Grid Magazine [#047]

-

Upload

danni-sinisi -

Category

Documents

-

view

225 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Grid Magazine [#047]

![Page 1: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/1.jpg)

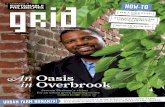

MARCH 2013 / ISSUE 47 GRIDPHILLY.COM

S U S TA I N A B L E P H I L A D E L P H I A

t a k e o n e !

C H A N G I N G FAC E P R E S E R VAT I O N

The

of

Deacon Lloyd Butler and the 19th Street Baptist congregation do-it-themselves

HOUSE RULES Overbrook Farm’s fight for (and against) historical recognition

IN THE DARK Growing, cooking and pickling oyster mushrooms

COMMUNITY CHEST Investments you can believe in

special

sect ion

![Page 2: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/2.jpg)

1 6 GRIDPHILLY.COM M A R C H 2 0 1 3

THE BREWER’S PLATESunday, March 10, 2013

National Constitution Center

TICKETS ON SALE NOW!

20 local restaurants, 20 local craft breweries, spirits, sweets & more!Fair Food once again brings you a celebration of our region’s craft breweries, restaurants, farmers,

& artisan producers – all independently owned and located within 150 miles of the city! A one-of-a-kind tasting event that pairs craft beer with local gourmet food for eaters of all kinds!

All proceeds benefit Fair Food, a 501(c)3 dedicated to promoting and sustaining a healthy local food system for the region!

The

2013

the BIG taste behind small scale

Wonderssmall

@FairFoodStand #brewersplate fairfoodphilly.org

JOIN US IN VIPzThe Speakeasy

Where local spirits & sweet collide!

INCLUDED IN GA

![Page 3: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/3.jpg)

years. According to one study that’s how long it takes to recover the energy lost in demolishing a building and replacing it with a new, energy-efficient one. While we do need new buildings, and it’s thrilling

to see structures built that incorporate green building practices, it’s essential that we understand the value of what already exists. Preservation is perhaps a quieter aspect of sustainability, but philosophi-cally, it’s at the subject’s root. Beyond the sustainability concept of “embodied energy,” there’s also a strong community component to preservation. What do we value enough to keep? And what do these choices say about who we are?

When we at Grid were planning to tackle preservation, we were im-mediately drawn to the amazing work already being done by Hidden City Daily, an online news organization that excels in their coverage of the city’s neighborhoods and buildings. An idea emerged: Could Grid and Hidden City collaborate? This section is the answer. The following stories look at some of the inspiring work being done by Philadelphians to preserve the buildings they love, ensuring that our city’s future will be filled with the treasures of the past.

a special editorial partnership

Learn more at hiddencityphila.org

THE FUTURE OF THE PAST

![Page 4: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/4.jpg)

At the heart of this grappling with our inher-ited streetscape is the confounding and deeply ambiguous practice of preservation. Historic—or landmarks—preservation came into modern con-sciousness in the 1950s after the demolition of two monumental icons of the railroad age, Philadel-phia’s Broad Street Station and New York’s Penn Station, and the loss of countless neighborhoods to new highways and expanding universities and hospital centers. The preservation movement gal-vanized various democratic instincts all at once. In Philadelphia, it led to the nation’s first preser-vation ordinance in 1955, a well-intentioned but weak law that was strengthened in 1985 to protect historic buildings from demolition.

But in many ways, the preservation instinct runs counter to the American mindset and those who have opposed it often base their argument in the mantra of private property rights. Though basic property rights are routinely regulated through zoning, height and use limitations, etc., it is preservation that draws this kind of ideologi-cally narrow response.

In a kind of opposite ideological tact, for de-cades progressive thinkers, including Koolhaas, have seen preservation as distinctly reactionary,

steeped in nostalgia and myth. One of my favorite books to set up the conflict between the desires to preserve the old and build the new is the novel Re-turn to Dar al-Basha, by Tuni-sian writer Hassan Nasr, about the emotional power of Tunis’ old city (one of the world’s largest sites of preservation). “That old house and all those old neighborhoods need to be

torn down,” says a character in Nasr’s book, “so they can be rebuilt with structures that have the amenities that correspond … to modern life … These old neighborhoods were built on injustice … exploitation and tyranny … the oppression of women, on the expropriation of workers’ rights.”

Part of the critique, which I share, is that pres-ervation begs us to defer to this not so gentle past, whose building materials we assume were stron-ger and more beautiful and craftsmanship better. But the danger of quieting the equally powerful instinct to build anew is that it saps our own con-fidence and architectural vision. In Philadelphia, where developers, fearful of risk, so often pander to the past, the field of contemporary architec-ture has been stunted by mimicry. Originality has been shunted.

As the past—as if it were architecturally uni-form—forcefully weighs down on present-day designers, the regulatory mechanisms for pres-ervation have withered, creating an odd reality: great old buildings are routinely demolished while new ones are made to look old. Developers have recently been exploiting loopholes in Phil-adelphia’s preservation ordinance; meanwhile the underfunded Historical Commission is hard

strapped to add new buildings and districts to its protected list (New York, the cradle of destruc-tion, has more than 100 protected and promoted historic districts. Philadelphia has nine).

But the broken system is an opportunity for Philadelphians to expansively reimagine what they hope to achieve with preservation and to decide within the scope of present-day desires, among them

sustainability and green construction, how best to build on our past. There are very strong reasons for wanting to protect buildings related to the development of 20th century African-American culture, Italian-American, Chinese-American, and Jewish neighborhood life in particular and immi-grant life in general, and the mills and factories that for 150 years defined the rhythms of city life and lend our present-day neighborhoods scale and density. There is emerging support for the preser-vation of large and small examples of mid-century modern architecture, perhaps especially those that emerged from the modernist instinct to break with the past. Very few of these kinds of buildings are at present protected in Philadelphia. How we go about preserving them within the collected lay-ers of the Philadelphia cityscape is a wonderfully challenging and sometimes exasperating task that is likely to absorb us for years to come.

nathaniel popkin is co-editor of Hidden City Daily, senior writer of the film documentary Philadelphia: The Great Experiment, and author of Song of the City: An intimate portrait of the American Urban Landscape and The Possible City: Exercises in Dreaming Philadelphia.

