Group ANALYSIS OF E W SELECTED HISTORIC … report constitutes an analysis of selected historic...

Transcript of Group ANALYSIS OF E W SELECTED HISTORIC … report constitutes an analysis of selected historic...

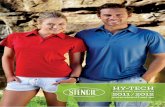

ANALYSIS OF EARLY WALL STENCILS AND SELECTED HISTORIC INTERIOR FINISHES

ROSEBERRY HOUSE PHILLIPSBURG, NJ

PREPARED FOR:

FRANK L. GREENAGEL PHILLIPSBURG AREA HISTORICAL SOCIETY

JULY 2, 2010

Keystone Preservation

Group

Historic Preservation Architectural Conservation

J. Christopher Frey Shelby Weaver Splain

Keystone Preservation Group P.O. Box 831

Doylestown, PA 18901 215.348.4919

www.keystonepreservation.com

Roseberry House, Phillipsburg, NJ Table of Contents

Keystone Preservation Project #10-004 Page 2 of 35

Table of Contents Section A Summary of Findings 3 A.1: Introduction 3 A.2: Historical Considerations 3 A.3: Assessment and Interpretation of Decorative Stencils 4 A.3.1: Design 4 A.3.2: Composition of the Binding Medium 6 A.3.3 Composition of the Pigments 7 A.4: Assessment of Other Elements 9 Section B Stratigraphic Analysis of Historic Finishes 11 B.1: Analytical Methodology 11 B.2: Stratigraphic Data for Selected Elements 12 Appendix A Stencil Drawings Appendix B Unresolved Stencil Details Appendix C Orion Analytical technical Report

Roseberry House, Phillipsburg, NJ Section A: Summary of Findings

Keystone Preservation Project #10-004 Page 3 of 35

Section A: Summary of Findings Section A.1: Introduction This report constitutes an analysis of selected historic interior finishes from the Roseberry House in Phillipsburg, NJ. In accordance with the terms of our contract with the Phillipsburg Area Historical Society (Frank L. Greenagel), Keystone Preservation Group (J. Christopher Frey and Elise S. Kemery) has completed the following: • Two site visits during which ornamental wall

stencils were exposed in Rooms 102A and 102B.

• Coordination of elemental analysis for pigments contained within colors which were noted within stencil patterns.

• Stratigraphic analysis of historic finishes from selected elements in Rooms 102A and 102B.

Section A.2: Historical Considerations The research and analysis which is detailed herein has been conducted prior to the compilation of a comprehensive report on the history and evolution of the building. The Roseberry House is believed to have been built in the late 18th century, and the decorative wall stencils which are the primary focus of this study are believed to date to original construction, or at the very least, the general period in which the building was constructed. Key dates in the historic of the building include the following:1 • Coxe family 1715 to 1766 • Upon marriage of Grace Coxe to John tabor Kempe in 1766 it is transferred to Kempe's name • 1776 confiscated • 1787 sheriff's sale to John Roseberry, Sr. • 1797 sale by John & _____ Roseberry to their son, John Jr. • 1846 transferred to Elizabeth Anderson, granddaughter of Roseberry, Sr. • 1887 sold to a third party We have been advised that our work has been completed concurrently with parallel studies by other analytical consultants. It is anticipated that the reports which issued during this phase of work will both contribute to the knowledge regarding historically-significant, character-defining features and form the basis for future studies.

1 E-mail from Frank L. Greenagel to J. Christopher Frey, July 1, 2010. Excerpted from “Who Built the Roseberry House?,”

narrative by Frank L. Greenagel, June 19, 2009.

Room 102A.

Room 102B.

Roseberry House, Phillipsburg, NJ Section A: Summary of Findings

Keystone Preservation Project #10-004 Page 4 of 35

Section A.3: Assessment and Interpretation of Decorative Stencils This study focuses on three critical aspects to consider within the analysis and interpretation of the ornamental wall stencils which are present in Rooms 102A and 102B: design, and composition of the binding medium and composition of the pigments which were used to color the stencils. Section A.3.1: Design Observations were made after the manual removal of subsequent finishes (mainly whitewash) using a combination of palette knives, scalpels and woodworking tools. Although orientation and spacing varies from room to room, stencils observed within the study area are similar with respect to color and design. Stencils were applied over a moderate gray or dark gray background, with different portions of the design executed in black, dark gray, white, red and light yellowish brown. Designs include: • Rope stencils: Used as a border element

for wall surfaces both above and below the

chair rail, this pattern features a series of paired (Room 102A) and triple (Room 102B) rope coils which are flanked by dots above and below the actual rope design. Paired coils and associated dots were executed in black and white (Room 102A), while triple coils were executed in black, white and light grayish brown (Room 102B).

