Fair Housing Movements and Their Opposition in the Non-Jim Crow Midwest

-

Upload

marcus-van-grinsven -

Category

Documents

-

view

53 -

download

0

Transcript of Fair Housing Movements and Their Opposition in the Non-Jim Crow Midwest

Fair Housing Movements and Their Opposition in the Non-Jim Crow Midwest

By Marcus Van GrinsvenHistory 600: Seminar In History

Professor Joe AustinMay 13, 2015

Introduction:

In the summer of 1966, Dr. Martin Luther King came to Chicago to bring the battle for

civil rights to the north. He became of the leaders of the Chicago Freedom Movement, which

was a movement to promote civil rights, particularly open housing, for African Americans in

Chicago. The following summer, a Catholic Priest form Milwaukee named Father James Groppi

led a similar movement in Milwaukee. While local elected officials tended to support civil

rights causes at the national level, they resisted them at the local level. In 1968, the Fair

Housing Act was passed by Congress.

There were many similarities between these two movements. They were both led by men

of the Clergy, King, a Baptist Minister, and Groppi, a Catholic Priest. Both of these men were

outsiders of a sort, King was not from the Chicago area, and Groppi was white. Both marches

began as non-violent, but unlike similar marches in the American south, the northern marchers

were willing to physically defend themselves against mob violence, even at the hands of the

police.

The mayors of both Milwaukee and Chicago, Henry W. Maier and Richard J. Daley,

respectively, as well as most other elected officials from the cities were resistant and

unsympathetic to the cause at the local level. Maier supported civil rights on the national level,

but didn’t want a patchwork of local laws. Daley was a friend and ally of President Lyndon

Johnson, who was a major proponent of civil rights.

Today these marches in the Midwest are not well as well-known outside of their own

communities as well as the earlier movements in the south, in cities such as Birmingham and

Selma. In their own time, they did not evoke the public sympathy that the earlier marches in the

south had.

The south had a well-known history of segregation from the days of slavery to the Jim

Crow era. It’s city, county, and state governments were mostly unified in their policies of

segregation which were codified as “Jim Crow Laws”. In the cities of the north, de jure

segregation was never a major issue. Where people lived was determined by where they could

afford to live, but more importantly, where they could find a seller or landlord willing to sell or

rent to them. Politicians at different levels of government quarreled and passed the buck on fair

housing and other civil rights issues. While media coverage of protests in Alabama showed

images of police spraying hoses and sicking dogs on peaceful protesters, including children;

there was no such graphic coverage of the civil rights movement in the north. The media

coverage in the north focused more on rioting blacks. Many in the north sympathized with the

civil rights movement, but felt threatened by it when it meant racial integration in their own

neighborhood. The main reasons the civil rights marches of the north faded into historical

obscurity in contrast with Selma and Birmingham is because of bias and a lack of attention

by the media, the fact that southern marches were totally non-violent, while the northern

marches usually had some kind of security force that practiced self-defense, and the fact

the politicians as well as civil rights leaders in the north, while not opposed to civil rights

and open housing, failed to act on a local level.

A Review of the Historical Literatures on Chicago Freedom Movement and The Milwaukee

Marches

In their article “Symposium: The Fair Housing Act After 40 Years: Continuing The

Mission To Eliminate Housing Discrimination And Segregation: Non-Violent Direct Action And

The Legislative Process: The Chicago Freedom Movement And The Federal Fair Housing Act,”

Leonard S. Rubinowitz and Kathryn Shelton compare the Chicago Freedom Movement to civil

rights movements in the Alabama cities of Birmingham and Selma. A leader of this movement

was Martin Luther King, who brought his civil rights leadership to the north after his successful

voting rights campaign in Alabama. King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference

teamed up with local activists to form the Chicago Freedom Movement, to target discrimination

in Chicago’s housing market1.

One of the reasons for selecting Chicago as a northern city was because King and the

SCLC believed that Mayor Richard J. Daley would be sympathetic to their cause, since Daley

had sponsored one of the SCLC’s biggest fundraisers just two years earlier2. Daley and other

elected officials tried at first to negotiate with the marchers, but grew unsympathetic after

1 Leonard S. Rubinowitz and Kathryn Shelton, “The Fair Housing Act after 40 Years: Continuing theMission to Eliminate Housing Discrimination and Segregation: Non-Violent Direct Action and the Legislative Process: The Chicago Freedom Movement and the Federal Fair Housing Act” Indiana Law Review 41 Ind. L. Rev. 663 (2008): 2, accessed March 22, 2015, http://www.lexisnexis.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hottopics/lnacademic/?verb=sr&csi=222360&sr=AUTHOR(Rubinowitz)%2BAND%2BTITLE(THE+FAIR+HOUSING+ACT+AFTER+40+YEARS%3A+CONTINUING+THE+MISSION+TO+ELIMINATE+HOUSING

2 Leonard S. Rubinowitz and Kathryn Shelton, “The Fair Housing Act after 40 Years: Continuing theMission to Eliminate Housing Discrimination and Segregation: Non-Violent Direct Action and the Legislative Process: The Chicago Freedom Movement and the Federal Fair Housing Act” Indiana Law Review 41 Ind. L. Rev. 663 (2008): 4, accessed March 22, 2015, http://www.lexisnexis.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hottopics/lnacademic/?verb=sr&csi=222360&sr=AUTHOR(Rubinowitz)%2BAND%2BTITLE(THE+FAIR+HOUSING+ACT+AFTER+40+YEARS%3A+CONTINUING+THE+MISSION+TO+ELIMINATE+HOUSING

receiving backlash from working class white voters, one of his prized voting blocs, for allowing

the marches to occur3.

President Lyndon Johnson was trying to get a federal fair housing bill through Congress,

and had called on civil rights activists like King for their help. King hoped the movement in

Chicago would create momentum to get the federal bill enacted4. Unlike many earlier civil rights

measures that had been passed by Congress, the federal fair housing bill would have more of an

effect on the north than the south5.

