Gross Negligence

-

Upload

ang-kai-wen -

Category

Documents

-

view

124 -

download

6

Transcript of Gross Negligence

[Type text] [Type text] ANG KAI WEN

HARRY ELIAS-SMU MOOTING TOURNAMENT 2011

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE

SUIT NO. 182/2011/Z

SURE WIN TRADING PTE LTD..…Appellant

AND

SERVERS ‘R’ US PTE LTD…..Respondent

MEMORIAL FOR THE APPELLANT

7 OCTOBER 2011

“I pledge my honor that I have not violated the tournament’s Honor Code during this

Tournament.”

Page 1 of 10

[Type text] [Type text] ANG KAI WEN

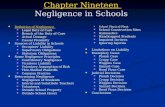

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES 3

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT....................................................................................4

ISSUES ARISING IN THE APPEAL...........................................................................5

ARGUMENTS AND AUTHORITIES..........................................................................5

A. THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN NEGLIGENCE AND GROSS NEGLIGENCE IN

SINGAPORE LAW IS MERELY ONE OF DEGREE. IT DOES NOT EQUATE TO

WILFUL DISREGARD OR A DIFFERING STANDARD OF CARE.............. 5

B. THE DISTINCTION LAID OUT BY THE TRIAL JUDGE IS INCONSISTENT

WITH THE WEALTH OF RELEVANT COMMON LAW AUTHORITIES, ALL OF

WHICH ADVOCATE A SINGLE STANDARD OF CARE AND DISTINGUISH

GROSS NEGLIGENCE FROM WILFULL DEFAULT........................................7

C.THE DIFFERENCE IN DEGREE BETWEEN NEGLIGENCE AND GROSS

NEGLIGENCE MERELY ENTAILS AN EXAMINATION OF THE INDIVIDUAL

FACTS OF EACH CASE...........................................................................................108

Page 2 of 10

[Type text] [Type text] ANG KAI WEN

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Armitage v. Nurse and others [1997] 3 WLR 1046

Chandran a/l Subbiah v Dockers Marine Pte Ltd [2011] SGCA 39

Canada Steamship Lines Ltd v. The King [1952] 1 AC 192

Go Dante Yap v. Bank Austria Creditanstalt AG [2011] SGCA 9

Grill v General Iron Screw Collier Co (1866) 35 LJCP 321

Ng Keng Yong v PP [2004] 4 SLR(R) 89

Sie Poh Choon (trading as Image Galaxy) v. Amara Hotel Properties Ltd [2003] 3 SLR(R)

703

Seino Merchants Singapore Pte Ltd v. Porcupine Pte Ltd [1999] 3 SLR(R) 221

Spread Trustee Company Limited (Appellant) v. Sarah Ann Hutcheson and others

(Respondent) [2011] UKPC 13

Red Sea Tankers Ltd and others v. Papachristidis and others (“The Hellespont Ardent”)

[1997] 2 Lloyds Rep 547

The “Ohm Mariana” ex “Peony” [1992] 1 SLR(R) 556

Thomas Giblin (Executor of Richard Lewis) v. John Franklin McMullen (1868) LR 2 PC 317

Tradigrain SA v. Internek [2007] EWCA Civ 154

Wilson v Brett (1843) 11 M&W 113

Wong Kok Chin v. Singapore Society of Accountants [1989] 2 SLR(R) 633

OTHER AUTHORITIES

The Law Commission Consultation Paper No. 171 “Trustee Exemption Clauses: A Consultation

Paper”

The Trust Law Committee Consultation Paper (King’s College, London) “Trustee Exemption

Clauses”

Arthur Goodhart, Restatement of the Law of Torts II, University of Pennsylvania Law Review

and American Law Register, Vol. 83, No. 8

Gerald McCormack, “The Liability of trustees for gross negligence” Conveyancer and Property

Lawyer, 1998

Liam Brown, “Gross negligence in exclusion clauses: is there an intelligible difference from ordinary negligence.” (2005) 16 Insurance Law Journal 175

Page 3 of 10

[Type text] [Type text] ANG KAI WEN

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

The trial judge in law in ruling that gross negligence connoted “a much higher level of

neglect and/or wilful disregard above ordinary negligence”. Such a distinction has never been

recognized in the common law of Singapore. Even if a distinction were to be made, the

difference between “gross” and “ordinary” negligence is a matter of degree on the facts of

each case and does not connote a sui generis standard of care.

