Genesis of monuments CORTELETTI (1).pdf

-

Upload

pedro-fortes -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

Transcript of Genesis of monuments CORTELETTI (1).pdf

-

7/26/2019 Genesis of monuments CORTELETTI (1).pdf

1/17

The genesis of monuments: Resisting outsiders in the contestedlandscapes of southern Brazil

Jonas Gregorio De Souza a,, Rafael Corteletti b, Mark Robinson a, Jos Iriarte a

a Department of Archaeology, University of Exeter, Laver Building, North Park Road, Exeter EX4 4QE, United Kingdomb Departamento de Antropologia, Universidade Federal do Paran, Rua General Carneiro, 460 6o andar, Curitiba, Paran 80.060-150, Brazil

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:Received 13 September 2015Revision received 7 January 2016

Keywords:

Southern Brazilian highlandsSouthern proto-JMound and enclosure complexesTupi-GuaraniCrisis cultCostly signaling

a b s t r a c t

In this article, we examinethe emergence of thefunerary moundand enclosurecomplexes of thesouthernBrazilian highlands during the last 1000 years in relation to processes of population expansion, contact,conflict and the establishment of frontiers. We test the hypothesis that such monuments emerged amongthelocal southern proto-Jpeoplesas a responseto themigration of a foreign group, theTupi-Guarani. Wecompared the spatio-temporal distribution of mound and enclosure complexes in respect to sites ofinteraction between the two groups. The results indicate that the rise of funerary architecture coincideswith the first incursions of the Tupi-Guarani to the southern proto-J heartland, and that mounds areconcentrated in areas devoid of interaction. We conclude that highly monumentalized landscapesemerged in areas where local groups chose not to interact with the Tupi-Guarani, showing that funerarymonuments were an important component in the establishment of impermeable frontiers to resistoutsiders.

2016 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

With the advantage that we are no longer bound to the essen-tialist approaches of culture history, archaeologists are once againrecognizing that the movement of peoples and ideas occurred fre-quently in the past and had major consequences for trajectories ofethnogenesis (Heckenberger, 2005, 2011; Politis and Bonomo,2012). Under novel theoretical approaches, we are now assessingthe impact of migrations in the congealment of ethnicities, the cre-ation of political landscapes, and the invention of traditions in thepast (Bernardini, 2005a, 2005b, 2011; Hornborg, 2005; Pauketat,2005, 2007, 2010; Pauketat and Loren, 2005; Sassaman, 2005,2010; Whitehead, 1994). Of prime importance to archaeology are

the material expressions of those processes; one phenomenon thatis repeatedly observed during periods of intense cultural interac-tion, hand in hand with the establishment of frontier zones, isthe rise of novel architectural expressions that materialize andshape the formation of new identities (Dillehay, 2007; Pauketat,2007; Sassaman, 2005).

The monumental funerary earthworks of the southern proto-Jgroups in the southern Brazilian highlands are a case in question.Despite more than six decades of research (Chmyz, 1968; Chmyz

et al., 1968; Menghin, 1957; Naue et al., 1989; Ribeiro andRibeiro, 1985; Rohr, 1971), only recently have archaeologistsshifted their focus in the study of southern proto-J earthworksfrom more descriptive approaches to the investigation of ritualpractices, the degree of political complexity and territoriality(Cop et al., 2002; De Masi, 2009; De Souza, 2012; De Souza andCop, 2010; Iriarte et al., 2013, 2008, 2010; Saldanha, 2008). Inter-estingly, renewed archaeological work in the Rio de la Plata basin isbeginning to provide a broader picture, showing that the southernproto-J monuments developed over the last 1000 years amidst aregional mosaic of migrations, increased population densities andintensifying interaction (Bonomo et al., 2015, 2011; Iriarte et al.,in press, 2008; Politis and Bonomo, 2012; Politis et al., 2011). How-

ever, the role of such an ethnic mosaic in the rise of a novel archi-tectural tradition in the southern Brazilian highlands has neverbeen assessed.

In this article, we test the hypothesis that the appearance ofsouthern proto-J mound and enclosure complexes over the last1000 years is related to the largest population expansion in low-land South America in recent times, that of the Tupi-Guarani lan-guage family (Bonomo et al., 2015). We hypothesize that therapid advance of the Tupi-Guarani along major river routes led tothe circumscription of some southern proto-J groups in the high-lands. Specifically, a core area of the southern proto-J groups inthe CanoasPelotas river basins chose not to interact with the

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2016.01.003

0278-4165/2016 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Corresponding author.

E-mail address:[email protected](J.G. De Souza).

Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 41 (2016) 196212

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Anthropological Archaeology

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / j a a

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2016.01.003mailto:[email protected]://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2016.01.003http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/02784165http://www.elsevier.com/locate/jaahttp://www.elsevier.com/locate/jaahttp://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/02784165http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2016.01.003mailto:[email protected]://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2016.01.003http://crossmark.crossref.org/dialog/?doi=10.1016/j.jaa.2016.01.003&domain=pdf -

7/26/2019 Genesis of monuments CORTELETTI (1).pdf

2/17

outsiders, establishing an impermeable social frontier. This iswhere the earliest funerary monuments were raised. We proposethat these groups reacted to the Tupi-Guarani advance by design-ing an unprecedented political landscape, dotted by funerary mon-uments dedicated to chiefly lines as a powerful statement ofresistance to the outsiders.

2. Monuments, frontiers and identities

The emergence of monumental architectural expressions,especially with a public character, during moments of rapidsocio-political change and cultural interaction (or conflict) is a phe-nomenon observed in many parts of the world and time periods.Migrations are particularly prone to triggering this process, as localand long-distance relocation of groups leads to the juxtaposition ofidentities, resulting in novel socio-political arrangements and tra-ditions that are ultimately projected on the landscape (Pauketat,2007; Pauketat and Loren, 2005). The role of population displace-ments, multi-ethnic formations and the negotiation of identitiesin the rise of new architectural traditions has been extensivelydebated by North American archaeologists, from the Archaic per-iod earthworks and exchange network of Poverty Point(Sassaman, 2005) to the Mississippian period shaping of authorityin the elite mounds of Cahokia (Pauketat, 2005, 2007), and to thesouthwestern Puebloan communities (Bernardini, 2005a, 2005b).

In South America, one of the clearest examples comes from thearchaeology and ethnohistory of the Araucanians of Chile.Dillehay(2007)has provided a detailed account of how Araucanian leadersexpanded their power through the sponsorship of ceremonies andmound building, creating a ceremonial mounded landscape anduniting a previously decentralized population in order to resistoutsiders. The peaks in mound-building activity coincide withperi-ods of invasion of Araucanian territory by foreign powers, first bythe Inka, later by the Spanish.Dillehay (2007)argues that the con-tact with outsiders led the Araucanians to a world of awareness,

manifested in the proliferation of chiefly burial mounds that cre-ated a landscape of lineage connecting people to places. In otherwords, the threat of invasion by outsiders led to the emergence of aconstructed political landscape (Smith, 2003).

This phenomenon is not without parallels in the old world. Forexample, Sherratt (1990) offers a similar interpretation for theemergence of megaliths in Northwestern Europe during the Neo-lithic a period for which the role of local invention versus foreigninfluences has been widely debated. He suggests that megalithicsites developed as an essential part of the interaction betweenlocal groups and newcomers. The migratory waves that undoubt-edly were part of the Neolithic scenario would have provided aninitial stimulus that gave rise to a complex reaction and interactionprocess.Sherratt (1990)argues that these foreign incursions coin-

cided with the development of novel forms of megalithic architec-ture, in themselves the apparatus of new forms of cult, whichSherratt sees as a sort of revivalistic religious movement. TheEuropean Neolithic has also been examined under a similar per-spective by Vandkilde (2007), who appropriately labelled it an ex-tra hot period, a transitory moment when the spread of new ideasand peoples led to fundamental changes of local identities. Periodssuch as these are called by Vandkilde (2007) macro-regionalphases of conjuncture, a concept that can be extended to theaforementioned cases.

The question that naturally emerges is why a new ceremonialapparatus, often in the form of monumental burial facilities andfunerary rites, should so frequently develop in situations of intensi-fied cross-cultural interaction and conflict. Perhaps part of the

answer lies with the phenomenon of crisis cults long known toanthropology (La Barre,1971). Crisiscultsare definedas punctuated

religious developments that constitute a ritual reaction by asociety undergoing stress, and it has been noticed that they oftenappear in contexts of increased ethnic contact (Driessen, 2001; LaBarre, 1971).

Another major question is why the situations of migrations,invasions and conflict that can lead to the formation of crisis cultsalso favors the expression of those rites by means of new monu-

mental architectural traditions. In many of the cases reviewedabove, the new ceremonial architecture that emerges in situationsof ethnic conflict also materialize new forms of authority thatappear during turbulent periods (Dillehay, 2007; Pauketat, 2007).Monuments have the potential of testifying to the ability of power-ful individuals or groups to deploy labor and resources; to para-phrase Trigger (1990), monuments do not only make powervisible, they also become power. Therefore, the construction ofhighly monumentalized landscapes needs to be understood as crit-ical to the constitution of authority: built environments are notmerely a reflection of the course of historical events, but also helpto shape them (Smith, 2003).

