Factors inn¼éuencing the intention to revisit a cultural attraction

-

Upload

francesca-gheran -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

0

Transcript of Factors inn¼éuencing the intention to revisit a cultural attraction

-

8/12/2019 Factors innuencing the intention to revisit a cultural attraction

1/8

Journal of Cultural Heritage 13 (2012) 167174

Original article

Factors influencing the intention to revisit a cultural attraction: The case study ofthe Museum ofModern and Contemporary Art in Rovereto

Juan G. Brida , Marta Meleddu , Manuela Pulina

Free University of Bolzano, PiazzadellUniversit, 1, Bolzano, Italy

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 18 April 2011

Accepted 5 August 2011Available online 2 October 2011

JEL classification:

C19

D12

L83

Keywords:

Cultural economics

Museum

Repeat visitationZero-truncated Poisson

Policy implications

a b s t r a c t

This paper analyses the different factors influencing the intention to revisit a cultural attraction with anapplication to the Museum for Modern and Contemporary Art (MART) in Rovereto, Italy. The empirical

data were obtained from asurvey undertaken in 2009 and a zero-truncated count data model is estimated.The findings reveal that sociodemographic characteristics positively influence the probability to returnto the museum. Also, as reported in other studies, the temporary exhibitions offered by the museum

have a significant impact with an incidence rate ratio almost twice as high. No matter how much visitorsspend on accommodation, they are less likely to revisit ifthey travel in groups, by train or on foot, are far

from their town oforigin and have spent a long time visiting the museum.

2011 Elsevier Masson SAS. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction and research aims

Cultural activity is regarded as a form of tourism, even thoughduring most of the past century, these two activities were con-

sidered as separate. Cultural resources were in fact related toeducation, whereas tourism was regarded as pure leisure. How-ever, since the 1980s cultural activity has begun to be viewed as apart of tourism [1]. As UNESCO reports, cultural and natural her-

itage tourism is the most rapidly growing international sector ofthe tourism industry. Although it is difficult to estimate the actualsize of this phenomenon, the OECD and the UNWTO estimated thatin 2007, cultural tourism accounted for 40% of all international

tourism, up from 37% in 1995 [2].Museums play a relevant role as repositories of cultural diver-

sity, education, social cohesion, personal development; promotean integrated approach to cultural heritage and enable the preser-

vation of community identity. They are also a stimulus for theeconomy, enhancing employment and income, thanks to the mul-tiplier effects they may foster. Several empirical studies show thatcultural consumers generally have a higher spending propensity

than other consumer segments [3]. Overall, museums are expectedto produce positive externalities that can be called cultural spill-

Corresponding author.E-mail address: [email protected](M. Pulina).

over. The presence of a museum in a specific geographical area willnot only benefit public and private agents but society as a wholebecause of the new knowledge will enter societys pool of culturalknowledge.

Italy makes an interesting case study because of its outstand-ing cultural heritage. As Tafter [4] reports, Italy ranks second, afterGermany, for number of museums (both public and private) thatin 2006 reached 4742. According to the Italian National Institute

of Statistics [5], art museums alone represent 29.8% of the totalnon-public supply. Italian museums had approximately 60 millionannual visitors, which translate into more than 140 million eurosin tickets sales alone. However, these figures may underestimate

the actual economic impact, given that not all the institutes holddata on the number of visitors and that more than 43% of museum

visitors did not pay an entrance ticket.From a practitioners perspective, it is of great importance to

predict the repeat visitation to a specific site. It enables localinstitutions and businesses, such as hotels, shops and leisurecompanies, to plan their activities in a more efficient man-ner. From a research point of view, as Litvin [6] points out,

the variable repeat visitation has received scarce attention inthe quantitative investigation for museum demand. Hence, theobjective of this study is to predict the repeat visitation oneof the most important museums of modern and contemporary

art in Italy, the MART in Rovereto. The empirical data wereobtained from face-to-face interviews conducted in the museum

1296-2074/$ seefrontmatter 2011 Elsevier Masson SAS. Allrights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.culher.2011.08.003

http://localhost/var/www/apps/conversion/tmp/scratch_4/dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2011.08.003mailto:[email protected]://localhost/var/www/apps/conversion/tmp/scratch_4/dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2011.08.003http://localhost/var/www/apps/conversion/tmp/scratch_4/dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2011.08.003mailto:[email protected]://localhost/var/www/apps/conversion/tmp/scratch_4/dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2011.08.003 -

8/12/2019 Factors innuencing the intention to revisit a cultural attraction

2/8

168 J.G. Brida et al. / Journal of Cultural Heritage 13 (2012) 167174

between September and November 2009. The representative

sample consists of 350 visitors to the museum. Empirically,a zero-truncated Poisson is estimated, where the dependentvariable is given by the number of timesthe respondent visited themuseum in the past. As far as the author is aware, this is the first

time that this particular econometric approach is used to inves-tigate the likelihood to revisit a museum. The empirical findingsprovided in this papergive destination managers, localgovernmentand policy makers valuable information to formulate development

and marketing strategies for future repeat visits.The paper is organized as follows. In the following section, an

updated literature review on the economic impact of museums isprovided. Section 3 provides the empiricalevidence with a descrip-

tion of the methodology employed. Section 4 presents the casestudy along with the main findings. Discussion and concludingremarks are provided in the last section.

2. A literature review

There is a vast body of literature on the impact that museums

have on the local community, society and economy [720].Empirical evidence is provided on the effects of museums and

galleries on the economy mainly via impact analysis, revealedpreference techniques, such as travel cost analysis, and stated pref-

erencetechniques, such as contingent valuation [21,22]. Onlya fewstudies have adopted the revealed preference analysis to providean economic valuation of museums. For example, Bedate et al. [23]provide an application of travel cost to four heritage sites in Spain,

amongst which there is the museum of Burgos that holds a col-lection of archaeological finds and fine arts. Boter et al. [24] showhow revealed preferences and, in particular travel time, may beused for comparing the relative value of competing museums in

the Netherlands. To this aim, they explicitly take into account theactual distance to the different museums as well as peoples dif-ferences in willingness-to-travel. Fonseca and Rebelo [19] employa travel cost model to estimate the demand curve in the Museum

of Lamego (Portugal). They apply a standard Poisson model, whichreveals that the probability of visiting the museum is positivelyinfluenced by the level of education and gender, and negativelyinfluenced by the travel cost.