ISSUES ARISING IN THE APPEAL

I. Whether in Singapore law there is a difference between gross negligence and negligence.

II. If so, then what these differences are; and

III. If not, whether there is a need to differentiate between gross negligence and negligence.

Page 4 of 10

[Type text] [Type text] ANG KAI WEN

ARGUMENTS AND AUTHORITIES

A. THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN NEGLIGENCE AND GROSS NEGLIGENCE IN

SINGAPORE LAW IS MERELY ONE OF DEGREE. IT DOES NOT EQUATE TO

WILFUL DISREGARD OR A DIFFERING STANDARD OF CARE.

1. It is submitted that the learned trial judge, Justice A.C. Reid erred in law in ruling that

gross negligence was distinguishable from negligence in Singapore Law to mean either “a

much higher level of neglect and/or willful disregard”. Such a distinction does not exist in

Singapore Law. In Singapore, what exists is a single standard of care for negligence, and the

term “gross negligence” is merely a contractual term of art commonly used in exclusion

clauses. Any distinction between gross negligence and negligence is merely one of that of

degree on the facts of each individual case rather than a separate head of liability.

2. It must be noted as a starting point that there is scant local authority on the distinction

between gross negligence and negligence. This was acknowledged by Justice Lai Kew Chai

in Sie Choon Poh (trading as Image Galaxy) v Amara Hotel Properties Pte Ltd ("Sie Choon

Poh”)1. In the recent case of Go Dante Yap v Bank Austria Creditanstalt AG2, the Singapore

Court of Appeal expressly declined to elucidate on this distinction, instead preferring to

reserve its analysis for the future. The end result is that there has yet to be a leading

Singaporean case which explicitly clarifies the nature of this alleged distinction.

3. Despite this, it is submitted that existing case law pertaining to gross negligence has argued

for a consistent standard of care. In Singapore, the standard of care with regards to negligence

is that of “the standard of the reasonable person” (Chandran a/l Subbiah v Dockers Marine

Pte Ltd3 as per Rajah JA) and this is an unwavering standard.

4. It is submitted that there is consistent local authority to justify that “gross negligence”

warrants the same standard of the reasonable person, and not the contrary view espoused by

the trial judge. Selvam J in Seino Merchants Singapore Pte Ltd v Porcupine Pte Ltd4, (“relied

1 [2005] 3 SLR(R) 576 at para 92 [2011] SGCA 39 at para 63 [2010] 1 SLR 786 at para 21, with Phang JA citing the English locus classicus of Blyth v The Company of Proprietors of the Birmingham Waterworks (1856) 11 Ex 781.4 [1999] 3 SLR(R) 221

Page 5 of 10

[Type text] [Type text] ANG KAI WEN

on by the appellants at trial) explicitly notes that “gross negligence was no more than mere

negligence” and that the standard of care was the same unwavering standard of the ordinary,

reasonable person5, echoing his earlier judgement in The “Ohm Mariana” ex “Peony”6.

5. This was also the view adopted by Yong J (as he then was) in Wong Kok Chin v. Singapore

Society of Accountants7 where he opined that such a term “can mean no more than plain

negligence” and that gross neglect amounted to a failure to “exercise the skill and care that a

reasonable client would have been entitled to expect of him”8 and nothing more. In addition,

the case of Ng Keng Yong v PP9 also supports the argument that the “certainty of a general

standard is preferable to the vagaries of a fluctuating standard.”10 As such, local authority is

consistent with in the adoption of a single standard of care, and an assertion to the contrary

would be going against the weight of cogent local authorities.

6. It is submitted that the case relied on by the Defendants at trial, Sie Choon Poh is

consistent with this approach as Lai J in fact notes that it is not possible to discern a different

standard “by which a court can confidently rule when negligence should be deemed to be

gross negligence”11. Essentially, Lai J noted that there is no differing standard of care and

gross negligence is merely a matter of degree to be determined on the facts. Lai J further

opines that the meaning of “gross negligence” itself is determined by ascertaining the

intentions of contracting parties as a matter of construction: this will be elaborated on later.12

7. Ultimately, it is submitted that the combined weight of local authority strongly supports the

argument that a single standard of care applies, and not one of a “higher level of neglect or

willful disregard”. Those concepts are foreign to Singapore Law and not discernable from the

volume of local case law. With respect to the learned trial judge, such a distinction is not

supported by local authorities, and as such should not take root in our legal system. Any

difference between gross negligence and negligence is one of that of degree: this does not

vary the standard of care whatsoever.

