Frascari - 2009 - Lines as Architectural Thinking

-

Upload

mennatallah-msalah-el-din -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of Frascari - 2009 - Lines as Architectural Thinking

-

7/28/2019 Frascari - 2009 - Lines as Architectural Thinking

1/14

-

7/28/2019 Frascari - 2009 - Lines as Architectural Thinking

2/14

MARCO FRASCARI

LINES AS ARCHITECTURAL THINKING

Architecture stems from a sapient workingtogether of writing, drawing, and constructionlines. The critical study of genetic architecturalrepresentations by examination of the sedimen-tation of architectural materiality inscribed inweatheredboards,papers and models developsthe ability of architects to become architectu-rally conscious. Architectural lines are material,

spatial, cultural and temporal occurrences of rened multi-sensorial and emotional under-standings of architecture. Architectural linescreate a graphesis, a course of actions basedon factures by which architects actualizefuture and past architecture into representa-tions. Architectural drawings must not beunderstood as visualizations of building, butas essential architectural factures. LeonBattista Albertis term lineamenta carriesembedded in itself the idea of facture sinceAlbertis understanding of lineamenta derivesfrom the use of tracing lines, ropes, ribbons,strings or threads mostly made with axbres and used by the builder on construc-tion sites during the facture of buildings.

Tota res aedicatoria lineamentis et structura constituta est.

Leon Battista Alberti, De re aedicatoria

ISSN 1326-4826 print/ISSN 1755-0475 online 2009 Taylor & FrancisDOI: 10.1080/13264820903341605

-

7/28/2019 Frascari - 2009 - Lines as Architectural Thinking

3/14

Architecture is a constructed virtueor better,she is the Queen of Virtues, as Andrea Palladio,a Renaissance architect, labelled her on thefrontispiece of his treatiseby which humansinteract spatially, tectonically and culturally witha region that they modify with thoughtful tracing of lines on the paper and on the ground to their advantage as a proper expression of their humanity. Not too long ago, architecturaldrawings were made in limited quantity. It used to be that only a few lines were necessary toaccomplish the task of representing future or

past buildings. Nowadays, we need an incon-ceivable number of lines even to describe the tiniest building. Consequently, the favouriteaphorism used by Carlo Scarpa, an extra-ordinary Venetian architect of the late twen- tieth century gifted with an absolute ability of conceiving building by drawing, should beupdated sourly to reect this overwhelmingcondition. Scarpas . . . nullo dies sine linea[donot let a day pass by without line], should bealtered into . . . nullo dies sine mille lineae[do

not let a day pass by without a thousand lines].The overpowering expectation to producelines for erecting an edice or a small housedoes not allow drawing hesitation anymore.

A hesitated set of architectural lines is asensible and sensitive form of drawing, dwellingon pensive borders ceaselessly, where thedrafting and writing of lines is an alluringdiscourse, buzzing backward through history and igniting genetic analogies as a way to see the real nature of the undisciplined discipline of architecture beyond the functional quotidian.Hesitate comes from Latin, meaning to stick, to stammer. It is a holding back in doubt,having difculty in doing or making something.In our condent age of aggressively digitalimaging and atrociously hasty processes of construction, linear hesitations must bebrought back into architects drawings to make

them truly heuristic devices again. It is a slowprocess of architectural sapience based on theideas of lingering, savouring and touching; it isbased on the adagio time and common places,proverbs or rule of thumbs.

Labour intensive, slow architectural lines be-long to the aging cellar of a rened multi-sensorial and emotional understanding of architecture. Without a lingering draftingsapience, there is not architecture and thedrafting sapience originates within architects

compelling material imagination. Sapiencestems from thoughtfully sensible considerationson how material transforms into matter and this is the foundation of thinking in architecture.Sapience comes from sapere a slow tactilesavoir which is at the same moment slow timeand savouringthat operates in the samemanner by which the sense of taste discernsdifferent essences or avours. 1 During thedrafting of a building and its constructivedetails, a ne architect discerns and savours

architectural objects and their causes.