If,!as the architect Rem Koolhaas writes in Delirious New York, “creation and

destruction are the poles defining the field of Man-hattan’s abrasive culture,” in Philadelphia, it is adaptation and accretion that nourish our urban experience. We feed on the peeling and unpeel-ing of layers, on acts of discovery that bind us—in sometimes powerful ways—to the ideals and aspi-rations of those who came before us.

GR ID + H IDDEN C ITY

1 8 GRIDPHILLY.COM M A R C H 2 0 1 3

What in our past IS worth preserving, and how does

LAYERED QUESTIONS

STORY BY NATHANIEL POPKIN PHOTO BY PETER WOODALLit shape our city’s future?

This former auto showroom was converted into an o!ce building in 1963 and then a homeless shelter in 1987. Last summer, it was repainted and and restored as headquarters for Stephen Starr’s catering business.

![Page 5: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/5.jpg)

M A R C H 2 0 1 3 GRIDPHILLY.COM 1 9

ALSO ON FACEBOOK!

www.philadelphiasalvage.com

WED 10-6 | THU 10-7 | FRI-MON 10-6 | TUES CLOSED

542 Carpenter Lane Philadelphia, PA 19119 215-843-3074

2011E ST

PHILADELPHIA SALVAGE COMPANY

RECLAIMED LUMBER YARD, CUSTOM FURNITURE, DESIGN BUILD

![Page 6: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/6.jpg)

The field of preservation is filled with people moti-vated by a passion for architecture or history. But not everyone starts out that way. In fact, some of the most interesting preservation projects in Philadelphia are being pursued by unexpected people. We call them “accidental preservationists.” Two such people, an ambitious developer and a former dancer, are hard at work on North Broad Street where they’ve found themselves deeply invested in reviving buildings that without their help might no longer exist.

ERIC BLUMENFELD | EB REALTY MANAGEMENT

GR ID + H IDDEN C ITY

BY LIZ PACHECO

ACCIDENTAL PRESERVATIONISTSBeautiful buildings and fascinating history

cast a spell on the unsuspecting

Eric Blumenfeld claims he’s been working in real estate since he was four years old. “All the other kids got to play on Saturday and my father used to drag me to work,” he says. But the former English major—who as a freshman decided not to study accounting, he says, because the registration lines were too long—didn’t formally join the real estate and development world until after college at his father’s behest. In the late 1980s, Blumenfeld had the opportunity to buy many of his father’s properties and founded his own company EB Realty Management. While the company has various projects—many involving historic buildings—throughout the city, North Broad Street is by far the greatest in scope.

“Ten years ago I [would] show up on North Broad Street,” says Blumenfeld, “and I would take bankers down here and they would look at me, like ‘you’re out of your mind.’” But standing on the rooftop of the Thaddeus Stephens School of Practice at Spring Garden and Broad Streets, Blumenfeld’s vision now seems less laughable.

Looking up the block, there’s the renovated and now rainbow-painted mid-century building where Stephan Starr has headquartered his catering company. There’s the deteriorating but magnificent Divine Lorraine Hotel, which when finished will become luxury apartments and restaurants. Across the street is Lofts 640, a former factory converted into luxury apartments, and whose neighbors include two Marc Vetri restaurants and a Stephan Starr outpost. Up another couple blocks is the Metropolitan Opera House, a beauty from 1908 that’s partially used as a church, and is slated to see the addition of a music venue, art gallery and restaurant as well. And don’t forget the 1926 Thaddeus Stevens School, where a two-story art school

and luxury apartments are planned. That’s not all; Blumen-feld has also envisioned a new public school campus on the four acres he owns behind the Divine Lorraine.

The plan is ambitious, and Blumenfeld speaks exuber-antly about the possibilities. “Look where you are,” he says, pointing to a map of North Broad Street. “You’ve got Temple [University] and City Hall and you have a plethora of really beautiful old factory buildings that have suffered from obsolescence.” Many of these old factory buildings, as well as the school, opera house and hotel, are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, making Blumenfeld’s projects eligible for rehabilitation tax credits offered by the federal government. With this financial boost, the redevel-opment of North Broad Street has become more realistic. No construction has begun, but Blumenfeld is nearing the final planning stages for the Thaddeus Stevens and Divine Lorraine buildings where he has already done significant clean up.

“It starts with looking at something like these buildings. They tell sto-ries,” says Blumenfeld. “You can’t walk through the Metropolitan Opera House without hearing the walls telling stories. Once you get sucked into that vacuum, there is no turning back. You can’t be for tearing that down. You have to be for how do we recreate it?”

2 0 GRIDPHILLY.COM M A R C H 2 0 1 3

Divine Lorraine Hotel photo by: Chandra Lampreich

Metropolitan Opera Housephoto by: Yves Marchand & Romain Me!re

![Page 7: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/7.jpg)

In the 1970s, Linda Richardson was pursuing a career as a professional dancer and actress. But the North Philadel-phia native soon realized that communities of color and women’s organizations—both of which she was a part—didn’t have the networking connections to get funding for their work.

In response, Richardson founded the African Ameri-can United Fund, which provides grants to small social, economic and cultural organizations. As part of United Fund’s work, she helped create the Avenue of the Arts, which includes the North Broad Street Joint Venture—a coalition of African-American cultural institutions on the 2200 block of Broad Street. As Richardson began rehab-bing rowhomes for the Venture, she heard from neighbors that the Uptown Theater, located on the same block, was deteriorating.

Built in 1929 in the Art Deco-style, the Uptown Theater was once a hub for African-American pop culture, hosting acts like James Brown, Stevie Wonder and Martha and the Vandellas. But after closing in 1978 (with a brief reopening in the ’80s), the theater went from cultural center to dete-riorating landmark. In 1982, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

“We were saving the Uptown,” says Richardson about her initial reasoning for taking on the project. “We didn’t consider ourselves preservationists in the traditional sense of the term because we thought of preservation [as]

stodgy—maintaining Independence Hall. But we are pres-ervationists.”

With support from the community, Richardson formed the Uptown Entertainment and Development Corporation (UEDC) in 1995. Under her leadership, the nonprofit raised enough money to stabilize the building, repair the roof and, in 2002, purchase the theater. UEDC is now finishing the Entertainment and Education Tower, a 19,000-square-foot space, which will be available for rent, while continuing to raise money to restore the auditorium and balcony.

