Expedition magazine - Silk Road Issue

-

Upload

penn-museum -

Category

Documents

-

view

241 -

download

5

description

Transcript of Expedition magazine - Silk Road Issue

SILK ROADS IN HISTORY

MUMMIES OF EAST CENTRAL ASIA

TEXTILES FROM THE SILK ROAD

LANGUAGES OF THE TARIM BASIN

®

WINTER 2010VOLUME 52 , NUMBER 3

THE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA

MUSEUM OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY

WWW.PENN.MUSEUM/EXPEDITION

Expedition New Cover Winter 2010.indd 2 12/15/10 12:47 AM

ExpedWinter2010.indd 2 12/7/10 10:12 AM

www.museum.upenn.edu/expedition 1

44

23

We welcome letters to the Editor.Please send them to: ExpeditionPenn Museum 3260 South StreetPhiladelphia, PA 19104-6324 Email: [email protected]

9

23

33

44

2345

7545557

features

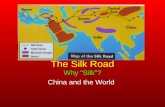

THE SILK ROADS IN HISTORY

By Daniel C. Waugh

THE MUMMIES OF EAST CENTRAL ASIA

By Victor H. Mair

TEXTILES FROM THE SILK ROAD: INTERCULTURAL EXCHANGES AMONG NOMADS, TRADERS, AND AGRICULTURALISTS

By Angela Sheng

BRONZE AGE LANGUAGES OF THE TARIM BASIN

By J.P. Mallory

departments

From the Editor

From the Director

Portrait—Dr. Elfriede R. (Kezia) Knauer

What in the World— Ancient and Modern Foods from the Tarim Basin

Research Notes—The Luohan that Came from Afar

Museum Mosaic—People, Places, Projects

Book News & Reviews—Before the Silk Road

Index for Volume 52

on the cover: Yingpan Man, excavated from Yingpan, Yuli (Lop Nur) County, dates to the 3rd to 4th century CE. His cloth-ing is finely made, and his painted mask is decorated with gold leaf. (Photo credit: Xinjiang Institute of Archaeology Collection)

contentswinter 2010

V O L U M E 5 2 , N U M B E R 3

Expedition® (ISSN 0014-4738) is published three times a year by the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 3260 South St., Philadelphia, PA 19104-6324. ©2010 University of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved. Expedition is a registered trademark of the University of Pennsylvania Museum. All editorial inquiries should be addressed to the Editor at the above address or by email to [email protected]. Subscription price: $35.00 per subscription per year. International subscribers: add $15.00 per subscription per year. Subscription, back issue, and advertising queries to Maureen Goldsmith at [email protected] or (215)898-4050. Subscription forms may be faxed to (215)573-9369. Please allow 6-8 weeks for delivery.

9

33

ExpedWinter2010.indd 1 12/15/10 8:15 AM

2 volume 52 , number 3 expedition

t h e w i l l i a m s d i r e c t o r

Richard Hodges, Ph.D.

w i l l i a m s d i r e c t o r s e m e r i t u s

Robert H. Dyson, Jr., Ph.D.Jeremy A. Sabloff, Ph.D.

d e p u t y d i r e c t o r

C. Brian Rose, Ph.D.

c h i e f o p e r a t i n g o f f i c e r

Melissa P. Smith, CFA

c h i e f o f s t a f f t o t h e w i l l i a m s d i r e c t o r

James R. Mathieu, Ph.D.

d i r e c t o r o f d e v e l o p m e n t

Amanda Mitchell-Boyask

m e l l o n a s s o c i a t e d e p u t y d i r e c t o r

Loa P. Traxler, Ph.D.

m e r l e - s m i t h d i r e c t o r o f c o m m u n i t y e n g a g e m e n t

Jean Byrne

d i r e c t o r o f e x h i b i t i o n s

Kathleen Quinn

d i r e c t o r o f m a r k e t i n g a n d c o m m u n i c a t i o n s

Suzette Sherman

a s s o c i a t e d i r e c t o r f o r a d m i n i s t r a t i o n

Alan Waldt

expedition staff

e d i t o r

Jane Hickman, Ph.D.

a s s o c i a t e e d i t o r

Jennifer Quick

a s s i s t a n t e d i t o r

Emily B. Toner

s u b s c r i p t i o n s m a n a g e r

Maureen Goldsmith

e d i t o r i a l a d v i s o r y b o a r d Fran Barg, Ph.D.Clark L. Erickson, Ph.D.James R. Mathieu, Ph.D.Naomi F. Miller, Ph.D.Janet M. Monge, Ph.D.Theodore G. Schurr, Ph.D.Robert L. Schuyler, Ph.D.

design

Anne Marie KaneImogen Designwww.imogendesign.com

printing

C&B Graphicswww.cnbgraphics.com

Travel the silk road with the Penn Museum in this special

expanded edition of Expedition magazine. This issue was created

to compliment Secrets of the Silk Road, a significant new exhibi-

tion that opens on February 5 and runs through June 5, 2011.

Penn Museum is the only East Coast venue for this remarkable

collection of artifacts from East Central Asia. The Museum also has many excit-

ing programs planned for the duration of the exhibition including lectures, fam-

ily days, special weekend programs, and a major scholarly symposium. Check

the Penn Museum website for further information: www.penn.museum.

What follows is a collection of articles by experts in the field of Central Asian

archaeology, art history, and linguistics. In our first feature article, “The Silk

Roads in History,” Dan Waugh provides an overview of the famous trade routes

that made up the legendary Silk Road, and the traders who traveled these routes.

This is followed by Victor Mair’s fascinating look at some of the most note-

worthy mummies discovered in the Tarim Basin, including those you will see

in Secrets of the Silk Road. We then move to an article by Angela Sheng on the

well-preserved textiles in the exhibition; Angela’s analysis reveals the cultural

exchanges that took place among various groups that lived in this region. Our

fourth article, by J.P. Mallory, discusses the linguistic complexity of the Tarim

Basin; where did the people who lived there come from, and what languages

might they have spoken?

Several short articles round out this issue. E.N. Anderson writes on the

preserved foods in the exhibition, and Nancy Steinhardt recounts the mystery

behind a Luohan statue in the Museum’s Asian collection. Mandy Chan reviews

a book on the prehistory of the Silk Road, the period before the establishment of

the famed trade routes. We also include a portrait of Dr. Elfriede Knauer, who

passed away this past summer. Kezia, as she was known to her friends, traveled

the Silk Road for over 30 years, becoming an authority on this part of the world.

This special Silk Road issue of Expedition would not have been possible with-

out the assistance of Victor Mair—professor at Penn, curatorial consultant to

the exhibition, and a scholar whose on-going interest in the burials of the Tarim

Basin made Secrets of the Silk Road possible. Victor gave generously of his time

in the initial planning and on-going production of this issue.

jane hickman, ph.d.Editor

welcome

From the Editor

Secrets of the Silk Road was organized by the Bowers Museum, Santa Ana, California in association with the Archaeological Institute of Xinjiang and the Ürümqi Museum.

ExpedWinter2010.indd 2 12/7/10 12:35 PM

www.penn.museum/expedition 3

Looking back over the last

half-century as archaeology

has become more scientific,

there have been paradoxically

few truly great discoveries.

The wonders of archaeology, so it seems,

were found by Schliemann at Mycenae

and Troy, by Carter with his discovery of Tutankhamun, by

Bingham when he ventured high into the Andes to Machu

Picchu, and by Maudsley, who effectively tamed the jungle to

uncover the Maya. Their stories are told in sepia tone pho-

tographs, many of which have become iconic. Yet two great

archaeological discoveries dominate the archaeology of our

generation: a greater understanding of human evolution from

its roots in Africa, and the incomparable wealth of the cem-

eteries from the Tarim Basin in the Uyghur territory of north-

west China. The intellectual fascination of the findings in sub-

Saharan Africa and their global significance cannot be denied.

But for sheer emotional impact, no recent discoveries match

those from northwest China.

The East Central Asian mummies and associated grave

goods are remarkable for their preservation and beauty.

