European Expression - Issue 90

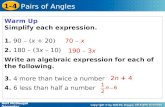

-

Upload

european-expression -

Category

Documents

-

view

224 -

download

3

description

Transcript of European Expression - Issue 90

Ντ. ΣταΣιΝόπόυλόΣ

EU/ USTrade and investment agreement in a changing global environment

Χ. ΜυλωΝαΣ

The Politics of Nation-Building

Π Ε Ρ Ι Ε Χ Ο Μ Ε Ν Α 3

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

EΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ EΚΦΡΑΣΗτ Ρ ι Μ Η Ν ι α ι α Ε Κ Δ ό Σ Η Ε υ Ρ ω π α Ϊ Κ ό υ π Ρ ό Β λ Η Μ α τ ι Σ Μ ό υ

ΕτΟς ΙδΡυςης : 1989 • ISSN: 1105-8137 • 5 ΕΥΡΩ • ΧΡΟΝΟΣ 22 • ΤΕΥΧΟΣ 90 • ΙΟΥΛΙΟΣ - ΑΥΓΟΥΣΤΟΣ- ΣΕΠΤΕΜΒΡΙΟΣ 2013

ΙΔΙΟΚΤΗΤΗΣ - ΕΚΔΟΤΗΣ:«ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΚΟΙΝΩΝΙΑ-

ΠΟΛΙΤΙΚΗ-ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ-ΘΕΣ-ΜΟΙ», Μη Κερδοσκοπικό

ςωματείοΟμήρου 54 - Αθήνα - 106 72

τηλ.: +30 210 3643224Fax: +30 210 3646953

E-mail: [email protected]://www.ekfrasi.gr

ΚΩΔΙΚΟΣ ΕΝΤΥΠΟΥ: 1413

ΕΚΔΟΤΗΣ-ΥΠΕΥΘΥΝΟΣΣΥΜΦΩΝΑ ΜΕ ΤΟΝ ΝΟΜΟ:

Νίκος Γιαννής

ΑΡΧΙςυΝτΑΞΙΑ:Βικτώρια Λαμπροπούλου

ΔΙΕΥΘΥΝΣΗ:Κατερίνα Ανδρωνά

Στο τεύχος αυτόσυνεργάσθηκαν:

Γιώργος ΕμμανουήλΑγγελική ΚουφοπούλουΒικτώρια Λαμπροπούλου

Ιουλιανός ΜεμετάηΧάρης Μυλωνάς

Αλέξανδρος ΝικολαΐδηςΝτίνος Στασινόπουλος

Victor Sukup

ΕΠΙΜΕΛΕΙΑ ΕΚΔΟΣΗΣ:Εκδόσεις: «ΗΛΙΑΙΑ»

δηΜ. ςΧΕςΕΙς:iForce Communications Α.Ε.

4 Εισαγωγικό σημείωμα εκδότη…...............................................................................................5

ΣχέΣέιΣ κρατών – έ.έ.

4 EU/ US. Trade and investment agreement in a changing global environment ..............7του Ντίνου Στασινόπουλου

4The Emergence of Greek Civilization Via Eu Programmes ............................................ 11Του George Emmanuel

έπικαιροτητα

4 «Οι υπερεθνικές προκλήσεις απαιτούν τέτοιου είδους υπερεθνικές απαντήσεις, τις

οποίες τα μεμονωμένα κράτη δεν μπορούν πλέον να προσφέρουν» ......................... 13An interview with Sir Graham Watson

αποψέιΣ

4 Regional integration in Europe - Some thoughts about lessons from outside ............ 16Του Victor Sukup

4The Politics of Nation-Building - Making Co-Nationals, Refugees, and Minorities . 23του Χάρη Μυλωνά

4 European Union in the age of undocumented migrants ................................................. 32Του Julian Memetai

4Το Δημόσιο Management ως εργαλείο διοικητικής μεταρρύθμισης στην εποχή της οι-

κονομικής παγκοσμιοποίησης ............................................................................................. 34Της Αγγελικής Κουφοπούλου

4Ζητείται ανάπτυξη. Υπάρχει ελπίδα; .................................................................................. 37Του Αλέξανδρου Νικολαΐδη

ΜονιΜέΣ ΣτηΛέΣ

4Τί τρέχει στην Ευρώπη ........................................................................................................... 37 4Τα Νέα της Έκφρασης ............................................................................................................ 40

Σας ενημερώνουμε ότι από το τεύχος 89 το περιοδικό «Ευρωπαϊκή Έκφραση» αποστέλλεται ταχυδρομικώς

μόνον σε όσους έχουν καταβάλλει την ετήσια συνδρομή τους.

4

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

C o N T E N T S

EVRoPaIkI EkFRaSSIq U a R T E R l y E d I T I o N o N E U R o P E a N I S S U E S

F I R S T P U B l I S h E d : 1 9 8 9 • I S S N : 1 1 0 5 - 8 1 3 7 • E U R o 5 • y E a R 2 2 • V o l . 9 0 • J y l y - a U G U S T - S E P T E M B E R 2 0 1 3

PRoPRIEToR - EdITIoN:

"European Society, Politics,

Expression, Institutions", non

Profit Making Company

54 omirou St., athens 106 72

Tel.: +30 210 3643224

Fax: +30 210 3646953

E-mail: [email protected]

http://www.ekfrasi.gr

EdIToR-PUBlIShER By laW:

Nicos yannis

PUBlIShING dIRECToR:

Victoria lampropoulou

dIRECTIoN:

katerina androna

CoNTRIBUToRS:

George Emmanuel

aggeliki koufopoulou

Victoria lampropoulou

Julian Memetai

harris Mylonas

Alexandros Nikolaidisdinos Stasinopoulos

Victor Sukup

TEChNICal adVISoR:

hliea

PUBlIC RElaTIoNS

iForce Communications Sa

4 Editorial… .....................................................................................................................................5

