Homer and deathb

-

Upload

brandy-stark -

Category

Art & Photos

-

view

351 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Homer and deathb

Title: Homeric Thought on Death and Existence in the Afterlife

Brandy Stark, PhDFeb. 25, 2012

Orestes with ghost of Clytemnestra

Abstract Abstract: Topics of the dead have been utilized with such efficiency

by writers of all eras who record their cultures’ encounters with their spectral pasts. The poems of Homer were written from an oral literature handed down over generations and transformed into folklore and legend. From these ideas, Homer created two major epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Though the epics focused on the lives and actions of heroes, they also contained strong elements of death. Emerging ideas on death and the afterlife derived from centuries of storytelling are found throughout the Homeric epics. Through these writings, Homer records the first Grecian concepts of the soul, Hades, and the spectral existence of the unhappy dead.

What happens after death? Pre-classical society inherited many inconsistent pictures of

the soul or self. Associated with the grave Shadows in Hades Breath that perished at death Reincarnation

What happens after death? Why the confusion? Disintegration of the Mycenaean civilization in the 12th

century BCE Greek Dark Ages (substantial changes) Combination of smaller areas into larger cities New ideas arrived with the waves of Doric and Northern

European immigrants who brought in seers, healers, and religious teachers

Sacred shrines and ancestral tombs were left behind; created the need for new understandings of death and the afterlife.

Homer Homer Ionia, Asia Minor

Part of trade routes “Melting-pot communities” formed with multiple dialects and

complex legends (Porter 17)

Iliad and Odyssey It was during this time that the Iliad and the Odyssey were

given their final forms Derived from a rich oral tradition Kept descriptions of objects and values from older traditions Homer draws from:

Legends: usually derived from true events from a prior time (War) Folktales, defined as fictional stories derived from the

surrounding culture (Hades, ghostly visitations)

Influences Homer’s characters are so powerful that they transcend into the

afterlife, making him the first Western author to enumerate about the post-life existence of the dead (Felton 1 – 2).

The Iliad is an act of war with men who constantly face immolation or who lose comrades to the ravages of battle; struggle to stay alive in hostile circumstances Patroclus Hector

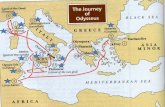

The Odyssey focuses on a man believed dead (Odysseus) who must come back from this status and prove himself. Often cited as falling into death-like sleeps Exhausted and lives a half life when imprisoned by goddesses Travels to the land of the dead

Death Death itself is not depicted as a pleasant

event to the Homeric Greeks. Thanatos, hard-hearted and a bringer of grief

and mourning; duty bound Unthinking, unstoppable, an end with out

reason or remorse Helpers: Hypnos, god of sleep, and Ker, the

personification of doom as found in tragic events (see: Sirens)

Artemis and Apollo: (Iliad) These twin gods have dual aspects and represent both life and death.

Apollo, acting as a god of death, attacks the Grecian camp with plague when one of his priests is offended Men, mules, horses, and dogs die Restitution to the priest ends death; Apollo

kills with cause He is reachable, reasonable and intelligent

(Thanatos is not)

Burial Immensely important as per Elpenor

(a sailor who died early in Odysseus’s voyage of a drunken fall). I beseech you but those you left

behind far away, by your wife and father who took care of you as a child, and by Telemachus, your only son whom you left at home in your palace, do not turn away and go back, leaving me unwept and unburied for future time, or I may become the cause of wrathful vengeance from the gods upon you. But burn my body with all the armor that I have and pull up a mound for me on the shore of the gray sea, the grave of an unfortunate man, so that posterity, too, may know me (Odyssey 23. 59 – 70).

Note: Revenge is from the gods, not the ghost

Burial If a body was lost effigies could be used as a substitute In special cases, it was enough to erect a tomb to honor the

dead and to offer sacrifice to his spirit. Telemachus is advised by Athena (in the disguise as Mentes)

that should he seek his father and learn that Odysseus died, he was to build a tomb in his father’s honor (Faraone, 183 – 184).

Burial

The Greeks had a strong belief that the dead continued to exist in the ground.

Corpse or cremains were buried with a feeding tube inserted into the tomb Allowed the living to provide liquid nourishment to the

departed. Regardless of one’s state as ash or corpse, the body-

spirit connection required a level of physical maintenance from the living (Dodds 179).

