Exodus of the Dogs

-

Upload

nadine-siegert -

Category

Documents

-

view

72 -

download

4

Transcript of Exodus of the Dogs

EXODUSOF THE DOGS

Okwui Enwezor

with an introductionby JO RACTLIFFE

Jo Ractliffe, Nadir (no. 15), 1988. Screenprinted lithograph, 55 x 86 cm.

4_enwezor:nka_book_size 2/28/10 6:19 PM Page 60

I’vemade three trips to Luanda this year and have ac-cumulated a lot of quite diverse material. In makinga final edit, I looked to extract those images that

best articulate my concerns both photographically andconceptually. And I have to say I’ve struggled quite a bitwith this project and finding my way through it has beena real challenge!

I didn’t go to Luanda with any specific intention or pre-conception about what to photograph. That’s not entirelyunusual for me; my general tendency is to work “in re-sponse” to an idea or situation rather than to predeter-mine things—beginning with something somewherebetween contingency and intention. What was differentthough was I’ve just about always photographed in SouthAfrica; it’s my home and so it’s a place I can assume atleast some familiarity with, even if the relationship is notalways a comfortable one. Angola was different; I’d neverbeen there before and I knew little about it, beyond thewar, so my position there, in relation, was going to be pre-carious. And also, my interest was particularly the imagi-nary of Angola, the place it occupies in South Africa’shistory and the ways it has figured in this country’s—andmy—imagination. So altogether, some tricky stuff for meto take on in this context.

I first read about Angola in Another Day of Life,Ryszard Kapuściński’s book about events leading up toAngola’s independence. This was during the mid-1980s—some ten years after it was written. I was very struck bythat book, especially the ways it resonated with what washappening in South Africa then—a period of intense re-sistance and increasing mobilization against the forces ofthe apartheid government, which took extreme measuresin countering anything it perceived as a threat—both fromwithin and outside its borders. There was virtually a con-tinuous State of Emergency declared from the mid-1980suntil the release of Mandela in 1990; SADF troops movedinto the townships and of course, South Africa was alsofighting in the war in Angola. At the time, I was photo-graphing in the townships around Cape Town—imagesthat would form the apocalyptic photomontages of Nadir.

And among other books on landscape, dispossession, andwar, I was reading about Angola. (There’s a wonderfulpassage in Kapuściński’s book about the dogs in Luanda,abandoned when the Portuguese left, which inspired thedogs of my Nadir series.) But until then, in my imagina-tion, Angola had been an abstract place. In the 1970s andearly ’80s, it was simply “the border,” a secret, unspokenlocation where brothers and boyfriends were sent as partof their military service. And although tales about Rus-sians and Cubans and the cold war began to filter back—all of which conjured up a distinctly different image fromthe one portrayed by the South African state—it re-mained, for me, largely a place of myth.

All this was very much in my mind when I first wentto Luanda in March 2007. It was five years since the warhad ended (it was also the year of Kapuściński’s death).My first impulse was to look for that mythical landscape;I had a vague notion to embark on a search for “Kapuś-ciński’s lost dogs” and I made a list of places from hisbook, starting with room 47 in the Tivoli Hotel, which waswhere he had stayed in 1975 (it’s still there). I was notlooking to produce a commentary on the “state of things”in Luanda now. I went in search of something else. Em-blematic things. Traces of that imaginary Angola. But iron-ically, as it turned out, I found myself needing to do almostthe opposite once I was there. Which also brings to methe second challenge: how to photograph.

I knew I wanted to “shoot straight,” as it were. Forquite some time, even previous to this project, I’d beenwanting to break away from what seems to have becomemy signature mode—plastic cameras, dissembled subjectmatter, furtive looking, those “filmstrip”-like sequences,and so on. I didn’t want to rely on those conventions andtheir mediations as a way to speak. Rather, and especiallyin Luanda, I wanted to engage with photographic seeingin a more direct sense—careful looking, clarity, focus, andthe acknowledgment of a “subject,” as it were. And whileI took my plastic cameras, I decided to use my medium-format Mamiyas and shoot with black-and-white film. Allthis calls up documentary in a much more immediate way

Nka•63Journal of Contemporary African Art62•Nka

Terreno Ocupado: Extracts from Lettersto Okwui, November 2007

JO RACTLIFFEINTRODUCTION

Vacant plot near Atlantico Sul, 2007.

4_enwezor:nka_book_size 2/28/10 6:19 PM Page 62

Journal of Contemporary African Art64•Nka

gorge edge giving way to a spectacular vista. And whilenone of my shooting was emphatically toward that end(in other words, intentionally panoramic) and conse-quently the diptychs, triptychs, and other sequencesaren’t seamless, I quite like that “off” quality that re-sults—something like stereoscopic images that have goneawry and won’t line up for perfect 3-D viewing.

