Extensor Tendons Injuries 2015 Clinics in Sports Medicine

-

Upload

professeur-christian-dumontier -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

0

Transcript of Extensor Tendons Injuries 2015 Clinics in Sports Medicine

-

8/20/2019 Extensor Tendons Injuries 2015 Clinics in Sports Medicine

1/14

Extens or Tendons I nj uri es

John T. McMurtry, MDa, Jonathan Isaacs, MDb,*

EXTENSOR TENDON INJURIES IN ATHLETES

Injuries to the extensor tendons of the hand can cause significant deformity anddisability in some cases, and in others can be relatively well tolerated. The anatomy

of the extensor tendons is quite intricate and an intimate knowledge is essential for

diagnosis and treatment. Unique to extensor tendon avulsion injuries, deformity and

disability may be initially minimized or ignored by athletes so that late presentation

is not uncommon. Many acute injuries can be treated conservatively and often in a

way that allows continued sports participation. Once a chronic deformity develops,

treatment options become more complex and less predictable. More chronic injuries,

such as sagittal band attrition, may have greater impact on certain activities and defin-

itive treatment is necessary to even continue sport participation. This article discusses

the diagnosis, management, and definitive treatment of mallet, boutonniere, andsagittal band injuries in athletes.

Basic Anatomy

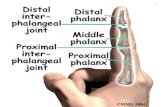

The distal aspect of the upper extremity digits represents a complex confluence of

tendons, ligaments, and bone. The basic musculature of the hand and digits can be

broken down into two categories: extrinsic and intrinsic musculature.

a Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Virginia Commonwealth University Health System, 1200

East Broad Street, 9th Floor East Wing, Richmond, VA 23298, USA;

b

Division of Hand Surgery,Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Virginia Commonwealth University Health System, 1200East Broad Street, 9th Floor East Wing, Richmond, VA 23298, USA* Corresponding author.E-mail address: [email protected]

KEYWORDS

Extensor tendon Mallet finger injury Boutonniere deformity Sagittal band injury

KEY POINTS

Athletes with suspected extensor tendon injuries should be promptly evaluated and begin

treatment to achieve acceptable outcomes.

Most closed extensor tendon injuries can be treated conservatively in the acute phase, but

chronic injuries often require operative intervention.

With the appropriate postinjury management and therapy the athlete can expect a safe

and successful return to activity.

Premature return to competition with inadequate healing and protection compromises

long-term outcomes.

Clin Sports Med 34 (2015) 167–180http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.csm.2014.09.005 sportsmed.theclinics.com0278-5919/15/$ – see front matter 2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

mailto:[email protected]://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.csm.2014.09.005http://sportsmed.theclinics.com/http://sportsmed.theclinics.com/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.csm.2014.09.005http://crossmark.crossref.org/dialog/?doi=10.1016/j.csm.2014.09.005&domain=pdfmailto:[email protected]

-

8/20/2019 Extensor Tendons Injuries 2015 Clinics in Sports Medicine

2/14

Extrinsic Musculature

The extrinsic forearm extensor musculature gives rise to tendons that pass deep to the

extensor retinaculum to insert at the bases of the middle and distal phalanges. The

extrasynovial nature of the extensor tendons distal to the wrist minimizes the tendency

for retraction and often allows splint treatment even for complete ruptures.1

Theextensor tendons originating from the extrinsic musculature are joined by the contri-

butions of the intrinsic muscles at the metacarpal-phalangeal (MCP) joints. Primarily,

the extension movement at the MCP joint is caused by extrinsic derived forces deliv-

ered via the sagittal bands, which wrap around the base of the proximal phalanx and

insert onto the volar plate.

Intrinsic Musculature

The intrinsic muscles of the hand begin their contribution just distal to the MCP joints

as the conjoined tendons of the intrinsic muscles join the extensor tendon proper

through the lateral bands.2 Three bands, the central slip (as a continuation of theextrinsic extensor system) and the two lateral bands, continue distally.3,4 The central

slip (along with essential contributions from the lateral bands) inserts over the prox-

imal portion of the middle phalanx to control extension at the proximal interphalan-

geal (PIP) joint. Proper position of the lateral bands is necessary for active PIP

extension. The triangular ligament resists palmar subluxation, and the transverse

retinacular ligaments prevent dorsal band displacement. The most distal aspects

of the lateral bands converge to form the terminal tendon insertion at the proximal

aspect of the distal phalanx. Active extension at the PIP and distal interphalangeal

(DIP) joints is mostly generated through the intrinsic hand muscles (although these

forces are transmitted through their connections with the extrinsic extensor tendon

system).

MALLET FINGER

Introduction

The mallet finger has been classically described as a terminal extensor tendon discon-

tinuity with resultant extensor lag at the DIP joint. This frequently encountered sporting

injury has been termed a “drop finger” or “baseball finger” and has an estimated inci-

dence of approximately 10 cases per 100,000 injuries occurring most commonly in thelong, ring, and little fingers.1,5–8 The mechanism of injury is forced flexion of an

extended finger causing avulsion of the terminal extensor tendon with or without a

chunk of bone from the distal phalanx.9

Classification and Evaluation

Mallet injuries are typically obvious when the athlete presents with an inability to

actively extend the DIP joint. When the bone is not involved, these can be remarkably

painless. However, dorsal DIP joint pain, swelling, and contusing with intact passive

motion are all common findings. Importantly, the digit should be tested for PIP joint

hyperextension because this can predispose the patient to a secondary swan neckdeformity, which may be more functionally significant than a fixed flexion deformity

at only the DIP joint.5 Radiographic assessment should reveal osseous involvement,

which if present could impact the choice of treatments.