When the non-violent activists of the Chicago freedom movement marched for open

housing into white neighborhoods they were usually met with violent opposition from the

residents. A major difference is that in Chicago, the violence was perpetrated against the

3 Leonard S. Rubinowitz and Kathryn Shelton, “The Fair Housing Act after 40 Years: Continuing theMission to Eliminate Housing Discrimination and Segregation: Non-Violent Direct Action and the Legislative Process: The Chicago Freedom Movement and the Federal Fair Housing Act” Indiana Law Review 41 Ind. L. Rev. 663 (2008): 9, accessed March 22, 2015, http://www.lexisnexis.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hottopics/lnacademic/?verb=sr&csi=222360&sr=AUTHOR(Rubinowitz)%2BAND%2BTITLE(THE+FAIR+HOUSING+ACT+AFTER+40+YEARS%3A+CONTINUING+THE+MISSION+TO+ELIMINATE+HOUSING

4 Leonard S. Rubinowitz and Kathryn Shelton, “The Fair Housing Act after 40 Years: Continuing theMission to Eliminate Housing Discrimination and Segregation: Non-Violent Direct Action and the Legislative Process: The Chicago Freedom Movement and the Federal Fair Housing Act” Indiana Law Review 41 Ind. L. Rev. 663 (2008): 7, accessed March 22, 2015, http://www.lexisnexis.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hottopics/lnacademic/?verb=sr&csi=222360&sr=AUTHOR(Rubinowitz)%2BAND%2BTITLE(THE+FAIR+HOUSING+ACT+AFTER+40+YEARS%3A+CONTINUING+THE+MISSION+TO+ELIMINATE+HOUSING

5 Leonard S. Rubinowitz and Kathryn Shelton, “The Fair Housing Act after 40 Years: Continuing theMission to Eliminate Housing Discrimination and Segregation: Non-Violent Direct Action and the Legislative Process: The Chicago Freedom Movement and the Federal Fair Housing Act” Indiana Law Review 41 Ind. L. Rev. 663 (2008): 11, accessed March 22, 2015, http://www.lexisnexis.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hottopics/lnacademic/?verb=sr&csi=222360&sr=AUTHOR(Rubinowitz)%2BAND%2BTITLE(THE+FAIR+HOUSING+ACT+AFTER+40+YEARS%3A+CONTINUING+THE+MISSION+TO+ELIMINATE+HOUSING

marchers by civilians, not police as had been the case in Selma and Birmingham6. While the

police in Chicago did escort the marchers, mobs were able to breach police lines and attack the

marchers7. In Chicago, like Selma, non-violent marchers were met with violent resistance from

whites, but the Chicago marches failed to garner the same public support as their counterparts in

the south had just a few years earlier. The Fair Housing Act was enacted shortly before King’s

assassination.

In his book The Selma of the North, Patrick Jones compares and contrasts the “Bloody

Sunday” March in Selma, Alabama and the Civil Rights marches in Milwaukee. While there

were many similarities, there were also differences that may explain why the Selma march and

other southern Civil Rights movements are better remembered than the largely forgotten northern

movements. In Selma, the police were among the attackers who tried to suppress the march,

while in Milwaukee, they protected the marchers more or less. In Selma, the marchers remained

non-violent while enduring resistance, while in Milwaukee, the marchers fought back.

Milwaukee had more of an industrial base than the South, and its neighborhoods were ethnic

enclaves. The Catholic Church had a much stronger presence in Milwaukee than in most of the

South.

6 Leonard S. Rubinowitz and Kathryn Shelton, “The Fair Housing Act after 40 Years: Continuing theMission to Eliminate Housing Discrimination and Segregation: Non-Violent Direct Action and the Legislative Process: The Chicago Freedom Movement and the Federal Fair Housing Act” Indiana Law Review 41 Ind. L. Rev. 663 (2008): 8, accessed March 22, 2015, http://www.lexisnexis.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hottopics/lnacademic/?verb=sr&csi=222360&sr=AUTHOR(Rubinowitz)%2BAND%2BTITLE(THE+FAIR+HOUSING+ACT+AFTER+40+YEARS%3A+CONTINUING+THE+MISSION+TO+ELIMINATE+HOUSING

7 Leonard S. Rubinowitz and Kathryn Shelton, “The Fair Housing Act after 40 Years: Continuing theMission to Eliminate Housing Discrimination and Segregation: Non-Violent Direct Action and the Legislative Process: The Chicago Freedom Movement and the Federal Fair Housing Act” Indiana Law Review 41 Ind. L. Rev. 663 (2008): 9, accessed March 22, 2015, http://www.lexisnexis.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hottopics/lnacademic/?verb=sr&csi=222360&sr=AUTHOR(Rubinowitz)%2BAND%2BTITLE(THE+FAIR+HOUSING+ACT+AFTER+40+YEARS%3A+CONTINUING+THE+MISSION+TO+ELIMINATE+HOUSING

In March 1965, Father James Groppi was part of a group of Priests who went to Selma,

Alabama to participate in the mass march that followed Bloody Sunday. Groppi’s experience in

the Selma March influenced how the priest would create his own movement just two years later.

“According to (fellow Priest, Patrick) Flood, ‘[Selma was] the basis for Jim [Groppi] when he

came back, for the demonstrations [in Milwaukee], and for how to create a movement8.’”.

Unlike the southeastern United States, Milwaukee had a vibrant industrial base, with strong

organized labor. At times, there was tension between the unions and African Americans. Jones

mentions the example of a railroad workers strike in July 1922, when striking white workers

were replaced with blacks. A group of these black railroad workers were sleeping in boxcars in

the suburb of New Butler, they were attacked by a group of angry union workers who opened

fire on them9. While it is possible that anger over labor relations rather than race may have been

a factor, it was unusual for strikers to attack strikebreakers in such a fashion.

In an article "’Not a Color, but an Attitude’: Father James Groppi’s and Black Power

Politics in Milwaukee" Jones’ main arguments are that Father James Groppi, the Catholic Priest

and civil rights leader received criticism not just from whites, but from other black groups

because he was white, and that because this march was led by a white man that the civil rights

movement is not just about blacks, it is about everyone. In 1963 Father Groppi traveled to the

south, where he witnessed the racial discrimination there, but he also found that his fellow

Catholics, who were a minority in the south were working with the black community10. When

Groppi emerged as a civil rights leader, some of the Black Nationalist groups criticized him for

8 Patrick Jones, The Selma of the North: Civil Rights Insurgency in Milwaukee (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2009), 100.9 Patrick Jones, The Selma of the North: Civil Rights Insurgency in Milwaukee (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2009), 9.10 Patrick D. Jones, "’Not a Color, but an Attitude’: Father James Groppi and Black Power Politics in Milwaukee." Chap 11 in Groundwork: Local Black Freedom Movements in America 2005, edited by Jeanne F. Theoharis and Komozi Woodard, 2590281. New York: New York University Press, 2005. 263.

being white. For instance, one member of Pride Inc. claimed that “Father Groppi has only one

thing wrong with him, his color. It’s the same old case of whites using Negroes”11. In spite of

the critics, Groppi also had supporters, who felt that he was making the civil rights movement

friendlier to white people, such as Comedian Dick Gregory who said “What we are doing here in

Milwaukee is convincing a lot of cats that Black Nationalism is not a color, it’s an attitude”12.

Civil rights causes are important not only to the group that is being discriminated against, but to

everyone who believes in equality. A person does not have to be black to care about equal rights

for blacks. One of the important distinctions of the civil rights movement in Milwaukee is that it

did not pit blacks against whites, but civil rights supporters against civil rights opponents.

