Gadfly Magazine Fall 2009

-

Upload

the-gadfly -

Category

Documents

-

view

227 -

download

2

description

Transcript of Gadfly Magazine Fall 2009

the undergraduate philosophy magazine of Columbia UniversityGADFLYTHE

FALL 2009

GADFLYTHE

Fall 2009

ShortsTwo Professors and a Poll

Neuroenhancers and Philosophy

The Disappearance of Walter J. Manville A Morning Edition Obituary

Joga e Pensa Bonito Playing and Thinking Beautifully

The Man or the Masterpiece Between Life and Art

FeaturesA Case for Skeptical Science

Questioning Paradigms

Beyond the Gate A Manifesto of God and Art

A Sentimental Mood Emotions, Morality and Truth

Justifying Biblical Interpretation Islamic Philosophy and Exegesis

CriticismMaking Small Talk With John Collins

An Interview

Neuroenhancers and PhilosophyA Debate

Reinventing UtopiaA Review of First as Tragedy then as Farce

Rebecca Spalding

Donovan Adriano Toure

Thomas Sun

Justin Vlasits

Jacob Hartman

Max Kaplan

Alyssa Lamontagne

Stephany Garcia

Julia AlekseyevaAmaryllis Torres

Puya Gerami

2

4

6

10

16

24

20

14

31

28

32

From the Editor

The Gadfly is sponsored in part by the Arts Initiative at Columbia University. This funding is made possible through a generous gift from The Gatsby Charitable Foundation.

STAFF

Editor-in-Chief Shana Crandell

Managing Editor Bart Piela

Shorts EditorsJoseph Straus

Victoria Jackson-Hanen

Features EditorsAdam Flomenbaum

Alan DaboinSumedha Chablani

Criticism EditorsJulia Alekseyeva

Puya Gerami

Copy EditorsTao ZengLinda Ma

Arts EditorsKhadeeja Safdar

Christina Johnston

Layout EditorsChristina Johnston

Hong Kong Nguyen

Technology DirectorBourne Yuan

Business and Finance Manager

Tao Zeng

Thanks to the Columbia and Barnard Philosophy Departments for their support and assistance.

ARTISTSChanna Bao

Maryn CarlsonConstance Castillo

Sueminn ChoLeslie Koyama

Ashley LeeLouise McCune

Daniel NyariGabriella RipollKhadeeja Safdar

Is philosophy really so obscure? This is an accusation levelled at me all the time. And, frankly, it’s not an accusation I find easy to respond to. Explaining why the discipline I have chosen is vital, relevant and powerful to my best friend, an engineering major, is hard enough. When I step outside the boundaries of academia, it’s damned near impossible.

To its critics, philosophy is obscure, difficult, and anachronistic. It is the discipline of the Ivory Tower (although academics in other fields might take offense at that). The high-minded philosopher never comes down from the tower. The questions of philosophy are far removed from the questions of everyday life.

Where I personally struggle for a response to this accusation, I think The Gadfly presents one in resounding clarity. Within its covers, philosophy strives to make sense of the the rubble left behind by capitalism. It amiably answers questions on decision theory, dreams and political aspirations. And when a fire is about to engulf Da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” and take the life of the security guard paid to protect it, it asks, which do we save: the man or the masterpiece?

One of the strengths of philosophy is its keen sense of itself. Philosophers are aware of their obscurity. They disparage the hypothetical Manville, the ultimate figure of obscurity. They realize they must not only descend from the Ivory Tower, but submit it to scrutiny.

Philosophy helps us investigate questions regarding other disciplines as well, such as science and theology. It can make a case for skeptical science or take a look at Biblical exegesis through an Islamic lens. Philosophy broadens horizons and opens up the mind.

It fears no subject and it is willing to take up any debate. The philosopher has good reason to defend neuroenhancers, while other thinkers leave the subject alone. It even takes up the complicated world of emotions. On one view, they underlie morality. On another, they are the basic atoms of experience; they lead to God and art.

More than anything, philosophy challenges dogma as it maintains explanatory power. It is a vital way of approaching the world. But it is also very much in and of the world. It is the mission of The Gadfly to demonstrate just this. We reclaim philosophy from the Ivory Tower, if just momentarily, to show the possibility of a future full of thought and self-reflection.

Bart Piela

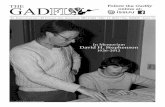

COVERDaniel Nyari

THE GADFLY FALL 20092

Yes

85%

No

15%

Is the current illicit use of

neuroenhancers problematic?

Yes

46% No

54%

Is the current use of

neuroenhancers with a prescription

problematic?

Yes

69%

No

31%

If legalized and approved by the

FDA, is the use of neuroenhancers

problematic?

It’s interesting to wonder what some of our philosophical heroes might have thought about the over use of drugs like these. For Platonists, i.e., (in this case) for those who believed that there are eternal immutable essences to be grasped by the human understanding, any drug that helps one attend to those eternal objects might be happily swallowed. After all, it’s hard to contemplate eternity if all you want to do is fidget or play video games. On the other hand, even some Platonists thought the process of struggling toward those truths was part of what prepared one to discern them. The exercise of struggling to attend to them was supposed to be difficult; otherwise, the soul wouldn’t be strong enough to bear them. But for those philosophers like Kepler and Leibniz, who valued the result, such drugs probably could not be overused. Unfortunately, for these Platonists—and maybe for us—there don’t seem to be any eternal immutable essences. And so where does that leave us?

I take it that the “abuse” of neuroenhancers entails becoming addicted to them. In that case, you can become addicted if they work, but you might become addicted if they don’t work. If neuroenhancers do in fact improve concentration and ward off sleepiness, there seems to be nothing wrong with them, no more than there’s anything wrong with using crutches to get around if you’ve broken your ankle. In this case there is the risk of becoming addicted, precisely because you find that neuroenhancers do work and you don’t want to rely on your unaided brain the way you used to. But if they don’t work as touted, you still might become addicted through repeated attempts to try them “just one more time,” like continuing to buy lottery tickets long after your first few failures to win anything. Here’s a thought: did the manufacturers of neuroenhancers need to use neuroenhancers to improve their thinking when devising the best way to make money from selling their wonder product?

Alan Gabbey

Christia Mercer

Two Professors and a Poll

shorts 3

Branching Out:Philosophy-Related Courses Outside the Department

A Kind of Wild JusticeComparative LiteratureBC3121 Collomia CharlesTR 4:10-5:25

Imagining the SelfComparative LiteratureV3235 Rebecca StantonMW 11:00-12:15

Discourse of Self in RussiaComparative LiteratureG6110 Rebecca StantonW 4:10-6:00

Economies and Phil. SeminarEconomics: PhilosophyW4950 John Collins & Bernard SalanieT 9:00-10:50

