Facial Onset Sensory and Motor Neuronopathychoreoathetosis, was seen in 6 patients (cases 21, 22,...

Transcript of Facial Onset Sensory and Motor Neuronopathychoreoathetosis, was seen in 6 patients (cases 21, 22,...

REVIEW OPEN ACCESS

Facial Onset Sensory and Motor NeuronopathyNewCases Cognitive Changes and Pathophysiology

Eva MJ de Boer MD Andrew W Barritt MD MRCP Marwa Elamin MD PhD Stuart J Anderson PhD

Rebecca Broad MD PhD Angus Nisbet MD PhD H Stephan Goedee MD PhD Juan F Vazquez Costa MD PhD

Johannes Prudlo MD PhD Christian A Vedeler MD PhD Julio Pardo Fernandez MD PhD

Monica Povedano Panades MD Maria A Albertı Aguilo MD Eleonora Dalla Bella MD Giuseppe Lauria MD

Wladimir BVR Pinto MD Paulo VS de Souza MD Acary SB Oliveira MD PhD Camilo Toro MD

Joost van Iersel BcS Malu Parson McS Oliver Harschnitz MD PhD Leonard H van den Berg MD PhD

JanH VeldinkMD PhD AmmarAl-ChalabiMD PhD PeterN Leigh FMedSci PhD andMichael A vanEsMD PhD

Neurology Clinical Practice April 2021 vol 11 no 2 147-157 doi101212CPJ0000000000000834

Correspondence

Dr van Es

mavanesumcutrechtnl

AbstractPurpose of ReviewTo improve our clinical understanding of facial onset sensory andmotor neuronopathy (FOSMN)

Recent FindingsWe identified 29 new cases and 71 literature cases resulting ina cohort of 100 patients with FOSMN During follow-up cognitiveand behavioral changes became apparent in 8 patients suggestingthat changes within the spectrum of frontotemporal dementia(FTD) are a part of the natural history of FOSMN Another newfinding was chorea seen in 6 cases Despite reports of autoanti-bodies there is no consistent evidence to suggest an autoimmunepathogenesis Four of 6 autopsies had TAR DNA-binding protein(TDP) 43 pathology Seven cases had genetic mutations associatedwith neurodegenerative diseases

SummaryFOSMN is a rare disease with a highly characteristic onset and pattern of disease progressioninvolving initial sensory disturbances followed by bulbar weakness with a cranial to caudalspread of pathology Although not conclusive the balance of evidence suggests that FOSMNis most likely to be a TDP-43 proteinopathy within the amyotrophic lateral sclerosisndashFTDspectrum

Facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathy (FOSMN) is a rare neurologic syndrome firstdescribed by Vucic et al in 20061 It has a characteristic phenotype with paresthesia and

These authors contributed equally

Universitair Medisch CentrumUtrecht (EMJB HSG JI MP LHB JHV MAE) Department of Neurology Utrecht The Netherlands Brighton and SussexMedical School (AWBME RB PNL) ClinicalImaging Sciences Centre Brighton United Kingdom Hurstwood Park Neurological Centre (AWB ME SJA RB AN) Haywards Heath United Kingdom Hospital Universitari i Politecnic La Fe(JFVC) ALS Unit Department of Neurology Valencia Spain Centro de Investigacion Biomedica en Red de Enfermedades Raras (CIBERER) (JFVC) Madrid Spain Department of Neurology (JP)Rostock University Medical Center and German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE) Germany Department of Neurology (CAV) Haukeland University Hospital and Department ofClinical Medicine Bergen Norway Department of Neurology (JPF) Hospital Clınico Universitario de Santiago Santiago Spain Department of Neurology (MPP MAAA) Hospital Universitari deBellvitgeBarcelona SpainALSMNDCentre (EDBGL) 3rdNeurologyUnit Fondazione IRCCS InstituteNeurologicoCarloBestaMilan ItalyDepartmentofBiomedical andClinical Sciences ldquoLuigiSaccordquo (GL) University ofMilanMilan Italy Department ofNeurology andNeurosurgery (WBVRP PVSS ASBO) Federal University of SatildeoPaulo (UNIFESP) Satildeo Paulo Brazil National Institutes ofHealth (CT) National Human Genome Research Institute Bethesda United States of America Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (OH) NY Kingrsquos College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust(AA-C) London United Kingdom and Department of Neuroscience (PNL) Brighton and Sussex Medical School Brighton United Kingdom

Funding information and disclosures are provided at the end of the article Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article atNeurologyorgcp

The Article Processing Charge was funded by the Medical Research Council (grant no MRR0248041) awarded to A Al-Chalabi

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 40 (CC BY) which permits unrestricted use distribution and reproduction in anymedium provided the original work is properly cited

Copyright copy 2020 The Author(s) Published by Wolters Kluwer Health Inc on behalf of the American Academy of Neurology 147

numbness arising within the trigeminal nerve distributionwhich slowly spreads to the scalp and thereafter descends tothe neck upper trunk upper extremities and in some casesto the lower extremities The initial sensory disturbance maybegin in a perioral location or affect one or more of thetrigeminal branches unilaterally and then become bilateralor be bilateral from the beginning Lower motor neuronfeatures present later or concurrently with the sensory defi-cits These include dysphagia dysarthria fasciculationsmuscle weakness and muscle atrophy along the samerostral-caudal direction2 In general only the lower motorneuron system is involved although upper motor neuronsigns have been reported in a few cases3ndash11

Pathogenesis is uncertain Initial indications suggested an auto-immune basis since autoantibodies have been reported as well asa partial and subjective response to immunotherapy1346812ndash16

The finding of TAR DNA-binding protein (TDP) 43 pa-thology at autopsy in several FOSMNcases however impliesa neurodegenerative mechanism and a likely association withamyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)8ndash1017

The objective of this study is to expand our understanding ofFOSMN by evaluating clinical findings and the natural his-tory of the disease in a larger sample than hitherto availableand to review the current literature

MethodsUpdated Case SeriesFOSMN is an extremely rare disorder with only 38 casesreviewed to date2 We provide an updated case series bydescribing new incident cases and cases identified throughliterature search

Incident cases were seen at the following specialized (neuro-muscular) clinics University Medical Centre Utrecht (TheNetherlands) Brighton and Sussex University HospitalsNHS Trust (UK) Rostock University Hospital (Germany)University Hospital i Politecnic La Fe Valencia (Spain) Uni-versity Hospital Clınico de Santiago (Spain) University Hos-pital de Bellvitge in Barcelona (Spain) University HospitalHaukeland Bergen (Norway) Foundation of the Carlo Besta

Neurological Institute IRCCS Milan (Italy) National HumanGenome Research Institute Bethesda (United States ofAmerica) and the Federal University of Satildeo Paulo (Brazil)

Several patients self-reported to us some through theFOSMN patient organization in which case the treatingphysician was contacted to obtain medical records At pres-ent there are no formal diagnostic criteria for FOSMN Thediagnosis was therefore made based on excluding other po-tential causes and expert opinion

We performed a systematic search of the literature with theobjective of identifying FOSMN cases that were not includedin previous reviews Titles and abstracts were screened andrelevant full-text articles were retrieved Correspondingauthors were also contacted for additional details (figure 1)Published cases not included in reviews before and ourincident cases will be reported separately as novel cases

Clinical DataWe extracted the following data from published cases and themedical records of the incident cases sex age at onset dis-ease duration bulbar signs sensory deficits weakness of ex-tremities uppermotor neuron signs laterality cerebral spinalfluid results antibody testing results of imaging geneticanalysis neurophysiologic evaluation type of therapy andresponse biopsy need for a gastric feeding tube or percuta-neous endoscopic gastrostomy need for noninvasive venti-lation cause of death and autopsy findings

Follow-up data on previously published cases and availablelongitudinal data from the incident cases were included131618

We encoded and stored the data in a secure password-protected database

PathophysiologyThere are 2 leading hypotheses with regard to the cause ofFOSMN namely that it is either a neurodegenerative or anautoimmune disorder From our cases and the literature weextracted data on ancillary investigations response to treat-ment disease course and postmortem findings These datawere subsequently categorized as supportive of a neurode-generative or autoimmune etiology

ResultsUpdated Case Series and Clinical FindingsWe identified a total of 29 incident cases Our literature searchyielded 26 full-text articles reporting on a total of 64 patientswith FOSMN of which 29 were not described in a reviewbefore13ndash1618ndash24 We further identified 7 abstractsposterssupplements reporting on 11 potential cases and 2 articlesmentioning 10 FOSMN cases without further patientcharacteristics2526 After reaching out to the correspondingauthors we received a detailed poster on 7 patients withFOSMN17 We chose not to include the other 14 possible

