Hoover Digest, 2011, No. 3, Summer

-

Upload

hoover-institution -

Category

Documents

-

view

287 -

download

12

description

Transcript of Hoover Digest, 2011, No. 3, Summer

T H E H O O V E R I N S T I T U T I O N

S ta n f o r d U n i v e r S i t y

R E S E A R C H A N D O P I N I O N O N P U B L I C P O L I C Y 2 0 1 1 · N O . 3 · S U M M E R

visit theHoover inStitUtion

online atwww.hoover.org

HOOVER DIGESTpeter robinsonEditor

charles lindseyManaging Editor

e. ann woodInstitution Editor

jennifer presleyBook Publications Manager

HOOVER INSTITUTION

herbert m. dwightChairman, Board of Overseers

robert j. osterboyd c. smithVice Chairmen, Board of Overseers

john raisianTad and Dianne Taube Director

david w. bradyDeputy Director, Davies Family Senior Fellow

richard sousaSenior Associate Director

david davenportCounselor to the Director

ASSOCIATE D IRECTORS

douglas bechlerstephen langloisdonald c. meyereryn witcher

ASSISTANT D IRECTORS

denise elsonmary gingelljames grossjeffrey m. jonesnoel s. kolakkathy phelan

The Hoover Digest offers informative writing on politics, economics, and history by the scholars and researchers of the Hoover Institution, the public policy research center at Stanford University.

The opinions expressed in the Hoover Digest are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, or their supporters.

The Hoover Digest (ISSN 1088-5161) is published quarterly by the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace, Stanford University, Stanford CA 94305-6010. Periodicals Postage Paid at Palo Alto CA and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the Hoover Digest, Hoover Press, Stanford University, Stanford CA 94305-6010.

© 2011 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University

Contact InformationWe welcome your comments and suggestions at [email protected] and invite you to visit the Hoover Institution website at www.hoover.org. For reprint requests, write to this e-mail address or send a fax to 650.723.8626. The Hoover Digest publishes the work of the scholars and researchers affiliated with the Hoover Institution and thus does not accept unsolicited manuscripts.

Subscription InformationThe Hoover Digest is available by subscription for $25 a year to U.S. addresses (international rates higher). To subscribe, send an e-mail to [email protected] or write to

Hoover DigestSubscription FulfillmentP.O. Box 37005Chicago, IL 60637

You may also contact our subscription agents by phone at 877.705.1878 (toll free in U.S. and Canada) or 773.753.3347 (international) or by fax at 877.705.1879 (U.S. and Canada) or 773.753.0811 (international).

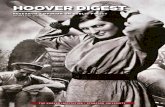

On the CoverA propaganda poster from the 1930s hints at China’s twentieth-century struggles for autonomy. This scarlet-and-gold image of a rising phoenix promotes not republican China, born after the Wuchang rebellion of 1911, but a brief, Japanese-controlled collaborationist regime called the Provisional Government of the Republic of China. A new exhibit at the Hoover Institution explores this and other milestones in China’s century of change, as well as one of its most significant agents of change, Sun Yat-sen. See story, page 206.

Hoover DigestResearch and Opin ion on Publ ic Po l icy

2011 • no. 3 • summer www.hooverdigest.org

HOOVER DIGESTpeter robinsonEditor

charles lindseyManaging Editor

e. ann woodInstitution Editor

jennifer presleyBook Publications Manager

HOOVER INSTITUTION

herbert m. dwightChairman, Board of Overseers

robert j. osterboyd c. smithVice Chairmen, Board of Overseers

john raisianTad and Dianne Taube Director

david w. bradyDeputy Director, Davies Family Senior Fellow

richard sousaSenior Associate Director

david davenportCounselor to the Director

ASSOCIATE D IRECTORS

douglas bechlerstephen langloisdonald c. meyereryn witchersusan wolfe

ASSISTANT D IRECTORS

denise elsonmary gingelljames grossjeffrey m. jonesnoel s. kolakkathy phelan

visit theHoover inStitUtion

online atwww.hoover.org

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3

ContentsHOOVER D IGEST · 2011 · NO . 3 · SU M M ER

DEMOCRACy IN THE ARAb WORlD

9 Like Striking a MatchThe spark seemed so small. But the Arab autocrats had spent decades heaping up the fuel. By fouad ajami.

16 An Unpredictable WindThe causes, the players, and the likely consequences of the Arab eruptions. A conversation with Hoover fellows peter berkowitz, victor davis hanson, and peter robinson.

28 The Roots of a Freedom AgendaThe Arab struggles may be new, but American goals are not. Three recent presidents laid the groundwork. By peter berkowitz.

33 Lands of Little RainDrought may not be destiny, but a critical ingredient for democratic societies does seem literally to fall from the skies. By stephen h.

haber and victor menaldo.

38 The Enemies of Our EnemyWe may not yet know what to do about the Islamists fighting in Libya, but we do know not to repeat certain mistakes. By joseph

felter and brian fishman.

43 Tigers of a Different StripeAfter their revolutionary fever cools, Arabs will have work to do. They could do worse than to emulate the booming Asian nations. By william ratliff.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3

I S lAM ISM

51 Trial of a Thousand YearsBehind the headlines lies an old and basic question: in the clash between Islamism and the nation-state, who will win? By charles

hill.

THE ECONOMy

61 How Could Inequality Be Good? If it prodded people to seek greater productivity, higher pay, and a better standard of living. By gary s. becker.

65 Sweet-Talking the “Fat Cats” Why businesspeople aren’t banking on Washington’s supposedly pro-business overtures. By stephen h. haber and f. scott kieff.

HEAlTH CARE

69 Doctored NumbersThe key justification for ObamaCare is “cost shifting”—that the insured pay a hidden tax to support the uninsured. But for the most part, such a shift does not, in fact, take place. By john f. cogan,

r. glenn hubbard, and daniel p. kessler.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3

lAbOR

73 Tear Up That Lousy Contract The economic crisis did at least one good thing: it forced us all to take a long, hard look at the enormous power of public-employee unions. By robert j. barro.

FORE IGN POl ICy

77 America’s Democratic CredentialsHoover fellow michael mcfaul, who has the president’s ear on Russia, argues that promoting freedom is both moral and wise.

84 Wishing Away the WorldForeign policy doesn’t mean righting every wrong. It means acting in our national interest. By bruce s. thornton.

EDUCAT ION

89 The Staggering Power of the Teachers’ UnionsA look at the most powerful force in American education—and it isn’t a force for good. By terry m. moe.

102 The States Are Back Whether racing to the top or sinking in debt (or both), some governors are taking the school-reform baton back from Washington. By chester e. finn jr.

ENERGy

107 Gone FissionUnreasoning fear is the wrong reaction to the Japanese reactor crisis. We can master the risks and reap the benefits of nuclear power. By

richard a. epstein.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3

I RAN

113 It Started with the ShahHoover fellow abbas milani on the rebellions in the Muslim world—and the monarch who set them off. An interview with charlie rose.

SAUD I ARAb IA

122 Will Change Come to the House of Saud?Reforms, if any, will depend on how modernizers and hard-liners settle their differences. By daniel pipes.

125 The Kingdom of CautionThe land where stability vies ceaselessly with stagnation. By joshua

teitelbaum.

139 Extending an Invitation to ReformThe United States has always been among the kingdom’s best friends. Who better to help it change? By leif eckholm.

RACE

147 Race and EconomicsWhat do black Americans need in order to get ahead? A truly free market. By walter e. williams.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3

I NTERV IEWS

154 Robert Conquest’s Five BooksThe eminent historian and Hoover fellow contemplates the communist mind. By alec ash.

160 “A Radical, a Troublemaker . . . ”As a scholar and a black American, walter e. williams has always been his own map. By nick gillespie.

VAlUES

170 The Core of Civic VirtueEither we teach the young to understand and appreciate their freedom, or we cheat them of their birthright. By william damon.

181 Honor in the TaskHow can we shore up the American work ethic? By honoring good work. By russell muirhead.

H ISTORy AND CUlTURE

187 Today’s Liberation TechnologiesA Cold War lesson that’s entirely relevant today: free people need free information. By a. ross johnson.

