Grainfields on the Sabbath

-

Upload

justin-langley -

Category

Documents

-

view

222 -

download

0

Transcript of Grainfields on the Sabbath

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

1/26

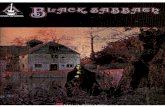

WHEATON COLLEGE GRADUATE SCHOOL

A SABBATH STROLL THROUGH THE GRAINFIELDS WITH THE PHARISEES:

AN EXEGETICAL EXPLORATION OF JESUS CONFLICT WITH THE PHARISEESCONCERNING SABBATH REGULATIONS AS RECORDED IN MARK 2:23-28

SUBMITTED TO DR. DOUGLAS J. MOOIN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF

BITH 645-CANONICAL BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION

BYJUSTIN LANGLEY

APRIL 21, 2011

CPO 4224

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

2/26

1

INTRODUCTION

From the beginning, breaking the Sabbath regulations instituted within the stipulations of the

Mosaic Covenant between Yahweh and the nation of Israel constituted a capital offense.1

The

people of Israel understood that the instruction to keep the Sabbath meant to avoid all work on

the seventh day of each week. However, concerning what precise activities Yahweh regarded as

work they never received specific revelation. Therefore, especially after the Exile, it seems that

keeping the Sabbath by not working on this day escalates in importance, perhaps due to the

preaching of the prophets, which included both Yahwehs specific judgment for not keeping the

Sabbath and Yahwehs promises of restoration in connection with the peoples renewed keeping

of the Sabbath.2

With this recognition in mind, it seems relatively naturaleven if ultimately

misguided by a faulty foundation for the fundamental purpose of the Sabbath regulationsthat

Jewish interpreters of the Mosaic Law would attempt to ensure that the people of Israel would

come nowhere near breaking the Sabbath. Indeed, expectations surrounding the nations

successful keeping of the Sabbath in connection with the coming of the Messiah eventually

escalated to such a degree that at least one rabbi believed that if the whole nation could keep two

consecutive Sabbaths perfectly, then the Messiah would come.3

1 See, e.g., Exod 31:12-17 and Num 15:32-36.

2See especially Jer 17:19-27.

3b. Shab. 118b. Cf. Ronald J. Kernaghan,Mark(IVPNTC; Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity, 2007), 65.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

3/26

2

The Jewish leaders of the first century probably cultivated this exalted view of the

Sabbath, so that, when Jesus steps into public view and begins making lofty claims about himself

while at the same time acting in ways that basically disregarded the precautions that their

predecessors had established and that they intended to maintain and develop in order to protect

people from breaking the Sabbath, they aggressively oppose him.4Marks Gospel highlights

their opposition by narrating in chs. 2 and 3 a series of controversies in which the scribes and/or

Pharisees challenge Jesus proclaimed and enacted authority. Their challenges seem to intensify

as the narrative progresses: in 2:6-7, the scribes question in their hearts whether Jesus has

blasphemed by claiming to forgive a mans sins; in 2:16, the Pharisees question his disciples

concerning his interactions with sinners and tax collectors; in 2:24, they question him directly

about his disciples behavior on the Sabbath; in 3:2, they watch him carefully, hoping to find

grounds to formally accuse him of breaking the Sabbath; in 3:6, the Pharisees conspire with the

Herodians to determine a way to destroy him; and in 3:22, some scribes publicly attempt to

discredit his authority by accusing him of collusion with the dev il. Arguably, Jesus actions on

the Sabbath day, along with his justification for those actions, served as the final straw that

provoked the Pharisees to judge him as one whom they must silence at whatever cost.

Marks Gospel opens with an indication thathe has set out to record the beginning of the

gospel of Jesus Christ, Gods Son (1:1),5which he connects very closely with Isaiahs prophecy

concerning the way of the Lord, (1:2) prepared for by a voice crying out in the wilderness,

(1:3) which Mark identifies as John the Baptist preaching a baptism of repentance for the

4For a summary of Jesus Sabbath controversies with the Pharisees in the Synoptic Gospels, see Peter

Tomson, If This Be From Heaven: Jesus andthe New Testament Authors in Their Relationship to Judaism(Sheffield: Sheffield, 2001), 152-6.

5All Scripture quotations are my own translations into English.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

4/26

3

forgiveness of sins (1:4).6The narrative then moves quickly through Jesus baptism and

temptation and then introduces and summarizes his public preaching, indicating that he preached,

saying, The time has been fulfilled and the kingdom of God has come near; repent and believe

the gospel (1:15). Then, Mark records a series of events that display Jesus authority in various

ways. He summons disciples and they abandon everything and follow him (1:16-20); he

commands demons to hush and to leave individuals and they obey him (1:21-27); he touches

Simons mother-in-law and a fever leaves her (1:29-31); he exercises authority over all kinds of

sicknesses by healing many people (1:32-34); he makes a leper clean (1:40-45); he forgives a

mans sins and then heals him of his paralysis (2:1-12); and he identifies himself as a physician

who calls sinners to himself (2:13-17). As Mark unfolds these events, he has perhaps set 2:23-28

to stand as the climax of this series of Jesus displays of authority, as Jesus even claims to have

ultimate authority over the Sabbath, which surely goes beyond the self-understanding of the

Pharisees, who believed they had the right to impose on people regulations to ensure that no one

transgressed the prohibition of working on the Sabbath day.

A SABBATH STROLL THROUGH THE GRAINFIELDS (2:23)

Mark sets the pericope up for his readers in a way that mimics the start of narrative pericopes in

the Hebrew Bible. reflects the ubiquitous transitional phrase , which precedes a

more specific time marker.7 The time marker in this case, , also presents certain

6Recognizing that Mark has conflated at least two passages from the LXX (Exod 23:20; Isa 40:3; possibly,

though in my view unlikely, Mal 3:1), his specific mention of Isaiah probably indicates that he intends his readers to

view the quotations and the referents involved primarily in light of Isa 40. Cf. Joel Marcus, The Way of the Lord:

Christological Exegesis of the Old Testament in the Gospel of Mark(New York: T&T Clark, 2004), 17-21.