• Floral bands: Present only in Room 102A and executed in white, red and light grayish brown, this pattern features a combination of large and small splayed

petals which join together in a stem element. Vertical bands are present both above and below the chair rail.

• Daisy stencils: Arranged in vertical columns and present above the chair rail in both rooms, this design features petals arranged around a center circle. Some daisies feature black and white petals, while others feature red and white or black, white and light grayish brown petals.

• Leaf stencils: Present in both rooms and arranged in vertical columns above the

Stencil patterns for Room 102A (top) and Room 102B (bottom): drawing by Keystone Preservation Group.

Rope stencil, Room 102A.

Floral band, Room 102A.

Roseberry House, Phillipsburg, NJ Section A: Summary of Findings

Keystone Preservation Project #10-004 Page 5 of 35

chair rail in both rooms, this is an abstracted, fern-like pattern which features a center column of narrow leaves which branch out at various angles. Individual leaves were executed in black, white and light grayish brown.

Although the wall stencils present in Rooms 102A and 102B created a distinct, aesthetic impact, they were intended neither to be symmetrical nor perfectly balanced (Appendix A: Stencil Drawings). Whereas vertical bands above the chair rail in Room 102B alternate regularly (leaf-daisy-leaf-daisy, etc.), bands in Room 102A alternate irregularly (leaf-floral-daisy-leaf-floral-leaf-floral-floral-floral-floral-leaf-floral-leaf-daisy-floral-daisy). It should be noted that a combination of previous damage and the inability to remove subsequent finishes in some locations have made identifying the pattern present on every inch of every wall impossible at this juncture (areas highlighted in Appendix B: Unresolved Stencil Details). The history and interpretation of decorative wall stencils has been documented in treatises such as Ann Eckert Brown’s American Wall Stenciling 1790-1840, a resource which was consulted throughout the course of this study. Other resources examined include American Decorative Wall Painting 1700-1850 (Nina Fletcher Little), Paint in America (Roger Moss, editor), Early American Wall Stencils in Color (Alice Bancroft Fjelstul and Patricia Brown Schad with Barbara Marhoefer). Although the terminology used to describe the color of stencils varies somewhat, the shades observed within the study area are consistent with those of the period:

It is evident from a study of original paint, both in New England and the South, that eighteenth century colors were, for the most part strong, and inclined to be dark, featuring Indian red, yellow ochre, blue, green, and gray.2

Research completed to date has not produced documentation which might identify the artist or individual who is responsible for the design

2 Nina Fletcher Little, American Decorative Wall Painting 1700-1850, New York: E.P. Dutton, 1989, p. 5.

Daisy stencil, Room 102B.

Leaf stencil, Room 102B.

Similar characteristics found in stencils from the Thomas Caitlin House (top) and Stratton Tavern (bottom) (photos from Nina Fletcher Little’s American Decorative Wall Painting).