Finally, the emergence of monuments has also been revisited byarchaeologists working under an evolutionary perspective. Theyargue that behaviors such as conspicuous consumption and waste-ful spending (for instance, in the construction of monuments) canbe used to enhance social prestige because they are a form ofsmart advertising of the competitive abilities of leaders(Neiman, 1997). From an evolutionary point of view, the wastefulbehavior represented by monument building can be consideredas a form of costly signaling, that is, a display of wealth thatadvertises a hidden quality of the sender (Ames, 2010; Boone,2000). One corollary is that the proliferation of monuments in situ-ations of inter-ethnic conflict canbe understood as a form of adver-tising to outsiders that they will not be met without resistance. Inthat sense, the high visibility of monuments makes them a goodcandidate for the overt, intentional and assertive demarcation ofterritories (OShea and Milner, 2002).

3. The southern Brazilian highlands as a contested landscape

During the last 2000 years, southern Brazil was part of a regio-nal mosaic of archaeological cultures, where a range of local tradi-tions and migratory waves met, competed and interacted (Bonomoet al., 2015, 2011; Iriarte et al., in press, 2008; Politis and Bonomo,2012; Politis et al., 2011; Rogge, 2005).

In the temperate highlands, the local Taquara/Itarar Traditionhas long been recognized as representing the material correlateof speakers of the southern branch of the J linguistic family(Noelli, 2005). The depth of regional linguistic diversity withinthe J family points to the central Brazilian savannas as their likelyhomeland (Urban, 1992). The continuity between the archaeologi-

cal Taquara/Itarar Traditionand the historical southern J peoples,as argued by archaeologists (Noelli, 2005), anthropologists (DaSilva, 2001) and historians (Dias, 2005) is the reason why we referto them as the southern proto-J groups.

At the same time that the southern Brazilian highlands weresettled by the southern proto-J groups, the warm subtropicaldeciduous forests along the major rivers of the Rio de la Plata basinwere occupied by the Tupiguarani Tradition (Bonomo et al., 2015;Milheira and DeBlasis, 2014). It is a consensus that this traditionrepresents the ancestors of historical speakers of the Tupi-Guarani language family, whose internal diversity points to asouthwestern Amazonian origin (Noelli, 1998, 2008; Rodriguesand Cabral, 2012; Urban, 1992).

We present nowa brief overview of southern proto-J and Tupi-

Guarani archaeology, before examining the cases of interaction andresistance. Because the focus of this article is those two archaeo-

J.G. De S ouza et al. / Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 41 (2016) 196212 197

http://-/?- -

7/26/2019 Genesis of monuments CORTELETTI (1).pdf

3/17

logical traditions we will not mention other traditions of the Rio dela Plata basin, but the reader must be aware of the rich culturaldiversity of this region during the last 2000 years (Bonomo et al.,2015, 2011; Iriarte et al., in press, 2008; Politis and Bonomo,2012; Politis et al., 2011).

3.1. The southern proto-J

Historical accounts depict the southern J groups as regionallyorganized, politically complex societies. In the 19th century, theKaingang were divided in a number of chiefdoms with two tiersof hierarchy, with a paramount chief presiding over subordinatelocal chiefs (Becker, 1976; Fernandes, 2004; Mabilde, 1897, 1899,1983). Paramount chiefs enjoyed a number of privileges, includingthe right to polygyny and to lavish burial ceremonies that endedwith the raising of a funerary mound. They waged constant waragainst rebel sub-chiefs and enemy groups, determined the loca-tion of settlements, and divided theAraucaria(Paran pine) forestsamongst their subordinates (Mabilde, 1897, 1899, 1983). SouthernJ groups were semi-sedentary and practised a mixed economycombining small-scale cultivation, hunting and gathering of thepinho, the nutritious seed of the Araucaria, which was stored tolast for the winter. However, some Kaingang tribes and all of theXokleng had abandoned agriculture in favor of the mobilitygranted by hunting and gathering, partly as a response to the Euro-pean conquest (Henry, 1941). Traditionally, southern J groupswere divided into patrilineal exogamous moieties, further subdi-vided into moieties of ritual significance (Da Silva, 2001;Nimuendaj, 1993; Veiga, 1994).

The Taquara/Itarar Tradition, which is the material correlate ofthe southern proto-J groups, dates back to ca. 2220 B.P. andextends to the colonial period. It was originally characterized byits diagnostic small ceramics with thin walls. Surface treatmentsinclude black burnishing and a variety of plastic decorations punctations, fingernail impressions, incisions withvarious geomet-ric motifs, basketry and chord impressions. Beyond the ceramics,

we now recognize other traits characteristic of this broadly dis-persed tradition, such as the construction of domestic and ceremo-nial earthworks (e.g. Araujo, 2007; Beber, 2005; De Masi, 2009;Iriarte et al., 2013; Noelli, 2005; Ribeiro, 1999; Schmitz, 1999).

Domestic earthworks are represented by pit houses. Althoughmany of them appear isolated or in small groups, some clustersof pit houses appear to constitute large, well-planned settlements,with the structures linked by a series of defined track-ways, indi-cating carefully controlled directions of movement at these sites(Iriarte et al., 2013). These settlements are also defined by artificiallow terraces on their downhill slopes (see alsoSaldanha, 2005). Inthe largest settlements, which can count up to 107 houses, thestructures are not randomly dispersed, but organized in discreteneighborhoods and accompanied by mounds. Clusters of houses

can have a linear or semi-circular layout, sometimes surroundinga mound (Schmitz et al., 2013b).

Most of the pit houses do not surpass 5 m diameter. However,some structures have diameters of up to 25 m and depths thatmay reach 7 m (Cop, 2006; Reis, 1980; Schmitz et al., 2010,2013a). These oversized pit houses in some instances appear aspart of clusters where they are surrounded by smaller pits, andoften are accompanied by large mounds (Cop, 2006; Kern et al.,1989; Schmitz et al., 1988). It is not yet clear whether oversizedpit houses represent habitations of extended families, high statusindividuals, or communal facilities similar to mens houses andkivas (Cop, 2006; Reis, 1980; Schmitz et al., 2010, 2013a).

Pit houses are only one type of southern proto-J site. They arecommon above 800 m of elevation (Beber, 2005; Panek Jr. and

Noelli, 2006), but in regions of lower altitudes settlements withoutearthen architecture are the norm. Sites with concentrations of

lithics and ceramics on the surface, accompanied by anthropogenicdark earth, are especially common in the southern escarpments ofthe Highlands (Miller, 1967), in Paran state (Chmyz et al., 1999;Parellada, 2004) and in the coast of Santa Catarina (Da Silvaet al., 1990).

Although it was long sustained that the southern proto-J peo-ples were mobile and depended more on hunting and gathering

than on horticulture, recent microbotanical studies have changedthat scenario. The consumption of manioc (Manihot esculentaCrantz), beans (Phaseolus sp.) and possibly yams (cf. Dioscoreasp.), in addition to maize (Zea maysL.) and squash (Cucurbitasp.),has recently been documented through phytolith and starch grainsanalysis from a pit house context (Corteletti et al., 2015). Theseresults confirmed that southern proto-J groups subsisted on avariety of cultivated plants, calling into question long-held modelshypothesizing that southern proto-J people where highly mobile.It also suggested that food production may have allowed popula-tions to settle in the southern Brazilianhighlands year-round with-out the need for seasonal movements to the lowlands to procurefood (Corteletti et al., 2015).

3.1.1. Mound and enclosure complexes

Although the southern proto-J groups were established in thesouthern Brazilian highlands since at least 2000 B.P., it was onlyin the last 1000 years that they began to create a distinctive rangeof monuments characterized by mound and enclosure complexes(Corteletti, 2012; Iriarte et al., 2008)(Fig. 1).

These sites are characterized by circular, elliptical, rectangular,and keyhole-shaped earthworks whose rims are 30100 cm tall,16 m wide, and 10180 m in diameter. They may exhibit or lackmounds and associated ringlets. Mounds are generally circularbut can be rectangular platforms (De Masi, 2009). In some regions,mound and enclosure complexes occur together in groups, forminga dense ceremonial landscape (Cop, 2007; Iriarte et al., 2013;Saldanha, 2005, 2008) (Fig. 2). Although they are preferably locatedon the top of prominent hills that today exhibit wide viewsheds,

these funerary and ceremonial structures can sometimes be foundin lower positions in the landscape (Corteletti, 2012; Cortelettiet al., 2015). In areas which have been intensely surveyed, moundand enclosure complexes form part of a highly structured land-scape, always found in the vicinity of pit house clusters, suggestingthat these funerary and ceremonial structures were associatedwith specific local groups (Cop, 2007; Iriarte et al., 2013;Saldanha, 2005, 2008).

As previously noted by other researchers working in the region(De Masi, 2009; De Souza and Cop, 2010), mound and enclosurecomplexes appear to be divided in two size categories. Smallerrings have a diameter ranging between 10 and 40 m, are far morenumerous, are generally arranged in pairs, exhibit low and narrowrims, and most of them contain a shallow central mound or a pair

of mounds. They exhibit a dual architecture arranged in a generalSWNE alignment, with larger structures located in the westernsection; these latter are alwayslocated in a slightly topographicallyhigher position than the smaller structure (Iriarte et al., 2013). Lar-ger rings, between 60 and 180 m diameter, are fewer and exhibithigher, wider and easily visible rims up to 1 m in height. Some ofthe large rings are more complex than a simple circular layout,including entry avenues and associated attached ringlets (Iriarteet al., 2008, 2010; Reis, 1980).