While few studies exist on revealed preferences, there are moreexamples of stated preference applications. Mazzanti [25] applies amulti-attribute choice experiment to measure the economic valueand assess user preferences at the Galleria Borghese Museum in

Rome, Italy. Amongst other methods, Sanz et al. [26] propose aparametric, contingent valuation, to estimate and evaluate thewillingness-to-pay (WTP) of both local residents and visitors tothe national museum of Sculpture in Valladolid (Spain). Bedate

et al. [27], estimate the WTP of a representative sample of resi-dents and visitors to the art museum of Valladolid, in Spain via

a contingent valuation. They find that visitors expressed a higherWTP than residents, although the latter appear more enthusias-tic at the prospect of new cultural facilities. Colombino and Nene[28] consider the case of Paestum (Italy) and present an analysis oftourists preferencesin relation to different museumservices.Over-

all, respondents are more interested in extended opening hours,enhancing guided tours of the archaeological site and interactiveteaching labs. They show less interest in transforming the site intoa place of leisure and entertainment. Lampi and Orth [29], via a

contingent valuation method, measure WTP for a visit to the freeentrance Museum World Culture in Sweden. The results show thatfourout ofthe six target groupsare lesslikelyto visit the museum ifa low fee were to be imposed; however, those who are regular cul-

ture consumersstatethattheywouldbe willing to visit themuseum

regardless of the fee level. Via a choice modelling, Choi et al. [22]

examine the economic values of changing various services by Old

ParliamentHouse in Canberra(Australia),that is a museumof socialand political history. They calculate that temporary exhibitions andevents contribute between AU$17.0 million and AU$21.8 millionto annual nationwide welfare. They also reveal that extending the

duration of temporary exhibitions, hosting various events and, incontrast to other research findings [28], that having shops, cafsand fine dining are evaluated positively by respondents.

Using impact analysis, Dunlop et al. [30] find that, in Scotland,

independent art museums and galleries scored the highest incomemultiplier (2.36) and an employmentmultiplier of 1.81. Theimpactof Guggenheim museum of Bilbao, Spain, is estimated to be 1.25

jobs for every 1000 visitors [20]. Cela et al. [31], analyse visitor

spending and the economic impact of heritage sitesat theSilos andSmokestacks National Heritage Area in Iowa, USA. The empiricalfindings show that total shopping per person is highest amongstvisitors to farms, museums, parks and gardens. Non-residents gave

a total contribution of 103million US$ to the rural North-East Iowaand created 1981jobs, thus encouraging institutions and managersto preserve and enhance their heritage.

Satisfaction with the offered product also plays a key role in

providing a constant income source forbusinesses that can be usedto further increase the welfare of the local community. In the lit-

erature, several studies have been devoted to exploring museumvisitors preferences, motivation, satisfaction and their probabil-

ity to return and recommend the site to others. From an empiricalperspective, several methodologies have been employed, such asladdering techniques [32], ordinal and discrete logitmodels [33,34],factor and structural equation models [3539] as well as qualita-

tivemethods [41]. Some generalisedconclusions can be highlightedfrom this strand of literature. Individuals have different values thatinfluence their motivation to visit museums. However, togetherwith education and learning objectives, socially oriented values,

such as fun, entertainment and close relationships with othervisitors, philanthropy and social recognition play a relevant role[32,33,42]. Exhibition environment [36,40], the variety of specialexhibitionson offer[17] and,asBonnetal. [43] emphasise, environ-

mental factors (e.g. lighting, colour, spaciousness, traffic flow) arefarmoreimportant to perpetuate brand meaning anduniqueness inthemindsof visitors than tour guides,music andmerchandisequal-ity. Burton et al. [34] find that visitors tend to be actively engaged

in social and cultural endeavours, often combining a number ofactivities in a single day. Hence, they suggest museums may bene-fit from strategic alliances with other cultural attractions and from

joint packages that add value to the overall experience.

This literature review shows that although numerous studieshave appeared on stated preferences and satisfaction, little atten-tion has been paid to the economic impact of museums on theeconomy. More recently, this view was also confirmed by Cellini

and Cuccia [44] and Choi et al. [22]. In addition, only a few studieshave presented count models [44] that have been widely applied

in empirical travel cost research. Hence, the present paper standsas a novel case study as it uses for the first time a zero-truncatedcount model, stemming from the standard Poisson, to analyse thelikelihood of repeat visits to a museum [46,47].

3. The theoretical framework

To analyse visitors likelihood to revisit MART, a theoretical

framework is constructed based upon the study by Hellstrm andNordstrm [46] and Martinez-Espineira et al. [47]. From an eco-nomic perspective, it is hypothesised that an individual i allocateshis/her time andincome fora bundleof non-tradablegoodsand ser-

vices in the market place, such as a visit to a museum. This model

can be included into the revealed preferences techniques, given

-

8/12/2019 Factors innuencing the intention to revisit a cultural attraction

3/8

J.G. Brida et al. / Journal of Cultural Heritage 13 (2012) 167174 169

by the direct observation of consumer behaviour. Specifically, an

individual i, whose aim is to maximise his/her utility, chooses tovisit n times a given site j (yij), and purchases a bundle of goodsand services that include, amongst other items, transport, food andbeverages and accommodation subject to a budget and time con-

straint [19]. Hence, the relevant utility function is given by thefollowing expression:

ui = uiyi1, . . . yij, ki, zi, xi

j = 1, . . . . . . ,N i = 1, . . . I (1)

where y is the number of visits to the museum, that can take thevalue 1 up to n times; ki are the socioeconomic characteristics ofindividual i (e.g. age, gender, number of family members, income)andziis the perception of the bundle of characteristics of the desti-

nation and heritage site. The choice of the visitor may also dependon the costsxi, incurred by individual i, that include variables suchas distance from the place of habitual residence, accommodationcosts, living costs (e.g. food, beverage, shopping, etc.).

From an empirical perspective, it is important to identify theintrinsic characteristics of the dependent variable. In this case, asthe objective is to predict repeat visitation to the museum, thedependent variable (expressed in terms of number of visits to the

site)isconsideredasacountvariable.Hence,itcantakeonlyintegervalues and the distribution includes either a Poisson or a negativebinomial.The formeris used to modelthe probability ofa numberofevents occurring in a fixed interval of time and/or space, assuming

independence of events, and the events range from zero to infinity.This is necessary to ensure that the model is not mis-specified.Thelatter allows for over-dispersion that can occur if only a few indi-viduals have a large number of visits, this implies the variance in

visits is larger than the mean.Themethodologicalprocedureused in this studyconsists ofrun-

ning an initial standard Poisson, where the distribution is givenby:

ProbYi =yi

wi

=

eyi

yi! yi = 0,1,2, . . . E yi

xi

= Varyi

xi

= = ex

i (2)

The parameter represents both the average and the variance,as assumed by the Poisson distribution, and is greater than zero. widenotes the other controls such as socioeconomic characteristics of

individual i (ki), perception of the bundle of characteristics of thedestination and heritage site (zi) and costs (xi). The Poisson modelis non-linear, however, it can be easily estimated by the maximumlikelihood technique.In the literature, there aremany extensions of

the Poisson model according to the characteristics of the empiricaldata as well as because of the stringent condition that the mean be

equal to the variance [48].In this paper, the best specification is a zero-truncated Poisson

regression that over-performs the zero-truncated negative bino-mial. Specifically, in this case, each call to the museum is at leastone visit, that is, a record would not appear in the database if avisitor had not visited the MART. As stated, the dependent vari-

able assumes a value that ranges from 1 (i.e. first time visit to themuseum) to n. Thus, the variable visit is zero-truncated, and azero-truncated Poisson (or negative binomial) regression allowsone to model visit with this specific restriction. This model can

be specified by the following equation:

ProbYi =yi

wi> 0=

eyi

yi!

