, of the intensity and intensification of Lutheran engagement with apocalyptic expectations of a future felicity between 1600 and 1630. It does not take into consideration the large quantity of scribal pub-lications circulating at this same time. In total, at least 53 individual critics of Lutheran culture wrote and printed 202 books, pamphlets and broadsheets that advocated optimistic expectations, which appeared in 260 separate issues. During the same period, no less than 46 Lutherans printed some 83 books against these works, which went through at least 95 issues. The profile and trajectory of this intensification are demonstrated in Fig. 1. It demonstrates that publications concern-ing optimistic apocalyptic expectations were circulating well before the outbreak of the Bohemian Revolt in 1618. Equally, it indicates an intensification in the printing of books on these subjects between 1617 and 1623, during the early phase of the revolt and the lead up to the great conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in 1623. The

49 Barnes, Prophecy and Gnosis; Barnes, Astrology and Reformation.

Introduction

xxiii

comparatively late voicing of opposition to the growing expression of these ideas by clerics and others is also evident. This delayed onslaught, in combination with the disappointment of expectations concerning a felicitous future after 1623, led to a decline in the printing of books concerning optimistic apocalyptic expectations in the lead up to 1630.

As Jonathan Green has recently pointed out, prophecy, which relied on divine speech, is foremost a social and media phenomenon: ‘what defines a prophet is not the prediction of future events but the communicative claims made by the prophet and accepted by his or her audience’.50 Apocalyptic works contained a plethora of prophetic claims which naturally concerned future events, and with the tendency of some representatives of optimistic expectations within Lutheranism to define them-selves as members of a ‘School of the Holy Spirit’, these figures also sought to define themselves as mediators between God and the average person. Convictions held privately die with their thinker. What is significant about the optimistic apoca-lyptic literature of the period between 1600 and 1630 within German Lutheranism is that arguments about prophetic authority, and therefore religious authority, were rehearsed in public.

The promulgation and contestation of these prophetic visions in print is likely the tip of the iceberg when it comes to engagement with optimistic apocalypticism within Lutheran confessional culture. The circulation of printed works was

50 Jonathan Green, Printing and Prophecy: Prognostication and Media Change 1450–1550 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2012), 1.

28

26

24

22

20

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

1600

1601

1602

1603

1604

1605

1606

1607

1608

1609

1610

1611

1612

1613

1614

1615

1616

1617

1618

1619

1620

1621

1622

1623

1624

1625

1626

1627

1628

1629

1630

Lutheran Pro Calvinist Lutheran Contra

Fig. 1 Printed works concerning optimistic Apocalypticism, 1600–1630

Introduction

xxiv

supported and underwritten by the circulation of scribal publications. As the bibli-ography to the present volume indicates, such publications today survive haphaz-ardly in libraries throughout the world. They are often difficult to date reliably, let alone to attribute to specific compilers or copyists. Nevertheless, their existence provides conclusive evidence that textual cultures existed around anticlerical and optimistic apocalyptic expectations. The survival of scribal publications, and of more than three dozen or so copiously annotated copies of printed works issued between 1600 and 1630—featuring manicules, underlining, comments and nota bene—show that these books, pamphlets, broadsheets and manuscripts were not only being produced but were read. They circulated in proactive reading communi-ties that consumed, interpreted, shared, communicated and engaged with these works in manners both sympathetic and sometimes adversarial.51 This community of readers did not merely absorb the doctrines they encountered; it was also inspired by them. The cases of Paul Felgenhauer, Paul Egard, Wilhelm Eo Neuheuser and numerous others discussed in the following chapters demonstrate that exposure to preexisting prophecies played a key role in inspiring the optimistic expectations of lay Lutherans.

Hope and Heresy is divided thematically into two separate halves, consisting of chapters arranged both thematically and broadly chronologically. The first half of the volume—comprising Chaps. 1, 2 and 3—concerns the origins of the optimistic apocalyptic expressions of the early seventeenth century and how and why these beliefs were taken up by some within Lutheran confessional culture. The focus in this section is almost entirely on lay persons. The second half—comprising Chaps. 4, 5 and 6—concerns both the reaction of Lutheran clerics to these expressions and the optimistic expectations expressed by clerical critics. It is these later chapters in particular that demonstrate the extent of the confusion that reigned in the debates concerning chiliasm and offer insight into the subsequent problems of confessional self-definition this entailed.

Chapter 1 traces the immediate background, both in terms of its sources and its various contexts, to the Lutheran interest in visions of a coming felicity of the early seventeenth century. It demonstrates the decisive impact of Paracelsian and non-Lutheran ideas upon Lutheran apocalypticism, the engagement with which was encouraged by a series of interlocking crises in the final decades of the sixteenth century. This prolonged search for further insight into the End Times among Lutherans led, in the first decades of the seventeenth century, to a flurry of publica-tions both printed and scribal which promoted optimistic expectations of a coming Golden Age. These publications, and their authors, are subjects of Chap. 2, which aims to give an impression of the diversity of expectations being circulated during

51 Perhaps the most interesting example of an annotated text is the copy of Johann Germanus, Der siebenden Apocalyptischen Posaunen, von Offenbarung verborgener Geheimnussen Heroldt … sampt Etlich tracts über die Newen Propheten. (Newenstadt: Johann Knuber 1626), in Halle, Universitätsbibliothek, shelfmark AB 153266, which contains several hundred marginal notations, in inks of various colours, evidently as an aide to navigating and engaging with the ideas of the text.