7Cf. Robert A. Guelich,Mark 1-8:26(WBC 34A; Dallas: Word, 1989), 29, 119.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

5/26

4

difficulties. First, Mark does not indicate any more specifically the temporal relationship

between this Sabbath day and the previous Sabbath day mentioned in 1:21. Second, why does he

use the plural form? Swete points out some of the regular occurrences in the LXX of the

formally plural clearly referring to a single Sabbath day, and indeed this phenomenon

occurs fairly regularly in the other Gospels as well.8

On this particular Sabbath day, Mark informs his readers that Jesus went for a stroll

through the grainfields with his disciples, and then Mark brings into focus the disciples

behavior: they had begun to make a path as they plucked the heads of grain. The oddity of the

phrase , though surely original, provoked many scribes to suggest various

changes. Perhaps to harmonize with this account in Matthews Gospel, some manuscripts simply

omit the strange , and change the participle to an infinitive. Others replace

with either , which does not occur elsewhere in the NT (or in the LXX), or

, which occurs only in Acts 10:9 (in a different form), but would make good sense

in this verse, since it conveys the idea of traveling.9

The scribes responsible for these changes seem to have understood that Marks

description only intends to convey traveling,10 but with the particular combination of and

in such an ostensibly awkward way, perhaps Mark has chosen this construction

intentionally. This phrase in non-biblical usage may technically convey the paving of a road,11

8H. B. Swete, The Gospel According to Saint Mark(New York: MacMillan, 1898), 17. Cf. Robert G.

Bratcher and Eugene A. Nida,A Handbook on the Gospel of Mark(UBS Handbook Series; New York: United Bible

Societies, 1993), 44. See also, e.g., Matt 12:11, 12; 28:1; Luke 4:16; 13:10.9See BDAG, , 690.

10Matthew C. Williams, Two Gospels From One: A Comprehensive Text-Critical Analysis of the Synoptic

Gospels (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2006), 77. The phrase does appear in Judg 17:8 (LXX) to convey the simple

concept of traveling. See also James Hope Moulton and Nigel Turner,A Grammar of New Testament Greek, Volume

4: Style (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1976), 29, who suggest a possible Latin influence on this phrase, so that it would

also convey the basic concept of traveling.

11Cf. M-M, , 438.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

6/26

5

but it remains difficult to understand Mark describing the disciples actions of going through

grainfields with this idiom.12 However, these two terms also occur together in Marks opening

quotation of Isa 40:3 (LXX), though not directly connected. They do appear together as a verb-

object pair in Isa 43:19 (LXX), with Yahweh stating, Behold, I am making new things which

will now rise up, and you will know them, and I will make a way in the wilderness and rivers in

the waterless place. Derrett has insisted on maintaining that Mark intends to convey the image

of paving a road with the phrase in 2:23, and he connects this with the right of a king

to drive a path through a persons field of standing grain when he marches out on a royal

expedition.

13

Many commentators mention Derretts argument only to dismiss it quickly,

14

but

perhaps he has noticed something that resonates with Marks intention to draw on the imagery of

Isa 43, for in Isa 43:15 (LXX), just a few verses prior to the occurrence of ,

Yahweh refers to himself as Israels king. Perhaps using this phraseology allows Mark to

accurately convey the disciples actions as simply traveling through the grainfields, while subtly

communicating to his audience a pointer to the royal status of Jesus. The participle

simply indicates the action of the disciples that accompanied their traveling through the

grainfields, namely plucking free the edible portions of the heads of grain.15

12So also Williams, Two Gospels, 77 n. 36. Cf. Swete,Mark, 47.

13J. Duncan M. Derrett, Studies in the New Testament: Volume 1 (Leiden: Brill, 1977), 94. The Mishnah

records the acceptance of this royal right within Judaism in m. Sanh. 2:4. See also Joel Marcus,Mark 1-8 (AYB 27;

Garden City: Doubleday, 1999; repr. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2008), 239.

14See, e.g., R. T. France, The Gospel of Mark(NIGTC; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), 144 n. 49.

15See C. Spicq, , TLNT3:379.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

7/26

6

THE PHARISEES CRY FOUL: THE DISCIPLES UNLAWFUL BEHAVIOR (2:24)

Mark abruptly introduces the Pharisees onto the scene, even without his customary usage of

. He has not informed his readers how they came to encounter Jesus and his disciples at this

grainfield; instead, he focuses attention on their accusation concerning Jesus disciples behavior:

Look! Why are they doing on the Sabbath what is not lawful? Mark does not explicitly clue his

readers in on what specific behavior they found objectionable, but clearly it has to do with an

activity they perceive as unlawful on the Sabbath day, namely, the plucking of the heads of

grain, an action which the Pharisees probably considered as falling under the category of

reaping, which, by this time, they would have surely considered as prohibited work on the

Sabbath day, though this specific prohibition does not appear in the OT. 16 This may also

illuminate Marks awkward wording in 2:23 describing the disciples actions; by utilizing the

participial form of and subordinating it to , perhaps Mark subtly implies

the innocence of the disciples by focusing attention on their travel rather than their plucking.17

The Pharisees concern to challenge Jesus on this issue probably reflects the heightened

significance placed on Sabbath observance during this time.18 The term occurs in Marks

Gospel six times and has to do with whether or not a particular action falls within ones legal

rights, usually, but not always, with reference to the Mosaic Law.19 In light of the fact that a

16The prohibition of gleaning on the Sabbath day might be implied by Exod 34:21; on any other day, the

activity of the disciples is specifically permitted in Deut 23:25. For a list of the 39 categories of work, which surely

developed over a period of time that included Jesus day, see Emil Schrer,A History of the Jewish People in theTime of Jesus Christ, Second Division, Vol. II(Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1890), 96-105.

17So also Adela Yarbro Collins,Mark(Hermeneia; Minneapolis: Fortress, 2007), 201-2. Cf. Marcus,

Mark, 239.

18See comments in the Introduction. Cf. Eduard Lohse, , , , TDNT7:8.

