Historic New England Summer 2008

-

Upload

historic-new-england -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Historic New England Summer 2008

HISTORICNEW ENGLAND

PRESENTED BY

THE SOCIETY FOR

THE PRESERVATION OF

NEW ENGLAND ANTIQUITIES

SUMMER 2008

PRESENTED BY

THE SOCIETY FOR

THE PRESERVATION OF

NEW ENGLAND ANTIQUITIES

SUMMER 2008

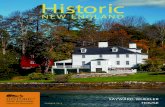

LANDMARKS OF THECOUNTRYSIDE

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:26 PM Page FC1

F R O M T H E C H A I R

I urge you to read Carl Nold’s thought-provoking essay on the challenges faced byhistoric house museums in the twenty-firstcentury. House museums need to find waysto be relevant, exciting, and able to com-pete for the public’s attention in a fracturedand media-hyped marketplace. Now thatCarl is serving as chair of the AmericanAssociation of Museums, he will be activelyinvolved in developing solutions to theseproblems nationwide. Historic New Englandis indeed fortunate to have at its helm aleader with his vision and experience.

Also in this issue, Richard Nylanderexamines the silhouette of the Appletonfamily and finds in its details a remarkabletrove of evidence—from works of art ondisplay to the textiles and furniture types—that tell us about taste among Boston’swell-to-do in the 1840s. The article reflectsthe profound understanding of NewEngland material culture that Richarddeveloped during his more than forty yearsat Historic New England. Although heretired in March, we are ever grateful forhis service and hope he will continue toshare his insights with us for years to come.

Let me remind our members to visit thehistoric house museums this season andenjoy the numerous eventsbeing offered all over theregion for everyone inter-ested in experiencing his-tory in ways that are bothenjoyable and authentic.

—Bill Hicks

OPEN HOUSE 1The Old Homestead

COLLECTIONS 2“In the Best Style”

MAKING FUN OF HISTORY 10Life on the Farm

LANDSCAPE 18Lost Gardens of New England

OBJECT STUDY 22In Mr. Appleton’s Parlor

NEWS: NEW ENGLAND & BEYOND 24

ACQUISITIONS 26Sacred and Profane

Except where noted, all historic photographs and ephemera are from

Historic New England’s Library and Archives.

The Future of the Historic House Museum 4

Landmarks of the Countryside 13

V I S I T U S O N L I N E AT w w w. H i s t o r i c N e w E n g l a n d . o r g

His t oricNEW ENGLAND

Summer 2008Vol. 9, No.1

Historic New England141 Cambridge StreetBoston MA 02114-2702(617) 227-3956

HISTORIC NEW ENGLAND magazine is a benefit of membership.To join Historic New England, please visit our website, HistoricNewEngland.org or call (617) 227-3957, ext.273. Comments? Please callNancy Curtis, editor, at (617) 227-3957, ext.235. Historic NewEngland is funded in part by the Institute of Museum and LibraryServices and the Massachusetts Cultural Council.

Executive Editor Editor DesignDiane Viera Nancy Curtis DeFrancis Carbone

COVER The timber-framed barn at Cogswell’s Grant, Essex, Massachusetts.David Bohl.

Tho

mas

Vis

ser

Dan

a Sa

lvo

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:26 PM Page FC2

1Summer 2008 Historic New England

O P E N H O U S E

n 1796, upon being ordained minister of theCongregational meetinghouse in Standish, Maine,Daniel Marrett and his bride, Mary, purchased a housethat would become home to three generations of their

family. The handsome Georgian house in the town center reflected Marrett’s status asa leading citizen in the community. The couple had six children before Mary died in1810; two years later, Marrett married Dorcas Hastings, who gave birth to eight chil-dren. While most members of the family’s sizeable second generation left Standishwhen they grew up, fond memories of the family home lingered in their minds. AsLorenzo Marrett wrote in 1842 to his younger sister Helen, still living at home,“though I may now be settled on a spot which I trust will bye and bye become a homeindeed to me, yet my thoughts will wander back to the old mansion house as long asyou and mother shall dwell there.”

Clearly, the Marretts had a deep attachment to their family home long before1889, when Daniel’s son Avery and his wife Elizabeth invited family members toreturn on August 15th to commemorate the old homestead’s centennial. Their cele-bration took place in the wake of America’s Centennial festivities, which hadunleashed a wave of interest in Colonial arts, architecture, and family history. TheMarretts’ Colonial lineage was likely a source of pride for family members, who cameto the celebration from as close as Portland and as far as Seattle. In the front yardstood an evergreen arch bearing the dates 1789–1889. Inside, the rooms were fes-tooned with pine branches, and some were redecorated forthe occasion. Frances, Avery and Elizabeth’s youngestdaughter, recited her poem:

Come hither, oh friends of the past and present!Come, and your early acquaintance renew.The old house stands eagerly waiting to greet youWith a welcome warm and true.The party continued with music and an elaborate lun-

cheon. Today, with rooms that have scarcely changed sincethe home’s centennial, Marrett House is a time capsulethat reflects the family’s reverence for their history.

—Jennifer Pustz Museum Historian

ABOVE Marrett House, Standish,

Maine, as it appeared during its

centennial celebration in August

1889. Each guest received a hand-

painted parchment souvenir with a

quotation about the love of home

printed inside. BELOW The sitting

room, decorated with greenery.

The wallpaper, still on the walls

today, may have been installed to

coincide with the celebration.

I

The OldHomestead

Marrett House open hours for 2008June 1 – October 15, 11 am – 4 pmfirst and third Saturdays of the month

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:26 PM Page 1

2 Historic New England Summer 2008

n his later years, Richard Codman(1842–1928) penned some recollec-tions of his childhood home inBoston. Although only ten when he

had to leave it after his father’s death in1852, Codman remembered the layoutof the rooms and some of the furnish-ings with remarkable clarity. He tells usthat the drawing room was on the sec-ond floor, and although “the room wasnot much used the door was always leftopen.” He describes the white marblemantel with caryatids and the gilt clockand pair of Sèvres vases on top of it;notes the statues on pedestals; andrelates that one window had been plas-tered over so the whole wall could behung with the paintings collected byhis father. “The furniture was of theEmpire period and covered with crim-son and gold satin, like the curtains.The carpet was an Aubusson rug andthere was a round marble top table in

the center of the room.”Richard’s father, Charles Russell

Codman (1784–1852), had purchasedthe house at 29 Chestnut Street in1817, and according to his accountbook, set about immediately to replacethe mantelpieces, paint and paper thewalls, carpet the floors, and order anew fence to enclose the yard. Afterthis initial flurry of activity, Codmanwaited seven years to order the furni-ture and lavish drapery that wouldcomplete the decoration of his drawingroom. In March of 1824 he wrote toSamuel Welles: “My dear Sir, In theright of an old friend I take the libertyto beg of you to execute a commissionfor me in Paris by which I hope to prof-it, not only by your own but of thetaste of Mrs. Welles.” Welles was aBoston merchant living in Paris, who in1811 had sent trend-setting furnishingsto his cousin John, thereby creating a

C O L L E C T I O N S

I

“In the best style”A recent acquisition sheds new light on elegance in Boston in the 1820s.