5 Ibid at para 13, with Selvam J, citing the English authorities.6 [1992] 1 SLR(R) 5567 [1989] 2 SLR(R) 6338 Ibid at para 189 [2004] 4 SLR(R) 8910 Ibid at para 76, Yong CJ citing with approval the English authority of Nettleship v Weston [1971] 2 QB 96111 Supra note 1 at para 612 See below at para 15

Page 6 of 10

[Type text] [Type text] ANG KAI WEN

B. THE DISTINCTION LAID OUT BY THE TRIAL JUDGE IS INCONSISTENT

WITH THE WEALTH OF RELEVANT COMMON LAW AUTHORITIES, ALL

OF WHICH ADVOCATE A SINGLE STANDARD OF CARE AND

DISTINGUISH GROSS NEGLIGENCE FROM WILFULL DEFAULT

8. It is submitted that the trial judge’s distinction is also unsupported by the weight of

relevant common law authorities, most notably the common law of England, which remains

highly persuasive as the Singapore law of torts has essentially mirrored the development of

the English law of torts with relatively few departures. This is evident from the fact that many

of the local cases relied upon for expounding on the gross negligence (for example “Sie

Choon Poh”) have cited relevant English authorities. The relevant common law authorities

have similarly espoused a single standard of care for “gross negligence” and have expressly

rejected the idea that it can be equated to any form of “wilful disregard” whatsoever.

9. It is submitted that the English common law position for the last hundred and fifty years

has been unequivocal in stating that a uniform standard of care exists and no such distinction

can be made with regards to gross negligence. As far back as the 1800s, Lord Chief Justice

Denman in Hinton v Dibber13 noted “it may be well doubted whether between gross

negligence and negligence, any intelligible distinction exists”, swiftly followed by Lord

Cranworth’s famous pronouncement in Wilson v Brett14 that “gross negligence is negligence

with a vituperative epithet” (endorsed by Willis J in Grill v General Iron Screw Collier Co15.

and in a contemporary local context by Selvam J in Seino Merchant and the Ohm Mariana16)

10. More recently, English case law has essentially made pronouncements to the same effect.

In 1997, Lord Justice Millett in Armitage v. Nurse and others17 (“Armitage”) pronounced that

“[W]e regard the difference between negligence and gross negligence as merely one of

degree. It is not a difference in kind.” This was endorsed by the English Courts of Appeal in

Tradigrain SA v Internek18 which explicitly noted that gross negligence “has never been

accepted by English civil law as a concept distinct from simple negligence” and Springwell v

13 (1842) 2 QB 64614 (1843) 11 M&W 11315 (1866) 35 LJCP 32116 Supra at note 4 & note 6 respectively17 [1997] 3 WLR 104618 [2007] EWCA Civ 154

Page 7 of 10

[Type text] [Type text] ANG KAI WEN

JP Morgan19 which acknowledged that the difference was a “somewhat sterile and semantic

one.” This view was echoed by the Privy Council in the case of Spread Trustee Company

Limited (Appellant) v. Sarah Ann Hutcheson and others (Respondent)20 (“Spread Trustee”)

which noted that “in any event, it is difficult to see why the line should be drawn between

negligence and gross negligence.”

11. It can be discerned from the line of English authority stretching back to a hundred and

fifty years ago that the standard of care with regards to negligence is the sole standard.

Elaborating on t in Armitage that the difference was a matter of degree, not kind; it is clear

that that the term “gross negligence” in itself does not warrant a departure from the usual

standard of care. A difference in degree is determined on the facts of each case, and “gross

negligence” is merely descriptive of that difference (as per Lord Chelmsford in Thomas

Giblin (Executor of Richard Lewis) v. John Franklin McMullen21(“Giblin”)) The term is

indicative of greater fault, or greater blame perhaps in individual cases, but it does not

connote as different kind of higher neglect or any element of wilfulness as suggested by the

learned trial judge.

12. English authority is similarly unequivocal in rejecting the argument that “gross

negligence” could amount to a form of wilful default in the common law. Millett LJ in

Armitage noted that the English common law, as opposed to civil law systems had “always

drawn a sharp distinction between negligence, however gross, on the one hand, and fraud,

bad faith and wilful misconduct on the other. The doctrine is that ‘gross negligence may be

evidence of mala fides but is not the same thing’ (citing Lord Chief Justice Denman in

Goodman v Harvey22)”. This was cited with approval by both the Privy Council in Spread

Trustees, of which both Lord Clarke and Sir Robin Auld noted that “to describe negligence as

gross does not change its nature so as to make it fraudulent or wilful misconduct”.

