Framework for Ee

-

Upload

ulises-iri -

Category

Documents

-

view

219 -

download

0

Transcript of Framework for Ee

-

8/12/2019 Framework for Ee

1/13

Applied Environmental Education and Communication, 6:205216, 2007Copyright Taylor & Francis Group, LLCISSN: 1533-015X print / 1533-0389 onlineDOI: 10.1080/15330150801944416

A Framework for Environmental EducationStrategies

Martha C. Monroe, School of Forest Resources and Conservation,University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA

Elaine Andrews, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin, USAKelly Biedenweg, School of Forest Resources and Conservation,University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA

Environmental education (EE) includes a broad range of teaching methods,topics, audiences, and educators. EE professionals have worked over the last 30

years to provide distinct definitions, guides, objectives, and standards that will helpeducators know how to differentiate environmental education from othereducational efforts and how to deliver it effectively. This article incorporates severalrecent frameworks of educational strategies into one that has usefulness to formaland nonformal educators as well as communicators. Our purpose is not to redefineEE, but to provide a framework that can help practitioners consider a suite of

possible purposes and interventions that can belong under the umbrella of EE. Wedefine four categories of EE according to their purpose: Convey Information, BuildUnderstanding, Improve Skills, and Enable Sustainable Actions.

Environmental education (EE) is an approach,a philosophy, a tool, and a profession. As a dis-cipline, it is applied in many ways for manypurposes. This article organizes a variety ofEE strategies into a model according to the

educators purpose. We recognize there aremany different ways to categorize these strate-gies and believe this version has value for prac-titioners in both education and communicatiofields.

In its most basic form, EE implies learningabout the environment. Lucas (1972) suggested

Address correspondence toMartha C.

Monroe, SFRC, University of Florida, P.O. Box

110410, Gainesville, FL 32611-0410, USA.E-mail: [email protected]

that EE is education in, about, and for the en-vironment. This simple description reinforcesthe different purposes that EE often serves: pro-grams provide opportunities to explore naturein the outdoors, information about conserva-

tion and environmental issues, and opportuni-ties to gain knowledge and skills that can beused to defend, protect, conserve, or restore theenvironment.

This multidimensional definition was con-firmed by the delegates at the Tbilisi Inter-governmental Conference in Georgia, USSR in1977 (UNESCO, 1980) in their three goals forEE:

To foster clear awareness of, and con-cern about, economic, social, political, and

-

8/12/2019 Framework for Ee

2/13

206 M. C. MONROE ET AL.

ecological interdependence in urban and ru-ral areas;

To provide every person with opportunitiesto acquire the knowledge, values, attitudes,

commitment, and skills needed to protectand improve the environment;

To create new patterns of behavior of individ-uals, groups, and society as a whole towardthe environment.

The delegates provided additional informationabout the role of environmental education increating these new patterns of behavior: En-

vironmental education must look outward to

the community. It should involve the individ-ual in an active problem-solving process withinthe context of specific realities, and it shouldencourage initiative, a sense of responsibilityand commitment to build a better tomorrow(UNESCO, 1980, 12).

By focusing on the essential concepts ofenvironmental awareness,knowledge,attitudes,skills, and participation, the Tbilisi frameworkhas been useful to both formal and nonfor-mal environmental educators and trainers for

designing a host of different resources, suchas Hungerford et al. (1980) curriculum frame-

work and NAAEEs Guidelines for Excellence(NAAEE, 2000). These EE sources guide educa-tors to create opportunities for learners to gainknowledge; explore values; develop skills suchas questioning, analysis, issue investigation, andproblem solving; and develop personal respon-sibility or ownership for becoming responsibleenvironmental citizens.

The multi-purpose aspect of EE can beperplexing for practitioners wishing to differen-tiate environmental education from other edu-cational efforts. Its encompassing definition en-ables a variety of programs and opportunities tofall under the banner of EE, while it risks lim-iting high quality EE programs to those whichaccommodate all aspects. Meanwhile, educatorstend to gravitate toward those aspects of the def-inition that are more familiar or better defined.