19H. Balz, ,EDNT2:5. Cf. Douglas J. Moo, Jesus and the Authority of the Mosaic Law, JSNT

20 (1984): 3-49; repr. in The Historical Jesus: A Sheffield Reader(ed. Craig A. Evans and Stanley E. Porter;

Sheffield: Sheffield, 1995), 95 n. 58. Contra Paul L. Danove,Linguistics and Exegesis in the Gospel of Mark:

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

8/26

7

specific prohibition of the disciples action does not clearly exist within the OT, it seems that the

Pharisees considered their expansive definition of what constituted work prohibited on the

Sabbath day as rooted in OT law in such a way that it must also carry divine authority.20

Their

confrontation of Jesus and his disciples here may also reflect their suspicion of these rustic

Galileans, assuming their pathetic ignorance of the subtleties of the implications of the Sabbath

laws.21

JESUS STRIKES BACK: I AND MINE GREATER THAN DAVID AND HIS (2:25-26)

Jesus responds to their challenge by appealing to events recorded in Scripture in 1 Sam 21-22,

focusing on 1 Sam 21:2-7. He responds to their question about what his disciples were doing

with a question about their Scripture-reading habits: Have you never read what David did?

Mark records Jesus responding to questions from opponents three times with a question

concerning a particular passage of Scripture (2:25; 12:10, 26). On this occasion, Jesus does not

actually quote the text, but rather refers explicitly to the events described by the text. Both Jesus

opponents and Marks readers would surely have known the story well, so we should examine

the text of 1 Sam 21:2-7 in order to understand how Jesus appeals to the events described there in

order to defend his disciples actions.

Applications of a Case Frame Analysis (JSNTSS 218; SNTG 10; Sheffield: Sheffield, 2001), 124, whether we may

further imply the agency of God when this term occurs is less clear, although we may admit that the Pharisees would

have assumed that to be the case.

20See the interesting discussion in James G. Crossley, The Date of Marks Gospel: Insight from the Law in

Earliest Christianity (JSNT 266; New York: T&T Clark, 2004), 161-2.

21R. Alan Cole,Mark(TNTC 2; Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity, 1989), 129.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

9/26

8

1 Samuel 21:2-7

The books of Samuel serve to narrate the establishment of the kingship in Israel, ultimately in the

person of David. The people choose Saul as their king, but he finally rejects Yahwehs

leadership, and Yahweh chooses and sends Samuel to anoint David as the rightful king over

Israel. Davids selection and initial anointing happen while Saul still sits on the throne (1 Sam

16), so Saul spends the rest of his life chasing after David in murderous rage. Davi ds close

friendship with Sauls son Jonathan only infuriates the derelict king further, but Jonathan enables

David to flee to safety, when the king chooses to make his opposition to David public and begins

a campaign to strike him down (1 Sam 20).

Thus, David flees from King Saul, and he heads toward Nob22 to the sanctuary there,23

where Ahimelech and his family served as priests. When Ahimelech meets up with David, he

trembles in fear and asks David why he has come alone. The narrative does not provide readers

with details about how much Ahimelech knows about Davids relationship with Saul, but we

may surely conclude that he would have perceived the oddity of someone with Davids status

and reputation traveling alone.24 David responds to Ahimelech with a fairly elaborate deception

in order to assuage Ahimelechs fears and ingratiate him to agree to Davids request; 25 he

indicates that King Saul26

has entrusted him with a matter.27He quotes the king as

22The at the end of seems clearly to be the directional marker, though it is pointed unusually. Cf.

Joon 93c.23

The OT does not narrate how the sanctuary arrived at Nob, but rabbinic tradition lists the various

locations of Gods encampments. See Pesiq. Rab Kah., Piska 17, Sec. 1.

24Joyce G. Baldwin, 1 and 2 Samuel (TOTC 8; Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity, 1988), 147.

25So Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Narrative (New York: Basic Books, 1981), 71.

26Some interpreters have attempted to conclude that David was not lying here; rather, he was being clever

by not specifying the name of the king who had sent him on this secret mission. In doing so, he was actually

referring to Yahweh, but he knew that Ahimelech would have understood him to be referring to Saul. For this line of

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

10/26

9

instructing him to tell no one any details of his mission. He adds that he has sent his young men

ahead to a place where he will meet them as a way of explaining why he has come alone. The

verb in the MT, , may reflect an unexpected root related to the Arabic wda,28 or

4QSamb

may preserve the correct reading, , which seems to reflect the LXX

.29 Either way, David indicates to Ahimelech that he has some young men

waiting for him somewhere.30

In 21:4, David makes his request of the priest of Nob: he needs provisions for his

journey. We could characterize Davids verbiage here as stilted, rushed, perhaps reflecting the

urgency of his situation.31

He blurts out three idiomatic expressions: What do you have

available? Five loaves of bread? Please give me whatever you can find!32 Ahimelech responds

to Davids request for bread by indicating that he only has holy bread, set aside especially and

exclusively for priests. The rendering of Ahimelechs response vividly portrays his thought

process: There is no common bread available, but there is the holy breadif the young men

have been surely kept from women. Readers can almost visualize Ahimelechs thoughts shifting

argumentation, see Robert D. Bergen, 1, 2 Samuel (NAC 7; Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2001), 221. Cf. alsoRikk E. Watts, Mark, in Commentary on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament(ed. G.K. Beale and D.A.

Carson; Grand Rapids: Baker, 2007), 140. While the author of Samuel does use occasionally to refer toYahweh (see 1 Sam 8:7; 12:12), it seems too subtle in this context for any readers to make this connection.

Moreover, assuming that refers here to Yahweh does not seem to alleviate the difficulties in this passage.27

A.B. Davidson,Hebrew Syntax (3d ed.; T&T Clark, 1902), 109.

28So David Tsumura, The First Book of Samuel (NICOT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007), 529-30.

29So P. Kyle McCarter, Jr.,I Samuel (AYB 8; Garden City: Doubleday, 1980; repr. New Haven, Conn.:

Yale University Press, 2008), 347.

30The Hebrew phrase surely indicates an anonymous place, whereby the narrator is

reflecting Davids secrecy here. Interestingly, the LXX here appears to have transliterated this phrase and consideredit an actual place name.

31So Alter,Art, 71.

