Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

Transcript of Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 1/78

1

Running Head: SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY

Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

Jack W. Turner

GeorgeMason University

[May 2011]

NOTE: Some appendixes removed - JT

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 2/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 2

Table of Contents

Title Page: «««««««««««««««««««««««««..««««««««.1

Table of Contents««««««««««««««««««««««««««..««««..2

Abstract ««««««««««««««««««««««««««««.««««««..5

Introduction ««««««««««««««««««««««««««««.«««.«.6

Rationale««««««««««««««««««««««««««««.«««««.«9

Literature Review««««««««««««««««««««««««..«««««.«9

Brief History of Somalia««««««««««««««««««««...««.«.«9

Forced Migration and Social Discrimination«««««««......................«10

Methods and Procedures««««««««««««««««««««««««««...«11

Qualitative Methodology«««««««««««««««««««««...«««12

Mindfulness and Uncertainty«««««««««««««««««««««««13

Experiencing Muslim Informality««««««««««««««««««15

Co-Researcher Recruitment ««««««««««««««««««««««.«16

Description of Co-Researcher Demographics«««««««««««««««.«.17

Place of Birth, War Memories, and Family Structure««..««««««..«17

Recruiting Through Social Networks«««««««««««.«««««««..«18

Enhancing Trust Through Online Transparency«««.«««««.«««.19

Protecting Confidentiality and Offering Compensation .«« «««.««.«20

Triangulation and Bracketing««««««««««««««.«««««.««.«21

Interview Environments«««««««««««««.«.««««««..«21

Interview Question Creation««««««««««««««.«.««««««...«23

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 3/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 3

Reducing Transcripts into Themes: Orbe¶s Three Phases««««««««««.....24

First Review: Description««««««««««««.«.«««««..«..«24

Second and Third Phases: Reduction and Interpretation..«« ««««.«.25

Co-researcher Involvement««««««««««.«.««..«««««...«25

Results««««««««««««««««««««««««««««..«««««...«27

Theme One: Maintaining Strong Family Bonds««««««««.««««..«..«28

Family Conflicts and Religious Practices««««««««««««.«....«29

Parents Talk and Guidance «««««««««««..«««««««....«30

Civil War and Diaspora«««««««««««...«..«««««««««31

Theme Two: Keep Your Culture««««««««««...«..««««««««.«33

Somali-American Communities: Everybody¶s Watching«.«««««««.34

Qabiil: Intra-Cultural Racism and Politics«««...«..«««««««««35

³Not Black´ and ³Politically Black´ ««««««...«...«.«««««.««36

Theme Three: Keep Your Religion«««««««««...«..««««««««..«37

Wearing Hijab ««««««««««...«..««««««««««««..«38

Theme Four: Privileging Diversity «««««...«..«««««....««««««.«39

The Racial Discrimination Question«...«..«««««..««««....«««.41

Dialectic Relationships with Native African-Americans...... ««««««.«42

Awareness of Racial Hierarchy and Handling It«««......««««««..«44

Discussion««««««««««««««««««««««««««««««.««.«..45

Family Bonds and Somali-American Identity«««««««««««««.«.«...46

Cultural Awareness, Maintenance, and Challenges«««««..««««««.««48

Diversity: Intercultural and Interracial Friendships«««««.««««««««50

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 4/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 4

Islam and Intercultural Friendships«««««««««««««««««...««.53

Religion, Healing, and ³Allah¶s Place´. «««««««««««.««««««.«.53

Privileging Diversity and Intercultural Explorations. ««««««««««.««..55

The Racial Discrimination Question««««««««««..««««««««.«.57

Conclusion««««««««««..«««««««««««««««.««««««««59

Limitations«««««««..«««««««««««««««««««««««61

Implications for Future Research «««««««««««««««««..««..«62

References««««««««««..«««««««««««««««««««....«««.64

Appendix A««««««««««..««««««««««««...««««««...........«.73

Appendix B««««««««««..««««««««««««...««««««««....«.91

Appendix C««««««««««..««««««««««««...««««««...........«.93

Appendix D««««««««««..««««««««««««...«««««««.....«.112

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 5/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 5

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 6/78

6

Abstract

Previous research has suggested that thirteen - to - eighteen year old Somali-Americas must

negotiate several barriers in American culture in order to attain a successful balance between

their Somali culture and mainstream American culture. The barriers include racial stereotypes,

post-9/11 discrimination toward Muslims, and the social status of refugees and immigrants.

This phenomenological project explores how eighteen ± to ± twenty-six year old Somali-

Americans are constructing and negotiating their young adult identities in American culture.

Identity theory provides a holistic explication for the way cultural, interpersonal, and

contextual factors influence the construction and negotiation of Somali-American identity.

A primary goal of the study has been to describe Somali-American¶s interactive experiences of

identity from their standpoint, and in their voices. Results from ten participant interviews

reveal significant themes related to intercultural identity construction and negotiation during

young adulthood. Participants have voiced descriptions of strong family bonds, a sense of

obligation to their culture, commitment to Islamic faith, and an attraction to diverse cultural,

racial, and ethnic social networks. Implications of the results and suggestions for future

research are discussed.

Keywords: Somali-Americans, identity, phenomenology, acculturation, Muslim

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 7/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 7

Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

Previous research in American and Canadian high schools (Forman, 2002; Husain, 2008;

Shepard, 2008) suggests that adolescent children of Somali immigrants experience significant

challenges negotiating cultural and social barriers existing in their daily living environment. In

the United States, thirteen to eighteen year old Somali-Americans are reported to be

marginalized by their religion, race, status as children of immigrants, and their youth (Husain,

2008; Shepard, 2008). This project explores identity construction and negotiation among young

adult Somali-Americans, eighteen to twenty-six year old, and how this process may be related to

the acculturation difficulties reported by Husain (2008) and Shepard (2008).

This project advances beyond adolescence and seeks to answer three basic questions.

First, how do young adult (18 to 26 years old) Somali-Americans construct identities that

function well in communication with non-Somalis and non-Muslims while also functioning

successfully within their Somali culture? Second, what effects have their interactive experiences

with others, within and outside Somali-American groups, had on negotiating and shaping their

identities? Third, what does it mean to be a young adult Somali-American growing up in, and

adapting to, American mainstream culture? By asking these questions, this study also seeks to

describe, from the standpoint of young adult Somali-Americans, ³the diversity within and

between cultures and what makes intercultural contact effective or ineffective´ (Hecht,

Jackson&Ribeau, 2003, p.6.)

Rationale

This investigation is important because it could help researchers, educators, and social

service organizations better understand how young Somali-Americans experience acculturation

between Somali and American culture. The project focuses on providing a space where the

voices and perspectives of young adult Somali-Americans can be heard, valued, and understood

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 8/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 8

by those of us outside their social and cultural borders. Results from this research may reveal

communication approaches and strategies that are more effective at creating satisfying and

successful acculturation experiences for young adult Somali-Americans.

