Examining African American and Caucasian 2 … › ejournals › JOTS › v35 › v35n2 › pdf ›...

Transcript of Examining African American and Caucasian 2 … › ejournals › JOTS › v35 › v35n2 › pdf ›...

Th

eJ

ou

rna

lo

fTe

ch

no

log

yS

tud

ies

2

Examining African American and CaucasianInteraction Patterns Within Computer-MediatedCommunication EnvironmentsAl Bellamy and M. C. Greenfield

AbstractThis study explored the extent to which stu-

dent emotion management factors and normativeorientation (belief that chat rooms have normativestandards of conduct similar to face-to-face inter-action) circumscribe the sending of hostile mes-sages within electronic relay chat rooms on theInternet. A questionnaire survey collected datafrom 114 undergraduate and graduate studentsfrom a large university in southeastern Michigan.The results of the survey revealed statistically significant differences between African Americanand Caucasian chat room users in terms of howthe emotion management factors of shame, guilt,and embarrassment affect communication. Thenormative orientation of the chat room users wasshown to have an inverse relationship regardingthe flaming messages between both ethnicgroups. This article describes how these factorsare influenced by gender and ethnicity/gender.Findings regarding the perceptions of racismwithin electronic chat rooms are also discussed.

IntroductionThe utilization of information technology,

such as the Internet and its ancillaries,- includ-ing the World Wide Web, is increasingly becom-ing an icon symbolizing economic and socialwell being, technological literacy, and employa-bility in the information age. Its implications forsocial and political transformation and liberationhave been clearly identified in the media andacademia. Due to the cue less structure of theInternet, many have predicted that it would be amechanism to ameliorate the social inequalitiescommonly associated with race, gender, physicalhandicaps, and social class (Connolly, Jessup, &Valacich, 1990; Sproull & Kiesler, 1986,Wasserman & Richmond-Abbott, 2005).

With the exception of studies that cite thestatistical disparity between African Americansand Caucasians in Internet utilization (NielsenMedia Research, 1997; Novak, Hoffman, &Venkatesh, 1997) few researchers have system-atically examined the ways in which ethnicityinfluences behavioral differences found incyberspace. Given the saliency that has beenrecently attached to Internet accessibility amongthe Black population (Clinton, 1997), there

seems to be a parallel need for research thatexplores social psychological dynamics occur-ring within the inchoate and amorphous struc-ture of computer-mediated communication environments. This type of research is expectedto provide a broader perspective of Internetbehavior than the previous descriptive studies of Internet utilization.

Purpose of ArticleIn this article, the authors discuss findings

pertaining to the ways in which Blacks andWhites differ in perceptions and communicationbehaviors as they participate in Relay ChatRooms (RCR). A RCR includes a group of people and mass communication technologyin which users send and receive text-based messages. The time delay of these computer-mediated messages can be nearly instantaneousor a “real- time” text interchange (Walther, etal., 1994; December, 1996). In comparison tostudies that merely describe Internet utilization,this study’s goal is to explain the variancesfound among Blacks and Whites for these vari-ables, utilizing social psychological frameworksas a conceptual guideline. The researchers willprimarily examine communication differencesbetween Blacks and Whites with focused atten-tion given to the sending of “flaming” messagesin relay chat rooms.

Flaming is a term that refers to the sendingof hostile messages (Lee, 2005; Orton-Johnson,2007). The absence of informational cues per-taining to one’s identity within the chat roomenvironment has prompted many authors toallege that the Internet fosters a social context in which conventional normative standards thattypically circumscribe behavior found in face-to-face interactions has been relaxed (Kiesler,Siegel & McGuire, 1984). It has been furtheralleged that the suppression of normative stan-dards of conduct will create a social conditionwhere individuals feel free to engage in antiso-cial communications such as flaming, sendinghostile messages, and expressing anger.

Very little research has been done on theinfluence that social psychological factors haveon flaming behavior and the moderating

influence that ethnicity and gender may have onthis relationship within the “cues-filtered-out”(Culnan & Markus, 1987) context of electronicchat rooms. More specifically, given that flam-ing and other hostile-type behaviors do indeedoccur in computer-mediated communications(CMC), s we explore the following generalresearch questions:

1. To what extent do differences in commu-nication behaviors (such as sending hos-tile messages and expressing anger) existbetween Blacks and White RCR users,and what are the differences by genderwithin and between each of thesegroups?

