FOODS OF WHITE-TAILED DEER IN THE UPPER - US … · FOODS OF WHITE-TAILED DEER IN THE UPPER ° ....

Transcript of FOODS OF WHITE-TAILED DEER IN THE UPPER - US … · FOODS OF WHITE-TAILED DEER IN THE UPPER ° ....

FOODS OF WHITE-TAILED DEER IN THE UPPER° .

GREAT LAKES REGION--A REVIEW

Lynn L. Rogers, Wildlife Biologist,North Central Forest Experiment Station, ,

St. Paul, Minnesota

Jack J. Mooty, Wildlife Biologist,Minnesota Department of Natural Resources

Grand Rapids, Minnesota

- and Deanna Dawson,i Wildlife Biologist,North .Central Forest Experiment Station,

" _ ' St. Paul, Minnesota

!...

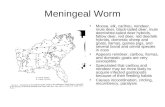

This report summarizes available information on the Research methods to obtain information on foodfood habits of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virgini- habits of deer in the UGLR have included analyzinganus) in the northern forests of Minnesota, Wisconsin, stomach contents, examining feeding sites, and ob-and Michigan (fig. 1). This area, referred to here as the serving tame deer on a leash. None of these methodsUpper Great Lakes Region (UGLR), is near the north- gives a complete picture of food habits, and each has aern edge ofthe white-tail's present range (Taylor 1956). different bias as will be discussed below. However,Deer were not abundant in the mature, pine-domi- each method gives an approximation of the diet.

nated, "virgin" forests of the UGLR. However, the Results of studies conducted in seven areas of theyoung hardWood forests created by large-scale logging UGLR during 1936-1976 are presented in tables 1-12and extensive forest fires allowed deer to expand their (Appendix). Differences in reported diets reflect localrange northward (Swift 1946, Stenlund 1958, Erickson differences in vegetation and differences in methodset al. 1961). Today, deer are important both aestheti- of study. Omitted from the tables are results of seven

cally and economically in the UGLR. They are viewed studies (Hammerstrom and Blake 1939, Swift 1946,and photographed as an important adjunct to the Dahlbergand Guettinger 1956,KreftingandHansenRe_on's tourist industry, and hunters spend over 200 1963, Orke 1966, McCaffery and Kohn 1971, andmilliondollars a year on deer hunting (USDI 1977). Hennings 1977) that did not permit percentageDeer are also the main prey of the timber wolf (Canis

•: . lupus) in the UGLR. This Region has the only sizablepopulation of wolves in the contiguous United States(Mech and Karns 1977).

The young forest that brought deer to the UGLR isnow reaching maturity, and deer populations are de-

' clining (Byelich 1965, Stone 1966, Mooty 1971, Mechand Kams 1977). State governments in this Region arenow spending nearly 2 million dollars a year on deer _H_o_habitat improvement. However, optimal habitat man-agement is difficult because the year-round food habitsof deer in the UGLR have not been documented thor-

oughly. Study of growing-season foodhabits was begun _ /.0n!y recently (Kohn and Mooty 197!, McCaifery et al. _,_.,_,_1974, Mooty 1976, Bauer 1977). This review empha- _ _.,,_,..sizes the need for further information and is a steptoward disseminating available information on deer Figure 1.--Northern forest area of the midwesternfood habits. United States.

.

breakdowns of diet or presentation by month. How- bunchberry, wintergreen, strawberry, and barrenever, common and scientific names of foods men- strawberry (McCaffery and Kohn 1971). As springtioned in those studies are included in Appendix II progresses, new green grass, emerging forbs, and newwhich lists reported-deer foods in the UGLR. leaves of trees and shrubs become available. Woody

twigs and evergreen forbs are forsaken, and new greengrowth forms over 90 percent of the diet (table 4 and 5)

SEASONAL FOODS OF DEER (Pierce 1975). This vegetation is both nutritious and

IN THE UPPER GREAT LAKES easilydigestible (Verme and Ullrey 1972). At thisREGION time, deer frequently feed in treeless areas such as old

fields, roadsides, and powerline rights-of-way which"green up" earlier than the surrounding forests

Foods ofdeercan be categorized into such groups as (McCaffery and Creed 1969).Woody browse, conifer needles, evergreen forbs, non- In late spring and early summer, deer, like mooseevergreen forbs, deciduous leaves, fruit, fungi, etc. (Alces alces), are sometimes observed eating aquaticUse of these groups by deer follows a seasonal trendthroughout the UGLR despite local differences in vegetation. Hennings (1977) observed deer in north-vegetatiom _ eastern Minnesota selectively eating (in decreasing

order of use) burreeds, filamentous algae, ribbonleafIn Winter, woody browse usually is the main food pondweed, water horsetail, arrowhead, sedges,

available, and it forms the bulk of the diet (tables t-4, marsh cinquefoil, white pond lily, yellow pond lily,11-12). This-food is low in nutrient quality andpurple watershield, and St. John's-Tort. Water mil-

digestibility, and.deer lose weight on it even when it foil and wild rice also have been reported as deeris available in unlimited quantities (Ullrey et al. foods in the UGLR (Dahlberg and Guettinger 1956,1964, 1967, 1968, Verme and Ullrey 1972, Grigal et Irwin 1974). Aquatic vegetation is fairly nutritiousal. 1979). Aprolonged diet of woody browse causes (Linnet al. 1973) and may be important in supplyingmalnutrition and starvation (Mautz 1978), both of annual requirements of sodium and other nutrientswhich are common in the UGLR in late winter

(Botkin et al. 1973, Jordan et al. 1974, Hanson and(Bartlett 1938, Erickson et al. 1961, Stenlund 1970

Jones 1977). Aquatic feeding reaches its peak duringKarns 1980).periods of reduced water levels in early summer

Although cedar is a preferred winter food (Dahl- (Townsend and Smith 1933, Behrend 1966, Skinnerberg and Guettinger 1956), needles of balsam fir, and Telfer 1974, Hennings 1977). The portion of thespruce, and pine apparently make an even poorer diet diet that aquatic vegetation comprises during peri-than most woody browse species. These needles corn- ods of peak use is unknown but is probably lowprised 58 to 60 percent of the rumen contents of

(Hennings 1977, Joyal and Scherrer 1978).starved deer autopsied in late winter during popula- In summer, deer eat the leaves of nonevergreention highs of past decades (Aldous and Smith 1938, terrestrial plants, mushrooms, and fruit (Kohn andDahlberg and Guettinger 1956). However, theseneedles made up only a small portion of the winter Mooty 1971, McCaffery et al. 1974). Aspen forests,diet of healthier deer studied more recently (tables 1- especially poorly stocked stands or those under 25

years of age, are important summer habitats (McCaf-3). Among the 'latter deer, the greatest use of balsam fery and Creed 1969, Mooty 1971, McCaffery 1976,

_ fir, pine, and spruce needles was by deer that eventu- Bauer 1977, Gullion 1977). Leaves from aspen suck-ally were killed by wolves. Sixteen percent of the

'stomach contents of 32 wolf-killed deer were needles ers less than one year old are a preferred foodof these species (Wetzel 1972). (McCaffery 1976). In northern Wisconsin, where

After the rigors of a northern winter and a nutri- first-year aspen suckers are abundant due to fre-' tionaliy marginal diet, fat reserves are depleted and quent clear-cutting of aspen forests, aspen leavesdeer become nutritionally stressed (Verme 1969, form a larger portion of the summer diet than does

any other item (McCaffery et al. 1974). Leaves fromMautz 1978, Karns 1980). In early spring, metabolic older aspen are less preferred, however 1. Conse-rates increase, does are in the last months of preg- quently, in northern Minnesota where aspen clear-nancy, and a high quality diet is essential to bothsurvival and reproductive success (Julander and cutting is less frequent aspen leaves form a smaller

part of the summer diet (Kohn 1970, Pierce 1975).Robinette 1950, L0nghurst et hi. 1952, Verme 1963, Leaves other than those of aspen also are important1969, Silver et al. 1969). As snow melts on south-facingslopes and-around the bases of trees in the uplands,deer begin supplementing their browse diets withleaves of small plants that remain green/overwinter: 1personal communication with L. Verme, 1980.

.

2

foodsinaspenstands.VegetationstudiesinMinne- varyingwithspecies,subspecies,phenology,andsitesota(Ohmann and Ream 1971),Wisconsin(McCaf- factors(Nagyand Regelin1977).The palatabilityoffery 1976),and Michigan(Bauer1977)showedthat plantsdecreasesasconcentrationsofcertainsecond-principalsummer deer foodssuchas maple,birch, arycompoundsincrease(Nagy and Regelin1977).willow,juneberry,hazel,cherry,honeysuckle,bush- A diversedietmay alsobenefitdeerin anotherhoneysuckle,rose,large-leafaster,and strawberry way.Eatingcertainplantsmay aidinthedigestionofareprevalentin aspenstands, others.For example,some plantsare toolow inIn thefall,nonevergreenleavesbecome increas- nitrogen,phosphorus,magnesium,orsulfurforade-

inglyscarcewith the exceptionoflarge-leafaster quaterumen digestion,but theseplantsmay bewhichpersistsinfrost-shelteredstandsintolatefall. utilizediftheyarecombinedwithothersthatprovideWhen nonevergreenleavesand othersummer foods the deficientelements(Church1977:138,Hansonbecome scarce,deer turn to grasses,sedges,and and Jones1977:254,256).evergreenforbsuntilthesebecomecoveredby snow(tables10and 11).Then deeronceagainbegineatingdormant woody browsewhich dominatesthe dietuntilthesnow meltsandtheabovecycleisrepeated.The seasonalfeedingpatternindicatesthatdeer PROBLEMS OF DEER IN

generallypreferyoungnonevergreenleavesbu_twill NORTHERN FORESTEDeat(in_decreasingorderofpreference)maturenon- VERSUS SOUTHERNevergreenleaves,evergreenforbs,cedarleaves,de- AGRICULTURAL DEER

ciduotmwoodybrowse,andconiferneedles.Preferred RANGES IN THE

foodsalsomay includearborealfruticoselichens, GREAT LAKES REGIONacorns,fruit,and certainfungiaccordingtostudiesconductedin otherregions(Cushwa etal.1970,Harl0w and Hooper 1972,Skinnerand Telfer1974,Crawfordetal.1975).AdditionalstudyisneededtoassesstheimportanceofthesefoodsintheUGLR.Diversityapparentlyisimportantinthedeerdiet

