FromSlaughterhousestoSwimmingRaces ... · 2 RiverNetwork •RIVERVOICES•Volume19,Number1 ... alw...

Transcript of FromSlaughterhousestoSwimmingRaces ... · 2 RiverNetwork •RIVERVOICES•Volume19,Number1 ... alw...

Volume 19| Number 1 - 2009A River Network Publication

cont. on page 4

he Bronx River flows through some of themost impoverished communities in thenation. For years the river was largelyforgotten, hidden behind industrial

buildings and piles of scrap metal, lost underhighways and elevated tracks. A local woman whogrew up near the river was quoted in The New YorkTimes admitting, “It did not occur to me that therecould be anything natural in the Bronx.”

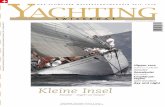

A few years ago, a golden ball descended on New YorkCity. In one day, this ball and its keepers floated downthe Bronx River, from the outer suburbs to the innercity. People fromdiverse neighborhoods,dancers and musicianswalked the ten-mileroute, following theball’s journey down theriver that connects theirhomes. Celebrationsalong the riverbankwelcomed the goldenball, a symbol of life,sun, world and energy.This community artevent spotlighted therenaissance of theBronx River.

Now that the City ofNew York is investing inthe waterfront, the river’s natural qualities and beautywill be more apparent and accessible. The ManhattanWaterfront Greenway, a 32-mile route thatcircumnavigates the island, now boasts off-street bikeand pedestrian paths, increased access to thewaterfront and the transformation of the Harlem

T River Speedway and other industrial waterfrontproperty into promenades and parks.1 As the rivercomes back to life, it is attracting tourists andbecoming a place of respite for locals. It proves thatnature does indeed exist in the city.

River RenaissanceRivers haven’t always been so valued. In the mid-nineteenth century, many cities turned away fromtheir rivers as railroads made water transportationobsolete. Waterfront streets and shops wereabandoned. Industries and scrap yards overtook the

banks. Many urban riverswere little more than opensewers, conduits for waste.

But today, thanks to thesuccesses of the CleanWater Act, most of oururban rivers are no longertoxic or pose a directthreat to human health.And as many cities shiftfrom an industrial to aservice economy, factories,smokestacks andwarehouses no longermonopolize everyriverbank. Environmentalconsciousness is more

prevalent today, and growing interest in outdoorrecreation has more people interested in what theirlocal rivers have to offer. City planners are realizingthat an attractive riverfront can act as a magnet thatkeeps people and businesses downtown andcounteracts sprawl.

From Slaughterhouses to Swimming Races:

Restoring Rivers Within City Limitsby Amy Souers Kober & Betsy Otto, American Rivers www.americanrivers.org

The Golden Ball is guided down the Bronx River, demonstratinga connection between neighborhoods and their river.

Photocredit:BronxRiverAlliance.

2 River Network • RIVER VOICES • Volume 19, Number 1

NATIONAL OFFICE520 SW Sixth Avenue, Suite 1130 • Portland, OR 97204-1511503/241-3506 • fax: 503/[email protected] • www.rivernetwork.org

RIVER NETWORK BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Todd AmbsCatherine ArmingtonSuzi Wilkins BerlRob R. BuirgyKimberly N. CharlesMary Ann DickinsonBarbara J. HornDave Katz

Leslie LoweEzra MilchmanPaul ParyskiMarc Taylor, ChairMs. Balijit WadhwaJames R. WheatonRobert L. Zimmerman, Jr.

RIVER NETWORK STAFF

Matthew BurkeRyan CarterJacob CohenWaverly de BruijnSteve DickensDawn DiFuriaMerritt FreyBevan Griffiths-SattenspielJean A. HamillaKevin Kasowski

Gayle KillamKatherine LuscherDeb MerchantEzra MilchmanMary Ellen OlceseJ.R. RalstonMichelle SeelyDiana ToledoStephen TwelkerWendy Wilson

River Voices is a forum for information exchange among river and watershedgroups across the country. River Network welcomes your comments and sugges-tions. River Network grants permission and encourages sharing and reprinting ofinformation from River Voices, unless the material is marked as copyrighted. Pleasecredit River Network when you reprint articles and send the editor a copy.Additional copies and back issues are available from our national office.

Editor: Waverly de Bruijn

Editorial Assistance: Jacob Cohen, Kevin Kasowski, Katherine Luscher

Design & Layout: Greer Graphics

River Network is a national, nonprofit

organization whose mission is to help

people understand, protect and restore

rivers and their watersheds.

CONTENTS

1 Restoring Rivers Within City Limits

by Amy Souers Kober & Betsy Otto

3 From the President

9 Eleven Places to Look for Restoration Opportunities

Excerpt from Center for Watershed Protection

14 Challenges & Opportunities in Urban Watersheds

by Jane Calvin

17 What is Your River Worth?

by Mary Hanson

20 Planning for Riverfront Revitalization

by Helen Sarakinos

24 Voices from the Field

28 Educating the Stewards of Tomorrow

by Damian Griffin

31 Why We Need to Take Our Streams Out of Pipes

by Carole Schemmerling

34 It Takes a City

by Mary Olivia Harrison

37 EPA Getting in Step: A Guide to Outreach Campaigns

38 Resources & References

39 Partner Pitch

he most celebrated successes of the environmental movementare largely focused on the pristine. Dams have come down toreturn our rivers to their natural flows. Wild and Scenic

designations have been achieved for many of our unspoiled rivers. Andecotourism businesses like rafting and fishing have flourished on remotewaterways across our country.

We cherish our natural heritage when it’s intact, but we often ignore itwhen it’s degraded. For our movement to achieve its mission, it is critical that wefocus our attention not only on pristine rivers, but also on the often overlookedrivers that flow through our cities. 81% of our country’s population lives in citiesand suburbs, representing a major confluence of resources, political power andpotential volunteers. We must view urban centers as a key part of the solution, aplace where businesses, community groups, government and industry join togetherto enhance and restore urban rivers.

Already, we are seeing impressive progress. Over the past several decades, we havewitnessed rebirth from the Willamette River in Oregon to the Bronx River in NewYork. Rivers once seen as conduits for sewage, pollutants and trash—rivers that havebeen paved, covered and channelized—are now major components of urbanrevitalization plans.

But our work is far from done. To ensure a healthy future for all life, both in thewater and on the land, we must enhance public commitment to restoring urbanwaterways. If we can succeed in our cities, we can succeed anywhere as we work tocreate a more environmentally sustainable society.

Many River Network Partners are pursuing this work as we speak and their storiespoint the way forward. You can read about a number of victories and projects inmotion in this issue of River Voices. Together, let’s make America’s urban riverrestoration emblematic of our power as a river protection movement.

In partnership,

Ezra MilchmanPresident & CEO

Volume 19, Number 1 • River Network • RIVER VOICES 3

From The President

T

Photocredit:RiverNetworkCollection

4 River Network • RIVER VOICES • Volume 19, Number 1

cont. from page 1 River renaissances similar to that of theBronx are taking place across the country incities like Chicago, Denver, Redmond (WA)and San Antonio. The attraction of urbanrivers isn’t new—what’s new is that cities arenow aiming for more than economicdevelopment. Many of today’s cities aretaking a more comprehensive approach,incorporating multiple objectives: ecologicalintegrity, economic vitality and a sense ofcommunity. These visionary cities areproving that an ecologically healthy river canbe the centerpiece of successful andsustainable city revitalization.

But what constitutes good riverfrontdevelopment? What kind of planning is bestfor the river? While there is no singleblueprint that fits everyriver, there are somegeneral principlesplanners should stick to.And recent riverfrontprojects offer lessonsabout desirable and not-so-desirable approaches.

RiverWalk,RiverShop,RiverEatOver the past 30 years,most riverfrontrevitalization efforts havebeen driven by economicgoals alone. San Antonio,Texas is a prime example of a city that usedits riverfront to pump new life into itsdowntown economy. The San Antonio RiverWalk, along with the Alamo, are the mostvisited attractions in the state.

A good riverfront makes the most of theriver’s character. It incorporates thecommunity’s history and culture. A goodriverfront captures the spirit of place and

creates a distinctive, memorable experience.This is where the San Antonio River Walksucceeds. The city’s development andpromotion of the River Walk’s uniquecharacter has been so successful, manyother cities look to San Antonio as a model.Signage and other pedestrian-scale designguidelines maintain the style of thepathways and buildings. Visitors can walkalongside the river to shops, restaurants,hotels and entertainment facilities. Theycan glide in natural gas-powered boats paststorefronts, shaded rock walls and bridges.But until recent efforts to restore the sterileconcrete-lined river channel and add backother natural stream features, San Antonio’sriverfront had been mostly ecologicallydead for decades.

Now that the San Antonio River hasbecome a major attraction for both thecommunity and out-of-towners, the SanAntonio River Improvements Project isfocusing on the restoration needs of theMuseum Reach (northern) and MissionReach (southern) sections of the river.Improvements along the Mission Reach willfocus on ecosystem restoration using fluvialgeomorphology. This technique will

Restoring Rivers Within City Limits, cont.

A calm morning on the San Antonio RiverWalk.