Interestingly, some natural resource profes-

sionals might develop materials and programsthat conform to all the aspects of the Tbilisi def-

inition, yet not believe they conduct EE or areenvironmental educators. These professionalsmight have titles such as information special-ist, outreach coordinator, communications spe-

cialist, community organizer, public relationsspecialist, facilitator, trainer, or business consul-tant. Particularly difficult to distinguish is thedifference between the two fields that most pre-dominantly engage in EE: Education and Com-munication. Educators often maintain a defini-tional divide by regarding education as a pro-cess that has extensive contact with learners, be-havioral objectives,and unbiased or bias-neutralinformation that does not seek to change be-

havior, but prepares learners to make decisions.In contrast, communication activities that advo-cate a particular behavior, such as with mass me-dia, persuasion, and social marketing, are con-sidered a different discipline. The confusion ap-pears to lie in differentiating between the pur-

poseof the initiative and the strategiesused toachieve the objectives. Applying critical think-ing skills, for example, may be seen as an ed-ucation objective, but could be practiced withobviously biased information; a social market-

ing campaign is seen as a communication effortto create new patterns of behavior, but oftenserves to provide information that people wantto help them make a change they have chosen.

Environmental education is not only mul-tifaceted, it is also continually evolving. Morerecent approaches seek to focus on the so-cial dimension of environmental challenges,to more actively address behavior change, andto facilitate rather than lead learning. Mappin

and Johnson (2005) trace the evolution of theperceived purpose, place, and practice of en-vironmental education from a focus on natu-ral science and conservation to a more socialand political perspective. Authors writing fortheirbook,Environmental Education and Advocacy(Johnson & Mappin, 2005), consider ques-tions about the link between training, educa-tion, and problem solving; what environmen-tally responsible behavior is and who decides;and the challenge of expressing personal val-

ues while teaching the importance of evaluatingdifferent perspectives (Disinger, 2005; Jickling,

-

8/12/2019 Framework for Ee

3/13

A FRAMEWORK FOR ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION STRATEGIES 207

2005; McClaren & Hammond, 2005; Simmons,2005).

Other evidence of change evolves from anincreased interest in environmentally responsi-

ble behavior. Educators and researchers havefocused on the psychological and sociologicalfoundations of behavior. Behavior change theo-ries appear to fall into two avenues for encour-aging conservation behaviors (Monroe, 2003).The avenue most akin to education (e.g., build-ing knowledge and skills) results in increasedenvironmental literacy, which can be demon-strated through environmentally appropriatedecisions. The other avenue applies communi-

cation strategies such as social marketing con-cepts to lead more predictably to specific behav-ior change.

With growing awareness of the complexityof current environmental crises, we find that theboundaries between education and communi-cation are blurred and strategies from multiplefields are called on to improve public involve-ment and solve complex problems. New andold terms encompass slightly different mean-ings and suggest alternative ways of designing

environmental education programs: adaptivemanagement, civil society, collaborative learn-ing, public deliberation, environmental justice,social capital, service learning, sustainable de-

velopment, education for sustainability, envi-ronmental citizenship, stewardship education,environmental literacy, and public engagementare but a few that intersect with the work of edu-cating about and for the environment. Environ-mental education methods can form the foun-

dation for addressing each of these concepts.

FRAMING THE WORK OFENVIRONMENTALEDUCATION

In this context, the basic categories of educationand communication are not sufficient to differ-

entiate programs or practitioners, or encompasseverything that is EE. Fortunately, two recent

frameworks rely on four categories to clarify anddistinguish EE interventions.

Following an evaluation of World-wideFund for Nature (WWF) educational programs,

Fien and others (2001, 2002) developed aframework of four nested categories to de-scribe WWFs diverse projects: information,com-munication, education, and capacity building(seeTable 1). They propose using objectives, pro-cesses, audience settings, and tools to illustratethe application of each type of social strat-egy of conservation (Fien et al., 2001, 389).Informationactivities generally aim to increaseawareness and understanding and are defined

as informal education. Communicationactivi-ties aim to establish a dialogue between audi-ences and WWF in order to share experiences,priorities, and planning, and are delivered ininformal and nonformal settings.Educationac-tivities aim to promote knowledge, understand-ing, an attitude of concern, and motivation andcapacity to work with others in achieving goals,and are delivered in formal and nonformal set-tings.Capacity buildingaims to increase the ca-pacity of civil society to support and work for

conservation and is delivered primarily in non-formal settings.

By differentiating among these four pur-poses for conservation programs, the authorssucceeded in demonstrating how various typesof outreach contribute to an overall EE ef-fort. Their framework encompasses activitiesas diverse as coloring books and brochures,semester-long service learning courses, TVprograms, community workshops, and grant-

writing seminars. One shortcoming of theframework, however, is that the categories aredefined by the audience. This poses artificiallimits on where formal education strategies canbe used, for example. Although this might bethe best way to structure the WWF conserva-tion programs, it may limit the way other institu-tions describe their programs. Nevertheless, thissummary generated lively discussion of whetherthese categories provide a useful framework forenvironmental educators.

