Frustrated Hazardous Material: Military and …verses civilian HAZMAT shippers. Though limited...

Transcript of Frustrated Hazardous Material: Military and …verses civilian HAZMAT shippers. Though limited...

Notes and Comments

JILL L. MAYNARDJOHN E. BELLALAN W. JOHNSON

Frustrated Hazardous Material:Military and Commercial Training

ImplicationsThe U.S. Air Force's Air Mobility Com-

mand has been investigating the efficiency ofits cargo movements for decades. In responseto worldwide deployments, the movement ofhazardous materials (HAZMAT)—a categoryof material that ranges from simple cleaningsolutions to the most dangerous munitions—has increased. HAZMAT cargo provided bycommercial firms and destined for overseasmilitary installations often arrives at AerialPorts of Embarkation (APOE) in the U.S.,where they are accepted for shipment throughthe Defense Transportation System (DTS), orbecome "frustrated." Frustrated items includethose shipments arriving at APOEs with miss-ing documentation, incorrect labels, damage, orincorrect packaging (Ellison 2004; Christensen2006). These frustrated items are delayed untilthe commercial firm responsible for the ship-ment can fix the frustration causes. Since al-most every function within the military relieson HAZMAT to complete its mission, an in-crease in frustration levels at APOEs hindersthe effectiveness of deployed troops overseas.In recent years, as the military has increasinglyrelied on commercial sourcing and shippers,its role in APOE frustration levels has become

Ms. Maynard, SM-AST&L, is graduate researchassistant, Capt USAF, Air Force Institute ofTechnology, Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio 45433. Mr.Bell, EM-AST&L, is LtCol USAF and adjunct professorof logistics management, Georgia College and StateUniversity, Milledgeville, Georgia 31061. Mr. Johnson isassociate professor of logistics management. Air ForceInstitute of Technology, Wright-Patterson AFB.The views expressed are those of the authors and do notrepresent the official policy or positions of the UnitedStates Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U.S.Government.

even more of an issue for the Air Force. Thisstudy takes a direct look at the training andprocedures used by commercial shipping com-panies as they ship HAZMAT to the AirForce's aerial ports.

U.S. federal regulations and internationalguidelines that govern HAZMAT shipments—both through the DTS and via commercial ship-pers—are available to the public and are con-stantly updated and published by the U.S. De-partment of Transportation (CFR 49 2006,Labelmaster 2006). In accordance with theseregulations, HAZMAT shipments entered intothe DTS require a trained and certified shipper,proper packaging, and proper documentationupon arrival at the APOB. In 2003, new mili-tary policy established a set of business rulesfor suppliers shipping cargo through the DTS(Wynne 2003). The policy's intent was to re-duce frustration levels at APOEs and ensureon-time delivery of cargo. Unfortunately, frus-tration levels have not decreased in the fewyears since the policy was established, sug-gesting that further changes in either procedureor policy may be needed. The purpose of thisresearch was to help address this problem byexamining whether shipper training proceduresmight be impacting frustration levels atAPOEs.

PREVIOUS RESEARCH

The literature related to HAZMAT transpor-tation is primarily limited to safety (Mejza etal. 2003, Sweet 2006), optihial routing studies(Revelle et al. 1991, Erkhut and Verter 1995,Zhang et al. 2000), and, more recently, studieson security and supply chain disruptions(Sheffi 2001, Russell and Saldanha 2003,

Report Documentation Page Form ApprovedOMB No. 0704-0188

Public reporting burden for the collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering andmaintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information,including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, ArlingtonVA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to a penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if itdoes not display a currently valid OMB control number.

1. REPORT DATE 2008 2. REPORT TYPE

3. DATES COVERED 00-00-2008 to 00-00-2008

4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE Frustrated Hazardous Material: Military and Commercial Training Implications

5a. CONTRACT NUMBER

5b. GRANT NUMBER

5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER

6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER

5e. TASK NUMBER

5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER

7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) USAF, Air Force Institute of Technology,Wright-Patterson AFB,OH,45433

8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATIONREPORT NUMBER

9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSOR/MONITOR’S ACRONYM(S)

11. SPONSOR/MONITOR’S REPORT NUMBER(S)

12. DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY STATEMENT Approved for public release; distribution unlimited

13. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES

14. ABSTRACT

15. SUBJECT TERMS

16. SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OF: 17. LIMITATION OF ABSTRACT Same as

Report (SAR)