The protracted translation of lines of drawingsinto building lines and vice versa is the mostessential phase of the architectural process of imagination by which buildings are conceivedand erected, since the ontogenesis of archi- tectural lines assimilates itself the primary processes of designation that take place onconstruction sites. Lines are tense enigmasslowly translated on paper and their solutiondetermines architects ability to consider andsavour the facture of the building.

Architecture is built to transcend its epoch; soalso are architectural drawings. Buildings outlive their builders, so also do drawings outlive their drafters. The implication of this parallelism is that both buildings and drawings carry in their facture the constructed virtue of architecture.

ATR 14:3-09 LINES AS ARCHITECTURAL THINKING

201

-

7/28/2019 Frascari - 2009 - Lines as Architectural Thinking

4/14

Buildings should respond to the requests of their own epoch, but at the same time, they should be able to adapt to requests thatcannot be anticipated or even imagined.Similarly, architectural drawing done to accom-plish the exclusive requests of a specicbuilding construction should be able to beread for searching answers to constructiverequirement of past and future buildings.

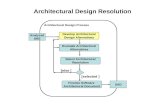

Drawings as Architectural Factures

Recognizing that even more so in our age of digital imaging the great majority of architectsdo not build buildings, but merely draw them,as the late Robin Evans had powerfully pointed out a few times. 2 The aim is todemonstrate that the tracings of real andproper architectural drawings are not obviousand impartially objective as the marketing for digital architectural instruments try to con-vince architects, builders and clients in their

market campaigns. While recognizing theseambiguous conditions, we do not presume that architectural traces are either worldly or unworldly, existing or non-existing, physical or mental, subjective or objective. Architecturaldrawing must avoid such labels. In real acts of architectural drawing that which is marked,inked, pencilled, brushed or chalked comesinto being through the sapience of a factureand not through any Cartesian rationalprocess of matheme even when Cartesianplans of representation are used to trace theimage. Architectural drawing is, in other words, wholly based on a sapience of materialmanifestations within which tangible linesbecome carriers of uid and invisible links that guide intangible thoughts.

The intention is not to develop a reactionary proposition trying to ght back the professional

exploitations of digital representations and their scientintically presentations, but rather, to pose a question that could lead to a newway of obtaining a better grasp and handle on the fresh graphesis afforded by computers. 3 A graphema, an emotional piece of drawing,should not become a mathema, an indifferentdigital drawing and an after-the-fact analysis of algorithmically produced representations. Anarchitectural graphema should tackle materiality and sensuality of the built world by generatingsapient hybrid representations that can allow

architectural students and professionals to fully utilize the potentiality of digital drawings. Theepistemology of architectural graphesis must besynthesized in vague representations located at the chaotic and in sapience, the cunning junction of the humanistic and scientic con-cepts of knowledge. 4

Pulling pieces of geometry, geology, alchemy,philosophy, politics, biography, biology, mythol-ogy, and philology from alien territories,

architects should write and draw with hesita- tion, discovering the multiple aspects of architectural graphesis, a generative graphicprocess understood in its slow making. Thefruitful vagueness ruling architectural graphesiscomes from the ambiguity embodied in theLatin spell: nullo dies sine linea, where linea(line), an heuristic device, must be understoodas a line of writing, as a line in a drawing or as the pulling of a line on a construction site, butnot as linearity.

Architecture results from a sapient interfacingof writing, drawing and constructing lines.These lines are investigational media that serveas a point of departure for arriving at asymbiosis between materials and culture,dening everything from the tectonic character of rooines to the bodily prole of a bathtub.Images are written and words are drafted, and

FRASCARI

202

-

7/28/2019 Frascari - 2009 - Lines as Architectural Thinking

5/14

-

7/28/2019 Frascari - 2009 - Lines as Architectural Thinking

6/14

charcoal mark, wash run, smudge, erasure,pentimento and blur must have a signallingfunction and a meaning. Again, labour intensiveand slow architectural drawings belong to theaging cellar of a rened multi-sensorial andemotional understanding of architecture. Our contemporary world is based on unnecessary hastiness: temporal speed and material rushinggrowth are the prevailing attitudes of our ageand unhurried attitudes seem to imply stagna- tion and inertia. We live in a constant rush andbuilding and designing no longer proceed in

proper pace; everything has become increas-ingly fast. The design and construction of abuilding exist within the overlapping of threespheres of time constrains: the urge of nance, the push of technology and the pull of fashion.Consequently, building and drawing are pre- judiced by hasty occasions and respond tointerest rates and rises in site prices ascribing avalue to each moment. Architectural drawingsare also pulled towards speediness because it isdigitally possible. Computer technology speeds

up tasks and, in theory at least, increasesprecision and photographic reality, but thedrawings produce buildings that lack grip, lack traction in time.