Scott and Gough (2003) continued theconversation with a model that more actively

-

8/12/2019 Framework for Ee

4/13

208 M. C. MONROE ET AL.

Table 1A Continuum of Social Strategies for Conservation

Strategy Information Communication Education Capacity Building

Objective To increaseawareness and

understanding of

conservation

issues and the

work of WWF

To establish a dialoguebetween sectors of the

community and WWF in

order to:

Increase understanding

of the conservation

issues that are of most

concern, and

Share experiences and

priorities and plan

collaborative projects to

promote conservation.

To promote:

Knowledge and

understanding of

conservation principles,

an attitude of concern for

the environment, and

the motivation and

capacity to work

co-operatively with

others in achieving

conservation goals.

To increase the capacityof civil society to support

and work for

conservation through

training, policy

development, and

institutional

strengthening within

and outside WWF.

Processes Dissemination of

information in a

variety of media.

Facilitation of dialogue

or two-way

communication both

within WWF and

between WWF and

outside groups.

Facilitation of learning

experiences through the

use of information,

communication, and

pedagogical processes

that develop individual

and group motivation

and skills for living

sustainably.

Development and

enhancement of policy

and institutional

structures and skills.

Training of WWF staff

and key stakeholders in

society.

Audience

Settings

Generally informal

education

Generally informal and

non-formal settings

Generally formal and

non-formal settings

Generally non-formal

settings

Tools Public relations

and advertising.

Information

campaigns via a

variety of

in-person, paper,

audio-visual, and

electronic media.

Information campaigns

with feedback processesto establish dialogue

between WWF and

groups

Environmental

interpretation.

Participatory social

marketing.

Formal education from

preschool to university.

Vocational and

professional education

courses.

Non-formal education

through youth, religious,

farmer, and business

associations.

Participatory social

marketing.

Professional

development andtraining.

Community

development via

Participatory Learning

and Action (PLA/PRA)

approaches.

Organizational

development.

Policy review and

development.

Strategic planning.

Network development.

Examples Book publishing.

Public service

announcements.

TV programs.

Posters.

Stickers.

Public displays

and/or exhibitions.

Newsletters to members.

Town meetings.

Telephone/mail call back

associated with an

information campaign.

Interactive exhibitions.

Integrated curriculum

and professional

development project.

Local schoolcommunity

water action project.

TV programs integrated

with related community

workshops.

Participatory Learning

and Action (PLA)

projects.

Public involvement in

Local Agenda 21

planning.

Workplace training for

ISO 14001 accreditation.

-

8/12/2019 Framework for Ee

5/13

A FRAMEWORK FOR ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION STRATEGIES 209

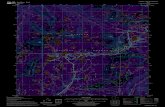

Fig. 1. Information, communication, mediation: Contributions to capacity building.

acknowledges the dynamic of society and com-munity when describing outreach and educa-tion options (see Figure 1). In their frame-

work, the first three categoriesinformation,communication, and mediationrepresent var-ious strategies of training and education thatlead to learning. Application of these three cat-

egories varies based on the nature of the in-teraction between the learner and the educa-tor and whether significant facts and values aredisputed as opposed to the more static distinc-tions. This revision provides significant contri-butions by focusing on the importance of learn-ers and learning in defining the result of ed-ucation and training, and by acknowledgingthat all learning is embedded within socioeco-nomic contexts and can happen with or withoutplanned activities.

Scott and Goughs first category, informa-tion, is described as instruction with one-way

information flow and agreement on facts andvalues. The second category, communication, isdescribed as engagement of learners in a two-

way flow of information where there is agree-ment of facts and values. The third categoryis termed mediation, where educators facilitatelearning through a two-way exchange of infor-

mation that questions and explores disputedfacts, values, and other assumptions. All of thesestrategies and a few others (e.g., self-directedlearning, coaching, mentoring) contribute tocapacity building.

The Scott and Gough framework does notuse formal and nonformal education settings asdefining characteristics for interventions. Theirmodel emphasizes an active role for learnersand it assumes that mediated learning is the out-come of outreach, training, and formal and in-

formal education efforts. Categories are distin-guished by the level of audience participation:

-

8/12/2019 Framework for Ee

6/13

210 M. C. MONROE ET AL.

from providing information (information) toactively engaging the learners (communicationand mediation). This shift in focus facilitates amore universal application of the EE frame-

work, yet still may not fully encompass the exist-ing strategies of formal and nonformal EE andcommunication. Nonetheless, it succeeded inintroducing significant concepts for modern en-

vironmental education.