Dav

id C

arm

ack

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:26 PM Page 2

3Summer 2008 Historic New England

new standard among Boston’s elite. Codman enclosed a plan of the

bowed end of his drawing room andgave exact dimensions of its two largewindows, which measured five feetwide by ten feet three inches high each,“including the architrave.” He wantedthe valance to continue across the topof the mirror, like the drapery treat-ment depicted in the Appleton familysilhouette on page 22 of this issue.Codman’s final request was that Welleshave the articles “made for me in thebest style—rich but not gaudy.”

Although he was relying on thejudgment of a friend, Codman hadquite specific ideas about the colors forthe curtains and their trimmings, aswell as for the matching fabric withmedallions for the seats and backs ofsix chairs and two sofas. “The colorsof my carpet are Rose color and yellowand it is not very important which ofthese colors you select; I think howev-er that I should prefer the former. If theCurtains and Chairs are Rose color thefringes and lace and medallions for the

chairs and sofas should be of yellowand visa versa.”

Welles apparently could not findanything that matched Codman’s pref-erence for a yellow pattern on a rosecolored background, so Codman re- ceived just the opposite. The dominantcolor in his drawing room would beyellow, not the pink that was his firstchoice. It is not clear how long it tookthe Paris workrooms to complete thecommission or when the goods wereshipped to Boston. One wonders if theroom was finished by the time of Charles Russell’s marriage to AnneMacmaster on October 19, 1825. Wedo know, however, that it wasn’t untilApril 1827 that Codman paidthe Welles firm’s bill of$2257.91. Remarkably,this figure is almostthree times the amountCodman had spent atBoston auctions forseventeen Old Masterpaintings and only abouta third less than the purchase

price of the house itself.After Codman’s death, the con-

tents of his house were dispersed. Sixcurtain panels descended in the familyand were reused by Ogden Codman,Jr., who treasured anything that hadbelonged to his grandfather. Ogdenhad them remade and hung them inseveral of his residences, where theybecame quite faded and dirty. Recently,ten additional pieces of the valancewere discovered and acquired byHistoric New England. The remark-ably pristine condition of these exam-ples reveals the true elegance and bril-liance of Charles Russell Codman’spurchase of almost two centuries ago.

—Richard C. NylanderCurator Emeritus

LEFT Charles Russell

Codman’s Boston house.

Southworth & Hawes pho-

tograph, c. 1850.

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:26 PM Page 3

The Future of the

Historic House Museum

Dav

id C

arm

ack

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:26 PM Page 4

5Summer 2008 Historic New England

museum going is most often a social experience, done in pairs or larger groups, less frequently a solitary pastime. Anotherfactor is the changing availability of time for personal andleisure activities in the lives of American families. Increas-ingly, both parents work outside the home; shopping is nowavailable on previously blue-law-protected Sundays; and par-ents feel the need for childhood-enhancing soccer games orballet lessons, not to mention the time required for trans-porting children to them—all are identified as contributors toa reduction in time previously devoted to museum visits.

FACING PAGE To compete in the marketplace, tours must be lively

and engaging. Here, visitors learn about Federal-era entertaining at

the Otis House Museum, Boston. ABOVE LEFT Participants in

Historic New England’s Program in New England Studies tour the

collections storage facility and learn connoisseurship from experts

like Winterthur’s Prof. Brock Jobe. ABOVE RIGHT A group enjoys a

close-up look at selections from the extensive holdings in the

Library and Archives.

Historic New England explores ways to stay competitive

in a changing world…

a steady decline in attendance and public interest. Museumprofessionals point to a wide array of factors as the cause,ranging from pure demographics (fewer people in generationssince the Baby Boomers) to increased travel by families toexotic and distant destinations rather than station wagon visits to nearby attractions. Some suggest that replacing traditional history with social studies in the grade school curriculum has reduced overall knowledge and appreciationof the subject.

Others point to an overall shift from collective socialactivities such as bridge clubs, bowling or fraternal organiza-tions, to individual amusements like playing video games, listening to iPods, or surfing the Web. These new activities,done alone, divert people from museum visits. Further,

he evidence is mounting and clear:

for more than thirty years, most

history museums have experienced T

Bo

b St

egm

aier

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:27 PM Page 5

Historic New England Summer 20086

remember when Victorian furniture was thought to be of lit-tle interest. Constantly changing tastes bring paintings, col-ors, and design styles in and out of popular favor. We cannotwith any accuracy predict today what will in fifty years beessential to understanding our culture; we can only work topreserve representative examples of significant trends and letthe future determine their use and value. Historic NewEngland’s collecting has followed this approach from thebeginning, looking at the popular and unpopular, acquiringthe Gothic Revival Roseland Cottage before its interest wasfully recognized, and welcoming the gift of the 1938Modernist Gropius House, when some questioned whetheranyone would care about it. Today, Roseland Cottage andGropius House consistently stand in the top ranks of atten-

dance and interest among ourthirty-six museums. Ourduty to preserve extendsnot just to the popular buthas a goal of being broadly

representative of New Eng-land landscapes, buildings,

and collections over the longsweep of regional history.

While the preservation goalshould not depend on current

popular interest, the ability to carefor and use buildings and collec-

tions requires that we find waysfor the public to benefit fromtheir protected status. Museumsare no longer viewed simply as

repositories of the past; theymust fulfill a public purpose by

adding value in the communities they serve.For historic house museums, the potential value differs widelyby community and by site. Some historic houses serve asnational or international travel destinations, serving scholars,tourists and the general public, and bringing prestige anddollars to a location. Other historic sites are significant forlocal stories and, while important to those nearby, will neverattract tourism or much outside interest. Recognizing the dif-ferent needs of different communities, and that there is nosingle way in which museums add value, is a key to openthinking about how to use historic sites today.

In Dorchester, Massachusetts, Historic New England’sPierce House, built in 1683, is one of the region’s earliest sur-viving buildings. Its stories range across three hundred twenty-five years and are well documented by family archives. Thehouse is located in a densely populated area, but the needs ofthe community—which struggles economically and has limitededucational resources—do not support traditional museumprograms of hourly tours and promotion to tourists. Interest

The economic decline that followed the 9/11 tragedybrought to a turning point a crisis that was already brewingamong history museums and historic sites. In a confluence ofcircumstances, tourism came to an abrupt halt and museumattendance plummeted, endowments that provided operat-ing funds shrank in a stock market downfall; foundationsand individuals who supported museum activities wereequally forced to curtail contributions; and help from grantswas reduced as the economic decline lowered tax receipts atall levels of government. Museums already operating on thefinancial edge were severely impacted, and New England wasnot spared.