Although there are several classifications of mallet finger injuries, the critical division

points relevant to the treatment of athletes generally are bony verses soft tissue only

and, if bony, the percentage of joint surface involved (more or

-

8/20/2019 Extensor Tendons Injuries 2015 Clinics in Sports Medicine

3/14

Initial Conservative Management

The goals of treatment rest on ensuring that the tendon heals as close as possible to

the anatomic position and to recreate a congruent joint to minimize any residual

extensor lag.5 In most cases of mallet finger with or without bony involvement, this

can be accomplished by full-time splinting of the DIP joint. Typically, the PIP joint isnot included in the splint but the DIP joint must remain passively extended at all times

for 6 to 8 weeks.10–13 If at any point during this time the finger is not kept in full exten-

sion, the fragile healing tendon tissue is disrupted, and the patient must begin the

treatment of immobilization anew.12 After 6 to 8 weeks of full-time splinting the patient

is transitioned to 6 weeks of night splinting (plus splinting during strenuous activ-

ities).14–17 Most agree that bony involvement of 30% to 40% of the articular surface

can still be effectively treated in an analogous manner,18–20 although good results

have been reported with conservative treatment of larger bony injuries with or without

joint subluxation.16 Regardless of the type of injury, if splinting is chosen as the treat-

ment of choice the clinical result depends on patient compliance.11,17,18

The choice of splints should be based on comfort and expected compliance

because multiple studies have failed to demonstrate any clinical difference. Dorsal

maceration especially with an athlete’s perspiration is a concern and alternating be-

tween two different style splints (as long as the DIP joint is passively held in extension

during the exchange) can be an effective strategy.10,11,17,21,22 A useful approach,

particularly for an athlete, is to combine kinesiotape with an orthosis to facilitate hold-

ing the DIP joint in extension23 even during activity. If the athlete can perform with the

splint on, they can continue to participate with the DIP joint effectively protected. If hy-

perextension is occurring at the PIP joint, however, the splint should be extended

proximally to maintain slight PIP flexion, although certainly this increased cumber-someness is more likely to interfere with athletic competition.

Surgical Correction of Acute Mallet Finger

Several accepted indications for surgical treatment of acute mallet finger injuries

include fractures of greater than 40% of the DIP joint articular surface, volar subluxa-

tion of the distal phalanx, and patients unable to tolerate splint therapy.5,12,18,19,24–29

With a fracture involving greater than 40% of the articular surface the possibility of

volar subluxation is increased, which in turn leads to a greater incidence of swan

neck deformity, extensor lag, degenerative joint changes, and a dorsal joint promi-nence.16,26,28,29 With this in mind, recent biomechanic studies confirmed the clinical

observations of Wehbe and Schneider that DIP joint subluxation occurs with greater

than 40% to 50% articular surface involvement.7,30

Closed Reduction with Percutaneous Fixation for Surgical Correction of Acute Mallet

Finger

For simple soft tissue avulsions or bony injuries without subluxation, Kirschner wire

(K-wire) immobilization may offer the opportunity to return to sport without the strict

need for splinting.31 A simple transarticular K-wire placed longitudinally in retrograde

fashion through the distal phalanx and into the middle phalanx immobilizes the DIP joint ( Fig. 1 ). The K-wire is then cut off subcutaneously with delayed removal in 6 to

8 weeks (although continued nighttime splinting is still necessary for an additional

2–6 weeks).12,13

Bony mallet fingers with joint subluxation also can be reduced and pinned

with27,32–34 or without fracture fragment fixation,35 compression pinning,34,36 or exten-

sion block pinning.32,36–41 These more complex repairs requiring exposed K-wires,

Extensor Tendons Injuries 169

-

8/20/2019 Extensor Tendons Injuries 2015 Clinics in Sports Medicine

4/14

however, are not compatible with immediate return to sport because of infection risk

and susceptibility for pin dislodgment.

Initial Conservative Management of Chronic Mallet Finger

A mallet finger is classified as chronic when it is greater than 4 weeks from the date of

injury. The tenets of treating acute mallet finger continue to hold true when treating

early chronic mallet finger because splinting is still the treatment of choice for up to

3 months after injury.42 This is particularly relevant to the athlete patient who may

choose to delay treatment until the end of the season. Splinting for chronic mallet

finger injuries demonstrates equivalent outcomes to acute mallet finger injuries with

an end treatment extensor lag of less than 10 degrees.18

Surgical Correction of Chronic Mallet Finger

Chronic mallet fingers are typically well tolerated as long as secondary swan necking

does not occur. This complication, however, could certainly be disruptive to an athlete

and most likely requires further treatment. Options include a spiral oblique retinacular

ligament reconstruction43 or a central slip tenotomy.44 Lin and Strauch45 recommend

using a central slip tenotomy for extensor lags up to 40 degrees, but the clinician must

wait until 6 months after injury for pseudotendon tissue (at the site of initial tendon

disruption) to mature.46

The consequences of not undergoing treatment (chronic mallet finger, swan neck

deformity, pain) must be thoroughly discussed with the athlete if they are unable toparticipate with the finger in a splinted position. The choice of delayed treatment of

an athlete during the competitive season who cannot participate with the DIP joint

splinted or pinned is not unreasonable because splinting can still be effective if begun

within 3 to 4 months.47,48 If even this is not possible for the athlete, the consequences

of a chronic mallet finger may be well tolerated and many can return to sport without

concern.