(Verme and Ullrey1972).Dahlbergand Guettinger Deeratthenorthernedgeoftheirrangearelimited(1956)foundthatcaptivewinteringdeermaintained innumber mainlyby problemsofoverwintermortal-weightbetteron a varietyofsecond-choicewoody ityand nutrition-relatedreproductivefailures.browsespeciesthan theydidon a dietofstraight Theseproblemsareeasedby improvementsinthecedar,afirst-choicewinterfood.MiguelleandJordan quantityand qualityofyear-roundfoodsupplysuch(1980)found thatcaptivemoose chosea diverse asoccurafterextensiveloggingand burning(Erick-summer dietevenwhen moutain-ash,a highlypre- sonetal.1961).However,problemsincreaseinyearsferred food, was made available ad libitum. Jordan when access to food patches is restricted by unusually(1967.) found deer preference for a species to be deep or long-lasting snow (Moen 1976, 1978, Nelson

highest where that species was scarcest, and Mech 1980). Deer on the George Reserve in• ' Perhaps one of the reasons ruminants choose a southern Michigan seldom dig through more than 3

diversediet isto av0idingestingtoomuchofanyoneof inches (7.5 cm) of snow to reach food (Coblentz 1970)

the many plant compounds that inhibit digestion and deer in northcentral Minnesota have not been(Nagy et al. 1964, Longhurst et al. 1968, Levin 1976). observed to dig through more than 12 inches (30 cm)Deer have long been known to select the most nutri- of snow (Mooty and Rogers, personal observations).tious forage available (Swift 1948, Weir and Torell Travel becomes difficult when deer sink beyond their!959), and it now is apparent deer also detect and chests (about 20 inches (50 cm)) (Formozov 1946,avoid compounds that inhibit the action of rumen Edwards 1956, Gilbert et al. 1970). Snow in themicro-organisms (Nagy et al. 1964, Longhurst et al. northern forests of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michi-1968, Nagy and Regelin 1977). These secondary gan becomes more than 20 inches deep nearly everycompounds, as they are called, have little or no impact winter (Environmental Science Services Adminis-on rumen micro-organisms at low concentrations tration 1968), burying low-growing plants beyond(Nagy and Regelin 1977), but at higher concentra- reach and hampering travel to the extent that eventions, their inhibitory action accelerates (Nagy and woody browse becomes difficult to obtain in quantity.Tengerdy 1968). A wide variety of secondary corn- By comparison, snow in the southern portions ofpounds are foundin plants, with the amount and kind these States usually is not as deep or long-lasting.

°

StudiesinagriculturalareasinMinnesotashowed numbers declinedto some extentthroughoutthethatsnow-freepatchesenabledeertoeatnonwoody UGLR (Mech and Karns 1977),but more recently,

- foodslongerthanisusualintheUGLR (Moen 1966). deernumbersovermuch oftheUGLR haverecoveredThe highernutritionalplaneintheseagricultural considerablyduetoa returntomore normalwintersareashelpsdeertowithstandcoldweather(Moen and tighterrestrictionson deerhunting(Mechand1966).They spendmuch oftheiractiveand resting Karns1977,4).However,innortheasternMinnesota,timeneartheirfoodsuppliesinopenfieldsand are where lossestotimberwolvesarehigh(Mech andnotaslikelytouseheavycoverinwinterasaredeer Karns 1977),no increaseindeernumbers was de-farther north (Verme 1965, Moen 1966, Wetze11972). tected through 1978 (Floyd et al. 1979).Deer in agricultural areas also show faster growthrates and higher reproductive rates than those in theforested north, yearling bucks in southern Minne-sota.average 130 pounds (59 kg) field-dressed, while RESEARCH NEEDS INthose in northeastern Minnesota average only 106 THE UPPER GREATpounds (48 kg). 2Between 29 and 52 percent of female LAKES REGIONfawns in southern Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michi-gan become pregnant compared with only 3 to 11 Additional information is needed on deer diets inpercent in the northern portions of those states the snowfree seasons. Most previous studies in the(Verme and Ullrey 1972, Harder 1980). ' UGLR were conducted in winter because it is then

Deer in agricultural areas are able to achieve very that food is scarcest and starvation greatest. How-high densities where hunting and other human- ever, it is now known that deer in the UGLR arerelated mortality factors are controlled. A confined "semi-hibernators"; in winter, their metabolic ratesherd at the Twin Cities Army Ammunition Plant decrease, they are less active, and they require less(TCAAP) achieved a density of 200 deer per square food (Silver et al. 1969, Thompson et al. 1973, Moenmile (77/km2) 3, which is several times higher than 1978). Studies of captive deer in northern Michigandensities recorded anywhere in the UGLR (Olson showed some deer can survive overwinter even if1938, Erickson et al. 1961). Deer at the TCAAP they have no food for several weeks (Ozoga andusually survived overwinter by digging through Verme 1970). It is now apparent that overwintershallow snow for herbaceous material 3. In years survival depends notonly on winterconditionsbutonwhen access to herbaceous material was prevented the energy reserves deer accumulate before winterbyan icecrust, fawns starved 3. Herbaceous material begins (Mautz 1978).is seldom available during winter in northern Min- Knowledge of spring diet might prove useful tonesota forests, managers because the spring diet of pregnant does is

Deer habitat in northern Lake and Cook Counties, especially crucial to the survival of their fawnsin the northeastern corner of Minnesota, is (Verme 1962). Studies of captive deer showed that.deteriorating due to succession of aspen forest to fawn mortality was less than 33 percent when moth-balsam fir and spruce (Erickson et al. 1961, Urich ers that were undernourished in winter were we11-

1973, Mech and Karns 1977). Nevertheless, the area nourished in spring. However, when mothers werestill appears capable, from a food standpoint, of undernourished in both winter and spring, fawn

• supporting at least 10 deer per square mile (4]km2) 3. mortality rose to 90 percent (Verme 1962). Growth ofHowever, during the late 1960s and early 1970s, a fawns depends largely on summer and fall nutrition,series 0f winters with unusually deep or long-lasting and the fall weight of female fawns largely

snow caused starvation and reproductive failure determines whether or not the fawns will breed, among those deer and made escape from timber (Harder 1980).

wolves more difficult (Mech and Karns 1977). These Information on diet during the snowfree months isnatural factors, together with hunting by man, caused difficult to obtain because present techniques are nota severe decline in the deer population during the well suited for determining diet during that period.early1970s(MechandKarns1977).Deernumbersfell One of the most common techniques, examiningto fewer than two per square mile (1/kin2) (Floyd et al. feeding sites, depends upon deer leaving part of each1979) in some areas that formerly had been among the food plant behind so observers can see that some hasbest deer hunting areas in the state (Olson 1938). Deer

2Unpublished data by Ludwig and Karns on file.3personal communication with Karns, 1978. 4personal comunication with Win. Creed, 1980.

" 4

been eaten. This is a suitable method for approximat- seasons would reveal any day-night differences ining use ofwoody browse and large herbaceous plants, habitat use and any seasonal differences in daily

" However, any feeding on small plants that are nipped consumption rates. The validity of this approachoff Close to the ground, and any feeding on items that might be tested, in part, by determining whether thedeer eat whole (mushrooms, berries, acorns, nuts, tame deer survive, reproduce, and raise young asdried leaves, and lichens) is difficult to detect by this successfully as wild ones under conditions of severemethod. Moreover, unless radio-collared deer are winters and predation by timber wolves. The numberused;feeding sites are difficult to find in the forest, so of deer required for such study would depend uponthose examined •tend to be in open or muddy areas the extent to which individuals differed from onewhere deer or their tracks are more visible (Peek another in their food preferences.1975). According to Wallmo et al. (1973), inability to Land managers need more information on year-distribute the feeding site sample in proper relation round diet in order to determine which timber man-to the distribution of deer feeding leads to underesti- agement practices produce the best deer habitats.mation0fuse of shrubsandforbsand overestimation Information on year-round diet also is needed toof Use of grasses. Aquatic feeding is missed entirely, determine the effects of such natural factors as fire,

Other problems with this method are determining drought, plant disease, and defoliating insects onhowmuch of each species was eaten and whether deer habitat. These factors can change both the kindsbrowsing occurred days or months before the exami- and the nutritional values of the plants available tonations (Peek 1975). deer (McEwen and Dietz 1965, Halls and Epps 1969,

Rumen analyses also are fraught with problems. Urich 1973, Lyon et al. 1978, Ohmann and GrigalUsually only a small portion of the rumen material is 1979). Information on year-round diet will lead to aidentifiable, with the identifiable items often being better understanding of the relations between deerthe least digestible ones (Bergerud and Russell 1964). and their habitat and will enable land managers toMoreover, rumen contents usually are collected from maximize the benefits from deer habitat manage-deer killed along roads or in large open areas. Conse- ment funds.