2. In what ways do social psychologicalfactors (such as emotions) affect CMCcommunications and to what extent isthis relationship moderated by ethnicityand gender?

Theoretical Framework of PaperThe principal conceptual scheme of this

paper is symbolic interaction (SI). Symbolicinteraction is a social psychological approach(within sociology) to studying the ways in whichhumans create and use symbols in formulatingsocial organization (Blumer, 1969; Goffman,1959; Mead, 1934). Central to this frameworkare the following concepts:

1. Interaction – “Symbolic interactionismconcentrates on the interactive processesby which humans form social relation-ships” (Turner, 1998, p. 364). Mostimportant, interaction is delineated asthe focal point for analyzing the natureof social organization.

2. Taking the Role of the Other – is aninteraction process by which the individ-ual’s perception of self is obtainedthrough interpreting the expectations ofothers in a given social situation. Theself, then, is defined as a social self,which could consist of a specific otheror a generalized other, which consists ofa broader community of attitudes such asone’s culture. Successful interpretationamong “actors” in a given situation iswhat enables communication to takeplace. An emergent “pattern” of suchcommunication is what imparts a sem-blance of “structure” to the interaction.

Thus, the focal point of analyses here isrole behavior (Stryker, 1987).

3. Definition of the Situation – pertains tothe covert cognitive process of determin-ing the nature of a particular social situ-ation in terms of its role expectationsand normative standards. By mentallydefining the situation, the individuals areable to present themselves in “sociallyacceptable” ways (Goffman, 1959). Thecognitive landscape of the situation isinfluenced by the symbols contained inboth the situation itself and the culturallyderived mental pictures that the personhas internalized.

4. Mind – is a concept that represents theinternalization of the structure andprocesses of the factors described previ-ously. Within this context, mind is theepistemological expression of form andprocess. However, the mind as describedhere is not a static construct as referredto in various psychoanalytical frame-works. Rather it is an entity that isdynamically homeostatic with emergentsocial processes. As such, the study ofindividual identity takes the form of ana-lyzing the ways in which the self simul-taneously maintains and creates itself invarying situational contexts.

This conceptual framework was selected forthis article because its core tenets appear to be aheuristic guideline for analyzing ethnic and gen-der behavioral differences on the Internet whosepeculiar cultural differences are expected toreflect differences in role-taking and situation-defining processes. Frameworks similar to theinteractionist approach that are used to examinebehavioral processes within the CMC contextconsist of sociocognitive theory Walther et al.,1982; (Kern & Warschauer, 2000; LaRose,2001) and sociocultural theory (Block, 2003;Brignall & Van Valey, 2005). Furthermore, thetheory’s propositions concerning the dynamicinterrelation between structure and mind alludeto the idea that these processes may have a dif-ferent epistemology within cyberspace as com-pared to face-to-face communication platforms.

Relay chat rooms on the Internet represent avery distinct type of situation to analyze com-munications because of the absence of symbolsthat characterize traditional face-to-face

Th

eJ

ou

rna

lo

fTe

ch

no

log

yS

tud

ies

3

Th

eJ

ou

rna

lo

fTe

ch

no

log

yS

tud

ies

4

communication. Subsequently, some authorshave predicted that communication in cyber-space would reduce differences in cultural (i.e.,ethnicity and gender) communication styles(Connolly, Jessup, & Valacich, 1990). However,symbolic interaction theorists would argue thatpeople do not leave their culture at home whenfaced with new situations, such as CMC. Rather,they define novel situations according to cultur-ally learned definitions of the situation (Blumer,1969; Shott, 1979). SI proponents would pro-pose that individuals have covert conversationswith “self ” as they define the CMC interactionepisodes. If this is the case, differences in com-munication patterns are expected both betweenAfrican Americans and Caucasians and accord-ing to gender, because each group has its ownunique cultural orientation that creates differ-ences in how its members define situations.