Margaret Rozga’s article “March on Milwaukee” talks about the tactics used by the marchers

in the Milwaukee marches. In 1962, Milwaukee Alderwoman Vel Phillips introduce a fair

housing bill before the city council13. While the bill was up for consideration, Father Groppi and

his commandos would peacefully picket in front of the homes of city council members with large

numbers of black constituents to urge them to support the bill14. In 1966, a black couple was not

allowed to rent a duplex, because the landlady was worried about what her neighbors would

think. Groppi and the Commandos sang Christmas carols for the landlady15.

The tactics mentioned by Rozga are to target people who are opposing civil rights

because of peer pressure. The landlady who refused to rent to the black couple did so not

11 Patrick D. Jones, "’Not a Color, but an Attitude’: Father James Groppi’s and Black Power Politics in Milwaukee." Chap 11 in Groundwork: Local Black Freedom Movements in America 2005, edited by Jeanne F. Theoharis and Komozi Woodard, 2590281. New York: New York University Press, 2005. 260.12 Patrick D. Jones, "’Not a Color, but an Attitude’: Father James Groppi;s and Black Power Politics in Milwaukee." Chap 11 in Groundwork: Local Black Freedom Movements in America 2005, edited by Jeanne F. Theoharis and Komozi Woodard, 2590281. New York: New York University Press, 2005. 261.13 Margarret Rozga, “March on Milwaukee,” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 90, no. 4 (2007): 30, accessed April 21, 2014, 31, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4637228.14 Margarret Rozga, “March on Milwaukee,” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 90, no. 4 (2007): 32, accessed April 21, 2014, 31, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4637228.15 Margarret Rozga, “March on Milwaukee,” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 90, no. 4 (2007): 31, accessed April 21, 2014, 31, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4637228.

because of her own personal feelings but because of what her neighbors would think. The

aldermen who had black constituents were more likely to be supportive of something that would

benefit the members of their districts.

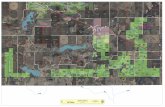

Stephen M. Leahy’s main argument of his article “Polish American Reaction to Civil Rights

in Milwaukee, 1963-1965” are that Polish Americans on Milwaukee’s south side, were less

likely to oppose civil rights and more likely to support them than other whites in the city and

suburbs. The author examines letters that were sent from constituents of Congressmen Clement

Zablocki and Henry Reuss and Mayor Henry W. Maier, and classifies them as either pro or anti

civil rights, and then plots them onto a map using the letter’s return address. The results are that

the predominantly Polish-American neighborhood in which the Milwaukee civil rights marches

took place, had a higher rate of support for and a lower rate of opposition to civil rights than

most of the rest of the city. Another map shows that there is a much higher opposition in

Wauwatosa16. Another map shows letters from this neighborhood that mention segregationist

Presidential hopeful George Wallace tend to be pro civil rights17.

Chicago Freedom Movement

On the night of May 26, 1966, the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. announced that on

June 26, he would be leading a rally at Soldier Field in Chicago followed by a march to

Chicago’s City Hall, where he would present Mayor Richard J. Daley with a list of demands for

16 Leahy, Stephen M. “Polish American Reaction to Civil Rights in Milwaukee, 1963-1965.” Polish American Studies 63, no. 1 (2006): 35-56, accessed March 22, 2015, 52, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20148739.17 Leahy, Stephen M. “Polish American Reaction to Civil Rights in Milwaukee, 1963-1965.” Polish American Studies 63, no. 1 (2006): 35-56, 48, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20148739.

policies to improve the lives of Chicago’s African Americans18 19. In the event the mayor was

not present King said, “If the mayor isn’t just in that Sunday, we’ll tack them (the demands) on

the City hall door”20. King also vowed “Chicago will have a long hot summer, but not a summer

of racial violence. Rather it will be a summer of peaceful non-violence”21.

Although eight neighborhood groups were invited to participate in the marches, only one,

The West Side Federation, pledged to actively participate22. While the other groups were

supportive of the marches, but felt that marching was not a productive solution. Midwest

Community Council director F. Adrian Robson said “We have been working on west side

problems 20 years, and we do not feel that demonstrations get things done”23. Mile Square

Federation President Clifford Burke called for further negotiations between the civil rights

groups and City Hall24. West Garfield Community Council member William von Roedher was

concerned that “The least little thing could ignite a conflagration in this neighborhood which was

the scene of last summer’s riots”25. The Reverend Dr. Joseph H. Jackson, president of the

18 “King Discloses Plan for Rally, March on City Hall on June 26,” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file) (Chicago, IL), May 27, 1966, 1; ; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/178966972/24352BF1BF564ABDPQ/1?accountid=1507819 “King and Daley to Talk in City Hall Monday,” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file) (Chicago, IL), July 9, 1966, page 7; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179027847/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/17?accountid=1507820 “King Discloses Plan for Rally, March on City Hall on June 26,” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file) (Chicago, IL), May 27, 1966, page 1; ;http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/178966972/24352BF1BF564ABDPQ/1?accountid=1507821 “King Discloses Plan for Rally, March on City Hall on June 26,” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file) (Chicago, IL), May 27, 1966, page 1; ; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/178966972/24352BF1BF564ABDPQ/1?accountid=15078

22 ? “Only One Group to Join Dr. King’s Rally, March.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), June 12, 1966, page K6; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179007103/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/15?accountid=15078

23 ”Only One Group to Join Dr. King’s Rally, March,” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file) (Chicago, IL), June 12, 1966, page K6; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179007103/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/15?accountid=1507824 ”Only One Group to Join Dr. King’s Rally, March,” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file) (Chicago, IL), June 12, 1966, page K6; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179007103/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/15?accountid=1507825 ”Only One Group to Join Dr. King’s Rally, March,” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file) (Chicago, IL), June 12, 1966, page K6; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179007103/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/15?accountid=15078

National Baptist Convention, U.S.A., Inc. claimed “that it is not enough to call together large

crowds of people to be used in demonstration and as pressure group”26.

On July 1, at a convention in Baltimore, The Congress of Racial Equality had proposed

the idea of abandoning their policy of non-violence in exchange for a policy of self-defense27.

King, who was scheduled to speak at the conference, cancelled his appearance, claiming that he

had forgotten about a previous engagement28. King held to his stance on nonviolence, stating on

July 9, “If I were not morally against violence, I would be against it practically”29.