32Cf. Roger L. Omanson and John Ellington,A Handbook on the First Book of Samuel (UBS Handbook

Series; New York: United Bible Societies, 2001), 456.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

11/26

10

from, Sorry, I cannot help you, to, Well, this is most irregular, and finally to, There might

be a way I can help you. Both the priests question and Davids emphatic affirmative response

involve the collective usage of the singular .33Ahimelech takes Davids request to envision

taking care of his young men, whom he has alleged he will soon join, and Ahimelech wants to

make sure that those who would eat the holy bread have remained ceremonially pure, so that

they may eat breadreserved for Levitesin a Levite-like way.34 David assures the priest that

his young men always abstain from sexual encounters when they go out on an expedition with

him in order to maintain their purity, and because of the special nature of this mission, he has

considered it even more important that they do this. Thus, Ahimelech agrees to give the bread to

David for his young men, ostensibly to provide for their need.35

The narrator summarizes this event in 21:7 and specifies why Ahimelech hesitated to

give this holy bread to David. Ahimelech gives him the bread of the Presence,36 which,

according to Lev 24:5-9, consists of twelve loaves of bread that the priest must arrange and set

before Yahweh every Sabbath day. The loaves then sit out before Yahweh all week long, and the

priest removes the loaves from the table every Sabbath day. Once the bread of the Presence

enters the sanctuary, its nearness to Yahweh renders it holy. After the high priest removes the

loaves from the sanctuary, therefore, he must properly dispose of the holy bread.37 Lev 24:9

33See GKC 123.b.

34

Bergen, 1, 2 Samuel, 222.35

Although David does not vouch for his own purity, Ahimelech probably assumed it. This is indeed ironic

as David spins this elaborate lie while maintaining a claim to purity. See Victor P. Hamilton,Handbook on the

Historical Books (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2004), 271.

36Surely van Iersel is confused to assert that this bread was not the twelve loaves of the Presence. See Bas

M.F. van Iersel,Mark: A Reader-Response Commentary (trans. W. H. Bisscheroux; JSNT 164; New York: T&T

Clark, 2004), 158 n. 63.

37Paul V. M. Flesher, Bread of the Presence,AYBD 1:780.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

12/26

11

specifies that the priests must eat the loaves in a holy place.38

Thus, the Mosaic Law stipulated

that only priests could eat this particular bread, but Ahimelech chooses to give it to David for the

benefit of himself and his young men.39

Therefore, this narrative portrays an ostensibly

acceptable technical violation of a legal command in order to satisfy human need.40

After David deceptively receives provisions, including Goliaths sword (21:9-10), he

flees to the Philistine territory of Gath, feigns insanity, hides in the cave of Adullam, travels to

Moab, and settles for a time in the forest of Hereth (21:11-22:5). The narrative does not indicate

that David actually had any young men waiting for him at all, unless we should understand his

brothers and his fathers whole house as constituting his young men.

41

Furthermore, the narrator

never informs readers whether anyone actually ate the bread, though we may fairly infer that

David ate the bread as he journeyed.42

In 21:8, we also learn of a witness to these events, a servant of Saul, Doeg the Edomite.

Saul had begun to seek David openly when Doeg informs him of Ahimelechs encounter with

David. Saul confronts Ahimelech, who answers him honestly, not expecting that his behavior

should provoke a negative response from the king,43 and then Saul has Doeg slaughter all 85 of

38This has led many commentators, following some rabbis, to conclude that the events of 1 Sam 21

occurred on a Sabbath day, since that is when the loaves are changed out. Two things seem to stand against this

conclusion, however. First, the narrator is merely explaining what bread has been under discussion; the last half of v.

7 simply describes the bread of the Presence as that which is removed from before Yahweh to set hot bread on theday when it is to be taken away. The narrator does not clearly state that this had just happened. Second, the Lawnowhere indicates that the twelve loaves had to be eaten on the Sabbath day. So, perhaps it is more likely that David

has arrived at Nob in the middle of the week and he is requesting whatever bread may be left over, understanding

that the priests eat the twelve loaves over the course of the week.

39 Contra Eugene H. Merrill,Everlasting Dominion: A Theology of the Old Testament(Nashville:

Broadman & Holman, 2006), 447, this passage should not be read to imply Davids priestly prerogatives.

40 Frank Thielman, The Law and the New Testament: The Question of Continuity (New York: Herder &

Herder, 1999), 64.

41 Cf. Kernaghan,Mark, 66.

42Marcus,Mark 1-8, 240.

43McCarter, 1 Samuel, 350.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

13/26

12

the priests at Nob as well as all the people of the city of Nob. However, one man escapes:

Abiathar, one of Ahimelechs sons. He flees to David and informs him of what Saul had done

and becomes the high priest who serves throughout the rest of Davids rise to power (22:6-23).

Jesus Appeal to the Events Narrated in 1 Sam 21:2-7

Jesus begins commenting on what David did by indicating that David had a need and was

hungry, he and those with him (Mark 2:25). With this comment, Jesus takes on the perspective

of Ahimelech the priest, who perceived and responded to the need, though neither David nor the

narrator characterizes the situation in just those terms, and who also believed Davids lie that he

sought provisions for his men. Thus, Jesus connects the actions of himself and his disciples with

the apparent actions of David and his men by implying that he and his disciples had a need and

were hungry.44 Jesus then highlights certain details of the story to elucidate further the point he

desires to make (2:26). He asserts that David entered the house of God, an oblique reference

that could refer to any sanctuary, which would include the sanctuary at Nob. The narrative of 1

Sam 21 certainly does not explicitly state that David entered the sanctuary, but it may imply that

he stepped inside the outer region of the place; when he asked for a sword from Ahimelech, the

priest responded by pointing out Goliaths sword, wrapped in a cloth and resting behind the

ephod, which may imply that David could see it.

Next, Jesus comments that this took place in the time of Abiathar the high priest.

According to the text of 1 Sam 21, David received the bread and the sword from Ahimelech the

44Cf. Francis Watson, Text, Church, and World: Biblical Interpretation in Theological Perspective(New

York: T&T Clark, 2004), 275.Cf. Matt 12:1. Moulton and Turner, Grammar, 19, suggest that this is an example of

Markan redundancy. However, it may be better to understand this as an example of hendiadys, as does Richard A.