Roseberry House, Phillipsburg, NJ Section A: Summary of Findings

Keystone Preservation Project #10-004 Page 6 of 35

and installation of the stencils. The stencils do incorporate design elements which were common in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, such as leaves, flowers and ropes. A very preliminary search of published images of ornamental stencils which have been documented within other historic properties suggests that the aesthetics (leaf stencils and an intertwined border element, executed in black, red and white, set against a gray background) are somewhat similar to those noted on walls of the Thomas Catlin House in Litchfield, CT. Floral stencils set against dark backgrounds have also been noted in historic properties such as the Hezekiah Stratton, Jr. Tavern in Northfield Arms, MA. In neither case are the aforementioned observations intended to constitute a link between the Roseberry House and other properties. Section A.3.2: Composition of the Binding Medium The composition of the medium in which paint colors are bound is an important characteristic of these stencils. Elemental analysis suggests that the binder is protein-based, and in-situ evaluation suggests that the stencil paint is water-soluble; these characteristics suggest that the stencils were executed in distemper. Architectural paints and coatings are composed of three elements: pigment, binder and vehicle. Pigment gives the finish its color, while the binder and vehicle are responsible for performance and properties like viscosity, pigment absorption, consistency, elasticity, reversibility. For distemper or calcimine, which traditionally indicates pre-mixed distemper, the binder is glue, usually animal hide glue, and the vehicle is water. Solidification or film formation for distemper occurs during evaporation of the solvent or vehicle, water. The glue that remains does not completely fill in the spaces between dispersed pigment particles, making distempers very porous coatings. The porosity of distemper gives the paint good hiding properties, and because it is water-based, distemper is quick drying. These two properties made distempers perfect for use in multilayered, multicolored ornamental schemes. Also, unlike oil-based paints, distempers are not prone to yellowing. Distemper paints were inexpensive and easy to make. Animal hide glue like rabbit skin would be dissolved in hot water, and often, painters made distemper on site. Distempers were applied directly to plaster walls and ceilings and also used to paint wallpaper that was then affixed to plaster walls. As oil-based paints performed more optimally on wood elements, distemper was rarely used on wood once oil-based paints became as common as distempers. Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century decorative painters preferred distemper for both stencil and freehand work. Walls would often be whitewashed or covered with a tinted whitewash as a ground for their ornamentation and then colored distemper patterns, figures and motifs would be applied. Distempers are fragile and water soluble, and eighteenth- and nineteenth century America saw frequently changing tastes in both interior and exterior paint colors and schemes. For these reasons, finding extant distemper stenciling is rare, though it would have been quite popular throughout the mid-Atlantic during the late 18th century, one notable exception being wall stencils from the Peter Wentz Farmstead in Montgomery County, PA.3 Because distempers are susceptible to water damage and difficult to clean, distemper stenciling was sometimes varnished, changing the appearance, characteristics and performance of the paint. Distempers could be, and were intended to be, easily removed with water before repainting. In cases where distemper was not removed before repainting, especially when oil or latex paints are applied over distemper, severe peeling and significant loss often occurred. Although there is no evidence of varnish on stencils from the Roseberry House, fragments of the stencils were solubilized when a subsequent layer of whitewash was installed over them. When manually removing subsequently-installed finishes, fragments of the solubilized stencils were attached to those later layers.

3 Ann Eckert Brown, American Wall Stenciling 1790-1840, Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2003, p. 5.

Roseberry House, Phillipsburg, NJ Section A: Summary of Findings

Keystone Preservation Project #10-004 Page 7 of 35

Distemper paints were common in colonial times, having been borrowed directly from English practice. Use of distemper pigments in America can be traced to seventeenth-century New England, and examples of late eighteenth-century distemper stenciling have been found widely throughout the New England Colonies of Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Maine. Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York distempers were more likely victim to changing tastes, although these Middle Colonies have some of the earliest and “most English-like stenciling” of the colonies. Pennsylvania and New Jersey were the most ethnically and religiously diverse of the colonies, and New York was a center for trade and home to aristocrats from all over Europe. Especially in more metropolitan areas, the overwhelming desire for the fashionable and latest trends “accounts for the lack of extant wall stenciling” in these colonies, although they “most assuredly had a goodly number of Federal-period paint-decorated walls.” Popular pigments for interior finishes were Prussian blue, various greens and Spanish brown; generally the palette for colonial painting was nearly identical throughout colonial America. For stencilers the palette seems to have been larger, including red lead, red ocher, Venetian red, Prussian blue, indigo, whiting, lampblack, bone black (mixed to form various shades of gray), verdigris and yellow ocher. Stenciled designs were varied ranging from simple dots or mere paneling/sectioning of walls to trees, birds, vines and garlands, festoons and floral motifs and sprays. Section A.3.3: Composition of the Pigments Keystone Preservation contracted with Orion Analytical of Williamstown, MA for the identification of pigments which were use to color the stencils: dark gray, white, black, light yellowish brown and red (Appendix C: Orion Analytical Technical Report). Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy (FTIR) was employed as the initial, primary method of analysis. A technique which is commonly used to identify pigments in historically significant works of art, which parallel pigments used in historic architecture, FTIR produces spectral readouts (spectra) for each material which is analyzed, the results of which are then compared to spectra from known materials. FTIR successfully detected (positive or probable detection) materials in three of the five shades which were subjected to this method of analysis (gray, black and white). At no additional charge, Orion Analytical completed subsequent assessment of materials which could not be identified with FTIR using Raman microscopy. Raman analysis relies on the scattering of monochromatic light, typically from a laser in the visible, near infrared or near ultraviolet range. This light interacts with excitations in the sample, creating vibrational information which is unique to or consistent with specific chemical bonds. Raman produced a strong, unique yet unidentifiable spectrum for one material (red) and no unique spectrum for the second (light yellowish brown). Further analysis was completed using scanning electron microscopy with x-ray energy-dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-XEDS). SEM images a sample by scanning with high-energy electron beams; X-ray beams then produce information which is characteristic of specific elements. This technology both provides imaging information on the structure of material and information regarding which chemical elements are present within that material. SEM-XEDS identified (probable) the red pigment but, despite producing detailed compositional information, was unable to conclusively identify the light yellowish brown pigment. Dark gray FTIR produced a probable identification of carbon black (with no iron or bone black), combined with calcite as the pigments present within dark gray elements. A “probable protein binder” has been interpreted as distemper based in part on its water-solubility. Historically, carbon black and calcite have been used since prehistory, and continue to be used today. 4 As such, their use in a building which is believed to date to the late 18th century is reasonable. Two shades of dark gray were noted, corresponding to Munsell N 5.25/ and Munsell N 2.25/.