Photocredit:istock.com

Volume 19, Number 1 • River Network • RIVER VOICES 5

transform the straightened river toreplicate the original flow of the riverwhile maintaining flood control,reducing erosion, re-introducing nativevegetation and creating anenvironment more suitable forrecreation and wildlife.2 Phase one ofthe Mission Reach project is slated forcompletion in December 2009.

Community BenefitsFor years, the Chicago River was asewer clogged with slaughterhousewaste, a working canal monopolized bybarges. In 1885, a cholera and typhoidepidemic killed 90,000 Chicagoanswhen a storm washed sewage from theChicago River into Lake Michigan, thecity’s drinking water source. Then, in1889, sanitary engineers dug a canal toreverse the flow of the river south into theIllinois River to prevent a recurrence ofepidemics, giving the city the world’s onlyriver that flows backward.

Today, however, the Chicago River and otherarea waterways are on the rebound, thanksto water quality improvements and a large-scale restoration effort. The localconservation group, Friends of the ChicagoRiver, even holds annual swimming races.

The City of Chicago has implemented bigplans for its riverfront, with economicvitality as one of the goals. But the city isalso insisting on high water quality,increased public access, enhanced wildlifehabitats and better recreation opportunities.

Now, in addition to industrial barges, theriver also hosts families in pedalcrafts,couples sipping champagne in gondolas,pedestrians strolling on riverside walkways,herons perching on the banks, and eventhough the fish aren’t safe to eat just yet,fishermen hauling out bluegill and bass.

Today, nearly 70 species of fish inhabit theriver, where once only carp survived.

Restoring urban waterways has itschallenges—with public access to the riverbeing an initial hurdle. Easy, safe andaffordable public access via foot, bike, publictransit or boat is critical to any goodriverfront plan. And the river should bevisually accessible (frequent, interesting viewsfrom parks, picnic areas, shops andrestaurants), as well as physically accessible.

In the Chicago public housing developmentof Lathrop Homes, access was one of theriverfront restoration goals. Residents createda riverside path, re-graded the steep bank,built graceful steps down to the river edgeand added benches so they could sit underriverside trees.

Local children planted hundreds of newgrasses and shrubs and created a meanderingwood-chipped path—a plus for the residentsand a plus for the river. Smart riverfrontdesigns use a minimum of concrete sidewalksand other forms of “hardscaping” whichcreates stormwater runoff that degrades river

cont. on page 6

The Chicago River,circa 1905.

Photocredit:DetroitPublishingCo.#018839.LibraryofCongressviaEastland

MemorialSociety

6 River Network • RIVER VOICES • Volume 19, Number 1

cont. from page 5 water quality and causes bank and in-streamerosion. Porous materials, like mulch, graveland sand allow rainwater and snowmelt toabsorb into the ground rather than rushingdirectly into the river.

In addition to connecting people with theriver, a good riverfront design connects theneighborhood with the larger community. Anetwork of pathways should linksurrounding homes, shops, offices andrecreation areas. The Lathrop Homesrevitalization project includes a pedestrianpathway to nearby shopping centers.

The Chicago River is also getting a boostfrom several wetland restoration projects.

Wetlands areessential partsof a riverecosystem andshould beprotected orenhanced inany riverfrontplan. Whilewetlands can’tfilter outcertain urbanpollutants likesalt, lead andmercury, theyare veryeffective inimprovingoverall waterquality.

In a suburbnorth ofLathrop

Homes, volunteers helped restore wetlandsin Prairie Wolf Slough to managestormwater. This site in the Chicago Riverfloodplain now contains 28 acres of restoredwetland and wet prairie as well as 14 acres ofrestored forest. Prairie Wolf Slough now

retains excess water and helps reduceflooding. It also filters out pollutants fromnearby commercial and residentialdevelopments.

Restoring Nature’s BuffersOld mattresses, rubber tires, grass clippingsand diesel oil. Concrete trucks backing upand flushing out their mixers, releasing agray lava-like flow onto the riverbank. Notso long ago, these were the common sightson Denver’s South Platte River.

Today, visitors are more likely to seemallards, catfish and kids along the river.Denver’s $25 million South Platte RiverProject rehabilitated the South Platte,creating new parks and greenways,restoring wildlife habitat and providingnatural flood control. Using state-of-the-artwater resources engineering, over 300 acresof land in north Denver and south AdamsCounty were removed from the 100-yearfloodplain.3

A centerpiece of the riverfrontrevitalization effort is the 23-acreCommons Park. Opened in 2001, theCommons was constructed on land thatpreviously supported railroad tracks andwarehouses.4 Riverside parks and theirassociated grass, open space and trees arealways better for a river ecosystem than, say,a riverside parking lot. But some parks aredefinitely better for the river ecosystemthan others.

A good park essentially serves as a bulwarkbetween developed areas and the river.Depending on the size of the stream andthe space available, the buffer can stabilizeeroding banks (35+ feet), removepollutants (100+ feet), protect wildlifehabitat (300+ feet) and protect againstflood damage (needs to cover large portionof floodplain).

Restoring Rivers Within City Limits, cont.

BBRRIIGGHHTT IIDDEEAAHHoolldd sswwiimmmmiinngg eevveennttss

((iiff yyoouurr rr iivveerr iiss

sswwiimmmmaabbllee)) ttoo rraaiissee

aawwaarreenneessss aanndd

aapppprreecciiaattiioonn ffoorr yyoouurr

rriivveerr.. IInn aaddddiitt iioonn ttoo

FFrriieennddss ooff tthhee CChhiiccaaggoo

RRiivveerr,, tthhee CChhaarrlleess RRiivveerr SSwwiimmmmiinngg

CClluubb iiss aann oorrggaanniizzaattiioonn tthhaatt

oorrggaanniizzeess ccoommppeettiitt iivvee sswwiimmmmiinngg

eevveennttss ttoo ffaacciill ii ttaattee tthhee rreettuurrnn ooff

rriivveerr sswwiimmmmiinngg aanndd eennccoouurraaggee

ccoonnttiinnuueedd cclleeaann--uupp ooff tthhee rr iivveerr..

wwwwww..cchhaarrlleessrriivveerrsswwiimmmmiinnggcclluubb..oorrgg

BBRRIIGGHHTT IIDDEEAASShhaaddee yyoouurr rr iivveerrssiiddee

pprroommeennaaddee wwiitthh

nnaattiivvee ggrraasssseess aanndd

ootthheerr ppllaannttss tthhaatt

pprroommoottee tthhee

oorriiggiinnaall,, nnaattuurraall

ssttaattee ooff tthhee rr iivveerr..

Volume 19, Number 1 • River Network • RIVER VOICES 7

Creating parks and buffers that benefitthe river ecosystem might mean givingup some traditional notions of what’s“pretty.” Pruned geometric shrubs oroverly landscaped andmanicured turf lawns, forexample, don’t encouragebiodiversity and oftenrequire harmfulpesticides. Beds of non-native flowers arenot the best food source for local insects,birds and wildlife.

Denver’s Commons Park proves it ispossible for a park to be beautiful andecosystem-friendly. The park’s west edgealong the South Platte was designed toenhance the river’s natural character, anda special “seep,” or wetland with water-loving plants like sedges andcottonwoods, will handle the river’soccasional floods.

Since the restoration began, local school kidshave been reconnecting with the river.Inner-city kids now have the opportunity tobe trained as river tour guides and tens ofthousands of school children have takenfield trips to the river to learn about theecosystem and South Platte history.Interpretive kiosks and signs can help bothchildren and adults understand the river’splace in community history and current life.

Good riverfront plans foster education…andfun. At one of Denver’s first riverside parks,the highlight isn’t native plants, it’swhitewater. At Confluence Park, kayakers canslip out during their lunch breaks to paddleclass II-III rapids.

Restoring a River’s Natural FlowRedmond, Washington’s Sammamish River istypical of many urban and suburbanstreams. The river lost much of its riparianarea and native vegetation when the ArmyCorps of Engineers straightened andreconstructed the river into a deeptrapezoidal channel in the 1960s.Straitjacketing the river destroyed habitatand dealt a blow to the river’s once-abundantsalmon.

The Army Corps’ heavy-handed approachdefied the most basic rule in riverfrontplanning: ‘let the river be a river.’ Fortunately,that fundamental principle is now thedriving force behind Redmond’srevitalization project. Today, the river isregaining its shape, flow and other natural

cont. on page 8

The most effectiveurban buffers havethree zones:streamside, middlezone and outer zone.

athletic fieldsgardenslawnspicnic areasplaygroundstrailsbike paths

trailsbike pathsshade gardenspicnic tablesbenchesdemonstration plantingsarboretum

trail spurs tolookouts

benchescontrolled

access to waterarboretum

Grass and herbaceous plants spreadsurface runoff to catch sediment andimprove infiltration and water storage

Woodland provides habitatand purifies surface and subsurface water

Undisturbed shrubsand trees providehabitat, shade waterand stabilize banks.

Riparian Buffer

8 River Network • RIVER VOICES • Volume 19, Number 1

characteristics. Out behind City Hall,engineers are re-creating some of the river’smeanders and curves and adding boulders,root wads and gravel bars to the onceuniform and sterile channel.

