HARVARD - University of California, San Diego

Transcript of HARVARD - University of California, San Diego

May-June 1981Volume 83, Number 5

PRESIDENT'S REPORT

AMERICANCIVILIZATION

LITERATURE

EDUCATION

VITA

PHOTOGRAPHY

DISCOVERY

HARVARDMagazine

FACING PAGE: The first leaves of spring appear on Mill Street, which dividesLowell House from John Winthrop House. Lowell's lesser tower is at left. Thephotograph is by Michael Nagy.

ROUNDTABLE ---------------------

Essays: The oilman cometh. The scars that remain. Last words. 4The Science Watch: William Bennett on new cancer research. 16Letters: The eclipse of 1780, nonsense DNA, Harvard on the edge. 19.

ARTICLES -----------------------

Business and the academy 23A re-examination of the use and abuse of professorial talent. By Derek C. Bok.

The manongs of California 36Migrant farm workers from the Philippines reaped discrimination and povertyin America. By Peter W. Stanley, with photographs by Bill Ravanesi.

Historian of the present 47Daniel Aaron has a massive editing project in hand-' 'the most completely frank,revealing diary in all of American history." By George Howe Colt.

"Taking blocks out of women's paths" 54At Radcliffe's Bunting Institute, founded two decades ago, the scholarlyenterprise has many faces. Written and photographed by Georgia Litwack.

Joan of Arc 59A brief life of the virgin warrior (1412-1431) on the 550th anniversary of hermartyrdom. By Deborah Fraioli.

Manufacturing, marketing, and modernism 60Harvard's photographic archives document a hidden aesthetic from the IndustrialRevolution. Fifteenth in a series by Christopher S. Johnson.

The senses are for survival 64AWe may be oblivious to many, but a host of sensory cues allow living beings tocope with their environment. By Lorus J. Milne and Margery Milne.(DISCOVERY is bound in to subscribers' and donors' copies only.)

POETRY-----------------------

By Lloyd Schwartz, Richard Eberhart, Jenny Joseph, Robert Dana, Robert Bly.Pages 9, 10, 12, 18,53.

DEPARTMENTS

This issue 4 ... Chapter and verse 13 ... Puzzle 20 ... Extra credit 64 ... Classified 65... Any questions? 72

Cover photograph by Bill Ravanesi. Other picture credits, page 22.

MAy-JUNE 1981 3

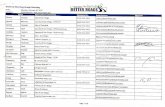

Themanongsof CaliforniaTens of thousands of Filipinomen immigrated to the UnitedStates during the 1920s andearly 1930s, seeking a betterlife as farm laborers. Taken forgranted, victimized, theyquickly sank almost to thebottom of American society.But they survived. Now oldmen, alone together, they callthemselves manongs-olderbrothers.

by Peter w. Smoley

36 HARVARD MAGAZINE

Few international relationships ofthe twentieth century have beenas poignant as that between the

United States and the Philippines. Having traded extensively in the archipelago in the nineteenth century, ruled itfrom 1899 to 1946, and supported itsgovernment economically and strategically since then, the United States hasbeen the most important outside influence on Philippine life. The enormousdisparity between the wealth and powerof the two peoples, along with the relatively libertarian character of u.s. rulein the islands, dazzled many Filipinosand drew them toward a deferentialfriendship for Americans. Filipinos became, in the condescending but kindlyintentioned words of William HowardTaft, our "little brown brothers," andhave remained more or less in that relationship ever since. Japanese scholars, preparing for their country's occupation of the archipelago in WorldWar II, noted a psychological dependence upon America among Filipinos,a phenomenon that modern intellectualsin the islands denounce as "binationalism." Even now, though Americannaval and air bases have become flashpoints for Filipinos' n~tionalism, moststill regard the United States affectionately as the historical source of schools,roads, public-health programs, artesianwells, democratic political institutions,and' the most gregariously informal,backslapping imperialist rulers knownto history.

Ironically, however, the Philippinesand the Filipinos have never attractedcomparable interest or devotion fromAmericans. Like a small spot on theperiphery of our vision, they have beenhard to see clearly, and therefore easyto take for granted. This has be,en sofrom.the very beginning. President William McKinley, who ordered Hit: annexation of the islands followingDewey's famous victory in 'Ma~ila Bay,said that he could not have gue~sep t~eir

actual location within two thousandmiles! Then as now, China and'Japanwere our principal interests in Asi'l; andeven as an American colony, the Philippines seemed to many little rrior~ thana 'cluster of "island stepping stones" 'offthe coast of China. Such good worksas the American-instituted pUblic-schoolsystem, celebrated to this day'by I'ilipinos, were all P'lid for by Philippinetaxes. And when, during the' GreatDepression, American protectioni§tsand isolationists branqed the' ~hil!p-

pines an economic and strategic liability, Congress moved quickly to rid itselfof the burden. The Tydings-McDuffieAct of 1934 established an internallyautonomous Philippine Co'mmonwealth, promised independence withina decade, and took steps to reduce thecompetition of Philippine agriculturalexports and Filipino immigrants in theAmerican t;:conomy.