There are 2 leading hypotheses with

regard to the cause of FOSMN

namely that it is either

a neurodegenerative or an

autoimmune disorder

148 Neurology Clinical Practice | Volume 11 Number 2 | April 2021 NeurologyorgCP

patients with FOSMN due to the limited information in theabstracts This led to a total of 100 patients with FOSMN Themain clinical findings of the 28 cases that had not been reportedpreviously are summarized in table e-1 linkslwwcomCPJA171 The baseline characteristics for all 100 FOSMN cases aredescribed in table 1 Most cases developed progressive sensorydeficits starting in the trigeminal nerve distribution and slowlyspreading to the scalp neck shoulders upper extremities andin a few cases to the lower extremities Later (in some casesconcurrently) lower motor signs developed starting in the faceand spreading through the same pattern as the sensory dis-turbances resulting in bulbar symptoms (dysarthria and dys-phagia) fasciculations atrophy and weakness of the involvedmuscles (figure 2) Asymmetrical presentation of the symp-toms (initially) occurred in 48 of the cases in whom the firstaffected side remained more severely affected as the diseaseprogressed despite involvement of the contralateral side Lowermotor neuron signs were observed in all FOSMN cases Upper

motor neuron signs such as brisk reflexes Babinski sign andclonus were reported in 27 cases3ndash1114

Natural historyThe mean age at onset is approximately 55 years (range 7ndash78years) The rate of progression is highly variable and survivalranges from 14 months to over 46 years13ndash23 Ninety-onepercent of the cases started with progressive facial sensoryimpairment followed by motor involvement In a single casesensory symptoms slowly developed 10 years after onset ofthe motor deficits13 Two patients developed high-frequencysensorineural hearing loss developed which started mid-50s(cases 1 and 2)13 Case 4 from our case series (table e-1linkslwwcomCPJA171) also complained of hearing losshowever results of ancillary investigations were not avail-able Sleeping problems were described in 2 cases case 9 hadsigns suggesting REM sleep behavioral disorder and in case113 this was confirmed by polysomnography (Pseudo)

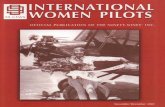

Figure 1 Summary of the Results from the Literature Search

The search was performed on September 1 2019 using PubMed and EMBASE on articles from January 1 2006 to September 1 2019 reporting on FOSMNTitles and abstracts were screened and relevant full-text articles were retrieved References were screened for additional studies FOSMN = facial onsetsensory and motor neuronopathy

NeurologyorgCP Neurology Clinical Practice | Volume 11 Number 2 | April 2021 149

choreoathetosis was seen in 6 patients (cases 21 22 25 2627 and a literature patient who was followed up on)16

Ninety-seven percent of the patients developed bulbarsymptoms13ndash11131416ndash23 Weight loss resulting from dys-phagia in FOSMN may be severe and in 34 cases gastro-stomy was indicated134781011131416ndash1923 The meandisease duration before placement was 5 (1ndash14) years afteronset of the symptoms Fourteen patients required non-invasive ventilation8111619

Of the 39 patients who died the mean disease duration was75 years Of the known causes of death 23 patients died asa result of progressive bulbar weakness leading to aspirationpneumonia or respiratory failure3578101217202123

Behavioral Changes and Cognitive ImpairmentFive patients developed progressive behavioral changes andwere clinically diagnosed with comorbid behavioral variantfrontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) by the treating neurologistReview of the medical records indeed shows that the Rascovskycriteria are met27 One patient also showed progressive be-havioral changes strongly suggestive of bvFTD but no formaldiagnosis was made Considering FOSMN is a potential mimic(or perhaps even an atypical formal form) of ALS patients arecommonly referred to motor neuron disease (MND) clinicsGiven that ALS and FTD are highly related disorders screeningfor cognitive and behavioral changes has become part of thestandard workup in MND most frequently using the Edin-burgh Cognitive and Behavioral ALS screen (ECAS) There-fore ECAS data for 6 FOSMN cases seen at MND clinicswere available to us (one of the patients diagnosed with bvFTDalso underwent an ECAS) In total neuropsychological datawere available for 11 patients of which 8 demonstrated changeswithin the FTD spectrum (72) Three patients showednormal ECAS results and no behavioral changes

There are no available data on cognition and behavioralchanges in the remaining 89 cases therefore we are unable toprovide an estimate of the frequency of these changes inFOSMN A brief summary of neuropsychological findings ofthese cases is provided in table 2

The first case is a man (patient 1)13 who at age 59 years (17years after onset) began to complain of deteriorating mem-ory for recent events had difficulty planning activities andbecame apathetic with blunted empathy or emotionalresponses thereby meeting the criteria for possible bvFTDCognitive screening using the ECAS did not demonstratememory deficits but did show that he scored under thecutoff for verbal fluency

The second case is a 45-year-old man (patient 7)13 who 12years after onset of FOSMN became very irritable with socialwithdrawal and became obsessive and mildly apathetic Mem-ory for recent events and concentration abilities were also di-minished He also meets the criteria for possible bvFTD

Table 1 Demographics and Characteristics of Patientswith FOSMN

n n tested ina

Patients 100

Male 67

Mean age at onset y (range) 55 (7ndash78)

Mean disease duration ym 82 y

Range 14 mndash46 y

Patients who are still alive 61 (86 y)

Patients who died 39 (75 y)

Male 29 (73 y)

Female 9 (68 y)

Unknown 1 (6 y)

Onset with facial sensory symptoms 91 100

Sensory deficits

Face 96 100

Upper extremities 40 100

Lower extremities 11 100

Motor impairment

Bulbar symptoms 97 100

Upper extremities 77 100

Lower extremities 23 100

Upper motor neuron signs 27 95

Antibodies positive 14

Neurophysiologic tests

Blink reflex abnormal 94 96

EMG DR signs 94 94

NCS SNAP amplitude reduced 53 86

Treatment

Immunotherapy started 48 95

Any form of response 10

GFTPEG placed or indicated 34

Patients deceased 39

Cause of death

Aspiration pneumoniarespiratory failure 23

Refusal of enteral nutrition 1

Lung cancertrauma 2

Unknown 13

Abbreviations DR = degenerationregeneration signs EMG = electromy-ography FOSMN = facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathy GFT =gastric feeding tube NCS = nerve conduction study PEG = percutaneousendoscopic gastronomy SNAP = sensory nerve action potentiala n tested in = number of patients in which having the feature is describedtested

150 Neurology Clinical Practice | Volume 11 Number 2 | April 2021 NeurologyorgCP

Another case with signs of bvFTD is patient 8 At age 69years after 22 years of disease he developed short-termmemory loss aphasia and difficulty following instructionsEpisodes of confused nocturnal wandering occurred soonafter sleep onset during which he held the delusion that hiswife was an imposter and could become aggressive whenchallenged Unfortunately limited information was availablefrom medical records but aphasia and behavioral changeswere the most prominent features in this case It is unclearwhether we should classify this patient as having primaryprogressive aphasia or as cognitive and behavioral impair-ment according to the current Strong criteria for fronto-temporal spectrum disorder in MND28 The latter is a termwhich is applicable to patients with cognitive and behavioralchanges within the spectrum of FTD but that do not meetthe formal criteria Unfortunately the patient died before fullneuropsychological evaluation could be achieved BrainMRIs were normal in all 3 cases

Two patients showed cognitive impairment according to theECAS without behavioral changes Patient 2 and patient 6a Spanishpatientwith brain atrophy predominating in the rightfrontotemporal lobes His ECAS showed mild cognitive im-pairment (executive functioning) and another memoryscreening test (MT) showed mild impairment in long-termepisodic memory Because the ALS-FTD-Q is not validated inSpanish a semistructured ECAS interview and the FRSBEquestionnaire were performed with normal results2429

Differential DiagnosisAt present there is no diagnostic test that can definitivelyconfirm FOSMN nor are there existing diagnostic criteria Thediagnosis is based on expert opinion and relies predominantlyon a history of facial onset sensory symptoms followed by facialweakness and a subsequent cranial-caudal spread of symptoms

Other causes need to be ruled out making FOSMN a diagnosisby exclusion There is considerable heterogeneitywith regard tothe presentation For instance some patients did not seekmedical attention for the facial sensory signs The interval be-tween the onset of facial sensory signs and weakness can rangefrom years to simultaneous onset There was 1 case wheresubtle sensory symptoms only developed 10 years after onset ofthe motor deficits13 The rate of progression differs consider-ably with some patients developing severe bulbar weaknesswithin a year compared with patients with exclusively sensorysymptoms for a decade Therefore disease duration rate ofprogression and chief complaint (sensory motor or both)influence the differential diagnosis and the workup

In patients with isolated sensory signs idiopathic trigeminalneuropathy or a central lesion is themain alternative In cases inwhich bulbar weakness is progressive or the predominant fea-ture ALS (and ALS mimics) needs to be considered particu-larly because it has been suggested that FOSMN is an atypicalform of ALS30 In most cases the differential diagnosis is quiteextensive Table 3 provides an overview of the differential di-agnosis and most relevant additional investigations

Laboratory investigations are generally unremarkable Mildlyelevated CK levels may be found but never exceeding gt5 timesupper limit normal CSF is also normal MRI studies inpatients with FOSMN do not explain the symptoms al-though mild to moderate midcervical cord atrophy has beenreported in several cases bright tongue sign in 3 patients11

and frontotemporal atrophy in 2 patients24

Extensive genetic testing has been performed in various caseswhich included ALS genes (C9orf72 FUS SOD1 TARDBP)oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy (PABPN1) Kennedydisease (AR) panels for spinocerebellar ataxia as well as

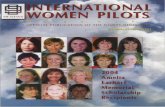

Figure 2 Summary Distribution Abnormalities in FOSMN

Distribution of sensory motor and electrophysiologic findings in patients with FOSMN In all 3 pictures the darker color represents the higher amount ofpatients with abnormalities showing the cranial-caudal spreading EMG = electromyography FOSMN = facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathySNAP = sensory nerve action potential