18. NUMBEROF PAGES

14

19a. NAME OFRESPONSIBLE PERSON

a. REPORT unclassified

b. ABSTRACT unclassified

c. THIS PAGE unclassified

Standard Form 298 (Rev. 8-98) Prescribed by ANSI Std Z39-18

2008 NOTES AND COMMENTS 31

Kleindorfer and Saad 2005). Also, rail trans-portation has specifically been an area of re-search interest for chemical and HAZMATtransportation (Young et al. 2002, Closs et al.2003). However, only one study could be foundon the hazardous materials training differencesby shippers (Rothwell et al. 2002) and noknown work has looked at the occurrence andcauses of frustrated HAZMAT shipments inthe Defense Transportation System. Therefore,with funding from the Air Force Institute ofTechnology, a line of research was begun in2004 to investigate frustrated HAZMAT ship-ments in the DTS. In the initial study, Ellisontracked the impact ofthe Government PurchaseCard program on frustration levels, identifyinga lack of communication between the militarymembers ordering the items and the civilianshipper about DTS transportation requirements(Ellison 2004). Next, Christensen sought toidentify the main reasons for frustration atCharleston and Dover Air Force Bases and tocompare cargo frustration procedures at thetwo locations (Christensen 2006). He notedthat the respective military customer servicessections had different management styles forhandling frustrated hazardous cargo. Onewould fully require the shipper to fix all prob-lems, while the other would actually make mi-nor corrections after speaking to the shipper toexpedite the process (Christensen 2006). Addi-tionally, Christiansen's research noted thatboth military and commercial shippers werethe source of frustrated HAZMAT at the aerialports; however, the reasons for frustration var-ied, with the military shippers' causes beingmostly "Missing Documentation" and "In-correct Regulation References," and civilianshippers' reasons being mostly "Incorrect Cer-tifications' ' and lacking the shipment ' 'Trans-portation Control Number" (TCN). Thesefindings seem in contrast to the findings ofRothwell et al. (2002), who found no signifi-cant difference in the knowledge of militaryverses civilian HAZMAT shippers.

Though limited research previously investi-gated the effects of a shipper's training pro-gram on its customers, there is significant re-search on training effectiveness. Kirkpatrick's1959 four-level model evaluated Reaction,Learning, Behavior, and Results components toassess the effectiveness of training or teaching

programs (Kirkpatrick 1996). Additionally, arecent study has shown that unless a company'straining program is aligned with its depart-ments' goals, the training is a waste of em-ployee time and company money (Clark andKwinn 2005). Researchers developed sevenroutes through which companies can ensureeffective training programs, each of whichhighlights the importance of direct contact be-tween the training manager and the company'supper and departmental management. Under-standing a company's needs ensures that em-ployees acquire the necessary training to meetthe company's goals (Clark and Kwinn 2005).

In addition to choosing appropriate trainingprograms, it is important to ensure the providedinformation is retained. In 1992, Ford and hiscolleagues investigated how students retainedinformation, and found that retention was af-fected by the number of opportunities a studenthad to perform the learned activity and theactivity's level of difficulty (Ford et al. 1992).They also concluded that task performance re-quires both knowledge and a level of self-effi-cacy (Ford et al. 1992). Thus, while a trainingprogram may be adequate, resulting perform-ance may not be (Ford et al. 1992).

METHODOLOGY

This research investigated how commercialshippers train their employees to ship HAZ-MAT through the military and commercial air-lift systems, with the goal of determiningwhether training practices at commercial haz-ardous material shippers affect frustration lev-els at APOEs. There are numerous hazardousmaterial shippers within the United States;therefore, a multiple case study method wasused to develop logic replication and providemore meaningful findings (Yin 2003). The firststep in the case study methodology (Creswell1994; Yin 2003) was to develop a list of ques-tions and standards of comparison that wouldbe used to draw the individual cases into acohesive framework. We formulated two re-search questions to address this first stage ofthe case study process, and addressed them byresearching commercial and military regula-tions, including intemational guidelines fromthe Department of Transportation, Departmentof Defense, United Nations, and other interna-tional organizations. These two research ques-tions are as follows:

32 TRANSPORTATION JOURNAL™ Winter

Table 1. Factor-Level Explanations

Factors Levels

Number of EmployeesCompany VolumeTraining Program

Large > 100Large > 100Internal

Small < 100Small < 100External

1. What significant differences exist in theway military and commercial shipper per-sonnel are trained on how to ship hazard-ous cargo?

2. What are the training requirements forcommercial shippers to ship within thedefense transportation system?

The data collected during this portion of thestudy, summarizing the regulations that governhow HAZMAT items are shipped via the DTS,were used as baseline requirements for the idealtraining program, and to develop a comparativechecklist for data collection.

Our second step in the multiple case studymethodology was to compile and organize apool of shipper companies for analysis. Weobtained a list of 100 shippers that had at leastone piece of HAZMAT frustrated at eitherCharleston Air Force Base, SC or Dover AirForce Base, DE between August 2005 and Au-gust 2006 (Eidsun 2006, Simmons 2006). Thislist provided data on the number and type offrustrations recorded for each firm. The ship-pers were organized into a 2^ factorial experi-ment design, categorizing them by size, vol-ume, and training method, as shown in Table 1.

The final step in our multiple case study wasto select shippers for interviews and collectdata for analysis and comparison. We usedtwo additional research questions to guide datacollection and analysis, in accordance with thebaseline training program requirements estab-lished from research questions 1 and 2:

3. What standardized guidelines (instruc-tions or checklists) are established forthe shipper for completing the shippingdocumentation prior to shipping to themilitary APOEs?

4. If not standardized, how would establish-ing better guidelines for military and/orcommercial hazardous cargo training re-duce documentation frustration levels atthe APOEs?

We collected the data through telephoneinterviews with the training managers at quali-fying shipper companies using a standardizedlist of questions developed from the compara-tive checklist. We also used the interviewsto elicit each shipper's overall approach totraining. Data included training methods,unique characteristics used to keep employeesinformed, and the interaction between theshippers and the APOE Customer ServiceSections.

For this research, we assigned an alphabeticcode to the interviewed shippers to maintainanonymity. After the interyiews were com-pleted, we realigned the shippers with theirfrustration habits for further analysis and todraw conclusions about each shipper's train-ing practices. We compared each shipper'sprogram to the Department of Defense stan-dards and then against each other. The shippertraining programs were evaluated by typealong with their ability to comply with Depart-ment of Defense and Department of Transpor-tation standards. Our cross-sectional analysisof the cases investigated common areas ofdeficiency and identified best practices.