Response to such a crisis has required reexamination oflong-held assumptions. Across America museum trustees andfunders began to ask if historic house museums have afuture. Is the very idea of a building and contentsfrozen in time an outdated nineteenth-cen-tury phenomenon dating back topost-Civil War efforts to reinforcenational values by preserving the homes of Washington,Jefferson, and other greatmen? Does virtual access toimages and information viathe Internet render actualvisits to special places obso-lete? Do the increased em-phasis on math and scienceeducation and the need tosucceed in standardizedtests reduce opportunities totake children to historic placesfor enrichment activities? Does thenineteenth-century model of an hour-long guidedtour through a historic house have a place in twenty-first cen-tury life?

At Historic New England, these questions go to the heartof what we do. We work to tell the stories of New Englandheritage through the homes and possessions of those wholived here. Although our Library and Archives and our his-toric preservation efforts involve wider themes, our core col-lections of buildings, landscapes, and artifacts focus ondomestic life—the homes of New Englanders. The challengewe face is to find ways to engage people’s interest in theseresources and make them meaningful in contemporary life.

An essential purpose of a preservation organization ispurely that, preservation. A look at changing tastes over timequickly shows that buildings and collections once unpopularor deemed without merit can subsequently become the focusof study and be valued and preserved. In the early years ofthe twentieth century, photography was not considered suffi-ciently important for museums to collect. Many today still

Dav

idB

ohl

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:27 PM Page 6

7Summer 2008 Historic New England

in the house dwindled to the point that fewer than ten people per year visited it in the late 1990s.

In the last four years Historic New England transformedthe role of Pierce House and its value to the community bytaking a completely new approach to its use. While preserv-ing the original character of the site and retaining periodrooms that show what life was like, the active use of thehouse now revolves around school-age children. Children areasked to compare their own stories to those of the Piercefamily, to learn about their family’s roots, and describe theircurrent situations and experiences. They study the experi-ences of the Pierce family, whose lives are documented inmaterials that range from a letter by George Washington toelectric bills from the 1960s. The house serves as the base forprograms that go into the schools, and for expanding after-school programs. Family members accompany children forsome of the activities, which expands the reach of the muse-um beyond the newly-found young audience. Nearly 5,000students are now served from the house each year. HistoricNew England is now applying the same program model tohouses in Quincy, Massachusetts, and Lincoln, Rhode Island.

At Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm in Newbury, Mass-achusetts, a partnership was established in 2005 with the

Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty toAnimals. MSPCA had insufficient space at its own farm tohouse rescued animals. Historic New England welcomed theopportunity to return animals to our 317-year old farm, notonly to enhance its agricultural character but also to bringnew family and young audiences to experience one of ourmost significant sites. Attendance has steadily increased sincethe animals were installed. In Saunderstown, Rhode Island,Casey Farm hosts a Community Supported Agriculture pro-gram. The CSA enrolls 215 local member families, all ofwhom purchase a membership and contribute volunteer timein return for a weekly share of the farm’s organically raisedvegetables and flowers. Community sentiment in support ofthe farm is very strong, recognizing not only the personalstake of the member families but also the role the farm playsin continuing the centuries-old agricultural tradition in acommunity surrounded by rapid development.

Historic New England has increased emphasis on col-lecting and interpreting the twentieth century, and youngadult audiences are responding with increased interest. Itappears easier for twenty- and thirty-year-olds to connect toa past that included dial telephones and black-and-white tele-visions than to one that focused on open hearth cooking.

FACING PAGE A French-style bergère, c. 1869, from Codman Estate,

Lincoln, Massachusetts. ABOVE LEFT Gropius House, 1938, Lincoln,

Massachusetts. The Victorian chair and the Modernist house both

represent styles that at one time were considered not worth pre-

serving. ABOVE RIGHT Schoolchildren at Pierce House, Dorchester,

Massachusetts, the site of numerous educational activities.

Stev

e C

licqu

e

Dan

iel

Nys

tedt

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:27 PM Page 7

Historic New England Summer 20088

ABOVE LEFT Historic farms, like Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm,

Newbury, Massachusetts, and Casey Farm, Saunderstown, Rhode

Island (illustrated on table of contents page), are important com-

munity resources. ABOVE RIGHT Items from the recent past, like

this typewriter at the 1728 farmhouse, Cogswell’s Grant, Essex,

Massachusetts, can provide visitors with an entry point into more

Because the majority our sites have been preserved to depicthistory as a continuum, interpretation can be presented withmore accessible stories from more recent times. Doing so sug-gests a way to engage younger audiences through experiencescloser to their personal experiences, and then from that foun-dation, to build toward an increased interest in the more dis-tant past. Historic New England’s Modernist Weekend andvisits for the Young Friends to private homes of the mid-twentieth century illustrate this approach.

A side effect of the so-called “bowling alone” syndrome,in which individuals are increasingly replacing social engage-ment with solitary activities, is a heightened demand for sat-isfaction of specific, rather than general, interests and controlof personal time. The need to wait even ten or fifteen minutesfor an hourly tour is objectionable to many today, as is thefear of being trapped should a tour not prove satisfactory.While some find the tour with a knowledgeable guide to bethe very best experience one can have in a historic site, thereis much evidence that contemporary audiences want some-thing different. Visitors no longer wish to have a passive role,they want to experience a place hands-on, contribute theirown knowledge and insights, and have opportunities that gobeyond the usual. Many Historic New England sites now

offer cellar-to-attic tours that take guests to places previouslyoff limits. Overnight programs at the farms involve familygroups in doing farm chores and tending livestock. Travelprograms offer interaction with curators and with historichomeowners in other parts of the world. Evening and winterevents open the museums at times that are more suitable towhen visitors are seeking things to do. Such simple ideasappeal to audience groups that are unlikely to attend a stan-dard guided tour.

We are on the verge of the retirement of the BabyBoomer generation, those born between 1946 and 1964.While there has been much effort to attract the young to his-toric sites to build audiences for the future, museums arebeginning to recognize that there is a large potential audienceemerging in the Boomer retiree group. That generation is bettereducated, healthier, and more affluent than any prior genera-tion. Their life expectancy will allow for many years of pro-ductive activity. Their interest in history, beginning with theirown stories but expanding to larger themes, is growing withage. Some suggest that the group offers a base of interest andsupport that can be tapped for a new golden age for historichouse museums. What the retirees are likely to look for issocial interaction with people like themselves with shared

Dav

id C

arm

ach

Dav

id B

ohl

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:27 PM Page 8

9Summer 2008 Historic New England

interests and experiences. Museums, always a source ofsocial activities, have the opportunity to open their doors tosuch groups. In doing so, historic sites can also benefit fromthe expertise, personal connections, and willingness to helpthat are characteristic of such groups. The museums mustallow good access to facilities, collections, and staffresources, and offer experiences that are meaningful andenjoyable. Historic New England’s Appleton Circle alreadyoffers this kind of interaction among like-minded collectorsand cultural travelers.