NeurologyorgCP Neurology Clinical Practice | Volume 11 Number 2 | April 2021 151

whole-exome sequencing With a few exceptions (discussedbelow) genetic testing has not given any insight so far

There are several electrophysiologic findings that supporta diagnosis of FOSMN Blink reflexes are abnormal in allcases but 2 cases17 varying from unilateral to bilateraldelayed or absent R1 andor R2 responses Needle elec-tromyography showed signs of denervation andor rein-nervation in all patients spreading in a cranial-caudaldistribution Sensory nerve conduction studies show re-duced sensory nerve action potential amplitudes of the up-per limbs in 62 and in the lower limbs in 4 cases (figure 2)

PathophysiologyThe main hypotheses are that FOSMN is either a neurodegener-ative or an autoimmune disorder We reviewed the literature andextracted data on ancillary investigations response to immune-

modulating treatment genetics disease course and postmortemfindings and subsequently categorized these data as supportive ofa neurodegenerative or autoimmune etiology (table 4) Auto-antibodies were present in 14 patients Three of these cases 1 withlow-positive ANA and anti-Ro 1 with anti-sulfo-glucuronyl par-aglo-boside IgG anti-myelin-associated glycoprotein IgG and thefinal patient with a monoclonal gammopathy responded toimmunotherapy6814 One patient had apparent stabilization ofsymptoms6 1 had partial response of weakness and sensory im-pairment but thereafter had worsening respiratory symptoms8

and in the last patient intravenous immunoglobulin relieved herfacial numbness and improved the blink reflex but motor symp-toms worsened Six other patients also had a form of response toimmunotherapy but did not report positive immunologic studies

In a total of 6 patients with FOSMN an autopsy wasperformed15891723 The pathologic studies show loss of

Table 2 Neuropsychological Profiles of Patients with FOSMN

Patients 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Disease duration at the time of ECAS (y) 17 14 3 4 20 4 NA NA NA NA NA

ECAS cognitive domains NP NP NP NP NP

Language

Verbal fluency X

Executive functioning X X

Memory

Visuospatial X

ECAS behavioral interview X NP NP NP NP NP NP

Behavioral changes NA NA NA NA NA

36 Rascovsky criteria p bvFTD X X X X X

Disinhibition x x x

Apathyinertia x x x

Loss of sympathyempathy x x x x x

Preservativecompulsive x x x x

Hyperorality

Dysexecutive profile x x

Suggestive of bvFTD but noneuropsychological evaluation

X

(Pseudo)choreoathetosis X X X

Abbreviations ECAS = Edinburgh Cognitive and Behavioral ALS Screen FOSMN = facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathy FTD = frontotemporaldementia NA = not applicable NP = not performed p bvFTD = possible behavioral variant FTD according to the Rascovsky criteriaThis table shows the ECAS results (patients 1ndash6) and behavioral changes of patients with FOSMN X represents a score under cutoff for the ECAS domainindicating cognitive impairment and represents the presence of behavioral changesPatients 1 2 and 6 show cognitive impairment according to the ECAS Patients 7ndash11 did not have an ECAS but did have behavioral changes Patients 1 7 9 10and 11 met the criteria for possible bvFTD Patient 8 showed cognitive and behavioral changes suggestive of bvFTD but never had a neurophyschologicalevaluation Patients 3 and 4 did not show abnormalities in the ECAS or behavioral changesPatient 1 (case 1 Broad and Leigh)13 case 2 (case 2 incident cases) case 3 (case 3 incident cases) patient 4 (case 6 incident cases) patient 5 (case 20 incidentcases) patient 6 (Vazquez-Costa et al)24 patient 7 (case 2 Broad and Leigh)13 patient 8 (case 8 case series) patient 9 (Dalla Bella et al)16 patient 10 (case 21incident cases) and patient 11 (case 22 incident cases)

152 Neurology Clinical Practice | Volume 11 Number 2 | April 2021 NeurologyorgCP

motor neurons in the facial nerve nucleus and hypoglossalnucleus and cervical anterior horns and loss of sensory neuronsin the main trigeminal sensory nucleus nucleus of the solitarytract and dorsal root ganglia Four cases had TDP-43ndashpositiveglial inclusions891723 The other 2 cases had no intraneuralinclusions and stained negative for ubiquitin15 Cutaneousnerve and muscle biopsies show a loss of myelinated fibers andWallerian degeneration of the nerves without signs of vasculitisor amyloid deposition145172021 Genetic analysis was positivein 7 cases In 1 case a heterozygous D90A SOD1 mutation(familial ALS) was found There were also 2 cases of a het-erozygous TARDBP mutation1011 of which 1 patient hada positive family history (2 maternal cousins with definitive

genetic diagnosis of ALS andmotherwith FTD)11 There was 1case of a heterozygous mutation in TARDBP and inSQSTM124 Furthermutations foundwere a heterozygousVCPmutation in a patient with a mother with FTD brother withspinal-onset ALS and nephew with IBM11 a patient witha heterozygous CHCHD10 mutation whose mother had bi-lateral eyelid ptosis and Parkinson disease and brother hadchronic exercise intolerance and proximal myopathy11 and 1case with a genetic mutation in the PABPN1 gene (oculo-pharyngeal muscular dystrophy)5 Furthermore 2 patientswith FOSMN were described who underwent whole-exomesequencing without definitive results but had a positive fam-ily history of neurodegenerative diseases a mother with

Table 3 Differential Diagnosis of FOSMN

Disease Tests

Kennedy disease Genetic analysis CAG repeat androgen receptor chromosome Xq11-12

Sjogren disease Anti-Roanti-SS-A anti-Laanti-SS-B

Schirmer test and Saxon test

Lip biopsy

Tangier disease HDL triglycerides and cholesterol spectrum

Nerve biopsy

Genetic analysis ABCA1 gene

Amyloidosis Genetic analysis mutation Gelsolin gene

Syringomyliasyringobulbia MRI of the brain and cervical spine

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Electrodiagnostic studies EMG and NCS

Genetic analysis SOD1 FUS TARBDP and C9orf72 genes

Autoimmune-mediated neuropathy Anti-sulfatide antibodies anti-diasialosyl antibodies anti-ganglioside antibodies (GD1a andGT1a) anti-GD1b ANA ENA anti-SGPG IgG anti-MAG IgG M-protein screening rheumatoidfactor antindashdouble-stranded DNA anti-Sm anti-RNP anti-Scl79 anti-phospholipids and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

Basal meningitis MRI of the brain and CSF

Ischemia MRI of the brain

Myasthenia gravis Antibodies against AChR MuSK or LRP-4

Repetitive nerve stimulation

Sarcoidosis ACE SOL IL-2 receptor

Idiopathic trigeminal neuropathy MRI of the brain

Hereditary motor sensory neuropathy EMG

Genetic analysis CMT subtypes

Infections Serology serum andor CSF HIV Borrelia herpes simplex virus 1ndash2 varicella zoster virusleprosy hepatitis BC and Treponema pallidum

Thyroid dysfunction TSH and free T4

Ocular pharyngeal muscular dystrophy Genetic analysis PABPN1 gene

Brown-Vialetto-Van-Laere syndrome Genetic analysis SLC52A2 and SLC52A3 genes

Fazio-Londe syndrome Genetic analysis SLC52A3 gene

Abbreviations CMT =CharcotMarie Tooth EMG= electromyography FOSMN= facial onset sensory andmotor neuronopathy NCS = nerve conduction study

NeurologyorgCP Neurology Clinical Practice | Volume 11 Number 2 | April 2021 153

FTD-ALS and a maternal aunt and grandmother with Par-kinson disease and a patient with 2 brothers and a mother withALS11 A positive family history was also seen in incident case13 (brother died of ALS) and incident case 16 (FTD) To dateno cases with a positive family history of FOSMN are reported

DiscussionFOSMN is a rare neurologic syndrome with a total of 100documented patients worldwide to date It typically com-mences with a trigeminal distribution sensory disturbance

Table 4 Characteristics of Patients With FOSMN Categorized by Possible Underlying Mechanism

Neurodegenerative mechanism Autoimmune mechanism

No positive immunologic studies arementioned in 72 cases of CSF analysis andimmunologic studies in serum are negativein 7890 (87) Positive immunologic studies (13)

Immunologic studies n cases positive n cases tested

Antinuclear antibody 5 55

Anti-sulfatide IgG 3 17

Anti-MAG IgG 2 19

Monoclonal gammopathy 3 6

Anti-GD1b antibodies 1 33

Anti-Ro 1 43

Anti-dsDNA 1 (slightly) 27

No response to immunotherapy in mostcases

(Partial) response to immunotherapy

IVIg treatment in 44 cases (20 response)

Stabilization in 1 case6

Partial recovery in 4 cases3814

Response to the first treatment but not to the second course of treatment in 1 case12

Temporary improvement of blink reflex in 2 cases18

Steroids treatment in 15 cases

Partial response in 1 case8

Plasma exchange treatment in 6 cases

Improvement and no further progression in 1 case12

MRI shows a bright tongue sign in 3patients11 and frontotemporal atrophy in2 patients24