MeMber relations - eU

4 EU/ US. Trade and investment agreement in a changing global environment ...............7By Dinos Stasinopoulos

4The Emergence of Greek Civilization Via Eu Programmes ............................................ 11By George Emmanuel

aCtUalitY

4 “Supranational challenges require the kind of supranational responses which

individual statescan no longer offer” ................................................................................... 13

an interview with Sir Graham Watson

oPinions

4 Regional integration in Europe - Some thoughts about lessons from outside ............ 16By Victor Sukup

4The Politics of Nation-Building - Making Co-Nationals, Refugees, and Minorities . 23By Harris Mylonas

4 European Union in the age of undocumented migrants ................................................. 32By Julian Memetai

4 Public Management as a tool of administrative reform in the age of economic

globalisation ............................................................................................................................ 34By Aggeliki Koufopoulou

4 Requested growth. Is there hope? ........................................................................................ 37By

PerManent ColUMns

4What’s going on in Europe .................................................................................................... 40

4 European Expression News .................................................................................................. 44

E d I T o R I a l 5

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

η εφηβεία για το ανθρώπινο είδος είναι μια διακριτή αναπτυξιακή φάση εξαιτίας των ρα-γδαίων βιο-σωματικών αλλαγών και των νέων εξελίξεων, ως προς τις νοητικές ικανότητες και

ως προς την σεξουαλικότητα. Δεν είναι και πολύ διαφορε-τικά τα πράγματα με το Ευρώ, τόσο ως προς την εσωτερική ωρίμανση όσο και ως προς την εξωτερική του ορμή, αφού από τις 15.1.1999 έχουν περάσει πλέον 15 χρόνια και τα κράτη – μέλη που έχουν προσχωρήσει είναι πια 18, μαζί με τη νεοεισελθούσα Λεττονία, ενώ το 2015 αναμένεται και η Λιθουανία. Βρίσκεται λοιπόν στην περίοδο του ασυγκρά-τητου εφηβικού ενθουσιασμού, αλλά και των αναταράξεων της ήβης, που οφείλονται αφενός στις κατασκευαστικές ιδιαιτερότητες και αδυναμίες του dNa του (βλ. Μάαστριχτ/ΟΝΕ), όσο και στην ικανότητα κατάλληλων επιλογών για την τελική διαμόρφωση του, αλλά και των αλληλεπιδράσε-ων με το εξωτερικό περιβάλλον, όπου ενόψει ενηλικίωσης αντιμετωπίζεται όλο και περισσότερο ως ισότιμος παίκτης, άρα δυνητικώς, απειλή, φίλος ή συνεταίρος - εραστής.

Δεν είναι και λίγα αυτά που κατάφερε «το παιδί» μέχρι στιγμής. Πολύ χαμηλός πληθωρισμός, 2% και εξίσου χαμηλά επιτόκια, μέχρι 4,70%, όλο αυτό το διάστημα. Η Ευρωπαϊκή Κεντρική Τράπεζα λοιπόν το πήγε καλά σε σχέση με την αποστολή της στο πλαίσιο της Ευρωζώνης, παρότι η Ελλάδα δεν αξιοποίησε παραγωγικά αυτήν την ευκαιρία, αντιθέτως δανείστηκε δίκην πολιτικού ανταγωνισμού, διαφθοράς και πελατειακής αναπαραγωγής, παραπάνω κι απ’ τη σύνεση που θα της επιτρεπόταν ακόμη κι αν ήταν Γερμανία. Η ΕΕ απέκτησε το δεύτερο παγκόσμιο αποταμιευτικό νόμισμα και το κύρος που τη συνοδεύει εξ’ αυτού, που αντιστοιχεί στο 24% των παγκοσμίων συναλλαγματικών αποθεμάτων για το 2013. Εξαφανίστηκε το κόστος των συναλλαγματικών κιν-δύνων, το οποίο έχει εγκύρως υπολογισθεί στα €24δις κι έτσι μειώθηκε αισθητά το κόστος των επιχειρήσεων, που εισά-γουν και εξάγουν χωρίς φόβο, αρκεί να έχουν να εξάγουν......Το € εξελίχθηκε σε παράγοντα σταθερότητας επιχειρήσεων και ανθρώπων. Δεν φοβάσαι τον πληθωρισμό, αποφασίζεις μακροπρόθεσμα, αρκεί να είσαι ικανός να αξιοποιήσεις αυτό

το πλεονέκτημα και να μην ενδίδεις στις σειρήνες των πι-στωτικών καρτών χωρίς παραγωγικό αντίκρυσμα. Με βάση μελέτη της Ευρωπαϊκής Επιτροπής, το € αύξησε σε ποσοστό επέκεινα του 50% τις εμπορευματικές συναλλαγές στην ευ-ρωζώνη, με άμεσο όφελος τη δημιουργία 8,7 εκατομμυρίων νέων θέσεων εργασίας την περίοδο 1999-2010. Χωρίς το € η ΕΕ θα βρισκόταν αφοπλισμένη μπροστά στην παγκόσμια χρηματοοικονομική κρίση.