194 On the Road with AlexisNew insights into Alexis de Tocqueville, the genius who journeyed into the heart of American exceptionalism. By harvey c. mansfield.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3

HOOVER ARCH IVES

200 Tyranny 101Who better to coach a would-be dictator than Stalin? The curious episode of a foreign comrade who sought Stalin’s advice—which, of course, came at a cost. By paul r. gregory.

206 The Revolutionary RepublicIn 1911, China rejected feudalism to enter the modern era. A new Hoover exhibit on a century of change. By hsiao-ting lin and lisa

nguyen.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3 9

Like Striking a MatchThe spark seemed so small. But the Arab autocrats had spent decades

heaping up the fuel. By Fouad Ajami.

Historians of revolutions are never sure as to when these great upheavals in human affairs begin. But the historians will not puzzle long over the Arab revolution of 2011. They will know, with precision, when and where the political tsunami that shook the entrenched tyrannies first erupted. A young Tunisian vegetable seller, Mohamed Bouazizi, in the hardscrabble provincial town of Sidi Bouzid, set himself on fire after his cart was confis-cated and a headstrong policewoman slapped him across the face in broad daylight. The Arab dictators had taken their people out of politics, they had erected and fortified a large Arab prison, reduced men and women to mere spectators of their own destiny, and the simple man in that forlorn Tunisian town called his fellow Arabs back into the political world.

From one end of the Arab world to the other, all the more so in the tyr-annies ruled by strongmen and despots (Libya, Syria, Egypt, Yemen, Alge-ria, and Tunisia), the Arab world was teeming with Mohamed Bouazizis. Little less than a month later, the order of the despots was twisting in the wind. Bouazizi did not live long enough to savor the revolution of dig-nity that his deed gave birth to. We don’t know if he took notice of the tyrannical ruler of his homeland coming to his bedside in a false attempt at humility and concern. What we have is the image, a heavily bandaged man and a tacky visitor with jet-black hair, a feature of all the aged Arab

Fouad ajami is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, co-chairman of Hoover’s

Herbert and Jane Dwight Working Group on Islamism and the International

Order, and the Majid Khadduri Professor of Middle Eastern Studies at the School

for Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University.

DEMOCRACY IN THE ARAB WORLD

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 310

rulers—virility and timeless youth are essential to the cult of power in these places. Bids, we are told, were to come from rich Arab lands, the oil states, to purchase Bouazizi’s cart. There were revolutionaries in the streets, and there were vicarious participants in this upheaval.

A silent Arab world was clamoring to be heard, eager to stake a claim to a place in the modern order of nations. A question had tugged at and tormented the Arabs: were they marked by a special propensity for tyr-anny, a fatal brand that rendered them unable to find a world beyond the prison walls of the despotism? Better sixty years of tyranny than one day of anarchy, ran a maxim of the culture. That maxim has long been a prop of the dictators.

There is no shortage of autopsies of the Arab condition, and I hazard to state that in any coffeehouse in the cities of the Arabs, on their roof-tops that provide shelter and relief from the summer heat, the simplest of men and women could describe their afflictions: the predator states, the fabulous wealth side by side with mass poverty, the vanity of the rulers and their wives and their children, the torture in countless prisons, and the destiny of younger men and women trapped in a world over which they have little if any say.

No Arabs needed the numbers and the precision supplied by “devel-opment reports” that told of their sorrows, but the numbers and the data were on offer. The Arab Human Development Report of 2009—a United Nations project staffed by Arab researchers, the fifth in a series—provided a telling portrait of the world of 360 million Arabs. They were overwhelm-ingly young, the median age twenty-two, compared with a global average of twenty-eight. They had become overwhelmingly urbanized: 38 percent of the population lived in urban areas in 1970; it was now close to 60 percent. There had been little if any economic growth and improvement in their economies since 1980. No fewer than 65 million Arabs were living below the poverty line of $2 a day. New claimants were everywhere; 51 million

Why did the Arabs not rage last year, or the year before that, or in

the past decades? Because tyranny and state terror had yielded huge

dynastic dividends.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3 11

new jobs have to be created by 2020 to accommodate the young. Tyranny kept these frustrations in check. Eight Arab states, the report stated, prac-ticed torture and extrajudicial detention. And still, the silence held. Bouazizi and his deed of despair brought a people to a reckoning with its maladies.

A CHILL ING EXAMPLE OF DESPOT IC POWERWhy have the Arabs not raged before as they do now—why has there not been this avalanche of anger that we witnessed in Tunisia and Egypt and Libya and Syria? Why did the Arabs not rage last year, or the year before that, or in the last decades? An answer, one that makes the blood go cold, is Hama.

In retrospect, the Arab road to perdition—to this large prison that the crowds have set out to dismantle—must have begun in that Syrian city

Illus

tratio

n by

Tay

lor J

ones

for t

he H

oove

r Dig

est.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 312

in 1982. A conservative place in the central Syrian plains rose in rebel-lion against the military regime of Hafez Assad. It was a sectarian revolt, a fortress of Sunni Islam at odds with Assad’s Alawite regime. The battle that broke out in February of that year was less a standoff between a gov-ernment and its rivals than a merciless war between combatants fighting to the death. Much of the inner city was demolished, and perhaps twenty thousand people perished in that cruel fight. The ruler was unapologetic; he may have bragged about the death toll. He had broken the old culture of his country and the primacy of its cities.

Hama became a code word for the terror that awaited those who dared challenge the men in power. It sent forth a message in Syria, and to other Arab lands, that the tumultuous ways of street politics and demonstra-tions and intermittent military seizures of power had drawn to a close. Assad would die in his bed nearly two decades later, bequeathing power to his son, Bashar, who wields it today. Tyranny and state terror had yielded huge dynastic dividends.

The heart went out of Arab dissent and ideological argumentation. A new despotic culture took hold; men and women scurried for cover, lucky to escape the rulers’ wrath and the cruelty of the secret police, and the informers. Terrible men, insulated from their subjects (the word is the right one), put together regimes of enormous sophistication when it came to keeping their tyrannies intact. State television, the newspapers, mass politics, and the countryside spilling into the cities aided the despotisms. The tyrants, invariably, rose from modest social backgrounds. They had no regard for the old arrangements and hierarchies and for the limits a traditional society placed on the exercise of power.

Men like Muammar Gadhafi of Libya and Saddam Hussein of Iraq, like Hafez Assad of Syria, were children of adversity, and they were crueler for it, because traditional Arab society exalted pedigree and high birth. As the Arabs would put it—in whispers, in insinuations—no one knew the names of the fathers of these men who fell into things and acquired

No script was on offer—no revolution has ever followed a script—but the

people of Egypt were more than willing to trade tyranny for uncertainty.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3 13

political kingdoms of their own. The details varied from one Arab realm to another, but at heart the story was the same: a tyrant had emerged and restructured the political universe to his will. Milder authoritarianisms gave way to this “sultanist” system.

When the Egyptian rebellion erupted, it was foreordained that it would focus on the ruler and his family. Egyptians had grown weary of Hosni Mubarak, and the prospect of another Mubarak waiting in the wings was an affront to their dignity. The tyranny had sullied them, and they wanted to be done with the despot: “Irhall” (“Be gone”), the crowd would chant in unison. No script was on offer—no revolution has ever followed a script—but the people of Egypt were willing to trade this tyranny for the uncertainty of what was to come. Now the world-weary could tell them that their revolt may yet be betrayed, that they will break their chains only to forge new ones, that the theocrats are destined to replace the autocrats. But grant the Egyptian people their right to swat away these warnings.

Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali of Tunisia was shaped of the same mold as Mubarak. He had been a man of the police and the security services. True, his predecessor, the legendary Habib Bourguiba, hero of Tunisia’s indepen-dence, had ruled uncontested for three decades until Ben Ali pushed him aside in 1987. But Bourguiba was a cultured man; he knew books and literature; he had high aspirations for his country and its modernity. His political history placed him above his contemporaries, and he could take his primacy for granted. It would have appalled him to think of himself as a warden of his people—a thought and a reality that never troubled Ben Ali.