11 e

yi = 1,2, . . . . . . (3)

4. The case study

4.1. The town of Rovereto and its cultural heritage

Rovereto is a town of approximately 37,000 inhabitants in the

Autonomous Province of Trento situated in the North of Italy. It hasa very rich cultural heritage developedsincethe Venetian rule (xvthcentury) and during the Austro-Hungarian domination. Amongstother heritage sites, the town hosts one library founded in 1764

with a collection of 370,000 books. Nowadays, it is well-knownfor its cultural and sport events: especially the Mozart Festival (heheld a concert there in 1769), the Oriente-Occidente (East-West)festival, that aims at expanding social and ethnic cohesion, and the

athletic tournament known as Palio Citt della Quercia. The townalso hosts four museums:the Italian WarHistory Museum, the CivicMuseum, the Museum Casa Depero, which is part of the MARTand the Museum for Modern and Contemporary Art of Trento and

Rovereto itself, where Italian Futurism was born.The idea of a Museum for Modern and Contemporary art

was born in the late 1970s, against the background of indus-trial and unemployment crisis. The project, that formally began in

19871988as an independentpublic institutionof the AutonomousProvince ofTrento, wasdesignedby theSwissarchitect MarioBotta,

who also designed the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco.The museum extends over 12,000 square meters, of which 6000

are dedicated to exhibitions, and is divided into three distinct cen-ters: the MART main building; the Palazzo delle Albere based inTrento and the recently restored Casa Depero, which reopenedin January 2009.The Casa Depero project was created to merge the

different collectionsof masterpiecesby Fortunato Depero and otherlocal futurist artists into a permanent collection. The three sectionsof the museum have had 1.7 million visitors since its opening inDecember 2002.

The museum generates revenue from tickets sales, merchandis-ing, sponsors and publishing that cover 24% of total running costs.The remaining 76% is publicly funded by the Autonomous Provinceof Trento.

Despite this rich culturalheritage,todaythe bulk of theRoveretoeconomy is based on industry, agriculture and tertiary sector. Asfar as the tourism activity is concerned, the varied features of thisprovince allow diversification of the tourism supply: rural and eno-

gastronomic holiday in the valleys, skiing holiday in the mountainsand cultural holiday in towns and cities. Rovereto and Trento arethe main centers for the last typology of tourism, and the MARTcan be regarded as a strategic heritage site for both municipalities,

which are situated only 25Km apart. In recent years, the Roveretotourism office has begun joint promotion work with the city ofTrento aimed at creating specific tourist packages and a more effi-cient local tourism network.

Hence, it is worthwhile investigating tourism demand and sup-ply in Rovereto and Trento (the province capital), and the whole

province as a further benchmark before running the empiricalinvestigation. In theprovinceof Trento, tourist supplyis based upontwo main components: hotel and non-hotel infrastructure (such asbed & breakfast, serviced apartments, hostels, agro-tourism activ-ities and camp-sites). Table 1 is based on the data provided by the

Statistics Office of the Autonomous Province of Trento, and reportsthe growth of hotel and non-hotel accommodation, expressed bothin terms of consistency (i.e. number of infrastructure) and capacity(i.e. number of beds), from 2000 to 2008 [49].

While, for the hotel sector, Rovereto shows the highest growthin terms of capacity (+5%), it is the province capital of Trento thatshows the highest increase in terms of consistency (+9%). Notably,the province as a whole has experienced an overall decrease (4%

consistency; 1% capacity). The non-hotel sector presents a dif-

ferent picture. Despite the province as a whole grows less (+31%

-

8/12/2019 Factors innuencing the intention to revisit a cultural attraction

4/8

170 J.G. Brida et al. / Journal of Cultural Heritage 13 (2012) 167174

Table 1

Tourism supply, growth rates in hotel and non-hotel sector (20002008).

Growth rates 20002008 Hotel Non-hotel

Consistency (%) Capacity (%) Consistency (%) Capacity (%)

Trento 9 4 129 68

Rovereto 0 5 167 59

Province 4 1 31 46

Calculation on data from Statistics Office of the Autonomous Province of Trento.

Table 2

Tourism Demand, growth rates in hotel and non-hotel sector (20002008).

Growth rates 20002008 Hotel Non-hotel Total

Arrivals (%) Overnight stays (%) Arrivals (%) Overnight stays (%) Arrivals (%) Overnight stays (%)

Trento 13 34 121 133 22 55

Rovereto 13 12 150 145 26 41

Province 18 11 26 20 19 13

Calculation on data from Statistics Office of the Autonomous Province of Trento.

consistency) and even shows a significant decrease in terms ofcapacity (46%), both Rovereto and Trento denote a high growth

both in terms of consistency and capacity,

Table 2 indicates that tourist flows show a steady increaseduring 2000 and 2008. In the province as a whole, overnight staysgrew 13%, while arrivals 19%.

On balance, arrivals and overnight stays increased more innon-hotel accommodation (26% and 20%, respectively) than inhotels (18% and 11%, respectively). In Rovereto, the total numberof arrivals increased (26%) more than in Trento (22%), while the

reverse can be seen in terms of overnight stays, that grew 55% inTrentoversus 41% in Rovereto.Likewise,non-hotelaccommodationshows an outstanding growth, especially in Rovereto.

These figures provide a clearer picture on the potential attrac-

tiveness of both cities of Trento and Rovereto that may also denotethe positive impact that the MART has had on its overall tourismactivity.

4.2. The survey on the MART

The questionnaire run at the MART museum of Rovereto wasorganized in six blocks, containing 56 questions in total. Based

on the theoretical framework, the questions gather informationon socioeconomic features, trip description and costs incurredby the respondent, information about MART, motivation, satis-faction and loyalty (as previously described). A five-point Likert

scale was used, ranging from not important to very importantfor the motivation factors, and from strongly in disagreement

to strongly in agreement for assessing tourists satisfaction,and from very unlikely to very likely for the loyalty fac-

tors.