Από συστημική άποψη ωστόσο το € χωλαίνει. ΟΝΕ χωρίς το «Ο» δεν μπορεί να νοηθεί και ΟΝΕ με το «Ο», όταν γίνει, δεν νοείται χωρίς πολιτική ένωση. Εξάλλου δεν μπορείς να ερωτευτείς μια νομισματική ένωση, ούτε καν μια ενιαία αγορά, όσο σημαντικά κι αν είναι αυτά. Είναι σαν να θέλεις κάποιον μόνον για τα λεφτά του, πόσο μάλλον αν δεν υπάρχει μια σιγουριά ότι όλοι στην οικογένεια του έχουν χρήματα! Με την επικείμενη τραπεζική ένωση που εκκινεί οριστικώς το φθινόπωρο τρέχοντος έτους 2014, την ενιαία δημοσιονομική πολιτική, δηλαδή και έναν κοινό φορολο-γικό οδηγό, τη συνακόλουθη και αναπόφευκτη οικονομική ένωση, την πολιτική ένωση και δημοκρατική νομιμότητα και λογοδοσία στην οποία θα πρέπει να οδηγήσουν τελικώς οι Ευρωεκλογές, η Ευρώπη και όχι απλώς η Ευρωζώνη θα αποκτήσουν νέα μοναδική ορμή και θα αναβαθμιστούν στον παγκόσμιο ανταγωνισμό. Μια κοινή εξωτερική πολιτική και μια πολιτική άμυνας θα είναι η λογική συνέχεια, κάτι που ενδιαφέρει ιδιαίτερα την Ελλάδα.

Μόνον στην Ελλάδα, αμφισβητείται, όσο αμφισβητείται, το Ευρώ και όχι τόσο η Ευρώπη, ενώ σε όλη την υπόλοιπη Ευρώπη, οι Ευρωσκεπτικιστές βάλλουν κατά της ΕΕ αλλά όχι κατά του €. Ίσως γιατί το € φέρνει τη σταθερότητα, πειθαρχία και την τάξη που μας λείπουν, τη διαφάνεια, την αξιοκρατία και έναν πιο υγιή ανταγωνισμό που απαιτεί η ανάπτυξη, την τήρηση του νόμου, κανόνων, δικαιωμάτων και δεοντολογίας, πιθανόν γιατί αποθαρρύνει τους ευκαιριακούς, τους άπλη-στους και τους κατεργάρηδες που γι’ αυτό αντιδρούν.

Ακόμη και το Δολάριο (dollar), ως το πλέον διαδεδομένο νόμισμα στον κόσμο, αφού το 2006 κυκλοφορούσαν 760 δι-σεκατομμύρια δολάρια, τα δύο τρίτα των οποίων εκτός ηΠΑ,

Ευρω-εφηβεία, 15 χρονών το Ευρώ

του Νίκου Γιαννή

E d I T o R I a l6

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

σε μια πολύ λιγότερο διαφορετική χώρα 13 μόλις πολιτειών και μικρή ιστορία, χρειάστηκε μια δεκαετία περίπου μετά την αμερικανική ανεξαρτησία το 1776 για να αντικαταστήσει τα διάφορα νομίσματα. Σήμερα, ενώ εξακολουθεί να θεωρείται το ισχυρότερο νόμισμα στον κόσμο, αμφισβητείται ανοιχτά η κυριαρχία του από το €. Στο συμβολικό επίπεδο ακόμη και το ελληνικό «τάλιρο» προέρχεται από τη γερμανική λέξη τάλερ (Thaler, συντομογραφία του Joachimsthaler), που ήταν το νόμισμα που χρησιμοποιήθηκε από το 16ο αιώνα στη Βοημία και που οδήγησε στο περίφημο δολάριο. Όταν οι Αμερικανοί κέρδισαν την ανεξαρτησία τους το 1776, με πρωτοβουλία του Τόμας Τζέφερσον και απόφαση του Κογκρέσου, προτίμησαν την ονομασία «δολάριο» για τη νομισματική τους μονάδα αντί της της βρετανικής λίρας, υιοθετώντας για πρώτη φορά ένα κράτος το δεκαδικό νομισματικό σύστημα. Έως το 1862 κυκλοφορούσαν μονάχα νομίσματα δολαρίου, καθώς οι Αμε-ρικανοί ήταν δύσπιστοι προς τα χαρτονομίσματα, λόγω της διαρκούς τους υποτίμησης κατά την περίοδο της αποικιοκρα-τίας. Το € αυτό το απέφυγε κατά την παιδική του ηλικία. Το πρώτο χαρτονόμισμα στις ηΠΑ τυπώθηκε το 1862 εν μέσω του αιματηρού εμφυλίου πολέμου. Ως το 1975 το δολάριο είχε αντίκρισμα σε ασήμι ή χρυσό. Σήμερα είναι λογιστικό χρήμα και διαπραγματεύεται με βάση την προσφορά και ζήτηση.

Να δείτε ότι η Ευρώπη το 2014 θα βγει τελικώς πιο δυνατή από ποτέ. Σε πείσμα όσων την εχθρεύονται φανερά, όσων την υποτιμούν και όσων την κοιτούν με μισό μάτι ή Αυτοί είναι εκτός των ευρωπαϊκών συνόρων, αντιστοίχως: (1) η Ρωσία κι ένα μέρος του αραβικού κόσμου, (2) η Κίνα και (3) ο «κηδεμόνας» ηΠΑ. Εντός των τειχών, οι εθνικοί και ατομικοί εγωϊσμοί και αυταρχισμοί, ο μονοπολιτισμός κι ο αναχωρητι-σμός, ο ρατσισμός και η ξενοφοβία, ο αριστερός και ο δεξιός ολοκληρωτισμός, όσοι θέλουν την επιστροφή στον πόλεμο και τη βία γιατί τα θεωρούν αναπόφευκτα ή γιατί απλώς συμ-φέρει, η εσωστρέφεια, ο λαϊκισμός και ο ευρωαρνητισμός, θα είναι οι μεγάλοι ηττημένοι των επόμενων Ευρωεκλογών, τις οποίες έθεσαν ως ύψιστο στόχο και παρά την οξύτατη κρίση από την οποία επιδιώκουν να επωφεληθούν τυχοδιωκτικά, τελικώς αυτές θα είναι το κύκνειο άσμα τους.