Examining whether African Americans andCaucasians differ on such things as flamingbehavior will indicate whether or not CMC isreducing cultural differences in interactionbehavior. Using the symbolic interaction con-ceptual framework, these researchers will seekto explore if African Americans and Caucasiansdefine the CMC environment in different waysand to determine if any such differences lead todifferent tendencies in interactive behavior. It isa well-documented idea that African Americansand Caucasians differ in cultural orientations.These differences are conceptualized within thisarticle to refer to differences in the ways eachgroup may define the cyberspace situation.

The Sociology of EmotionThe sociology of emotion (Heise, 1977;

Hochschild, 1979; Kemper, 1991; Ridgeway,1982; Hochschild, 1992; Shott, 1979; Stryker,1987; Turner, 1994) is a symbolic interactionapproach which postulates that emotions influ-ence the interaction process. Emotions are attested to as sociologically relevant phenomenabecause particular types of emotions asexpressed toward others are moderated bysituational and normative constraints. Moreimportant, emotions are considered as factorsthat circumscribe various types of behaviorswithin the context of particular social situations.Emotions will be framed in this article as emotion management factors. This framework is particularly relevant to the present study giventhe attention to the management of emotionswithin the context of emotional intelligence(Salovey & Mayer, 1990).

In order to operationalize the concept ofemotion management, the emotive theory ofShott (1979), which delineates specific emotiontypes, will be drawn upon. Taking the role of theother is the focal point in Shott’s emotion man-agement schema. “Much role-taking is reflexivein that the individual has an internal conversa-tion with self as an object, seen and evaluatedfrom the perspective of specific and generalizedothers. In this evaluation process, emotions arearoused and labeled; and if these emotions arenegative, they mobilize the individual to adjustbehavior” (Turner, 1994. p20). Shott (1979)delineates six emotion management factors:guilt, shame, embarrassment, empathy, vanity,and pride. Of these, the first three appear to berelevant to the present discussion, and brief definitions follow:

1. Guilt – Guilt is a feeling that emergeswhen a person acknowledges that her/hisbehavior is incongruent with the norma-tive and moral standards within a specif-ic social situation.

2. Shame – Relates to an individual’s judg-ment of self relative to situational expec-tations (Ausubel, 1955). Shame occurswhen after taking the role of the other,the person learns that the other’s percep-tion of the behavior is not congruent toher/his idealized image of self.

3. Embarrassment – Is a feeling that exists“when an individual’s presentation of asituational identity is seen by the personand others as inept” (Turner, 1998).

Each of these variables, which are referredto as emotion management factors, will be testedin terms of the degree to which they influenceflaming behaviors among African American andCaucasian relay chat room users and amongmales and females. A negative correlationbetween these factors and the interaction vari-ables would indicate that they do indeed circum-scribe antisocial behavior within chat rooms.This is the expected relationship between thesevariables.

MethodologyParticipants

Data for this study was collected from 114undergraduate and graduate students in a rela-tively large university in southeast Michigan.The undergraduate students were enrolled in a

technology and society-type class, which satis-fies a basic studies requirement at the university.Subsequently, the sample population representsa wide spectrum of undergraduate degree pro-grams and career orientations within the univer-sity. This improves upon the generalizability ofthe sample (for the university population).

A full sample was taken among studentswho identified themselves as chat room users(for both undergraduate and graduate students).The graduate students were enrolled in an inter-disciplinary technology program. Each studentcompleted a 104-item questionnaire (duringclass time) that measured a variety of Internetand chat room utilization factors. (There weretwo Asian respondents and one Hispanic respon-dent in this survey. They are not included in thepresent analyses).

Instruments criterion factors.

The dependent variables within this paperpertain to the sending of antisocial messages inchat rooms (interaction). Each variable and itsmeasurement are as follows:

Flaming. “I send flaming (hostile) messages.”

The tendency for sending hostile mes-sages while in chat rooms as compared toface-to-face communications: “I am morelikely to send hostile messages in chat roomsthan in face-to-face communications” (This variable will be referred to as “Hostility” withinthe statistical analyses).

Perception of displaying anger in chatrooms. “It is more appropriate to display angerin chat rooms than in face-to-face communica-tion” (Will be referred to as “Anger”).

Independent Variables:

Cybernorm. “I believe that there is anunwritten code of conduct that people must fol-low in chat rooms.”