For the most part, architectural criticism andhistory have concentrated on the large-scalequestion instead of focusing on the geneticprocesses in architecturethe process of assembly and interaction between differentkinds of signs productions, and the interfacingbetween media and supports. There is nomeaningless mark in a genetic architecturalrepresentationeven accidental marks play amajor role in the coming about of a construc- tion. The study of genetic architectural repre-sentations is focused on the cognitive factures.These cognitive congurations map out ex-pressions and patterns recording the physicalor mental actions corresponding to the multi-

ple and interfacing stages of architecturalprojects. The critical study of genetic architec- tural representations by examining the sedi-mentation of architectural materiality inscribedin weathered boards, papers and modelsdevelops the ability of architects to becomearchitecturally conscious. Although the objectis the study of tangible documents such asarchitects sketches, notes, drafts, models andblueprints, the real scope is something muchmore intangible. It is the detection of themovements of generating architectural con-

ceiving. Most of these movements are notoptically real, but imaginatively real.

A critically constructed genetic analysis of architects drawings is the most effective andefcient way to learn architecture. The study of genetic representations is generally concrete,for it never posits an ideal architecture beyond those documents but rather strives to recon-struct, from all available evidence, the chain of events present in processes. A critically con-

structed genetic analysis is a continuation of thearchitectural imaginative act itself. The study of beginnings, of alternative and concurrentarchitectural representation, makes it possible to rethink and rene complex theoreticalquestions of the efcacy of indirect perceptionin producing architecture.

What kind of union of maternal and materialmimesis is required for returning to architec- tural representations within the sensually captivating play of lines that presently is mostly lacking from the contemporary architecturalimagining? Maternal edication and materialconstruction no longer coincide naturally inarchitecture. An edifying conjunction that wasonce commonedication comes from edi-cenow requires careful calibration in theconception, construction and inhabitation of buildings. An understanding of the crisis taking

FRASCARI

204

-

7/28/2019 Frascari - 2009 - Lines as Architectural Thinking

7/14

place within the play of lines necessary for achieving enchantment in architecturaldrawings cannot be pursued without tackinga close look at the geometry used on theconstruction site. Geometry used on siteoccupies a central position in the developmentof architecture, both in the way geometry tends to be related to the expression of ideasits inextricability from languageand in the way we understand these ideas, somehow,in geometrical terms.

The architectural profession has embraced theuse of digital information without a proper critical reection on the conversion of the tradition of architectural drawings into thedigital. Many hand-drafted drawings are per-suasive choreographic notations of architectur-al thinking, since they articulate the tangible andintangible relationships existing between theparts composing a construction. Nowadays,hand-generated drawings are typically regardedas a distressing unprofessional occurrence by

many professionals and their quintessentialedifying capability of portraying architectural thinking has become merely a selling graphicstrategy for giving a pseudo-aura to mechanicalrenderings. The insipid aftermath imitations of handmade artistic drawings generated with the help of fancy graphic lters after digitaldesigning has taken place cannot substitute thefreehand sketches and drawings. By recognizingpossible functions and meanings in drawings, by nding and adapting new forms into theevolution of the architecture under examina- tion, these hand-generated graphema play acrucial heuristic role in the conception of buildings, when architects draw to explorearchitectural projects by recording ideas, no- tions and concepts.

For architects, drawing has not only aninformative substance, but also formative

consequences, since they weave beautifulconstructional thoughts into images. Althoughmany architects have been trained or are trained in drawing within the tradition of thene arts, hardly are they taught the ingeniousart of architectural drawings in an explicitmanner. They learn to draw as painters or sculptures, but then it is up to them to discover how to draw architecture. Architecture is never completely integrated with the other arts thatuse drawings. In the initial phases of humanitysdrawing development, architectural drawings

had many more points in common with thepreparatory procedures present in the other arts, but as artists developed and rened theart of drawing as a ne art in itself; architectsgrew their own understandings of drawing as anindependent facture with its own graphesis.