A NEW FRAMEWORK

Whether we are school teachers explainingthe water cycle, naturalists engaging citizens inoutdoor enjoyment, or agency representativesinstructing residents about compost bin con-struction, we have a challenging job. We mustclearly identify the problem or opportunity, as-sess needs, and choose an intervention that ad-dresses defined needs and is most likely to leadto the desired result. A framework can help pro-fessionals determine an appropriate goal, rec-

ognize strategies most effective for that goal,and evaluate why an intervention may or maynot have been effective. In addition to Scott andGoughs version that defines the processes by

which learners engage in understanding, we be-lieve EE practitioners will find helpful a frame-

work that describes the strategies they have avail-able to them to design EE programs.

We propose a modification of the Fien andothers (2001) and Scott and Gough (2003)frameworks that could be useful to a larger

variety of educators and communicators anddemonstrate how it can be applied. Our pur-pose is to summarize and organize a suite ofpossible interventions that can be used underaccepted definitions of environmental educa-tion. We define four categories of interventionsbased on their objectives:

Convey information Build understanding

Improve skills Enable Sustainable Actions

These categories are based on the educa-torspurpose for the educational initiative, thusa variety of practitioners can find them rele-

vant. For simplicity, we use the terms education,

educators, and learners in the broadest sense;thus, the term education includes formalizedlearning, nonformal education, training, out-reach, peer-to-peer, and free-choice learning.

We refer to educators as the people who designand deliver opportunities for and often in col-laboration with their target audience (Stevens& Andrews, 2006). They may work for natu-ral resource agencies, nongovernmental orga-nizations (NGOs), schools, or county extension

offices. Learners are the people who take ad-vantage of opportunities created by profession-als or who engage in their own learner-createdexperiences by accessing widely available infor-mation and opportunities available from multi-ple providers who are not necessarily workingtogether.

As in the original model (Fien et al., 2001),the new framework proposes nested categoriessuch that subsequent categories may includeprevious ones. In this framework, however,au-

dience participationis a variable that describes avariety of ways educators and learners might in-teract. The more an educator uses participatorystrategies in any one category, the more likelythat category is to morph into another (seeFigure 2).

The extent to which the educator consultswith, surveys, engages, and collaborates with theaudience will improve the educational meth-ods in every category and, if the educator ad-

dresses their needs, will increase the likelihoodof achieving the educators objectives. Althoughthis is easier to do in the categories that in-

volve two-way communication, we believe thatopportunities exist for educators to learn aboutand attend to learners needs even in one-waycommunication strategies. One category (en-able sustainable actions) may only be possibleby using participatory strategies, thus giving ahome to bottom-up learning.

The success of the strategies listed in these

categories also depends on the quality of inter-action. Skilled practitioners should be able to

-

8/12/2019 Framework for Ee

7/13

A FRAMEWORK FOR ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION STRATEGIES 211

Fig. 2. A framework for environmental education strategies.

inspire and motivate learners with techniquesfrom each category. In what follows, we providea description of each category to further define

what we mean. We provide sample techniquesfor each category in Table 2. We also providea brief case study to illustrate how practition-

ers might apply each category as they address aspecific situation.

Convey Information

As originally described, work in this categorypresents one-way transmission of informationin order to provide missing facts or data, to in-

crease access to how to do it instructions, or tobuild awareness about a specific topic. Byinfor-mationwe refer to factual, conceptual, or proce-dural knowledge (see Anderson & Krathwohl,2001). School teachers convey information us-ing lectures, textbooks, and videos; agenciesuse news articles, presentations, brochures,web-sites, and kiosks. Providing details that peo-ple want or information to clarify issues andincrease awareness is essential to environmen-tal education programs (for techniques, see

Jacobson, 1999). Emphasis on this category ismost appropriate when the facts are not dis-

puted, when the issue is urgent, or when peo-ple are simply missing information they request.

Although conveying information forms the coreof what many programs include, the nature ofone-way information flow often excludes par-ticipation, especially when the learners are not

involved in selecting content or distributionmechanisms (and therefore it is a relativelysmall shape in Figure 2). It can be improved,however, with elements of the next strategy.