4 http://www.webexhibits.org/pigments/indiv/history/carbonblack.html

Roseberry House, Phillipsburg, NJ Section A: Summary of Findings

Keystone Preservation Project #10-004 Page 8 of 35

Black FTIR produced a probable identification of carbon black (with no iron or bone black), combined with calcite as the pigments present within black elements. The calcite content is likely lower than that which was noted for dark gray elements. Black elements were also identified as having a “probable protein binder,” and the use of such pigments is consistent with what might have been used in the late 18th century. Black stencils correspond to Munsell N 0.5/. White FTIR produced a positive identification of calcite as the compound used for white elements. Calcite consists of calcium carbonate, the compound which forms the basis for lime. It was often combined with oil due to its poor hiding power or animal glue (distemper)/other aqueous binders as a white pigment; 5, 6 in these stencils, however, no oil (or other) binder was noted. Also referred to sometimes as “lime white,” “chalk” and “whiting,” calcite has been available since prehistory and remains in use; 7 as such, its presence in a building which is believed to date to the late 18th century is reasonable. White (technically “yellowish white”) stencils correspond to Munsell 5Y 9/1. Red FTIR detected the presence of calcite and lead, but was unable to positively identify the pigmenting compound. However, analysis did identify a “probable protein binder” which has been interpreted as distemper. Subsequent analysis with Raman spectroscopy produced a strong, unique spectrum, but the spectrum did not match the spectrum of any known samples. Further analysis with SEM-XEDS revealed the presence of lead, calcium, magnesium, strontium (associated with lead), potassium, aluminum, phosphorous and silicon. Orion interpreted the large amount of lead and corresponding absence of iron and mercury which are markers for iron oxide and vermillion, respectively, as a probable identification of red lead as the primary pigment. Additional confirmation using polarized light microscopy was noted as a possibility but was not pursued. Red lead is a dense, finely-textured pigment with exceptional hiding power; 8 these qualities are characteristics which contribute to the striking opacity and intensity which remain present on stencils which feature this color. It was considered fairly permanent when mixed with oil, and possessed a good reputation with tempera (distemper) painting.9 This pigment was commonly used in Byzantine and Persian illuminations, and remained common through the late 19th century, when its use was largely discontinued due to concerns over toxicity and propensity for color change.10 It is possible that red lead was considered appropriate for use in the distemper stencils during the period in which this building is believed to have been constructed. Red (technically “dark reddish orange”) stencils correspond to Munsell 10R 4/8. Light yellowish brown FTIR was unable to detect a pigmenting compound for light yellowish brown features, but identified a “probable protein binder” which has been interpreted as distemper. Subsequent analysis with Raman spectroscopy did not produce a unique Raman spectrum. Further analysis with SEM-XEDS revealed the presence of calcium, magnesium, sulfur and aluminum, but the results were not sufficient to conclusively identify the pigment. Interestingly, the absence of iron rules out iron oxides as a pigment, and the absence of elements which are typically associated with inorganic yellow pigments was also noted. Additional confirmation using polarized light microscopy was noted as a possibility but was not pursued. Red stencils correspond to Munsell 10YR 6/4. 5 http://www.naturalpigments.com/oil_paints/calcite_medium.asp 6 http://www.naturalpigments.com/oil_paints/calcite_medium.asp 7 http://www.naturalpigments.com/oil_paints/calcite_medium.asp 8 http://www.webexhibits.org/pigments/indiv/overview/redlead.html 9 http://www.webexhibits.org/pigments/indiv/technical/redlead.html 10 http://www.webexhibits.org/pigments/indiv/history/redlead.html

