Fall 2009

-

Upload

sanford-burnham-prebys-medical-discovery-institute -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Fall 2009

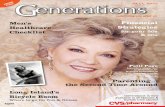

VOLUME 6 NUMBER 3 | FALL 2009

From Research, The Power to Cure

InsIde >DiABEtEs REsEARch >BURNhAM NEws >PhiL ANthROPy

the Questto Cure Diabetes

B U r n h a m R E P O R t

i N t h i s i s s U E

B U R N h A M R E s E A R c h

The Quest to Cure Diabetes 1

Diabetes and its Consequences 3

A National Quest 5

B U R N h A M N E w s

The View from Lake Nona 7

Science News 8

New Faculty 11

Collaborations 13

P h i L A N t h R O P y

Burnham Welcomes Julie Johnson 14

Lake Nona Events 15

La Jolla Events 16

A R O U N D B U R N h A M

President’s Message 17

Partners in Science 18

BL AiR BLUM Senior Vice President External Relations

ELizABEth GiANiNi Vice President External Relations

EDGAR GiLLENwAtERs Vice President External Relations

chRis LEE Vice President External Relations

ANDREA MOsER Vice President Communications

O N t h E c O V E R

Drs. Timothy Osborne,

Stephen Gardell

and Daniel Kelly are

committed to finding

new ways to treat type

2 diabetes and related

diseases. As director of

the Metabolic Signaling

and Disease Program,

Dr. Osborne wants to

illuminate the normal signaling mechanisms that control

metabolism and how those signals differ in diseased tissue.

Dr. Steve Gardell directs Translational Research Resources,

which seeks to move basic research findings from the labo-

ratory to the clinic. Scientific Director Dr. Daniel Kelly

investigates cardiovascular disease and wants to expose its

different causes and discover new treatments.

Burnham Institute for Medical Research10901 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037 • 858.646.3100

Burnham Institute for Medical Research at Lake Nona 6400 Sanger Road, Orlando, FL 32827 • 407.745.2000

Founders

wiLLiAM h. F ishMAN, Ph.D. L iLLiAN FishMAN

honorary trustees

JOE LEwis cONRAD t. PREBys t. DENNy sANFORD

trustees and Officers

MALiN BURNhAM Chairman

JOhN c. REED, M.D. , Ph.D. President & Chief Executive Officer Professor and Donald Bren Presidential Chair

GARy F. RAisL, ED.D. Chief Administrative Officer Treasurer

MARGAREt M. DUNBAR Secretary

trustees

Linden S. BlueMary BradleyBrigitte BrenArthur BrodyMalin BurnhamHoward I. CohenShehan Dissanayake, Ph.D.M. Wainwright Fishburn, Jr.Jeannie M. Fontana, M.D., Ph.D.

Trustees, continued

Alan GleicherW.D. GrantDavid HaleJeanne Herberger, Ph.D.Brent JacobsJames E. Jardon II (Florida)Daniel P. Kelly, M.D.Robert J. LauerSheila B. LipinskyGregory T. LucierPapa Doug ManchesterRobert A. Mandell (Florida)Nicolas C. NierenbergDouglas H. ObenshainPeter PreussJohn C. Reed, M.D., Ph.D.Stuart TanzJan Tuttleman, Ph.D., MBAAndrew J. Viterbi, Ph.D.Kristiina Vuori, M.D., Ph.D.Bobbi WarrenAllen R. Weiss (Florida)Judy WhiteGayle E. WilsonDiane WinokurKenneth J. Woolcott

Ex-Officio

Raymond L. White, Ph.D.Chairman, Science Advisory Committee

JOsh BAxt Editor, Burnham Report

GAViN & GAViN ADVERtisiNG Design

MichAEL cAiRNsMARk DAstRUPNADiA BOROwski scOtt Photography

kEN G. cOVENEy, Esq.FABiAN V. F iL iPP, Ph.D.Contributors

Please address inquiries to: [email protected]

www.burnham.org

B U r n h a m D i A B E t E s R E s E A R c h

www.burnham.org | The BUrnham reporT 1

the Questto Cure Diabetes

Pancreatic beta cells – photo by Ifat Geron, Levine and Itkin-Ansari laboratories

In 1922, insulin was first administered to treat type 1 diabetes, trans-forming a deadly disease into a chronic one. But insulin is not a cure.

Periodic blood sugar moni-

toring and insulin injections

cannot match the 24/7 effi-

ciency of insulin-producing

beta cells. According to the

Juvenile Diabetes Research

Foundation, type 1 diabetes

reduces lifespan, on average,

by seven to 10 years.

Type 2 diabetes—a quite

different disease—is associ-

ated with obesity and is fast

becoming an epidemic in the

United States. While type 1

results from a lack of insulin,

type 2 appears when cells

lose the ability to respond

to insulin (See box, page 3).

According to the American

Diabetes Association, more

than 23 million people have

diabetes, mostly type 2.

Though treatments for

both forms of diabetes have

advanced, cures remain

elusive. At Burnham, signifi-

cant work is being done on

both coasts to understand

these conditions and find new

treatments.

MAkiNG NEw iNsULiN-PRODUciNG cELLs

Both type I and type II

diabetes are caused by a

deficiency of the cells that

produce insulin. Type 1 is an

autoimmune disorder, in which

the body’s immune system

attacks and destroys beta cells,

which monitor blood glucose

and release insulin. In type 2

diabetes, high levels of fatty

acids attack beta cells. As beta

cells die, glucose accumulates

in the blood, leading to deadly

complications. However, if

we could transplant or renew

beta cells, the body could once

again produce its own insulin.

Currently, beta cells are

transplanted from cadavers

but quantities are very low.

Fred Levine, M.D., Ph.D.,

directs the Sanford Children’s

Health Research Center

and is trying to solve the

problem of making new beta

cells—either outside the body

for transplantation or by acti-

vating adult stem cells within

the pancreas.

“Our initial intent was to

make a cell line that would

mimic beta cells so well they

could be transplanted,” says Dr.

Levine. “While that goal proved

overly ambitious, the cells that

we made turned out to be ideal

for high-throughput screening

to search for drugs that affect

beta cells. This project, done

in collaboration with Burnham

investigators Drs. Mark

Mercola, Pamela Itkin-Ansari

and Jeff Price, as well as the

Conrad Prebys Center for

Chemical Genomics, has

been a long road but has

recently borne fruit, with

a number of compounds

entering preclinical trials.”

In addition to the studies

with high-throughput

screening, Dr. Levine’s labora-

tory is also pursuing other

avenues. What if adult stem

cells, or mature endocrine

cells, could be transformed

into beta cells? Dr. Levine is

collaborating with Burnham

stem cell scientists, such as Dr.