More than this, though, the Tarim Basin discoveries bring

to light evidence of long-term connections between cultures

that shaped both the East (as far as Japan) and the West (as

far as the Mediterranean). The revelatory finds detail untold

tales of intrepid mobility through trading and herding that we

would normally associate with modern times. Yet plainly such

mobility had its roots in the earliest nomadic and sedentary

groups. Much is made of the ethnic and linguistic issues asso-

ciated with these discoveries, but the really unexpected finds

have been the wealth of clothing and other items of material

culture recovered from the Tarim Basin graves. The exhibition

Secrets of the Silk Road, then—of the great discoveries made

by archaeologists along this ancient tract—will cause us to

rethink many of our accepted ways of understanding the roots

of our civilizations. It will turn long-held beliefs upside down,

and compel us to see interconnections and mobility as axi-

omatic to a past that greatly helped to shape both the Greco-

Roman and Chinese worlds, as well as Gandharan India. We

are at the beginning of a new world history, which may explain

the incredible fascination with this amazing exhibition.

richard hodges, ph.d.The Williams Director

Extraordinary Discoveries along the Silk Road

Vic

tor

H. M

air

by richard

hodges

from the director

The Tarim Basin in East Central Asia was home to numerous cemeteries which contained naturally mummified human remains, colorful textiles, food, and other grave goods. The Xiaohe cemetery shown here is marked by tall wooden posts.

ExpedWinter2010.indd 3 12/15/10 7:41 AM

4 volume 52 , number 3 expedition

portrait

Dr. Elfriede R. (Kezia) Knauer

Penn museum has lost

a highly regarded author-

ity on the Silk Road

just months before the

appearance of this spe-

cial issue of Expedition. Dr. Elfriede

Knauer died after a long illness, shortly

after agreeing to contribute to this issue. Kezia, as she was

known to her family, friends, and colleagues, led an excep-

tional life. Born in Germany, she learned French, English, and

Latin at an early age; her formal study of Classical Archaeology,

Ancient History, the History of Art, and East Asian Studies

eventually led to a Ph.D. from the Johann Wolfgang Goethe

Universität, Frankfurt am Main, in 1951. That same year, she

married Georg Nicolaus Knauer, now Professor Emeritus

in the Department of Classical Studies at the University of

Pennsylvania. By her own account, her areas of specialization

were Greek vase painting, the survival of classical themes in

Renaissance art, the history of cartography, and classical influ-

ences on Central and East Asian art.

The Knauers came to the University of Pennsylvania in early

1975. In 1983, Kezia was appointed Research Associate in the

Mediterranean Section at the Penn Museum, and from 1986

onward, served as a Consulting Scholar. She had the distinc-

tion of being elected a member of the American Philosophical

Society in 1999, and additionally belonged to the Archäologische

Gesellschaft zu Berlin. In 2002, she received the Director’s

Award for distinguished service to the Penn Museum.

Knauer’s command of many subjects is reflected in her pub-

lished work including Coats, Queens, and Cormorants (Zürich

2009), a compendium of articles dealing with the historical, cul-

tural, and artistic interconnections between East and West. Her

earlier book, The Camel’s Load in Life and Death (Zürich 1998),

specifically dealt with trade along the Silk Road, much of which

was based on her firsthand observations; this book received

the prestigious Prix Stanislas Julien in 1999 as the best book

in Sinology. Yet for this writer and others who for the past 30

years attended the same lectures and meetings as the Knauers,

perhaps the greatest proof of the breadth of her knowledge

came in the form of

her questions and

comments to the

speakers which reli-

ably followed every

talk. No matter the topic at hand, her questions were invariably

models of perception and verbal lucidity, always delivered with

disarming kindness and modesty to the very heart of the subject

and leaving everyone better informed for having heard them.

Her knowledge of the Silk Road grew out of a series of jour-

neys undertaken by the Knauers beginning in the early 1980s

and continuing until a short time before her death. Indefatigable

and adventurous travelers, they visited nearly every European

country as part of Georg Knauer’s library-based research into

Latin translations of the Homeric epics, interspersed with

excursions to Syria, Israel, Egypt, Tunisia, and the various

Classical regions abutting the northern Mediterranean.

The capstone to four decades of travel included trips to

China, Tibet, South Korea, Japan, the Philippines, Indonesia,

Sri Lanka, Cambodia, India, and Pakistan, as well as to the

Crimea, Ukraine, Armenia, and Georgia. This enabled Dr.

Knauer to examine the Silk Route from the east and the west, a

study which ended up as an all-embracing passion. The fruits of

this took the form of books, articles, and a host of memorable

public lectures, all of which established her as a leading expert

in subjects too often avoided by specialists as linguistically, his-

torically, and even physically too challenging to undertake.

For many of her friends, Kezia Knauer was part of a remark-

able wave of European scholars who revolutionized the study

of the classics, archaeology, and art history in this country

during the 1930s, 40s, and 50s. Her reputation is destined to

remain intact for years to come. One can only wish that she

had been granted the time to write her recollections of travels

along the Silk Road for this special issue. The Museum and all

its friends shall miss her greatly.

donald white is Professor Emeritus of Classical Studies at the University of Pennsylvania and Curator Emeritus of the Mediterranean Section at the Penn Museum.

3 July 1926–

7 June 2010

by donald white

Elfriede R. (Kezia) Knauer, photographed by her husband in the early 1980s, just as their trips along the Silk Road began.

Geo

rg N

. Kna

uer

ExpedWinter2010.indd 4 12/13/10 3:43 PM

Walking through the exhibition Secrets of the

Silk Road, one is amazed

at the well-preserved

mummies and colorful

textiles. But perhaps the objects that we can

identify with most are the food items that may

have been meant to nourish the dead in the afterlife. Is that a

spring roll? A wonton? Yes, and they are remarkably similar to

what one would purchase in China today.

The extremely dry climate in the Tarim Basin preserved this

food. Few areas of the world can support populations in such

an arid environment, so finds of actual food products—exca-

vated more commonly in places like Egypt—are rare. Scholars

that study ancient food must generally rely on mentions in

ancient texts, animal bones or seeds, or, at best, food that was

thrown into a bog where the airless, acidic environment pre-

serves organic remains.

Secrets of the Silk Road includes six small food items, all

based on wheat. A fried twist of short spaghetti-like dough

strands is dated to the 5th to 3rd century BCE. Such food can

be found in northwest China today. One might assume that

other noodle dishes, particularly soups, were regular fare dur-

ing antiquity, as they have been for a long time in the area.

From the Tang Dynasty (7th to 9th century CE), we have part

of a spring roll and wonton, both virtually identical to modern

versions of the same food. Although we do not know exactly

what is in each one, both were stuffed with a filling. A similar

type of wonton, called a chuchure, is known as a traditional

food in present-day East Central Asia.

From both early and late periods, we have strikingly lovely

modeled flowers: a chrysanthemum, a plum blossom, and a

seven-petaled flower. These flowers were probably more orna-

mental than edible, since they were likely made from a stiff

dough of wheat and water, and baked into rocky hardness. They

may have served as religious offerings, since similar ornamental

offering-pastries are produced in China today. Tang earthen-

ware figurines also offer insight into food preparation in ancient

East Central Asia. Women are depicted performing chores such

as churning, baking or steaming, and rolling out dough.

From earliest times until today, food in many areas of

Central Asia was based on a classic Middle Eastern crop roster:

wheat, barley, and sheep products, with cattle, horses, goats,

camels, and other livestock playing important roles. Wheat

was a staple, and barley was also heavily used. Barley does not Xin

jiang

Uyg

hur

Aut

onom

ous

Reg

ion

Mus

eum

Col

lect

ion

what in the world

by e. n.

anderson

Geo

rg N

. Kna

uer

This twisted fried dough, over 2,000 years old, was found in a tomb on a red lacquer table. It was made from flour and twisted by hand.

Ancient and Modern Foods from the Tarim Basin

Left, the dough in this spring roll was rolled out, wrapped around a filling, then fried. Right, a wonton is made of rolled dough that is wrapped around a filling and boiled. Wontons are often found in soups.

www.penn.museum/expedition 5

ExpedWinter2010.indd 5 12/13/10 3:43 PM

6 volume 52 , number 3 expedition

Xin

jiang

Uyg

hur

Aut

onom

ous

Reg

ion

Mus

eum

Col

lect

ion

bake well, but it does produce a good crop under conditions

so dry or salty that nothing else will grow. Dairy products were

probably far more important than meat, as in other traditional

Central Asian societies. Grapes and other fruits are well known

from historic sources.