Similar to Orbe and Harris¶s (2006) position on successful interracial communication, I

believe that learning about and accepting similarities and differences between Somali culture and

American culture is necessary to understand how young adult Somali-Americans attain their

personal, professional, and social goals from a marginalized position in the United States. This

project uses a phenomenological approach (Dewitt, 2007; Martinez, 2000; Orbe, 1998;

Sokolowski, 2000), Orbe¶s (1998) co-cultural theory, and the communication theory of identity

(Hecht et al. 2003) to discover, explicate, and value thedifferences and similarities between

Somali and American culture. This trio of theories and methods has provided the necessary depth

and scope to discover and analyze how the noted differences and similarities forge young

Somali-American¶s identities and shape their adaptation to American culture.

First, phenomenology acknowledges the perceived reality of young Somali-Americans as

it is experienced in daily interactions and accepts their lived experience as data (Dewitt, 2007;

Martinez, 2000), which is referred to as capta by Orbe (1998). Second, Orbe¶s co-cultural

methodology serves as a framework for exploring young Somali-American¶s intercultural

communicationexperiences and how this has resulted in their communication choices and

strategies in relation to the dominant culture in the United states. Orbe and Harris (2006) suggest

that the dominant culture privileges white European - American cultural values (P.76). Finally,

Hecht et al.¶s (2003) communication theory of identity provides a holistic explanation for the

way complex cultural, interpersonal, and contextual factors influence the construction and

negotiation of a successful Somali-American identity.

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 9/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 9

This project analyzes personal narratives for essential themes, and presents the themes in

the voices of young adult Somali-Americans. The main purpose of this study has been to

investigate the different ways that young Somali-Americans, as a marginalized group (Orbe,

1998), construct and negotiate their identities between two cultures. Identity is a dynamic nexus

of an individual¶s culture, family relationships, social interactions, and negotiation decisions in

relation to other individuals, social groups, and the existing dominant culture (Hecht et al.,

2003). This project focuses on identity because it is the culmination and inter-relation of

previous value and behavioral decisions that determine an individual¶s current choices

concerning group membership, communication behavior, and personal goals (Hecht et al., 2003;

Ting-Toomey, 2005).

The project has included my own journey across cultural boundaries into the discursive

world of young adult Muslims and Somali-Americans. Impressions of my journey have been

recounted to provide richer description and validation for the project¶s results. I have attended

Muslim Student Association (MSA) (Muslim Student Association, 2007) events at George

Mason University and events sponsored by the Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA)

MSA. I have participated in prayers and lectures on the Quran at the Dar al Hijrah Islamic Center

in Falls Church, Virginia (the Dar al Hijrah Islamic Center, 2001). Ihave also interacted and

exchanged information with young adult Somali-Americans through social networks such as

Facebook (Turner, 2011a) and Blogger (Turner, 2011b).

The remaining content of this paper is divided into five sections, followed by references

and appendices. A brief literature review is followed by a full description of methods and

procedures used to collect data. Next, a results section describes shared themes which have been

reduced from participant¶s interviews, using specific quotes from participants for examples. A

discussion section addresses the interpretations of themes derived from Somali-American co-

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 10/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 10

researcher interviews and triangulates their descriptions with previous research and with publicly

available data from Internet social networks. Finally, a conclusion section reviews major points

elicited from this project, discusses the study¶s limitations, and sums up implications for future

research.

For the remainder of this document, Orbe¶s (1998) co-cultural terms for this project¶s

participants and data derived from participant interviews will be used. Participants in this study

are recognized as co-resear chers who are primary authorities on their lived experiences and their

culture¶s traditions and rituals (Dewitt, 2007; Orbe, 1998). Data produced from co-researcher¶s

interviews and Somali-American online social networks , the accounts ofco-researcher¶s lived

experience and the meanings that co-researchers attach to their experiences, are labeled as

capta(Dewitt, 2007; Orbe, 1998).

Literature Review

This section begins with a brief history of Somali-American¶s ancestral homeland,

Somalia. It then focuses on the common effects of forced migration endemic to the Somali-

American population. Finally, it references unique cultural characteristics and social contexts

that influence identity construction and negotiation by Somali-Americans.

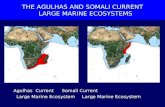

A Brief History of Somalia

In the 1980¶s, an opposition government was formed which eventually pushed

Mohammed SiadBarre, ruler since 1969, out of power in 1991 (CIA Factbook, 2011). Without a

unifying leader or government to keep clan rivalries under control, brutal clan warfare took over

Somalia. Within a year, it was estimated that several hundred thousand people had died, and

another 1.5 million (an estimated one quarter of the population) were on the brink of starvation

(Putnam &Noor, 1993). An estimated one million Somalis had fled to neighboring countries

such as Kenya, Ethiopia, and Yemen (CIA Factbook, 2011; Putnam & Noor, 1993). There has

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 11/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 11

not been a government functioning to serve the whole of Somalia in twenty years (CIA

Factbook, 2011).

Peace has come to Somalia intermittently since 1995, when the United Nations (U.N.)

finally withdrew its occupational forces after years of sustaining casualties. A tentative

government has been assisted by Kenya since 2000, and it now includes a Somali-American

president, Mohammed Abdullahi. The northern-most region of Somalia has declared itself a

separate country named Somaliland, and has enjoyed peace and stability for several years. It

remains to be seen if Somaliland will be recognized diplomatically by the U.N (Maloof&

Sheriff-Ross 2003; CIA The World Fact Book, 2005)

Forced Migration and Social Discrimination.Somali-Americans have experienced

difficulties common to previous refugee and immigrant populations in the United States,

including Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (CDC, Gozdziak, 2002;Maloof& Sheriff-Ross,

2003;Tran &Ferullo, 1997), acculturation stress (Berry, Kim, Minde& Mok,1987; Shepard,

2008) and deficiencies in language fluency and educational skills (Shepard, 2008; Husain, 2008).

Shepard (2008) and Husain (2008) have included Somali-Americans who did not personally

experience war environments and refugee camp living. Shepard and Husain both indicate a

position that young Somalis share common cultural reference points from refugee trauma and

acculturation stress that are passed down in their cultural memory. I have followed the same

reasoning in this project.

Somali-Americans inhabit a marginal position within American culture due to post-9/11

discrimination against Muslims (Muedini, 2009; Sirin& Fine, 2007; Watanabe &Helfand, 2009;

Yee, 2005),continuing racial barriers against people of color (Orbe& Harris, 2006) their status as

the newest, youngest, and poorest African immigrants now living in the United States (Husain,

2008; Shepard, 2005; U.S. Census Bureau, 2000), and a stereotyping negative image in the U.S.