Alexey Terskikh, to understand

the genes that induce adult

stem cells in the pancreas to

become functioning beta cells.

POssiBiLit iEs iN REGENERAtiON

Like Dr. Levine, Duc Dong,

Ph.D., is trying to regenerate

beta cells from cells that

already exist in our bodies.

“Usually in diabetes there

are a few beta cells left,”

says Dr. Dong. “How can

we replenish them? If we

understand the developmental

biology, we may find thera-

peutic targets where you add a

drug or apply gene therapy to

encourage the body to regen-

erate the cells.”

The Dong laboratory,

which uses zebrafish as a

research model, is also trying

to encourage pancreatic

exocrine cells, which produce

digestive enzymes, to become

beta cells.

“They come from the same

precursors,” says Dr. Dong.

“We found that a particular

gene helps decide the fate of

these precursors. We hope

that, by manipulating this

gene, we can help make more

beta cells.”

Taking a different

approach, Alex Strongin,

Ph.D., is interested in what

happens if the immune

system can be selectively

blocked. Dr. Strongin studies

an enzyme that helps inva-

sive cancer cells migrate to

other parts of the body. The

enzyme, called MT1-MMP,

is a proteinase, a protein

that cuts up other proteins.

MT1-MMP interacts with a

cell surface receptor called

CD44, which plays a number

of roles in cancer cells and

autoimmune T cells—the

culprits in beta cell destruc-

tion. Dr. Strongin has found

that inhibiting MT1-MMP

keeps T cells out of the

pancreas.

“We found that if you stop

the killer cells from getting

into the pancreas, it gives beta

B U r n h a m D i A B E t E s R E s E A R c h

2 The BUrnham reporT | www.burnham.org

Dr. Fred Levine chats with postdoctoral fellow Dr. Seung-Hee Lee

Dr. Levine is collaborating with

Burnham stem cell scientists, such as Dr. Alexey

Terskikh, to understand the genes that induce adult stem cells in the pancreas to

become functioning beta cells.

cells the opportunity to regen-

erate,” says Dr. Strongin.

The tricky part is finding

the right inhibitor. Dr. Strongin

notes that an MT1-MMP

inhibitor has failed in clinical

trials for late-stage cancer. To

be useful, the compound must

be minimally toxic.

“We would have to develop

a less toxic inhibitor because

patients would be taking it for

the rest of their lives,” says

Dr. Strongin. “It’s one thing

to have a toxic treatment for

cancer and another entirely

for diabetes, where insulin

is an effective treatment. So,

there’s still a great deal of

work to be done.”

PROtEctiNG cELLs FROM thE iMMUNE systEM

For transplantation to be a

viable treatment, the immune

system must be controlled.

Current transplant recipients

must take immunosuppres-

sive drugs to prevent their T

cells from attacking replace-

ment beta cells, presenting a

stark choice between diabetes

and a suppressed immune

system.

Recently, Burnham

adjunct professor Pamela

Itkin-Ansari, Ph.D., placed

pancreatic precursor cells

in an immunoprotective

device and transplanted them

into mice. She was testing

whether precursor cells would

mature into productive beta

cells in the body and whether

the protective device, made

from a material akin to

Gore-Tex, could prevent

the immune system from

attacking transplanted cells.

“We wanted to see if we

could protect the cells from

the immune system rather

than suppressing the immune

system,” says Dr. Itkin-Ansari.

Early studies have been

very positive, as the trans-

planted cells responded to

glucose and produced insulin

and the immunoprotective

device kept the immune

system at bay.

“We are excited to see

how well they did,” says Dr.

B U r n h a m D i A B E t E s R E s E A R c h

www.burnham.org | The BUrnham reporT 3 www.burnham.org | The BUrnham reporT 3

Insulin is produced in the

pancreas by beta cells, which

measure glucose (the main

source of energy from food)

in the blood and secrete

insulin to control glucose

concentrations. Insulin acts

as a key, binding to recep-

tors (locks) expressed by all

cells and telling them to let

glucose inside.

In type 1 diabetes, beta

cells are destroyed by the

body’s own immune system.

White blood cells that

ordinarily protect us from

bacteria and viruses mistak-

enly recognize beta cells as

foreign and destroy them,

reducing or eliminating

insulin production.

In type 2 diabetes, the

problem is with the insulin

receptor—the lock that

allows glucose to enter. For

reasons that are not clear,

the receptor mechanism

does not work properly,

even when insulin is

present. The body responds

by producing more insulin.

While that works for a

time, it overworks the beta

cells, which ultimately fail

and die.

High circulating glucose

levels damage cells. Because

glucose moves primarily

through blood, the cells

lining blood vessels are the

most severely hurt. These

consequences extend to

virtually every organ in the

body. Diabetes is a leading

cause of blindness, kidney

disease, amputation, heart

disease and many other

conditions.

Diabetes and its

Consequences

Dr. Duc Dong in the zebrafish facility

Itkin-Ansari. “We could

see evidence of beta cells

forming and replicating. That

means the environment in

the device was conducive

to beta cells continuing

to develop and survive.

Also, we thought that T

cells, although unable to

penetrate the device, would

cluster around it. But we

found no evidence of an

active immune response,

suggesting that the cells in

the device were invisible to

the immune system.”

thE PROBLEM with FAt

At Burnham’s Orlando,

Florida campus, researchers

are focused on the underlying

mechanisms behind type 2

diabetes, in which insulin

levels are normal (or elevated)

but cells do not respond to

its signals. Scientists want to

know why insulin resistance

happens in the first place,

how diabetes affects the

heart and the role fat plays in

diabetes, metabolic syndrome

and other conditions.

Philip A. Wood, D.V.M.,

Ph.D., is interested in fat: fat

metabolism, fatty acids, fat

signaling, fatty liver disease.

Dr. Wood is trying to unravel the

consequences of too much fat.

“I’m interested in how the

body reacts to excess fat and

how fat metabolism and the

genetics of fat metabolism

play a role in insulin resis-

tance and fatty liver disease,”

says Dr. Wood.

Given that recent statis-

tics show a third of Americans

are obese, the research being

done by Dr. Wood and others

could have a profound impact

on the nation’s health. One

key focus is the underlying

genetics that make certain

people susceptible to disease.

“We’re not likely to find

specific genes that cause

type 2 diabetes,” says Dr.

Wood. “Perhaps they exist in

rare cases, but not enough

for a genetic risk assess-

ment. We’re not looking for

the cause of the disease;

we’re looking at the genetic

and environmental determi-

nants of the body’s response

to this burden of excess fat.

Why do some people have

a predisposition towards

insulin resistance in the face

of obesity? So we’re looking at

the genetics of response, not

the genetics of cause.”

On a practical level, Dr.