In exploratory case study research, con-struct validity, external validity, and reliabilityare critical to the production of factual results(Yin 2003). We developed construct validityby working with subject matter experts andtechnical advisors. We established externalvalidity by using currently operating shippersthat have shipped HAZMAT to APOEs withinthe last year. Reliability, which allows subse-quent researchers to use the same tactics asprior investigators to reproduce the same casestudy, was achieved by using simple, thor-oughly documented procedures that could bereplicated with proper approval. We believethe results are generalizable to other militaryAPOEs since the list contained 100 shippersacross the United States, which reflects abroad sample of those shipping to the APOEs.

2008 NOTES AND COMMENTS 33

The scope of the research is limited toshipper companies that have shipped frus-trated HAZMAT through either Charlestonor Dover Air Force Base within 2005-2006,excluding other APOEs. Only shipper names,numher of frustrated items, and reasons forfrustration were available to the study. It wasassumed that each shipper appearing on thelist with frustrated cargo during the researchtime period shipped at least one piece offrustrated HAZMAT through an APOE annu-ally. An extended research time period couldreveal that a shipper's effectiveness over sev-eral years is greater than indicated in thisone-year study. Additionally, shippers havethe option of sending employees to a govern-ment-conducted HAZMAT training program.Our study was limited in scope to the evalua-tion of the shipper's training plan, and did notaddress the training plans of any governmenttraining facilities. Our objective was to ensurethat the shipper was obtaining the requiredtraining for its employees.

Other research limitations arose in the inter-view process. We used telephone interviewsdue to budget and time constraints, while on-site interviews may have provided greaterinsight and more opportunity for collectingsecondary data. Another limitation was con-firming that we indeed spoke to the mostknowledgeable HAZMAT training manager,and it had to be assumed that all statisticsand data provided by the interviewee wereaccurate. Our interviews also revealed thatthe listed data provided by the APOEs, whileassumed to be current and accurate, mighthave also included rare instances where pa-perwork was correct but the cargo was acci-dentally frustrated. We made every attemptto verify that the shippers interviewed hadactually incurred legitimate HAZMAT ship-ment frustrations.

HAZARDOUS MATERIALS PROCEDURES

Commercial shippers and government agen-cies abide by numerous HAZMAT regulationsdepending on the affected government agencyand mode of transportation. Since our researchfocused on the transport of hazardous materialsto overseas locations via military airlift, weinvestigated the training requirements for themovement of HAZMAT by air.

Department of TransportationThe Department of Transportation has estab-

lished the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR)Title 49, Subpart H, Part 172, for U.S. hazard-ous materials training requirements (CFR 492006). Under this regulation, the material ship-per is responsible for training its employees intheir respective areas of hazardous materials.The shipper has the option to train employeesin-house or send them to an external program;however, it is ultimately the shipper's responsi-bility to ensure that its employees meet trainingstandards (CFR 49 2006).

The U.S. Department of Transportation Website provides links to firms qualified to provideexternal training. These firms provide a widerange of services and can be divided into twocategories: location or in-house training. Loca-tion training requires shippers to send employ-ees to a training facility. The Department ofTransportation also sponsors classes at theTransportation Safety Institute, located inOklahoma City, OK, which provides initial andrefresher training courses. The courses spanthree days, with an optional fourth day thatfocuses on military airlift requirements(Kramer 2006). In-house training is conductedby a hired professional at the shipper's location.The hired professional uses their own trainingprogram to train the shipper's employees tothe requested specifications.

Shipper employees can also receive internalHAZMAT transportation training provided bytheir respective company. Instructors work forthe shipper and teach from an established train-ing program. The instructor does not need toattend formal training classes; however, it iscommon for instructors to have attended anexternal training class (Kramer 2006). Anotheroption is to procure a training plan through anexternal training firm. Several external trainingfirms sell computer-based programs and videosto train shipper employees, such as LabelMas-ter and SafetyVideoDirect. These materialsallow shippers the flexibility to train employeesprofessionally without incurring added person-nel costs (Labelmaster 2006, Safety).

Shippers that ship hazardous materialsthrough the DTS must also be trained on dutiesrelated to military air transportation (AFMAN24-204 2004). Additionally, the training must

34 TRANSPORTATION Winter

support the business rules set forth by the Un-der Seeretary of Defense (Wynne 2003).

Department of DefenseThe Department of Defense provides HAZ-

MAT training to military personnel and de-fense civilian employees at five designatedsites. The training requirements are agreedupon in the Interservice Training Review Orga-nization Task Group on Hazardous MaterialsTraining Memorandum of Understanding (AF-MAN 24-204 2004), The same training planis used at each location to ensure cohesivenessthroughout the different military branches. Cer-tifying officials, those responsible for ensuringdocumentation and packaging is correct priorto shipment, represent the standard to how theshipper's employees should be trained. TheDepartment of Defense recognizes three typesof certifying officials (AFMAN 24-204 2004):

Preparers - employees trained on all HAZ-MAT, allowing them to review and signHAZMAT documentation prior to an itembeing accepted into the DTS, They are theoverall trainer for personnel at their instal-lation.

Technical Specialists - These people certifyonly the hazardous materials they are quali-fied to maintain. They are trained by a pre-parer and identified by the Commander torepresent a particular unit. Technical spe-cialists can certify materials only for tacti-cal/contingency operations and routinecargo movement.Medical Personnel - People that handleand ship laboratory samples and specimens.Available only to them, the associatedcourse encompasses all modes of transport.