Introduction

xxv

this period. Chapter 3 presents detailed case studies of two prominent lay Lutherans that published widely their optimistic apocalyptic expectations: Paul Nagel (ca. 1575–1624) and Wilhelm Eo Neuheuser (fl. 1583–1626). Despite their radical dif-ferences, both were motivated by a desire to posit order in the face of chaos and elaborated an apocalyptic vision subject directly to the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, therefore impervious to critique by worldly theologians.

These expressions did not go unnoticed by defenders of Lutheran doctrine, some of whom sought to condemn them as manifestations of chiliastic heresy. Chapter 4 provides a diachronic account of the evolution of the definitions of this heresy between ca. 1570 and 1630 and draws attention to the circulation of conflicting and contradictory definitions. Although these condemnations sought to define and defend confessional identity, they ultimately sowed confusion and led to the retro-spective condemnation of doctrines once considered orthodox. The fallout of this situation is treated in Chap. 5, which examines the cases of four clerics who pro-moted optimistic apocalyptic scenarios. This chapter shows that optimistic apoca-lypticism could appeal to clerics as well as lay Lutherans. But there were also other outcomes; the sad case of the Danzig preacher Hermann Rahtmann (1585–1628) demonstrates that attempts by Lutherans to articulate blanket or unspecific defini-tions of chiliasm could lead to the creation of heretics even where they did not exist. Chapter 6 examines a text that probably comprises the first attempt to incorporate optimistic apocalyptic expectations into orthodox Lutheranism: Paul Egard’s Posaune der Göttlichen Gnade und Liechtes (1623). Extensively familiar with con-temporary heterodox literature, Egard was one of the few Lutheran clerics who advocated not the suppression but the promotion of expectations of a felicitous future as a means of bridging the growing gap between doctrine and devotion.

Finally, a brief chapter is devoted to the aftermath of the mass disappointment of prophecies and expectations for the year 1623. This chapter also includes a consid-eration of the later history of optimistic expectations within Lutheran confessional culture and points to the epochal shift that the failures of 1623 caused, not only within Lutheranism but within Protestant apocalyptic expectations more broadly. These disappointments, together with the efforts of doctrinal opponents of Lutheranism, created a turn toward a more personal eschatology within Lutheranism that rubbed shoulders with soteriology. As such, Lutheran apocalyptic culture largely retreated, for at least a little while, from grand-scale predictions informed by events of an apocalyptic scale. The aftermath of the mass prophetic disappointments of the 1620s demonstrate that Lutheran engagements with optimistic eschatology would possess wide-ranging consequences for Protestant culture of the seventeenth century as a whole. Equally, however, the place and status of optimistic eschatologi-cal narratives is by no means a question of mere historical interest. If ideas of prog-ress and of modernity prevalent in the West today have been informed by these narratives and expectations—in particular emerging from within Protestant confes-sional cultures—then the investigation of the history of the struggle between hope and heresy can contribute to current debates about the role of apocalyptic thought in shaping modernity.

Introduction

xxvii

Contents

1 The Three Mirrors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1The Mirror of Belief – Kirchen Spiegel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

The Eschatology of Paracelsus and His Followers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7Lutheran Syntheses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13The Rosicrucian Brotherhood . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18Devotional Authors in search of Certainty . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

The Mirror of Nature – Natur Spiegel. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28The Mirror of Worldly Affairs – Welt Spiegel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

2 The School of the Holy Spirit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37Paul Felgenhauer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38Philipp Ziegler . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42Johann Kärcher . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46Jacob Böhme . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48Paul Kaym . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51Heinrich Gebhard alias Wesener . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53Some Minor Prophets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56Scribal Publication and Manuscript Collectors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59The Reach of Printed Books . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

3 Two Prophetic Voices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73The Prophet of Torgau . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73Crisis and Transcendence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79The Universal Instrument . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81The Role of Hope . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84A Prophet Between Utopia and New Jerusalem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85The Seven Laws of the Holy United Roman Empire . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92The Reception of Neuheuser’s Works . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 98

xxviii

4 Optimism Outlawed . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99The Doctrinal Position . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101Paths to a Heresy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103The Creation of a Heresy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106A Confusion of Heretics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113The Changing Status of Lutheran Devotional Literature . . . . . . . . . . . . 120Reaping the Whirlwind . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125

5 Heretics in the Pulpit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127The Rahtmann Dispute . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 128Rahtmann’s Gnadenreich . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 129Rahtmann’s “Chiliasm” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 132The Opinions of the Theological Faculties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 134The Pastor of Nuremberg . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137Nicolaus Hartprecht . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 139Tuba Temporis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 140Joachim Cussovius and the Reception of Hartprecht’s

Tuba Temporis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 142The Messianic Turn . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 146Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151

6 A Lutheran Millennium . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153Paul Egard . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153Posaune der Göttlichen Gnade und Liechtes (1623) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 156An Unanticipated Millennium . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 160Some Sources of Egard’s Posaune . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 161The Reception of Posaune . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 164Egard’s Apocalypticism After 1623 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 167Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 169

7 Failed Prophecies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 171Failed Prophecy, Failed Prophets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 173

8 Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 189

Appendix . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 197

Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 211

Index of Scriptural Passages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 261

General Index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 263

Contents

xxix

Fig. 1 Printed works concerning optimistic Apocalypticism, 1600–1630........................................................................................ xxiii

Fig. 2.1 Paul Nagel, Tabula aurea (No Place: No Printer, 1624). (Title page. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University) .......................................................................... 68

Fig. 3.1 Paul Nagel, portrait from the title page of his Prognosticon astrologicum (1619). Woodcut. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University .............................................................. 77

Fig. 4.1 The tree of heresy. Engraving. From Daniel Cramer, Arbor hæreticæ consanguinitatis (1623). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University .............................................................. 177

List of Figures