Shott’s emotion management factors.

Guilt - “I feel guilty if I say something tooffend someone in a chat room.”

Shame - “I feel a sense of shame whensomeone in a chat room points out to me thatmy messages are inappropriate.”

Embarrassment - “There have been timesthat I have felt embarrassed in a chat roombecause of how I presented myself.”

Moderator factors.

A moderator variable is a categorical factorthat is examined to determine the influence that ithas on the relationship between the independentand criterion factors. In this article, we attemptto determine if the correlations between theemotion management factors, cybernorm, and

the communication variables are altered withincategories of user’s ethnicity, gender, and ethnicity/gender.

Ethnicity – African American andCaucasian sample populations.

Gender/ethnicity – African American male,female and Caucasian male, female categories(ethnicity and gender ethnicity are also used asindependent factors).

Statistical ProceduresThe statistical procedures for analyzing the

data are mean comparisons and Pearson correla-tion. The Statistical Package for the SocialSciences (SPSS) was the statistical softwareused for this analysis.

ResultsMean Comparisons of Interaction Variables byEthnicity and Gender/Ethnicity

Table 1 illustrates mean differences in thecommunication variables found between ethnicand gender groups, and ethnicity/gender. Verylittle difference was revealed between African

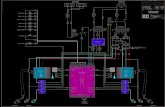

Demographic Structure of Study

Ethnicity Gender Ethnicity/Gender College LevelB W M F BM BF WM WF F S J S Gr

36 73 64 45 18 18 46 27 37 35 20 14 3

Chart 1. The following chart presents an overview of the demographic characteristics of the sample:

Th

eJ

ou

rna

lo

fTe

ch

no

log

yS

tud

ies

5

Th

eJ

ou

rna

lo

fTe

ch

no

log

yS

tud

ies

6

Americans and Caucasians according to theirpropensity for sending hostile messages in chatrooms. The most significant differences appearamong gender and ethnicity/gender categories.To begin with, males are more prone to sendflaming messages than are females (p = .006).This finding holds true within each category ofethnicity for the Caucasian male/female compar-ison (p = .07) and the African Americanmale/female comparison (p = .01). There is alsoa slightly higher difference between the AfricanAmerican male/female comparison (.95) thanthe Caucasian male/female comparison (.63).African American males show the highest meanon flaming among all of the groups.

Very little difference is shown among eachof the groups for the hostility variable. However,

once again, the data indicates a larger mean difference between African American males andfemales (.32) than between Caucasian males andfemales (.06), and African American males showthe highest mean on this variable. Neither differ-ence, however, revealed statistical significance(p = .88 and .46, respectively).

For the anger variable, very little differenceis shown according to ethnicity or gender, butthere are larger differences shown byethnicity/gender. Also, the direction of the differences was different for each ethnicity/gender category. Among Caucasian RCR users,females have a higher mean value than domales. The opposite is true for the AfricanAmerican users, where males have a higher

mean value on anger than do females. Further,the African American male/female difference issignificant at the .05 level, whereas theCaucasian male/female does not reveal signifi-cance (p = .26).

Differences on whether or not RCR usersbelieve that there are norms of conduct operativein chat rooms are shown within and between eachof the groups. None of these differences, howev-er, were found to be statistically significant.

The next tasks were to determine the extentto which the variances in chat room behaviorcan be explained by the social psychologicalfactors of cybernorms and emotion managementfactors and then to ascertain the moderatoreffect of ethnicity on these relationships.

Correlation Analyses for Cybernorms andInteraction Variables

Table 2 presents the correlations betweencybernorm and the interaction variables by ethnicity and ethnicity/gender. For the entiresample, cybernorm is significantly correlatedwith only the flaming variable, and the negativesign indicates that it operates as a constrainingfactor to sending flaming messages in chatrooms.

The same finding is found within each ofthe ethnicity and gender categories. Cybernormis more strongly correlated with sending flamingmessages for males than females, and forCaucasian males in particular. Stronger correla-tions are shown for Caucasians, both male and

Table 1. Mean Comparisons of Interaction Variables by Ethnicity, Gender, andEthnicity/Gender

female, than for African Americans on the flaming variable.