As alive oral, written and drawn interactions,architectural factures and their graphesis servenot only as practicum for recycling existingarchitectural thoughts and dreams, but to

become continuously fertile settings for pro-ducing new thoughts and novel dreams thatbear great consequences for the future of thehumans that will inhabit them. Architects with their drawings participate in the praxis of anarchitectural cosmopoiesis, a world-making that gives rise to the synaesthetic landscapesof intimacy and participation, an interplay of signs that transfers worlds that often mighthave remained unknown into a world of architectural materials and substances. 7 Archi- tectural nubs and their translations into visualmedia proceed via deeply-felt interplays of cultural, demographic, socioeconomic, tempor-al and spatial variables, ultimately assessingarchitectural conceptions into a trans-historicalmeasure of tradition and novelty.

As graphic translators, architects perform theall-important function of bringing into the

ATR 14:3-09 LINES AS ARCHITECTURAL THINKING

205

-

7/28/2019 Frascari - 2009 - Lines as Architectural Thinking

8/14

cosmopoietic spheres of architectural fac- turesdrawings or buildingsaspects thatbelong to other cosmopoietic spheres thatoften remained unknown. Cosmopoiesis as anact of world-making always starts from worldsalready in existence where every making is aremaking.8 Therefore, architecture becomes anelegantly conceived conjectural manifestationof elegant translations and collations construct-ing places or structures ordered by speciccultural tracing of lines.

The mystery of architecture is all in thedivinatory nature of the mirroring nature of the world of drawing and the world of building.The conjuring up of buildings is governed by adouble mode of translation: back-telling trans-lations that are transformations of the lines of building in the lines of drawing, and foretelling translations that are translations of the lines of drawings in the lines of buildings. Theseexercises of back-telling and foretelling form aspeculative chiasm, a hypogeal structure, on

which every project of architecture must beerected. Posing architecture as a graphic tradewith an intellectual tradition that transformsbuildings in drawings and drawings in buildings,and recognizing that adequate or inadequatearchitectural outcomes result from faithful or unfaithful and traitorous or traditional trans-lations, is to recognize that architecture is aconversion that makes visible the invisiblearendition of the imaginable into the real.Architecture is then a cosmospoietic repre-sentation that trades between the idioskosmos (the combination of individual reality and private dreams) and the koinos kosmos(ashared reality coalescing in dreams that all of us share). This joining of individualand sharedrealities restricts and modies assessments,and results in a denial of the line separatingpast, present and future, since architectural translation is an elegant event, taking place

within the multiple interacting temporalspheres of cosmopoiesis.

To draw before building is to recognizearchitects as agents of change because thelines of their drawings make them aware of aspects of time, life and above all the unknownothers since buildings are conceived not only for the direct immediate users, but also for users that cannot even be predicted or estimated. The immediate approach to con-struction misses altogether or makes it im-

possible to achieve unspecied aspects of human change. Architecture expressed by drafted lines liberates the human beings from the total conditioning produced by codiedcultural, structural and functional resolutions.Architectural translation operates according to tradition and usage rather than rules andanalysis. Drawings are based on different modesof thinking converted in lines and the primordialelement discoverable at the source of theelegant conversions of architecture is a relation-

ship of causality. The drawings developed for the construction of a building are translations by which a drafting facture becomes a buildingfacture. In essence, a different use of materialreality, an elegant architectural translation,denes and demonstrates the marginal by bringing in focus the tensions between ortho-doxy and heterodoxy, centrality and diversity; assuch, it represent otherness in society.

LineamentaPeople built rst and drew afterward.JoelSakarovitch, Epures darchitecture: De lacoupe des pierres a la geometrie descriptive XVIXIX siecles, Basel: Birkhauser, 1998.

In Ersilia, to establish the relationships that sustain the city s life, the inhabitants stretchstrings from the corners of the houses,white or black or gray or black-and-white

FRASCARI

206

-

7/28/2019 Frascari - 2009 - Lines as Architectural Thinking

9/14

according to whether they mark a relation-ship of blood, of trade, authority, agency.Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities, New York:Houghton Mifin Harcourt, 1978.