It has been suggested that those distinctions in size and archi-tecture might be related to different functions and scales of thosemonuments. Small mound and enclosure complexes have beeninterpreted as low-level integrative facilities (sensu Adler andWilshusen, 1990) built and visited by the inhabitants of nearby

pit house villages, where they undertook secondary inhumationsand participated in collective funerary rites, reinforcing commu-

198 J.G. De Souza et al. / Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 41 (2016) 196212

-

7/26/2019 Genesis of monuments CORTELETTI (1).pdf

4/17

nity ties (De Souza and Cop, 2010; Saldanha, 2005, 2008). In con-trast, it has been proposed that large enclosures were ceremonialcenters whose construction mobilized the labor of different com-munities dispersed across a region, and whose use was destinedfor a larger public to perform other ceremonies beyond burials,therefore constituting high-level integrative facilities (De Masi,2009; De Souza and Cop, 2010). In the case of keyhole-shaped

earthworks, detailed topographical survey and excavations havedemonstrated a move from circular to rectilinear architecturalforms by the additionof rectangular annexes, representing a move-ment toward more complex and diverse forms of architecture overtime (Iriarte et al., 2013).

A diversity of funerary practices is documented from the exca-vations of the central mounds of mound and enclosure complexes.

Fig. 1. Abreu & Garcia mound and enclosure complex, Campo Belo do Sul, Santa Catarina, Brazil, showing 2014 excavations.

Fig. 2. The densest ceremonial landscape of the highlands, Pinhal da Serra (Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil), with some examples of the architectural variability of mound andenclosure complexes. Based onIriarte et al. (2013).

J.G. De S ouza et al. / Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 41 (2016) 196212 199

http://-/?-http://-/?- -

7/26/2019 Genesis of monuments CORTELETTI (1).pdf

5/17

These practices include the cremation of single or multiple individ-uals within off-mound pyres, and subsequent redeposition of cre-mated bones within the mound structure (Cop and Saldanha,2002; De Masi, 2009; De Souza and Cop, 2010; Mller, 2008;Mller and Mendona de Souza, 2011). Small ceramic cups anddishes are usually found associated with the interments, possiblyrepresenting food and drink offerings.

Phytolith analysis fromcharred residues of ceramic sherds asso-ciated with earthovens at the base of the ring of site PM01 in Eldo-rado, Misiones, suggests that these ceramics were used to drinkmaize-based beverages during post-mortuary feasting ceremonies(Iriarte et al., 2008, 2010). Site PM 01 is the largest and most com-plex set of mound and enclosure earthworks so far recorded. A cen-tral mound, 20 m in diameter and 3 m high, faces a smaller mound(10 m diameter), and this pair of mounds is encircled by a 180 mdiameter ring, connected to a 400 m long entrance avenue framedby earthen banks. A further three ringlets (35130 m diameter)were attached to the main ring.Iriarte et al. (2008)interpret theearth ovens and evidences for drinking maize-based beverages atthe site as representing periodical post-mortuary festivals, epi-sodes of conspicuous consumption sponsored by the lineage ofthe chief buried in the central mound.

Data from mound and enclosure sites such as PM 01 have fig-ured in recent discussions about the social complexity of southernproto-J groups. Another example, in the state of Santa Catarina,Brazil, is site SC-AG-12, which contained a pair of rings 30 m and60 m in diameter (De Masi, 2009). The central mound of the largercircle contained the cremated burial of an adult and an infantaccompanied by offerings including ceramic vessels, lip plugs andceramic figurines, whereas the central mound of the smaller circlecontained six cremated burials, along with a few ceramics whichdid not appear to be associated with any specific individual. Inthe interior of the larger circle, facing the central mound, discretestone ovens were excavated. In summary, the two individualsinterred in the large circle received a more exclusive treatment,and were buried in a ceremonial space whose construction and

use probably involved a wider audience. The inner plaza was aspace for feasting, as evidenced by the numerous stone ovens thatfaced the central mound. It is possible that, similar to the site PM01, the plaza of the large ring at SC-AG-12 was the stage forregional-level ceremonies focused on the burials of the centralmound. Based on this evidence, De Masi (2009) argues that thetwo individuals buried in the mound of the larger ring had a highersocial status with regards to the six individuals buried collectivelyin the smaller ring.

Furthermore,Iriarte et al. (2013)point to a hierarchical ritualseparation of space in paired funerary structures, where usuallyone of the rings is larger, representing a dual ranked oppositionattested in the historic southern J moiety cemeteries (Crpeau,1994, 2002; Da Silva, 2001; Veiga, 2000). Historic cemeteries were

divided conceptually and spatially according to the moieties of theKaingang society: the dead of the Kam moiety were buried inhigher topographic positions, and those of the Kainrumoiety wereinterred in lower elevations. Interestingly, the eastwest divisionthat permeates the Kaingang moiety system is in this case replacedby a distinction between upper and lower places, mirroring theasymmetrical relationship that has been noted to underlie the moi-ety division, as the Kam are considered superior in the spiritualplan (Crpeau, 1994, 2002). The close proximity of the funerarymound and enclosure complexes to specific settlements, the evi-dences of differential treatment of the dead, the hierarchical struc-ture of space and the reduced number of individuals buried inthose structures lead us to followIriarte et al. (2013)in interpret-ing them as cemeteries for important persona of each moiety,

where potential leaders were incorporated into the landscapeand transformed into ancestors.

The mortuary and ceremonial practices at the mound andenclosure complexes are one of the domains where the connectionbetween archaeology and ethnography are clearer. In fact, thesouthern Brazilian highlands is one of the few regions in the Amer-icas where mortuary rituals associated with mound-building havebeen recorded in early European accounts during the 17th19thcenturies and investigated by ethnographers during the 20th cen-

tury (e.g. Baldus, 1937; Becker, 1976; Crpeau, 1994; De Paula,1924; Henry, 1941; Maniser, 1930; Mtraux, 1946; Veiga, 2006).Historical southern J groups exhibited a dual social organizationcharacterized by exogamic, patrilineal moieties. As mentioned inthe previous paragraph, in the case of the Kaingang, the moietiesare complementary, but also asymmetrical, and the ethnohistoricrecords suggest the presence of sizeable, regionally organized,hierarchical polities (e.g.Crpeau, 1994; Fernandes, 2004). Impor-tantly, funerary and post-funerary rituals are reported to be theirsingle most important ceremony when the entire tribe gatheredtogether showing their dual organization. These events includedthe burial of important chiefs, secondary burials, the inheritanceof the chiefly office by the eldest son of the deceased chief, initia-tion rites, name-giving ceremonies, performance and re-creation ofthe cosmogony myth, and feasting (e.g. Da Silva, 2001; Iriarte et al.,2013, 2008; Maniser, 1930; Mtraux, 1946; Veiga, 2006). Despitethe fact that the mound and enclosure complexes from the firsthalf of the second millennium A.D. and the circumstances in whichthey arose are very different from the ones reported during the17th20th centuries, there appears to be many subjacent struc-tures that endured during historic times associated with the asym-metrical dual organization of these societies, the spatialsegregation of ritual space, and the alignment of burial moundsand enclosures (seeIriarte et al., 2013for more details).

3.2. The Tupi-Guarani

At the same time that the southern Brazilian highlands were

settled by the southern proto-J groups, a different traditionstarted colonizing the low altitude, warm subtropical forests alongthe major rivers of the Rio de la Plata basin. These are the Tupi-Guarani groups, and their expansion along some 5000 km of theAtlantic coast and through the major rivers in the hinterland dur-ing the last 2000 years represents one of the major populationexpansion processes of lowland South America (Bonomo et al.,2015; Brochado, 1984; Noelli, 1998).

Archaeologists refer to the material correlates of the Tupi-Guarani groups by the name of Tupiguarani Tradition (withoutthe hyphen). This tradition was originally defined by a packageof co-occurring traits which included polychrome (red and/or blackon white and/or red slip), corrugated and brushed pottery, thepractice of secondary burials in urns, polished stone axes, and

the use of lip plugs (Brochado et al., 1969; Chmyz, 1976; Prous,1992).

Ethnographic and ethnohistorical data show that the Tupi-Guarani lived in large palisade villages composed of manyextended family longhouses. Colonial sources and a few publishedsite plans suggest the longhouses were disposed around an openplaza which, amongst other functions, served as a funerary area(Noelli, 1993). Larger confederacies of villages were recorded inthe historical period, which could have attained up to 40 allied vil-lages under the influence of a prominent political or spiritual lea-der (Milheira and DeBlasis, 2014; Noelli, 1993). War, motivatedby frontier expansion or revenge, as well as the subsequent ritualanthropophagic feasts, had a large social significance as a meansof status acquisition (Milheira and DeBlasis, 2014). Anthro-

pophagic feasts were described in numerous colonial sources,and a state of endemic warfare and strong warrior ideology

200 J.G. De Souza et al. / Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 41 (2016) 196212

-

7/26/2019 Genesis of monuments CORTELETTI (1).pdf

6/17

persisted among modern Tupi-Guarani tribes (Fausto, 2012;Viveiros de Castro, 1992).