Richardson initially created UEDC to save the Uptown, but her vision has expanded. “I think that the building is just not a preservation in the traditional sense,” she says, “but a catalyst for community change, heritage, tourism, sustainability and more importantly, jobs for members of our community.”

UEDC holds neighborhood clean-up campaigns and youth training programs for careers in the music and en-tertainment industries. They’re also developing an African-American heritage trail that will link 21st century cultural sites along a walking and biking path.

“We see ourselves not in the traditional preservation,” says Richardson, “but in sustaining a culture and history and development of heritage tourism.”

Uptown Theater, 2233 Broad St., philadelphiauptowntheatre.org

LINDA RICHARDSON | UPTOWN ENTERTAINMENT AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION

FEB26

African American Historic Preservation Trail Project Pilot This panel discussion will discuss the economic and social impacts of neighborhood improvement, historic preservation and cultural enrichment. Hosted by the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, the panel kick-offs the implementation phase of the African American Historic Preservation trail project.

Tues., Feb. 26, 5:30-7:30 p.m., free, African American Museum, 701 Arch St. For more information, visit philadelphiauptowntheatre.org

M A R C H 2 0 1 3 GRIDPHILLY.COM 2 1

Uptown Theaterphoto by: Yves Marchand & Romain Me!re

![Page 8: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/8.jpg)

But among endangered churches, 19th Street Baptist, designed by the firm of eccentric ar-chitect Frank Furness, stands out—as much for its green serpentine stone as the DIY strat-egy employed by the community to ensure the church’s survival.

Early photographs show the steeple reach-ing well over one hundred feet high, but today only a section of the tower’s stone base remains, and a fence cordons off the entire building due to the crumbling façade. When the Depart-ment of Licenses and Inspections threatened

to demolish the church, a few members of the congregation decided their only alternative was to stabilize the structure themselves.

Typically, before repair work can begin on a historic building, a preservation plan must be in place, engineers

must be consulted, and fully insured contrac-tors vetted. These were simply untenable pre-requisites for 19th Street Baptist, where large patches of sky were visible through holes in the church’s roof, and plants had begun to grow up from the rotting floorboards. “Those of us with trade skills, we got together and said, ‘Look, how do we keep this building from fall-ing down?’” recalls Butler.

Aaron Wunsch, a University of Pennsylvania professor in historic preservation, explains that many of the city’s worthy buildings have been

lost because their stewards wouldn’t roll up their sleeves. “There is such a thing as a grass-roots, hands-on approach to preservation that necessarily complements the institutional ap-proach,” he says.

Wunsch helped the congregation apply to the National Trust for Historic Preservation for a modest emergency repair grant. Then, last winter, Wunsch, Butler (a carpenter), parishio-ner Vincent Smith (an electrician) and Deacon Blackson filled a pick-up truck with sheet metal and lumber at Home Depot, and began to devise an ad-hoc system to patch the church’s roof.

Over a few weekends, and with under $5,000, they sealed the roof, buying time to raise funds for a formal restoration (former Mayor W. Wil-son Goode has helped with fundraising efforts). “It’s true, one of us could have fallen off the roof as we stripped off the rotten asphalt,” Wunsch admits. But the risk has paid off—the building is saved.

Look around us—churches are dropping like flies,” says Lloyd Butler, a deacon at 19th Street Baptist Church

in South Philadelphia. It’s a familiar story in a city with some 200 vacant churches; shrinking congregations can’t meet maintenance costs for their old buildings, which sit boarded up until the rare chance they might be reused. In some cases a developer will buy out the congregation, knock down the church and build new housing. Butler says he witnessed four demolitions last year alone.

STORY BY JACOB HELLMAN PHOTOS BY PETER WOODALL

SAVING GRACEA congregation rolls up

THEIR sleeves and saves their church

2 2 GRIDPHILLY.COM M A R C H 2 0 1 3

GR ID + H IDDEN C ITY

The historic 19th Street Church was in serious disrepair before congregants took it upon themselves to repair the roof.

![Page 9: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/9.jpg)

M A R C H 2 0 1 3 GRIDPHILLY.COM 2 3

820 North 4th StreetPhiladelphia, PA 19123215.389.0786

www.greensawdesign.com

facebook.com/[email protected]

JOHN MILNER ARCHITECTS, INC.www.johnmilnerarchitects.com

NEW DESIGN PRESERVATION RESTORATION RENOVATION

![Page 10: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/10.jpg)

Nearly every detail—interior and exterior—of Larry and Jean Andreozzi’s 10-bedroom house is precisely restored, as if time hadn’t touched the home since it was built in 1894.

Actually much of Overbrook Farms, the West Philadelphia neighborhood tucked along the city’s border with Montgomery County, feels a lot like it did when tycoons, politicians and industrialists built it as the first Main Line suburb in the late 19th century. Stone houses with gables and manicured lawns sit on quiet, tree-lined streets. “The houses had their own individual architects, marvelous craftsmanship, and marvelous building materials,” says Andreozzi, standing near a door frame of quarter-sawn oak that he’s lovingly restored. Andreozzi is a master woodworker, and for the past 15 years this house has been his hobby.

GR ID + H IDDEN C ITY

STORY BY STEFAN KAMPH PHOTOS BY ALBERT YEE

historical disputeof Overbrook Farms be resolved?

Will the stalled designation

24 GRIDPHILLY.COM M A R C H 2 0 1 3

![Page 11: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/11.jpg)

“people come to our house and see the value of restoration,” he says, looking up the original staircase at a huge stained-glass window. An-dreozzi is one in a group of residents pushing for the City to designate the neighborhood as an historic district on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places. This recognition would prohibit demolition and legally require the owners of the more than 400 homes to keep their street-facing exteriors looking more or less the way they did a century ago. In 1984, the neighborhood was named a national historic district, but that designation doesn’t protect buildings from being torn down or altered. Since then, two architecturally significant houses have been demolished and others have been converted to boarding houses for St. Joseph’s Uni-versity students.

