Grassi Avant-Garde and Continuity

-

Upload

josef-bolz -

Category

Documents

-

view

352 -

download

20

description

Transcript of Grassi Avant-Garde and Continuity

-

Avant-Garde and Continuity

Giorgio Grassi Translation by Stephen SartareUi

This discussion will be largely focussed about two basic issues: 1) that avant-garde architecture itself is of minor importance. It is always marginal to any decisive change--despite the fact that its importance bas been exaggerated to an absurd degree by militant criticism, and even though it has been taken seriously by many, both in the past and today; 2) that the avant-garde position in architecture contradicts the very definition of architec-ture; that is to say, it is contrary to architecture's most specific characteristics; factors which cannot be over-looked in the projection of architecture, not even when the contradiction between architecture and the city, or between humanity and the reality of its product, is as much in evidence as it is today.

And since we are talking about the avant-garde in archi-tecture, we should also mention in passing something that is often forgotten. We should remember that we are talk-ing aboutwork8, about concrete matters-not about ideas, fantastic images, or polemical issues. The SchrOder house and the Villa Sa voye are there to be seen; they are not just manifestos or ideal models-they are "houses," de-signed to be used; they are connected to everyday life. And even that which is not yet built, but is sill! only in the planning stage, must be imagined in tenns of its com-pletion, for this is really architectwe's only raison d'etre. But the first thing we must do is rediscover an acceptable frame of reference.

To my mind this law establishes above all that in great works (in sculpture but especially in architecture) the "monument'' comes first. In my opinion, the most general and comprehensive conception of a work is always aimed first of all at the t-eaflinnation of the specific nature of the particular type of represe.ntation, be it sculpture or ar-chitecture. or primary impottance is t he "monument,'' that is, the law of architecture.

All the rest is really secondary; that is, it has no bearing as such on t he conception. It becomes irrelevant with respect to the "work." For this reason all the rest may easily become the object of the most obstinate and fanat-ical experimentation, or of the most sophisticated critical revelation. It may even have a price, as it does. It may be exhibited in galleries, discussed in seminars, offered for the wonderment of a public-a public which has how-ever been shrewdly turned away from the real object of its perception and judgment. Taking the whole gamut of forms proposed by the van-guards of the Modern Movement, I believe that if we try to imagine the exclusion of this "rest'' (that is, of all that which crumbles and disintegrates in the fall prescribed by Michelangelo), there remains indeed little, if anything at all , of all the various proposals made with regard to formal transformation and innovation.

Of course there remains the excitement, the desire for In referring to the "architects of the revolution," I point change, the intensity of experimentation, and so on, the to the various experiments of the Modern Movement's concern for lifestyle, the conllict of polemics, factions, or canonical vanguard, as well as the greater part of contem- ''tendencies"; but all of this exists only in the pages of porary experimentalism, which share in common the sin- books. gular aim of searching for "new form."

What I'm trying to say is that, if perchance one wants to There is a requirement, as shocking as it is terrifying, build a house, one should certainly not look for t he ex-that Michelangelo prescribed for sculpture, which goes emplar among those strange objects which awaken our more or less like this: "A beautiful stattw nust be able to sense of wonder! On the contrary one should be very wary roll down frcnn the top of a monntain, tuilh01u losing of them.

a~ything of importance." This is a very powerful image, worthy of Michelangelo, charged with theoretical impli- If we consider even for a moment the real changes-the cations, intended to create uproar-and a convincing edict growth and transformation of cities, of their purposes,

391

as well, because it tends to coincide with the law of nature. and of their fonns, the modification of ~~ ly.~~~r atenal

-

1 Student housing at Chieti. Gi11rgio Gra.ssi and Antonio Monesti.roli, 1980. Perspective view of arcade and site plan.

392 etc.-we readily realize that all of this always comes about fore the recognizability) of the forms themselves could be despite the contributions of the so-called avant-gardes, exhausted. and not because of them.

Here, by way of example, 1 should like to oppose the transformations within the Neoclassical city to the designs of the "architects of the revolution," who are all too often invoked in support of the experimentalism of modem ar-chitectures. I should like to go on to oppose the Hamburg of Fritz Schumacher, or the Frankfurt or Ernst May, or even the Viennese housing blocks carried out under the socialist administration of the twenties, to the entire avant-garde of the Modern Movement, to all of European expressionism, to all the ''isms" and their derivations.