The survey was administered from September to November2009, via face-to-face interviews. In a recent survey investiga-tion, conducted by Sergardi and Biraghi [50] for Italian cultural

tourism, it emerges that, although the seasonal distribution ofcultural tourism is very stable during the year, with a minimumof 20% and a peak of 31%, nevertheless, the relatively highercultural tourism flow occurs between September and Novem-

ber. These months account for 26% in September and 31% inOctober and November, respectively, of total tourism flows inthe equivalent month. Furthermore, data were collected both onweekdays and on weekends, at different opening hours (between

10.00 a.m. and 6.00 p.m. that extended to 9.00 p.m. on Fri-days).

Respondents were selected with a quota sampling procedure.

The quotas were based on age and gender and covered cases char-acterized by heterogeneous demographics features. As opposedto random sampling, quota sampling requires that representativerespondents are chosen out of a subset of individuals within apopulation. In this case, a sample was selected according to gen-

der and age. Although this procedure may lead to bias becausenot everyone gets a chance to be selected, it does however over-comes the potential bias derived from a random sample procedure,as the trial may be likely to over-represent specific demographic

characteristics, such as gender or age. A minimum number of 300 participants was set as target. These calculations were based

Table 3

Descriptive statistics of the sample.

Residence (%) Age (% in category)

Nearest Regions 52 > 55 21

Trentino Alto Adige 26 4155 28

Rest of Italy 15 2640 37

Europe 6 1825 14

Others 0,6 Mean 42

Education (%) Income (% in category)

Below high school 6 < D15,000 11

High school 36 D15,000D28,000 28

College/ degree 36 D28,000D55,000 38

Postgraduate 22 D55,000D75,000 12

> D75,000 11

Firstvisit (% yes) 42

Visit other citywithMART (% yes) 91 Visit Rovereto without MART (% yes) 34

Strong intention to return to MART next year (% yes) 36 Strong recommend MART (% yes) 53

Our elaboration on sample data.

-

8/12/2019 Factors innuencing the intention to revisit a cultural attraction

5/8

J.G. Brida et al. / Journal of Cultural Heritage 13 (2012) 167174 171

Table 4

Expenditure pattern of MART visitors.

AverageExpense types Tourists Day-visitors Locals Small groups

food and beverage D15.50 D12.18 D8.10 D15.23

Mart shop D11.32 D9.72 D6.01 D11.12

shopping in town D20.67 D16.33 D19.88 D20.28

overnight stay D32.36Total D79.85 D38.23 D33.99 D46.63

Ourelaboration on sample data.

on five percent margin of error, a 95% confidence level. The

response distribution rate was 90%. Ultimately, 350 surveys werecompleted.

The main socioeconomic characteristics of the visitors are sum-marized in Table 3. More than half of the sample (52%) came

from the surrounding regions (that is Veneto, Lombardy and EmiliaRomagna characterized by the highest market share), followed bylocal residents (26%) from theregion hosting themuseum (TrentinoAlto Adige). Visitors average age was approximately 42, and the

greatest concentration (37%) was in the age range between 26 and40, showing that MART is able to attract relatively young people. Amedium to high education and income level (61% declare to earnmore than 28,000 Dper year) characterize the MART respondents.

More than 40% of the sample was visiting MART for the first time.

A strong intention to repeat the visit was stated by 36% of the

respondents,while 53% willstronglyrecommendthe visitto friendsand relatives.

Based on thesampleresults,the MART representsa great attrac-tion for the city of Rovereto with only 34% of respondents stating

that they would visit the city without it, and 91% willing to visitanother city if it were to host the museum. Overall, this visitorsprofile appears to be in line with the average visitor of contempo-rary art museums in Italy [51]. Moreover, a recent statistical survey

by the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT, [52]) reportsthat the largest share of museum visitors over theage of 6 are fromTrentino.

It is also interesting to give a more detailed account on the

expenditure pattern of the MART visitors (Table 4).

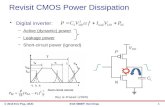

Table 5

Zero-truncated Poisson regression results.

Variables Poisson Model Zero-Truncated Poisson Model

Coefficients IRR a Coefficients IRR a

Age 0.0014 (0.0027) 1.001 (0.0027) 0.0002 (0.0045) 1.0002 (0.0045)

Gender (ref. male) 0.1007 (0.0706) 1.1059 (0.0781) 0.1129 (0.1114) 1.1196 (0.1247)

Education 0.0495* (0.0261) 1.050* (0.0275) 0.0594 (0.0416) 1.0612 (0.0441)

Income 0.0473 (0.0325) 0.9537 (0.0310) 0.0680 (0.0503) 0.9342 (0.0470)

Number of peoplein thegroup 0.0341** (0.0161) 0.9664** ( 0.0156) 0.003649* 0.9211* (0.0409)

Nationality (ref. Italians) 0.1817 (0.1884) 1.1993 (0.2260) 0.3143 (0.4139) 1.3693 (0.5668)Distance Rovereto-home town 0.1018*** (0.0324) 0.9031** * ( 0.0293) 0.1485*** (0.0565) 0.8619*** (0.0487)

Mean of transport toget to the MART (ref. car)Train 0.1627 (0.1209) 0.8498 (0.1027) 0.3154 (0.02589) 0.7294 (0.1888)

Bus 0.1491 (0.2340) 1.1608 (0.2716) 0.4900 (0.4225) 1.6323 (0.6897)

Foot 0.2033** (0.0819) 0.8160** (0.0668) 0.3247*** (0.1154) 0.7226*** (0.0834)

Total accommodation costs 0.0001** (0.0000) 1.0001** (0.0000) 0.0002* (0.0001) 1.0000* (0.0001)

Souvenir expenditure within the MART 0.0039*** (0.0013) 1.0039*** (0.0013) 0.0061*** (0.0019) 1.0061*** (0.0020)

Total food and beverage costs 0.0024* (0.0014) 0.9975* ( 0.0014) 0.0028 (0.0025) 0.9971 (0.0025)

Shopping expenditure in Rovereto 0.0015 (0.0012) 0.9984 (0.0012) 0.0020 (0.0022) 0.9979 (0.0022)

Importance to visit MART 0.0606* (0.0347) 0.9411* ( 0.0327) 0.1231** (0.0548) 0.8841** ( 0.0484)

Importance to visit Trentino 0.0506** (0.0219) 1.0519** (0.0231) 0.0831** (0.0358) 1.0866** (0.0389)