Something that continues to be striking for me is thepalpable presence of myth. It’s partly in the way peopletalk about themselves and their narration of history, butalso how they articulate the relationship of the past to thepresent and how this present works in terms of imagininga future—it seems to be a very particular understandingof things. I’m sure some of this is my projection and ofcourse, my foreignness, and there’s also the thing of lan-

guage, which makes for rather interesting communicationat times, but I have been acutely aware of something quitedistinctive in Angola, for all that it may be very much acontemporary African city. Many times I felt as if I wereentering a world that was simultaneously post-apocalyp-tic and medieval—MadMax meets The Canterbury Tales.Some of this may have to do with my imaginings, or thestrange contradictions in the built environment—Por-tuguese, Russian, Cuban, and now all the new oil high-rises. But I was very aware of the past within the present,as if what I was looking at was a screen for somethingelse. And this is what I’ve wanted to work with in theseimages.

than my work usually does—or at least, locates me withinthe convention, rather than my customary position ofbeing somewhere at the edge of things. I was rather nerv-ous about this; whether and how I would still be able towork critically, self-reflexively, without resorting to myusual strategies of destabilization. And this remains myongoing dilemma with photography; my need for mimesis,an anchor to the real, but equally, my need to shift the fix-ity of the photograph, to call into question the acceptanceof the real and insert something of the “unreality” of ex-perience—if this makes any sense. Which also raised thequestion of my own position, as a photographer, in a placethat’s not “mine,” and how I could reflect this in the im-ages. And maybe that’s where the need for specificity,careful looking, and “straight shooting” comes in. Be-cause that kind of analysis helps you understand who youare and what you’re looking at better. So, all in all, thisproject has taken me full circle—back to a landscape (realand imaginary) that occupied me twenty-odd years agoand to the same dilemmas I had then about photographyand how to have my way with it.

I have decided to make darkroom prints; I think printquality is critical and I’ve grown a bit weary of the “per-fection” of digital printing. I’m more limited in the dark-room, but I think in silver prints I would better achieve thevisceral texture of Luanda’s urban landscape—its hazygrittiness and those murky skies. I’ve been experimentingwith various papers, looking at different tones of black andwhite—there’s quite an interesting warm-toned paper thatworks well with my sense of the place; it gives the printsa rather curious “old-fashioned” look that’s not the usualpunchy black and white you’d expect from contemporarydocumentary.

I’ve also been thinking a lot about how to organize allthe material. Because I think there are a number of thingshappening across the whole body of work, both in termsof how I was looking as well as what I was looking at, I’veneeded to find a way both to mark the distinctions as wellas make the connections I feel are important. And moreparticularly—and this in mitigation of documentary—I’vealso wanted to bring something of what I think of as the“emblematic” to the fore. So I’ve been playing with certaingroupings of images and ideas around sequences andcomposite works; I was aware when photographing fromthe edge of Roque Santeiro looking across Boa Vista, ofthe conventions of colonial painting and photography, thatway of surveying the land—all those images from on topof a hill, usually with an aloe in the foreground and the

Smoking rubbish at the edgeof Roque Santeiro market (triptych), 2007.

Nka•65

The cliffs of Boa Vista (polyptych), 2007.

4_enwezor:nka_book_size 2/28/10 6:19 PM Page 64

Nka•67Journal of Contemporary African Art66•Nka

Diorama at the Museu de Historia Natural (3), 2007. Diorama at the Museu de Historia Natural (1), 2007.

4_enwezor:nka_book_size 2/28/10 6:19 PM Page 66

Nka•69Journal of Contemporary African Art68•Nka

Mausoléu de Agostinho Neto, 2007. Man maintaining the lawn of the Monumento de Agostinho Neto, 2007.

4_enwezor:nka_book_size 2/28/10 6:19 PM Page 68

Nka•71Journal of Contemporary African Art70•Nka

Sculpture in a park in Bairro Azul (1), 2007. Detail of tiled murals at the Fortaleza de São Miguel, depicting Portuguese exploration in Africa (3), 2007.

4_enwezor:nka_book_size 2/28/10 6:19 PM Page 70

Nka•73Journal of Contemporary African Art72•Nka

Detail of tiled murals at the Fortaleza de São Miguel, depicting Portuguese exploration in Africa (2), 2007. Detail of tiled murals at the Fortaleza de São Miguel, depicting Portuguese exploration in Africa (4), 2007.

4_enwezor:nka_book_size 2/28/10 6:19 PM Page 72

Nka•75Journal of Contemporary African Art74•Nka

Roadside stall on the way to Viana, 2007. Diorama at the Museu de Historia Natural (2), 2007.

4_enwezor:nka_book_size 2/28/10 6:19 PM Page 74

Nka•77Journal of Contemporary African Art76•Nka

Shack on the Boa Vista cliff edge, 2007. Woman on the footpath from Boa Vista to Roque Santeiro market, 2007.

4_enwezor:nka_book_size 2/28/10 6:19 PM Page 76

Nka•79

A remarkable aspect of Jo Ractliffe’s work isthe idea, pursued with relentless asperity,that photography, above all else, is a way of

seeing; that it is much more than what it depicts.Therefore, her work is never about using photogra-phy to produce evidence or as a medium of strictlydocumentary truth. Far more complex mechanismsare at work in her images, making her field of inves-tigation an always contingent, throbbing space inwhich to fit together the pieces of the puzzle be-tween an image that refers to an external other, anda visuality that references nothing but itself.1 Thesetwo terms of thinking are simultaneously grappledwith in Ractliffe’s work, whose photographic proce-dures completely eschew any notion that an imagecan be produced from a sense of objectivity. In herwork, to see—particularly in the treacherous case ofSouth Africa where, despite appearances of black-and-white moral clarity, things are far murkier thanoften revealed—is to see beyond what the image re-veals itself to be, whether as a reality on the edge ofwhich the photographer stands as a witness, or as aself-sufficient visual field closely related to the mod-ernist tautology of a work of art as autonomousfrom its referent.