: quently, results are biased toward roadside grassesandother foods that grow in the open. In areas of low

deer density, obtaining adequate samples of rumens LITERATURE CITEDin all seasons is another major difficulty.

Recently, Observations of tame, harnessed deer Aldous, S. E., and C. F. Smith. 1938. Food habits ofhave been used to determine summer food habits. Minnesota deer as determined by stomach analy-Where comparisons have been made, food selections sis. Transactions of the North American Wildlifeby,tame deer did not differ from those of wild deer in Conference 3:756-767.

similar habitats (Healy 1967, Longhurst et al. 1968, Bartlett, I. H. 1938. White-tail--presenting Michi-Wallmo and Neff1970). However, in all studies using gan's deer problem. Michigan Department of Con-tame white-tailed deer, the researcher selected the servation Game Division Bulletin, 64 p.feedinghabitat. None of the available methods can beused to determine seasonal changes in amounts Bauer, W. A. 1977. Forage preferences of tame deer

' Consumed per day. in the aspen type of northern Michigan. 85 p.M.S.Clearly, there is a need to develop improved tech- Thesis, Michigan Technological University.

niques for determining food habits--especially for Houghton, Michigan.the snowfree months. An observation by Watts Behrend, D. F. 1966. Correlation of white-tailed deer(1964) that an escaped tame deer remained tame activity, distribution and behavior with climatic

4 ' after 2 weeks of freedom suggests that harnesses are and other factors. New York State Conservationunnecessary and that attempts should be made to Department, Job Completion Report, Projectstudy tame radio-marked deer living unfettered and W-105-R-7, 78 p.full time on natural ranges. Such deer could become Bergerud, A. T., and L. Russell. 1964. Evaluation offully familiar with the habitats and foods available in rumen food analyses for Newfoundland Caribou.their homeranges and could select them without Journal of Wildlife Managment 28(4):809-814.being hindered by researchers. Feeding data ob- Botkin, D. B., P. A. Jordan, A. S. Dominski, H. S.tained by observing these deer would not be biased in Lowendorf, and G. E. Hutchinson. 1973. Sodiumthe ways inherent in the other methods mentioned, dynamics in a northern ecosystem. Proceedings ofAround-the-clock observations of these deer in all theNationalAcademyofScience70(10):2745-2748.

5

Byelich, j. D. 1965. Deer and forest management: Grigal, D. F., L. F. Ohmann, and N. R. Moody. 1979.Lake States. Proceedings of American Foresters Nutrient content of some tall shrubs from North-

" 233-234. eastern Minnesota. U.S. Department of Agricul-

Church, D.C: 1977. Livestock feeds and feeding. 349 ture Forest Service, Research Paper NC-168, 10 p.p. D. C. Church, publisher. O and B Books, Distrib- U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service,utor. Corvallis, Oregon. North Central Forest Experiment Station, St.

Paul, Minnesota.Cob!entz, B. E. 1970. Food habits of George Reserve

deer. Journal of Wildlife Management 34(3):535- Gullion, G. W. 1977. Maintenance of the aspen eco-540. system as a primary wildlife habitat, p. 256-265 In

XIIIth International Congress of Game Biology. T.Crawford, H. S., J. B. Whelan, R. F. Harlow, and J. E.

Skeen. 1975_ Deer range potential in selective and J. Peterle, ed. Proceedings of The Wildlife Society,clearcutoak-pine stands in southwestern Virginia, Wildlife Management Institute, Washington, D.C.U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Halls, L. K., and E. A. Epps, Jr. 1969. Browse qualityResearch Paper SE-134, 12 p. U.S. Department of influenced by tree overstory in the south. JournalAgriculture Forest Service, Southeastern Forest of Wildlife Management 33(4):1028-1031.

"Experiment Station Asheville, North Carolina. Hammerstrom, F. N., Jr., and J. Blake. i939. WinterCushwa, C. T:, R. L. Downing, R. F. Harlow, a_d D.F. movements and winter foods of white-tailed deer in..

Urbston. 1970. The importance of woody twig ends central Wisconsin. Journal of Mammalogy 20:315-to deer in the Southeast. U.S. Department of Agri- 325.culture Forest Service, Research Paper SE-67, 12p. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Hanson, H. C., and R. L. Jones. 1977. The biogeoche-Southeastern Forest Experiment Station, Ashe- mistry of blue, snow, and Ross' geese. 320 p. IllinoisNatural History Survey. Urbana, Illinois.ville, North Carolina.

Dahlberg, B. L., and R. C. Guettinger. 1956. The Harder, J. D. 1980. Reproduction of white-tailed deer. white-tailed deer in Wisconsin. Wisconsin Conser- in the north central United States. P. 23-35. In

vation Department Technical Wildlife Bulletin 14. Ruth L. Hine and Susan Nehls, eds. White-taileddeer population management in the north-central

282 p. Madison, Wisconsin. States. Proceedings 1979 Symposium North Cen-Edwards, R. Y. i956. Snow depths and ungulate tral Section Wildlife Society. 116 p.

abundance in the mountains of western Canada.Journal of Wildlife Management 20(2)'159-168 Harlow, R. F., and R. G. Hooper. 1971. Forages eaten

• by deer in the southeast. Southeast Association ofEnvironmental Science Services Administration. Game and Fish Commissioners Annual Confer-" 1968. Climatic atlas of the United States. 80 p. U.S. ence Proceedings 25"18-46.

Department of Commerce.Healy, W. M. 1967. Forage preferences of captive

Er.ickson, A. B., V. E. Gunvalson, M. H. Stenlund, D. deer while free- ranging in the Allegheny NationalW. Burcalow, and L. H. Blankenship. 1961. The Forest. 93 p. M.S. Thesis. Pennsylvania State

•white-tailed deer in Minnesota. Minnesota Depart- University, University Park, Pennsylvania.•: ' ment of Conservation Technical Bulletin 5, 64 p.

Irwin, L. L. 1974. Relationship between deer andFloyd, T.J., L. D. Mech, and M. E. Nelson. 1979. An moose on a burn in northeastern Minnesota. 51 p.

improved method of censusing deer in deciduous- M.S. Thesis, University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho.coniferous forests. Journal of Wildlife Manage-ment 43(1):258-261. Jordan, P. A. 1967. Ecology of migratory deer in the

Formozov, A. N. i946. Snow cover as an integral San Joaquin river drainage. 278 p. Ph.D. Disserta-factor of the environment and its importance in the tion. University of California, Berkeley, California.ecology Of mammals and birds. Materials for Jordan, P. A., D. B. Botkin, A. S. Dominski, H. S.Fauna and Flora of the USSR. New series Zoology Lowendorf, and G. E. Belovsky. 1974. Sodium as a5, 152 p, (Translation from Russian) Boreal Insti- critical nutrient for the moose of Isle Royale.

•tute, University of Alberta. Proceedings of the North American Moose Confer-ence Workshop 9:13-42.Gilbert, P. F., O. C. Wallmo, and R. B. Gill. 1970.

Effect of snow depth on mule deer in Middle Park, Joyal, R., and B. Scherrer. 1978. Summer movementsColorado. Journal of Wildlife Management and feeding by moose in western Quebec. Canadian34(!):15-23. Field:Naturalist 92(3):252-258.

.

o

6

Julander, O_, and W. L. Robinette. 1950. Deer and McCaffery, K. R., and W. A. Creed. 1969. Signifi-cattle range relationships on Oak Creek range in cance of forest openings to deer in northern Wis-Utah. Journal of Forestry 48(6):410-415. consin. Wisconsin Department Natural Resources

Karns, P. D. 1980. Winter--the grim reaper. Pro- Technical Bulletin 44, 104 p.ceedings of the Symposium on white-tailed deer McCaffery, K. R., and B. E. Kohn. 1971. Relation ofmanagement in the North Central U.S. [In press], forest cover types to deer populations. Wisconsin

Kohn, B. E. 1970. Summer movements, range use, Department of Natural Resources Progress Report,and food habits of white-tailed deer in north cen- Project W-141-R-6, Study 201, 9 p. mimeo.tral Minnesota. 38 p.M.S. Thesis, University of McCaffery, K. R., J. Tranetzke, and J. Piechura, Jr.Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota. 1974. Summer foods of deer in northern Wisconsin.

Kohn, B. E., and J. J. Mooty. 1971. Summer habitat of Journal of Wildlife Management 38(2):215-219.White-tailed deer in north central Minnesota. McEwen, L. C., and D. R. Dietz. 1965. Shade effectsJournal of Wildlife Management 35(3):476-487. on chemical composition of herbage in the Black

Krefting_ L. K., and H. L. Hanson. 1963. Use of Hills. Journal of Range Management 18(4):184-.phytocides to improve deer habitat in Minnesota. 190.Southern Weed Control Conference (Mobile, Ala- Mech ,L. D., and P, D. Karns. 1977. Role of the wolf inbama) 16:209-216 a deer decline in the Superior National Forest. U.S.

Levin, D. A. 1976. The chemical defenses of plants to Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Re-pathogens and herbiVores. Annual review of ecol- search Paper NC-148, 23 p. U.S. Department of

Agriculture Forest Service, North Central Forestogy and systematics 7:121-159. Experiment Station, St. Paul, Minnesota.

Linn, J. G., R. D. Goodrich, J. C. Meiske, and J. Staba. Miguelle, D. G., and P. A. Jordan. 1980. The impor-1973. Aquatic plants from Minnesota: Part 4--nu- tance of diversity in the diet of moose. In Proceed-trient composition. Water Resources Research ings 15th North American Moose Conference

• Center Bulletin 56, 22p. University of Minnesota, Workshop. [In press].St. Paul, Minnesota.

