Habermas, Pupil Voice, Rationalism, and Their Meeting with Lacan’s Objet Petit A

-

Upload

paul-moran -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of Habermas, Pupil Voice, Rationalism, and Their Meeting with Lacan’s Objet Petit A

Habermas, Pupil Voice, Rationalism, and Their Meetingwith Lacan’s Objet Petit A

Paul Moran • Mark Murphy

Published online: 13 October 2011� Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2011

Abstract ‘Pupil voice’ is a movement within state education in England that is associ-

ated with democracy, change, participation and the raising of educational standards. While

receiving much attention from educators and policy makers, less attention has been paid to

the theory behind the concept of pupil voice. An obvious point of theoretical departure is

the work of Jurgen Habermas, who over a number of decades has endeavoured to develop a

theory of democracy that places strong significance on language, communication and

discourse. This paper is an attempt to gauge the usefulness of Habermas’ approach to

understanding the theory of pupil voice, in particular how his theory of universal prag-

matics lends itself to a ‘philosophy of between’, a philosophy that finds echoes in the

conflicted nature of schooling that ‘pupil voice’ is supposed to rectify to some extent. The

paper also explores the drawbacks of a Habermasian approach, in particular his overreli-

ance on rationality as a way of understanding communication. Lacan’s concept of the objet

petit a is introduced as an alternative way of understanding pupil voice.

Keywords Pupil voice � Rationality � Habermas � Lacan � School democracy

Introduction

In the past 5 years, ‘pupil voice’ has joined a growing list of concepts that have met with

approval from diverse groups across the educational and political spectrum. No wonder, as

any term that appeals to proponents of democracy, inclusion, citizenship and also stan-

dards, achievement and accountability is effectively guaranteed a positive reception. A

strong part of its attraction lies in its objective of identifying pupils as stakeholders in

education, ‘‘who shape the implementation of policy and become part of the solution’’

P. MoranFaculty of Education and Children’s Services, University of Chester, Parkgate Road,Chester CH1 4BJ, UK

M. Murphy (&)King’s Learning Institute, King’s College London, 57 Waterloo Road, London SE1 8WA, UKe-mail: [email protected]

123

Stud Philos Educ (2012) 31:171–181DOI 10.1007/s11217-011-9271-6

(Whitehead and Clough 2004, p. 215). This emphasis on inclusion of pupils in planning

and decision making is seen by many to have enormous benefits for learning, for example

in the field of foreign languages, where pupils can ‘‘act as a ‘conduit’ to their respective

linguistic communities and can provide a valuable insight in linguistic terms into the

complex and nuanced issues inherent in such communities’’ (Payne 2007, p. 89).

This positive reception among many, however, has not prevented it from raising the

suspicions of some who view pupil voice as a convenient foil for more conservative

agendas. Thomson and Gunter (2006, p. 840) believe that senior policy makers have a

tendency ‘‘to bring ‘pupil voice’ into the policy conversation as a means of achieving

school improvement and higher standards of attainment, rather than as a matter of the UN

convention, citizenship and rights’’. In some of the alternative literature on the subject,

however, the rights of the child are very much to the fore (e.g., Lundy 2007), with the likes

of Whitehead and Clough (2004, p. 216) arguing that the emphasis on pupil voice is

effectively ‘‘given legitimacy’’ via the UN convention on the rights of the child.

Others have questioned the utility of a concept such as pupil voice, based on the myriad

practical challenges inevitably faced when attempting to implement it. Deuchar (2009,

p. 35) warns that pupil voice can too easily be reduced to ‘‘isolated pockets of pupil

consultation’’ rather than a ‘‘school-wide democratic practice’’. He also makes the point

that pupils themselves may not be ready—pupils may find it ‘‘difficult to adjust to the idea

of being given more say in what and how they learn’’ (Deuchar 2009, p. 35). As Cremin

et al. (2011, p. 587) put it, care needs to be taken to avoid the assumption that change is

‘‘within the grasp’’ of children.

Authors are correct to question some of the assumptions regarding notions of ‘pupil’

and ‘voice’. Aside from the issues raised above, pupil voice is not immune from problems

raised by the often troublesome relationship between notions of ‘voice’ and notions of

‘power’. As Thompson (2009, p. 672) suggests, listening to children is a starting point, but

‘‘we must also understand how their voices are co-constructed.’’ This dilution of pupil

voice in the context of schools and schooling is compounded by the fact that there tends to

be ‘‘too much focus on adult procedures’’ which can limit children’s ‘‘ownership of

decision-making processes’’ (Cox and Robinson-Pant 2006, p. 515).