MRI of the brain and cervical spine showsno signs of inflammation

2 cases with a positive family history ofALSFTD-ALS11

Positive genetic testing heterozygousSOD1 mutation (n = 1)16 heterozygousTARDBPmutation (n = 2)1011 heterozygousTARDBP and SQSTM1 mutations (n = 1)24

heterozygous VCP mutation (n = 1)11 andheterozygous CHCHD10 mutation (n = 1)11

46 autopsies had TDP-43 intraneuralinclusions891723

66 autopsy cases reported sensory andmotor neuronal degeneration15891723

Abbreviations ALS = amyotrophic lateral sclerosis FTD = frontotemporal dementia FOSMN = facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathyIVIg = intravenous immunoglobulin TDP = TAR DNA-binding protein

154 Neurology Clinical Practice | Volume 11 Number 2 | April 2021 NeurologyorgCP

which progressively engulfs the head neck trunk and upperand lower extremities It is followed by motor weaknessspreading along the same craniocaudal distribution pro-gressing to bulbar symptoms weakness of the extremitiesand respiratory motor impairment (figure 2) Over thecourse of the disease patients with FOSMN develop dys-phagia leading to severe weight loss (requiring gastronomy)as well as sometimes fatal aspiration pneumonia Causes ofdeath in FOSMN are similar to ALS adding to the view thatthere is overlap between the 2 conditions

Hitherto little attention has been paid to the presence ofbehavioral and cognitive changes in patients with FOSMNSix cases are described to have behavioral changes suggestiveof bvFTD In 2 patients without behavioral changes evidencefor executive dysfunction was seen on the ECAS It seemsthat behavioral changes and cognitive changes within theFTD spectrum may occur in patients with long disease du-ration expanding the phenotype of FOSMN Additionalneuropsychological research in FOSMN seems warranted tobetter understand these cognitive and behavioral changes

Because the cause of FOSMN is unknown there is no testthat definitively confirms this diagnosis Patients are there-fore diagnosed based on expert opinion and by excludingother disorders that could cause comparable symptomsBecause there are no formal diagnostic criteria we cannot besure that all documented patients indeed have FOSMNThree patients have no sensory symptoms and 1 patient onlyhas sensory symptoms in the lower extremities They dohowever all have abnormal blink reflexes indicating tri-geminal involvement Until consensus is reached on formaldiagnostic criteria that have been validated the diagnosis isbased on expert opinion potentially causing bias in thepresent findings

Thus far the pathogenesis of FOSMN has remained elusiveThere are 2 main hypotheses It has been suggested that theunderlying mechanism may be either autoimmune mediatedor neurodegenerative

An autoimmune origin is supported by the fact that autoanti-bodieswerepresent in14patientswithFOSMN Itmust benotedthat the panel of antibodies that was tested varied considerablybetween cases and that therefore the percentage of positive casescould be an underestimation or that yet unidentified antibodiesare involved However there seems to be little consistency in thedetected antibodies and several of these antibodies are associated

with multiple conditions and may be even be found in healthyindividuals Therefore these antibodies findings seem to benonspecific A potential underlying autoimmune cause couldpossibly be detected with better antibody screening or by usinginduced pluripotent stem cellndashderived trigeminal neurons31

Immune-modulating therapy is often initiated in FOSMN and(partial) response has been reported which would also supportan autoimmune etiology The definition of treatment responsewas rather arbitrary ranging from partial recoverystabilizationto a temporary improvement of the blink reflex In several casesthe treatment response was not documented by objectivemeasurement (and therefore may have beenmerely subjective)or perhaps not clinically relevant (temporary improvement ofblink reflex) making the effect debatable There have been noplacebo-controlled studies of immunotherapy

Multiple lines of evidence seem to support the hypothesisthat FOSMN is a neurodegenerative disorder Perhaps mostconvincing is that the autopsies of 4 FOSMN cases revealedintraneuronal TDP-43 inclusions which is the pathologichallmark of ALS and FTD

In a journal supplement 2 patients with FOSMNarementionedin which postmortem examination also revealed TDP-43 ag-gregates in themotor and sensory trigeminal nucleus and anteriorhorn cells of the cervical and thoracic cord in patient 1 and in thesensory and motor trigeminal nucleus and cervical thoracicand lumbar motor neurons with associated astrocytosis in pa-tient 232 Unfortunately we only had access to the abstract butthese findings also support the neurodegenerative etiology

Furthermore a link to ALS has been suggested after a patientwith FOSMN was found to harbor a heterozygous mutation inthe familial ALS gene for SOD1 This specific mutation (D90A)generally causes a recessive form of ALS although there areseveral pedigrees in which this mutation appears to cause diseasein an autosomal dominant manner It is therefore unclearwhether thismutation should be considered pathogenic33Othercases of FOSMN with mutations related to ALS have also beenfound Two cases with a heterozygous TARDBPmutation bothconsidered pathogenic1011 a heterozygous pathogenic VCPmutation and a heterozygous pathogenic CHCHD10 muta-tion11 Finally there was a patient with 2 heterozygousmutationsin the TARDBP and in SQSTM1 genes In this case it wassuggested that the combination of the mutations resulted in thisphenotype24 Some of these patients had a positive family historyof ALS or other neurodegenerative diseases Four patients witha positive family history of FTD-ALS ALS FTD and or Par-kinson disease but without definitive results from genetic testingwere also reported11 This suggests that these diseases maycluster with pedigrees like other neurodegenerative diseases3435

The fact that patients develop severe bulbar symptoms withrespiratory insufficiency (reminiscent of ALS) and may de-velop cognitive and behavioral changes within the FTDspectrum supports considering FOSMN as part of the FTD-

Multiple lines of evidence seem to

support the hypothesis that FOSMN

is a neurodegenerative disorder

NeurologyorgCP Neurology Clinical Practice | Volume 11 Number 2 | April 2021 155

MND continuum Indeed findings at autopsy have alsoprovided evidence that FOSMN may be a TDP-43proteinopathy

TDP-43 pathology is seen in approximately 98 of patientswith ALS but is absent in the 2 of ALS that can be attributedto SOD1mutations3336 The presence of TDP-43 pathologyand the identification of an SOD1 mutation suggest a con-nection to ALS and although there is some limited evidencein support of an autoimmune mechanism this is far fromconclusive Our tentative conclusion is that FOSMN is mostlikely to have a neurodegenerative etiology possibly withinthe ALS-FTD continuum

To determine the underlying cause of FOSMN more re-search is needed through an international collaborationconsidering the rare nature of the disease The developmentof diagnostic criteria followed by validation is an importantfirst step A better understanding of the natural history of thedisease will aid physicians in providing their patients with theappropriate care Further characterization of the disease inparticular whether FOSMN is a TDP-43 proteinopathy mayprovide inroads into therapy options based on insights fromother TDP-43ndashrelated disorders

AcknowledgmentsThe authors thank Dr E Peter Bosch for sharing informationwhich made it possible to include 7 extra patients in thereview They also thank the FOSMN Patients Foundation

(fosmnorg) for their assistance in finding new cases for thecase series

Study FundingThis is an EU Joint ProgrammendashNeurodegenerative DiseaseResearch (JPND) project The project is supported throughthe following funding organizations under the aegis ofJPNDmdashjpndeu (United Kingdom Medical ResearchCouncil (MRR0248041) Netherlands ZonMW(733051071) BRAIN-MEND) and through the MotorNeurone Disease Association This study represents in-dependent research part funded by the National Institute forHealth Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre atSouth London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust andKingrsquos College London This work was supported in part bythe Intramural Research Programs of the National HumanGenome Research Institute (NHGRI) National Institutes ofHealth (NIH)

DisclosureThe authors report no disclosures relevant to themanuscriptFull disclosure form information provided by the authors isavailable with the full text of this article at Neurologyorgcp

Publication HistoryReceived by Neurology Clinical Practice October 18 2019 Accepted infinal form March 4 2020

TAKE-HOME POINTS

FOSMN is an extremely rare neurologic diseasestarting with sensory impairment in the facespreading along a craniocaudal distribution fol-lowed bymotor involvement spreading by the samepattern

FOSMN resembles ALS in the sense that motorimpairment results in weakness eventual need forgastronomy and in most cases respiratory failureDisease duration however is longer than forpatients with ALS

Although not conclusive the balance of evidencesuggests that FOSMN is most likely to be a TDP-43proteinopathy within the ALS-FTD spectrum This issupported by the resembling disease progressionpresence of TDP-43 pathology and genetic muta-tions associated with MNDs found in patients withFOSMN

Further (international) research is required to formdiagnostic criteria and to obtain further knowledgeon FOSMN

Appendix Authors

Name Location Contribution

Eva MJ de BoerMD

University MedicalCenter Utrecht theNetherlands

Collected andinterpreted the data anddrafted the manuscriptfor intellectual content

Andrew W BarrittMD MRCP

Brighton amp SussexMedical School UK andHurstwood ParkNeurological CentreHaywards Heath UK

Interpreted the data anddrafted the manuscriptfor intellectual content

Marwa Elamin MDPhD

Brighton amp SussexMedical School UK andHurstwood ParkNeurological CentreHaywards Heath UK

Interpreted the data andrevised the manuscriptfor intellectual content

Stuart J AndersonPhD

Hurstwood ParkNeurological CentreHaywards Heath UK

Interpreted the data andrevised the manuscriptfor intellectual content

Rebecca BroadMD PhD

Brighton amp SussexMedical School UK andHurstwood ParkNeurological CentreHaywards Heath UK

