Gastric Necrosis and Perforation Caused by Acute Gastric Dilatation: Report of a Case

-

Upload

mustafa-turan -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

2

Transcript of Gastric Necrosis and Perforation Caused by Acute Gastric Dilatation: Report of a Case

Surg Today (2003) 33:302–304

Gastric Necrosis and Perforation Caused by Acute Gastric Dilatation:Report of a Case

Mustafa Turan1, Metin Sen

1, Emel Canbay1, Kursat Karadayi

1, and Esin Yildiz2

Departments of 1 General Surgery and 2 Pathology, Cumhuriyet University Faculty of Medicine, 58140 Sivas, Turkey

rate of 34/min. The upper extremity pulses were weak,the femoral pulses were absent, and the lower extremi-ties were cold and cyanotic with decreased capillaryfilling. The abdomen was distended and semirigid withinvoluntary guarding. Bowel sounds were absent.

Laboratory investigations revealed: hemoglobin,17.9g/dl; hematocrit, 53.6%; white blood cell count,11900/µl (with 70 neutrophils, 22 bands, and 8 lym-phocytes); platelet count, 352000/µl; BUN, 30 mg/dl;creatinine, 2.5mg/dl. Alkaline phosphatase, aspartateaminotransferase, and lactic dehydrogenase were el-evated to 210 U/l (normal, 38–126U/l), 51U/l (normal,9–36U/l), and 804U/l (normal, 230–460U/l), respec-tively. Blood gases showed that the patient was in meta-bolic acidosis with a blood pH of 7.16. Other laboratoryvalues were within the normal range. Apparently, thepatient had eaten a heavy lunch the day before and afew hours later, his abdominal symptoms had started.The following morning he was taken to a general prac-titioner who gave him omeprazole. Within 6h his condi-tion had worsened and he was brought to the hospital.We also learned that the patient was mentally retarded(borderline: IQ 68–83), which has been confirmed 1year earlier when he was checked due to improperdevelopment of his sexual organs.

The patient was initially resuscitated with intrave-nous hydration and correction of metabolic abnor-malities. He also had neck stiffness, but ocular fundusexamination showed that the optic disc head was nor-mal. Since consultants specializing in infectious disease,neurology, and internal medicine could not explain hisclinical status, an emergency diagnostic peritoneal lav-age was done. Free peritoneal fluid with food particleswas washed out from the abdominal cavity, and he wastaken to the operating room from an emergency laparo-tomy. The stomach was found to be almost totally ne-crotic with intramural emphysema and perforation inthe fundus (Figs. 1 and 2). We found 6 l of free perito-neal fluid and undigested food particles in the abdomen.

AbstractWe report the case of an 18-year-old, mentally retardedboy who suffered acute abdominal symptoms and signsafter eating a heavy meal. Laparotomy showed massivegastric dilatation with near-total infarction and perfora-tion. Total gastrectomy and esophagojejunostomy wereperformed, but the patient died a few hours after theoperation.

Key words Stomach · Necrosis · Bulimia

Introduction

Near-total gastric necrosis and perforation is extremelyuncommon. The rich blood supply of the stomachnormally protects it from ischemia when acute gastricdilatation progresses; however, gastric necrosis may re-sult.1–4 We present the case of a patient who sufferedacute abdominal symptoms and signs after a heavymeal, and was subsequently found to have massivegastric dilatation with near-total infarction andperforation.

Case Report

An 18–year-old boy was admitted to our EmergencyRoom with a history of having eaten a large meal, fol-lowed by signs of shock. On physical examination, hewas unconscious and febrile, with a blood pressure of70/40mmHg, a pulse rate of 170/min, and a respiratory

Reprint requests to: M. Turan, Inonu Muzesi Yani, K.Kazancilar Sok. No 1/4, 58070 Sivas, TurkeyReceived: December 26, 2001 / Accepted: September 3, 2002

303M. Turan et al.: Gastric Necrosis Due to Gastric Dilatation

Neither volvulus nor adhesions were recognized. Theduodenum was dilated to the ligament of Treitz andthere was a sharp cutoff. Focal areas of constrictionwithout ischemia were present in the small and largebowel. Normal pulsations were seen in the superiormesenteric artery. Total gastrectomy and esophago-jejunostomy were performed, but his postoperative pe-riod course was complicated and he died a few hourslater. The total gastrectomy specimen was massivelydilated and gangrenous, measuring 16.5 cm along thelesser curvature and 42.0cm along the greater curva-ture. The fundic wall was paper-thin with a 9-cm perfo-ration on the anterior wall (Figs. 1 and 2). Microscopyrevealed full-thickness necrosis of the gastric wall(Fig. 3).