Taylor and Robinson (2009, p. 161) are correct to state that student voice is a ‘‘nor-

mative project’’ that aims to ‘‘give students the right of democratic participation in school

processes.’’ They are also correct when they state that the overwhelming focus on the

practical aspects of such school-based intervention means that relations of power tend to be

overlooked, reflected in the fact that they have ‘‘received little theoretical elaboration as

yet’’. This can be seen as a major shortfall in discussions over student voice: as Sellman

(2009, p. 9) argues in his study of peer mediation services in schools, schools ‘‘perhaps

underestimate the degree to which principles of power and control’’ provide barriers to the

implementation of pupil voice.

Issues of power, as they do with numerous endeavours, act as a thorn in the side of pupil

voice; as such, theoretical elaboration is necessary and justified. The current paper’s

attempt to ‘apply’ the work of Habermas and Lacan is a modest effort to help plug this gap.

Given the obvious differences between their approaches, such an attempt was never going

to be straightforward. The following summaries and applications are designed to identify

what both can offer to the debate over pupil voice, with the proviso that such a task cannot

be completed without highlighting just as many troubling issues as solutions (if solutions

are indeed possible in the first place).

172 P. Moran, M. Murphy

123

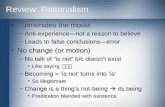

Habermas and the Philosophy of Between

Throughout his career, Habermas has understood the need for some kind of normative

grounding for his critical theory of society. In order to achieve this grounding, and in line

with other continental thinkers (Best 1995, p. 145), Habermas drew on the ‘linguistic turn’

in philosophy and social theory, a turn that re-interpreted the traditional problems of

consciousness as problems of language (Best 1995, p. 145). This emphasis on the primacy

of language over consciousness meant for Habermas a shift away from the notion of the

monological self in isolated interaction with other isolated selves, to a focus on the

intersubjective dimension of self-development and social interaction. According to Hab-

ermas, following Mead, significant others are ‘always already there’, in the sense that our

sense of self-identity is intimately tied into relationships with others (Murphy and Fleming

2010, pp. 6–7).

A shift to a linguistic intersubjectivity meant Habermas could base his work in a

‘‘standard of procedural reason’’ (Sciulli 1992, p. 300), sometimes in the literature referred

to as Universal or Formal Pragmatics. By doing so, Habermas ‘‘proposes that the sover-

eignty of subjective interests may be challenged on the basis of a set of intersubjective

interests that is irreducible’’ (Sciulli 1992, p. 300). The development of this formal

pragmatics via a turn to a linguistically-constituted intersubjectivity permits the discussion

of ‘‘claims to truth, truthfulness, and right independently of their cultural context’’ (Steele

1992, p. 435). At the same time, the shift to universal pragmatics provided Habermas with

a more solid basis for developing an ‘‘optimistic orientation to critical theory’’ (Calhoun

1995, p. 32), than say his critique of transformations of the public sphere or the crises of

legitimation facing late capitalist societies.

From universal pragmatics developed a theory of communicative competence—i.e.,

‘‘the speaker’s ability to communicate … derived from a pre-theoretical knowledge that is

universal to all speakers’’ (Braaten 1991, p. 58). By engaging in the act of linguistic

communication, speakers commit themselves to the conditions that facilitate the possibility

of what Habermas calls the ideal speech situation. Possibly his most famous concept, the

ideal speech situation ‘‘offers the possibility of a rational consensual basis for interaction

free of force, open or latent’’ (Braaten 1991, p. 64).

Habermas uses discourse ethics to ‘‘justify a normative basis for social criticism’’

(Blaug 1999, p. 3), with the ideal speech situation ‘‘anticipated in every act of actual

argumentation’’ (Blaug 1999, p. 9). According to this theory, all communication is open to

being tested as to whether it is comprehensible, sincere, truthful and appropriately

expressed. Habermas calls these validity claims and they are redeemed in what he calls

discourse or communicative action. In fact, in performing any speech action, we raise

universal validity claims and assume that these claims can be vindicated (Habermas 1979,

p. 2). Validity claims are the assumptions that we always already make in an unquestioning

manner concerning the truth and sincerity of another’s communications. This questioning

of assumptions underpins not only the traditional sciences but also the social sciences

(Murphy and Fleming 2010, p. 33).