The three types of certifiers work togetherto ensure that personnel handling, packaging,and shipping hazardous materials are familiarwith requirements. The individuals that certifyhazardous materials are typically rotated in andout of the position; however, their training isspecifically intended to prepare them for thisduty.

International Civil Aviation Organization(ICAO)

ICAO is comprised of delegated membersthat develop standards of intemational air navi-gation and encourage planning and develop-ment of future endeavors (Wells and Wensveen

2004), Additionally, ICAO agrees upon ship-ping standards and practices involving HAZ-MAT. These guidelines are updated yearly andpublished in Technical Instruction for the SafeTransport of Dangerous Goods by Air (ICAO2006).

International Air TransportationAssoeiation (IATA)

IATA members are nominated by individualairlines and are governed by an elected execu-tive committee (Wells and Wensveen 2004).IATA publishes the Dangerous Goods Regula-tions yearly. This publication outlines the re-quirements and procedures for companies ship-ping hazardous items (IATA 2005).

Training RequirementsThe different governing agencies have a

wide spectrum of training policies and pro-grams. Although it is the employer's responsi-bility to ensure employees are trained to speci-fication, Table 2 summarizes the similaritiesand differences among the respective agencies'requirements.

DATA ANALYSIS

During our data collection process, weidentified several observations and obstacles.First, the Air Force currently does not havea central database that records the shippersthat experience frustrated HAZMAT at theAPOEs. There are a few information systemsavailable that list the reasons why a particularHAZMAT shipment was frustrated at eachAPOE; however, consolidated database useis not mandatory for either Department ofDefense or commercial shipper frustrationsin the DTS. Because of this limitation, thestudy could not determine the total amountof HAZMAT cargo that a particular companyships to a particular APOE during a set timeperiod. This lack of tracking and visibilityalso impacts the ability to manage and respondto frustration instances, and a recommendationof this research is for the DoD to assign aresponsible organization to track HAZMATfrustrations and initiate management actionrelated to DTS HAZMAT frustration trends.

Next, the lists obtained from the respectiveCharleston and Dover AFB Customer ServiceSections identified 100 shipper names and

2008 NOTES AND COMMENTS 35

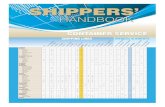

Table 2. Regulation Requirements

Requirement

General familiarizationLimitationsGeneral requirements for shippersList of dangerous goodsGeneral packing requirementsPacking instructionsLabeling and markingShipper's Declaration and other relevant

documentationAcceptance proceduresStorage and loading proceduresTraining recordsFunction specificSafety trainingEmergency responseSecurity trainingTest for competencyInitial training requirements

Refresher training

DoD

XXXXXXXX

XXXXXXX

80%Prior to

certification2 years

CFR 49X

XX

XXXXX

70%Within 90

days3 years

IATAXXXXXXXX

XXX

XWithin 90

days2 years

ICAO

XXXXXXXX

XXX

XWithin 90

days2 years

reasons why their particular HAZMAT ship-ment was frustrated. We discovered that notall the listed shippers were readily contactabledue to missing or incomplete contact informa-tion; this constraint removed twenty-six ship-pers from the list. Additionally, we excludedfive shippers due to their geographic locationoutside the United States—although intema-tional shippers recognize ICAO and IATAregulations, enforcing U,S. defense regula-tions on a foreign commercial companies wasfelt to be outside the scope of the currentresearch. Additionally, a small number ofshippers refused to participate in the studydue to company policy on providing informa-tion, thus excluding six more firms from thelist. In sum, the original list of 100 companieswas reduced to sixty-three companies whohad at least one frustrated shipment. Fromthis reduced list, we sought to contact a mixof hazardous material shippers that wouldbalance the Table 1 research design. Fromthe sixty-three companies, a total of fourteenfirms both fit the experiment design and werewilling to participate, for a response rate of22 percent.

The original criteria used to separate theshippers into the Table 1 design had to bealtered slightly following data collection. The

company volume originally separated shippersinto large and small classes by the amountof cargo they sent out monthly. However, inmany cases the interviewees were unable toaccurately determine the amount of hazardouscargo shipped by their respective firmsthrough the DTS, Although we attempted tocontact other shipper employees to obtainan accurate volume, data were not alwaysavailable. Since approximations were givenby the interviewees, we elected to use thoseestimates as a basis for separation. Thereforewe considered a shipper "large" if it had100 or more employees and if it had morethan fifty HAZMAT shipments per month.Table 3 categorizes the firms interviewed.

Using information collected in the inter-views, we analyzed the training program ofeach shipper while addressing each of thefour research questions. The companies' an-swers to each research question provide abetter understanding of how commercial ship-pers use military regulations and train theiremployees to ship hazardous materials. Inaddition, they show the differences betweencompany practices and lead the study tomaking recommendations for improved HAZ-MAT transportation practices. The next sev-eral sections describe the results of the study.