Interestingly, the anthropophagic rituals so intimately con-nected to the warfare ideology attested in the historical recordshave recently been assessed by stylistic analyses of Tupiguaranipottery. Prous (2005, 2010) observes that elaborate polychromepainting was primarily associated with ritual contexts, such as

the vessels for fermenting beverages for drinking during theanthropophagic feast and possibly vessels for serving the sacrificedenemys flesh. He argues that many of the geometrical designs onthese vessels are stylized representations of human faces, bodies,bones and entrails (Prous, 2005, 2010). Similarly, the designs onelaborate polychrome pottery in funerary contexts from Rio deJaneiro have been interpreted as stylized representations of skele-tal or visceral patterns (Buarque, 2010).

Since the seminal work ofBrochado (1984), all authors agreethat the Tupi-Guarani advance throughout the South Americanlowlands represents a process of expansion rather than a migrationin the strict sense, that is, new daughter villages branched out ofoverpopulated old ones, but maintained interaction and social tieswith them in such a way that old territories were never aban-doned. This process resulted in an expanding radius of village net-works through gradual population waves (Bonomo et al., 2015;Brochado, 1984; Milheira and DeBlasis, 2014; Noelli, 1993). Majorwaterways were the primary corridors for the Tupi-Guarani expan-sion, and nearly all their sites are located along rivers. Followingthis argument, Noelli (1993) proposed that the initial Tupi-Guarani advance was restricted to the major forested river flood-plains. After the consolidation of their territories and associatedmanaged forest areas in these preferred environments, theTupi-Guarani would start colonizing smaller tributaries with gal-lery forests. In general, this model has been recently confirmedby the latest review of Tupi-Guarani dates in the Rio de la Platabasin byBonomo et al. (2015). This process has been observed inmore detail byRibeiro (1991)in the Pardo River valley, Rio Grandedo Sul. In his study, he showed how the earliest and larger sites

occupy the fertile floodplain, whereas the latest sites are smallerand located in higher elevation zones.

Several authors have envisioned the typical Tupi-Guarani set-tlement pattern as consisting of concentric circles radiating outfrom the village (located close to a permanent water source)and extending into home gardens, slash-and-burn plots, the for-est, and other villages linked by roads (Assis, 1995; Milheiraand DeBlasis, 2014; Noelli, 1993). Noelli (1993) proposes thatthe catchment area of a village or cluster of dispersed home-steads could reach 50 km radius. As indicated by recentpalaeobotanical research, the forest around Tupi-Guarani settle-ments was likely secondary forest resulting from managed oldfallows in different states of succession (Scheel-Ybert et al.,2014).

Historically recorded Tupi-Guarani groups were tropical horti-culturalists that practiced agroforestry polyculture. They slashedthe forest with stone axes and managed old fallows (Brochado,1984; Noelli, 1993). Nearly all of the cultivated products wereof tropical origin, including manioc (Manihot esculenta), peanuts(Arachis hypogea), beans (Phaseolus sp.), potato (Solanum tubero-sum), yam (Dioscorea sp.), sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas), maize(Zea mays) and squashes (Cucurbita spp.). Maize pollen has beendocumented in regions located in the vicinity of Tupi-Guaranisites since ca. 1810 B.P. (Behling et al., 2005, 2007). In theParan Delta, stable isotope analysis by Loponte and Acosta(2007, 2013) demonstrates that skeletons from Tupi-Guaraniburial contexts had an enriched average d13C content in compar-ison with skeletons from hunter-gatherer sites from the same

region, confirming the consumption of maize by the Tupi-Guarani.

3.3. The impact of the Tupi-Guarani expansion

For a long time it was thought that the arrival of the Tupi-Guarani to the south, bringing with them tropical cultigens andthe practice of slash-and-burn agriculture from their homelandin SW Amazon, would have triggered a Neolithization process thatled to the adoption of agriculture by local foragers (Otonello and

Lorandi, 1987; Rodrguez, 1992; Schmitz, 1991; Schmitz andBecker, 1991; Schmitz et al., 1991).We now know that cultivated plants were available to the

groups of the Rio de la Plata basin long before the Tupi-Guaranisettled in the area (e.g.Iriarte, 2006; Iriarte et al., 2004). Further-more, plants such as manioc (Shock et al., 2013) and maize(Prous et al., 1991; Resende and Prous, 1991) were present in Cen-tral Brazil since at least 4000 B.P., and therefore must have beenavailable to the proto-J groups before they started their expansionto the south.

However, although agricultural practices were not unknownbefore their arrival, the Tupi-Guarani expansion does mark thewidespread adoption of agriculture in southeastern South America,bringing with them 13 varieties of maize, 15 varieties of beans, 21varieties of sweet potato, among many other cultivated plants(Noelli, 1993).

The pace of expansion of the Tupi-Guarani is also worthy ofnotice: based on the dates available for southern Brazil and the dis-tances involved,Rogge (2005)calculates an expansion rate of 0.81 km per year, which he considers similar to that of the Neolithic inEurope and tentatively associates with a wave-of-advance model(sensu Ammerman and Cavalli-Sforza, 2014). Recently, Bonomoet al. (2015) have suggested varying paces of expansion in differentperiods: (1) a rapid spread of 750 km2 from0 to 300 A.D., (2) a per-iod of territorial stabilization with a slower dispersion of 110 km2

per year from 300 to 1000 A.D., and (3) a rapid new wave of expan-sion of 500 km2 per year after 1000 A.D. It is estimated that, by thetime of the European contact, the Tupi-Guarani speakers num-bered around 4 million (Rodrigues, 1986). The demographic conse-

quences of this process of expansion must be taken into account.

3.4. Dealing with outsiders: interaction and resistance

Conflict with pre-established populations was long postulatedas a major consequence of the Tupi-Guarani territorial expansion(Brochado, 1984; Noelli, 1993). Archaeologists working in southernBrazil and surrounding areas have recognized that the rapid Tupi-Guarani spread led to the progressive circumscription of localgroups for example, pushing and restricting the southernproto-J groups to the upper elevations of the highlands (Noelli,1999b, 2004). In the southernmost limits of the Tupi-Guaraniexpansion, the Paran River delta, Loponte (2008) concluded thatthe Tupi-Guarani arrival circumscribed local hunter-gatherer

groups, leading to a period of increased competition and emer-gence of more complex forms of political organization amongthem. Interestingly, nearly 3500 km north, in the central Amazon,the arrival of polychrome pottery, interpreted by many Amazonianarchaeologists as representing the advance of Tupi-Guarani speak-ers (Brochado, 1984; Neves, 2010; Rebellato and Woods, 2012),marks a period of destabilization of local groups and intensifiedconflict visible in the construction of defensive structures andrapid abandonment of pre-existing settlements (Moraes andNeves, 2012).

In fact, many traditional models adhere to the idea that theTupi-Guarani would have rapidly advanced over forested areasalong rivers, easily conquering new territories and expelling previ-ously settled groups (Brochado, 1984; Noelli, 1993). Another

assumption that is frequently made is that Tupi-Guarani groupswere adapted to a specific ecological niche, preventing, or at least

J.G. De S ouza et al. / Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 41 (2016) 196212 201

-

7/26/2019 Genesis of monuments CORTELETTI (1).pdf

7/17

discouraging them from expanding to environments where forestfarming was not viable (Rogge, 1996, 2005; Schmitz, 1991).

It is undeniable that the Tupi-Guarani expansion was rapid andthat forested river floodplains were by far their preferred environ-ment. However, the intricacies of the process of colonizing newareas and interacting with local groups were more complex thana simple ecological niche model would lead us to believe. For

example, in the only recent synthesis about prehistoric interac-tions in southern Brazil, Rogge (2005)makes the important pointthat warfare and the creation of impermeable frontiers (a strategyof perimeter defense sensuCashdan, 1983) were important onlyduring the initial stages of Tupi-Guarani expansion into the majorriver valleys. As population grew and was pushed out of the sub-tropical deciduous forest toward less favored environments, suchas the borders with Araucariaforest occupied by southern proto-J groups, the violent strategy of warfare became too risky andcostly, since these areas were densely occupied by rival groups.Instead,Rogge (2005)argues that later expansions into those envi-ronments would have established a permeable social frontier(sensuDennell, 1985). The circulation of objects, individuals andinformation across the frontier would have facilitated access tovarious ecological niches both by the Tupi-Guarani and by the pre-viously established groups.

Archaeological evidences of such flux of people and informationabound. In many parts of the escarpment of the southern Brazilianhighlands, in zones of transition between subtropical deciduousforests and the Araucaria forest, the Tupi-Guarani actively inter-acted with southern proto-J groups. This is evidenced by the pres-ence of intrusive Tupi-Guarani ceramics in southern proto-J sites,sometimes forming true enclaves, suggesting that entire house-holds of Tupi-Guarani origin were living side by side with southernproto-J groups in the same village (De Masi and Artusi, 1985;Ribeiro, 1991; Rogge, 2005; Schmitz et al., 1987).

This situation has been noticed in the Uruguay River, aroundthecity of Itapiranga, Santa Catarina state. The settlement patterns forthe two traditions were very distinctive: whereas the Tupi-Guarani

occupied the river floodplain, the southern proto-J were estab-lished in upper elevation zones (Piazza, 1969). The contactbetween them was evidenced by the juxtaposition of residentialunits of both traditions in the same settlement, although no mixingof ceramic styles occurred (De Masi and Artusi, 1985; Schmitz andBecker, 1968). Interestingly, the influence seems to have been uni-directional, with Tupi-Guarani households moving to southernproto-J villages, but never the other way around (De Masi andArtusi, 1985). There are no absolute dates for the sites in question,but it is estimated that the contact would have occurred betweenA.D. 1000 and 1200 based on the ceramic relative chronologies.