Despite the cultural value an historical desig-nation brings to a community, the path to district recognition hasn’t been easy. Some residents and businesses worry that their freedom—and money—are threatened by well-meaning preservationists. Meanwhile, the Historical Commission, which City Council authorizes to protect the city’s architectur-al heritage, lacks the staff capacity or political will to take a stand. THE THREAT OF DESIGNATION

In 2004, members of the Overbrook Farms Club decided to seek historic district recognition from the City. The process got off to a smooth start, and club members held a fundraiser to pay for a con-sultant to write the nomination. But after a blister-ing political battle over the historic designation of another West Philadelphia neighborhood, Spruce Hill, the commission’s work on the Overbrook

M A R C H 2 0 1 3 GRIDPHILLY.COM 2 5

Your Food. Your Farms.

Your Community. Your Connection.

Your Co-op.

Chestnut Hill8424 Germantown Ave.

Mt. Airy559 Carpenter Lane

Across the Way610 Carpenter Lane

A member-owned food cooperative open to all.

Weavers Way

Attention Urban Farmers!Henry Got CompostTwo cubic yards of dairy barn blend compost $75. Delivered within PhiladelphiaContact [email protected] or call 815-546-9736 A Collaboration of Weavers Way Co-op and Saul High School

Larry and Jean Andreozzi live with their family in a 10-bedroom home built in 1894. For Larry, a master woodworker, the home

has been his hobby for the past 15 years.

![Page 12: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/12.jpg)

Farms nomination faltered. It was left uncon-sidered for seven years.

Finally, in 2011, after renewed pressure by the Overbrook Farms Club and the Preservation Alliance, commission staffers began to review the nomination in preparation for the designa-tion committee to vote on approval. At this late point in the designation process it’s typical for the commission to make sure property owners don’t suddenly alter or demolish their buildings. So, in September 2011, the commission informed homeowners by letter that they’d have to ask the commission for permission to make any sub-stantial modifications to their homes, effective immediately.

In a season where anti-government Tea Party protests dominated headlines, this was not good press for the preservation effort. RJ Krohn, a resident and the electronic musician known as RJD2, circulated a petition opposing the effort. Dozens of residents turned up to a November 2011 hearing to voice their opinions. One resi-dent said he thought designation amounted to the Historical Commission “taking his property without compensation.” Another called the club members behind the nomination “Nazis.”

V. Chapman-Smith, an historian at the Na-tional Archives, joined in opposition to the district. She says she appreciates her house’s historical detail—she spent $8,000 carefully restoring her front porch—but is worried that some residents wouldn’t be able to afford this burden. She also worries that the city wouldn’t let people update their homes for things like en-ergy efficiency. “The original owners saw that house as an organic thing, never staying exactly the way it was when they first built it,” she says now, more than a year after neighbors began to organize against the district. Without such ad-aptations, she explains, a neighborhood would

become obsolete. “If we save everything, we kill ourselves.”

One of the most vocal op-ponents to the district was the Talmudical Yeshiva of Phila-

delphia, a rabbinical school that has consid-ered expanding its campus. The yeshiva owns several historic houses that are included in the nomination. While the school has already torn down one architecturally significant house, the historic district designation would prevent them from demolishing others.

The grassroots effort soon drew the attention of the then-new Fourth District Councilman Curtis Jones, Jr., who represents a wide swath of West Philadelphia including Overbrook Farms. “People were divided on the issue of historical certification,” he says. “People that were against it expressed to me... that the recession was im-peding their ability to repair their home. So I listened to both [sides].”

THE ALL-POWERFUL CITY COUNCIL Jones has asked the commission to table the dis-cussion until his constituents could get more information. “This is the kind of designation that once you do it, you have committed to a di-rection for the neighborhood,” he says. “Rather than act in haste, I wanted to give people anoth-er opportunity to discuss it, to reach a mutual compromise.”

Five months later, following Jones’ request, Alan Greenberger, the City’s commerce direc-tor and a deputy mayor, sent a letter to the commission instructing them to put aside the nomination process until his office could con-nect with all the interested parties. That’s where the process stalled.

In an old, unwritten custom called “coun-

GR ID + H IDDEN C ITY

Rules ®ULATIONS

When properties are listed on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places, owners must follow certain regulations.

All exterior alterations must be reviewed by the Historical Commission before any work can take place. This includes:

! Demolitions (partial or complete) ! Additions ! Installation or alteration of decks, fences, awnings, signs and mechanical equipment ! Repair, replacement or removal of architectural features ! Replacement of windows, doors and roofing materials ! Masonry cleaning and repointing ! Painting of facades

Historical Commission approval is not needed for:

! Interior alterations* ! Repainting wood and metal trim ! Replacing clear window glass ! Landscaping and tree trimming ! Seasonal decorations

*Department of Licences and Inspections will refer all building permit applications to the Historical Commission to confirm that proposed interior changes do not affect the exterior of the building.

Properties listed on the Philadelphia Register are not required to:

! Undergo restoration or reverse alteration made to the building before the time of designation ! Be open to the public

Architectural details from homes in Overbrook Farms.

![Page 13: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/13.jpg)

M A R C H 2 0 1 3 GRIDPHILLY.COM 27

Get to know the faces behind your food. Phila, PA | South Street

215 - 733 - 9788

Phila, PA | Callowhill215 - 557 - 0015

Wynnewood, PA610 - 896 - 3737

Devon, PA610 - 688 - 0015

North Wales, PA215 - 646 - 9400

Plymouth Meeting610 - 832 - 0010

Jenkintown, PA215 - 481 - 0880

Glen Mills, PA610 - 385 - 1133

Marlton, NJ856 - 797 - 1115

Princeton, NJ609 - 799 - 2919

215-478-6421

generation3electric.com

Licensed

& Bonded

PA015898

Get Plugged Into a

Greener Philly with Gen3!

Electrical Services | Powerful Solutions

Knowledge & Expertise

MG REAL ESTATE GROUP

specializes in adaptive reuse of industrial buildings into art,

design, IT/tech, live/work space.

analysis available to individuals or groups to help identify and acquire potential properties.

Call Theresa Stigale, Broker: 215-928-0221.

![Page 14: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/14.jpg)

cilmanic prerogative,” City Council members almost always vote on specific development projects in agreement with the councilperson who represents the district in question. By con-sequence, these elected officials hold powerful sway over the physical development of their districts.

Councilman Jones says that by nature he tends not to be heavy handed about making de-mands of City agencies and that his interest isn’t in derailing the process. “I have an opinion, and it’s just one of many. I’m thankful to them for respecting it.”