Relatively weak correlations are foundbetween cybernorm and the hostility variableamong all of the categories. The only strong correlation (in the expected negative direction)between cybernorm and anger is revealedamong African American females.

Based upon the moderately strong inverserelationships between cybernorm and flaming,the viewpoint that one’s definition of the situa-tion affects behavior is confirmed, and it is con-firmed in the expected direction.

Analyzing the Impact of Emotion Management

on RCR Behavior

In attempting to present oneself in an appro-priate manner during face-to-face encounters, aperson’s concern for not feeling guilty, not beingashamed, or not being embarrassed are seen as

factors that would circumvent the sending ofantisocial behaviors, such as flaming. This hasbeen the commonplace proposition relative toface-to-face communication situations (Goffman,1974). Our concern here is to test whether thisproposition holds true for electronic communica-tion platforms.

The weak correlations shown in Table 3between the emotion management factors andinteraction variables for the population as awhole, does not support this proposition in relation to relay chat room environments.However, in examining the moderator influenceof ethnicity upon these relationships, a differentand interesting finding is revealed. As shown inTable 4, there are moderate correlations betweentwo of the emotion management factors (guilt

and shame) and the flaming variable forCaucasian RCR users, and although the correlation between flaming and embarrassmentis small, it is nevertheless in the anticipated

Table 2. Correlations between Cybernorm and Interaction Variables for EntireSample, and by Ethnicity, Gender, and Ethnicity/Gender

CybernormCybernorm

Table 3. Zero Order Correlations between The Interaction and EmotionManagement Variables

*p < .05

*p < .05**p < .01

Th

eJ

ou

rna

lo

fTe

ch

no

log

yS

tud

ies

7

Th

eJ

ou

rna

lo

fTe

ch

no

log

yS

tud

ies

8

inverse direction. This indicates that these factorsdo indeed operate as emotion management fac-tors within computer-mediated communicationenvironments, but only among the Caucasianusers for this sample. Table 5 shows that thispattern is maintained among both Caucasianmales and females, although stronger correla-tions are revealed among Caucasian females.

Comparatively, each of the correlations forthe same variables among African American(Table 6) users is positive, indicating that theemotion factors operate as interactive, ratherthan as suppressive factors. Furthermore, theseare moderately strong correlations when com-pared to those found within the Caucasian popu-lation sample.

Table 4. Zero-order Correlations between Emotion Management and InteractionVariables within Ethnicity Categories

Table 5. Correlations between Interaction and Emotion Management Variablesby Caucasian Male and Female Categories

*p < .05**p < .01

*p < .05**p < .01

This is a very surprising, yet interestingfinding. These extreme statistical differencesimplicate that African Americans andCaucasians are defining the CMC situation indifferent ways. A possible explanation of thisfinding as it relates to symbolic interaction theo-ry is that each group engages in different roletaking and cognitive rehearsal processes, whichare affected by the unique cultural experiencesof the two groups.

More specifically, African Americans, whohave historically experienced more prejudice insocial encounters than Caucasians, (with otherCaucasians) may be putting more emphasis onchat rooms as a “liberator” of traditional socialinequities Kiecolt, 1997). Electronic communi-cations suppress identity traits, such as race,enabling a person to fully participate in the communication act, not as an African Americanperson per se, but as the individual or role thatthe user perceives is the represented group.Subsequently, when African American users aretaking the role of the other within this electroniccontext, they may be taking the role of theCaucasian participants from an assumedCaucasian role, as compared to an AfricanAmerican role as would be more likely the casein an face-to-face (FTF ) situation. The questionto be raised in this instance would be the follow-ing: How does an African American person performing a Caucasian role define both the

chat room situation and the expectations of theassumed Caucasian role from the perspective of other Caucasian roles?