Πράγματι, η Ευρώπη έχει σοβαρά προβλήματα να αντιμετωπίσει. Η ενότητα μέσα από τη διαφορετικότητα (e pluribus unum) επιβραδύνει τις αποφάσεις, τις καθιστά πολύπλοκες και δυσνόητες και αυξάνει τη γραφειοκρατία, αυτό είναι το τίμημα της δημοκρατίας, του συγκερασμού πολλαπλών συμφερόντων και πολιτισμικών ταυτοτήτων, της μη επιβολής, του να μπορούν όλοι να αναγνωρίζουν στις αποφάσεις ένα μέρος του εαυτού τους, όχι όλα σε έναν αλλά όλοι από κάμποσο ο καθένας, έστω όχι το ίδιο. Η πλασματική σύγκλιση των οικονομιών που συμμετέχουν στην ευρωζώνη, που στηρίχθηκε στην υπερχρέωση των προβληματικών με

πρώτη την Ελλάδα, κατευθύνθηκε προς κερδοσκοπικές επενδύσεις και υπέρμετρη κατανάλωση, χωρίς παραγωγικό αντίκρισμα. Η ευθύνη των εθνικών κρατών, κυβερνήσεων, πολιτικών και γραφειοκρατίας, είναι τεράστια, αφού πα-ραβίασαν τους κανόνες δημοσιονομικής πειθαρχίας του Μάαστριχτ -Γαλλία και Γερμανία έδωσαν πρώτες το κακό παράδειγμα-, οι αδύναμες δημιούργησαν φούσκες δημοσίου χρέους, άφησαν τις τράπεζες να δανείζουν ασύστολα για αγορές ακινήτων και κρατικών ομολόγων, υπονόμευσαν την ανταγωνιστικότητα και εξέθρεψαν μια τεχνητή ευημερία.

Τελικώς, μόνον η Ευρώπη διαθέτει αυτήν τη δύναμη, τις καλύτερες, πιο δημοκρατικές και πιο αποτελεσματικές, λύσεις, για τη σύμπλευση διαφορετικών. Η επικείμενη εκλογή για πρώτη φορά του Προέδρου της Ευρωπαϊκής Επιτροπής από τους πολίτες διαμέσου του Ευρωπαϊκού Κοινοβουλίου που εκείνοι θα εκλέξουν, του προσδίδει τη δημοκρατική νομιμο-ποίηση να ακολουθήσει μια πολιτική, που θα είναι ευρωπαϊκή και όχι συμβιβασμοί εθνικών αξιώσεων ή και εκβιασμών. Δεν θα είναι πια ένας ανεξέλεγκτος δημόσιος υπάλληλος, αλλά ένας υπεύθυνος εκλεγμένος που λογοδοτεί και προίσταται ενός σώματος που θα μοιάζει με μια κανονική κυβέρνηση. Γι’ αυτό κανονικά θα πρέπει τα κόμματα σε κάθε κράτος στις Ευ-ρωεκλογές να τοποθετήσουν στην κεφαλή του ψηφοδελτίου, μαζί με το όνομα του ευρωπαϊκού κόμματος και το όνομα και τη φωτογραφία του προτεινόμενου Προέδρου της Επιτροπής.

Το υβρίδιο ευρωπαϊκής εξωτερικής πολιτικής δεν είναι ακόμη διεθνής καταλύτης, αλλά είναι το πλέον διεθνώς αποδεκτό, ως δίκαιο, ισορροπημένο και προς την ολοκλη-ρωμένη ανάπτυξη όλων. Η ΕΕ είναι ο μεγαλύτερος δότης αναπτυξιακής και ανθρωπιστικής βοήθειας στις φτωχές χώρες του πλανήτη. Η Ευρώπη είναι αντιμέτωπη με σημα-ντικές αδυναμίες αλλά και με σημαντικότερες ευκαιρίες, τις οποίες ξέρει να αξιοποιεί. Είναι ο πρώτος κόσμος, όπου γεννήθηκαν οι επικρατέστερες αξίες και τέθηκαν τα θεμέλια του σύγχρονου παγκόσμιου πολιτισμού, με τη βαθύτερη και σημαντικότερη ιστορία, ιδέες και παραδόσεις. Ή μήπως δεν είναι έτσι; Ο υπόλοιπος κόσμος κοιτάζει, εμπνέεται και προσβλέπει σε αυτήν. Είναι το ωραιότερο σημείο του πλανήτη για να ζει κανείς, με μοναδική ποιότητα ζωής και ασφάλεια, ελευθερία, ευημερία και κοινωνική δικαιοσύνη παρά την πρόσκαιρη περιορισμένη διολίσθηση, κάτι που αποδεικνύεται περίτρανα από το ότι είναι μακράν ο πλέον προσφιλής προορισμός από όλες τις χώρες προέλευσης, μεταναστών, φοιτητών, τουριστών, ασθενών κ.λπ.

η ΕΕ θα βρει σύντομα τον δρόμο της. Η πολιτική ένωση θα έλθει ταχύτερα από το αναμενόμενο παρά τις κασσάνδρες. Μπορεί και γι’ αυτό οι αγορές, παρόλ’ αυτά, να εμπιστεύονται το €, όπως φαίνεται. Χρόνια πολλά €, καλώς να ορίσεις στον ερωτικό κόσμο των μεγάλων!

Σ Χ Ε Σ Ε Ι Σ Κ Ρ Α Τ Ω Ν 7

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

EU/USTrade and investment agreement in a changing global environment

by Dinos Stasinopoulos*

I. INTRODUCTION

World trade is shifting east-wards as the dynamics of global trade undergo

important transformations, arising from economic and trade strength of emerging economies such as Chi-na. New methods of conducting trade with fragmentation of production and new technologies dominate commer-cial transactions. Globalisationis ex-panding into international and re-gional production networks creating

truly integrated marketplace. In addi-tion emerging economies are increas-ing their transactions with developed countries and their share in the global economy.

although the shift to China and other asian countries cannot be stopped it is opportune for the EU and the US to consider deepening their economic and trade relationships with setting market standards in the rest of the globalised world..