For twenty-five years these concerns have re-mained the constants in Ractliffe’s work, a regimeof thinking that prioritizes analytical reflection. Inthe 1980s, as the larger international world began aconcerted campaign against the ideology of theapartheid state, Ractliffe was part of a young gener-ation of artists whose works began appearing inpublic in a moment of deep uncertainty and anxietyabout the fate of South Africa. This decade wasformative for many artists and writers, many of

whom worked in the glare of dramatic historicalevents. Artists grappled with the place of the artis-tic image, the nature of representation, and the sta-tus of the work of art under conditions of politicalinstability, social malaise, and forms of cultural re-sistance that made the practice of art as much anethical purpose and radical refusal as it was a cri-tique of the moral disaster brought about by the ide-ology of monocultural racism. The legacy of thisperiod and its continuing and unfolding after-ef-fects still inform Ractliffe’s work, yet in telling waysher work has moved on.

Reflecting this period of strangeness, doubt, andapprehension, an eerie sense of doom pervades theearly photographs and photomontages Ractliffeproduced between 1985 and 1989. The settings ofthese images—the Crossroads squatter camp on theoutskirts of Cape Town; Vissershok, a large landfillnot far from the city—seem to mirror the larger rotin the heart of the apartheid system. The landscapeof this pictorial thinking might appear to observerslike a dystopian hell, as if these spaces were origi-nally part of the set of the Mad Max movies, inwhich the bleak prospects of man and animal be-come finally joined. These harsh, unsentimentalimages, taken at a time of escalating confrontationbetween the apartheid regime and its opponents,are preternatural premonitions of the rusty rum-bling sounding in the creaky joints of a decrepit anddespised totalitarian machine.

Produced over a period of intense and inspiredwork, as if in a fit of creative delirium, just aftergraduating with distinction from the University ofCape Town, the images from Crossroads inscribe ahaunted, depopulated, ransacked landscape. Look-

Journal of Contemporary African Art78•Nka

EXODUSOF THE DOGSOkwui Enwezor

Crossroads, 1986.

4_enwezor:nka_book_size 2/28/10 6:19 PM Page 78

author, Ryszard Kapuściński, reports on the end ofthe Portuguese empire in Angola after the defeatof the colonial system in 1975 by the armed resist-ance, led by the bespectacled poet, surgeon, andAngolan revolutionary/national hero AgostinhoNeto. Ractliffe sent me a passage from the book, inwhich Kapuściński describes, with lyrical precision,the condition of the port city and capital, Luanda, justbefore it fell to the rebels. Luanda had become a cityof dogs. Kapuściński describes a scene in a bravurapassage of reporting and narrative distillation:

The dogs were still alive.

They were pets, abandoned by owners fleeing inpanic. You could see dogs of all the most expensivebreeds, without masters—boxers, bulldogs, grey-hounds, Dobermans, dachshunds, Airedales, spa-niels, even Scotch terriers and Great Danes, pugs andpoodles. Deserted, stray, they roamed in a great packlooking for food. As long as the Portuguese army wasthere, the dogs gathered every morning on thesquare in front of the general headquarters and the

Nka•81

ing back now, these photographs are nothing lessthan icons of damaged life—black and white sub-jects alike—and the archaeological site of a brutalnecropolitics.2 In one photograph, fresh tire marksleft on muddy ground lead into a far-off space lit-tered with the mangled remainders of bulldozedshacks that are scattered like carcasses across thecharred landscape. In another, an unstablemakeshift architecture—pieced together with noth-ing more than cardboard, ragged tarpaulin, andtwigs—totters on the edge of a refuse-strewn poolof putrid water. In yet another, stray dogs scroungefor food; in the center of the image an albino dogstares with leaden eyes at the camera from a smallhill of garbage, while just beyond, indecipherablefigures lounge amid ramshackle surroundings.These images invite comparisons to apocalypse. InVissershok, a series shot in Cape Town’s VissershokLandfill, one glimpses a vast scene of labor filledwith scavengers—humans and animals alike—whofeed on the scraps deposited by an oblivious andwell-fed populace far removed from the gnawinghunger that drives many to the garbage heap in abid for survival. Vissershok is the most sinister ofimages, a zone of ecological debacle that leaves theviewer peering into its apocalyptic insinuations.Ractliffe photographs its many contours with such

ebullient restraint, placing her vantage point at aslightly distant remove.