Fig. 1. Lateral ( A) and anteroposterior (B) views of pinned mallet finger. Note that pin isbelow skin to allow continued activity with that hand.

McMurtry & Isaacs170

-

8/20/2019 Extensor Tendons Injuries 2015 Clinics in Sports Medicine

5/14

BOUTONNIERE DEFORMITY

Introduction

A Boutonniere deformity occurs because of disruption of the central slip and may be

seen after forced flexion or volar dislocation of the PIP joint. The classic boutonniere

deformity is described as flexion at the PIP joint and hyperextension at the DIP joint asa result of progressive volar displacement of the lateral bands. This lateral band migra-

tion occurs as the triangular ligament just distal to the central slip insertion gradually

attenuates2 so the injury pattern is not always recognized acutely. Basketball players

and volleyball players are the most common athletes to sustain this injury.49

Classification and Evaluation

The boutonniere deformity is commonly broken down into acute versus chronic and

true versus pseudo deformity. Like mallet injuries, the extensor tendon can pull off a

chunk of bone and the degree of bony involvement is a critical factor in determining

treatment.50 For soft tissue injuries, staging is related to the level of contracture atthe PIP joint and loss of movement at the DIP joint.51,52 In the initial stage, the finger

displays full and painless range of motion at the DIP joint with mild swelling and

pain at the PIP joint. Stage two progresses to passively correctible PIP flexion defor-

mity with hyperextension at the DIP joint. With stage three, the PIP contracture is only

partially correctible and the DIP has minimal or no flexion. The PIP and DIP joints sub-

sequently develop fixed contractures and arthritic articular changes, which represents

the fourth and final stage.51,52

Injury to the central slip should be considered with any PIP injury and is pathogno-

monic of a volar PIP dislocation. Initial examination should attempt to illicit focal

tenderness at the central slip insertion as opposed to global pain as is often the

case with a bad PIP injury. The resting position of the finger may be affected and an

extension lag or even weakness with extension are important physical findings,

although extension may initially still be possible through the intact lateral bands.

The Elson test, although not perfect, is the most reliable physical examination method

of evaluation of central slip injuries and is performed by assessing active DIP extension

with the PIP joint in flexion.53 Any active extension at the DIP joint with the PIP joint

held flexed in 90 degrees of flexion indicates a complete central slip rupture.54 With

an intact central slip insertion, flexion of the PIP joint creates laxity in the more distal

extensor mechanism. If the central slip is disrupted, even with the PIP flexed, the pa-

tient is able to pull the extensor system proximal and transmit an extension force to the

DIP joint. The clinician must also distinguish this injury from a pseudoboutonniere

deformity, which displays a flexed PIP without resultant increased DIP extensor

tone and indicates volar plate scarring and contracture after PIP sprain. Plain radio-

graphs assess the presence and/or degree of bony involvement in addition to joint

reduction and alignment.

Initial Conservative Management

Successful treatment depends on ensuring that the tendon heals as close as possible

to its anatomic position. In the acute setting, the true goal of treatment is to allowtendon healing before the boutonniere deformity has had a chance to develop.55

The initial treatment of choice is PIP joint extension splinting with the DIP joints left un-

restrained.56 Active and passive DIP flexion decreases stiffness and helps pull the

lateral bands dorsally to their normal position ( Fig. 2 ). PIP immobilization is maintained

full time for 4 to 6 weeks and then transitioned to partial or night-time splinting.2,51 A

nondisplaced fracture at the central slip insertion does not alter this recommendation,

Extensor Tendons Injuries 171

-

8/20/2019 Extensor Tendons Injuries 2015 Clinics in Sports Medicine

6/14

although a large unreduced bony fragment does not heal with this protocol and should

be fixed.51 In the absence of fixed contracture, subacute central slip injuries up to

6 weeks old can still be successfully treated nonoperatively.49,57 As with the malletfinger, this may be a consideration in a patient athlete close to completing the season.

Otherwise, if treatment is to be initiated (and we always recommend that it is), then the

decision to return to play is based on the athlete’s ability to wear an extension PIP

splint while participating.58 This is possible in only a few sports, although we have

had runners and even lacrosse players that could continue competing while undergo-

ing treatment ( Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 2. Custom fabricated splint for treatment of boutonniere injury. ( A) Splint in full protec-tive position. Ability to release DIP joint (B) to allow active DIP flexion (C ).

McMurtry & Isaacs172

-

8/20/2019 Extensor Tendons Injuries 2015 Clinics in Sports Medicine

7/14

The published clinical outcomes of conservative management are extremely limitedbut demonstrate overall satisfactory results. In a small review of patients with central

slip injuries treated with extension splinting, approximately 70% of closed injuries

achieved satisfactory results.59,60 At present we found no studies that have compared

nonsurgical with surgical treatment.

