Gingivitisasariskfactorin 1 2 and Harald Lo¨e ... · Fig.1. Experimental gingivitis in humans...

Transcript of Gingivitisasariskfactorin 1 2 and Harald Lo¨e ... · Fig.1. Experimental gingivitis in humans...

Gingivitis as a risk factor inperiodontal disease

Lang NP, Schatzle MA, Loe H. Gingivitis as a risk factor in periodontal disease. J ClinPeriodontol 2009; 36 (Suppl. 10): 3–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01415.x.

AbstractBackground: Dental plaque has been proven to initiate and promote gingivalinflammation. Histologically, various stages of gingivitis may be characterized prior toprogression of a lesion to periodontitis. Clinically, gingivitis is well recognized.

Material & Methods: Longitudinal studies on a patient cohort of 565 middle classNorwegian males have been performed over a 26-year period to reveal the naturalhistory of initial periodontitis in dental-minded subjects between 16 and 34 years ofage at the beginning of the study.

Results: Sites with consistent bleeding (GI 5 2) had 70% more attachment loss thansites that were consistenly non-inflamed (GI 5 0). Teeth with sites that wereconsistently non-inflamed had a 50-year survival rate of 99.5%, while teeth withconsistently inflamed gingivae yielded a 50-year survival rate of 63.4%.

Conclusion: Based on this longitudinal study on the natural history of periodontitis ina dentally well-maintained male population it can be concluded that persistentgingivitis represents a risk factor for periodontal attachment loss and for tooth loss.

Key words: epidemiology; gingivitis;periodontitis progression; prevention; riskfactor; tooth loss

Accepted for publication 4 April 2009

We are here in Stockholm this week tocelebrate the 100th Anniversary of theSwedish Dental Association and to con-gratulate our Swedish colleagues on theirmany important contributions to thescience and practice of dental medicine.

Let us be reminded, however, thatduring the first 50 years of the Associa-tion’s history, insufficient knowledgeexisted regarding the nature and causesof periodontal disease, and there was

little agreement on their clinical man-agement both in Sweden and worldwide.

It was from this state of ignoranceand professional inaction that the Scan-dinavian school, led by Dr. Jens Wær-haug during the early 1950s, initiatedwhat would amount to a revolution inperiodontal research and practice.

Dental Plaque

First microscopic and electron micro-scopic research revealed the intimaterelationship between dental plaque andthe gingival and periodontal tissues.

Then, epidemiological studies in manycountries pointed to a close associationbetween tooth deposits and periodontaldiseases.

Finally, in 1965, the experimentalgingivitis studies demonstrated that theaccumulation of plaque on healthy gin-giva produced gingivitis (Loe et al.1965) (Fig. 1a–d), and that after reinsti-tution of oral hygiene measures for 7

days, the gingiva reverted back to nor-

mal (Fig. 2). These studies also

described the sequential developmentof gingival plaque from a simple mono-

layer of Gram-positive coccoid bacteria

colonizing the enamel surface and themarginal gingiva to a complex microbial

plaque dominated by Gram-negative

anaerobic cocci, filaments and spiro-chetes (Theilade et al. 1966). These

and other studies came to be the ulti-

mate documentation that bacterial pla-

que was something very different fromfood debris, something much more col-

ourful than Materia Alba, and much

more interesting than just ‘‘Schmutz’’(Fig. 3a and b). Consequently, the

research to understand more fully the

interaction between the infectious

agents and the lost tissues in the transi-tion from health to disease, and in the

progression from gingivitis to perio-

dontitis was intensified.Supragingival plaque related to heal-

thy gingival tissues has a bacterial com-

Niklaus P. Lang1, Marc A. Schatzle2

and Harald Loe1Prince Philip Dental Hospital,

Comprehensive Dental Care, The University

of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China; 2Center

for Dental and Oral Medicine and Cranio-

Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Zurich,

Zurich, Switzerland

Conflict of interest and source offunding statement

The symposium ‘‘Inflammation: is it athreat to your patients’’ was presented atthe FDI World Dental Congress in Stock-holm Sweden in September 2008 andfunded by Johnson & Johnson. The authorsreceived a speaking engagement fee and afee for the preparation of this manuscriptfrom Johnson & Johnson Ltd. The studieshave been partially funded by the ClinicalResearch Foundation (CRF) for the Promo-tion of Oral Health, Brienz, BE, Switzer-land.