Irrational action for a rational people Some scholars believe that this custom was so old that

by the Homeric Era it was not questioned With the circulations of legends and lore supporting that

the unhappy dead could become a problem to the living, it was better to appease the spirits by feeding their earthly remains than to leave anything to chance (16).

Important items of daily use were often buried in tombs or burned through elaborate rituals in order to assist the living in the afterlife.

A few early ghost stories circulated of the unhappy dead who returned to complain of a lacking necessity.

Aspects of the soul Thumos: Not a part of the soul but is an organ of feeling and intuition A man could converse with his thumos Sometimes serves as the voice of reason: When to slay an enemy, or

offers advice on a course of action Guides the living into either rational or irrational actions See: Odysseus and Polyphemus

And I then formed a plan within my daring heart of closing on him, drawing my sharp sword from my thigh and stabbing him in the breast …. Yet second thoughts restrained me, for there we too faced utter ruin; for we could never with our hands have pushed from the lofty door the enormous stone which he had set against it. Thus then with sighs we awaited sacred dawn (Odyssey 9. 295 – 299).

Psyche The aspect of the soul in its more unified form as the well-

developed concept of the psyche belonging to later Greeks did not readily appear in Homer’s writings.

The psyche was granted at death, and its only function for the living was to leave him

See: Odysseus’s dead mother, Anticlea: O, my poor child, ill-fated beyond all men; Persephone, daughter

of Zeus, does not trick you at all; but this is the doom of mortals when they die, for no longer do sinews hold bones and flesh together, but the mighty power leaves our white bones and the soul, like a dream, flutters and flies away” (Odyssey 9, 186-190).

Homeric expansion on death Homer proposed that special souls survived death but that the human

shade was relegated to Hades, an actual land populated by ghosts. See: Hercules

Though a demi-god, Hercules could not fully escape the mortal’s fate in the underworld

“And next I marked the might of Hercules – his phantom form; for he himself is with the immortal gods reveling at their feasts, wed to fair-ankled Hebe, child of great Zeus and golden-sandaled Hera” [Book XI, Lines 599 - 601 ].

The greatest man from the prior generation of heroes still strolled through death’s gloomy gates and could only recount his earthly deeds, specifically his own journey to retrieve Cerberus from the Underworld, to Odysseus (Dodds, 179).

Homeric expansion on death Hades Known and feared: “And thus she spoke and my very soul was

crushed within me, and sitting on the bed I fell to weeping; my heart no longer cared to live and see the sunshine” (Odyssey 10. 499 – 501).

Any status gained in the world of the living was lost (queens in life, handmaidens in death)

Once deceased, the average person was merely a winsome spirit who remembered little of his life and who maintained no true purpose for existence: “The souls of the dead who had departed then swarmed up from Erebus:

young brides, unmarried boys, old men having suffered much, tender maidens whose hearts were new to sorrow, and many men wounded by bronze-tipped spears and wearing armor stained with blood. From one side and another they gathered about the pit in a multitude with frightening cries” (Odyssey 11. 33 – 36).

Homeric expansion on death Outstanding individuals: Hades did offer vague notions of

rewards The hero-hunter Orion spent his afterlife forever chasing the

animals he had killed in life. Minos

“There I saw Minos, the splendid son of Zeus, sitting with a gold scepter in his hand and pronouncing judgments for the dead, and they sitting and standing asked the king for his decisions within the wide gates of Hades’ house… (Odyssey 11. 563 – 566).

Homeric expansion on death Hades: punishment Tityus, a man who assaulted Leto, the consort of Zeus and

the mother of Apollo and Artemis, had his liver perpetually eaten

Parched Tantalus stood in a pool of water that splashed to his chin. Cursed with terrible thirst, each time he bent to drink the water it recessed.

And also I saw Sisyphus enduring hard sufferings as he pushed a huge stone…he kept shoving it up to the top of the hill. But, just when he was about to thrust it over the crest then its own weight forced it back and once again the pitiless stone rolled down the plain… (Odyssey book 11, lines 581-596).

Homeric expansion on death Achilles, the greatest of mortal

heroes, laments his fate in a manner reminiscent of Enkidu of the Gilgamesh:

“Do not speak to me soothingly about death, glorious Odysseus; I should prefer as a slave to serve another man, even if he had no property and little to live on, than to rule over all these dead who have done with life…” (Odyssey 11, 487-491).