The greed of Ben Ali’s family and his in-laws, the speed with which they all clamored out of the country at the first sign of danger, told vol-umes about this despotism. There was no patriotism and love of home here: a predator and his ambitious wife, the hairdresser who had come out of nowhere to the pinnacle of power, made a run for it. It had been quite a racket for them, and it was now time to quit the land they had plundered and enraged.

Men like Muammar Gadhafi and Saddam Hussein and Hafez Assad were

children of adversity, and they were crueler for it.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 314

This, too, the plundering, marks a great discontinuity with the past. The despots of the day dispose of enormous wealth. The fortunes of the rulers, an Arab businessman once said to me, are the real weapons of mass destruction in the region.

REJECT ING THE RUL ING CASTEOne way or the other, the men at the helm became a ruling caste. They harked back to a pattern of rule that had befallen the world of Islam after the demise of the Baghdad caliphate in the thirteenth century to the rule of the Mamluks, soldiers of fortune who carved out kingdoms of their own and kept apart from the populations they ruled. Gone was the conti-nuity between the ruler and the ruled that had been the hallmark and the promise of the advent of nationalism. The autocrats were now feared and reviled. A distinguished liberal Egyptian formed in the liberal interwar years, the late scholar and diplomat Tahseen Basheer, said of these men that they became “country owners.”

The rulers grew older and obscenely wealthy, their populations younger and more impoverished. These autocrats in the national-security states put to shame the old monarchies in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the Emir-ates. In the monarchies and principalities there has always existed a “fit” between monarchs and princes, and their people. There has never been a cult of personality in these monarchies: the Stalinist cult that afflicted Sad-dam’s Iraq, Hafez Assad’s Syria, and Gadhafi’s Libya is abhorrent to them. The Bedouin ethos that still legitimizes the monarchies has no room for such deference to the ruler.

Monuments to kings are heresy to the Saudi rulers. The affection and concern displayed by ordinary Saudis for the ailing King Abdullah stands in sharp relief against the animus toward Mubarak and Ben Ali and Assad and Gadhafi. The Sabahs of Kuwait, the ruling family in that city-state since the mid-eighteenth century, inspire no fear in Kuwaitis; no “visitors at dawn” haul off Kuwaitis to prison, as is the norm in the republics of ter-ror. Before the age of oil, the Kuwaitis had been seafarers and pearl divers, and the Sabahs were the ones who stayed behind to look over the affairs of the place. They had respect and privilege, but there was no space for grand ambitions and pretensions. The merchants held their own and still do: the

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3 15

wealth of the merchant families is more than a match for the revenues of the Sabahs. Nor do the other principalities differ in this regard. State ter-ror is alien to them.

Tiny Bahrain is something of an exception, afflicted as it is by a sec-tarian split between a Sunni ruling dynasty and a restive majority Shia population. But on the whole, the monarchies have always ruled with a lighter touch. Who in today’s republics of the whip and of state terror would not call back the monarchs of old? Nasab, or genealogy—inher-ited merit—is revered in the practice and life of the Arabs. It reassures people at the receiving end of power and hems in the mighty, connect-ing them to the deeds and reputations of their forefathers.

So three despots have fallen: Saddam Hussein in 2003; Ben Ali; and Mubarak. Saddam’s regime was of course decapitated by American arms. Ben Ali and Mubarak were brought to account by their own pop-ulations. This revolt is an Arab affair through and through. It caught the Pax Americana by surprise; no one in Tunis and Cairo and beyond was waiting on a green light from Washington. The Arab liberals were quick to read Barack Obama, and they gave up on him. They saw his comfort with the autocracies, his eagerness to “engage” and conciliate the dictators.

From afar, the “realists” tell the Arabs that they are playing with fire, that beyond the prison walls there is danger and chaos. Luckily for them, the Arabs pay no heed to these realists, and can recognize the “soft bigotry of low expectations” that animates them. Arabs have quit railing against powers beyond and infidels and foreign conspiracies. For now they are out making and claiming their own history.

Reprinted by permission of Newsweek. © 2011 The Newsweek/Daily Beast Company LLC. All rights reserved.

Available from the Hoover Press is Islamism and

the Future of the Christians of the Middle East, by

Habib C. Malik. To order, call 800.935.2882 or visit

www.hooverpress.org.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 316

An Unpredictable WindThe causes, the players, and the likely consequences of the Arab

eruptions. A conversation with Hoover fellows Peter Berkowitz, Victor

Davis Hanson, and Peter Robinson.

Peter robinson: In Tunisia a street vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi protested the harassment he had suffered at the hands of local police by committing suicide, setting himself ablaze. Shortly afterward, the govern-ments of Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, president of Tunisia for twenty-three years, and of Hosni Mubarak, president of Egypt for some thirty years, had been overthrown. A civil war broke out in Libya; the king of Jordan dismissed his cabinet; and protests took place in Bahrain, Yemen, Iraq, and Iran. How do we understand this?Victor DaVis Hanson: Well, there are two things going on. One is we live in an age of Facebook, Twitter, and the Internet, so something that would be local in Tunisia now resonates all over the world. And in the case of the Middle East, whether it is monarchy, theocracy, or military dictatorship, they all have one common denominator—they deny people

Peter Berkowitz is the Tad and Dianne Taube Senior Fellow at the Hoover

Institution, the chairman of Hoover’s Koret-Taube Task Force on National

Security and Law, and co-chairman of Hoover’s Boyd and Jill Smith Task Force

on Virtues of a Free Society. Victor DaVis Hanson is the Martin and Illie

Anderson Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution. Peter roBinson is the editor

of the Hoover Digest, the host of Uncommon Knowledge, and a research fellow

at the Hoover Institution.

DEMOCRACY IN THE ARAB WORLD

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3 17

freedom, they have ruined the economy, and they have stolen from the people. There has been this seething anger, and in some part the demon-stration of democracy in Iraq was the model. What would have been a local prairie fire has turned into a conflagration.robinson: Contrast what is taking place in the Arab world in 2011 with the Velvet Revolution, the anti-communist revolution that swept Eastern Europe in 1989.

Peter berkowitz: For one thing, in the Arab world you have the impact of Islam, which of course we did not have in the European revolutions. And we really do not know what the consequence is going to be. One of the important developments in recent months that you left out is that Hezbollah has taken over the government of Lebanon, ousting pro-West-ern Prime Minister Saad Hariri and installing what looks to be a Hez-bollah puppet who is certainly good friends with the Syrians. This is a tremendous threat to freedom. What you had in Europe was a clear and definite overthrowing of the alternative to Western-style liberal democra-cy and a clear determination to embrace Western-style liberal democracy. What we see in the Arab Middle East is a definite determination to get rid of authoritarian dictators, partly because people are living in grinding poverty. What we don’t know in this case is what the people want.robinson: Let us stay with Egypt for a moment because it is overwhelm-ingly the largest in population, historically the center of the Arab world, cultural center of the Arab world. The historian Bernard Lewis noted in a recent interview that the Arab world has no history of democracy. Thirteen hundred years of Islam in the Arab world has produced zero democracies except for the 1970s in Lebanon, and the Christian minority played a central role in that brief democracy. All right, Bernard Lewis: “In Egypt, the religious parties have an immediate advantage. First, they have a network of communication through the preacher and the mosque which no other political tendency can hope to equal. Second, they use familiar

“Here we have a potpourri of Iranian theocracy, Libya’s crazy

authoritarianism, Mubarak’s pro-American military dictatorship,

the Baath Party in Syria.”

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 318

language; the language of Western democracies is for the most part newly translated and not intelligible to the great masses. In genuinely fair and free elections, the Muslim parties are likely to win, and I think that would be a disaster.” What is going to happen in Egypt?

