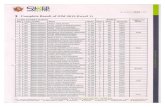

[first - 2] st/suntimes/page ... 25/12/16

Transcript of [first - 2] st/suntimes/page ... 25/12/16

![Page 1: [first - 2] st/suntimes/page ... 25/12/16](https://reader031.fdocuments.us/reader031/viewer/2022031317/5881f36a1a28ab0b1a8b80d4/html5/thumbnails/1.jpg)

In 2012, then education ministerHeng Swee Keat announced the vi-sion of Every School A Good School,as the ministry sought to quell anxie-ties among parents about whetherstudents are in “branded schools”or “neighbourhood schools”.

MOE also scrapped the banding ofsecondary schools, and stopped re-leasing information on top scorersfor national exams.

PSLE received a major overhaulthis year, with the T-score to be re-placed by scoring bands in 2021.

The report’s recommendationsformed the basis of the New Educa-tion System, implemented in 1980.Students were put into streamswhen they joined Primary 4, andagain in secondary school.

The Special Assistance Plan wasimplemented in nine secondaryschools, while the Gifted Educa-tion Programme started in 1984.

In 1987, a major policy changetook place. Schools were givengreater autonomy with the estab-lishment of independent schools.Teachers were given more flexibili-ty to respond to students with vary-ing ability.

By 1987, English was taught as afirst language in Singaporeschools.

Yuen Sin

When housewife Hua Yingying wasa student, she was taught the basicconcepts of maths and sciencefrom textbooks in school, and didnot have much homework.

“We also didn’t have things likehands-on learning or project work.Now, even children in kindergartenor primary school are taught how touse basic software and work onprojects,” said the 45-year-old, whohas a daughter in Secondary 2.

And while many students tendedto opt for traditional fields such asengineering or accounting in thepast, it has now become harder topredict what jobs will be in demand.

Madam Hua wants her daughterto explore her interests and findher passion. She thus cheered thenews that Singapore had taken thetop spot in the Pisa rankings, an in-ternational benchmarking testwhich places emphasis on high-er-order critical thinking skills.

The results show the local educa-tion system has managed to equipstudents with such skills, she said.

“These skills are important for do-

ing well in the global economy be-cause children will need to learnhow to adapt to changes quicklyand cope with unforeseen circum-stances,” she said.

Other parents question the rele-vance of the Programme for Inter-national Student Assessment rank-ings, and say the education systemhas to evolve further beyond im-parting knowledge.

Mr Eugene Seah, 40, agrees thatthe role of parenting and educationhas evolved as Singapore’s econom-ic needs change over time. “Weknow for sure that what worked forus in the past would not work in thesame way now,” he said.

The speaker-trainer learnt thatlesson the hard way – in 2013, hewas retrenched after 14 years ofworking in public relations and mar-keting in the financial industry.

The father of three children agedbetween six and 12 questions the rel-evance of the Pisa rankings. Afterall, the giants of the future economy– Facebook, Google and Uber – wereall founded in the United States,which ranked 25th in the Pisa test.

“Do we want to end up workingfor other people, or be the ones creat-

ing the next big company?” he said.While he acknowledged that

schools are placing more emphasison critical thinking and inquiry, hethinks there should be a much big-ger shift away from teaching know-ledge towards independent think-ing, as Singapore still lacks talent increativity and innovation.

While the Pisa test takes criticalthinking into account, there are al-so plans to measure how well stu-dents perform in areas such as in-ter-cultural sensitivity in 2018.

However, creative business con-sultant Calvin Soh, who has a10-year-old daughter and a 14-year-old son, thinks the Pisa rankingsare evolving too slowly and cannotcatch up with the exponential paceat which technology is developing.

While the Pisa rankings measureone’s ability to think critically, theydo not measure qualities such asself-confidence and one’s ability torecover from failure – key traitsneeded in a successful entrepre-neur, he said.

His son Dylan, who will be inSecondary 3 next year, has failedexams at Anglo-Chinese School(Barker Road).

However, Mr Soh, 49, said thathas not affected Dylan’s self-es-teem, as he encourages his son’snon-academic pursuits.

At One Kind House, a communityspace with an urban farm that MrSoh designed and set up in TelokKurau this year, Dylan works on hisown projects, such as designing andprototyping urban farming tools.

“Often, they don’t work out ini-tially, but he has learnt to try andtry again until he succeeds,” saidMr Soh.

