Harappan Site of Sidduwala in Cholistan: An IntroductionCholistan received heavy monsoon showers...

Transcript of Harappan Site of Sidduwala in Cholistan: An IntroductionCholistan received heavy monsoon showers...

Harappan Site of Sidduwala in Cholistan: An Introduction

Farzand Masih1 and Amna Tofique1 1. Department of Archaeology, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan (Email: [email protected], [email protected])

Received: 26 August 2014; Accepted: 21 September 2014; Revised: 18 October 2014 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 2 (2014): 844‐853

Abstract: This article is about the Harappan site of Sidduwala located in Cholistan desert. Previous archaeological activities at the site and its current status due to vandalism are described in this paper. It also describes classification of pottery which consequently indicated the occupation of the site by various groups during different phases of Harappan culture.

Keywords: Cholistan, Hakra, Sidduwala, Harappan, Pottery, Total Station, Vandalism

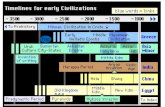

Introduction Cholistan desert in general and the border regions of the Hakra River (Fig. 1) in particular are predominantly located with archaeological sites of Early, Mature and Late Harappan Periods along with the sites of Historic Period. As a fraction of Great Indian Desert, the Cholistan desert, lies within the southeast quadrant of Punjab province, Pakistan (Rao et al. 1989). This desert covering an area of 2.6x1010 m2 is placed between 27° 42ʹ and 29° 45ʹ N and 69° 52ʹand 73° 05ʹ E (Ahmed 2012: 165; Arshad et al. 2009: 1322; Vandal et al. 2011: 10).

Cholistan received heavy monsoon showers about 5000 years ago. In the fourth millennium BC, Cholistan was a prosperous fertile land watered by Hakra River and populated by people of Indus Civilization (Farooq et al. 2010: 126). Gradual and slight changes in climate caused a shift in monsoon winds and decline in rainfall and ultimately converted the area into a desert (Ahmed 2011: 321; Farooq et al. 2010: 127; Arshad et al. 2006). With the beginning of third millennium BC, Hakra River witnessed continuous fluctuations due to earthquakes. In second millennium BC, the river changed its course several times and around 600 BC it dried up completely (Ahmed 2012: 165; Arshad et al. 2009: 1322; Vandal et al. 2011: 10).

Archaeological Surveys and Previous Works in Cholistan Desert Archaeological importance of Cholistan desert was lime lighted for the first time when Italian Indologist L. P. Tessitori conducted surveys in northern Rajasthan (India) and

Masih and Tofique 2014: 844‐853

845

Bikaner (Pakistan) in 1916 and 1918. Thereafter, Sir Aurel Stein (1941), Henry Field (1959), M. R. Mughal (1987) and Farzand Masih (2013) conducted archaeological investigations in the area. Among these, Farzand Masih specially focused on the state of vandalism in this archaeological zone of great magnitude.

Figure 1: Map of Old Hakra River Bed and Cholistan Desert

It is unfortunate that despite being the land of mysteries and the cradle of ancient civilization, no one took serious notice of this region. Even the Federal Department of Archaeology hasn’t considered it for protection or further probing. The result is that this important area has remained unattended for a long time and has suffered a lot due to cultural and natural transformations. It has been noticed that the institutions and organizations like deer sanctuaries managed by the government of UAE (Fig. 2), army maneuvering (Fig. 3), activities of Cholistan Development Authority, land grabbers, Punjab wild life and NGOs working on various development schemes in Cholistan, due to lack of awareness, heavily disturbed the contours of the cultural mounds of Cholistan. Presently most of the land has been sold by Nawab family. Consequently, the new owners are converting the desert into agricultural lands (Fig. 4). Particularly the area of deer sanctuaries has been completely procured by cultivators who have already installed number of tube wells and changed the desert into agricultural land (Fig. 4). Large numbers of robbers’ trenches visible in the archaeological sites also confirming the treasure hunters’ interest in this area (Fig. 5). Recently, the developmental works initiated by the government, especially the road construction projects encouraged the archaeologists to give attention to this region, before it completely vanish along with several un‐veiled mysteries (Masih 2013).