Acute Surgical Management

Acute central slip injuries are infrequently treated with surgical means unless they are

an open injury or associated with a fracture. Dorsal lip fractures of the middle phalanx

may be part of the spectrum of PIP fracture or dislocation injuries and can be classified

as stable or unstable with most fractures involving less than 50% of the articular sur-

face being stable.61 Stability is represented by complete reduction in full extension,

whereas palmar subluxation or frank dislocation in extension represents an unstable

injury.62 Pure avulsion fractures are typically repaired when displaced more than

2 mm.63 Larger fragments can be secured with screw fixation, whereas small bone

fragments not amenable to screw fixation can be surgically repaired to the bone after

fragment excision.61 As with conservative management, the goal is to achieve central

slip continuity and a concentric PIP joint. If the fracture fragment is large enough,

closed reduction with percutaneous pinning can provide an acceptable reduction,

although this would preclude further athletic participation until the pin is removed.64,65

After surgical fixation patients are protected for approximately 4 to 6 weeks, although

depending on the quality of fixation, some authors recommend early, protected range

of motion.63,66

Chronic Boutonniere Deformity

Chronic boutonniere deformities may occur more commonly in athletes because many

of them dismiss the injury initially to continue athletic participation and only present

once deformity has adversely affected their ability to perform. If a fixed deformity

(not passively correctable) has already formed, the first step is to create a supple or

passively correctable deformity. Depending on the level of contracture the patientoften undergoes extension splinting and/or sequential finger casting.55,67 In the early

stages of posttraumatic boutonniere deformity, the PIP contracture is flexible and se-

rial extension splinting either full time or only at night helps to restore normal anatomy.

In addition to splinting, active PIP extension and DIP flexion are advocated to stretch

the tight volar structures and stretch the lateral bands respectively.55 As deformity and

contracture progress, it becomes more difficult to restore normal anatomy with

Fig. 3. Low-profile splint allows player with boutonniere injury to continue participating inlacrosse.

Extensor Tendons Injuries 173

-

8/20/2019 Extensor Tendons Injuries 2015 Clinics in Sports Medicine

8/14

splinting or casting and surgical release (volar plate release) or application of a dy-

namic external fixation (such as the Agee Digit Widget, Hand Biomechanics Lab,

Inc, Sacramento, CA) may be necessary ( Fig. 4 ). The more severe the contracture,

the more difficult is the eventual reconstruction.68

A chronic supple deformity can be treated by a variety of surgical procedures

without a current gold standard, although we favor the four-stage surgical algorithm

established by Curtis and colleagues.57 After each stage of treatment, quality of

correction was evaluated and if not acceptable the next stage was initiated. Patient

participation (under digital block) is helpful in the assessment.60 The treatment steps

are as follows: (1) extensor tendon tenolysis and transverse retinacular ligament mobi-

lization; (2) transverse retinacular ligament release; (3) extensor tenotomy (as

described by Dolphin) plus lateral band lengthening; and (4) central slip reconstruc-

tion.51,57,60 Patients treated with stages one through three achieved improved out-

comes compared with patients requiring stage four interventions. The Dolphin

extensor tenotomy involves incising the extensor tendon distal to the triangular liga-

ment to allow migration of the extensor mechanism proximally to recreate tension

at the central slip insertion.69 Most patients have a well-tolerated DIP extensor lag,

but this is minimized by sparing the oblique retinacular ligament.70

Multiple techniques have been described to reconstruct the central slip. Excising up

to 3 mm of the central slip pseudotendon and then performing an end-to-end repair

can work but risks loss of flexion despite mobilization.71,72 Using the lateral bands

was first described by Matev in 1964 and has demonstrated reasonable results.73–76

The Matev technique consists of sectioning of one of the lateral bands at the base of

the middle phalanx and attaching the proximal aspect to the distal remnant of the cen-

tral slip on the middle phalanx. The remaining lateral band is sectioned distally over themiddle phalanx then reattached to the distal stump of the first sectioned lateral

band.60,73,75 This procedure restores the function of the central slip and improves

DIP joint motion, but can also result in PIP flexion deficit, subluxation of distal extensor

mechanism, and DIP joint extensor lag.73,76 The lateral bands also can be split longi-

tudinally and transposed dorsally to reestablish a central band.71,77,78

The outcomes of chronic boutonniere reconstruction are not as good as acute treat-

ment. Universally, surgical treatment of chronic boutonniere injuries necessitates

Fig. 4. Dynamic external fixator applies a strong extension force to contracted PIP joint toachieve passive extension. The goal of this effort is to turn a rigid boutonniere injury intoa supple injury so that extensor tendon reconstruction can be performed.

McMurtry & Isaacs174

-

8/20/2019 Extensor Tendons Injuries 2015 Clinics in Sports Medicine

9/14

increased dissection, more complex extensor reconstructions, and results in

decreased range of motion.63,64,72 Loss of flexion at the PIP is a real and potentially

harmful risk of this approach and this must be kept in mind when counseling a patient

on the risk/benefit ratio of foregoing acute treatment.

Arthritic or chronically neglected deformities should be left alone or fused, although

for an elite athlete, neither may be desirable options.

SAGITTAL BAND INJURY

Introduction

Injury to the sagittal bands restraining the central extrinsic extensor tendon has been

described as boxer’s knuckle.79 Injury to the extensor mechanism over the MCP is

often caused by blunt trauma and can cause significant disability to an athlete,

more specifically a boxer.80 The sagittal bands are composed of transverse, sagittal,

and oblique fibers that divide over the extensor tendon into deep and superficial com-

ponents.81

The central fingers are more susceptible to injury because of a thinner su-perficial layer, longer radial fibers, more prominent underlying bone, less shared

extensor tendons, and less common juncturae tendinum.82,83 The mechanism of injury

to this sophisticated extensor structure is forceful dorsal pressure over the MCP joint

with the hand in a clenched fist.84

Classification and Evaluation

This injury often presents with some extensor weakness, painful subluxation of the

central tendon, and tenderness to palpation over the damaged sagittal band.81 The

deformity is passively correctable and no significant radiographic findings assist

with the acute diagnosis. In chronic boxer’s knuckles injuries, continued trauma tothe MCP joint predisposes the patient to develop degenerative joint disease second-

ary to osteochondral fracture and chondromalacia.84 Sagittal band injuries are classi-

fied into three groups ranging from no extensor tendon instability, to tendon

subluxation, and finally to tendon dislocation.82 The central tendon often dislocates

ulnarly because the radial band is more susceptible to rupture due to anatomic weak-

ness and the tendency for the MCP joint to be deviated ulnarly at baseline ( Fig. 5 ).85