Interpreted the data andrevised the manuscriptfor intellectual content

Angus Nisbet MDPhD

Hurstwood ParkNeurological CentreHaywards Heath UK

Interpreted the data andrevised the manuscriptfor intellectual content

H Stephan GoedeeMD PhD

University MedicalCenter Utrecht theNetherlands

Interpreted thedata designed figuresand revised themanuscript forintellectual content

156 Neurology Clinical Practice | Volume 11 Number 2 | April 2021 NeurologyorgCP

References1 Vucic S Tian D Chong PST Cudkowicz ME Hedley-Whyte ET Cros D Facial

onset sensory and motor neuronopathy (FOSMN syndrome) a novel syndrome inneurology Brain 20061293384ndash3390

2 Zheng Q Chu L Tan L Zhang H Facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathyNeurol Sci 2016371905ndash1909

3 Fluchere F Verschueren A Cintas P et al Clinical features and follow-up of four new casesof facial-onset sensory and motor neuronopathy Muscle and Nerve 201143136ndash140

4 Dobrev D Barhon RJ Anderson NE et al Facial onset sensorimotor neuronopathysyndrome a case series J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2012147ndash10

5 Vucic S Stein TD Hedley-Whyte ET et al FOSMN syndrome novel insight intodisease pathophysiology Neurology 20127973ndash79

6 Knopp M Vaghela NN Shanmugam SV Rajabally YA Facial onset sensory motorneuronopathy an immunoglobulin-responsive case J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 201314176ndash179

7 Barca E Russo M Mazzeo A Terranova C Toscano A Girlanda P Facial onsetsensory motor neuronopathy not always a slowly progressive disorder J Neurol20132601415ndash1416

8 Sonoda K Sasaki K Tateishi T et al TAR DNA-binding protein 43 pathology ina case clinically diagnosed with facial-onset sensory and motor neuronopathy syn-drome an autopsied case report and a review of the literature J Neurol Sci 2013332148ndash153

9 Ziso B Williams TL Walters RJL et al Facial onset sensory and motor neuronop-athy further evidence for a TDP-43 proteinopathy Case Rep Neurol 2015795ndash100

10 Zhang Q Cao B Chen Y et al Facial onset motor and sensory neuronopathysyndrome with a novel TARDBP mutation Neurologist 20192422ndash25

11 Pinto WBVR Naylor FGM Chieia MAT de Souza PVS Oliveira ASB New findingsin facial-onset sensory and motor neuronopathy (FOSMN) syndrome Rev Neurol(Paris) 2019175238ndash246

12 Hokonohara T Shigeto H Kawano Y Ohyagi Y Uehara M Kira Jichi Facial onsetsensory and motor neuronopathy (FOSMN) syndrome responding to immuno-therapies J Neurol Sci 2008275157ndash158

13 Broad R Leigh PN Recognising facial onset sensory motor neuronopathy syndromeinsight from six new cases Pract Neurol 201515293ndash297

14 Watanabe M Shiraishi W Yamasaki R et al Oral phase dysphagia in facial onsetsensory and motor neuronopathy Brain Behav 20188e00999

15 Karakaris I Vucic SSJ Facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathy (FOSMN) ofchildhood onset Muscle Nerve 201450614ndash615

16 Dalla Bella E Rigamonti A Mantero V et al Heterozygous D90A-SOD1 mutation ina patient with facial onset sensory motor neuronopathy (FOSMN) syndrome a bridgeto amyotrophic lateral sclerosis J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014851009ndash1011

17 Bosch EP Goodman BP Tracy JA Dyck PJB Giannini C Facial onset sensory andmotor neuronopathy a neurodegenerative TDP-43 proteinopathy J Neurol Sci2013333e468

18 Dalla Bella E Lombardi R Porretta-Serapiglia C et al Amyotrophic lateral sclerosiscauses small fiber pathology Eur J Neurol 201623416ndash420

19 Isoardo G Troni W Sporadic bulbospinal muscle atrophy with facial-onset sensoryneuropathy Muscle and Nerve 200837659ndash662

20 Cruccu G Pennisi EM Antonini G et al Trigeminal isolated sensory neuropathy(TISN) and FOSMN syndrome despite a dissimilar disease course do they sharecommon pathophysiological mechanisms BMC Neurol 201414248

21 Truini A Provitera V Biasiotta A et al Differential trigeminalmyelinated and unmyelinatednerve fiber involvement in FOSMN syndrome Neurology 201584540ndash542

22 Lange KS Maier A Leithner C Elevated CSF neurofilament light chain concentration ina patient with facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathy Neurol Sci 202041217ndash219

23 Rossor AM Jaunmuktane Z Rossor MN Hoti G Reilly MM TDP43 pathology inthe brain spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia of a patient with FOSMN Neurology201992E951ndashE956

24 Vazquez-Costa JF Pedrola Vidal L Moreau-Le Lan S et al Facial onset sensory andmotor neuronopathy a motor neuron disease with an oligogenic origin AmyotrophLateral Scler Front Degener 201920172ndash175

25 Olney NT Bischof A Rosen H et al Measurement of spinal cord atrophy using phasesensitive inversion recovery (PSIR) imaging in motor neuron disease PLoS One201813e0208255

26 Davids M Kane MS Wolfe LA et al Glycomics in rare diseases from diagnosistomechanism Transl Res 20192065ndash17

27 Rascovsky K Hodges JR Knopman D et al Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteriafor the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia Brain 20111342456ndash2477

28 Strong MJ Abrahams S Goldstein LH et al Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis - fronto-temporal spectrum disorder (ALS-FTSD) revised diagnostic criteria AmyotrophLateral Scler Front Degener 201718153ndash174

29 Caracuel A Verdejo-Garcıa A Fernandez-Serrano MJ et al Preliminary validation ofthe Spanish version of the frontal systems behavior scale (FrSBe) using Rasch analysisBrain Inj 201226844ndash852

30 Vucic S Facial onset sensory motor neuronopathy (FOSMN) syndrome an unusualamyotrophic lateral sclerosis phenotype J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 201485951

31 Harschnitz O Human stem cellndashderived models lessons for autoimmune diseases ofthe nervous system Neuroscientist 201925199ndash207

32 Oliveira H Jaiser SR Polvikoski T et al FOSMN-MND broadening the phenotype ofa heterogeneous disease Amyotroph Lateral Scler Front 201819(suppl 1)291ndash292

33 Andersen PM Al-Chalabi A Clinical genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis whatdo we really know Nat Rev Neurol 20117603ndash615

34 Fallis BA Hardiman O Aggregation of neurodegenerative disease in ALS kindredsAmyotroph Lateral Scler 20091095ndash98

35 Longinetti E Mariosa D Larsson H et al Neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseasesamong families with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Neurology 201789578ndash585

36 Tan RH Kril JJ Fatima M et al TDP-43 proteinopathies pathological identificationof brain regions differentiating clinical phenotypes Brain 20151383110ndash3122

Appendix (continued)

Name Location Contribution

Juan F VazquezCosta MD PhD

Hospital Universitari iPolitecnic La Fe ValenciaSpain and CIBERERMadrid Spain

Major role in theacquisition of dataand revised themanuscript forintellectual content

Johannes PrudloMD PhD

Rostock UniversityMedical Center Germany

Major role in theacquisition of data

Christian AVedeler MD PhD

Haukeland UniversityHospital Bergen Norway

Major role in theacquisition of data

Julio PardoFernandez MDPhD

Hospital ClınicoUniversitario deSantiago Spain

Major role in theacquisition of data

Monica PovedanoPanades MD

Hospital Universitari deBellvitge BarcelonaSpain

Major role in theacquisition of data

Maria A AlbertıAguilo MD

Hospital Universitari deBellvitge Barcelona Spain

Major role in theacquisition of data

Eleonora DallaBella MD

Fondazione IRCCSInstitute NeurologicoCarlo Besta Milan Italy

Major role in theacquisition of data

Giuseppe LauriaMD

Fondazione IRCCS InstituteNeurologico Carlo BestaMilan Italy and Universityof Milan Italy

Major role in theacquisition of data

Wladimir BVRPinto MD

Federal University of SatildeoPaulo (UNIFESP) Brazil

Major role in theacquisition of data

Paulo VS de SouzaMD

Federal University of SatildeoPaulo (UNIFESP) Brazil

Major role in theacquisition of data

Acary SB OliveiraMD PhD

Federal University of SatildeoPaulo (UNIFESP) Brazil

Major role in theacquisition of data

Camilo Toro MD NIH Bethesda USA Major role in theacquisition of data

Joost van IerselBsC

University MedicalCenter Utrecht theNetherlands

Role in the acquisition ofdata

Malu Parson MsC University MedicalCenter Utrecht theNetherlands

Role in the acquisition ofdata

Oliver HarschnitzMD PhD

Memorial Sloan KetteringCancer Center NY USA

Interpreted the dataand revised themanuscript forintellectual content

Leonard H van denBerg MD PhD

University MedicalCenter Utrecht theNetherlands

Interpreted the data andrevised the manuscriptfor intellectual content

Jan H Veldink MDPhD

University MedicalCenter Utrecht theNetherlands

Interpreted the data andrevised the manuscriptfor intellectual content

Ammar Al-ChalabiMD PhD

Kingrsquos College HospitalNHS London UK

Interpreted the data andrevised the manuscriptfor intellectual content

Peter N LeighFMedSci PhD

Brighton amp SussexMedical School UK

Interpreted the data andrevised the manuscriptfor intellectual content

Michael A van EsMD PhD

University MedicalCenter Utrecht theNetherlands

Interpreted the data andrevised the manuscriptfor intellectual content

NeurologyorgCP Neurology Clinical Practice | Volume 11 Number 2 | April 2021 157

DOI 101212CPJ0000000000000834202111147-157 Published Online before print April 8 2020Neurol Clin Pract

