gd ?g`YadW` S`V ?STd[W^ JWYS^^Wf · 2014-03-07 · o LZW A_b[ahW_Waf +, Vd[d_[`Y)iS^Wf egbb^k...

Transcript of gd ?g`YadW` S`V ?STd[W^ JWYS^^Wf · 2014-03-07 · o LZW A_b[ahW_Waf +, Vd[d_[`Y)iS^Wf egbb^k...

-===::::::==~ The six elements - managingwater in Central AsiaBillur Gungoren and Gabriel Regallet

Community water management conjures up images of a vibrantcivil society whose citizens take full responsibility at the locallevel. Is this possible in the former Soviet Union?

1. See 'Water supply and qualityissues in Central and EasternEurope and the NewlyIndependent States', Waterlines,Vol. 16, No.1, IT Publications,London, 1997.

Since they are stillresponsible for family

health and hygiene,women's involvement

in community watermanagement as

primary actors andeducators is crucial

for the sustainabilityof the community

water managementschemes.

Water is a strategic resource, playing avital role in the economic and social

life of arid Central Asia. Since all fiveCentral Asian Republics (Kazakhstan,Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, andUzbekistan) have an agriculturaleconomic base, the rational use andprotection of water resources is cruciallyimportant.l

The regional water crisis stems fromthe unsustainable practices of the Sovietera, as well as from current financialshortcomings. The excessive use ofchemical fertilizers, wasteful irrigationtechniques, and one-crop farming have allcontributed. Over the last 35 years,intensive cotton farming has diverted somuch water from the two rivers which feedthe Aral Sea that, at certain points, itsshoreline has retreated by more than120km. Water-borne diseases such asdiarrhoea, typhoid, and gastroenteritishave become widespread in rural areas,the result of poor sanitation and growingsource contamination. Most of thedrinking-water systems, as well as theirrigation systems, are rapidly decayingthrough lack of maintenance with an·estimated seepage of 80 per cent in ruralareas. Farmers have neither the financialmeans nor the technical know-how tooperate and maintain the systems.

The concept of community watermanagement is a new phenomenon for theregion. During Soviet rule, all planningwas undertaken centrally - as a result,people have little idea about how toinitiate, plan, manage, and sustaindevelopment at the local level. Many ruralleaders continue to look to the newnational government to solve theirproblems - with no success. Externalsupport agencies can assist communitiesand local organizations to develop andimplement pilot projects and programmes,

so that the situation does not reach crisisproportions.

ChallengesCommunity water management cannot beseparated from the overall management ofwater and of the river basins of CentralAsia - it must be conceived within anenabling environment with appropriatelegislation and regulations, The challengesfacing community water management aremultifaceted: institutional, financial,technological, and social - the latterencompassing civil society, gender, andhuman resources.

The current institutional frameworkposes serious difficulties. There is no cleardivision of responsibilities between thevarious ministries responsible for themanagement of natural resources. Inaddition, the Water Resources Ministriesof the Republics are still viewed asresponsible for the production, rather thanthe co-ordination of the sector -understandably, farmers are wary of'taking ownership' of the water-supplysystems because the legislation insistsmostly on the 'right to water', but is muchless specific about ownership and Statesupport.

In Central Asia, the right to establishand operate independent civil institutionsvaries from Republic to Republic: whereasKyrgyz and Kazakh laws facilitate suchinstitutions, Uzbek, Tajik and Turkmenofficials make it difficult for allorganizations to register and operatefreely.

Money mattersLack of money intensifies the challengesposed by the weak institutional andlegislative framework. In the formerUSSR, capital expenditure and most of

IIIIJm:D VOL.17 NO.2 OCTOBER 1998 19

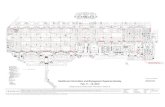

Fergana Valley project 2

Although the F rgana VllIley prOlectt1as only re lIy been up nd runninglor seven morlths, useful lessons have

n I 8rnedMobihzallon at commundleS ndNGOs lakes lime and delet1Tlln \lon.The depeOc:fcncy syndfOlTlEl and I<.tck01 Ifl'Uillive - ir1\1enledfrom SovIetlimos - r W1dQspr88d