13. There are common law authorities that endorse a contrary view in this case, notably the

New York Court of Appeal in Sommer v Federal Signal Corp23 which equated gross

negligence to “conduct that evinces a reckless disregard for the rights of others or smacks of

19 [2010] EWCA Civ 122120 [2011] UKPC 1321 (1868) LR 2 PC 31722 (1836) 4 A & E 87023 79, NY2D

Page 8 of 10

[Type text] [Type text] ANG KAI WEN

intentional wrongdoing.” However, this case can be easily distinguished as the American

Restatement of Torts has established “recklessness” as a separate head of liability from

negligence24. This is non-existent in the English and Singapore common law and thus the

American distinction is not persuasive due to the difference in tort law.

14. As such, it is ultimately submitted that the relevant English authorities are not only highly

persuasive, but extremely cogent in supporting the local position that the standard of care

does not vary, nor should gross negligence be equated with any form of wilful conduct. To

find otherwise in this case would be to fly in the face of very well reasoned and expounded

English authorities stretching back to a century ago, which remain highly relevant due to the

close relations between English and Singaporean tort law.

C. THE DIFFERENCE IN DEGREE BETWEEN NEGLIGENCE AND GROSS

NEGLIGENCE MERELY ENTAILS AN EXAMINATION OF THE INDIVIDUAL

FACTS OF EACH CASE.

15. As submitted above, the distinction between negligence and gross negligence is merely

one of degree, to be determined on the facts of each case. This was essentially the view

proposed by the English Court of Appeal in Armitage as well as Lai J in Siew Choon Poh

(after having considered the English case of Red Sea Tankers Ltd and others v.

Papachristidis and others25 (“The Hellespont Ardent”).

16. It is submitted that especially in a scenario concerning exclusion clauses, such as this one,

it ultimately boils down to ascertaining the intentions of the contracting parties, i.e. what did

both the Appellant and the Respondent mean by “gross negligence” as a matter of contractual

construction. It is submitted that this was precisely what Lai J meant in Siew Choon Poh

when she listed a series of factors including:

“notice or awareness of the existence of the risk, the extent of the risk, the character of

the neglect, the duration of the neglect and, not least, the ease or difficulty of fulfilling

the duty are important, and in some cases vital, in determining whether the fault (if

any) of a defendant” [amounts to gross negligence]26

24 Arthur Goodhart, Restatement of the Law of Torts II University of Pennsylvania Law Review and American Law Register, Vol. 83, No. 825 [1997] 2 Lloyds Rep 54726 Supra note 1 at para 8

Page 9 of 10

[Type text] [Type text] ANG KAI WEN

Lai J’s reasoning clearly echoes that of Mance J in The Hellespont Ardent:

“I see no difficulty in accepting that (a) the seriousness or otherwise of any injury that

might arise, (b) the degree of likelihood of its arising and (c) the extent to which

someone takes any care at all are all potentially material when considering whether

that particular conduct should be regarded as so abhorrent as to attract the epithet of

gross negligence”27

17. On the facts of the case at hand, it is submitted that Mr. Tan Ku Ku’s actions amounted to

gross negligence as a matter of contractual construction. It is submitted that the exclusion

clause which the Respondents seek to rely upon, upon a strict contra proferentum reading,

was meant to only exclude simple negligent breaches such as hypothetically if Mr. Tan had

genuinely left the office to retrieve additional equipment for a short period of time. Anything

more than such possible scenarios would not have been envisaged by a reasonable man

standing in both the shoes of the contracting parties.

18. Surely an abdication of duty (with reference to Lai J’s and Mance J’s factors as

mentioned above), such as what Mr. Tan did by leaving his job mid-way to buy flowers for

his girlfriend, would amount to gross negligence. It would be logically incoherent for the

Respondent to suggest that the exclusion clause they are seeking to rely upon can exclude

liability for such acts that while not amounting to either wilful misconduct or fraud, clearly

lay more fault at the feet of the Respondent as opposed to the less blameworthy scenario

mentioned above. Moreover, the lack of any precaution taken whatsoever, such as leaving

someone on site to monitor the system makes the Respondent all the more blameworthy.

19. This distinction in terms of degrees of negligence is a matter of common sense (as per

Lord Chelmsford in Giblin28) and is simply a matter of determining fault and

blameworthiness. It is submitted that this formulation is consistent with the existing

authorities and as such should be the approach adopted.

27 Supra note 25 at 58828 Supra note 21

Page 10 of 10