Eva MJ de Boer Andrew W Barritt Marwa Elamin et al Pathophysiology

Facial Onset Sensory and Motor Neuronopathy New Cases Cognitive Changes and

This information is current as of April 8 2020

ServicesUpdated Information amp

httpcpneurologyorgcontent112147fullhtmlincluding high resolution figures can be found at

References httpcpneurologyorgcontent112147fullhtmlref-list-1

This article cites 36 articles 3 of which you can access for free at

Subspecialty Collections

httpcpneurologyorgcgicollectionfrontotemporal_dementiaFrontotemporal dementia

httpcpneurologyorgcgicollectionamyotrophic_lateral_sclerosis_Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

httpcpneurologyorgcgicollectionall_neuromuscular_diseaseAll Neuromuscular Diseasefollowing collection(s) This article along with others on similar topics appears in the

Permissions amp Licensing

httpcpneurologyorgmiscaboutxhtmlpermissionsits entirety can be found online atInformation about reproducing this article in parts (figurestables) or in

Reprints

httpcpneurologyorgmiscaddirxhtmlreprintsusInformation about ordering reprints can be found online

reserved Print ISSN 2163-0402 Online ISSN 2163-0933Published by Wolters Kluwer Health Inc on behalf of the American Academy of Neurology All rightssince 2011 it is now a bimonthly with 6 issues per year Copyright Copyright copy 2020 The Author(s)

is an official journal of the American Academy of Neurology Published continuouslyNeurol Clin Pract

numbness arising within the trigeminal nerve distributionwhich slowly spreads to the scalp and thereafter descends tothe neck upper trunk upper extremities and in some casesto the lower extremities The initial sensory disturbance maybegin in a perioral location or affect one or more of thetrigeminal branches unilaterally and then become bilateralor be bilateral from the beginning Lower motor neuronfeatures present later or concurrently with the sensory defi-cits These include dysphagia dysarthria fasciculationsmuscle weakness and muscle atrophy along the samerostral-caudal direction2 In general only the lower motorneuron system is involved although upper motor neuronsigns have been reported in a few cases3ndash11

Pathogenesis is uncertain Initial indications suggested an auto-immune basis since autoantibodies have been reported as well asa partial and subjective response to immunotherapy1346812ndash16

The finding of TAR DNA-binding protein (TDP) 43 pa-thology at autopsy in several FOSMNcases however impliesa neurodegenerative mechanism and a likely association withamyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)8ndash1017

The objective of this study is to expand our understanding ofFOSMN by evaluating clinical findings and the natural his-tory of the disease in a larger sample than hitherto availableand to review the current literature

MethodsUpdated Case SeriesFOSMN is an extremely rare disorder with only 38 casesreviewed to date2 We provide an updated case series bydescribing new incident cases and cases identified throughliterature search

Incident cases were seen at the following specialized (neuro-muscular) clinics University Medical Centre Utrecht (TheNetherlands) Brighton and Sussex University HospitalsNHS Trust (UK) Rostock University Hospital (Germany)University Hospital i Politecnic La Fe Valencia (Spain) Uni-versity Hospital Clınico de Santiago (Spain) University Hos-pital de Bellvitge in Barcelona (Spain) University HospitalHaukeland Bergen (Norway) Foundation of the Carlo Besta

Neurological Institute IRCCS Milan (Italy) National HumanGenome Research Institute Bethesda (United States ofAmerica) and the Federal University of Satildeo Paulo (Brazil)

Several patients self-reported to us some through theFOSMN patient organization in which case the treatingphysician was contacted to obtain medical records At pres-ent there are no formal diagnostic criteria for FOSMN Thediagnosis was therefore made based on excluding other po-tential causes and expert opinion

We performed a systematic search of the literature with theobjective of identifying FOSMN cases that were not includedin previous reviews Titles and abstracts were screened andrelevant full-text articles were retrieved Correspondingauthors were also contacted for additional details (figure 1)Published cases not included in reviews before and ourincident cases will be reported separately as novel cases

Clinical DataWe extracted the following data from published cases and themedical records of the incident cases sex age at onset dis-ease duration bulbar signs sensory deficits weakness of ex-tremities uppermotor neuron signs laterality cerebral spinalfluid results antibody testing results of imaging geneticanalysis neurophysiologic evaluation type of therapy andresponse biopsy need for a gastric feeding tube or percuta-neous endoscopic gastrostomy need for noninvasive venti-lation cause of death and autopsy findings

Follow-up data on previously published cases and availablelongitudinal data from the incident cases were included131618

We encoded and stored the data in a secure password-protected database

PathophysiologyThere are 2 leading hypotheses with regard to the cause ofFOSMN namely that it is either a neurodegenerative or anautoimmune disorder From our cases and the literature weextracted data on ancillary investigations response to treat-ment disease course and postmortem findings These datawere subsequently categorized as supportive of a neurode-generative or autoimmune etiology

ResultsUpdated Case Series and Clinical FindingsWe identified a total of 29 incident cases Our literature searchyielded 26 full-text articles reporting on a total of 64 patientswith FOSMN of which 29 were not described in a reviewbefore13ndash1618ndash24 We further identified 7 abstractsposterssupplements reporting on 11 potential cases and 2 articlesmentioning 10 FOSMN cases without further patientcharacteristics2526 After reaching out to the correspondingauthors we received a detailed poster on 7 patients withFOSMN17 We chose not to include the other 14 possible

There are 2 leading hypotheses with

regard to the cause of FOSMN

namely that it is either

a neurodegenerative or an

autoimmune disorder

148 Neurology Clinical Practice | Volume 11 Number 2 | April 2021 NeurologyorgCP

patients with FOSMN due to the limited information in theabstracts This led to a total of 100 patients with FOSMN Themain clinical findings of the 28 cases that had not been reportedpreviously are summarized in table e-1 linkslwwcomCPJA171 The baseline characteristics for all 100 FOSMN cases aredescribed in table 1 Most cases developed progressive sensorydeficits starting in the trigeminal nerve distribution and slowlyspreading to the scalp neck shoulders upper extremities andin a few cases to the lower extremities Later (in some casesconcurrently) lower motor signs developed starting in the faceand spreading through the same pattern as the sensory dis-turbances resulting in bulbar symptoms (dysarthria and dys-phagia) fasciculations atrophy and weakness of the involvedmuscles (figure 2) Asymmetrical presentation of the symp-toms (initially) occurred in 48 of the cases in whom the firstaffected side remained more severely affected as the diseaseprogressed despite involvement of the contralateral side Lowermotor neuron signs were observed in all FOSMN cases Upper

motor neuron signs such as brisk reflexes Babinski sign andclonus were reported in 27 cases3ndash1114

Natural historyThe mean age at onset is approximately 55 years (range 7ndash78years) The rate of progression is highly variable and survivalranges from 14 months to over 46 years13ndash23 Ninety-onepercent of the cases started with progressive facial sensoryimpairment followed by motor involvement In a single casesensory symptoms slowly developed 10 years after onset ofthe motor deficits13 Two patients developed high-frequencysensorineural hearing loss developed which started mid-50s(cases 1 and 2)13 Case 4 from our case series (table e-1linkslwwcomCPJA171) also complained of hearing losshowever results of ancillary investigations were not avail-able Sleeping problems were described in 2 cases case 9 hadsigns suggesting REM sleep behavioral disorder and in case113 this was confirmed by polysomnography (Pseudo)

Figure 1 Summary of the Results from the Literature Search

The search was performed on September 1 2019 using PubMed and EMBASE on articles from January 1 2006 to September 1 2019 reporting on FOSMNTitles and abstracts were screened and relevant full-text articles were retrieved References were screened for additional studies FOSMN = facial onsetsensory and motor neuronopathy

NeurologyorgCP Neurology Clinical Practice | Volume 11 Number 2 | April 2021 149

choreoathetosis was seen in 6 patients (cases 21 22 25 2627 and a literature patient who was followed up on)16

Ninety-seven percent of the patients developed bulbarsymptoms13ndash11131416ndash23 Weight loss resulting from dys-phagia in FOSMN may be severe and in 34 cases gastro-stomy was indicated134781011131416ndash1923 The meandisease duration before placement was 5 (1ndash14) years afteronset of the symptoms Fourteen patients required non-invasive ventilation8111619

Of the 39 patients who died the mean disease duration was75 years Of the known causes of death 23 patients died asa result of progressive bulbar weakness leading to aspirationpneumonia or respiratory failure3578101217202123