Young,Intermediate New Testament Greek: A Linguistic and Exegetical Approach (Nashville: Broadman &

Holman, 1994), 243.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

14/26

13

priest. Scholars have debated the significance of Jesus reference to Abiathar throughout church

history,45with many opting to accept a factual error in Marks Gospel.46 It seems best, however,

to ascribe rhetorical intentionality to Jesus in mentioning Abiathar specifically. Surely, the

phrase does mean in the time of Abiathar the high priest.47 Perhaps

Jesus refers to the time frame of Davids actions in this way in order to bring to the Pharisees

minds the fact that Abiathar became the priest as a result of Davids encounter with Ahimelech

(1 Sam 22:20; 23:6). More specifically, perhaps Jesus intends the Pharisees to realize that their

opposition to him resembles Sauls opposition to David.48

Then, Jesus indicates that David ate the bread of the Presence, which the narrative of 1

Samuel implies sufficiently enough. He next highlights the point of contact between his conflict

with the Pharisees and the situation of David by means of the relative clause, which probably

conveys the concessive idea, although it is not lawful [for anyone] except the priests to eat.49

The usage of here links with the specific accusation from the Pharisees. Again, Jesus

identifies a point that the narrator of 1 Samuel does not explicitly state, probably picking up on

45Perhaps one of the earliest recorded attempts to explain away this apparent mistake, St. John Chrysostom

(347-407) suggested that Ahimelech also went by the name of Abiathar, though he cites no evidence. St. John

Chrysostom,Homilies on Matthew XXXIX (NPNF1:10), 255-6. For an account of the usual range of options for

understanding this detail, see William L. Lane, The Gospel of Mark(NICNT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1974), 115-

16. And, for the textual history, with the variants resulting largely from scribes probably attempting to correct the

perceived mistake, see Williams, Two Gospels, 78-9.

46By his own account, study of this text drove Bart D. Ehrman to abandon his Christian faith. See Bart D.

Ehrman,Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why (New York: HarperCollins, 2005),

8-10. Cf. Peter Williamson, Catholic Principles for Interpreting Scripture: A Study of the Pontifical Biblical

Commissions The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church (subsidia biblica 22; Roma: Pontificio Istituto Biblico,

2001), 37.

47 A. T. Robertson,A Grammar of the Greek New Testament in the Light of Historical Research (Nashville:

Broadman & Holman, 1947), 603.

48Cf. James M. Hamilton, Jr., The Typology of Davids Rise to Power: Messianic Patterns in the Book of

Samuel (a Julius Brown Gay Lecture presented at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary on March 13, 2008;downloaded 18 April 2011; online: http://jimhamilton.wordpress.com/2008/03/14/the-typology-of-davids-rise-to-

power-messianic-patterns-in-the-book-of-samuel/), 18-19. Cf. Watts, Mark, 141. See also N. T. Wright,Jesus andthe Victory of God(Christian Origins and the Question of God 2; Minneapolis: Fortress, 1996), 393-4.

49So Young,Intermediate, 232.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

15/26

14

the significance ofthe narrators comment in 1 Sam 21:7. Finally, he concludes his re-telling of

the events by closing the circle of connections that his situation with his disciples shares with

Davids situation by adding, and he even gave [some] to those who were with him. Thus, he

repeats the reference to men with David, even though the original narrative clearly does not

envision anyone else actually with him.50

Again, this probably reflects Jesus decision to take the

perspective of Ahimelech, who chooses to give the bread to David on the assumption that he did

have men waiting for him who needed provisions.

The Significance of Jesus Initial Reply

Although some modern commentators see in Jesus reference to the events recorded in 1 Sam 21

an attempt to draw a precedent specifically for breaking the Sabbath, the connections Jesus

explicitly makes between his situation and the situation of David in 1 Sam 21 lie elsewhere. He

highlights the need in both situations, the unlawful nature of the actions of both situations, the

connection between David and his men on the one hand and between himself and his disciples on

the other, and ultimately the apparent acceptability of both unlawful actions. For several reasons,

as many scholars have pointed out, the Pharisees likely would not have accepted Jesus appeal to

this event as a valid argument against their accusation.51

Indeed, Jesus himself probably put forth this appeal as only a first step in a cumulative

argument, so that each of the following responses escalate his defense of the disciples

50Cf. Craig S. Keener, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: New Testament(Downers Grove, Ill.:

InterVarsity, 1993), s.v. Mark 2:25.

51See especially Rabbi D. M. Cohn-Sherbok, An Analysis of Jesus Arguments Concerning the Plucking

of Grain on the Sabbath,JSNT2 (1979): 31-41; repr. in The Historical Jesus: A Sheffield Reader(ed. Craig A.Evans and Stanley E. Porter; Sheffield: Sheffield, 1995), 132-5. Cf. Guelich,Mark 1-8, 122-3.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

16/26

15

behavior.52

Nevertheless, the point carries certain significant points. First, he seeks to adduce a

biblical example of a clearly unlawful action that receives no censure because the action served

to meet human need, for if the Pharisees accept that David broke a biblical law then they should

find acceptable the actions of Jesus disciples.53 Second, the story helps establish the rightful

relationship the disciples have with Jesus, as he takes responsibility for their actions in a similar

way to how Ahimelech recognizes Davids responsibility for his men.54 And this leads to the

third and climactic point of Jesus bringing up this story: Jesus connects himself typologically

with David,55

particularly with respect to Davids authority.56In Matthews account, the appeal

to the events of 1 Sam 21 precedes an argument focusing on the defilement of the sabbath by

the priests in pursuing their temple duties, on the grounds that , so

that perhaps the logic of the argument from David implies a parallel

.57 This provides a perfect transition into the next stage of his argument.

A REMINDER CONCERNING THE PURPOSE OF THE SABBATH (2:27)

Mark steps into the dialogue at this point with an introductory formula:

. This has stimulated much discussion in the commentaries, leading many scholars to

52This is noticed, among others, by St. John Chrysostom,Homilies, 256. Cf. Marcus,Mark 1-8, 245.

53Crossley,Date, 163. Thus, perhaps Jesus argument could be considered a kind ofqal vahomer

argument, on the basis of which he grants their accusation of his disciples, but, at the same time, attempts to

invalidate it because their accusation is only based on their own extension of biblical law rather than on the letter ofthe Law which David had transgressed in this situation. Cf. Watts, Mark, 140, and Watson, Text, 277.