The culmination of this period of intense work,in which depopulated, ominous landscapes andstray dogs serve as symbols of moral decadence, isNadir, a series of photomontages set in spaces evenmore bleak and threatening than those in Cross-roads and Vissershok. In fact, most of the backdropof Nadir derives from images from the two earlierseries. In Nadir, Ractliffe shows her cards, address-ing directly what she sees as apartheid’s ideologicalobsolescence. The stars of the series are packs ofdogs, depicted in an array of settings—a tenteddesert work camp reminiscent of a scene in J. M.Coetzee’s 1980 novel Waiting for the Barbarians, amontaged landscape of oil drums filled to the brimwith rubbish, a busted oil pipeline snaking throughwhat appears to be a stadium of some sort againsta horizon filled with dense, black smoke—and con-figurations—as a fornicating lot, in pairs, or as soli-tary forms racing through portentous spaces in ablur of fury and mangy fur. Nadir is a work of un-remitting power and forceful intent. In it Ractliffeshifts radically from the articulated landscape to anoneiric, fugue-like mythopoesis.

Her inspiration for this body of work was thebook Another Day of Life, 1976, in which the Polish

Journal of Contemporary African Art80•Nka

(Left and Right): Crossroads, 1986.

Vissershok, 1988.

4_enwezor:nka_book_size 2/28/10 6:19 PM Page 80

how great works of art endure, and the vistas theyare capable of opening. The images show us herachievement as an artist. In the early 1990s,Ractliffe relocated from Cape Town, that bastion ofcolonial life where she was born, to Johannesburg,a city still very much connected to its history ofgold-rush buccaneering. After losing all her profes-sional photographic equipment in a theft, and un-able to replace it in the immediate term, she beganexperimenting with a 120mm plastic toy cameracalled the Diana. Her experiments with this camerayielded a group of rough, smudgy, almost tactileblack-and-white-photographs, whose mostly gray-black tones appear as if filmed with a movie cam-era. The darker mood of these images contrastsradically with the earlier photographs, especiallythose from Vissershok, which look as if they wereliterally excavated from a limestone quarry giventhe harshness of the almost blinding whites of someof the pictures. After the fever of the work of the1980s, she was working in a slower, more deliberatefashion, and she began to hatch a new body of workthat saw her shift to a more experimental, riskierphotographic position.

Beginning in the 1990s, Ractliffe’s métier be-came—this has proven to be unavoidable in muchSouth African art—intimately concerned with theshifting conditions of the South African landscapeand its urban spaces. ReShooting Diana, the firstmajor series she produced during the decade, sawa shift in her persistent use of the road trip as amechanism for moving across the expansive, an-cient landscape of the country. In her move fromCape Town to Johannesburg, she drove cross-coun-try in a 2,000-kilometer journey through the GreatKaroo Desert, stopping and photographing orshooting from her car window as she traveledthrough the small towns that dot the route. Theidea of road trip, or the photographic journey, wasundertaken almost in the fashion of Robert Frank’sepic journey in 1955–1956 across the United Statesthat culminated in a landmark documentary pho-tography book, The Americans.3 But for Ractliffe,the road trip was more a conceptual structure formapping the epic imagination of South Africa’s var-ied spatial settings. Yet, by no means does her proj-ect resort to the seduction of the grandiose.

Instead, in reShooting Diana, a long solitary

Nka•83

sentries fed them canned NATO rations. It was likewatching an international pedigreed dog show. Af-terward the fed, satisfied pack moved to the soft,juicy mowed grass on the lawn of the GovernmentPalace. An unlikely mass sex orgy began, excited andindefatigable madness, chasing and tumbling to thepoint of utter abandon. It gave the bored sentries alot of ribald amusement.

When the army left, the dogs began to go hungryand slim down. For a while they drifted around thecity in a desultory mob, looking for a handout. Oneday they disappeared. I think they followed thehuman example and left Luanda, since I never cameacross a dead dog afterward, though hundreds ofthem had been loitering in front of the general head-quarters and frolicking in front of the palace. Onecould suppose that an energetic leader emerged fromthe ranks to take the pack out of the dying city. If thedogs went north, they ran into the FNLA. If theywent south, they ran into UNITA. On the otherhand, if they went east, in the direction of Ndala-tando and Saurimo, they might have made it intoZambia, then to Mozambique or even Tanzania.

Perhaps they’re still roaming, but I don’t know inwhat direction or in what country.

After the exodus of the dogs, the city fell into rigormortis. So I decided to go to the front.

Nothing could be more gripping, and Ractliffemore than equals the captivating, sinewy climax,and uses the composite structure of the photomon-tages to bind Nadir’s various aspects, except, ratherthan Luanda, she was describing South Africa, justas the whites began their mass exodus, in anticipa-tion of the coming of black political power. Nadir,though, is more than about South Africa and An-gola; it reflects the general ambiguity of whiteAfricans’ relationship to the continent at momentsof transition to black African rule. When viewingthese images, Coetzee’s controversial novel, Dis-grace, 2000, comes to mind—particularly the scenewhere the dogs are slaughtered.

These images irrefutably secured Ractliffe’sstature as one of South Africa’s most rigorous andcompelling artists. Looking at the images today,twenty years after they were made, reminds us of

Journal of Contemporary African Art82•Nka

Nadir (no. 14), 1988. Screenprinted lithograph, 54.5 x 87.5 cm. Nadir (no. 16), 1988. Screenprinted lithograph, 55 x 85 cm.