The reality, however, is that the commission was given its powers by City Council, which also controls its annual budget of around $385,000—barely enough to keep staff on top of the build-

ings and districts presently on the Philadelphia Register, let alone process applications for new ones. Council has the power to dissolve the com-mission or cut its funding. And recent history shows that when a councilperson opposes his-toric designation, the commission won’t press its case too hard.

A decade ago, when Spruce Hill residents sub-mitted what many in the field considered a text-book nomination to turn their neighborhood—one of the nation’s first Victorian-era streetcar suburbs—into an historic district, the district councilperson Jannie Blackwell introduced a bill to City Council. The bill, which ultimately was unsuccessful, would have taken the power to designate historic districts away from the His-torical Commission and given it to City Coun-cil. Had the bill passed, council members would have gained near-complete authority to block preservation efforts in their districts. Though

Anyone can nominate a building for historical preservation and in fact, many city landmarks wouldn’t be here today if not for local residents, students, community groups and nonprofits. Historic preservation happens on the city, state and national level, but only properties listed on the Philadelphia Register for Historic Places are protected from adverse alterations and demolition. For more information, visit preservationalliance.com

ORDINANCE AMENDED to include structures, sites, objects and historic districts

A History of Philadelphia’sHistoric Register

1955 1983

SPECIAL LEGISLATION IS PASSED to create the Manayunk Main Street Historic District; the city’s first recognized historic district

1985

PHILADELPHIA HISTORIC COMMISSION founded and first historic preservation ordinance passed in Philadelphia— only protects individual buildings.

GR ID + H IDDEN C ITY

JUNE 1971 Swann Memorial Fountain in Logan Circle protected as an historic landmark

JUNE 1957 Thomas Mill Covered Bridge over Wissahickon Creek protected as an historic structure

2 8 GRIDPHILLY.COM M A R C H 2 0 1 3

The home of Stephanie Kindt and the original building plans from circa 1900.

![Page 15: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/15.jpg)

PENNSYLVANIA HISTORICAL MARKERS ! Commemorate people, places and events of national or

statewide significance. Historic buildings don’t need to be standing.

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS ! Places designated by the Secretary of the Interior

as nationally significant ! 67 in Philadelphia

NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES ! Places designated by the National Park Service as having

national, statewide or local significance ! 500 individual properties and 600 historic districts in

Philadelphia

To view the Register, visit: phila.gov/historical/register.html

ORDINANCE AMENDED to include public interior spaces

2009 2010

CITY COUNCIL CHAMBERS first interior listed in the Register of Historic Places

WHAT’S ON THE REGISTER?

! More than 10,000 historic properties

! 14 historic districts ! 2 historic interiors ! Includes: homes,

churches, hotels, apartment buildings, cemeteries, bridges, street surfaces, parks, stores, watering troughs

PRESERVATION EASEMENTSVoluntary donation by a private owner to an easement-holding organization, such as the Preservation Alliance. This protects the property from demolition or adverse alterations by current or future owners.

PROCESS ! Nomination made to the Historical

Commission. ! Committee on Historic Designation

schedules a meeting to determine approval of the recommendation. 3 to 4 months

! If the committee approves, the recommendation is passed to Historical Commission for review and action. 1 to 2 months

PLUS

Blackwell’s bill failed, it effectively derailed the Spruce Hill nomination—the commission didn’t appear willing to fight Blackwell, even though it technically could have—and a decade later it casts a shadow over the Overbrook Farms case.

With only six staff members and a budget that pales in comparison to other big cities, the com-mission focuses most of its resources on what it considers its most important role: reviewing permit applications for buildings already on the Register. In addition, the commission has been fighting three contentious appeals over historic properties that could be demolished. “We simply don’t have the staff capacity to meet all expecta-tions,” says Jon Farnham, the Historical Com-mission’s executive director. “The vast majority of the staff ’s time is spent reviewing applica-tions. That’s what we do day-in, day-out.”

But on top of being hamstrung by its small budget, as long as Overbrook Farms remains ta-bled, the commission has been reticent to tackle new building and district nominations. “There’s this sort of unspoken understanding that they’re not going to move on any of the dozen or so nomi-nated buildings or the long-waiting Washington Square West district until they resolve what’s go-ing on at Overbrook,” says Ben Leech, advocacy director at the Preservation Alliance of Greater Philadelphia. “There are fates of buildings hang-ing in the balance.”

THE FUTURE OF OVERBROOK Despite all the talk about government intrusion, real preservation can’t be mandated by an over-stretched city agency. It will always depend on the care of the individual homeowner. If every-one had the passion and resources of Andreozzi, their houses could be as well-preserved as his.

Andreozzi points out the meticulous tile mosaic in the entry foyer, and the ornate egg-and-dart mantelpiece. These kinds of extrava-gances are part of the city’s three-century-long architec-tural heritage. Once they’re gone, they’re gone. But trea-sures like these are all over the neighborhood, in houses of the wealthy and the mid-dle-class, both neglected and lovingly preserved. “Every house, in its own little way, is just like this house,” says Andreozzi.

Councilman Jones says that other issues affecting his district are taking precedent over dealing with the historic district conflict. Anyway, he says, it is the Historical Com-mission’s turn to act. “We

anxiously await them. The ball is in their court.” Farnham says he is trying to figure out how

the commission might make an Overbrook Farms district easier to swallow. Possible chang-es include slight modifications to the district’s boundaries or relaxed standards for renovations that are not visible from the street.

Meanwhile, according to City ordinance, those temporary restrictions outlined in the letter that got everyone fuming in late 2011 will remain in effect until the Historical Commission takes up

MARCH 2012 Penn Treaty Park protected as an historic site

In addition to protecting buildings on the city level, there are also state and national protections available.

National Registers State and

M A R C H 2 0 1 3 GRIDPHILLY.COM 29

The tile mosaic in Larry Andreozzi’s home.

![Page 16: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/16.jpg)

GR ID + H IDDEN C ITY

CITY HALL—now a crisp white icon, but it was only last year that the building’s restoration was finally finished, undoing a half-century of neglect. Built with some 88 million bricks, the res-toration treated 200,000 square feet of masonry, 680 windows and 250 sculptures. The project drew on an army of building conserva-tion specialists, and employed some of the industry’s most advanced techniques. It’s no wonder the process took a decade.