Fig. 5. Boxer’s knuckle in middle finger. Extensor tendon subluxed ulnarly ( A) and passivelyreduced to its normal central position (B).

Extensor Tendons Injuries 175

-

8/20/2019 Extensor Tendons Injuries 2015 Clinics in Sports Medicine

10/14

Initial Conservative Management

The goals of treatment of acute and chronic boxer’s knuckle are to achieve anatomic

healing of the extensor tendon supportive structures to recreate normal full range of

motion. As with other extensor tendon injuries, a trial of conservative therapy to

include extension splinting is often attempted in the acute setting.86

There is no gen-eral consensus related to initial conservative therapy because satisfactory86 and un-

satisfactory87,88 outcomes have been reported. Most physicians elect to treat these

injuries with surgical intervention whether acute or chronic.80,84

Surgical Correction

The patient is a candidate for surgery initially after injury or after failure of conservative

management as demonstrated with continued subluxation, pain, and altered mo-

tion.81 The aim of surgical management is to restore preinjury range of motion and

strength, which is predictably achieved, with direct repair of the ruptured structures.84

In most sagittal band ruptures an associated capsular tear is appreciated, but repair of the capsule is not recommended because of the risks of restricted range of mo-

tion.80,84 After adequate mobilization of the central extensor tendon, the scar tissue

is debrided and primary repair is attempted.81,82,84 Nagaoka and colleagues88 recom-

mended using an extensor retinaculum graft for chronic boxer’s knuckle injury

because excision of scar tissue often results in a large tissue defect. The digit is

held with the MCP joint in 60 to 70 degrees of flexion during the surgery and in the

postoperative splint, which limited tension on the repair.80 The MCP joint is held in

60 degrees of flexion with no active extension for the first 6 weeks, but after this

time an aggressive program of hand therapy increases activate range of mo-

tion.80,81,84 The athlete must be counseled to await return to sport until the woundis healed, strength has been regained, and a full arc of motion is present and pain-

less.84 If the athlete returns to sport too soon there is a great risk of wound complica-

tions and recurrent rupture of the sagittal band.80,88

REFERENCES

1. Doyle JR. Extensor tendons-acute injuries. In: Green DP, Hotchkiss RN,

Pderson WC, editors. Green’s operative hand surgery. 4th edition. New York:

Churchill Livingstone; 1999. p. 1962–87.

2. Chauhan A. Extensor tendon injuries in athletes. Sports Med Arthrosc 2014;22(1):45–55.

3. Moore JR, Weiland AJ, Valdata L. Independent index extension after extensor in-

dicis proprius transfer. J Hand Surg Am 1987;12(2):232–6.

4. Schultz RJ, Furlong J II, Storace A. Detailed anatomy of the extensor mechanism

at the proximal aspect of the finger. J Hand Surg Am 1981;6(5):493–8.

5. Bloom JM, Khouri JS, Hammert WC. Current concepts in the evaluation and treat-

ment of mallet finger injury. Plast Reconstr Surg 2013;132(4):560e–6e.

6. Clayton RA, Court-Brown CM. The epidemiology of musculoskeletal tendinous

and ligamentous injuries. Injury 2008;39(12):1338–44.

7. Wehbé MA, Schneider LH. Mallet fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1984;66:658–69.

8. Baratz ME, Schmidt CC, Hughes TB. Extensor tendon injuries. In: Green DP,

Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, et al, editors. Green’s operative hand surgery.

5th edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005. p. 187–217.

9. Cheung JP, Fung B, Ip WY. Review on mallet finger treatment. Hand Surg 2012;

17(3):439–47.

McMurtry & Isaacs176

http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref1http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref1http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref1http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref2http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref2http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref3http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref3http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref4http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref4http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref5http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref5http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref6http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref6http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref7http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref7http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref7http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref7http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref8http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref8http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref8http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref9http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref9http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref9http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref9http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref8http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref8http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref8http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref7http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref7http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref6http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref6http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref5http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref5http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref4http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref4http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref3http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref3http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref2http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref2http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref1http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref1http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref1

-

8/20/2019 Extensor Tendons Injuries 2015 Clinics in Sports Medicine

11/14

10. Richards SD. A model for the conservative management of mallet finger. J Hand

Surg Br 2004;29(1):61–3.

11. Pike J. Blinded, prospective, randomized clinical trial comparing volar, dorsal,

and custom thermoplastic splinting in treatment of acute mallet finger. J Hand

Surg Am 2010;35(4):580–8.

12. Bendre AA, Hartigan BJ, Kalainov DM. Mallet finger. J Am Acad Orthop Surg

2005;13(5):336–44.