Hanson: I do not think we know, but we have a lot of paradoxes that are going on in the region. One is that these odious dictators like Mubarak tend to be more liberal in classical terms than the population. So if we were to have a plebiscite, the people might reflect a level of religious intolerance, anti-Semitism, anti-Americanism, and oppression against women that would not be true of the Mubarak government, despite its horrific human rights record. Another paradox we have in the region is that, unlike Eastern Europe, where they were rebelling against monolithic communism, here we have a potpourri of Iranian theocracy, Libya’s crazy authoritarianism, Mubarak’s pro-American military dictatorship, the Baath Party in Syria.

TWITTER TO FREEDOMrobinson: One of the principal figures in the Egyptian revolution was a young Egyptian Google executive. Protesters throughout the Arab world have been in touch on Twitter, they are keeping in touch by e-mail, they are posting events on YouTube. Is what has taken place conceivable with-out high tech? Is the political revolution we are witnessing now conceiv-able absent the high-tech revolution of the past decade and a half or so, the communications revolution?Hanson: I do not think so, but I think we are seeing the veneer of the revolution. I think that the radical Islamists know about social networking and electronic information and so does the Westernized upper and smaller middle class. They galvanize people. But to the degree that somebody who is a peasant farmer in a village on the Nile is getting up every morning and looking at Twitter, I am dubious that that is happening. So what I am suggesting is that they cause the initial revolt. They got rid of Mubarak

“The Muslim Brotherhood, the forces of radical Islam, they not only know

how to use [social media], they are using them very effectively even as

we speak.”

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3 19

and now the social networking may or may not be effective. What is going to capture the majority are the mosques and state-run television, people getting a little bit more mundane messages who do not participate. Every-body in Washington and New York and at Harvard and Yale, they do Twitter and Facebook, but people out in Fresno or working in a factory are not tweeting every day.berkowitz: The rise of the Internet, e-mail, and social networking is very much a double-edged sword. In this country the great beneficiary in the 2008 election was Obama, whose campaign expertly used social network-ing. In the past two years the real beneficiary of the new technology has been the tea party movement. This is neutral, it is a double-edged sword, and just as Victor says, the Muslim Brotherhood, the forces of radical Islam, they not only know how to use them, they are using them very effectively even as we speak.

Hanson: Just an accelerator, a catalyst . . . so all these movements might have happened, but they are happening at lightning speed now. robinson: We know that one of the aims of at least some branches of the radical Islamic movement is a restoration of the caliphate. They are talk-ing about something like what you can glimpse most recently in 1918, before the fall of the Ottoman Empire. And what you see when you look at a map is all kinds of places that we now think of as nations simply did not exist. Iraq was not there; Lebanon was not there; Israel was not there; Egypt was not. It was an undistinguished region. All right, so the question is: does the new communications technology tend to play into this dream of a restoration of somehow transcending or eliminating the nation-state, which is an artifact of the twentieth century, and play into the dream of a pan-Arab movement?berkowitz: For sure. Just as Western progressive liberal internationalists are delighted by the rise of the Internet because they think it helps lay the foundations for a one-state world and global governance. There is some reason for that.

“I do not see a monolithic Muslim nation appearing because it is no more

monolithic than the European Union, and the EU is shattering as we speak.”

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 320

robinson: It does tend to act as a solvent of the nation-state.berkowitz: By the way, just as Marx said in The Communist Manifesto that the rise of the telegraph helped lay the foundations for universal revo-lution of the proletariat, so too the radical Islamists certainly use this tech-nology in the hope that it is laying a foundation.

By the way, with the caliphate we can be even more precise. The caliph-ate means a single government under Islam, under all territories that have previously been held by Islam. In other words, stretching from Spain in the west to somewhere beyond Iran in the east. One government, and it is a Muslim government. That is what the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt is committed to.robinson: The New York Times in February: “Officials responded with a mass show of force across China. After anonymous calls for protesters to stage a Chinese Jasmine Revolution went out over social media and microblogging outlets, the words Jasmine Revolution, borrowed from the successful Tunisian revolt, were blocked on sites similar to Twitter and Internet search engines. In recent days, more than a dozen lawyers and rights activists have been rounded up and more than eighty dissidents have reportedly been placed under varying forms of house arrest.” Why do all three of us know that the Chinese won’t let it happen?Hanson: Because they are willing to use a level of coercion that essentially says to the West: “We do not really care what you say, you have no influ-ence over us, and if I could be blunt, you are borrowing a trillion dollars for health care when 400 million of us have never seen a Western doctor. So do not give us any lectures because you have no influence over us.” I would say, though, on your interest about the caliphate, I do not see a monolithic Muslim nation appearing because it is no more monolithic than the European Union, and the EU is shattering as we speak. The idea that Canada and the United States and Britain are going to have an Anglosphere again is ridiculous. There are so many fissures within the Arab world: Shiite, Sunni, Alawite, tribal, geographical, economic sys-tems. And remember, for all of the PC anti-Americanism, Saddam Hus-sein and Khomeini—and throw in Hafez Assad and Libya—have killed more of their own people than we did in Iraq in the first Gulf War trying to liberate them.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3 21

berkowitz: If I may say so, I think that Victor is right; the likelihood of a caliphate emerging is extremely remote. However, it is a real aspiration for lots of people and lots of leaders, and it is reasonable to worry that there will be a great deal of death and destruction as these people unsuccessfully seek to bring about a caliphate.

Illus

tratio

n by

Tay

lor J

ones

for t

he H

oove

r Dig

est.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 322

ISRAELrobinson: What is the thinking in Israel about the meaning of this Arab revolution for Israel?berkowitz: Needless to say, the Israelis are very concerned. The wisest among the Israelis made clear that when people cry out for freedom and democracy, Israel should stand with them. But they also made clear, con-cerning the people in Egypt, that’s a long-term aspiration, and the path to freedom and democracy might be very bumpy for the Egyptians and very dangerous for the Israelis. In terms of actual threats, the Israelis don’t fear conventional warfare. robinson: Tanks are not going to roll across the Sinai.

berkowitz: They are not going to roll across the Sinai; it is a long way across the desert and those tanks are extremely vulnerable to the Israeli air force. So that is not a short-term or intermediate-term threat. What is the near-term threat is even worse security in the Sinai Peninsula than the security provided by Hosni Mubarak’s regime. There are now mis-siles in the Hamas-controlled Gaza Strip, and they are real missiles, not crummy rockets, which can reach Tel Aviv and kill hundreds of thousands of people. Every single armament in the Gaza Strip got there from Iran through the Sinai Peninsula, smuggled in, illegally with the help of Bed-ouins, maybe Egyptian forces were bribed. If this security breaks down even more, this is a tremendously significant threat to Israel. Moreover, it is not just Gaza; Israel shares a long border on the Sinai Peninsula. There is no force there, no security barrier there. There is a very serious threat of greater infiltration through the Sinai Peninsula into Israel; it is very worri-some from the Israeli point of view.robinson: Over the last decade roughly—correct my timing—as best I can tell there have been two big trends in Israel. One is tremendous economic buoyancy. That is a happening place: lots of high technology, levels of education, the sense of simply leading a good life is everywhere

“They need to go back and reset the ‘reset diplomacy’ and have a

principled position that is not contingent on individual countries or

personalities.”

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3 23

to be seen. Trend two—things have gotten more and more dangerous. Iran in pursuit of nuclear weapons under a leader who has spoken open-ly about driving Israel into the sea; the Turkish government becoming more Islamic and supporting that fleet of civilian ships that attempted to break the Gaza blockade; the victory of Hezbollah in Lebanon; unrest and uncertainty in Egypt. The two Arab countries that have made peace—Egypt, government overturned; Jordan, king under pressure. Just looking at it objectively, doesn’t one have the sense that the existential moment is approaching? How does Israel cope with that? berkowitz: I wish I could tell you how they cope with that, where they find the fortitude. Of course there is a kind of schizophrenia in Israel. And your description is absolutely right. Extraordinary prosperity: the greater Tel Aviv area has become one of the great Mediterranean beach towns. At the same time, you hear a term among national-security people and ordi-nary citizens that I did not hear before, and that is, I am speaking about Iran, a threat to our very existence, an existential threat. All the previous wars, with the exception of the war of independence, were fought outside Israel, very close to Israel, but urban areas were not targeted. What is going to be different, and it already began to be different with the 2006 second Lebanon war, is that all the enemies you mentioned have interme-diate-range missiles that will reach Tel Aviv. They will do terrible damage.