Some schools, such as Spectra Sec-ondary, have similar projects.Through a gardening programmethat is part of its Character and Citi-zenship Education curriculum, stu-dents learn about values such as re-silience and respect for nature.

But Mr Soh says academicachievement is still prioritised overhands-on projects.

He reckons the overemphasis onthe former creates a culture wherefailure is stigmatised in Singapore,holding it back from having arisk-taking culture that embracesinnovation. This is despite thecountry doing well in academicbenchmarking tests.

“Though we see gardening as alow economic skill set, it teaches usthings about the variability of na-ture, and understanding and re-specting nature so that you see theconsequences of your actions. Butis this more important than scoringAs and Bs in science at the mo-ment? It is not.”

Amelia Teng

In a class last month, Primary 5 pu-pils at Woodgrove Primary Schoolmulled over a mathematical puzzleunlike any standard problem sum.

The puzzle read: “Take anytwo-digit number, reverse the digitsand subtract the smaller numberfrom the larger number – what canyou say about the results?”

“Try as many numbers as youlike on a piece of paper,” said theirmathematics teacher, Ms Lin Cai-li, 34, as she prompted pupils totest their hypotheses and explaintheir guesses.

“The answer is always a multipleof three,” one boy concluded.

“Maybe it’s a multiple of nine,”said another.

Ms Tan Hong Kai, 34, the school’slevel head of mathematics, said theclass was doing an investigativetask on number patterns. Theseopen-ended activities, which shesaid are not usually tested in exami-nations, have been woven into les-sons to equip pupils with higher-or-der thinking skills.

Such efforts by schools to en-courage active learning haveborne fruit, with Singapore stu-dents topping a global benchmark-ing test that measures how wellthey apply knowledge to solvingreal-world problems.

Earlier this month, 15-year-oldsin Singapore were ranked No. 1in maths, science and reading inthe 2015 Programme for Interna-tional Student Assessment (Pisa)test, dubbed the “World Cup foreducation”.

Last month, Singapore childrenin Primary 4 and Secondary 2 alsotopped another global mathemat-ics and science test – Trends in In-ternational Mathematics and Sci-ence Study (Timss).

These results have placed Singa-pore on the world map and sparkeddiscussion in media worldwideabout the merits and flaws of theRepublic’s education system.

Dr Kho Tek Hong, a former curric-ulum specialist who led a team inthe 1980s to raise maths standards,said these results reflect the per-formance of Singapore as a country,not individual abilities, an indica-tion that students from different ac-ademic streams were represented.

Science was the major domaintested in Pisa 2015, and the resultsshowed teens here were strong inscientific enquiry skills and coulduse evidence to support claims.

An Education Ministry (MOE)spokesman attributed Singapore’ssuccess in global studies to a teach-ing and learning culture which hasbuilt a “strong foundation in read-ing, numeracy and scientific litera-cy for all students”.

It also develops their thinkingand communication skills, exposesthem to application of knowledgein real-life contexts across subjectsand gives them “positive attitudestowards learning”, he said.

Education experts point toSingapore’s ability to refresh its

school curriculum and level up itsteachers as key factors behind stu-dents consistently topping globalrankings since the 1990s.

National Institute of Education(NIE) don Jason Tan, 53, noted thatSingapore has managed to attain ahigh average achievement levelcompared with other countries inthe region.

“This is helped by a rather central-ised administration which canpush reforms quickly from head-quarters down to schools,” he said.“Another plus point is the continui-ty in government, so there has notbeen much policy reversal.”

He also pointed to schools herehaving the resources to developteachers, and physical infrastruc-ture such as labs for learning.

CURRICULUM SHIFTSDr Kho, 70, said that Singapore’sjourney to where it is today startedwith an overhaul of education inthe 1980s to raise standards.

“The New Education system, as itwas called, changed everythingfrom school curriculum to teachingmethods,” he said. For instance,the former Curriculum Develop-ment Institute of Singapore was setup in 1980 to develop good-qualityteaching and learning materials.

In those years, Singapore alsolooked to education systems incountries such as Israel and Japan,and studied how it could learn fromvarious psychological theories.

“That was the start of slowly mov-ing away from traditional rotelearning and passive memorisingover the next 30 years,” said DrKho. “When students explore andare more active in learning, theymake sense of concepts better.”