In the Pardo River basin, Rio Grande do Sul state,Ribeiro (1991)and Schmitz et al. (1987) observed a similar situation. IntrusiveTupi-Guarani ceramics formed enclaves in southern proto-J sites,

interpreted as foreign households, but in this case there was somemixing of ceramic styles.Schmitz et al. (1987)believe this to beevidence of intentional, structured contact between the two peo-ples, not of occasional interactions. Again, the influence was unidi-rectional, with Taquara/Itarar ceramics adopting shapes anddecorationsinspired in the Tupiguarani Tradition, but not the otherway around (Ribeiro, 1991). The contact was estimated to haveoccurred after A.D. 1000.

In the Paranapanema valley, Paran state,Chmyz (1971)founda somewhat diverse scenario: not only were the southern proto-Jgroups occupying the same riverine environment as the Tupi-Guarani, but the ceramics of the first were found in the sites ofthe later, showing a reverse direction of influence from the previ-ous cases. Chmyz (1971) also observed evidences of interaction

in the Upper Iguazu River, Paran state, and the coast of SantaCatarina, where Taquara/Itarar vessels, though maintaining the

typical shapes of the tradition, had paste and decoration identicalto the Tupiguarani ones. More recently, Volcov (2011) demon-strated an inverse situationin the Upper Iguazu where Tupiguaraniceramic assemblages incorporate typical Taquara/Itarar shapes.He believes that women of southern proto-J origin played the roleof intermediates, through marriage, during the contact with theTupi-Guarani. These women would have moved to the newcomers

villages, but continued to manufacture their traditional ceramics,although adopting some stylistic attributes from the Tupi-Guarani.Cop (2006)has observed a similar situation in Bom Jesus, Rio

Grande do Sul state, where Tupiguarani vessels were found insidesouthern proto-J pit houses. In order to ascertain the provenanceof those ceramics,Cop (2006)performed X-ray diffraction analy-sis, concluding that both the Tupiguarani and the Taquara/Itararvessels were manufactured from the same clay sources that arewidespread around the site. She believes the Tupiguarani ceramicsoriginally came to the highlands as containers for productsexchanged between the Tupi-Guarani and the southern proto-Jgroups, and the styles were eventually adopted by the later dueto the superiority of their forms for storage and transportation.Cop (2006)does not believe that Tupi-Guarani women would beliving in pit house sites, otherwise a greater diversity of Tupiguar-ani vessels would have been produced, whereas only storage ves-sels were found. She suggests that the Tupiguarani ceramics inthe highland pit house sites would constitute prestige artefactsand would only appear in some special sites perhaps upper statusdwellings, or hubs in an exchange network.

Similarly, Tupiguarani ceramics have been found inside pithouses and in other southern proto-J contexts in Caxias do Sul,Rio Grande do Sul, closer to the escarpment of the highlands(Corteletti, 2008; Schmitz et al., 1988). In this region, besides theceramic vessels, an isolated Tupiguarani urn burial has been iden-tified. The burial was that of an infant, and was located close to theCa River, which naturally connects the highlands with the low-lands.Corteletti (2008)suggests the child could have died duringa Tupi-Guarani incursion into the J hinterland.

Finally, in the northern coast of Rio Grande do Sul, where sitesof the two traditions appear to be smaller and represent ephemeraloccupations,Rogge (2005) finds evidence of contact only in the lar-gest settlements. These are located in intermediate areas betweenthe forest, freshwater lagoons and the sea, providing access to avariety of resources. Although he finds no evidence of mixed cera-mic styles, Rogge (2005) suggests, based on the recent dates for theregion, that the Tupi-Guarani and the southern proto-J werealready in contact in the hinterland before they moved to the coastwhere they would only make seasonal incursions.

Rogge (2005)believes that, after colonizing the lowland fertilefloodplains, the Tupi-Guarani would have sought to complementtheir economy with the exploitation of upland areas of Araucariaforest but these were under the domain of the southern proto-

J. FollowingCashdan (1983) and Dennell (1985), he argues that,instead of promoting a perimeter-defense strategy and establish-ing impermeable frontiers, in such a situation it would be ofmutual benefit to both groups to adopt a social frontier defensestrategy, i.e. controlling the circulation of individuals and informa-tion across a permeable social border. This would ensure access tothe same resources for individuals of both traditions, as the Tupi-Guarani would be able to exploit the uplands and the southernproto-J would not be deprived of the floodplain forest resources.

However, an ecological explanation is insufficient to account forall the cases where interaction or resistance have been docu-mented. Although the Tupi-Guarani preferably settled in low alti-tude subtropical warm forests, this was not the onlyenvironment where they were established. Tupiguarani sites occur

frequently in high altitudes of the plateau of Paran state in aregion of grasslands and mixed forests that were also densely

202 J.G. De Souza et al. / Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 41 (2016) 196212

-

7/26/2019 Genesis of monuments CORTELETTI (1).pdf

8/17

inhabited by southern proto-J groups (Volcov, 2011). From ethno-historical accounts, we know that the Tupi-Guarani groups livingin the proximities of the southern Brazilian highlands wereexploiting resources of that environment, such as the Araucariapine seeds (Noelli, 1993). Therefore, the higher altitudes and mixedforests do not seem to have represented a barrier per se for theTupi-Guarani expansion.

At the same time, some areas of low altitude deciduous forestsalong large rivers, such as the lower Iguazu in the state of Paran,are virtually devoid of Tupiguarani sites (Chmyz, 1981; Parellada,2005) even though sites are found further down or upstream. Webelieve that other reasons, of a social and political nature, weremore important in influencing which areas were going to be settledby the new wave of migrants. Of prime concern must have beenhow densely populated was an area by the previously establishedgroups, how territorial these groups were, and how willing werethey to interact peacefully. Our hypothesis is that, in some partsof the southern Brazilian highlands, the Tupi-Guarani could notadvance over southern proto-J territory because the local groupschose to resist the outsiders and to establish a perimeter defensestrategy. However, beyond the absence of evidence, i.e. the lackof Tupi-Guarani sites, ceramics or influence in ceramic styles, isthere any positive evidence of the establishment of impermeablefrontiers by the southern proto-J groups?

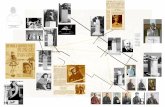

Given the potential of monuments to act as overt territorialmarkers (OShea and Milner, 2002) and as a form of smart adver-tising to warn outsiders (Ames, 2010; Boone, 2000; Neiman,1997), we hypothesize that the areas where southern proto-Jgroups established impermeable social borders and chose a strat-egy of perimeter defense against the invading Tupi-Guarani groupscould potentially be recognized by an increase in the constructionof mound and enclosure complexes. To test this hypothesis, wegathered spatial and chronological data for all mound and enclo-sure complexes and compared them with areas where interactionis documented to have taken place between southern proto-J andTupi-Guarani groups (Fig. 3).

4. Methods and results

4.1. Spatial analysis

We compiled spatial information for two distinct datasets: (i)mound and enclosure complexes, totaling 52 sites (Table 1), and(ii) locations with documented interaction between southernproto-J and Tupi-Guarani groups, totaling 42 sites (Table 2).The data were compiled from published papers, as well as unpub-lished reports, dissertations and site record files, to which weadded information from our field work in Campo Belo do Sul,Santa Catarina state. To test the hypothesis that the establish-

ment of monumental landscapes by the southern proto-J groupswas a form of resisting the outsiders through an overt demarca-tion of territories, we followed the methodology proposed byWinter-Livneh et al. (2012)in order to compare the two datasets.We produced kernel density maps for mound and enclosure com-plexes and for interaction sites using different search radii. Giventhe area of these datasets, comprising all of southern Brazil andits adjacencies (400,000 km2), and the average distance betweenthe sites, the search radii were rather large (20, 30 and 40 km).The density maps were then sampled with grids of different cellsizes 20 20, 30 30 and 40 40 km to obtain a mean den-sity of each site type through zonal statistics (Fig. 4). Finally, acorrelation test was performed on these results after the exclu-sion of cells with zero value for both datasets (i.e. areas devoid

of sites). All the analyses were performed with ArcGIS 10.2 andIBM SPSS 22.

As can be seen inTable 3, the density maps produced with var-ious search radii and the distinct cell sizes of the sampling grids allresulted in significant negative correlation coefficients for the twodatasets. Larger search radii and cell sizes tend to produce weakercorrelations due to the more generalized nature of these maps, butthe results are still significant. The results support the conclusionthat highly monumentalized landscapes emerged in locations

where the southern proto-J established impermeable boundariesand chose not to maintain contact with foreign groups. Similarly,in areas of intense exchange between Tupi-Guarani and southernproto-J groups, monumental burial sites did not form a part ofthe social landscape.

4.2. Chronology

We compiled all the radiocarbon dates for southern proto-Jmound and enclosure complexes from published sources, unpub-lished reports and dissertations, in addition to dates from ourown fieldwork, totaling 32 dates for 16 sites (Table 4).

