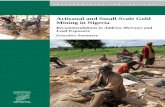

Guidance Note on Formalising Artisanal Mining Activity

Transcript of Guidance Note on Formalising Artisanal Mining Activity

Guidance Note on Formalising Artisanal Mining Activity

Final report

BRGM/RP-54563-FR November, 2006

Guidance Note on Formalising Artisanal Mining Activity

A global review and comparative analysis of mining codes and policy approaches towards Artisanal and Small-scale Mining

Final report

BRGM/RP-54563-FR November, 2006

Study carried out as part of CASM-BRGM Research Project

R. Pelon, B. Martel-Jantin

Checked by:

Name:

Date:

Signature:

Approved by:

Name:

Date:

Signature:

If the present report has not been signed in its digital form, a signed original of this document will be available at the information and documentation Unit (STI).

BRGM’s quality management system is certified ISO 9001:2000 by AFAQ.

Keywords: Artisanal Mining Activity, Mining Code, Policy approach, Small-scale mining. In bibliography, this report should be cited as follows: Pelon R., Martel-Jantin B. (2006) – Guidance note on Formalizing Informal Artisanal Mining Activity. A global review and comparative analysis of mining codes and policy approaches towards Artisanal and Small-scale Mining. Final report. BRGM/RP-54563-FR. 86 p., 2 fig., 8 tabl., 1 app. © BRGM, 2006. No part of this document may be reproduced without the prior permission of BRGM.

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report 3

Synopsis

Ce rapport est le résultat d'un projet de recherche réalisé en 2005 et cofinancé par le CASM (Community and Artisanal and Small-scale Mining: www.casmsite.org) et le BRGM.

Pour le BRGM, ce travail se situe dans le prolongement des travaux sur la mine petite et artisanale entrepris depuis 2001. La dimension de recherche dans ce domaine a pour ambition de mettre l'expertise de l'établissement au service du développement durable par: l'identification des bonnes pratiques, la formulation de guides de recommandation et ultimement la conception de modèles de développement du secteur.

Suivant la philosophie actuelle des institutions internationales, les projets de développement de la mine petite et artisanale (MPA), en anglais Artisanal and Smallscale Mining (ASM) doivent désormais prendre en compte non seulement les aspects technico-économiques et socio-économiques mais encore les aspects "gouvernance".

La bonne gouvernance, par définition la "science de l'établissement des règles", fut d'abord prônée, par la Banque Mondiale notamment, dans la perspective d'une meilleure gestion de l'aide internationale et des fonds alloués au développement. Par extension, elle est maintenant recherchée dans la gestion des fonds alloués par les états eux-mêmes au développement. Le concept qui valait pour l'aide internationale vaut désormais pour les politiques nationales.

Dans le secteur des ressources minérales, bon nombre d'échecs en termes de développement sont imputés, souvent de manière schématique, à une "mauvaise gouvernance". Les solutions sont recherchées dans l'étude et la caractérisation de ce que pourrait être la bonne gouvernance dans la gestion des ressources. Pour ce qui est de la MPA, les conclusions de nombreuses études se rejoignent sur cette condition sine qua non d'un développement durable: la définition d'un cadre légal approprié et la formalisation du secteur.

Le partenariat BRGM - CASM avait donc pour but de répondre à la question: peut-on caractériser les composantes d'une loi qui serait favorable à la formalisation de la MPA? L'intention n'est clairement pas de dicter les termes d'un code minier idéal valable partout et universellement favorable à la formalisation. Il est évident que les situations sont extrêmement diverses à travers le monde. Il est évident en outre que les dispositions légales relèvent in fine de l'appréciation et de la responsabilité du législateur. L'idée d'une "guidance note" - c'est-à-dire une note d'orientation, ou un guideline à destination de tous ceux qui sont amenés à étudier, à établir ou à réviser une loi - est plutôt de formuler un ensemble intégré de recommandations qui peuvent servir comme une "boîte à outils".

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

4 BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report

Pour tenter d'identifier comment prendre en compte la MPA dans les lois minières en vue de favoriser la formalisation, nous avons d'abord établi le contexte de ce qu'on appelle l'informa lité. Nous avons ensuite retracé l'évolution historique de la prise en compte légale ou réglementaire de la MPA, avant d'émettre des recommandations. L'analyse comparative des codes miniers dans les pays en développement irrigue l'ensemble du rapport et est résumée en annexe.

Les recommandations finales sont établies suivant deux méthodes opposées. Une approche bottom-up dresse un état des lieux des titres miniers (Iicensing system) - excellents révélateurs de l'esprit de la loi. Une approche top-down établit un modèle théorique de représentation des populations artisanales. Il constitue une approche synthétique et novatrice du processus de formalisation de la MPA basé sur le développement des communautés.

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report 5

Contents

1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ 9

1.1. BUILDING APPROPRIATE LEGAL AND REGULATORY FRAMEWORKS FOR ASM .......................................................................................................... 9

1.2. FORMALIZING ASM AND MILLENNIUM DEVELOPMENT GOALS ............... 10

1.3. A GUIDANCE NOTE FOR ASM: METHODOLOGY ........................................ 10

2. Background .......................................................................................................... 13

2.1. WHAT IS INFORMAL ECONOMY? ................................................................. 13

2.2. WHY IS ASM SO GENERALLY AN INFORMAL ACTIVITY? ........................... 14

2.3. WHY DOES ASM NOT EVOLVE SPONTANEOUSLY TOWARDS FORMALIZATION? ......................................................................................... 15

2.4. WHAT ARE THE MAIN VIEWS JUSTIFYING ASM FORMALIZATION POLICIES? ...................................................................................................... 16

2.5. WHAT FUNDAMENTAL DILEMMAS ARE INHERENT TO ASM POLICIES? .. 17

3. Trends in and principles behind legal efforts towards ASM formalisation ...... 19

3.1. THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF THE LEGAL CONSIDERATION OF ASM .. 19

3.1.1. The 1960's and 1970's: a period of non-recognition......................... 19

3.1.2. The 1980's: a period of segregation ................................................. 20

3.1.3. From 1990 on: a period of integration .............................................. 21

3.2. GENERAL SPECIFICATIONS FOR A MODERN ASM LAW ........................... 25

3.2.1. The environment ............................................................................. 25

3.2.2. Decentralization ............................................................................... 27

3.2.3. Community rights ............................................................................ 28

3.2.4. Marketing ........................................................................................ 29

3.2.5. Taxation .......................................................................................... 30

3.2.6. Conflicts .......................................................................................... 31

3.2.7. Child Labor ...................................................................................... 32

3.2.8. Gender issues ................................................................................. 33

3.2.9. Health and safety ............................................................................ 34

3.2.10. Control............................................................................................. 35

4. Recommendations on ASM licensing with a view to formalization ................. 37

4.1. A TYPOLOGY OF EXISTING ASM LICENSES ............................................... 37

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

6 BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report

4.1.1. Questions of definition ..................................................................... 38

4.1.2. Research and prospecting licenses ................................................. 39

4.1.3. "Undocumented" licenses ................................................................ 40