In other words, the real transformations brought about by architecture have always begun with the specillc pract-ical and material conditions of the city and the st.ructure of its el.ements-and always as a denial of any "leaps of wgic" that may be advanced. And nowhere is it said that architecture, for all this, has stayed on the right path! On the contrary.

I ask myself what relation is there, for example, between the archi tecture par/ante of a Ledoux and the transfor-mations of the city that succeeded it? I ask myself what relation is there between these "new forms" and the Ne

-

Didn't this preeminence derive from the fact of its being the unequivocally "formalistic" nature of the dominant 393 "construction," that is, "composition" par excellence, in superstructure. that it was subject to the fixed laws of nature? Cubism, Suprematism, Neoplasticism, etc., are all forms of investigation born and developed in the realm of the figurative arts, and only as a second thought carried over into architecture as well. It is actually pathetic ttl see the architects of t hat "heroic" period, and the best among them, trying with difficulty to accommodate themselves to these "isms"; expetimenting in a perplexed manner because of their fascination with the new doctrines, mea-suring themselves against them. only later to realize their ineffectuality. This is the case of Oud when faced with "De Stijl." It is the same for llfies. Few are inunune to it: Loos, Tessenow, Hilberseimer. I emphasize this point be-cause it seems to me that today, amid all the confusion, a strong avant-gerde wind is again blowing our way!

The "isms" of the Modem Movement have certainly pro-duced a bulk of material impt-essive for its variety and novelty. We must recognize that for the most part con-temporary architecture still bases its formal choices on this material. Hardly a reassuring sign! But how else does one explain for example the recent fortunes of a Terragni, studied today in the United States as though he were

Vitru,~us? The illusion, the myth of the "new" persists. And it renews itself in the most negligible, the most idi-otic, historicist p(Ultickes. Here I do not intend to go into the histotical and ideolog-ical motives behind the "formalistic" choices of the modem vanguards. But in the face of the new definitive rupture between architecture and the contemporary city, can any-one still think that the option of denunciation or protest is a valid one in itself?

Moreover, the situation today is this: the dominant cul-tural superstructure is incapable of expressing collective meanings. It is therefore incapable of creating architec-ture, since architectwe is always the expression of such meanings. In this sense, architecture in itself is in a state of perpetual denunciation, as it were, as a consequence of

This nature is made manifest whenever the superstruc-ture shows itself to be open ttl, that is, ready to appro-priate and include within its own expressive horizons, those formal experiments in the realm of architecture whose values at-e posited only in formal terms. In this light, is not the search for a "new form" the most para-doxical choice of all, even if it .be the most obstinately pursued?

A superstructure which tends to the reactionary always approves of everything that conforms to its own chru-ac-teristic stylistic preferences, that is, to everything that serves to dissimulate contradictions rather than expose them: such as formal experimentation as an end in itself, innocuous heresies, autobiographism, etc. Such a super-structure seems to have a particular predilection for all that is expressed ambiguously, or in an incomplete or provisional way~ne need only think of the success of the so-ealled "papet architecture." For this reason, it is in my opinion all the more absurd to give credence to or to get involved with that area of architectural research which more or less openly makes ambiguity its program, or focuses on experimentation as a search for unusual and peculiar connections, nuances, abnormalities, and so forth.

Therefore, any choice made in full consciousness of its opposition to the state of the contemporary city today must first of all be evaluated in light of this specific prob-lem. It must take stock of architecture in itself, as a t-eal and positive altemative: that is, architecture as an instru-ment with which to probe contradictio.n.

I believe that for architecture today to enter, in a teal sense, into conflict with the cultural superstructure ac-cording to which it is judged, it must be unambiguous, to the point of didacticism, and not vague or indistinct. I believe that research, especially at the present moment, must be concentrated on proposing forms that can be interpreted in only one sense. And this "sense" must be consistent with the object of representat' Qn. h d 1 opyng te matern

-

394

2 Fmmhouse in lhmbardy. 9 Alles Museum, Berlin. K. F. Scltinirel, 1823-JO. Pespective view of atrimn inteior.

-

~ State Scltool at K/.ostsc/1, near Dresden. Heitmch Tessenow, 1925. View of central garoe~1. 5 Student housing at Chieti. Giorgio Grassi and A ntonw M onestiroli, 1980. Aerial view of truxkl.