Not only can validity claims be redeemed but two more important dimensions flow from

this. First, in being able to engage in this kind of discourse our real needs can be identified,

agreed on and the process begun of transmitting these needs (discursive will-formation) to

the political sphere for inclusion in public policy, law and hopefully realized. Second there

is a set of rules for this discourse. These mean that all are heard, no one is excluded, all

have equal power to question the justifications of others, to ask questions, all are equal in

making decision and reaching conclusion, coercion is excluded and the only power

Habermas, Pupil Voice, Rationalism, 173

123

exercised is the power of the most reasonable argument. Not only are validity claims

redeemed in this rule-led discourse but these are the conditions for a democratic society.

There is something romantic about the work of Habermas which follows from its

commitment to a certain form of rationalism. This rationalism also incorporates a kind of

historicism, through which the work is located. It is a historicism that, explicitly within his

early work (Habermas 1962), writes the possibility of rationalism as the emergence of a

critical social space within the eighteenth century; a possible social space within which he

locates his own work, as immanent critique, pressing outwards, disruptively, upon the

politically and socially defining dogmas of industrial and post-industrial Western society.

The historicism is irreducible because the movement of Habermas’ critique occurs at the

brink of epochs; the conception of epoch or some other similarly grand defining movement

is absolutely necessary because it is between the spaces of their succession that Habermas

is able to position his disruptive analysis. Essentially this analysis is a critique of ideology

that can occur because a public space opens within society as a result of economic, cultural

and intellectual pertinences; and it is within these interstices of subsuming, self-interested

material and linguistic dominance, that a form of communication and reflection can be

nurtured that is authentic to itself. It is this authenticity that is able to reflect upon and

critique the surrounding material and cultural forms of dominance as products, as forms of

collaboration that maintain existing sets of knowledge, channels of exchange, hierarchies

of validation; and so is able to draw a distinction between this space, inhabited by

authenticity, and that space, identified as being, ontologically and epistemologically,

inauthentic.

It is not coincidental that the historicism of Habermas’ critique also locates itself,

historically, between other adjacent epochs: between the West at the end of the Second

World War, and the West’s post-war reconstruction; between the economic triumph of

twentieth century industrialization, and fears engendered by Western consumerism;

between the consciousness of liberal democracy, and Marxist criticisms of false con-

sciousness and reification. Indeed, if nothing else, Habermas is a philosopher of the

between; a between based upon the construal, but perhaps, given the historicism and

historical nature of his work, generation would be a more telling term; a between then,

based upon the generation of successive teleological moments that arrange themselves, so

this generation tells us, with a between; a between within which the rational consciousness

of immanent critique both realizes the onto-epistemic truth of each moment and each

moment’s succession, and simultaneously articulates the proper, alternative, authentic

trajectory, as process and goal.

If this seems a rather grand description of Habermas’ work, then it is a grandeur that is

nothing less than such a work rationally demands. How else, in what other landscape, can

rationality, as Habermas describes it, figure? Doesn’t this conception of teleological

movement, a conception that the rational figure conceives and invests with a reciprocal and

mutually reinforcing onto-epistemic identity, require such a perspective? And isn’t there,

thus, an inevitability about this; an inevitability that supports the rational figure and the

march of epochs; an inevitability that the consciousness of immanent critique will be

configured within the seriousness of this romantic landscape, and will be configured

somewhat heroically, standing out, pointing towards truth, clothed in nothing other than a

kind of naked authenticity that proclaims the truth of its own project? And a necessity that

the Habermasian rational figure encounters of this landscape is its absolute functionality.

Absolute functionality in this context refers to the way that everything that the rational

figure encounters, and everything about the rational figure is purposeful because it engages in

some way with the teleological progress of social construction and epochal movement, even

174 P. Moran, M. Murphy

123

by way of critique and disruption. We see this in Habermas’ description of communication

and instrumentality. In The Theory of Communicative Action (Habermas 1984) two domains

are brought together: both are teleologically motivated; and between them we observe the

figure of rational consciousness. The two domains are famously the domain of lifeworld and

the domain of systems. Lifeworld is in a Heideggerian sense the lived experience of social

being; and it is embodied in various integrated and self-organizing systems, such as the

family, culture and art, and the politics involved in the daily negotiation of these and other

naturally occurring systems within this domain. It is characterized, again in a way that is

reminiscent of some of Heidegger’s work, by a ready-to-handedness, which is a form of

ontological condition within which Being and the context within which this exists, are the

same; for example the understanding of one’s self as a member of a family engaged in a

particular form of work: in this way, identity is embedded within lifeworld. By contrast, the

domain of systems, principally money and power, engineer the societal infrastructures that

sustain an industrial and post-industrial capitalist society.