The rally and march originally scheduled for July 26 were actually held on July 10. At

the rally, King reiterated his commitment to nonviolence, “Our power does not reside in Molotov

cocktails, rifles, knives, and bricks”30. King and Albert A. Raby of the Coordinating Council of

Community Organizations made good on their promise and singed the list of demands and taped

them to the entrance of city hall31. At the Soldier Field Rally, police estimated 30,000 were in

26 ”Negro Baptist Leader Balks At King Rally,” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file) (Chicago, IL), July 7, 1966, page A3; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179038193/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/19?accountid=1507827 “C.O.R.E. Asked To Abandon Nonviolence: King Cancels Speech to Convention,” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file) (Chicago, IL), July 2, 1966, page 15; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179024652/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/29?accountid=1507828 “C.O.R.E. Asked To Abandon Nonviolence: King Cancels Speech to Convention,” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file) (Chicago, IL), July 2, 1966, page 15; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179024652/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/29?accountid=1507829 “King and Daley to Talk in City Hall Monday,” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file) (Chicago, IL), July 9, 1966, page 7; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179027847/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/17?accountid=1507830 “Thousands Go to Soldiers’ Field Rights Rally: King Speaks to 30,000 at Rights Rally: Tells His Aims for Chicago,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 11, 1966, page 2; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179011513/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/30?accountid=1507831 “King Tells Goals; March on City Hall,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 11, 1966, page 1; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179031147/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/4?accountid=15078

attendance, while King estimated a number of 65,00032 33. Police estimated 5,000 people

participated in the march that followed the rally, while march organizers came up with a much

larger figure, 80% of those who attended the rally were claimed to have participated in the

march34. There may have been even more trying to get to the rally, as an announcement made

over the public address system said that there were several busses “backed up for miles along the

Outer Drive”35.

On July 8, Mayor Richard J. Daley announced he would meet with Dr. King the

following Monday at Chicago City Hall to discuss problems in the city. The mayor said he was

going to tell King about the progress Chicago had made in dealing with problems such as slums,

jobs, and education36. On July 12, the day after the rally and march, King and Daley met at city

hall for three hours to discuss racial issues, in a meeting that left both sides disappointed. King

was disappointed by a lack of specific solutions, and threatened to hold more marches, while

Daley claimed has asked King and his aides what they wanted him to do, and could not get a

32 “Thousands Go to Soldiers’ Field Rights Rally: King Speaks to 30,000 at Rights Rally: Tells His Aims for Chicago,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 11, 1966, page 1; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179011513/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/30?accountid=1507833 “30,000 Hear Dr. King At Soldier Field Rally: 98 Degree Temperature Fails To Prevent Huge Turn-Out,” Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973) (Chicago, IL), Jul. 11, 1966, page 3; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagodefender/docview/494253431/A95E856C11B043D4PQ/9?accountid=1507834 “King Tells Goals; March on City Hall: Posts 14 Demands for Daley on Door: Fill State Street From Curb To Curb,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 11, 1966, page 1; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179031147/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/4?accountid=1507835 “30,000 Hear Dr. King At Soldier Field Rally: 98 Degree Temperature Fails To Prevent Huge Turn-Out,” Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973) (Chicago, IL), Jul. 11, 1966, page 3; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagodefender/docview/494253431/A95E856C11B043D4PQ/9?accountid=1507836 “King and Daley to Talk in City Hall Monday,” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file) (Chicago, IL), July 9, 1966, page 7; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179027847/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/17?accountid=15078

direct answer37 38. According to King, they discussed the demands that had posted on the door to

city hall, and while Daley was sympathetic, he was also vague and made no commitments39 40.

King said he didn’t think Daley understood how bad the problems were, but that he did not think

they mayor was a bigot41. King also claimed that city employees were being intimidated to

prevent them from participating in the marches and that the city government was strategically

granting minor concessions to the African American community just enough to undermine the

civil rights movement42. When asked about statements King had made about filling Chicago’s

jails with civil rights activists for the cause, Daley said that he would not tolerate illegal activity,

but “I don’t think Dr. King would violate any law. He said he was not for violence”43.

On the nights following the rally and march, the west side of Chicago erupted into civil

unrest, which Mayor Daley blamed on outside influences, particularly the Southern Christian

37 “Daley, King, Aids, Meet on Rights: Protesters Not Satisfied With Results, Threaten Many More Marches,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 12, 1966, page 1; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179018292/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/7?accountid=1507838 Betty Washington, “Dr. King, Mayor Daly Lock Horns On ‘Open City’ Issue,” Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973) (Chicago, IL), Jul. 12, 1966, page 1; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagodefender/docview/494214109/A95E856C11B043D4PQ/7?accountid=1507839 “Daley, King, Aids, Meet on Rights: Protesters Not Satisfied With Results, Threaten Many More Marches,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 12, 1966, pages 1-2; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179018292/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/7?accountid=1507840 Betty Washington, “Dr. King, Mayor Daly Lock Horns On ‘Open City’ Issue,” Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973) (Chicago, IL), Jul. 12, 1966, page 1; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagodefender/docview/494214109/A95E856C11B043D4PQ/7?accountid=1507841 “Daley, King, Aids, Meet on Rights: Protesters Not Satisfied With Results, Threaten Many More Marches,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 12, 1966, page 2; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179018292/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/7?accountid=1507842 Betty Washington, “Dr. King, Mayor Daly Lock Horns On ‘Open City’ Issue,” Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973) (Chicago, IL), Jul. 12, 1966, page 1; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagodefender/docview/494214109/A95E856C11B043D4PQ/7?accountid=1507843 “Daley, King, Aids, Meet on Rights: Protesters Not Satisfied With Results, Threaten Many More Marches,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 12, 1966, page 1; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179018292/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/7?accountid=15078

Leadership Council44. Daley also called out the National Guard, and met with King where they

reached an agreement on five steps that would taken by the city to calm the tensions, including

putting sprinkler heads of fire hydrants, building more swimming pools and ensuring that

everyone has equal access to them, and a citizen council focused on relations between the police

and civilians45.

Several African American community leaders were also critical of King and the SCLC’s

presence. The Reverend Dr. Joseph H. Jackson, echoed Daley’s sentiment “I believe our young

people are not vicious enough to attack a whole city, some other forces are using these young

people”46. Jackson also said at a press conference that the city was taking care of its own

problems47. Chicago Committee of One Hundred President, Ernest E. Rather said that the

SCLC’s presence was not helpful, and that even their non-violent message could indirectly lead

to violence48. King later denied that the SCLC’s influence had anything to do with the riot,

claiming that the accusers were making those claims to direct attention from the real issues of

racial injustice, and said of those who committed the violence “Violence is but an expression of

44 “Dr. Jackson Joins Archbishop in Peace Plea, Daley Links Outsiders to Lawlessness: Rev. Jackson, Cody Ask for Peace,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 16, 1966, page A1; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179003765/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/21?accountid=1507845 “Dr. Jackson Joins Archbishop in Peace Plea, Daley Links Outsiders to Lawlessness: Rev. Jackson, Cody Ask for Peace,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 16, 1966, page A2; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179003765/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/21?accountid=1507846 “Dr. Jackson Joins Archbishop in Peace Plea, Daley Links Outsiders to Lawlessness: Rev. Jackson, Cody Ask for Peace,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 16, 1966, pages A1-A2; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179003765/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/21?accountid=1507847 Bety Washington, “Dr. King, Rev. Jackson Air Differences: Chicago Rallies Is A Thorny Issue,” Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973) (Chicago, IL), Jul. 7, 1966, page 4; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagodefender/docview/494231836/A95E856C11B043D4PQ/12?accountid=1507848 “Chicago Negro Urges King to Return South,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 22, 1966, page 5; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179016361/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/20?accountid=15078

his personal life. No wonder it appears logical for him to strike out and return violence against

his oppressor”49.