THE UNITED STATES AND THE ARAB MOMENTrobinson: Historian Niall Ferguson on the Egyptian situation as it was unfolding: “President Obama faced stark alternatives. He could lend his support to the youthful revolutionaries or he could do nothing and let the forces of reaction prevail. He did both, some days exhorting Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak to leave, other days drawing back and recom-mending an orderly transition. The result has been a foreign policy deba-cle. The president has alienated everybody, not only Mubarak’s cronies in the military, but also the youthful crowds in the streets of Cairo, and America’s two closest friends in the region, Israel and Saudi Arabia, are both disgusted.” He is going over the top a little, don’t you think?Hanson: No, I don’t. I agree with him, because he carefully—as a lot of us did—collated what Joe Biden, Barack Obama, and Hillary Clinton

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 324

said over an eighteen-day period . . . how they addressed the Egyptian situation and the relative silence about Libya. And he’s also collating what happened in Iran in 2009 (the sermon about meddling in internal affairs), the silence about Syria, and then some gratuitous remarks about Tunisia. And you put it all together and one wants to know: is the United States pressuring governments that are autocratic? Kind of, sort of, but not until they think that the demonstration is going to succeed. Do they have a principle of support for human rights, democracy, constitutional-ity, legality, an independent judiciary? Can’t see it. We don’t have any broad principles that we apply to everybody. So what is the policy now? The policy is this: if there is a monarchy, a theocracy, a military dictator-ship, or a brutal, savage Baathist, or whatever they are, and their people revolt against them, we [hold our finger up in the wind] and we wait, and we try to see what are the chances that the people in the street are going to prevail. And at some critical mass when they prevail, then we are going to go back and support them and then retroactively we are going to say we always did say that we supported you. And if they look like they are going to fail or they are quiet, then we back off and say we want to transition it quietly.

Then there is one other policy, and this is why Niall Ferguson is so upset. If you say that you cannot meddle in Iranian affairs and if you say that this horrific regime in Syria we have to reach out to as we did not in the Bush administration, and if you do not say anything about utter sav-agery in the streets of Libya, but you do say that you think that Mubarak and the Tunisians and the Jordanians have to reform, then what you are essentially saying, whether you meant to or not, is to the degree that you do not like the United States, you butcher lots of people, and you keep the press from watching it, we are indifferent; perhaps we are even support-ive. To the degree that you like us, you bring in the cameras, and you are pretty soft about the way you put down unrest, then we’re going to be very angry at you. And it makes no sense. So they need to go back and reset the “reset diplomacy” and have a principled position that is not contingent on individual countries or personalities but is more abstract.robinson: You’re secretary of state—what should the American policy be?

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3 25

berkowitz: The American policy in my judgment should have been rooted in the great tradition that began with Harry Truman in 1947, in the wake of communist conquests in Eastern Europe. He said that it will be the policy of the United States government to promote the conditions of freedom everywhere around the world; a policy that was reaffirmed by Ronald Reagan in his great Westminster speech, in which he outlined the conditions under which freedom flourished, which had to do with a strong civil society and freedom of press, and an independent judiciary. It was then reaffirmed by George W. Bush in 2003 at his great NED speech when he announced the freedom agenda and became the first president to say that now the freedom agenda must focus on the Arab/Muslim world. That should have been our policy, but the Obama administration has systematically distanced itself from the freedom agenda.

robinson: Worth noting that the first president you named was Harry Truman, a Democrat. This can be a bipartisan policy.berkowitz: You have an excellent point; it has bipartisan roots.robinson: Last question, a hard one I think. Two quotations. First, polit-ical scientist Paul Rahe: “I believe we are witnessing a strategic shift in the Mediterranean. The younger generation of Arabs is turning to the only cultural force that has purchase in the post–Cold War world; they are turning to Islam. Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Jordan, Bahrain will become more hostile to us, to our European allies, and of course to Israel.” Quota-tion two, Natan Sharansky: “The democracy that hates you is better than the dictator who loves you.” Who is right?Hanson: Well, it is a little bit more complex because we have two theo-cratic regimes that give everybody as much Islam as they can handle. One of them is the Sunni version in Saudi Arabia, and one is the Shi-ite version in Iran, and neither one of them is popular. And there are people protesting both because they are authoritarian and corrupt and they do not see life as so good under the Quran. So, what we are trying

“Everybody realizes this is the Arabs’ moment. This is grass roots; the

world is watching. . . . We will see what the aspirations of the Arab

people are.”

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 326

to figure out is how do you warn people who are throwing out military dictatorships and secular strongmen and say to them, this is the path to consensuality, because if you really want the Muslim Brotherhood and you want theocracy, you have two good examples—Saudi Arabia and Iran—and the people there are not happy. So I think that this is the Arabs’ moment.

I just would finish by saying for fifty years we have been told by the Arab street and its intellectuals, especially in Europe, that “they brought the Baathists to us, they put Nazis into us, they brought the Soviet-style paradigm, they brought the corrupt American dictatorship. All these -isms and -ologies were forced on us and we did not have any choice.” You go to Libya and somebody will tell you, “You put Gadhafi on”; somebody will tell you, “You put Khomeini on.” robinson: That persistent sense of victimhood. Hanson: Exactly. Now everybody realizes this is the Arabs’ moment. This is grass roots; the world is watching. You guys don’t have to put theocracy, monarchy . . . it is yours. And we will see what the aspirations of the Arab people are. Because everybody is staying out of it, and it is up to them to make a government that reflects what the people want, and we will see what the people want.berkowitz: Neither Sharansky nor Rahe is right, but there is a kernel of truth in each. You need to put them together. There are two forces that have purchase on people’s souls in the contemporary Middle East. One force, as Paul Rahe says, is Islam. But the other force is a real force, it also has purchase on people’s souls, it is what Natan Sharansky writes about: the spirit of democracy, the desire to be free, the desire to live under laws that you yourself have a hand in making, to call the shots for yourself. The question is which of these two is going to be the victor. We don’t know which is going to be the victor; therefore, we should pursue things in the spirit of Truman, Reagan, and Bush, and what we should work on is not in the first place getting elections up and running, whose results can be not just uncertain but quite hostile to our interests and to international interests. What we should work on is promoting with care, caution, and judiciousness the conditions under which freedom flourishes. That means helping people who want freedom to build independent judiciaries,

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3 27

expand the freedoms of the press, create economic opportunity, and cer-tainly not least, improve the opportunities for girls to be educated and for the protection of women’s rights. That’s what we can do to make things better.

Excerpted from Hoover’s webcast series, Uncommon Knowledge (www.hoover.org/multimedia/uncommon-knowledge). © 2011 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved.

Available from the Hoover Press is Torn Country: Turkey

between Secularism and Islamism, by Zeyno Baran. To

order, call 800.935.2882 or visit www.hooverpress.org.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 328

Peter Berkowitz is the Tad and Dianne Taube Senior Fellow at the Hoover

Institution, the chairman of Hoover’s Koret-Taube Task Force on National

Security and Law, and co-chairman of Hoover’s Boyd and Jill Smith Task Force

on Virtues of a Free Society.

The Roots of a Freedom AgendaThe Arab struggles may be new, but American goals are not. Three

recent presidents laid the groundwork. By Peter Berkowitz.

What is genuine democracy? What are its foundations, and which beliefs, practices, and associations nourish it? It’s a pressing question for the United States, whose experts were caught flat-footed by the popu-lar uprisings sweeping the Arab world and whose intelligence agen-cies, Defense Department, State Department, and National Security Council remain woefully understaffed with officials who know Arabic and understand Islam. We need to understand what is within the com-petence and commitment of the United States to bring about genuine democracy.