Salmon have already benefited from a pilotproject on another 300-foot long stretch ofriverbank. Just west of City Hall, the bankwas gradedinto aseries ofearthbenches.The top ofthe bankwas movedback fromthe riverabout 50feet at itsmaximumpoint.Thesebencheswereplantedwith nativevegetationand provide the potential for differenthabitat zones. They also are helping tomaintain the river’s flood flow capacity.

Tying these restoration projects together isRedmond’s new riverwalk, a thoroughfare ofjoggers, bikers, shoppers and migratingsalmon.

Looking to the FutureFrom the golden ball of the Bronx to the redfish of Redmond, riverfront revitalizationprojects are changing the way we seeourselves in our environments. People arereconnecting with their rivers. As formerMayor of Milwaukee, John Norquist, wrotefrom the banks of the Milwaukee River,“When people walk, talk, work, eat, drink,

cont. from page 7 boat and play by the water, when itbecomes part of their day-to-day life andnot merely a special-occasion destination, areal constituency for clean water is created.”

Many revitalization successes show us whatcan be done when urban river revitalizationis recognized as an opportunity to boostlocal economies and quality of life. River

groups can play aparticularlyvaluable role inmaking the casefor restoringriver healthalong witheconomicvitality. Riveradvocates canstart today bycompiling factsand argumentsshowing how thecommunity willbenefit fromriverrevitalization,involving thecommunity to

determine their needs and vision for arevitalized riverfront, conductingassessments of the river and watershed forareas where potential restoration efforts canbe made, and creating a revitalization planto put all of this into action. The followingarticles of this River Voices will help youbegin to delve into these issues.

Restoring Rivers Within City Limits, cont.

FFoorr mmoorree oonn tthhiiss ssuubbjjeecctt sseeee tthhee rreeppoorrtt

ccoo--aauutthhoorreedd bbyy AAmmeerriiccaann RRiivveerrss aanndd tthhee

AAmmeerriiccaann PPllaannnniinngg AAssssoocciiaattiioonn ccaall lleedd

EEccoollooggiiccaall RRiivveerrffrroonntt DDeessiiggnn,, aavvaaii llaabbllee oonn

AAmmeerriiccaann RRiivveerrss’’ wweebbssiittee..

AAnn eeaarrll iieerr vveerrssiioonn ooff tthhiiss aarrtt iiccllee oorriiggiinnaall llyy

aappppeeaarreedd aass RReessttoorriinngg RRiivveerrss WWiitthhiinn CCiittyy

LLiimmiittss bbyy AAmmyy SSoouueerrss aanndd BBeettssyy OOttttoo iinn

OOppeenn SSppaacceess vvoolluummee 33 nnuummbbeerr 44,,

wwwwww..ooppeenn--ssppaacceess..ccoomm//aarrttiiccllee--vv33nn44--

rriivveerrss..pphhpp.. IItt hhaass bbeeeenn uuppddaatteedd aanndd

ccoonnddeennsseedd..

1 New Your City Department of City Planning, Manhattan Riverfront Greenway.www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/html/mwg/mwghome.shtml2 San Antonio River Improvements Project Fact Sheet. www.sanantonioriver.org/facts.html3 Denver Public Works Press Release, Largest Flood Control Project in the Metropolitan Area Complete.www.denvergov.org/Portals/485/documents/South%20Platte%20River%20Project%20release.pdf4 City Parks Forum Briefing Paper 01, How cities use parks for...Community Revitalization. AmericanPlanning Association. atfiles.org/files/pdf/citiesparksrevitalization.pdf

EEaacchh wwaatteerrsshheedd iiss ccoommppoosseedd

ooff aa nnuummbbeerr ooff ssmmaall lleerr

wwaatteerrsshheeddss ccaall lleedd

““ssuubbwwaatteerrsshheeddss,,”” wwhhiicchh

ggeenneerraall llyy hhaavvee aa ddrraaiinnaaggee

aarreeaa ooff ffiivvee ttoo 1100 ssqquuaarree mmii lleess

oorr lleessss.. TThhee ssmmaall ll ss iizzee ooff

ssuubbwwaatteerrsshheeddss mmaakkeess tthheemm

iiddeeaall rreessttoorraattiioonn ccaannddiiddaatteess

ffoorr sseevveerraall rreeaassoonnss::

•• SSuubbwwaatteerrsshheeddss ccaann bbee

rraappiiddllyy mmaappppeedd aanndd

aasssseesssseedd ffoorr rreessttoorraattiioonn

ppootteennttiiaall iinn aa mmaatttteerr ooff

mmoonntthhss,, wwiitthh aann iinniitt iiaall

rreessttoorraattiioonn ssttrraatteeggyy

ffooll lloowwiinngg ssoooonn aafftteerr..

•• TThhee ssmmaall ll ssccaallee ooff aa

ssuubbwwaatteerrsshheedd aallssoo aall lloowwss

rreessttoorraattiioonn pprraaccttiicceess ttoo bbee

ddeessiiggnneedd,, ccoonnssttrruucctteedd aanndd

aasssseesssseedd wwiitthhiinn aa ffeeww yyeeaarrss..

•• MMoosstt ssuubbwwaatteerrsshheeddss aarree

ccoonnttaaiinneedd wwiitthhiinn aa ssiinnggllee

ppooll ii tt iiccaall jjuurriissddiiccttiioonn,, mmaakkiinngg

iitt eeaassiieerr ttoo ccoooorrddiinnaattee llooccaall

ssttaakkeehhoollddeerrss..

Volume 19, Number 1 • River Network • RIVER VOICES 9

Envisioning Restoration:

Eleven Places to Look for Restoration Opportunitieshe most important skill in urbanwatershed restoration is an abilityto envision restorationopportunities within the stream

corridor and upland areas. It takes apracticed eye to find these possibilities in alandscape dominated by the builtenvironment. Still, many good restorationopportunities can be discovered.

This article was adaptedwith permission fromUrban SubwatershedRestoration Manual 1:An Integrated Approachto Restore Small UrbanWatersheds; Chapter 5:Envisioning Restoration

Prepared by Tom Schueler

Center for WatershedProtection

www.cwp.org

Urban subwatersheds, or smaller unitswithin the larger watershed, are a complexmosaic of both impervious and perviouscover. The best restoration opportunitiesare usually found in the remaining perviousareas. As much as three to five percent ofsubwatershed area may be needed to locateenough restoration practices to repair orimprove stream conditions. Further, thisland must be located in the right place andbe controlled by willing landowners. Lastly,restoration sites are distributed acrossdozens and sometimes hundreds of smallparcels within a subwatershed.

The process of discovering theseopportunities is called “envisioningrestoration,” and consists of two basictechniques: intensively analyzing maps andaerial photographs, and conducting a rapidreconnaissance of actual conditions in thesubwatershed. Both techniques are as mucha skill as a science, and certainly nocomputer model can do the same jobs.

The Remnant Stream CorridorThe stream corridor is the first place toenvision restoration. Regrettably, the urbanstream network is poorly portrayed onmost maps. Stream interruptions, crossingsand channel alterations are not depicted,and the width and condition of the streamcorridor are seldom delineated with anyaccuracy (indeed, it is usually shown onmaps as undefined white space betweenbuildings, streets and parking lots). Aerialphotographs that show current vegetativecondition are the best tool for defining theapproximate boundaries of the streamcorridor.

While maps and photos are a starting point,the stream corridor can only be truly seenby walking the entire stream network.1 Thestream corridor is an important place toenvision restoration because it is thetransition zone between the upland storm

T

cont. on page 10

The restoration potential of a stormwaterinfrastructure depends largely on its age.Stormwater systems constructed prior to1970 are mostly underground, with limitedsurface land devoted to flood controlprojects. Systems from 1970 to 1990 wereoften built with stormwater detentionponds designed to control peak flooddischarges. Detention ponds, which areoften quite large, greatly add to the surfaceland available for potential restoration, andare always a favorite target for storageretrofits. Systems designed over the lastdecade reflect the growing trend toward thetreatment of stormwater quality, and maycontain dozens of stormwater treatmentpractices of all different sizes and types.

10 River Network • RIVER VOICES • Volume 19, Number 1

drain network and the urban stream. Withinthis narrow zone, there is often enoughavailable land to install restoration practicesto repair or improve stream conditions.These include storage retrofits, riparianmanagement and discharge preventionpractices.

Existing Stormwater InfrastructureEach subwatershed has a vast network ofcatch basins, storm drains, outfall pipes,detention ponds, flood ways and stormwaterpractices that convey stormwater. Theexisting stormwater system is attractive forrestoration for two reasons. First, as much asthree percent of total subwatershed area maybe devoted to the stormwatersystem (although often at theexpense of the existing streamcorridor). Second, since land isalready devoted to stormwatermanagement, it is much easier toget approval from owners toretrofit it.

cont. from page 9

Eleven Places to Look for Restoration Opportunities, cont.

EElleevveenn PPllaacceess ttoo EEnnvviissiioonn RReessttoorraattiioonn iinn aa SSuubbwwaatteerrsshheedd

11 .. RReemmnnaanntt SSttrreeaamm CCoorrrriiddoorr

22.. EExxiissttiinngg SSttoorrmmwwaatteerr IInnffrraassttrruuccttuurree

33.. OOppeenn MMuunniicciippaall LLaanndd

44.. NNaattuurraall AArreeaa RReemmnnaannttss

55.. RRooaadd CCrroossssiinnggss aanndd RRiigghhttss--ooff--wwaayy

66.. LLaarrggee PPaarrkkiinngg LLoottss

77.. SSttoorrmmwwaatteerr HHoottssppoottss

88.. RReessiiddeennttiiaall NNeeiigghhbboorrhhooooddss

99.. LLaarrggee PPaarrcceellss ooff IInnssttiittuuttiioonnaall LLaanndd

1100.. SSeewweerr NNeettwwoorrkk

11 11.. SSttrreeeettss aanndd SSttoorrmm DDrraaiinnss

Large parking lots produce the highest unitarea of stormwater runoff and pollutant

loadings of any subwatershed land use, andstand out in most aerial photographs. Ph

oto credit: Center for Watershed Protection

Volume 19, Number 1 • River Network • RIVER VOICES 11

These newer practices are a particularlyattractive retrofitting target. A good map ofthe urban stormwater pipe system isextremely helpful, if available. Severallocations on these maps deserve closescrutiny: outfalls where stormwater pipesdischarge, open land adjacent to theseoutfalls, and any surface land devoted tostormwater detention and/or treatment.These locations are prime candidates forstorage retrofits and stream daylightingpractices. Stormwater outfalls are also thestarting point to look for illicit dischargesthat may be flowing through the storm drainsystem.

In reality, the stormwater pipe network ispoorly mapped in most communities, andoften reflects a confusing blend of pipes andstructures built in many different eras. Soonce again, field reconnaissanceis necessary to see how itactually works. In practice, the

many routes that stormwater travels to get tothe stream corridor must be traced byworking up from each storm drain outfall.

Open Municipal LandMunicipal lands such as parks, public golfcourses, schools, rights-of-way or protectedopen space are attractive areas for restorationbecause of their large size and ownership.While municipal lands are managed fordifferent purposes, portions of each parcelmay be good candidates to creatively locaterestoration practices. In addition, open landsare easy to distinguish on either aerialphotographs or tax maps, and are easy toconfirm in the field.

Natural Area RemnantsForest and wetland fragments are frequentlylocated near the stream corridor, and thelarger contiguous parcels are hard to misswhen looking at an aerial photograph orresource inventory map. Larger remnantsand their adjacent margins always deserveclose scrutiny in the field. A two-acre sizethreshold is often used to select parcels forfield analysis. Natural area remnants are nota preferred location for intrusiverestoration practices (such as a large storageretrofit), but may be good targets for forestor wetland restoration. In addition, thepossibility of expanding natural areas orlinking them to the stream corridor orother remnants should always beconsidered.

Road Crossings and Highway Rights-of-WayRoad crossings and rights-of-wayare always worth exploring forrestoration opportunities.Stream crossings are quite easyto spot on aerial photos or

regular maps. Two specific areas of the mapshould be located: the points where roadscross the stream corridor, and large rights-of-way, such as cloverleaf interchanges andhighway access ramps.

Each road crossing presents both a problemand an opportunity. Bridges and culvertsthat cross the corridor are always suspectedbarriers to fish migration, but they may alsounintentionally act as a useful grade controlin a rapidly incising stream. In very smallstreams, these crossings can be modified toprovide temporary storage and treatment ofstormwater upstream of the crossing. Lastly,road crossings often provide the best accessto the stream corridor for streamassessments, cleanups and constructionequipment.

cont. on page 12

12 River Network • RIVER VOICES • Volume 19, Number 1

cont. from page 11 Larger highways often have fairly largeparcels of unused land nearinterchanges in the form of cloverleafsand approach ramps. These parcels canbe an ideal location both for storageretrofits and reforestation, because theyreceive polluted runoff from thehighway and generally serve no otherpurpose.

Large Parking LotsLarge parking lots really stand out inan aerial photograph or land use map andare of great interest for several reasons. First,they produce more stormwater runoff andpollution on a unit area basis than any otherland use in a subwatershed. As such, they areobvious targets for on-site or storageretrofits. Second, large parking lots generallysignal the presence of large clusters ofcommercial, industrial or institutional landsoften associated with stormwater hotspots.While these areas can be easily identifiedfrom a desktop, it is usually necessary to visiteach one to determine its actual potential forretrofitting or source control.

Stormwater HotspotsThe next place to envision restoration is inthe many stormwater hotspots in asubwatershed.

Stormwater hotspots are the commercial,industrial, institutional, municipal, andtransport-related land uses that tend toproduce higher levels of stormwaterpollution, or present a higher risk for spills,leaks and illicit discharges. The number,type and distribution of stormwaterhotspots vary enormously betweensubwatersheds. Maps and aerial photos areof little value in finding hotspots; instead,they can be found by searching databasesthat contain standard business codes orpermits, or by driving the entiresubwatershed looking for them, or both.

Residential NeighborhoodsResidential neighborhoods are easy to seeon a map, but must be visited to be trulyunderstood. Each residential neighborhoodhas a distinctive character in terms of age,lot size, tree cover, lawn size and generalupkeep. In addition, neighborhoods tend tobe rather homogenous when it comes toresident behavior, awareness andparticipation in restoration efforts. Eachunique neighborhood characteristic directlyaffects the ability to widely implementresidential restoration practices, such as on-site retrofits and residential stewardshippractices. In general, it is not easy to discernneighborhood characteristics from a map oreven an aerial photograph. Instead, aneighborhood assessment2 can be used to

BBRRIIGGHHTT IIDDEEAASStteennccii ll ssttoorrmmwwaatteerr ddrraaiinnss

ttoo eedduuccaattee tthhee ccoommmmuunniittyy

aabboouutt tthhee iimmppaaccttss ooff

dduummppiinngg hhaazzaarrddoouuss

mmaatteerriiaallss ddoowwnn tthhee ddrraaiinn——

aanndd iinnttoo tthhee rriivveerr..wwwwww..eeppaa..ggoovv//aaddoopptt//ppaattcchh//hhttmmll//

gguuiiddeell iinneess..hhttmmll

Eleven Places to Look for Restoration Opportunities, cont.

Volume 19, Number 1 • River Network • RIVER VOICES 13

collect quantitative data on neighborhoodcharacteristics to determine their restorationpotential.

Large Institutional Land OwnersLarge institutional land owners have the lastremaining land worth prospecting forrestoration potential in a subwatershed.Examples include hospitals, colleges,corporate parks, private golf courses,cemeteries and private schools. Inspection ofaerial photos may reveal that institutionshave underutilized areas on their groundswith restoration potential.

The Sewer SystemThe sewer system is always an importantplace to envision restoration potential,although it is intrinsically difficult to seesince most of it is located underground.Most communities have good maps of theirsewer pipe networks, although olderportions may be much less reliable. The keyfactor to determine is whether the sewersystem is a source of sewage discharges to thestream corridor that it often parallels. Theseverity of sewage discharge depends on theage, condition, and capacity of the sewernetwork.

Streets and Storm Drain InletsPollutants tend to accumulate on streetsurfaces and curbs, and may be temporarilytrapped within storm drain catch basinsand sumps. These storage areas oftenrepresent the last chance to removepollutants and trash before they wash intothe stream. Municipal maintenancepractices, such as street sweeping, catchbasin clean-outs and storm drain stenciling,can potentially remove some fraction ofthese pollutants, under the right conditions.These municipal practices are particularlywell-suited for highly urban subwatershedsthat have many streets, but few otherfeasible restoration options.

SummaryThis article described how and where tosearch for restoration potential in urbansubwatersheds. Each subwatershed has adifferent combination of opportunities andthus different restoration potential. Thenext step for any river or watershedorganization would be to create aframework for translating these possibilitiesinto a realistic subwatershed plan.

1 The Unified Stream Assessment (USA), described in Center for WatershedProtection’s Urban Subwatershed Restoration Manual 10, has been developed asa tool to systematically evaluate the remaining stream area.

2 For more information, see the Neighborhood Source Assessment (NSA)component of the Unified Subwatershed and Site Reconnaissance (USSR),found in Manual 11 of the Center for Watershed Protection’s UrbanSubwatershed Restoration Manual Series.

any river groups working inurbanized areas have lookedfor ways to improve the health,vitality and access to the rivers

and streams that run through the place theycall home. In order to restore a watershedand its rivers, groups must look to thepreservation and restoration of land in areasall over the city and throughout thewatershed. At the watershed scale, riverrestoration projects often focus onmitigating stormwater by retrofittingimpervious surfaces. At a more localizedscale, protecting and connecting parcels ofland along the river corridor can be vital toestablishing buffers that provide habitat,stormwater runoff filters and importantly,access to the river itself. By creating access toan urbanized river corridor you engageneighborhood residents that can thenbecome stewards of the river and the land itruns through. When community memberscan develop and strengthen an appreciationof the environment in their own backyard,they can then work to continue preservingand restoring some of their city’s biggesthidden assets.

Protecting land in an urban setting requiresaddressing challenging and complex landprotection issues and engaging diversestakeholders, all while protecting theremaining conservation values of oftenmarginalized properties. Creating access to ariver in an urbanized community addsadditional layers of complexity. Protectingurban open spaces requires the flexibility tolook into parcels of a much smaller scale(ranging from thousands of square feet to afew acres); comprehension of landownership and conservation financemechanisms to access properties with oftenvery high real estate value; and a strong localcapacity to know your “place” intimately,including where and how to build effectivepartnerships. These “challenges” will thenbecome assets and opportunities—to lace

14 River Network • RIVER VOICES • Volume 19, Number 1

Protecting Open Spaces:

Challenges & Opportunities in Urban Watersheds

Mby Jane Calvin

Lowell Parks &Conservation Trust

www.lowelllandtrust.org

together networks of unconnected ripariancorridor, engage new stakeholders, addressany potential brownfield sites and attractfunders. Succeeding in urban landprotection can mean creating access to openspace for populations living in aneighborhood divided by industrial use orwith limited recreational opportunities.

Making Creative Use of Land in Lowell, MALowell, Massachusetts sits at the confluenceof two rivers; the Merrimack, which flowsnorth into New Hampshire, and theConcord, which flows south and is part ofthe Sudbury-Assabet-Concord (SuAsCo)watershed. Passing through one of thenation’s first planned industrial cities (pop.of 104,000), the Concord River has beenheavily industrialized, yet flows throughvibrant, dense and ethnically diverseneighborhoods. Remarkably, significantopen space still exists along the easternbanks of the river, held in large part bythree property owners. The Concord River,Lowell’s “hidden jewel,” has been largelyinvisible to the public due to its historic andcurrent industrial use, but also becauseroadways only cross the river at fourbridges. Protecting the Concord Riverrequired “thinking outside the box” aboutalternative land protection mechanisms.The Lowell Parks & Conservation Trust(LP&CT) has been working for over adecade on one embodiment of suchthinking on a project to create the ConcordRiver Greenway Park.

The Concord River Greenway became thevision of an LP&CT board member afterstumbling on the river in his ownneighborhood as a young man. TheGreenway, now in partial construction, is a1.75-mile multi-use recreational trail whichfills an important gap in our regional trailnetwork. The northern end of the

Volume 19, Number 1 • River Network • RIVER VOICES 15

cont. on page 16

Greenway will connect withLowell’s downtown rivertrails and canal walkways.From the southern end theGreenway will eventuallyconnect with a 25-mile trailthat will follow anabandoned rail corridorfrom Chelmsford toFramingham.

Creative Land Protection StrategiesThe Concord RiverGreenway project exemplified howprotecting land to create a park along anurban river corridor can be complex – andrequire years of patience. If your group isembarking on such a project, your approachmay include some or all of the followingcreative land protection strategies: • Contaminated land: Brownfields andparcels of contaminated land can beencountered along urban rivers. Theseremnants of the industrial age can beeasier to acquire because the land isdeemed less desirable and may evenprovide for itself through the ability toapply for specialized funding.Drawbacks of acquiring contaminatedland include a longer, more arduousclean-up process. The northernmostterminus of the Greenway includes theaddition of park land along the edge ofa 3-acre parking lot which happened tobe the site of a large brownfield.Brownfield funding that the City ofLowell received helped leverageadditional funding for construction ofthe Greenway.

• Tax delinquent properties: Landownersthat fall into excessive arrears in payingproperty taxes can have their land seizedby the government, which then becomesa “tax title” property. Given the right

circumstances, tax delinquentproperties provide a relatively easyavenue for acquiring and protectingland. An inventory of tax delinquentproperties on the Concord RiverGreenway corridor identified severalnarrow, undevelopable parcels of landpreviously used for water access rightsthat simply needed to be converted toconservation land.

• Land use conversion: Identifying themechanism to convert land tomunicipal ownership (the City ofLowell will own and maintain theGreenway once complete) doesn’tnecessarily permanently protect accessto the land. In Massachusetts, theselands can be converted to“conservation land” under Article 97 ofthe MA General Laws, which protectsthem until the state legislature convertstheir use with a two-thirds vote.

• Eminent domain: Eminent domaincan be used to help clear the title toland so that the property can be usedfor a public purpose. A portion of theGreenway will follow a former railwayspur which was seized by eminentdomain when land rights of theabandoned railroad property revertedto the previous, tax-delinquent owner.

Design plans for a smallportion of the ConcordRiver Greenway.

Image credit: AECOM Earth Tech/BSC Group

16 River Network • RIVER VOICES • Volume 19, Number 1

cont. from page 15 • Easement swaps: The various layers ofownership in an urban area, whilesometimes confusing, can also provideleverage in creating public access to theriver. When the City of Lowell acted totake former railroad land by eminentdomain, it erased a utility lineeasement held on the same property.This utility line leads to a substation onland held by one of three primaryabutters to the Greenway. Working withthe city, we’re in preliminarynegotiations to gain access through theutility’s land in exchange for access totheir power line corridor.

Creatively Combining ObjectivesIt is important to keep an eye out forcreative funding opportunities in additionto creative land protection. You never knowwhen such objectives will combine. Forexample, a city planner with a vision for theGreenway suggested that the city allowdevelopment of conservation land in thearea (no longer needed for well headprotection). This enabled the city to raise$875,000 for the first phase of Greenwayconstruction and manage to permanentlyprotect an additional 10 acres behind thewell head land at the same time.

Adding a creative element to the Greenway’sdesign can also attract funders, stewards,and further land protection efforts. Afterattending several conferences, such as theNational River Rally, I learned that thecreative elements of trail design must beincorporated early on in the design phase.Now, through an intensive community-based process, the Greenway’s designintegrates public art into the infrastructure(fences, gateways, bridges and surfaces) ofthe trail. Furthermore, the river corridor’sland use history is incorporated into sixhistoric wayside panels that are the basis fora major outdoor classroom initiative withnew partners.

From Land Protection toCommunity Engagement, and Back AgainWe hope that the example of the ConcordRiver Greenway initiative inspires you to getstarted on a long-envisioned project (thatmight seem as daunting as ours once did).Once the land is protected and thecommunity can envision its future use, younever know who you’ll meet on the trail.We aspire to create a multi-dimensionalexperience that can become a destination—for teachers interested in using it forenvironmental education, for those that areinterested in learning about the land usehistory and ecology of the corridor, or forthose that will enjoy the public art andrenewed aesthetic of the river. By engagingneighborhood residents, students and artistsin the Greenway corridor, we hope the cyclecontinues and that these same stakeholderswho now have access to nature within theircity will be more passionate and engaged inthe further restoration and protection oftheir rivers and natural spaces.

Challenges & Opportunities in Urban Watersheds, cont.

Along the Greenway,students and passersby

can read about thehistory of the river

corridor.

Volume 19, Number 1 • River Network • RIVER VOICES 17

hat is your river worth? Mostcities started as settlementsalong a river, where barge trafficand ferries brought people and

supplies in and out of the region. Eventuallyconditions changed as railroads and thenhighways took over as the main form oftransportation. Traditional businesses usingthe riverfront went away as industry movedin. As some cities began replacing industryand manufacturing with service sector jobs,canneries closed, manufacturing plantsmoved and housing was moved farther awayfrom the river. Over the years, the riverfrontbecame an abandoned industrial site; a dark,ugly place to be avoided.

Still, there are residents who can look pastthe ruins and see the potential of their river.These river supporters or watershed groupssee the environmental and economic benefitsof restoring an urban river. The problem isthat while your organization understands theintrinsic value of your urban river and itspossibilities, other stakeholders may not.

One important aspect of building a case forriver revitalization is to impress upon othersthe tangible values—such as economicbenefits—of such an endeavor. Eachcommunity and their river have their ownunique circumstances. Build a rationale for

Building a Rationale for River Revitalization:

What is Your River Worth?

W your river, drawing on examples that fityour situation. The following is a listsuggesting topics and how to gather thedata to build an economic rationale in favorof greenways and other river projects.

Quote Examples from Successful ProjectsPeople like to hear positive examples ofriverfront redevelopment to be assured thatother communities have already hadsuccesses. Quoting from other examplesallows you to present evidence thatgreenways and trails may increase nearbyproperty values and demonstrate how anincrease in property values can increaselocal tax revenues and help offset greenwayacquisition costs. There are many examplesof the economic benefits available throughacademic research, web sites and city offices.Even with swings in the real estate market,people will still pay more for housing near agreen space, especially if water is nearby. • Increased Property Values. Astoria,Oregon lies on the south bank of thelower Columbia River estuary.1 Thecommunity suffered from the loss ofthe cannery industry, and a rail lineblocked access to the river. As part of amaster plan to restore the riverfront, a

by Mary Hanson

Rivers, Trails &Conservation Assistance

National Park Service

www.nps.gov/rtca

HHOOWW TTOO FFUUNNDD YYOOUURR UURRBBAANN RREEVVIITTAALLIIZZAATTIIOONN NNEEEEDDSS

TThheessee aarree ttoouugghh tt iimmeess ffoorr nnoonnpprrooffiitt eennvviirroonnmmeennttaall ggrroouuppss.. TThhee ttooppssyy--ttuurrvvyy eeccoonnoommyy

hhaass ccrreeaatteedd aa rrooll lleerr ccooaasstteerr ffoorr oouurr ffuunnddeerrss aanndd mmaajjoorr ddoonnoorrss,, mmaakkiinngg ii tt

mmoorree ddiiffffiiccuulltt ffoorr tthheemm ttoo ssuussttaaiinn oouurr ccrruucciiaall wwoorrkk.. BBuutt iiff yyoouu’’vvee ggoott

gguummppttiioonn aanndd aa ggoooodd iiddeeaa,, llooookk iinnttoo RRiivveerr NNeettwwoorrkk’’ss eexxtteennssiivvee ll iisstt ooff oovveerr

110000 rr iivveerr aanndd wwaatteerrsshheedd ffuunnddeerrss iinn tthhee NNaattiioonnaall DDiirreeccttoorryy ooff FFuunnddiinngg

SSoouurrcceess,, nnooww aavvaaii llaabbllee oonn RRiivveerr NNeettwwoorrkk’’ss PPaarrttnneerr--oonnllyy wweebbssiittee..

wwwwww..rriivveerrnneettwwoorrkk..oorrgg//rrnn//ppaarrttnneerrss

cont. on page 18

18 River Network • RIVER VOICES • Volume 19, Number 1

mixed-use neighborhood brownfieldredevelopment now offers houses from$150,000 to $500,000 where acontaminated, unused piece of landonce stood, and received the PhoenixAward for this project’s results.

• Reduced Agency Expenditures. Explainhow the agency responsible formanaging a river, trail or greenway cansupport local businesses by purchasingsupplies and services. Jobs created bythe managing agency may also helpincrease local employmentopportunities and benefit the localeconomy. Leaders in Johnson County,Kansas, expected to spend $120 millionon stormwater control projects. Instead,voters passed a $600,000 levy to developa countywide streamway park system.Development of a greenway networkalong streambeds addressed some of theCounty’s flooding problems, andprovided a valuable recreationalresource.2

• Increased Tourism Revenue. Describehow greenways, rivers and trails, whichattract visitors to a community, supportlocal businesses such as lodging, foodestablishments and recreation-orientedservices. Greenways may also helpimprove the overall appeal of acommunity to visitors and increasetourism. The San Antonio River Walk ishas come to be a major anchor of thevisitor industry in San Antonio, Texas,and has helped create the city’s annualTourism revenue of over $8.7 billion.3

The River Walk provides a downtownstaging ground for public festivals andcelebrations such as Fiesta Noche delRio, Fiesta de Las Luminaries and LasPosadas and it offers a safe andattractive pedestrian system for thedowntown area.

Find Evidence of the Effects of Greenways onProperty Values in YourCommunity Research of demographics and changes tothe housing and business markets aretracked by universities, Smart Growthorganizations, realtor associations andothers.4 Due to the significant impacthousing prices can have on a community,many studies are available to show theeffects of greenways on property values. TheUniversity of Nebraska-Omaha completedsurveys along three trails, two of whichwere alongside creeks in Omaha, Nebraska.Almost two-thirds of those surveyed felt thetrails would increase the selling price oftheir home.5

Conduct Interviews on How Open Space AmenitiesAffect Land ValuesThe National Association of Realtors(www.realtor.org/research) providesinformation from across the nation on realestate trends, but visiting with local realestate agents and appraisers can give youthe latest, up-to-date information for yourcommunity. Potential buyers tell them theirdesires for housing and amenities. Agentswant to fulfill these requests to make sales.

Reviewing assessments and sales at thecounty assessor’s office can alsodemonstrate housing trends. Find a nearbycommunity that has already implemented ariverfront redevelopment. Compare sales ofa typical housing-only suburb to a mixed-use development along the river. Determinethe percentage difference. Use that numberto show how redevelopment along the rivercould increase property values and taxrevenues.

What is Your River Worth?, cont.

cont. from page 17

Volume 19, Number 1 • River Network • RIVER VOICES 19

Survey Local ResidentsLet local residents tell you whatthey think. Most will be verypleased to have been asked theiropinion. Once again, quality oflife with economic viability willbe their primary interests. It isalso an opportunity to provideinformation on the local river orwatershed group’s ideas. Havebrief information on theeconomic benefits and photographic or handrendered examples researched and availableto support your cause.

A survey does not need to be formal orcomplicated. Find examples from previousstudies; visit with a college oruniversity professor in arelated field; ask the cityoffices what information theyand the community see aspertinent. There may bestudents who need tocomplete research or would beinterested in assisting in the surveying.

Ask the most important questions, but keepit short. A few key questions can provide theinformation you need without overwhelmingeveryone involved. Compare the results withpast surveys for new information andcorrelation. Format the information intoeasily understood handouts andpresentations so it is easy to present whenopportunities arise.

Document How the Greenway has Changed the Design of the NeighborhoodWhen an area is improved, are people nowbuilding more expensive homes? Is there anincrease in retail outlets, restaurants andoffice space? Is there an increase in thenumber of people out along the river or on

trails? Has the community with a riverredevelopment seen an increase in newresidents in that area? Are there communityevents now being held along the river?

Document Developers’ Use ofOpen Space in Designing andMarketing their PropertiesDevelopers are in business to makemoney. They pay attention to the trendsthat attract new buyers and increase the

value of their properties. Developmentsalongside rivers with trails and greencorridors are an attractive amenity. Look foradvertisements that include beautiful viewsof a river invoking an attractive lifestyle.Partner with developers that supportriverfront redevelopment to promote theconcept to the public.

What is your river worth? It can besignificant. By following the steps above,researching information and talking toresidents, city officials and developers, youwill provide relevant information to yourcommunity and increase the success of yourriverfront redevelopment plans.

MMoorree ccaann bbee ffoouunndd iinn tthhee uuppccoommiinngg

eeddiitt iioonn ooff NNaattiioonnaall PPaarrkk SSeerrvviiccee

ppuubbll iiccaattiioonn EEccoonnoommiicc IImmppaaccttss ooff

PPrrootteeccttiinngg RRiivveerrss,, TTrraaiillss aanndd GGrreeeennwwaayy

CCoorrrriiddoorrss.. TThhee FFoouurrtthh EEddiitt iioonn ((11999955))

RReevviisseedd,, iiss aavvaaii llaabbllee aatt

wwwwww..nnppss..ggoovv//ppwwrroo//rrttccaa//eeccoonniinnddxx..hhttmm..

1 Waterfront Revitalization in Non-Metropolitan Coastal Communities. Washington Sea Grant, 3716 BrooklynAvenue NE, Box 355060, Seattle, WA 98105-6716staff.washington.edu/goodrf/astoria_or/astoria_or_sketch.html

2 Johnson County Master Plan. 2004. Johnson County MAP 2020. Johnson County, Kansas.jcprd.com/pages/map2020

3 San Antonio Area Tourism Council. www.sanantoniotourism.com/ tourism.aspx. 4 The Project for Public Spaces has multiple articles on waterfront development atwww.pps.org/waterfronts/info/waterfronts_articles.

5 Geer, PhD. Donald. Omaha Recreational Trials: Their Use and Effect on Property Values and Public Safety.Program in Recreation and Leisure Studies. University of Nebraska, Omaha 2000.

20 River Network • RIVER VOICES • Volume 19, Number 1

t started the way many good thingsstart—with a little serendipity and alittle crisis. The serendipity was oneof timing: a River Alliance of

Wisconsin board member and newly electedState Representative took a long walk alonghis home river, the Root River in Racine. Hesaw a city struggling to rebuild itself in thepost-industrial age that had an underutilizedtreasure flowing through the heart of it. Thecrisis emerged with the public unveiling of adevelopment project at the mouth of theriver that would have cut off all public accessto the riverfront where it met Lake Michigan.After being approached by local citizens andthe City, the developer modified the plan toprotect public access to the riverfront(eventually, the development was shelvedaltogether).

The crisis wasaverted but interestin the river had beenrekindled. While theCity adopted several

The Root River in Racine, Wisconsin:

Planning for Riverfront Revitalizationplans for the management andredevelopment of city areas that touch onportions of the Root River, nocomprehensive plan existed that tiedtogether all the separate efforts torejuvenate and promote the river within theCity of Racine. And despite majorimprovements in the water quality of theriver over the last 30 years, many stillperceive the Root River as “dirty, industrialand contaminated,” as one resident stated.

Local residents and businesspeople cametogether in a series of “conversations” totalk about their hopes and visions for theRoot River. Eventually, the group evolvedinto the Root River Council.1 In partnershipwith the River Alliance of Wisconsin, theCouncil identified the need to have a moreformalized vision for what riverfront

redevelopment should look like to avoidhaving to “react” to proposals that havealready been developed and brought beforethe public.

In 2006, the Root River Council embarkedon a public outreach effort to developrecommendations for redevelopment of theRoot River waterfront based on fourguiding principles: 2

1) Reorient the city to its river;

2) Prompt robust, innovativedevelopment and growth with a mixof residential, retail and recreationalprojects;

3) Improve habitat and water qualityalong the river; and

4) Promote the participation of citizensand good public process in decisionsaffecting redevelopment of thewaterfront.

by Helen Sarakinos

River Alliance of Wisconsin

www.wisconsinrivers.org I

CASESTUDY

““JJuusstt wwaaiitt tt ii ll ll wwee sshhooww yyoouu oouurr rriivveerr!!””

RRoooott RRiivveerr CCoouunnccii ll mmeemmbbeerr CChhuucckk SSnnyyddeerr

Melissa Warnerfacilitating a groupplanning session

during a “Root RiverConversations”

charette. Photo credit: River Alliance of W

isconsin

TThhiinnkk uurrbbaann rr iivveerr ppllaannss aarree oonnllyy aacchhiieevvaabbllee iinn ssmmaallll cciittiieess?? TThhiinnkk AAggaaiinn..

TThhee LLooss AAnnggeelleess RRiivveerr iiss oonnee ooff tthhee mmoosstt cchhaannnneell iizzeedd rr iivveerrss iinn tthhee ccoouunnttrryy,, ii ttss cceemmeenntt

wwaall llss iinntteennddeedd ttoo pprroovviiddee tthhee qquuiicckkeesstt ccoonndduuiitt ffoorr wwaatteerr ttoo ffllooww tthhrroouugghh tthhee cciittyy iinnttoo

tthhee oocceeaann.. RRiivveerr aaddvvooccaatteess,, llaanndd oowwnneerrss,, ssttaattee aanndd llooccaall ooffffiicc iiaallss aanndd tthhee NNaattiioonnaall

PPaarrkkss SSeerrvviiccee’’ss RRiivveerrss,, TTrraaiillss && CCoonnsseerrvvaattiioonn AAssssiissttaannccee PPrrooggrraamm ssuucccceeeeddeedd,,

hhoowweevveerr,, wwhheenn iinn tthhee mmiidd 9900ss,, tthhee LLooss AAnnggeelleess RRiivveerr MMaasstteerr PPllaann wwaass ddeevveellooppeedd.. TThhee

ggooaallss ooff tthhee LLAA RRiivveerr MMaasstteerr PPllaann aarree ttoo::66

•• EEnnssuurree fflloooodd ccoonnttrrooll aanndd ppuubbll iicc ssaaffeettyy nneeeeddss aarree mmeett..

•• IImmpprroovvee tthhee aappppeeaarraannccee ooff tthhee rr iivveerr aanndd tthhee pprriiddee ooff llooccaall ccoommmmuunniitt iieess iinn ii tt..

•• PPrroommoottee tthhee rr iivveerr aass aann eeccoonnoommiicc aasssseett ttoo tthhee ssuurrrroouunnddiinngg ccoommmmuunniittiieess..

•• PPrreesseerrvvee,, eennhhaannccee aanndd rreessttoorree eennvviirroonnmmeennttaall rreessoouurrcceess iinn aanndd aalloonngg tthhee rr iivveerr..

•• CCoonnssiiddeerr ssttoorrmmwwaatteerr mmaannaaggeemmeenntt aalltteerrnnaattiivveess..

•• EEnnssuurree ppuubbll iicc iinnvvoollvveemmeenntt aanndd ccoooorrddiinnaattee MMaasstteerr PPllaann ddeevveellooppmmeenntt aanndd

iimmpplleemmeennttaattiioonn aammoonngg jjuurriissddiiccttiioonnss..

•• PPrroovviiddee aa ssaaffee eennvviirroonnmmeenntt aanndd aa vvaarriieettyy ooff rreeccrreeaattiioonnaall ooppppoorrttuunniitt iieess aalloonngg

tthhee rr iivveerr..

•• EEnnssuurree ssaaffee aacccceessss ttoo aanndd ccoommppaattiibbii ll ii ttyy bbeettwweeeenn tthhee rr iivveerr aanndd ootthheerr aaccttiivviittyy

cceenntteerrss..

LLooss AAnnggeelleess iiss mmaakkiinngg pprrooggrreessss.. AAss ooff FFeebbrruuaarryy 22000077,, tthhee LLooss AAnnggeelleess RRiivveerr

RReevviittaall iizzaattiioonn MMaasstteerr PPllaann ccoonnssiisstteedd ooff 223399 pprroojjeeccttss,, iinncclluuddiinngg tthhee eessttaabbll iisshhmmeenntt ooff

ppaarrkkss,, ooppeenn ssppaaccee,, ppeeddeessttrriiaann aanndd bbiiccyyccllee ppaatthhss,, bbrriiddggeess aanndd cchhaannnneell mmooddiiffiiccaattiioonn

pprroojjeeccttss,, aanndd ccrreeaattiioonn ooff aa fflloooodd ccoonnttrrooll cchhaannnneell..77

Volume 19, Number 1 • River Network • RIVER VOICES 21

The Root River planning process aimed tomeaningfully engage residents in a publicdialogue about the role of the Root River ina revitalized urban center. The Root RiverCouncil worked directly with differentstakeholders who have an interest in theriver: neighborhood associations andchurches, local businesses, developers,recreational, fishing and environmentalgroups, local schools, Root-Pike WatershedInitiative Network, Downtown RacineCorporation, members of Common Council

whose districts incorporate the Root Riverand staff from the City Departments ofPublic Works, Parks, City Development andthe Mayor’s office.

Both one-on-one interviews and facilitatedgroup meetings were used to receive publicinput. Interviews were designed todetermine how stakeholders perceive anduse the river and what they believe isneeded to make the river a more centralresource for the city. The public visioning

cont. on page 22

22 River Network • RIVER VOICES • Volume 19, Number 1

process for the Root River Plan was carriedout in three public charettes held in the fallof 2007 and facilitated by UW-Milwaukee’sCommunity Design Solutions.3 Theseworking meetings were designed for smallgroup discussions that enabled residents tolearn about the current condition of theRoot River and share their opinions about itsfuture. Additionally, the Root River Councildistributed surveys to Racine area residents.The survey responses and meeting

discussions shaped the recommendations inthe final plan. Melissa Warner, a charettefacilitator and Root River Council Member,was impressed with the level ofparticipation: “People came with interest,imagination and purpose. They contributedideas on how the riverfront activities wouldenhance life in Racine, with businesses,residences and entertainment in the urbansector, and recreational amenities andnatural enhancements on the upriver sector.The plan that emerged is one that has anexciting and attainable vision for the future.”

City Administration (specifically the Mayor’sOffice and Departments of CityDevelopment, Parks and Public Works) aswell as key aldermen and business interestswere kept up-to-date on the Root RiverCouncil’s activities. It was helpful to knowthat the Mayor and the City Planner saw thevalue of revitalizing the riverfront; bothendorsed and supported the public process.

The final plan, “Back to the Root: An UrbanRiver Revitalization Plan”4 was published in

Planning for Riverfront Revitialization, cont.

cont. from page 21 July 2008 and unanimously adopted inconcept by Common Council. The Plan’srecommendations included a mix of bothpolicy changes that continue to bedeveloped, as well as a series of items thatwere immediately “actionable”—from theplacement of canoe launches to workingwith City Parks Administration on placingvegetated buffers along riverfront parks—that groups of citizens could undertakeright away.

While the vision may take many years to befully realized, new initiatives have alreadybegun on the Root River. University ofWisconsin-Parkside opened anenvironmental education and communitycenter that offers recreation and educationon the Root River, just west of downtownRacine.5 The City completed acomprehensive water quality study of theriver in 2007 and, in partnership with theRiver Alliance of Wisconsin and thebusiness community, is preparing zoninglanguage to formalize and guidedevelopment of the river district. But mostimportantly, residents of Racine arerediscovering their riverfront one boat ride,bike ride and walk at a time, and arebeginning to see this namesake river as thesource of beauty and inspiration it can be.

““TThhrroouugghh aann eessttaabblliisshheedd nneettwwoorrkk ooff ccoommmmuunniittyyssttaakkeehhoollddeerrss aanndd cciittyy aaddmmiinniissttrraattiioonn,, tthhee

ppllaannnniinngg pprroocceessss ssuucccceessssffuullllyy ddeevveellooppeedd aa cclleeaarr,,ccoonncciissee aanndd ccoommmmuunniittyy ddrr iivveenn ppllaann..””

BBoonnnniiee PPrroocchhaasskkaa,, RRoooott RRiivveerr CCoouunncciill MMeemmbbeerr

1 www.backtotheroot.org2 This outreach campaign was made possible with funding from the Wisconsin Coastal ManagementProgram, the Racine Community Foundation and the CS Mott Foundation (by way of the River Alliance’sparticipation).

3 www4.uwm.edu/cds4 The final plan and related news articles are available at www.backtotheroot.org.5 www.uwp.edu/departments/community.partnerships/environmentalcentersrec.cfm6 ladpw.org/wmd/watershed/LA/larmp_mission.cfm7 www.lariverrmp.org/Media/documents/RiverPlanCNS.doc

Volume 19, Number 1 • River Network • RIVER VOICES 23

Root River Community Survey

Thank you for sharing your comments about the Root River!

What are your experiences with the Root River? Please check all that apply:

� Fishing � Walking

� Biking � Boating, what type ___________ (canoe, kayak, motor boat)

� Bird watching � I live nearby the river

� I work nearby the river � I own a business near the river

� Other _______________________

What do you love about the Root River?

What changes would you like to see?

Later this fall we will be holding meetings to discuss the future of the RootRiver in the downtown and upstream park areas (Island and Colonial,etc.). Would you be interested in attending a meeting to share yourconcerns and help plan improvements for the Root River?

� Yes � No

If yes, is a week night or Saturday better? Please check one.