4_enwezor:nka_book_size 2/28/10 6:19 PM Page 82

in the kind of humanism from which some of themost outstanding works in South Africa have beenmade. Her humanism is not about social situations,nor about the depredations that oppress daily lifein South Africa, but about the inchoate, about mo-ments yet to achieve full definition.

Though her work exists alongside the work ofbetter-known male artists and photographers—notably Guy Tillim, Santu Mofokeng, David Gold-blatt, and Zwelethu Mthethwa—and may some-

times invite comparison with their work, suchcomparison is immediately blunted by her singu-larly unique approach to documenting the SouthAfrican landscape. Ractliffe tends to be more inter-ested in the quality of the unseen, the elapsed, theyet to emerge, rather than focusing on the ponder-ous concreteness of moments that often give SouthAfrican spatial situations an effusive realism de-picting readymade symbols of ideological deca-dence. In both their colonial and their apartheid

Nka•85

drive through the Great Karoo Desert strongly re-sists the cliché of the road trip in which the pho-tographer transforms herself into a tourist of hercountry’s heartland. Rather than large themes, theimages are more like fragments, notations that side-step mordant narratives of the self, country, oridentity. Rather than a search for identity, she wasdispossessing, through these images, any narrativethat may lead to identification. As she documentedthe fleeting scenes, lives, and communities aban-

doned in the forlorn and isolated way stations set inunforgiving environments, the images of reShootingDiana are recast, not as a rite of passage, but as apictorial vehicle of defamiliarization and dedrama-tization of the allure of touristic discovery. In hergestures and experiments with visual complexity,and her choices that eschew the heroic for the an-tiheroic, Ractliffe is unlike her male counterparts.Her work cuts against the grain of what could betermed the camera-ready. Yet her work is invested

Journal of Contemporary African Art84•Nka

(Top left): reShooting Diana (barrier), 1990–95. (Top right): reShooting Diana (Christmas), 1990–95.(Bottom left): reShooting Diana (doll’s head), 1990–95. (Bottom right): reShooting Diana (microlite), 1990–95.

(Top left): reShooting Diana (refinery), 1990–95. (Top right): reShooting Diana (welcome), 1990–95.(Bottom left): reShooting Diana (strawberry man), 1990–95. (Bottom right): reShooting Diana (butcher), 1990–95.

4_enwezor:nka_book_size 2/28/10 6:20 PM Page 84

amplifying the farm’s solitariness and isolation anddirecting the viewer to the two qualities that musthave made Vlakplaas appealing and conducive forthe purposes for which it was deployed. Vlakplaasis an ordinary-seeming, innocuous farm, with afarmhouse standing behind a low chain-link fence,in a slightly unkempt field of brush and grass, anda well-trodden unpaved road curving into theproperty. Despite its unassuming, even drab qual-ity, the site is one of the most grotesque of apartheidlandscapes. Located on the outskirts of Pretoria, thefarm was used by secret apartheid death squads asa place where captured opponents of the regimewere tortured, killed, dismembered, and inciner-ated. However, nothing in the image of this norma-tively “ordinary” place has the capacity ofconveying its horrific history, nor the ability to reg-ister, in visual language, the horrors that took placethere, the appalling crimes that were committedagainst political activists in the name of state ideol-ogy. However, to be clear, the quality of absence inthe images of Vlakplaas that Ractliffe excavates isfundamentally different from any idea that will sit-uate and posit the scene of the crimes as “unrepre-sentable.”

Paradoxically, Vlakplaas—as a site in its very in-nocuousness—falls outside Ndebele’s category ofsocial exhibitionism, simply because its brand ofexhibitionism reveled in meaningless and sadisticviolence, in the grotesquery of unaccountability ei-ther before the law or to the public. Because noneof these qualities is depictable, Ractliffe neverthe-less did not attempt the kind of easy ambivalencethat would have insisted on the term “unrepre-sentable” as a way out of the moral conundrum ofdepicting Vlakplaas. For indeed, the site had be-come an object of fascination and had acquired alegendary notoriety that demanded that it be ad-dressed not as a symbol, but as a site. She thus re-sorted, in the video part of the work (after initiallyphotographing the site in a series of single-frameimages, Ractliffe rephotographed them by slowlyscanning a handheld video camera across the im-ages to produce the accompanying video) to audiosnippets of testimony by Dirk Coetzee, one of theprincipal agents employed at Vlakplaas, recordedduring the Truth and Reconciliation Commissionhearings to which he had applied for amnesty, in

which he describes what viewers are unable to seein the images. In so doing, Ractliffe shows that thecrimes of apartheid were not always photograph-able from a conventional viewpoint, and oftentimesdo slip out of view of the camera’s tracking system.Yet, at the same remove, she shows that such sub-jects can be representable through other devices,through acts of testimony. If Ractliffe exploits thecondition of the unphotographable, the ur-imageof erased violence, it is to call attention to the gapsthat lurk in the pictorial imagination. She turnsthose gaps into a revealing critique of the opacityof social exhibitionism when it avoids unremark-able spaces for the more satisfying images of docu-mentary literalism.