The examinationof the chronology shows that the earliest datesfor the southern proto-J mound and enclosure complexes come

from the basins of the Canoas and the Pelotas Rivers in the borderbetween the states of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul. Thesetwo rivers join to form the Uruguay River, and the earliest moundand enclosure complexes are located very close to this confluencezone.

If the geographical origin of mound and enclosure complexes isto be found near the confluence of the Canoas and Pelotas Rivers,we can hypothesize that their emergence was specifically relatedto Tupi-Guarani incursions toward that area. To test this hypothe-sis, we compared the chronology of mound and enclosure com-plexes in the CanoasPelotas basin with recent publishedsyntheses of the Tupi-Guarani dated sites (Bonomo et al., 2015).

Although the Tupi-Guarani were established in the Rio de laPlata basin since at least ca. 2000 years B.P., they were mostly

restricted to the larger rivers such as the Paran and the Paraguay.The available dates showthat only after ca. A.D. 1000 they began tomove up the Uruguay River into the southern proto-J heartland(Bonomo et al., 2015). This date precisely coincides with themoment when the first mound and enclosure complexes startedto be built. The earliest Tupiguarani site in the Upper Uruguay isdated 1070 100 B.P., Cal A.D. 7701215, contemporary with theearliest southern proto-J mound and enclosure complex, dated1070 40 B.P., Cal A.D. 8951150.Table 5shows the dates of Tupi-guarani sites in the upper course of the Uruguay River.Fig. 5 showsthe range of calibrated dates for the southern proto-J mound andenclosure complexes in the CanoasPelotas region, compared tothe dates for Tupiguarani sites in the Upper Uruguay. The coinci-dence between the appearance of the earliest mound and enclo-sure complexes and the first incursions of the Tupi-Guarani inthe upper course of the Uruguay River is remarkable.

5. Discussion

Our analysis shows that the emergence of a new form of archi-tecture among the southern proto-J groups, represented by thefunerary mound and enclosure complexes, must be understoodwithin the context of wider population displacements, ethnic con-tacts, and the forging of new identities in the south of Brazil and itsadjacencies during the last 1000 years. We propose that a highlymonumentalized landscape was built as a response to the Tupi-Guarani expansion into the southern Brazilian highlands, by localgroups who chose to establish an impermeable frontier against

the outsiders, and assertively demarcated their territories throughthe proliferation of funerary earthworks.

J.G. De S ouza et al. / Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 41 (2016) 196212 203

http://-/?-http://-/?- -

7/26/2019 Genesis of monuments CORTELETTI (1).pdf

9/17

As the results of the spatial analysis demonstrate, the highestdensity of funerary mound and enclosure complexes occurs inareas that are devoid of interaction between southern proto-Jand Tupi-Guarani groups, namely the basin of the Canoas and Pelo-tas rivers to the east of the confluence where these two rivers meetto form the Uruguay River (Fig. 6). The Uruguay River, bordered byfertile deciduous forest floodplains and navigable along most of itscourse, was a major waterway for the Tupi-Guarani incursions intothe highlands, but their expansion stopped at the confluence zone.We argue that the confluence represented an ultimate frontier thatthe Tupi-Guarani did not dare to cross, not because of an ecologicalbarrier, but due to the resistance imposed by southern proto-J

groups living beyond that border.

But why would those groups impose such a resistance insteadof establishing exchange relationships with the outsiders as didtheir western neighbors? There is mounting evidence that, unlikethe groups living downstream, those established upstream fromthe CanoasPelotas confluence constituted regionally organized,sedentary, highly territorial polities, as evidenced by the sitesdimensions, architectural complexity and settlement patterns inthis region (Iriarte et al., 2013; Schmitz et al., 2013a, 2013b). Someof the earliest dates for dense pit house villages, attaining the 7thcentury A.D., come from this area, pointing to a long history ofsouthern proto-J developments (Schmitz and Rogge, 2011). Itcomes as no surprise that it is in this core area for the southern

proto-J groups that we find the densest concentrations of mound

Fig. 3. Areas occupied by the southern proto-J and Tupi-Guarani, with the location of mound and enclosure complexes and sites with documented interaction between thetwo traditions as discussed in the text.

204 J.G. De Souza et al. / Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 41 (2016) 196212

-

7/26/2019 Genesis of monuments CORTELETTI (1).pdf

10/17

and enclosure complexes with the most elaborate architecture andthe earliest dates. Last, but not least, we would like to call attentionto the fact that river confluences were important stages for novelcultural developments, multi-ethnic social formations, and theforging of new identities across the globe and throughout prehis-tory (Bernardini, 2004; Bradley, 1998, 2000; Pauketat, 2007;Ruby et al., 2005).

We argue that the rapid expansion of the Tupi-Guarani alongthe upper course of the Uruguay River after a millennium of sta-sis in its lower course was an event of major consequences forthe southern proto-J groups established to the east of the conflu-

ence zone. The dates of Tupi-Guarani sites show a rapid pace ofexpansion along the Upper Uruguay: by 1070 100 B.P. (Cal A.D.

7701215) they began their expansion upstream, settling aroundthe modern municipality of Itapiranga, where extensive exchangeof individuals, objects and information occurred with the pre-established southern proto-J groups. By 900 50 B.P. (Cal A.D.10451220), the Tupi-Guarani were already settled less than30 km from the confluence of the Canoas and Pelotas rivers. Usingthe median of the dates as a proxy, we can estimate that the Tupi-Guarani expansion along the Upper Uruguay occurred at a rate of

1 km per year. The southern proto-J groups established upstreamfrom the confluence that forms the Uruguay River might have per-ceived such a wave of advance as potentially threatening, andchose not to interact with the outsiders, unlike their downstreamneighbors. We suggest that, in this agitated social scenario, a crisiscult (La Barre, 1971) emerged focused on the burial rites of moietyleaders, and having as its material correlate the new ceremonialapparatus represented by funerary mound and enclosure com-plexes. At the same time, the cremation rites, funerary and post-funerary feasting events, and unprecedented collective effortinvolved in the raising of the monuments can also be interpretedas forms of lavish displays that signaled the capacity of labor mobi-lization of the local groups to the outsiders (Ames, 2010; Boone,2000; Neiman, 1997). Borrowing the words of Tom Dillehay

(1992), we can say that mound and enclosure complexes sent apowerful message to keep outsiders out.

Table 1

Southern proto-J Mound and enclosure complexes recorded to the present.

Site name State Long Lat Reference

Abdon Batista 1 SC 51.137 27.548 This workAbdon Batista 2 SC 51.048 27.577 This workAbreu & Garcia SC 50.742 27.670 This workAndre daRocha 1 RS 51.574 28.630 Beber (2005)Bom Retiro 11 SC 49.488 27.799 Rohr (1971)

Bom Retiro 14 SC 49.488 27.799 Rohr (1971)Bom Retiro 7 SC 49.488 27.799 Rohr (1971)Bom Sucesso SC 49.777 28.061 Rohr (1971)Campo Belo 1 SC 50.820 27.671 This workCampo Belo 2 SC 50.803 27.734 This workCarneiro 2 RS 51.160 27.828 Iriarte et al. (2013)Duarte 2 RS 51.138 27.838 Iriarte et al. (2013)Ernani Garcia SC 50.758 27.671 This workFidencio RS 51.158 27.855 Iriarte et al. (2013)Gine RS 51.165 27.829 Iriarte et al. (2013)Lino SC 50.777 27.711 This workPetrolandia 2 SC 49.698 27.534 Rohr (1971)Pinhal da Serra 1 RS 51.312 27.773 Ribeiro and Ribeiro (1985)PM01 MIS 54.596 26.358 Iriarte et al. (2008)Posto Fiscal RS 51.185 27.834 Iriarte et al. (2013)PR UV 11 PR 51.631 26.110 Chmyz (1968)Reni Camargo SC 50.752 27.737 This work

Riacho 6 SC

49.585

28.020 Corteletti (2012)RS-PE-21 RS 51.179 27.823 Cop et al. (2002)RS-PE-29 RS 51.191 27.830 De Souza and Cop (2010)RS-PE-31 RS 51.178 27.843 Ribeiro and Ribeiro (1985)SC-AB-96 SC 51.049 27.632 De Masi (2005)SC-AG-100 SC 51.180 27.762 Mller (2008)SC-AG-108 SC 51.118 27.717 Mller (2008)SC-AG-112 SC 51.111 27.696 Herberts and Mller

(2007)SC-AG-114 SC 51.109 27.717 Herberts and Mller

(2007)SC-AG-116 SC 51.119 27.706 Herberts and Mller

(2007)SC-AG-12 SC 51.023 27.662 De Masi (2005)SC-AG-75 SC 51.066 27.660 De Masi (2005)SC-AG-77 SC 51.086 27.638 De Masi (2005)SC-AG-95 SC 51.174 27.768 Mller (2008)SC-AG-98 SC 51.179 27.761 Mller (2008)

SC-AG-99 SC 51.169 27.761 Mller (2008)SC-CL-37 SC 50.388 27.471 Reis (1980)SC-CL-74 SC 50.643 27.565 Beber (2013)SC-CL-88 SC 50.684 27.499 Beber (2013)SC-CL-9 SC 50.103 27.858 Reis (1980)SC-CL-94 SC 50.591 27.645 Schmitz et al. (2010)SC-CL-95 SC 50.709 27.475 Beber (2013)SC-CR-06 SC 51.206 27.643 De Masi (2005)SC-UP-414 SC 51.005 27.412 Naue et al. (1989)SC-UP-441 SC 51.126 27.650 Naue et al. (1989)SC-UP-446 SC 51.019 27.843 Naue et al. (1989)SP-IP-8 SP 49.606 23.266 Chmyz (1969)Urubici 21 SC 49.577 27.990 Corteletti (2012)Usina Velha SC 51.168 27.539 Rohr (1981)Warmeling 2 SC 49.514 28.019 Corteletti (2012)

Abbreviations: RS = Rio Grande do Sul; SC = Santa Catarina; PR = Paran; SP = So

Paulo; MIS = Misiones, Argentina.