13. Brzezienski MA, Schneider LH. Extensor tendon injuries at the distal interphalan-

geal joint. Hand Clin 1995;11(3):373–86.

14. Simpson D, McQueen MM, Kumar P. Mallet deformity in sport. J Hand Surg Br

2001;26(1):32–3.

15. Hovgaard C, Klareskov B. Alternative conservative treatment of mallet-finger in-

juries by elastic double-finger bandage. J Hand Surg Br 1988;13(2):154–5.

16. Kalainov DM. Nonsurgical treatment of closed mallet finger fractures. J Hand

Surg Am 2005;30(3):580–6.

17. Groth GN, Wilder DM, Young VL. The impact of compliance on the rehabilitation

of patients with mallet finger injuries. J Hand Ther 1994;7(1):21–4 .

18. Garberman SF, Diao E, Peimer CA. Mallet finger: results of early versus delayed

closed treatment. J Hand Surg Am 1994;19(5):850–2.

19. Warren RA, Kay NR, Ferguson DG. Mallet finger: comparison between operative

and conservative management in those cases failing to be cured by splintage.

J Hand Surg Br 1988;13(2):159–60.

20. Stack HG. A modified splint for mallet finger. J Hand Surg Br 1986;11(2):263.

21. Handoll HH, Vaghela MV. Interventions for treating mallet finger injuries. Co-

chrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(3):CD004574.22. O’Brien LJ, Bailey MJ. Single blind, prospective, randomized controlled trial

comparing dorsal aluminum and custom thermoplastic splints to stack splint

for acute mallet finger. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92(2):191–8.

23. Devan D. A novel way of treating mallet finger injuries. J Hand Ther 2014. [Epub

ahead of print].

24. Auchincloss JM. Mallet-finger injuries: a prospective, controlled trial of internal

and external splintage. Hand 1982;14(2):168–73.

25. Bauze A, Bain GI. Internal suture for mallet finger fracture. J Hand Surg Br 1999;

24(6):688–92.

26. Hamas RS, Horrell ED, Pierret GP. Treatment of mallet finger due to intra-articularfracture of the distal phalanx. J Hand Surg Am 1978;3(4):361–3.

27. Badia A, Riano F. A simple fixation method for unstable bony mallet finger. J Hand

Surg Am 2004;29(6):1051–5.

28. Takami H, Takahashi S, Ando M. Operative treatment of mallet finger due to intra-

articular fracture of the distal phalanx. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2000;120(1–2):

9–13.

29. Stark HH. Operative treatment of intra-articular fractures of the dorsal aspect of

the distal phalanx of digits. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1987;69(6):892–6.

30. Husain SN. A biomechanical study of distal interphalangeal joint subluxation after

mallet fracture injury. J Hand Surg Am 2008;33(1):26–30.31. Nakamura K, Nanjyo B. Reassessment of surgery for mallet finger. Plast Reconstr

Surg 1994;93(1):141–9.

32. Lee YH. Two extension block Kirschner wire technique for mallet finger fractures.

J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009;91(11):1478–81.

33. Pegoli L. The Ishiguro extension block technique for the treatment of mallet finger

fracture: indications and clinical results. J Hand Surg Br 2003;28(1):15–7.

Extensor Tendons Injuries 177

http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref10http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref10http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref11http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref11http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref11http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref12http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref12http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref13http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref13http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref14http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref14http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref15http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref15http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref16http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref16http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref17http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref17http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref18http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref18http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref19http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref19http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref19http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref20http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref21http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref21http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref22http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref22http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref22http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref23http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref23http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref24http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref24http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref25http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref25http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref26http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref26http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref27http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref27http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref28http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref28http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref28http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref29http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref29http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref30http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref30http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref31http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref31http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref32http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref32http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref33http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref33http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref33http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref33http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref32http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref32http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref31http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref31http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref30http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref30http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref29http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref29http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref28http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref28http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref28http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref27http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref27http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref26http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref26http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref25http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref25http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref24http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref24http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref23http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref23http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref22http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref22http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref22http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref21http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref21http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref20http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref19http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref19http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref19http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref18http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref18http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref17http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref17http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref16http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref16http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref15http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref15http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref14http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref14http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref13http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref13http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref12http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref12http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref11http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref11http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref11http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref10http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref10

-

8/20/2019 Extensor Tendons Injuries 2015 Clinics in Sports Medicine

12/14

34. Lubahn JD. Mallet finger fractures: a comparison of open and closed technique.

J Hand Surg Am 1989;14(2):394–6.

35. Yamanaka K, Sasaki T. Treatment of mallet fractures using compression fixation

pins. J Hand Surg Br 1999;24(3):358–60.

36. Hofmeister EP. Extension block pinning for large mallet fractures. J Hand Surg

Am 2003;28(3):453–9.

37. Tetik C, Gudemez E. Modification of the extension block Kirschner wire technique

for mallet fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002;404:284–90.

38. Darder-Prats A. Treatment of mallet finger fractures by the extension-block K-wire

technique. J Hand Surg Br 1998;23(6):802–5.

39. Ishiguro T. Extension block with Kirschner wire for fracture dislocation of the distal

interphalangeal joint. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg 1997;1(2):95–102.