Ractliffe’s other works are of this nature. Theyare generally committed to analyzing the unseen,yet without sacrificing her full engagement withrepresenting the subject. Many years of observingher work have revealed her habits of working,which invariably involve both procrastination andslowness. Her method shows that she privilegesrudimentary equipment such as toy cameras, oftendisassembled to create palimpsests, overlappingimages that have no fixed framing or pictorial pa-rameters, over more technically sophisticatedmechanisms. She uses the unfixed state into whichshe has engineered her equipment to proposeopen-ended, deeply contingent images, a quality ofcritical analysis that is fundamental to her photo-graphic process of slow accretion. Because the im-ages have no framing device, many of herphotographs take on visual qualities that are akinto techniques of mapping, panning, and surveil-lance. These result in images that appear as contin-uous strips of film and individual frames in whichthe temporal and spatial relationships between theimages are consciously collapsed.

If, over the last two decades, Ractliffe focused agreat deal of her analytical powers on formulatinga photographic antidote to documentary literal-ism—through the overlapping of images providedby the Diana, Holga, or similar cameras, or throughthe blurring of spatial and temporal frames pro-duced by the camera—the foundational images ofher career actually began, as described earlier, withsingle frames. In the early work, human presencealluded to destruction or ecological devastation,

Nka•87

characteristics, the South African landscape andurban spaces are infinitely photographable. Theyare quintessentially camera-ready spaces that con-sistently produce spectacular images. The country’sartists and writers are obsessed with the imagery.Such imagery of South Africa tends to fix on theexcess of the seen, as confirmation of the camera’sability to reveal, expose, and deliver a judgment onthe spatial mechanisms and visualizing systemsthat give rise to the excesses and distortions of thecolonial baroque. To its artists and writers, theSouth African landscape is akin to a corpulent bodyto be exploited. This infatuation with the landscapeas “exhibit A” has served as pictorial fodder for theexcess of the seen, what the South African writerand critic Njabulo Ndebele has derided as social ex-hibitionism. Landscape and space—like the starksymbols of racial identity, be it in politics, art, liter-ature, or journalism—is an inexhaustible leitmotifin South African representation and the ultimateaesthetic cri de coeur; a means of leveraging criti-cal credibility against the opacity of any aestheticasceticism and visual inhibition.

Ractliffe’s work has carefully avoided modes ofsocial exhibitionism that exalt the binaries of goodand bad, black and white, oppressor and oppressed,native and settler. Throughout her work she hasdeveloped a practice of rigorous asceticism, a way

of working that questions the camera-ready typolo-gies that have been the most visible images ofSouth Africa’s complicated landscape. We cannot,however, read her images reductively as a repudia-tion of the facts to be found on the ground, asituation that other images exploit, but as a subtlecritique of documentary literalism. Her choice ofsubject matter and her approach to photographingher surroundings is predicated on unraveling andrevealing those qualities of space and habitationthat are generally left unaccounted for or unre-marked upon, psychic disruptions that accompanythe documentation of absence; of what is not there,missing, erased: in short, the inadequacy of picto-rial certainty. An exemplary work in this regardis Vlakplaas: 2 June 1999 (drive-by shooting), asequence of photographic images and accom-panying video initially photographed with a dis-assembled plastic toy Holga camera similar to theDiana. Because of what the site represents, themanner in which Ractliffe depicts this site clearlyencapsulates her conscious deviation from docu-mentary literalism.

Driving around the perimeter of the farm, shephotographed the edges of the property, butavoided direct documentary depiction of the farm-house as evidence. Rather, she focused on the im-mensity of the silence around the property, thus

Journal of Contemporary African Art86•Nka

Vissershok, 1988 (diptych).

4_enwezor:nka_book_size 2/28/10 6:20 PM Page 86

Nka•89Journal of Contemporary African Art88•Nka

Vlakplaas: 2 June 1999 (drive-by shooting), 1999. Pigment print, 40 x 230 cm.

4_enwezor:nka_book_size 2/28/10 6:20 PM Page 88

is exemplary of Ractliffe’s approach: to show thesubject of an image, but only in increments or as acomposite of a larger complex of related images,objects, and meanings, rather than as one over-whelming, conclusive image fixed as one meaning.This photograph is part of a continuous explorationof urban forms, landscapes, street scenes, andprocesses of anomie in which she captures attrib-utes of spatial deformation that address differentconceptions of African urbanity.

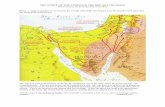

In 2007, twenty years after reading Kapuś-ciński’s stunning book and his description of Lu-anda; five years after the thirty-year civil war thatravaged and depopulated Angola, after thearmistice between the government and the rebelforces of UNITA ended the war upon the death ofits leader Jonas Savimbi, Ractliffe finally made herway to Luanda, to a city which, until her arrival,had remained a myth in her imagination. TerrenoOcupado, a large group of black-and-white photo-graphs, was shot in Luanda: from Porto Quipirileading to Caxito along the route to the city, to thesurrounding townships, the tented settlement ofNas Tendas, markets such as Roque Santeiro, theport bay at Ilha (a sliver of land extending into thebay of Luanda, farther up on the coast is Boa Vista),and assorted landmarks. Among the formal colo-nial architecture—most of them in various states ofdisrepair or refurbishment—are the derelict open-air cinemas with grand names like Esplanada Mira-mar; the refurbished Museu de Historia Natural,first opened in 1938, and shut down by the waruntil it was reopened in 2002; the colonial architec-ture of the Banco Nacional de Angola lined withtiled murals depicting various scenes of the Por-tuguese presence in and colonization of Angola;and Forteleza de São Miguel, the old fort of the citybuilt in 1576, when Luanda was founded, almost acentury after the Portuguese landed in Angola in1483. These images of the city, while fascinating,are the least dramatic of the images that form Ter-reno Ocupado.