On August 5, events took a more violent turn when King led an open housing march at

Marquette Park. Several of the participants had been demonstrating in front of some nearby real

estate offices for hours without incident prior to King’s arrival50. As King was walking from his

car to join the group, he was hit by a rock, and then white onlookers began throwing other

projectiles at the protesters51. There were about 700 marchers, who were being protected by

approximately 1,200 police officers, from a crowd of about 4,000 mostly white counter

protesters52. The police did try to maintain order, arresting those who became violent or threw

projectiles53. A nearby car was overturned and others damaged54. The march resulted in 30

people being injured and 41 being arrested55.

However, Kale Williams, Executive Secretary of American Friends Service Committee,

Inc. complained in a letter to Chicago Police Superintendent Wilson that the police had been lax

in their duties of protecting the marchers in another march the previous weekend in Gage Park.

Williams claimed that police made little effort to restrain counter protesters, enforce laws against

49 “Freedom Movement a Riot Remedy: King,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 22, 1966, page 5; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179010838/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/3?accountid=1507850 http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179045023/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/9?accountid=1507851 “Dr. King Is Felled by Rock: 30 Injured As He Leads Protesters, Many Arrested in Race Clash.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Aug. 6, 1966, page 2; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179045023/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/9?accountid=1507852 “Dr. King Is Felled by Rock: 30 Injured As He Leads Protesters, Many Arrested in Race Clash.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Aug. 6, 1966, page 2; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179045023/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/9?accountid=1507853 “Dr. King Is Felled by Rock: 30 Injured As He Leads Protesters, Many Arrested in Race Clash.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Aug. 6, 1966, page 2; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179045023/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/9?accountid=1507854 “Dr. King Is Felled by Rock: 30 Injured As He Leads Protesters, Many Arrested in Race Clash.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Aug. 6, 1966, page 2; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179045023/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/9?accountid=1507855 “Dr. King Is Felled by Rock: 30 Injured As He Leads Protesters, Many Arrested in Race Clash.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Aug. 6, 1966, page 1; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179045023/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/9?accountid=15078

throwing projectiles, and protect protesters leaving the area, and that several cars in the

neighborhood were vandalized56.

An August 18 Chicago Tribune article, titled “The Sabotage of Chicago” accused King

and his followers of overtaxing Chicago’s police resources, by holding too many marches in too

many places with too little advanced warning, which tied up too many police, leading to a 25%

increase in the city’s crime rate57. The city of Chicago was granted an injunction that limited

King’s marches to 500 people per march, due to the increasing difficulty of providing protection,

and the lack of information provided to the police by march organizers58. When King announced

plans to expand the marches beyond the Chicago city limits into the suburbs, Cook County

Sheriff, Richard B, Ogilvie, sought a similar injunction on a countywide basis due to concerns

that suburban police departments would face the same problems59.

On August 22, Mayor Daley condemned hate groups such as the Ku Klux Klan and the

American Nazi Party for their presence in the city, but stopped short of including civil rights

advocates in this group60. When asked about open housing, the mayor said he believed people

had a constitutional right to live wherever they want, but he did not foresee any rapid integration

56 The Response of the Chicago Freedom Movement to Attacks on Open-Housing Demonstrators. Chicago Freedom Movement: Fulfilling the Dream (1966). Middlebury College, http://sites.middlebury.edu/chicagofreedommovement/files/2013/07/Response_to_Attacks_Open_Housing.pdf57 “The Sabotage of Chicago,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Aug. 18, 1966, page 22; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179036314/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/23?accountid=1507858 “King Assails Ruling; Says He May Ignore It,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Aug. 20, 1966, page B5; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179024883/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/1?accountid=15078

59 ? “Ogilvie Says He Will Seek an Injunction: 20 Arrested During March On S.E. Side,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Aug. 22, 1966, page 1; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179018547/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/34?accountid=15078

60 ? “Daley Blasts ‘Hate Groups’ Invading City,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Aug. 23, 1966, page 1; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179027447/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/24?accountid=15078

of white neighborhoods in the city61. When the city reached a housing agreement with King,

several neighborhood associations from white neighborhoods called on the mayor to protest the

agreement62.

Milwaukee Open Housing Marches

In a June 19, 2007 interview, Margaret (Peggy) Rozga, who participated in the first open

housing march to Kosciuszko Park on August 28, 1967, recalled their being 150-200 participants

in the march, and being confronted by an angry mob of at least 5,000 protesting the march63.

When the marchers arrived at the park, the police asked Father Groppi to conclude the

demonstration as quickly as possible, because the police would not be able to hold back the

counter demonstrators much longer64.

At a press conference on Tuesday, August 29, 1967, the night after the first march, Father

Groppi announced that the NAACP Youth Council would be marching again along the same

route in spite of being denied a permit to use Kosciuszko Park65. Groppi also stated that the

group would march regardless of whether the mayor called out the National Guard or not, and

that if the mayor failed to call out the national guard and anyone got hurt, their blood would be

61 “Daley Blasts ‘Hate Groups’ Invading City,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Aug. 23, 1966, page 2; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179027447/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/24?accountid=1507862 “White Groups Protest Open Housing Pact: Ask for Meeting with Mayor Daley,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Aug. 29, 1966, page A8; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179029347/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/31?accountid=1507863 Oral History Interview with Margaret (Peggy) Rozga, June 19, 2007. The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/march/id/1659/rec/2464 Oral History Interview with Margaret (Peggy) Rozga, June 19, 2007. The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/march/id/1659/rec/2465 News Film Clip of a Press Conference with Father Groppi and NAACP Youth Council Commandos Announcing the Second Fair Housing March, August 29, 1967. The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/ref/collection/wtmj/id/46

on the mayor’s hands66. Father Groppi accused the mayor of using a double standard when

deciding when to call out the National Guard, referencing the Mayor’s speedy dispatch of the

National Guard to disturbances on July 30-31, and his failure to dispatch them to protect the

open housing marches67.