• The control CUIlUfi of govemmenlall(l~IIIut/01lSand ted lape hinderproJ I SCtfVlt10sand kill allcreatIVIty eSpec1slly at village levetIdenllfYlng key peepl With powerful

nd respected poslltOl1S wllh,n thegovernmenl struclures who comeIrom targeted communilles helps to1l1l8Vl81 the ov r II presence of

uthol'llles. and facllilales acC8$$ 10publiC Inrarmolron

• The Impiovemeot 01 drirming-waletsupply syslerru; Is a complex, rime-.consumtnj,/ Idsk requmng e:<penlseand //leI mOfJIlOllng Water-supplypipeS In counlnes like Kyrgyzstanar not available In a specillC pi ca.lhey va 10 purchased altharfrom local bazaars, where mostII ma are old and stolen. orImported - pulling up the puceEloclnc pumps have no uaranleeEvon hI:1rdor IS 11f',cMg rei Iepeople With lechn1cal expertIse 10design system Improvements andprcxluce good·quality work Thepro~lleam was lucky 10 lind enInd ndent Wllier engineer whosupelVJsed 1116lechnlClll plans andthe qu lily 01WOrKsTho projeC!lnlrcxluced bM) newwnl r h'lcllflOlogles 10 he regIOn agravlly-Ied syslem was well·raceivQdboth by lIulho!rlllJS and speciallSls

nd I users, The second IShandpumps In Bnsh BuIa Thewatet spe<:llllists (from WllleragenCIes - and our independentongulOOf) If!SISled Ih, lSChnology ~WIIS 'backward' and 'unSVililble'

• While roosl NGO have had someexpeflence wll InlernallonaJ01 niz.ollCllS,they have not been""Ined pre rly. nor hBVOney been

flCOIJIsged to seek seed rundlngTr Inlng prog mmos were ar:I3Pled10 meellhese NGOs' needsRegional meetings and Ir8In"'g

iof1s re ll00ded by IIpar1ners lheir InlllfeslreJlecl tholad<.01 opponunrlies lor people 10come log Iher

• Most 01 tho NGOs opted 101a malecovolunteer for the walerImprovemtltlt component and aWOITWnfor the heallh-hYQlBnecomponen On ver ge. nowevertwo OUI ollhr8e EllXIVOIunleers 81eremal In some plocas, NGOI ers InSISted on selooling lhel'lomtly members as ecoomlunleers orlor olher lasks Ihls wasdlscovraged by the ISW leaml

20

the operational expenses of the watersector were covered by central budgets -such automatic financial support is nolonger received from the State, Further,there are few economic incentives foreffective water management andconservation. For example, the pricingpolicy adopted by most regionalgovernments is to fix a unique tariff forirrigation-water supply, regardless of thereal costs of operation and maintenance(O&M). All countries now charge formunicipal and industrial water supplies,but introducing charges for irrigation anddrinking water is much more difficult.Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan brought incharges, but the current economicsituation makes collection very difficult.

Inappropriate technologyNor are the technologies currently in usenecessarily the most efficient. The water-supply systems developed during theSoviet era were energy-intensive andcentralized; almost all systems aredependent on electricity. In rural areas,there are none of the individual wells,handpumps or other appropriate systemswhich the people could easily operate andmaintain. In addition, energy shortagesare widespread; power cuts damage theelectric motorized pump systems, andpeople go without water for days. How cannewly independent countries alreadyfacing budget deficits replace thesesystems?

It is interesting to note that attempts tointroduce handpumps in one FerganaValley village (see box on left) resulted invillagers being keen to .accept them as longas they get water in the long run, whereaswater specialists (mostly Russianengineers) and some lower-level officialsresisted what they considered 'backward'and 'inappropriate' technologies.

One of the factors vital to successfulcommunity water management is a'sympathetic' social setting, and in CentralAsia, the collapse of the Soviet systembrought about widespread socialdisruption. Families are disintegrating,educational and health establishmentshave collapsed, levels of poverty andcorruption are rising dramatically, andsocial services have been decimated.Women bear the negative consequences oftransition disproportionately. Their

traditional support mechanisms havebeen either abandoned or reduced.Women now make up most of theunemployed; they are also attempting tocope with re-emerging patriarchal values.Since they are still responsible for familyhealth and hygiene, women's involvementin community water management asprimary actors and educators is crucial forthe sustainability of the community water-management schemes.

StrategiesInvolving local communities in themanagement of drinking-water andsanitation has not yet been tested in theregion; even the few experiences ininitiating water users' associations(WUAs) for irrigation have not beensuccessful due to lack of long-term vision.

Strategies that will facilitate theintroduction of community watermanagement need to address the level ofdevelopment of institutions, people, andtechnologies:• The institutional framework shouldreflect a new distribution ofresponsibilities: the co-ordinationfunction should be assumed by theMinistry of Water; production andmanagement functions for the majorinfrastructures should be under theresponsibility of technical agencies; andthe management of community watersystems should be delegated to localorganizations such as WUAs. TheFergana Valley Project strives tofacilitate working relationships betweenthe community organizations, localofficials and technical agencies in eachvillage through newly established watercommittees comprising 4 to 11members, depending on the number ofneigbourhoods (mahallahs) where thewater system has be.en improved.Members are selected by the users, andwomen must make up at least 50 percent. Their main function is to collectmonthly water charges, operate andmaintain the water system - in co-operation with the official technicalagency - and keep the users informedand involved in decision-making -each village adopts a charter and by-laws fixing rights and duties.