Few have suffered more from America 's indifference to the Philippines thanthe Filipinos who migrated to the UnitedState~. As "American nationals"-theirstatus until the 1934 act reclassifiedthem ~s aliens-Filipinos could migratefreely to this country, but could notbecome citizens. Fired by the imagesof wealth, progress, and freedom intheir American-designed textbooks andenticed by labor contractors for Hawaiian and Californian agricultural interests, tens of thousands came here inthe 1920s and early 1930s, seeking abetter life. By 1930 more than l08,OOOlived here. "Birds of passage," asAmericans called them,· they weremostly young Ilocanos-residents ofthe northwestern part of the island ofLuzon-hoping to make enough moneyto support and eventually rejoin familiesthey had left behind. The idea was toreturn home after a few years, buy land,and finish life as a small freeholdingfarmer. American employers, .findingtransient laborers cheaper and less likelyto unionize, encouraged this aspiration.In Hawaii, the standard labor contractfor Filipinos actually guaranteed returnpassage after completion of an agreedamount of work.

Although Filipinos proved to be excellent tann laborers, they quickly fellvictim to a variety of forces beyondtheir control and sank almost to thebottom of American society. Successors to the Chinese and Japanese farmworkers of the past, and forerunners ofthe Mexican migrant workers of today,the Filipinos harvested mainly povertyand discrimination. Although Americanwages were high by Philippine standards, so was the cost of living. Duringthe mid 1920s, the going wage in Hawaiiwas $2.25 a day; in California, it wasless than twenty cents an hour. Obligations to family, perhaps the d.eepestsocial value for Filipinos, required thatsome of this be sent home to the Philippines. Even with primitive housinganq Some other benefits thrown in, dailyexpenses took most of the rest. Unable

(continued on page 44)

"Through them we may at lastsee Filipinos as they saw themselves ..."

Photographs by Bill Ravanesi.

MAY-JUNE 1981 37

38 HARVARD MAGAZINE

MAY-JUNE 1981 39

40 HARVARD MAGAZINE

1'·iL

MAY-JUNE 1981 41

42 HARVARD MAGAZINE

MAy-JUNE 1981 43

PHOTOGRAPHS COPYRIGHT © 1981. BILL RAVANESI

44 HARVARD MAGAZINE

THE MANONGS(continued from page 36)

to accumulate the savings they had oncedreamed of, the workers faced the humiliating choice of returning home asfailures or resigning themselves to a lifetime of poverty in America.

Those who stayed faced social andlegal constraints at least as painful astheir economic plight. Ineligible for citizenship and therefore unable to protecttheir interests at the ballot box, Filipinos were forbidden by various statelaws to own land, marry white women,or enter certain professions. (Theselaws lasted, in most cases, until the1940s.) After their designation as aliens

in 1934, they tempor~rily lost even theirright to public assistance, a major concern during the Depression. To add insult to injury, a 1940 ruling by the federal government required all Filipinoresidents of the country to register andbe fingerprinted, even though theirhomeland was still American territory.

Many found, moreover, that laws andofficial regulations were the least oftheir problems. Ever since the Louisiana Purchase Exposition at St. Louisin 1904, to which the American government of the Philippines sent an ethnographic exhibit of primitive tribesmen,many Americans had thought of Filipinos as dog-eating savages. This, plustheir racial difference from most Amer-

icans, intensified and emotionalized opposition to Filipinos' immigration. Evenin the mid Twenties, when their laborwas greatly needed in the fields ofHawaii and California, Filipinos weredenounced for stealing American jobsand reducing the standard of living ofAmerican workers. The American Federation of Labor demanded a 'ban onFilipino immigration; and, at the locallevel, threats and actual violence againstFilipinos grew in frequency and seriousness. With the coming of the GreatDepression, this grew much worse. Filipinos (and their white employers, onoccasion) were attacked over even themost menial and undesirable jobs. Transient gangs of whites, for example,drove Filipinos out of many Californiaberry fields in the early Thirties.

Even more often, violence againstFilipinos sprang from incidents overwhite women. Since almost no onecould pay for the transportation ofwomen from home, the sex ratio of theFilipino population was grotesquelylopsided: fourteen men for every womanamong Filipinos in California during theearly 1930s. In a way, this was the cruelest blow of all. For, combined with theantimiscegenation laws prohibiting intermarriage with whites, the absence ofFilipino women doomed most of thehopeful young men who had come toAmerica to rootless and lonely lives.