Wood is particularly concerned

with visceral fat, the extra

baggage we may have hanging

over our belts in front.

“Excessive abdominal

fat is linked to higher blood

pressure and triglycerides

and makes that person a

candidate for heart attack,

diabetes, or both,” says Dr.

Wood. “Visceral fat tissue

leaks fatty acids, which go

to the liver and cause fatty

liver disease, enter the

blood as triglycerides and

also cause inflammation.

The most disturbing part is

that today’s children may be

the first in history to have a

shorter lifespan than their

parents because of obesity-

related diseases.”

While Dr. Wood is

focused on what goes

wrong for people with type

2 diabetes, Tim Osborne,

Ph.D., wants to understand

the processes that make the

metabolism run normally.

“There’s a lot of synergy

between Dr. Wood’s

research and mine,” says

Dr. Osborne. “He comes

at it from the disease side,

and we’re interested in

identifying the pathways

that occur normally. If we

can understand the normal

processes and how they go

awry, it will help us find

ways to reverse or alleviate

B U r n h a m D i A B E t E s R E s E A R c h

4 The BUrnham reporT | www.burnham.org

Dr. Philip Wood

The most disturbing part is thattoday’s children may be the first in history to have a shorter lifespan than their parents because of obesity-related diseases.

B U r n h a m D i A B E t E s R E s E A R c h

www.burnham.org | The BUrnham reporT 5

Burnham is committed to uncovering the underlying

mechanisms behind diabetes and finding new ways to treat

it. But the Institute is not alone. Burnham has numerous

collaborations, large and small, with organizations around

the country that share our desire to beat diabetes. In partic-

ular, Sanford Health and the Juvenile Diabetes Research

Foundation (JDRF) are working with Burnham to cure type 1

diabetes.

Paul Burn, Ph.D., is professor of Pediatrics at the

Sanford School of Medicine of the University of South

Dakota and the Broin Chair and director of the Sanford

Project, a venture sponsored by Sanford Health that seeks

to develop new therapies for type 1 diabetes as quickly as

possible. Dr. Burn notes that the collaboration between

Burnham and the Sanford Project bridges the gap between

basic and clinical research.

“The capabilities of Burnham and Sanford nicely

complement each other,” says Dr. Burn. “Burnham’s

strengths lie in the early phases of discovery, while Sanford

is more focused on the translational aspects of diabetes.

Together, we cover the space from the gene, to novel drug

targets, screens and clinical candidate molecules, followed

by proof of concept studies in animals and humans. These

are all aimed at delivering innovative cures for diabetes to

the patient.”

Both the Sanford Project and Burnham partner with

JDRF to accelerate the research. Alan Lewis, Ph.D., is

President and CEO of JDRF, which has funded diabetes

research at Burnham for many years. JDRF supports research

into new treatments, as well as new devices.

JDRF is also working to help talented researchers, such

as Drs. Fred Levine and Pam Itkin-Ansari, and recruit

young scientists.

“We need to encourage researchers to go into the field

by giving them seed funding, as well as a sense they can

partner with JDRF,” says Dr. Lewis. “This research takes

time, and we want researchers to know they will have the

support they need.”

A National Quest

the complications of the

disease itself.”

The collaboration between

Drs. Wood and Osborne

is typical of the Institute’s

approach to research—

different labs investigate pieces

of the larger puzzle and pool

their knowledge. As director

of the Metabolic Signaling

and Disease Program at Lake

Nona, Dr. Osborne is eager to

recruit new scientists who will

carry on that tradition.

“Right now, we are

working to integrate people

who study various cellular

signaling pathways,” says Dr.

Osborne. “All these pathways

have common nodes. We

want to bring this knowledge

together to understand how

these mechanisms function.”

thE L ANGUAGE OF FAt

Traditionally, people have

thought of fat as being a

relatively passive part of the

body. But fat is no innocent

bystander. Researchers are

learning more about how fat

signals other areas of the

body, including the brain.

Devanjan Sikder, Ph.D., is

looking at how these signals

can affect both biological Dr. Devanjan Sikder

B U r n h a m D i A B E t E s R E s E A R c h

6 The BUrnham reporT | www.burnham.org

processes and perceptions

of food.

Dr. Sikder studies the

hormone orexin, which

controls hunger and sleep/

wake cycles. High glucose

after a meal reduces orexin

levels and the activity of

orexin-producing neurons,

making us feel sluggish.

Plunging glucose levels,

following overnight fasting,

elevate orexin, which wakes us

to find food.

The cyclic waxing and

waning of orexin appears

to be perturbed in type 2

diabetes, obesity and even

cancer. “Several epidemio-

logical studies have reported

a correlation between lower

orexin levels and a higher

incidence of obesity and type

2 diabetes,” says Dr. Sikder.

Dr. Sikder is also inter-

ested in how leptin affects

the brain. Leptin is a hormone

that controls appetite, telling

us to stop eating. Mice

without leptin become peril-

ously obese.

“Fat tissue produces

leptin, which tells us to stop

eating,” says Dr. Sikder. “But

if you lose weight, the body

produces less leptin and

you have lost a physiological

incentive to stop eating. This

may be one reason why it

can be so difficult for obese

people to lose weight.”

MOViNG D iscOVERiEs FORwARD

Steve Gardell, Ph.D.,

director of Translational

Research Resources, came

to Burnham Lake Nona to

help move basic science

discoveries from the labora-

tory to the clinic. With more

than 20 years experience in

the pharmaceutical industry,

Dr. Gardell understands the

challenges of translating

basic scientific knowl-

edge into new medicines.

However, he sees many

opportunities in the work

being done at Burnham.

“My job is to help shep-herd some of these incredible

discoveries and check them

for clinical effectiveness,” says

Dr. Gardell.

One area where Dr.

Gardell hopes to have a big

impact is metabolomics.

Biochemical reactions

produce small molecules,

or metabolites, which can

be measured. Dr. Gardell

and others at Burnham are

hoping to capitalize on this

burgeoning young discipline

to create new diagnostics.

“Metabolomics is a

powerful way to identify

disease markers that could

lead to new tests and early

detection,” says Dr. Gardell.

Dr. Gardell will also

be working closely with

Drs. Gregory Roth and

Layton Smith to screen for

compounds in the Conrad

Prebys Center for Chemical

Genomics. This pain-

staking process could lead

to new chemical probes to

illuminate the underlying

mechanisms behind disease

and possibly new medicines.

One of the targets they

aim for is specificity: finding

the right chemicals that

influence the exact protein to

provide great clinical benefit

with few side effects.

“Medicine has done

all the easy things,” says

Layton Smith, Ph.D. “It’s

not that difficult to knock

out a protein. Vioxx (an anti-

inflammatory drug that was

pulled from the market due

to increased risk of heart

attack) is a good example. It

worked too well because it

completely knocked out the

Cox2 enzyme. Vioxx created

Cox2-deficient people. So we

need to create compounds

that work more subtly. We’ve

done the chainsaw; it’s time

for a scalpel.”