4.1.4. Claims ............................................................................................. 41

4.1.5. Artisanal licenses ............................................................................. 42

4.1.6. Small-scale mining licenses ............................................................. 45

4.1.7. Concession ...................................................................................... 50

4.1.8. Designated areas ............................................................................ 51

4.2. A COMMUNITY -DRIVEN APPROACH TO FORMALIZING ASM ................... 54

4.2.1. The three-level scheme ................................................................... 54

4.2.2. The formalization of Level 1: artisans within "communities" ............. 57

4.2.3. The formalization of Level 2: artisans within "settlements" ............... 58

4.2.4. The formalization of level 3: artisans within "enterprises" ................. 60

4.2.5. Conclusion ....................................................................................... 62

5. Conclusions .......................................................................................................... 65

6. References ............................................................................................................ 67

List of figures

Figure 1: The vicious circle of informality (from MMSD, 2002) .................................................... 16

Figure 2: A community-driven approach to ASM formalization: a conceptual diagram .............. 62

List of tables

Table 1: ASM formalization objectives and MDG's (after CASM, 2005 and Priester, 2005). ........................................................................................................................................... 10

Table 2: Evolution of the development community's approach to ASM (after MMSD, 2002). ........................................................................................................................................... 19

Table 3: The main international meetings ................................................................................... 22

Table 4: Reference mining laws for ASM .................................................................................... 23

Table 5: A comparison of different artisanal mining license provisions ....................................... 44

Table 6: Comparison of different small-scale mining license provisions ..................................... 46

Table 7: Characterization of the three levels of ASM .................................................................. 55

Table 8: Recommendations for the three levels of ASM ............................................................. 62

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report 7

List of appendix

Appendix 1 Countries Reviewed ................................................................................................. 71

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report 9

1. Introduction

1.1. BUILDING APPROPRIATE LEGAL AND REGULATORY FRAMEWORKS FOR ASM

Most attention in the mining industry has been focused on large companies. But in many parts of the world, particularly in developing countries, minerals are extracted by artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) - by people working with simple tools and equipment. The vast majority are very poor, exploiting marginal deposits under harsh and often dangerous conditions - and with considerable impact on the environment. A large proportion of them work in the informal sector, outside any legal and regulatory framework.

In some instances (MMSD, 2002), small-scale miners have a legal title to the land that they work that is recognized by the state and others. In others, the artisans work land they have traditionally inhabited, but without any recognition of land rights from the state, and they may be regarded as illegal squatters by local and state authorities. In extreme cases, governments consider the sector illegal and attempt to ban it by different means. In other instances, since ASM falls outside the regulatory framework, this mining population tends to be neglected by governments. In yet others, governments are willing to avoid aggravating the already negative social and environmental impacts and, on the contrary, want the sector to enter a virtuous circle of development which begins with the initiation of a formalization process.

Indeed, there is a real consensus, internationally, over the need to establish regulations and legislation for ASM formalization. The MMSD process identified "building appropriate legal and regulatory frameworks" as a priority action (MMSD, 2002). In the same line, the 1995 International Roundtable on Artisanal Mining concluded that none of the challenges facing the ASM sector could be overcome until a prime need was met: legal titles (Barry, 1996). This is to say that it is increasingly accepted that the first step towards improving ASM situations is to make the legislative framework more appropriate or effective.

ASM formalization policies contribute to four strategic objectives: alleviating poverty and contributing to integrated rural development, avoiding or minimizing environmental and health impacts, achieving a productive business climate, and stabilizing government revenue.

More specific justifications given for the legislative effort include (Bugnosen, 2001):

- curbing illegal mining and illegal trading or smuggling of metals and mineral products;

- stopping the supply of go Id to the black market;

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

10 BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report

- addressing environ mental destruction generally, or specific environmental concerns such as the erosion and silting up of water courses, as in the case of the Zimbabwe Mining Alluvial Gold Public Streams Legislation;

- developing and exploiting small existing mineral deposits;

- generating more employment opportunities, thereby alleviating living conditions in rural areas; generating additional foreign exchange earnings;

- protecting and rationalizing viable small-scale mining activities;

- providing mechanisms for collecting government revenues from the operations; controlling the miming rights of cultural minorities within their ancestral lands.

1.2. FORMALIZING ASM AND MILLENNIUM DEVELOPMENT GOALS

ASM formalization objectives are not only crossing national reasons but they are also meeting international rationales deriving notably from the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDG).

Several of the MDG are closely related to topics and issues relevant for ASM. An analysis during the CASM conference on the Millennium Development Goals and Artisanal Mining held in June 2005 demonstrated that ail eight MDG's possess direct links with the problems and opportunities typical of ASM.

Table 1: ASM formalization objectives and MDG's (after CASM, 2005 and Priester, 2005).

ASM formalization objectives Millennium Development Goals

Break the vicious circle of poverty-driven ASM MDG 1. Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger Allow legal conditions for viable activities

Promote upgrading of ASM activities MDG 8. Develop a global partnership for development Support technical-economic improvements

Management of mineral resources; conservation and/or sustainability

rehabilitation of water, land, fauna & flora resources

MDG 7. Ensure environmental

Fight diseases and accidents in ASM zones

MDG 6. Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases

MDG 5. Improve maternai health

Manage conflicts between LSM and ASM MDG 8. Develop a global partnership for

development

Protect traditional communities' MDG 2. Achieve universal rights primary

education

Promote gender equality MDG 3. Promote gender equality and

empower women

Ban child labor on ASM workings MDG 4. Reduce child mortality

1.3. A GUIDANCE NOTE FOR ASM: METHODOLOGY

Although it has been possible to identify international best practices and to formulate precise recommendations regarding LSM, the problem is more complicated for ASM,

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report 11

as situations are visibly less comparable. Game rules are quite clear for the LSM sector, which has recognized and audible spokesmen: the industry itself, forthright about the ideal conditions for substantial investment in a developing country1. The industry is generally in unison because the private interests of a" of the "majors" converge over the framework of a single mineral law.

Regarding ASM, situations are far more heterogeneous worldwide. Operators are diverse and sometimes incapable of speaking out with one voice. What's more, information on ASM often lacks precision due to the activity's obscure nature. National contexts are accordingly more difficult to benchmark.

However, it is the role of Guidance Notes to contribute to the ability of governments to understand the needs of artisanal miners, who are usually not represented within the governing group of the society. This is actually the ultimate objective of this Guidance Note, to provide reflections, illustrations and recommendations to all those who are involved in legislative reforms devoted to ASM formalization.

We have had to opt in favor of a methodology that takes those limits into account. We will try therefore to bear the following statements in mind:

- Formalization is a process that takes time and effort: no miracles are to be expected, and there are no quick fixes. The reflections, illustrations and recommendations that will be found in this Guidance Note cannot be definitive.

- This Guidance Note does not purport to enter deeply into judicial issues regarding appropriate legal framework for ASM. The purpose of our work is to formulate general recommendations inspired from a global comparative analysis and from experience gained in the field by experts in various areas of specialization.

- The scope of the study is global, and hopefully it will prove useful as a first approach anywhere in the world. But because of the authors' experience and available documentation, particularly in view of the acuteness of the problem in Africa, special focus is on that continent.

- ASM challenges concern many kinds of minerals worldwide. The accent will be put on precious metals and gemstones even if situations concerning industrial minerals or coal are evoked and can be quite similar in terms of formalization.

We have chosen to conserve the unavoidable redundancies that will be found from one chapter to another, so that they retain an independent character.