French Philosophical TraditionFrenchW3695 Pierre ForceMW 1:10-2:25

Aesthetics & Phil. of HistoryGermanG4250 Dorothea von MueckeT 4:10-6:00

Theories of the Politcal SelfPolitical ScienceW3135 Instructor TBATR 4:10-5:25

Phil. and ReligionReligionV3730 Wayne L. ProudfootMW 2:40-3:55

2895 Broadway, New York, New York 10025Phone: 212.666.7653 Fax: 212.865.3590

THE GADFLY FALL 20094

The purpose of the morning edition is to provide the

fodder for evening small talk. This latest innovation in modern man’s arsenal of banality is intended to lift from Adam’s brow the heavy burden of contemplation in a universe whose most conspicuous characteristic is complexity and whose most discernible riddle is consciousness. It should therefore come as no surprise that news of the disappearance of the abstruse academic, Professor Walter J. Manville, covered in the graying columns of grim Thursday, was buried beneath the pages of Friday’s prostitution plot. It was completely forgotten by sunny, shimmering Saturday, high seventy-five. Now, a sparse year later, he has been tacitly announced dead by the Discourse Department that quietly scrubbed its office clean of his memory and delivered his delinquent property to the doorstep of yours truly, his only professional successor and, consequently, his only academic adversary. I am thus faced with the impossible

task of edifying the legacy of the man who refused edification, who considered the written word to be the harbor of humanity’s ills, who thought himself the forbear of an ideology capable of transcending the biological confines of mortality, who abhorred obituaries, who seemed ghostlike even before he disappeared into the April dusk, who I am obliged to call the seasoned master of my juvenile discipline, who became my greatest adult rival, who was said to be, “the most divisive figure of contemporary thought,” and who had, by all recent accounts, gone insane: Manville. Little is known about Manville’s early years, which is either an indication of the rigor the professor employed in suppressing the facts surrounding the origin of his enigmatic persona, or the aim of the Luftwaffe pilot responsible for bombing his childhood home. It was then that his birth records went up in flames, along with a spotted cat named “Pumpkin,” according to his neighbor Ms. Smits, interviewed for the documentary Manville. The film only succeeded in enshrouding the man in more mystery—not one photograph was shown of his physical person in all ninety minutes.

Even less is known of his university education. Manville appeared as if from nowhere into the upper echelons

of academia as a doctoral candidate, descending on the small village of Princeton where he was a regular at 112 Mercer Street after meeting its famous resident in a local ice cream parlor. Einstein must have seen himself in the broodingly brilliant young buck, as interested as he was in discovering the Theory of Everything. Of course, the main difference between the two was that Einstein failed where Manville succeeded. Newton’s successor comically failed to explain everything in an edible equation, tragically falling victim to the obscurity he sought to apprehend. Was it then, after the April death of his predecessor that Manville first discovered

The Disappearance of Walter J. Manville, Ph.DRebecca SpaldingIllustrated by Maryn Carlson

In 2004, the NYT published Jacques Derrida, Abstruse Theorist, Dies at 74

shorts 5

the philosophy that would make him famous, an ideology that he claimed capable of transcending the confines of animal existence? It has been surmised, though scholars cannot be certain. Manville notoriously did not write a word throughout the entirety of his career, but elected only to speak in enigmatic fragments to the few followers he allowed in his presence (myself included), the most famous of which was, “I am that I am,” first uttered June 14, 1973. Manville never made a single public appearance. Instead, he relied on myself and other disciples to disseminate his ideas to the uninitiated. Needless to say, this was an extremely difficult task. Mr. Manville did not believe in summaries, writing, or representation. But I will now attempt to summarize his doctrine for the sake of those insisting on the obituary’s obligation to offer a one-sentence reduction of a lifetime’s body of thought. He cited that the true divinity of the human spirit grew stale within the limits of a lettered cage. Divinity was what Manville sought, after all. His followers insist his teachings are indeed the means of transcending the material world.

The validity of Manville’s doctrine has been called into question since its appearance and, more recently, since his personal

disappearance and presumed death. In the words of critic Barbara McCarthy, “it is twice as illogical to believe that an immortal could die as it is to believe a human could become immortal via a poppycock philosophy.” Many share her low estimation of the man, finding him to be the very embodiment of a school of thought that undermines the pillars of classical education. Mr. Manville once commented on the phenomenon, saying, “A prophet is not without honor but in his own time, among his own kin, in his own house.” I was his most ardent follower until our famous falling out two years ago. It was then that I left my duties as his public liaison and personal confidante in order to publish my first book containing all his teachings, written down word for word. “The Betrayal of the Millennium,” read

the headline of The Journal, known for making hyperbolic claims. They were, however, correct in saying that Manville was my greatest adversary. But what scholar must not do violence to what came before in order to erect his own philosophy? With no one to proselytize his doctrine, Manville languished in obscurity before his disappearance eleven months and fifteen days ago.

Before I conclude, I feel it pressing to respond to the libelous claims that I created Walter J. Manville many years ago, and have

since been disseminating the negative conception of human divinity central to his, and thus my own, philosophy—if I am to be presumed his Creator. Were it true, I would be the author of the second-greatest fiction ever devised, a title I would not easily deny if it had any validity. Even more absurd are the claims that the man is not dead but has instead withdrawn from the world. To these believers I say that there is no doubt in my mind that the rotting body of Walter J. Manville will soon be found by law enforcement, perhaps behind a boulder in some distant cave where he sought refuge as a hermit in the last days of his earthly life.

R.C.S. April 7, 1985

THE GADFLY FALL 20096

Science attempts to explain how the world works in a systematic way. In order to do this, scientists focus

on foundational moments, such as when the universe began, when life began and when humans began to use language. The pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Thales made the first documented attempt at a scientific explanation when he claimed

that the world was made of water in various mutations. In the intervening two and a half millennia, scientists have come

to disagree over the nature of the essential substances that make up our world. Some now argue that its fundamental unit is something like a string, vibrating in different ways to make up the properties of different elementary particles. Despite the differences between theories, they all share the aim of discovering what lies at the foundation of our universe.

How do scientists begin to ask questions regarding the origins of our universe in a way that distinguishes them from theologians and philosophers? Historian and philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn argued that in order for scientists even to begin asking these sorts of questions in a scientific way, they need a certain number of methodological and theoretical assumptions to

ground their work. He calls this a paradigm.

P aradigms organize the world so that it can begin to be studied by

scientists. They determine the relevant questions they can ask and the ways they can go about discovering the answers. A paradigm acts as a sort of map that guides scientists along in their research. The scientist’s job is to fill in the blank areas and clarify details. The usefulness of a

map derives from its ability to exclude irrelevant information and pinpoint the most important features. A road map, for

A Case for Skeptical ScienceJustin Vlasits

Illustrated by Ashley Lee

features 7

example, does not need to include the same detail on elevation as a topographical map because its function is only geared towards providing a clear outline of various routes by which a driver could navigate a given area. A paradigm, similarly, provides a guide with which one can study, for example, the motion of a ball through space by excluding irrelevant information (e.g. the color of the ball) and including relevant information (e.g. the mass, volume, potential and kinetic energy). Like any map, the paradigm has its own logic, which includes criteria by which to judge a statement true or false. But there is a certain priority to these kinds of assumptions—they must exist strictly before any other assumptions in order to have the power to verify other statements in the theory. That

is to say, every theory points to its own validity and in one way or another excludes every other theory that it cannot incorporate into its logic. There are no criteria of truth external to the theories themselves that have the ability to judge between one theory and another. This is because a theory defines a way of seeing the world that is not inherently more or less true than another.

If this is so, how do we know that our current scientific assumptions are better than, say, Aristotle’s? It is

exactly this kind of question that drove ancient Pyrrhonian skeptics, especially Sextus Empiricus, to suspend judgment “on all matters of belief.” Sextus argued

that every account can be opposed, in one’s mind, with an opposite account, and that both accounts can be equally

believable. If this is true, the scientific paradigm becomes highly problematic for two important reasons. First, if any of a paradigm’s assumptions can be replaced by a contradictory assumption, then no paradigm can have truly unassailable assumptions. Second, if these opposite accounts are really equally believable, then there is no reason that someone should accept one paradigm over another. It seems as if Aristotle’s physics are equally ‘plausible’ as the most recent formulations of Quantum Mechanics because neither can be completely justified without appeal to the criteria of truth that come from the theory itself. Kuhn argues along these

THE GADFLY FALL 20098

lines when he says that paradigms are incommensurable, but he allows for the possibility of scientific progress. After all, paradigms get better and better at “solving puzzles.” Namely, they get better at asking the kinds of questions that they can answer and providing reasonable and meaningful answers to those questions. But this only happens as long as scientists strictly adhere to their paradigm as the model for reality—otherwise they would engage in characteristically “unscientific” discussions of ontology and methodology and never get around to doing actual investigation. Kuhn argues that while it may be impossible for science to get us to absolute truth, its usefulness is dependent on scientists accepting paradigms.