• Legislation, along with appropriatemechanisms for enforcement and

VOL.17 NO.2 OCTOBER 1998 ~

monitoring, needs to be revised if theinstitutional changes are to reflect astructural change. Without the involve-ment of local communities in the legaland regulatory framework, voluntaryassociations or committees will neitherbe efficient nor prosper. Legislationshould also allow local communities toregister as associations, to initiate andmanage local water schemes, and to fixand collect water charges.

• Water management should also beapproached from an integratedperspective, and not only with atechnical view - this requires an equalpartnership between ministry, technicalagencies, and users. In addition, theintegrated approach links safedrinking-water supply to sanitation,waste treatment, and environmentalprotection; the last three aspects havebeen badly neglected in all fiveRepublics. The Fergana Valley Projectdemonstrates such integration throughits three main components - theimprovement of water-supply systemsfor both domestic and livelihoodpurposes; education on health, hygieneand environmental protection; andsmall-scale credit for domestic foodproduction and for the establishment ofcommunity revolving funds.

• The upkeep, restoration and building ofinfrastructures providing water supplyand sanitation must remain agovernment responsibility, through theMinistry of Water. Communities can beresponsible for O&M, as well asrunning affordable small systems suchas handpumps, gravity-fed andrainwater harvesting systems. But veryfew are still in operation in the region;their introduction will require trainingand supervision as well as accessibleservice points for spare parts. Inaddition, the revitalization ofindigenous knowledge and systems insuch a drought-prone region is worthtesting.3 In the Project, O&M aspectsinclude assistance to mobilizecommunities to care for thesustainability of the improved systemthrough the establishment of five watercommittees, which decide on theallocation to and payment of water byeach household, and repairs. Peoplecontribute both labour and moneytowards system improvement.

IImIIItl:m VOL.17 NO.2 OCTOBER 1998

• Capacity building. In comparison withother developing countries, thevillagers and farmers are well-educated,and possess fairly good technicalknowledge. What needs to beintroduced is the development ofmanagement skills as well as O&M oflocal systems. The Fergana ValleyProject has also started to fosterexchange of experience among the fivevillages to establish ties for a networkon water issues.

• Equal involvement of women and men inall stages of community watermanagement is key. Women are oftenlimited to being users and providers ofwater. Given their knowledge aboutwater-sources, quality and reliability,women have a lot to contribute todecisions related to the design, andO&M of the systems. They often havethe clearest understanding of the linksbetween safe water and health, theimportance of source protection, andthe impact of water on everyday living.In the Project, gender-sensitivemanagement assures a leadership rolefor women and the equal involvementof women and men in system O&M,and health and hygiene improvementthrough cultural events, communitywork and incentive schemes.

ConclusionCurrent water management practice inCentral Asia is not sustainable. Thepotential for improvement is large, butpolitical will should result in measures toensure that technical improvements arelinked to necessary policy changes andinstitutional adjustments. In addition,choices made at the community level arelikely to be more cost-effective with theintroduction of affordable technology suchas hand pumps, rainwater harvesting, anddrip irrigation.

The principles of community watermanagement need to be tested in thespecific realities of Central Asia so thatpeople and governments will be convincedof its intrinsic value. That is the challengeof the Fergana Valley Project: empoweringlocal communities by promoting femaleleadership to improve water supply,sanitation, and livelihoods with anintegrated perspective. It is a matter ofdedication, persistence, and patience. •

2. 'Community-basedmanagement of drinking-waterand sanitation in the FerganaValley: strengthening the role ofwomen' was initiated in fivevillages in Kyrgyzstan andUzbekistan by the InternationalSecretariat for Water (IWS), inpartnership with Novib andUnicef. The valley, traditionallythe 'barn' feeding the region, isnow facing a critical watersituation.

3. International Secretariat forWater, 1997. 'Indigenous WaterManagement Systems: Fromlocal practices to policy reform'.Montreal, Canada.

Women often have the clearestunderstanding of the linksbetween safe water and health,and the importance of sourceprotection.

about the authorsBillur Gungoren has been

working in Central Asia as agender advisor since 1995. At

present, she is the co-ordinator of the Fergana Valley

Project for the InternationalSecretariat for Water (ISW).

Gabriel Regallet has beenassisting in the

implementation of capacity-building programmes in

Central Asia. He has been thePrincipal Advisor of ISW since

1993.

Contact: ISW, 54 rue Le RoyerOuest, Montreal H2Y 1W7,

Canada.Fax: + 1 5148492822.

E-mail: [email protected]

21

'"Q)'5tia::'"oc&.>-Q)to(tII>.EQ)

(j;-,