In this project, completed in late 2007, Ractliffereveals in Luanda’s teeming shantytowns—despitethe precarious state of urban infrastructure and se-rious deficits in social amenities—a sense of hu-manism in the city’s locations, a far cry from thefamiliar spatial givens of South Africa’s intractable

urban instability. Yet the view of Luanda is not atall sentimental, for inasmuch as the images exca-vate—with unremitting empathy and directness—modes of urban sovereignty of the inhabitants, theimages do not retreat from the vestigial harshnessthat mark the shantytowns as urgent zones of offi-cial neglect. She offers us a view that represents partreality and part mythology. As Ractliffe writes inher introduction, when she arrived she “entered themyth,”4 alluding both to the story of Kapuścińskiand to the history of cold-war politics that madeAngola—from the 1960s to the 1980s—a center ofideological competition between South Africa andthe United States, supporting the anticommunistUNITA and FLNA respectively, on one side, andthe Soviet Union and Cuba supporting MPLA onthe other. The inhabitants of the vast shantytownsare part of the history of this competition. In fact,many—if not most—of them are double refugees,displaced by both ideological and colonial wars.

Over the last decade, images like these, whichreflect African spatial conditions as a series of in-tractable urban anachronisms—a condition whichthe Dutch architect and theorist Rem Koolhaas seespositively as the fate of cities of the future, andwhich the Ghanaian/British architect David Ad-jaye, in his ongoing photographic studies of Africancities and urbanism, contests—have been objectsof critique as participating in forms of Afro pes-simism; a situation whose effect of extreme impov-erishment may lead some to devalue the inherenthuman qualities of African cities. The question thatdemands to be answered is how Ractliffe’s photo-graphic analysis departs from the urban mytholo-gies and clichés of African and “Third World”cities. She does confess to her own evident discom-fort at photographing in such a setting, if only be-cause, as a white outsider, her motivations may bequestioned, and the resulting images she has pro-duced may provoke accusations of taking part inan ethnographic exercise and documentary literal-ism. But Ractliffe is an artist who not only thinkscarefully about conditions in which her images areproduced but also presents her work in such a waythat the images reflect that thinking, and activelyinvolves the viewer in the act of thinking throughthe situations depicted in the images.

The first image in Terreno Ocupado sets the crit-

Nka•91Journal of Contemporary African Art90•Nka

while animals became mythical symbols of wild-ness, menace, and freedom. Yet, in her inimitableway, Ractliffe also gives us animal metaphorswhose images can be observed as reflecting boththe wretched state of the animals themselves—dogsin this case—and the vestigial intimation of theiruntamed nature. Dogs in a way became themetaphor for exposing what were essentially thedog days of the repressive state, of life underapartheid. In one of these early photographs (part

of Vissershok) Ractliffe takes the most emblematicof subjects—a landscape choked with refuse which,taken at face value, is often used to represent thedystopian quality of African urban space—and in-stead transforms it into an image of improbable po-etry, of agitated motion, as white birds in flightbuzz like flecks of confetti above the dematerializeddetritus atop which stand a group of figures, and atruck just off the edge to the left, and a line of elec-tric pylons framing the distant horizon. This image

Vissershok, 1988.

4_enwezor:nka_book_size 2/28/10 6:20 PM Page 90

Nka•93Journal of Contemporary African Art92•Nka

View over Boa Vista towards the city (diptych), 2007.

4_enwezor:nka_book_size 2/28/10 6:20 PM Page 92

ical context and blunts any suggestion of ethno-graphic liberties being taken or documentary liter-alism being indulged. Photographed throughoutand printed in dusky black and white, the establish-ing shot is an image of a landscape covered in dry,wiry grass, the kind that appears just as the land isabout to lie fallow. In the immediate foreground ofthe image, bristly strands of the grass spread out oneither side of the image against the backdrop of asteel-gray sky. To the left of the image, a sharp sliverof white, partially concealed by the spreading grass,reveals what looks like a drying-out stream or patchof sand, but in fact, is a lagoon. In the middleground is a structure that focuses the image of thelandscape and defines its active condition. Thestructure, a billboard, stands on ground that slopesslightly upward, so that it could be read as one ap-proaches it. Written in Portuguese in thick, peelingblack lettering is the phrase: “Terreno Ocupado.” Arough translation of this text from the Portuguesewould read “occupied land.” Not only does thisphrase lay down the context within which thisgroup of photographs can be understood, it definesthe means by which we can read the entire series aspart of the analysis of space, territory, boundaries,and power. In other words, this is in fact a placethat is actively occupied, rather than a ruined orabandoned landscape.