Given that the acting out of this assumedrole does not contain the complete genome ofthe Caucasian culture, there is a real likelihoodthat some perceptions would be erroneous,thereby causing behavior that is not isomorphicto that group’s actual chat room expectations. Inshort, African American users, in comparison toCaucasian participants, may be defining the chatroom situation as an appropriate place forexpressing hostile feelings, such as flaming. Forexample, “it is something that Caucasian peopledo, I am in a Caucasian environment, and there-fore, I should behave (role acting) accordingly.”Furthermore, they also may conceptualize theCaucasian role as one that has this expectation,where in essence this may not be the case. Thisidea appears to be supported by the higher meanscores on the cybernorm variable amongCaucasians in comparison to that of AfricanAmericans, which was reported previously inthis article. The lower correlations betweencybernorm and the interaction variables amongAfrican Americans in comparison to Caucasiansdescribed previously also give support to thisproposition. The positive direction of the corre-lations is maintained for both African Americanmales and females. However, these positive cor-relations are much stronger for African

Table 6. Correlations between Interaction and Emotion Management Variablesby African American Male and Female Categories

N = 36

Interaction Variables

Flaming Hostility Anger

Ethnicity/Gender (African American)

N = 18 n = 18 n = 18 n = 18 n = 18 n = 1 8 Male Female Male Female Male FemaleEmotionManagement

Guilt .180 .472 -.255 .723** .021 -.043

Shame -.027 .700 .023 .379 -079 -.166

Embar. .189 .510 -.482* .092 -.143 -.183

*p < .05**p < .01

Th

eJ

ou

rna

lo

fTe

ch

no

log

yS

tud

ies

9

Th

eJ

ou

rna

lo

fTe

ch

no

log

yS

tud

ies

10

American females than for African Americanmales. This finding indicates that culturaldynamics are occurring that are peculiar to theAfrican American female culture.

Our attempt to explain this dubious findingfrom a symbolic interactionist perspective ismerely theoretical conjecture. We intend to con-duct further research on this particular CMCphenomenon.

DiscussionSeveral important social psychological con-

clusions can be drawn from this study. The firstis that the extent to which hostile type commu-nications is displayed in a virtual communica-tion environment is affected by the user’s nor-mative orientation. The perception that normsexist in relay chat rooms was shown to be a con-straining factor for sending hostile-type commu-nications in RCR among each of the categoriesof ethnicity and gender. This finding negatesrecent claims that characterize electronic com-munications as relatively normless. The resultsof this investigation suggest that individuals takewith them culturally learned symbols of conductto situations, including emerging social systems,such as those found on the Internet that have notyet reached organizational homeostasis. From ahistorical perspective, electronic communica-tions such as relay chat rooms, because of theirfaceless architecture, are expected to make revo-lutionary changes in social organization at thesocietal level. Although this may indeed be true,this study clearly indicates that such changeswill not be completely divorced of traditionalmental categories of social order. These conven-tional categories of images and thought willserve as a mental map for traversing the land-scape of the new cyberculture. This means thatsymbolic categories of conventional racism andsexism will also be copied and pasted within theso-called new social structure along with norma-tive standards of conduct.

Second, although cybernorms were shownto influence CMC behavior, the degree of itsaffect varies according to ethnic and gendergroupings, which reflect differences in culturalorientation within these groups. Such variancesupports the notion that the relatively one-dimensional analyses of CMC dynamics that iscurrently commonplace should be replaced bymore systematic research strategies that attemptto explore how a larger number of factorscovaries in relation to explaining CMC

behavioral dynamics. Moreover, in the futureresearchers should continue to examine thewithin-group variance among AfricanAmericans, according to gender and other factors (Schuman et al., 1997; Carter, DeSole,Sicalides, Glass, & Tyler, 1997).

Along the same lines, the interesting find-ing that emotion management factors circum-scribe the sending of hostile RCR messagesamong Caucasian users and not those of AfricanAmericans raises some intriguing issues aboutidentity formulation (or reformulation) and com-puter-mediated communications. It is importantto consider the epistemological implications ofCMC interaction processes. The mind, as con-ceptualized within the symbolic interactionframework, is the energic outcome of the recur-sive interfacing of form and process (socialstructure). That is to say, a person becomes whathe/she does (interactions). These interactions,when developed as a pattern, become the struc-ture or condition that gives direction to the indi-vidual. Most important, from the perspective ofidentity development, the person internalizesthis structure, and this internalized perception ofsocial reality becomes the basis of that person’smind or consciousness. The format of virtualcommunication enables users to more freelydefine their symbolic context, and this will sub-sequently allow people to present themselves invarious ways (; Tanis & Postmes, 2007; Tynes,2007).