Sextus, however, doesn’t seem to think that we need to depend on a paradigm in order to investigate. In

fact, he sees suspension of judgment as the first step to real investigation. On Sextus’ view, when someone is investigating

based on paradigms, they are not really investigating at all since they think they already know how the world works. The skeptic, however, suspends judgment, and thus his investigation does not have any predetermined conclusion. Just because the skeptic suspends judgment, however, does not mean that he is unable to use some of the assumptions and techniques

employed by paradigmatic science. He simply has to re-appropriate them to non-dogmatic purposes. Instead of aiming for a definite answer, such as: “Atoms each have a nucleus made of protons and neutrons surrounded by electrons,” he might come out with some sort of conditional such as: IF “Protons, neutrons and electrons have masses x, y, z and charges a, b, c” AND IF “Our theory of electromagnetic interaction is true” THEN “Atoms each have a nucleus made of protons and neutrons surrounded by electrons.” It is important to see that atomic theory no longer has the same kind of ontological value—it is simply a defined placeholder that aids our understanding of certain events in the world. Unlike paradigmatic science, which makes statements about the world that at some point cannot be justified, skeptical science leads to a network of belief commitments that all take the form of similar conditionals. The potential power of such a methodology is that it does not require the same belief commitments that paradigmatic science does. Instead, it allows for multiple networks of your beliefs to exist independently of each other such that the skeptic never has to decide on the rightness of a single paradigm. This means that they would never have to make the choice between the Aristotelian and the Quantum Mechanical worldview because any such choice seems to be unjustifiable in the eyes of the skeptic. This does not prevent the skeptical scientist from working within the framework of modern physics by sidetracking him in ancient methods; it only allows him to avoid commitments to a theory that he cannot justify to be true. This eschews the problem of criteria to decide true and false statements precisely because it does not purport to make those kinds of statements.

Their task is never complete, but on its way their search accumulates knowledge about the way the world works. Such a mission for science niether compromises its integrity, nor diminishes its importance.

features 9

The skeptic is thus immune to the paradoxes that plague normal scientists, yet is still able to carry

out minute observations, such as Sextus did in comparative anatomy (one of the most active scientific fields in the Hellenistic world). If one is inclined to think that what Sextus did was real investigation, then the

potential of skeptical science is obvious. He is also in a much more flexible position than a normal scientist: he is willing to allow for several meaningful interpretations of a single experiment. So while he is perfectly able to “solve puzzles,” he aims for something higher: understanding. Even though all of his efforts are unable to lead him to the positive statements, “This is true” or, “This is false,” he has a number of different perspectives on how the world works. He sees connections between different beliefs and has grappled with interpreting experimental data. What in this is not scientific?

After all, the word skeptic comes from the Greek verb skeptein, “to

search,” and whether it is for an explanation of the origins of the universe or the set theoretic foundations of mathematics, skeptical scientists can look for models and heuristics that can aid our understanding of certain aspects of the world. Yet they also understand the problems inherent in the models and heuristics themselves. Their task is never complete, but on its way, their search accumulates knowledge about the way the world works. Such a mission for science neither compromises its integrity, nor diminishes its importance.

The skeptic is immune to the paradoxes that plague normal scientists, yet is still able to carry out minute observations.

THE GADFLY FALL 200910

There is a change so drastic that takes no more than a moment, and spans no more than a footstep.

It is nothing more complicated than the movement from a point at which a loved one is visible to a point of loneliness. There is no process of taking leave; the separation is instantaneous. For short periods of time one experiences bliss, his entire consciousness bound together with one of those rare beings that has earned a portion of his love. During such times, the pressure on one’s mind is reduced, the air allowed to flow to another in a stream of words, rendering the paradoxical and grueling act of self-reflection unnecessary. But all arrivals anticipate their own departures. In the midst of

celebration we count down, until finally the horizon is near. We come to the gate, a place at which to unweave selves from one another, and to unravel identities of multiplicity and unities forged out of love. Instantaneously, one departs and his loved one vanishes. Without prior notice or preparation, he becomes a new creature. At this moment, the air that had so easily flowed from himself to another loses its outlet. Every thought is suppressed, pushed back into his mind, prevented from breathing the fresh air of love and reaching a welcoming listener. These suppressions of feeling are the birth pangs of God and poetry, twin sources of relief during moments of exile.

Beyond the GateJacob Hartman

Illustrated by Constance Castillo

features 11

To escape from loneliness the self discovers its previous attachments in new guises and exchanges autonomy for happiness. Human love does not hold a monopoly on happiness, which is a goal towards whose achievement anything will suffice. The floor itself might function as a means towards this end, providing a lonely sojourner with a relationship in the form of a spatial context. He takes a solitary walk in the park near his new home so that he can watch a father teach his son to play football, pretending that he is in on their fun, or so that he can hear a dog bark at him and look him in the eye. He becomes more sympathetic towards animals than he thought he would ever be. The mere chirping of a bird stirs up the knowledge that there is suffering, reproduction, and growth all around him. This connects him to the life he left behind. God is born from these evanescent mirages of permanent happiness. To substitute for that being that could be inches away but is now a world apart, the detached soul splits its own identity into two, investing its new creation with attributes belonging to its former love, relating to it in a similar way, and feeling the sorely missed touch and warmth of human love in the very immediate presence of this all-encompassing being.

Many, however, are not lucky enough to travel this happy road. Before the chance

arises to construct a myth whereby to perpetuate love indefinitely, it dawns upon them that the feeling of love and happiness is an impediment

to something of equal importance: freedom. Aristotle rejected the notion that there might be another end, aside from happiness, towards which human action tends. Irrespective of Aristotle’s specific conception of happiness, there lies the more basic assumption in his

philosophy that all human action is ultimately directed at its achievement. But the moment of loneliness brings with it a torrent of doubts about the supposedly self-sufficient nature of happiness, which seems at such moments more like some sort of amnesia, self-inflicted to fend off the much feared confrontation of man with himself. Those who embrace this confrontation find themselves in a murkier, mistier region. Citizens of this land are entangled by incapacitating webs of thought spawned by the solitary mind. They defend themselves against the onslaught of happiness, which, they fear, will conceal the essential truth of loneliness and ruthlessly shield them from grappling with their cognitive processes. These processes, they realize, are elusive and only further obscured by language, which presents the attractive but deceiving possibility of clutching a golden kernel of selfhood in the fog. The hope of resolving these webs is consistently squelched by the fear of stating anything with certainty and stamping it with the seal of the finished product. Ex nihilo, the word is born out of sheer willpower and in

These suppressions of feeling are the birth pangs of God and poetry, twin sources of relief during moments of exile.

THE GADFLY FALL 200912

defiance of its futility. Poetry is created from this confusion, allowing these unhappy dwellers to finally pause in their tracks, sit down by a tree stump and etch into the bark, “Here was progress made and the world permitted to venture into new terrain!” That is, until their poetry seems like the spoiled delights of bygone days when they were naïve and believed that language could provide them with clarity. Realizing that it is as far removed from the self as anything else, they once again proceed to pace in the mist.