Dr. Layton Smith

“Metabolomics is a powerful way to

identify disease markers that could

lead to new tests and early detection,”

says Dr. Gardell.

B U r n h a m f l o r I d a N E w s

www.burnham.org | The BUrnham reporT 7

The landscape outside Dr. Daniel Kelly’s office at Burnham’s new Lake Nona campus is a work in progress. There is a sandy plain, a few puddles from a recent rainstorm, trees in the distance. But Dr. Kelly sees beyond this temporary sparseness to what Lake Nona will become as new hospitals, research facilities and a university building spring up around Burnham.

He sees multiple collabora-

tions leading to new insights

into human biology and new

treatments for heart disease,

diabetes, cancer and other

conditions. He sees Burnham’s

basic science and transla-

tional research expertise as a

critical piece of Lake Nona’s

burgeoning medical city.

“This is the perfect environ-

ment to create a truly innovative

style of research,” says Dr. Kelly.

“We are already breaking down

the silos that separate physi-

cians and basic researchers. The

Florida Hospital – Burnham

Clinical Research Institute (see

article, page 13), along with

our emerging collaborations

with the University of Central

Florida, M. D. Anderson

Cancer Center-Orlando, the

Stedman Center at Duke

University, the University of

Florida and others will advance

science and bring new treat-

ments to patients—faster.

Burnham has an incredible

track record of breaking down

disciplinary barriers and we plan

to continue that tradition.”

One area Dr. Kelly wants

to explore is diabetic heart

disease. He notes that heart

failure is not a single condition

that will respond to one-size-

fits-all medicines. Researchers

and clinicians need to

understand the underlying

distinctions between different

types of heart disease, so that

the best treatments can be

prescribed based on a clear

understanding of what is going

wrong in the heart.

“Diabetic heart disease is

more aggressive and different

from other forms of heart

disease,” says Dr. Kelly. “If we

follow diabetics after a heart

attack and give them the usual

therapies—cholesterol lowering

drugs, ACE inhibitors—we’ve

found that those treatments

don’t work as well. We’re only

beginning to understand that

heart and vascular disease in

diabetics may have a completely

different basis.”

LEVERAGiNG tEchNOLOGy

One of Burnham’s trade-

marks is the strategic use of

sophisticated technologies. For

example, Lake Nona’s Conrad

Prebys Center for Chemical

Genomics, like the facility in

La Jolla, will identify small

molecule compounds that

can help regulate proteins

implicated in disease. In

addition, the Cardiovascular

Pathobiology program at Lake

Nona will enhance the study of

fat metabolism, type 2 diabetes,

heart disease and other condi-

tions. This will be supported by

the emerging Cardiometabolic

Phenotyping Core, which will

diagnose cardiovascular disease

and metabolic disturbances in

small animal models.

Dr. Kelly is particularly

excited about the collabora-

tion with Duke University’s

Stedman Center to establish

a metabolomics core facility.

Every chemical reaction in the

body produces compounds

called metabolites, which can

be measured and catalogued.

These markers can help

physicians detect diseases or

metabolic defects and test

treatments for effectiveness.

Metabolomics provides a link

between the laboratory and the

clinic. As researchers learn more

about the metabolome (the list

of all metabolites), they can

develop better diagnostic tools.

“There are different kinds of

cancer, and we are very sophis-

ticated in describing them,” says

Dr. Kelly. “But in heart failure,

we lack the sophistication to

distinguish between different

disease types and causes. We

just call it heart failure. In our

research, we are trying to reca-

pitulate different types of heart

failure to find the metabolic or

genomic signatures that will

help us individualize treatment

for each patient based on the

precise nature of their disease.

If we can recognize these signa-

tures, or markers, we will be

able to tell whether a person’s

heart failure is more related to

diabetes or high blood pressure

or heart attack. Physicians will

know the exact condition they

are seeing and that will lead to

innovative treatments.”

The View from Lake Nona

Daniel Kelly, M.D., Scientific Director, Burnham at Lake Nona

Gregg Duester, Ph.D., professor in the Develop-ment and Aging Program at Burnham, Xianling Zhao, Ph.D., and colleagues have clarified the role that retinoic acid plays in limb development.

The study showed that

retinoic acid controls the

development (or budding) of

forelimbs, but not hindlimbs,

and that retinoic acid is not

responsible for patterning (or

differentiation of the parts) of

limbs. This research corrects

longstanding misconceptions

about limb development and

provides new insights into

congenital limb defects. The

study was published online in

the journal Current Biology on

May 21.

“For decades, it was thought

that retinoic acid controlled limb

patterning, such as defining

the thumb as being different

from the little finger,” says Dr.

Duester. “However, we have

demonstrated in mice that reti-

noic acid is not required for

limb patterning but rather is

necessary to initiate the limb

budding process.”

By providing a more

complete understanding of the

molecular mechanisms involved

in normal limb development,

these findings may lead to new

therapeutic or preventative

measures to combat congenital

limb defects, such as Holt-Oram

syndrome, a birth defect charac-

terized by upper limb and heart

defects.

B U r n h a m s c i E N c E N E w s

8 The BUrnham reporT | www.burnham.org

Embryology Study Offers

Clues to Birth Defects

Dr. Gregg Duester

Investigators at Burnham and the University of Connec- ticut Health Center (U.C.H.C.) have gained new under-standing of the role hyaluronan (also known as hyaluronic acid or HA) plays in skeletal growth, cartilage maturation and joint formation in developing limbs.

Significantly, these discov-

eries were made using a novel

mouse model in which the

production of hyaluronan is

blocked in specific tissues. The

Yamaguchi laboratory geneti-

cally modified the Has2 gene,

which is a critical enzyme for

hyaluronan synthesis, so that

the gene can be “condition-

ally” disrupted in mice. This

is the first time a conditional

Has2 knockout mouse has

been created, a breakthrough

that opens vast possibilities for

future research. The paper was

published online in the journal

Development on July 24.

HA is a large sugar

molecule that is produced by

every cell in the body and has

been thought to play a role in

joint disease, heart disease and

invasive cancers. Yu Yamaguchi,

M.D., Ph.D., a professor in

the Sanford Children’s Health

Research Center at Burnham

and Robert Kosher, Ph.D.,

a professor in the Center

for Regenerative Medicine

and Skeletal Development

at U.C.H.C. and colleagues

showed that transgenic mice,

in which Has2 was inactivated

in the limb bud mesoderm,

had shortened limbs, abnormal

growth plates and duplicated

bones in the fingers and toes.