That night, the Milwaukee Police fired teargas into the Youth Council’s headquarters, the

Freedom House, resulting in a fire that caused extensive damage. Groppi noted that during the

earlier disturbances, the mayor called out the National Guard, when a few black people were

rioting, but only called for a voluntary curfew when the marchers were being attacked by white

mobs68. Maier’s response to pass the buck to Governor Warren P. Knowles, stating “The

governor can call the guard any time he wants. I personally think that the guard at this time

would be provocative. But Gov. Knowles can at least shoulder a responsibility instead of second

guessing me”69. For his part, the governor reached out to a diverse group of Milwaukee’s

community leaders including African American leaders and Father Groppi’s boss, Archbishop

William Cousins to act as mediators between Groppi and Maier70.

One factor that always contributes to public perception is media coverage. While

coverage of Bull Connor’s police force in Birmingham turning fire hoses and police dogs

garnered national television coverage, even local coverage of white mob violence against the

66 News Film Clip of a Press Conference with Father Groppi and NAACP Youth Council Commandos Announcing the Second Fair Housing March, August 29, 1967. The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/ref/collection/wtmj/id/4667 “Maier Lifts March Curbs, Vows Police Will Do Duty.” Milwaukee Journal (Milwaukee, WI), Sept. 1, 1967. 13. https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1499&dat=19670901&id=2wIqAAAAIBAJ&sjid=7icEAAAAIBAJ&pg=7558,75689&hl=en68 News Film Club (partial) of an Interview with Father Groppi and the Commandos After the Burning of the Freedom House, August 30, 1967. The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/ref/collection/wtmj/id/5369 “Maier Lifts March Curbs, Vows Police Will Do Duty.” Milwaukee Journal (Milwaukee, WI), Sept. 1, 1967. 12. https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1499&dat=19670901&id=2wIqAAAAIBAJ&sjid=7icEAAAAIBAJ&pg=7558,75689&hl=en70 “Maier Lifts March Curbs, Vows Police Will Do Duty.” Milwaukee Journal (Milwaukee, WI), Sept. 1, 1967. 12. https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1499&dat=19670901&id=2wIqAAAAIBAJ&sjid=7icEAAAAIBAJ&pg=7558,75689&hl=en

protestors was lacking. Father Groppi criticized the media for their double standard in their

coverage of events, saying the media had given very intense coverage to the Milwaukee riots in

late July, but little to no coverage of the mobs attacking the marchers71.

On Wednesday, August 30, 1967, Mayor Maier gave an order banning marches and

demonstrations in the city at night time that was to be in effect for 30 days. On Friday,

September 1, just 2 days later, the mayor rescinded the order. In his statement to the media,

Maier appealed to the media to “not publicize the advance plan of the march as though it were

the Fourth of July Parade”72. Maier also appealed to citizens to avoid partaking in mob violence

saying, “While the mob may think it is opposing Father Groppi, it is helping him in his desire to

injure Milwaukee’s good name”73.

In a letter from Mayor Maier to the Milwaukee Common Council dated September 5,

1967, Maier talks about efforts to form a countywide cooperation council, consisting of all of the

mayors and village presidents from Milwaukee County74. In this letter Maier advocates for

turning over several city services to the county to alleviate Milwaukee’s tax burden75. He also

states that he would be in favor of amongst other things, a countywide open housing law and

additional parks and greenspaces in the inner city76. Maier further illustrates this sentiment in a

telegram to NAACP National Chairman Roy Wilkins which reads in part “Can’t believe the 71 News Film Clip of a Press Conference with Father Groppi and NAACP Youth Council Commandos Announcing the Second Fair Housing March, August 29, 1967. The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/ref/collection/wtmj/id/4672 Maier Administration, Box 148, Folder 5, Press Releases and Statements, 1967, September (Selections). The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, p. 1-1. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/march/id/1001/rec/31.73 Maier Administration, Box 148, Folder 5, Press Releases and Statements, 1967, September (Selections). The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, p. 1-1. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/march/id/1001/rec/31.74 Maier Administration, Box 148, Folder 5, Press Releases and Statements, 1967, September (Selections). The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, p. 2-1.75 Maier Administration, Box 148, Folder 5, Press Releases and Statements, 1967, September (Selections). The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, p. 2-1.76 Maier Administration, Box 148, Folder 5, Press Releases and Statements, 1967, September (Selections). The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, p. 2-1. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/march/id/1001/rec/31

NAACP is for law which covers one side of street and not the other, the poor and not the rich,

the central city and not the suburbs”77. Father Groppi’s response to Maier’s position on a

countywide level was that he agreed with the mayor on the countywide fair housing ordinance,

but called on him to act at the municipal level instead of trying to pass the buck to higher levels

of government78.

The lack of progress and violence took a toll on Father Groppi and his Commandos, and

tested their commitment to non-violence. Groppi stated that his group of Commandos was non-

violent with the sole exception of self-defense79. On Thursday, September 28, at a two day

conference on churches and urban tension in Washington DC, Father Groppi stated that his

movement was considering putting an end to their non-violent approach. Groppi said that he had

grown weary of the lack of progress his non-violent movement had achieved and had talked with

militants at the event and had convinced him that violence could get results80.

Another gauge of public sentiment is letters written by people about issues. One hate

letter sent to Father Groppi by an anonymous south side resident expressed racist sentiments

“We don’t want any niggers down here” and “The south side is for whites only”81. Another hate

letter from an anonymous teacher sent the day after the first march claimed Groppi was forsaking

77 Maier Administration, Box 148, Folder 5, Press Releases and Statements, 1967, September (Selections). The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, p. 4. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/march/id/1001/rec/3178 News Film Clip of a Press Conference with Father Groppi and NAACP Youth Council Commandos Announcing the Second Fair Housing March, August 29, 1967. The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/ref/collection/wtmj/id/4679 News film clip of Father Groppi at the Unitarian Church West Summarizing the Struggle for Open Housing in Milwaukee, September 20, 1967. The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/ref/collection/wtmj/id/3980 John W. Kole, “Militant Negroes Attack Groppi’s Stand On Rights.” Milwaukee Journal (Milwaukee, WI), Sept. 29, 1967. 1. https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1499&dat=19670928&id=WD0aAAAAIBAJ&sjid=-ycEAAAAIBAJ&pg=7353,4974186&hl=en81 Groppi Papers, Box 8, Folders 3-6, Correspondence, Hate Mail, 1967 (selections) The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, p. 2. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/march/id/715/rec/28

his race82. There were also letters of support. Leonard Mills, a white Marine from Milwaukee

expressed shame for his city due to the white mob violence and pride in Father Groppi for taking

a stand83.