But although God emerges out of a need for permanent love, and poetry is motivated by an opposing urge, they

stem from a common ancestor, and their kinship is evident. For God, like poetry, is firmly rooted in the misty woods of unstoppable thought. While groping for the self that exists independently of material attachments and semiotic systems, one also stumbles upon God, immaterial and indefinable. At this point man is free of attachment, having tasted the ineffable substratum of the words that comprise his thoughts. He is freer than the poet, for he has transcended language. He experiences the substantiality of nothingness, thereby

allowing for the emergence of an independent, free identity out of the dust of material existence.

In this respect, at least, God surpasses poetry, which can afford the artist a momentary glimpse

into unadulterated selfhood, and might even engage him for a lifetime. But there come the inevitable moments when the

poet, too, realizing that the glimpse was illusory and that his words are indifferent to his plight, must enter the world of attachment. In the imagined confrontation with God, however, there is a detached happiness, bliss intertwined with freedom. What originally seemed like polar opposites do not turn out to be mutually exclusive. Both freedom and happiness, in fact, coexist in the complex experience of God. This experience might not be accessible without the assistance of religion, that edifice of language constructed around God. How could one examine the self without the proxy of language? Even if one rejects the concept ‘God,’ religion might be the key to a desirable

metaphysics in which freedom and omnipresent

How could one examine the self without the proxy of language?

features 13

attachment can coexist. This entails a necessary paradox insofar as one submits to religious belief only to transcend it. There are important moral consequences to this narrative because when freedom and happiness fail to coalesce, one is subject to a divided system. Heroism, as a moral ideal, is

impeded when the search for autonomy and the achievement of happiness remain distinct endeavors. By heroism I mean the perfect devotion to a goal whose pursuit satisfies the hero’s quests for both love and autonomy simultaneously. The free individual might passionately

commit himself to causes with the utmost conviction, but left alone, he cannot help but eventually look back upon his work with an air of skepticism and laugh the grand scheme to ruins.

If the acceptance of a paradox which views religious practice as a self-negating exercise is ultimately

impossible to maintain, the potentially heroic might be forced to accept their splintered ethical lives as they stand and take stock of what they still have. This formulation of heroism, though, will remain unique. It is not an ethics based upon utility or consequences, but unity. It is the ideal expressed in the sentiment, “They that wait upon the Lord shall renew their strength; they shall mount up with wings as eagles; they shall run, and not be weary; and they shall walk, and not faint” (Isaiah 40:31). It is embodied by those who passionately strive long after a tired, worn out sense of rationality would have mandated the kind of self-deprecation that chills the bones. Its source lies in the conviction that even after the gate has closed, a shadow remains tightly knit to the fabric of one’s soul, which pushes him forward with a touch of endless love.

God is born from these evanescent mirages of permanent happiness.

THE GADFLY FALL 200914

Joga e Pensa BonitoDonovan Adriano Toure

Illustrated by Channa Bao

The disconnect between the problems of our age and the stagnant ways in which academia deals with them is only growing more acute. There come moments when a mental

deadweight presents itself to participants of intellectual life. This deadweight owes its existence to the lack of interaction between the problems of daily and academic life. Allow me to explain myself with the help of an analogy. Recently, a similar feeling of deadweight permeated my weekly game of soccer. On that particular day, I found myself focusing too much on technique, and departing from the creative Brazilian style my friends and I grew up playing with. As a result, the team played neither cohesively, nor fluidly. It took the simple words, “Joga bonito,” spoken by a good friend, for me to realize where this deadweight was coming from. The phrase joga bonito, given life by Brazil’s rich soccer culture, is quite unique in its simplicity: play beautifully. It promotes fairness, creativity, and team spirit. It encourages passionate play and individual dynamism. There is room to extend this concept to how one thinks. Academia has become

Each of us must forge a personal style of expression unique to our individual experience.

shorts 15

segmented in our times by a general lack of vitality and connectivity. The promotion of beautiful and fair representation of thoughts, trends and finer feelings is utterly necessary. As thinkers, we must be encouraged to limit particular biases and acknowledge personal limitations. Like players of the beautiful game of soccer, those of us who see the worth of an integrated mind must incorporate fairness, honesty and creativity into our academic pursuits. We must, quite simply, think beautifully.

To be sure, thinking in such a manner involves interdisciplinary and intercultural reflection.

It requires a sociological, moral, and historical imagination. But the element it requires above all must come directly from each individual: each of us must forge a personal style of expression unique to our individual experience. When this style is cultivated by a desire to attain harmony in what is currently a segmented team of ideas, one begins to see the prospects for a more cohesive and prosperous intellectual future. And when these elements are fully integrated in earnest, the result may well be an endeavor that r e s e m b l e s the fluency and cohesion

achieved by Brazilian soccer players—a beautiful language that takes the totality of human experience and feelings into consideration as it moves forward. May we think beautifully in these curious times.

983 AMSTERDAM AVE.(Bet. 108 & 109 Street)

New York, NY 10025

212-222-1775

FREE DELIVERY 24 HOURS/DAYOPEN 24 HOURS/7 DAYS A WEEK

THE GADFLY FALL 200916

People are not passive vessels; they are actors. We feel moved by an oration and run to the voting booth. We feel stung by the sincerity

of a movie and call our mothers in tears. The value of emotions, then, is not chiefly the part they play in subjective experience. It is their ability to induce activity. States of affection can change our behavior, our priorities, and our evaluations. And they do not require our allowing them to do so. The reason we look for great emotion in great works of art, for example, is not the pleasure we derive from them, but the impact they have on our lives.

This is not a triviality. Emotions are crucial to the way in which we make decisions, both in the everyday and when we must weigh the morality of an action. I do not believe that moral facts are best found in our emotional judgment and that to act properly one ought follow one’s sentiments. Rather, I endorse a non-cognitivist approach, primarily through Charles Stevenson’s theory of Emotivism, wherein decisions are not grounded upon a computation of beliefs but upon a non-reason-based influence. What is at stake is not how one acts or how one ought to act but what it means to make a moral decision. But before we get to the decision itself, it is important to understand what is entailed by a moral argument, or even an argument in general. Let us say that Alex and Ben are trying to choose a restaurant for dinner. They both want Chinese food, but Alex believes the restaurant is on Amsterdam while Ben holds that it is on Broadway. This, clearly, is a

A Sentimental Mood: Emotions, Morality, and Truth

Max KaplanIllustrated by Daniel Nyari

features 17

disagreement of fact or belief; the restaurant cannot be on both avenues, and therefore only one of them can be correct in his belief. This is the primary form of argument people consider. However, there is a second form that may prove to be of higher importance.

Suppose the dispute is not concerning the location of the restaurant but rather preference. Alex prefers Columbia

Cottage whereas Ben prefers Ollie’s. Here the facts are clear, but rather the dispute presents a divergence in attitudes. ‘Attitude’ implies evaluation. What makes this type of disagreement so interesting, this discord between positive and negative attitudinal

feelings, is that even after the two break down all the facts of the situation, from cost to location to free boxed wine (thank you Columbia Cottage), they can still disagree

upon the comparable taste of the General Tso’s Chicken. Better yet, they may even agree

as to the nature of the subjective experience of eating the chicken—say both agree that Ollie’s is

greasy—while Ben can still prefer the taste. The point being, the decision will eventually terminate

upon a concurrence or discord of attitude. But who cares about Chinese food? More

likely than not the argument will end with hunger rather than an accord of attitude. Yet this is precisely

what is at stake. The disagreement does not end with the conceding of fact but with an agreement of attitude. At some point the primacy of negatively evaluated hunger will overwhelm one of the participants’ more neutral restaurant evaluations. Every moral argument reaches such a point. A

Emotions affect our attitudes and our attitudes affect our actions. Emotons are not toys we play with, but the tools of the moral systems that shape us.