The EU and the US have issued a joint statement in February 2013 to launch negotiations on a trans-

atlantic free-trade agreement. EU leaders and President Barack obama finally announced the formal launch of the negotiations in June 2013 aimed at tackling trade in goods and services plus a wide range of trade and invest-ment issues such as market access and other behind-the -border obstacles (1). The trade deal is a major economic pri-ority for the EU and the US and it has the potential to enhance the world s̀ largest economic trade relationship and support jobs on both sides of the atlantic

This note outlines the scope of these important negotiations and * formerly with the European Commission, currently Consultant in International Affairs

Πηγή: www.dw.de

Σ Χ Ε Σ Ε Ι Σ Κ Ρ Α Τ Ω Ν8

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

argues for a comprehensive transat-lantic partnership agreement to deal with global issues that require EU-US leadership.

II. THE SCOPE OF THE AGREEMENT

despite tensions in trade issues such as intellectually prop-erty rights and privacy, com-

mon ground exists between the EU and the US and there is scope for further economic integration. The macro and micro policies of the EU and the US are more aligned than ever before.

however both sides have yet to de-cide how to approach negotiations and move from simple tariff reductions to the more complicated task of removing inside the borders/domestic regula-tions in the various economic and trade sectors. The rising economic and trade importance of China is expected to provide more incentives for a deal as each side is attempting to assess the other’s level of political commitment to a comprehensive agreement.

an agreement between them would set the terms for the rest of the global economy as their relations are the foundations for the international economic order.

The EU and the US account for roughly 40 % of world GdP and over a third of global trade. The EU and the US are the world’s largest economies, the largest commercial partners for other important economies and they maintain the world’s largest bilateral trade relationship (2).

The agreement would have to include other important services sectors, public procurement and new-generation issues such as competition and intellectual property. This deal also aims at eliminating import duties and harmonise regulations on cars, drugs and medical equipment. Ge-netically modified organisms (CMos), environmental and health standards,

food safety, cultural diversity and labour and consumer rights are also important issues.

all these issues are difficult to negotiate since important regulatory divergences exist not only between the EU and the US but also among member countries in the EU and among states in the US. It is encouraging that a free trade agreement has been backed by large number of business associations on both sides of the atlantic, and the new US administration and the EU appear - to have an expanded second-term agenda for trade negotiations. With any complicated set of negotia-tions reaching across a large number of sectors, there will always be a large number of’exceptionalcases made; The EU US agreement will be no different. however, lowest common denomina-tor agreements across a large number of these ‘exceptional case’ areas has to be avoided so as not to undermine the positive impact an agreement will have on the EU and US economies and the global trade. Common standards could facilitate trade by influencing standards-including health and sani-tary regulations and licensing proce-dures introduced on other countries markets. This may be more important in areas that have not been regulated by the WTo. Such an agreement could help to ensure that the EU and the US and not China would set global stan-dards on product safety and protec-tion of intellectual property in years to come. Chances are that there will be an eventual set of “rules” on these issues and hopefully will be more than the best endeavour.The US is worried that over the course of negotiations the scope of the agreement will narrow dramatically as specific industries are carved out on the European side due to mainly French protectionism, limiting its economic impact. although charges that Washington was spying on the

28-nation EU soured the atmosphere EU analysts are optimistic that a deal is possible given the substantial gains expected for both sides.

SECTORS TO BE CONSIDEREDuu regulatory cooperation, non/tar-iff barriers and technical barriers to tradeattempts in the past for reinforced

integration and regulatory coopera-tion have been hindered by a bias in favour of tariff elimination over non-tariff barriers (NTB) reductions and services liberalisation. This limited approach was feasible politically as it is easier to quantify the benefits to trade and the economy compared to the ef-fects of an NTB reduction. Furthemore NTB have been shaped by institutional structures and agreeing on regulatory convergence produces bureaucratic constraints. Regulation in both the EU and US is divided among different independent agencies.

There are also philosophical dif-ference as the EU law is based on the “precautionary principle” which places the burden of proof on new products to demonstrate that they do not harm human health or the environment. The US system is more flexible based on the notion that attitudes towards risk are not consistent within either the EU or the US.

divergences in customs admin-istrative procedures and behind the border regulatory restrictions, impact on issues related to consumer protec-tion, food safety and public health. The non-tariff barriers come from diverg-ing regulatory systems but also other non-tariff measures related to certain aspects of security or consumer protection.Non-tariff barriers origi-nating from different values, public preferences and different approaches towards risk management are in the

Σ Χ Ε Σ Ε Ι Σ Κ Ρ Α Τ Ω Ν 9

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

fields of protection of health, safety and the environment. Important facets of tackling these divergences include application of international standards, streamlined testing and certification requirements and a consultation mechanism to address specific prob-lems.

In any EU/US deal trade, relations with China must be considered. an ambitious but realistic zero-tariff on goods approach could covered most of farm product and it would be wise politically to remove all tariffs appli-cable to other countries outside the bilateral agreement. over the past 20 years China has contributed to trade liberalisation globally and their com-mitments have gone beyond those at other countries.uu Convergence/cooperation in sani-tary and phytosanitary (SPS) issuesa comprehensive agreement

should include a mechanism for ad-dressing divergences on both food and non-food sectors and identifying ‘essentially equivalent’ regulations for mutual recognition in the health, safety and consumer sectors. Negative trade effects should be eliminated and more certainty introduced by relying more on science based practices.uu reduction/elimination of tarrifs

a comprehensive agreement should get as close as possible to re-ducing/removing all duties on trade in industrial and agricultural products. Regarding tariffs there is a need to dif-ferentiate between goods and services. as global trade in manufactured goods is already substantially liberalised emphasis should be on the unfinished business of removing tariffs in the area of goods sector and reducing non tariff barriers.uu liberalisation of trade in services

Both sides quite correctly have placed services at the heart of their trade strategy. liberalisation of ser-

vices globally is rather limited and fragmented.

high barriers to trade in services constrain trade and some liberalisa-tion would have to be carried out on a most-favoured nation (MFN) basis as it is rather difficult to build in a third-party discriminatory element in non-tariff measures. Priority may be given in financial and telecommunica-tions, shipping, aviation and insurance services.