Discussion

Gastric infarction and rupture of the stomach is rare.1–4

The reported causes of gastric infarction are diverse andinclude intrathoracic herniation,2 volvulus, acute necro-tizing gastritis, ingestion of caustic material, vascularcomprise, and acute gastric dilatation.5–10 About half thecases seem to be related to large meals and acute gastricdilatation, or both, as a consequence of Prader-Willisyndrome, bulimic episodes in anorexia nervosa, andpsychogenic polyphagia.11–14 This catastrophic event ismore common in girls (67%) and usually occurs alongthe lesser curvature (63%). It is uniformly fatal withoutoperative intervention, and the overall mortality is73%.6

Studies have been done on the pathogenesis andpathophysiology of acute gastric dilatation and its com-plications. Revilloid demonstrated that the stomach ofcadavers had to be distended with at least 4 l of fluidbefore perforation occurred.6 The stomach has an excel-lent collateral blood supply and must be very distendedbefore ischemia or perforation results. In experimentalmodels both venous and arterial occlusion are necessaryto produce infarction.15 It was also reported thatintragastric pressure must exceed the gastric venouspressure to result in ischemia and infarction.16 Increasedintragastric pressure is usually the result of a closedloop, secondary to mechanical compression of thecardioesophageal and pyloroduodenal or duodeno-jejunal junctions. The massive distention seen in acutegastric dilatation results in a decrease intramural bloodflow when the intragastric pressure exceeds 30 cmH2O.16

In the pathologic eating disorders such as psychogenicpolyphagia and bulimia, gastric volumes as high as 15 lhave been recorded.6 Ischemia generally occurs before

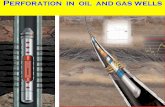

Fig. 1. The stomach was found to be almost totally necroticwith intramural emphysema and perforation in the fundus.The total gastrectomy specimen showed massive dilatationand near-total necrosis. The fundic wall was paper-thin with a9-cm perforation in the anterior wall (arrows)

Fig. 2. Schema of the almost totally necrotic stomach

Fig. 3. Infarction of the gastric mucosa and submucosa. Orga-nizing thrombus can be seen in right lower corner (H&E�100)

304 M. Turan et al.: Gastric Necrosis Due to Gastric Dilatation

rupture. The pattern of necrosis seen in our patient withsparing of part of the lesser curvature and pyloric regionwas similar to that reported by others.6.7 Occlusion ofthe venous drainage of the stomach as a result of highintraluminal tension with increased intraluminal venouspressure appears to be a highly significant factor andmust have been important in this case. We assume thathe ate and drank massively before his abdominal symp-toms started. Psychogenic disturbances, specificallythose related to abnormal eating habits, have beenstressed as important etiological factors in precipitatingacute gastric dilatation.6,17 In fact, our patient’s border-line mental retardation was probably the primary causeof his overeating.

Profound hypotension caused by gastric dilatationand reversed by gastric decompression has been welldescribed.18 Decreased venous return due to directcompression of the inferior vena cava by the dis-tended stomach had been implicated as contributingto shock,19,20 as has splanchnic vessel sequestrationwith resultant tissue hypoxia and metabolic acidosis.21

Splanchnic nerve mediation has also been proposed aspathogenetic.22 Moreover, third space fluid loss maycause relative hypovolemic shock. The shock and meta-bolic acidosis in our patient can be explained by thesemechanisms. His death was attributed to bacteremiaand shock.

It can be extremely difficult to evaluate a patient withthis clinical condition, such as ours. An accurate historymay be impossible to elicit, so the surgeon must rely ona thorough physical examination. The symptoms of apatient with suspected gastric infarction may vary frommild tenderness to abdominal rigidity. The diagnosismay be supported by roentgenographic findings of gas-tric dilatation and pneumoperitoneum.6–7 Resuscitationand appropriate surgical therapy are mandatory forthis life-threatening entity. Failure, or even a delay, inthe diagnosis of gastric infarction proves fatal in morethan 80% of cases.7 Adequate resection of the gangre-nous portion of the stomach is essential and totalgastrectomy is generally required. Successful one-stageresection with esophagojejunostomy has been reportedunder favorable circumstances.3,7 When treatment isdelayed and generalized peritonitis occurs, resectionwith decompression and drainage was also proposedby Reeve et al.23 Total gastrectomy and esophagoje-junostomy were performed in our patient, but his post-operative period was unstable and he died a few hourslater.

