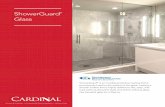

Glass

description

Transcript of Glass