Chapter 2 furnishes the necessary background material so that an understanding of the stakes and challenges involved in the formalization processes may be obtained. Chapter 3 presents the trends and principles behind legal efforts towards ASM formalization. The general specifications for a modern ASM law will be set forth briefly following a rapid overview of the historical context of legal considerations concerning ASM. A global analysis of mining codes is ever-present in this study, and the review of

1 For instance, Rio Tinto has been publishing notes on what it considers a good mining code.

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

12 BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report

the countries examined is reported in the Appendix. Each country's case study outlines features of ASM laws with respect to formalization: the importance of ASM in the country, the political and legislative context, the main features of ASM laws, and some issues and successes.

All that material has fed into Chapter 4, which brings together recommendations on ASM Iicensing with a view to formalization. Two complementary steps have been chosen for that purpose: a bottom-up approach, which consists in the critical description of a typology of existing ASM licenses, and a top-down approach based on the principles of Community-Driven Development (COD).

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report 13

2. Background

Artisanal and Small-scale Mining (ASM) is an economic activity that is very largely informal, notably in Africa, where it concerns a population of millions. The reasons behind this informal character are of an historical, geographical, economic and legal order. For the most part, it is prejudicial, but a certain degree of tolerance is the rule with regard to an activity that is often involved in survival strategies. However, moving on from informal to formal does not just happen spontaneously: it must be stimulated, given impetus to, by the entity that provides the "form" in question, namely the State. Thus formalization is indisputably a political and legislative issue - one extending far beyond the mining sector. Two courses of action may logically contribute to increasing the formal proportion of the small-scale mining activity: either attracting a larger number of economic units into the existing formal framework, or enlarging the framework itself. The pertinence and the chances for success of one or the other of these two orientations depend upon how closely law conforms to reality and on the State's law-enforcement ability. This intersection between the empirical situation and political ambition may coincide with a reform of the mining code that deals with ASM aspects. A thorough examination of the possible and desirable clauses for these mining codes makes it possible progressively to identify the most appropriate practices in the area.

2.1. WHAT IS INFORMAL ECONOMY?

The extent and complexity of the informal part in the economic, social and political life of developing countries are such that it is difficult to characterize it in a simple and general manner. The highly diverse local situations render the analytical categories of legality and informality quite relative. There are those who go so far as to see, in the varied meanings of the term, the reason for its popularity: "the term has really caught on precisely because of its lack of precision" (Lautier, 2004).

Yet the Fifteenth International Conference of labor statisticians had defined the informal sector as "a group of units producing goods and services mainly with a view to generating jobs and revenues for the individuals concerned. They are loosely organized, operate on a small scale, with little if any separation between labor and capital as production factors. (...) The activities are not necessarily conducted with the deliberate intention of evading taxation or of violating labor laws or other administrative provisions" (Maldonado, 1995).

This definition, though generally accepted, is nevertheless theoretical. Empirically, the term is often restricted to a specific sector, labeling more or less as "formal" that portion of the sector directly characterized by statistics and the remainder, what is known to exist and the scale of which can be inferred, but not directly quantified, as "informal".

Over the past ten years, the "hidden side" of the national economy has been observed in a fair number of countries. According to the International Labor Organization (lLO), the informal portion of non-farm labor accounts for some 55% in Latin America,

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

14 BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report

between 45% and 85% in different regions of Asia and nearly 80% in Africa (ILO, 2002). Thus in most of these countries, the informal economy paradoxically represents the "norm".

Interpretations concerning this phenomenon are varied and even occasionally contradictory. For some, the informal economy is, so to speak, a precursor stage to the formal economy, and it is development that will enable the economic units to move gradually from one status to the other. The informal economy, here, is the invisible part of the iceberg, and politically it must be encouraged to surface.

For others, the informal economy is a logical, even rational, response to a legal situation that is unsuitable, or dysfunctional. Indeed, the proponents of economic neo-Liberalism (De Soto, 1994) insist on the influence of legislation on the level of economic efficiency it governs, suggesting the pre-eminence of legal instruments. Loosely speaking, the economic players deliberately elect to avoid being publicly declared whenever the opportunity cost of the formal sector (taxes and fees, administrative delay and red tape...) exceeds that of the informal one (Iack of access to financing, to training...).

But whether the causes have to do with an unfavorable structural context (a sluggish economy, a hostile environment...) or an unsuitable institutional system (too little information, a negative image of the law...), what does emerge as being central to informality is how the citizenry relates to the State: "Relationship with the State stands behind the very definition of informal economy, since the form that is lacking is the one the State is supposed to impose" (Lautier, 2004). The question is then to discover why it does not impose it, whether because of the internal organization of economic activities (compliance with the labor law, with product standards...), the visibility of these activities (enrolment on the various registers) or their contribution to socialized expenditures (taxes, tees, social contributions).

2.2. WHY IS ASM SO GENERALLY AN INFORMAL ACTIVITY?

The case of the mining sector lends itself particularly well to the formal/informal dichotomy. In most mining countries where the activity of exploiting mineral resources goes significantly beyond the mere use of rocks and industrial minerals for domestic needs, three modes of mining activity are found to coexist. The first, stated simply, is a concentrated, capital-intensive mining industry with a small labor force, demanding in terms of technology and qualifications, having sizeable permanent facilities, legal, visible, and accordingly formal: "large-scale mining" (LSM). The second, conversely, is a dispersed mining activity that is labor-intensive but poor in capital, relying on very basic means, often intermittent, not very official and at times even illegal, in a nutshell, largely informal: artisanal mining. Intermediate between these two extremes lies "small-scale mining" (SSM), more or less well localized and mechanized, and that oscillates between formal and informal according to resources and the country involved. The process of defining and delimiting these two categories is liable to be tricky (and a determining factor) in the analysis and orientation of formalization policies, but we should already bear in mind that there are few sectors for which such clear-cut divisions can be drawn.

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report 15

The reasons behind informality lie both in the legal framework and the economic sector. The largely informal nature of artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) can derive from many intrinsic causes. In some instances, informality may be a result of culture. In certain countries like Mali, the artisanal exploitation of mineral resources has remained unchanged for centuries. The activity is actually rural and community-based, often remote from infrastructure centers, hence poorly visible and controllable. With custom sometimes carrying more weight than written law, exploitation is conducted using age-old methods that may be contrary to administrative or legal regulations but have the advantage of precedence.

When artisanal exploitation of mineral resources is not a tradition, it is often an activity engaged in failing ail else. In extreme economic contexts where no other alternative is viable, populations turn to Earth's resources as a last resort. For those who, for land-ownership or climatic reasons, cannot farm, the only remaining option, as a last means of survival before abandoning the land, is the exploitation of subsurface resources. The fact that it is possible to excavate, to crush, to grind, or to transport ore with minimum technical means fosters informality (little training and little investment needed).

Likewise, the migratory nature of this seasonal or transient, low-paying artisanal activity tends to dissuade from official declaration, which would presuppose a modicum of stability and prosperity.

ASM is further broadly subdivided into two categories: the extraction of building materials (aggregates, clay, lime...) and industrial minerals (feldspar, gypsum, salt...) for local use, and the extraction of precious substances (gold, diamonds, gems...), which are generally exported either via national agencies or as contraband. The former are used more or less on the spot because of their low worth per mass unit, while the latter are frequently light-weight or compact: in both cases, they are not very visible when transported.

Lastly, as to potentially more rapidly profitable precious mineral resources, rivalry, haste during rushes, the feverish and superstitious quest for the "salutary nugget," or smuggling, contribute still further the activity's furtive and resolutely underhanded character.