Importance to visit friends 0.0417 (0.0322) 1.0426 (0.0336) 0.0836* (0.04702) 1.0872* (0.0511)

Time spent visiting MART 0.0487 (0.0396) 0.9524 (0.0377) 0.0623 (0.0639) 0.9395 (0.0600)

Exhibition (ref. permanent)

Temporary 0.2559* (0.1269) 1.2916* (0.1639) 0.5737* (0.1269) 1.774* (0.4736)

Permanent and temporary together 0.0388 (0.1496) 0.9618 (0.1439) 0.0946 (0.2995) 1.0993 (0.3293)

Have youvisited Casa Depero (ref. no)

Depero yes 0.4149*** (0.0873) 1.5143*** (0.1322) 0.5761*** (0.1368) 1.779*** (0.2435)

Depero later 0.1689** (0.0826) 1.2056** (0.0996) 0.2565* (0.1374) 1.2924* (0.1776)

Would youvisited other city hosting MART (ref. no)

Other city 0.1562 (0.1171) 1.1691 (0.1370) 0.3427** (0.1664) 1.4088** (0.2344)

MART originality 0.0333 (0.0469) 1.0338 (0.0485) 0.0758 (0.0736) 1.0788 (0.0795)

Visit MART next year 0.2870*** (0.0394) 1.3324*** (0.0525) 0.5217*** (0.0781) 1.6850*** (0.1316)

Suggest to visit MART 0.1851*** (0.0473) 0.8309** * ( 0.0393) 0.3339*** (0.0746) 0.7160*** (0.0534)

Constant 0.4921* (0.2639) 0.1452 (0.4664)PseudoR2 0.1445 0.1445 0.2392 0.2392

Wald Chi2 (26) 580.6 580.6 256.05 256.05

Prob>Chi2 = 0.000 Prob > Chi2 = 0.000 Prob > Chi2 = 0.000 Prob > Chi2 =0.000

Log pseudolikelihood 329.28 329.28 277.96 277.96

AIC 712.56 712.56 609.92 609.92

BIC 803.44 803.44 700.81 700.81

Likelihood-ratio test of alpha = 0 Chibar2 (01) = 0.000 Probchibar2 =1.000

Notes: ***, ** and* indicate statistically significance at the1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively.a

e.g. IRR indicate the exponentiated coefficients = eb; robust standard errors are in parenthesis.

-

8/12/2019 Factors innuencing the intention to revisit a cultural attraction

6/8

172 J.G. Brida et al. / Journal of Cultural Heritage 13 (2012) 167174

For this purpose, the sample is divided into four visitor-types:

tourists, by definition those who spent at least one night in thetown; day visitors, whose visit lasts only one day; locals, who areresident nearby; and finally, small groups (i.e. travelling with twoother people on average). Aside from accommodation costs, for all

types of tourists the greatest share of expenditure is, on average,taken by shopping in Rovereto, followed by food and beverage. Thesmallest expenditure category is shopping at the museum. Thesedata show that overall the MART is able to produce positive exter-

nalities on the local town economy.

5. Empirical results

The parametric estimation is based upon the theoretical frame-work previously specified. The relevant variables included intothe model, and obtained by the survey data as presented in the

previous section, are described in greater detail in Table A.1, in theAppendix A.

The empirical specification is estimated by using STATA 10 andresults are reported in Table 5. As a basic specification, a standard

Poisson regression is employed in order to predictthe repeatvisita-tion to the MART [19]. As stated, the dependent variable, number

of visits, is a count variable. The standard Poisson model is thenempirically compared to the standard negative binomial specifi-

cation, to allow for over-dispersion. The log-likelihood-ratio testof alpha, that tests whether the standard Poisson distribution isempirically a better specification (or, equivalently, the mean isequal to the variance), fails to reject the null hypothesis (Table 5).

Besides, applying the goodness-of-fit test in the standard Poissonmodel (estatgof in Stata 10), the null hypothesis (i.e. the empir-ical model fits the data) cannot be rejected (i.e. Goodness-of-fitChi2 =98.6969Prob>Chi2 (187) = 1.0000). This result is further

confirmed by the AIC and BIC criteria that are minimised in theformer model.

As a further extension of the model, a zero-truncated Poisson isestimated, that explicitly allows one to model the dependent vari-

able with thespecific restriction that it rangesfrom oneto N (i.e. thecount variable cannot be zero).Full results are presented in Table 5.Note howthe AICand BICcriteria arefurther minimisedin thezero-truncated Poisson. Hence, there are statistical grounds to retain

the zero-truncated Poisson as a better empirical specification. Itis worthwhile noting that in all the cases robust standard errorsare estimated, given the relatively low number of observationsthat may lead to problems in the residuals(e.g. heteroskedasticity).

Also note that apart from one exception, all the signs of the coef-ficients are congruent in both models. IRRs (Incidence Rate Ratios)are reported, that are exponential of the coefficients. The interpre-tation varies according to the magnitude of IRRs. If their value is

below one then the variable is negatively influencing the likeli-hood of a repeat visit; if the value is above one the opposite holds.

Finally, if the value is equal, or very close to one, then a neutraleffect is detected.

Considering the socio-demographic controls, ceteris paribus, itemerges that a unit change in age results in the expected num-ber of visits to MART increasing very marginally by a factor of

exp(0.0002)= 1.0002. A female visitor has an expected repetitionvisit of 1.12 times. Education also indicates a positive influence onthe number of revisits to the museum. As an economic control,income shows a negative impact. All these coefficients turn out not

to be statistically significant in the zero-truncated Poisson model.The number of people travelling with the respondent positivelyaffects the likelihood to repeat the visit to the MART and present astatistically significant coefficient.

The nationalitydummy (Italians is the reference group) suggests

that foreigners are more likely to revisit the museum. However,

distance from Rovereto to the place of habitual residence has a

negative and highly statistically significant impact on the expectednumber of visits to the museum. This variable can be thought of asa proxy of the actualtrip costs. Hence,the further the distance fromRovereto the smaller the probability to repeat the visit. Taking into

account the choice of transportation mode, however, respondentsarriving by bus are more likely to revisit than those travelling bycar (the reference group). On the other hand, visitors who arrivedby train or on foot (that present a highly statistically significant

coefficient) are less likely to repeat the experience in the future.Accommodation costs and expenditure in souvenirs at the

museum present a statistically significant coefficient with a posi-tive sign. IRRs are veryclose to one meaning that these expenses do

not appearto influence the probability to revisit MART. Conversely,the coefficients for expenditure in shopping in Rovereto and food-beverage present a negative sign, hence these variables have anegative influence on the number of visits to the MART. Time spent

visiting the museum may be regarded as a proxy for the opportu-nitycost of leisure timeand the expectation is that those who spenta longer time visiting the MART are less likely to repeat the visit.