54Cf. Rod Parrott, Conflict and Rhetoric in Mark 2:23-28, Semeia 64 (1993): 121. See also France,Mark,146.

55Cf. Hamilton, Typology, 26.

56Thielman,Law, 64-5. Cf. Moo, Jesus, 93.

57France,Mark, 146.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

17/26

16

conclude that Mark has added the saying introduced here from another setting.58

However,

Runges suggestion that Mark has stepped into the narrative at this point and inserted a

redundant mid-speech quotative frame in order to slow the pace of the discourse just before a

significant pronouncement makes much better sense.59So, in Jesus second line of

argumentation, he articulates his understanding of the fundamental purpose of the Sabbath: The

Sabbath came for the benefit of people, and not people for the benefit of the Sabbath.60 God had

provided the Sabbath for humanity to enjoy true rest and restoration, and now Jesus has come

to show his people how that must happen.61

The Pharisees always concerned themselves with

defining work so as to prevent people from breaking the Sabbath law, but Jesus has come to

define rest so as to show people how truly to keep the Sabbath.62

Nowhere in this passage does Jesus presume to disregard or abolish the Sabbath law; 63

rather, he seems here to claim that he knows the true purpose of the Sabbath and has the

authority to say when one is in a situation when the sabbaths purpose is better served and

honored by not obeying its Mosaic strictures.64 He reminds them of the philanthropic purpose of

the Sabbath, which they seem to have forgotten in light of the eschatological expectations that

had come to surround Sabbath-keeping. Calvin rightly noted that the Law ought to be

58E.g., Collins,Mark, 203.

59Steven E. Runge,A Discourse Grammar of the Greek New Testament: A Practical Introduction for

Teaching and Exegesis (Bellingham, Wash.: Logos Research Systems, Inc., 2010), 191.60

For with the accusative indicating benefaction, see Young,Intermediate, 92.

61 Ben Witherington III, The Gospel of Mark: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans,

2001), 131.

62 Cf. Thielman,Law, 65.

63Cf. Crossley,Date, 98.

64Ben Witherington III,Jesus the Sage: The Pilgrimage of Wisdom (Minneapolis: T&T Clark, 1994), 168.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

18/26

17

interpreted according to the design of the Legislator.65 Beyond this, as his argument comes to its

climax, he seems to imply that the kingdom of God would not come at some point in the distant

future when all Israel kept the Sabbath perfectly. Ironically, the reign of God was already

present, but the Pharisees did not see it.66 Unfortunately, due to their misunderstanding, the

Pharisees were changing the Sabbath into a cruel tyrant, and man into that tyrants slaveas if

Gods intention had indeed been to make man for the sabbath, instead of the sabbath for

man.67

SON OF MAN = SABBATH-LORD (2:28)

Commentators continue to debate exactly how 2:28 connects with 2:27. The precise significance

of the introductory remains difficult to characterize. The statement this conjunction

introduces brings Jesus argument to a breathtaking climax; the silence of Mark here as to the

Pharisees response only leaves the reader with the impression that Jesus has rendered them

utterly speechless by his final pronouncement. Indeed, we may summarize his response to the

Phariseesattack, borrowing Kernaghans language, as escalating from slightly less than

conciliatory, by subtly appealing to a biblical precedent from 1 Sam 21, to provocative, by

perhaps implying that their treatment of Gods anointed one and his followers serves as an

antitype of Sauls treatment of Gods anointed one, to incendiary, by implying both that they

65John Calvin, Commentary on a Harmony of the Evangelists Matthew, Mark, and Luke (transl. William

Pringle; Bellingham, Wash.: Logos Research Systems, Inc., 2010), 2:47.

66Kernaghan,Mark, 67.

67William Hendriksen,Exposition of the Gospel According to Mark(NTC; Grand Rapids: Baker, 1975),

108.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

19/26

18

have misunderstood the purpose of the Sabbath and that he stands over the Sabbath as its Lord.68

We might catch the rhetorical effect of this final statement, as Mark has fronted for some

measure of emphasis, by rendering the claim, And who is Lord of the Sabbath? The Son of Man

is!69

Though some commentators want to suggest that Mark might have inserted 2:28,70

only

Jesus uses the title the Son of Man, and he uses it consistently as a self-designation.71 Earlier,

in 2:10, he uses the title in claiming to have authority on earth to forgive sins, and it occurs 14

times throughout Marks Gospel.72 On the lips of Jesus, in the actual events Mark narrates, this

title carried a certain ambiguity, for people could use the phrase as a generic self-reference.

Indeed, it seems that throughout the Gospels, while Jesus alone uses the title for himself, no one

accuses him of making a particular claim based solely on this title. 73However, Marks readers

have the benefit of Jesus later specific connection of this title to its source, Dan 7:13-14, most

clearly in Mark 8:38; 13:26; and 14:62.74

Here, he unequivocally claims to have the authority

even to define what Sabbath means and how people ought to keep the Sabbath.75 Thus, he

repudiates the Pharisees (or anyone elses) authority to dictate limitations for how people may

68Surely, at a basic level only implies that he has the right to command or has control over the

Sabbath, and this may be all that the Pharisees perceived at the time. See Bratcher and Nida,Handbook, 102.

However, for Marks readers, must imply Jesus identification with Yahweh.

69James R. Edwards, The Gospel According to Mark(PNTC; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), 97.

Understanding the Son of Man as a self-reference, we might render it even more idiomatically as, And who isLord of the Sabbath? Oh yeahI AM!

70E.g., Robert M. Fowler, The Rhetoric of Direction and Indirection in the Gospel of Mark, Semeia 48

(1989): 121. Cf. Lane,Mark, 120.

71James A. Brooks,Mark(NAC 23; Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2001), 67.

72Frank Thielman, Theology of the New Testament: A Canonical and Synthetic Approach (Grand Rapids:

Zondervan, 2005), 70.

73Edwards,Mark, 79-80.

74Marcus,Mark 1-8, 531. Cf. Donald English, The Message of Mark: The Mystery of Faith (BST; Downers

Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity, 1992), 75.