Modern conservation is a science, but it often must begin from a position of ignorance: old materials are simply unpredictable. City Hall’s tower is made from white Massachusetts Lee marble. But the building’s 30-year construction period was during the coal-burning era and when finished, City Hall was covered in soot and appeared gray. Press accounts even described it as limestone. To determine the appropriate cleaning technique the masonry restoration contractor tested inconspicuous spots to learn what worked, what didn’t and what might damage the stone. Ultimately, explains Nan Gutterman, who works for Vitetta, the architecture firm that oversaw the proj-ect, they settled on a “low-pressure micro-abrasive system at 25 to 35 psi”—colloquially known as sandblasting.

While the tower’s bronze sculptures can’t be seen without scaffold-ing, they’ve also been restored to original detail from patina-encrusted oblivion. In the hundred years since they left Alexander Milne Calder’s studio, micro-crevices in the metal’s surface collected impurities and

hastened freeze-thaw cycle deterioration. Here, the Polish-trained conservator Andrzej Dajnowski imported a German laser technology never used on this scale. The laser’s beam not only vaporizes dirt, but re-melts a thin surface layer of the metal, eliminating the pitting from the casting process and making it literally better than new.

City Hall and other monumental buildings aside, Philadelphia is a city of brick rowhouses. A humble material, brick does not call forth glamorous conservation techniques, but this is why Brett Sturm, a student in materials conservation in the University of Pennsylvania’s historic preservation program, was drawn to it. “Brick is fascinating,” says Sturm. “It’s used in the 21st century exactly as it was used for the Tower of Babble—as a fired, modular piece of earth.”

Sturm is finishing his master’s thesis on a defunct brick manu-factory, and explains that the only significant innovation to hit the world of bricks involves the way they’re fired. Kilns were once highly unpredictable; cold spots produced under-fired bricks that eventually crumble. Around the middle of the 20th century, ceramic engineers developed modern tunnel kilns, which put out denser and more robust bricks. Even with old brick, though, conservation is largely a matter of keeping roof and gutter leaks from washing out mortar, and an occasional re-pointing.

If you’ve got an old rowhouse, avoid Portland cement-based mor-tar. Mortar is intended to be a sacrificial buffer, but Portland is less permeable than historic lime-based mortars and doesn’t allow water to pass. Instead, water is forced through the brick, which will eventu-ally deteriorate.

BY JACOB HELLMAN Restoring old buildings

The art and science of

If conservation science interests you, Penn’s program is one of the nation’s best. This summer the university’s Fisher Fine Arts Library (in the restored Furness building) will host an exhibition on the history of brick. Learn more at library.upenn.edu/finearts

the issue again. That means Overbrook Farms is being legally treated as an historic district, and residents need to seek approval for out-side renovations.

With limited resources the commission isn’t in a position to strictly enforce these regulations. It depends on inspectors from the Department of Licenses and Inspections to issue citations, which usually happen only once a neighbor complains. Nobody is patrol-ling the neighborhood, looking for infractions. Councilman Jones says that since fall 2011 he’s received no complaints from constituents about the restrictions. Residents are being left largely alone with their houses and their opinions—though for those who advocate preservation, the rules provide some comfort.

“Right now, we’re de facto under the regu-lations of the Historical Commission,” says Kevin Maurer, board president of the Over-brook Farms Club, who has worked to get the designation passed. “The world has not come to an end.”

Material Issues

3 0 GRIDPHILLY.COM M A R C H 2 0 1 3

An interior view of Stephanie Kindt’s home in Overbrook Farms.

![Page 17: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/17.jpg)

M A R C H 2 0 1 3 GRIDPHILLY.COM 3 1

SIGN UP STARTS MARCH 1ST: GREENSGROW.ORG/CSA

“The food variety is more inclusive than other

CSA’s that contain mostly vegetables. The regular

addition of fruit, dairy, and protein is great!”

“Love the variety— honey,

beer, breads are great fun!”

BECOME A MEMBER IN 2013!

NURSERY OPENS MARCH

2ND!

Progressive Solutions

for tree and land management

610 -235-6691

Now Offering organic lawn care

![Page 18: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/18.jpg)

MODERN LOVE

STORY AND PHOTO BY PETER WOODALL

deserves historical recognition

GR ID + H IDDEN C ITY

This isn’t surprising. The work of our most famous post-war architects, Louis Kahn and Robert Venturi, does little to in-spire public affection, much less love. Both Kahn’s Richards Medical Building (1960) at the University of Pennsylvania and Venturi and Rauch’s Guild House (1963) at 711 Spring Garden Street, are mentioned in most every architecture text book, yet have frustrated many a lay person’s attempt to understand their greatness.!

Each architectural period—Victorian comes to mind espe-cially—has been loathed by the following generation or two, only to be lauded once a certain critical distance has been achieved. We may just now be ready to see the value in the austerity of raw concrete. Witness the recent groundswell of

support for protecting the Police Ad-ministration Building, or “The Round-house,” at 7th and Race Streets built by Geddes, Brecher, Qualls in 1963.!

Easier to enjoy are Philadelphia’s few examples of post-World War II commercial vernacular architecture, none more exuberant than the Thrift-way on Frankford Avenue and Pratt Street at the end of the Market Frank-ford El. Built in 1954 for the Penn Fruit Company, and designed by George

Neff, the store is a glass and steel anomaly amid the brick storefronts of Frankford. Almost all the Penn Fruit stores from this period look more or less alike, but this one is by far the best preserved, and the only one with those marvel-ous candy-colored stripes painted on the ceiling. Let’s look past the everyday use and common form of this striking supermarket and put it on the Philadelphia Register before someone decides to tear it down.!

peter woodall is co-editor of Hidden City Daily. Before that, he wrote a column on dive bars for Philadelphia Weekly, and worked as a newspaper reporter in Sacramento, Calif. and Bioloxi, Miss.

Nowadays, vintage stores are thick with “Mem-bers Only” jackets from the 1980s and car collectors covet the “classic” Honda Civics from the 1970s. But

appreciation develops more slowly when it comes to architec-ture: buildings must be 50 years or older to be eligible for the National Historic Register. In Philadelphia, however, there is no minimum age for a building to be called historic; and good thing because the city has a few late modernist buildings that are worth preserving, but have yet to make the list.!