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 12/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 12

news and popular media (Finn &Hosh, 2011; Hedgpeth, 2011). Most anti-Muslim experiences

are reported by people who are of Middle-Eastern descent, or people who have physical

characteristics that are presumed to be Middle-Eastern (head covering, swarthy complexion, and

so on (Boorstein, 2006). However, Shepard (2008) and Husain (2008) recount Somali-American

experiences with anti-Muslim discrimination in U.S. schools, as well as racially-based

discrimination (sometimes from U.S.-born African-Americans). In the mass media and news

programs, Somali-Americans are referenced mostly in terms of Islamic insurgency threats (Finn

&Hosh, 2011) and Somali pirates (Hedgpeth, 2011). These unique and negative factors may

provide a significant burden for young adult Somali-Americans trying to negotiate American

culture successfully.

Methods and Procedures

This project became a concrete plan on October 11, 2011, when I spoke with a local

Imam, a recognized community and religious leader who may also lead prayers (Imam, 2011).

After I described a project about exploring the identity construction of young American

Muslims,Imam Mohammed (a pseudonym) quickly and coherently advised me to focus the study

on Somali-Americans. He said Somali-Americans were all Muslims1 , or at least he had never

heard of, or met, a non-Muslim Somali. Mohammed, who was comfortable being addressed by

his first name, referred me to a local American Muslim professor who had researched Somali-

Americans, and suggested I start attending MSA events.

From that point, I contacted the Muslim professor, who supported my research concept

and also advised me to meet young adult Muslims by attending MSA events. He advised me to

communicate about my research project through these interactions and ask MSA executive

1During this project, every source of information about Somalis, Somali-Americans and Islam-human sources, blogsand online discussions, journal articles and news items- stated that almost all Somali-Americans were Muslim. Noreport of a non-Muslim Somali-American has emerged from any of these sources during this study.

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 13/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 13

committee members if they knew any Somali-Americans. I jokingly referred to this conversation

as ³my marching orders.´

I contacted Muslim Student Association (MSA) officers and other members at George

Mason University and Northern Virginia Community College by attending their scheduled

events. I explained the research project and asked for introductions to Somali-American contacts.

I attended six MSA events over about six weeks to help build a trusting relationship and support

for the research from the MSA community. I also attended six or more prayer meetings at the

Dar al Hijrah mosque to become more familiar with Muslim cultural practices and religious

rituals.

While I was attending Muslim events to make contact with Somali-Americans, I created

an Internet social network presence to reach out beyond the geographic area of northern Virginia

to Somali-Americans in other states. More details about the online web pages used for the project

are in the ³Co-Researcher Recruitment´ section because it became a significant factor in

attracting female Somali-Americans to the study. Another unexpected benefit of the online

promotion was that it created another important reference point for demonstrating respect and

legitimacy to potential co-researchers. The qualitative methods used in the project are discussed

next.

Qualitative Methodology

Following qualitative methodology, specifically phenomenology, I have been the

principal investigator, interviewer, and data collection instrument for this study (Creswell, 1998).

This project¶s data collection demonstrates phenomenological theory in respect to the observer

(me) and the ³object, ´ or phenomenon, being observed, which includes my co-researchers,

Muslim rituals, and so on (Sokolowski, 2000). According to phenomenological theory, the act of

observing and the phenomenon being observed create a dynamic and recursive experience

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 14/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 14

(Sokolowski, 2000). Phenomenology embraces subjectivity and proposes that observation of an

object, or phenomenon, creates an experience of reality that is the total sum of the observer¶s

individual history and culture, the context of the observation (such as time and place), and the

object (Sokolowski, 2000). Thus, the researcher¶s perception of reality is never completely

separated from what, or who, he is studying (Sokolowski, 2000).

An assumption of phenomenology is that researchers are immersed in the lifeworld they

are observing (Orbe, 1998). A phenomenological perspective has guided my exploration of the

religious culture of Somali-Americans as a way to understand and acknowledge how Somali-

American¶s standpoint and communication behaviors inter-relate with Islamic beliefs and values

(Dewitt, 2007; Orbe, 1998). Respectfully exploring Muslim communal space also has helped

create a trusting relationship with the Muslim community that surrounds Somali-Americans.

During my exploration, I have practiced ethical intercultural communication, and fully disclosed

my role as an interested and respectful researcher at all times (Martin, Nakayama, & Flores,

2002).

Another major component of phenomenology and co-cultural theory (Orbe, 1998) is the

reduction and refinement of participant¶s accounts of their lived experiences into essential

structures of meaning or essence (Martinez, 2000; Orbe, 1993). The essence of a person¶s lived

experience, the meaning created and how it is understood by that person in his or her culture, is

discovered by linking co-researcher¶s experiences to a specific understanding or meaning. When

the interview transcripts have been scrutinized for shared meanings until the smallest number of

meanings (usually a phrase or short sentence) are related to the smallest number of shared

experiences, an essence has revealed itself. An essence is important because it describes a

relationship, communication strategy, value, or belief that is uniquely bound to the study¶s

participants (Creswell, 1998; Hecht et al, 2003; Orbe, 1993).

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 15/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 15

The qualitative methods I have used in this project are much different from my

undergraduate experience using quantitative methods (Creswell & Miller, 2000). Primarily, this

has been the case because the qualitative method has required much more attention to my

interactions during data collection. For example, an essential part of Orbe¶s (1998) co-cultural

approach is reflexivit y, or the self-reflexive process (Creswell & Miller, 2000). Being reflexive

means not only reflecting on one¶s perspective and bias while performing data collection, but

also examining one¶s motivations and cognitive processes that lead up to decision-making and

judgments (Orbe, 1998)

I enacted my understanding of reflexivity by regularly and consistently questioning

whether or not I have described communication experiences in the voice of the participants, and

not my own. I made it a regular practice to record my impressions and understandings after every

MSA event; when I had a conversation with another Muslim I had just met; after any social

interaction that was significant in some way; and after most of the interviews. In this way the,

meaning and importance of reflexivity revealed itself step-by-step during the project. The

significance of practicing mindfulness and handling communication apprehension is discussed in

the following section.

Mindfulness and Uncertainty

The personal interactions within the Muslim and Somali-American cultures I have

experienced as a human data collection instrument have involved learning and negotiating

cultural differences and navigating different cultural spaces. This relates to another important

concept for communicating across cultural boundaries: mindfulness. Mindfulnesshas

beendescribed by intercultural communication researchers Ting-Toomey (2005) and Gudykunst

(2005) as demonstrating respect for, and maintaining consistent attention to, another person¶s

culture.

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 16/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 16

During this project, I have endeavored to be mindful at all times by demonstrating

openness and honesty, asking questions about Islam politely, listening attentively, sharing my

knowledge about the value Somali and Islamic culture, and always participating in events

dressed in a suit and tie. Literally, mindfulness has been a component, and a function, of this

human data collector.