“Because hyaluronic acid is

so prevalent in the body, it has

been difficult to study,” said Dr.

Yamaguchi. “Systemic Has2

knockout mice died mid-gesta-

tion and could not be used to

study the role of hyaluronan in

adults. By inactivating Has2

in specific tissues, we give

ourselves the opportunity to

study the many roles hyal-

uronan plays in biology. This

mouse model will be useful to

study the role of hyaluronan in

arthritis and skin aging, as well

as cancer.”

New Insights into Limb FormationDrs. Kazu Matsumoto and Yu Yamaguchi

B U r n h a m s c i E N c E N E w s

www.burnham.org | The BUrnham reporT 9

Tariq Rana, Ph.D., director of the Program for RNA Biology at Burnham, and colleagues have discovered that specific microRNAs (non-coding

RNAs that interfere with gene expression) reduce HIV replication and infectivity in human T cells.

In particular, miR29 plays a

key role in controlling the HIV

life cycle. The study suggests

that HIV may have co-opted

this cellular defense mechanism

to help the virus hide from

the immune system and anti-

viral drugs. The research was

published on June 26 in the

journal Molecular Cell.

The team found that the

microRNA miR29 suppresses

translation of the HIV-1 genome

by transporting the HIV

mRNA to processing bodies (P-

bodies), where they are stored

or destroyed. This results in a

reduction of viral replication

and infectivity. The study also

showed that inhibition of miR29

enhances viral replication and

infectivity. The scientists further

demonstrated that strains of

HIV-1 with mutations in the

region of the genome that

interact with miR29 are not

inhibited by miR29.

“We think the virus may

use this mechanism to modu-

late its own lifecycle, and we

may be able to use this to our

advantage in developing new

drugs for HIV,” says Dr. Rana.

“Retroviral therapies greatly

reduce viral load but cannot

entirely eliminate it. This

interaction between HIV and

miR29 may contribute to that

inability. Perhaps, by targeting

miR29, we can force HIV into

a more active state and improve

our ability to eliminate it.”

MicroRNAs and HIV

Minoru Fukuda, Ph.D., and colleagues have discovered that specialized complex sugar molecules (glycans) that anchor cells into place act as tumor suppressors in breast and prostate cancers.

These glycans play a

critical role in cell adhe-

sion in normal cells, and

their decrease or loss leads

to increased cell migra-

tion by invasive cancer

cells and metastasis. An

increase in expression of

the enzyme that produces

these glycans, β3GnT1,

results in a significant reduc-

tion in tumor activity. The

research was published July

6 in the journal Proceedings

of the National Academy of

Sciences.

The specialized glycans

are capable of binding to

laminin and are attached

to the α-dystroglycan cell

surface protein. This binding

facilitates adhesion between

the epithelium and basement

membrane and prevents cells

from migrating. The team

demonstrated that β3GnT1

controls the synthesis of

laminin-binding glycans

in concert with the genes

LARGE/LARGE2. Down-

regulating β3GnT1 reduces

the amount of the glycans,

leading to greater move-

ment by invasive cancer

cells. However, when the

researchers forced aggres-

sive cancer cells to express

β3GnT1, the laminin-

binding glycans were

restored and tumor forma-

tion decreased.

These results indicate

that certain carbohydrates

on normal cells and enzymes

that synthesize those

glycans, such as β3GnT1,

function as tumor suppres-

sors,” says Dr. Fukuda. “Up

regulation of β3GnT1 may

become a novel way to treat

cancer.”

Carbohydrate Acts as Tumor Suppressor

Dr. Tariq Rana

Dr. Minoru Fukuda

B U r n h a m s c i E N c E N E w s

10 The BUrnham reporT | www.burnham.org

Investigators at Burnham and The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have made the first comparative, large-scale phosphoproteomic analysis of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and their differentiated derivatives.

The data may help stem

cell researchers understand the

mechanisms that determine

whether stem cells divide or

differentiate, what types of cells

they become and how to control

those complex mechanisms

to facilitate development of

new therapies. The study was

published in the August 6 issue

of the journal Cell Stem Cell.

“While the field of stem cell

biology has become accustomed

to looking at changes in genes,

we have come to realize that

proteins are the real work horses

and ultimately determine cell

behavior,” says Evan Snyder,

M.D., Ph.D., professor and

director of Burnham’s Stem

Cell and Regenerative Biology

program. “This study represents

the first comprehensive study

of genes being activated during

differentiation and offers predic-

tions on cell behavior.”

Protein phosphorylation,

the biochemical process

that modifies protein activi-

ties by adding a phosphate

molecule, is central to cell

signaling. Using sophisticated

phosphoproteomic analyses,

the team of Laurence Brill,

Ph.D., senior scientist at

Burnham’s Proteomics Facility,

Dr. Synder and Sheng Ding,

Ph.D., associate professor

at TSRI, catalogued 2,546

phosphorylation sites on 1,602

phosphoproteins. Prior to this

research, protein phosphoryla-

tion in hESCs was poorly

understood. Identification of

these phosphorylation sites

provides insights into known

and novel hESC signaling path-

ways and highlights signaling

mechanisms that influence self-

renewal and differentiation.

“This research will be a big

boost for stem cell scientists,”

said Dr. Brill. “The protein

phosphorylation sites identified

in this study are freely avail-

able to the broader research

community, and researchers can

use these data to study the cells

in greater depth and determine

how phosphorylation events

determine a cell’s fate.”

What Makes Stem Cells Tick

Cancer Center director Kristiina Vuori, M.D., Ph.D., and colleagues have found that the Caspase-8 protein, long known to play a major role in promoting programmed cell death (apoptosis), helps relay signals that can cause cancer cells to proliferate, migrate and invade surrounding tissues.

The study was published in

the journal Cancer Research on

June 15.

The team showed that

Caspase-8 caused neuroblas-

toma cancer cells to proliferate

and migrate. For the first time,

Caspase-8 was shown to play a

key role in relaying the growth

signals from epidermal growth

factor (EGF) that cause cell

division and invasion. The

researchers also identified an

RXDLL amino acid motif that

controls the signaling from

the EGF receptor through

the protein kinase Src to

the master cell proliferation

regulator protein MAPK. This

same signaling pathway stimu-

lates neuroblastoma cells to

migrate and invade neighboring

tissues—a critical process in

cancer metastasis.

“Caspase-8 has a well

defined role in promoting

apoptosis, especially in response

to activation of the so-called

death receptors on the outside

of cells,” says Darren Finlay,

Ph.D., first author on the

paper. “Although Caspase-8 is

involved in apoptosis, it is rarely

deleted or silenced in tumors,

suggesting that it was giving

cancer cells a leg up in some

other way.”