40. Rocchi L, Genitiempo M, Fanfani F. Percutaneous fixation of mallet fractures by

the “umbrella handle” technique. J Hand Surg Br 2006;31(4):407–12.

41. Chung DW, Lee JH. Anatomic reduction of mallet fractures using extension block

and additional intrafocal pinning techniques. Clin Orthop Surg 2012;4(1):72–6.

42. Patel MR, Desai SS, Bassini-Lipson L. Conservative management of chronic

mallet finger. J Hand Surg Am 1986;11:570–3.

43. Kanaya K, Wada T, Yamashita T. The Thompson procedure for chronic mallet

finger deformity. J Hand Surg Am 2013;38(7):1295–300.

44. Asghar M, Helm RH. Central slip tenotomy for chronic mallet finger. Surgeon

2013;11(5):264–6.

45. Lin JD, Strauch RJ. Closed soft tissue extensor mechanism injuries (mallet,

boutonniere, and sagittal band). J Hand Surg Am 2014;39(5):1005–11.

46. Suh N, Wolfe SW. Soft tissue mallet finger injuries with delayed treatment. J HandSurg Am 2013;38(9):1803–5.

47. Makhlouf VM, Deek NA. Surgical treatment of chronic mallet finger. Ann Plast

Surg 2011;66(6):670–2.

48. Shin SS. Baseball commentary - tendon ruptures: mallet, FDP. Hand Clin 2012;

28(3):431–2.

49. Weiland AJ. Boutonnière and pulley rupture in elite baseball players. Hand Clin

2012;28(3):447.

50. Imatami J. The central slip attachment fracture. J Hand Surg Br 1997;22(1):

107–9.

51. Marino JT, Lourie GM. Boutonniere and pulley rupture in elite athletes. Hand Clin2012;28(3):437–45.

52. Taleisnik J. Boutonniere deformity. In: Strickland JW, Steichen JB, editors. Difficult

problems in hand surgery. St Louis (MO): CW Mosby; 1982. p. 54–69.

53. Rubin J, Bozentka DJ, Bora FW. Diagnosis of closed central slip injuries: a cadav-

eric analysis of non-invasive tests. J Hand Surg Br 1996;21(5):614–6.

54. Elson RA. Rupture of the central slip of the extensor hood of the finger. A test for

early diagnosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1986;68(2):229–31.

55. Smith DW. Boutonnière and pulley rupture in elite basketball. Hand Clin 2012;

28(3):449–50.

56. Peterson JJ, Bancroft LW. Injuries of the fingers and thumb in the athlete. ClinSports Med 2006;25(3):527–42.

57. Curtis RM, Reid RL, Provost JM. A staged technique for the repair of the traumatic

boutonniere deformity. J Hand Surg Am 1983;8(2):167–71.

58. Lourie GM. Boutonnière and pulley rupture football commentary. Hand Clin 2012;

28(3):451–2.

59. Souter WA. The Boutonniere deformity. J Bone Joint Surg 1967;49B:710–21 .

McMurtry & Isaacs178

http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref34http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref34http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref35http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref35http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref36http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref36http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref37http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref37http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref38http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref38http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref39http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref39http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref40http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref40http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref41http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref41http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref42http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref42http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref43http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref43http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref44http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref44http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref45http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref45http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref46http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref46http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref47http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref47http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref48http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref48http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref49http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref49http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref49http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref49http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref50http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref50http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref51http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref51http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref52http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref52http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref53http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref53http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref54http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref54http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref55http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref55http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref55http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref55http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref56http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref56http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref57http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref57http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref58http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref58http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref58http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref58http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref59http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref59http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref58http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref58http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref57http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref57http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref56http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref56http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref55http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref55http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref54http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref54http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref53http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref53http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref52http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref52http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref51http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref51http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref50http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref50http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref49http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref49http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref48http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref48http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref47http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref47http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref46http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref46http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref45http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref45http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref44http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref44http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref43http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref43http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref42http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref42http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref41http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref41http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref40http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref40http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref39http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref39http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref38http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref38http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref37http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref37http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref36http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref36http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref35http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref35http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref34http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref34

-

8/20/2019 Extensor Tendons Injuries 2015 Clinics in Sports Medicine

13/14

60. To P, Watson JT. Boutonniere deformity. J Hand Surg Am 2011;36(1):139–42.

61. Kang R, Stern PJ. Fracture dislocations of the proximal interphalangeal joint.

J Am Soc Surg Hand 2002;2:47–59.

62. Khouri JS, Bloom JM, Hammert WC. Current trends in the management of prox-

imal interphalangeal joint injuries of the hand. Plast Reconstr Surg 2013;132(5):

1192–204.

63. Elfar J, Mann T. Fracture-dislocations of the proximal interphalangeal joint. J Am

Acad Orthop Surg 2013;21(2):88–98.

64. Rosenstadt BE, Glickel SZ, Lane LB, et al. Palmar fracture dislocation of the prox-

imal interphalangeal joint. J Hand Surg Am 1998;23:811–20.

65. Spinner M, Choi BY. Anterior dislocation of the proximal interphalangeal joint a

cause of rupture of the central slip of the extensor mechanism. J Bone Joint

Surg Am 1970;52(7):1329–36.