An important difference that distinguishes the domain of lifeworld from the domain of

systems is the difference signalled by communication. Within the domain of lifeworld

communication is organized around collective agency, is purposeful and is in a Heideg-

gerian sense an affirmation of Being, of humankind embedded within the context of their

existence. Communication within the domain of systems does occur, but it is, within this

Habermasian framework, a form of reproduction that is driven by the exigencies of

infrastructure demands. Examples of these demands include: the recruitment, organization

and payment of employees; the management of economic systems; and the administration

of state and market institutions. Whilst the domain of lifeworld clearly requires the domain

of systems, within a Habermasian framework, ideally the two domains ought to be distinct;

and this is where Habermas’ work also embraces an ethical imperative attached to his

conceptualization of ontology: the very nature of large capitalist societies, the importance,

the proliferation and the ubiquity of the domain of systems that they require to operate

inevitably leads to the colonization of the domain of the lifeworld by the domain of

systems. That is, modes of being, in Heideggerian terms distinguished from Being, that are

a function of, to repeat the examples above, the recruitment, organization and payment of

employees; the management of economic systems; and the administration of state and

market institutions, the types of interactions that they require, the language that they

inhabit, come to exist parasitically within the lifeworld.

Again, it is the between that Habermas marks out, the between the domain of the

lifeworld and the domain of systems that is occupied by the rational figure; a rational figure

that is able, through the perception afforded by rationalism, to identify both domains, the

improper occupation of the one by the other, and through this power of identification, to

articulate an immanent critique that will serve as a corrective to this scenario of colonized

habitation. Before proceeding any further, it is important to emphasize the role of teleology

and absolute functionality within this sketch of Habermas’ work. The domain of lifeworld

is teleologically predisposed to articulate itself on ontological grounds; this is how life-

world exists, it is the encounter of humanity with itself in its natural societal context, as

that which is ready-to-hand. The domain of systems within modern capitalist societies is

also teleologically predisposed to reproduce itself because it serves to facilitate, indeed it is

necessary for the existence of, lifeworld within a modern capitalist context. It is the

teleological predisposition of these domains that drives their absolute functionality within

the Habermasian schema.

Habermas, Pupil Voice, Rationalism, 175

123

Habermas and Pupil Voice

From the domain of systems we have techno-bureaucratic procedures, formulated as ‘tar-

gets’ and ‘goals’, ‘performance’ and ‘league tables’ which are instituted across education

within the state sector by official regimens of scrutiny and evaluation. A highly valued

outcome of this system’s process, by the system, is a ranking schema, which perceives

education largely as a form of performance; and inevitably those institutions and individuals

that find themselves towards the bottom of the schema are identified as ‘failing’. The

teleology of the system here is such that not only does it clearly reproduce itself, driving

itself forward through governmental inspection and evaluation bodies that determine cur-

riculum content, curriculum delivery, modes of pedagogy and engagement with learning for

teachers and pupils; it also comes to colonize the other domain, the domain of lifeworld.

Lifeworld here is that which the techno-bureaucratic procedures—their evaluation of

education as a form of performance, their determination of ranking schemas and identifi-

cation of failure, in short the domain of systems—is parasitic upon. Obviously, so this logic

goes, the techno-bureaucracy of systems could not exist on its own; it could not even

precede that which it is designed to regulate; and that precedent, that fundamental condition,

is the experience of education itself, namely the educational lifeworld. Now, very much in

keeping with the Habermasian vision and again also reminiscent of the Heideggerian notion

of ontology as that which is ready-to-hand, the lifeworld of education must be experience of

education itself because it is fundamentally an engagement with self through natural con-

text, which is most typically situated within the classroom in the English state education

system. Indeed, the system’s performative, competitive, ranking schema that results in the

label ‘failing’ is contrasted with a lifeworld understanding of education as a learning,

demanding, complex process, so emphasizing the lifeworld ontology as an interactive,

collaborative, democratic experience of lived educational being. It is this ontology that the

proponents of ‘pupil voice’ take to be primary, formative and authentic; and it is by rec-

ognizing, giving space to, and listening to ‘pupil voice’, so the proponents of this critique

argue, that the system’s ‘‘…model [that] has infiltrated education…’’ can be resisted.