Since about a decade ago, theMOE has also made an effort to cutcontent across subjects, to makeroom for students to learn high-er-order thinking skills such as logi-cal reasoning and problem-solving.

This was done to free up time inschools for teachers to be more flex-ible and help students learn creativ-ity instead of just content.

Dr Yeap Ban Har, 48, principal ofMarshall Cavendish Institute,which conducts professional devel-opment courses for teachers, saidthere is a “clear direction” acrossthe system today to train studentsto develop deeper inquiry skills.

For instance, since the 1997 visionof “Thinking Schools, Learning Na-tion”, curricula and assessmenthave focused more on critical think-ing skills and creativity, he said.

Increasingly, national examina-tions are also testing more applica-tion-based questions in novel sce-narios, said Dr Yeap, who spent 10years at NIE’s mathematics andmathematics education academicgroup from 1999 to 2010.

Twelve-year-old Gary Gan, whofinished Primary 6 this year, said“higher-level” mathematics ques-tions can be frustrating but he en-joys them as they help him thinkmore. “Maths helps me learn tosolve problems and I think this willhelp me in the future to solve more

challenging problems,” he said.Dr Ridzuan Abd Rahim, an MOE

lead curriculum specialist in mathe-matics, said: “It is no longer enoughthat we just know something. Moreimportantly, we need to know howto learn something new and how toapply what we know to new situa-tions and problems.”

Today’s society and economy re-quire workers to take ownership,be adaptive, and adapt ambiguityand complexity as the norm, saidCHIJ Katong Convent principal Pa-tricia Chan.

That is why curriculum has toevolve from one totally focused oncontent, to equip students withsuch skills for the future, she said.

In response to these rapidlychanging needs, science and human-ities subjects have been refreshed toequip students with skills for the fu-ture such as teamwork and the abili-ty to analyse, be creative, make linksand solve problems.

Lessons are now more groundedin real-life contexts, requiring stu-dents to apply textbook theoriesoutside the classroom.

For instance, Ms Chan said stu-dents would learn about the totalsurface area of a cylindrical contain-er in relation to understanding whyand how manufacturers minimisematerial cost when canning drinks.

“In the humanities, the move to-wards the inquiry approach posi-tions itself away from typical rotelearning, where one can score byjust memorising,” she added.

Students now need to make linksbetween concepts and draw theirown conclusions, using investiga-tive work and examples from cur-rent affairs in the process, she said.

Pupils are also encouraged tospeak up more so they are able toexpress themselves confidently.

A national curriculum called Stel-lar, short for Strategies for EnglishLanguage Learning and Reading,was piloted in some schools in 2006with the aim of developing pupils’

ability to use the English languageconfidently in real-world scenarios.

Stellar, which does not rely ontextbooks and instead uses storytell-ing, role-playing and texts such asnews articles in lessons, was extend-

ed to all primary schools in 2009.Schools also pay more attention

to developing students beyondbook smarts through applied learn-ing in topics such as robotics, foodscience or transport.

These programmes, said Dr Rid-zuan, give students a chance to ex-periment and take on hands-on ac-tivities that apply to the real world.

TEACHER TRAININGThe other plank of Singapore’sglobal success lies in teacher train-ing. Experts said NIE and its prede-cessors have played a key role intraining educators centrally overthe years.

NIE director Tan Oon Seng saidits partnership with schools andMOE ensures that teacher educa-tion is in line with “larger teacherpolicies, Singapore’s education pri-orities and aspirations, and theground challenges in schools”.

For instance, to teach studentshigher-order thinking, teachersthemselves must be equipped to“ask questions, to guide and facili-tate students to think... beyond in-formation or knowledge impart-ing”, said former NIE director LeeSing Kong.

Professor Low Ee Ling, head ofNIE’s strategic planning and aca-demic quality, said having a cen-tral body that trains teachers iswhat makes Singapore “a veryunique system”.

This model began with the set-ting up of the Teacher Training Col-lege in 1950.

Before that, many teachers hadlittle or no prior formal teachertraining, leading to uneven qualityof teaching standards acrossschools, she said. Today, around 85per cent of teachers are graduates,and at the primary school level, sev-en in 10 teachers have a degree.

NIE trainee teachers, calledpre-service teachers, also go onpractice stints in schools to helpthem link theory to practice.