Moen, A. N. 1966. Factors affecting the energy ex-Longhurst, W. M., A. S. Leopold, and R. F. Dasmann. change and movements of white-tailed deer in

1952, A survey of California deer herds, their western Minnesota. 121p. Ph.D. Thesis, Univer-ranges and management problems. California De- sity of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota.partment ofFish and Game. Game Bulletin 6,136 p.

Moen, A. N. 1968. Surface temperatures and radiantL0nghurst, W. M., H. K. Oh, M. B. Jones, and R.E. heat loss from white-tailed deer. Journal of Wild-

Kepner. 1968. A basis for the palatability of deer life Management 32(2):338-344.forage plants. North American Wildlife Proceed-ings_33:181.192. Moen, A. N. 1976. Energy conservation by white-

tailed deer in the winter. Ecology 57:192-198.Lyon, L. J., H. S. Crawford, E. Czuhai, R. L. Fredrik-

son, R. F. Harlow, L. J. Metz, and H. A. Pearson. Moen, A. N. 1978. Seasonal changes in heart rates,1978, Effects of fire on fauna. U.S.Department of activity, metabolism, and forage intake of white-Agriculture ForestService, General Technical Re- tailed deer. Journal of Wildlife Managementport WO-6. 41 p. 42:715-738.

•MaUtz, W. W. 1978. Sledding on a bushy hillside: the Mooty, J. J. 1971. The changing habitat scene, p. 27-fat cycle in deer. Wildlife Society Bulletin 6(2):88- 33. In The white-tailed deer in Minnesota. M. N.90. ' Nelson, ed. 88 p. Minnesota Department of Natural

Resources.Maycock, P. F., and J. T. Curtis. 1960. The phytosoci-

ology of boreal conifer-hardwoods forests of the Mooty, J. J. 1976. Year-round food habits of white-Great Lakes Region. Ecological Monograph 30:1- tailed deer in northern Minnesota. Minnesota35. Wildlife Research Quarterly 36(1):11-36.

McCaffery, K. R. 1976. Vegetation characteristics of Nagy, J. G., and W. L. Regelin. 1977. Influence ofaspenstands. Wisconsin Department of Natural plant volatile oils on food selection by animals.Resources Final Report, Project W-141-R-11, XIIIth International Congress of Game Biolo-Study 205, 27 p. mimeo, gists:225-230.

7

Nagy, J. G.I and R. P. Tengerdy. 1968. Antibacterial Stenlund, M. 1970. Deer wintering conditions andaction of essential oils ofArtemisia as an ecological mortality report. Minnesota Quarterly 30(2):102-

• factor, iI. Antibacterial action of the volatile oils of 103.

Artemisia otridentata (big sagebrush) on bacteria Stone, R. N. 1966. A third look at Minnesota's timber.from the rumen of mule deer. Applied Microbiology U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service16:441-444. Bulletin NE-1, 64 p. U.S. Department of Agricul-

Nagy, J. G., H. W. Steinhoff, and G. M. Ward. 1964. ture Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experi-Effects of essential oils of sagebrush on deer rumen ment Station, Broomall, Pennsylvania.

microbial function. Journal of Wildlife Manage- Swift, E. 1946. A history of Wisconsin deer. Wisconsinment 28:785-790. Conservation Department Publication 323, 96 p.

Nelson, M. E., and L. D. Mech. 1980. Effects of winter Swift, E. 1948. Deer select most nutritious forages.severity on winter deer weights in Minnesota. Journal of Wildlife Management 12:109-110.Journal .of Wildlife Management [In press].

Taylor, W. P. 1956. The deer of North America. 668 p.Ohmann, L. F., and D. F. Grigal. 1979. Early revege- The Stackpole Company and The Wildlife Manage-

tation and nutrient dynamics following the 1971 ment Institute, Washington, D. C.Little Sioux forest fire in northeastern Minnesota.Forest Science Monograph 21, Supplement t_oFor- Thompson, C. B., J. B. Holter, H. H. Hayes, H. Silver,

and W. E. Urban, Jr. 1973. Nutrition of white-est Science 25(4), 80 p. tailed deer. I. Energy requirements of fawns. Jour-

Ohmann, L. F., and R. R. Ream. 1971. Wilderness nal of Wildlife Management 37(3):301-311.ecology: virgin plant Communities of the BoundaryWatersCanoe Area. U.S. Department of Agricul- Townsend, M. T., and M. W. Smith. 1933. The white-

tailed deer of the Adirondacks. (1) Preliminaryture Forest Service Research Paper NC-63, 55 p.U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, survey of the white-tailed deer of the Adirondacks,

•North-Central Forest Experiment Station, St. (2) Ecology of the white-tailed deer in summer withspecial reference to Adirondacks. Roosevelt Wild-

. Paul, Minnesota. life Bulletin 6(2):161-325.Ols0n_ H. F. 1938. Deer tagging and population

studies in Minnesota. Transactions North Ameri- Ullrey, D. E., W. G. Youatt, H. E. Johnson, P. K. Ku,can Wildlife Conference 3:280-286. and L. D. Fay. 1964. Digestibility of cedar and

aspen browse for the white-tailed deer. Journal ofOrke, D. N. 1966. Patterns and intensity of white- Wildlife Management 28(4):791-797.

tailed deer browsing on the woody plants of Itasca• State Park. 61 p. M. S. Major Report. University of Ullrey, D. E., W. G. Youatt, L. D. Fay, B. E. Brent,

Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota. and K. E. Kemp. 1967. Digestibility of cedar andjack pine browse for the white-tailed deer. Journal

Ozoga, J. J., and L. J. Verme. 1970. Winter feeding of Wildlife Management 31(3):448-454.patterns of penned white-tailed deer. Journal ofWildlife Management 34(2):431-439. Ullrey, D. E., W. G. Youatt, L. D. Fay, B. E. Brent,

and K. E. Kemp. 1968. Digestibility of cedar and•- . Peek, J. M. 1975. A review of moose food habits balsam fir browse for the white-tailed deer. Jour-

studies in North America. Naturaliste Canadien nal of Wildlife Management 32(1):162-171.

10i:193-215. U.S. Department of Interior. 1977. 1975 national• j

Pierce,D. E., Jr. 1975. Spring ecology of white-tailed survey of hunting, fishing, and wildlife-associateddeer in north central Minnesota. 55 p. M. S. Thesis. recreation. 91 p. U.S. Department of the Interior.University of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota. Urich, D. L. 1973. Nutrient levels in deer and moose

Silver, H., N. F. Colovos, J. B. Holter, and H.H. forage in northern Minnesota as related to siteHayes. 1969. Fasting metabolism of white-tailed characteristics. 138 p.M.S. Thesis University ofdeer. Journal of Wildlife Management 33(3):490- Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota.

498. . Verme, L. J. 1962. Mortality of white-tailed deerSkinner, W. R., and E. S. Telfer. 1974. Spring, fawns in relation to nutrition. Proceedings Na-

summer, and fall foods of deer in New Brunswick. tional Deer Disease Symposium 1"15-38.

Journal of Wildlife Management 38(2):210-214. Verme, L. J. 1963. Effect of nutrition on growth ofStenlund, M. 1958. A history of Itasca County deer. white-tailed deer fawns. Transactions North

Conservation Volunteer 21(125): 19-24. American Wildlife Conference 28:431-443.

.

8

Verme, L. J. 1965. Swamp conifer deer yards in Reichert. 1973. Accuracy of field estimates of deernorthern Michigan. Journal of Forestry 63(7):523- food habits. Journal of Wildlife Management

-529. 37(4):556-562.

Verme, L. J. 1969. Reproductive patterns of white- Wambaugh, J. R. 1973. Food habits and habitattailed deer related to nutritional plane. Journal of selection by white- tailed deer, and forage selectionWildlife Management 33:881-887. in important habitats in northeastern Minnesota.

Verme, L. J., and D. E. Ullrey. 1972. Feeding and 71 p. M.S. Thesis. University of Minnesota, St.nutrition of deer. p. 275-291. In Digestive physiol- Paul, Minnesota.ogy and nutrition of ruminants, vol. 3: practical Watts, C. R. 1964. Forage preferences of captive deer.nutrition. D. C. Church, ed. publisher and Oregon while free- ranging in a mixed oak forest. 65 p. M.S.State University Bookstores, distributor Corvallis, Thesis. Pennsylvania State University, UniversityOregon. _ Park, Pennsylvania.

Waddell, B. H., Jr. 1973. Fall ecology of white-tailed Weir, W. C., and D. T. Torell. 1959. Selective grazingdeer inlnorth central Minnesota.'46 p.M.S. Thesis. by sheep as shown by a comparison of the chemicalUniversity of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota. composition of range and pasture forage obtained

Wallmo, D. C., and D. J. Neff. 1970. Direct observa- by hand clipping and that collected by esophagealtions of tamed deer to measure their consumption fistulated sheep. Journal of Animal Scienceof natural forage, p. 105-110. In Range and Wildlife 18:641-649.Habitat Evaluation--A Research Symposium. Wetzel, J. F. 1972. Winter food habits and habitatU.S.. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, preferences of deer in northeastern Minnesota. 106Miscellaneous Publication 1147, 220 p. p.M.S. Thesis. University of Minnesota, St. Paul,

WalImo, O. C.; R. B. Gill, L. H. Carpenter, and D.W. Minnesota.

. 9

APPENDIX°

Table 1.---Plants eaten by white-tailed deer in northern Minnesota in January

(In estimated percents of the diet) z-.