The emphasis on pupil voice as a tool of resistance to domination by system imperatives

clearly echoes a number of Habermasian themes, in particular the power of intersubjective

communication to counter processes of colonisation. Proponents of pupil voice view

language in the classroom in much the same way Habermas views universal pragmatics—

as a basis from which to create more democratic forms of interaction between system and

lifeworld. Granted, pupil voice is a normative concept, while universal pragmatics is

viewed (controversially by some) as a foundational concept, but Habermas’ focus on

communication free from domination offers a potentially viable framework within which

to understand not only democratic forms of schooling, but also the broader role of edu-

cation in fostering active citizenship and supporting civil society. Pursuing a Habermasian

frame of reference, the centrality of pupil voice in processes of schooling could be seen as

a way of fostering democratic forms of governance within an increasingly technicised

lifeworld—a way of theorising pupil voice that places it within the broader context of

power and participation.

There are, however, a number of interesting problems with this project that Lacan’s

concept of the objet petit a exposes and analyzes. The next section introduces a Lacanian

analysis of Habermas’ work via the objet petit a; but instead of limiting this discussion to the

theoretical arena, it explores the play between Habermas and Lacan within an aspect of

current English state educational policy, practice and critical discourse, namely ‘pupil voice’.

176 P. Moran, M. Murphy

123

Lacan, Trajectories and the Objet Petit A

‘‘For Lacan, the objet petit a represents an unconscious clinging to an impossible desire that

cannot be shared or satisfied…’’ (Kirshner 2005, p. 88); it is realized, however, as an object,

but an object whose meaning is never properly understood. To appreciate this, the

mechanics of the objet petit a, the role it plays in the discourse of the self and the motivation

of identity, it is important to think about the trajectory of desire. In Lacanian theory desire is

not desire for something as focussed on a particular object, nor in this same way is it a

particular desire for as in some emotion corresponding to a particular wish; instead, desire is

a function, a result, of a fundamental misapprehension: this misapprehension is one of the

defining properties that contributes to our being human subjects. Let us consider a simple

example: A feels thirsty and wants a drink. We could say that A desires a drink, but this

would be to miss what A is articulated by. In no particular order, the following overlapping

contingencies all play a part in constituting A’s desire: the physiological feeling that A is

thirsty; the situation that A finds A being in; and A’s representation that A is thirsty, and this

last point does not matter if A represents this to A’s self, or both to A and others. Let us

begin with the last of these: A finds A in a street opposite a bar and says to B, A’s

companion, ‘‘I’m thirsty; I could do with a drink.’’ Several contingencies are now imme-

diately obvious, which produce something else; this something else is the displacement,

though perhaps dispersion would be more descriptively telling, of what we have taken to be

the original motivation of satisfying A’s thirst. A’s wish for a drink is not equivalent to A’s

utterance to B, ‘‘I’m thirsty; I could do with a drink,’’ nor is it equivalent to A’s repre-

sentation of this utterance to A. The wish for a drink, the impulse to satisfy a need, is,

however, caught up in its representation, indeed, in its realization; but this is not the same as

the impulse to satisfy the need itself, though this in itself cannot be separated from its

representation. The in itself is caught sight of, dispersed, displaced, lost by its articulation. It

is this loss that functions as the site of Lacanian desire.

The articulation of loss and the in itself occurs on the plane of representation, which is

not perfectly reflexive: A’s utterance is not purely representational; it does not simply stand

in for the thing itself until the thing itself is gained, in this example, A’s drink; nor does it

return to A without remainder, leaving the various pieces of the ensemble intact and

discrete. There is always, for example, in the form of representation, a remainder; a

remainder that is not entirely consumed by the functionality of the represented form (we

will come back to this point). The plane of representation is a cultural and linguistic plane,

that is to say, it is bound up with a system of articulation located within a specific historical

frame; it is also outside what we have taken to be the original motivation of A to satisfy

A’s thirst, but is simultaneously stitched into A, since it is only through this plane of

representation, the Symbolic Order, that this motivation can be known. What we therefore

witness when A utters, ‘‘I’m thirsty; I could do with a drink,’’ is A being split, and also,

mythically, being whole, being both continuous and discontinuous with that which is both

outside and inside A. The Symbolic Order—the linguistic system and the historical-cul-

tural context, the moment that A finds A in the street, opposite a bar—precede A; but it is

only by being part of them, by being sutured to them, that A and the fulfilment of what A

wants can be identified and acted upon, which is also different to the in itself of A’s thirst

and concomitant need to satisfy that thirst. And how is A cognizant of this scene of

misrecognition, within which A functions and can be known and identified: how does A

know? We are on the threshold, now, of the objet petit a, or at least an understanding of the

scene through which the objet petit a functions.