2.3. WHY DOES ASM NOT EVOLVE SPONTANEOUSLY TOWARDS FORMALIZATION?

All this is not conducive to the sector's contributing to Sustainable Development. Artisanal miners, who often brave hazardous health and safety conditions that are a direct threat to them, have other priorities than standing up for environmental protection or other long-term perspectives. They generally receive no state benefits and by the same token pay little tax or royalties. They do not always have legal authorization to operate and are easily at odds with landowners or holders of mining concessions.

The connection between the informal economy and poverty is clear. Most informal workers are confronted with both less opportunity and a higher level of risk than their counterparts in the formal sector. They have less access to the formal sources of

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

16 BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report

financial support. They are more vulnerable to illness or to material prejudice, since they are covered neither by health care nor by insurance. The miners are subject to more professional risks and are doomed to have no job security.

Furthermore, instead of gradually progressing towards formalization, most of the time ASM remains trapped in a vicious circle of non-development that has often been described.

Figure 1: The vicious circle of informality (from MMSD, 2002)

Rarely does ASM spontaneously abolish this process; left to its own devices, the ASM sector seems to be doomed to remain in poverty. Some are convinced that governmental action is generally ineffective, creating distortions, and that economic growth will bring about the decline of the informal economy, or else that this latter is beyond the reach of the authorities. In the case of ASM, it is nevertheless very unwise to take for granted that the informal economy is something that, given time, will pass away; experience shows henceforth that ASM does not spontaneously go formal. The need for state intervention, if not already demonstrated, would be further justified by ASM's potentially very damaging impacts.

It is increasingly accepted that policies, legislation and regulations must be established for the purpose of correcting existing distortions and setting the economy on the path to Sustainable Development.

2.4. WHAT ARE THE MAIN VIEWS JUSTIFYING ASM FORMALIZATION POLICIES?

In the sixties and seventies, ASM was often perceived as diametrically opposed to the development of LSM and to the industrialization principle as a whole. The newly independent nations, having finally regained control over their natural resources, were fully resolved to take part in international exchanges while playing up their own competitive advantages. Exporting raw materials was in some cases a political priority

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report 17

that nothing could be allowed to hinder. ASM was accordingly declared illegal, and the political effort consisted in striving to get rid of it.

Progressively it came to be recognized, however, that the resources concerned by LSM were not necessarily the same as those involved in ASM: low-tonnage but high-grade resources may not prove economically viable for an international investor while still representing a resource well suited to small-scale exploitation. The informal economy began to be viewed more optimistically, as a driving force for economic development: it represented a breeding ground for mini-enterprises destined to graduate to a higher, and legal, status in virtue of a process known as formalization.

This notion was based on the postulate that the enterprises would modernize, develop, and eventually become legally registered, maybe with assistance provided from the outside and given concrete expression through financing or training. Formalization policies were therefore going to focus on enhancing productivity by granting funding (the purchase of capital equipment) and raising the technical level by setting up training programs (technology transfer or technical assistance). More pragmatically yet, it was henceforth admitted that seeking to eradicate artisanal mining would be a vain effort. The sector is a fact of life, directly employing vast numbers of workers and supporting millions planet-wide. Without going so far as to encourage its propagation, the approach was thus to place ASM in a proper framework while at the same time controlling it.

Moreover, towards the end of the 1980's, there was a turnabout in thinking concerning the informal economy. Since formal employment declined while informal employment kept rising, the idea of a possible substitution began to be accepted. The informal sector, albeit decidedly not very productive, did nevertheless ensure an essential social function: thus it was above ail up to the informal economy to generate jobs and revenues, even very low and nontaxable ones. With this in mind, formalization policies were expected not only to combat the informal, but also to assist the concerned communities in their development.

2.5. WHAT FUNDAMENTAL DILEMMAS ARE INHERENT TO ASM POLICIES?

Formalization policies must take on the sometimes blatant contradictions between developmental priorities and ones designed to combat poverty. They are in general caught up in the "non-structured sector dilemma" (Hansenne, 1991): should efforts be made to apply the regulations and social protection provisions in force to the informal sector and risk taking restrictive actions, thereby reducing its capacity to sustain a constantly growing work force or, on the contrary, should the sector be encouraged on the pretext that it generates work and revenues?

In the case of ASM, this dilemma shows up in the two main currents that guide the policies seeking to formalize it: a first consisting in attracting a larger number of miners into the formal framework through incentives and repressive provisions and a second in broadening this framework, even if this entails a reform of the mining code, for example.

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

18 BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report

In the first instance, the results depend on the State's capacity to intervene. Its ability to define and enforce socially acceptable standards governing economic activity goes far beyond the scope of a specific sector such as ASM: it is a fundamental political issue, basic to the State's ambitions of modernity and progress. In the second approach, the results depend on what level of tolerance towards ASM is deemed desirable or acceptable. Whatever the case, the conversion, the structuring, the "formalization" of the informal economy is contingent upon the State's restoring regulation over economic relations as a whole.

But to what extent is this possible? The informal sector has often grown precisely because of the State's inability to control. With respect to taxation, for example, some maintain that the State is structurally incapable of imposing taxation on certain economic activities... This argument, however, is only pertinent to a limited degree: the cost of controlling is always theoretically lower than the revenues it brings in, under one condition - that the taxes taken in do indeed wind up in the coffers of the State. The State's capacity to take charge of the ASM sector to best avail, in this sense, accordingly comes down to the much-debated issue of governance. International institutions, NGO's, but also the major players of the mining industry, have come to realize this and are striving, in a series of studies and initiatives, to define and bring about the conditions for such good governance of mineral resources.

A certain level of tolerance towards the ASM sector is appropriate, but when the informal sector accounts for a preponderant proportion of the activity, the State must assume its responsibilities. It cannot unconcernedly allow a substantial portion of the economy to evolve unsupervised without discrediting itself. The activity as it is should not be developed, but rather be transformed, be made professional, be formalized, in order to fight poverty. Succinctly, a nation that purports to be committed to poverty reduction and that happens to have a substantial portion of its work force engaged in ASM has the obligation to take charge of it policy-wise. It was the ambition of the Yaoundé (Pedro, 2003) meeting in 2002 to establish this relation, and accordingly to put pressure on the concerned nations to include ASM in the poverty Reduction Strategic Papers.

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report 19

3. Trends in and principles behind legal efforts towards ASM formalisation

Mining law development has always reflected two principal and sometimes contradictory) goals (Williams, 2005): state control over the rent from resources, on the one hand, and control of this rent at the initiative of the free miners, on the other. Reforms of mining law in the post-World War II era were inclined to give more weight to the first goal, tending to focus on bringing the relatively prosperous mining industry under the control of government in order to achieve policy objectives in the areas of fiscal revenue generation, employment, technology transfer, and regional and global development. The results were in most cases disappointing and not sustainable, prompting a shift towards the second of the two competing goals.

These basic trends have determined political and legislative attitudes towards ASM. With variations (in time and degree) between the developing regions, thinking concerning ASM has evolved from a sector to ignore or to ban into an activity to manage in a holistic manner by means of comprehensive legal regimes.

Table 2: Evolution of the development community's approach to ASM (after MMSD, 2002).

Date Period Approach

1960's and 1970's

Non- recognition

period Definitional issues

1980s Segregation

period Technical issues

From1990 Integration

period

Early1990's: Towards integration of technical, on Environmental, legal, social and economic Issues. Mid- to late 1990's:

Relationship between large mining companies and ASM. Gender and chi d labor Issues. 1990's: Special attention given to

legalizing ASM sectors. Since 2000: Community-related issues and sustainable livelihoods.