Dedication:

This manuscript is dedicated to the memory

of our co-author, Harald Loe, friend, colleague

and mentor, who died on 9 August 2008 during

the preparation of this paper. Harald’s foresight

in carrying out the surveys on the natural history

of periodontal disease made it possible to

answer the pertinent questions on the significant

role of gingivitis in periodontitis progression

and tooth loss. Originally, he was scheduled to

present this paper at the FDI Congress in Stock-

holm in September 2008.

J Clin Periodontol 2009; 36 (Suppl. 10): 3–8 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01415.x

3r 2009 John Wiley & Sons A/SJournal compilation r 2009 John Wiley & Sons A/S

position that is different from that ofplaque associated with gingivitis, whichagain is different from the make-up ofsubgingival plaque of the progressing oradvanced periodontal lesion.

Perhaps 4300 different types ofmicroorganism have been found inwell-developed human dental plaque,some of which have been identified,and others have not been identified.Some may be important in the patho-genesis of the disease, and others maynot. Research, so far, suggests that it isnot one or two organisms that areresponsible for periodontal pathology,but several. Today, there is a relativeagreement among authorities that atleast seven to eight organisms are fairlycertain to be involved in various types ofperiodontal disease. These are:

Aggregatibacter actimomycetemco-mitans,Porphyromonas gingivalis,Tannerella forsythia,

Prevotella intermedia,Campylobacter rectus,Spitochetes.

Those and possibly other not yetidentified organisms are considered tobe important in gingivitis development,in progression from gingivitis to perio-dontitis, as well as in the advancinglesion of both chronic and aggressiveperiodontitis.

The fact that seven to eight organismsin varying combinations may relate tothe various aspects of the disease canhardly satisfy the criteria for the so-called ‘‘specific plaque hypothesis’’,and some may be on the side of thosewho speak in favour of the ‘‘non-speci-fic plaque hypothesis’’. The least thatcan be said about the specificity of theperiodontal infection is that the Gram-negative, anaerobic microbiota con-tinues to be prominent both in gingivitisdevelopment and in the advancing oradvanced periodontal lesion. The spir-ochetes are persistently interesting, but,because culturing has been difficult,they have not regularly been part ofthe protocols. Finally, perhaps mentionshould also be made of the suggestionthat development of human aggressiveperiodontitis has been associated withcombinations of herpes viruses andputative periodontopathic bacteria.

Over the past few years, a new wordhas found its way into the discussionfor what people understand as dentalbacterial plaque. The catchword is ‘‘bio-film’’. After periodontal research hasused more that 100 years since Dr.Black first introduced the term dental

plaque to subject this material to scien-tific scrutiny, plaque is now reasonablywell described and widely understood.However, new aspects of the life withinthe bacterial community with its struc-tures of communication as well as thephenomenon of quorum sensing justifythis new term as an expression of ourmore detailed understanding of the bio-film.

Histopathology

In most cases, initial plaque develop-ment starts in the niche created wherethe gingival margin meets the toothsurface (Fig. 4). In these cases, thebacterial plaque is located adjacent tothe non-keratinized crevice epithelium,and the bacteria would have to exerttheir effect from this juxta position. Inother instances, the microorganismsseem to invade the tissues. In eithercase, tissue destruction will occur as adirect result of microbial action throughtheir release of toxins, lipopolysacchar-ides or enzymes, or indirectly, as a resultof activation of the patient’s cellular andbacterial inflammatory systems – the so-called host responses, which may serveto both damage and protect the perio-dontal tissues.

Although no one has directlyobserved the earliest stages of gingivitisdevelopment, it is surmised that theseinclude processes germane to acuteinflammation:

� transudation of serum through thevascular endothelium,

� extravasation of leucocytes and theiroutward emigration,

� widening of the intercellular spacesof the surface epithelia and

� gradual release of immuno-inflam-matory mediators with a variety ofpotentials, such as cytokines [inter-leukin (IL)-1a, ILb, IL-6, IL-8 andtumour necrosis factor-a].