Roseberry House, Phillipsburg, NJ Section A: Summary of Findings

Keystone Preservation Project #10-004 Page 9 of 35

Section A.4: Assessment of Other Elements Keystone Preservation’s scope was intended to include microscopic analysis of and color matching for 10 samples, with those locations to be determined during the completion of exposure windows. In consultation with Frank L. Greenagel, we decided to focus analysis on elements in Rooms 102A and 102B; analysis was expanded to include examination of 32 surfaces, with the balance provided at no additional cost. Assessment included wall surfaces (including color matching for each stencil color present), ceilings, chair rail, baseboard, door trim, doors and window frames. Analysis suggests the following: • The finishes history within the study area is highly variable. Some elements display evidence of

as many as 21 finish layers, while others display evidence of as few as 2. While some of that difference can be attributed to changes which have taken place over time (including the alteration or replacement of certain features as well as localized damage to or loss of original finishes), there is not a regular pattern to the varying number of layers present. Slight variations in the shade of selected finishes are also a complicating factor. As such, we would recommended that findings be considered preliminary at this juncture and would recommend additional assessment in a future phase when finishes evidence from these rooms can be properly compared to comparable samples throughout the building.

• Wall surfaces featured several colors for background fields and stencils, including dark gray (Munsell N 2.25 and N 5.25), black (Munsell N 0.5/), yellowish white (Munsell 5Y 9/1), dark reddish orange (Munsell 10R 4/8) and light yellowish brown (Munsell 10YR 6/4).

• Preliminary interpretation suggests that baseboards and door trim at baseboard level were painted dark brown (Munsell 5YR 2/2-2/4), chair rails, chair rail caps, and door trim above baseboard level were painted light olive brown (Munsell 2.5Y 7/2), and ceilings finished with a, and ceilings finished with a yellowish white (Munsell 5Y 9/1) whitewash.

The following chart provides digital approximations for colors which are believed to date to the installation of the stencils in Rooms 102A and 102B. These are intended for illustrative purposes only and should not be used for official color selection. Chips which conform to the Munsell System of Color will be provided by the Conservator, or are available from X-Rite (www.x-rite.com). Historic colors

Element Munsell Color/Color Name Color Equivalent

Wall background field Munsell N 2.25/ Dark gray

Munsell N 5.25/ Dark gray

Black stencils Munsell N 0.5/ Dark gray

White stencils Munsell 5Y 9/1 Yellowish white

Roseberry House, Phillipsburg, NJ Section A: Summary of Findings

Keystone Preservation Project #10-004 Page 10 of 35

Historic colors, continued

Element Munsell Color/Color Name Color Equivalent

Red stencils Munsell 10R 4/8 Dark reddish orange

Light yellowish brown stencils Munsell 10YR 6/4 Light yellowish brown

Ceilings Munsell 5Y 9/1 Yellowish white

Baseboards, door trim at baseboard level

Munsell 5YR 2/2-2/4 Dark brown

Door trim above baseboards, chair rails, window trim

Munsell 2.5Y 7/2 Light olive brown

Roseberry House, Phillipsburg, NJ Appendix A: Stencil Drawings

Keystone Preservation Project #10-004

Appendix A: Stencil Drawings

{t)oo:l--

^ ().-_IAUi U TT)

ln: 0 u(Jo c(D

^fl

Iut ,Z +o .__L

t*ulq6'(D l(](D

o

-Tl

-'aj(D

a

l.D =

-.lCl O -I 3 sS o rD

n.\

e ilili4tr lI;;Y; 9

arO*ffn)

- J (r UJ lUtu 0r N T-

d: T> -Ut't? I -

--l

J6fico o a_-:ro /)f J 'c'o O=+J*.oO:: oo'g U ^'ol u--<Jo-.o r,,f

---i

_- () : OL--

jO

=A cgaco--:=rO-a

oZcC6

o

3t?ti -le lH

_itEl I

;t I

0v2o:o

9at{

l

lzU:I] ,ol,rlxr 1

i

ao

I

O

tc

CC

o

l!?a)

Jlt^O:V,

-. tt)

b oovr6L)

o !o + \g:f(, Z-(- o -_I: ll,rf

aa

Ao lo

o{L

lt:J

aJ(b

v,C)

a-o-(A

_U

(Dao

O-.O:)

C) --l

C,C

c

o € --lu-uIioo^

- i -'< !,^t(u u ^

----.,^ iT ,.^nvrw

''.< .. o Iu) (.n < ,

oo-lmrJ('lc!(])(a

xq e;.r d l_

J 'o (ll Cod l:!o-i toJ

6Orol

6r coVqro

?oo:l

T-

=< o.ao

7cL(n

r l.s lTi l< l,r

1l;lI +l+l

=i I

tll?l I

NO

O

c

a

Zc:o

I

|\J

I

(l-rl

i."

u)

qI

zIU)

Roseberry House, Phillipsburg, NJ Appendix C: Orion Analytical Technical Report

Keystone Preservation Project #10-004

Appendix B: Unresolved Stencil Details