75Cf. Thomas R. Schreiner,New Testament Theology: Magnifying God in Christ(Grand Rapids: Baker,

2008), 620.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

20/26

19

or may not behave on the Sabbath, even as he overrules their accusation against his disciples.76

So, within his response to the accusations of the Pharisees, he points to his identity as both

Davidic Messiah and Danielic Son of Man.77

Moreover, as David represented the men

(supposedly) with him, so also the Son of Man represents humanity; Jesus hearers may have

caught this connection, since a human being serves as a fundamental layer of meaning for the

phrase , as reflected in Ps 8:4. Thus, if he does intend to convey multiple

layers of meaning with this pregnant phrase, he may communicate here the idea that he stands as

a representative for humanity in his lordship over the Sabbath, vis--vis Heb 2.78

CONCLUSION

Jesus apparently experienced several intense encounters with the Pharisees concerning their

understanding of the Sabbath. Ultimately, he came and kept the Sabbath perfectly, as God

intended it, as a gift to humanity, so that his followers may experience the fullness of the

eschatological rest of God by trusting in him.79 When the Pharisees accused his disciples of

breaking the Sabbath because they had picked some heads of grain for themselves, Jesus

responds by appealing to a comparable situation in the life of David, which provides him the

opportunity to connect himself with David and his hearers with Saul in his murderous opposition

to David. He highlights the freedom of the priest Ahimelech to set aside the strict adherence to a

particular stipulation of the Law in order to enable David to provide for his mens needseven

76Gerhard F. Hasel, Sabbath,AYBD 5:855.

77Marcus,Mark 1-8, 246

78So Dan G. McCartney, Ecce Homo: The Coming of the Kingdom As the Restoration of Human

Viceregency, WTJ56:1 (Spring 1994): 11-12.

79Cf. A. G. Shead, Sabbath,NDBTn.p.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

21/26

20

though David has lied about his true needs. In this way, Jesus emphasizes the purpose of the

Sabbath, and indeed all law, as a gift to benefit people. Finally, Jesus reveals his own authority

over the Sabbath to determine what it means for people to experience its benefits by sanctifying

it. Indeed, the sabbath is not being sanctified if it means hardship for human beingsit is to be

a day of joy and rest, and if that means preparing a meal rather than feeling pangs of hunger, so

be it.80The Sabbath controversies in the Gospels highlight Jesus beneficent lordship, his

gracious sovereignty, as he brings to light the true purpose of the Sabbath.

80David A. deSilva,Honor, Patronage, Kinship & Purity: Unlocking New Testament Culture (Downers

Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity, 2000), 289-90.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

22/26

21

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alter, Robert. The Art of Biblical Narrative. New York: Basic Books, 1981.

Baldwin, Joyce G. 1 and 2 Samuel. Tyndale Old Testament Commentary 8. Downers Grove, Ill.:

InterVarsity, 1988.

Balz, H. . Pages 5-6 of vol. 2 ofExegetical Dictionary of the New Testament. Edited byRobert Horst Balz and Gerhard Schneider. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1990.

Bauer, Walter, William Arndt, F. W. Gingrich, and Frederick William Danker, eds. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature. Third ed.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

Bergen, Robert D. 1, 2 Samuel. New American Commentary 7. Nashville: Broadman & Holman,

2001.

Bratcher, Robert G. and Eugene A. Nida.A Handbook on the Gospel of Mark. UBS Handbook

Series. New York: United Bible Societies, 1993.

Braude, William G. and Israel J. Kapstein.Psita d-RaKahna: R. Kahanas Compilation of

Discourses for Sabbaths and Festal Days. 2d ed. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication

Society, 2002.

Brooks, James A.Mark. New American Commentary 23. Nashville: Broadman & Holman,

2001.

Calvin, John. Commentary on a Harmony of the Evangelists Matthew, Mark, and Luke.

Translated by William Pringle. 3 vols. Bellingham, Wash.: Logos Research Systems,

Inc., 2010.

Cohn-Sherbok, Rabbi D. M. An Analysis of Jesus Arguments Concerning the Plucking ofGrain on the Sabbath, Journal for the Study of the New Testament 2 (1979): 31-41.Repr. pages 131-9 in The Historical Jesus: A Sheffield Reader. Edited by Craig A. Evansand Stanley E. Porter. Sheffield: Sheffield, 1995.

Cole, R. Alan.Mark. Tyndale New Testament Commentary 2. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity,

1989.

Collins, Adela Yarbro.Mark.Hermeneia. Minneapolis: Fortress, 2007.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

23/26

22

Crossley, James G. The Date of Marks Gospel: Insight from the Law in Earliest Christianity.Journal for the Study of the New Testament 266. New York: T&T Clark, 2004.

Danove, Paul L.Linguistics and Exegesis in the Gospel of Mark: Applications of a Case Frame

Analysis. Journal for the Study of the New Testament Supplement Series 218. Studies inNew Testament Greek 10. Sheffield: Sheffield, 2001.

Davidson, A.B.Hebrew Syntax. 3d ed. Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1902.

Derrett, J. Duncan M. Studies in the New Testament: Volume 1. Leiden: Brill, 1977.

deSilva, David A.Honor, Patronage, Kinship & Purity: Unlocking New Testament Culture.

Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity, 2000.

Edwards, James R. The Gospel According to Mark. Pillar New Testament Commentary. Grand

Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002.

Ehrman, Bart D.Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. NewYork: HarperCollins, 2005.

English, Donald. The Message of Mark: The Mystery of Faith. The Bible Speaks Today.

Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity, 1992.

Flesher, Paul V. M. Bread of the Presence. Pages 780-1 in vol. 1 ofThe Anchor Yale BibleDictionary. Edited by David Noel Freedman. 6 vols. New York: Doubleday, 1996.

Fowler, Robert M. The Rhetoric of Direction and Indirection in the Gospel of Mark. Pages115-34 ofSemeia 48:Reader Perspectives on the New Testament. Edited by Edgar V.

McKnight. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 1989.

France, R. T. The Gospel of Mark. New International Greek Testament Commentary. Grand

Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002.

Gesenius, Friedrich Wilhelm. Gesenius Hebrew Grammar. Edited by E. Kautzsch and Sir

Arthur Ernest Cowley. 2d Eng. ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1910.