3.1. THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF THE LEGAL CONSIDERATION OF ASM

3.1.1. The 1960's and 1970's: a period of non-recognition

The period prior to the 1960'5 is generally considered as a true artisanal era, when most mining of minerals and metals was carried out by individuals who had no recognition from the relevant authorities. In colonial African for example, artisanal mining, while largely illegal, was at the same time limited to local and traditional activities.

ln 1962, the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 1803 XVIII proclaimed the principle of each country's permanent sovereignty over its own natural resources

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

20 BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report

(Bastida, 2002). That principle of international law, which began at that time as a political claim on the part of the States formerly designated as "under-developed countries," was soon to become, in the New International Economic Order, an asserted orientation by the new ex-colonial countries demanding recognition of their right to participate in the development of their own natural resources and the benefits accruing from their exploitation. This was reflected through increased control of the states over their natural resources as a means for achieving economic development and a fair apportionment of their profits and powers in partnership with the industrialized world. The development of these resources was indeed intended to provide financial resources for development, and this was considered as a "springboard for industrialization." ln such a model, little room was left for ASM in mining policy. The main effort of the time was to develop public enterprises to run the economy and pervasive regulation for private enterprises.

The United Nations first use of the term "Small-Scale Mining," appearing in a 1972 report, had a rather negative connotation, insisting on skimming and health and safety issues.

3.1.2. The 1980's: a period of segregation

"The pendulum from strongly orientated state-centered policies started to swing back in the 1980's" (Bastida, 2002). The drop in commodity prices combined with high interest rates brought on stagnation or decline in the mining sector. The acknowledgment of disappointing development results coincided with an deterioration in the terms of trade in the early 1980's and prompted a change in direction in mineral policy.

The advent of global liberalism and the shift from government intervention to reliance on market-based systems of resource allocation from the late 1980's on have paved the way for a new generation of mineral laws and agreements aimed at encouraging foreign investment. Although differing widely from country to country, some general trends have been evident in developing countries, with a move towards replacing outdated laws and improving the efficiency of the administrative process through mineral development agreements, the reduction of governments discretional powers, improved title management, strengthened security of tenure and the enhancement of the transferability of mineral rights.

The idea emerged that, despite the drawbacks, the small mine could represent an alternative to large-scale mining development because of the flexibility offered compared to mega-projects. What's more, rising gold prices and the availability of new techniques (notably heap-Ieaching of gold extraction tailings) sparked renewed interest in the development of small industrial mines with a low level of investment. ASM was beginning to be reconsidered, but in a very specific way: this was a so-called "segregation" period (cf. Table 2).

Some international projects with a technical, productivity-linked approach were launched that attempted to support ASM in traditional mining countries, especially in Latin America and Southern Africa; these were often conducted by such institutions as GTZ (Germany), SGAB (Sweden), BGS (Great-Britain) or BRGM (France).

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report 21

This period, with its skyrocketing gold prices, was marked by a certain number of go Id rushes. These, in turn, triggered disputes between large-scale mining concerns and artisans that arose either because the artisans were extracting gold illegally on concessions belonging to the mining companies or, conversely, because there were companies that sought to obtain permits for zones already occupied by artisans. Most of the countries attempted to cope with the problem by means of "stopgap," emergency measures. Some countries, however, especially in late 1980's, did undertake to reform their mining codes with the intention of improving how gold was managed from the time it was extracted to when it was marketed. The best examples are probably Brazil, in Latin America, which reviewed its constitution and included a special article for "Garimpos" in 1988, Ghana, in Africa, with its 1989 mining law, and the Philippines for the Asia/Pacific region.

3.1.3. From 1990 on: a period of integration

The implementation of the new liberal-economy policies resulted in a major shift in investment interest towards developing countries. These began to compete to attract foreign investment, and mining companies had a much wider choice of countries to invest in. The withdrawal of the state and institutional reforms caused a "mining boom" in certain countries during the years from 1991 to 1998.

In that context, promoting ASM was much less on the agenda. Although there was a growing international consensus that ASM had to be legalized, it came under increasing scrutiny because of its environmental impacts. ASM tended to gain in importance because of increasing economic insecurity, an indirect result of rapid globalization, but the rise of this sector was rarely accompanied by formal development, and damage to the environment worsened due to the informal ASM operations. A number of mining codes were revised at the time that resolutely integrated the environment into the political objectives.

Since 2000, the three pillars of sustainable development have become enshrined in public discourse. The different historical models of mining development have been questioned, and the whole approach to the sector criticized (MMSD, EIR, Publish What You Pay...). The need for integration has been expressed in many forms and extended to ASM. The new slogans about institutional reform, capacity building, governance, gender and community participation convey that new philosophy devoted to alleviating poverty and eventually allowing sustainable livelihoods under a sort of "new social contract for mining" (Bastida, 2005).

Political attitudes, nationally and internationally, on ASM have thus evolved over 40 years, passing from "non-recognition" to "integration" with varying intensity and tone. Enthusiasm to promote ASM is likely to continue to swing back and forth as the sector's political image seems related to commodity price cycles. When energy costs rise or metal prices drop, it promotes the development of small-scale mining, and such seemingly rich operations are able to provide job opportunities under unfavorable economic contexts. Conversely, when precious metal prices are high, ASM becomes a preferred alternative for livelihoods. Between times, governments tend to plan "more

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

22 BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report

ambitious" policies and dream of rapid industrialization. A suitable mining code for ASM would avoid such changeable policies.

Table 3: The main international meetings

Year Meeting

1972 The UN Committee on National Resources report, "Small-Scale Mining in developing countries"

1978 UNITAR International Conference on the Future of Small-Scale Mining, Jurica, Mexico

1980 Regional Seminar, Mombassa, Kenya 1981 Conference, Taxco, Mexico

1983 Congress, Helsinki, Finland 1984 Workshop on mineral policy for SSM, India 1987 London, U.K.

1988 Meeting in Ankara, Turkey

1990 UNECA Workshop on the enhancement of the contributions of the African non-fuel mineral sectors towards the region's economic advancement, Harare, Zimbabwe

1991 International Conference on Small-Scale Mining, SMI, Calcutta

1992 Situation of SSM in Africa and development, UNECA, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 1993 UN Conference "Guidelines for the Development of Small- & Medium-Scale Mining," Harare, Zimbabwe

1995 International Roundtable on artisanal Mining, World Bank; Washington, D. C.,USA

1996 Global Conference on small-scale mining SMI, Calcutta, India

1997 Southern African Development Community Mining Sector - Five-Year Strategy 1997-2001

1997 Expert group meeting on the UNIDO high-impact project: "Introducing new technologies for abatement of global mercury pollution," Vienna, Austria

1999 Tripartite Meeting on Social and Labor Issues in Small-Scale Mines (lLO), Geneva, Swiss

2002 UNECA and UNDESA seminar on "Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining in Africa: Identifying Best Practices and Building the Sustainable Livelihoods of Communities," Yaoundé, Cameroon, 19- 22 November 2002

2002 CASM Annual General Meeting and Regional Learning Event, Ica, Peru

2003 ASM in Western Africa, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

2003 CASM Annual General Meeting and Regional Learning Event, Elmina, Ghana 2004 Small-Scale Mining Johannesburg, South Africa