Table 2

Sites with evidence of interaction between Tupi-Guarani and southern proto-J

groups.

Site name State Long Lat Reference

BAM-06 RS 49.792 29.321 Wagner (2004)Cambar Phase PR 50.018 22.992 Chmyz (1971)Cambar Phase PR 49.759 23.483 Chmyz (1971)Cambar Phase PR 51.840 23.702 Chmyz (1971)

Cambar Phase PR 50.213 22.953 Chmyz (1971)Cambar Phase PR 50.526 22.939 Chmyz (1971)Condor Phase PR 53.126 23.383 Chmyz (1971)Condor Phase PR 52.765 23.444 Chmyz (1971)Condor Phase PR 52.595 23.309 Chmyz (1971)Condor Phase PR 52.774 23.279 Chmyz (1971)Itapiranga Phase SC 53.724 27.123 De Masi and Artusi (1985)Itapiranga Phase SC 53.698 27.115 De Masi and Artusi (1985)Itapiranga Phase SC 53.669 27.119 De Masi and Artusi (1985)Itapiranga Phase SC 53.619 27.120 De Masi and Artusi (1985)Itapiranga Phase SC 53.601 27.138 De Masi and Artusi (1985)LAA-01 RS 50.239 29.834 Wagner (2004)LII-04 RS 49.927 29.461 Wagner (2004)LII-07 RS 49.806 29.399 Wagner (2004)LLE-02 RS 50.227 29.869 Wagner (2004)LQQ-01 RS 50.171 29.740 Wagner (2004)Praia da Tapera SC 48.570 27.688 Da Silva et al. (1990)

PR-CT-08 PR

50.088

25.525 Volcov (2011)PR-CT-23 PR 50.038 25.567 Volcov (2011)PR-CT-29 PR 50.033 25.541 Volcov (2011)Rio Pardo 01 RS 52.540 29.760 Ribeiro (1991)Rio Pardo 06 RS 52.676 29.560 Ribeiro (1991)Rio Pardo 11 RS 52.646 29.556 Ribeiro (1991)Rio Pardo 14 RS 52.568 29.489 Ribeiro (1991)Rio Pardo 20 RS 52.538 29.484 Ribeiro (1991)Rio Pardo 23 RS 52.507 29.318 Ribeiro (1991)Rio Pardo 25 RS 52.476 29.303 Ribeiro (1991)Rio Pardo 47 RS 52.522 29.408 Ribeiro (1991)Rio Pardo 55 RS 52.553 29.637 Ribeiro (1991)RS-37/127 RS 50.995 29.207 Schmitz et al. (1988)RS-AN-03 RS 50.424 28.673 Cop (2006)RS-LC-80 RS 50.330 30.383 Rogge (2005)RS-LC-81 RS 50.332 30.383 Rogge (2005)RS-LC-82 RS 50.335 30.388 Rogge (2005)RS-LN-16 RS 50.221 29.921 Wagner (2004)

RS-LN-295 RS 49.840 29.466 Rogge and Schmitz (2010)Tamboara Phase PR 51.389 23.909 Chmyz (1971)Xaxim Phase SC 51.958 27.352 Piazza (1969)

Abbreviations: RS = Rio Grande do Sul; SC = Santa Catarina; PR = Paran; SP = SoPaulo; MIS = Misiones, Argentina.

J.G. De S ouza et al. / Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 41 (2016) 196212 205

http://-/?- -

7/26/2019 Genesis of monuments CORTELETTI (1).pdf

11/17

Let us now examine the internal consequences for the southernproto-J political organization. Given the compelling evidence thatmound and enclosure complexes represent cemeteries for moietyleaders (De Masi, 2009; Iriarteet al., 2013), webelieve that the pro-liferation of those monuments at the turn of the second millen-nium A.D. also represented the materialization of new forms ofauthority inscribed in a political landscape (Dillehay, 2007;Pauketat, 2007; Smith, 2003). In other words, we believe that theconsolidation of hereditary leadership occurred, among other fac-tors, as an unforeseen consequence of new strategies designed to

repel the Tupi-Guarani invaders. Prospective leaders would havefound the opportunity to further accumulate authority in the mil-itary and religious spheres of power (Earle, 1991, 1997; Yoffee,1993) by leading warfare against the outsiders and by having theirancestors celebrated in the new ceremonial apparatus of themound and enclosure complexes. Intensifying conflict might havereinforced the power of war leaders, but it is the new monumentalfunerary architecture and burial rituals that, we argue, emergedas part of a crisis cult amidst the Tupi-Guarani advance thatwould have provided them with the supernatural legitimation ofpower that is such a fundamental component of the transition toinstitutionalized inequality, and that many prospective leaders failto achieve (Aldenderfer, 2010).

This interpretation finds support in the numerous information

about the southern J chiefdoms described in historical accounts

(Becker, 1976; Fernandes, 2004; Mabilde, 1897, 1899;Tommasino, 1995), and sheds light on many of the features ofthe historical chiefdoms. Particularly in the case of the Kaingang,mounds were an important component of the political landscape:hereditary chiefs were still buried in mounds until the 19th cen-tury (Mabilde, 1897, 1899). Interestingly, historical accounts men-tion mound cemeteries of chiefly lineages side by side withcollective burials of warriors who died in battle against foreigngroups (Mabilde, 1983). As is common among other middle-range societies in the Americas (Feinman and Neitzel, 1984), wag-ing war was one of the main attributes of the Kaingang chiefs, andin historical times warfare was endemic among competing chiefsand against foreigners the Portuguese and the Xokleng(Mabilde, 1897, 1899). Organized warfare, especially against out-siders in times of stress, circumscription and crisis, is known toplay a major role in the consolidation of hereditary leadership intribal and chiefly societies (Redmond, 1994), and the Tupi-Guarani menace might have provided just such an opportunityfor southern proto-J prospective leaders to seize power.

Before moving on to the conclusion, we would like to point outthat the southern proto-J mound and enclosure complexes are notthe earliest expressions of monumentality in southern Brazil. Onthe adjacent Atlantic coast, shell mounds of monumental propor-tions known as sambaquisflourished during the mid Holocene witha peak between 4000 and 2000 B.P. (DeBlasis et al., 2007; Gasparet al., 2008; Fish et al., 2000, 2010, 2013). This earlier tradition isan interesting case of comparison: beyond their chronologicalprecedence, thesambaquispresent distinct funerary practices andconstruction processes, and appear to have emerged in a differentsocial environment. The largest sambaquis can reach up to 70 mheight and are composed of thick constructive shell strata alter-nated with thin organic layers containing numerous burials andfeatures (DeBlasis et al., 2007; Gaspar et al., 2008; Fish et al.,2000, 2010, 2013; Villagran, 2014). Long viewed as campsite mid-dens of mobile fishers and gatherers, the sambaquisare now inter-

preted as intentionally built funerary and feasting arenas.

Fig. 4. Kernel density map of mound and enclosure complexes (MECs) and sites with evidences of interaction between southern proto-J and Tupi-Guarani groups, using asearch radius of 30 km. Also shown is the sampling grid of 30 30 km cells. 3D view shown on the right.

Table 3

Spearmann correlation coefficients for density of mound and enclosure complexes

and density of interaction sites. All results are significant at the 0.01 level.

Sampling grid cell size

20 20 km 30 30 km 40 40km

Kernel density search radius

20km

.786

.773

.74530km .741 .72 .68640km .725 .689 .655

206 J.G. De Souza et al. / Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 41 (2016) 196212

-

7/26/2019 Genesis of monuments CORTELETTI (1).pdf

12/17

Micromorphological analyses have demonstrated that the shelllayers are intentionally accumulated, composed of reworked mid-

dens recurrently deposited in basketloads to cover funerary areas(Villagran, 2014). A projection based on the number of burialsfound in block excavations at these sites suggests a potential num-ber of over 40,000 individuals interred over a period of almost800 years of site construction for the largest shell mounds (Fishet al., 2000). The burials, located in the organic thin layers, showlittle differentiation. They are clustered in groups surrounded bypostholes, possibly representing small funerary areas for affinitygroups, and are accompanied by feasting remains (DeBlasis et al.,2007; Gaspar et al., 2008; Klokler et al., 2010). This pattern stronglycontrasts with the short lived, more exclusive episodes of inter-ment of a single or a few individuals at the southern proto-Jmounds. GIS analyses have shown that sambaquisare intervisibleand share largely overlapping catchment areas with a lagoon as

their epicenter, revealing a social landscape of shared territoriespunctuated by highly visible monuments to the ancestors

(DeBlasis et al., 2007; Gaspar et al., 2008). Interestingly, the skele-tal remains of individuals buried in sambaquisexhibit surprisingly

few indicators of violence (Lessa and Gaspar, 2014). In summary,the largestsambaquisare now seen as long lived ceremonial cen-ters dedicated to the cult of ancestors by territorially stable groupsliving on the coast; their construction, rather than resulting fromthe mere accumulation of refuse by nomadic fishers, was inten-tional and embedded in ritual practices (DeBlasis et al., 2007;Gaspar et al., 2008; Fish et al., 2000, 2010, 2013 ).