These and others have proven theireffects on signalling gene expression,mobilizing of inflammatory cells inmediating the release of enzymes likecollagenases, other proteolytic enzymes,including the metallo-proteinases, whichare responsible for the degradation, andthe extracellular matrix of the connec-tive tissue. Also, these in turn give riseto potent products, such as prostaglan-dins, particularly PGE2 and others thatare involved in several inflammatory

Fig. 2. Experimental gingivitis in humans(Loe et al. 1965). Same subject as in Fig. 1,but after 10 days of re-instituted oral hygienepractices. Plaque removal resulted in theresolution of inflammation. Clinically per-fect gingival conditions.

a b

dc

Fig. 1. Experimental gingivitis in humans (Loe et al. 1965): (a) Clinically plaque- andinflammation-free dentition of an experimental subject on Day 0. (b) Same subject after7 days of abolished oral hygiene. (c) Two weeks of abolished oral hygiene results inlocalized early signs of gingivitis (tooth 11). (d) Same subject at the end of a 3-week periodof nooralhygiene. Plaque accumulation resulted in the development of a generalizedgingivitis.

4 Lang et al.

r 2009 John Wiley & Sons A/SJournal compilation r 2009 John Wiley & Sons A/S

processes during the progression of thedisease, of which bone resorption mightbe the most important.

Also during the early stages of theprocess, various bacterial antigens willelicit the production of antibodies,mobilize the complement system andrelease other immunoglobulins, alongwith the emergence of phagocytic cells

such as plasma cells and activation ofother cell types such as lymphocytesand macrophages (Fig. 5a and b). Asthese complex processes pervade themarginal gingiva, the developing gingi-val lesion matures into chronic gingivi-tis, with massive accumulations of cellsand fluid overtaking the connectivetissues stroma.

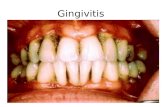

Clinical Gingivitis

The earliest clinical sign of gingivalinflammation is the transudation of gin-gival fluid. This thin and almost a cel-lular transudate is gradually superscededby a fluid consisting of serum plusleucocytes.

The redness of the gingival marginarises partly from the aggregation andenlargement of blood vessels in theimmediate subepithelial connective tis-sue and the loss of keratinization of thefacial aspects of gingiva (Fig. 6a and b).

Swelling and loss of texture of thefree gingiva reflect the loss of fibrousconnective tissue and the semi liquidityof the interfibrillar substance.

Individually and collectively, theclinical symptoms of chronic gingivitisare rather vague, and usually painless.These features leave most patients una-ware of the disease and are generallyunderestimated by the dental practi-tioners. Chronic gingivitis rarely showsspontaneous bleeding. The fact that thegingival tissues can be provoked tobleed just by touching the gingivalmargin with a blunt instrument (Fig. 7)[as during tooth brushing or in assessingthe gingival index (GI)] suggests thatthe epithelial changes and the vasculartransfigurments are quite conspicuous.

Progression to Periodontitis

Cross-sectional epidemiological studiesfrom many countries have indicatedthat gingivitis is common both in primaryand in secondary dentitions of children,and affects most adults. National prob-ability surveys in some industrializedcountries have found that gingivitisoccurs in the majority of teenagers andadults, but that only a few, perhapso10% of the total gingival sites, ‘‘bleedon probing’’ (GI 5 2). Similar data basedon probability samples are not availablefor developing regions, but it has beensuggested that gingivitis might be highlyprevalent, extensive and severe.

The distribution of gingivitis in anypopulation is important since currenttheory holds that the gingival lesion isthe precursor of periodontitis. Clearly,not all gingivitis lesions progress toperiodontitis. Actually, the proportionof gingival lesions converting to perio-dontitis, and the factor causing thisconversion have not been well under-stood. Most seem to think, however, thatthe established periodontitis lesion waspreceded by gingivitis.

Fig. 4. Plaque begins to form in the gingival sulcus and other protected niches of the tooth.(a) Destruction of collagen will occur as a direct result of microbial action through theirrelease of toxins, lipopolysaccharides or enzymes. (b) Bacterial plaque forms as a biofilm inthe gingival sulcus shortly after the cleansing of the tooth surface. Three-day-old plaque.

Fig. 3. Experimental gingivitis in humans (Loe et al. 1965). Graphs demonstrating the cause-and-effect relationship between dental plaque and the development of gingivitis (b). As thePlaque indices increase (a), the gingival indices follow, yielding the host response to thebacterial challenge (b). Following re-institution of oral hygiene (a), gingival health is, again,reached within a week to 10 days (b).

Gingivitis as a risk factor 5

r 2009 John Wiley & Sons A/SJournal compilation r 2009 John Wiley & Sons A/S

While traditional cross-sectionalhuman surveys may describe reasonablywell the distribution of disease and theassociated factors, cross-sectional stu-dies are unable to characterize the con-tinuous process and the temporal andspatial relationships between the variousfactors influencing the initiation and theprogression of the disease. Also, thedetermination of the cause of a diseaseor the definition of the true risk factorsof a disease requires a longitudinaldesign of a study.