Although many Filipinos, particularly those in Hawaii, eventually returned to the archipelago, thousandsmore remained in the United States.Even under the Draconian quota of fiftyentries per year imposed when Filipinos were reclassified as aliens, almost100,000 could be counted in the 1940census. Special exemptions after thewar helped raise the figure to 123,000in 1950. During the first two decadesafter the war, these aging migrants fromthe Twenties and Thirties were, withgrowing numbers of Mexican~, thebackbone of California's agriculturallabor force.

To survive the rigors and disappointments of American life, andto fill at least part of the void left

by the absence of families, thesegrounded and stranded" birds of passage" began as early as the 1920s toorganize community institutions. Formany reasons, it proved hard work..

The impoverished and peripatetic life

of most of the agricultural workers wasa major obstacle. Typically, the menwould work as waiters, bellmen, domestic servants, and the like in WestCoast cities during the winter, and thenset out in March to follow the crops orhead for Alaska's canneries. Thoughsome with luck or special skills madea success of this, others remained miredin the poverty that had afflicted themfrom the beginning. Often these werethe peqple who most needed supportiveinstitutions. One such group collectedmoney for 38 years before amassingenough to build a clubhouse.

Another problem was that men whohad come originally from different partsof the Philippines often found it difficultto conceive of each other as sharing anational identity. Dozens of small, precarious fraternal groups formed aroundcommon places of origin-the Asinganian Club for men from Asingan in Pangasinan Province, the United Sons ofCamiling for former residents of Camiling, Tarlac-or the coincidence ofsome unusual American address, likethe Filipinosotans of Minnesota. Similarly, small local newspapers rose andfell in great profusion.

Apart from fledgling professionalgroups, like the Filipino Nurses Association, the most effective bridges between Filipinos were agricultural unions.Racially, legally, and socially vulnerable, Filipinos were particularly hard hitby the Depression. In response to wagecuts and spiraling violence directedagainst them, Filipino workers in theSalinas Valley organized the FilipinoLabor Union in 1933. Although it failedin its goal of organizing all thirty thousand compatriots then working in California's fields, it did win several payraises-from twenty to thirty cents perhour-before passing from the scene.It was followed in 1939 by the FilipinoAgricultural Laborers Association, organized around a core of six thousandasparagus workers in the Stockton, California, region. Moderately successfulin improving wages and working conditions, FALA also opened a cooperative food store before collapsing in theunusual labor markets of World War II.

In the late 1950s, the immigrants ofthirty years before-still poor, but nowno longer young-decided to try again.By this time their illusions were meager,and their goals modest. Few of themstill dreamed of returning to the islands.Old men, alone together in a land thatwas not theirs, they called themselves

manongs (older brothers). At the time,they were making a little over a dollaran hour, plus five cents per box, in thegrape fields. They wanted a union tobetter their wages, and to support andprotect them when they would no longerbe able to work. Their answer was toorganize the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, in 1959. And thistime, at last, they succeeded. Six yearslater, AWOC made history when athousand of its members triggered whatwas to become the Great Grape Strikeof 1965. A week later, Cesar Chavez'sNational Farm Workers Associationjoined them; and shortly thereafter thetwo groups merged to form the UnitedFarm Workers.

The men pictured in the foregoingphotographs, by Bill Ravanesi,are manongs who, however hum

bly and however late, have finally founda home in America. Literally so, sincesome of them now live in the retirementvillage built by the UFW with funds wonin the great strike. They are a dyingbreed, yesterday's "little brown brothers" grown old. There will be no morelike them. Since the liberalization ofAmerican immigration laws in 1965, anew wave of Filipino immigrants hasflooded into the country, far more numerous than the agricultural workers ofthe prewar era. The newcomers are better educated, more affluent. Many ofthem are highly skilled professionalpeople, proud men and women whohave voted with their feet against thedictatorship of President FerdinandMarcos. They are successors not to themanongs, but to the pensionados (subsidized students) and the thousands ofother Filipino students and professionals drawn to America over the years.Theirs is the world of the future.

The manongs , on the other hand, area link with our past. And with somethinglarger that transcends time and nationality. Through them we may at last seeFilipinos as they saw themselves, andwitness a small triumph of the humanspirit. 0

Peter W. Stanley, formerly a memberof the Harvard history department, received the A.B. from Harvard in /962and the Ph.D. in /970. He is now deanof Carleton College, Northfield, Minnesota. For a note about photographerBill Ravanesi see page 4.

MAy·JUNE 1981 45