Feedinqsites Rumens

North-central Northeast (northeast)1971-19742 1971s 19724 1971s

Beakedhazel ' 37 30 35 16Mountainmaple 10 29 25 3Dogwood 1 15 10 6Juneberry 12 6 14 2Arboreallichens ' 14Balsamfir <1 < 1 13Green.alder 8 1 1 8Blueberry 8Redmaple 4 6Quakingaspen 2 4 1Paperbirch 4 1 1Grasses <1 4

,' Goldthread 4Cherry 2 1 3 3Labradortea 3 2 1•Whitecedar < 1 3 < 1White pine 2 1Blackspruce 2Wintergreen 2Willow 1 1 1 <1

Speckledalder < 1 < 1 1•Bush-hOneysuckle < 1 1Arrowwood 1 <1Redoak <1 <1Honeysuckle <1 <1Jackpine <1Unidentifiedleaves 6Unidentifiedtwigs 15

Numberexamined 9 26 16 8Numberof bites 2,064 24,797 7,027

_Not.includedintables1-3and12are22taxawhoseusebydeerdid.notexceed1.5percentofthedietinanystudyinanymonthduringDecember-March.Thesetaxain¢!udeclubmoss,brackenfern,mosses,large-leafaster,blackmedic,strawberry,marshmarigold,goldenrod,thistles,trailingarbutus,redraspberry,gooseberry;rose,:redelderberry,leatherleaf,sweetgale,swampbirch,sumac,mountain-ash,blackash,balsampoplar,andredpine.

2Mooty(unpublished)..DataforDecember-Marchwereobtainedbyexamining43feedingsitesinItascaCounty,north-centralMinnesota,during1971-1974.Forasummaryofthesedataby2-monthintervals,seeMooty(1976).Deerdensityduringthestudywas4to8deerpersquarekilometeranddeclining,accordingtoannualspringpelletcountsconductedbytheMinnesotaDepartmentofNaturalResources.

3FromWetzel(1972).DataforDecember-Marchwereobtainedbyexamining82feedingsitesand32wolf-killedrumensinSt.LouisandLakeCountiesin•northeasternMinnesotaduring1968-1971.Deerdensitywas4to6deerpersquarekilometeranddeclining(P.D.Karns,1979,personalcommunication;MechandKarns1977;Rogersetal.1980).

4FromWambaugh(i973).DataforJanuary-Marchwereobtainedbyexamining50feedingsitesin1972inthesameareathathadbeenstudiedbyWetzel(above).

' i0

Table 2.--Plants eaten by white-tailed deer in northern Minnesota in February

" (In estimated percents of the diet) 1

Feedingsites RumensNorth-central Northeast (northeast)

" 19722 1971a 19724 19713

White.cedar 8 52Beaked.,hazel 35 33 48 4Mountainmaple 29 37Labradortea " 14 1Whitepine 3 12Blueberry 10Jackpine 9 8Juneberry 8 2 4 1Dogwood 8 1 2Willow ' 6 1 <1Speckledalder 5 2 <1 5Balsamfir • 1 5Redmaple 5 2Arboreallichens 4Honeysuckle 3 <1Quakingaspen 2 2Arrowwood 2 <1

, Greenalder. 2 <1 <1Hawthorn 2Americanhazel 2Cherry 1 1 1 <1Paperbirch <1 1 <1 1Wintergreen 1Sweetfern 1Redoak <1 < 1Bush-honeysuckle < 1Blackspruce <1Grasses,sedges <1Unidentifiedleaves 1•

Unidentifiedtwigs 4Numberexamined 7 37 20 15

, Numberof bites 1,458 35,200 12,616

_Notincludedin,tables1-3and12are22taxawhoseusebydeerdidnotexceed1.5percentofthedietinanystudyinanymonthduringDecember-March.Thesetaxaincludeclubmoss,brackenfern,mosses,large-leafaster,blackmedic,strawberry,marshmarigold,goldenrod,thistles,trailingarbutus,redraspberry,

, gooseberry,rose_redelderberrylleatherleaf,sweetgale,swampbirch,sumac,mountain-ash,blackash,balsampoplar,andredpine.2Mooty(_npublished).DataforDecember-Marchwereobtainedbyexamining43feedingsitesinItascaCounty,north-centralMinnesota,during1971-1974.For

asummaryofthesedataby2-monthintervals,seeMooty(1976).Deerdensityduringthestudywas4to8deerpersquarekilometeranddeclining,accordingtoannual.springpelletcountsconductedbytheMinnesotaDepartmentofNaturalResources.

, 3FromWetzel(i972).DataforDecember-Marchwereobtainedbyexamining82feedingsitesand32wolf-killedrumensinSt.LouisandLakeCountiesinnortheasternMinnesotaduring1968-1971.Deerdensitywas4to6deerpersquarekilometeranddeclining(P.D.Karns,1979,personalcommunication;MechandKarns1977;Rogerseta/.1980). '

4FromWambaugh(1973).DataforJanuary-Marchwereobtainedbyexamining50feedingsitesinthesameareathathadbeenstudiedbyWetzel(above).

' 11

Table 3._Plants eaten by white-tailed deer in northern Minnesota in Marcho

" (In estimated percents of the diet) z_

Feedinqsites RumensNorth-central Northeast (northeast)

. 19722 1971a 19724 1971a 1937s

Beaked.hazel 52 44 51 4Balsamfir 1 <1 5 43Whitecedar. _ 26 35 3Jack.pine 5 17Mountain-maple , 12 16Pine 14Juneberry. 8 , 2 11Dogwood 3 1 4 9 <1Paperbirch 5 1 <1 1 5Greenalder 4 ' 5 2 <1Arrowwood <1 <1 5Arboreallichens 5Red,-maple <1 2 4 <1Willow 1 1 <1 1 4

•Cherry 1 1 < 1 3 < 1Speckledalder 1 3 <1Blackspruce 1 3

' Redoak <1 < 1 3 < 1Grasses,sedges <1 3Labradortea <1 3Honeysuckle 3Quakingaspen 2 1 2White pine 2 1Blueberry 2Large-toothedaspen 1Bush-honeysuckle < 1Wintergreen <1Bunchberry <1Unidentifiedleaves 1

.Unidentifiedtwigs 8• .

Othermaterial 7

' NUmberexamined 15 15 14 4 51Numberof bites 3,700 19,666 6,228.

_Notincludedintables1-3and12are22taxawhoseusebydeerdidnotexceed1.5percentofthedietinanystudyinanymonthduringDecember-MarchThesetaxaincludeClubmoss,brackenfern,mosses,large-leafaster,blackmedic,strawberry,marshmarigold,goldenrod,thistles,trailingarbutus,redraspberry,gooseberry,rose,redelderberry,leatherleaf,sweetgale,swampbirch,sumac,mountain-ash,blackash,balsampoplar,andredpine.

2Mooty(unpublished).DataforDecember-Marchwereobtainedbyexamining43feedingsitesinItascaCounty,north-centralMinnesota,during1971-1974.Forasummaryofthesedataby2-monthintervals,seeMooty(1976).Deerdensityduringthestudywas4to8deerpersquarekilometeranddeclining,accordingtoannualspringpelletcountsconductedbytheMinnesotaDepartmentofNaturalResources.

3FromWetzel(!972).DataforDecember-Marchwereobtainedbyexamining82feedingsitesand32wolf-killedrumensinSt.LouisandLakeCountiesinnortheasternMinnesotaduring1968-1971.Deerdensitywas4to6deerpersquarekilometeranddeclining(P.D.Karns,1979,personalcommunication;MechandKarns!977;Rogersetal.1980)..4FromWambaugh(1973).DataforJanuary-Marchwereobtainedbyexamining50feedingsitesinthesameareathathadbeenstudiedbyWetzel(above).5FromAldousandSmith(1938).DatawereobtainedinnortheasternMinnesotabyexamining51rumensfromdeerthathaddiedofstarvation,predation,

sickness,ekposurelorhavingbeenstruckbyvehicleslateinthewinterof1936-1937.Deerdensitywas4to8persquarekilometeraccordingtodeerdrivesConductedbytheCivilianConservationCorpsintheSuperiorNationalForestin1936.

.12

Table 4.---.Plants eaten by white-tailed deer in north- Table 5.--Plants eaten by white-tailed deer in north-ceritral Minnesota in April of 1970 and 1971 central Minnesota in May of 1970 and 1971

. ,

(In esti_mated percents of diet) 1 (In estimated percents of diet) 1

Feedingsites Rumens Feedingsites RumensWhite-cedar 48 Grasses 45 7Beakedhazel 21 2 Sedges 17•Greenalderandspeckledalder 2 18 Willow 3 6Bush-honeysuckle 15 Goldenrod(dead) 5.Grasses 14 Marshmarigold 5

1 Redosier .dogwood 10 Redosierdogwood 4 2Latelow blueberry 9 Woodanemone 4Juneberry 6 Brackenfern 4

-Goldenrod.(dead) 5 Trailingarbutus 3Sedges. 5 Falselily-of-the-valley 3Blackash 3 Rose 3Honeysuckle 3 Yellow bellwort 3Marshmarigold 3 Latelow blueberry 3Lichens 2 Large-leafaster- 2UnidentifiedWoodybrowse 30 Clinton's lily 2Numberof sites or rumens Unidentifiedleaves 64

examined 11 5 Unidentifiedforbs 13Numberof bites 1,833 Numberof sites or rumens

1FromPterce(1975).Datawereobtainedbyexamining39feedingsites examined 16 3. and3 rumensinItascacounty,northcentralMinnesota,duringApril-June Numberof bitestallied 4,595

t970-1971.FiverumensfromdeerthatstarvedinAprilinItascaCountywere 1FromPierce(1975).Foradditionaldetailsofthestudy,seefootnotetoexamined.Deerdensitywas4 to8 persquarekilometeranddeclining, table4. Itemsusedbydeerinamountslessthan2percentinMayincludeaccordingto annualspringpelletcountsconductedbytheMinnesota hazel,quakingaspen,andpyrola.DepartmentofNaturalResources.ItemsusedinamountslessthantwopercentinAprilincludedtwigsofpaperbirch,quakingaspen,andcherryandsprigsofjackpineandwhitepine.Bush-honeysuckle,grass,sedge,andmarshmarigoldwereeatenmainlyinlateAprilaftersomesnowhadmelted.