Build Understanding

This is a two-way transmission of informationthat aims to engage audiences in developing

their own mental models to understand a con-cept, values, or attitudes. Understandingimpliesmultiple thinking skills such as remembering,recognizing,interpreting, summarizing, and ex-plaining (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001). Edu-cational strategies include guided nature walks,

workshops and charettes for adults, and in-quiry learning activities for youth. It also impliesuse of audience assessment and formative andsummative evaluation to better understand howthe learners perceive information. With the ad-

dition of such communication analysis proce-dures, the effectiveness of information sharing

-

8/12/2019 Framework for Ee

8/13

212 M. C. MONROE ET AL.

Table 2Formal and Nonformal Education Strategies Across the EE Framework

Some nonformal andSome formal learning free-choice learning

Category Purpose strategies strategies

Convey Information To disseminateinformation, raiseawareness, to inform

Textbook, lecture,video, film, andInternet resources

Information campaign,electronic media, Internetresource or website, poster,brochure, sign, PublicService Announcement,news article, exhibit

Build Understanding To exchange ideas andprovide dialogue, tobuild a sense of place,to clarify and enhancethe understanding ofinformation and

issues, and to generateconcern

Discussion, role play,simulation, casestudy, experiment,game, constructivistmethods,experiential learning,

field study

Workshop, presentation withdiscussion, charette,interactive website,simulation, case study,survey, focus group,interview, peer to peer

training, action research,issue investigation,environmental monitoring,guided tour, guided naturewalk

Improve Skills To build and practiceskills

Cooperative learning,issue investigation,inquiry learning,citizen scienceprograms, volunteerservice, some typesof project-basededucation

Coaching, mentoring,demonstrations, technicaltraining, environmentalmonitoring; providing achance to practice a specificskill or work on a task,persuasion and socialmarketing strategies thatmodify social norms,

including: modeling,commitment, incentives,and prompts to encourageskills building and behaviorchange

Enable Sustainable Actions To build transformativecapacity for leadership,creative problemsolving, monitoring

Inquiry-basededucation, sometypes of servicelearning,Environment as anIntegrating Concept,and otheropportunities forlearners to define

problems, designand select actionprojects, identifyfacts, and build skillsin problem solving

Adaptive collaborativemanagement, actionresearch, training fororganizationaleffectiveness, facilitatingpartnerships and networks,joint fact finding,mediation, alternativedispute resolution,

negotiated rulemaking,learning networks

is improved by allowing modification for thespecific needs of learners. Strategies in this cat-egory are helpful to uncover misconceptions innovel or complex issues. The audience may helpto identify the focus for the intervention and of-

fer feedback, but the process and objectives aremost often driven by the educator. (For tech-niques see Jacobson et al., 2006; for theoriessee Horton & Hutchinson, 1997 and Merriam& Caffarella, 1999).

-

8/12/2019 Framework for Ee

9/13

A FRAMEWORK FOR ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION STRATEGIES 213

Improve Skills

Some education and communication programsaim to do more than develop knowledge and

understanding. They seek to build skills thatenhance or change practice, performance, andbehavior.1 In this category, learners apply orimplement a skill, or organize and critique in-formation (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001). Likethe previous two categories, educators purpose-fully facilitate learning toward a particular goal.Unlike the previous two categories, the edu-cator may more actively incorporate theoriesof diffusion (Rogers, 1995), persuasion (Petty

& Priester, 1994), social marketing (McKenzie-Mohr & Smith, 1999), and behavior change(Ajzen, 1985) to improve the adoption of behav-iors. School programs can enable youth to prac-tice citizenship, critical thinking, and groupcommunication skills through activities such asservice learning and issue investigation (Ernst& Monroe, 2004). Employers can increase staffeffectiveness by providing hands-on training ofnew techniques and tools. Community- focusedinitiatives may provide instruction for a new ac-

tivity, such as planting a rain garden, or use so-cial marketing techniques to encourage adultsto adopt a behavior that has been identifiedas a priority by the affected community. In allcases, information is an essential core of the ef-fort. In all cases the ultimate outcome is notdisputed. The community and learners agreethat clean water, resource conservation, or effec-tive waste utilization are important goals; they

just need targeted assistance to practice the de-

sired behavior (McKenzie-Mohr & Smith, 1999;Booth, 1996; Reilly & Andrews, 2004). The ef-fectiveness of strategies in this category is en-hanced by using instructional materials createdthrough interactive communication betweenlearner and educator and by focusing effortson issues that are more relevant to the learner.

1Several education authorities identify practice andapplication as an essential component of effective learning(American Psychological Association Board of EducationalAffairs, 2003; Trowbridge & Bybee, 1986).

The greater the involvement of the audience indefining theseskillsand skill-building strategies,the more closely they resemble those in the nextcategory.