36 TRANSPORTATION JOURNAL™ Winter

Table 3. Interviewed Companies

Number ofEmployees

LargeLargeLargeLargeSmallSmallSmallSmallSmall

CompanyVolume

LargeLargeSmallSmallLargeLargeSmallSmallSmall

TrainingProgram

ExternalIntemalExternalIntemalExtemalIntemalExtemalIntemalIntemal

GovernmentContract

YesYesYesYesYesYesYesYesNo

Company

D,E,MC,G,KL

IAB,J,NFH

RESULTS

Research Question 1 - CommercialShipper versus Military HAZMATTraining

Air Force Manual 24-204 establishes guide-lines for how the military will train their haz-ardous materials personnel. Five designated lo-cations are used to train military personnel, aslisted in AFMAN 24-204. The curriculum isagreed upon by the Hazardous Material Train-ing Working Group, which meets annually andmaintains an inter-service memorandum of un-derstanding that establishes the mandatoryminimum training requirements to ensure con-sistency across the different branches of service(AFMC/LSO 2007). The CFR 49, IATA, andICAO regulations state the training require-ments for individuals certifying HAZMAT.

We asked the fourteen interviewed shippersquestions about their training program. Table 4provides a general overview of each respectiveshipper's training programs and practices.

U.S. commercial firms are obligated to fol-low CFR 49, which requires them to ensuretheir employees are trained within ninety daysof employment, meet the established guide-lines, and can pass a standardized test with aminimum 70 percent score.

Shippers B, D, E, I, J, L, M, and N usean outside agency to conduct their training.Shippers B and I indicated that they selectedextemal training firms because it was inexpen-sive and convenient. Also, Shipper B chosea company that trains on DTS requirements.Shippers D and E choose the external trainingprogram at random when their employees aredue for training. While Shipper L recertifiesits employees per the CFR, which is every

three years, versus the intemational two-yearstandard. Shipper J chose its extemal trainingprogram based on reputation, while Shipper Nemployees are trained by the shipper firms theyuse. Lastly, Shipper M chose a strict extemalprogram, where employees use exportablecourses that require them to pass a test with a75 percent or better at the end of each section.Even though these firms each chose an externalprogram, they receive the training in a differentmanner.

Shippers A, C, F, G, H, and K developedtheir training programs intemally. However,the instmctors from Companies C, G, and Kreceived their training certification from an ex-ternal training company. Additionally, Com-pany A uses an outside agency to conduct train-ing for its medical personnel. Company F and Gdo not have a standardized test their employeesmust follow; however. Company G is devel-oping a monthly refresher course for its em-ployees and Company F is implementing a test.Company G sends its employees that handlemilitary orders to an external training companythat encompasses DTS regulations. CompanyH hires a contractor to fulfill its shipping re-quirements and the company is responsible forall of its training needs. The end-of-course testfor Company K must be passed with a 70 per-cent or better; however, the trainer makes em-ployees that miss four or more questions retakethe course. Each of the companies developedcourses from the regulations and the informa-tion gained from the extemal courses their in-stmctors attended.

Even though the training methods for themilitary and commercial companies vary

2008 NOTES AND COMMENTS 37

Table 4. Shipper Training Programs

Company

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

MN

TrainingProgram

Internal

External

Internal*

External

External

Internal

Internal*

Internal

External

External

Internal*

External

ExtemalExternal

Reason for type oftraining

Small company

Outside company mettheir needs

Large number ofemployees to train

Used for years

Encompassed all therequirements

Numerous personnel

Outside contractorworking for largerorganization

Price and a smallcompany

Good relationship withtraining company

Close and goodreputation

Prior individual chooseSmall Company

Location

Classroom/on-the-job

On-site/classroom

Classroompresentations

On-sitetraining

Off-sitetraining

On-the-job

Classroompresentations

Classroompresentations

On-line

On locationand off-site

Classroom andon-the-job

Off-site

On-siteOff-site

Test Requirement

80%

Decided by trainingcompany

75% or better

Decided by trainingcompany

Decided by trainingcompany

Test not developed-estimated Jan2007

No standard- hasmonthly refresher

70% or better

Decided by trainingcompany

Decided by trainingcompany

70%

Decided by trainingcompany

75%Decided by training

company* The trainer and some employees were trained externally

greatly, the documentation and testing require-ments are similar. Both the military and com-mercial industries must keep a training folderon each individual trained. It must includethe individual's name, the location of thetraining, the type of training, and a completedtraining certificate (CFR 49 2006; AFMAN24-204 2004), Commercial industries are re-quired to keep training documentation onhazardous materials only, whereas the militaryrequires the member to keep documentationon all training courses. The military andcommercial industry both require a standard-ized test to be given at the end of the training,but the military also requires a member topass two tests with a 75 percent or betterbefore they are certified (MOU 2002). Thecommercial industry's standardized test mustbe passed with a 70 percent or better, but it

does not appear from our research that thisis strictly enforced. These aspects are theonly common thread between the militaryand commercial industries' training programs.

The information outlined above indicatesthere are significant differences in how themilitary and commercial industries train theirpersonnel. The military uses a standardizedcurriculum, while commercial companies usea variety of methods to base their curriculumon the military regulations. The emphasis inthe commercial training industry is gearedtoward the proper handling, security, andsafety of the hazardous materials, while littleemphasis is placed on shipping documenta-tion. The military trains on the safety andsecurity of HAZMAT as well, but also strictlyaddresses the proper way to complete thedocumentation. The difference in training and

38 TRANSPORTATION JOURNAL™ Winter

requirements leads us to investigate the nextresearch question.