The services economies of the EU and the US are substantially interlinked especially in sectors such as financial, telecommunication, insurance and computer services. a comprehensive agreement would open services mar-kets which are very little open globally and develop a framework for effective cooperation between regulators also at the sub-federal levels. The EU is the leading services exporter and the world’s largest services economy. lib-eralisation of trade in services should principally include all sectors and target the broadest elimination of all discriminatory measures in the sectors covered. Regarding the liberalisation

of investment in services and non/service sectors, exceptions should be kept to a minimum. Foreign direct Investment (FdI) has become an ex-clusive EU competence since the entry into force of the lisbon Treaty. The EU Services directive which was meant to streamline regulations governing a vast range of service sectors, but under achieves despite its good intentions. The result is that foreign companies have to deal with different regulations in each member state. It is hoped that in financial services the EU and the US will agree to some rules that will lead to similar regulations.

liberalisation of communication services is a sensitive area for several EU states. By keeping cultural exception out of the talks they want to protect Europe’s cultural diversity(audiovisual, film and television industries) from freer international trade (3).

differences among member states regarding tactics may come to light during the course of negotiations It may be politically expedient to start negotiations with no broad policy areas explicitly excluded and negotiate

Σ Χ Ε Σ Ε Ι Σ Κ Ρ Α Τ Ω Ν10

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

the carving out of certain areas of the communication sector and offer some concessions in return (4).uu Competition

Globalisation and the growth of cross-border merg-ers present major challenges for EU and US competition authorities. They highlight the importance of seeking to secure a degree of convergence and co-ordination among competition law enforcement systems. EU’s competi-tion law and US’s antitrust law despite different historical antecedents, are in most respects pursuing the same objectives. Some convergence has been achieved in the field of merger control but there is a need for some degree of harmonisation while it is understood that procedural differences have to be lived with. Restrictions like concerted practices, abuses of dominant posi-tions, private monopolies and unfair trade practices should be covered and competition should be increased with no exemptions by adhering to general principles such as non/discrimination and procedural fairness.uu Public procurement

Public procurement is an impor-tant component of industrial and trade policy in the EU and the US. Both sides have introduced legislation to foster domestic industry in order to compete in world markets. Rules to ensure a level-playing field should be developed to avoid discrimination against foreign competitors and make public procurement procedures more efficient The opening up of public procurement markets is intended to go beyond the relevant WTo agree-ment and introduce more precise and effective disciplines particularly in relation with tendering procedures by applying national treatment at all levels of government transactions.

Civil engineering companies and producers of heavy equipment are expected to gain from the opening of the markets. Resolution of these issues may be hampered by the US federal System and by Buy america clause in the US legislation (5).uu E-Commerce, digital Economy and Intellectual Property Rights (IPR)The agreement should also cover

e- commerce and digital economy that reflect effectively the convergence of goods, services, technology and the development of value-chains. IPR such as copy rights, trade marks, geographi-cal indications, patents should also be negotiated with a view to effective enforcement by means of comple-menting the WTo TRIPS agreement.

III.CONCLUSIONS

The launching of negotiations for a trans-atlantic free trade agreement between the EU and

the US has generated a substantial de-bate among analysts pointing out ben-efits/disadvantages of the agreement. The EU US agreement will be a laud-able case at liberalising an important international trade market. Given large potential gains the EU and the US should put emphasis on a compre-hensive agreement toliberalise trade and investment with a priority on tar-iffs elimination and binding targets for progress in reducing/eliminat-

ing regulatory bar-riers. Previous at-tempts to negotiate a trade deal have been hindered by the bias in favour of tariff elimina-tion over non-tar-iff barriers (NTB) reductions and liberalisation of

services. This limit-ed approach was polit-

ically feasible since it was easier to quantify the benefits to trade of tariffs reduction than to gauge the effects of an NTB reduction. howev-er the two sides face a major challenge in deciding how to approach negotia-tions in order to cover domestic regu-lations and move from simple tariff re-ductions to the more complicated task of removing inside the borders regu-lations in the various economic and trade sectors.

It is encouraging that the agree-ment is been supported by a large number of business representatives in both sides of the atlantic. They feel that the agreement is economi-cally and geopolitically crucial for the world as well for the two sides directly concerned as it will help to set trade rules for the global economy that the rest of the world would be feel obliged to follow.

reFerenCes

(1) “after long buildup US-EU free trade talks finally begin” doug Palmer, Re-uters 18 June 2013

2) “Transatlantic trading” The Economist, 2 February,2013

(3) “Transatlantic free trade” Javier Solana, European Voice, 4 January, 2013

(4) “EU nations quarrel as US trade talks are set”, International herald Tribune 18 June, 2013, “EU-Us trade talks launched amid French fury with Brus-sels” FT. Com17 June 2013

(5) “Eyes on the prices in EU/US trade “, Fi-nancial Times June 18,2013

Σ Χ Ε Σ Ε Ι Σ Κ Ρ Α Τ Ω Ν 11

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

The Emergenceof

Greek CivilizationVia

Eu Programmes

by George Emmanuel*

Culture is the way of life of a group of people, sharing the same beliefs, values, symbols and behaviors which are transmitted from generation to generation, formulating the historical continuity of people.

In order to deal with the common cultural values of Greece and Europe and the potential of Greek civilization emergence we can see that in classical times there was not a unified state of Greece.

however, there an intensive con-sciousness of national unity among Greeks did exist and had as common elements the single language, despite the differentiation in local dialects, and the values of human civilization depicted already in mythology and great poets like omeros, hsiodos, Pindaros and later in aishylos, Sofok-lis, Evripidis’ performances and more fundamentally on philosophers such as Sokrates, Platon, aristotles among others.