Behavioral Changes and Cognitive ImpairmentFive patients developed progressive behavioral changes andwere clinically diagnosed with comorbid behavioral variantfrontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) by the treating neurologistReview of the medical records indeed shows that the Rascovskycriteria are met27 One patient also showed progressive be-havioral changes strongly suggestive of bvFTD but no formaldiagnosis was made Considering FOSMN is a potential mimic(or perhaps even an atypical formal form) of ALS patients arecommonly referred to motor neuron disease (MND) clinicsGiven that ALS and FTD are highly related disorders screeningfor cognitive and behavioral changes has become part of thestandard workup in MND most frequently using the Edin-burgh Cognitive and Behavioral ALS screen (ECAS) There-fore ECAS data for 6 FOSMN cases seen at MND clinicswere available to us (one of the patients diagnosed with bvFTDalso underwent an ECAS) In total neuropsychological datawere available for 11 patients of which 8 demonstrated changeswithin the FTD spectrum (72) Three patients showednormal ECAS results and no behavioral changes

There are no available data on cognition and behavioralchanges in the remaining 89 cases therefore we are unable toprovide an estimate of the frequency of these changes inFOSMN A brief summary of neuropsychological findings ofthese cases is provided in table 2

The first case is a man (patient 1)13 who at age 59 years (17years after onset) began to complain of deteriorating mem-ory for recent events had difficulty planning activities andbecame apathetic with blunted empathy or emotionalresponses thereby meeting the criteria for possible bvFTDCognitive screening using the ECAS did not demonstratememory deficits but did show that he scored under thecutoff for verbal fluency

The second case is a 45-year-old man (patient 7)13 who 12years after onset of FOSMN became very irritable with socialwithdrawal and became obsessive and mildly apathetic Mem-ory for recent events and concentration abilities were also di-minished He also meets the criteria for possible bvFTD

Table 1 Demographics and Characteristics of Patientswith FOSMN

n n tested ina

Patients 100

Male 67

Mean age at onset y (range) 55 (7ndash78)

Mean disease duration ym 82 y

Range 14 mndash46 y

Patients who are still alive 61 (86 y)

Patients who died 39 (75 y)

Male 29 (73 y)

Female 9 (68 y)

Unknown 1 (6 y)

Onset with facial sensory symptoms 91 100

Sensory deficits

Face 96 100

Upper extremities 40 100

Lower extremities 11 100

Motor impairment

Bulbar symptoms 97 100

Upper extremities 77 100

Lower extremities 23 100

Upper motor neuron signs 27 95

Antibodies positive 14

Neurophysiologic tests

Blink reflex abnormal 94 96

EMG DR signs 94 94

NCS SNAP amplitude reduced 53 86

Treatment

Immunotherapy started 48 95

Any form of response 10

GFTPEG placed or indicated 34

Patients deceased 39

Cause of death

Aspiration pneumoniarespiratory failure 23

Refusal of enteral nutrition 1

Lung cancertrauma 2

Unknown 13

Abbreviations DR = degenerationregeneration signs EMG = electromy-ography FOSMN = facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathy GFT =gastric feeding tube NCS = nerve conduction study PEG = percutaneousendoscopic gastronomy SNAP = sensory nerve action potentiala n tested in = number of patients in which having the feature is describedtested

150 Neurology Clinical Practice | Volume 11 Number 2 | April 2021 NeurologyorgCP

Another case with signs of bvFTD is patient 8 At age 69years after 22 years of disease he developed short-termmemory loss aphasia and difficulty following instructionsEpisodes of confused nocturnal wandering occurred soonafter sleep onset during which he held the delusion that hiswife was an imposter and could become aggressive whenchallenged Unfortunately limited information was availablefrom medical records but aphasia and behavioral changeswere the most prominent features in this case It is unclearwhether we should classify this patient as having primaryprogressive aphasia or as cognitive and behavioral impair-ment according to the current Strong criteria for fronto-temporal spectrum disorder in MND28 The latter is a termwhich is applicable to patients with cognitive and behavioralchanges within the spectrum of FTD but that do not meetthe formal criteria Unfortunately the patient died before fullneuropsychological evaluation could be achieved BrainMRIs were normal in all 3 cases

Two patients showed cognitive impairment according to theECAS without behavioral changes Patient 2 and patient 6a Spanishpatientwith brain atrophy predominating in the rightfrontotemporal lobes His ECAS showed mild cognitive im-pairment (executive functioning) and another memoryscreening test (MT) showed mild impairment in long-termepisodic memory Because the ALS-FTD-Q is not validated inSpanish a semistructured ECAS interview and the FRSBEquestionnaire were performed with normal results2429

Differential DiagnosisAt present there is no diagnostic test that can definitivelyconfirm FOSMN nor are there existing diagnostic criteria Thediagnosis is based on expert opinion and relies predominantlyon a history of facial onset sensory symptoms followed by facialweakness and a subsequent cranial-caudal spread of symptoms

Other causes need to be ruled out making FOSMN a diagnosisby exclusion There is considerable heterogeneitywith regard tothe presentation For instance some patients did not seekmedical attention for the facial sensory signs The interval be-tween the onset of facial sensory signs and weakness can rangefrom years to simultaneous onset There was 1 case wheresubtle sensory symptoms only developed 10 years after onset ofthe motor deficits13 The rate of progression differs consider-ably with some patients developing severe bulbar weaknesswithin a year compared with patients with exclusively sensorysymptoms for a decade Therefore disease duration rate ofprogression and chief complaint (sensory motor or both)influence the differential diagnosis and the workup

In patients with isolated sensory signs idiopathic trigeminalneuropathy or a central lesion is themain alternative In cases inwhich bulbar weakness is progressive or the predominant fea-ture ALS (and ALS mimics) needs to be considered particu-larly because it has been suggested that FOSMN is an atypicalform of ALS30 In most cases the differential diagnosis is quiteextensive Table 3 provides an overview of the differential di-agnosis and most relevant additional investigations

Laboratory investigations are generally unremarkable Mildlyelevated CK levels may be found but never exceeding gt5 timesupper limit normal CSF is also normal MRI studies inpatients with FOSMN do not explain the symptoms al-though mild to moderate midcervical cord atrophy has beenreported in several cases bright tongue sign in 3 patients11

and frontotemporal atrophy in 2 patients24

Extensive genetic testing has been performed in various caseswhich included ALS genes (C9orf72 FUS SOD1 TARDBP)oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy (PABPN1) Kennedydisease (AR) panels for spinocerebellar ataxia as well as

Figure 2 Summary Distribution Abnormalities in FOSMN

Distribution of sensory motor and electrophysiologic findings in patients with FOSMN In all 3 pictures the darker color represents the higher amount ofpatients with abnormalities showing the cranial-caudal spreading EMG = electromyography FOSMN = facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathySNAP = sensory nerve action potential

NeurologyorgCP Neurology Clinical Practice | Volume 11 Number 2 | April 2021 151

whole-exome sequencing With a few exceptions (discussedbelow) genetic testing has not given any insight so far

There are several electrophysiologic findings that supporta diagnosis of FOSMN Blink reflexes are abnormal in allcases but 2 cases17 varying from unilateral to bilateraldelayed or absent R1 andor R2 responses Needle elec-tromyography showed signs of denervation andor rein-nervation in all patients spreading in a cranial-caudaldistribution Sensory nerve conduction studies show re-duced sensory nerve action potential amplitudes of the up-per limbs in 62 and in the lower limbs in 4 cases (figure 2)

PathophysiologyThe main hypotheses are that FOSMN is either a neurodegener-ative or an autoimmune disorder We reviewed the literature andextracted data on ancillary investigations response to immune-

modulating treatment genetics disease course and postmortemfindings and subsequently categorized these data as supportive ofa neurodegenerative or autoimmune etiology (table 4) Auto-antibodies were present in 14 patients Three of these cases 1 withlow-positive ANA and anti-Ro 1 with anti-sulfo-glucuronyl par-aglo-boside IgG anti-myelin-associated glycoprotein IgG and thefinal patient with a monoclonal gammopathy responded toimmunotherapy6814 One patient had apparent stabilization ofsymptoms6 1 had partial response of weakness and sensory im-pairment but thereafter had worsening respiratory symptoms8

and in the last patient intravenous immunoglobulin relieved herfacial numbness and improved the blink reflex but motor symp-toms worsened Six other patients also had a form of response toimmunotherapy but did not report positive immunologic studies

In a total of 6 patients with FOSMN an autopsy wasperformed15891723 The pathologic studies show loss of

Table 2 Neuropsychological Profiles of Patients with FOSMN

Patients 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Disease duration at the time of ECAS (y) 17 14 3 4 20 4 NA NA NA NA NA