In conclusion, the present case illustrates the need forincreased awareness of this rare, but rapidly progressiveand fatal condition. Emergency diagnostic peritoneal

lavage proved very helpful. This case also serves toremind us of the importance of a thorough physicalexamination to rule out other possible etiologies.

References

1. Wolloch Y, Dinstman M. Spontaneous rupture of the stomach.Israel J Med Sci 1973;9:1574–7.

2. Evans DS. Acute dilatation and spontaneous rupture of the stom-ach. Br J Surg 1968;55:940–2.

3. Wharton RH, Wang T, Graeme-Cook F, Briggs S, Cole RE.Acute idiopathic gastric dilatation with gastric necrosis in indi-viduals with Prader-Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet1997;73:437–41.

4. Jefferiss CD. Spontaneous rupture of the stomach in an adult. BrJ Surg 1972;59:79–80.

5. Gibbons WD. Gangrenous intrathoracic stomach. Med J Aust1968;1:451–2.

6. Kernstein MD, Golldberg B, Panter B, Tilson D, Spiro H. Gastricinfarction. Gastroenterology 1974;67:1238–9.

7. Koyazounda A, Le Baron JC, Abed N, Daussy D, Lafarie M,Pinsard M. Gastric necrosis caused by acute gastric dilatation.Total gastrectomy. Recovery. J Chir 1985;122:403–7.

8. Sellors TH, Papp C. Strangulated diaphragmatic hernia with tor-sion of the stomach. Br J Surg 1955;43:289.

9. Strauss RJ, Friedman M, Platt N. Gangrene of the stomach: a caseof acute necrotising gastritis. Am J Surg 1978;135:245–7.

10. Adachi Y, Takamatsu H, Noguchi H, Tahara H, Mukai M,Akiyama H. Spontaneous rupture of the stomach in preschool agechildren: a report of two cases. Surg Today 1998;28:79–82.

11. Willeke F, Riedl S, von Herbay A, Schmidt H, Hoffmann V, SternJ. Decompensated acute gastric dilatation caused by a bulimicattack in anorexia nervosa. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1996;121:1220–5.

12. Abdu RA, Garritano D, Culver O. Acute gastric necrosis inanorexia nervosa and bulimia. Two case reports. Arch Surg1987;122:830–2.

13. Low VH, Thompson RI. Gastric emphysema due to necrosis frommassive gastric distention. Clin Imaging 1995;19:34–6.

14. Beiles CB, Rogers G, Upjohn J, Wise AG. Gastric dilatation andnecrosis in bulimia: a case report. Australas Radiol 1992;36:75–6.

15. Babkin BP, Armour JA, Webster DR. Restoration of the func-tional capacity of the stomach when deprived of its arterial bloodsupply. Can Med Assoc J 1943;48:1–10.

16. Edlich RF, Borner JW, Kuphal J, Wangensteen OH. Gastricblood flow. Its distribution during gastric distention. Am J Surg1970;120:35–7.

17. Saul S, Dekker A, Watson C. Acute gastric dilatation with infarc-tion and perforation. Gut 1981;22:978–83.

18. Cogbill T, Bintz M, Johnson J, Strutt P. Acute gastric dilatationafter trauma. J Trauma 1987;27:1113–7.

19. Englar HS, Kennedy TE, Ellison LT. Hemodynamics of experi-mental acute gastric dilatation. Am J Surg 1967;113:194–8.

20. Passi RB, Kraft A, Vasko JS. Pathophysiologic mechanisms ofshock in acute gastric dilatation. Surgery 1969;65:298–303.

21. Mooney CS, Bryant WM, Griffen WO Jr. Metabolic and portalvenous changes in acute gastric dilatation. Surg Forum 1969;20:352–3.

22. Williams JS. Hemodynamic alterations in acute gastric dilatationin the dog. Surg Forum 1965;16:335–6.

23. Reeve T, Jackson B, Conner C, Sledge C. Near-total gastricnecrosis by acute gastric dilatation. South Med J 1988;81:515–7.

![Mediastinal abscess complicating esophageal dilatation: a ...frequently isolated from cases of acute mediastinitis secondary to esophageal perforation [6], and that was clearly demonstrated](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/60a2b0eeeed65f4a956146e0/mediastinal-abscess-complicating-esophageal-dilatation-a-frequently-isolated.jpg)