To solve the genetic vagueness embedded in the concepts of architectural lines, an oppor- tunity lies in a review of the Latin wordlineamenta as used by Leon Battista Alberti inhis De re aedicatoria (c.1450). He also uses it to title the rst book of the treatise. Performinga back-telling on this Albertian lineamenta can

be a way of untangling the skein of lines playedon the drafting tables by architects and givingback to those drafted lines of thought a sapidnature again. Several authors have insisted thatAlbertis meaning for such a distinctive term aslineamenta corresponds to something lessbroad and, at the same time, more specic than the Italian disegno. Nevertheless, in the traditional Cosimo Bartolis Italian translation,printed in Florence in 1550, lineamenta was translated disegno.9 In the rst English edition of

De re aedicatoria, published in 1726, the translation prepared by the Venetian architect James (Giacomo) Leoni was not from Albertisoriginal Latin, but from Bartolis Italian version.Consequently, in English lineamenta becamedesign although John Dee in hisThe Mathe-maticall Praeface to the Elements of Geometrie of Euclid of Megara(1570) referring to Albertis theoretical duality had translated lineamenta aslineamentes.

The whole Feate of Architecture inbuildyng, consisteth in Lineamentes, andin Framyng. And the whole power andskill of Lineamentes, tendeth to this: that the right and absolute way may be had, of Coaptyng and ioyning Lines and angles:by which, the face of the buildyng or frame, may be comprehended andconcluded. And it is the property of

Lineamentes, to prescribe vnto buil-dynges, and euery part of them, an aptplace, & certaine nuber: a worthy maner,and a semely order: that, so, ye wholeforme and gure of the buildyng, may rest in the very Lineamentes. &c. And wemay prescribe in mynde and imagination the whole formes, all material stuffebeyng secluded. Which point we shallatteyne, by Notyng and forepointyng theangles, and lines, by a sure and certainedirection and connexion. Seyng then,

these thinges, are thus:Lineamente, shalbe the certaine andconstant prescribyng, conceiued inmynde: made in lines and angles: andnished with a learned minde and wyt. 10

Published in 1553, the rst French translationby Jan Martin usedlineamens (lineaments). 11 Ina modern Italian translation, in a translatorsfootnote, Giovanni Orlandi says that in thebeginning of his translation, he wanted to use

the word progetto12

and not the word disegno.However, having noticed that in later chaptersAlberti himself makes a restrictive use of the term lineamenta, Orlandi decided to keep the traditional translation in disegno.13 In a recentEnglish translation, the glossary indicates that there have been too many interpretations and the translators explanation for using linea-ments is based on the physiognomic nature of Albertis understanding of architecturalbodies. 14

None of the above explanations is satisfactory.The use of the word lineaments is proper by similarity, but does reveal the genetic sapienceembodied in it by Alberti. My suggestion is touse the locution denoting lines to translatelineamenta since Albertis attention to line-amenta (denoting lines) is the recognition of a building practice leaning more towards

ATR 14:3-09 LINES AS ARCHITECTURAL THINKING

207

-

7/28/2019 Frascari - 2009 - Lines as Architectural Thinking

10/14

-

7/28/2019 Frascari - 2009 - Lines as Architectural Thinking

11/14

etymologies for templum.17 For Cipriano, tem-plum derives from root temp- that expresses notonly the notion of tension but also that of crossing that is tensioning an element transver-sely to another. 18 The templum has three parts:one in the sky, one on the ground and oneunderground. Tensioning lines for determiningangles and transversal crossings of ax linesdelineated the temple on the ground pulled by the augurs. The ceremony and function of theaugur was central to any major undertaking inRoman societypublic or privateincluding

matters of war, commerce, and religion andbuildingfrom this comes the tradition of inaugurating buildings and edices.

The procedure of line tracing for augursinvisible temple is at the base of the inaugura- tion of the construction site and as well as of the inauguration of architectural drafting sur-faces. An aftermath illustration of Albertis treatise (he did not want any image associatedwith his text) shows a direct connection to

templum layout. The image refers to thepassage where Alberti discusses the layingout of the area of foundations (Book 32),which is done by lines that Alberti callsoriginating lines (radices).