Longitudinal Studies

The material presented in this review isobtained from longitudinal studies ofperiodontal disease in humans (Heitz-Mayfield et al. 2003, Schatzle et al.2003a, b, 2004).

The cohort was established in OsloNorway in 1969, and consisted of 565randomized healthy, well-educatedmales between 16 and 34 years old.All participants were born in Oslo, andall had been enrolled in the CityDental Program during childhood, andreported to have subsequently seentheir private dentist on a regular basis,as well as performing daily oral hygienecare.

Subsequent clinical examination ofthe participants occurred in 1971,1973, 1975, 1981, 1988 and 1995. Asin most longitudinal investigations ofthis size and length, a certain memberof the participants dropped out, andcould not be followedup. Others wouldmiss one or more examinations, butmight show up for the last survey; 223men showed up for the last examinationcovering the entire age range from 16 to60 years.

The following clinical indices werecollected during the 26-year observationperiod: plaque index, GI, calculus index,caries index, gingival recession and lossof attachment. (Pocket depths werederived from calculating LA and GRI.)

These studies have shown that inwell-educated middle-class men whohad received state-of-the-art professionaland personal dental care during child-hood, adolescence and adulthood, thedentition is maintained in health andfunction throughout life. The 16-year-old boys had 27.4 teeth (excluding wis-dom teeth), and as the men approached60 years, they still had 27.1 teeth. Theyhave lost 0.3 teeth in 45 years of adult

a b

Fig. 6. Aggregation and enlargement of blood vessels in the immediate subepithetialconnective tissue. (a) Vital microscopy of a clinically healthy gingival margin. Presence ofnumerous fine capillary networks. (b) Vital microscopy of a gingival margin presenting withgingivitis. Capillary loops are enlarged. Clinically, these changes are recognized as rednessand swelling of the gingival margin.

Fig. 7. In health, the insertion of a blunt instrument or probe into the gingival crevicewill maintain its integrity. However, bleeding may be induced as a result of developinggingivitis.

a b

Fig. 5. (a) Photomicrograph of a gingivitis lesion. The inflammatory infiltrate is clearlyvisible: extravasations of leucocytes and their outward emigration, widening of the inter-cellular spaces of the surface epithelia and a gradual release of immuno-inflammatorymediators with a variety of potentials. (b) Higher magnification of (a): Bacterial plaqueis located adjacent to the non-keratinized crevice epithelium. Emergence of phagocyticcells such as plasma cells and activation of other cell types such as lymphocytes andmacrophages.

6 Lang et al.

r 2009 John Wiley & Sons A/SJournal compilation r 2009 John Wiley & Sons A/S

life, and the mortality rate was 0.01 teeth/year (Schatzle et al. 2004)

Although none of the participants atany one survey exhibited a dentitioncompletely free of plaque, it is note-worthy that approximately 60–70% ofthe total tooth surfaces were either pla-que free or scored Pl I 5 1 (invisibleplaque), and that throughout the agerange (16–60 years) only 20–30% ofthe surfaces scored Pl I 5 2 (visibleplaque).

Gingival indices also varied verylittle during adult life and rangedbetween GI 5 0.1 and 0.9. In otherwords, the gingival health of this groupof people must be characterized as goodto excellent, and the frequency ofGI 5 2 scores (bleeding on probing)occurred only in 10–20% of sites in allmen 16–60 years of age (Schatzle et al.2003a).

Attachment loss occurred in a fewsites already at 16 years, but mainly asgingival recession on buccal surfaces(Heitz-Mayfield et al. 2003). Deepenedpockets were scarce below 40 years ofage, and rarely exceeded 3.4 mm indepth. The mean individual loss ofattachment (LA) and the frequency ofsites with attachment loss increasedsomewhat during the 40s and 50s,and reached a maximum (LA 52.44 mm) as the men approached 60years. However, o0.5% of the siteshad lost 44 mm.

To analyse the role of gingivalinflammation in the pathogenesis of theperiodontal lesion, three gingival indexseverity groups were established acrossall age groups according to their degreeof clinical inflammation scores over the26-year observation period (Schatzleet al. 2003a).