Research Question 2 - CommercialShipper Training Requirements

The requirements for commercial industrypersonnel to ship hazardous cargo through theDTS are outlined in AFMAN 24-204. SectionA25.7 of AFMAN 24-204 explains that all non-DoD personnel preparing and shipping hazard-ous cargo through the DTS must do so ac-cording to the regulation (AFMAN 24-2042004). A specific number of annual trainingslots or "billets" are allotted to each of theDoD training facilities. The billets are thenrequested by a government agency for employ-ees that require certification. A commercialcompany can request that its employees be sentto a defense-sponsored course; however, theymust request a slot through the governmentcontracting office that oversees their work (345TRS 2007).

The companies interviewed knew of the es-tablished military training requirements. Com-panies B and F had taken an extra step andreceived additional training that meets militaryrequirements, while Companies G and D hada separate department within the company thathandled military shipments. Companies B, E,and F shipped 50 percent or more of theirHAZMAT to a Defense Logistics Agency(DLA) center. Company F stated that DLApersonnel actually completed all the HAZMATdocumentation for them, and that their com-pany shipped only a small percentage directlyto an APOE.

Commercial companies that ship HAZMATthrough DTS aren't held to the same trainingstandards as military personnel, but they arerequired to follow the same regulations. Addi-tionally, all of the companies had a governmentcontract that obligates them to abide by thedetails and responsibilities agreed to in theircontract. Since the companies interviewedwere located across the United States, we didnot have sufficient resources to review eachrespective contract. Five of the interviewedcompanies were making an attempt to abideby the military regulations; however, activeparticipation is needed by all commercial com-panies to reach success.

Research Question 3 - ExistingStandardized HAZMAT Guides

Some of the documentation required by themilitary is similar to the commercial sector;however, there are specific guidelines that needto be followed when completing them. TheShipper's Declaration is used by both sectors,but the military's document is arranged in adifferent format and is not accepted unless itis properly completed. Some differences seemtrivial—for example, the military requires thatthe proper shipping name be typed in all capitalletters. The packaging paragraphs are also dif-ferent: The commercial industry follows IATApackaging paragraphs that are separated byweight, while military packaging paragraphsare separated by container type (IATA 2005;AFMAN 24-204 2004).

The military also requires that a militaryshipping label (MSL) accompany shipments.This label contains the shipment's receivingorganization, the shipping company's informa-tion, and the transportation control number(TCN). This label should be placed on the out-side of the package and should be easily identi-fiable. Although all this information is con-tained elsewhere in the shippingdocumentation, it is required in case a smallerpackage is separated from a larger shipment.

Commercial industry can obtain militaryregulations through the Air Mobility Com-mand, Air Force Material Command, or De-partment of Transportation Web sites. Table 5demonstrates which items assist the companiesin completing military documentation.

Five interviewed companies were unawarethat the regulations could be accessed; how-ever. Companies F and K kept the shippingdocumentation from previous shipments to useas references. Table 6 displays the number offrustrated hazardous shipments each companysent to the APOEs.

On first glance it appears that the fivecompanies not using the regulations had theleast amount of frustrated cargo. However,due to lack of data on the total volume ofcargo shipped yearly by each company, broadassumptions should not be made. Note thatCompany F reported a majority of its ship-ments' documentation were completed byDLA personnel. Therefore, it is unclear ifCompany F is to blame for discrepancies

2008 NOTES AND COMMENTS 39

Table 5. Regulation Use

Company

Aware ofRegulation

AccessDo Not UseRegulations

Phone DoDinstallations

On-lineRegulations

MilitaryRegulations

On-Site

ABCDEFGHIJKLMN

YesYesYesYesNoYesYesYesYesYesNoNoNoNo

XX

XX

X

X

XX

XX

X

Table 6.

Company

Reasons for

Unknown Reason

Frustration

Shipper'sProper Shipping

Name

DeclarationPackaging No TransportationParagraph Controi Number

No MilitaryShipping Label

Missing

APOED=Dover C=

Charleston

ABCDEFGHIJKLMN

1

11

101

1*

1*1

2*

1

12*

1*

DC

C/DDCDDCDDDCDD

* Indicates one or more shipments had multiple problems

or if DLA should be held accountable. Fordocumentation purposes, the APOE customerservice sections would attribute the frustrationto Company F because it is listed as theshipper.

Most companies interviewed were awareof the military shipping requirements and amajority of the companies were aware ofthe reference material. Some companies evenchose to contact the APOE or DLA locationdirectly for assistance. Although the bestmethod cannot be determined, it is clear

that commercial companies have opportunitiesavailable to complete the documentation cor-rectly.

Research Question 4 - Standardizing theGuidelines

The study found that there is no single gov-erning body for the commercial industry thatinvestigates training practices. Eight of thefourteen companies had recently been in-spected by the U.S. Department of Transporta-tion; however, they were inspected in other

40 TRANSPORTATION Winter

areas of operation. Two companies had beeninspected by the Federal Aviation Administra-tion on their shipping procedures and one com-pany was inspected by a defense employee toensure it was abiding by its contract. Eventhough several governmental agencies had vis-ited the companies, their HAZMAT trainingprograms were never investigated. The U.S,Department of Transportation and DoD needto establish procedures for standardization, in-spection, and enforcement of HAZMAT train-ing requirements.

The second area that needs standardizationattention is documentation. Currently, theShipper's Declaration is required for both com-mercial and military shipments, but is com-pleted differendy for each. Our discussionswith AF headquarters personnel (who are re-sponsible for authoring AFMAN 24-204) indi-cated that the new standards for the militaryShipper's Declaration, which will be pubhshedin 2007, now duplicate those of the commercialindustry. The revised Shipper's Declaration hasrecendy been put into circulation, and the newrevision of AFMAN 24-204 regulation is tobe distributed late in 2007, making the formmandatory (AFMC/LSO 2007), The effects ofthis change may not be seen for months, butit is a step in the right direction. The secondcommon documentation error is a missing mili-tary shipping label, but it is believed thatthrough proper training this can be easily alle-viated.