The MOE has also been improv-ing pay and promotion prospectsfor teachers. For example, in Octo-ber last year, up to 30,000 teachersreceived a 4 per cent to 9 per centincrease in their monthly pay.

Mentorship schemes introducedsince 2006 have also helped newteachers hone their craft on the job.

Each beginning teacher ismatched to a mentor in school whoprovides guidance in areas such asclassroom management, basic coun-selling skills and assessment skills.

St Stephen’s School teacher GionPee is grateful that the system em-phasises beginning teachers’ pro-fessional growth. The 33-year-old,who joined teaching in July 2012,had a one-year induction where helearnt teaching and managementskills from senior teachers.

Since January this year, he has re-ceived tips on teaching English dur-ing weekly meetings with his men-tor, Madam Azizah A. Rasak. Thesessions helped him to reflect onhow to differentiate his teachingstyle to suit his pupils’ learningneeds, he said.

Dr Charles Chew, principal mas-ter teacher in physics at the Acade-my of Singapore Teachers, said:“Teaching is a highly complex craftthat needs to be constantly sharp-ened and honed to meet the needsof students... A good teacher is onewho does not teach the subject butteaches students the subject.”

Last month, National Universityof Singapore economics lecturerKelvin Seah analysed survey datafrom the Programme for Interna-tional Student Assessment (Pisa)in 2012 and made a surprisingfinding: Students who had tui-tion fared worse than those whodid not.

Dr Seah, 34, said he came to twoconclusions: “Either these stu-dents were receiving tuition be-cause they were weaker in thefirst place or they did worse be-cause of tuition. That means tui-tion and having too many lessonsmight be counter-productive.”

Education experts said it is dif-ficult to establish how much of arole tuition has in academic suc-cess or if it has contributed toSingapore’s stellar showing in Pi-sa, a global benchmarking testwhich 15-year-olds here toppedlast year.

But what is beyond dispute isthe growth of the shadow educa-tion industry. Tuition is worthmore than a billion dollars annu-ally here, almost double the $650million spent on it in 2004.

Some parents spend severalhundreds or thousands of dollarson tuition each month, despiteknowing that having tuition maynot raise their children’s gradessignificantly.

This stems from a strong com-mitment to education in Singapo-rean families – doing well at na-tional examinations is a priorityfor many parents and students.

Dr Yeap Ban Har, 48, principalof Marshall Cavendish Institute,which conducts professional de-velopment courses for teachers,reckoned tutoring helps in mas-tering the basics, but does notcontribute significantly to per-forming well in novel, challeng-ing problems.

“If a student is weak in basics,tuition might help with basicskills questions as it tends to beabout practice and more prac-tice,” he said. “But it may not helpwith challenging, novel ones, likethose found in the Pisa exercise.”

National Institute of Educationdon Jason Tan said the efficacy oftuition varies from student to stu-dent. “I don’t think you can say tu-ition does not work for anyone.”

Experts said tuition will existas long as there are high-stakesnational examinations.

Dr Seah said tuition should notbe lightly dismissed. “For stu-dents whose families can affordbetter-quality tuition and enrich-ment, it could be a big part ofwhy they continue to do well.”

Dr Yeap said the skills of ateacher make more of a differ-ence in a student’s learning pro-cess. “It is not a case of tuition orno tuition... If a teacher can cre-ate opportunities (for students)to explore, to collaborate, tothink structurally, to reflect, tocommunicate, to be independ-ent, to make meaning, to beconfident… It does not matterwhether he is a teacher in aschool, or a tutor.”

Amelia Teng

The education system over the years

Topping the rankings

Shift to higher-order thinking, central body forteacher training help kids in problem-solving

Primary 5 pupils at Woodgrove Primary School offering solutions to a mathematical puzzle. Such open-ended activitieshave been woven into lessons to equip pupils with higher-order thinking skills. ST PHOTO: MARK CHEONG

There was a push to develop inno-vation and technology use inschools during this period, withthe launch of a masterplan for IT ineducation in 1997.

A new vision – Thinking Schools,Learning Nation – was launchedthat same year.

It aimed to do away with theEducation Ministry’s (MOE’s)

top-down approach by groupingschools in clusters and encourag-ing them to share best practicesand ideas, as well as nurture crea-tive thinking and lifelong learning.

Curriculum content was cut by30 per cent across the boardand every teacher received atleast 100 hours of training a yearby 2000.