The results show that gingival unitsthat consistently scored GI 5 0 experi-enced a mean cumulative LA over the60 years life span of o2 mm (range0.08–1.94). This attachment loss essen-tially occurred in buccal sites of youngmen below 40 years, displaying gingivalrecession. Sites with slight inflammation(GI 5 1) showed a cumulative attach-ment loss of 42 mm (range 0.17–2.42),and in sites that consistently bleed onprobing (GI 5 2), the mean LA was43 mm (range 0.04–3.53) (Schatzleet al. 2003a) (Fig. 8).

From the age of 40 and 50 years,pocket formation increased in extent anddepth in sites exhibiting gingival inflam-mation. As the men approached 60 yearsof age, gingival sites that, throughoutthe observation period consistentlybleed on probing, had 70% more attach-ment loss than sites that consistentlywere non-inflamed, yielding an oddsratio of 3.22 for inflamed sites convert-ing to attachment loss. Also, subgingivalcalculus formation increased the oddsratio for converting to attachment loss to4.22, for the GI 5 2 group, comparedwith sites of the GI 5 0 cohort (Schatzleet al. 2003a).

From this part of the analysis, it wasconcluded that it has now convincinglybeen demonstrated that the developmentof periodontitis only occurs in areas oflong-standing gingivitis.

In order to further elucidate the tran-sition from gingivitis to peridoontitis,the incidence of the initial loss ofattachment over the 60-year life spanwas next assessed (Heitz-Mayfield et al.2003). The loss of the first 2 mm or moreof periodontal attachment as measuredapically from the cemento-enamel junc-tion was termed as initial loss of attach-

ment (ILA). The incidence of ILA wasestablished for all age levels, all teethand groups of teeth as well as for thetype of lesion expressed (gingival reces-sion, pockets alone or in combinationwith recession). Again, and not surpris-ingly, at age 20 years and before ILAoccurred in a few buccal sites in a fewindividual and almost all were gingivalrecessions.

At 40 years of age, still o10% of thesites with ILA showed either pocketformation or condensation of attachmentloss and pocketing. As the men aged 50,55, 60 years, however, approximately30%–50% of the sites had ILA (Heitz-Mayfield et al. 2003).

It appears then that the incidence ofattachment loss of X2 mm expressed asdeepening of the periodontal pocket isabsent or extremely low during the earlyyears of life. In fact, gingival recessionwas the dominant type of initial attach-ment loss during the first 40 years oflife. Pocket formation starts earliestaround 50 years of age, and increasesin incidence towards the age of 60.

Another analysis of this uniquecohort aimed at the assessment of thelong-term influence of gingival inflam-mation on tooth survival (Schatzle et al.2004).

For tooth-specific calculations, threegingival index groups reflecting theirhistory of inflammation over the 26 yearswere established. For this reason, theminimal and maximal GI value over allsites was determined:

� Severity I: teeth consistently scoringa minimum of GI 5 0 and a max-imum of GI41 in all sites.

� Severity II: teeth in which all sitesalways scored a minimum of GI 5 1and a maximum of GI42.

� Severity III: teeth that always scoreda minimum of GI 5 2 (bleeding onprobing) in all sites and at all obser-vations.

All other teeth not fulfilling thesecriteria were not considered for furtherevaluation.

Four hundred and eighty-seven pa-tients with 13,285 teeth in 1969 werefollowed up for at least two surveys. Ofthe 487 subjects, 412 (85%) had lost noteeth and the remaining 75 of the re-examined individuals accounted for the126 teeth lost.

The Kaplan–Meier cumulative survi-val distribution (Fig. 9) for the threedefined GI Severity Groups showed

3.5

2.5

3

2

1

1.5

0

0.5

Mea

n Lo

ss o

f Atta

chm

ent i

n m

m

< 20 20 - 24 25 - 29 30 - 34 35 - 39 40 - 44 45 - 49 50 - 54 55 - 59

Age Group

Gingival Index = 2

Gingival Index = 0

Gingival Index = 1

Fig. 8. Effect of different gingivitis levels on the loss of attachment. The development ofperiodontitis only occurs in areas of long-standing gingivitis (from: Schatzle et al. 2003a).

Gingivitis as a risk factor 7

r 2009 John Wiley & Sons A/SJournal compilation r 2009 John Wiley & Sons A/S

that before a tooth age of approximately15 years, tooth loss was extremely rare.After a tooth age of 20 years, GI SeverityGroup III yielded a significantlyincreased cumulative tooth loss whencompared with both GI Severity GroupsII and I.