Enable Sustainable Actions

The purpose of educational strategies in thiscategory is to transform the learner, the issue,the educator, and perhaps the organizationthrough the process of critically addressingproblems. These processes allow the educator

and learner to work together to define bothgoals and/or methods of the intervention.Morethan activities that promote understanding orskill building, these strategies are building ca-pacity for effective citizenship in a complex

world. More than previous strategies that couldconceivably be limited to environmental infor-mation, these strategies tend to include eco-nomic and equity concerns. Grappling with dif-ferent dimensions of the same problem, andredefining the problem as a result, can help

bring about new solutions. When youth developa community service learning project and par-ticipate in the selection and design of their activ-ity, for example, they are likely to become moreefficacious, empowered, and committed as theyimprove their community (Andrews, 1996; Zintet al., 2002). When communities and managersacknowledge the limitations of their facts andseek new information, they are redefining andtransforming the issue and their understanding

of it. When agencies and NGOs work collabora-tively with audiences to understand stakeholderinterests and preferences, to determine whatstakeholders know, where the uncertainties lie,

what additional information will be useful, whatthey can monitor, and how to use the informa-tion revealed from monitoring, they are trans-forming themselves, their understanding of theissue, and their ability to work together. Of greatimportance in this category is the recognitionthat the educator is not directing the process.

The educator may facilitate and support, butthe outcome is a unique product of those who

-

8/12/2019 Framework for Ee

10/13

214 M. C. MONROE ET AL.

are involved. Agencies who wish to use interven-tions of this type must be willing to accept direc-tion from the stakeholders. Community-basedenvironmental education programs (Andrews

et al., 2002), collaborative learning (Daniels &Walker, 2001) and adaptive collaborative man-agement (Colfer, 2005) provide excellent mod-els of social learning2 that fit this category.

These community examples are often notconsidered part of the traditional environmen-tal education methods. We believe, however,that they should be. Environmental educatorshave much to contribute to those working

with conflict resolution, community-based ed-

ucation, collaborative learning, and adaptivemanagement. We can design programs thatincorporate processes for building trust, shar-ing information, seeking clarity, identifying in-dicators, working toward understanding, me-diating, and negotiating new outcomes. Suchinterventions require tools for providing in-formation, building understanding, and prac-ticing skills. Taken together, and used in thecontext of agencies and coordinators who ex-press an honest interest in seeking creative so-

lutions by empowering the stakeholder group,these strategies create opportunities for deliber-ation, transformation, empowerment, and long-term problem solving. Interventions of this typeclearly meet the goals of the Tbilisi recom-mendations as well as education for sustainabledevelopment.

AN EXAMPLE

Many agencies and extension educators are inthe business of public information and edu-

2Social learning platforms create strong interpersonalrelationships, a more universal definition of the task andobjectives, better and more management options to achievethese objectives, and broad support for these options. Theseopportunities enablepeople to learnfrom eachother. Sociallearning can be spontaneous but can also be encouragedin the interest of designing more sustainable interventions(Keen et al., 2005).

cation to change behavior around urgent is-sues, such as reducing the risk of wildland fire.

An educator can use strategies in all four ofthese categories to achieve a variety of goals.

When an urgent message needs to be commu-nicated to a large population, perhaps about anoutdoor burn ban or evacuation route, the ed-ucator at the fire department is providing in-formation through mass media channels (Con-

vey Information). When there is more timeto build understanding, an educator mightlead a workshop or develop a detailed pam-phlet; either could address homeowner con-cerns and help them understand how to reduce

their risk by creating defensible space (BuildUnderstanding). In most cases, making surethat the audience understands is not enough,and the educator will be interested in creat-ing a series of community workshops, programs,demonstration areas, and even a contest be-tween neighborhoods to make defensible spacefun and popular (Build Understanding) and en-able residents to practice skills such as chain sawmaintenance, identification of trees to trim andshrubs to plant, and screening crawlspace (Im-

prove Skills). If the community identifies thisproblem as a priority, the educator might beable to work with community leaders to iden-tify innovative solutions or to develop a wildfiremitigation portion of the county comprehen-sive plan that builds mitigation activity into fu-ture development, for example. The process ofcommunity leaders and agency educators work-ing together to redefine the problem and sug-gest novel solutions is the essence of Enable Sus-

tainable Actions.There is of course, great overlap amongthese four categories (see Fig. 2). Although itis easiest to explain the categories in order, aneducator could easily conduct programs in onlyone of these areas, or all of these areas. Strate-gies in categories Improve Skills and Enable Sus-tainable Actions probably always include aspectsof categories Convey Information and Build Un-derstanding. Not only are the categories nested(as opposed to hierarchical), they can be im-

plemented through multiple strategies in a va-riety of settings. We provide several examples of

-

8/12/2019 Framework for Ee

11/13

A FRAMEWORK FOR ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION STRATEGIES 215

methods for each category (Table 2), but it isimportant to remember that the categories aredefined by their purpose, not the intervention.In order for a strategy such as inquiry-based edu-

cation to engage learners in Enable SustainableActions, educators must facilitate genuinely par-ticipatory processes.