A set of furthercontrols highlights how pull forces may encour-

age a revisit the museum in the future. The findings reveal theimportance of visiting Trentino as well as the role of friends and

familyas factors that maypositivelydrive repeat visits. Positive pullfactors are temporary exhibitions (with a statistically significant

coefficient) and also temporary-permanent exhibitions. Further-more, those who either had already visited, or intended to visit, theCasa Depero revealan expected numberof visitsequalto 1.78 and1.29, respectively, higher than those who did not visit the site (the

reference group). Therefore, the MART itself emerges as the sig-nificant factor, which is likely to encourage future visitations. Thehigher the originality scores attributed by visitors to the museum,the higher the likelihood to repeat the experience. Finally, the

probability to recommend the site to friends and relatives reducesthe expected revisit by the respondent.

6. Discussion andconclusions

In this paper, the different factors influencing the intention torevisit the Museum for Modern and Contemporary Art (MART) of

Rovereto (Italy) have been analysed.Investment in cultural activities has been the local institutions

answer to face the economic crisis Rovereto was going through. Asshown in this study,over the past decadethe town hasexperienced

an increase in the total number of tourism overnights, bothin hoteland non-hotel infrastructure, as well as a rise in the overall tourismsupply. It is well-established that tourism activity itself is able totrigger economic growth (see Brida and Pulina, [53] for a detailed

literature review). Specifically, by running a Johansen cointegrationanalysis applied to regional data, Brida and Risso [54] show that

the long run elasticity of the real gross domestic product (GDP) totourism demand is 0.29. Besides, theGranger causalitytest assessesa unidirectional temporal relationship running from tourism activ-ity to real GDP. This shows empiricalevidence that tourism activityis able to activate a virtuous path of growth for the Trentino region

as a whole.In the present paper, the theoretical model has been based on

the hypothesis that an individual maximises his/her utility giventhe number of times she/he visits the heritage site and further

socioeconomic variables, subject to time and income constraints.Empirical data were collected via a survey on 350 visitors at thesite. From an empirical perspective, the study shows that thezero-truncated Poisson gives a better specification than a standard

Poisson model, as the dependent variable does not assume a zero

value. Results are in line with other empirical studies concerning

-

8/12/2019 Factors innuencing the intention to revisit a cultural attraction

7/8

J.G. Brida et al. / Journal of Cultural Heritage 13 (2012) 167174 173

probability of revisiting cultural attractions [19] and other tourist

attractions [45].The empirical findings also highlight important marketing and

management implications: the MART could be used as the icon forRovereto itself, with a view to generating an immediate association

of thecity with this cultural site as well as creating a marketing tool.Since the MART has shown to be attractive to relatively youngerpeople, a specific strategy could be implemented in order to fur-ther attract this segment of demand. Networking with the other

museums, such as Casa Depero and the Museum for Modern andContemporary Art (Museion) in Bolzano, may help to develop asystematic culture itinerary.

Considering that respondents with a lower probability to repeat

visitation have a strong intention to recommend the museum tofriends and relatives, a successful management policy may be toprovide visitors withtangible incentives such as discount vouchersfor entry fees, or museum shop purchases. Specific communica-

tion policies may be also implemented in the neighbourhood ofRovereto and in the nearer provinces, especially Bolzano, by adver-tising another important cultural centre.

The contribution of the present study, which applies a new

empirical approach into the investigation of the economic impactof a specific museum, can be further tested for and expanded to

other heritage sites, thus adding robustness to the present paper.Besides, a future challenge of research in this field will involve a

systematic investigation on the relationship between the culturalattractions of Rovereto and its tourism growth.

Appendix A. Table 1 List of control variables

Name Definition

Age Age of the respondent

GEN ( reference group m ale) This dichotomous variable takes the

value one if female, zero if male

Education This is a discrete variable that takes the

value onefor thelowest level of

education(i.e. primary school) up to 7

for thehighest level of education (i.e.Ph.D)

Income This is a discrete variable that takes the

value 1 for anincomeup to 15

thousand euros, and progressively up

to 5 for anincome higher than75

thousand euros

Number ofp eopleinthe g roup This discretev ariabletakes into

account thesize of the travelling group

of the respondent

Nationality (reference group

Italians)

This dummy takes the value one if the

visitor is foreigner, zero otherwise

Distance Rovereto-home town This is a discretev ariablethat takes thevalue oneif therespondent comes to

Trentino Alto Adige, and progressively

a highervalue further the distance of

his/her place of residence

Meanof transport toget to the MART(reference group car) Train: takes oneif therespondenttravelled by train, zero otherwise

Bus: takes oneif therespondent

travelled by bus, zero otherwise

Foot: takes oneif therespondent went

to theMART by foot, zero otherwise

Total accommodation c osts This i s a continuous v ariable t hataccounts for the accommodation costs,

expressedin euro,undertaken by the

respondent in all official (i.e. hotel,

non-hotel camp sites, agrotourism,

serviced apartments) and non-official

tourism infrastructure such as second

homes andfriends andfamily

Souvenir expenditure atMART This is a continuous variable that

accountsfor thecosts, expressedin

euro, undertaken by therespondent to

purchase goods at theMART

Name Definition

Total food and beverage costs This is a continuous variable that

accounts forthe costs, expressed in

euro, undertaken by therespondentto

purchase food and beverage.Shopping expenditure in

Rovereto

This is a continuous variablethat

accounts for the shopping expenditure,

expressed in euro, undertaken by the

respondent

I mportance tov isitM ART This is a discretev ariablethat takes

values from 1 (not important at all) up

to 5 (very important) forattributing an

increasing importance for visiting the

city of Rovereto, given thepresence of

the MART

Importanceto visit Trentino Thisis a discretevariablethat takesvalues from 1 (not important at all) up

to 5 (very important) forattributing an

increasing importance for visiting the

city of Rovereto, given is located in the

region of Trentino Alto Adige

Importance t o v isit friends This i s a discrete v ariable t hat takes

values from 1 (not important at all) up

to 5 (very important) forattributing an

increasing importance for visiting the

city of Rovereto, given therespondent

is visiting friends and familyTime s pent visiting M ART This i s a discrete v ariable t hat accounts

forthe time (i.e. minutes) the

respondent spent in theMART forthe

visit

Exhibition (reference grouppermanent exhibitions)

Permanent: this dummy takes the

value one if the visitor was drivenby a

temporary exhibition, zero otherwise

Permanent and temporary together:

this dummy takes the value one if the

visitor was driven both by a temporary

and permanent exhibition, zerootherwise.