It is remarkable to note that GISeverity Group I, where no bleedingon probing was ever scored throughoutthe observation period, yielded a cumu-lative tooth survival of 99.5% at a toothage of 51 years. This suggests thatclinically healthy gingiva is a prognos-tic indicator of tooth longevity.

The fact that the GI Severity Group IIdemonstrated a cumulative tooth survi-val rate of 94% after 51 years of toothage supports the concept that occasion-ally, bleeding tooth sites provide a muchsmaller risk for tooth loss than regularlybleeding gingivae.

The risk of losing a tooth showed awide range of odds ratios. Teeth alwayssurrounded by healthy or slightly infla-med gingiva had an 8.4 times lower riskof being lost as compared with teethsurrounded by an inflamed gingiva thatoccasionally bled on probing, and a 45.8times lower risk than teeth that werealways surrounded by an inflamed gin-giva that bled on probing. Teeth withslightly inflamed gingiva had a 5.4 timeslower risk of tooth loss than those thatshowed bleeding on probing.

This study has clearly established thatgingival inflammation was a risk factorfor tooth loss. Teeth consistently sur-rounded by inflamed gingiva at all sur-veys during the 26-year observationperiod had a significantly higher riskof being lost than teeth with no or onlyslight inflammation.

References

Heitz-Mayfield, L. J., Schatzle, M., Loe, H.,

Burgin, W., Anerud, A., Boysen, H. & Lang,

N. P. (2003) Clinical course of chronic

periodontitis. II. Incidence, characteristics

and time of occurrence of the initial perio-

dontal lesion. Journal of Clinical Perio-

dontology 30, 902–908.

Loe, H., Theilade, E. & Jensen, S. B. (1965)

Experimental gingivitis in man. Journal of

Periodontology 36, 177–187.

Schatzle, M., Loe, H., Burgin, W., Anerud, A.,

Boysen, H. & Lang, N. P. (2003a) Clinical

course of chronic periodontitis. I. Role of

gingivitis. Journal of Clinical Periodontology

30, 887–901.

Schatzle, M., Loe, H., Lang, N. P., Burgin, W.,

Boysen, H. & Anerud, A. (2004) The clinical

course of chronic periodontitis. IV. Gingival

inflammation as a risk factor in tooth mortal-

ity. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 31,

1122–1127.

Schatzle, M., Loe, H., Lang, N. P., Heitz-

Mayfield, L. J., Burgin, W., Anerud, A. &

Boysen, H. (2003b) Clinical course of

chronic periodontitis. III. Patterns, variations

and risks of attachment loss. Journal of

Clinical Periodontology 30, 909–918.

Theilade, E., Wright, W. H., Jensen, S. B. &

Loe, H. (1966) Experimental gingivitis in

man. II. A longitudinal clinical and bacter-

iological investigation. Journal of Perio-

dontal Research 1, 1–13.

Address:

Niklaus P. Lang

Prince Philip Dental Hospital

Comprehensive Dental Care

The University of Hong Kong

34, Hospital Road

Sai Ying Pun

Hong Kong

China

E-mail: [email protected]

Clinical Relevance

Scientific rationale for the study:Gingivitis may be perceived as aprotective host response against thebacterial challenge. It is unclearwether or not gingivitis may lead todetrimental effects.

Principal findings: Teeth with con-sistently inflamed dentogingival unitsshowed over a 26-year observationperiod greater attachment loss and ahigher chance for tooth loss than teethwith consistently non-inflamed dento-gingival units.

Practical implications: Inflammationof the gingival tissues represents notonly the precursor of periodontitisbut also a clinically relevant riskfactor for disease progression andtooth loss.

99.5 %

0.75

0.50

1.00 93.8 %

63.4%

0.25

Sur

viva

l Dis

trib

utio

n F

unct

ion

0.000 10 20 30 40 50 60

Tooth Age in years

GI Severity Group III

GI Severity Group II

GI Severity Group I

Fig. 9. Effect of different gingivitis levels on tooth loss. Survival distribution function fordifferent gingival index Severity Groups. After 50 years of tooth age, the cumulative survival forteeth with healthy gingival tissues is 99.5%. Teeth with always bleeding gingivae demonstrate acumulative survival of 63.4% after 48 years of tooth age (from: Schatzle et al. 2004).

8 Lang et al.

r 2009 John Wiley & Sons A/SJournal compilation r 2009 John Wiley & Sons A/S