2004 CASM Learning Event, Lusaka, Zambia

2004 Fourth Annual CASM AGM and Learning Event, Colombo, Sri Lanka

2005 CASM-Asia Inaugural Meeting, Bangkok, Thailand

2005 CASM-Africa Addis-Ababa, Ethiopia

2005 CASM Annual General Meeting, Salvador de Bahia, Brazil

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report 23

Table 4: Reference mining laws for ASM

Country Reference Mining Laws for ASM Date of last major

reform impacting ASM

China Mineral Resources Law of The People's Republic of China

2005 (in rev. In)

Nigeria Mining law 2005 (before the

parliament in)

Zimbabwe

Mines and Minerals Act of 1961 and a number of amendments: Statutory Instrument 275, Mining (Alluvial Gold)(Public streams) Regulations, 1991

2004(in rev. In)

Malawi Mines and Minerals Act 1982 (Cap 61.01) 2003 (in rev. In)

Cambodia Draft Mining Law of 2000 2001 (in rev. in)

Congo Draft Mining Code of 2001 2001 (in rev. in)

Congo Draft Mining Code of 2000 2000 (in rev. in)

Thailand Mineral Act 2510, 2509, 2516, 2520 and 2522, 1 2001 August 1971, revised Act 3 BE 2522,12 May

1979 (in rev. in)

Burkina Faso Mining Code, law W 031-2003 2003

Senegal Mining Code law W 2003-36 2003

South Africa Mining Titles Registration Amendment Act No. 24 of 2003

2003

Uganda Mining Act of 2003 2003

ORC Mining Code Law No. 007/2002 of 11 July 2002 2002

Mozambique Mining Law n014/2002 2002

Peru Ley de Minerla N°126 RO/Sup 695 – 1991 Ley de formalizacon y promocion de la pequana 2002 mineria artesanal No. 27451-2002

2002

ALgeria Mining Law No. 01-10 of 3 July 2001 2001

Cameroon Mining Code of 16 April 2001 2001

Colombia Mining Code, Law 685 of 15 August 2001 2001

Gabon Mining Code Law No. 51/2000 of 12 October 2000

2000

Madagascar Mining code law 99-022 1999

Mali Mining Code ordinance No. 99-032/P-RM 1999

Mauritania Mining Code law 99/013 1999

Namibia Oiamonds Act No. 13 of 1999Minerais (Prospecting & Mining) Act No. 33 of 1992

1999

Nigeria Minerals and Mining Decree of 1999 (after Mineral Act, 1946)

1999

Tanzania Mining Act of 1998 1998

Bolivia Codigo de Mineria, 17 March 1997 1997

Lao Mining Law of 12 April 1997 1997

Mongolia Mining law of 1997 1997

Philippines

PD 1150 - Gold panning and sluicing permits PD 1899 (1989) - Development of small mineral deposits (SSM permits) RA 7076 (1991) -Identification and segregation of peoples SSM mining areas (SSM mineral 1997 production sharing contract) RA 7942 (1995) - Mining Act

1997

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

24 BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report

Country Reference Mining Laws for ASM Date of last major

reform impacting ASM

AO No. 97-30 (1997) - Small-scale mine safety rules

CAR Draft Mining Law of 1997 1997

Vietnam Mineral Law of 1996 1996

Ivory Cost Mining Code, law 95-533 of 17 July 1995 1995

Guinea Mining Code, Law 95-036, 30 June 1995 1995

Myanmar Mining law No. 8/94 Gemstones Law of 1995 1995

Myanmar Mining law No. 8/94 Gemstones Law of 1995 1995

Chad Mining Code law No. 011/PRl95 1995

Zambia The Mines & Minerals Act 1995 1995

Malaysia Mining Law Act 525 29 August 1994, application 08 September 1994

1994

Sierra Leone The Mines and Minerals Act, May 1994, Statutory Instrument No. 14, 2003

1994

Ethiopia Mining Proclamation No. 52/1993 1993

Niger Mining Code Ordinance No. 93-16 1993

India Mines and minerals (Regulation and development) Act 1957 W 67, 1992 incorporating Amendment Act, 1986 Published June 1992

1992

Papua New Guinea

Mining Act 1992 1992

Sri Lanka Mines and Minerals Act No. 33 of 1992 1992

Angola Mining Law n091-24 of 6 December 1991 1991

Venezuela Mining Law of 1945 as amended on 16 April 1990

1990

Brazil

Codigo de Mineraçao, Decreto-Lei 227 de 1967, upgraded by Lei 9,314 of 1996 Constitution of 1988 (garimpos mentioned) Law No. 7805 of 1989, July 18 (for garimpos also).

1989

Guyana Mining Code Law 20-1989 1989 1989

Ghana Mineral and Mining Law of 17 July 1986 Small Scale Gold Mining Law P.N.D.C. L 218 of 1989

1989

Kenya The Mining Act CAP. 306 1972 as revised in 1987

1987

Surinam Mining Code Decree E-58 of 1986 1986

Chile Codigo de mineria Ley 18.248 of 14 October 1983

1983

Sudan Mining and oil exploration laws of Sudan, 1980 1980

Togo Mines and Career Regime Ordinance No. 35 of 18 October 1973

1973

Indonesia Mining Law No. 11 1967 Law W11/1967, Government Decree No. 32/1969

1967

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report 25

3.2. GENERAL SPECIFICATIONS FOR A MODERN ASM LAW

A mineral law is generally considered "good" when it creates a climate of stability and predictability sufficient to encourage economic and commercial activity and stimulate investment. International competition amongst developing nations for the limited number of major investors in prospecting for and exploiting mineral resources has led them to "align" their legislations in order to remain competitive. Indeed, the major players are always in a position to choose one zone over another to invest in, and their selection criteria are, of course, first geological, but also economic and legal. Ali this has given rise to an abundant literature on the question, "What constitutes a good law on minerals?", including on the part of international institutions (Naito, 2001). The criteria typically considered to be favorable are, among others, job security, clear and transparent procedures, access to resources and to currency, a stable and fair tax regime, but ail these conditions essentially concern LSM.

The situation for ASM is far more complicated. It is clearly harder to characterize what goes into the ma king of a good law for this sector because circumstances are more variable, the actors being local and very dissimilar from one country to another. Hopefully, thanks to an effort of reflection and awareness spanning many years, a general consensus can be outlined.

Thus specific ASM legislation is needed first because conventional mining codes do not deal adequately with the sector, and secondly because a reform of the code turning it into a legal framework suited to ASM represents the first step towards formalization.

Some of the main specifications for a modern ASM legislative framework are discussed below, by topic. The mining code and corresponding procedures must remain simple to ensure they work in practice, but a comprehensive law would ideally make reference to ail these aspects.

3.2.1. The environment

From the stand point of the environment, ASM-specific legislation has long been neglected owing to its impact, regarded as insignificant compared with that of LSM. But opinions have changed, and it is henceforth widely admitted that pollution due to ASM can be disastrous.

Given the scattered and informal nature of the activity, governments are unlikely to be able to raise standards immediately simply through legislation and enforcement. A realistic approach will promote awareness of the risks involved and make a case for less dangerous alternatives.

The law, in particular, should be thoroughly clear regarding the main cause to blame: mercury. If amalgamation can still not be eliminated, the regulation should optimize it, for example by restricting it to closed circuits.