Two species of millets also came from China and were used

for porridge. In Central Asia, however, they were always a

minor crop, since they do not produce good baking material

for bread, a staple that linked the region to the Western world.

Rice, now a staple in the Tarim Basin, is not attested from early

times. Judging by what is preserved, the diet in this region likely

resembled that found in the most remote parts of Afghanistan

and Pakistan up until a few decades ago: bread, a little yogurt,

fruit, and some herbs to accompany the meal. On a rare festive

occasion, meat, cheese, and butter might have also been eaten.

Wine and beer were probably available. The rivers afforded

some fish, known as laks or lakse in the Tocharian languages.

Dumplings of all kinds remain important in this area. They

are usually called by some variant of the word mantu, but they

are ashak in Afghanistan and momo in Tibet. Dumplings are

of uncertain origin and span across Eurasia from quite an early

period. The small dumpling would have been called mantou

(or mantu) in China during this time, while today its name

is jiaozi.

A Persian-style flat bread—often sprinkled with sesame

seeds and baked by sticking it to an oven wall—was probably

the staple food in Central Asia. Its modern Farsi name, nan,

is derived from the familiar pan. This bread reached China by

the Tang Dynasty, brought by Iranian refugees and traders. Its

descendents survive today as the shaobing, which is tradition-

ally baked on a heated pot wall, and the huge sesame breads of

northwest China, which are now steamed rather than baked.

No one seems to know when the huge tandur-style oven was

developed, but it is certainly very old in the region.

With further discoveries of intact burials in the Tarim

Basin, we will likely find more preserved food. Perhaps we will

develop a greater understanding of how food traditions trav-

eled along the many routes that made up the Silk Road.

e. n. anderson is a Professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of California, Riverside.

For Further Reading

Anderson, E. N. The Food of China. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988.

Chang, K. C., ed. Food in Chinese Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977.

Robinson, Cyril D. “The Bagel and Its Origins—Mythical, Hypothetical and Undiscovered.” Petits Propos Culinaires 58 (1998):42-46.

Schafer, Edward H. “T’ang.” In Food in Chinese Culture, edited by K. C. Chang, pp. 85-140. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977.

Trombert, Eric. “Between Harvesting and Cooking: Grain Processing in Dunhuang, a Qualitative and Quantitative Survey.” In Regionalism and Globalism in Chinese Culinary Culture, edited by David Holm, pp. 147-179. Taiwan: Foundation of Chinese Dietary Culture, 2010.

This flour dough dessert, in the shape of a plum blossom, originally contained fruit in its center. Some flowers like this may have been ornamental and not meant to be eaten.

Painted ceramic figurines depict female servants in various stages of food preparation.

ExpedWinter2010.indd 6 12/7/10 10:32 AM

Among the myriad objects

of world art, there are always

some that continue to cap-

tivate the viewer and haunt

the researcher. The tri-color

glazed clay Luohan statue from Yi County

(Yizhou), about 50 km southwest of the

city limits of Beijing, is such an object in the Penn Museum.

The mysteries that engulf this Luohan—a portrayal of a monk

who was a disciple of the Buddha Sakyamuni—begin with a

Chinese inscription reported to have been written in a cave in

which the statue may have been hidden. In translation, it reads

“All the Buddhas come from afar.”

The story of the cave with this enigmatic inscription is

recounted by German expeditionary Friedrich Perzynski in an

essay from 1920. In 1912, Perzynski had been shown a simi-

lar Luohan statue by two Beijing art dealers. He then traveled

to Yi County in search of the cave where a group of Luohan

sculptures, according to the dealers, had previously been hid-

den. When he entered the cave, Perzynski found the inscrip-

tion and concluded from this text that the statues had origi-

nally come from elsewhere and had later been deposited in the

cave, perhaps for safekeeping.

The Penn statue left China in 1913 through an arrangement

made by German art dealer Edgar Worch. In June of 1914, the

Museum purchased the statue from Worch. Perzynski mean-

while brought two other Luohan statues with him to Germany

in November of 1913. One was bought by the German collec-

tor Harry Fuld and given to the Museum für Asiatische Kunst

in Berlin, where it is believed to have been lost in the bomb-

ings of 1945. The other was purchased by the Metropolitan

Museum of Art in New York. Between 1914 and 1921, five

similar Luohan statues were bought or acquired by museums,

including the Metropolitan, the British Museum, the Royal

Ontario Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and

the Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum in Kansas City. Two more

Luohan statues are believed to be part of this group. One was

sold into a private collection in Japan as early as 1921, and the

other is possibly in the Musée Guimet.

Although the group of statues are similar in size,

glaze, and form, the individual quality of each Luohan

Pen

n M

useu

m

Xin

jiang

Uyg

hur

Aut

onom

ous

Reg

ion

Mus

eum

Col

lect

ion

research notes

by nancy

shatzman

steinhardt

The Luohan that Came from Afar

www.penn.museum/expedition 7

This Luohan from China is 1.21 m in height. It can be viewed in the Chinese Rotunda in the Penn Museum. UPM #C66A,B.

ExpedWinter2010.indd 7 12/7/10 10:32 AM

8 volume 52 , number 3 expedition

Pen

n M

useu

m

challenges a viewer to connect with the person behind

the face. The depth of portraiture seen here is almost

unparalleled in Chinese art. This kind of portraiture is

possible because a Luohan was considered mortal. Chinese for

the Sanskrit word arhat, Luohan can be translated as “enlight-

ened man” or as the adjective “venerable.” Yet there is no

promise that an Arhat will attain the otherworldly status of

Buddhahood.

It is unknown if the Yizhou Luohan were portraits of spe-

cific individuals, although a goal of each sculpture clearly is

an individual, human portrayal. It is also unclear how many

statues were in the original group associated with the Yizhou

cave, and when and where they were originally made. Legends

from Buddhist literature tell of Luohan that appear in groups

of 16, 18, and 500. Today, the Luohan statues that survive in

their original temple settings, particularly in Japan, are often

found in groups of these numbers. At least 8, and probably

10, of the tri-color glazed Luohan statues left China during a

ten-year period, so the group might have originally numbered

16 or 18. The date of manufacture also is not certain. Although

the statues were sold as objects from the Liao Dynasty (ca.

947–1125), chemical tests on the Penn Museum statue yielded

a date as late as the 12th century, meaning that it could have

been made during the non-Chinese dynasty Jin (1115–1234)

that succeeded Liao in northern China.

Two other extraordinary Liao objects are on display in the

Rotunda. One is a silver death mask, beaten to a thickness of

no more than one cm. Not an individualized portrayal, the

burial mask is instead evidence of a Liao funerary practice

believed to have originated with North Asian nomads of the

1st millennium BCE. Another Liao object is the gilt bronze

statue of the bodhisattva Guanyin, acquired by the Penn

Museum in 1922. The bodhisattva is an enlightened being

en route to Buddhahood who aids others in the attainment

of their own Buddhist salvation. Guanyin is known for lov-

ing kindness and compassion, and is identified by the seated

Buddha in its crown.

The three pieces attest to the

strength and boldness of Liao sculp-

ture. The Luohan, however, super-

sedes the other two in its superla-

tive, descriptive face, a visage that

engages anyone who sees it, even

though its provenance remains a

mystery to this day.

nancy shatzman stein-hardt is Professor of East Asian Art, Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, University of Pennsylvania, and Curator in the Asian Section at the Penn Museum.

Associated with the Liao Dynasty (947–1125 CE), this death mask (H. 21 cm) was made by beating a heavy sheet of silver. UPM #44-16-1A,B.

The gilt bronze statue of Guanyin holds a lotus bud in its left hand. It measures 71 cm in height. UPM #C400.

ExpedWinter2010.indd 8 12/7/10 10:32 AM

www.penn.museum/expedition 9

Pen

n M

useu

m

Col

lect

ion

of t

he S

tate

Her

mita

ge M

useu

m, S

t. P

eter

sbur

g

The Silk Roads in History by daniel c . waugh

There is an endless popular fascination with

the “Silk Roads,” the historic routes of eco-

nomic and cultural exchange across Eurasia.