Over the last three years, with dedicated efforts to recon-sider how we add value in the communities we serve,Historic New England has countered the trend of decliningattendance and support for history museums and achievedsteady increases in membership and attendance. Our experi-ence suggests that it is not the nineteenth-century model ofpreserving a historic place and its contents that is outmoded.Historic sites continue to offer wonderful opportunities forlearning, enjoyment, social interaction, and community ben-efit. They tell very personal stories that draw strong interest,and when done well, they also illustrate larger themes ofnational and regional history. What appears to be outmodedis the way we have standardized the historic site experience,

boxed it into a rigid tour, excluded the public from directinvolvement with the collections, and tried to impose a singlemodel on what are really very diverse places and constituen-cies. With continuing dedication to preservation and to thescholarship that helps us understand the past, historic sitemuseums must experiment with new ways to attract andserve audiences. Historic New England is committed to thisapproach, and recent results are very encouraging.

—Carl R. NoldPresident and CEO

Carl R. Nold has more than twenty years’ experience in the history

museum field. Formerly director of Mackinac State Historic Parks

in Michigan, one of the most-visited systems of history museums in

the nation, he currently serves as chairman of the American

Association of Museums.

remote time periods. ABOVE Historic New England organizes

trips for collectors and other specialized groups to choice loca-

tions here and abroad, with behind-the-scenes tours and visits to

private collections. This group enjoys a private tour of Philip

Johnson’s Glass House, New Canaan, Connecticut.

Stev

e C

licqu

e

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:27 PM Page 9

10 Historic New England Summer 2008

This is a tedder, or hay bob. As it moves, the wheels make thegears go around, and the gears turn long arms with forks on theends. The forks pick up cut hay in the field, turn it over, andspread it out to dry. The hay has to be thoroughly dry before thefarmer can make it into bales, which he then stores in the barn.

Hay is an important crop on farms with cows and horses, becausethat’s what they eat in winter when there’s no grass in the fields.

Before the horse-drawn mechanical tedder, farm workers turned thehay by hand with pitchforks or rakes. Today, most farms have tractorsto pull the tedder.

M A K I N G F U N O F H I S T O R Y

�

Life on a farm follows a familiar cyclebased on the seasons. Here is a year offarm work as recorded in the journal of Colonel Samuel Pierce of Dorchester,Massachusetts, in the eighteenth century.

JanuaryPut shoes on oxen

March Calves and lambs born

April Broke up ground for plantingSowed cabbages and barley

MayPlanted corn and beansDrove cows to pastureSheared sheepWeeded corn

What is this strange-looking contraption?

Life on the Farm

do you know �

Do you think you’d like to work on a farm?

During Colonial times,farming was one of themost common occupationsin the region, and entirefamilies worked hard toproduce food and othergoods for themselves and their neighbors.Children helped their parents by gathering eggs,milking cows, and harvesting crops.

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:27 PM Page 10

11Summer 2008 Historic New England

JuneBarn-raisingGathered string beans

JulySowed turnip seeds

AugustGathered hay and barley

SeptemberHarvested corn

��farmer’s field puzzle

word scramble

OctoberPicked apples and made ciderHarvested cabbages and turnips

NovemberSlaughtered hogs

A farmer had four sons and one hundred acres of land. He reservedone quarter, or 25 acres, in one corner for his own use, as shown inthis diagram. The father then told his sons that he would give themthe remaining 75 acres of land if they would divide it into four equallots of the same shape.

How were the lines drawn so that the 75 acres were divided intofour equal and similar lots? The sons satisfied the request of theirfather, and received their land, 181/2 acres each. Can you determinehow they divided the land? Answer found on page 12.

(Adapted from The American Agriculturalist, April 1881)

EEBF

LOWO

GSGE

ABCBESAG

IDERC

EEEHSC

AFLX

UBTRET

TYKUER

SDHEIRSA

Can you solve this puzzle?It comes from a magazine for farm families

published over one hundred years ago!

Since Colonial times, farms have been animportant resource for New Englanders,providing many goodsthat we need for dailylife. See if you canunscramble this list ofthings produced onfarms. Answers can befound on page 12.

25 Acres

75 Acres

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:27 PM Page 11

Historic New England Summer 200812

M A K I N G F U N O F H I S T O R Y

Directions1. Put a layer of gravel at the bottom of each pot, and thenfill with potting soil. For seeds, make small indentations in the soil. Plant seeds according to the depth and spacing rec-ommended on the packets. For plants, gently transplant theherbs into the new pots and fill in the remaining space withpotting soil.2. Write the names of the herbs on popsicle sticks and insertthem into the pots.

3. Water the pots and place them in a sunny window.Remember to follow the watering instructions on packets orplant labels.

As your plants grow larger, you can snip the herbs and use themin your favorite recipes. Some herbs can be dried for later use.To do so, hang small bunches in a dark, dry place for one tothree weeks. Store dried herbs in airtight glass jars.

—Amy Peters ClarkEducation Program Manager

Suppliessmall ceramic pots potting soilgraveltrowel or large spoonherb seeds or small herb plants from a local nursery—

basil, chives, cilantro, mint, oregano, rosemary, or sagewatering canpopsicle stickspermanent marker

Dav

id C

arm

ack

75 Acres

25 Acres

Answers to questions on page 11.beef, wool, eggs, cabbages, cider, cheese,flax, butter, turkey, radishes

grow an herb gardenfor a windowsill

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:27 PM Page 12

13Summer 2008 Historic New England

P R E S E R V A T I O N

Landmarks of the

Countryside

All over New England, barns are disappearing from the land-scape, slowly sliding into disrepair and decay or being heed-lessly demolished to make way for new development.Wherever a barn is not being used or maintained, it is in dan-ger of loss. No one really knows how many barns are lost eachyear in New England, but Vermont preservationists estimatethat one hundred of the state’s approximately twelve thousandbarns are razed annually. In parts of New England where agri-cultural uses are less viable, the losses are predictably higher.

Dav

id B

ohl

Dav

id B

ohl

ABOVE The large English barn at the

Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm, New-

bury, Massachusetts. Farmers often

added bays to their English barns,

sometimes doubling them in size

to accommodate growing herds

and new farming ventures. BELOW

A sliding barn door in Sutton,

Massachusetts.

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:27 PM Page 13

14 Historic New England Summer 2008

age. English barns could be enlarged by bays at the gableends or by lean-to additions. A variant type, known as theside-hill English barn, was built on a sloping site to providea cellar beneath the stables to store manure. Three sides ofthis cellar could be built of dry-laid fieldstone, with thedownhill side being open to the elements. Sometimes anexisting English barn would be moved to a slope and placedon such a foundation.