From midpoint of the front of thestructure pull a line to the back of it, half way along it we drive a picket into theground and through it, following ageometric construction we draw a trans-versal line. We then related everything tobe measured to these to lines.

The two taut crossing lines for working on thearea of a future building corresponds to the two crossing lines traced by the augurs where the positive and negative connotations of theomens and consequent auspices were mea-sured in relation to these lines. The geometric

construction suggested by Alberti correspondsalso to the traditional cunning preparation of asheet of paper for drawing on it, since edgeswere not necessarily perfectly parallel or orthogonal in handmade paper, the draftingarea was ruled by two orthogonal linescrossing in the centre of the paper.

The proposed phenomenological origin of thedenoting lines can also help to explain a remark by Alberti that has puzzled many critics.

They are of such a nature that we mightrecognize the same lineament in severaldifferent buildings that share one and thesame form 19

If lineamenta is translated as design, theinterpretation is that different buildings share the same design, but if the translation isdenoting lines, the meaning is that differentbuildings share the similar layout procedures.

The transformation of the use of taut lines onsite to the use of denoting lines traced on paper,and vice versa, reveals the wit or cunningintelligence of architects in their divination of future buildings. In the rst paragraph of the rstchapter of the rst book of his architecturalprimer, Vitruvius suggests that construction is ameditated process of building by advancing theidea that theory is a graphic illustration devised to explain cunningly constructed objects. Sollertia, the act of cunning judgment, is an essentialintellectual procedure to build thoughts and any construction. Sollertiais the fundamental virtuewith which architects infuse their factures. They are prudent and ingenious architects who knowhow to meditate architecture critically by constructing plots and weaving plans. Sollertia/ metis has its origin in the art or technology of weaving since all the lines used in other craftsrequiring metis derive from the lines used in

ATR 14:3-09 LINES AS ARCHITECTURAL THINKING

209

-

7/28/2019 Frascari - 2009 - Lines as Architectural Thinking

12/14

-

7/28/2019 Frascari - 2009 - Lines as Architectural Thinking

13/14

that which is invisible. Through a peculiar andcurious procedure of de-composition, selec- tion and re-composition, through a polysemicuse of lines, architects can trace rooms,structures and building details whose functionsbecome self-evident in the composition of thelines that will never actually be seen in theconstructed building. However, it is essentialfor presenting the inner and outer spacessimultaneously and revealing the many tem-poral sequences of architectural perception.The building is represented in its entirety but

there is no necessary likeness between thelines and the original.

The lines of building are neither facsimiles nor symbols; they make architecture poetical. It iswithin this cosmopoiesis that the enigmaticbeauty of the lines lies. Lines guide theenigmatic conceiving of architecture, both onsite and on paper. By using a sequence of lines,architects make present that which is absent.This conceiving practice is based on processes

of demonstration. Demonstrations occur bothin the constructing of theoretical drawings andin the constructing of building drawings; sinceboth are forms of realization of architectural thinking, every architectural demonstrationbecomes ontological.

Architects demonstrate through tangible signs the intangible that operates in the tangible of aconstruction. This demonstration is the settingof the problem of the labour involved inarchitecture. The physical pulling of lines onsite, a projection using the compass of thehuman body, reveals a continuous search for the human measure necessary for bridging thepast and future of the constructed world. Anarchitectural play of lines on a mobile supportis not the designing of a specic building, butrather a projection of a future constructedworld based on the transformation of the past

world of construction through a specicdrawing, the ichnography.

These coincidences of events and storiesillustrate the corporeal basis of the linesprojected on plans and in addition suggest their curricular nature. The experience of lines of lifeis made tangible by the marks human livingleaves. In conceiving architecture through draw-ing, the human body resonates to the mind by merging ows of inner and outer perspectives.The amalgamation of senses and architecture

takes place within body experience, which can then come to life through drawing factures. As aphenomenon, this process can be carefully observed and noted and reinterpreted toprovide insight into drawing knowledge and the nature of architectural understanding. All of the senses are implicated in drawing factures.The making and reading of drawings affect us by manipulating the ratio of our senses: hasteningslowly, architects see the drawing, smell thedrawing, hear the drawing, touch the drawing

and taste the drawing. The drawings are biasedaccording to time and space, they come fromdeep inside, from the common sensorium andmaterialize on a surface through the interactionof hands, tools and surfaces since architecture isabove all the architect, but it is also other than the architect.