The phrase in our own time has been used as

a metaphor for Central Asian oil pipelines, and

it is common advertising copy for the romantic exoticism of

expensive adventure travel. One would think that, in the cen-

tury and a third since the German geographer Ferdinand von

Richthofen coined the term to describe what for him was a

quite specific route of east-west trade some 2,000 years ago,

there might be some consensus as to what and when the Silk

Roads were. Yet, as the Penn Museum exhibition of Silk Road

artifacts demonstrates, we are still learning about that history,

and many aspects of it are subject to vigorous scholarly debate.

Most today would agree that Richthofen’s original concept

was too limited in that he was concerned first of all about the

movement of silk overland from east to west

between the “great civilizations” of Han China

and Rome. Should we extend his concept to

encompass striking evidence from the Eurasian

Bronze and Early Iron Ages, and trace it beyond

the European Age of Discovery (15th to 17th

centuries) to the eve of the modern world? Is

there in fact a definable starting point or conclu-

sion? And can we confine our examination to

exchange across Eurasia along a few land routes,

given their interconnection with maritime trade?

Indeed, the routes of exchange and products were

many, and the mix changed substantially over

time. The history of the Silk Roads is a narrative

about movement, resettlement, and interactions

across ill-defined borders but not necessarily

over long distances. It is also the story of artistic

exchange and the spread and mixing of religions,

all set against the background of the rise and fall

of polities which encompassed a wide range of

cultures and peoples, about whose identities we still know too

little. Many of the exchanges documented by archaeological

research were surely the result of contact between various

ethnic or linguistic groups over time. The reader should keep

these qualifications in mind in reviewing the highlights from

the history which follows.

The Beginnings

Among the most exciting archaeological discoveries of the

20th century were the frozen tombs of the nomadic pastoral-

ists who occupied the Altai mountain region around Pazyryk

in southern Siberia in the middle of the 1st millennium BCE.

These horsemen have been identified with the Scythians who

dominated the steppes from Eastern Europe to Mongolia. The

This detail of a pile carpet, recovered from Pazyryk Barrow 5 and dated 252–238 BCE, depicts an Achaemenid-style horseman.

ExpedWinter2010.indd 9 12/7/10 10:32 AM

Dan

iel C

. Wau

gh (b

oth

page

s)

Pazyryk tombs clearly document connections with China: the

deceased were buried with Chinese silk and bronze mirrors.

The graves contain felts and woven wool textiles, but curi-

ously little evidence that would point to local textile produc-

tion. The earliest known pile carpet, found in a Pazyryk tomb,

has Achaemenid (ancient Persian) motifs; the dyes and tech-

nology of dyeing wool fabrics seem to be of Middle Eastern

origin. Other aspects of the burial goods suggest a connection

with a yet somewhat vague northeast Asian cultural complex,

extending along the forest-steppe boundaries all the way to

Manchuria and north Korea. Discoveries from 1st millennium

BCE sites in Xinjiang reinforce the evidence about active long-

distance contacts well before Chinese political power extended

that far west.

While it is difficult to locate the Pazyryk pastoralists within

any larger polity that might have controlled the center of

Eurasia, the Xiongnu—the Huns—who emerged around the

beginning of the 2nd century BCE, established what most con-

sider to be the first of the great Inner Asian empires and in

the process stimulated what, in the conventional telling, was

the beginnings of the Silk Roads. Evidence about the Xiongnu

supports a growing consensus that Inner Asian peoples for-

merly thought of as purely nomadic in fact were mixed soci-

eties, incorporating sedentary elements such as permanent

settlement sites and agriculture into their way of life. Related

to this fact was a substantial and regular interaction along the

permeable boundaries between the northern steppe world

and agricultural China. Substantial quantities of Chinese

goods now made their way into Inner Asia and beyond to the

Mediterranean world. This flow of goods included tribute the

Han Dynasty paid to the nomad rulers, and trade, in return

for which the Chinese received horses and camels. Chinese

missions to the “Western Regions” also resulted in the open-

ing of direct trade with Central Asia and parts of the Middle

East, although we have no evidence that Han merchants ever

reached the Mediterranean or that Roman merchants reached

China. The cities of the Parthian Empire, which controlled

routes leading to the Mediterranean, and the emergence of

prosperous caravan emporia such as Palmyra in the eastern

Syrian desert attest to the importance of interconnected over-

land and maritime trade, whose products included not only

silk but also spices, iron, olive oil, and much more.

The Han Dynasty expanded Chinese dominion for the first

time well into Central Asia, in the process extending the Great

Wall and establishing the garrisons to man it. While one result

of this was a shift in the balance of power between the Xiongnu

10 volume 52 , number 3 expedition

Xiongnu tombs contained various types of grave goods. Objects in this late 1st century BCE to middle 1st century CE burial from Mongolia included a bronze cauldron containing the remains of a ritual meal, pottery, and a Han Dynasty lacquer bowl with metal rim.

ExpedWinter2010.indd 10 12/7/10 10:33 AM

Dan

iel C

. Wau

gh (b

oth

page

s)

www.penn.museum/expedition 11

The Qizilqagha beacon tower, northwest of Kucha, Xinjiang, dates from the Han Dynasty. It is located near an important Buddhist cave temple complex and stands approximately 15 m tall.

ExpedWinter2010.indd 11 12/7/10 10:33 AM

Dan

iel C

. Wau

gh, E

mily

Ton

er (m

ap)

12 volume 52 , number 3 expedition

and the Chinese in favor of the latter, Xiongnu tombs of the late

1st century BCE through the 1st century CE in north-central

Mongolia contain abundant Chinese lacquerware, lacquered

Chinese chariots, high-quality bronze mirrors, and stunning

silk brocades.There is good reason to assume that much of the

silk passing through Xiongnu hands was traded farther to the

west. Although Richthofen felt that the Silk Road trade ceased

to be important with the decline of the Han Dynasty in the 2nd

century CE, there is ample evidence of very important interac-

tions across Eurasia in the subsequent period when—both in

China and the West—the great sedentary empires fragmented.

The Silk Roads and Religion

During the 2nd century CE, Buddhism began to spread vigor-

ously into Central Asia and China with the active support of

local rulers. The earliest clearly documented Chinese transla-

Right, the 19 m high Tang period statue of Maitreya, the Buddha of the Future, is located at Xumishan Grottoes, Ningxia Hui Antonomous Region, China. The cave temples here were first carved in the Northern Wei peri-od. Below, this map charts major routes and sites of the Silk Road.

ExpedWinter2010.indd 12 12/13/10 3:44 PM

Dan

iel C

. Wau

gh, E

mily

Ton

er (m

ap)

www.penn.museum/expedition 13

Maijishan or “Wheatstack Mountain,” in eastern Gansu Province, is a Buddhist cave site first established under the Northern Wei Dynasty in the 5th century.

Dan

iel C

. Wau

gh

tions of Buddhist scriptures date from this period, although

the process of expanding the Buddhist canon in China and

adapting it to Chinese religious traditions extended over sub-

sequent centuries. Understandably, many of the key figures in

the transmission of the faith were those from Central Asia who

commanded a range of linguistic skills acquired in the multi-

ethnic oasis towns such as Kucha. Buddhism also made its way

east via the coastal routes. By the time of the Northern Wei

Dynasty in the 5th and early 6th centuries, there were major

Buddhist cave temple sites in the Chinese north and extending

across to the fringes of the Central Asian deserts. Perhaps the

best known and best preserved of these is the Mogao Caves

at the commercial and garrison town of Dunhuang, where

there is a continuous record of Buddhist art from the early

5th century down to the time of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty

in the 14th century. One of the most famous travelers on the

Silk Roads was the Chinese monk Xuanzang, whose route to

the sources of Buddhist wisdom in India took him along the

northern fringes of the Tarim Basin, through the mountains,

and then south through today’s Uzbekistan and Afghanistan.

When he returned to China after some 15 years, stopping at

Dunhuang along the way, he brought back a trove of scrip-

tures and important images.