Caspase 8 and Invasive

Cancer

Drs. Evan Snyder and Laurence Brill

Dr. Kristiina Vuori

B U r n h a m s c i E N c E N E w s

JAMEy MARth, Ph.D.

Dr. Marth joins Burnham as director of the U.C. Santa Barbara-Burnham Center for Nanomedicine.

The center will focus

on the emerging fields of

nanotechnology and bioen-

gineering to identify the

molecular and cellular origins

of disease and develop new

approaches to diagnosis,

prevention and cure.

Dr. Marth’s laboratory

is known for integrating

molecular and cellular biology

as a means to discover

the origins of disease. His

research has enumerated the

building blocks of the four

fundamental components

of all cells and combined

them into a research plat-

form that has revealed

pathophysiologic origins of

autoimmune disease, sepsis

and dietary-induced type 2

diabetes. The Marth labora-

tory previously developed

the Cre-loxP technology that

is now used throughout the

world as a mainstay technique

in biomedical research. Dr.

Marth’s discoveries have

spanned multiple fields

including immunology, hema-

tology, metabolism, oncology,

glycobiology, neurobiology

and infectious diseases and

are unique in combined

breadth and accomplishment.

Dr. Marth earned his

Ph.D. in pharmacology from

the University of Washington,

where he worked under Dr.

Edwin G. Krebs, a 1992

Nobel laureate in medicine

and Dr. Roger M. Perlmutter,

now executive vice president

of Research and Development

at Amgen.

New Faculty

Dr. Jamey Marth

Gary Chiang, Ph.D., and colleagues have elucidated how the stability of the REDD1 protein is regulated.

The REDD1 protein is a

critical inhibitor of the mTOR

signaling pathway, which

controls cell growth and prolifer-

ation. The study was published

in the August 2009 issue of

EMBO Reports.

As part of the cellular

stress response, REDD1 is

expressed in cells under low

oxygen conditions (hypoxia).

The Burnham scientists showed

that the REDD1 protein rapidly

undergoes degradation by the

ubiquitin-proteasome system,

which allowed for the recovery

of mTOR signaling once oxygen

levels were restored to normal.

“Cells initially shut down the

most energy-costly processes,

such as growth, when they’re

under hypoxic stress,” says

Dr. Chiang. “They do this by

expressing REDD1, which

inhibits the mTOR pathway. But

when the cell needs the mTOR

pathway active, REDD1 has to

be eliminated first. Because the

REDD1 protein turns over so

rapidly, it allows the pathway

to respond very dynamically

to hypoxia and other environ-

mental conditions.”

Unraveling How Cells Respond

to Low Oxygen

www.burnham.org | The BUrnham reporT 11

Drs. Enbo Liu and Gary Chiang and Christine Knutzen

Dr. Marth’s discoveries have spannedmultiple fields including immunology, hematology, metabolism, oncology, glycobiology, neurobiology and infectious diseases and are unique in combined breadth and accomplishment.

12 The BUrnham reporT | www.burnham.org

B U r n h a m s c i E N c E N E w s

JULiO AyAL A, Ph.D.

An assistant professor at Lake Nona, Dr. Ayala, comes to Burnham from Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, where he was a research faculty member and director of Technology Transfer at the Vanderbilt-NIH Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center.

Dr. Ayala received his

Ph.D. and conducted his post-

doctoral work in molecular

physiology and biophysics at

Vanderbilt. He has studied

factors that increase the

production and secretion

of insulin. His research has

shown that the hormone

GLP-1 affects not only the

secretion of insulin but also

insulin action on the liver and

skeletal muscle. At Burnham,

he will focus on the control of

inter-organ fuel metabolism

with emphasis on the regula-

tion of glucose production and

utilization. He seeks to reveal

how metabolic syndrome is

influenced by errors in sugar

and fat metabolism and to use

those findings to pursue new

treatments for diabetes and

obesity. Dr. Julio Ayala

tiMOthy OsBORNE, Ph.D.

Dr. Osborne joins Burnham at Lake Nona as professor and director of the Metabolic Signaling and Disease Program.

His research seeks to

understand how the body

senses dietary content to alter

nutrient absorption with an

emphasis on how this influences molecular mechanisms relevant

to diabetes and obesity.

Dr. Osborne received his doctorate in microbiology and

molecular biology from the University of California, Los

Angeles, conducted postdoctoral research at the University of

Texas at Southwestern Medical School and was most recently

chair of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry at the University

of California, Irvine. He has received a Chancellor’s Award

for mentoring undergraduate research, was recognized as an

Established Investigator of the American Heart Association

and received a Lucille P. Markey Scholar Award in Biomedical

Science.Dr. Timothy Osborne

RANJAN PERERA, Ph.D.

Dr. Perera comes to Burnham from Mercer University’s School of Medicine, where he was an associate professor and director of Genomics and research and develop-ment at Anderson Cancer Institute.

Dr. Ranjan Perera

He received his Ph.D. in Molecular Genetics from Moscow

State University and the University of Ghent-Belgium. Dr. Perera

completed his post-doctoral studies in gene targeting and DNA

recombination at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He has

many years of industry experience and holds numerous patents

related to gene regulation.

As an associate professor at Lake Nona, Dr. Perera seeks to

identify prognostic and diagnostic markers for melanoma and will

lead Burnham’s analytical genomics lab and establish expertise in

RNA biology. His research is partly supported by a Department of

Defense grant to study the link between obesity and cancer.

New Faculty continued

12 The BUrnham reporT | www.burnham.org

Burnham has been selected as one of three compre-hensive centers in a new National Cancer Institute (NCI) Chemical Biology Consortium, an integrated network of chemical biolo-gists, molecular oncologists and chemical screening centers.

The consortium will trans-late knowledge from leading academic institutions into new drug treatments for cancer patients. Burnham’s La Jolla and Lake Nona campuses will both participate.

The NCI seeks to coordi-nate their own drug discovery efforts with academic institu-tions and private companies

to expedite the development and distribution of new cancer treatments. The consortium will expand current NCI programs in personalized medi-cine to identify and advance

novel drug candidates in high-risk, under-represented areas of cancer biology.

“Burnham’s strategic focus for the past five years has been on building our capabilities in chemical genomics and drug discovery,” says President and CEO John Reed, M.D., Ph.D. “The Chemical Biology Consortium gives Burnham an additional platform to use our advanced technologies, some of which are virtually unprec-edented in the not-for-profit research world.”

www.burnham.org | The BUrnham reporT 13

Burnham Chosen for

National Chemical Biology Consortium

B U r n h a m N E w s

Steven R. Smith, M.D., an internationally-renowned diabetes and obesity researcher, has been

appointed execu-tive director of the Florida Hospital –Burnham Clinical

Research Institute, which will investigate diabetes, obesity and cardiovascular disease.