By the 1830s, a new form—the gable-front barn, or NewEngland barn—began to appear, paralleling the new taste forthe Greek Revival style in domestic architecture. Easier toexpand than the English barn by simply adding bays to oneend, the gable-front barn had the further advantage of shed-ding snow and rain at the eaves rather than the entrance.Early gable-front barns offset the main door and drive floorto allow for a large haymow, because hand-threshing to sep-arate grain from husks and stalks required large areas for haystorage. After the horse-powered mechanical thresher arrivedin New England and thereby reduced the amount of spaceneeded for hay, gable-end barns began to have central doors.

Around the middle of the nineteenth century, variouschanges, including technological improvements emerging outof the Industrial Revolution, began to affect barn construc-

Building a barn during the Colonial era in New Englandinvolved a major investment for the owner, because of theneed for skilled craftsmen and for timber. The farmer wouldemploy a master builder to design the barn and oversee con-struction; portions of the project, like the foundation and fin-ished carpentry, might have to be further subcontracted.Specialized artisans from England built the first barns, andconsequently these early barns followed English traditions,modified for New England’s climate and available material.

Colonial barns were timber framed, built from hard-woods that were felled locally, hewn square with felling axeand broad axe, and then joined together with pegged mor-tise-and-tenon joints. Custom-scribing, by which the mortisewas cut first and then the tenon was cut to match it, meantthat every joint was unique.

The English barn form endured for nearly two centuries.Often measuring thirty feet by forty feet, these barns typicallyfeatured a simple gable roof with a large door on both eavesides to permit a wagon to drive in one side and out the other.The interior was typically divided into three bays: a stable forthe animals, a threshing floor to process grain in the center,and a hayloft for hay storage. Overhead, a scaffold of simpleplanks or saplings acted as a hayloft for additional hay stor-

ABOVE Gable-front barn in Sutton, Massachusetts, probably built

after 1827, with its original hinged doors. It is larger than the ear-

lier English barns but smaller than later five-bay gable-front bank

barns. CENTER Balloon framing in a gambrel-roofed barn in South

Dav

id B

ohl

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:27 PM Page 14

tion. The availability of mill-sawn lumber allowed the stan-dardization of wood lengths. Square-rule carpentry, whichused a framing square to cut joints to pre-determined dimen-sions, made joints interchangeable. These developments per-mitted quicker construction by craftsmen with less special-ized skills. Meanwhile, hardwoods were becoming morescarce, so builders increasingly used softwoods like spruce,pine, and hemlock.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, balloonframing spread from the Midwest to New England. Balloonframing used long, continuous framing members, or studs,which ran from the sill up to the eave line, and nails as a fas-tening system. The process further reduced the level of skillneeded to construct a barn. During the same period, barnstended to be placed closer to the main dwelling, often at aright angle, to create a protected yard.

The simpler, lighter construction methods of the mid-nineteenth century resulted in a greater variety of barn types,adapted to local tastes and terrain. Gable-front bank barns,like side-hill English barns, were also built into sloping sites.The farmer could drop manure through a trap door to thecellar below, then distribute it to the fields with a manurespreader. The sliding barn door, a technological improvement

15

that was safer in high winds and easier to open in the pres-ence of heavy snow accumulations, debuted in new barns ofthe mid-nineteenth century. Exterior cosmetic detailing beganto appear on new barns, particularly in the pediments andeaves. Such details unified the barn with the style of the farm-house and other outbuildings and gave the farmstead anappearance of modernization, which was synonymous withexcellence. By the 1860s and ‘70s, the most fashionablebarns featured Gothic, Italianate, and Second Empire styling.A decade later, gambrel roofs became popular, because theyafforded a greater volume of space for the hay loft withoutan increase in wall height.

High-drive bank barns—three, four, or even five storiesin height—like the earlier bank barns, took even greateradvantage of gravity to make farm labor more efficient.These barns featured an earthen ramp leading to the barn’sloft level. Instead of hoisting the hay into the loft with a hay-fork, the farmer could drive up the ramp and offload hay andgrain with ease, shifting it into the haymow or to livestockbelow. High-drive bank barns were wide enough to permitthe wagon to turn around at one end of the barn and exitthrough the same door.

Summer 2008 Historic New England

Burlington, Vermont. Compare the studs (“light as a balloon”) with

the heavy timber framing in the Cogswell’s Grant barn illustrated

on the cover of this issue. FAR RIGHT, ABOVE A gable-front barn in

New Hampshire, with an impressive cupola. FAR RIGHT, BELOW A

twentieth-century gambrel-roofed barn.

Tho

mas

Vis

ser

John

Po

rter

John

Po

rter

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:27 PM Page 15

Historic New England Summer 200816

and light to circulate through the barn and included woodenair shafts rising from the stable level to the monitor.Connected barns, which permitted the farmer to walk fromhis house to barn and woodshed without going out of doors,are a regional variation seen primarily in New Hampshireand southwestern Maine. Conceived as an effort to modern-ize that added convenience for the farmer in areas of extremecold and snow, connected barns faded from popularity due tothe risk of fire spreading amongst the linked structures.

The twentieth century brought new building techniquesand materials, such as roof trusses, concrete, and corrugatedsteel. But the rapid changes brought by the modern era madethe New England family farm less competitive, and the barn’soriginal function as a tool for agricultural production waned.Today, the owners of historic barns appreciate their structur-al beauty and practicality as they adapt them to the needs ofa twenty-first century lifestyle.

—Daniel AulentiStewardship Manager

Less common barn types in New England includedround barns, monitor-roofed barns, and connected barns.Round barns, pioneered by the Massachusetts Shakers in thefirst quarter of the nineteenth century, became more commonin the early twentieth century and are particularly associatedwith dairy production. They utilized multiple levels in a man-ner similar to high-drive barns. Monitor roofed barns,appearing in the late nineteenth century, allowed more air

ABOVE Farmers in the coldest climates appreciated their connect-

ed barns, like this connected gable-front bank barn in New

Gloucester, Maine. BELOW This unusual high-drive barn features a

covered ramp at the gable end and an additional earthen ramp to

the second story at the eave side.

Co

urte

sy M

aine

His

tori

c Pr

eser

vati

on

Co

mm

issi

on

John

Po

rter

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:27 PM Page 16

17Summer 2008 Historic New England

y

ortunately, owners and preser-vation groups are workinghard to ensure that historicbarns don’t disappear from

the rural landscape. In every NewEngland state, efforts are under way toidentify, document, stabilize, and pre-serve historic barns. Statewide barnpreservation initiatives sponsor confer-ences, underwrite grant programs, andadvocate for the preservation and pro-tection of these icons of the region’sagricultural heritage.