I have been especially concerned with building trusting relationships with people who

could be potential recruits for the study and/or people who could introduce me to potential co-

researchers. This has included any Muslims I have interacted with at MSA events, at lectures on

the Qur¶an, and at prayer meetings or other functions at the mosque. In fact, much like the

uncertainty of intercultural communication theorized by Gudykunst (2005), I was continually

anxious about committing an embarrassing or, even worse, offensive f aux pa s during my initial

interactions with Muslims and Somali-Americans. My anxiety was abated substantially by

several weeks of sincere kindness, generosity, friendly curiosity, and openness to diversity

offered by my many Muslim benefactors. The pleasant surprise of open and informal

communication practices in Muslim culture is discussed next.

Experiencing Muslim Informality.One day I was invited into the office of the mosque¶s

white haired and bearded director, who is a M uf t i S heik : Mufti meaning he is a qualified

interpreter of Islamic law, and Sheikh meaning he is a respected elder and speaker (Mufti, 2011;

Sheikh, 2011). ³Come, sit«´, he said, and gestured with his hand toward an empty chair next to

another slightly graying man in a prayer cap, brown leather jacket, and blue jeans. The Mufti

Sheikh, wearing a prayer cap and ankle-length thawb, a long-sleeved cotton robe, laid length-

wise on a small couch across from me and asked ,´So, you have a family´? The other man turned

out to be a construction contractor who had another career back in Egypt as a physical therapist. I

enjoyed a pleasant conversation about my research and various religious issues with these two

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 17/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 17

gentlemen, the Mufti Sheikh dozing intermittently between friendly questions and quotes from

the Qur¶an.

My experiences with the Muslim community - at MSA events, prayer meetings and

Qur¶anic lectures at the mosque ± eventually imbued me with positive expectations about future

interactions with Muslims of all races and ethnic backgrounds, and with Muslims at all levels of

status and authority. On a couple of occasions, I stayed at the mosque after a prayer meeting and

spent several hours relaxing and studying in the comfort of this spiritual place. I was never alone,

because as co-researcher Omar (pseudonym) has stated:

You know, in a mosque, there's always somebody there for all five prayers. There's

always somebody there, something going on during the day. I think in a Christian church,

people aren¶t there. There's a lot of time when the church is empty. I'm not sure about

that. Is that true?

I can only speak from my experience in the context of the Muslims I have interacted with

at George Mason University, Northern Virginia Community College, and the al darHijrah

Islamic Center. If these groups are a normal example, it is quite easy for me to understand why

Muslims are not only outraged, but feel real emotional pain at the way Muslims have been

stereotyped as primitive, violent, and oppressive (Friedlander, 2004; Yee, 2005). After the tragic

attacks of September 11, 2001, I experienced for some time a fear of individuals I thought might

be Muslim. My experiences in Muslim communities have completely alleviated that fear, with

the practical caveat that there will always be a few misguided, destructive people in any

community. The project¶s co-researchers are described by demographics and family history in

the next section.

Co-Researcher Recruitment

Co-researchers for the project have been recruited after receiving approval from George

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 18/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 18

Mason University¶s Human Subjects Review Board. (Appendix A)Multiple recruitment

strategies have been used, including personal introductions through MSA members; the creation

of ³Somali-American Identity Project´ Facebook (Turner, 2011a) and Blogger (Turner, 2011b)

pages to promote the study on the Internet; and multiple links to my professional and educational

contact information I have used ³snowball´ sampling whenever possible, through face ± to - face

interactions and through Internet interactions. I have been inspired to try online interviews by

Dewitt¶s (2008) use of an online format for conducting focus group interviews.

Description of Co-Researcher Demographics( Appendix B)

The project¶s purposeful sample (Frey, Botan, & Kreps, 2000) is composed of four

female and six male 18-26 year old Somali-Americans. One co-researcher is finishing high

school, six are completing one to three years of their bachelor¶s degrees, two are finishing

bachelor¶s degrees, one has completed two years of college and is currently unemployed, and

one is a professional counselor with a master¶s degree. Half of the co-researchers are employed

full or part time or work without salaries for non-profit organizations. When given a choice

between American, African, African-American, Muslim, Somali, and Somali-American

identities (adapted from Shepard, 2008), eight co-researchers chose ³Muslim´ as the identity

most salient to them. One co-researcher chose ³Somali-American´ as most salient, and one chose

³African-American´ first and ³Muslim´ second.

Place of Birth, War Memories, and Family Structure. Three co-researchers were born

and raised in northern Virginia, six were born in Mogadishu, and one was born in London,

England. Five of the immigrant co-researchers are from families who fled the civil war in

Somalia as forced immigrants or refugees. One participant has personal memories of civil war

violence and the resulting family upheaval; one has personal memories of refugee camp life; and

the others have heard civil war and refugee narratives from older siblings and parents.

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 19/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 19

All of the co-researchers have large, extended families. In some cases, they have met

people who are introduced to them as aunts, uncles, and cousins that they have been previously

unknown to them. Three of the co-researchers have divorced parents; two co-researchers have

single mothers who remained unmarried after the father¶s death; and one of the co-researchers

has parents who have remain married while living in separate countries. Four of the ten co-

researchers have married parents who live together.

Family structures have been affected by the Somali diaspora. Four of the co-researchers

have described their extended families¶ complete exodus from Somalia, naming relatives in

Sweden, Norway, and Eastern Europe. Six co-researchers have anywhere from a few relatives to

many relatives still living in Somalia, and twoco-researchers have visited relatives in Somalia the

past five years. The next section opens up the topic of using online social networks for recruiting

co-researchers for research studies.

Recruiting Through Social Networks

In order to promote dialog about Somali-American identity between myself and Somali-

Americans, I created a Facebook page (Turner, 2011a), Blogger website (Turner, 2011b), and

Twitter account (Turner, 2011c) dedicated to attracting young adult Somali-Americans to an

explorative dialog about Somali-American identity This type of promotion is in line with social

networking strategies described by Brogan and Smith (2009) and is being used to recruit

participants for other studies. For example, companies are now offering social networking

services to medical researchers for the purpose of recruiting participants for medical trials (Sfera,

2011).

The blogger page (Turner, 2011b) functions like a web page, with an ³About the Somali-

American Identity Project´ opening page , and several other pages explaining in more detail the

project¶s goals and displaying the project¶s ³Informed Consent Form,´ and other project

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 20/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 20

documents. Every Blogger page (Turner, 2011b) is linked to each other and to other web pages

such as the project¶s Facebook page (Turner, 2011a) and my professional information on a

LinkedIn page. By practicing complete transparency with my educational and professional

information, I basically showed as clearly as possible that I had nothing to hide. In the next

section, trust issues and the use of transparency with online web pages is discussed.

Enhancing Trust Through Online Transparency. Having nothing to hide has been an

important issue ever since an MSA executive member and a co-researcher both stated,

separately, that I needed to be careful around Muslims because ³they might think you¶re a spy.´

(Personal conversations with author, November, 2010 and January, 2011). The project

web pages have coordinated links to Somali-American YouTube videos, the present research

project documents, and previous academic research about Somali-Americans in a professional

display (Turner, 2011b). It has been obvious to any viewers that a respectable amount of

consideration, research, time and energy went into creating the web pages. Together, the factors

of professionalism, transparency, and interesting links created a perception that the project was

serious and respectful toward Somali-American culture.