ISSN 2347 – 5463 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 2: 2014

846

Figure 2: Ganweriwala – Four Meter Wide Road for the Travel of Princes of UAE

Figure 3: Ganweriwala ‐ Evidence of Army Manoeuvring

Masih and Tofique 2014: 844‐853

847

Figure 4: Wattu Wala: Converting the Cholistan Desert into Agricultural Land

Figure 5: Ganweriwala – Robbers’ Trench

ISSN 2347 – 5463 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 2: 2014

848

Sidduwala The site of Sidduwala (Fig. 6) first reported by Sir Aurel Stein (1995: 87) in 1940 is located in the heart of Cholistan desert. The site covers an area of 448.66 meters north to south and 553.51 meters from east to west. Later in 1997, Rafique Mughal reported six mounds (Fig. 7) at Sidduwala namely Sidduwala A (28° 57ʹ 18ʺ N; 71° 13ʹ 28ʺ E), Sidduwala B (28° 57ʹ 43ʺ N; 71° 13ʹ 40ʺ E), Sidduwala C (28° 58ʹ 00ʺ N; 71° 14ʹ 02ʺ E), Sidduwala D (28° 58ʹ 13ʺ N; 71° 14ʹ 11ʺ E), Sidduwala E (28° 58ʹ 23ʺ N; 71° 14ʹ 01ʺ E) and Sidduwala F (28° 58ʹ 18ʺ N; 71° 13ʹ 25ʺ E). First author explored the site again in 2007 and 2011 respectively. During 2011, the site was systematically surveyed and mapped thoroughly with the help of GPS and Total station.

Figure 6: Location of Sidduwala

Like many of the archaeological sites, the mounds of Sidduwala also highly disturbed due to cultural and natural agencies. The ceramics scattered over the surface is highly damaged due to weathering and vehicles of deer hunters. However, a large number of ceramics were collected from the site, macroscopic details of them were recorded and shapes of the vessels were reconstructed through drawings.

Pottery from Sidduwala Though the pottery assemblage of Sidduwala is diverse in quality and quantity, it will not be ideal to completely rely on the ceramic data from the site for archaeological elucidations. The principal obscurity is that each and every sherd of the ceramic assemblage was recovered from the surface and it lack context. In the absence of stratigraphy, the chances of mixing up of ceramics from different cultural phases are more. Majority of the ceramic sherds from Sidduwala are highly damaged due to

Masih and Tofique 2014: 844‐853

849

Figure 7: Various Mounds of Sidduwala

Figure 8: Harappan Ceramics from Sidduwala

ISSN 2347 – 5463 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 2: 2014

850

Figure 9: Cemetery H Type Ceramics from Sidduwala

cultural and natural agencies. Hence, it is very difficult to differentiate various wares of different cultural periods. In the midst of these severe limitations, the authors were able to divide the pottery into two broad categories i.e. Harappan Pottery and Non Harappan pottery.

Harappan Pottery This category can be further divided into two classes i.e. Mature Harappan Pottery and Cemetery H Type Pottery (Late Harappan). Sherds of both classes collectively consist of one third of whole assemblage.

Mature Harappan Pottery: At Sidduwala, there are very limited sherds of pots and dishes which display conventional features of Mature Harappan pottery (Fig. 8) like deep glossy red slip, fine texture, well firing and typical painted motifs. Among decorative motifs on sherds, intersecting circles, banana leaves, neem leaves and peepal leaves are common. On the basis of manufacturing and decoration, it can be assumed that either these vessels were produced locally by the Harappan potters or transported from other sites. These ceramics show similarities to the pottery from Harappa, Mohenjo daro, Ganweriwala and Wattuwala.