Despite best efforts, however,statewide barn preservation programscan assist only a fraction of New Eng-land’s stock of historic barns. Thank-fully, barns are sturdy and generallyforgiving structures, and even minimalinterventions can keep a historic barnfrom the brink of collapse. Just as in allbuildings, particular attention to thecondition of the barn roof and founda-

tion is critical: leaky ventilators andcupolas, missing shingles, poor drain-age, and vegetation around the founda-tion will damage the underlying struc-ture and hasten failure. It is wise toclean out the barn to reveal its struc-tural condition and clarify treatmentoptions. Spreading sidewalls, a com-mon problem, can be managed byinstalling steel cables at major framingpoints to prevent further bowing andforestall collapse. Once you have eval-uated the barn’s condition, phaserepairs to focus on the most pressingthreats, stopping water infiltration andstabilizing the structure, so as to keepthe barn standing to await future work.

One award-winning organization,the Mount Holly, Vermont, BarnPreservation Association, has demon-strated what can be accomplished by asmall, dedicated group of volunteers.In one year, the MHBPA mapped and

F

photographed all 52 historic barns inthe tiny town, going on to documentthe status of 38 of those barns, andthen assisting in the stabilization of thefive barns identified as most in need ofimmediate attention. Historic NewEngland protects and preserves about170 barns and other outbuildings—110 in direct ownership at its historicproperties and another 60 throughpreservation restrictions administeredby the Stewardship Program. Many ofthese structures stand in protectedlandscape settings, reminders of ouragrarian past.

—Sally ZimmermanPreservation Specialist

Help for Old Barns

If you are the owner of a historic barn, there aremany sources for assistance and tips on main-taining and preserving these important andevocative structures. More information and linksto barn preservation organizations are availableonline at www.HistoricNewEngland.org/Barns.

State-based programs:• Connecticut Trust for Historic PreservationHistoric Barns of Connecticut Project(www.connecticutbarns.org)• Maine Historic Preservation CommissionHistoric Barn Preservation Grants(www.mainepreservation.org/barn1.htm) • Preservation Massachusetts Barn Task Force(www.preservemassbarns.org)• New Hampshire Preservation Alliance BarnAssessment Grant Program (www.nhpreservation.org/html/barns.htm)• Rhode Island Historical Preservation andHeritage Commission (www.rihphc.state.ri.us/)• Preservation Trust of Vermont Save VermontBarns (www.savevermontbarns.org)• Vermont Division for Historic PreservationBarn Grant Program(www.historicvermont.org/financial/barn.html)

An early bank barn, c.1850, in Peacham, Vermont, which is part of the Josiah

and Lydia Shedd Farmstead and is listed on the National Register of Historic

Places. In 2007, the current owners were awarded a $10,000 Barn Grant

towards stabilizing and repairing the structure.

Co

urte

sy V

erm

ont

Div

isio

n fo

r H

isto

ric

Pres

erva

tio

n

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:28 PM Page 17

Historic New England Summer 200818

ew England has a rich heritage of gardendesign, the most impermanent of the designarts. While much of this legacy has been lost,images of some of the vanished landscapes sur-

vive in Historic New England’s Library and Archives. Thisselection of watercolors, plans, and historic photographsillustrates major themes of the region’s landscape history.

New England gardens of the Colonial period and theFederal era were influenced primarily by English design. Theyears following the American Revolution were affluent timesin the region, and the merchant and professional elite devot-ed considerable financial resources to fostering experimentalagriculture and horticulture. Their country estates echoedthe naturalistic concepts of English designers Lancelot“Capability” Brown and Humphry Repton. The writings ofJohn Claudius Loudon encouraged a return to formality insmaller, more urban gardens.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, a distinctiveAmerican style emerged. It embraced the native picturesquelandscape while seeking, through design, to tame and refinethe national character. Landscape gardener Andrew JacksonDowning (1815–52) emerged as one of the most influentialvoices in American taste through his popular books on land-

L A N D S C A P E

NLost Gardens of New England

THIS PAGE The Lilacs, Thompson Kidder’s country seat inMedford, Massachusetts, was one of many estates, large andsmall, developed in towns near Boston after the Revolution.These watercolor drawings provide a detailed picture of theunity of ornament and productivity in landscape design around1808. The main approach to the house features a curved driveand a circular garden, defined by regularly-spaced flowers andshrubs. Simple wooden trellises flank the front entry, and vinestwine around the pair of columns to complete the symmetricalcomposition. The rear tract of land was intensely cultivatedwith fruit trees and a vegetable garden. Kidder also developeda series of terraces with curvilinear beds in order to maximizethe planting area on the steep site. The practical design wasbalanced with aesthetic touches, such as winding paths and alattice summer house.

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:28 PM Page 18

19Summer 2008 Historic New England

THIS PAGE During the early years of the New Republic, New England’s prospering port towns and cities saw the construction ofmany high-style residences. Typically, the building lots were narrowbut had considerable depth. In contrast to the naturalistic park-likedesigns found on rural estates, these urban gardens tended to besymmetrical and enclosed.

ABOVE This 1812 plan of the garden at the Rundlet-May House inPortsmouth, New Hampshire, depicts the grid design laid out byJames Rundlet in 1807. The house was situated on a terraced site,with two acres of gardens, including plant beds, gravel walks, and an orchard. A long shed and stable separated the service yard fromthe gardens. Rundlet kept detailed records of expenses at his proper-ty. Plant purchases made between 1807 and 1809 included pear andpeach trees, grapevines, and rose bushes. Subsequent records docu-ment the cultivation of asparagus and potatoes. The landscape’s for-mal arrangement was in keeping with the ordered context of city life.

LEFT Two photographs taken c. 1899 depict the Brockway garden in Newburyport, Massachusetts, which dates to the Federal era andshares many similarities with the garden at the Rundlet-May House.Both houses were elevated on grass terraces with fences enclosingthe front yards and had deep rear gardens. Each was organized into geometric-shaped beds, but the Brockway garden was of a more complex design than the simple rectilinear forms of JamesRundlet’s garden.

scape gardening and domestic architecture,which promoted the interdependence of beautyand usefulness. He described two major types oflandscape, the “beautiful”—with serpentinelines, soft grasslands, and groupings of deciduoustrees—and the “picturesque”—with irregularlines, rough ground, and pointed evergreens.

Downing’s innovative ideals of rural lifewere superseded as the century progressed.Designers like Frederick Law Olmsted, also influ-enced by the English landscape tradition, foundnew ways to integrate nature with decorative ele-ments. Other designers looked to the past forinspiration. Publications such as Alice MorseEarle’s Old-Time Gardens, 1901, and EdithWharton’s Italian Villas and Their Gardens, 1904,provided models that spawned a rich and eclecticchapter in American garden history.

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:28 PM Page 19

Historic New England Summer 200820

LEFT A. J. Downing’s theory of the ideal environment—one slightlyremoved from the urban center—influenced the landscape of theAmerican suburb. In 1856, Boston architect Luther Briggs, Jr.,designed a house and grounds in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, forgrocer Ephraim Merriam. Briggs probably took his inspiration forthe Italianate house from one of Downing’s architectural patternbooks— either Cottage Residences (1842) or The Architecture ofCountry Houses (1850). Briggs’s plan for the landscape surroundingthe house also reflects Downing’s recommendations in the use ofornamental plantings, fruit trees, and a grape trellis.