The Greek spiritual leaders and the teacher of rhetoric Isokratis had extended the Greekness meaning introducing as criteria not the tribal origin but the participation of the inhabitants and citizens in the Greek education.

The principles of democracy were born and implemented, for the first time in the world, in classical athens by Clesthenis and Pericles.

Before the Roman occupation in Greece the ancient Greeks had colo-nized Massalia and South Italy and influenced the western Mediterranean and had also colonized EyxinosPontos, thereby influencing culturally the people of eastern Europe and of course Greeks were influenced by them.

according to the Roman poet and philosopher oratio, the spread of Greek civilization within Europe had taken place through their interaction with the Romans.

The Greek cultural effect on Eu-rope continued and in the Middle ages (from the 5th to the 14th century a.c) with the copy of manuscripts of an-cient classical Greeks and their trans-lation into the latin language, mainly in Western European monasteries

and later in universities and addition-ally with the cultural acts of Christian apostolesMethodios and kyrillos in central and eastern Byzantine Europe.

afterwards, following the discov-ery of the printing press and the cir-culation of books during the European Renaissance, there emerged a great interest in the Greek spirit and, more specifically, the philosophy of Platon, thus contributing to the creation of the German philosophy.

These facts resulted in Europe being in the matrix of three revolutions over the centu-

ries that followed: the political one in France with the principles of the Enlightenment (equality, justice and brotherhood) in the 18th century, the industrial one in England and the so-cial one in Russia.

after the end of lengthy confronta-tions and the two catastrophic world wars, Europe becomes a workshop of procedures of people mobilization and participation of its citizens and of agreements for the consolidation of peace, security and well being of its population.

In the Europe of culture which

* Head of Managing Authority of European Territorial Cooperation Programmes / Greece

Σ Χ Ε Σ Ε Ι Σ Κ Ρ Α Τ Ω Ν12

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

is timelessly built from the Urals to the atlantic and the Mediterranean, it is necessary, especially in the cur-rent conditions of multidimensional European economic, social and moral crisis, to have the support of cultural diversity and the people’s cooperation and at the same time the promotion of intercultural dialogue. all these are needed to bring together the cul-tural identity, the specific traits of each people and the mutual understanding and solidarity in their common effort to build a future with peace, justice and friendship among the European people and to safeguard social cohesion, prog-ress and sustainable development.

after the Enlightenment, European Institutions recognize two roles in the culture: The research of the scientific timeless truth (what happened, when, how, with what reasons and implica-tions in the time and space) and the second the attribution of meaning in our lives and identity to the people and local communities’ activities.

This second dimension of the protection of the cultural inheritance and the contribution of culture to the sustainable development constitutes a part of the founding treaty of Rome and the successive European treaties and is supported by the European programs and by UNESCo of United Nations’ organization.

The European transnational, National and regional opera-tional programs, despite being

restricted in cultural resources (2,4% of NSFR 2007-13 via the operational programs of competitiveness, digi-tal conversion, Education, human re-sources, administrative reform, Envi-ronment, accessibility, the 5 regional operational programmes and the In-terreg) plus the framework for re-search and innovation, since they do not accept culture as a distinct the-

matic priority but integrate it in oth-er thematic priorities such as cultur-al tourism, sustainable environment, traditional local products, alternative transport, social solidarity, cultural education, scientific and cultural dia-logue and exchanges, creative innova-tion, cultural amateur creativeness of collective bodies, etc provide however the possibility to the public, self gov-ernment, regional and social cultural organizations to emerge, digitize and preserve their cultural inheritance and routes, as they were formulated in the historical continuity of the Greek and other European people.

2013/2014 is a planning year for all community programmes at European, National and regional level for the period 2014-20. It is significant that cultural bodies participate in the insti-tutional dialogue for the formulation of programmes in order to enhance their cultural traits of all 11 proposed thematic priorities of which they must choose 4.

our country has a wealthy cul-tural potential that comprises 20.000 declared archeological sites and historical monuments, 250 organized archeological sites, 210 prehistoric museums, classical, Byzantine and newer ones and thousands of folklore museums, collections and libraries.

It has the richest flora and fauna and landscape in Europe and the biggest number pro rata of traditional quality local products NoP.It has contributed to the world civilization with three civilizations which were ahead of their times: of the classical antiquity, the hellenistic and the Byzantine one.

our country can take advantage of its cultural timeless wealth, linking it creatively with the economic and social activities of its comparative ad-vantages in the tourist sector, in qual-ity food and in its sustainable natural and habitable environment.

The cultural, environmental and quality traditional local products and innovation

cluster routes is necessary under the current conditions of globalization to be linked on local, interregional, national and transnational level with the exploitation of new information technologies and modern cultural public, social and private institutions, in order to integrate in the European and International cultural and touristic networks, routes and partnerships.

To achieve sustainable cultural development via effective implemen-tation and synergy of the European programmes and projects, it is neces-sary to forge deeper and more mean-ingful partnerships within Europe and Mediterranean basin and to promote the human cultural capacity and identity of the local communities and creative and extrovert partnerships among organizations and regional bodies at all levels of public life for participative, transparent manage-ment for sustainable development with scientific assessment of cultural spaces and projects from the partner public, self-government and social bodies, fostering the employment in culture and emergence of best practices and services in the cultural sector.

Ε Π Ι Κ Α Ι Ρ Ο τ η τ Α 13

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

“Supranational challenges require the kind of supranational responses

which individual statescan no longer offer”

an interview with Sir Graham Watson

Sir Graham Watson, MEP, President of the aldE Party, offers his view on the upcom-ing elections for the European

Parliament.

f The European elections are coming up, however, many citizens have no clear idea of who / which party / what content they really choose with their vote – how do you explain your electorate why the European elec-tions are important? What is the message with which you and your liberal colleagues run for MEP?