I interacted with a number of Somali-Americans through the project¶s Facebook page

(Turner, 2011a). Internet capta has contributed significantly to the triangulation (Creswell &

Miller, 2000;; Frey, Botan, & Kreps, 2000) of interview capta provided by co-researchers. In

particular, because female Muslims are often limited in their interactions with males (El-Amin

Naeem, 2009; Evans, 2010), I conjectured that Internet and phone interviews would work best

for this segment of the sample group. Since three female co-researchers outside of Virginia were

recruited and interviewed in exactly this way, it would appear that electronic communication

channels may be a productive strategy for future intercultural interviews.

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 21/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 21

Even though the Blogger website (Turner, 2011b) has not been used so far as a

communal communication site by young Somali-Americans, it has turned out to be a significant

symbol of legitimacy for potential co-researchers who visited the page. I found the power of such

a symbol on the perceptions of a group a generation younger than me intriguing as a persuasive

strategy and baffling from the viewpoint of my age-related culture. The Twitter account (Turner,

2011c) connected me with a few Somali-American teenagers and a Somali-American radio show

host, but did not result in recruiting any co-researchers. The next section discusses the protection

of co-researcher¶s confidentiality and the need for offering compensation to co-researchers.

Protecting Confidentiality and Offering Compensation. For personal interviews,

informed consent was obtained from co-researchers in person by this researcher. Internet co-

researchers read the informed consent agreement on the Blogger page (Turner, 2011b), and I

discussed it in detail with each co-researcher. Online co-researchers then gave their consent

verbally to the researcher and sent a signed, printed copy to the researcher by mail or email

attachment. All co-researchers received a copy of the Informed Consent Form as well as a

detailed information statement fully explaining the research project (Appendix A)co-researchers

were asked if they had any more questions or concerns at the end of each interview.

Confidentiality has been maintained by keeping access to all documents strictly limited to

myself and my adviser. All audiotapes, video recordings, and transcripts have been kept in a

locked facility at all times when not being analyzed by this researcher. All co-researcher names

used in this project report are pseudonyms in accordance with the informed consent agreement.

No co-researchers or potential co-researchers have at any time been misinformed or misled in

any way during this study. At any time during the study, anyone viewing the web page sources

or holding a signed consent form could have contacted my university adviser and/or employer to

check my credentials.

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 22/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 22

After two uncompensated co-researchers completed their interviews, I had no contact

from potential co-researchers for two weeks. Compensation was offered in order to attract

participants to the project within the planned interview schedule. One $25.00 gift card, or a

$25.00 donation to a charitable or non-profit organization of their choice, was offered to co-

researchers who completed a 45-60 minute interview. Compensation was mailed toco-

researchers one to two weeks after they completed the interview, or a $25.00 contribution was

sent to their non-profit of choice. Triangulating sources of data and the bracketing of personal

bias is discussed in the next section.

Triangulation and Bracketing

Other sources of information have contributed to the validity of this study. By using

triangulation (Creswell, 1998; Frey, Botan, & Kreps, 2000), capta from the interviews has been

compared with data from Somali-American Internet discussion forums and blogs, Somali-

American educational videos, previous research on refugee and immigrant populations

(including Muslims), and news stories concerning Somali-Americans. Triangulation serves an

important role in qualitative research by providing similar data from multiple sources, providing

additional validity to the researcher¶s interpretations of capta (Creswell & Miller, 2000).

During data collection and analysis of interview transcripts, I have bracketed or set aside,

my personal opinions and judgments by concentrating on the unique character, perspective, and

experiences of each context and each human being (Dewitt, 2007; Orbe, 1998). In accordance

with Orbe¶s (1998) co-cultural methods, I acknowledge that at the present time I am a fifty-five

year old heterosexual male of White ± European descent, married with two adult children, and

holding spiritual beliefs that correlate well to Zen Buddhism. If pressed for a description of my

culture, I would say that my worldview is informed by a liberal, Southern, and Christian

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 23/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 23

upbringing that has been broadened significantly by my travels and experiences as the child of a

a U.S. military officer.

I found bracketing, also called invoking the epoque¶ (Martinez, 2000), to be a difficult

challenge when it came to reading about Islamic prohibitions on female behavior and hearing

them reified during lectures about the Qur¶an and Muslim identity (El-Amin Naeem, 2009;

Evans, 2010). Particularly, it was difficult to bracket my personal opinion when it came to issues

of personal safety. For example, it is forbidden for Muslim women to be alone with a single man,

because a third person ± S ha ytan(Satan) ± will be present to encourage sinful behavior (Evans,

2010; Author¶s personal conversations with MSA members, 2010).

In fact, MSA members have been lectured that it is prohibited in Islam for a man to walk

a young female Muslim student to her car at night, even if the intent is to insure her safety

(Evans, 2010). Shaking hands with a non-Muslim female at a business meeting has also been

defined as an act prohibited by rules against touching anyone of the opposite gender except your

spouse (Evans, 2010). Despite my incomprehensibility of a few singular occurrences such as

this, on the whole I found the Muslim environment and the participant¶s life stories so

fascinating that I seldom dwelled on my personal viewpoint. As Orbe and Harris (2006) have

made clear, sometimes the best approach in communicating outside your comfort zone is to

accept that you will not understand everything you hear. The next section discusses the format

used for interviewing participants.

Interview Environments. Interviews were conducted in three different environments

during the project. Six face-to-face interviews were conducted at different geographic locations,

including George Mason University, Northern Virginia Community College, and an Indian

restaurant; two interviews were conducted by telephone; and two interviews were conducted

with Skype video calls (one with the video turned off, at the request of the female co-

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 24/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 24

researcher). Different environments were used in order to take advantage of electronic

communications and to demonstrate respect for co-researcher¶s comfort, particularly female

participants.

All interviews were recorded with a digital voice recorder that made MP3 file storage

possible. All voice recordings were transcribed. Interviews lasted from fifty minutes to two and

one- half hours. Most interviews lasted about ninety minutes.

Interview Question Creation

Interview questions (Appendix A) were mainly related to Hecht et al.¶s (2003)

communication theory of identity and Husain (2008) and Shepard¶s (2008) research findings

about cultural barriers experienced by Somali-American adolescents. Interview questions that

were related to the communication theory of identity (Hecht et al., 2003) inquired about personal

and family history; relational and social communication; communication within and outside of

Somali ± American culture, and values and beliefs. Interview questions that were based on

Husain (2008) and Shepard¶s (2008) research included languages and language fluency,

experiences of racial and religious discrimination, 9/11 experiences, and diversity of friendships

and social groups.