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

26 BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report

The Mercury Law in Ghana

The Mercury Law was enacted in 1989 with the aim of regulating the distribution, use, storage and trading of mercury. According to this law, it is a punishable offence to import, possess, buy, sell or transfer any mercury without a license, which can be obtained from the Minister of Trade. Buying knowingly from a person who is not licensed is also a punishable offence. Small-scale miners are allowed, under the law, to buy mercury from licensed mercury dealers in such reasonable amounts as are necessary for their mining operations. A gold miner will also have committed an offence if found selling or dealing in mercury; in possession of more mercury than he needs; heating an amalgam without a retort; or if he does not observe good mining practices in the use of mercury.

Similarly, goldsmiths and gold dealers will have committed an offence if found processing mercury containing gold-sponge or metals without using a retort or if they do not observe best practices in the handling of mercury. Any person found guilty under this law shall on conviction be liable to a fine not exceeding 1000 USD or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years or both.

However, governments have still to develop appropriate and enforced legislation that will draw ASM into national programs for environment protection.

Specific environmental legislation regulations

In Tanzania, environmental issues involved in mining are regulated by the Mining (Environ mental Protection and Conservation) Regulations, 1999, which form part of the 1998 Mining Act. As in the principle act, the regulations apply to both small- and large-scale mining operations. However, the provisions specific to SSM are addressed separately:

1. The holder of a Primary Mining License shall ensure that washing or settling ponds are constructed in his Primary Mining License area to provide for washing and sluicing, and no such washing and sluicing shall be done along or close to rivers, streams or any other water sources. Where a settling pond is used as part of the mine drainage system, ail channels discharging into the river system must be covered and the slopes protected from erosion.

2. Vegetation clearing will NOT be undertaken within twenty meters (20 m) from any stream or riverbank.

3. The holder of a Primary Mining License shall NOT heat mercury amalgam to recover the gold without using a retort.

4. The holder of a Primary Mining License shall NOT use cyanide leaching without the written approval of the Chief Inspector.

5. No holder of a Primary Mining License shall commence development of new workings in his primary mining license area without backfilling or fencing the abandoned previous workings developed by himself or his agent.

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report 27

6. Prior to the commencement of mining in any area that may have been environmentally damaged, the Primary Mining License holder shall request an inspection of said area by an inspector to confirm environmental disturbance. Any area for which the authorities have not received a request for an inspection shall be considered as normal.

7. The holder of a Primary Mining License shall ensure that tailings are disposed of at a proper place in a manner approved by the inspector.

8. No holder of a Primary Mining License shall allow children below the age of 16 to be employed or be engaged in any mining or processing operations in his primary mining license area.

9. Every Primary Mining License holder shall ensure that pit latrines are constructed and maintained at a distance of not less than one hundred meters (100 m) inland from any water source other than washing or settling ponds.

10. Every Primary Mining License holder shall ensure that each employee is provided with protective gear, and no person shall handle any toxic substance without using appropriate gear.

11. Any person who contravenes any provision under this part shall be guilty of an offence and shall be liable, on conviction, to a fine not exceeding Tshs. 50,000/= (62.50 USD) or imprisonment not exceeding three months, or both.

When governments deal with large-scale enterprises, one of the first requirements is an environmental impact assessment (ElA) and a corresponding environmental management plan. But this is expensive and far beyond the reach of most small-scale miners, who at best will try to comply by contracting low-quality environ mental consultants or, more likely, will continue to operate illegally. Under these circumstances, one solution is to bring small- scale miners together to produce a collective ElA - on the assumption that small-scale mining enterprises in an ecologically homogenous zone will have similar environmental impacts and therefore could use identical environmental management plans.

3.2.2. Decentralization

Decentralization is increasingly regarded as a priority for the governance of ASM. The reasons for this lie in the political context of globalization, which tends to promote a liberal economy, a less interventionist State and better distribution of power to local authorities.

The decentralization of ASM management consists notably in delegating the right to grant permits, inspection, etc. to institutions closer to the activity. This is especially pertinent for the actual work sites, which are often isolated, far from infrastructures and also sometimes very scattered. It allows an on-the-spot supervision.

From a fiscal stand point, the postulate here is that by shortening the distance between where the funds are collected and where they are allocated, their chances of being "dissipated" are reduced.

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

28 BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report

The risk is that the constraining authority, now no longer the State but the Province or the Municipality, and the players in the profession (LSM and ASM, alike) will turn to the advantage of the latter. Another drawback is that it may fuel inter-regional rivalries.

3.2.3. Community rights

State law versus community custom

In most mining legislation, it is clearly stipulated that ail mining resources belong exclusively to the State. The problem with this is that it can be at variance with local custom. In some countries, mineral resources have been appropriated by traditional communities for centuries, and it is simply not possible for a mining legislation to disregard such a reality.

The consensus currently is that "some" right should be granted to communities, but it is not possible to be more normative than to impose negotiations between parties.

The respect of community rights in different countries

In Mali for example, the first regulation of customary right during the French colonization in 1899 stipulated that the indigenous populations kept their customary right to exploit salt and gold deposits with the technical means at their disposal at the time, and that no prospecting, exploration or exploitation permit could hinder their activities. But such articles were sources of conflict and appear to have prevented any mining development.

In Madagascar, on the other hand, the Mining Code is a good example of respect for communities because rights established by custom are recognized by the Administration, and people who commonly have the use of a territory may ask for compensation even if they are not landowners.

ln Bolivia, the relationship between the mining operation and the community is complex. In principle, the resource belongs to the state, which grants a concession to it and charges for its use. Because of the rise of an organized indigenous movement and the acknowledgement of indigenous rights, however, the indigenous population is beginning to claim a share of the benefits of the exploitation of natural resources. Up to now, the benefits of mining that accrued to the indigenous population took the form of employment and compensation granted by mining.

The consultative approach

Any legislation applying to the use of natural resources should be prepared with the real and meaningful participation of the indigenous communities. The aim is not simply to prohibit mining exploration and exploitation in indigenous territories; neither must the law confer unlimited rights on the State to expropriate any territory with the aim of exploration and exploitation of mining resources.

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report 29

In Peru (Hruschka, 2003), representatives of communities were invited to express their opinion in defining the rules during the 2000-2002 formalization process, and this was an example of note. It would be too easy to write a logical and comprehensive piece of legislation and complain afterwards about the fact that the Administration lacks funds or the capabilities to enforce it. The local context has to be taken into account from the beginning, and the consultative approach is the only one li able to lead to success.

The counter-example of Colombia (Valbuena Wouriyu, 2003)

A good counter-example is the Colombian mining code approved in 2001 in violation of the protected rights of the indigenous population consecrated in the Constitution and in international legal instruments according to the Organizacion National Indigena de Colombia.

Chapter XVI takes no account of the differences between small, medium and large scale mining. This distinction used to allow the state to control each such mining activity, with the tons of material moved and the number of persons involved being taken into consideration. By eliminating this distinction, the law places the small- and medium-scale miners on a par with the large-scale mining corporations, with which they are obliged to compete in an unequal battle.

Chapter XVII refers to "illegal" mining exploration and exploitation. This illegality, however, is defined by the lack of formality (Le. not having a mining title) and it does not recognize the economic conditions in which some people perform mining activities. The law is thus defining these small-scale or artisanal miners' activities as "illegal" if they do not have a mining title, which means they can be subject to criminal prosecution. In the context of the current political situation of Colombia, with the problem of violent conflict in the country, this is extremely dangerous. Before this Mining Code was enacted, these small-scale activities carried out by people without mining titles was not illegal.