When Muammar Gadhafi threatened to use his armed forces to gun down antigovernment protesters across the country, President Obama at first seemed tongue-tied—at a loss for a clear view of America’s interests in the Libyan uprising and the obligations imposed by American ideals. Yet weeks earlier, his tongue had been freer and his vision clearer. Shortly after Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak resigned and transferred his powers to the military, Obama declared that “nothing less than genuine democracy will carry the day.”

DEMOCRACY IN THE ARAB WORLD

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3 29

Genuine democracy, he explained, “means protecting the rights of Egypt’s citizens, lifting the emergency law, revising the constitution and other laws to make this change irreversible, and laying out a clear path to elections that are fair and free.” And it must be inclusive: “Above all, this transition must bring all of Egypt’s voices to the table.”

Such enthusiastic demands were an understandable reaction to the stir-ring images broadcast around the world from Cairo. It was right and fit-ting for the president to stand with those demanding an end to authori-tarianism and a voice in the making of the laws under which they live. Nevertheless, his rhetoric risked inflating expectations and confusing pri-orities. With the ground continuing to shift in the Arab world—NATO intervention in the Libyan civil war, the return of influential radical Sunni Sheik Yusuf al-Qaradawi to Egypt, the persistent demonstrations in Bah-rain, Syria, and elsewhere—it’s critical to establish reasonable expectations and clear goals.

Our own constitutional tradition, while uncompromisingly grounding government in the consent of the governed, maintains a lively awareness of the tyranny of the majority. That’s why the founders built into the Con-stitution substantial limits on government. And that’s why our constitu-tional tradition teaches that democracy is not the highest aim of politics, but rather the regime best suited to securing individual freedom for all. This is the leading goal of legitimate and lawful government.

Free elections are sometimes not enough to reach that goal. For exam-ple, within eighteen months of its victory in the January 2006 Gaza elec-tions determinedly sought by Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, Hamas staged a bloody coup in which it threw out the rival Fatah movement and forcibly imposed one-party rule. And earlier this year, even as the people of Tunisia and Egypt banished their dictators, Hezbollah dealt a serious blow to the prospects for freedom in Lebanon and stability in the region by unseating a pro-Western prime minister, Saad Hariri, and replacing him with Hezbollah puppet Najib Mikati.

Among modern presidents, Harry Truman, Ronald Reagan, and George W.

Bush were the most consequential advocates for this defining principle.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 330

The powerful waves of discontent washing over the Middle East will continue to oblige the White House to focus on long-suppressed Arab demands to determine their own destinies. Meantime, Obama and his team can draw inspiration and guidance from three Oval Office forebears: Harry Truman, Ronald Reagan, and George W. Bush. They are the most consequential advocates among modern presidents for the preservation and extension of democracy and freedom abroad as a defining principle of American foreign policy.

On March 12, 1947, with communism on the march, imposing totali-tarian government throughout Eastern Europe, and with Greece and Tur-key tottering, Truman addressed a joint session of Congress. Communist aggression, the president declared, had forced the free world into a global struggle between “alternative ways of life.”

In response, Truman announced the doctrine to which his name became attached: “One of the primary objectives of the foreign policy of the United States is the creation of conditions in which we and other nations will be able to work out a way of life free from coercion.” America should concentrate on creating the material conditions of freedom, which meant providing “economic and financial aid which is essential to eco-nomic stability and orderly political processes.”

Reagan took up the baton more than three decades later. On June 8, 1982, with intellectual and political elites on the left believing that Western liberal democracies had much to learn from communism about social jus-tice and not a few on the right thinking that in world affairs America should mind its own business, Reagan addressed members of the British Parlia-ment to warn of “threats now to our freedom, indeed to our very existence, that other generations could never even have imagined.” Prominent among them were “global war” in which the use of nuclear weapons “could mean, if not the extinction of mankind, then surely the end of civilization as we know it,” and “the enormous power of the modern state” which, readily abused, worked “to stifle individual excellence and personal freedom.”

President George W. Bush insisted that Middle East freedom must be

“a focus of American policy for decades to come.”

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3 31

To defeat these novel threats to freedom, Reagan announced a long-term undertaking “to foster the infrastructure of democracy, the system of a free press, unions, political parties, and universities, which allows a people to choose their own way to develop their own culture, to rec-oncile their own differences through peaceful means.” Out of this man-date, which broadened Truman’s understanding of the conditions under which freedom flourished and posed a task Reagan recognized would “long outlive our own generation,” was born the National Endowment for Democracy.

On November 6, 2003, to honor NED’s twentieth anniversary, George W. Bush, addressing the United States Chamber of Commerce in Wash-ington, D.C., became the first U.S. president to focus what he called “the freedom agenda”—an elaboration of the Truman doctrine and the prin-ciples Reagan expounded in his speech at Westminster—on the Muslim Middle East. His perspective, like that of Truman and Reagan, looked not merely to the moment but beyond the horizon. Securing and extending freedom in the Middle East, he insisted, must be “a focus of American policy for decades to come.”

The universal claims of human freedom do not dictate a single set of political institutions, Bush observed, but all democracies that protect free-dom, he insisted, must conform to certain “vital principles.” They must “limit the power of the state”; establish the “consistent and impartial rule of law”; “allow room for healthy civic institutions—for political parties and labor unions and independent newspapers and broadcast media”; “guarantee religious liberty”; “privatize their economies, and secure the rights of property”; “prohibit and punish official corruption, and invest in the health and education of their people”; “recognize the rights of wom-en”; “and instead of directing hatred and resentment against others, suc-cessful societies appeal to the hopes of their own people.”

Truman, Reagan, and Bush were right.In proclaiming support for those demanding freedom and democracy

in Egypt, Obama aligned himself with a proud American foreign policy tradition with both progressive and conservative roots. He should claim that tradition as his own and reaffirm it. At the same time, and in the same spirit, the president should adopt a long-term perspective. In that

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 332

way he can contribute to the advancement of democracy abroad by recommitting America to the arduous, gradual, patient work of cultivat-ing the conditions—material, moral, and political—under which free-dom flourishes.

Reprinted from Peter Berkowitz’s blog (http://pajamasmedia.com/blog/author/peterberkowitz).

Available from the Hoover Press is Never a Matter of

Indifference: Sustaining Virtue in a Free Republic, edited

by Peter Berkowitz. To order, call 800.935.2882 or visit

www.hooverpress.org.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3 33

Stephen h. haber is the Peter and Helen Bing Senior Fellow at the Hoover

Institution; a member of Hoover’s John and Jean De Nault Task Force on

Property Rights, Freedom, and Prosperity; co-director of Hoover’s Project on

Commercializing Innovation; and the A. A. and Jeanne Welch Milligan Professor

in the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford University. Victor

Menaldo, a former W. Glenn Campbell and Rita Ricardo-Campbell National

Fellow at the Hoover Institution, is an assistant professor of political science at the

University of Washington, Seattle.

Lands of Little RainDrought may not be destiny, but a critical ingredient for democratic

societies does seem literally to fall from the skies. By Stephen H.

Haber and Victor Menaldo.

We wish we could say that democracy is coming to the Middle East and North Africa, but there are good reasons to curb our optimism. It is one thing to force a tyrant from the presidential palace. It is quite another to create a durable, democratic political system.

Popular uprisings continue to sweep the Middle East and North Afri-ca. Soon after the year began, Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, who had ruled Tunisia since 1987, and Hosni Mubarak, ruler of Egypt since 1981, were rapidly—and almost bloodlessly—forced out of power. The following months have witnessed protesters taking to the streets in Bahrain, Iran, Syria, and Yemen, and civil war erupting in Libya. In all these move-ments the participants demand democracy, an end to corruption, and economic opportunity.

The states that make up the Middle East and North Africa are among the world’s oldest, and since their creation they have persistently settled into

DEMOCRACY IN THE ARAB WORLD

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 334

patterns of autocratic rule. Egypt has been a territorial state since the first pharaoh in 3150 BC, but it has never once in five millennia experimented with democracy. The overthrow of the Alawiyya dynasty in 1952 did not produce a republic; it resulted in the dictatorship of Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Contrary to popular belief, present-day Iraq has been a recognizable political entity since Sargon of Akkad united the city-states of Mesopota-mia by conquest in the twenty-third century BC. Although the last Iraqi monarch was overthrown in 1958, he was eventually replaced by Saddam Hussein. Iran has been a state since the creation of the Persian empire in the sixth century BC. Its last monarch, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, was overthrown in 1979 but replaced by yet another autocrat, the Ayatol-lah Ruhollah Khomeini.