66. Tekkis PP. The role of mini-fragment screw fixation in volar dislocations of the

proximal interphalangeal joint. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2001;121(1–2):121–2.

67. El-Sallakh S. Surgical management of chronic boutonniere deformity. Hand Surg

2012;17(3):359–64.

68. Williams K, Terrono AL. Treatment of boutonniere finger deformity in rheumatoid

arthritis. J Hand Surg Am 2011;36(8):1388–93.

69. Dolphin JA. Extensor tenotomy for chronic boutonnière deformity of the finger;

report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg 1965;47A:161–4.

70. Meadows SE, Schneider LH, Sherwyn JH. Treatment of chronic boutonniere

deformity by extensor tenotomy. Hand Clin 1995;11:441–7.

71. Rothwell AG. Repair of the established post traumatic boutonnière deformity.

Hand 1978;3:241–5.72. Grundberg AB. Anatomic repair of boutonniere deformity. Clin Orthop Relat Res

1980;153:226–9.

73. Matev I. Transposition of the lateral slips of the aponeurosis in treatment of long-

standing “boutonniere deformity” of the fingers. Br J Plast Surg 1964;17:281–6.

74. Littler JW, Eaton RG. Redistribution of forces in the correction of the boutonniere

deformity. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1967;49(7):1267–74.

75. Gama C. Results of the Matev operation for correction of boutonniere deformity.

Plast Reconstr Surg 1979;64(3):319–24.

76. Terrill RQ, Groves RJ. Correction of the severe nonrheumatoid chronic bouton-

niére deformity with a modified Matev procedure. J Hand Surg Am 1992;17(5):874–80.

77. Caroli A. Operative treatment of the post-traumatic boutonnière deformity. A

modification of the direct anatomical repair technique. J Hand Surg Br 1990;

15(4):410–5.

78. Pardini AG, Morais MS. Surgical repair of the boutonniere deformity of the fingers.

Hand 1979;11.1:87–92.

79. Gladden JR. Boxer’s knuckle: a preliminary report. Am J Surg 1957;93(3):388–97.

80. Hame SL, Melone CP. Boxer’s knuckle in the professional athlete. Am J Sports

Med 2000;28(6):879–82.

81. Kang L, Carlson MG. Extensor tendon centralization at the metacarpophalangealjoint: surgical technique. J Hand Surg Am 2010;35(7):1194–7.

82. Rayan GM, Murray D. Classification and treatment of closed sagittal band in-

juries. J Hand Surg Am 1994;19(4):590–4.

83. Rayan GM, Murray D, Chung KW, Rohrer M. The extensor retinacular system at

the metacarpophalangeal joint. Anatomical and histological study. J Hand Surg

1997;22B:585–90.

Extensor Tendons Injuries 179

http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref60http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref61http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref61http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref62http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref62http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref62http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref63http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref63http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref64http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref64http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref65http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref65http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref65http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref66http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref66http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref67http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref67http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref68http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref68http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref69http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref69http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref69http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref69http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref70http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref70http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref71http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref71http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref71http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref71http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref72http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref72http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref73http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref73http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref74http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref74http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref75http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref75http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref76http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref76http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref76http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref76http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref76http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref77http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref77http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref77http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref77http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref77http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref78http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref78http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref79http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref80http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref80http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref81http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref81http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref82http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref82http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref83http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref83http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref83http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref83http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref83http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref83http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref82http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref82http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref81http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref81http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref80http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref80http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref79http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref78http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref78http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref77http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref77http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref77http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref76http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref76http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref76http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref75http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref75http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref74http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref74http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref73http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref73http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref72http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref72http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref71http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref71http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref70http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref70http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref69http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref69http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref68http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref68http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref67http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref67http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref66http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref66http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref65http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref65http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref65http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref64http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref64http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref63http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref63http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref62http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref62http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref62http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref61http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref61http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref60

-

8/20/2019 Extensor Tendons Injuries 2015 Clinics in Sports Medicine

14/14

84. Melone CP Jr, Polatsch DB, Beldner S. Disabling hand injuries in boxing: boxer’s

knuckle and traumatic carpal boss. Clin Sports Med 2009;28(4):609–21.

85. Saldana MJ, McGuire RA. Chronic painful subluxation of the metacarpal phalan-

geal joint extensor tendons. J Hand Surg Am 1986;11(3):420–3.

86. Catalano LW III. Closed treatment of nonrheumatoid extensor tendon dislocations

at the metacarpophalangeal joint. J Hand Surg Am 2006;31(2):242–5.

87. Araki S, Ohtani T, Tanaka T. Acute dislocation of the extensor digitorum communis

tendon at the metacarpophalangeal joint. A report of five cases. J Bone Joint

Surg Am 1987;69(4):616–9.

88. Nagaoka M. Extensor retinaculum graft for chronic boxer’s knuckle. J Hand Surg

Am 2006;31(6):947–51.

McMurtry & Isaacs180

http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref84http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref84http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref85http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref85http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref86http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref86http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref87http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref87http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref87http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref88http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref88http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref88http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref88http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref87http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref87http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref87http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref86http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref86http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref85http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref85http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref84http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0278-5919(14)00085-4/sref84