Masih and Tofique 2014: 844‐853

851

Cemetery H type Pottery: At Sidduwala, a few ceramics have cultural affinities with Cemetery H assemblage in texture, fabric color, thickness, slip, decoration, typology and morphology (Fig. 9). This category of pots/jars at Sidduwala possesses simple and beaded rims, long neck, slender body and short pedestal base. They are coated with dull orange/tan slip and have paintings (bands) in black over the rim and long neck. Another vessel type in this category is heavy dishes with rounded or beaded rim, red slip and burnished surface. The dish/basin sherds have carination and such vessels were reported from many sites in Cholistan (Mughal 1997). The well fired carinated vessels show red slip and streak burnishing. Certain rim forms of Mature Harappan pottery and Cemetery H type pottery from Sidduwala are similar.

Figure 10: Non Harappan Pottery from Sidduwala

Non Harappan Pottery This category comprises of two third of the total collection of Sidduwala pottery. It frequently exhibits irregular surface features due to scrapping and smoothing. This coarse pottery show burnishing and ill firing. Dominantly it is plain and if slipped, cream slip is dominant with poor adhering power. Majority of the painted vessels lack slip. The vessels are decorated mostly with simple bands but a few sherds have motifs like multiple loops, concentric circles, wavy lines, parallel multiple loops and cross

ISSN 2347 – 5463 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 2: 2014

852

hatched triangles. The non Harappan pottery (Fig. 10) show close affinity to those from Chanhudaro, Jhukar, Madina and Mitathal.

Conclusion Majority of the Sidduwala pottery is of coarse texture, ill fired and porous in comparison to well manufactured Harappan pottery. It speaks a lot about the behavior and economy of the relevant society, co‐existence of various groups, differences in craftsmanship and social activities. Coexistence of various groups can be estimated by the occurrence of Harappan pottery along with dominant Non Harappan type.

References Ahmed, F. 2011. Soil Classification and Micromorphology: A Case Study of Cholistan

Desert, Journal of Soil Science and Environmental Management Vol. 2(11), pp 321‐328.

Ahmed, F. 2012. Spectral Vegetation Indices Performance Evaluated for Cholistan Desert, Journal of Geography and Regional Planning Vol. 5(6), pp. 165‐172.

Ahmed. F, H. A Samad, F. Sher, M. Asim and M. Arif Khan. 2010. Cholistan and Cholistani Breed of Cattle,Pakistan Veterinary Journal, Bahawalpur.

Arshad, M., A. Hussain, M. Y. Ashraf, S. Noureen and M. Akhter 2009. Study on Agro morphological Variation Germplasm of Lasiusrus Scindicus from Cholistan Desert Pakistan, Pakistan Journal of Botany Vol. 41(3), pp 1331‐1337.

Chaudhry, S. M., N. Sial and N. A. Chaudhary. 2003‐2004. Natural Resources And Their Utilization, WithSpecial Reference To Cholistan Desert, Pakistan, Science Vision, Vol. 9, pp 1‐4.

Dar, S. Z. 2007. Sights in the Sands of the Cholistan, Bahawalpur History and Architecture, Oxford University Press, Karachi

Dikshit, K. N. 2012. The Lost Sarswati: A Prelude to Urbanization, Ancient Pakistan Vol. I, pp 19‐35.

Din. M. M. 2001. Bahawalpur State with Map 1904, Sang ‐e‐ Meel Publications, Lahore. Field, H. 1959. An Anthropological Reconnaissance in the West Pakistan 1955, Peabody

Museum, Cambridge. Geyh. M. A. and D. Ploethner. 1995. An Applied Palaeohydrological Study in

Cholistan, Thar Desert, Pakistan, Proceedings of the Vienna Symposium, August 1994. IAHS Vol. 232, pp 119‐127.

Ghosh, A. 1995. The Rajputana Desert: Its Archaeological Aspect In S.P. Gupta (ed) The Lost Sarswati and the Indus Civilizations, pp 98‐107, KusumanjaliPrakashan Publishers, Jodhpur.

Hameed. M, ,M. Ashraf, F. Al‐Qurainy, T. Nawaz, M. Sajid, A. Ahmad, A. Younas and N. Naz. 2011. Medicinal Flora of the Cholistan Desert: A Review, Pakistan Journal of Botany, Vol. 43, pp 39‐50.