Terreno Ocupado reflects part of the struggle forspace familiar in places where the landless are ag-gressively seeking rights to take possession of land.The land they seek to own is either being aban-doned or is the subject of speculative developmentthat often displaces large populations once their in-formal settlements are rezoned for luxury seasidedwellings. The vast shantytown of Boa Vista, for ex-ample, perched on a majestic cliff (half eaten awayby erosion, revealing a yawning abyss spewingsmoke from below) overlooking the harbor and thesea, is not only a place coveted by developers andtheir government allies but also a context of newurban politics. The residents of Boa Vista and themerchants in the city’s sprawling market RoqueSanteiro (another coveted urban property) have be-

come embroiled in new debates reshaping theurban forms of African cities, fighting displace-ment and forcible relocation to areas outside thecity. Ractliffe’s images are invested in the fascinat-ing urban iconography of spaces like Boa Vista, aneighborhood constructed on a topography of suchextreme precariousness that one wonders how thestructures remain fixed in place on that erodingground, and marvels at the human qualities theycontain. In a way, these images of Luanda are unlikeanything Ractliffe has ever attempted, given herproclivities toward the inadvertent and her reluc-tance to engage in full disclosure. She is however,unflinching in rendering these scenes of urbandecay. She shows us, without any sense of moraljudgment, areas of structural instability: housescobbled together out of nothing more than card-board, cloth, and corrugated sheets of zinc; shackssitting in smoldering pits of oily miasma, orperched on the edge of vertiginous precipices;houses in gullies threatened by the next mudslideor surrounded by a ramble of other dwellings look-ing out to the sea below and the hazy horizon. De-spite the extremeness of these scenes, a surprisingquality of Ractliffe’s point of view of Luanda’s urbanspaces, between its modern seaside high rises, mudarchitecture, unpaved roads, and grand colonnadedbank interiors is her avoidance of documentary lit-eralism. Here the field suddenly vibrates withhuman presences, showing the landscape as a zoneof active civic, economic, cultural, and politicalprocesses.

In an urban context in which the poor and thedispossessed seemingly have neither claims norrights to land, these powerful images finally untiethemselves from the dramatic description of Ka-puściński’s dying city, revealing a series of complexsocial and urban problematics that bind the poorand the wealthy alike to a struggle between landand sea, tenancy and power. The social and politi-cal ramifications of this debate, which are in ampledisplay in the rest of the series, might also prove tobe an oblique way for Ractliffe to reflect on thesearing debate surrounding land and the landlessin Southern Africa, from South Africa to Zim-babwe.

In this sense, Terreno Ocupado, both as animage and a phrase, is a terrific way of seeing, a way

of piercing through the thick, smoky fog thatchokes the low sky overhanging the bustling shan-tytowns and their depopulated surroundings, fromCrossroads to Vissershok, from the desolation andpessimism of Nadir to the active struggle unfold-ing in the blighted topography of Boa Vista, fromthe wreck of the capsized Chinese ship rusting atthe dock in Ilha to the forgotten small towns lost inthe vastness of the Great Karoo. Ractliffe has pho-tographed these disparate social realities with pen-etrating insight and visual austerity, sometimesemploying them as allegorical entities, at others aspart of the wild rumors of existence. But never hasher work adopted the simplifying edicts of docu-mentary literalism nor ever indulged in the excessof the seen that often mars the images of social ex-hibitionism. Terreno Ocupado sits precariously be-tween the skepticism of Koolhaas’s idea of cities likeLagos or Luanda as the paradigms of cities to come,or it might foretell yet another urban reality de-scribed by the American social commentator MikeDavis as the “planet of slums.”5 Either way, Luandawill not be a dying city any time soon, even whenthe dogs join the exodus of fleeing soldiers; on theopposite side of the road, the returnees are makingtheir way back into the heart of the city.

NotesThis essay was first published in Jo Ractliffe, Terreno Ocupado(Johannesburg: Warren Siebrits Modern & Contemporary Art,2008).1 See Jacques Rancierre, The Future of the Image (London andNew York: Verso Press, 2007).2 See Achille Mbembe, “Necropolitics” in Public Culture 15,no. (Winter 2003): pp. 11–40. Available online at:http://www.jhfc.duke.edu/icuss/pdfs/Mbembe.pdf or:http://www.rhul.ac.uk/research/harc/Events/necropolitics-mbembe.pdf.3 Robert Frank, The Americans (Paris: Delpire Press, 1958.Reprint, Steidl / National Gallery of Art, 2008; available in bothChinese and German editions).4 See Jo Ractliffe, “Introduction” in Terreno Ocupado.5 See Mike Davis, Planet of Slums (London and New York:Verso Press, 2006).

Nka•95Journal of Contemporary African Art94•Nka

(Top): Women minding pigs, Roque Santeiro market, 2007.(Middle): Tethered goats, Roque Santeiro market, 2007.(Bottom): Drying fish on the beach at Ilha, 2007.

4_enwezor:nka_book_size 2/28/10 6:20 PM Page 94