3.2.4. Marketing

Co-operatives

One time-honored but still valid policy that can help formalization consists in promoting the creation of cooperatives, which, for instance, might be the only entities eligible to obtain mining titles. Those refusing to join such cooperatives would thereby place themselves outside the law. The idea was that structures of this type would give both miners the opportunity to organize and the 8tate, the possibility to distinguish between legal and illegal miners. It could also provide training and a better control over the flow of substances and revenues.

Many countries have attempted to streamline regulation of the sector by encouraging the artisans to band together into cooperatives. One condition for the cooperatives' success is the relationship they maintain with local and governmental agencies. The management of these cooperatives does require considerable commitment on the part not only of its directing members, but also of the tutelary institutions. That kind of

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

30 BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report

management is to be preferred in the case of countries that can count on an efficient institutional system.

Certification

Many international initiatives have made it a priority to combat the iIIegal exploitation of precious mineral resources. Indeed, it is a proven fact that, notably in Africa, gold or diamond mining has financed, and therefore prolonged, several major wars. The poor controllability of the transport and export of these substances, which concentrate a very considerable value in a very small volume (gold) or a very small weight (diamonds), renders the existence of informal exploitation singularly conducive to all sorts of trafficking. The Kimberley process (http://www.kimberleyprocess.com). devoted to restricting the marketing of "blood diamonds" by instituting a certification and traceability system for gems, is a good example of an international initiative to promote the formalization of A8M. Policies designed to formalize artisanal mining thus converge to a certain extent with combating money-laundering and all forms of terrorism.

Certifying the mineral production at the processing stage

One means to certify the mineral production for gold would be to centralize the processing stage. If the artisanal miners are encouraged to sell their production to a centralized treatment unit, an easier means can be implemented to certify the mineral products and to control the rest of the downstream marketing chain. In Peru for example, artisanal gold miners are not allowed to treat the ore. The advantage is that it fosters better protection of the environment: a strict Environment Impact Assessment Report can be made mandatory when granting a processing license. What's more, an industrial or at least a professional concentrated treatment facility can achieve a higher recovery rate, which is better in both environmental and economic terms. The disadvantage is that the miner, as a captive client, may be placed in a weak position with respect to this service provider. If the competition between processors is not keen or effective enough, these might end up by neglecting part of the artisans' production on the basis of qualitative or quantitative arguments and thus do away with their livelihood. In such cases, the Administration must ensure a fair retribution of the miners' production, for example by guaranteeing a minimum purchasing price.

3.2.5. Taxation

Because in most countries subsurface resources represent a national heritage, it seems legitimate for the State to tax the activity, and the mining legislation must stipulate which conditions are to apply to ASM. Be that as it may, the administration must understand, and make it understood, that increasing tax revenues is not the sole purpose of formalization. Any attempt at taxation that is not well thought out is liable, at the very least, to be ineffective and, at worst, to suffocate the most fragile elements of the sector. Recognition of the artisanal mining activity must inescapably imply respect for the profession and accordingly a framework scaled to its realities.

If, therefore, a taxation regime must be set up concerning it, ASM needs to be treated less rigorously than other sectors because of the uncertainties to which it is subject

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report 31

(international priees, imperfect knowledge of the resource) and because it is often a survival strategy (a last resort, no alternative). It is true that from a theoretical standpoint ASM, like ail mining activities, generates differential proceeds, but the revenues in question are rarely substantial. On occasion, due to a supply crisis, prices may skyrocket, and at the other end of the chain, this rise impacts the small miner's earnings positively, but the situation is never long-lived and never compensates for the periods when the opposite was true.

Ad valorem taxes

Ad valorem taxes on output can be envisaged in some cases because they are generally relatively easy to administer and yield the State stable revenues, but they do raise the cut-off. They may be envisaged for small-scale mining concerns which are already at an advanced stage and should not exceed 5%.

Generally speaking, however, ASM "yields" little, either because the tax system is poorly adapted or because it is simply not applied. Many countries prefer to resort to forms other than taxing output to raise revenue. A widespread method is to charge a fee for the mining title (permit or license). The artisanal miner is often a "loner," less inclined than anyone to pay tax. Incentives need to be significant and tangible if the miner is to be convinced to file a declaration and accept to pay tax. Where precious substances are concerned, he furthermore must be incited to sell his output to the national agency instead of channeling it through contraband.

If really demanded, taxes can be levied at the purchasing office instead of the producer level. For example, the refined metal can be taxed instead of the ore, or an export tax can be imposed.

Finally, the tax system must be simple from an administrative standpoint, and transparent and functional for the taxpayers. And in any case, the granting of titles should always be used as a political instrument rather than a means for the administration to procure revenues.

3.2.6. Conflicts

Insofar as possible, mineral legislation has to prevent all kinds of conflict that ASM is liable to generate. It is assumed that a particular piece of land will produce more value if mined than if used for other purposes, and thus it should be developed independently from the landowner's will. Public interest motives justify separating land ownership from mineral ownership, which is generally vested in the State, and the traditional precedence of mining over other land uses. But separation between land and mineral ownership gives rise to serious and endemic conflicts in the use of mineral resources. The State, the mine holder (or investor) and the landowner form the traditional equation of interests that mineral law intends to reconcile. A major challenge to contemporary mineral law lies in accommodating the interests of third parties that are also affected by mining projects, such as local communities. Separation between land and mineral ownership requires a legal definition of who owns the minerals in the ground, and hence, who has access to their use, how and under what conditions.

Formalising Informal Artisanal Mining Activity

32 BRGM/RP-54563-FR – Final report

The case in French Guyana

Gold washers in French Guyana are allowed to exploit gold on land tracts covered by a mining title (prospecting or exploitation). Responsibility, notably for environmental protection, still lies with the holder of the mining title. This type of approach may seem surprising: indeed, is it not dissuasive for a prospective investor to know that his concession can be legally overrun by hoards of artisan miners? True, these measures are sometimes the result of a vigorous lobby of traditional gold washers2, which might tend to scare off investors, but the underlying policy is pragmatic and may effectively contribute to formalization.

The positive idea would be to foster a win-win relationship between the mine operators and the artisans by "forcing" their cooperation rather than allowing them to ignore each other mutually. When artisans are present on their concession, the mine operators find themselves obliged to establish a relationship with them and to arrive at agreements and a modus vivendi. Such agreements may, for example, consist in allocating special zones or particular resources (reprocessing, exploitation of resources that are not profitable by industrial means, on the edges of quarries, etc.). In exchange, the artisans may have the possibility, or even the obligation, to sell their output to the mine operator in place. The artisan becomes then a sort of sub-contractor.

The point is to move on from a conflict of interests to the search for a common interest. The overlap is a governmental incentive mechanism to obtain that LSM players deal in a responsible manner with both the environment and society. In a perspective that is both free market oriented and mindful of sustainable development, the State is thus, as it were, contracting out the formalization of these artisanal miners to industry.

This type of policy is only applicable if the quality of the reserves is high enough so that the State can impose such conditions on investors. The balance of power between the State and the investor always depends on the ascertained attractiveness of the reserves.

3.2.7. Child Labor

In a mining code, it is naturally always possible to refer to a group of preexisting laws: certain countries, for example, have a total ban on child labor. However, there again, specific articles may be required to insist particularly on this point.