As Singapore went through decolo-nisation, it quickly expanded the ed-ucation programme. Primary andsecondary schools were built, andenrolment in secondary schools al-

most doubled from 1965 to 1970.The basic curriculum was devel-

oped and the Primary SchoolLeaving Examination (PSLE) wasstarted.

The 6-4-2 education system (sixyears of primary, four years of sec-ondary and two years of pre-uni-versity education) was developed.

All schools followed a commoncurriculum, and students tookthree common exams: the PSLE,and O and A levels.

But failure rates were high then.In 1976, 41 per cent of PSLE candi-

dates and 40 per cent of O-levelcandidates failed their exams.

In 1978, a study team found thathigh attrition rate, low literacy lev-els and ineffective bilingualismwere the main problems facing theeducation system. A report by theteam pointed to the rigid educa-tion system as the main reason be-hind these problems.

2010 and beyond: Every School A Good School1980s: Ability-driven phase

Topping the rankings

2000s: Teach Less, Learn More

Mr Calvin Soh with his son Dylan and daughter Ava. Mr Soh thinks the Pisa rankings are evolving too slowly and cannot catch up with the exponential pace at which technology is developing. He has set upOne Kind House, a community space with an urban farm, where Dylan works on his own projects, such as designing and prototyping urban farming tools. ST PHOTO: ARIFFIN JAMAR

Radin Mas Primary School pupils, who designed a webpage on the zoo in 1999.In the 1990s, there was a push to use IT in schools.

Nanyang Primary School pupils at a skipping event in 2005. During the 2000s,specialist schools, such as the Singapore Sports School, were opened.

Pupils at the Dinosaurs: Dawn To Extinction exhibition held at the ArtScienceMuseum in 2014. They were part of The Straits Times Young Storymakers’ Camp.

The education system over the years

NIE’s Prof Tan (left) says its partnership with schools and MOE ensures thatteacher education is in line with larger policies. Prof Low says having a centralbody that trains teachers makes Singapore “unique”. ST PHOTO: ONG WEE JIN

Primary 4 pupils (from left) Tan Hai Yang, Vasudevan Suresh Megna, Ellyse Wongand Bryan Pak with some of the storybooks used in class for Woodgrove PrimarySchool’s literature-based approach to maths. ST PHOTO: MARK CHEONG

How S’pore’s students rose to No. 1

Greater flexibility was introduced,and the vision of Teach Less, LearnMore launched in 2004.

It called for educators to teachbetter, engage students and pre-pare them for life, instead of teach-ing for examinations.

That same year, the EM1 andEM2 streams were merged. TheEM3 stream for academically

weaker students was scrapped in2008. The Integrated Programmeand Direct School AdmissionsScheme were introduced.

Polytechnics could select stu-dents with special talents andachievements. During this decade,specialist schools such as the Singa-pore Sports School and the Schoolof the Arts were opened.

Winners of an Eat More Wheat cooking competition in 1968 held at Raffles Girls’School. ST FILE PHOTOS

1960s: Survival-driven phase 1970s: Efficiency-driven phase 1990s: Thinking Schools, Learning Nation

Students of River Valley Secondary School drinking milk in 1974, part of asubsidised scheme by the Education Ministry for about 27,000 students.

Parents ponder valueof Pisa test rankings

Local literature was taught to students in the 1980s as Singaporeans canrelate better to the things that local authors write about.

Tuitionindustryworth over$1b a year

OVEREMPHASIS ON RESULTS

Though weseegardeningas a loweconomicskill set, itteaches us thingsabout the variabilityof nature, andunderstandingandrespectingnatureso that you see theconsequencesof youractions. But is thismore important thanscoring As and Bs inscience at themoment? It is not.

’’MR CALVINSOH, whohas a 10-year-olddaughter and a 14-year-old son,on howacademic achievement is still beingprioritised over hands-on projects.

B2 | Insight The Sunday Times | Sunday, December 25, 2016 Sunday, December 25, 2016 | The Sunday Times Insight | B3

![[FIRST - 2] ST/SUNTIMES/PAGE …/media/gov/files/media/20140921_jointgovt... · dim view of solicitors who ... the sec-ond-highest annual figure on record. Lawyer](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/5b6495bf7f8b9af5448d81e0/first-2-stsuntimespage-mediagovfilesmedia20140921jointgovt-dim.jpg)