Guelich, Robert A.Mark 1-8:26. Word Biblical Commentary 34A. Dallas: Word, 1989.

Hamilton, Victor P.Handbook on the Historical Books. Grand Rapids: Baker, 2004.

Hamilton, Jr., James M. The Typology of Davids Rise to Power: Messianic Patterns in theBook of Samuel. A Julius Brown Gay Lecture presented at The Southern BaptistTheological Seminary on March 13, 2008. Downloaded 18 April 2011. Online:http://jimhamilton.wordpress.com/2008/03/14/the-typology-of-davids-rise-to-power-

messianic-patterns-in-the-book-of-samuel/.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

24/26

23

Hasel, Gerhard F. Sabbath. Pages 849-56 in vol. 5 ofThe Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary.Edited by David Noel Freedman. 6 vols. New York: Doubleday, 1996.

Hendriksen, William.Exposition of the Gospel According to Mark. New Testament

Commentary. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1975.

Joon, Paul and T. Muraoka.A Grammar of Biblical Hebrew. subsidia biblica 27. Roma:

Editrice Pontificio Intituto Biblico, 2006.

Keener, Craig S. The IVP Bible Background Commentary: New Testament. Downers Grove, Ill.:

InterVarsity, 1993.

Kernaghan, Ronald J.Mark. IVP New Testament Commentary. Downers Grove, Ill.:

InterVarsity, 2007.

Kittel, Gerhard, and Gerhard Friedrich, eds. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament.Translated by Geoffrey W. Bromiley. 10 vols. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1964-1976.

Lane, William L. The Gospel of Mark. New International Commentary on the New Testament.

Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1974.

Marcus, Joel.Mark 1-8. Anchor Yale Bible 27. Garden City: Doubleday, 1999. Repr., NewHaven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2008.

--------. The Way of the Lord: Christological Exegesis of the Old Testament in the Gospel of

Mark. New York: T&T Clark, 2004.

McCarter, Jr., P. Kyle.I Samuel. Anchor Yale Bible 8. Garden City: Doubleday, 1980. Repr.,

New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2008.

McCartney, Dan G. Ecce Homo: The Coming of the Kingdom As the Restoration of HumanViceregency. Westminster Theological Journal 56:1 (Spring 1994): 1-21.

Merrill, Eugene H.Everlasting Dominion: A Theology of the Old Testament. Nashville:

Broadman & Holman, 2006.

Moo, Douglas J. Jesus and the Authority of the Mosaic Law, Journal for the Study of the NewTestament 20 (1984): 3-49; Repr. pages 83-128 in The Historical Jesus: A Sheffield

Reader. Edited by Craig A. Evans and Stanley E. Porter. Sheffield: Sheffield, 1995.

Moulton, James Hope, and George Milligan. Vocabulary of the Greek New Testament. London:

Hodder and Stoughton, 1930.

Moulton, James Hope, and Nigel Turner.A Grammar of New Testament Greek, Volume 4: Style.

Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1976.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

25/26

24

The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: Series I. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. 14 vols.Repr. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1994.

Omanson, Roger L. and John Ellington.A Handbook on the First Book of Samuel. UBS

Handbook Series. New York: United Bible Societies, 2001.

Parrott, Rod. Conflict and Rhetoric in Mark 2:23-28. Pages 117-37 ofSemeia 64: The Rhetoricof Pronouncement. Edited by Daniel Patte. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 1993.

Robertson, A. T.A Grammar of the Greek New Testament in the Light of Historical Research.

Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 1947.

Runge, Steven E.A Discourse Grammar of the Greek New Testament: A Practical Introduction

for Teaching and Exegesis. Bellingham, Wash.: Logos Research Systems, Inc., 2010.

Schreiner, Thomas R.New Testament Theology: Magnifying God in Christ. Grand Rapids:Baker, 2008.

Schrer, Emil.A History of the Jewish People in the Time of Jesus Christ, Second Division, Vol.II. Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1890.

Shead, A. G. Sabbath.New Dictionary of Biblical Theology. Edited by T. Desmond Alexanderand Brian S. Rosner. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity, 2001.

Spicq, Ceslas. Theological Lexicon of the New Testament. Translated and edited by James D.Ernest. 3 vols. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1994.

Swete, H. B. The Gospel According to Saint Mark. New York: MacMillan, 1898.

Thielman, Frank. The Law and the New Testament: The Question of Continuity . New York:

Herder & Herder, 1999.

--------. Theology of the New Testament: A Canonical and Synthetic Approach. Grand Rapids:

Zondervan, 2005.

Tomson, Peter. If This Be From Heaven: Jesus and the New Testament Authors in TheirRelationship to Judaism. Sheffield: Sheffield, 2001.

Tsumura, David. The First Book of Samuel. New International Commentary on the OldTestament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007.

van Iersel, Bas M.F.Mark: A Reader-Response Commentary. Translated by W. H. Bisscheroux.

Journal for the Study of the New Testament 164. New York: T&T Clark, 2004.

-

8/6/2019 Grainfields on the Sabbath

26/26

25

Watson, Francis. Text, Church, and World: Biblical Interpretation in Theological Perspective.

New York: T&T Clark, 2004.

Watts, Rikk E. Mark. Pages 111-249 in Commentary on the New Testament Use of the OldTestament. Edited by G.K. Beale and D.A. Carson. Grand Rapids: Baker, 2007.

Williams, Matthew C. Two Gospels From One: A Comprehensive Text-Critical Analysis of the

Synoptic Gospels. Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2006.

Williamson, Peter. Catholic Principles for Interpreting Scripture: A Study of the Pontifical

Biblical Commissions The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church. subsidia biblica 22.

Roma: Pontificio Istituto Biblico, 2001.

Witherington III, Ben. The Gospel of Mark: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary. Grand Rapids:

Eerdmans, 2001.

--------.Jesus the Sage: The Pilgrimage of Wisdom. Minneapolis: T&T Clark, 1994.

Wright, N. T.Jesus and the Victory of God. Christian Origins and the Question of God 2.Minneapolis: Fortress, 1996.

Young, Richard A.Intermediate New Testament Greek: A Linguistic and Exegetical Approach.

Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 1994.