Syria also has a long history. Damascus, in fact, is one of the oldest continually inhabited cities on the planet. Even before Bashar Assad and his father, Hafez Assad, created the dynasty that has endured since 1970, Syria was governed by a succession of tyrants. When King Idris of Libya was overthrown in 1969, Muammar Gadhafi came to power. Yemen, too, deposed its monarch in 1962, but he was replaced by the brutal dictator-ship of Ali Abdullah Saleh.

Why is autocracy so persistent in this part of the world? Some pundits suspect the region’s oil wealth is the cause. Yet the countries of the Middle East and North Africa were autocracies for centuries before they found oil; moreover, some of them, like Bahrain and Libya, have lots of oil, while others, such as Yemen and Egypt, barely have any.

Others suggest Islam. Yet Indonesia, which has the world’s largest Mus-lim population, has become a democracy. Moreover, many of the persis-tent autocracies of the Middle East and North Africa—most notably Iran, Iraq, and Egypt—antedate Islam by more than a millennium.

We see a clue in the protesters’ demands for both democracy and economic opportunity. Briefly stated, societies characterized by extreme inequality tend not to provide fertile ground for representative political institutions. Not surprising, the first democracies—both in antiquity and in the modern era—emerged out of societies whose citizens not only had attained high average levels of education but were relatively equally matched in education and sophistication.

© X

inhu

a/Zh

ang

Nin

g

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3 35

Colonial New England is the archetype: a society of highly literate family farmers. What was true about New England was also true about ancient Athens, seventeenth-century Holland, eighteenth-century Eng-land, and nineteenth-century Canada. By the standards of the time, they had social structures with a sizable middle class. There is a good reason why democratic political systems tend to flourish in these kinds of societies: any incentive to rip the society apart to redistribute wealth is weak.

Such is not the case in societies where income, education, and oppor-tunity are concentrated in a tiny elite. There, “free and fair elections” become a way for the poor to redistribute wealth. Indeed, there is little to stop the vast, impoverished majority from stopping at wealth; why not deny the elite life and liberty as well?

The huge Merowe Dam in Sudan is part of a centuries-long effort to tame the Nile River.

Save for valleys fed by rivers like the Nile, agriculture is virtually impossible in countries of

the Middle East and North Africa, which are among the driest places on earth. From ancient

times to the present, access to irrigation has been a natural candidate for concentrated

ownership and a barrier to democracy.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 336

ROOTS OF INEQUAL ITYReaders may wonder why new, democratic governments cannot simply remake social structures, such that populist calls for redistribution fail to find a large audience. They may also wonder why the Middle East and North Africa have such inegalitarian social structures in the first place.

Research we are conducting into the long-run determinants of demo-cratic and autocratic political systems suggests that social structures are the outcomes of long historical processes; they are not created by the stroke of a pen. Our research also suggests that those processes originate in the basic organization of the economy—not just now, but over the course of an economy’s long history.

Here is a brief description. The world’s first and most long-lived democracies were built out of societies of family farmers growing grains and legumes. Such societies gravitated toward family farms because grains and legumes are characterized by modest-scale economies in production. These foods can also be stored almost indefinitely; a society built upon them can generate an economic surplus. Finally, they can be grown using rain-fed methods of production. This last point is crucial: because there is no need to obtain access to an irrigation system, the right to water can neither serve as a barrier to entry nor increase the minimum efficient scale of production. The optimal scale of production is the family farm.

A glance at a world precipitation map quickly reveals why the coun-tries of the Middle East and North Africa have social structures that are not conducive to democracy: they are among the driest places on earth. Except in a few very narrow strips along the Mediterranean, and the river valleys of the Tigris, the Euphrates, and the Nile, agriculture is virtually impossible. As a result, these societies did not evolve out of family farm-ers who accumulated surpluses that could fuel a long-run process of eco-nomic growth, investment in education, and democratization.

Instead, they were populated by tribal, nomadic peoples, such as the Bedouins of the Arabian Peninsula or the Berbers of North Africa, whose economic raison d’etre was to provide long-distance transport across the desert. Grain agriculture was possible only in a few places where a river like the Nile could be harnessed. The economies of scale and barriers to entry imposed by the need to obtain property rights to water gave rise to

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3 37

societies composed of a wealthy elite and a vast, impoverished peasantry. No one owns the rain, but access to irrigation is a natural candidate for concentrated ownership.

A S INGLE EXCEPT IONA simple exercise helps support our hypothesis. The Middle East and North Africa are part of a much vaster area of low precipitation, the Afro-Asian Dry Belt, which extends from Mauritania (on Africa’s Atlantic Coast) eastward across Mali, Niger, Chad, and Sudan, and northwards across Morocco, Algeria, Libya, Tunisia, and Egypt. It then continues east-ward, encompassing all of the nations of the Middle East, Central Asia, Northwestern China, and Mongolia.

Across that vast stretch of the earth, encompassing a broad range of ethnicities, language groups, and colonial experiences, only one country has managed to sustain a democracy: Israel. As an exception it suggests the power of our rule: Israel broke the pattern by means of an immigrant population that brought its human capital along, allowing those immi-grants to transform deserts and briny marshes into farmland.

The observations of social scientists, unlike the inscriptions at Karnak and Luxor, are not written in stone. They do, however, provide a guide to the likely outcome of events in the Middle East. And they suggest that political science, not economics, is the true dismal science.

Reprinted from Defining Ideas (www.hoover.org/publications/defining-ideas). © 2011 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved.

Available from the Hoover Press is Political Institutions

and Economic Growth in Latin America: Essays in Policy,

History, and Political Economy, edited by Stephen

H. Haber. To order, call 800.935.2882 or visit www.

hooverpress.org.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 338

Colonel Joseph Felter (U.S. Army) is a research fellow at the Hoover

Institution. Brian Fishman is a counterterrorism research fellow at the New

America Foundation and a fellow at the Combating Terrorism Center at the U.S.

Military Academy.

The Enemies of Our EnemyWe may not yet know what to do about the Islamists fighting in Libya,

but we do know not to repeat certain mistakes. By Joseph Felter and

Brian Fishman.

In September 2007, U.S. soldiers raided a desert encampment outside the town of Sinjar in northwest Iraq, looking for insurgents. Amid the tents, they made a remarkable discovery: a trove of personnel files—more than seven hundred in all—detailing the origins of the foreign fighters Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) had brought into the country to fight against coalition forces.

The Sinjar records, which we analyzed extensively in a series of reports for the U.S. Military Academy at West Point’s Combating Terrorism Cen-ter, revealed that at least 111 Libyans had entered Iraq between August 2006 and August 2007. That was about 18 percent of AQI’s incoming fighters during that period, a contribution second only to Saudi Arabia’s (41 percent) and the highest number of fighters per capita of any country noted in the records.

Three and a half years later, the Libyan data in the Sinjar records have become a subject of renewed interest, for obvious reasons. We still have only a fuzzy idea of who the rebels fighting Muammar Gadhafi actually

DEMOCRACY IN THE ARAB WORLD

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3 39

are. On March 29, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton admitted that “we’re still getting to know those who are leading the Transitional National Council,” the rebels’ putative political organization. Gadhafi, meanwhile, insisted his rebel enemies are tied to Al-Qaeda, and both American critics and supporters of the international campaign have expressed concern that the old dictator might have a point.

In a congressional hearing in Washington on March 29, Senator James Inhofe pointedly questioned James Stavridis, NATO’s supreme allied commander for Europe, over “reports about the presence of Al-Qaeda among the rebels”; Stavridis replied that he believed the rebels were, in the main, “responsible men and women who are struggling against Gadhafi,” but that the military had “seen flickers of Al-Qaeda and Hezbollah.”