THE GADFLY FALL 200918

moral argument, by definition, concerns the evaluation of an action as good or bad, right or wrong. Therefore the disagreeing parties hold either positive or negative attitudes towards the action. The decision is ultimately non-cognitive. For any argument involving attitudes the terminating factor, that upon which the decision turns, is how one feels. Attitude becomes primary.

This move should not be taken lightly. It may seem innocuous to say that opinions are relevant in decisions,

but the above discussion is more than a subjective refocusing. Prioritizing attitude demotes belief, as well as truth. If agreement in our beliefs is no longer stipulated for the conclusion of moral disagreements, then there is cause to describe beliefs as instruments of the moralist as opposed to ends in themselves. This is not a mere

reorientation of usage, but a complete questioning of the utility of beliefs.

In the case of the restaurants the same beliefs yielded two distinct attitudes. The implication is a collapse in the standard ‘if-then’ logic, asserting (B^A) (B^¬A), or (i) if B, then A and (ii) if B, then not-A. A logical contradiction appears to be true, but this obviously cannot be the case. Therefore the implicational relation between belief and attitude, namely, that attitudes follow from beliefs, must in this case be denied. It may be asserted that what is actually being considered

is two people with similar, but not identical belief-states—(B^A) (B`^¬A), or (i) if B then A and (ii) if B`, then not-A. This implies that there may be deeper personal beliefs that color these differences, but this is not useful. Two people always hold some differing underlying belief, so to posit this explanation denies any instant of agreement and makes any dispute of fact innocuous. If this difference cannot be articulated then its use in disputes qua belief collapses. I would argue that the ‘belief ’ is an attitude masked as something more grounded.

This is the power of attitudes. At the end of a moral disagreement, in the process of making a decision to act in a particular way, one eventually relies upon how one feels about the action as opposed to what one believes to be true. The statement ‘X is good’ has less to do with X and more to do with how one feels towards X. This is not

to say that what X is does not matter or that a change in belief does not necessitate a change in attitude. What X is does matter; a change in belief does necessitate a change in attitude. The point is that these are secondary to the attitudinal reaction one has towards X. A new belief that Ollie’s chicken is actually bad for your health may

indeed change Ben’s preference, but then that alteration is determined by his attitude towards unhealthiness. This must eventually bottom out to some initial attitudinal attribution rather than a statement of fact.

It is here that we find the value of emotions. One may object that the discussion of attitudes has no relation

to the earlier topic of emotion, or that I have been presupposing one will act from an emotion in the same way one will act from an attitude. Nor would such an objection

In the process of making a decision to act in a particular way, one eventually relies upon how one feels about the action as opposed to what one believes to be true.

features 19

be wrong. Envy will not necessarily lead to some retaliatory action. However, it will make one feel negatively with regard to some object or occurrence. Emotion implies an attitude. To feel happy about something is to hold a positive attitude towards it. To feel depressed is to hold a negative attitude towards life. Emotion is the major informer of attitudinal states.

This, I posit, is the value of emotion, the reason we cherish the elicitation of sentiments. Emotions affect our attitudes and our attitudes affect our actions. This is not to fetishize sensations, though this may be a resulting secondary component. Emotions are not toys we play with, but the tools of the moral systems that shape us.

The value of emotions, then, is not chiefly the part they play in subjective experience. It is their ability to induce activity.

THE GADFLY FALL 200920

Do you think that a world in which 2+2=5 exists?

If you’re asking me whether I think the sum of two and two might have been five, then the answer is clearly ‘No.’ It is a necessary truth that that sum is four. People sometimes get confused about this because they think: “Well, the numeral ‘5’ only conventionally

refers to the number five, so it’s possible that it might have named the number four, and then the sentence ‘2+2=5’ would have been true.” That’s correct. But what’s being imagined there is not a world in which the sum of two and two is five. Rather it’s a world in which

the sentence ‘2+2=5’ just happens to be true because it means that two plus two is four. On the other hand maybe you’re asking me what I think about the metaphysics of modality. I’m not a modal realist; I don’t believe there are possible worlds other than the actual world, so I don’t think that any worlds exist in which actual falsehoods are true. In my opinion that’s the wrong way to cash out talk about

possibility. I think that Al Gore might have been president, had things gone differently from the way they actually went, but I don’t believe that that modal claim is made true by the existence of a possible world in which Gore was president. Possible worlds are a very useful heuristic device for thinking about the semantics of modal logic, but we shouldn’t take them seriously ontologically. Few metaphysicians do accept modal realism, except, famously, my teacher David Lewis. And he really did believe in them! I remember sitting next to him at a dinner at Princeton years ago when Scott Soames leaned across

the table and whispered: “They’re really out there, aren’t they David?” Lewis had consumed a couple of pints of beer by that point, and maybe Soames thought that he’d catch him at a weak moment. No chance! David just beamed back at him and nodded vigorously.

Making Small Talk with John Collins

Stephany Garcia

(i)

Illustrated by Khadeeja Safdar

21criticism

What applications do you think Decision Theory has to a person’s daily life?

I once stood on a street corner in San Francisco—in the rain—for nearly ten minutes in the company of five other decision theorists who had just attended a panel discussion at the West Coast APA Conference. We were trying to figure out which restaurant to go to... I think people can easily get the wrong idea about decision theory. The theory says that in order to be rational we should always be calculating and maximizing expected utilities. Well, no. Like most people, I hardly ever think explicitly in those terms in daily life. At the heart of traditional decision theory is a representation theorem that says: if a person’s preferences over available options satisfy such-and-such axioms, then we can construe that person as a rational agent with well-defined utilities and degrees of belief who is acting so as to maximize expected utility. But that’s not to say that the person in question is using the theory as an explicit algorithm for deliberation. Philip Pettit

has a helpful analogy here: keeping your balance as you walk down the street is, as it turns out, a matter of keeping the fluid in your ear canal level. But that’s certainly not what I’m thinking about when I’m trying to keep my balance, let alone when I’m just walking along the street. That said, there’s a lot of interesting recent empirical work that reveals characteristic and systematic flaws in human decision-making. I’m thinking in

particular of the work of Kahneman and Tversky and their followers. I think it can be very useful indeed, and of great practical importance in daily life, to be aware of the kinds of biases and mistakes to which one may be naturally prone in deliberation. Here’s an example: Owain Evans, who was a major in this department a few years back, wrote a wonderful senior thesis on the “ratio heuristic”: (1) people are more likely to travel across town to save $10 on

(ii)

The nice thing about philosophy is that nobody dies when you make a mistake.

THE GADFLY FALL 200922

a $20 purchase than on a $200 purchase; and (2) people have strong intuitions to prefer humanitarian interventions that save a larger proportion of lives, even when the absolute number of lives saved is no greater. Very imaginatively, Owain wondered whether this tendency might be explained by recent neurophysiological research on the mental representation of number. The gist of this work is that humans seem to share with other non-human animals a very basic sort of continuous or analog system of representation of the discrete natural numbers. We appear to store information about number in a continuous manner, rather than digitally, and that would tend to make ratio comparisons more salient to us than comparisons of absolute difference.

Do you consider yourself a philosopher king, in Platonic terms?

Not at all. I would be a very bad king, and I have never harbored any political aspirations of any kind. I can hardly imagine a role I would be less suited to, except perhaps neurosurgeon. I would be a truly terrible neurosurgeon. The nice thing about philosophy is that nobody dies when you make a mistake.