The fourth research question cannot be an-swered completely without further investiga-tion into the procedures and policies of severalother governmental agencies. These govem-ment agencies produce HAZMAT regulationsthat govern the military and commercial indus-tries, but it appears there is litde unity acrossthese agencies. The U.S. Department of Trans-portation and the Department of Defense needto work closely together on hazardous materi-als shipping policy and procedures, and it ap-pears that communication between these twoorganizations still needs to be improved.

BENCHMARKING FOR SUCCESS

Our research investigated how well compa-nies met the hazardous material shipping stan-dards established by the U.S, Departments ofDefense and Transportation. Although some

companies were more successful than others,no single company did it perfectly. However,there are a few key practices that could beduplicated to improve a company's chances ofsucceeding. We used Spendolini's (1992) five-stage generic process to find best practices dueto its easy adaptability and use of establishedguidelines. Our research revealed five thingsa company can do to decrease the amount offrustrated cargo shipped to an APOE:

1, Acquire and become familiar with mili-tary regulations and acronyms.

2, Have a set of individuals that routinelyprepare military shipping documents.This ensures familiarity and reduces addi-tional training,

3, If problems arise and no answer can befound, contact the military APOE that isto receive the cargo and ask for clarifi-cation,

4, If the company has a government con-tract, ask the associated govemment con-tracting office for a tour of the APOEto become familiar with the acceptancerequirements,

5, Ask the government contracting officefor a personnel training slot to take theexportable HAZMAT course offered byone of the five designated military loca-tions, or if negotiating a contract be sureto specify that a certain number of com-pany employees will need to attend a mil-itary training course.

These five steps can improve a company'ssuccess rate when shipping HAZMAT to anAPOE. Companies shipping HAZMAT to anAPOE need to understand the stringent guide-hnes the military follows and be willing tocomply with them.

SUMMARY

Our research examined how commercialcompanies train their employees to ship haz-ardous materials in the Defense TransportationSystem, The research questions investigatedthe APOE cargo fmstration levels for a groupof commercial companies. Overall, no two ofthe interviewed companies handled govern-ment shipments the same way, and their train-ing plans had only a few similarities; therefore,all the employees likely have a different under-standing of the proper way to ship hazardousmaterials to DoD customers.

2008 NOTES AND COMMENTS 41

Our first two research questions investigatedthe training requirement differences in the mili-tary and commercial companies. First, it wasfound that military and commercial trainingpractices and curriculum vary significantly.Military training is fully standardized whilepaying close attention to required documenta-tion. In contrast, commercial training uses avariety of methods aimed more at cargo han-dling and safety and security concerns. Ouranalysis discovered major differences; how-ever, each party appears to be abiding by theirrespective regulations, with the exception ofCompany F and G. Unfortunately, it was dis-covered that five of the fourteen companiesinterviewed were completely unaware of theneed or ability to access the required militaryregulations that govern transporting hazardouscargo in the DTS. Our third and fourth researchquestions established that AFMAN 24-204provides the guidelines for completing HAZ-MAT documentation transported through theDefense Transportation System. A major ad-vancement is that the new version of AFMAN24-204 will more closely align required mili-tary shipping documents to those used by thecommercial industry.

The curriculum taught to military membersis the same at each defense training facility,thus ensuring that standardized procedures arefollowed. Similarly, we recommend that theU.S. Department of Transportation develop astandard curriculum for commercial companiesto comply with, to ensure hazardous materialsemployees are properly trained. By developinga standard curriculum, the DoT would alsohave a better way of inspecting commercialcompanies. Currently, there appears to be alack of coordination between governmentagencies and no single governing body appearsto be standardizing, inspecting, and enforcingHAZMAT transportation training practices.The existing inconsistency creates shippingdiscrepancies, uninformed decisions to bemade, and delayed shipments destined for over-seas military customers. An additional recom-mendation is the establishment of a commondatabase of HAZMAT frustration statistics bythe DoD. Currently, it is difficult to measure themagnitude and trends of HAZMAT frustrationoccurring at the APOEs and future researchwould gain greatly from historical tracking of

the number, volumes, and discrepancies ofHAZMAT shipments at all APOEs.

In conclusion, since commercial companiestrain their employees to different standardsthan the military, a good bet is that commercialshipper employees have incomplete knowledgeof the shipping requirements through the De-fense Transportation System. Commercialshippers have access to military regulations butmay not fully understand the rigidity of themilitary requirements, and currently there is nocohesive link between the military and com-mercial industry to assist them. Although theassociated government contracting offices actas liaisons, they are not subject matter expertson HAZMAT transportation requirements. Inconclusion, commercial shipper training forhazardous material appears to impact frustra-tion levels at military APOEs, and until govern-ment regulations and guidelines are establishedthat provide a common language for the mili-tary and commercial industry, this trend willcontinue.

REFERENCES345th Training Squadron Instructor, Lackland Air

Force Base, TX. Personal communication, February 2,2007.

Christensen, N., Hazardous Material Cargo Frustrationat Military Aerial Ports of Embarkation. Unpublishedmaster's thesis. Air Force Institute of Technology, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, OH, April 2006.