Habermas, Pupil Voice, Rationalism, 177

123

Lacan refers again and again to the scene within which the subject apprehends the

subject, in our example, A apprehending A, as occurring within the domain of the scopic,

and more particularly apprehension of the object around which this apprehension is

focussed, as occurring within the circuit of the gaze (Lacan 1986). What does this mean,

what is the gaze? If we return to the scene within which A conceives and misconceives A,

we cannot help but note that it depends upon A perceiving A: and so A perceives A

perceiving A. This circuit is the gaze. A perceives A as part of the Symbolic Order, which

has already involved the displacement or dispersal of A as well as A’s articulation by that

which is external to and precedes A’s identity. And around what does this perception

cohere? Well, around the form of representation that is pertinent to this moment, which in

our example is the utterance, ‘‘I’m thirsty; I could do with a drink.’’ It is only because, as we

have already noted, the representation is not absolutely adequate to its proposed func-

tionality, that a residue of some sort is left; and it is this residue, this little object that is other

to that which it represents, that is not entirely used up in the representing process, that is

both more and less than symbolic, be it somatic, acoustic, visual or whatever, and is also

discontinuous with but representative of the subject, in this case A, that A can perceive it as

such, and can therefore also perceive A perceiving A. As Lacan, perhaps somewhat ellip-

tically notes: ‘‘The gaze sees itself… The gaze I encounter—you can find this in Sartre’s

own writing—is, not a seen gaze, but a gaze imagined by me in the field of the Other [the

Symbolic Order]… Is it not clear that the gaze intervenes here only in as much as it is… the

subject sustaining himself in a function of desire?’’ (Lacan 1986: 84–85). The locus of the

gaze within the scene which is profoundly one of misrecognition is the objet petit a: the

‘‘I’m thirsty; I could do with a drink,’’ is the subject looking at looking at; and unsurpris-

ingly it is also the point of the realization of rationalism, in an obviously Cartesian sense.

Whilst Lacan does not quite develop this notion as specifically as saying, the realization

of the subject looking at looking at is the unfolding of Cartesian rationalism, he does allude

to ‘‘… the Cartesian subject, which is itself a sort of geometrical point, a point of per-

spective…’’ (Lacan 1986, p. 86); but it is not very difficult to see how this is so. The

famous, ‘‘Je pense donc je suis’’ of Descartes (1637), translated into Latin as ‘‘Cogito, ergo

sum’’ (Descartes 1644/1984), is conditional upon the apprehension of the subject appre-

hending the subject, apprehending ‘‘I think, therefore I am,’’ and signals the quintessential

(mis)recognition of the objet petit a, as subject, against the screen of the Symbolic Order,

which is profoundly what the subject is not, but nevertheless must also involve misrec-

ognizing the subject as so being. The implications here for Habermasian rationality, for the

project of rationality in general, are most interesting. In the final section of this paper, we

will explore these implications in relation to ‘pupil voice’.

(Mis)apprehending Apprehending Education Apprehending ‘Pupil Voice’and Rationalism

Given the apprehension of the Cartesian subject, though the apprehension of apprehension,

it is easy to see the parallel between this example of the gaze and the gaze of education

which perceives ‘pupil voice.’ Reporting on Rudduck (2003), Whitehead and Clough

(2004) comment:

If schools in Education Action Zones (EAZs) are going to make real strides in raising

behaviour and academic standards then they need to start consulting pupils,

according to the authors of this research report. The Government established the first

178 P. Moran, M. Murphy

123

(EAZs) in 1997 to raise standards of behaviour and academic attainment in areas of

significant disadvantage. Education Action Forums (EAFs), the local decision

making bodies within EAZs, were asked to empower people and communities to find

radical, innovative solutions to problems of underachievement. But few zones have

explicitly involved students in this process (Whitehead and Clough 2004, p. 1).