SUMMARY

Our purpose was to design a framework thatwould organize the many EE activities andstrategies commonly used in a variety of situa-tions. Such a framework can remind programdesigners of opportunities and at the same timeprovide guidance in designing appropriate eval-uation strategies. By linking the purpose to thestrategy, as this framework does, program devel-opers can better select interventions and evalu-ate success.

This new framework suggests that the cat-egories are nested and vary by purpose, giving

environmental educators and communicators acommon language by which to discuss and com-pare their work.

Key points that underlie our proposedmodel:

1. Education and communication have tradi-tionally differed by definition, but may notbe so separate in practice.

2. Formal and nonformal education are of-

ten unnecessarily segregated and use similarbut not identical methods to accomplish thesame goal.

3. EE is a complex and broad umbrella that in-corporates a variety of strategies and contentfrom natural science to social science andtop-down to bottom-up with little to great au-dience participation.

4. To help people function and engage in deci-sions in an uncertain world, EE must includecollaborative strategies of community educa-

tion, mediation, social learning, and adaptivemanagement.

5. The degree to which the educator buildslearners needs into the design of the inter-

vention affects the degree to which the edu-cational methods from any of the four cate-

gories achieve the desired goal.6. Our framework applies to communication,

education, formal and nonformal initiatives,and bases its categories on the general pur-pose of intervention.

The original model arose from an evalua-tion of one NGOs conservation activities and

was modified after additional work with otherNGOs. We are pleased to see a conservation ed-

ucation framework that easily applies and in-cludes environmental education; many strate-gies and purposes are similar. We suggest thatthe new modifications create a framework thatcan apply equally well to formal and nonfor-mal educators in schools and agencies, andincorporates the often disparate activities ofinformation, outreach, social marketing, socialchange, and education.

REFERENCES

American Psychological Association Board of Educa-tional Affairs. (2003). Learner-centered psychologicalprinciples: A framework for school redesign and re-form. Accessed from http://www.apa.org/publications/brochures.html on August 18, 2006.

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001).A taxonomy for

learning, teaching, and assessing. A revision of Blooms taxon-

omy of educational objectives. New York: Longman.Andrews, E. (1996). Give Water A Hand youth action cur-

riculum. Proceedings, US EPA Nonpoint Source Pollution Infor-mation/Education Programs National Conference. Northeast-ern Illinois Planning Commission, Chicago.

Andrews, E., Stevens, M., & Wise, G. (2002). A model ofcommunity-based environmental education. InT.Dietz &P. C. Stern (eds.), New tools for environmental protection: Edu-cation, information, and voluntary measures(chapter 10, pp.161182). National Research Council Division of Behav-ior and Social Sciences and Education: Committee on the

Committeeon theHumanDimensions of GlobalChange,Washington D.C.: National Academy Press.

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory ofplanned behavior. In J. Kuhl, & J. Beckman, (eds.),

-

8/12/2019 Framework for Ee

12/13

216 M. C. MONROE ET AL.

Action-control: From cognition to behavior(pp. 1139). Hei-delberg: Springer.

Booth, E. M. (1996). Starting with behaviorA participatoryprocess for selecting target behaviors in environmental programs.Washington, DC: GreenCOM, Academy for EducationalDevelopment.

Colfer, C. J. P. (2005). The complex forest. Communities, un-certainty, & adaptive collaborative management. Washington,D.C.: Resources for the Future.

Daniels, S. E., & Walker, G. B. (2001).Working through envi-ronmental conflict: The collaborative learning approach.West-port, CT: Praeger.

Disinger, J. F. (2005). The purpose of environmental edu-cation: Perspectives of teachers, governmental agencies,NGOs, professional societies, and advocacy groups. InE. A. Johnson, & M. J. Mappin (eds.), Environmental ed-ucation and advocacy(pp. 137157). Cambridge UK: Cam-

bridge University Press.Ernst, J., & Monroe, M. (2004). The effects of environment-

based education on students critical thinking skills anddisposition toward critical thinking.Environmental Educa-tion Research, 10(4), 507522.

Fien, J., Scott, W. A. H., & Tilbury, D. (2001). Education and

conservation: Lessons from an evaluation. Environmental

Education Research,7(4), 379395.Fien, J., Scott, W. A. H., & Tilbury, D. (2002). Exploring

principles of good practice: Learning froma meta-analysisof case studies on education within conservation acrossthe WWF network. Applied Environmental Education andCommunication,1(3), 153162.