I do think, however, that the rather depressing cacophony that passes for political debate in this country might benefit from the input of more people with philosophical training. One skill that philosophy teaches is the ability to see what is, and what isn’t, a good reason for believing something. I think the level of political discourse might be improved by the involvement of people who realize, for example, that just because one agrees with the conclusion of an argument doesn’t mean one should think that the argument is a good one.

What has been the most real dream experience you’ve ever had?

I find that I very rarely remember my dreams, and those I do recall on waking tend to be pretty strange. Most real? Well, I once dreamt the solution to a mathematical problem when I was a student. There was an undergraduate mathematics society at Sydney University that went by the happy acronym ‘SUMS’. They had an annual problem competition. I’d spent all evening struggling with a combinatorial problem and had gotten nowhere with it. Then I went to bed and woke up in the early hours of the morning having had a very vivid dream in which I had figured out the solution. I remember being very skeptical of this “dream solution” and I actually got out of bed and walked over to my desk and jotted down just the key step, so I wouldn’t forget it. Then in the morning, to my amazement, it worked! I was completely flabbergasted. I still didn’t win the competition though.

(iii)

(iv)

There is reason to think that time travel to the past would be a very unpredictable and, in fact, a potentially extremely dangerous business.

23criticism

What would be the one thing you’d want to do if time travel were possible?

I suppose this is a sort of disappointing way to answer your question, but to tell you the truth, if I had the opportunity to time travel into the past, I would turn it down, and I would stay well away from the time machine. I gave a talk on this here at Columbia recently called “The Perils of Time Travel.” There is reason to think that time travel to the past would be a very unpredictable and, in fact, a potentially extremely dangerous business. There’s a fascinating 1991 paper in Physical Review by Echeverria, Klinkhammer and Thorne that examines a computer model of a classical billiard ball sent off towards a wormhole on a trajectory that threatens to lead to a paradoxical collision with its earlier self, a collision that would prevent the ball from having entered the wormhole in the first place. Now of course we know that no such thing can happen—time travelers can’t change the past—but what Echeverria et. al. discovered, to their surprise, is that there are always infinitely many ways that such a ball’s history can play out consistently. Most of these involve incredibly fine glancing self-collisions

that change the ball’s course only very slightly, and not by enough for it to miss the wormhole. The worrying thing is that the laws of physics, even if they are assumed to be Newtonian, turn out to be radically indeterministic in such a setting. Deliberate or unconscious attempts to change the past will always fail, but there’s simply no saying what will prevent them from succeeding, and it might turn out to be something very unpleasant indeed.

(v)

THE GADFLY FALL 200924

iblical literalism, which insists upon the literal truth of scripture, is a problem for the secular and religious alike. When

scripture is used literally in public debate as justification for political decisions, we

find ourselves unable to reach consensus on important issues if no alternative secular

reasoning can be found. Similarly, when there is no scientific evidence to reinforce biblical

claims about the world, two serious issues arise. The first is our inability to develop a unified theory about the origins of the world and our species, and the second is the apparent distinction between the evidence presented by God through the

world and through the Bible. Although there is a long history of philosophical biblical

interpretation within the Christian tradition, it has been rejected by fundamentalists as a

danger to the truth value of religious texts, since the meaning of the text may be lost within logical proofs or completely misinterpreted.

Scriptural interpretation has been fundamental to Christianity since Paul, who chose to engage with and interpret the Old Testament

in several of his epistles. In the Dark Ages, however, Christianity fell into a pattern of strict literalism. In Islam, the legitimacy of scriptural interpretation became and continued to be a contentious issue for hundreds of years, and because of this was not completely abandoned. Averroes, for example, successfully used deductive logic and rational philosophy to justify scriptural interpretation in the Koran. He had a tremendous im pact on European thought and his arguments for the reunion of faith

Justifying Biblical Interpretation with Islamic Philosophy

Alyssa LamontagneIllustrated by Leslie Koyama

features 25

and reason paved the way for the renaissance by allowing Christianity the tools it needed to open up to interpretation. As it was in the past, Averroes’ justification of philosophical interpretation may be the best way to address biblical literalism in Christian fundamentalism without dismissing the importance of the text itself. Averroes makes a case for the interpretation of the Koran through a syllogism based on submission to God’s Law, a key aspect of Islam. He argues that the Koran urges us to reflect upon the totality of beings in the universe, since the study of the works of the Artisan leads to a greater knowledge of the Artisan himself. Given that the study of philosophy is a study of the works of God, and if the study of the works of God is obligatory, then philosophy is also obligatory. Likewise, a Christian has an obligation to love God in order to achieve salvation. To love God, the Christian must know God, and to do so must seek to further his or her understanding of God through Creation, and so through philosophy. If that which philosophy teaches us about the natural world conflicts with that which scripture teaches us, we must turn to interpretation.

Many of the tenets of Christianity, however, like that of the Trinity, are founded on faith alone and cannot be rationalized. It

is a common fear of literalists that, should one be open to the possibility of interpretation, scripture will become a slave to philosophy and the truth claim of particular passages will be lost. What they must understand is that scripture always holds an important place in interpretation, and while certain claims may be interpreted, it does not mean that the intrinsic meaning is lost, nor that faith-based claims must be interpreted rationally. Jesus Christ consistently used parables throughout the Bible to help Christians understand God, and yet his meaning was both preserved and understood. We must not assume that the truth value of a particular claim lies in its apparent meaning. If scripture is true, and philosophy also leads to truth and is in fact commanded, then philosophy and scripture must necessarily agree, whether in the apparent meaning or the interpretation.

One of Averroes’ most important observations was that, what appears to be the apparent meaning in many biblical passages is often itself historical interpretation and is not necessarily correct. Decisions on questionable passages that have been made in retrospect are never certain and are open to interpretation. While earlier Christians,

before the Copernican revolution, had very little novelty in their understanding of the world at their beck, we now have a completely radical understanding of the world based on both reason and science. However, we are still stuck in the mud of history, and although much of the Bible is read as timeless and universal, the original interpretation of many biblical passages was within a historical context. Take the claim that women are inferior to men, for instance, which is often supported by scriptural citations. This is not an issue on which scripture is definite, and thus not certain. Such decisions are certainly open to interpretation, and philosophy is the tool.

According to Genesis, woman was created to be a helper to man because it was not suitable for him to be alone. It is Adam

who names her both ‘Woman,’ and ‘Eve,’ just as he names the animals over which he has dominion, which seems to indicate that women are meant to be subservient to men. Literalists often reinforce this claim with Paul’s letter to the Ephesians, in which he claims that wives must submit to their husbands as unto the Lord. What cannot be overlooked, however, is that Paul was engaged in an interpretative project himself. He interpreted scripture based on what reason and common sense told him, but also historically. To find the true meaning of scripture, however, it is important to look at it ahistorically. If one operates from the standpoint that truth is universal and necessary, then it cannot be culturally relative. One must examine whether the claim that women must submit to men

If the study of the works of God is obligatory, then philosophy is obligatory.

THE GADFLY FALL 200926

is historical, or whether it is simply a misguided, modern, liberal value as certain thinkers claim. We must first decide whether woman was created to be an equal or to be a servant. In Genesis 1, however, God creates man in his own image, “male and female he created them.” This is a perplexing passage because it could read that only

man was created in His image, or it could be that ‘man’ in the first part of the passage means ‘human’ and that both are created thus. Reason teaches us that since God is omnipresent, he must not have corporeal properties. If the body is not that which is created in the image of God, then it is quite possible that both man and woman are created in His image. It seems that there is plenty of room for error here, and the biblical literalist may well balk at the possibility of misinterpretation. If we simply assume that what is incorporeal in man is the same as in woman, we may lose the true meaning of the passage. We must then allow scripture to instruct and guide our interpretation, rather than losing ourselves in rationalization.