Many of the sites that we connect with this spread of

Buddhism are also those where there is evidence of the

Sogdians: Iranian speakers who were the first great merchant

diaspora of the Silk Roads. From their homeland in Samarkand

and the Zerafshan River Valley (today’s Uzbekistan and

ExpedWinter2010.indd 13 12/7/10 10:33 AM

Dan

iel C

. Wau

gh

14 volume 52 , number 3 expedition

Tajikistan), the Sogdians extended their reach west to the

Black Sea, south through the mountains of Kashmir, and to

the ports of southeast Asia. Early 4th century Sogdian letters,

found just west of Dunhuang, document a Sogdian network

extending from Samarkand through Dunhuang, and along the

Gansu Corridor into central China. Sogdians entered Chinese

service and adopted some aspects of Chinese culture while

retaining, it seems, their indigenous religious traditions (a

form of Zoroastrianism). Their importance went well beyond

commerce, as they served not only the Chinese but also some

of the newly emerging regimes from the northern steppes,

the Turks and the Uyghurs. The Turks for a time extended

their control across much of Inner Asia and were influential

in promoting trade into Eastern Europe and the Byzantine

Empire. The Uyghurs received huge quantities of Chinese silk

in exchange for horses. Sogdians played a role in the transmis-

sion of Manichaeism—another of the major Middle Eastern

religions—to the Uyghurs in the 8th century, by which time

both Islam and Eastern Christianity had also made their way

to China. With the final conquest of the Sogdian homeland

by Arab armies in the early 8th century, Sogdian influence

declined. Muslim merchants of various ethnicities would

replace the Sogdians in key roles controlling Silk Road trade.

Tombs of the 5th to 8th century, along the northern routes

connecting China and Central Asia, contain abundant evi-

dence of east-west interaction. There are numerous coins

from Sasanian Iran, examples of Middle Eastern and Central

Asian metalwork, glass from the eastern Mediterranean, and

much more. By the time of the Tang Dynasty (618–906),

which managed once again to extend Chinese control into

Central Asia, foreign culture was all the rage among the

Chinese elite: everything from makeup and hair styles to

dance and music. Even women played polo, a game imported

from Persia.

The Impact of the Arabs and the Mongols

By the second half of the 8th century—with the consolida-

tion of Arab control in Central Asia and the establishment of

the Abbassid Caliphate, with its capital at Baghdad—western

Asia entered a new period of prosperity. Many threads made

up the complex fabric of what we tend to designate simply as

“Islamic civilization.” Earlier Persian traditions continued,

and the expertise of Eastern Christians contributed to the

This view of the southern portion of the Mogao oasis, Dunhuang, includes a temple façade (on the right) that was restored in 1936. The façade covers a 30 m high statue of Maitreya commissioned at the end of the 7th century by the female usurper of the Tang throne, Wu Zetian. Fences added in recent years to reduce wind erosion are visible on the plateau above the cliff.

ExpedWinter2010.indd 14 12/7/10 10:34 AM

Dan

iel C

. Wau

gh

www.penn.museum/expedition 15

400 BCE 200 BCE 0 200 CE 400 CE 600 CE 800 CE 1000 CE 1200 CE 1400 CE 1600 CE

Mediterranean

Persia

Northen IndiaPakistanAfghanistan

Central Asia

East Asia

Macedonians

Roman Empire

Byzantine Empire

Seleucids Sassanians

Parthians Islamic Dynasties

Mauryans

KushansGuptas

Sogdians

Mughals

Sakas UyghursHephthalites Timurids

Xiongnu Juan-juan Khitans Mongols

Han Dynasty Sui Song Dynasty Ming

Hu Peoples Northern Wei Tang Dynasty Tanguts (Xi Xia)

136–125, 119–115 BCE. Zhang Qian, emissary sent by Han

Dynasty Emperor Wu Di to the “Western Regions,” who sup-

plied important commercial and political intelligence.

629–645 CE. Xuanzang (Hsuan-tsang), Chinese Buddhist

monk who traveled through Inner Asia to India, studied there,

and once back in the Chinese capital Chang’an (Xian) was an

important translator of Buddhist texts.

821. Tamim ibn Bahr, Arab emissary, who visited the impres-

sive capital city of the Uyghurs in the Orkhon River valley in

Mongolia.

1253–1255. William of Rubruck (Ruysbroeck), Franciscan

missionary who traveled all the way to the Mongol Empire

capital of Karakorum and wrote a remarkably detailed account

about what he saw.

1271–1295. Marco Polo, Venetian who accompanied his

father and uncle back to China and the court of Yuan Emperor

Kublai Khan. Marco entered his service; after returning to

Europe dictated a romanticized version of his travels while in

a Genoese prison. Despite its many inaccuracies, his account

is the best known and arguably most influential of the early

European narratives about Asia.

1325–1354. Abu Abd Allah Muhammad Ibn Battuta,

Moroccan whose travels even eclipsed Marco Polo’s in their

extent, as he roamed far and wide between West Africa and

China, and once home dictated an often remarkably detailed

description of what he saw.

1403–1406. Ruy Gonzales de Clavijo, Spanish ambassador to

Timur (Tamerlane), who carefully described his route through

northern Iran and the flourishing capital city of Samarkand.

1413–1415, 1421–1422, 1431–1433. Ma Huan, Muslim

interpreter who accompanied the famous Ming admiral Zheng

He (Cheng Ho) on his fourth, sixth, and seventh expeditions

to the Indian Ocean and described the geography and com-

mercial emporia along the way.

1664–1667, 1671–1677. John Chardin, a French Hugenot

jeweler who spent significant time in the Caucasus, Persia,

and India and wrote one of the major European accounts of

Safavid Persia.

Chronology of Selected Travelers

silk road timeline

Tim

elin

e: A

nne

Mar

ie K

ane,

aft

er D

anie

l C. W

augh

ExpedWinter2010.indd 15 12/15/10 7:44 AM

emergence of Baghdad as a major intellectual center. Even

though Chinese silk continued to be imported, centers of

silk production were established in Central Asia and north-

ern Iran. Considerable evidence has been found regarding

importation of Chinese ceramics into the Persian Gulf in the

8th through the 10th century. The importance of maritime

trade for the transmission of Chinese goods would continue

to grow as Muslim merchants established themselves in the

ports of southeast China. The Chinese connection had a

substantial impact on artistic production in the Middle East,

where ceramicists devised new techniques in order to imitate

Chinese wares. Conversely, the transmission of blue-and-

white pottery decoration moved from the Middle East to

China. The apogee of these developments came substantially

later in the period of the Mongol Empire, when in the 13th

and 14th centuries much of Eurasia came under the control

of the most successful of all the Inner Asian dynasties whose

homeland was in the steppes of Mongolia.

Dan

iel C

. Wau

gh

Left, Timurid tile work may have been influenced by Chinese lacquerware. This example of tile work is from the Mausoleum of Shad-i Mulk, ca. 1372, Shah-i Zinda, Samarkand. Right, a gilded silver Tocharian or Bactrian ewer from the 5th or 6th century CE depicts the story of Paris and Helen of Troy. The ewer was found in the tomb of Li Xian (d. 569) near Guyuan, Ningxia Hui Antonomous Region, China. From the Collection of the Guyuan Municipal Museum.

16 volume 52 , number 3 expedition

ExpedWinter2010.indd 16 12/7/10 10:34 AM

www.penn.museum/expedition 17

˘

The Mongol Ilkhanid palace at Takht-i Suleyman in northwestern Iran (1270–1275) was probably the source of this lusterware tile with a Chinese dragon motif. From the Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (no. C.1970-1910).

Dan

iel C

. Wau

gh

Dan

iel C

. Wau

gh

This modern sculpture, shown with the Registan monuments, Samarkand, in the background, is evocative of the Silk Road. The buildings are the 15th century medrese (religious school) of Ulugh Beg and the 17th century Shir Dor medrese.

Under the Mongols, we can document for the first

time the travel of Europeans all the way across Asia, the

most famous examples being the Franciscan monks John

of Plano Carpini and William of Rubruck in the first half

of the 13th century, and Marco Polo a few decades later.

Genoese merchant families took up residence in Chinese

port cities, and for a good many decades there was an

active Roman Catholic missionary church in China. The

reign of Kublai Khan in China and the establishment of

the Mongol Ilkhanid regime in Iran in the second half of

the 13th century was a period of particularly extensive

exchange of artisans (granted, most of them probably

conscripted) and various kinds of technical specialists.

While their long-term impact may have been limited,

the exchanges included the transmission of medical and

astronomical knowledge. There is much here to temper

the view that the impact of the Mongol conquests was

primarily a destructive one.