How should policy makers deal with this ambiguity? First and foremost, they should weigh the presence of jihadi-affiliated social networks in Libya, while realizing it would be unwise to exaggerate the threat based on the rela-tively limited evidence in the Sinjar records. And as the international com-munity pressures the Gadhafi regime, it should avoid policies that increase the likelihood that jihadi groups can capitalize on the chaos in Libya.

So what do we know about Libyan jihadists from the Sinjar records? Aside from the overall numbers, we know that the vast majority of Libyan fighters profiled in the documents hailed from northeastern Libya, where today’s rebellion is centered. Half of them came from Darnah, a town of eighty thousand on the Mediterranean coast that has played an active role in the rebellion; another quarter were from Benghazi, the heart of the cur-rent uprising. The Libyan fighters also seem to have arrived in Iraq over a short period of time, from March to August 2007. That abrupt surge sug-gests that tribal or religious networks were suddenly spurred to send fighters abroad. And those fighters seem to have been extremely dedicated. Most of the fighters entering Iraq registered their “work” upon arrival. Eighty-five percent of the Libyans in the Sinjar records registered as suicide bombers, a larger percentage than any other nationality other than Morocco.

That is good and bad news. On the one hand, it is disconcerting that social networks sympathetic to Al-Qaeda were able to mobilize a force of

In Libya, the enemies of our enemy may not be our friends.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 340

such size and determination in a matter of months; it suggests that they could do the same thing today. On the other hand, the fact that the surge was the work of a small number of distinct networks may indicate that sup-port for Al-Qaeda is concentrated in particular tribal, religious, or social communities, rather than dispersed throughout a broader swath of Libyan society.

That said, analyzing a complex society primarily through the lens of its most virulent elements is a dicey business. Libyans may have been dispropor-tionately represented among Iraq’s Islamist radicals, but that doesn’t mean that such radicals are disproportionately represented in the anti-Gadhafi rebellion. Reporting from the front lines of the current conflict indicates that the rebels reflect a complex cross-section of society. In short, there is little reason to believe that jihadists are poised to seize broad political control of Libya should the rebels come to power—though it is probably true that they will operate more overtly if relieved of Gadhafi’s iron-fisted rule.

The more likely scenario than a clean rebel victory, however, is also more dangerous: that either military stalemate or internal divisions among rebel groups will lead to a civil war in which a small jihadi faction can flourish amid lawless conditions. History shows us that even a small band of deter-mined extremists, if well led, armed, and equipped, can wreak havoc and challenge efforts to bring stability and order to a weakened state. Algeria suffered a decade of brutal civil war at the hands of extremists such as the Armed Islamic Group and its splinter faction, the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat. Other examples include the Abu Sayyaf group in the southern Philippines, Jemaah Islamiyah in Indonesia, and Islamist extremist groups that fuel the insurgency in Chechnya. And Al-Qaeda in Iraq still kills on a scale that would be deemed completely unacceptable in a country where the recent past had not been so tremendously violent.

Where would dangerous jihadi factions in Libya come from? In our original analysis of the Sinjar records, we suggested that the Libyan rebel recruitment pattern might indicate that networks related to the largely

Eighty-five percent of the Libyan jihadists who arrived in Iraq registered

as prospective suicide bombers. Only Moroccans had a higher figure.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3 41

defunct Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG), a jihadi organization pri-marily dedicated to overthrowing the Gadhafi regime, are still functional. This notion is bolstered by recent reports that former LIFG members fun-neled fighters to Iraq. After all, exiled LIFG members in South Asia joined Al-Qaeda officially in November 2007, aligning themselves with other senior Libyan jihadists already among the terrorist group’s ranks. But other scholars have questioned LIFG’s role, suggesting that such recruitment pat-terns are more likely the result of ad hoc tribal or mosque networks. Those explanations are not mutually exclusive, but it is worth noting that many of LIFG’s leaders, imprisoned in Libya by Gadhafi for years, renounced Al-Qaeda in 2009. Whether these individuals—or those potentially released in the future—will rekindle their old sympathies remains to be seen.

But though the Sinjar documents present more questions than answers about Libya’s rebels, they do suggest some ideas for how we might best respond to the country’s civil war and its aftermath. For one thing, there should be little doubt that the rebellion includes at least some jihadists sympathetic to Al-Qaeda. Those networks, however, are discrete from the broader rebellion, and would have existed with or without the no-fly zone now imposed by NATO forces. The challenge is to contain the ability of such troublemakers in the rebel coalition to capitalize on chaos—not with platitudes, but with pragmatism.

This is a tall order. A key problem is to identify the jihadi networks inside Libya and measure their strength within the broader rebel coalition. The Sinjar records offer a strong starting point, enabling intelligence agencies to ask good questions about such networks, but they alone do not provide sufficient answers. Undervaluing knowledge of the complexity of tribal and social networks proved disastrous when the United States first entered Iraq. An armed intervention in Libya of that intensity would be extraordinarily counterproductive, but the principle is still valid: NATO forces ignore the imperative to understand Libya’s social terrain at their own peril.

The international community can also leverage the most striking fea-ture of its intervention in Libya: the breadth of its diplomatic support. Keeping that coalition intact—particularly the Arab contingent—lim-its the resonance of Al-Qaeda’s persistent claim that the West is waging war on Muslims. The initial backing of the Arab League provided critical

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 342

political space for the United Nations and the coalition implementing the Libya no-fly zone. If the mission shifts toward a more aggressive effort to depose Gadhafi, public support from Arab states will be crucial.

The international community also is pondering how to aid the rebels, including whether to give them weapons. Doing so would offer obvious advantages, but these are outweighed by the risks, most notably that the weapons could find their way into less-friendly hands in the future. Gad-hafi’s weapons caches already pose a long-term threat not just to Libya but to other states in North Africa, including Tunisia and Egypt. Allied forces should not contribute to the problem.

The air campaign, while unlikely to depose Gadhafi on its own, has bought time for more creative means of rebel support that do not increase the danger of unintended consequences. If improving the rebels’ military capacity is necessary, the international community should continue to pro-vide training rather than weapons. Assisting insurgents is a classic form of unconventional warfare, and it does not necessarily mean putting Western personnel in Libya. The United States can help by facilitating rebel commu-nications and delivering virtual instruction on military basics. Training and advisory assistance to rebel leaders can be provided outside Libya’s borders (in a neighboring state, ideally) with support from other countries in the region.

The enemies of our enemy in Libya may not be our friends. But the danger that they pose to U.S. interests in the future will be determined in no small part by what the United States and its allies do in Libya today. Intervention is often a lose-lose situation. But the international commu-nity had better get used to that ambiguity sooner rather than later. In Yemen, Bahrain, and Syria, the choices will not get any easier.

Reprinted by permission of Foreign Policy (www.foreignpolicy.com) © 2011 The Slate Group LLC. All rights reserved.

Available from the Hoover Press is Skating on Stilts:

Why We Aren’t Stopping Tomorrow’s Terrorism, by

Stewart Baker. To order, call 800.935.2882 or visit

www.hooverpress.org.

Hoover Digest N 2011 · No. 3 43

William Ratliff is a research fellow at the Hoover Institution and the curator

of the Hoover Archives’ Americas Collection.

Tigers of a Different StripeAfter their revolutionary fever cools, Arabs will have work to do.

They could do worse than to emulate the booming Asian nations.

By William Ratliff.

It took only a few weeks for the “Arab spring” to oust or threaten several perennial strongmen and to leave authoritarian and proto-authoritarian leaders as far away as China and Nicaragua scrambling to fortify domes-tic security. The political tsunami that began in Tunisia and Egypt—and then washed over Libya, Yemen, Syria, and elsewhere—was precipitated by outspoken demonstrators demanding greater freedom, dignity, democ-racy, and better living conditions for the poor and repressed. Compelling objectives all, and goals endorsed by the five-part Arab Human Devel-opment Report (AHDR) sponsored by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) between 2002 and 2009. But they will not be easily realized.