“Our vision was to recruit a world-class physician and scientist to lead our mission,” says Dr. Daniel Kelly, Scientific Director of Burnham at Lake Nona. “We have found the very best and are delighted that Dr. Smith will be

directing the new institute.”Florida Hospital will also

build a state-of-the-art, 35,000 square-foot facility to house the Clinical Research Institute. Groundbreaking is scheduled for early 2010. The Institute will combine scientists and clinicians with sophisticated technology to enhance transla-tional research and bring new treatments to patients.

Burnham and the Sarah W. Stedman Nutrition and Metabolism Center (Stedman Center) at Duke University Medical Center have announced a new collaboration to use meta-bolomic profiling to clarify the basic mechanisms

of disease and identify biomarkers for diagnosis and treatment.

The agreement will estab-lish an extension of Duke’s Stedman Center laboratory at Burnham’s Lake Nona campus and combines the Stedman

Center’s metabolomics expertise with Burnham’s complementary technologies.

The Stedman Center is well known for its metabolic research, particularly metabo-lomic profiling of biological samples using mass spectrom-etry-based technologies. The Burnham-Stedman metabo-lomics platform will create collaborative opportunities and expand the research capacity of both Duke University and Burnham.

“Burnham and Stedman Center scientists will be able to exploit the power of these technologies to define disease signatures relevant to diabetes, heart disease, cancer and other diseases” says Dr. Daniel Kelly, Scientific Director, Burnham at Lake Nona. “Metabolomic approaches show great promise for identifying diagnostic markers that will aid clini-cians in distinguishing disease patterns and in developing individualized treatment plans.”

Clinical Research Institute Moves Forward

Burnham Collaborates with

Duke University Metabolomics Center

14 The BUrnham reporT | www.burnham.org

p h I l a n T h r o p y U P D A t E

Estate Planning In

Challenging TimesKen G. Coveney, Esq.

Burnham Planned Giving Advisory Council

Every cloud has a silver lining. We have been in difficult economic times for awhile, but most people remain opti-mistic about the future. Now is the time to take advantage of these circumstances.

Interest rates are near historic lows. Make loans to children

and grandchildren or trusts for their benefit. A loan at the

applicable federal rate (AFR) for long-term loans (more than

nine years) is 4.33 percent. A loan at the AFR is not a gift. If

the children/borrowers can obtain a higher return than the AFR,

they will reap future value at no transfer tax cost to the parents/

lenders. If the parents see a good investment opportunity, they

can allow the children to capture it by lending them the funds to

acquire the investment.

Installment sales use the same interest rates as loans. A sale

of an appreciating asset transfers the appreciation from the seller

to the buyer without gift tax cost. If the asset is depressed real

property selected with location in mind, it likely will come back

eventually. Allow children to capture the recovery by selling it to

them now.

Outright gifts while values are depressed are even better than

sales. If a parent sells to a child (or a trust for the child’s benefit),

and if the sale price is less than the parent’s basis, the parent’s loss

on sale will be disallowed, but the child (or trust) will be stuck

with lower basis. If the parent gives the property to the child (or

trust), the recipient will take the donor’s higher income tax basis

for purposes of computing gain when they dispose of the property.

Consider transfers in trust with remainder interests to chil-

dren or the Burnham Institute for Medical Research. If a donor

transfers assets to a grantor retained annuity trust (GRAT), the

value of the retained annuity interest will be higher in this low

interest environment.

Similarly, if a donor transfers assets to a charitable lead annuity

trust (CLAT), the value of the annuity interest given to the

Burnham will be higher in this low interest environment and the

value of the remainder interest gifted to the children will be lower.

Remember, in both a GRAT and a CLAT, the present value of the

remainder interest is what counts for gift tax purposes.

So don’t surrender!! The iron is hot; now is the time to strike.

Lake Nona’s new asso-ciate director for external relations Julie Johnson is a seasoned development professional with more than 26 years experience.

“I became interested in

nonprofit work when I was

a student at the University

of Florida,” says Johnson.

“I had an internship with

the Muscular Dystrophy

Association (MDA) over the

summer and that’s where the

love affair began.”

Johnson graduated with

a degree in journalism and

continued with the MDA

as an events coordinator.

Later, she served as assistant

executive director for the

Leukemia and Lymphoma

Society; president and

CEO of the Mental Health

Association of Northeast

Florida; regional vice president

of the Arthritis Foundation of

Northeast Florida; president

of Expedition Inspiration

Fund for Breast Cancer

Research and, most recently,

director of development for

the College of Engineering

at the University of Florida,

Gainesville.

“I’m excited to be part

of Burnham at Lake Nona,”

says Johnson. “My sister died

from a heart attack at 47

as a result of uncontrolled

type 2 diabetes. Obesity and

diabetes are challenging health

issues, and I am certain that

researchers at Burnham will

make significant discoveries

that will advance our ability to

treat them.”

Burnham Welcomes

Julie Johnson

Julie Johnson

Team BurnhamwALt DisNEy wORLD, ORL ANDO, FLORiDAJANUARy 9 AND 10, 2010

Team Burnham for Medical Research will be running the Walt Disney World Half Marathon & Marathon to raise support for Burnham’s cutting-edge biomedical research. Regardless of age or experience, we welcome all runners to join us and run for discovery.

Our coaches have put together a training program that can get

anyone over the line for either the half (13.1 miles) or full (26.2

miles) marathons. Or, if you are feeling Goofy, you can do both —

and there is still time to join.

“I had never run a step in my life, and certainly never thought

I could run a half marathon,” says Catlin Potter Valmont, who

is returning for her second half marathon. “Training with Team

Burnham was the inspiration I needed to get into shape and

complete what I thought to be impossible.”

Each team member raises $2,500 to fund Burnham research,

with the overall goal of raising more than $150,000. The top

fundraiser will receive two free tickets anywhere AirTran flies. All

participants will have their own fundraising page and will receive

professional training, race gear by Brooks, personal shoe fittings and

discounts at Fleet Feet, all race weekend accommodations, local

transportation, all meals, a one-day Disney pass and the only cour-

tesy RV at the finish line.

To become a member of Team Burnham, please contact Kathy

Pierson at 407-595-8099 or log onto www.teamburnham.org.

Just as the ancient chariot was critical to warfare, Burnham’s Chair-iot Society seeks to battle disease by raising funds and awareness of Burnham’s mission.

Please consider being

an inaugural supporter of

Burnham at Lake Nona by

placing your name on one

of the 201 chairs in our

state-of-the-art audi-

torium. Membership

in the Chair-iot

Society is $1,000

and entitles you

to annual briefings about

Burnham’s cutting edge

science at the Lake Nona

campus.

“As Florida natives,

my husband and I were

excited to be able to put our

name on the future of science

in Central Florida,” says Dr.