Have youvisited Casa

Depero(reference group no)

This is a dummy variable that takes the

valueone if therespondenthas already

visited Casa Depero (i.e. thehouseof

the futurist Fortunato Depero) in

Rovereto, zero otherwiseDepero later (reference group

no)

This is a dummy variable that takes the

valueone if therespondenthas the

intentionto visit Casa Depero (i.e. the

house of the futurist Fortunato Depero)

in Roveretolater(or another day, zero

otherwiseDepero later (reference group

no)

This is a dummy variable that takes the

valueone if therespondenthas the

intentionto visit Casa Depero in

Roveretolater(or another day, zero

otherwise

Would youvisited other city

hosting MART (reference

group. no)

This is a dummy variable that takes the

valueone if therespondentwouldvisit

another city hosting theMART, zero

otherwise

MART originality This is a discrete variable that takes

values from 1 (not original atall)up to5 (very original)for attributing an

increasing satisfaction with the

originality of the MART

Visit MART next year This is a discrete variable that takes

values from 1 (very unlikely) upto 5

(very likely) forthe possibility the

respondent returns the next year

Suggest to visit MART This is a discrete variable that takes

values from 1 (very unlikely) upto 5

(very likely) forthe possibility the

respondent recommends the MART tofriends and family

References

[1] OECD, The Impact of Culture on Tourism, 2009, Available at:

http://www.em.gov.lv/images/modules/items/OECD Tourism Culture.pdf.

http://www.em.gov.lv/images/modules/items/OECD_Tourism_Culture.pdfhttp://www.em.gov.lv/images/modules/items/OECD_Tourism_Culture.pdf -

8/12/2019 Factors innuencing the intention to revisit a cultural attraction

8/8

174 J.G. Brida et al. / Journal of Cultural Heritage 13 (2012) 167174

[2] Mintel, Cultural and Heritage Tourism-International, 2011, Availableat: http://oxygen.mintel.com/sinatra/oxygen/display/id=138804/display/id=482710.

[3] Europa Inform, The Economic Impact of Historical Cultural tourismRomit ProjectRoman Itineraries, 2004, Avail able at: http://www.romit.org/en/pubblicazioni.htm.

[4] Tafter, I talia terra dei mus ei L a ultime rilevaz ione I stat dei non statali,2011, Available at: http://www.tafter.it/2009/11/05/italia-terra-dei-musei-la-ultime-rilevazione-istat-dei-non-statali/.

[5] ISTAT, National Institute of Statistics: Indagine sugli istituti di antichit edarte e i luoghi di cultura non statale, 2011, Av ailable at: http://www.

istat.it/dati/dataset/20090721 00/.[6] S.W.Litvin,Marketingvisitorattractions: a segmentationstudy,Int. J. Tour. Res.

9 (2007) 919.[7] W.A. Luksetich, M.D. Partridge, Demand functions for museum services, Appl.

Econ. 29 (12) (1997) 15531559.[8] Plaza, Guggenheim Museumseffectiveness to attract tourism, Ann. Tour. Res.

27 (4) (2000) 10551058.[9] D. Maddison, T. Foster, Valuing congestion costs in the British museum, Oxf.

Econ. Pap. 55 (1)(2003) 173190.[10] D. Maddison, Causality and museum subsidies, J. Cult. Econ. 28 (2) (2004)

89108.[11] D.J. Stynes, S.G.A. Vander, Y.Y. Sun, Estimating economic impacts of michi-

ganmuseums, department of parkrecreation and tourism resources, MichiganState University, East Lansing, 2004.

[12] B.S. Frey, S. Meier, The economics of museums in: V.A. Ginsburgh, D. Throsby(Eds.), Handbook of the economics of art and culture, vol. 1, Elsevier, Amster-dam, 2006.

[13] M. Mazzanti, Discrete choice models and valuation experiments, J. Econ. Stud.30 (6) (2004) 584604.

[14] C. Scott,Museums: impact and value, Cult. Trends 15 (1)(2006) 4575.[15] N. Kinghorn, K. Willis, Estimating visitor preferences for different art gallery

layoutsusing a choice experiment, Mus. Manag. Curatorship221 (2007)4358.[16] N. Kinghorn, K. Willis, Measuring museum visitor preferences towards oppor-

tunities fordeveloping socialcapital:an application of a choice experiment tothediscovery museum, Int. J. Herit. Stud. 146 (2008) 555572.

[17] B. Plaza,On some challenges and conditions forthe Guggenheim museumBil-bao to be an effectiveeconomic re-activator, Int. J. UrbanReg. Res. 322 (2008)506517.

[18] B. Plaza, S.N. Haarich, Museums for urban regeneration? Exploring conditionsfortheir effectiveness, J. UrbanReg. Renew. 23 (2009) 259271.

[19] S. Fonseca, J. Rebelo, Economic valuation of cultural heritage: application to amuseum located in the Alto Douro Wine RegionWorld Heritage Site, Pasos 8(2) (2010) 339350.

[20] B. Plaza, Valuing museums as economic engines: willingness to pay or dis-counting of cash-flows? J. Cult. Herit. 11 (2010) 155162.

[21] S. Mourato,M. Mazzanti, Economicvaluation of culturalheritage: evidenceandprospects.Assessingthe valueof culturalheritage, GettyConservation Institute,

Los Angeles, CA, 2002.[22] A.S. Choi, B.W. Ritchie, F. Papandrea, J. Bennett, Economic valuation of culturalheritagesites: a choice modeling approach, Tour. Manag. 312 (2010) 213220.

[23] A. Bedate, L.C. Herrero, L. Sanz, Economic valuation of the cultural heritage:application to four case studies in Spain,J. Cult. Herit. 5 (2004) 101111.

[24] J. Boter, J. Rouwendal, M. Wedel, Employing travel time to compare the valueof competingcultural organizations, J. Cult. Econ. 29 (2005) 1933.

[25] M. Mazzanti, Discrete choice models and valuation experiment, J. Econ. Stud.30 (6) (2003) 584604.

[26] J.A. Sanz, L.C. Herrero, A.M. Bedate, Contingent valuation and semiparametricmethods:a casestudyof theNational Museumof Sculpturein Valladolid, Spain,J. Cult. Econ. 27 (2003) 241257.

[27] A.M. Bedate, L.C. Herrero, J.A. Sanz, Economic valuation of a contemporary artmuseum: correction of hypothetical bias using a certainty question, J. Cult.Econ. 33 (2009) 185199.

[28] U. Colombino, A. Nene, Preference heterogeneity in relation to museum, Tour.Econ. 15 (2) (2009) 381395.

[29] E. Lampi, M. Orth, Who visits the museums? A comparison between statedpreferences and observed effects of entrance fees, Kyklos 621 (2009) 85102.