Perhaps sin is the answer. The fact that, later in Genesis, Eve is punished for eating from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil

seems to prove that she has the same capacity for judgment as Adam. Although when they ate of the tree they did not know right from wrong, God is still very angry at both of them, which tells us that they

must have had the choice whether or not to obey God, and both of

them chose not to. Although they had not yet the capacity for moral judgment, they still had the capacity for reason,

and they both failed. In this way, God considers Adam and

Eve equal. In fact, it is God who administers female submission as a

punishment for the original sin,

telling Eve that her desire would now be for her husband, who would now rule over her (Gen 3:16). “Aha,” says the biblical literalist, here is a direct statement that explicitly claims that men shall rule over woman. This is true, and although one might argue that it literally reads that Eve must submit to Adam, rather than that all women must submit to men, the evidence that the pain

features 27

of childbirth remained seems to indicate that this was a punishment intended for all women. What is missing here, however, is the notion of redemption. In the New Testament, Jesus comes to redeem us from our sin. Indeed, the belief in Christ is even able to subvert death, so that whoever believes in Jesus will have eternal life (John 3:16). This is clear evidence of Jesus’ coming undoing our punishment for the original sin. When a Christian claims that Christ has died to redeem us, why does this not mean all of our punishments? It seems that with time we have been saved from our other punishments: modern medical advances have made painless childbirth possible, and technology has prevented painful toil. Maybe we have already been freed from these punishments and have not yet realized it, or what it means.

It is also possible that the answer to this solution comes from the biblical conception of time. Perhaps what seems

like thousands of years to be redeemed from all our punishments is for God almost instant. If the answer is time, philosophy can also provide a way to reunite biblical time with what we are told empirically, without undermining what the Bible tells us. Indeed, there is a wealth

of contemporary analyses of divine eternity and the relativity of time that make possible the biblical conception of time. Indeed, philosophy is what makes any sort of literalism possible, unless we discount entirely empirical evidence which, unfortunately, some have. This is a dangerous avenue, for to cast doubt on empirical data renders even the possibility

of science highly suspect. This could pose a danger to any future technological, medical, or scientific breakthroughs should this mentality catch on.

Just as Averroes was a precursor of the European renaissance in Christian scriptural interpretation, contemporary Christian philosophy of time comes late with respect to Islam; these are issues that were addressed by Muhammad Iqbal within fifteen years of the advent of special relativity, when the scientific understanding of the nature of time completely changed. It is only within the last half of the 20th century that Christian philosophy of time has really begun to dissect modern scientific and philosophical theories in order to render the biblical conception of time possible. It is certain that Iqbal had a great influence on this realm of interpretation, and we see again how Christians have, in the past, turned to Islamic philosophy in order to better deal with their own.

With the rise of Christian fundamentalism we must continue to draw on the steps made in Islamic

thought as we have done with the philosophy of time to build new Christian interpretations of the Bible. Progress depends on the unity of science and faith, and philosophy is the glue that can bring these two together. Hundreds of years of Islamic philosophy have been dedicated to making this unity possible, and we must take advantage of this as Christianity faces a return to a literalist tradition.

To love God, the Christian must know God, and to do so must seek to further his or her understanding of God through Creation, and so through philosophy.

We are still stuck in the mud of history, and although much of the Bible is read as timeless and universal, the original interpretation of many biblical passages was within a historical context.

THE GADFLY FALL 200928

The Great Neuroenhancer Debate

Brain Gain

Illustrated by Sueminn Cho

In April, the New Yorker published “Brain Gain,” an article covering the abuse of neuroenhancers—drugs like

Adderall and Ritalin prescribed for ADD and ADHD. Unsurprisingly, many of these drug abusers were college students in competiative schools like Northwestern, Harvard and Columbia. The article was not written with any distinct editorial lean, and the question of ethics was left unanswered. The central question of neuroenhancer ethics does not hinge one whether the drugs are “good” or “bad.” Rather, it hinges on who, specifically, should be given access to them. The article found that the primary abusers are educated and grade-obsessed Caucasians of the middle- and upper-class.

This distinct economic bias in favor of the upper class is what sets neuroenhancer abuse apart from other drug abuse. Drug abuse is common to every racial, economic and geographic category; alcohol is the global equalizer. Ritalin, however, is reserved for rich overachievers. Even disregarding every other ethical issue, Ritalin cannot be ethically consumed if it is only available to one socioeconomic group. Only once it is made equally accessible to every economic category can we even begin to consider its other ethical issues. Just consider: an already malnourished, sleep-deprived and debt-ridden college student is probably loath to spend $15 on a pill that she can probably substitute with a $1.50 cup of

coffee and a heap of willfulness.

This is not to say, however, that Ritalin is to be equated with a cup of coffee. Caffeine does extremely

different things to neurotransmitter release in the human brain. Merely having energy is entirely different from the act of forcing concentration. Coffee makes people even more distracted and hyperactive, which is not conducive to paper-writing. Furthermore, coffee and tea, like wine and

cigarettes, are so ingrained in every culture that their use has become completely ritualized. It is hard to imagine this level of ritualization with something like Adderall or Ritalin. Pills are foreign objects and their use is unnerving; none of my friends purchase caffeine pills but instead swig Grande Starbucks drinks, which are far more expensive than the former.

There is another surprising

Julia Alekseyeva

29criticism

statistic discussed in the New Yorker article: neuroenhancers do not make a student a better thinker, only a better accomplisher. The average grade received by a student using neuroenhancers was discovered to be (surprise, surprise!) a B. Remember how many laborious nights of dread and anxiety went into that single wonderful A paper you wrote last year? Probably never would have happened with neuroenhancers. Contrary to popular acclaim, neuroenhancers do not help us think.

There is also a second aspect to this argument: psychologically and philosophically speaking, perhaps

humans need to be spacey to get good ideas. Would Archimedes have pronounced “Eureka!” had he sat unblinkingly in front of a Macbook instead of lounging

in the tub? Anachronism aside, it is pretty doubtful. In terms of psychology, resting states are necessary for internal processing. We are not mentally wired to be in a constant state of perfect attention.

Rather, our natural state is one of detached contemplation. Were neuroenhancers to become the norm, value would be equated with efficiency; humans would be transformed into machines of progress, retrograding back to the progress-oriented Victorian era. The use of neuroenhancers detaches us from the pure poetry of our brain’s natural associations, and from the occasional stroke of brilliance that comes from nebulous and distracted thought.

Ritalin cannot be ethically consumed if it is only available to one socioeconomic group.

It is the year 2020. Over-the-counter use of psychostimulants has been determined safe and effective for

the general public by the Food and Drug Administration. Cognitive enhancers similar to Adderall and Ritalin are available along with Advil and Sudafed at your local pharmacy. Your headache, your stuffed nose, and your complete lack of focus no longer stand between you and your term paper. A small but persistent minority protest the uppers revolution, wasting hour after hour on Facebook, updating

their ineffectual status, posting photo after impotent photo on a laptop screen dimmed to shield relative ineptitude from their peers in possession of intellectual tunnel vision. Intellectual tunnel vision does not amount to a society of drugged-out drones. Like Wikipedia, the graphing calculator, 5-hour Energy Shots, and the plethora of over-the-counter medications, harnessing the power of new technology is not morally compromising, it’s inevitable. I anticipate objections of two general kinds.