Khan, F.M., H. R. Chaudhry, Y. S. Mustafa, W. Ahmad and H. M. Farhan. (2011) Ethno‐Veterinary Zoo‐Therapies and Occult Practices In Greater Cholistan Desert, Science International Vol. 23(4), pp 241‐243.

Masih and Tofique 2014: 844‐853

853

Khan, M. F. 2009. Ethno‐Veterinary Medicinal Usage of Flora of Greater Cholistan Desert Pakistan, Pakistan Veterinary JournalVol. 29(2), pp 75‐80.

Kumar, M., A. Uesugi, V. S. Shinde, V. Dangi, V. Kumar, S. Kumar, A. K. Singh, R. Mann and R. Kumar. 2011. Excavations at Mitathal, District Bhiwani (Haryana) 2010‐11: A Preliminary Report, PuratattvaVol 41, pp 168‐ 178.

Kumar, M., V. Shinde, A. Uesugi, V. Dangi, S. Kumar and V. Kumar. 2008. Excavations at Madina, District Rohtak, Haryana 2007‐08 A Report.

Lal, B. B., J. P. Joshi, B. K. Thapar and M. Bala. 2003. Excavations at Kalibangan, Veerendra Printers, New Delhi.

Masih, F. 2013. Research Report: Sui Vehar and archaeological reconnaissance of Southern Punjab, Department of press and Publication, Lahore.

Mughal, M. R. 1995. Recent Archaeological Research in Cholistan Desert In S.P. Gupta (ed) The Lost Sarswati and the Indus Civilizations, pp 98‐107, KusumanjaliPrakashan Publishers, Jodhpur.

Mughal, M. R. 1997. Ancient Cholistan, Archaeology and Architecture, Ferozsons(pvt) Ltd, Lahore.

Panhwar, M. H. 1979‐86. Hakra or Sarswati Controversy‐Versions of Scientists, Historians and Folk Lorists. Sindhological Studies,pp 24‐57.

Rao, A. R., M. Arshad and M. Shafiq. 1989. Perennial Grass Germplasm of Cholistan Desert and its Phytosociology. Cholistan Institute of Desert Studies, Islamia University, Bahawalpur, Pakistan, p. 160.

Shinde , V. 2008. Exploration in the Ghagger Basin and excavations at Girawad, Farmana (Rohtak District) and Mitathal (Bhiwani District), Haryana, India, I n O s a d a and Akinori Uesugi (ed) Linguistics, Archaeology and the Human Past, pp. 77 ‐ 158 Kyoto.

Smith, M, A. 2007. Settlement Geography of the Punjab during the Early Historic and Medieval Periods: A GIS Approach, Proquest Information and Learning Company, United States.

Stein, A. 1995a. Survey of Old Sites along the Hakra bed, In S.P. Gupta (ed) The Lost Sarswati and the Indus Civilizations, pp 57‐98, KusumanjaliPrakashan Publishers, Jodhpur.

Stein, A. 1995b. Along the Ghakker in Bikaner, In S.P. Gupta (ed) The Lost Sarswati and the Indus Civilizations, pp 01‐39, Kusumanjali Prakashan Publishers, Jodhpur.

Stein, A. 1995c. From Jodhpur to Bahawalpur, In S.P. Gupta (ed) The Lost Sarswati and the Indus Civilizations, pp 40‐57, Kusumanjali Prakashan.Jodhpur.

Valdiya, K. S. 2002. Sarswati: The River That Disappeared, Universities Press India Ltd, Hyderabad.

Vandal, S. H., N. Naseer, S. Samee and A. Imdad 2011. Cultural Expression of the South Punjab, THAAP, Lahore.

Wright, R. P., R. A. Bryson and J. Schuldenrein. 2012. Water supply and history: Harappa and the Beas regional survey. Journal of Marine Systems, Vol. 89 (1), pp.61‐75.