BELOW Benjamin Rand, a Cambridge, Massachusetts, carriagebuilder, constructed his Italianate house on a large plot of land in1855. The extensive grounds, enjoyed by the Rand family foralmost one hundred years, included ornamental plantings, a neatvegetable garden, a cutting garden for flowers, and a small orchard.A greenhouse was located in the more utilitarian section, whilegravel paths connected the wisteria-covered summer house withother recreational areas. The Rand family’s suburban oasis, photographed c.1890, is now the Porter Square Shopping Center.

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:28 PM Page 20

21Summer 2008 Historic New England

LEFT Beginning in the late nineteenth century,New Englanders increasingly sought the help ofprofessional designers to plan their gardens.Elaborate greenhouses were often included aspart of a large professional design. This green-house was proposed for the estate of publisherEdwin Ginn of Winchester, Massachusetts. Thegreenhouse was probably designed by theIrvington, New York, firm of Lord & Burnham.

BELOW AND RIGHT “All our roads seem to lead us toward the Hamilton House,”wrote Emily Tyson to her friend, author Sarah Orne Jewett. Located on a high bluffoverlooking the Salmon Falls River in South Berwick, Maine, the Georgian house wasbuilt about 1788 by prosperous West Indies merchant Jonathan Hamilton. Captivatedby the beauty of the house and its evocative setting, Emily Tyson and her step-daughter,Elise, purchased the property and the surrounding one hundred and ten acres in 1898.

The Tysons created a series of gardens compatible with the house’s Colonialcharacter, including an elaborate sunken garden surrounded by a vine-covered pergola,a cutting garden enclosed by an arborvitae hedge, and a cottage garden. One of themany garden writers who visited Hamilton House noted, “In isolation, simplicity, andripeness the atmosphere of the whole place breathes of olden days, and might well be taken as a model for a perfect American garden.”

Unfortunately, the pergola and other architectural elements were destroyed by ahurricane in the 1950s. The elms that were planted around the house and along theriver bank succumbed to Dutch Elm disease. The cutting garden evolved into a shade garden as the arborvitae hedge grew to be thirty feet tall. Historic photographs, likethese taken by George Brayton, c.1923, guide Historic New England as it works toretore this splendid Colonial Revival garden.

This article is based on theexhibition Lost Gardens ofNew England, which repro-duces numerous images fromthe Library and Archives,along with original gardenornaments from the collec-tion. The exhibition will beon view from June 29 toOctober 31 at the HeritageMuseums & Gardens, 67Grove Street, Sandwich,Massachusetts, www.heritage-museumsandgardens.org. Thetext of this article is adaptedfrom the exhibition text byLorna Condon, ElizabethIgleheart, and RichardNylander.

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:28 PM Page 21

Historic New England Summer 200822

O B J E C T S T U D Y

he details are intriguing.Four figures appear in sil-houette against a backdrop,executed in pencil and

wash, of an elegantly furnished room.One woman is shown in the act of cut-ting a silhouette of a gentleman seatedin a rocking chair. Pencil lines enhancethe silhouettes, delineating the gentle-man’s eyeglasses, the scrolled arms ofthe rocking chair, lace on the cap of theolder woman, and the elaborate hair-styles of the younger women.

The composition was created byAuguste Edouart (1789–1861), a pro-lific French silhouette artist who visitedthe United States between 1839 and1845 and cut 3,800 “likenesses in profile.” Edouart skillfully cut his“shades,” as they were also called,with embroidery scissors; according toone sitter in Baltimore, he had “themost remarkably accurate eye I have

ever seen.” Edouart summered inSaratoga, New York, and traveled therest of the year to cities like New York, Philadelphia, New Orleans, andWashington. During his stay in Bostonbetween November 1841 and June1842, he created likenesses of manyprominent inhabitants, including twelvemembers of the extended Appletonfamily. The figures represented here areMr. and Mrs. Samuel Appleton with aniece and a friend.

A native of New Ipswich, NewHampshire, Samuel Appleton came toBoston to seek his fortune in 1794, atthe age of twenty-eight. He became asuccessful merchant and helped his twobrothers, Nathan and Eban, and hisfirst cousin, William, become success-ful as well. Retiring in 1810, he invest-ed in several other business ventures,and was extremely generous in his phil-anthropy. In 1819, when he was fifty-

In Mr. Appleton’s Parlor

Tthree, he married Mary Lekain Gore,the much younger widow of a formerbusiness partner, and commencedbuilding a new house at 37 BeaconStreet.

Edouart’s depiction of the Apple-tons’ parlor is replete with details thatdocument Boston’s taste in furnitureand decoration during the first half ofthe nineteenth century. The roomexemplifies the effect described byNathan Appleton when he orderedobjects for his own house, desiringthem to be “stylish” and “elegant” butnot “showy.” There are fluted pilastersin the corners and beside the archreflected in the chimney glass. A man-tel, composed of two varieties of marble, provides the room’s focalpoint. It may have been provided by a relative, Thomas Appleton, whoimported chimney pieces in Boston atthe time. A simple plaster cornice and a

LEFT This group

silhouette of the

Appleton family is

signed at lower right,

“Augte Edouart.

Fecit 1842./Boston.

U.S.[A.]”

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:28 PM Page 22

23Summer 2008 Historic New England

TOP An 1848 copy of Gilbert Stuart Newton’s portrait of

Appleton. LEFT This silver ewer is ornamented with a small

bust portrait of Appleton under the spout, as well as engraved

images of his Boston residence on one side and his New

Hampshire birthplace on the other. ABOVE The green silk tri-

angles near the center of this patchwork are identified in the

label as “Mrs. Samuel Appleton’s Curtains.”

large rosette in the center of the ceiling,from which hangs an Argand chande-lier, complete the restrained decoration.

The principle furnishings include apier table between the windows, a cen-ter table, a pair of sofas—all in theclassical style—and two large lookingglasses with simple, matching frames.The sofas copy a design published inAckermann’s Repository of the Arts in1821, which was favored by severalBoston cabinetmakers. The plant standin the window is a more ephemeralpiece of furniture, a type that does notoften survive. The unusual placementof the sofas—one against the wall andone perpendicular to the fireplace—may have been more common than wemight suspect. Edouart depicted a sim-ilar grouping in his silhouette of theDaniel Parker family of 40 BeaconStreet, also executed in 1842.

Textiles play a major role in thedecoration and would have providedboth pattern and color. The carpet was a major source of pattern.(According the Appletons’ niece, Fanny

Longfellow, there were also frescoes onthe ceilings.) The elaborate two-toneddrapery treatment is crowned with afringed valance, while a decorativeband trims the bottom edges of the cur-tain panels. The sofa upholstery wasprobably a woven silk or a cut andvoided velvet, both commonly used byBoston upholsterers at the time.