We believe that the drastic differencesbetween African Americans and Caucasians onthe emotion management factors allude to theidea that chat rooms are serving different episte-mological purposes for the two groups. Thisidea is supported by a study by Weiser (2001)that revealed that processes such as flaming aredriven by social psychological factors pertainingto the needs that the Internet serves for theusers.

From a practical standpoint, it may meanthat such recent psychological phenomena, suchas Internet addiction should be approached bypsychological practitioners with the” personalepistemology” of the client in mind. Althoughthe design of this research project does notdelineate the particular aspects of such an epis-temological model, the profound differences thatAfrican Americans and Caucasians revealed forthe emotion management factors in this studysuggest that ethnicity would be a valuable

starting point or a component for its develop-ment. As the diversity within the data amongethnic and gender categories points out, authorsmust be careful not to reify CMC technologywith deterministic powers as espoused in theconstructivist perspective inherent within previ-ous studies and theoretical postulations. Rather,the mind is a very dynamic construct, whereinthere is the potential for a lexicon of variants inconsciousness within the boundaries of cultural-ly derived symbols that can be created by theindividual. The individual here is not seen as areceptacle of social and cultural ideas, however,her or she is understood as an entity who has theability to define and redefine her/his situationalcontext (Savicki et al., 1998). CMC, particularlyas it pertains to African Americans, makes thisprocess a more viable possibility.

Finally, the results of this study should beconsidered a preliminary investigation into thedifferences between African American and

Caucasian CMC utilization. Future studies alongthese lines should be conducted with a differentand wider sampling population (i.e., non-colle-giate population) to determine the generalizabil-ity of the patterns shown among college studentsin this present study. Studies that strategicallyaddress the findings that relate to identity devel-opment among African American users shouldbe conducted to create a more comprehensiveunderstanding of this dynamic as it occurs with-in the context of electronic communication.

Dr. Al Bellamy is a professor of Technology

Management in the School of Technology

Studies at Eastern Michigan University,

Ypsilanti.

Mr. M. C. Greenfield is an professor of

Electrical Engineering Technology in the School

of Engineering Technology at Eastern Michigan

University, Ypsilanti

References

Ausubel, D. P. (1955). Relationships between shame and guilt in the socializing process.Psychological Review, 62(5), 378-390.

Block, D. (2003). The social turn in second language acquisition. Washington, DC: GeorgetownUniversity Press.

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Brignall, T. W., III, & Van Valey, T. (2005, May-June). The impact of internet communications onsocial interaction. Sociological Spectrum, 25(3) 335-348.

Carter, R. T., DeSole, L., Sicalides, E. I., Glass, K., & Tyler, F. B. (1997). African American racialidentity and psychosocial competence: A preliminary study. Journal of Afro-American Psychology,23(1), 58-73.

Clinton, W. J. (1997, February 4). [State of the Union Address]. Speech presented to a Joint Sessionof Congress, House of Representatives, Washington, DC. Retrieved from:http://www.whithouse.gov/WH/SOU97/

Connolly, T., Jessup, L. M., & Valacich, J. S. (1990). Effects of anonymity and evaluative tone on ideageneration in computer-mediated groups. Management Science, 36, 689-703.

Culnan, A. & Markus, M. L. (1987). Toward a critical mass theory of interactive media: Universalaccess, interdependence and diffusion. Communication Research, 14(5), 322-344.

Culnan, M. J., & Markus, M. L. (1987). Information technologies. In F. Jablin et al. (Eds.), Handbookof organizational communication: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 420-443). Newberry Park,CA: Sage Publications.

December, J. (1996). Internet communication. Journal of Communication, 46, 14-33.

Dubrovsky, V. J., Kiesler, S., & Sethna, B. N. (1991). The equalization phenomenon: Status effects incomputer-mediated and face-to-face decision-making groups. Human-Computer Interaction, 6,119-146.

Th

eJ

ou

rna

lo

fTe

ch

no

log

yS

tud

ies

11

Th

eJ

ou

rna

lo

fTe

ch

no

log

yS

tud

ies

12

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday Anchor.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis. New York: Harper Colophon.