According to J. A. Slesinger’s “Community Opinions of the Summer 1967 Civil

Disturbance in Milwaukee”, a survey of 387 randomly chosen Milwaukee County residents

published in 1968, 90 percent of black residents favored a city open housing law, with 4 percent

opposed; 43 percent of inner city whites were in favor and 34 percent opposed; 43 percent of

outer city whites were in favor, and 44 percent were opposed; 58 percent of suburban whites

were in favor, while 29 percent were opposed84. The same survey asked about a countywide open

housing law, to which 85 percent of blacks were in favor and 6 percent were opposed; 52 percent

of inner city whites were in favor, while 22 percent were opposed, 42 percent of outer city whites

were in favor, and 43 percent opposed, and 59 percent of suburban whites were in favor, while

31 percent were opposed85. A third question was asked as to whether the efforts to secure open

housing are going. 0 percent of blacks though it was going too fast, 12 percent thought it was

about right, and 78 percent thought it was going too slow; 19 percent of inner city whites thought

it was going too fast, 53 percent thought it was about right, and 16 percent thought it was going

too slow; 9 percent of outer city whites thought it was going too fast, 60 percent thought it was

just right, and 20 percent thought it was too slow, while 11 percent of suburban whites thought it

82 Groppi Papers, Box 8, Folders 3-6, Correspondence, Hate Mail, 1967 (selections) The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, p. 4. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/march/id/715/rec/2883 Groppi Papers, Boxes 1-4, Correspondence, Support Mail, 1966-1967 (selections) The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, p. 5-1 – 5-3. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/march/id/935/rec/2984 Slesinger, Jonathan A. “Study of Community Opinions Concerning the Summer of 1967 Civil Disturbance in Milwaukee.” Study, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1968. 18-19. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/march/id/852/rec/185 Slesinger, Jonathan A. “Study of Community Opinions Concerning the Summer of 1967 Civil Disturbance in Milwaukee.” Study, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1968. 18-19. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/march/id/852/rec/1

was going too fast, 54 percent thought it was just right, and 27 percent thought it was going too

slow86. This indicates that the highest support for open housing came from blacks, but the

highest white support came from the suburbs. Inner city whites also favored a countywide

ordinance over a city ordinance.

Discussion and Analysis

While the north did not have the de jure practice of Jim Crow Segregation, its

neighborhoods were racially segregated. This was because of the long established

neighborhoods in the older, industrial, cities of the north. The south had had a substantial

African American population since before the American Revolution, and since slavery ended in

1865, they had settled into the same neighborhoods as whites.

In Chicago, the administration of Mayor Richard J. Daley was implementing programs to

improve living conditions in African American neighborhoods, but was not fully addressing the

underlying causes of residential segregation. His counterpart in Milwaukee, Mayor Henry W.

Maier was more resistant to pass a local open housing ordinance, as was the city council. Mayor

Maier passed the buck on to higher levels of government, such as the county, the state, and the

federal government. He did not want a law at the local level that would be different from what

the neighboring suburbs had. Both mayors were quick to call out the National Guard if blacks

rioted, but reluctant to do so when they were targeted by white mobs.

While police in the Alabama cities of Selma and Birmingham personally sicked attack

dogs and turned fire hoses on non-violent protesters, in both Chicago and Milwaukee, the police

did their duty to protect the marchers, although at times were overwhelmed by angry, white,

86 Slesinger, Jonathan A. “Study of Community Opinions Concerning the Summer of 1967 Civil Disturbance in Milwaukee.” Study, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1968. 18-19. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/march/id/852/rec/1

counter protesters. In Chicago, the police got injunctions limiting the number of people allowed

to participate in a march, citing the overburdening of police resources, and police being spread to

thin to fight crime in other parts of the city. In Milwaukee, the Mayor banned night marching

due to violence that the police were unable to contain, but relented after 2 days.

The disturbing scenes of police brutality ordered by Bull Connor against the non-violent

demonstrators in Birmingham, Alabama were splashed across television screens across the

country, while even local media coverage in the north was often lacking. Coverage in

Milwaukee focused extensively on violence committed by African Americans in the July 1967

riots, but gave hardly any coverage to white mobs attacking peaceful demonstrators on the south

side.

While many northern residents were in favor of open housing, many others waged angry,

and often violent opposition to it. Letters sent by residents to Father Groppi and local elected

officials in Milwaukee showed mixed opinion, with some in opposition, but many others in

support. It’s as if there was an ignorant NIMBY (not in my back yard) sentiment about it, where

many people were in favor of it, as long as it was in someone else’s neighborhood. When it

came to their doorstep, they succumbed to fear and prejudice. In Milwaukee, the most

opposition to the open housing ordinances came from whites in the city, while suburbanites who

were not dealing with open housing conflicts in their own neighborhoods were more in favor.

White city residents were more in favor of a countywide open housing ordinance than one for

just the city.

In the south, most of the protesters were committed to non-violence, while in the north

many marchers, were willing to defend themselves if attacked. While civil rights leaders in the

south at least had the support of most of the African American community, in the north the met

with opposition. In Chicago, Dr. Martin Luther King could only get 1 of the 8 groups he invited

to his rally and march to participate, and was criticized by other African American community

leaders. In Milwaukee Father James Groppi was criticized by blacks and whites alike for being

the white leader of a black movement.

Conclusion

While formal segregation may not have existed in the north like it did in the Jim Crow

South, residential segregation did persist in the north. The civil rights movements addressed

northern segregation just like they did with southern segregation. Today elementary school

children across America learn history about Martin Luther King and his civil rights movement in

the south, but unless they live in Chicago or Milwaukee, they probably don’t hear about the

Chicago Freedom March, or James Groppi’s NAACP Youth Council.

In 1968, the year after the Milwaukee marches, and 2 years after the Chicago marches,

Congress passed the fair housing act, putting the issue of any type of residential segregation to

rest throughout the country. Unfortunately, many neighborhoods in Milwaukee and Chicago still

appear racially segregated today. However, it is no longer due to homeowners refusing to sell or

landlords refusing to rent to African Americans. It is due mainly to generations of poverty that

disproportionately affects African Americans. They simply can’t afford to move to a nicer

neighborhood. Perhaps someday, a new generation of civil rights activists will address this

issue.