Marco Polo describes a bridge, stone by stone.But which is the stone that support thebridge? Kublai Khan asks. The bridge is not supported by one stone or another, Marcoanswers, but by the line of the arch that they form. Kublai Khan remains silent, reecting.Eventually, the Great Khan adds: Why do youspeak to me of the stones? It is only the archthat matters to me! To which Polo retorts:Without stones there is no arch. Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities, New York:Houghton Mifin Harcourt, 1978.

ATR 14:3-09 LINES AS ARCHITECTURAL THINKING

211

-

7/28/2019 Frascari - 2009 - Lines as Architectural Thinking

14/14

Notes

1. Unfortunately, sapere andsapore are not anymore cog-nates in imaginative thinking.Virgil of Toulouse, grammarianof the 6th century, has beauti-fully shown the connection be- tween sapere and sapore. Virgilof Toulouse, Virgilio Marone grammatico: Epitomi ed Epistole,ed. and trans. G. Polara, Naples:Liguori Editore, 1979.

2. Robin Evans, The ProjectiveCast: Architecture and Its Three

Geometries, Cambridge, MA:MIT Press, 1995.

3. Scientintically, adv. A burl-esque nonce-word, formed by a blending of scientically and tint. 1761 STERNE Tr.Shandy III. v, He must havereddend, pictorically and scien- tintically speaking, six whole tintsand a half . . . above his naturalcolour.

4. Johanna Drucker, DigitalOntologies: The Ideality of Formin/and Code StorageorCanGraphesis Challenge Mathesis?,Leonardo, 34, 2 (April 2001):141145.

5. David Summers, Real Spaces:World Art History and the Rise of

Western Modernism, London:Phaidon, 2003.

6. Ernesto De Martino, Sud emagia, Milan: Feltrinelli, 2004.

7. Giuseppe Mazzotta, Cosmo-poiesis: The Renaissance Experi-ment, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001.

8. Nelson Goodman, Waysof Worldmaking , Indianapolis:Hackett Publishing, 1978.

9. Leon Battista Alberti, Larchi-tettura di Leonbatista Alberti tra-dotta in lingua orentina daCosimo Bartoli gentilhuomo &accademico orentino. Con laaggiunta de disegni. In Firenze:appresso Lorenzo Torrentinoimpressor ducale, 1550.

10. John Dee, The Mathemati-call Praeface to the Elements of Geometrie of Euclid of Megara(1570) , New York: Science His- tory Publications,1975, p. d.iiij.

11. Leon Battista Alberti, LAr-chitecture et Art de bien bastir duSeigneur Leon Baptiste Albert,Gentilhomme Florentin, divisee endix livres, Traduicts de Latin enFrancois, par deffunct Jan Martin,

Parisien, nagueres Secretaire duReverendissime Cardinal de Le-noncourt, A Paris: [Imprime par R. Massellin, pour]J. Kerver, 1553.

12. In architectural terminology the Italian term progetto cannotbe translated as design, since ithas broader and idiosyncraticphenomenological connotations.

13. Leon Battista Alberti, Lar-chitettura, (De re aedicatoria), trans. Giovanni Orlandi, vol. 2,

Milan: Edizioni Il Polilo, 1966.

14. Leon Battista Alberti, On the Art of Building in Ten Books, trans. Joseph Rykwert, Neil Leach andRobert Tavernor, Cambridge,MA: MIT Press, 1988.

15. Alberti, On the Art of Building ,p. 7

16. The Book of Ezekiel (from the Hebrew Bible) 40:3.

17. Palmira Cipriano, Templum,Rome: University La Sapienza,1983, pp. 121142.

18. Cipriano, Templum, p. 123.

19. Alberti, On the Art of Build-ing , p. 219.

FRASCARI

212