Heise, D. (1977). Social action as the control of affect. Behavioral Science, 22, 163-177.

Hochschild, A. R. (1979). Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. American Journal ofSociology, 85(3), 551-575.

Hochshild, A. R. (1992). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feelings. In C. Clark &H. Robboy (Eds.), Social interaction: Readings in sociology (4th ed., pp. 136-149). New York, NY:St. Martins Press.

Kemper, T. (1991). Predicting emotions from social relations. Social Psychology Quarterly, 54, 330-342.

Kern, R., & Warschauer, M. (2000). Communicative foreign language teaching through telecollabora-tion. In K. van Esch & O. St. John (Eds.), Network-based language teaching: Concepts and practice (pp. 1-19). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kiecolt, K. J. (1994). Stress and the decision to change oneself: A theoretical model. SocialPsychology Quarterly, 57, 49-63.

Kiesler, S., Siegel, J., & McGuire, T. W. (1984). Social psychological aspects of computer-mediatedcommunication. American Psychologist, 39(10), 1123-1134.

LaRose, R. (2001). On the negative effects of e-commerce: A sociocognitive exploration of unregulat-ed on-line buying. Journal of Computer Mediated Communications, 6(3), 114-122.

Lee, H. (2005). Behavioral strategies for dealing with flaming in an online forum. SociologicalQuarterly, 46(2), 385-403.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, and society. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Nielsen Media Research. (1997). The Spring 1997 Commerce Net/Nielsen Media InternetDemographic Survey, Full Report, Volume I of II.

Novak, T. P., Hoffman, D. L., & Venkatesh, A. (1997, October). Diversity on the internet: The rela-tionship of race to access and usage. Paper presented at the Aspen Institute's Forum on Diversityand Media, Queenstown, MD.

Orton-Johnson, K. (2007). The online student: Lurking, chatting, flaming and joking. SociologicalResearch Online, 12(6), 223-245.

Ridgeway, C. L. (1982). Status in groups: The importance of emotion. American Sociological Review,47, 76-88.

Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9,185-211.

Savicki, V., Lingenfelter, D., & Kelly, M. (1998). Gender language style and group composition ininternet discussion groups. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 2(3), 1-12.

Schuman, H., Steeh, C., Bobo, L., & Krysan, M. (1997). Racial attitudes in America: Trends andinterpretations (Rev. ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Shott, S. (1979). Emotion and social life: A symbolic interactionist analysis. American. Journal ofSociology, 84(6), 1317-1334.

Siegel, J., Dubrovsky, V., Kiesler, S., & McGuire, T. W. (1986). Group processes in computer-mediat-ed communication. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 37, 157-187.

Stryker, S. (1987, August). The interplay of affect and identity: Exploring the relationship of socialstructure, social interaction, self and emotions. Paper presented at the American SociologicalAssociation Meetings, Chicago, IL.

Tanis, M., & Postmes, T. (2007, March). Two faces of anonymity: Paradoxical effects of cues to iden-tity in CMC. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(2), 955-970.

Turner, J. H. (1994). A general theory of motivation and emotion in human interaction,Osterreichische Zeitschrift fur Soziologie, 26, 20-35.

Th

eJ

ou

rna

lo

fTe

ch

no

log

yS

tud

ies

13

Turner, J. H. (1998). The structure of sociological theory (6th ed.). Belmont, CA:Wadsworth.Publishing Company.

Tynes, B. M. (2007, November). Role taking in online “classrooms”: What adolescents are learningabout race and ethnicity. Developmental Psychology, 43(6), 1312-1320.

Walther, J. B., Anderson, J. F., & Park, D. W. (1994). Interpersonal effects in computer-mediated inter-action: A meta-analysis of social and antisocial communication. Communication Research, 21(4),460-487.

Walther, J. B., & Burgoon, J. K. (1992). Relational communication in computer-mediated interaction.Human Communication Research, 19(1), 50-88.

Wasserman, I. M., & Richmond-Abbott, M. (2005, March). Gender and the internet: Causes of varia-tion in access, level, and scope of use. Social Science Quarterly, 86(1), 252-270.

Weiser, E. B. (2001). The functions of internet use and their social and psychological consequences.Cyberpsychology and Behavior, 4(6), 723-743.