Why a North Philadelphia Thriftway

3 2 GRIDPHILLY.COM M A R C H 2 0 1 3

![Page 19: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/19.jpg)

Nearly 10 years ago, in 2002, Philadelphia nearly saw the loss of some of its more

unique artwork: the Magic Gardens. A mo-saic wonderland created by visionary artist Isaiah Zagar, the Gardens are considered responsible for helping revitalize the once derelict South Street. So when the owner of the once-vacant lot Zagar’s artwork now occupies announced he would sell, the community immediately responded with support. Their efforts saved Zagar’s work. “Otherwise,” says Ellen Owens, executive director of the nonprofit Magic Gardens, “[the gardens] would no longer be here.”

While Zagar now owns the three main lots, protecting the Magic Gardens is no easy feat. The roughly 50,000 square feet of murals are made from pottery, glass and found objects. They climb over walls (both inside and out), cover shops, alleys and private homes, spreading from the central Magic Gardens site across nearly 33 Phila-delphia blocks—much on private property.

One tool for preservation may be the creation of a “Zagar zone of protection,” an idea posited by Sarah Modiano, a Columbia University preservation student. Modiano sees Zagar’s work as a singular visionary

art environment like Los Angeles’ Watts Towers and Brooklyn’s Broken Angel. Those works—which are discrete sculptur-al installations—have been named national landmarks and thus, given nominal pro-tection. But Owens notes that preserving Zagar’s oeuvre, which is largely integrated in the fabric of the neighborhood, will be a challenge.

In addition to the whims of property owners, the work is subject to seasonal expansion and contraction from rain, sleet and snow, as well as the eager hands of visi-tors. And because of the diverse materials there isn’t a single straightforward method for conservation.

Currently, the sprawling murals are maintained by the spry, 74-year-old Zagar and a lone assistant. The Magic Gardens is now taking steps to assess general conser-vation, a complex undertaking considering the amount of materials used in each work and the artist’s vision. “Isaiah won’t always be able to be the caretaker here,” says Ow-ens, “so we need to be able to understand what he wants.”

Philadelphia’s Magic Garden, 1020 South St., phillymagicgardens.org

Preserving MagicCan Philadelphia protect

Isaiah Zagar’s

STORY AND PHOTO BY DOMINIC MERCIERdazzling folk art?

M A R C H 2 0 1 3 GRIDPHILLY.COM 3 3

![Page 20: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/20.jpg)

In 1971, Philadelphia boxer Joe Frazier won the so-called “Fight of the Century” defeating previously unbeaten and heav-

ily favored Muhammad Ali at Madison Square Garden. But despite being heavyweight cham-pion, Frazier struggled with the ambivalence of fans, many of whom were ardent supporters of the more transformative Ali.

Now, more than a year after his death, Phila-delphians are beginning to reevaluate the boxer’s legacy, with a particular focus on the gym’s posi-tive community impact on North Broad Street, where Frazier touched the lives of hundreds of young men who sought refuge from the streets in the physical training and discipline of boxing.

Last year, Dennis Playdon, a Temple Univer-sity architecture professor, enlisted his students in preserving the gym, which Frazier was forced to sell in 2008 and now houses a discount furni-ture store. The students’ work attracted the at-tention of the National Trust for Historic Pres-ervation, which named the gym to its 2012 list of most endangered historic places and designated it a “National Treasure.” The National Trust has also commissioned a market study to determine future best uses for the site.

Working with the Preservation Alliance of Greater Philadelphia, the students have nomi-nated the building to both the Philadelphia and national historic registers. A listing on the Phila-delphia Register of Historic Places would protect the building from further major alteration or de-molition. Eventually though, Playdon would like to see the gym restored to a workout and training center, a use that resonates with Frazier’s legacy. Grid had a chance to talk with Playdon about the project, the “digital gym” the students are cre-ating, and how sustainability plays a role in the gym’s preservation.

How important is the North Broad community to this project?They loved Joe Frazier. He was like a surrogate father to a lot of people in that area. He was al-ways approachable and helpful when he could be. And [he] was really important to a lot of busi-nesses—he supported people, lent his name to projects and such.

Are there other buildings in Philadelphia important to the 20th century African-American story in Philadelphia?There’s the John Coltrane House. The Blue Hori-zon [boxing venue] has recently been closed and it’s being redeveloped in order to keep the Blue Horizon identity, but redeveloped into something else. Another one is the Uptown Theater, which is one of the oldest African-American theaters in the country, [and] housed huge amounts of history. And they are comparable, although the Uptown Theater is quite beautiful inside.

What is the “digital gym” and how will it aid the larger project of preserving the building?We won a small matching grant from the Na-tional Trust to build a website. Architecture students are really good at 3D modeling, and our idea was to put the gym back together virtually. So you could walk inside through the front door and enter the gym as it was and walk around, look at the walls and the pictures and the people. There would be links to news articles and press throughout the website so you could kind of re-live what it looked like.

This is another way of preserving the gym; to bring it back to what it was. We’ve had a great deal of luck with the movie [When the Smoke Clears, a documentary on Frazier’s life] that was put out. The photographic director has made available to us all the images. Within the next year we will have our website up.

We’re starting to do oral histories that are stories from the people who knew him. We’re getting interesting stuff. When we had a screen-ing of the film at Temple, so many people came along. Among them were former boxers who had trained at the gym with Frazier, and they were young men dressed in suits, which you don’t get much of in North Philadelphia. They came dressed like that because Frazier told them they couldn’t dress any other way. They had to be up-standing citizens to box at his gym. He insisted on proper manners. He brought these kids up.

What role do nationally recognized historic spaces play in Philadelphia’s sustainability initiatives?Well, it’s part of Philadelphia’s identity. We have a lot of complaints about the imaginary Rocky, which was based in part on Frazier’s life… The gym is really important to the Frazier identity. The mayor’s office plans to erect a bronze [statue] at the sports stadium, but these are small efforts; the sort of ground zero is the gym. When you have a world champion in your midst, it’s usually an important figure.