Thus, 5000 years before the emergence of the southern proto-Jmound and enclosure complexes in the highlands, the Atlanticcoast was dotted by monuments that spoke of a very differentsocial environment, one of sharing, relative peace, and collectiveremembrance of group ancestors. Therefore, we stress that costlysignaling, materialization of authority, and resistance to outsiders all relevant to explain the development southern proto-J funer-

ary mounds are not necessarily found everywhere where monu-ments emerged. As thesambaquiexample demonstrates, a case by

Table 4

Dates for mound and enclosure complexes.

Site name RCYBP Cal AD (2-sigma) Context Reference

RS-PE-31 110 40 (Beta 276193) 1685. . . Mound Iriarte et al. (2013)Posto Fiscal 200 30 (Beta 309038) 1655. . . Off-mound Iriarte et al. (2013)SC-CR-06 220 40 (Beta 190312) 1640. . . NI De Masi (2005)Abreu & Garcia 230 30 (Beta 395740) 16401880 Burial This workAbreu & Garcia 270 30 (Beta 395743) 15101805 Burial This work

Abreu & Garcia 300 30 (Beta 414096) 15001795 Mound hearth This workSC-AG-108 310 40 (Beta 226125) 14901800 Burial Mller (2008)Abreu & Garcia 330 20 (UGAMS 19003) 15001650 Burial This workPosto Fiscal 330 30 (Beta 304479) 14951655 Mound Iriarte et al. (2013)RS-PE-293 340 40 (Beta 242860) 14751655 Burial De Souza and Cop (2010)RS-PE-21 350 40 (Beta 242868) 14601650 Burial De Souza and Cop (2010)Abreu & Garcia 360 30 (Beta 395741) 14801645 Burial This workSC-AB-96 360 40 (Beta 190303) 14601645 Burial De Masi (2005)SC-AG-100 370 30 (Beta 226124) 14601640 Burial Mller (2008)Posto Fiscal 370 30 (Beta 309037) 14601640 Mound Iriarte et al. (2013)Abreu & Garcia 370 70 (Beta 395744) 14351795 Burial This workAbreu & Garcia 400 30 (Beta 395742) 14501630 Burial This workSC-AG-77 420 40 (Beta 190311) 14401630 NI De Masi (2005)SC-AG-12 430 40 (Beta 185442) 14351630 Burial De Masi (2005)SC-AG-12 470 40 (Beta 185444) 14051620 Burial De Masi (2005)PM01 480 60 (Beta 221417) 13951630 Enclosure Iriarte et al. (2008)RS-PE-293 490 40 (Beta 242869) 14001610 Burial De Souza and Cop (2010)

SC-AG-98 560 50 (Beta 175188) 13151460 Burial Mller (2008)SC-AG-12 600 40 (Beta 190304) 13101445 Hearth De Masi (2005)PR UV 11 680 70 (SI 1010) 12301430 NI Chmyz (1968)SC-AG-12 690 40 (Beta 185443) 12851395 NI De Masi (2005)PM01 720 40 (Beta 237105) 12701395 Enclosure Iriarte et al. (2008)PM01 760 40 (Beta 237106) 12201385 Enclosure Iriarte et al. (2008)PM01 760 60 (Beta 221418) 12101395 Enclosure Iriarte et al. (2008)SC-CL-94 770 40 (Beta 275576) 12201385 Mound Schmitz et al. (2010)SC-AG-75 980 40 (Beta 190309) 10201190 Mound De Masi (2005)Posto Fiscal 1070 40 (Beta 303594) 8951150 Enclosure Iriarte et al. (2013)

Table 5

Dates for Tupiguarani sites in the Upper Uruguay River.

Site name RCYBP Cal AD (2-sigma) Reference

RS-VZ-41 225 50 (SI 701) 1630. . .

Miller (1969) and Stuckenrath and Mielke (1973)SC-U-54 250 90 (SI 546) 1495. . . Piazza (1969) and Stuckenrath and Mielke (1972)SC-U-368 420 60 (Beta 118376) 14351640 Noelli (1999a)SC-VX-5 490 70 (SI 548) 13251630 Piazza (1969) and Stuckenrath and Mielke (1972)SC-U-55 510 70 (SI 547) 13151625 Piazza (1969) and Stuckenrath and Mielke (1972)SC-U-368 530 70 (Beta 118375) 13001625 Noelli (1999a)SC-VP-38 590 100 (SI 826) 12301625 Miller (1971) and Stuckenrath and Mielke (1973)SC-U-55 620 80 (SI 550) 12751455 Piazza (1969) and Stuckenrath and Mielke (1972)SC-U-53 770 100 (SI 439) 10451420 Brochado et al. (1969)SC-U-71 900 50 (Beta 118377) 10451275 Noelli (1999a)SC-U-69 1070 100 (SI 549) 7701215 Piazza (1969) and Stuckenrath and Mielke (1972)

J.G. De S ouza et al. / Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 41 (2016) 196212 207

http://-/?-http://-/?- -

7/26/2019 Genesis of monuments CORTELETTI (1).pdf

13/17

Fig. 5. Calibrated dates for mound and enclosure complexes (yellow) east of the CanoasPelotas confluence and for Tupi-Guarani sites (red) in the Upper Uruguay River. (Forinterpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

208 J.G. De Souza et al. / Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 41 (2016) 196212

-

7/26/2019 Genesis of monuments CORTELETTI (1).pdf

14/17

case analysis is needed to account for all the social processesbehind the appearance of large scale architecture.

6. Conclusion

Archaeologists working in lowland South America are startingto shed new light on past population displacements, contact andconflict in relation to processes of ethnogenesis (Heckenberger,2005; Politis and Bonomo, 2012), the construction of landscapes(Moraes and Neves, 2012; Neves, 2011; Neves et al., 2014;Schaan, 2011) and the consolidation of new forms of authority(Dillehay, 2007). Within that context, the southern Brazilian high-

lands have proven to be one of the most fruitful cases for debatingthe emergence of monumental landscapes hand in hand with therise of complex, regionally organized polities capable of resistingoutsiders. In the introduction, we mentioned the concept, elabo-rated byVandkilde (2007), of macro-regional phases of conjunc-ture. Our data allowed us to conclude that the turn of thesecond millennium in southern Brazil can be considered one ofsuch phases that is, a hot period where multiple influencesmet, interacted, and resisted each other, giving origin to a set ofunprecedented social developments.

In this article, we examined the development of a new form offunerary monument, the mound and enclosure complexes of thesouthern proto-J groups, in relation to a specific historical event:the rapid expansion of the Tupi-Guarani groups from their home-

land in distant southwest Amazon into the southern Brazilianhighlands. We demonstrated a chronological coincidence betweenthe first incursions of the Tupi-Guarani into the southern Brazilianhighlands and the construction of mound and enclosure complexesby the local groups. Our results showthat the areas where this typeof monument proliferated were those where the local groups chosenot to interact with the outsiders. This is evident in the area withthe earliest and most densely concentrated mound and enclosurecomplexes: the CanoasPelotas confluence. This region has a longhistory of southern proto-J occupation, with stable territories evi-denced in their highly structured built landscapes. In fact, this wasone of the last indigenous territories to be conquered by the Brazil-ian national state in the southern part of the country, and repre-sented a refuge of the southern J groups until the 19th century

(Noelli, 2004). We have evidenced that, long before that, this areawas also a frontier for the Tupi-Guarani, who settled along the

Uruguay River, interacting intensively with the southern proto-Jgroups along the way (De Masi and Artusi, 1985; Rogge, 2005;Schmitz and Becker, 1968) but never succeeded in expanding theirterritories beyond the confluence zone. A key element in the resis-tance offered by the local groups was the development of a highlymonumentalized landscape that signaled their capacity of mobi-lization and materialized the emergence of new forms of authorityin the effort to repel the invaders: chiefly lines inscribed in themounded landscape that remained so until historical times.

Our focus was on the CanoasPelotas basin due to the earlydates and quantity of data available, but we recognize that similarprocesses must have been in place simultaneously or later in otherregions of the southern Brazilian highlands where isolated south-ern proto-J monuments were recorded. Although out of the scopeof this study, it is likely that the Tupi-Guarani advance has alsoprovoked parallel reactions by other pre-established groups ofthe Rio de La Plata basin. With this article, we encourage research-ers throughout lowland South America to consider the impact ofpopulation displacements, conflict and the negotiation of identitiesbetween outsiders and locals in the emergence of new traditionsand, ultimately, the construction of contested landscapes.

Acknowledgments

The ideas of this article stem from years of research in thesouthern Brazilian highlands and were further developed in thecontext of AHRC-FAPESP project J Landscapes of southern Brazil:Ecology, History and Power in a Transitional Landscape during theLate Holocene. JGS and RC were funded by CAPES, Ministry of Edu-cation, Brazil. We thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpfulcomments.