Capt . Luigi Mancuso Carabinieri Corps Rome Provincial Command Criminal Investigation Department

From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

-

Upload

council-on-foreign-relations -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

0

Transcript of From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

1/50

Council Special Report No. 55

April 2010

Vijay Padmanabhan

From Rome

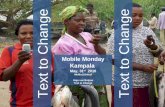

to KampalaThe U.S. Approach to the 2010 InternationalCriminal Court Review Conference

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

2/50

From Rome to Kampala

The U.S. Approach tothe 2010 International Criminal CourtReview Conference

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

3/50

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

4/50

Council Special Report No. 55

April 2010

Vijay Padmanabhan

From Rome to KampalaThe U.S. Approach tothe 2010 International Criminal CourtReview Conference

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

5/50

The Council on Foreign Relations is an independent, nonpartisan membership organization, think tank,

and publisher dedicated to being a resource for its members, government ocials, business executives,

journalists, educators and students, civic and religious leaders, and other interested citizens in order to

help them better understand the world and the foreign policy choices facing the United States and othercountries. Founded in 1921, the Council carries out its mission by maintaining a diverse membership, with

special programs to promote interest and develop expertise in the next generation of foreign policy lead-

ers; convening meetings at its headquarters in New York and in Washington, DC, and other cities where

senior government ocials, members of Congress, global leaders, and prominent thinkers come together

with Council members to discuss and debate major international issues; supporting a Studies Program that

fosters independent research, enabling Council scholars to produce articles, reports, and books and hold

roundtables that analyze foreign policy issues and make concrete policy recommendations; publishing For-

eign Afairs, the preeminent journal on international aairs and U.S. foreign policy; sponsoring Indepen-

dent Task Forces that produce reports with both ndings and policy prescriptions on the most important

foreign policy topics; and providing up-to-date information and analysis about world events and American

foreign policy on its website, CFR.org.

The Council on Foreign Relations takes no institutional positions on policy issues and has no aliation

with the U.S. government. All statements of fact and expressions of opinion contained in its publications

are the sole responsibility of the author or authors.

Council Special Reports (CSRs) are concise policy briefs, produced to provide a rapid response to a devel-

oping crisis or contribute to the publics understanding of current policy dilemmas. CSRs are written by

individual authorswho may be CFR fellows or acknowledged experts from outside the institutionin

consultation with an advisory committee, and are intended to take sixty days from inception to publication.

The committee serves as a sounding board and provides feedback on a draft report. It usually meets twice

once before a draft is written and once again when there is a draft for review; however, advisory committee

members, unlike Task Force members, are not asked to sign o on the report or to otherwise endorse it.Once published, CSRs are posted on www.cfr.org.

For further information about CFR or this Special Report, please write to the Council on Foreign Rela-

tions, 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10065, or call the Communications oce at 212.434.9888. Visit

our website, www.cfr.org.

Copyright 2010 by the Council on Foreign Relations Inc.

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

This report may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form beyond the reproduction permitted

by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law Act (17 U.S.C. Sections 107 and 108) and excerpts byreviewers for the public press, without express written permission from the Council on Foreign Relations.

For information, write to the Publications Oce, Council on Foreign Relations, 58 East 68th Street, New

York, NY 10065.

To submit a letter in response to a Council Special Report for publication on our website, CFR.org, you

may send an email to [email protected]. Alternatively, letters may be mailed to us at: Publications Depart-

ment, Council on Foreign Relations, 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10065. Letters should include the

writers name, postal address, and daytime phone number. Letters may be edited for length and clarity, and

may be published online. Please do not send attachments. All letters become the property of the Council

on Foreign Relations and will not be returned. We regret that, owing to the volume of correspondence, we

cannot respond to every letter.

This report is printed on paper that is certied by SmartWood to the standards of the Forest Stewardship

Council, which promotes environmentally responsible, socially benecial, and economically viable man-

agement of the worlds forests.

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

6/50

Foreword viiAcknowledgments ix

Council Special Report 1Introduction 3The Road to Now: The United States and the ICC 62010 Review Conference Agenda 12Recommendations 20

Endnotes 29

About the Author 31Advisory Committee 32

Contents

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

7/50

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

8/50

vii

Foreword

The United States has long been a leading force behind internationaleorts to bring the perpetrators of atrocities to justice. It spearheaded

the prosecution of German and Japanese ocials after World War IIand more recently supported tribunals to deal with events in Rwanda,the former Yugoslavia, and elsewhere. Washington has kept far moredistance, however, from the International Criminal Court (ICC).Although President Bill Clinton allowed U.S. negotiators to sign theRome Statute, the agreement that established the court, he and subse-quent presidents have maintained objections to elements of the courtsjurisdiction and prosecutorial authority. U.S. administrations have

since cooperated to varying degrees with the ICC, but the notion ofratifying the Rome Statute and joining the court has never been seri-ously entertained.

Even as a nonmember, though, the United States has importantinterests at stake in the ICCs operations. On the one hand, the courtcan bring to justice those responsible for atrocities, something withboth moral and strategic benets. On the other hand, there are fearsthat the court could seek to investigate American actions and prosecute

American citizens, as well as concerns that it will weaken the role ofthe UN Security Council (where the United States has a veto) as thepreeminent arbiter of international peace and security.

This Council Special Report, authored by Vijay Padmanabhan,examines how the United States should advance its interests at theICCs 2010 review conference, scheduled for May and June in Kampala,Uganda. After outlining the history of U.S. policy toward the court, thereport analyzes the principal items on the review conference agenda,most notably the debate over the crime of aggression. The conference

faces the task of deciding whether to adopt a denition of aggressionand, should it do so, whether and how to activate the courts jurisdiction

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

9/50

over this crime. Padmanabhan explains the important questions thisdebate raises.

Oering guidance for U.S. policy, the report recommends that theUnited States not seek to join the court in the foreseeable future. How-ever, Padmanabhan urges the Obama administration to make an activecase for its preferred outcomes at the review conference, including bysending a cabinet-level ocial to Kampala. On the question of aggres-sion, he calls for a strong stand against activating the ICCs jurisdiction.He argues that the proposed denition is overly vague, something thatcould endanger U.S. interests and risk embroiling the court in politicaldisputes over investigations. Should the review conference nonethe-

less adopt a denition, he advises the administration to emphasize thepotential drawbacks of activating the ICCs jurisdiction without con-sensus among its members. On other issues, the report urges the UnitedStates to contribute constructively to the evaluation of the courts func-tioning that the conference will carry out. And if the conferences over-all outcome is favorable, Padmanabhan concludes, the United Statesshould consider boosting its cooperation with the court in such areasas training, funding, the sharing of intelligence and evidence, and the

apprehension of suspects.From Rome to Kampala oers a timely agenda for U.S. policy at this

years review conference and toward the ICC in general. Its thoughtfulanalysis and detailed recommendations make an important addition tocurrent thinking on a set of issues with deep moral, legal, and strategicimplications.

Richard N. Haass

PresidentCouncil on Foreign RelationsApril 2010

Foreword

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

10/50

ix

I would like to thank this reports advisory committee for their timelyand incisive advice, suggestions, and support. While I understand that

several committee members do not agree with this reports approachor recommendations, their contributions were nonetheless extremelyvaluable. I am grateful to CFR President Richard N. Haass and Direc-tor of Studies James M. Lindsay, the publishing departments PatriciaDor and Lia Norton, and Research Associate Gideon Copple. I wouldalso like to thank Cathy Adams, Stefan Barriga, Todd Buchwald, JohnDaley, Arto Haapea, Matthew Heaphy, Karen H. Johnson, Mike Mat-tler, and William L. Nash, whose time and experience were essential to

the completion of this report.The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation supported this

project as part of its broader grant to the CFR Program on InternationalJustice, and its generosity is appreciated. This report was prepared withthe guidance of Program on International Justice codirectors JohnB. Bellinger III and Matthew C. Waxman, whose tireless eorts arereected in the nal report. Also special thanks to Walter B. Slocombefor chairing the advisory committee and providing thoughtful guidance

throughout the drafting process.Although many have contributed to this endeavor from conceptionto publication, the ndings and recommendations herein are solely myown, and I accept full responsibility for them.

Vijay Padmanabhan

Acknowledgments

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

11/50

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

12/50

Council Special Report

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

13/50

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

14/50

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

15/50

4 From Rome to Kampala

At the end of May 2010, the parties to the Rome Statute will holda review conference in Kampala, Uganda, that will test the new rela-tionship between the ICC and the United States. Given the importanceof the review conference, the Obama administration has decided thatthe United States will attend the Kampala Conference as an observer,and it is currently considering its negotiating strategy. A lesson learnedfrom U.S. participation in the Rome Conference that drafted the RomeStatute was that going in without a clear and carefully considered strat-egy severely limited U.S. inuence during the treaty negotiations. TheObama administration should therefore act quickly to solidify its nego-tiating position before the review conference.

The review conference will consider amendments to the Rome Stat-ute, including whether to authorize the court to prosecute the crime ofaggression, an oense over which the ICC has jurisdiction but whichwas left undened in the Rome Statute. As the United States takes cau-tious steps toward the ICC, adding aggression to the courts jurisdic-tion could widen the distance between the United States and the ICC,perhaps irreversibly. The primary U.S. objective for Kampala thereforeshould be to dissuade state parties from activating the courts juris-

diction over aggression in a manner that undermines the potentiallyvaluable work of the ICC in prosecuting atrocity crimes, as well as thesecurity interests of the United States.

Prosecuting aggression risks miring the court in political disputesregarding the causes of international controversies, thereby diminish-ing its eectiveness and perceived legitimacy in dispensing justice foratrocity crimes. ICC jurisdiction over aggression also poses uniquerisks to the United States as a global superpower. It places U.S. and

allied leaders at risk of prosecution for what they view as necessary andlegitimate security actions. Adding aggression to the ICCs mandatewould also erode the primacy of the UN Security Council in managingthreats to international peace. For these reasons, a decision among stateparties in Kampala to add aggression crimes to the ICCs jurisdictionwould jeopardize U.S. cooperation with the court, including possiblefuture nancial and infrastructure assistance, political and military sup-port in capturing suspects, and classied information sharing essentialto prosecutions. The ICC will be more successful with such assistance.

In addition to aggression, the review conference will also assess theperformance of the ICC since it began operations in 2002. The UnitedStates should seize the opportunity to emphasize specic ways to

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

16/50

5Introduction

improve the courts eectiveness in holding perpetrators of atrocitycrimes accountable. This will allow the United States to have greaterinuence with ICC parties and assert more strongly its leadership inseeking justice for the worst perpetrators of atrocities.

Achieving U.S. objectives at Kampala will not be easy. Althoughmany ICC parties are pleased to see the Obama administration engag-ing more actively with the court, the United States will be present at thereview conference only as an observer state with no immediate plans toratify the Rome Statute and become a state party. The absence of theUnited States from ICC institutions during the Bush administrationmay fuel resentment toward active U.S. involvement at the review con-

ference if U.S. positions are seen as obstructionist. Other states at theconference may also view U.S. positions on international justice issuessuspiciously in the aftermath of the invasion of Iraq, and because of theperception that the United States has failed to hold ocials account-able for detainee abuse. Meanwhile, in the United States, oppositionto or skepticism about the ICC within the Pentagon and Congress willlimit the Obama administrations ability to make substantial oers ofsupport to the court, especially during an election year.

Nevertheless, given its role as a global superpower and involvementin the long-term success of the ICC, the United States has the oppor-tunity to secure an outcome from the review conference that will fur-ther U.S. foreign policy interests. If U.S. concerns could be addressedat some future point through changes to the Rome Statute, it wouldbe desirable for the United States to become a member of the court.But because U.S. concerns about the ICC are bipartisan and reect theunique role and interests of the United States as a global military power

and permanent UN Security Council member, it is unlikely that theywill be suciently alleviated in the foreseeable future to make it wise orpolitically possible for the United States to join the court. Instead, U.S.policy should focus on increasing cooperation with the court whereU.S. and ICC interests align, while continuing to seek ways to protectU.S. security interests. In that vein, if the United States is able to achieveits objectives in Kampala, it should consider formalizing a working rela-tionship with the ICC as a nonparty partner through a U.S. agree-ment to support aspects of the courts work.

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

17/50

6

The United States has historically been at the forefront of eorts tocreate international institutions to prosecute atrocity crimes. After

World War II, the United States led Allied eorts to prosecute topGerman and Japanese ocials for atrocity crimes and crimes againstthe peace (aggression), overcoming British and Soviet arguments forsummary execution of the enemy leadership.

During the Clinton administration, the United States provided thepolitical impetus behind the Security Councils creation of interna-tional tribunals to prosecute those who committed atrocity crimes inRwanda and the former Yugoslavia. The United States was instrumen-

tal in funding and stang the tribunals, as well as in prodding statesto cooperate with them. These tribunals ushered in an era of special-purpose ad hoc international tribunals for Sierra Leone, Cambodia,and Lebanon that were endorsed by the Security Council and sup-ported by the United States.

The enormous cost and time-lag diculties involved in creating adhoc tribunals led the UN General Assembly to convene a conference inRome in 1998 for the purpose of establishing a permanent international

criminal court. The resulting Rome Statute grants the ICC jurisdictionover atrocity crimes. It also grants the ICC jurisdiction over the crimeof aggression, but only once a provision is adopted dening the crimeand setting out the conditions under which the court shall exercise juris-diction. The U.S. delegation made serious eorts in advance of andduring the Rome Conference to establish a court that would prosecute,at the request of the Security Council, those responsible for atrocitycrimes that national courts are unable or unwilling to prosecute. U.S.eorts were instrumental in ensuring that the ICC is used today only as

a last resort, and only to address the most serious atrocity crimes. Theprinciple that the ICC prosecutes crimes only where national courts

The Road to Now:The United States and the ICC

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

18/50

7The Road to Now: The United States and the ICC

with jurisdiction cannot or will not act is known as complementarity,and it remains an important tenet in guiding the courts actions.

Nevertheless, the United States was one of only seven states to voteagainst the nal Rome Statute. The United States had two main objec-tions. First, the text granted the ICC jurisdiction over crimes commit-ted by nationals of states that are not parties to the Rome Statute ifthe crimes occur in the territory of a state party. This provision poten-tially exposes U.S. military personnel involved in peacekeeping andother security operations to the risk of ICC prosecution, regardless ofwhether the United States joins the court.

Second, the Rome Statute created a self-initiating prosecutor

empowered to proceed with prosecutions without the consent of theSecurity Council. Although the Rome Statute grants the SecurityCouncil authority to delay investigations or prosecutions for up toa year, it rejected proposals by the ve permanent Security Councilmembers (P5) that conditioned jurisdiction on Security Council refer-ral. The United States argued that this structure was inconsistent withthe UN Charter, which grants the Security Council primary authorityin maintaining international peace and security.

The Clinton administration continued to participate in ICC meet-ings despite its vote at Rome. President Bill Clinton authorized U.S.negotiators to sign the Rome Statute on December 31, 2000, the lastpossible day for signature. One hundred thirty-nine states, including allof the P5 states except for China, signed the Rome Statute, but not allof them have ratied or formally become parties to it. President Clin-ton argued that the signature enhanced U.S. capacity to shape futuredevelopments at the ICC. But in a signing statement, Clinton added

that he was recommending president-elect George W. Bush not submitthe treaty to the Senate for advice and consent until U.S. concerns wereaddressed.

Upon taking oce, President Bush took active steps to distance theUnited States from the ICC. The ICC became operational on July 1,2002, when the Rome Statute came into eect. In advance of that event,the United States sent a letter to the United Nations, signed by thenundersecretary of state John R. Bolton, stating that the United Statesdid not intend to become a party to the Rome Statute.Undersecretary

of State for Political Aairs Marc Grossman explained that the letterwas designed to release the United States from the international legal

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

19/50

8 From Rome to Kampala

obligation created upon the Clinton administrations signature to actconsistently with the object and purpose of the Rome Statute. Nev-ertheless, Grossman identied common ground between the UnitedStates and ICC state parties, and ask[ed] those nations who havedecided to join the Rome Treaty to meet us there.

Later in 2002, Congress passed and President Bush signed theAmerican Service-Members Protection Act (ASPA). ASPA prohib-ited sharing classied information and other forms of cooperation withthe ICC, restricted aid to state parties that did not complete bilateralnon-surrender agreements (also called Article 98 agreements), shield-ing U.S. forces from ICC jurisdiction, and authorized the president

to use all means necessary to secure the release of U.S. or allied o-cials detained at the ICCs request. Consistent with ASPA, the UnitedStates began blocking reauthorization of UN peacekeeping missionswhose mandates did not guarantee immunity for U.S. forces from ICCjurisdiction. The United States also negotiated more than one hundredbilateral non-surrender agreements prohibiting transfer of Americancitizens to the ICC. All of these steps were widely perceived by ICCparties as part of a strategy by the Bush administration to undermine

the edgling court.U.S. policy toward the ICC began to shift in President Bushs second

term, as State and Defense department ocials recognized that someof these actions were undermining U.S. foreign policy interests,including important military relationships, and that the ICC servedU.S. interests in certain situations. The State Department legal adviserexplained in a series of speeches that the Bush administration sought amodus vivendi with the ICC based on mutual respect.The United

States was now willing to work with the ICC where they shared goalsrelated to international justice. In return, the United States requestedthat the international community respect its decision not to becomeparty to the ICC.

This new U.S. attitude manifested itself in two concrete ways. First,President Bush issued a series of waivers to the statutory funding cut-os, and in 2008 Congress repealed restrictions on provision of mili-tary aid to state parties. This shift on funding led the United States toabandon further eorts to secure bilateral non-surrender agreements.

Second, the United States cooperated with the ICC on Sudan andSierra Leone. The United States abstained on UN Security Coun-cil Resolution 1593, which referred the Darfur situation to the ICC.

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

20/50

9The Road to Now: The United States and the ICC

Following that referral, the United States was a strong supporter of theICCs eorts in Sudan, oering assistance to the prosecutor and block-ing eorts by African and Islamic states to delay investigations throughthe Security Council. The United States also agreed to allow the SpecialCourt for Sierra Leone to use the ICC facilities in The Hague for theprosecution of former Liberian president Charles Taylor.

Upon assuming oce in January 2009, the Obama administrationimmediately began a review of U.S. policy toward the ICC. Althoughelements of this review continue, Ambassador-at-Large for WarCrimes Issues Stephen J. Rapp stated publicly that the Obama admin-istration does not expect to present the Rome Statute to the Senate for

advice and consent in the near future. Nevertheless, the United Statesbegan participating in the ICCs Assembly of States Parties in Novem-ber 2009, and the Obama administration has committed to attendingthe Kampala Review Conference as an observer. The Obama admin-istration explained this decision as a way to express directly to ICCparties U.S. concerns regarding activation of the ICCs jurisdictionover aggression. The Obama administration has also continued coop-eration with active ICC investigations, recently announcing it would

assist in providing security to witnesses in Kenya who provide testi-mony to the ICC.

T ICC Tdy

Today 111 states have ratied and become parties to the Rome Stat-ute, including all members of the European Union, Australia, Canada,

Japan, and most of Latin America and Africa. In addition to the UnitedStates, nonparties include China, Russia, India, Iraq, and Israel.The ICC has exercised jurisdiction in ve situations to date. In three

of these situationsUganda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo(DRC), and the Central African Republicthe state itself referred thecase to the ICC. In Darfur, Sudan, the Security Council referred thecase to the ICC prosecutor, Luis Moreno-Ocampo, for investigation. InKenya, the prosecutor opened a formal investigation into postelectionviolence on his own initiative.

To date, the ICC has eight pending warrants for arrest and fourdefendants in custody awaiting trial. One other suspect, Sudanese rebelleader Bahr Idriss Abu Garda, has voluntarily appeared in front of the

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

21/50

10 From Rome to Kampala

ICC, but is not under arrest. The rst trial at the ICC began in January2009. Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, a Congolese warlord, is alleged to haverecruited and deployed children in armed conict. A second trial againsttwo other Congolese warlords is also under way. The ICCs third trial,against former DRC vice president Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo foralleged gender crimes in the Central African Republic, is set to beginin July 2010.

ICC prosecution eorts to date have been criticized for taking toomuch time to accomplish very little. Prosecutorial investigations, espe-cially of those in senior leadership positions, have been impaired byinsucient expert capability. Where cases have been built, they have

sometimes been quite small and of limited scope, with the high-prolecharges against Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir the major excep-tion. In numerous cases the ICC has also failed to secure the coop-eration of states to arrest suspects. Internal management issues anddiculties in gathering evidence in war-torn and conict-prone regionshave also slowed the processing of cases and undercut the courts abilityto begin more trials.

The fact that all cases have been brought against African defendants

has also fueled criticism among African states that the ICC is biased.African states have criticized proceeding with the case against Presi-dent Bashir, citing concerns about undermining peace eorts in Sudan.African critics have also complained about inadequate involvement ofvictims in the ICCs work, and insucient expenditure of resources toimprove the capacity of national courts to prosecute atrocity crimes.

Amid these problems, the primary U.S. concernfear that a self-initiating prosecutor would zealously pursue cases counter to U.S.

interestshas not materialized. The ICC rejected complaints againstBritish soldiers in Iraq, who were alleged to have violated targetingrules and assisted in detainee abuse perpetrated by American forces.The ICC prosecutor did so because of the relatively small scale of theallegations, and because an ongoing British investigation of the alle-gations suggested the matter was being handled appropriately at thenational level.

Nevertheless, concerns about the ICC in the United States remain,especially within the Pentagon and on Capitol Hill. National prosecu-

tors in several European countries, including the United Kingdom,Italy, and Spain, have commenced investigations of U.S. ocials and

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

22/50

11The Road to Now: The United States and the ICC

military personnel relating to military and intelligence actions in Iraq,Afghanistan, and in Europe itself, and critics allege regularly that civil-ian casualties from U.S. military operations amount to war crimes.These allegations heighten concerns in the Pentagon that the ICCmight launch similar inquiries in the future. These concerns would befurther exacerbated should the prosecutor open an investigation intowar crimes allegedly committed by Israeli defense forces in Gaza duringits 20082009 campaign.

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

23/50

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

24/50

132010 Review Conference Agenda

actions authorized by the Security Council. The charter entrusts theSecurity Council with authority to determine the existence of . . . anact of aggression and to take measures, including the use of force, inresponse to such a determination.

In 1974 the UN General Assembly adopted a draft denition ofaggression for the purpose of clarifying for states when use of forceran afoul of international law. It denes aggression as the use of armedforce by a state against the sovereignty, territorial integrity or politicalindependence of another state, or in any other manner inconsistentwith the Charter of the United Nations, as set out in this Denition.The General Assembly resolution contains a nonexhaustive list of acts

that may constitute aggression, while leaving open the possibility thatadditional acts may constitute aggression as determined by the SecurityCouncil. The resolution represented a political compromise, and manyinternational law experts believe this denition is too vague for the pur-poses of imposing individual criminal liability.

Given this history, it was not surprising that states were divided atRome on whether to include aggression within the list of crimes underthe jurisdiction of the ICC. Developing states and most European

Union members supported including aggression; the United States andUnited Kingdom opposed it, at least absent an acceptable denitionand preservation of the Security Councils primary role in this area.The nal text of the Rome Statute included aggression within the juris-diction of the ICC, but left for future amendment the denition of thecrime and the conditions under which the ICC could proceed with acase. Thus, the ICCs jurisdiction over the crime of aggression has notyet been activated.

A Special Working Group on the Crime of Aggression (WorkingGroup) has proposed a draft denition of aggression for considerationat the review conference. The proposed amendment is notable in threerespects. First, the same ambiguous denition of aggression used inthe 1974 UN General Assembly resolution is proposed for use by theICC. Second, only political and military leaders of states may perpe-trate aggression; nonstate groups and rank-and-le members of thearmed forces cannot. Third, jurisdiction is limited to an act of aggres-sion, which, by its character, gravity and scale, constitutes a manifest

violation of the Charter of the United Nations. Although this termis designed to limit the ICCs jurisdiction to the most serious cases ofaggression, manifest is not further dened.

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

25/50

14 From Rome to Kampala

Although the Working Group reached consensus on dening aggres-sion, it could not agree on the circumstances or conditions under whichthe ICC may exercise jurisdiction over aggression. Two issues dividedthe Working Group. The rst was whether the state whose nationals arealleged to have committed the crime must consent to the ICCs jurisdic-tion over aggression, or whether the consent of the victim state is suf-cient. States in favor of requiring the consent of the alleged aggressorstate argue that it is mandated by international law. Opponents of thisrequirement fear it would undermine the ICCs ability to prosecuteaggression.

Second, although the Working Group agreed that the ICC prosecu-

tor was obligated to inform the Security Council of an intent to pros-ecute, it disagreed on whether the prosecutor could proceed absentSecurity Council authorization. The United Kingdom and France haveargued that given the Security Councils primary role in regulating theuse of force, including the determination that acts of aggression haveoccurred, it must have the last word on whether the ICC may move for-ward with prosecutions. Opponents of a decisive Security Council rolehave pointed to the risk of deadlock in the council, noting the councils

historical reluctance to label actions as aggression. These states favoreither allowing the prosecutor to proceed on his or her own accordabsent Security Council action or providing the UN General Assemblyor the International Court of Justice authority to conclude that an act ofaggression has taken place, thereby activating ICC jurisdiction.

pTI s d I T sTs

Given these divisions, the review conference is faced with three options:

1. Activate the ICCs aggression jurisdiction. Doing so would require thereview conference to adopt both a denition of aggression (either theWorking Groups denition or a revised one) and agree on the condi-tions under which the ICC could proceed with a case, including therole of theSecurity Council. This would likely require a vote at thereview conference, because no consensus currently exists on these

issues.

2. Agree to a denition o aggression (either the Working Groups deni-tion or a revised one), but send the issues relating to the conditions under

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

26/50

152010 Review Conference Agenda

which the ICC could proceed with cases to a new working group or ur-ther consideration. This may be the most likely scenario, given thatseveral important state parties, including Japan, the United King-

dom, Australia, and Canada, have expressed opposition to proceed-ing on aggression without consensus.

3. Send the entire aggression issue to a new working group or urther con-sideration. The United States is the only country to have openly advo-cated for this approach.

The top priority for the United States at the review conferenceshould be to avoid amendment of the Rome Statute to activate jurisdic-

tion over aggression. The lack of clear legal standards dening aggres-sion poses dangers to the courts ability to function eectively and toU.S. security interests.

Unlike atrocity crimes, for which the content of international lawis reasonably well established, the law on resort to force is more neb-ulous. The proposed denition reects this uncertain state of the lawby merely listing acts that might constitute aggression without den-ing when those acts are unlawful. The denition does not address how

claims of self-defense or humanitarian necessity aect the categoriza-tion of the use of force as aggression. It is unclear, for example, whetherNATOs 1999 Kosovo intervention would be criminal under the Work-ing Group denition.

It is similarly unclear whether a preventive or preemptive strikeagainst a proliferator of weapons of mass destruction (WMD)forexample, a U.S. or Israeli strike against suspected Iranian nuclearweapon program siteswould constitute criminal aggression. If the

ICC claimed jurisdiction over such an attack, the ICC prosecutor andthe ICC would have authority, but no clear guidance in the Rome Stat-ute, to determine whether U.S. or Israeli action was an act of aggressionor justied as an action in self-defense.

A vague denition of aggression has practical consequences forthe ICC. The court would be immediately entangled in internationalcontroversies regarding which side used force lawfully in an armedconict. Had aggression jurisdiction been activated at Rome, the ICCmight have been asked to decide whether the use of force was unlaw-

ful in controversial situations involving state parties, including Frenchmilitary intervention in Cte dIvoire in 2002 (France is a party), Brit-ish and Polish invasion of Iraq in 2003 (United Kingdom and Poland

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

27/50

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

28/50

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

29/50

18 From Rome to Kampala

victims communities, including through education and greatervictim participation in trials.

State Cooperation with the ICC: State parties are expected to coop-erate with the ICC on a range of matters, including apprehension ofsuspects, evidence sharing, assistance in executing sentences, andnancial contributions for maintenance of the court. This sessionwill evaluate how to improve state cooperation.

National Prosecution Capacity: A core premise of the ICC is thatits jurisdiction arises only where national jurisdictions are unable orunwilling to prosecute. African states are concerned that the ICC

has not provided the technical and nancial assistance required toimprove the capacity of national courts to handle prosecutions of seri-ous crimes. This session will focus on how the ICC and other statesmay actively support national jurisdictions in capacity building.

Peace and Justice: African states have raised concerns about the com-patibility of ICC prosecutions with eorts to establish a lasting peacein societies emerging from conict. This session intends to identifyprinciples to guide eorts to seek international justice in areas with

ongoing hostilities.

other itemS

In addition to aggression and stocktaking, three other items are sched-uled for consideration at the review conference. First, the reviewconference will consider a resolution calling on states and regionalorganizations to consider cooperation with the ICC through designa-tion of facilities for housing ICC convicts. The goal of this resolution is

to encourage a geographically broader grouping of states to make pris-ons available.

Second, the review conference will consider whether to continue toallow states the right to opt out of the war crimes jurisdiction of theICC for its nationals for seven years after the state raties the statute.Colombia and France are the only parties that have availed themselvesof this option.

Third, the review conference will consider an amendment to the

Rome Statute to criminalize employing poison or poisoned weapons;employing asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases, and all analogous

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

30/50

192010 Review Conference Agenda

liquids, materials or devices; and employing bullets which expand oratten easily in the human body, which does not entirely cover the coreor is pierced with incisions in noninternational armed conicts. TheICC currently has jurisdiction over the same crimes in internationalarmed conicts.

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

31/50

20

The United States should not seek to become a member of the ICC inthe near term. When President Clinton authorized U.S. signature of

the Rome Statute in 2000, he stated that he would not recommend thathis successor transmit the treaty to the Senate until U.S. concerns hadbeen addressed. These concerns included then, and include now, theheightened risk to the United States of politicized prosecutions and thelack of sucient checks on the prosecutors power. Although the ICChas not sought to prosecute any U.S. or allied ocial during its sevenyears in operation, the increasing willingness of foreign national prose-cutors to investigate and prosecute U.S. ocials and military personnel

for actions in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere intensies concerns thatthe ICC may wade into similar debates in the future. As a superpowerwith global responsibilities and legally exposed military forces deployedthroughout the world, and as a permanent UN Security Councilmember with an interest in preserving that bodys primary responsibil-ity for ensuring peace and security, the United States therefore shouldnot for the foreseeable future retreat from its past objections and seekto become a party to the Rome Statute. Even if the Obama adminis-

tration or a successor administration were to submit the Rome Statuteto the Senate for approval, the Senate would not approve it unless thetreaty is amended or U.S. concerns are addressed in some other way.

That said, the United States should continue to build a cooperativerelationship with the ICC unless state parties make major decisionsin Kampala that undercut U.S. interests. The United States must actquickly, though, to solidify its negotiating position and make its casebefore the review conference. It should immediately undertake the fol-lowing steps.

The United States should send a cabinet-level representative to Kampala toemphasize the cooperation between the United States and the ICC in endingimpunity or perpetrators o atrocity crimes.

Recommendations

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

32/50

21Recommendations

The review conference will begin with a plenary session in which rep-resentatives of state parties and observer states will have the oppor-tunity to speak. Most states will be represented by ministerial-levelocials. The Obama administration should send the secretary of stateor national security adviser to provide an ocial statement on the rela-tionship between the United States and the ICC. The mere presenceof a cabinet-level representative will generate goodwill among the stateparties while emphasizing the seriousness of U.S. concerns.

A statement superseding the 2002 Bush administration statementthat broke o formal relations provides an opportunity to highlightthe improved U.S. relationship with the ICC and the signicant past

and potential U.S. contribution to international justice. Clarity aboutthe role the United States envisions for the ICC in prosecuting atrocitycrimes also increases the legitimacy of U.S. arguments against activat-ing aggression jurisdiction. The statement should include

support for Security Council referral of atrocity crimes to the ICC,including standards the United States may apply in making thisdetermination;

commitment to support ICC investigations and prosecutions ofatrocity crimes, in appropriate cases and where consistent withU.S. law;

oer of assistance with development of ICC oversight capacities,consistent with U.S. law;

commitment not to interfere with the decisions of states to becomeparties to the ICC; and

openness to consideration of other mechanisms to formalize U.S.-ICC cooperation.

The United States should prepare a report describing its experience in allour stocktaking areas.

Stocktaking gives the United States an opportunity to provide construc-tive input on the ICCs current operational shortcomings. Most stateparties want constructive evaluation of ICC performance. Responsive

and helpful U.S. input in this task could improve the ICC, and it couldalso increase U.S. inuence on the aggression debate. Encouraging afull and frank discussion of the current operational challenges facingthe court may help persuade state parties that it is inappropriate to add

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

33/50

22 From Rome to Kampala

aggression to the burden of the court.The United States is well situated to provide input on all stocktak-

ing sessions because of its traditional preeminent role in construct-ing and supporting international justice mechanisms. A U.S. reportwill improve the quality of the discussion in the stocktaking sessions,thereby increasing the likelihood of meaningful outputs emerging fromKampala. This report should cover several items:

Highlight lessons learned rom past U.S. eforts to cooperate with inter-national criminal tribunals. Many states are concerned about thepractical diculties of cooperation with the ICC. U.S. cooperationwith ad hoc tribunals, especially the International Criminal Tribu-nal for Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Criminal Tribunalfor Rwanda (ICTR), positions the United States to provide adviceon issues as diverse as sharing national security information with aninternational institution to working with local authorities to appre-hend war crimes suspects.

Emphasize U.S. eforts to improve the capacity o national courts toprosecute serious crimes, especially in Arica. African states are espe-cially concerned that the ICC is failing to provide adequate capacity-building support to national courts to prosecute crimes within theICCs jurisdiction. European states, by contrast, are reluctant toembrace a capacity-building role for the ICC, given an already over-stretched court. The United States should highlight the full rangeof U.S.-sponsored legal capacity-building projects, to demonstratecommitment to national prosecutions of atrocity crimes and toemphasize the continuing need to support such eorts as part of an

overall international justice strategy. Respond to concerns o Arican states regarding the impact on peace posed by international justice eforts. African states are concernedabout the eect of ICC indictments on securing peace in the DRCand Sudan. The United States has particular experience working tobalance peace and justice concerns from its involvement in endingghting in the former Yugoslavia. The successes and failures encoun-tered in resolving the conict in the former Yugoslavia, while pros-

ecuting those responsible for mass atrocities, provide useful lessonsfor future conicts.

Provide guidance on domestic eforts in the United States to recognize theimportance o a victims concerns in the justice process. African states

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

34/50

23Recommendations

are especially concerned with how to maximize the positive impactof international trials on victim groups, a legitimate concern giventhe poor performance of the ad hoc tribunals on this front. Victimgroups in the United States are among the best organized in theworld. U.S. experience in integrating victims concerns into domesticjustice procedures may provide useful insight on improving outreachfrom international tribunals.

The United States should push to avoid activation o the ICCs jurisdictionover the crime o aggression through a combination o strong red lines and

exible diplomacy.

A primary U.S. objective must be to avoid the activation of the crimeof aggression, which is contrary to the interests of both the ICC andthe United States. There are a range of possible outcomes that wouldsatisfy core U.S. concerns, and U.S. negotiators will need to adjust theirtactics accordingly as discussions unfold.

Much of the U.S. diplomatic outreach in advance of Kampala is besttargeted at capitals and at the political level, where some of the concerns

laid out above may receive greater consideration. For example, ocialsin capitals who regularly work with senior U.S. diplomats to managesecurity crises may be more sympathetic to security concerns than for-eign ocials who focus on international legal issues, and who typicallymake up foreign delegations to ICC discussions. Early initiation of thetargeted diplomatic overtures suggested below, especially to NATOallies and inuential regional powers such as Brazil and South Africa,is critical to laying the foundation for a successful review conference

outcome. The White House should be prepared to supplement eortsby U.S. diplomats in outreach to capitals.The United States should also work with states, such as the United

Kingdom and France, that share common interests on aggression,rather than stand out in front of them. The goodwill created by theObama administrations decision to participate at the review confer-ence could be quickly dissipated by an overly assertive American strat-egy, especially if critics successfully characterize the United States asobstructionist. U.S. negotiators should avoid, in particular, turning the

issue of aggression into a referendum on whether other countries wantthe future support of the United States.

Discussion of the aggression issue at Kampala is likely to proceed in athree-part sequence: (1) consideration of the Working Group denition

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

35/50

24 From Rome to Kampala

of aggression, (2) determination of whether a state must consent beforeits nationals are subject to investigation and prosecution for aggression,and (3) decision on whether the Security Council makes the denitivedetermination on whether prosecutions for aggression may proceed.

The United States should emphasize at the outset its concerns aboutthe proposed Working Group denition, which is vague in ways thatrisk miring the court in politicized investigations and fails to meetthe basic international legal principle of clarity to ensure fairness fordefendants. Even adopting this denition without activating aggressionjurisdiction could be damaging, because individual states or other inter-national courts might rely on it in ways that contribute to problematic

legal precedent.Although U.S. negotiators could suggest specic changes to the

text that would improve its viability as a criminal provision, thisstrategy is unlikely to succeed and could be counterproductive. TheWorking Group achieved consensus on the denition, creating asense among state parties that the issue is closed. The absence of theUnited States from the negotiating sessions of the Working Groupwill prompt many states to react negatively to even well-meaning de-

nitional proposals at this stage. Oering alternative language may alsocreate false expectations regarding U.S. support for aggression withan improved denition. Instead, clarity about U.S. concerns is likelythe most eective way to convince state parties that further thoughtshould be given to whether this denition advances the interests ofinternational justice.

Should the review conference adopt the denition of aggression pro-posed by the Working Group, U.S. eorts should shift toward empha-

sizing the lack of consensus that exists about the conditions underwhich aggression jurisdiction should be activated. Many state parties,including Australia, Canada, Japan, and the United Kingdom, are waryof radically amending the Rome Statute without overwhelming oreven unanimous consensus. Such consensus does not currently existwith respect to aggression. Rome Statute parties are evenly dividedon the question of whether the consent of the alleged aggressor state isrequired to activate aggression jurisdiction. And although most statesoppose limiting the ICCs jurisdiction over aggression to cases referred

by the Security Council, there is no consensus on what alternativelimits, if any, should be placed on the prosecutors discretion to proceedwith a case.

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

36/50

25Recommendations

However, some Latin American and African states view consensusas less important than activating aggression jurisdiction, and they maypush for votes at the review conference on contentious issues. Shouldthis occur, the United States must be clear that it will not support anoutcome that allows the prosecutor to proceed with aggression pros-ecutions absent the consent of both parties involved and approval of theSecurity Council.

On consent, the United States should stand with states arguing thatconsent of the aggressor state is required under international law as aprerequisite to ICC jurisdiction. A consent requirement protects sig-nicant U.S. interests by ensuring that no U.S. (or allied) personnel will

be prosecuted for aggression without the consent of the United States(or ally).

As for the role of the Security Council, arguments to preserve thelegal prerogatives of the Security Council in this area should acknowl-edge the organizations past shortcomings in responding to allegationsof aggression. Nevertheless, given the inherently political nature of eval-uating the use of force and the need to consider designations of aggres-sion in the context of broader eorts to resolve conicts and preserve

stability, there is no viable substitute for Security Council primacy inmaking aggression determinations. P5 eorts should emphasize thatjurisdiction over aggression will be most eective with assistance fromthe Security Council, which is ensured when the council refers the case.Emphasis should also be placed on the risks to the ICCs legitimacy inconducting atrocity crimes prosecutions if the court is viewed as politi-cized on account of its involvement with aggression.

The United States should make clear that if the state parties decide to

activate the courts jurisdiction over aggression without consensus (andby implication without addressing the most signicant U.S. concerns),the likelihood that important nonparty states, including the UnitedStates, Russia, and China, will join the court will be greatly diminished.Activating the courts jurisdiction over aggression also makes it harderfor the United States to cooperate with the court, even as a nonparty.This is not intended as a negotiating threat but as a statement of strate-gic and political realities.

The United States should avoid obstructing the decisions o state partieson items o the review conerence agenda where the United States lacks anational interest.

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

37/50

26 From Rome to Kampala

Given the need for the United States to be active on the issue of aggres-sion, and the opportunity to participate constructively in the stock-taking sessions, the delegation should remain neutral, or even voicesupport, on the remaining agenda items if they do not implicate signi-cant U.S. interests. The United States should, for example, defer to stateparties on the call for a greater number of facilities to house ICC con-victs. Widespread support exists for this resolution, and if and when theICC does convict and sentence defendants, it will need adequate facili-ties to house prisoners. The United States should also defer to state par-ties on the repeal of the seven-year opt-out provision. There is a divisionamong state parties between those who wish to repeal the provision as

an aront to the purposes of the Rome Statute and those who see noreason to tinker with a rarely used provision. Because the United Statesis unlikely to use such a provision, it should remain on the sidelines onthis issue.

In preparing for Kampala the U.S. government should determinewhether it has national security concerns about expanding the criminalprohibition of the use of various weapons to noninternational armedconict. The United States is currently engaged in a noninternational

armed conict with al-Qaeda. Extending any criminal prohibition frominternational to noninternational armed conict must be assessed inlight of current and anticipated military practices and existing treatycommitments on weapons use. The Department of Defense will be bestpositioned to determine whether this proposal is consistent with U.S.interests and operational requirements.

I U.S. objectives are achieved at Kampala, the United States should consider

steps to expand cooperation with the ICC.

The United States has security and moral interests in ensuring thatthose responsible for atrocity crimes be held accountable, and the ICCcan be an important tool to achieve these goals. With so many statesnow party to the ICC, the reality is that the ICC will be the presump-tive forum for future international trials. It is unlikely that state partieswould support creating new ad hoc tribunals like those for Yugoslavia,Rwanda, Sierra Leone, or other cases that predated the ICC.

At some future point, if U.S. concerns could be addressed throughchanges to the court, it would be desirable for the United States to becomea member. As a global superpower, the United States would gain direct

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

38/50

27Recommendations

and substantial inuence over the court and its work, including the selec-tion of ICC judges and prosecutors. The prosecutors set the agenda forthe ICC, which is important to the United States because of the courtspotential contribution to the stability of conict zones through rees-tablishment of the rule of law. The judges develop and interpret inter-national human rights law and the law of war in ways that could aectU.S. and allied military operations abroad. Putting the full weight of U.S.power and inuence behind the courts work would make it a powerfulinstitution for combating impunity of mass atrocity perpetrators.

But absent signicant changes to the ICC, U.S. membership remainsunlikely for the foreseeable future. The increased scrutiny of, and legal

challenges to, the actions of U.S. and coalition military forces in recentyears is likely to deepen concerns about the impact the ICC could haveon U.S. interests. Moreover, the Senate, which would be required toapprove the Rome Statute by a two-thirds vote, has been highly skep-tical of multilateral treaties seen as impinging upon U.S. sovereignty;the Senate would certainly not consent to the Rome Statute in its cur-rent form, and may never be willing to approve the treaty. Moreover, theICC has failed to accumulate a record of accomplishment to date that

could be used to overcome political resistance.If U.S. objectives are achieved at Kampala, however, the United States

could take a range of practical steps short of membership to improve theICCs ability to conduct investigations, apprehend suspects, and com-plete successful prosecutions. These steps include training and fundinginvestigators and prosecutors, providing political and military assis-tance to apprehend suspects, sharing intelligence and other evidence toaid case development, and giving assistance in developing an oversight

mechanism. Providing some of this assistance, though, would requirerepeal of all or parts of ASPA, which would be politically dicult for theObama administration.

The United States could also formalize its relationship as a non-party partner of the court. Assuming legal restrictions in ASPA couldbe addressed, the United States could commit to make available to thecourt signicant resources vital to its eective operation. For their part,the ICC and its state parties would recognize that the global securityresponsibilities of its U.S. partner raise unique or heightened concerns

with the court that call for careful discretion when U.S. interests ornationals are directly involved. Such recognition is dicult to squarewith universality, a principle at the heart of the international justice

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

39/50

28 From Rome to Kampala

agenda, but would open the door to eective collaboration between theICC and the United States in combating the worst atrocity crimes.

CClusI: pl d B yd

The ICC and its relationship with the United States are at a crossroads.Although the United States is unlikely to join the court any time soon,the outcome in Kampala will help dene the U.S. position toward thecourt for many years to come. If U.S. eorts are successful, opportu-nities exist to further strengthen cooperation with the court and itsstate parties that promote international justice while protecting U.S.interests.

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

40/50

29

. Recent studies have suggested steps the United States can take to improve coopera-tion with the ICC. See Lee Feinstein and Tod Lindberg,Means to an End: U.S. Inter-

est in the International Criminal Court (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press,2009); Report of an American Society of International Law independent task force,U.S. Policy Toward the International Criminal Court: Furthering Positive Engagement(Washington, DC: American Society of International Law, 2009); David Scheer andJohn Hutson, Strategy or U.S. Engagement with the International Criminal Court (NewYork: The Century Foundation, 2008). This report is focused on the more specic taskof how the United States should approach the review conference and the eect of thereview conference on its relationship with the ICC for years to come.

. States joining the United States in voting against the text at Rome were China, Israel,Iraq, Libya, Qatar, and Yemen.

. In proprio motu prosecutions, in order to proceed the prosecutor must receive ap-

proval of the Pre-Trial Chamber, which is composed of judges with criminal trial expe-rience. Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, Article 15(3)-(4).

. State Department press release: International Criminal Court: Letter to UN Secre-tary-General Ko Annan, May 6, 2002 (Appendix C).

. Marc Grossman, former U.S. undersecretary of state, American Foreign Policyand the International Criminal Court, speech delivered at the Center for Interna-tional Strategic Studies, May 6, 2002, http://www.coalitionfortheicc.org/documents/USUnsigningGrossman6May02.pdf.

. See, for example, John B. Bellinger III, former U.S. Department of State legal adviser,The United States and the International Criminal Court: Where Weve Been andWhere Were Going, speech delivered at DePaul University College of Law, April 25,

2008, and John B. Bellinger III, The United States and International Law, speechdelivered at The Hague, Netherlands, June 6, 2007.

. State Department spokesperson Ian Kelly explained, We will participate in thesemeetings as an observer and there will be an interagency delegation comprising of StateDepartment and Defense department ocials, which will allow us to advance, use andengage all the delegations in various matters of interest to the U.S., specically, our con-cerns about the denition of a crime of aggression, which is one of the main topics fordiscussion at this conference. This in no way suggests that we havewe dontwe nolonger have concerns about the ICC. We do have concerns about it. We have specicconcerns about assertion of jurisdiction over nationals of a nonparty state and the abil-ity to exercise that jurisdiction without authorizations by the Security Council. Ian

Kelly, U.S. Department of State spokesperson, press brieng remarks delivered No-vember 16, 2009, http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/dpb/2009/nov/131982.htm.

. Israel is not a state party, and the Palestinian Authority is not a recognized state, raisingserious questions about whether the ICC can investigate the claims consistent with the

Endnotes

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

41/50

30 From Rome to Kampala

Rome Statute. Article 12(3) of the Rome Statute allows states that are not parties to thestatute to accept the jurisdiction of the ICC with respect to a particular crime. Whilethe Palestinian Authority has led such a declaration covering crimes committed in

Gaza, it is unclear whether it can do so because it is not a recognized state. A decisionby the prosecutor to allow the case to proceed would suggest willingness to read theRome Statutes jurisdictional grant broadly.

. The IMT Statute for Nuremberg dened crimes against the peace as planning, prepa-ration, initiation, or waging of a war of aggression, or a war in violation of internationaltreaties, agreements or assurances, or participation in a common plan or conspiracy toachieve any of the foregoing.

. Resolution 3314 makes two changes to Article 2(4) of the UN Charter. First, it replacesthreat or use of force with armed force, suggesting mere threats do not amount toaggression. Second, it adds the term sovereignty, not found in Article 2(4). UnitedNations General Assembly Resolution 3314 (XXIX). Annex. UN Doc. A/RES/3314

(December 14, 1974).. The jurisdiction of the ICC in cases where a crime is committed by nationals of non-

parties in the territory of a state party is derived from the partys right under interna-tional law to prosecute crimes that occur in its territory. If the crime of aggression takesplace solely in the territory of the aggressor state, there would be no basis to proceedwith claims against the aggressor states nationals without its consent. Additionally,Article 121(5) of the Rome Statute limits application of amendments to state partiesnationals who have consented to the amendment, meaning aggression prosecutionscannot proceed against a state partys nationals without its prior consent to the courtsjurisdiction over aggression.

. Article 121(3) of the Rome Statute allows for adoption of amendments at a review

conference with a majority of two-thirds of state parties where consensus cannot bereached. Under Article 121(5), if the amendment is to the substantive oenses of theRome Statute, the amendment goes into eect for state parties that accept the amend-ment one year after ratication. The court will not assume jurisdiction over nationalsof state parties that have not ratied the amendment. Article 121(4) provides that otheramendments to the Rome Statute go into force once seven-eighths of states have rati-ed the amendment.

. This assumes that ICC parties had not agreed to require the consent of both parties forinvestigation of alleged acts of aggression.

. Any attempt to do so would raise serious constitutional questions about whether thejudiciary could adjudicate the legality of the decision to use force consistent with sepa-ration of powers.

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

42/50

31

Vijay Padmanabhan is a visiting assistant professor of law at YeshivaUniversitys Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law. Professor Padma-

nabhan teaches the law of war and human rights law, and has publishedon topics in international criminal law and international humanitarianlaw. From 2003 to 2008, he was an attorney-adviser in the oce of thelegal adviser at the U.S. Department of State. While there he served asthe departments chief counsel for law of warrelated litigation, includ-ing collaborating with the U.S. Department of Justice on the Boumedi-ene, Omar, and Hamdan cases in the U.S. Supreme Court. He also wasthe department liaison to the oce of military commissions in the U.S.

Department of Defense. Padmanabhan was a law clerk to the Honor-able James L. Dennis of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.He received his BSBA summa cum laude from Georgetown Universityand JD magna cum laude from New York University School of Law.

About the Author

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

43/50

32

John B. Bellinger III, Project Director,ex ocio

Council on Foreign Relations

Matthew C. Waxman, Project Director,ex ocio

Council on Foreign Relations

Elliott Abrams, ex ocioCouncil on Foreign Relations

Kenneth AndersonAmerican University

Gary J. BassPrinceton University

Kenneth J. BialkinSkadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP

David M. CraneSyracuse University

Daniel J. DellOrtoAM General LLC

Richard DickerHuman Rights Watch

Mark A. DrumblWashington & Lee University School o Law

Richard H. Fontaine Jr.Center or a New American Security

Michael J. GlennonThe Fletcher School o Law & Diplomacy,Tuts University

Marc GrossmanThe Cohen Group

Larry D. JohnsonColumbia University School o Law

David A. KayeUniversity o Caliornia, Los Angeles

Neil KritzU.S. Institute o Peace

Tod LindbergHoover Institution, Stanord University

Troland S. LinkDavis Polk & Wardwell LLP

Michael J. MathesonGeorge Washington University Law School

Judith A. Miller

Sean D. MurphyGeorge Washington University Law School

Michael A. NewtonVanderbilt Law School

Stewart M. Patrick, ex ocioCouncil on Foreign Relations

Pierre-Richard ProsperArent Fox PLLC

Stephen G. RademakerBGR Group

Kal RaustialaUniversity o Caliornia, Los Angeles

Stephen RickardOpen Society Institute

Nicholas RostowState University o New York

Advisory Committee forFrom Rome to Kampala

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

44/50

33Advisory Committee

David J. ScheerNorthwestern University School o Law

Walter B. Slocombe

Caplin & Drysdale, Chartered

Adam M. SmithCovington & Burling LLP

Gare A. SmithFoley Hoag LLP

Jane E. StromsethGeorgetown University Law Center

William H. Taft IV

Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson, LLPRuti G. Teitel

New York Law School

Beth Van SchaackSanta Clara University School o Law

Kurt Volker

Center or Transatlantic Relations,Paul H. Nitze School o AdvancedInternational Studies

John L. WashburnUnited Nations Association o the U.S.A.

Ruth WedgwoodPaul H. Nitze School o AdvancedInternational Studies

Noah Weisbord

Duke University School o Law

Clint Williamson

Note: Council Special Reports reect the judgments and recommendations of the author(s). They do not

necessarily represent the views of members of the advisory committee, whose involvement in no way

should be interpreted as an endorsement of the report by either themselves or the organizations with which

they are aliated.

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

45/50

34

Strengthening the Nuclear Nonprolieration RegimePaul Lettow; CSR No. 54, April 2010

An International Institutions and Global Governance Program Report

The Russian Economic CrisisJerey Manko; CSR No. 53, April 2010

Somalia: A New ApproachBronwyn E. Bruton; CSR No. 52, March 2010A Center for Preventive Action Report

The Future o NATOJames M. Goldgeier; CSR No. 51, February 2010An International Institutions and Global Governance Program Report

The United States in the New AsiaEvan A. Feigenbaum and Robert A. Manning; CSR No. 50, November 2009An International Institutions and Global Governance Program Report

Intervention to Stop Genocide and Mass Atrocities: International Norms and U.S. PolicyMatthew C. Waxman; CSR No. 49, October 2009An International Institutions and Global Governance Program Report

Enhancing U.S. Preventive ActionPaul B. Stares and Micah Zenko; CSR No. 48, October 2009A Center for Preventive Action Report

The Canadian Oil Sands: Energy Security vs. Climate ChangeMichael A. Levi; CSR No. 47, May 2009A Maurice R. Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies Report

The National Interest and the Law o the SeaScott G. Borgerson; CSR No. 46, May 2009

Lessons o the Financial CrisisBenn Steil; CSR No. 45, March 2009A Maurice R. Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies Report

Global Imbalances and the Financial CrisisSteven Dunaway; CSR No. 44, March 2009A Maurice R. Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies Report

Council Special ReportsPublished by the Council on Foreign Relations

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

46/50

35Council Special Reports

Eurasian Energy SecurityJerey Manko; CSR No. 43, February 2009

Preparing or Sudden Change in North KoreaPaul B. Stares and Joel S. Wit; CSR No. 42, January 2009A Center for Preventive Action Report

Averting Crisis in UkraineSteven Pifer; CSR No. 41, January 2009A Center for Preventive Action Report

Congo: Securing Peace, Sustaining ProgressAnthony W. Gambino; CSR No. 40, October 2008A Center for Preventive Action Report

Deterring State Sponsorship o Nuclear TerrorismMichael A. Levi; CSR No. 39, September 2008

China, Space Weapons, and U.S. SecurityBruce W. MacDonald; CSR No. 38, September 2008

Sovereign Wealth and Sovereign Power: The Strategic Consequences o American IndebtednessBrad W. Setser; CSR No. 37, September 2008A Maurice R. Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies Report

Securing Pakistans Tribal BeltDaniel Markey; CSR No. 36, July 2008 (Web-only release) and August 2008A Center for Preventive Action Report

Avoiding Transers to TortureAshley S. Deeks; CSR No. 35, June 2008

Global FDI Policy: Correcting a Protectionist DritDavid M. Marchick and Matthew J. Slaughter; CSR No. 34, June 2008A Maurice R. Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies Report

Dealing with Damascus: Seeking a Greater Return on U.S.-Syria RelationsMona Yacoubian and Scott Lasensky; CSR No. 33, June 2008A Center for Preventive Action Report

Climate Change and National Security: An Agenda or ActionJoshua W. Busby; CSR No. 32, November 2007A Maurice R. Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies Report

Planning or Post-Mugabe ZimbabweMichelle D. Gavin; CSR No. 31, October 2007A Center for Preventive Action Report

The Case or Wage InsuranceRobert J. LaLonde; CSR No. 30, September 2007A Maurice R. Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies Report

-

8/8/2019 From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court Review Conference

47/50

36 Council Special Reports

Reorm o the International Monetary FundPeter B. Kenen; CSR No. 29, May 2007A Maurice R. Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies Report

Nuclear Energy: Balancing Benets and RisksCharles D. Ferguson; CSR No. 28, April 2007

Nigeria: Elections and Continuing ChallengesRobert I. Rotberg; CSR No. 27, April 2007A Center for Preventive Action Report

The Economic Logic o Illegal ImmigrationGordon H. Hanson; CSR No. 26, April 2007A Maurice R. Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies Report

The United States and the WTO Dispute Settlement SystemRobert Z. Lawrence; CSR No. 25, March 2007A Maurice R. Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies Report

Bolivia on the BrinkEduardo A. Gamarra; CSR No. 24, February 2007A Center for Preventive Action Report

Ater the Surge: The Case or U.S. Military Disengagement rom IraqSteven N. Simon; CSR No. 23, February 2007

Darur and Beyond: What Is Needed to Prevent Mass AtrocitiesLee Feinstein; CSR No. 22, January 2007

Avoiding Conict in the Horn o Arica: U.S. Policy Toward Ethiopia and EritreaTerrence Lyons; CSR No. 21, December 2006A Center for Preventive Action Report

Living with Hugo: U.S. Policy Toward Hugo Chvezs VenezuelaRichard Lapper; CSR No. 20, November 2006A Center for Preventive Action Report

Reorming U.S. Patent Policy: Getting the Incentives RightKeith E. Maskus; CSR No. 19, November 2006A Maurice R. Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies Report

Foreign Investment and National Security: Getting the Balance RightAlan P. Larson and David M. Marchick; CSR No. 18, July 2006A Maurice R. Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies Report