Word Count: 5392

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Primary Sources:

“30,000 Hear Dr. King At Soldier Field Rally: 98 Degree Temperature Fails To Prevent Huge Turn-Out.” Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973) (Chicago, IL), Jul. 11, 1966, page 3; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagodefender/docview/494253431/A95E856C11B043D4PQ/9?accountid=15078

“Chicago Negro Urges King to Return South.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 22, 1966, page 5; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179016361/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/20?accountid=15078

“C.O.R.E. Asked To Abandon Nonviolence: King Cancels Speech to Convention.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 2, 1966, page 15; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179024652/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/29?accountid=15078

“Daley Blasts ‘Hate Groups’ Invading City.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Aug. 23, 1966, pages 1-2; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179027447/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/24?accountid=15078

“Daley, King, Aids, Meet on Rights: Protesters Not Satisfied With Results, Threaten Many More Marches.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 12, 1966, page 1; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179018292/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/7?accountid=15078

“Dr. Jackson Joins Archbishop in Peace Plea, Daley Links Outsiders to Lawlessness: Rev. Jackson, Cody Ask for Peace.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 16, 1966, pages A1-A2; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179003765/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/21?accountid=15078

“Dr. King Is Felled by Rock: 30 Injured As He Leads Protesters, Many Arrested in Race Clash.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Aug. 6, 1966, pages 1-3; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179045023/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/9?accountid=15078

“Freedom Movement a Riot Remedy: King.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 22, 1966, page 5; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179010838/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/3?accountid=15078

Groppi Papers, Box 8, Folders 3-6, Correspondence, Hate Mail, 1967 (selections) The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/march/id/715/rec/28

Groppi Papers, Boxes 1-4, Correspondence, Support Mail, 1966-1967 (selections) The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/march/id/935/rec/29

“King and Daley to Talk In City Hall Monday.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 9, 1966, page 7; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179027847/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/17?accountid=15078

“King Assails Ruling; Says He May Ignore It,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Aug. 20, 1966, pages B1 and B5; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179024883/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/1?accountid=15078

“King Discloses Plan for Rally, March on City Hall on June 26.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file); (Chicago, IL), May 27, 1966, page 1; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/178966972/24352BF1BF564ABDPQ/1?accountid=15078

“King Tells Goals; March on City Hall: Posts 14 Demands for Daley on Door: Fill State Street From Curb To Curb.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 11, 1966, page 1; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179031147/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/4?accountid=15078

Kole, John W. “Militant Negroes Attack Groppi’s Stand on Rights,” Milwaukee Journal (Milwaukee, WI), Sept. 29, 1967.

Maier Administration, Box 148, Folder 5, Press Releases and Statements, 1967, September(Selections). The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/march/id/1001/rec/31

“Maier Lifts March Curbs, Vows Police Will Do Duty.” Milwaukee Journal (Milwaukee, WI), Sept. 1, 1967. https://news.google.com/newspapers?

nid=1499&dat=19670901&id=2wIqAAAAIBAJ&sjid=7icEAAAAIBAJ&pg=7558,75689&hl=en

“Negro Baptist Leader Balks At King Rally.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 7, 1966, page A3; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179038193/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/19?accountid=15078

News film clip of Father Groppi at the Unitarian Church West Summarizing the Struggle forOpen Housing in Milwaukee, September 20, 1967. The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/ref/collection/wtmj/id/39

News Film Clip of a Press Conference with Father Groppi and NAACP Youth CouncilCommandos Announcing the Second Fair Housing March, August 29, 1967. The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/ref/collection/wtmj/id/46

News Film Clip (partial) of an interview with Father Groppi and the Commandos After theBurning of the Freedom House, August 30, 1967. The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/ref/collection/wtmj/id/53

“Ogilvie Says He Will Seek an Injunction: 20 Arrested During March On S.E. Side,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Aug. 22, 1966, pages 1-2; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179018547/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/34?accountid=15078

“Only One Group to Join Dr. King’s Rally, March.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), June 12, 1966, page K6; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179007103/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/15?accountid=15078

Slesinger, Jonathan A. “Study of Community Opinions Concerning the Summer of 1967 CivilDisturbance in Milwaukee.” The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project. University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. Study, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1968. http://collections.lib.uwm.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/march/id/852/rec/1

The Response of the Chicago Freedom Movement to Attacks on Open-Housing Demonstrators.Chicago Freedom Movement: Fulfilling the Dream (1966). Middlebury College, http://sites.middlebury.edu/chicagofreedommovement/files/2013/07/Response_to_Attacks_Open_Housing.pdf

“The Sabotage of Chicago.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Aug. 18, 1966, page 22; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179036314/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/23?accountid=15078

“Thousands Go to Soldiers’ Field Rights Rally.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Jul. 11, 1966, page 1; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179011513/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/30?accountid=15078

Washington, Bety “Dr. King, Rev. Jackson Air Differences: Chicago Rallies Is a Thorny Issue.” Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973) (Chicago, IL), Jul. 7, 1966, page 4; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagodefender/docview/494231836/A95E856C11B043D4PQ/12?accountid=15078

Washington, Betty. “Dr. King, Mayor Daly Lock Horns On ‘Open City’ Issue.” Chicago Daily Defender (Chicago, IL), Jul. 12, 1966, page 1; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagodefender/docview/494214109/A95E856C11B043D4PQ/7?accountid=15078

“White Groups Protest Open Housing Pact: Ask for Meeting with Mayor Daley.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Aug. 29, 1966, page A8; http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hnpchicagotribune/docview/179029347/F1089ACA03C64121PQ/31?accountid=15078

Secondary Sources:

Jones, Patrick. The Selma of the North: Civil Rights Insurgency in Milwaukee. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2009.Jones, Patrick D. "’Not a Color, but an Attitude’: Father James Groppi’s and Black Power

Politics in Milwaukee." Chap 11 in Groundwork: Local Black Freedom Movements in America 2005, edited by Jeanne F. Theoharis and Komozi Woodard, 2590281. New York: New York University Press, (2005): 259-281.

Leahy, Stephen M. “Polish American Reaction to Civil Rights in Milwaukee, 1963-1965.” Polish American Studies 63, no. 1 (2006): 35-56, accessed March 22, 2015, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20148739

Rubinowitz, Leonard S. and Kathryn Shelton. “The Fair Housing Act After 40 Years:Continuing the Mission to Eliminate Housing Discrimination and Segregation: Non-Violent Direct Action and the Legislative Process: The Chicago Freedom Movement and the Federal Fair Housing Act” Indiana Law Review 41 Ind. L. Rev. 663 (2008): 1-65, accessed March 22, 2015, http://www.lexisnexis.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/hottopics/lnacademic/?verb=sr&csi=222360&sr=AUTHOR(Rubinowitz)%2BAND%2BTITLE(THE+FAIR+HOUSING+ACT+AFTER+40+YEARS%3A+CONTINUING+THE+MISSION+TO+ELIMINATE+HOUSING+DISCRIMINATION+AND+SEGREGATION%3A+Non-Violent+Direct+Action+and+the+Legislative+Process%3A+The+Chicago+Freedom+Movement+and+the+Federal+Fair+Housing+Act)%2BAND%2BDATE%2BIS%2B2008

Rozga, Margaret. “March on Milwaukee.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 90, no. 4 (2007): 28-39, accessed April 21, 2014, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4637228

![Crow Indians. [Crow Indian camp]. Metadata for:](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/56649cee5503460f949bc20c/crow-indians-crow-indian-camp-httpmtmemoryorgcdmrefcollectionp267301coll3id2445item.jpg)