-

always been to prove its own necessity, as is evident in works which are firmly planted in the ground: that is, it places most importan.ce on the total, characteristic stat-icnus of architecture. Technical solutions, even the most future-oriented, mtlllt always conform to this condition, which is one of architectwe's most basic principles.

To speak of evocation in the particular world of architec-tural 1-epresentation is to speak of f

-

398 Lie. Besides, architecture is a "public matter" par excel-lence.

In fact, architecture must first of all come to terms with itself, that is, with its specific characteristics; but at the same time it must also come to terms with its partkular social responsibility. And in this light the question of its rapport with the public becomes impossible to ignore,. For t his reason the language of architecture is-r should be-an accessible language! Moreover, since architecture en-ters directly into everyday life (for example, through its extra-artistic functionality), it creates a permanent bond that provides a firm critical base from which to pass j udg-ment upon many "good intentions."

But this bond also has an.other aspect, less evident but just as important, which relates to architecture's partic-ular evocative purpose. It is the bond between indh

-

402

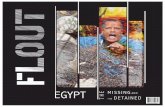

1 (frontispiece) M arclifield (Marzfeld), R eichsparleilagsgelande, Nuremberg. Albert Speer, 1940, destroyed in 1950. 2 Danish Entbassy, Berlin-Tiergarten. J. E . Schaudt, 1999-1940. Sclutduledfor demolition in 1980-1981 to make way for an extension to tlut zoo.

Now that construction and the fever for innovation have calmed down a little, now that the.re are no handy excuses for further destruction, the time for reflection is at hand .... It finds us, however, very ill-equipped, for in truth, the phoenix of modern architecture did not rise from the ashes of the war; it was on the contrary born in the immense suffe.ring of an obligatory postwar oblivion-an oblivion of the past, of architecture, and of a non-industrial civilization tout COllrl.

Consequently in Germany one associates traditional and classical architecture with Nazi tyranny and extermina-tions. For architects the erection of a classical col.umn causes more pain than the construction of a nuclear re-actor. They are more afraid of a splendid classical colon-nade thl!n of a line-up of Krupp PaJJUn;,

I will therefore try to explain the destruction of so many classical and traditional stuctures by denouncing the elimination of its most critical and contested examples, i.e., the most prestigious buildings of Nazi architecture.

In a bitter discussion of the German Werkbund in Drum-stadt in 1978, the Austrian architect Hans Hollein said. "Fortunately Hitler didn't have too pronounced a taste for Wienerschnitzel; othenvise they too would be forbidden in Germany today." In a similar manner Albert Speer explained to me that things would be going far bettea for classical architecture today if Hitler had been a fanatic for modern art.

After 1945, the Allied victors did not hesitate to take as spoils of war aU the enemy's technical and industrial ge-nius. The Reich's industrialists, technicians, and engi-neers were received with open arms in America, in France, and in Russia alike. They were able to work in the comfort of the most reputable institutions and ffi.rms in order to bring to fruition their most sinister research. The author of the redoubtable V -2 was to develop the Saturn missiles; he and his comrades of the swastika were to be granted the highest marks of distinction by t heir new patrons.

l! Let us not forget that the Morgenthau Plan. commis-sioned by t he Roosevelt and Truman administrations, had proposed to transform the tenitory of the former Reich into a purely agricultural landscape with medieval cus-toms. One ignores, however. that the central objective of this project was the maximum industrialization of t he Ruhr and Saar land , to be exploited by multinational trusts. The proletarians of t hese intemational industrial zones would probably have had very little to be envied by the slave.s of the SS industr-ial empire.

The amusing remarks of Hollein and Speer cannot make us forget, however, that the oblivion of the German past, however radical, has also been very selective-and very calculating. But let us imagine for a moment that things h;1d gone differently . ..