Preservation is about taking things forward rather than going backwards. We preserve build-ings because they’re part of how we identify our-selves with our city… It’s only recently that the National Trust and preservation organizations have added the category of the importance of cul-tural identity to preserve buildings.

Sustainability doesn’t stop with materials and things. Sustainability also has to do with the bringing forward of places. And [that has] to do with all of the people who’ve made the city what it is now. To ignore that and to only think of sustain-ability [as] materials and climate is to leave out the most important part—the cultural. Preservation is the design of the future. It’s the background we’ve made in order to make the future.

BY MOLLY O’NEILL

UNDISPUTED CHAMPIONS

Temple students

for Smokin’ Joe’s gymmake the case

GR ID + H IDDEN C ITY

3 4 GRIDPHILLY.COM M A R C H 2 0 1 3

![Page 22: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/22.jpg)

It could have been a scene from the film The Money Pit. Christine and Anthony Shippam, owners of an 1894 Georgian Revival in Mount Airy’s Pelham

neighborhood, were lying in bed, rain dripping down on them. “Honey, did I tell you how much I hate this house?” asked Christine.

“Did I tell you how much I hate this house?” replied her husband Anthony.

“We don’t take vacations. We don’t do anything else,” says Christine Shippam, five years into the project restoring what was one of the dozens of suburban dream houses designed by architect Mantle Fielding. “It’s become an addiction,” she says.

Like any addiction, this one forces its sufferers to make ap-parently irrational choices: refashioning every single detail of the house’s exterior to appear authentic, circa 1894; rehanging every door and window; and hunting out restored period-cor-rect hardware instead of buying contemporary copies.

And yet the Shippams practice a rather sophisticated phi-losophy of restoration. “Leave the scars,” says Christine. “If you can’t fix it, let it be.” They figure there will be future stew-ards of the house compelled to pick up on things they’ve left un-restored.

For a time, the preacher Sweet Daddy Grace, founder of the

The addictive nature

GR ID + H IDDEN C ITY

Preservation Madness

STORY BY JOSEPH G. BRIN PHOTOS BY ALBERT YEEof home restoration

United House of Prayer for All People, lived here. The Shippams preserved Grace’s “On Air” sign in the red, white, and blue radio room. Neighbors say the columns out front also were once painted red, white, and blue in the style of barbershop poles.

When the Shippams bought the house, they found all the woodwork ru-ined by textured paint and dogs. “There have been times,” says Christine, “when we’ve totally given up hope. But you can’t stop. You can’t back out of a commitment.” All the while friends and family keep asking, “why aren’t you finished?”

Since the project began in 2008, the Shippams have weathered dust and dirt, break-ins and self-doubt, difficulties cushioned by a sense that the neigh-borhood itself has begun to improve. “People caring, that feels good. It helps others,” says Christine.

But when asked if she could imagine the day when the house was finished and the years fighting with contractors, tracking down replacement parts, and discovering seemingly endless problems were over, will she be happy to sit back and relax? Her answer: “It would be lonely.”

3 6 GRIDPHILLY.COM M A R C H 2 0 1 3

Christine and Anthony Shippam are five years into restoring their 1894 Georgian Revival home in Mount Airy and the end isn’t in sight.

![Page 23: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/23.jpg)

484-593-4262Altern-Energy.comSmall business /Independent ownership

PORTABLE OFF-GRID POWER FOR:Power outages, events/concerts, cabins, construction, tailgating. Or use daily to power parts of your home or business

SOLAR WITH BATTERY STORAGE: Daisy chain and wind options

PLUG & PLAY SIMPLICITY!

NO NOISE/NO FUEL/NO FUMES

30% FED. TAX CREDIT ON SOME MODELS

RENEWABLEENERGY GENERATORS

DISCOUNT FOR NON-PROFIT AND HUMANITARIAN USES

Killer Wood-Fired Flatbread,

Alchemic Housemade Beer,

World-Class Wine

EARTHbread

+brewery

7136 germantown ave. (mt.airy)215.242.6666 / earthbreadbrewery.com

Handmade Soda,

Microbrewed Kombucha,

Zero Gigantic Flatscreen TVs

Live Music every 2nd + 4th Sunday

Geechee Girl Catering Party at your place or at ours.

Innovative Low Country Cooking at it’s best!

“One of Philly’s most personal and unique BYOBs.”

Philadelphia Inquirer

6825 Germantown Ave. Philadelphia, Pa 19119 . 215-‐843-‐8113

www.GeecheeGirl.com

1. When the inside of your home feels like a cozy retreat.

2. Making your home’s heating and cooling system work better than ever.

me feels like a cozy retreat.

g and coolinger.

HVAC upgrade noun (!ch vak up・gr!d)

Schedule your Comprehensive Home Energy Assessment today. It's your first step towards saving money, saving energy and living more comfortably. Get started now for just $150.

215-609-1052

EnergyWorks is a program of the Metropolitan Caucus of Bucks, Chester, Delaware, Montgomery and Philadelphia counties, and is supported by a grant from the U.S. Department of Energy.

M A R C H 2 0 1 3 G R I D P H I L LY.CO M 4 1

![Page 21: Grid Magazine [#047]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052511/568bf19b1a28ab893393c06f/html5/thumbnails/21.jpg)

![Grid Magazine March 2015 [#071]](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/568cabdf1a28ab186da74984/grid-magazine-march-2015-071.jpg)

![Grid Magazine (Hidden City cover feature) [#047]](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/568c4de21a28ab4916a5b673/grid-magazine-hidden-city-cover-feature-047.jpg)

![Grid Magazine July 2012 [#039]](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/568c49401a28ab4916937076/grid-magazine-july-2012-039.jpg)

![Grid Magazine May 2013 [#049]](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/568bd5441a28ab203497d277/grid-magazine-may-2013-049.jpg)

![Grid Magazine August 2012 [#040]](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/568c4ba01a28ab49169cee23/grid-magazine-august-2012-040.jpg)

![Grid Magazine April 2015 [#072]](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/568cad9f1a28ab186dac707f/grid-magazine-april-2015-072.jpg)

![Grid Magazine October 2011 [#031]](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/568c0ef41a28ab955a925fe2/grid-magazine-october-2011-031.jpg)

![Grid Magazine April 2012 [#037]](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/568c46cb1a28ab49168b48a6/grid-magazine-april-2012-037.jpg)