Some questions related to identity were adapted from Hackshaw (2007) and asked

whether or not co-researchers perceived a more salient affinity with native African-Americans or

with American Muslims. Questions asking co-researchers to ³switch places´ with native African-

Americans and white European-Americans were created independently by this author. Many co-

researchers who imagined what it was like to be a member of a different cultural group gave

enhanced descriptions about their perceptions and beliefs concerning African-Americans and

white-Europeans. Additionally, some responses about ³being Somali-American´ changed , or

were more descriptive, after this exercise .

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 25/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 25

Interview questions were created to collect capta about young adult Somali American¶s

communication standpoint derived from their lived experiences; accounts of Somali culture;

perceptions about white-European American and African-American culture; accounts of Muslim

culture; and how these experiences influenced their construction and negotiation of identity.

Questions were specific and open ended, meaning that questions elucidated specific experiences

of interpersonal and intercultural communication and provided space for co-researchers to

describe the meaning of their experiences in their own voices.

After each interview, I reviewed notes to evaluate how well questions were providing the

data needed for the project. Ineffective questions were omitted, some questions were changed,

and some were added to provide deeper and more detailed descriptions of experiences. For

example, as a theme of qabiil (tribalism) emerged, I began asking a question about tribalism and

allowing for open discussion about this issue. By the third interview, questions for each

interview remained essentially the same. I transcribed each interview and, as described in the

next section, I followed Orbe¶s (1998) co-cultural method of reducing the transcripts into

themes.

Reducing Transcripts into Themes: Orbe¶s Three Phases

First Review: Description. During the periods between interviews, I made notes about

some specific incidents and experiences from each interview that reflected aspects of identity

construction and negotiation. I became aware of redundancies in the interview questions and of

questions which did not provide the capta the study was attempting to discover. In accordance

with the concept of following emerging themes from the interviews, I omitted redundant and

unproductive questions and clarified others (Dewitt, 2007, Orbe, 1998, Witteborn, 2007). By the

third interview, certain themes had emerged that would remain consistent in later analysis, and

more would emerge from the reduction process.

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 26/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 26

I followed three steps outlined by Orbe (1998) during the descriptive phase of reduction.

First I transcribed all interviews (Appendix C, example of completed transcript), andread each

transcript individually without making notes.

Second, I highlighted words, phrases, and narratives that appear to be essential to the lived

experiences of co-researchers. In the case of the present study, these experiences will be related

to questions about identity construction and negotiation through personal interactions.

In the third step of the description phase, I bracketed themes from the first transcript

before moving on to the next transcript. More or different themes are expected to emerge from

each new transcript, because each co-researcher¶s lived experience will point out their individual

standpoint, including how they view the worlds around them and shape their own reality; how

they perceive others and how they think others perceive them (Dewitt, 2007); and how they

negotiate who they are in the different contexts of their worlds (Orbe, 1998). I read most of the

transcripts a second time in this phase to be certain I was following Orbe¶s (1998) method

correctly.

Second and Third Phases: Reduction and Interpretation. For the second phase of

reduction, I read every transcript again to become more familiar with themes highlighted in each

transcript. Ieliminated themes that were not essential to participant¶s lived experiences, and I

began to consider specific themes that were consistent across all interviews. After completing

this task for each transcript, I advanced into the third phase of theme reduction (Orbe, 1998).

In the third phase of reduction, I started to interpret themes that had been identified, and

discovering how they connected with the viewpoints of different co-researchers. I reviewed

essential themes drawn from interviews and constructed concepts that demonstrated how the

themes related to one another. Reflexivity, how one starts with an initial interpretation and

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 27/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 27

interrogates that interpretation, became more familiar a process as I continued from one

transcript to the next and back again (Dewitt, 2007; Orbe, 1998).

As suggested by Orbe (1998), I used creative thinking to explore how broad concepts

might explicate the themes more logically and thoroughly in the voices of the co-researchers.

Unique phrases began to emerge that described how the themes were interconnected and related

from one co-researcher¶s experience to the other. During this phase, a unique and unexpected

theme I labeled ³Privileging Diversity´ began to emerge.

Orbe (1998) states that once a researcher has completed this process, he should

understand that a complete reduction of the themes is not possible, because the

phenomenological approach assumes that the researcher¶s involvement with the capta is

intersubjective. Orbe states that in the phenomenological method, the researcher¶s worldview is a

continuous and dynamic part of the interpretive process, to the extent that interpretations of capta

are similar to an ongoing dialog between the researcher and the data. In this sense, the reduction

can never be completed because the conversation is never completed.

The conclusion of the phenomenological process provides researchers with an

understanding of a specific group¶s standpoint and voice by thoroughly examining their reports

of day-to-day experiences. Phenomenology (Sokolowski, 2000), which recognizes multiple

perceptions of reality, and Orbe¶s (1998) co-cultural theory, allow researchers to bring a

marginalized group¶s voice and perspective into the dominant cultural discourse. Orbe¶s co-

cultural approach acknowledges the lived experiences of marginalized groups as an acceptable

form of data (Dewitt, 2007), or capta.

Co-researcher Involvement. Four co-researchers volunteered to review and evaluate the

themes and interpretation produced by this study. Two co-researchers, Hanad and Sufia

(pseudonyms) were available for a three-person phone conference with the author on April 28,

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 28/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 28

2011. Hanad and Sufia read the thematic analysis I sent to them by email, and we systematically

discussed each theme in a fifty-minute conversation, verifying the accuracy or inaccuracy of its

language, voice, and viewpoint. As a result of this consultation with my co-researchers, some

changes have been made to the final analysis.

My co-researchers, for example, judged a theme about privileging the father¶s personal

advice over the mother¶s, labeled ³Wisdom of the Father´, to be unrealistic. Another theme had

poignantly described a perceived helplessness and isolation experienced by native African-

Americans. The first example was omitted from the themes because of my co-researcher¶s

invalidation, and the second because a transcript review revealed it did not reach enough

saturation from participant¶s transcripts (Creswell & Miller, 2000). This procedure helped

validate the study¶s findings because it verified the most important dimension of the analysis:

The unique voice and standpoint of my co-researchers. According to Dewitt (2007, pp. 89) this

method ³values the perspective of the Othered, uncovers unknown and useful information, and

has practical application for fostering productive dialogue.´

Results

This section lists and describes four main themes reduced from co-researcher interviews.

The themes were derived from questions and prompts about communication and social behavior

occurring around culture, religion, race, ethnicity, family members, social groups, and beliefs

and values. The questions were based on findings from previous studies by Husain (2008) and

Shepard (2008). They also correlate with concepts proposed by Hecht et al.¶s (2003)

communication theory of identity. The four main themes are ³Maintaining Strong Family

Bonds,´ ³Keep Your Culture,´ ³Keep Your Religion,´ and ,´ Privileging Diversity.´

The main themes are bridging concepts or frameworks that interconnect several sub-

themes. The main themes and sub-themes have been expressed through co-researcher¶s

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 29/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 29

descriptions of communicative experiences and social interactions related to identity

construction. Examples of co-researcher¶s lived experiences, voiced in their words, provide a

glimpse of their construction of reality and their negotiation of identity within that reality

(Dewitt, 2007; Orbe, 1998; Witteborn, 2007). Each main theme is presented in a separate section

with its sub-themes and quotes from co-researchers that demonstrate the themes. All co-

researcher¶s names are pseudonyms.