Nicole Beedle. “And as a

doctor, I am personally proud

of the research going on in

Orlando.”

The Chair-iot Society

will host an Unveiling Event

October 9, 2009 at 7 p.m.

For more information,

please call 407-745-2061.

SPONSORS

www.burnham.org | The BUrnham reporT 15

p h I l a n T h r o p y U P D A t E

The Chair-iot Society

SILVERSPONSORS

GOLDSPONSORS

p h I l a n T h r o p y U P D A t E

Each year, the Fishman Fund

Award, established in honor of

Dr. William and Lillian Fishman,

recognizes a group of outstanding

postdoctoral fellows for their

hard work and scientific vision.

Burnham and the Fishman Fund

cordially invite you to this year’s

reception to recognize the 2009

Award recipients.

Please RSVP by October 12

to Wendy Sunday at wendys@

burnham.org or 858-646-3100,

extension 3420.

16 The BUrnham reporT | www.burnham.org

The basic biomedical

research at Burnham produces

knowledge, treatments and

even art. Co-chaired by

Caroline Nierenberg and

Kathryn Stephens, this year’s

gala celebrates the art of

science, as the ballroom will

be transformed into a gallery of

inspiring images taken directly

from the research bench.

sNEAk PEEk

The Fund-A-Need will

support talented young

scientists and help purchase

essential technology to

enhance Burnham research on

cancer, as well as infectious

and inflammatory, neurode-

generative and childhood

diseases. The live auction will

feature a jet trip and dinner

in Napa Valley, a dinner party

at Pamplemousse Grille and

an internship with John C.

Reed, M.D., Ph.D, Burnham

President and CEO,

Professor and Donald Bren

Presidential Chair.

This year’s presenting

sponsor is Life Technologies

and lead sponsors include

Jeanne and Gary Herberger,

Roberta and Malin Burnham

and Peggy and Peter Preuss.

The Burnham Gala sells

out every year, so be sure

to reserve your seats today.

Tickets and sponsorship

opportunities are still avail-

able. For more information,

please contact Chelsea Jones

at 858-795-5239 or cjones@

burnham.org.

Saturday, November 14, 2009 Hyatt Regency La Jolla Aventine

6:00 pm Cocktail Reception

7:00 pm Dinner, Auction, Dancing

“The art and science of asking questions is the

source of all knowledge.” —Thomas Berger

h E L P i N G y O U N G R E s E A R c h s c i E N t i s t s s O t h E y c A N h E L P t h E w O R L D

Thursday, October 15, 2009 5:30 pm

at Burnham Institute for Medical Research

10901 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla

The Power to Cure Gala 2009

This award-winning image of Osteoclasts was produced by Dr. Melanie Hoefer in the Rickert laboratory.

p r e s I d e n T ’ s M E s s A G E

www.burnham.org | The BUrnham reporT 17

15. JohnReedessay

Scientific Excellence Fuels Strong GrowthIn our 33rd year, Burnham has surpassed significant milestones in scientific achievement,

research staffing and infrastructure development. As of July 1, the Institute exceeded 1,000

employees, including 74 full-time faculty and 800 scientific staff.

With the opening of Burnham’s Lake Nona campus in Orlando, Florida, the acquisition of

an additional research building in La Jolla, California and the creation of the joint Center for

Nanomedicine with the University of California, Santa Barbara, we have increased our space

from 382,000 square feet in January 2009 to more than 671,000 square feet today. This continued

growth is creating many opportunities to expand the boundaries of scientific knowledge and

increase employment opportunities during these challenging times.

Although we are growing rapidly, we have also maintained strong attention to quality, as

evidenced by Burnham’s number one ranking for the past decade in scientific journal citations per

publication in the fields of biology and biochemistry among all organizations worldwide.

In the past two years alone, the Institute has published more than 600 research papers in

scientific journals. These papers advanced understanding of the mechanisms underlying cancer,

Alzheimer’s, HIV, diabetes and many other conditions. Among many recent advances, Burnham

researchers have helped discover monoclonal antibodies that attack a variety of flu strains, illumi-

nated how HIV co-opts cellular mechanisms to create persistent infections, devised novel chemicals

that attack anti-death proteins responsible for sustaining malignant cells and thus providing a

means to kill chemoresistant cancer cells, elucidated how protein misfolding and protein oxidation

contribute to the demise of brain cells in Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative

diseases and generated replacement heart cells from synthetically-produced stem cells as a new

approach to treating heart attack and heart failure.

We have also increased our overall grants and contract revenue. We are the only organization

in the nation to achieve more than five consecutive years of growth in funding from the National

Institutes of Health (NIH), averaging 11.5 percent annual growth for the past 8 years. Last year,

Burnham received a $98 million contract from the NIH to support a national network in chemical

genomics, as well as an $8 million NIH grant to establish a national Parkinson’s disease research

center. While covering more than 90 percent of costs from competitive grants, we have also

secured important philanthropic gifts to help accelerate our research programs. South Dakota

banker T. Denny Sanford donated $20 million to create the Sanford Children’s Health Research

Center, San Diego developer Conrad Prebys gave $10 million to name the Conrad Prebys Center

for Chemical Genomics and Irvine Companies owner Donald Bren contributed $2.5 million to

create the Donald Bren Presidential Chair at Burnham.

At Burnham, our motto is From Research, the Power to Cure. By adding more scientists to our

team and providing them with additional laboratory space, we hope to accelerate our efforts to trans-

late basic science discoveries into better treatments that reduce human suffering around the world.

John C. Reed, M.D., Ph.D.

President and CEO

Professor and Donald Bren

Presidential Chair

In the past two years alone, the Institute has published more than 600 research papers in scientific journals. These papers advanced understanding of the mechanisms underlying cancer, Alzheimer’s, HIV, diabetes and many other conditions.

p h I l a n T h r o p y

Printed on recycled paper

Denny Sanford wants to help

medical scientists cure type 1

diabetes in his lifetime. He has

created the Sanford Project to

achieve this goal. Fred Levine,

M.D., Ph.D., director of Burnham’s

Sanford Children’s Health Research

Center, is also working to find a

cure. Both a research scientist and

a practicing physician, Dr. Levine

knows well the suffering type 1

diabetes can cause. His laboratory

is investigating new ways to replace

insulin-producing beta cells, either

through transplants or regeneration.

Partners in Science: Denny Sanfordand Dr. Fred Levine

Nonprofit OrganizationU.s. Postage

PAiDthe Burnham institute

“Injected insulin does not cure type 1 diabetes,” says Denny Sanford. “But by gathering the best scientific minds to investigate the immune system and beta cell regeneration, we will find a cure.”

6400 Sanger Road

Orlando, FL 32827