Homeric ghosts Not only did Homer help to flesh out the underworld, he also worked

with the notion of the liminal state. The dead could produce ghosts capable of returning to the mortal coil

(no longer tied to the grave) Ghosts were “whining, impotent things of little use except when,

occasionally, they were called up to assist the living, usually by giving advice or information…no right thinking Greek was afraid of them…” (Finucane 5).

Both the Iliad and the Odyssey suggest that the poet was both fully conscious of this innovative idea and proud of the achievement. Until that time, the tendency of the dead was to be as part of the corpse (4).

Homeric ghosts The nature of the ancient Greek :

mindless, bodiless creature. Remain relatively unimportant,

forgetting themselves Non-essential ghosts, weak

…I drew my sword from my side and took my post and did not allow the strengthless [sic] spirits of the dead to come near the blood (Odyssey, 11.44 – 46)Living have power over the dead by will or material forceSword: Metal (disrupts supernatural powers in the ancient world), personal strength, death itself (Felton 10).

Homeric ghosts

Important when the Homeric poets are using them as a device through which to advance the story’s plot: Anticlea (mother): He discovers that she has died waiting for him to return,

but she also fills him in on the state of his country since his departure. Agamemnon revealed his murder to a stunned Odysseus, who last saw the

king leaving to return home, a victor of war. Tiresias is also unusual among shades because even post-mortem he retains

his intelligence as a gift from the gods. It is his advice that leads Odysseus to learn of his future and the course that he is destined to take.

Dream ghosts Big change: Not bound to underworld at all times Able to visit the living in the form of dreams As they retained a bodiless and boneless state, these dream-ghosts entered the

room through keyholes, particularly helpful as homes during the Homeric times often had neither chimneys nor windows.

Settled near the head of the sleeper to deliver its message Once done, it simply left. Living did not question this exchange (Miller 24). In sleep came to him the soul of unhappy Patroclus, his very image in stature

and wearing clothes like his, with his voice and those lovely eyes. The vision stood by his head and spoke” (Iliad 23. 85).

Achilles was unafraid of the shade and even tried to embrace him, though the result was that “the soul was gone like smoke into the earth, twittering” (Iliad 23. 124) (Similar to the Gilgamesh)

Conclusion In their quest for justification of death, the Ancient Greeks

created a variety of beliefs about death and the afterlife Introduced through the Homeric epics. The writings demonstrate a belief in the afterlife and in the idea

that the individual maintains an afterlife existence These ideas later developed into core values that were utilized

by later cultures who also sought to explore the otherworld These would be carried forth through the ideologies of the

Classical Greek cultures, the direct inheritors of the Homeric tradition.

Sources Dodds, E.R. The Greeks and the Irrational. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1959.

Faraone, Christopher A. “Binding and Burning the Forces of Evil: The Defensive Use of ‘VooDoo Dolls’ in Ancient Greece.” Classical Antiquity v. 10 (1991) 165 – 218.

Finucane, R.C. Ghosts: Appearances of the Dead and Cultural Transformation. New York: Prometheus Books, 1996.

Lenardon, Robert J. and Mark P.O. Morford.Classical Mythology.4thed. New York: Longman Press, 1971.

Miller, David D. “Angels, Ghosts and Dreams: The Dreams of Religion and the Religion of Dreams.” The Journal of Pastoral Counseling.26 (1991) 21 – 28.

Palmer, George H. (trans). The Odyssey of Homer. New York: Bantam Books, 1962.

Porter, Howard N. “Introduction.” The Odyssey of Homer. New York: Bantam Books, 1962. 1 – 17.

Rouse, W.H.D. (Trans). Homer: The Iliad. New York: Penguin Group, date unknown.

Russell, W.M.S. “Greek and Roman Ghosts.” The Folklore of Ghosts.Ed. Hilda R. Ellis Davidson. Great Britain: Cambridge, 1981. 192-213.

Sourcinou-Inwood, Christiane. “To Die and Enter the House of Hades: Homer, Before and After.” Mirrors of Mortality: Studies in the Social History of Death. Ed. Joachime Whaley. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1981. 15 – 29.

![Homer guardian (Homer, LA) 1888-12-21 [p ]](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/61c6f578fd763f663a306ab5/homer-guardian-homer-la-1888-12-21-p-.jpg)