Despite the rapid collapse of the Mongol Empire in

the 14th century, under their Ming Dynasty successors

in China and the Timurids in the Middle East, active

commercial and artistic exchange between East and

ExpedWinter2010.indd 17 12/7/10 10:36 AM

West continued into the 16th century. Timurid Samarkand

and Herat were centers of craft production and the caravan

trade. The early Ming sponsored the sending of huge fleets

through the Indian Ocean, which must have flooded the mar-

kets in the West with Chinese goods, among them the increas-

ingly popular celadon (pale green) and blue-and-white porce-

lain. The centers of Chinese ceramic production clearly began

to adapt to the tastes of foreign markets, whether in Southeast

Asia or the Middle East. The legacy of this can be seen in the

ceramics produced in northern Iran, which decorated palaces

and shrines, and in the later collections of imported porcelain

assembled by the Ottoman and Safavid rulers in the 16th and

17th centuries. Persian painting, which reached its apogee in

the 15th and 16th centuries, was substantially influenced by

Chinese models.

Conventional histories of the Silk Roads stop with the

European Age of Discovery and the opening of maritime routes

to the East in the late 15th century. Of course, there had already

long been extensive maritime trade between the Middle East,

South Asia, Southwest Asia, and East Asia. Undoubtedly the

relative value of overland and sea trade now changed, as did

the identity of those who controlled commerce. Yet, despite

growing political disorders disrupting the overland routes,

many of them continued to flourish down through the 17th

century. New trading diasporas emerged, with Indian and

Armenian merchants now playing important roles. Trade in

traditional products such as horses and spices continued, as

did the transmission of substantial amounts of silver to pay

for the Eastern goods. Among the Chinese goods now much

in demand was tea, whose export to the Inner Asian pastoral-

ists had grown substantially during the period of the Yuan and

early Ming dynasties. Trade along the Silk Roads continued,

even if transformed in importance, into the 20th century.

Re-discovery of the Silk Roads

An important chapter in the history of the Silk Roads is the

story of their re-discovery in modern times. Over the centu-

Dan

iel C

. Wau

gh

18 volume 52 , number 3 expedition

On the left is a Ming porcelain dish created in the Jingdezhen kilns, dated 1403–1424. It was donated to the shrine of Shaykh Safi al-Din at Ardebil (northwestern Iran) by Safavid Shah Abbas I in 1611. On the right is a blue and white ceramic imitation of Chinese porcelain, probably from Samarkand, dated 1400–1450, which was produced by craftsmen conscripted in 1402 in Damascus. Both dishes from the Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (no. 1712-1816; no. C.206-1984).

ExpedWinter2010.indd 18 12/7/10 10:36 AM

ries, many of the historic cities along the Inner Asian routes

declined and disappeared as a result of climate change (where

water supplies dried up) or changes in the political map. Only

episodically did the ancient sites attract the attention of local

rulers; at best, oral tradition preserved legends which bore

little relationship to the earlier history of the ruins. In Europe,

it was travel accounts such as that of Marco Polo which

helped to alert early explorers of Central Asia to the possibil-

ity of unearthing traces of Silk Road civilizations now buried

beneath the desert sands.

The foundation for modern Silk Road studies was laid

between the late 1880s and the eve of World War I. Somewhat

by accident, the Swedish explorer Sven Hedin discovered sev-

eral of the ruined towns along the southern Silk Road, includ-

ing Dandan Uiliq, north of Khotan, and Loulan, near the dried-

up bed of Lake Lop Nur. Inspired by such information and

the trickle of antiquities that was now coming out of Central

Asia, the Hungarian-born Aurel Stein, an employee of the

British Indian government, inaugurated serious archaeologi-

cal exploration of the sites in western China. His most famous

accomplishment was to purchase from the self-appointed

keeper of the Mogao cave temples near Dunhuang in 1907 a

significant part of a treasure trove of manuscripts and paint-

ings discovered there only a few years earlier. A year later, the

French sinologist Paul Pelliot shipped another major portion

of this collection back to Europe. In the meantime, pursuing

leads suggested by earlier Russian exploration, German expe-

ditions had been active along the northern Silk Road. There

they removed large chunks of murals from the most impor-

tant Buddhist cave temples in the Turfan and Kucha regions

and sent them back to Berlin. The Germans also found manu-

script fragments and imagery from Christian and Manichaen

temples. Such was the quantity and range of the textual and

artistic materials obtained by these early expeditions that their

analysis is still far from complete. Part of the challenge was

to decipher previously unknown languages and scripts. The

Dan

iel C

. Wau

gh

Mar

co P

olo

from

The

Silk

Roa

d on

Lan

d an

d S

ea, 1

989.

Chi

na P

icto

rial P

ublic

atio

ns, p

. 37,

#20

.

www.penn.museum/expedition 19

In his own lifetime and even today, Marco Polo’s account of his travels has

been branded a falsification. A late medieval reader might have asked how it is

that there could be such wonders about which we have never heard. Why is it,

the modern critic muses, that Marco so often seems to get the facts wrong or fails to

mention something we think he should have included such as the Great Wall or foot-

binding? Of course in any age, the first descriptions of the previously unknown are

likely to engender skepticism. Accuracy in reporting may be conditioned by precon-

ceived notions, the degree to which the traveler actually saw something or perhaps

only heard about it secondhand, and the purpose for which an account was set down.

Marco had his biases—he was an apologist for Kublai Khan and, it seems, really did

work for the Mongols. As an official in their administration, he would not necessarily

have mixed with ordinary Chinese. When he was in China, much of the Great Wall

was in ruins and thus might simply not have seemed worthy of comment. Where

he reports on Mongol customs and certain aspects of the court, he can be very precise. If his descriptions of cities seem

stereotyped, the reason may have been that they indeed appeared equally large and prosperous when judged by European

standards. In any event, to convey the wonders of the Great Khan’s dominions required a certain amount of hyperbole.

It seems unlikely that Marco took notes along the way. Mistakes can thus easily be attributed to faulty memory as well as

the circumstances in which a professional weaver of romances, Rusticello of Pisa, recorded and embellished Marco’s oral

account while the two were in a Genoese prison. Even if Marco’s account still challenges modern scholars, there can be no

question about its impact in helping to transform a previously very limited European knowledge of Asia.

Marco Polo’s Travels: Myth or Fact?

ExpedWinter2010.indd 19 12/7/10 10:37 AM

belated Chinese response to what they came to

characterize as a plundering of their antiquities

finally put a stop to most foreign exploration

by the mid-1930s.

In recent decades, new excavations have

added substantially to our knowledge of this

part of Asia. One focus of Chinese archaeol-

ogy has been on the very early cultures of Inner

Asia, which antedate the traditional “begin-

ning of the Silk Roads.” The ongoing discover-

ies from locations such as the Astana cemetery,

dating from the Tang period, are enabling us

to now write a serious social and economic

history of some of the flourishing oasis com-

munities, in a time when silk was still a major

currency that fueled commerce.

Our knowledge of the cultures in the

northern steppes commenced with the work

of Russian archaeologists beginning at the

end of the 19th century. Russian expeditions

organized by the famous Orientalist Wilhelm

Radloff documented sites in southern Siberia

and northern Mongolia, providing some of the

first evidence about “cities in the steppe” and

helping to publicize the earliest texts in a Turkic

language. Russian-Mongolian expeditions

revealed the richness of Xiongnu elite burials at

the site of Noyon uul (Noin Ula) in the moun-

tains of north-central Mongolia, and were

responsible for the first serious excavation of

the 13th century capital of the Mongol Empire,

Karakorum. Archaeology at sites throughout

the Eurasian steppes has resulted in dramatic

discoveries, and forced us to question many

of our assumptions about when meaningful

exchange across all of Eurasia began.

Yet this is only part of the story, for equally

dramatic discoveries have been made in recent

years regarding maritime trade. From the

East China Sea to the Mediterranean, nauti-

cal archaeology is documenting the cargoes of

everything from scrap metal to fine porcelain.