A Politico-Cultur-al Fable Let us imagine that the repression of Nazism has just led to the destruction of its most grandiose and typical eal-izations. Thus, for example, Albert Speer has spent the last months of his ministry undertaking the total destmc-tion of the industrial installations of the Reich. Let us also suppose that under the Morgenthau Plan the Saar and the Ruhr have been in fact transformed into agricultural and cattle-breeding areas.

Thus in 1946 we see legions of workers all across the old Reich te.aring up the highways, dynamiting the band new interchanges, re-planting fields and forests over the re-mains of the gigantic industrial in,;tallations. The t-oncen-tration camps ar-e transformed into commemorative mon-uments, but in the same fever of atonement the "Heimann Goering" (Salzgitter) steelworks and Volkswagen facto-ries ru-e destroyed. Where for years t he diabolical war machine had been foged, now vineyards grow.

To the amazement of the free world. not only are the emblems and banners of the Reich thrown on t.he scrap-heap, but also the thousands of gray 'beetles' with which the FUhrer had hoped to mobilize and subjugate t he Ger-man people and all of Europe ...

Copyrighted material

-

3 For the reconstTuction of Gl':l.,wn cities, r:raft production tootdd have been completely eliminated followi,lg Hitler's Housing Edict ~f 19H. The Bauordnungslebre, a huge book published by Ermt Neufert 1111der the awtpices of Albert Speer in 1943, demonstrates that by 1950 at the Latest Nazi arcltilture toould lw.ve

~ fi'\ J- ...a ......... s.cw.a - ..,_..... _....... ~ ... - -.prridooa ........ - ~ ........... -

,...__,~ .. -~ ... lc.ll.h.a--"-

adopted not only the town-planning p1inciples of C I AM, but the buildings would have looked lik.e t>refab buildings as tJtmJ looked all over the toorld! 4 Boulet'O.rd Lampposts on the east west cu;is of Berlin. A lbert Speer, 1939.

~---...k.-ckf.W.C.P,a--t ... V......... Die ..... VOifAiwo ....._lit:h 1::8,.. G.cW.

405

4

3 Cooynqhted mat nul

-

406

6

mayor of Munich decided to dynamite t he Haus der Deutschen Kunst (fig. 5). This prestigious building, which had survived all the bombini,'S in one piece, was saved in

e:~;tremi8 by the American military commander. Speer's masterpiece, the Chancellery (figs. 7, 8), on the other hand, served the Russians as a quarry for the construction of the gigantic monument to the dead of Treptow (fig. 9), a small price to pay for so many victims and sacrifices. But in 1967, it was no longer t he conquerors who dyna-mited Speer's long and elegant colonnade in Nuremberg (figs. 10, 11). Did Berlin really hope to enrich itself by dynamiting, in the totally ruined Tiergarten quarter. the only grand building of Speer's circus (Runder Platz) in order to erect Mies van der Robe's National Gallery (figs. 12-14)? So many examples from history were available as examples of wisdom, devoid of all this confusion which forces us today to pile massacre upon massacre. For in-stance, we know that the t1iumphal arch of Chalgrin. erected to the memory of Napoleon's victories, was only completed after the death of both, under a restored mon-archy.

Similarly the Christian churches, upon papal bull, were erected in the Roman baths and basilicas. not least in order to ensm-e the transition from one culture to another, rather than making a vict01's ultimate challenge to already prostrate beliefs.

But here the impotence and .vacuousness, Lhe lack of cul-tural and human content. and the deep insecurity of this modernism, which was always and everywhere to conquer through destruction, was not even able to reuse the most prestigious buildings of the vanquished and saw fit to bury the llfilitary Academy, one of the few architectural com-plexes to be completed dming the Third Reich, under the gigantic mound of debris that is the Teufelsberg in the Grunewald of Berlin.

Society Assassinawl While citizens everywhere are calling modern urbanism and architecture into question, the "architects" continue to argue over its deceptive appearance. For the fallacious and labile masquerade of the styles-first Neoclassical,

Copy gll,ed matenal

-

408

10 10 Speer's own ltcuse in Zelllendoif was ironically /til; only builcling destroyed by bombi;,g. 11 Colonnade al Zeppelinfeld. Albert Speer, 1935-1937, destroyed in 1967. 12 Model of Albert Speer's plan for the Runder Platz, Berlin, showing the Pemdenvekehrshans.

11 Copyng ' d m