The subject of education, its apprehension of itself as itself by noticing its apprehension of

education, is clearly visible here. But as we have also seen, this involves misrecognition, in

a number of ways. As before, there is the misrecognition of the subject as being continuous

with the Symbolic Order. But what is the subject here? The Symbolic Order is much easier

to point to than the subject. The Symbolic Order is composed, amongst other things, by

EAZs, EAFs, the criteria that are used to define ‘‘standards of behaviour and academic

attainment,’’ ‘‘areas of significant disadvantage’’ and ‘‘underachievement’’; it includes the

mechanisms through which performance against these various criteria are calculated and

structures through which the ensuing results are circulated, debated and acted on in various

ways, such as the drawing up of plans, and instantiating pedagogic and resource strategies.

And if the Symbolic Order includes all of these and other forms of representation and

systematic organization, doesn’t it also then include that within itself which it designates as

a certain kind of lack, namely ‘underachievement’ and the vast majority of zones which

‘‘… have [not] explicitly involved students in this process [of consultation and

engagement]’’? Isn’t the Symbolic Order precisely this lack? Isn’t the Symbolic Order

of education demonstrably composed of students not making ‘‘… real strides in raising

behaviour and academic standards…’’? In Lacanian terms, what appears to be occurring is

the exile of that which is, namely the lack that has just been described, as the Other of the

subject, in favour of a misapprehension of the subject, namely the inclusion of ‘pupil

voice’; and it is through the apprehension of this little other, ‘pupil voice,’ the objet petit a,

that the subject of education (mis)apprehends what it means for it to be.

In response, then, to the question that we opened with—what is the subject—an answer

might be, the subject is the claim that it is that which it is not, namely a lack, which, as we

have already seen, is for Lacan the locus of desire. A Habermasian response to this

Lacanian understanding of ‘pupil voice,’ which is an understanding of misrecognition and

exclusion, might be, pragmatically: let us put this business of the gaze to one side, what we

are still able to derive from ‘pupil voice’ is a hollowing out, a space between, that is more

democratic, more essential, closer to a sense of the authentic life world of the classroom,

than the techno-bureaucratic dimension of education might allow. And we have to ask at

this point, politically, would this be so? Would this involve a shift in the constitution of the

Symbolic Order? It is tempting to think, yes:

As Anna aged ten, points out ‘‘our pupil voice project is going to help our education,

our environment and help other schools’’. The children who contributed to this article

were inspired by the belief that their views matter and will make a difference. Clare

notes how important it is ‘‘to have your voice heard… because it ‘‘makes you feel

free’’. However, she reminds us that ‘‘it is a big responsibility for teachers to make

children have good futures’’ (Peacock 2001, p. 53).

Would it be churlish to suggest that the Symbolic Order has not changed? Would it be

churlish to suggest that Anna and the other children who have contributed to this article

were already part of the identity of the school, and that all that has happened is that this

identity has been confirmed by a misapprehension, and that this is what ‘‘makes you feel

free,’’ the very fact that you are not free? Would it be churlish to note that this rationalism

Habermas, Pupil Voice, Rationalism, 179

123

of observing the self observing the self is about reproduction rather than transformation, as

education misconceives? Or is it more propitious to throw in our lot with a Habermasian

rationalism that sees ‘pupil voice’ as a kind of romantic quest for the authentic life world,

as a space that is critically, historically, eked out between the drive towards techno-

bureaucratic improvements?

Conclusions

Pupil voice offers an easy target for knee-jerk criticism from those concerned with

declining discipline, an issue sometimes laid at the door of pupil power with its blurring of

the boundaries of authority in the classroom. Pupil voice can also be seen as a ridiculous

notion in the context of an institution that is dedicated in part to the management and

control of children. But perhaps more significantly, pupil voice is a symptom of education;

or, rather, in Lacanian terms, misrecognition, a symptom of what education is not. In this

sense, pupil voice signifies a lack, a hole within the Symbolic Order filled with the desire to

be; and in this case, the desire to be constituted by democratic, inclusive practice. Is this

then a way of understanding education more generally? Does pupil voice offer us a telling

reflection of what education is not, as it catches itself in the circuit of its gaze constituting

itself where it cannot be? Surely the most important point, however, is not that this kind of

debate is resolvable, one way or another; this would be a rather different, rather more naive

form of misconceiving than that associated with the theory of the objet petit a, to throw in

one’s lot definitively with either Habermas or Lacan. Surely the more important point is

that theoretical perspectives, and often theoretical perspectives that are incongruent, help

us to understand that policy, be it in the domain of education or elsewhere, is never framed

innocently. That is to say, policy always tells a story, but a story on behalf of someone, or

some group, a story that the subjects of that policy often cannot tell for themselves. Pupil

voice is simply one example of this. Policy therefore represents, or claims to represent, in a

privileged and exclusive place; it stands in for, speaks on behalf of, articulates desires of

one sort or another; and it does all of this, inevitably, for politically interested ends.