Excavations along the Red Sea and the East

African coasts have expanded our knowledge

Our knowledge of the mechanisms for commercial

exchange along the Silk Roads is still limited. Most com-

merce was “short-haul” between one oasis or town and

the next, and probably never generated any written records. There

were also long-distance caravans and merchant diasporas often

located far from the “home office.” The Sogdians were involved in

long-distance trade, documented first in Sogdian letters written by

members of that diaspora in the early 4th century, and later from

documents unearthed in the Turfan oasis, among them a famous

example of a contract for the purchase of a slave. Religious affilia-

tion may have bound communities of entrepreneurs who were oth-

erwise isolated minorities in larger population groups. Thus Eastern

Christians (Nestorians) played important roles in trade from the

Middle East to India and beyond. With the rise of Islam, it was not

long before Muslim merchants were resident in the ports of south-

east China and in the Chinese capital of Chang’an. A vast repository

of Hebrew documents preserved in Cairo describes the activities of a

far-flung Jewish community all across the Mediterranean world into

Eastern Europe and through the Middle East. Italian merchants were

active all along the Silk Roads, even sending their representatives to

China in the time of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty.

Although Middle Eastern silk production was by now very sub-

stantial, imports of Chinese raw silk were significant in the emergence

of Italy as a major center of silk weaving. One of the most valuable

sources about products and prices is a commercial handbook com-

piled by the Florentine agent Pegalotti in Constantinople in the 14th

century. In it, he reports that the routes to China are generally safe for

travel. By the late 16th and 17th centuries, Armenian Christians were

placed in charge of the Safavid (Persian) silk trade. One of the most

remarkable documents from this late period in the history of the Silk

Roads is an account book by an Armenian, Hohvannes, who started

at the home office in a suburb of Isfahan, traveled south to Shiraz,

then on to the Indian Ocean coast, where he boarded a ship to India.

Once he arrived in the Mughal Empire, he continued his buying and

selling, aided by a mechanism for cashing in letters of credit and for

shipping goods back home even as he went on, ultimately spending

time in Lhasa before returning to India. Surprisingly, Hohvannes

used double-entry bookkeeping and thus has left us an invaluable,

detailed account of goods and prices.

20 volume 52 , number 3 expedition

Merchant Diasporas and Our Knowledge of Silk Road Trade

ExpedWinter2010.indd 20 12/7/10 10:37 AM

of contacts with India and the Far East. Although long

known from Classical texts, the archaeological evidence of

Roman trade with India continues to grow. Overall there

is now a much greater appreciation of the importance of

long-distance trade through the Middle East starting in the

Bronze Age and continuing well into the era when first the

Portuguese and then the Dutch and English began to dom-

inate the Indian Ocean. Maritime trade throughout history

has been an integral part of Eurasian exchange.

So the “Silk Roads” did not begin when Han Emperor

Wu Di sent his emissary Zhang Qian to the West in the

2nd century BCE any more than they ended when Vasco

Da Gama pioneered the route to India around the Cape

of Good Hope. Our current “Age of Discovery” concern-

ing the history of the Silk Roads, employing sophisticated

www.penn.museum/expedition 21

Dan

iel C

. Wau

gh

A mural of donors (Tocharian princes?) from Kizil Grottoes, Cave 8 (“Cave of the Sixteen Swordbearers”), has been C-14 dated to 432–538 CE. Note the red hair on the men and the intentional defacement of the mural. From the Collection of the Museum of Asian Art, Berlin (MIK III 8691).

A mural brought back to Berlin by German archaeologists depicts Uyghur Buddhist devotees. It was found in Bezeklik, Temple 9, in the Turfan region, and dates to the 8th to 9th century CE. From the Collection of the Museum of Asian Art, Berlin (MIK III 6876a).

ExpedWinter2010.indd 21 12/7/10 10:37 AM

analytical tools such as DNA testing and remote sensing from

satellites, at the very least should persuade us that the study of

this history is still young. Who knows what secrets remain to

be uncovered from the desert sands?

daniel c. waugh is Professor Emeritus in History, International Studies, and Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Washington in Seattle. He is the current direc-tor of the Silk Road Seattle Project and editor of the journal of the Silkroad Foundation.

For Further Reading

Baumer, Christoph. Southern Silk Road: In the Footsteps of Sir Aurel Stein and Sven Hedin. Bangkok: Orchid Press, 2000.

Hulsewé, F. P., and M. A. N. Loewe. China in Central Asia: The Early Stage: 125 B.C.–A.D. 23. An Annotated Translation of Chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. Leiden: Brill, 1979.

Jackson, Peter, and David Morgan, trans. and eds. The Mission of Friar William of Rubruck: His Journey to the Court of the Great Khan Möngke 1253–1255. London: Hakluyt Society, 1990.

Juliano, Annette L., and Judith A. Lerner. Monks and Merchants: Silk Road Treasures from Northwest China: Gansu and Ningxia, 4th–7th Century. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., with The Asia Society, 2001.

Komaroff, Linda, and Stefano Carboni. The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256–1353. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

Qi, Xiaoshan, and Wang Bo. The Ancient Culture in Xinjiang along the Silk Road. Ürümqi: Xinjiang renmin chubanshe, 2008.

Tucker, Jonathan. The Silk Road: Art and History. London: Art Media Resources, 2003.

Whitfield, Roderick, Susan Whitfield, and Neville Agnew. Cave Temples of Mogao: Art and History on the Silk Road. Los Angeles: Getty Institute and Museum, 2000.

Whitfield, Susan. Life along the Silk Road. London: John Murray, 1999.

Whitfield, Susan, and Ursula Sims-Williams. The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. Chicago: Serindia Publications, 2004.

Websites

Digital Silk Road (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/).

Silk Road Seattle (http://depts.washington.edu/silkroad).

The International Dunhuang Project (http://idp.bl.uk).

The Silkroad Foundation (http://silkroadfoundation.org).

22 volume 52 , number 3 expedition

Dan

iel C

. Wau

gh

About 130,000 ceramic vessels were recovered from a shipwrecked Chinese junk near Ca Mau, Vietnam. The tea bowls and saucers are from the Jingdezhen kilns and were made around 1725, apparently the year that the ship sank en route from Guangzhou to Batavia (Jakarta). From the Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (nos. FE.49:2 to 179:1, 2-2007).

ExpedWinter2010.indd 22 12/7/10 10:37 AM

www.penn.museum/expedition 23

The Mummies of East Central Asia

by victor h. mair

In 1988, while visiting the Ürümqi Museum in

China, I came upon an exhibition which changed

the course of my professional life. At the time, my

academic career focused on the philological study of

manuscripts from caves at Dunhuang, a site where

the Silk Road splits, proceeding to the north and south. But

after I walked through black curtains into a dark gallery that

day, my fascination with the mummies of East Central Asia

began. At first, I thought the exhibition was a hoax, because

the mummies looked so lifelike. The colors of the textiles they

wore were vibrant. The associated bronze tools and other

objects from 3,000 to 4,000 years ago could not, I thought,

have been found in this region at such an early period. At that

time, I was not an archaeologist, but my general knowledge of

Chinese history and Central Asian sites indicated that this did

not make sense. I stayed in that gallery for probably five hours

that day.

I went back to my life at Penn as a scholar of medieval

Buddhist literature and Chinese popular Buddhist literature.

In the fall of 1991, while on sabbatical, I read of the discovery

of Ötzi the Iceman in the Alps near the border between Austria

and Italy. Ötzi, over 5,000 years old, had been naturally mum-

mified in the Schnalstal glacier. That afternoon, I started mak-

ing calls to organize an expedition to China to study the mum-

mies that had been naturally preserved there. Since 1993, I

have traveled to China numerous times with different kinds of

scholars—archaeologists, geneticists, textile specialists, bronze

experts—to study the Central Asian mummies and the cul-

tures they represented.

Dan

iel C

. Wau

gh The Beauty of Xiaohe is one of over 30 well-preserved mummies found at the site, and certainly the most famous.

Xin

jiang

Inst

itute

of

Arc

heol

ogy

Col

lect

ion

ExpedWinter2010.indd 23 12/7/10 10:37 AM

24 volume 52 , number 3 expedition

Em

ily T

oner

, aft

er V

icto

r M

air

A History of the Region: Where the Mummies

Were Discovered

During the late 19th century, a large region of East Central Asia

was forcibly incorporated into the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912)

through conquest by the Manchus. As a result, the region

became known as Xinjiang, which means “New Borders.”