°

13

Tabl e 6.--Plants eaten by white-tailed deer in the northern Great Lakes Region in June.

(In estimated percents of the diet) _

- Feedingsites Observationof tame deer(Minnesota) Rumens (Michigan)

Forest2 Burn3 Minnesota4 Wisconsins Aspen6 Clearcut6

Aspen 1 16 6 29 21 37Redmapleand

mountainmaple 8 22 14 5 1 9Brackenfern 13 < 19 7Dogwood 1 18Beakedhazel 9 4 14 16Bush-honeysuckle 1 . 16 5Strawberry 2 5 15 4 9Wildsarsaparilla 14 <Lilyfamily 2 12 3 <Watermilfoil 11

!

Raspberry 8 5Willow 8 1 4 <Hawkweed 8 2 <Honey_,uckle 8Grassesandsedges 7 3 6 6 2 2Chokecherry 1 7 6Aster,mainly

large-leafedaster 6 1 6 2'Paperbirch 1 6 2 <Sweetpea 5 5Yellowbellwort 4Goldenrod 3 2 3 <Bunchberry 3 < <Juneberry 2 2MiScellaneousspecies 20Unidentifiedleaves 9

Numberof sitesorrumensexamined 12 6 3 24

Numberof bites 2,763 492

1Plantswhoseusebydeerdidnotreach2percentofthedietinanystudyinJuneweremushrooms,pyrola,bluebell,spreadingdogbane,violet,goosefoot,• . bedstraw,commondandelion,yarrowmpearlyeverlasting,indianhemp,hedgebindweed,scarletcolumbine,fireweed,thistle,latelowblueberry,thimbleberry,

currant,rose:arrowwood,blackash,buroak,andwhitespruce.. 2FromPierce(1975).Foradditionaldetailsofthestudy,seefootnotetotable4.

3FromIrwin(1974).Datawereobtainedbyexamining52feedingsitesintheLittleSiouxBurnareainSt.LouisCounty,northeasternMinnesotaduringApril-December1973.Deerdensitywas4 to6 persquarekilometer(P.D.Karns,1979,personalcommunication).

4FromKohn(1970).Datawereobtainedbyexamining31feedingsitesand9rumensinItascaCounty,north-centralMinnesota,duringJune-August1968-1969.DeerpopulationdataareasforPierce(1975)(above).Kohndidnotmentionbyname11browseand20forbtaxaeachofwhichaccountedfornomorethan2percentofthedietinanymonthofstUdy,

SFromMcCafferyetal.(1974).DatawereobtainedinnorthernWisconsinduring1969-1970byexamining76rumensfromroad-killeddeer(15inApril-May,42inJune-September,19inOctober-November).Seventygenera,excludinggeneraofgrasses,sedges,andmushrooms,werefoundinthe76rumens,but17itemsaccountedfor80percent.oftheaggregatevolumesfoi"April-November.These17itemswereaspenleaves(16percent),graminoids(1percent),barrenstrawberry(7percent),aster(5percent),bush-honeysuckle(6percent),strawberry(4percent),cherry(4percent),oakacorns(6percent),wintergreen(3percent)clover(4percent),mushrooms(2percent),mapleleaves(2percent),solomon'sseal(2percent),falselily-of-the-valley(2percent),andbunchberry(2percent).Approximatelymonthlybreak-downsareavailableforJuneonly.Deerdensitywas6 to8persquarekilometeranddeclining(Wm.F.Creed,1978,personalcommunication).

6FromBauer(1977).Datawereobtainedbyobservationof3tame,harnesseddeerinalO-acrematureaspenstandandinanadjacent1O-acre1-year-oldaspenclearcutdur!ngJune-August1976inDickinsonCountyinMichigan'sUpperPeninsula.Deerdensitywas11persquarekilometeranddeclining(L.F.Verme,1979,personalcommunication).

Table 7.--Plants eaten by white-tailed deer in the northern Great Lakes Region in Julyo

(In estimated percent of the diet) _

Feedingsites Rumens Observationsof tamedeer(Minnesota) (Minnesota) (Michigan)

Forest7 Burns Forest4 Aspen6 Clearcut6

Aspen 7 3 22 26 20Beaked-hazel 26 9 20Strawberry 3 11 10 17

•Redandmountainmaple 10 5 16 8 ,13Goldenrod _ 1 12 4 2 3Chokeandpin cherry <1 12 4 3 2Brackenfern . 3 3 12 3Asterslmainly

large-leafedaster 9 10 3 5Raspberry 1 10 6Roughcinquefoil , 10Willow 9 4 2

; Juneberry 3 8 ;2I Spottedjewelweed 3 8

BUsh-honeysuckle < 1 2 7Grasses.andsedges 1 6 2 2Violet <1 5Paperbirch 3 4 1 <1

• Commongeranium 4' Watermilfoil 4

Fireweed 3Clover 2 2Hedgebindweed 2 2Falselily-of-the-valley 1 2 <1Hawkweed 2 <1

: Spreadingdogbane 1 2Bicknell'sgeranium 2Mushrooms <1 2Arrowwood 2Unidentifiedleaves 7Miscellaneousspecies 17

, ' Numberof feedingsitesor rumensexamined 21 8 3

Numberof bitestallied 5,098 778

_Plantswhoseusebydeerdidnotreach2percentofthedietinAugustincludedHawkweed,commondandelion,roughcinquefoil,pyrola,pearlyeverlasting,

t blacksnakeroot,meadow indianhemp,bluebell,sweeffern,barren arrowwood,thistle,bedstraw,mint,wildlettuce, bindweedwildrue, strawberry, hedge

' sarsaparilla,honeysuckle;greenalder,andwhitespruce.• 3FromIrwin(1974).Datawereobtainedbyexamining52feedingsitesintheLittleSiouxBurnareainSt.LouisCounty,northeasternMinnesotaduringApril-

December1973.Deerdensitywas4 to6 persquarekilometer.(P.D.Karns,1979,personalcommunication).4FromKohn(1970).Datawereobtainedbyexamining31feedingsitesand9rumensinItascaCounty,north-centralMinnesota,duringJune-August1968-1969.

DeerpopulationdataareasforPierce(1975)(above).Kohndidnotmentionbyname11browseand20forbtaxaeachofwhichaccountedfornotmorethan2percentofthedietinanymonthofstudy.

6FromBauer(1977).Datawereobtainedbyobservationof3tame,harnesseddeerina1O-acrematureaspenstandandinanadjacent1O-acre1-year-oldaspenclearcutduringJune-August1976inDickinsonCountyinMichigan'sUpperPeninsula.Deerdensitywas11persquarekilometeranddeclining(L.F.Verme,1979personalcommunication).7Mooty(unpublished).DatawereobtainedbyexaminingfeedingsitesinItascaCounty,north-centralMinnesotaduring1968-1971.Forasummaryofthesedata

by2-mOnthintervals,seeMooty(1976).SomeofthedatausedbyMootywerecontributedbyKohn(1970)andWaddell(1973).Deerdensitywas4to8persquarekilnmeteranddeclining,accordingtoannualspringpelletcountsconductedbytheMinnesotaDepartmentofNaturalResources.

I

15

Table 8.rePlants eaten by white-tailed deer in the northern Great Lakes Region in August

- (In estimated percent of the diet)_° ,

Feedingsites Observationsoftamedeer' - (Minnesota) Rumens (Michigan)

Forest7 Burns (Minnesota)4 Aspen6 Clearcut6Aspen 8 12 23 9Beakedand

americanhazel 15 <2 15 23BuSh-honeysuckle 7 20 9 "Strawberry 1 <1 9 17Mushrooms 17Chokeandpincherry 3 16 6 4 <1Asters,mainly

large-leafedaster . 15 <2 6 13 2Redandmountainmaple 5 5 9 2 15Raspberry.and

B!ackberry <1 13 4Clover 4 11Paperbirch 6 ' 8 <1 1Fireweed 8Willow 6 5 3 7 2Spreadingdogbane 6 1Spottedjewelweed 6Buckbean 5

•Wildsweetpea 3 4Grassesandsedges 1 3 1 2Juneberry 1 <2 4

' Lillies,mainly•Clinton'slily 3 2 <1

AmericanVetch 1 3BristlySarasparilla <1 3Fringedbindweed 3Goldenrod 2 <1 2 2Rose 1 2BraCkenfern 1 2 <1Dogwood 2 1Thimbleberry 2Violet 2Blueberry 2Basswood 2

Unidentifiedleaves 14Miscellaneousplants 21Numberoffeedingsites

or rumensexamined 26 8 3Numberof bites 7,964 570

, _Plantswhoseusebydeerdidnotreach2percentofthedietinanystudyinAugustincludedHawkweed,commondandelion,roughcinquefoil,pyrola,pearlyeverlasting,blacksnakeroot,meadowrue,indianhemp,bluebell,sweeffern,barrenstrawberry,arrowwood,thistle,bedstraw,mint,wildlettuce,hedgebindweedwildsarsaparilla,honeysuckle,greenalder,andwhitespruce.