Theory, Lacanian or Habermasian, is simply a way of getting to know: who is speaking and

which interests their discourse serves; and also, as with pupil voice, how such an act of

ventriloquism works.

References

Best, S. (1995). The politics of historical vision: Marx, Foucault, Habermas. NY: Guilford Press.Blaug, R. (1999). Democracy, real and ideal: Discourse ethics and radical politics. Albany, NY: SUNY

Press.Braaten, J. (1991). Habermas’s critical theory of society. Albany: SUNY Press.Calhoun, C. (1995). Critical social theory: Culture, history and the challenge of difference. Cambridge,

MA: Blackwell.Cox, S., & Robinson-Pant, A. (2006). Enhancing participation in primary school and class councils through

visual communication. Cambridge Journal of Education, 36(4), 515–532.Cremin, H., Mason, C., & Busher, H. (2011). Problematising pupil voice using visual methods: Findings

from a study of engaged and disaffected pupils in an urban secondary school. British EducationalResearch Journal, 37(4), 585–603.

Descartes, R. (1637). Discourse on method, optics, geometry, and meteorology. Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press.

Descartes, R. (1644/1984). Principles of philosophy. New York: Springer.

180 P. Moran, M. Murphy

123

Deuchar, R. (2009). Seen and heard, and then not heard: Scottish pupils’ experience of democratic edu-cational practice during the transition from primary to secondary school. Oxford Review of Education,35(1), 23–40.

Habermas, J. (1962). Structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeoissociety (T. Burger & F. Lawrence, Trans., 1989). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Habermas, J. (1979). Communication and the evolution of society. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.Habermas, J. (1984). The theory of communicative action (Vol. 1). Cambridge: Polity Press.Kirshner, L. A. (2005). Rethinking desire: The Objet Petit A in Lacanian theory. Journal of the American

Psychoanalytic Association, 53(1), 83–102.Lacan, J. (1986). The four fundamental concepts of psycho-analysis. Middlesex: Penguin.Lundy, L. (2007). ‘Voice’ is not enough: Conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations convention on

the rights of the child. British Educational Research Journal, 33(6), 927–942.Murphy, M., & Fleming, T. (2010). Communication, deliberation, reason: An introduction to Habermas. In

M. Murphy & T. Fleming (Eds.), Habermas, critical theory and education. New York: Routledge,pp. 3–16.

Payne, M. (2007). Foreign language planning: Pupil choice and pupil voice. Cambridge Journal of Edu-cation, 37(1), 89–109.

Peacock, A. (2001). Listening to children. Forum for promoting 3–19 comprehensive education, 43(1),19–23.

Rudduck, J. (2003). Consulting pupils about teaching and learning: Process, impacts and outcomes.Available on the Regard research database, http://www.regard.ac.uk/regard/home/index_html.

Sciulli, D. (1992). Habermas, critical theory and the relativistic predicament. Symbolic Interaction, 15(3),299–313.

Sellman, E. (2009). Peer mediation services for conflict resolution in schools: What transformations inactivity characterise successful implementation? British Educational Research Journal, iFirst Article,1–16.

Steele, M. (1992). The ontological turn and its ethical consequences: Habemas and the post-structuralists.Praxis International, 11(4), 428–447.

Taylor, C., & Robinson, C. (2009). Student voice: Theorising power and participation. Pedagogy, Cultureand Society, 17(2), 161–175.

Thompson, P. (2009). Consulting secondary school pupils about their learning. Oxford Review of Education,35(6), 671–687.

Thomson, P., & Gunter, H. (2006). From ‘consulting pupils’ to ‘pupils as researchers’: A situated casenarrative. British Educational Research Journal, 32(6), 839–856.

Whitehead, J., & Clough, N. (2004). Pupils, the forgotten partners in education action zones. Journal ofEducation Policy, 19(2), 215–227.

Habermas, Pupil Voice, Rationalism, 181

123