This area—referred to by the local Uyghurs (a Turkic ethnic

group) as Uyghurstan or Eastern Turkistan—regained its

independence during the first half of the 20th century, after

the collapse of the Qing Dynasty. The People’s Republic of

China (hereafter China), however, militarily asserted its claim

as the legitimate successor to most of the lands of the Manchu

Empire during the second half of the 20th century, and rein-

corporated this region as the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous

Region (hereafter Xinjiang).

The region constitutes 1/6 of the whole of China and,

apart from its obvious geostrategic significance, is blessed

with oil and other mineral resources, has rich agricultural

lands (especially for animal husbandry), and is where China

tests its nuclear weapons. Consequently, since the late 1970s,

the Communist government has made a concerted effort to

develop the region.

As is true elsewhere in China and other parts of the world,

wherever the construction of buildings, roads, and other pub-

lic projects is carried out, archaeological discoveries are likely

to be made. There has been an endless succession of finds in

Xinjiang from the Bronze Age and Iron Age right up to mod-

ern times. Because of its remoteness from the centers of early

human development and its inaccessibility—in the form of

harsh deserts surrounded by formidable mountains—East

Central Asia was one of the last places on earth to be inhabited

by humans. Thus, the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods are

poorly represented. From the Bronze Age (beginning ca. 2000

BCE) onward, however, this region was a key locus of interac-

tion between western and eastern Eurasia. During the 2nd and

1st millennia BCE, the overwhelming majority of the traffic

was from west to east, but starting around the beginning of the

Common Era, transcontinental exchange gradually shifted,

moving now more from east to west. Of course, some indi-

viduals and groups continued to travel from west to east—for

example, for trade, diplomacy, and religion. The result of this

traffic, travel, and exchange across Eurasia was a great mixing

of cultures and peoples, with East Central Asia constituting a

vital contact zone at the very center of the continent.

Despite the inhospitable climate—temperatures range

from -40 degrees C to +40 degrees C (-40 to 104 degrees F)—

tens of thousands of individuals

poured into East Central Asia and

settled down in oases, intramontane

valleys, and wherever they could

eke out a living. Since this area was

so far from the steppes, the coasts,

and the major plains and river val-

leys of Eurasia, there was not much

competition for the settlements

after they were established. Still,

having found an ecological niche

and having devised unique means

for subsisting there, the inhabitants

thrived, leaving behind large cem-

eteries.

Hundreds of archaeological

sites scattered across the length and

breadth of East Central Asia date to

every century starting from about

4,000 years ago. Many of these This map shows archaeological sites in East Central Asia that are discussed in this article.

ExpedWinter2010.indd 24 12/7/10 10:38 AM

sites are cemeteries of considerable extent, often with hun-

dreds of burials. Nearly all burial grounds in the region have

yielded abundant skeletal remains. Due to the local conditions

(extreme aridity and sandy, highly saline soil), dozens of cem-

eteries around the southern and eastern edges of the Tarim

Basin contain extraordinarily well-preserved mummies,

together with the textiles in which they were dressed and the

artifacts that accompanied them to the afterworld.

It should be noted that the so-called mummies of East

Central Asia are actually desiccated corpses. Unlike Egyptian

mummies, their lifelike appearance is due not to any artificial

intervention on the part of those who buried them. Rather,

it is the outcome of the special environmental conditions

described above, with the best-preserved bodies being those

who died in winter and were buried in especially salty, well-

drained soils—all of which would inhibit putrefaction and

prevent deterioration; after thousands of years, not even slight

amounts of moisture penetrated these burials.

The early inhabitants of this region did not belong to a sin-

gle genetic and linguistic stock, nor did they come from a sin-

gle source. Instead, they entered the Tarim Basin at different

times and arrived from different directions. In earlier periods,

they came from the north, northwest, west, and southwest.

During later periods, these migrations continued, but groups

came from all directions.

Although the mummies from the first 2,000 years (2nd and

1st millennia BCE) were manifestly Caucasoid in appearance,

careful physical anthropological and genetic studies reveal

that they possessed a variety of characteristics linking them

to diverse groups outside of the region. Beginning about the

time of the Eastern and Western Han Dynasties (206 BCE–9

CE; 25–220 CE), the proportion of Mongoloid traits from

the east progressively increased until now the Uyghurs,

Kazakhs, Kirghiz, and other non-Sinitic (non-Chinese)

peoples in the region are between a 30/70% and 60/40%

Caucasoid/Mongoloid admixture. During the more than 50

years of China’s rule over Xinjiang, there has been a dramatic

increase in the number of people of Sinitic (so-called Han

Chinese) descent entering the region, such that the previously

admixed Turkic and other non-Sinitic peoples—who used to

constitute over 90% of the population—now amount to only

about 50%, with the other half made up of rapidly in-migrat-

ing Han Chinese.

Cemeteries of East Central Asia

The human history of East Central Asia begins about 3,500 to

3,800 years ago, with three sites just to the west of the fabled

city of Loulan (also known as Kroraina in the Prakrit language,

and Krorän in Uyghur), which lies to the northwest of the great

dried-up lake known as Lop Nur. These sites are Gumugou

(Qäwrighul), Tieban (Töwän), and Small River Cemetery 5

(SRC5, Xiaohe, Ördek’s Necropolis). While the burials are

laid out somewhat differently at the three sites—Gumugou

features hundreds of wooden posts radiating in what may be a

solar pattern, Tieban has shallow burials on terrace land, and

Small River Cemetery 5 is a striking 7 m high mound of sand

with five layers of burials in the middle of the desert—prox-

imity of time and place, plus a number of common features,

certify that Gumugou, Tieban, and SRC5 belong to a single

www.penn.museum/expedition 25

Em

ily T

oner

, aft

er V

icto

r M

air

Xin

jiang

Inst

itute

of

Arc

haeo

logy

The cemetery site of Xiaohe, shown here with wooden posts and boat-shaped coffins, has been completely excavated.

ExpedWinter2010.indd 25 12/7/10 10:38 AM

cultural horizon. Among the shared features of these sites

are plain-weave, natural color woolen mantles that serve as

shrouds, felt hats with a feather inserted at the side, ephedra

(a medicinal plant) deposited in the grave, finely woven grass

baskets rather than ceramics, and evidence of bronze usage.

Among the most spectacular of the mummies from Small

River Cemetery 5 (hereafter Xiaohe) is a female that has come

to be called “The Beauty of Xiaohe” (ca.1800–1500 BCE) (see

page 23 and above). She is more than a match for “The Beauty

of Loulan,” a mummy dated to ca. 2000 BCE that was found

at Gumugou in 1980. The Beauty of Xiaohe is very well pre-

served and even retains flaxen hair and long eyelashes. She

was wrapped in a white wool cloak with tassels and wore a felt

hat, string skirt, and fur-lined leather boots. She was buried

with wooden pins and three small pouches of ephedra. The

Beauty of Loulan wears garments of wool and fur and a felt

hood with a feather; she was buried with a comb, a basket,

and a winnowing tray.

Among the other striking aspects of the Xiaohe cemetery

are six surrogate mummies made of wood, with leather for

skin, hair, and mustache sewn on, and a full set of clothing.

Since all six of these artificial mummies are male, and all six

were buried at about the same time, we may speculate that

they represent men who died away from home and whose

bodies were never recovered.

What is even more remarkable than the two “Beauties”

or the connections between these three sites south of the

26 volume 52 , number 3 expedition

Jeff

ery

New

bury

, Kai

lun

Wan

g (s

ideb

ar)

One will never know what kind of person the Beauty of Xiaohe was in life. Death

and time separate the Beauty from us like the shroud wrapped around her body.

She seems to be part of two worlds: one of life, for she appears merely asleep, and

one of mortality. The discovery of her mummy was a revelation, and yet much of her history

remains an enigma. Even though she is thousands of years old, her youthful appearance is

well-preserved. I was inspired to create this painting by the Beauty’s famed attractiveness and

the mysteries surrounding who she may have been in life. Three drafts were created: the first

an observational study; the second, a woman gazing at the viewer; and finally, a third draft

that was ultimately painted, portraying the Beauty in a serene atmosphere with an inexpli-

cable sense of both gentleness and isolation. Although artistic liberties were taken with her