3FromIrwin(1974).Datawereobtainedbyexamining52feedingsitesintheLittleSiouxBurnareainSt.LouisCounty,northeasternMinnesotaduringApril-December1973:Deerdensitywas4to6persquarekilometer.(P.D.Karns,1979,personalcommunication).'=FromKohn(1970)..Datawereobtainedbyexamining31feedingsitesand9rumensinItascaCounty,north-centralMinnesota,duringJune-August1968-1969.

DeerpopulationdataareasforPierce(1975)(above).Kohndidnotmentionbyname11browseand20forbtaxaeachofwhichaccountedfornotmorethan2percentofthedietinanymonthofstudy.

8FrOmBauer(1977).Datawereobtainedbyobservationof3tame,harnesseddeerina10-acrematureaspenstandandinanadjacent10-acre1-year-oldaspenCiearcutduringJune-August1976inDickinsonCountyinMichigan'sUpperPeninsula.Deerdensitywas11persquarekilometeranddeclining(L.F.Verme,1979personalcommunication).

7Mooty.(unpublished).DatawereobtainedbyexaminingfeedingsitesinItascaCounty,north-centralMinnesotaduring1968-1971.Forasummaryofthesedataby2-monthintervals,seeMooty(1976).SomeofthedatausedbyMootywerecontributedbyKohn(1970)andWaddell(1973).Deerdensitywas4to8persquarekilometeranddeclining,accordingtoannualspringpelletcountsconductedbytheMinnesotaDepartmentofNaturalResources.

.16

Table 9.--Plants eaten by white-tailed deer in north- Table lO.--Plants eaten by white-tailed deer in north-" ern Minnesota in September ern Minnesota in October

. .

(In estimated percentages of the diet) _ (In estimated percentages of the diet) _Forested Burned

Forested Burned feedingsitese feedingsites3

feedingsitese feedingsitesa Redmaple 49Bush-honeysuckle 24 36 Grassesandsedges 29 5Asters,mainly Bush-honeysuckle 13

I large,leafedaster 33 3 Beakedandamericanhazel 1 12Pincherry 20 Clover 7 11Fringedbindweed 11 Aster,mainlylarge-Clover 10 9 leafedaster 11Mountainmaple ,9 4 Bunchberry 8 2WilloW 6 2 Goldenrod 8Bristlysarsaparilla 6 Paperbirch 1 7

_Clint0n's lily 3 <2 Wintergreen 5 2Goldenrod 3 , Quakingaspen 5 2Brackenfern 3 Jackpine 4Redmaple 2 <2 Juneberry 4Rose " 2 <2 Raspberryand blackberry 2 2Miscellaneousplants 9 Strawberry 2 2

Numberof feedingsites 12 5 Commonthistle 2Numberof bitestallied 2,932 490 Hedgebindweed 2

Miscellaneousplants 81piantswhoseusebydeerdidnotreach2percentineitherstudyinAugust

. includedra.spberry,blackberry,grass,sedge,bunchberry,strawberry, Numberof feedingthistle,beakedhazel,Americanhazel,quakingaspen,andarrowwood, sitesexamined 13 6

3FromIrwin(1974).Datawereobtainedbyexamining52feedingsitesin Numberof bitestallied 5,483 480theLittleSiouxBurnareainSt.LouisCounty,northeasternMinnesotaduringApril-December1973.Deerdensitywas4to6 persquarekilometer(P.D. _Plantswhoseusebydeerdidnotreach2percentofthedietineitherstudyKarnS,1979personalcommunication), inOctoberincludedrose,willow,alder,andfireweed.

eFromWaddell(1973).Datawereobtainedbyexamining41feedingsites 3FromIrwin(1974).Datawereobtainedbyexamining52feedingsitesinduringAugust-October1970-1971inItascaCounty,north-centralMinnesota. theLittleSiouxBurnareainSt.LouisCounty,northeasternMinnesotaduring

•Waddelldidnotmentionbyname56planttaxa,eachofwhichaccountedfor April-December1973.Deerdensitywas4to4 persquarekilometer(P.D.notmorethan2 percentofthedietinanyofthe3 monthsofstudy.Deer Karns,1979,personalcommunication).densitywasfourtoeightsquarekilometeraccordingtocensusdatacollected 8FromWaddell(1973).Datawereobtainedbyexamining41feedingsitesbytheMinnesotaDepartmentofNaturalResources. duringAugust-October1970-1971inItascaCounty,north-centralMinnesota.

Waddelldidnotmentionbyname56planttaxa,eachofwhichaccountedfornotmorethan2 percentofthedietinanyofthe3 monthsofstudy.Deer

. densitywas4-8persquarekilometeraccordingtocensusdatacollectedby, • theMinnesotaDepartmentofNaturalResources.

17

Table l l.---Plants eaten by white-tailed deer in the northern Great Lakes Region in Novembero

.

(I_nestimated percentages of the diet as determined from rumen analyses).

NortheastMinnesota NorthernWisconsin1967-19691 19362 1943a

Large-leafaster 25Easternhemlock 20Quakingaspenandbalsampoplar 4 17 11White-cedar 9 15Balsamfir 13 12Grasses , 11 3 <2Willow 1 11Birch .10 <2Bdnchberry 8 2 <2Redosierdogwood , 8Pine(mainlyjackpine) 1 7 7GreenandSpeckledalder 3 <1 5Labradortea 5Apple 5Boglaurel 4Currantor gooseberry 4Wintergreen 4

• BeakedandAmericanhazel 1 <1 3Twinflower 3 <1Rose 3Maple 2 2Mushrooms,lichens,andmoss 2 <2Commonthistle 2Woodfern 2Wild sweetpea 2Compositefamily 2Unidentifiedtwigs 12 12 1

Numberof rumensexamined 14 21 387

1FromWetzel.(1972).DataforNovemberwereobtainedbyexamining14rumensfromdeerkilledbyhuntersinSt.LouisandLakeCountiesinnortheasternMinnesotaduring1967-1969.Deerdensitywas4to6persquarekilometer(P.D.Karns,1978,personalcommunication),andthepopulationwasdeclining(Mech

• " andKams1977;Rogersetal.1980).Wetzelomittedanddidnotname25itemsthathefoundonlyintraceamountsduringthe3yearsheanalyzedrumens.2FromAldousandSmith(1938).DataforNovemberwereobtainedbyexamining21rumensfromdeerkilledbyhuntersinnortheasternMinnesotain1936.Items

' whichAldousandsmithfoundtocompriselessthan1percentofthedietincludedblackspruce,basswood,clubmoss,raspberry,juniper,goldenrod,clover,grape,grapefern,hardhack,ironwood,Ioosestrife,sheepsorrel,elm,cherry,andoak.

3FromDahlbergandGuettinger(1956).DataforNovemberwereobtainedbyexamining387rumensfromdeerkilledbyhuntersinnorthernWisconsinin1943., Fiftyplantspecies,inadditiontothoselistedin table11,werelistedbyDahlbergandGuettingerascontributingtraceamountsto thediet.

'18

Table 12._Plants eaten by white-tailed deer in northern Minnesota in December

(In estimated percentages of the diet as determined through examination of feeding sites) _

Forestedfeedingsites BurnedfeedingsitesNortheast2 Northcentral3 Northeast4

Dogwood 44 16Redmaple 10 <1 40

Sweetfern 23BeakedandAmericanhazel 13 22Jackpine _ 2 19Mountainmaple 15 <1 2Blueberry ' 15Wintergreen 12

. Labradortea <1 9' Juneberry 7 6 2

Greenalder , 6Bunchberry 4Bush-honeysuckle 3 2Willow <1 3Quakingaspen 2 <1 <2Sedge 2Miscellaneous,plants 5

Numberof feedingsitesexamined 4 12 10Numberof -bitestallied 2,112 1,861 782

I _Plantswhoseusebydeerdidnotreach2percentinanyofthestudiesinDecemberincludedthistles,trailingarbutus,clubmoss,strawberry,honeysuckle,redt raspberry,balsampoplar,paperbirch,cherry,staghornsumac,rose,redoak,blackash,andwhitepine.

2FromWetzel(1972).Foradditionaldetailsofthatstudy,seefootnote3 oftable1.:3Mooty(unpublished).Foradditionaldetailsofthatstudy,seefootnote7, table7.

'i 4FromIrwin(1974).Foradditionaldetailsofthatstudy,seefootnote3, table6.

, COMMON AND SCIENTIFIC NAMES OF PLANTS, EATEN BY DEER IN THEi UPPER GREAT LAKES REGION|

I

, Commonname Scientific name Seasoneaten_' TREES:

Americanbeech FagusgrandifoliaAmericanelm UlmusamericanaAmericanlarchor tamarack Larixlaricinia

, Apple Pyrus spp. FAsh Fraxinusspp.Aspen Populusspp. Su, F,WBalsamfir Abiesbalsamea F,WBalsampoplar Popu/usba/samifera FBasswood Tiliaamericana W

19

Birch Betulaspp. F,WBitternuthickory CaryacordiformisBlackash Fraxinusnigra WBlackcherry Prunusserotina WBlackspruce PiceamarianaBluebeech CarpinuscarolinianaBox elder Acer negundoBur oak Quercusmacrocarpa W..