ECAS cognitive domains NP NP NP NP NP

Language

Verbal fluency X

Executive functioning X X

Memory

Visuospatial X

ECAS behavioral interview X NP NP NP NP NP NP

Behavioral changes NA NA NA NA NA

36 Rascovsky criteria p bvFTD X X X X X

Disinhibition x x x

Apathyinertia x x x

Loss of sympathyempathy x x x x x

Preservativecompulsive x x x x

Hyperorality

Dysexecutive profile x x

Suggestive of bvFTD but noneuropsychological evaluation

X

(Pseudo)choreoathetosis X X X

Abbreviations ECAS = Edinburgh Cognitive and Behavioral ALS Screen FOSMN = facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathy FTD = frontotemporaldementia NA = not applicable NP = not performed p bvFTD = possible behavioral variant FTD according to the Rascovsky criteriaThis table shows the ECAS results (patients 1ndash6) and behavioral changes of patients with FOSMN X represents a score under cutoff for the ECAS domainindicating cognitive impairment and represents the presence of behavioral changesPatients 1 2 and 6 show cognitive impairment according to the ECAS Patients 7ndash11 did not have an ECAS but did have behavioral changes Patients 1 7 9 10and 11 met the criteria for possible bvFTD Patient 8 showed cognitive and behavioral changes suggestive of bvFTD but never had a neurophyschologicalevaluation Patients 3 and 4 did not show abnormalities in the ECAS or behavioral changesPatient 1 (case 1 Broad and Leigh)13 case 2 (case 2 incident cases) case 3 (case 3 incident cases) patient 4 (case 6 incident cases) patient 5 (case 20 incidentcases) patient 6 (Vazquez-Costa et al)24 patient 7 (case 2 Broad and Leigh)13 patient 8 (case 8 case series) patient 9 (Dalla Bella et al)16 patient 10 (case 21incident cases) and patient 11 (case 22 incident cases)

152 Neurology Clinical Practice | Volume 11 Number 2 | April 2021 NeurologyorgCP

motor neurons in the facial nerve nucleus and hypoglossalnucleus and cervical anterior horns and loss of sensory neuronsin the main trigeminal sensory nucleus nucleus of the solitarytract and dorsal root ganglia Four cases had TDP-43ndashpositiveglial inclusions891723 The other 2 cases had no intraneuralinclusions and stained negative for ubiquitin15 Cutaneousnerve and muscle biopsies show a loss of myelinated fibers andWallerian degeneration of the nerves without signs of vasculitisor amyloid deposition145172021 Genetic analysis was positivein 7 cases In 1 case a heterozygous D90A SOD1 mutation(familial ALS) was found There were also 2 cases of a het-erozygous TARDBP mutation1011 of which 1 patient hada positive family history (2 maternal cousins with definitive

genetic diagnosis of ALS andmotherwith FTD)11 There was 1case of a heterozygous mutation in TARDBP and inSQSTM124 Furthermutations foundwere a heterozygousVCPmutation in a patient with a mother with FTD brother withspinal-onset ALS and nephew with IBM11 a patient witha heterozygous CHCHD10 mutation whose mother had bi-lateral eyelid ptosis and Parkinson disease and brother hadchronic exercise intolerance and proximal myopathy11 and 1case with a genetic mutation in the PABPN1 gene (oculo-pharyngeal muscular dystrophy)5 Furthermore 2 patientswith FOSMN were described who underwent whole-exomesequencing without definitive results but had a positive fam-ily history of neurodegenerative diseases a mother with

Table 3 Differential Diagnosis of FOSMN

Disease Tests

Kennedy disease Genetic analysis CAG repeat androgen receptor chromosome Xq11-12

Sjogren disease Anti-Roanti-SS-A anti-Laanti-SS-B

Schirmer test and Saxon test

Lip biopsy

Tangier disease HDL triglycerides and cholesterol spectrum

Nerve biopsy

Genetic analysis ABCA1 gene

Amyloidosis Genetic analysis mutation Gelsolin gene

Syringomyliasyringobulbia MRI of the brain and cervical spine

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Electrodiagnostic studies EMG and NCS

Genetic analysis SOD1 FUS TARBDP and C9orf72 genes

Autoimmune-mediated neuropathy Anti-sulfatide antibodies anti-diasialosyl antibodies anti-ganglioside antibodies (GD1a andGT1a) anti-GD1b ANA ENA anti-SGPG IgG anti-MAG IgG M-protein screening rheumatoidfactor antindashdouble-stranded DNA anti-Sm anti-RNP anti-Scl79 anti-phospholipids and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

Basal meningitis MRI of the brain and CSF

Ischemia MRI of the brain

Myasthenia gravis Antibodies against AChR MuSK or LRP-4

Repetitive nerve stimulation

Sarcoidosis ACE SOL IL-2 receptor

Idiopathic trigeminal neuropathy MRI of the brain

Hereditary motor sensory neuropathy EMG

Genetic analysis CMT subtypes

Infections Serology serum andor CSF HIV Borrelia herpes simplex virus 1ndash2 varicella zoster virusleprosy hepatitis BC and Treponema pallidum

Thyroid dysfunction TSH and free T4

Ocular pharyngeal muscular dystrophy Genetic analysis PABPN1 gene

Brown-Vialetto-Van-Laere syndrome Genetic analysis SLC52A2 and SLC52A3 genes

Fazio-Londe syndrome Genetic analysis SLC52A3 gene

Abbreviations CMT =CharcotMarie Tooth EMG= electromyography FOSMN= facial onset sensory andmotor neuronopathy NCS = nerve conduction study

NeurologyorgCP Neurology Clinical Practice | Volume 11 Number 2 | April 2021 153

FTD-ALS and a maternal aunt and grandmother with Par-kinson disease and a patient with 2 brothers and a mother withALS11 A positive family history was also seen in incident case13 (brother died of ALS) and incident case 16 (FTD) To dateno cases with a positive family history of FOSMN are reported

DiscussionFOSMN is a rare neurologic syndrome with a total of 100documented patients worldwide to date It typically com-mences with a trigeminal distribution sensory disturbance

Table 4 Characteristics of Patients With FOSMN Categorized by Possible Underlying Mechanism

Neurodegenerative mechanism Autoimmune mechanism

No positive immunologic studies arementioned in 72 cases of CSF analysis andimmunologic studies in serum are negativein 7890 (87) Positive immunologic studies (13)

Immunologic studies n cases positive n cases tested

Antinuclear antibody 5 55

Anti-sulfatide IgG 3 17

Anti-MAG IgG 2 19

Monoclonal gammopathy 3 6

Anti-GD1b antibodies 1 33

Anti-Ro 1 43

Anti-dsDNA 1 (slightly) 27

No response to immunotherapy in mostcases

(Partial) response to immunotherapy

IVIg treatment in 44 cases (20 response)

Stabilization in 1 case6

Partial recovery in 4 cases3814

Response to the first treatment but not to the second course of treatment in 1 case12

Temporary improvement of blink reflex in 2 cases18

Steroids treatment in 15 cases

Partial response in 1 case8

Plasma exchange treatment in 6 cases

Improvement and no further progression in 1 case12

MRI shows a bright tongue sign in 3patients11 and frontotemporal atrophy in2 patients24

MRI of the brain and cervical spine showsno signs of inflammation

2 cases with a positive family history ofALSFTD-ALS11

Positive genetic testing heterozygousSOD1 mutation (n = 1)16 heterozygousTARDBPmutation (n = 2)1011 heterozygousTARDBP and SQSTM1 mutations (n = 1)24

heterozygous VCP mutation (n = 1)11 andheterozygous CHCHD10 mutation (n = 1)11

46 autopsies had TDP-43 intraneuralinclusions891723

66 autopsy cases reported sensory andmotor neuronal degeneration15891723

Abbreviations ALS = amyotrophic lateral sclerosis FTD = frontotemporal dementia FOSMN = facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathyIVIg = intravenous immunoglobulin TDP = TAR DNA-binding protein

154 Neurology Clinical Practice | Volume 11 Number 2 | April 2021 NeurologyorgCP

which progressively engulfs the head neck trunk and upperand lower extremities It is followed by motor weaknessspreading along the same craniocaudal distribution pro-gressing to bulbar symptoms weakness of the extremitiesand respiratory motor impairment (figure 2) Over thecourse of the disease patients with FOSMN develop dys-phagia leading to severe weight loss (requiring gastronomy)as well as sometimes fatal aspiration pneumonia Causes ofdeath in FOSMN are similar to ALS adding to the view thatthere is overlap between the 2 conditions

Hitherto little attention has been paid to the presence ofbehavioral and cognitive changes in patients with FOSMNSix cases are described to have behavioral changes suggestiveof bvFTD In 2 patients without behavioral changes evidencefor executive dysfunction was seen on the ECAS It seemsthat behavioral changes and cognitive changes within theFTD spectrum may occur in patients with long disease du-ration expanding the phenotype of FOSMN Additionalneuropsychological research in FOSMN seems warranted tobetter understand these cognitive and behavioral changes

Because the cause of FOSMN is unknown there is no testthat definitively confirms this diagnosis Patients are there-fore diagnosed based on expert opinion and by excludingother disorders that could cause comparable symptomsBecause there are no formal diagnostic criteria we cannot besure that all documented patients indeed have FOSMNThree patients have no sensory symptoms and 1 patient onlyhas sensory symptoms in the lower extremities They dohowever all have abnormal blink reflexes indicating tri-geminal involvement Until consensus is reached on formaldiagnostic criteria that have been validated the diagnosis isbased on expert opinion potentially causing bias in thepresent findings

Thus far the pathogenesis of FOSMN has remained elusiveThere are 2 main hypotheses It has been suggested that theunderlying mechanism may be either autoimmune mediatedor neurodegenerative

An autoimmune origin is supported by the fact that autoanti-bodieswerepresent in14patientswithFOSMN Itmust benotedthat the panel of antibodies that was tested varied considerablybetween cases and that therefore the percentage of positive casescould be an underestimation or that yet unidentified antibodiesare involved However there seems to be little consistency in thedetected antibodies and several of these antibodies are associated