Clark, R. and A. Kwinn,' 'Aligning Training to BusinessResults," T +D, Vol. 59, No. 6, 2005, pp. 34.

Closs, D.J., S.B. Keller, and D.A. Mollenkopf,"Chemical Rail Transport: The Benefits of Reliability,"Transportation Journal, Vol. 42, No. 3, 2003, pp. 17-30.

Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Title 49, Parts100-185, "Hazardous Material Regulations," RetrievedNovember 16, 2006, from http://www.nsc-dot.com/regs.html

Creswell, J.W., Research Design: Qualitative &Quantitative Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SagePublications, 1994.

Department ofthe Air Force, HQ USAFALG. PreparingHazardous Materials for Military Air Shipments, AirForce Manual (AFMAN) 24-204, 12 October 2004.

Department of the Army, Memorandum ofUnderstanding between SMPT, DAC, NSCS and 345 TRS,25 March 2002.

Eidson, B.,Chief of Customer Service, Dover Air ForceBase. Data retrieved via e-mail, 27 October 2006.

Ellison, V .1^., Analysis of Frustrated Vendor HazardousMaterial Shipments within the Department of Defense,Unpublished master's thesis. Air Force Institute ofTechnology, Wright-Patterson AFB OH, April 2004.

Erkut, E. and V. Verter, "A Framework for HazardousMaterials Transport Risk Assessment," Risk Analysis,Vol. 15, No. 5, 1995, pp. 589-601.

42 TRANSPORTATION JOURNAL™ Winter

Ford, K,, M, Quinones, D, Sego, and J, Speer Sorra,"Factors Affecting the Opportunity to Perform TrainedTasks on the Job," Personnel Psychology, Vol, 45, No,3, 1992, pp, 511,

Headquarters Air Force Material Command, HQAFMC/LSO, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, OH,personal communication, 17 January 2007,

Intemational Air Transportation Association (IATA),Dangerous Goods Regulations, 47''' Edition, Montreal-Geneva: IATA, 2005,

Intemational Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO),Technical Instructions for the Safe Transport ofDangerous Goods by Air, Montreal, Canada: ICAO, 2006,

Kirkpatdck, D,, "Great Ideas Revisited: Techniques forEvaluating Training Progratns," T+D, Vol, 50, No, 1,1996, pp, 54,

Kleindorfer, P,R,, and G,H, Saad, "ManagingDismptions in the Supply Chains," Production andOperations Management, Vol, 14, No, 1,2005, pp, 53-58,

Kramer, P,, Director Transportation Safety Institute,Oklahoma City, OK, personal communication, 18August 2006,

LabelMaster, Retrieved 27 November 2006 from http://www,labelmaster,com/lmstore/ default,aspx?screen=product/catalog&cataloglevel=5981,

Mejza, M,C,, R,E, Barnard, T,M, Corsi, and T, Keane,"Driver Management Practices of Motor Carrierwith High Compliance and Safety Performance,"Transportation Journal, Vol, 42, No, 4, pp, 16-29, 2003,

Revelle, C, J, Cohen, and D, Shobrys, "SimultaneousSiting and Routing in the Disposal of Hazardous Wastes,"Transportation Science, Vol, 25, No, 2, pp, 138-145,1991,

Rothwell, B,A,, W, Harsha, and T, Clever, "Militaryversus Civilian Air Cargo Training for HazardousMaterial," Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education andResearch, Vol, 12, No, 1, pp, 29-43,

Russell, D,M, and J,P, Saldanha, "Five Tenets ofSecurity-Aware Logistics and Supply Chain Operations,"Transportation Journal, Vol, 42, No, 4, 2003, pp, 44-54,

Simmons, O,, Transportation Customer ServiceSpecialist, Charleston Air Force Base, SC, data retrievedvia email, 24 October 2006, ;

Sheffi, Y,, "Supply Chain Management under theThreat of Intemational Terrorism,'' International Journalof Logistics Management, Vol, 12, No, 2, 2001, pp, 1-11,

Spendolini, M,, The Benchmarking Book, New York:AMACOM, 1992,

Sweet, K,M, "Emergency Preparedness forCatastrophic Events at Small and Medium Sized Airports:Lacking or Not?," Journal of Air Transportation, Vol,l l , N o , 3, 2006, pp, 110-143,

Wells, A,T, and J,G, Wensveen, Air Transportation:A Management Perspective, 5th Edition, Belmont CA:Thomson/Brooks/Cole, 2004,

Wynne, M,W,, Under Secretary of Defense forAcquisition, Technology and Logistics, "AcquisitionPolicy on Facilitating Vendor Shipments in the DoDOrganic Distribution System, Memorandum forSecretaries of the Military Departments," Washington,D,C,, 23 July 2003, \

Yin, R,K,, Case Study Research: Design and Methods,3rd edition. Volume 5, Thousand Oaks, CA: SagePublications, Inc, 2003, I

Young, R,R,, P,F, Swann, arid R,H, Bum, "PrivateRailcar Fleet Operations: The Problem of ExcessiveCustomer Holding Time in the ;Chemicals and PlasticsIndustries," TransportationJourhal,'Vo\.42.No. 1,2002,pp, 51-59,

Zhang, J,, J. Hodgson, and E, Erkut, "Using GIS toAssess the Risks of Hazardous' Materials Transport inNetworks," European Journal of Operational Research,Vol. 121, No, 2, 2000, pp, 316-329,