Theme One: Maintaining Strong Family Bonds

I first named this theme ³Keeping the Family Together´, but after revisiting the

transcripts, ³Maintaining Strong Family Bonds´ appeared to be a better representation.

³Maintaining Strong Family Bonds´ reflects how family members stay connected to each

through difficult and challenging experiences, such as forced and voluntary migration, the

diaspora from Somalia, and internal family conflicts. Hanad, an ambitious eighteen year old male

born in northern Virginia in his last year of high school, had started a non-profit organization two

years before with a high school friend to help children in Somalia. Hanad recounted how his

family of divorced parents, two grandparents, five sisters and four brothers worked together and

stayed together through hard times.

I have eight brothers and sisters. We live together with our parents and grandparents. In

the past we were pretty poor. We were on food stamps and stuff like that. In 2008, we

have three college graduates with jobs in the house. That¶s why we¶re middle class now.

We all contribute everything to the family.

Ali, an intelligent, friendly, and funny twenty-six year old from a family of divorced

parents and six adult siblings, sprinkles his answers with American slang terms like dude and

µbro. Sounding somewhat world-weary, Ali has experienced his baby sister¶s shooting death

while fleeing the civil war and his family¶s decline from upper class privilege to middle class

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 30/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 30

status. Ali admires the strong bonds to his extended family that saved the rest of his immediate

family from perishing after they fled from the civil war in Somalia.

I had an aunt that I never knew [before]. We sent her here [the U.S.] for surgery«and

she just stayed. Whenever we were at a place that had communication, she sent us some

money. So, the older people came first. She got a house in Ohio, and we went to Ohio.

Brave woman. She saved the whole family.

Omar, a proud and assertive twenty year old college sophomore with married parents,

two sisters and four brothers, spent eight years in Egypt with his family before immigrating to

the U.S. in 1998. His older siblings remember running from gunfire with two-week- old Omar in

their mother¶s arms. Like many co-researchers, Omar often described how cultural and religious

values reified by his family¶s internal communications connected with perceived obligations to

his relatives. Here, Omar has recounted an experience that demonstrates the importance his

parents placed on helping family members in need:

My mother's brother got in trouble in Sweden and my father had to go to Sweden and

help him. He was there for a long time helping my uncle, and the company he works for

said he had to come back or they would have to fire him. And my mother and father said,

³You know families are more important than this job.´ So my father lost this good

opportunity in order to help my uncle.´

Family Conflicts and Religious Practices. A consistent sub-theme related to strong

family bonds has been the maintenance of those bonds despite serious conflicts between the

parents and their children. Aasha, a smart, independent 22 year-old female university senior

born in Mogadishu, has married parents, three younger sisters, and one younger brother. Aasha

has recently left her parents¶ house to live on campus so that she can feel more comfortable not

wearing hijab, the head covering most Somali-American and American Muslim women wear as

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 31/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 31

a symbol of religious commitment. Aasha¶s conflict with her parent¶s values extends to a

dialectic relationship with her religion, with Somali culture, and with her concept of self-

expression. Aasha has stated,

I have a hard time with « how strict my parents were. I could only go out at certain

times, and come back at certain time. During the winter break I could've stayed on

campus. I decided instead to go back and live at home [during the break] so my mom« I

just wanted her to feel like I'm still around.

For me, I first rejected [hijab] because I felt for a long time that I can¶t express myself.

My mom and my dad expected me to wear hijab, and long skirts and long shirts and so

on. It was like, a sort of self-expression that doesn¶t make any sense. So I wasn't able to

do any of that.

Walii, a gregarious and energetic twenty-five year old male university senior with a

single mother (his father died over twenty years ago) and four brothers, remembers living in a

refugee camp and how much he liked his ten years in Islamabad, Pakistan before moving to

northern Virginia in 2001.Walii¶s description of one of his family¶s conflicts, and its resolution,

has been typical to this group of co-researchers.

My mother and brothers [and I] stayed together. It was a conflict between what my

brothers wanted and the way my mom sees the world. Parents would think, ³I'm going to

lose my kids in the society. They're not going to practice their faith.´ We had to

constantly tell my mom, ³No I'm not going to do that.´ So after that, it turns out that it's

not that bad after all (laughs).

But if I got married right now, and my brothers moved out, I would be the first one to

move back with my mom. That is a cultural thing. We would never have our parents in

the old folks home or something like that.

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 32/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 32

Parents Talk and Guidance. Many co-researchers talked about having regular, open

communication with their parents about moral values and behaviors that are acceptable or

unacceptable. This was also tempered with open discussions about international events and

politics. Some co-researchers deferred to one parent for guidance with serious problems, while

others commented that both parents were equally approachable for discussions and advice about

serious matters.

Zahra, an optimistic and resilient eighteen year old female college freshman born in

London, England and now in Massachusetts, has seven siblings and married parents who

currently live in separate countries. Her father lives in New York City and her mother (with five

of her younger siblings) lives in Kenya. Despite the geographical separations, Zahra feels close

to her immediate and extended family. She recounts how her father has been the ³talker´, the

parent most likely to encourage conversation, in her family.

In my family, ever since I was a little kid we would sit down and talk about our day with

my father. We¶d tell him something that happened, or try to explain something. We¶re

talking about drugs and alcohol, how it affects people, stuff like that. About drugs, my

father would say ³Well, I don't do that stuff and I'm happy. So you know, you don't have

to do that stuff.´

Civil War and Diaspora.Hanad suggested that Somalia¶s civil war might be a major

theme for Somali-Americans, because ´ ³We just got here in the early µnineties , and we¶re still

new in this country [and not far removed from the war].´ Co-researchers such as Omar and Walii

related the civil war to stress on family bonds, the diaspora from Somalia, refugee experiences,

lowered socio-economic status, and narratives about perseverance. A history of civil war and

diaspora appears to permeate, implicitly and explicitly, many co-researcher¶s current worldview.

Personal memories, family narratives, and cultural memories of Somalia¶s continuing violent

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 33/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 33

struggle are indicated in co-researcher interviews as a cause for despair over personal and

political losses as well as a reason to be proud for persevering through disastrous circumstances.

Ali¶s story is a tragic, and, unfortunately, common war refugee narrative (Tran &Ferullo, 1997;

Godziak, 2002). Because he is the one co-researcher who has recounted his conscious

experiences with personal losses from the civil war, it is appropriate and valuable to give some

extra space for Ali¶s narrative.