� Weeknight � Saturday morning � Saturday afternoon

Which location would be most convenient for you to attend the meeting? Please check one.

� Downtown area � West 6th Street area

� Lincoln Park area � Location does not matter

If no, may we ask why not?

� Too busy � Not interested in meetings

� Other____________________________

Thank you for taking the time to complete this survey! If you would like to be contacted about future Root Rivermeetings please provide us with your contact information.

Survey the CommunityThe Root River Council used the following survey to capture information and ideas from the local community.

24 River Network • RIVER VOICES • Volume 19, Number 1

riends of the White River has established aninteractive, on-water learning experience onan urban segment of the waterway that runsthrough the state’s capital in Indianapolis.

Full day and half day trips utilizing livery-grade raftsallow students, policy makers, potential volunteers forstewardship projects and financial sponsors to paddlethrough a slow-moving stretch with diverse manmadeand natural features. They learn about environmentaland economic/historic aspects of the watershed,especially as they relate to its condition within the city.

The current sponsor, United Water, which operatesthe municipal wastewater treatment plant, has helped develop a unique component of theprogram that lets urban teens learn about ways they can take part in establishedimprovement and restoration efforts. They are also shown where they can return toresponsibly enjoy the river with friends and families. River School, another model programwhose partners include city and state agencies, offers a seasonal springboard for integratingeducation and community service.

Friends of the White River (IN)www.friendsofwhiteriver.org

www.river-school.org

VOIC

ES F

ROM

TH

E FI

ELD

ince 1999, SOLV’s Team Up For Watershed HealthProgram has been working to revitalize urbanwatershed sites in the greater Portland, Oregonarea. Harnessing volunteer power, SOLV is removing

invasive plants and replacing them with native trees and shrubsin riparian/wetland areas to improve water quality, lowerstream temperature and create habitat for urban wildlife. SOLVcrews and volunteers actively work the site for 3 years, whichincludes bank reshaping, log/bolder placement, bioengineering,etc., and then maintain and monitor it for another 5 years. In2008, Team Up For Watershed Health engaged 7,467volunteers on 64 sites comprising roughly 150 acres. One goalof the Team Up program is to engage community members to expose them to issuesconfronting watershed health and foster an ethic of stewardship.

SOLV (OR)www.solv.org

F

S

he Flint River in downtown Flint, Michigan has been channelized, dammed,concreted and forgotten. Recognizing the potential of the river, several Flintbusiness, education, philanthropy and nonprofit institutions started meetingand talking about how the river could serve as a focal point for revitalization

of the downtown area. That group formed the Flint River Corridor Alliance, workingtogether to transform the river from a distressed waterway to a natural resource that is anasset to the community.

The Flint River Watershed Coalition, a member of the Alliance, secured funds for a studyto help the city re-imagine what the Hamilton Dam could one day look like. In place of adilapidated, on the verge of failing dam, the city is now considering options that includeboat and fish passage, softened concrete banks and access to the river.

Flint River Watershed Coalition (MI) Flint River Corridor Alliance (MI)www.flintriver.org www.frcalliance.org

T

A volunteer plants trees atWade Creek at EstacadaHigh School in Estacada,Oregon in November, 2008.

Photo credit: Meghan Ballard, SOLV

Volume 19, Number 1 • River Network • RIVER VOICES 25

cont. on page 26

VOICES FRO

M TH

E FIELDookany/Tacony-Frankford (TTF)Watershed Partnership’s ModelNeighborhood Project is a neighborhoodbeautification and environmental

education program that centers on stormwatermanagement techniques. In each modelneighborhood, TTF meets with local communityorganizations and collects residents’ suggestions forneighborhood improvement. TTF then coordinatesthis input with Partnership resources and facilitatesprojects and events that beautify the neighborhoodand improve the watershed at the same time. Projects include volunteer clean-up days,neighborhood stormwater management demonstration site tours, rain barrel workshops,volunteer planting events, educational signage, watershed lessons in local schools and theinstallation of new best management practices such as a campus rain garden, an outdoorclassroom and a newly planted riparian buffer. We are focusing our initial efforts inconcentrated areas in order to impact watershed health and public awareness in a way thatexhibits tangible, positive change that the community can see and feel.

Tookany/Tacony-Frankford Watershed Partnership, Inc. (PA)www.ttfwatershed.org

T

he Rivanna Conservation Society (RCS)has a myriad of ways to care for andprotect the historic waterway oftenreferred to as “Mr. Jefferson’s River”

(Monticello is located on the banks of theRivanna River). Because erosion andsedimentation are among the Rivanna’s primarypollution sources, RCS has a robust bufferplanting program, a community wide chemicalwater quality monitoring program (biologicalmonitoring is done by RCS partnerStreamWatch), a bus and public buildingsposter project (the result of winning theCharlottesville Design Center’s DesignMarathon), a Rivanna River Sojourn and acomprehensive program of river trips. RCS alsohosts an annual Rivanna River Clean up fromthe headwaters to the confluence with the JamesRiver and facilitates mini clean ups throughoutthe year. RCS took the lead in the breaching ofthe Woolen Mills Dam in Charlottesville and haspetitioned the State Legislature to designate theRivanna as a Scenic River.

Rivanna Conservation Society (VA)www.rivannariver.org

e have partnered with trailand wetland groups onimproving the Wabash River.Principally working through

our nonprofit organization, Banks of theWabash, we are spreading “DeTrash theWabash” litter clean-ups along the citiesof the corridor. Utilizing the volunteerstrengths of the local group, we promotepairing conservation trails and ripariancorridors throughout the floodplain.Oftentimes, a river park or trailhead canbe developed as a local focus, meeting,interpretive/educational source and/oraccess point. Trail money is often foundfrom hospital boards (promotingfitness), and preservation funds mayarise from contacts cultivated among artlovers with a river-centric art show orpainting day.

Wabash River Heritage CorridorCommission (IN)

www.in.gov/wrhccwww.banksofthewabash.org

WT

BBRRIIGGHHTT IIDDEEAACCrreeaattee aa mmaapp ooff yyoouurr rriivveerr,,

nnoottiinngg aacccceessss ppooiinnttss,, ppoorrttaaggeess

aanndd rreessttiinngg ssiitteess,, aanndd pprroovviiddee

iinnffoorrmmaattiioonn oonn hhiissttoorriicc,, ccuullttuurraall ,,

eeccoollooggiiccaall oorr sscceenniicc ppooiinnttss ooff

iinntteerreesstt aalloonngg tthhee wwaayy..

Children hard at work during the RCS Youth Summit.

Photo credit: Michael Davis

At a local fair, kids learn about plants’ ability toabsorb and filter rainwater.

Photo credit: Mona Margarita

26 River Network • RIVER VOICES • Volume 19, Number 1

VOIC

ES F

ROM

TH

E FI

ELD

he Lower Passaic River in northernNew Jersey is a severely contaminatedurban river that has been neglected forover 50 years. Progress on restoring

the river by removing the toxic sediment has beenmoving at a snail’s pace. Fortunately, there is nowenough research available to choose a plan todeal with the contaminated sediment and restorethe river.

Pressure from the towns and cities surroundingthe Lower Passaic River is critical in order to continue pushing the cleanup project along.The Passaic River Coalition is creating a set of publications to convey the urgency that“Now is the time to clean the Passaic River.” The project is funded by an EPA TechnicalAssistance Grant and outlines actions needed to clean the river. This spring and summer,the Passaic River Coalition plans to give presentations about the Lower Passaic River inorder to raise local support by helping communities understand the benefits of a clean river.

Passaic River Coalition (NJ)www.passaicriver.org

T

or over the past three years, Friends of Alum Creek and Tributaries (FACT),has endeavored to remove two lowhead dams from the Alum Creek Riverbetween Wolfe Park-Academy Park and Nelson Park in Columbus, Ohio. TheOhio EPA conducted studies in 1996 and 2000 and found that areas of Alum

Creek did not meet water quality specifications. One reason for the poor water qualitywas because the water current slowed down behind the dams and organic material inthe water settled to the river bottom and decayed, resulting in sharp reductions indissolved oxygen. Improving water quality was the primary reason for the removal of thelowhead dams, but their elimination also addressed safety hazards and increasedaccessibility for recreational pursuits (e.g., canoeing).

While the physical extraction of both lowhead dams actually took less than one month,the preparations spanned four years. The process started in 2005 with receipt of an EPA319 Nonpoint Source Implementation grant. With guidance from FACT’s contractedenvironmental consulting engineering firm Burgess & Niple, Inc., biological, streambedphysical structure and property boundary surveys were completed, the US Army Corpsof Engineers Nationwide permit was received, and the conceptual and final technicaldesign plans were ultimately approved. The Wolfe-Academy Park lowhead dam was firstnotched on October 6, 2008 and soon after, on November 11th, Nelson Park lowheaddam was breached and fully removed.

Friends of Alum Creek (OH)www.friendsofalumcreek.org/sitev2/lowheaddamremoval.html

F

BBRRIIGGHHTT IIDDEEAAAAdddd ““ggrreeeenn bbuullkkhheeaaddss”” ttoo aarrmmoorreedd sshhoorreelliinnee wwaallllss iinn oorrddeerr ttoo pprroovviiddee