Butternut JuglanscinemaEasternhemlock Tsugacanadensis FElm Ulmusspp.Greenash Fraxinuspennsylvanica WHornbeamor Ironwood OstryavirginianaJack pine , Pinusbanksiana F,WLarge-toothedaspen Populusgrandidentata Su, W

. Maple Acer spp. Su, W' Mountain-ash Sorbusamericana W

Oak , Quercusspp. Su, WPaperbirch Betulapapyrifera Su, F,W

. Pine Pinusspp. F,W. Quakingaspen Populustremuloides Su, F' Redmaple Acer rubrum Su, F,W

Redoak QuercusrubraRedpine PinusresinosaSilver maple Acer saccharinum

, Sugarmaple Acer saccarumSwampbirch BetulapumilaWhite-cedar Thujaoccidentalis Sp, F,WWhite pine Pinusstrobus WWhite spruce PiceaglaucaWild crab PyrusangustifoliaYellowbirch Betulalutea

SHRUBSANDVINES;

Alder Alnus spp. Sp, F,WAlderleafbuckthorn Rhamnusalnifolia

, Alternate-leaveddogwood Comusaltemifolia W' , • • Americanhazel Corylusamericana Su, F,

" Arrowwood Viburnumspp., Beakedhazel Coryluscomuta Sp, Su, F,W

Bearberry Arctostaphylosuva-ursiBlackberryand raspberry Rubusspp. Su

, Black-haw Viburnumlentago. Blueberry Vacciniumspp. Sp, W

Bogbirch BetulapumilaBog laurel Kalmiapolifolia

.. Bog rosemary AndromedaglaucophyllaBuffaloberry Sheperdiaargentea

. Bush-honeysuckle OiervillaIonicera Sp, Su, F•- Canadianfly honeysuckle Loniceracanadensis

• Cherry Prunusspp. SuChokeberry Pyrusmelanocarpa WChokecherry Prunusvirginiana SuCommonelder Sambucuscanadensis

.

20

Creepingsnowberry Gaultheriahispidu/a" Currant Ribesspp.

- Swampcurrant Ribes/acustreDogwood Comusspp. Sp,Su, WDownyarrow-wood Viburnumrafinesquianum WEasternblackberry RubusallegheniensisElderberry Sambucusspp.Gooseberry Ribesspp.Graydogwood Comusracemosa WGreenbriar Smilaxspp.Greenalder Alnuscrispa Sp, W.Hairyhoneysuckle LonicerahirsutaHardback SpiraeatomentosaHawthorn , Crataegusspp.Hazel Corylusspp. Sp,Su,F,WHighbushblueberry . Vacciniumcorymbosum

, _ Highbushcranberry Viburnumtri/obum WHoneysuckle , Loniceraspp. SuJuneberry Amelanchierspp. Sp,Su, WJuniper Juniperusspp.

' Labradortea Ledumgroenlandicum F,WLatelowblueberry Vacciniumangustifolium SpLeatherleaf ChamaedaphnecalyculataLeatherwoodor moosewood DircapalustrisLilac SyringavulgarisMeadowrose Rosablanda

' Meadowsweet Spiraealatifolia,S. albaMountain-holly NemopanthusmucronatusMountainmaple Acerspicatum Su, WNewJerseytea CeanothusamericanusNinebark PhysocarpusopulifoliusNorthernhollyor winterberry IlexverticillataNorthernyew TaxuscanadensisPincherry Prunuspennsylvanica SuPipsissewa ChimaphilaumbellataPoisonIvy RhusradicansPrairiewillow Salixhumilis

, Pricklyash Xanthoxylumamericanum. , Raspberry Rubusstrigosus Su

Red-berriedelder Sambucuspubens, Redosierdogwood Comusstolonifera Sp,Su,F,W

Red-panicledogwood ComusracemosaRose Rosaspp.

, Round-leaveddogwood Comusrugosa W' Smallcranberry Vacciniumoxycoccus

Smoothclimbinghoneysuckle LoniceradioicaSmoothsumac RhusglabraSnowberry Symphoricarposa/busSpeckledalder Alnusrugosa Sp, WSumac Rhusspp. WSwamphoneysuckle LoniceraoblongifoliaSweetfern Comptoniaperegrina W

, Sweetgale MyricagaleThimbleberry Rubusparviflorus

°

21

.Thornapple Crataegusspp." lrailing arbutus Epigearepens

Twinflower Linnaeaborealis-Velvetleafblueberry VacciniummyrtilloidesWild -grape Vitis ripariaWild plum PrunusamericanusWild raisin ViburnumcassinoidesWillow Salixspp. Sp, Su, F,W

' " Wintergreen Gaultheriaprocumbens F,W" Witch hazel Hamamelisvirginiana

-Woodbineor virginiacreeper Parthenocissusinserta

HERBACEOUSPLANTS:

Alfalfa ' MedicagosativaAmericanvetch Viciaamericana

. Arrowhead SagittarialatifoliaAster Aster spp. SuBarrenstrawberry , Waldsteiniafragaroides SuBedstraw Galiumspp.

. Blackmedic Medicagolupulina.- Blacksnakeroot Sariculamarilandica

Bladdercampion SilenecucubalusBladderwort Utriculariaspp.Bluebell MertensiapaniculataBristlysarsaparilla Araliahispida Su

, . Buckbean Menyanthestrifoliata SuBuckwheat Fagopyrumspp.Bunchberry Comuscanadensis FBur-reed Sparganiumspp.Clinton's lily ClintoniaborealisClover TrifoliumandMelilotus Su, F

• Commondandelion TaraxacumofficinaleCommongeranium GeraniumbicknelliiCommontwisted-stalk StreptopusroseusCompositefamily CompositaeCoontail CeratophyllumdemersumCorn Zeamays

.. ' Cowparsnip Heracleumlanatum• .- ' Dock Rumexspp.

- EarlySweetpea Lathyrusochroleucus Su' Falselily-of-the-valley Maianthemumcanadense

FalseSolomon'sseal SmilacinatrifoliaFilamentousalgae Spirogyraspp.

, Fireweed Epilobiumangustifolium SuFlat-topwhite aster Aster umbellatusForkingcatchfly Silenedichotoma

• Fringedbindweedor false buckwheat Polygonumcilinode Su.Garden.pea , PisumsativumGoldenrod Solidagospp. Sp, Su, F

• 6oldthread Coptisgroenlandica: 6oosefoot Chenopodiumspp.

Graminoids Gramineaeand CyperaceaeGrasses Gramineae Sp, Su, FHarebell Campanularotundifolia

!

I.

I

. Hawkweed Hieraciumspp.- Hedgebindweed Convolvulussepium. ,

Hempor marijuana CannabissativaHo_seweed ErigeroncanadensisIndianHemp ApocynumcannabinumKidneybean Phaseolusspp.Lady'sthumb Polygonumpersicaria

. Large-leafaster Aster macrophyllus Su, FLily family. Liliaceae Sp, SuLoosestrife Lysimachiaspp.

, Marshcinquefoil PotentillapalustrisMarshmarigold Calthapalustris SpMilkweed Asclepiasspp.

I _ _ Night-floweringcatchfly SilenenoctifloraNorthernSt. John's-wort Hypericumboreale

. _. Paletouch-me-not Impatienspallida' Pearlyeverlasting Anaphalismargaritaceae

Pigweed . Amaranthusspp., Pitcherplant Sarraceniapurpurea

, • Purplewatershield Braseniaschreberi.- Pyrola Pyrolaspp.

Ragweed Ambrosiaspp.Ribbonleafpondweed PotamogetonepihydrusRoughcinquefoil Potenti//anorvegica SuScarletcolumbine Aquilegiacanadensis

,- Sedges Cyperaceae, Sp, Su, FincludingCarexspp.

, Sheepsorrel Rumexacetosella ,Showysmartweed PolygonumamphibiumSmoothaster Aster laevisSolomon'sseal Polygonatumspp.

• Soybean Glycinemax• Spikerush Eleocharisspp.

Spottedjewelweed Impatienscapensis SuSpreadingdogbane Apocynumandrosaemifolium SuStrawberry Fragariaspp. SuSunflower Helianthusspp.

, . ' Sweetclover Melilotus spp.,. ' Sweetpea Lathyrusspp. Su

Sweetwater-parsnip Siumsauve' Thistle Cirsiumspp.

. Three-waysedge Oulichiumspp.Violet Violaspp. Su ;_

' " . Waterhorsetail Equisetumfluviatile' Watermilfoil Myriophyllumspp. Su

Wheat Triticumaestivum

, " Whiteclover TrifoliumrepensWild carrotor QueenAnne'slace OaucuscarotaWild lettuce Lactucacanadensis

• Wild rice , Zizaniaaquatica• Wild sarsaparilla Aralianudicaulis Su

Wild sweetpea Lasthyrusvenosus SuWoodanemone AnemonequinquefoliaYarrow Achilleamillifolium

Yellowbellwort Uvulariagrandiflora" Yellowtrout lily Erthroniumamericanum

. ,

FUNGI:

Bracketfungi Daedaliaspp.Lenzitesspp.Polyporusspp.

.. Schizophyllumspp.' Mushrooms- Su

LICHENS:

Oldman'sbeard Usneaspp.Arboreallichens2 . Main/yUsneaspp.and

Evemiaspp. W

FERNSANDFERNALLIES:

Brackenfern ' Pteridiumaquilinum Su, Clubmoss Lycopodiumspp.

• Grapefern Botrychiumspp.Shieldfern Dryopterisspp.Woodfern Dryopterisspp.Mosses UnidentifiedmossesPigeonwheatmoss Polytrichumspp.

t

1Seasonofuseisdesignatedonlyforthosespeciesfoundtocomprise5 percentormoreofthedietinatleastonestudyinthe givenseason.Sp = April-May,Su = June-September,F = October-November,W = December-March.

2Alectoriaspp.wasreportedaseateninonestudybutlaterwasfoundtobeamisidentificationofUsneaspp.andEverniaspp.lichens.

o

24

II_U.S. GOVERNMENTPRINTING OFFICE: 1981-767-167/3 REG.#6