Horton, R. L., & Hutchinson, S. (1997).Nurturing scientificliteracy among youth through experientially based curriculum

materials.Columbus: The Ohio State University, Collegeof Food, Agricultural and Environmental Studies, Centerfor 4-H Youth Development.

Hungerford, H. R., Peyton, R. B., & Wilke, R. (1980). Goals

for curriculum development in environmental educa-tion.Journal of Environmental Education,11(3), 4247.

Jacobson, S. K. (1999). Communication skills for conservationprofessionals. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Jacobson, S. K., McDuff, M. D., & Monroe, M. C. (2006).Conservation education and outreach techniques. Oxford, UK:Oxford University Press.

Jickling, B. (2005). Education and advocacy: A troubling re-lationship. In E. A. Johnson & M. J. Mappin (eds.), Envi-ronmentaleducation and advocacy(pp. 91113). Cambridge,UK: Cambridge University Press.

Johnson, E. A., & Mappin, M. J. (eds.). (2005).Environmentaleducation and advocacy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Uni-versity Press.

Keen, M., Brown, V. A., & Dyball, R. (2005). Social Learn-ing: A new approach to environmental management. InM. Keen, V. A. Brown, & R. Dyball (eds.), Social learningin environmental management: Towards a sustainable future.

(pp. 321). London, UK: Earthscan.

Lucas, A. M. (1972). Environment and environmental ed-ucation: Conceptual issues and curriculum implications.

PhD Dissertation, Ohio State University. ERIC DocumentED068371.

Mappin, M. J., & Johnson, E. A. (2005). Changing per-

spectives of ecology and education in environmentaleducation. In E. A. Johnson, & M. J. Mappin (eds.),Environmental education and advocacy (pp. 127). Cam-bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

McClaren, M., & Hammond, B. (2005). Integrating edu-cation and action in environmental education In E. A.Johnson & M. J. Mappin (eds.), Environmental educationand advocacy(pp. 267291). Cambridge, UK: CambridgeUniversity Press.

McKenzie-Mohr, D., & Smith, W. (1999).Fostering sustainablebehavior: An introduction to community-based social marketing.Gabriola Island, B.C.: New Society Publishers.

Merriam, S. B., & Caffarella, R. S. (1999). Learning inadulthood: A comprehensive guide(2nd ed.). San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass.Monroe, M. C. (2003).Two avenues forencouraging conser-

vation behaviors, Human Ecology Review, 10(2): 113125.North American Association for Environmental Education

(NAAEE). (2000). Excellence in environmental educationguidelines for learning (K12). Washington, D.C.

Petty, R. E., & Priester, J. R. (1994). Mass media attitudechange: Implications of the elaboration likelihood modelof persuasion. In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (eds.),Media ef-fects: Advances in theory and research(pp. 91122). Hillsdale,NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Reilly, K.,& Andrews, E. (2004). Besteducation practices(BEPs)for water outreach professionals: Defining BEPs, refining new

resources and recommending future actions. University of Wis-consin, Environmental Resources Center. Accessed fromhttp://wateroutreach.uwex.edu on August 22, 2006.

Rogers, E. M. (1995).Diffusion of innovations(4th ed.). NewYork: Free Press.

Scott, W., & Gough, S. (2003). Rethinking relationships

between education and capacitybuilding: Remodellingthe learning process.Applied Environmental Education and

Communication,2(4), 213219.Simmons, D. A. (2005). Developing guidelines for envi-

ronmental education in the United States: The nationalproject for excellence in environmental education. InE. A. Johnson & M. J. Mappin (eds.), Environmental edu-cation and advocacy(pp. 161183). Cambridge, UK: Cam-bridge University Press.

Stevens, M., & Andrews, E. (2006). Outreach that makesa difference! Target audiences for water educationA re-

search meta-analysis. Accessed February 2006 from http://wateroutreach.uwex.edu/beps/MAcoverTOC.cfm

Trowbridge, L. W., & Bybee, R. W. (1986). Becoming a sec-ondary school science teacher (4th ed.). Columbus, OH:Merrill.

UNESCO. (1980). Environmental education in the light of theTbilisi Conference.Paris: Unesco.

Zint, M., Kraemer, A., Northway, H., & Lim, M. (2002). Eval-

uation of the Chesapeake Bay Foundations conservationeducation programs. Conservation Biology, 16(3), 641649.

-

8/12/2019 Framework for Ee

13/13