The paintings on the rear wallillustrate types of art favored byBostonians—family portraits and OldMaster paintings. The artist has ren-dered them so carefully that we canidentify one as Gilbert Stuart Newton’s1818 portrait of Appleton and theother as a copy of Titian’s Woman witha Mirror. Interestingly, the small full-length silhouette beneath the portrait depicts another “shade” ofAppleton by Edouart.

Auguste Edouart was renownedfor the fidelity of his likenesses of people. In the Appleton family group,he has also given us a faithful image of their Boston parlor. But what adds a special charm to this work is that

it depicts one of its personages—Mr. Appleton—four times. Was Mrs.Appleton really cutting a silhouette ofher husband, or did the artist add thatdetail as a flattering and witty gesturetowards his patron?

—Richard C. NylanderCurator Emeritus

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:28 PM Page 23

24 Historic New England Summer 2008

News New England & Beyond

A Gala EveningOver 280 influential people gathered at the Four Seasons Ballroom in Boston onJanu ary 4 for a Gala evening that raised$245,000 in net proceeds towards supportof the education and public outreach pro-grams offered by Historic New England.

ABOVE Gala Co-chairs Susan Sloan and Anne Kilguss with

President and CEO Carl R. Nold.

ABOVE Trustee Joan Berndt, Board Chair William Hicks, and

Ernst Berndt.

ABOVE Leigh and Leslie Keno respond to lively bidding on the trip to

Argentina.

ABOVE Lead Corporate Sponsor William

Vareika with President and CEO Carl R.

Nold.

Pho

togr

aphy

by

Mic

hael

Dw

yer

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:28 PM Page 24

25Summer 2008 Historic New England

Nold assumes chair of AAM Historic New England Presidentand CEO Carl R. Nold has beenelected chair of the AmericanAssociation of Museums for theterm 2008–2010. The AAM repre-sents more than 15,000 museumsof all types and devotes itself togathering and sharing knowledgeon issues of concern to the profes-sion, developing standards and best

practices, and advocacy. Nold has been active in the AAMfor many years, most recently serving as vice chair.

Off the beaten pathFor an unusual experience, visit Historic New England’sstudy properties, which are open specific days this season.Ten of the properties are rare building types dating fromthe First Period of European settlement; most have escapedsignificant alteration and are left unfurnished in order toshowcase their construction methods. The framing andmasonry reflect the regional origins of the early settlers,who brought with them building practices they learned inEngland and adapted to the materials available to them inthe New World.

In addition to the First Period buildings, other studyproperties include the Georgian-style Rocky Hill MeetingHouse in Amesbury, Massachusetts, which remains in pris-tine condition; the Quincy House in Quincy, Massachusetts,a country house that preserves the history of a prominentBoston family; and the Merwin House in Stockbridge,Massachusetts, a Federal-style house that was updatedduring the Colonial Revival era as a summer residence.Admission is free to members; please consult your Guideto Historic New England or visitwww.HistoricNewEngland.org for details.

Bring family and friends We urge you to check the events list-ing in the “What’s Happening”newsletter and visit the website tofind the many enjoyable programsoffered at our historic sites all overthe region. There are crafts fairs,farmers’ markets, walking tours,

plant sales, antique car meets, lectures, and hands-on activi-ties to interest everyone. Make an excursion to a propertyyou haven’t visited yet, bring a picnic, enjoy the landscape.Our site staff can tell you about other things to do in thevicinity to help you plan your day.

MASSACHUSETTS

Rocky Hill Meeting House, AmesburySunday, May 18Saturday, June 28

Cooper-Frost-Austin House, CambridgeSunday, May 18Sunday, August 10

Pierce House, DorchesterSaturday, May 10 Saturday, Oct. 25

Dole-Little House, NewburySunday, May 18Saturday, June 7Saturday, Oct. 4

Swett-Ilsley House, NewburySaturday, June 7Saturday, July 5Saturday, August 2Saturday, Sept. 6Saturday, Oct. 4

Quincy House, QuincySaturday, July 12Saturday, August 16

Gedney House, SalemSaturday, June 7Saturday, July 5Saturday, August 2Saturday, Sept. 6Saturday, Oct. 4

Boardman House, SaugusSaturday, June 7Saturday, July 5Saturday, August 2Saturday, Sept. 6Saturday, Oct. 4

Merwin House, StockbridgeSaturday, June 7Saturday, Dec. 6

Browne House, WatertownSaturday, June 7Saturday, Sept. 27

NEW HAMPSHIRE

Gilman Garrison House, ExeterSaturday, June 7Saturday, July 19Saturday, August 23

RHODE ISLAND

Arnold House, LincolnSaturday, June 7 Saturday, July 12Sunday, August 17Saturday, Sept. 20Sunday, Oct. 5 Sunday, Oct. 12

Clemence-Irons House, JohnstonSaturday, May 3Sunday, Oct. 12

Study property open dates.

Dan

iel

Nys

tedt

Dam

iano

sPho

togr

aphy

.co

m

Bo

b St

egm

aier

ABOVE Boardman House, c.1687, Saugus, Mass.

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:29 PM Page 25

141 Cambridge StreetBoston MA 02114-2702

Non-Profit OrganizationU.S. Postage

PAIDBoston, Massachusetts

Permit No. 58621

homes were often used to play hymns.This particular example was a presentfrom a Civil War veteran to his wife for their home in Pittsfield, NewHampshire. Built by the Prescott OrganCompany, Concord, New Hampshire, afamily run company that had beenmaking musical instruments since1809, the instrument passed to female

he beautiful but simple decoration on this organsuggests the Gothic style of church architecture. In-

deed, all organs have what one historiancalls a “persistent ecclesiastical associa-tion,” and those purchased for private

T

A C Q U I S I T I O N S

Sacred and Profane

Visit www.HistoricNewEngland.org to hear arecording of the donor’s mother and sisterplaying the organ.

descendants and finally to a family inHaverhill, Massachusetts, who recentlydonated it to Historic New England.

During the second half of the nine-teenth century, the parlor organ wasnearly as popular in America, at leastfor a time, as the piano. Few middle-class homes were without one or theother. A parlor organ cost less than halfof the price of a piano and took up lessspace, while satisfying many of thesame needs and providing a formidablesymbol of culture and refinement.Before Edison’s invention of the phono-graph in the late 1870s, the only way tobring music into the home was to per-form it.

—Nancy CarlisleCurator

LEFT Parlor organ, c. 1875. Prescott

Organ Co., Concord, New Hampshire.

Gift of Susan Foster Vogt.

Dav

id C

arm

ack

psi27987_Historic.qxp:psi27987_Historic 6/5/08 4:29 PM Page 26