Ali:

Yeah, I remember my little sister got shot. We were in one of those dumpster

trucks, you know? We were traveling, and somebody blocked the road and tried to rob us.

And so the driver just took off [through the roadblock]. And they indiscriminately fired

into the back of the truck and my little sister got shot, and she died. What's really weird

about that, man, like, I mean, when you think about something like that. The whole

family was happy that it was her, because she couldn't help« You know she was a baby

and she couldn't help in danger and stuff like that. You know, it's the difference between

what if my father or mother died, or if we« Because we're helping ± we¶re fetching

water and stuff like that. You know it's a hellhole when you have to decide, when you're

thinking like that. At least she was so young, and she was not vital for survival.

Most of my family is here, or in Europe. Iwould say that most of my family, nine-

five percent, are out of there [Somalia].

Like dude,« Having a chauffeur and then having nothing, it's kinda hard to get

used to. My father was a [highly-skilled, well-paid professional] back home. When we

came to the United States, he met someone, and my mom and him got divorced. There¶s

a lot of tension, you know, being in a new country, so he just took off. He couldn't

handle it. My mom was like, ³Get a job!´, and my father was like, ³I'm a professional!´

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 34/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 34

Like, ³ I'm not going to be holding doors for people. ³Everyone hates him, because we

did not have anything and he just kind of disappeared during a really bad time.

Walii fled the civil war with his single mother and three brothers. Walii has recounted his

family¶s experiences in a refugee camp, and the culture shock he felt moving from one culture to

another. Walii stated,

Yes, my mother and brothers stayed together. In the refugee camp, some mothers would

tell the camp officials that their husband was dead-killed in the war-so they could get a

visa to leave faster. Even if the husband was living in the camp, they would say he was

dead, because [the officials] assumed that if he was alive, he was still fighting. So it was

faster if you¶re a single mother.

Going to Pakistan was culture shock at first, because the other kids had never seen black

people for, and thought they were covered with dirt and tried rubbing your hands. But,

they turned out to be very generous.

Theme Two: Keep Your Culture

Co-researchers consistently expressed that holding on to Somali culture was important in

their daily lives. Language use, specifically speaking and reading the Somali language, emerged

as one of the most consistent factors influencing the maintenance of co-researcher¶s culture from

one generation to the next. Sufia, a loquacious, energetic, creative twenty-three year old college

sophomore, has divorced parents living in two countries - her father in New York City, and her

mother in India. Sufia¶s sister lives not far away with their aunt , and she has four brothers in

Kenya, and one brother in Europe. Sufia speaks fluent Hindi with her mother ³every day´, and

fluent Somali with older relatives living nearby and with her ³aunt in Norway.´ Sufia describes

the importance of language to her generation.

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 35/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 35

For those of us who left when they were very young, we don't even remember the culture.

There¶s no memory of the country, so there's an element of holding onto the culture,

because that is all that you have. The language, that¶s the only thing that distinguishes

you from other cultural groups. If you don't speak the language, Somalis will tell you. «

right to your face, ³If you are not speaking the language you are not one of us (laughs)´.

Aasha shares a similar experience with her parents: ³With the language, my parents always

enforce the fact that they like, want [my younger brother] to speak both languages, to

speak Somali and things like that.´

Comments by Hanad and Omar are notable because they appear to reflect aspects of a

collective culture (Hofstede, 1980). Also, I was impressed by the similarity of Hanad and

Omar¶s comments, and the fact that they are spoken by two very different people. Hanad stated,

³I think [everybody working together, helping each other] is much better than going off and

being alone-a much better way to live.´ Omar stated, ³It's better to get along with people than to

be alone. Keeping Somali culture is important to me because we Somalis, the young ones, won¶t

remember important people in our history and our Somali culture.´

Somali-American Communities: Everybody¶s Watching. Only two co-researchers

reported this particular aspect of Somali-American culture, but their descriptions of two

northern Virginia Somali-American communities were consistent and detailed. Also, Omar and

Aasha¶s experiences were remarkably similar to Shepard¶s (2008) findings from Somali-

American youth in Boston. Omar stated,

Yeah, everybody knows everybody. Like, if the neighbors see somebody¶s son do

something bad, they're going to tell them. That's not good for the younger generation,

they don't like that. It gets really annoying (laughs). The older generation, « they stay

outside, walk around. They will look at you for the longest time« you know, trying to

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 36/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 36

figure out if you're Somali or American or something like that. They will just stand there

and look (laughs).

Asha stated,

You always feel like every Somali individual is judging you in a sense, or scrutinizing

you. It leads to something like teens thinking ³Where are the spots I can go to where

there aren¶t any Somali people, so it doesn't affect my mom´?

Qabiil: Intra-Cultural Racism and Politics. There is a hostile, alienating, and

prejudicial aspect to maintaining Somali culture that has been described by many co-

researchers. It is an ethnocentric tribalism, called ³racist´ by Zahra, Sufia, and Omar, and

known as qabiil to Somalis and Somali-Americans. Aasha recounts a typical narrative.

It's like, maybe this lady's son wanted to marry the other family¶s daughter and they're

from different tribes back in Somalia, and those tribes don't marry each other. And they'll

say something like, ³Well our daughters in school ´and« whatever, and they'll keep it

from happening.Tribalism is very much alive. People say it isn't, but it's very much alive.

Ali, mostly cheerful and funny during his interview, turned suddenly grave when the

subject of qabiil was raised. Ali recounted another narrative typical to this group of co-

researchers: That qabiil is responsible for the war that has caused so much damage to Somalia

and its people. When asked about tribalism, Ali stated:

That's a subject I stay away from. I am so anti-tribal. I think it's what took our country

down. It really sucks. The younger people in college right now, they could care less. You

hear the older people talking about, ³We need to build that city back up.´ And I'm like,

³We¶re in America. The whole family is here, who cares?´ A lot of people care about

family ties and bloodlines. I really hate them, man. Look what they did to the country, a

8/6/2019 Exploring How Young Adult Somali-Americans Are Constructing Identity in Post-9/11 America

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/exploring-how-young-adult-somali-americans-are-constructing-identity-in-post-911 37/78

SOMALI-AMERICAN IDENTITY 37

nice country. Like, I went from having a bidet in my house to shitting in the woods and

dodging bullets because some people, greedy people, wanted power.

³Not Black´ and ³Politically Black´. To clearly identify the cultural groups described

in co-researcher¶s language, I have used Sufia¶s definition for a group commonly known as

A frican- Americans: ³African-Americans are people who are from Africa, but they have been

here for a really long time´. I have labeled the group Sufia has described as nat ive African-

Americans. A frican- Americansis a term most often used by co-researchers to describe

morerecent immigrants from the African continent. Bl ack is a termoften used neutrally to mean

³native African-Americans´, but sometimes co-researchershave used Bl ack derogatorily to mean

³gangsta,´ ³ghetto,´ or´ low-class´ native Africa- Americans.