[30] S., Dunlop, S., Galloway, C., Hamilton, A., Scullion, The economic impactof the cultural sector in Scotland, 2004, Available at: http://www.christinehamiltonconsulting.com/documents/Economic%20Impact%20Report.pdf.

[31] A.C. Cela, S. Lankford, J. Knowles-Lankford, Visitor spending and economicimpacts of heritagetourism: a casestudyof theSilos andSmokestacksNationalHeritage Area, J. Herit. Tour. 43 (2009) 245256.

[32] M. Thyne, The importance ofvalues research for nonprofit organisations: Themotivation-based values of museum visitors, Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect.Mark. 62 (2000) 116130.

[33] A.K. Paswan, A. Troy, Non-profit organization and membership motivation:

an exploration in the museum industry, J. Mark. Theory Pract. 12 (2) (2004)115.

[34] C. Burton,J. Louviere,L. Young,Retaining thevisitor,enhancingthe experience:identifying attributes of choice in repeat museum visitation, Int. J. NonprofitVolunt. Sect. Mark. 14 (2009) 2134.

[35] P. Harrison, R. Shaw, Consumer satisfaction and post-purchase intentions: anexploratory study of museumvisitors, J. Arts Manag. 62 (2004) 2332.

[36] J.H. Jeong, K.H. Lee, The physical environment in museums and its effects onvisitors satisfaction, Build. Environ. 41 (2006) 963969.

[37] C. De Rojas, C. Camarero, Visitors experience, mood and satisfaction in a her-itage context: evidence from an interpretation center, Tour. Manag. 29 (2008)525537.

[38] S.MGil, B.R.B. Ritchie, Understanding the museum image formation process acomparison of residents and tourists, J. Travel Res. 474 (2009) 480493.

[39 ] M. Hume, How do we keep them coming? Examining museum experiencesusing a servicesmarketing paradigm, Int.J. NonprofitVolunt.Sect. Mark. 23 (1)(2011) 7194.

[40] C.Alcaraz, M.Hume, G.S.Mort, Creatingsustainable practisein a museum con-text: adopting service-centricity in non-profit museums, Australas. Mark. J. 17(2009) 219225.

[41] J. Packer, N. Bond, Museumsas restorative environments, Curator 53 (4)(2010)421436.

[42] I.AalstVan, I.Boogaarts,Frommuseumto massentertainment. Theevolutionofthe role of museums in citiesRepeat visitation in mature sunand sand holidaydestinations, Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 9 (3) (2004) 195209.

[43] M.A. Bonn, S.M. Joseph-Mathews, M. Dai, S. Hayes, J. Cave, Heritage/culturalattraction atmos pherics : creating the right environment for the her-itage/cultural visitor, J. Travel Res. 45 (2008) 345354.

[44] R., Cellini, T., Cuccia, Museum and monument attendance and tourism flow: atime series analysis approach, MPRAPaper No. 18908 (2009) 128.

[45] R.Scarpa, M. Thiene, T. Tempesta, Latentclass count models of total visitationdemand: days outhiking in theeastern Alps, Environ. Resour. Econ. 33 (2007)447460.

[46] J.Hellstrm, J.Nordstrm, A count datamodelwithendogenoushousehold spe-cific censoring: thenumber of nightsto stay, Empir. Econ. 35 (2008) 179192.

[47] R. Martinez-Espineira, J.B. Loomis, J. Amoako-Tuffour, J.M. Hilbe, Compar-ing recreation benefits from on-site versus household surveys in count data

travel cost demand models with overdispersion, Tour. Econ. 14 (3) (2008)567576.[48 ] W. Greene, Econometric analysis, fifth ed., Prentice Hall, New Jersey, 2003.[49] Autonomous, Province of Trento, 2011, data provided by, available at:

http://www.statistica.provincia.tn.it/.[50] P., Sergardi, A., Biraghi, Il ruolo del turismo culturale e del turismo daffari

nellincoming internazionale dellItalia. LItalia ed il turismo internazionale.Pragma. TNS Infratest (2007).

[51] ISTAT, National Institute of Statistics: Noi Italia 100 statistiche per capireil paese in cui viviamo, 2011, Available at: http://www.istat.it/salastampa/comunicati/non calendario/20100112 00/.

[52] Centro Studi e Ricerche Associazione Civita, Il Pubblico dei Musei di ArteContemporanea, 2007, Ava ilable at: http://www.civita.it/centro studigianfranco imperatori/ricerche e indagini/il pubblico dei musei d artecontemporanea.

[53] J.G. Brida, M. Pulina, A literature review on tourism and economic growth, in:Working Paper, 1017, CRENoS, Cagliari and Sassari University, 2010.

[54] J.G. Brida, W.A. Risso,Tourism as a determinant of long-run economic growth,J Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Event 2 (1)(2010) 1428.

http://oxygen.mintel.com/sinatra/oxygen/display/id=138804/display/id=482710http://oxygen.mintel.com/sinatra/oxygen/display/id=138804/display/id=482710http://www.romit.org/en/pubblicazioni.htmhttp://www.tafter.it/2009/11/05/italia-terra-dei-musei-la-ultime-rilevazione-istat-dei-non-statali/http://www.istat.it/dati/dataset/20090721_00/http://www.christinehamiltonconsulting.com/documents/Economic%2520Impact%2520Report.pdfhttp://www.romit.org/en/pubblicazioni.htmhttp://www.tafter.it/2009/11/05/italia-terra-dei-musei-la-ultime-rilevazione-istat-dei-non-statali/http://www.istat.it/dati/dataset/20090721_00/http://www.statistica.provincia.tn.it/http://www.istat.it/salastampa/comunicati/non_calendario/20100112_00/http://www.civita.it/centro_studi_gianfranco_imperatori/ricerche_e_indagini/il_pubblico_dei_musei_d_arte_contemporaneahttp://www.civita.it/centro_studi_gianfranco_imperatori/ricerche_e_indagini/il_pubblico_dei_musei_d_arte_contemporaneahttp://www.istat.it/salastampa/comunicati/non_calendario/20100112_00/http://www.statistica.provincia.tn.it/http://www.christinehamiltonconsulting.com/documents/Economic%2520Impact%2520Report.pdfhttp://www.istat.it/dati/dataset/20090721_00/http://www.tafter.it/2009/11/05/italia-terra-dei-musei-la-ultime-rilevazione-istat-dei-non-statali/http://www.romit.org/en/pubblicazioni.htmhttp://oxygen.mintel.com/sinatra/oxygen/display/id=138804/display/id=482710http://oxygen.mintel.com/sinatra/oxygen/display/id=138804/display/id=482710