Uppers RevolutionAmaryllis Torres

THE GADFLY FALL 200930

First, that some kind of pure human nature or intellect should remain intact, and that certain technologies compromise

this purity. What matters for subscribers to this position is intellectual accomplishment without the aid of external sources. This position, however, would require the rejection of a whole range of advancements in science that fit the bill. Strictly speaking, then, a philosopher with a migraine would not be able to take Excedrin without admitting to an unfair advantage over his headache-ridden pre-pharmaceutical predecessors. In other words, the consequence of this position is a life in isolation from many, if not all, contemporary technologies. Neuroenhancers unlock intellectual potential; they don’t—with

certain restrictions in place—undermine a pure, natural cognitive faculty. The second kind of objection regards the question of inequity resulting from the popularization of cognitive enhancers. But this inequity would be equivalent to—or perhaps much less pernicious than—the

inequity surrounding any modern amenity. The consequences of an unhealthy diet or absent parents for the economically disadvantaged are certainly more severe than that of a less diverse cocktail of pharmaceuticals. Their popularization would more likely alleviate an already existing inequity—that which surrounds current neuroenhancer use. In 2009, the vast majority of adults prescribed psychostimulants are members of the upper classes, not due to any greater prevalence of “Adult ADHD” among the rich.

The position I am promoting requires restrictions enforcing moderation. Over-the-counter sale of neuroenhancers

could be restricted to adults. Each adult could be rationed only a certain number of pills per week. There will always be drug abusers, so an appeal to abuse is as weak as such an appeal to any argument in favor of substance legalization. Legalization coupled with education would

reduce overall abuse of neuroenhancers—and diminish the unfair advantage the small

group of current users (Rx in hand and otherwise) enjoy. At the end of the

day (of course), Aristotle gets the last (three) word(s): moderation, moderation, moderation.

Intellectual tunnel vision does not amount to a society of drugged-out drones.

shorts 31

The Man or the Masterpiece? Thomas Sun

A fire engulfs the Louvre. Fireman Dan Sullivan arrives at the scene, and it becomes quickly apparent: he can either

save the unconscious guard lying on the floor or the painting that the stranger guards—the Mona Lisa. In the aftermath, Dan Sullivan tells reporters, “That was a ferocious fire, but we did our best. It was unfortunate that we could not save the artwork, but ultimately we were able to save the visitors trapped in the museum and the guard on duty.” Reading in the newspaper about what has happened to you is a bizarre experience, thinks Pedro. He’s glad to learn the name of his rescuer, but what catches his eye isn’t Dan’s name, it’s what Dan said: “Ultimately we were able to save the visitors and the guard on duty.” Thank goodness, thinks Pedro! Thank goodness that the ultimate priority of firemen is to save lives, not artworks! Otherwise I wouldn’t be here! But Pedro begins to reflect on the way Dan dismissed the loss of the Mona Lisa, perhaps the world’s most renowned artwork. Maybe it is because he is paid to guard it, but he begins to

wonder: if he were in Dan Sullivan’s place, which would he save? The man or the masterpiece? The painting has come to symbolize so much. Pedro can attest first-hand that it really is an object of admiration for so many. Doesn’t the world stand to lose much more by its disappearance than by mine, thinks Pedro? But why trivialize myself ?! I am worth saving! The value of a human being can never be put on the same scale as that of an object.

But he asks, isn’t this selfish? If society really does have more to gain by rescuing the Mona Lisa, why should my average

existence stand in the way? What is the sadness of a wife and two kids when compared with the betterment of billions? Ha! There are replicas of the Mona Lisa! People will still be able to see it. What’s the original when compared to the life of a man? Though, what if it were not just the artwork in the Louvre at stake—what if it were all the artwork in the world? Would that stack up to my life, thinks Pedro? At this point, Pedro knows that if Dan had to choose between a society without art, without beauty, without masterpieces and a society without one average, middle-aged stranger, Dan would not have chosen Pedro so easily. Indeed, if all the people in the world each made up one pixel of the Mona Lisa, Pedro would not even be visible.

Illustrated by Louise McCune

THE GADFLY FALL 200932

The recent global financial crisis has called into question the utopian vision of an indestructible capitalist machine.

Anarchic uncertainty and thet decay of institutions once deemed impregnable seem to be the rule of the day; worldwide, we observe geopolitical conflict, ecological catastrophe, and economic instability. In the midst of this apocalyptic disorder, Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek offers an unexpected solution in his new book First as Tragedy, Then as Farce: we must simply begin to think critically. Žižek argues that what is needed today is precisely a philosophy of radical emancipation, and that in a world of perpetual injustice we must, to paraphrase Lenin, “begin from the beginning” in constructing a comprehensive theory of anti-capitalism.

Žižek takes his title from Marx’s The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, in which the young philosopher states: “Hegel

remarks somewhere that all facts and personages of great importance in world history occur, as it were, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second as farce.” Žižek argues that the political dream of liberal democracy was shattered first during the tragedy of 9/11, while its economic counterpart, of the dream of rampant capitalism, has similarly been demolished during the farce of the recent financial recession. In this way, the post-1991 celebration of unfettered capitalism and triumphant liberal democracy as “the end of history” collapses under the weight of its own illusions. Žižek describes the reigning, often masked ideology of utopian capitalism and attacks a system that until now has prevailed for decades. He argues that the scope of capitalist enterprise systemically penetrates every facet of our lives, and in order to truly be free we must think beyond the coordinates of the capitalist reality. In the current ideological landscape in which no one seems to be providing rational solutions, Žižek argues that what is needed today is the reinvention of the radical left. Žižek proclaims the rebirth of “the communist hypothesis” and the necessity to reexamine capitalism historically as well as critically, with its brutal, evolving methods of exploitation

Puya Gerami

little philosophy

books

Reinventing Utopia: A Review of Slavoj Žižek’s First as Tragedy, Then As Farce

What is needed today is precisely a reunification of philosophical inquiry with political action.

Illustrated by Gabriella Ripoll

33criticism

in which a society is carved between the “Included” and the “Excluded.” Žižek’s brief book is a paean to the emancipatory project in which the field of philosophy becomes one with “the political.”

But what can philosophy do to solve political dilemmas? Interestingly, Žižek does not seem to provide practical

answers in this book; but as he has stated in the past, “philosophers only redefine false problems.” What is needed today is precisely a reunification of philosophical inquiry with political action, an intellectual bond that has pervaded the humanist project from the Enlightenment through the twenty-first century. And this is a call that pertains not only to the academic subject of philosophy but to all fields; if students can radically reexamine their environment in its totality, and freely question conventionality, then we will be one step closer to becoming active agents in our own history as well as creators of our own futures.

In The 18th Brumaire, Marx writes, “the revolution of the nineteenth century must let the dead bury their dead.” Almost 150 years later, Žižek prescribes a similar argument to confront our own stark political realities. In order to create a world in which we would like to live, Žižek argues, we must be armed with the ability to think radically, and to use philosophy as a means to analyze our history. More than anything, we must permit the dead to bury their dead. Žižek’s message is especially directed toward students; in an age in which capitalism is being shaken on all sides, it is becoming increasingly clear that our primary objective is to voluntarily critique our current social dilemma, and imagine a world that we would truly like to live in. Žižek paraphrases Hegel when he remarks, “We are the ones we have been waiting for!” Shaken from complacency, today it is the responsibility of every student to construct a radically original worldview out of the ruins of an entropic world defined only by exploitative oppression.

www.gadflymagazine.com