“The European elections have become more important in view of the new powers of the EP and the EU introduced by the Lisbon Treaty. It is strange therefore that participation in the elections has fallen. I try to inform my electors of the influence the EU has over their lives and convince them of the importance on having a say over decisions taken in their names. I point out that supranational challenges such as world population growth, climate change and internationally organised crime require the kind of supranational responses which individual nation states can no longer offer.”

f The United Kingdom is currently

working on a review of the compe-tences of the European Union and is considering a withdrawal of certain competences. Is this the beginning of a gradual withdrawal from the EU?

“I certainly hope not. The presence of Liberal Democrats in government in the UK is a guarantee against with-drawal. Were the Conservatives to win an outright majority of the seats in Parliament they would hold a ref-erendum which might lead to the UK’s withdrawal.”

f The German Chancellor was harsh-

ly criticized, mainly in Greece, for the rigid austerity measures and the German influence in tackling the crisis – do you have the impression that Germany is perceived as too dominant in other Member States?

“Recent research by the Pew In-stitute shows that public opinion in almost all member states – including Cyprus, Greece, Portugal and Ireland – still favours cuts in public expenditure to reduce national debt. Respect for Angela Merkel across the EU is remark-ably high. Left wing protesters are in a minority. Greater EU integration is

Ε Π Ι Κ Α Ι Ρ Ο τ η τ Α14

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

«Οι υπερεθνικές προκλήσεις απαιτούν τέτοιου είδους υπερεθνικές απαντή-

σεις, τις οποίες τα μεμονωμένα κράτη δεν μπορούν πλέον να προσφέρουν»

μία συνέντευξη με τον Sir Graham Watson*

O Sir Graham Watson, μέ-λος του Ευρωπαϊκού Κοι-νοβουλίου και Πρόεδρος του κόμματος aldE (alli

anceofliberalsanddemocratsforEurope), καταθέτει τις απόψεις του για τις επερχόμενες εκλογές του Ευρωπαϊκού Κοινοβουλίου.

f Οι εκλογές του Ευρωπαϊκού Κοινο-βουλίου πλησιάζουν, μολαταύτα, πολλοί πολίτες δεν έχω ξεκάθαρη εικόνα για το ποιον ή ποιο κόμμα ή ποια πολιτική ατζέντα πράγμα-τι επιλέγουν με τη ψήφο τους- πώς εξηγείτε στους εκλογείς σας τον λόγο για τον οποίο οι ευρωεκλο-γές είναι σημαντικές; Ποιο είναι το μήνυμα με το οποίο εσείς και οι φι-λελεύθεροι συνάδελφοί σας θέτε-

τε υποψηφιότητα για τη θέση του μέλους του Ευρωπαϊκού Κοινοβου-λίου;“Οι ευρωεκλογές έχουν αποκτήσει

μεγάλη σημασία δεδομένων των νέων εξουσιών του Ευρωπαϊκού Κοινοβου-λίου και της Ευρωπαϊκής Ένωσης, τις οποίες εισήγαγε η Συνθήκη της Λισα-βόννας. Ως εκ τούτου, είναι παράξενη πτώση της συμμετοχής στις εκλογές. Προσπαθώ να πληροφορήσω τους εκλογείς μου σχετικά με την επίδραση της Ευρωπαϊκής Ένωσης στις ζωές τους και να τους πείσω για το πόσο σημαντι-κό είναι να έχουν λόγο στις αποφάσεις που λαμβάνονται επ’ ονόματι τους. Επισημαίνω ότι υπερεθνικές προκλή-σεις όπως η αύξηση του παγκόσμιου πληθυσμού, η κλιματική αλλαγή και το διεθνές οργανωμένο έγκλημα απαιτούν τέτοιου είδους υπερεθνικές απαντήσεις τις οποίες τα μεμονωμένα κράτη δεν

μπορούν πλέον να προσφέρουν.”

f Το Ηνωμένο Βασίλειο πραγματο-ποιεί αυτή την περίοδο μία αναθε-ώρηση των αρμοδιοτήτων της Ευ-ρωπαϊκής Ένωσης και επεξεργάζε-ται το ενδεχόμενο ανάκλησης ορι-σμένων εξ αυτών. Πρόκειται για την αρχή μιας σταδιακής αποχώρησης από την ΕΕ;

“Σίγουρα ευελπιστώ πως όχι. Η παρουσία των Φιλελεύθερων Δημο-κρατών στην ηγεσία του Ηνωμένου Βασιλείου αποτελεί εγγύηση κατά του ενδεχόμενου αποχώρησης. Σε περίπτωση που οι Συντηρητικοί εξασφάλιζαν την αδιαμφισβήτητη πλειοψηφία των εδρών στο Κοινοβού-λιο, θα διεξήγαγαν δημοψήφισμα το οποίο ενδεχομένως να οδηγούσε στην αποχώρηση του Ηνωμένου Βασιλείου.”

important, however, to show that the policies pursued are those of the EU and not simply of the German government.”

f Is Germany’s energy transition, i.a. phasing out nuclear power, biofuels, the Renewable Energy Act, more a model or caricature for Europe’s na-tions?

“The policies should be models for other countries. The dangers posed by

man-made climate change are now far too great to continue with ‘business as usual’. Humankind has a duty to future generations of responsible stewardship of the planet we inhabit.”

f Finally, a look into the future: how will the European Union look like in the year 2020 and will the European single currency still exist?

“I believe we will have emerged from

the periods of recession and low growth engendered by the 2008 financial tsu-nami. The EU will be more united and the euro will be thriving. But I think we are in for a difficult ride between now and 2018 and that keeping a cool head will be essential.”

source: Interview published on the website www.fnf-europe.org of the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom, 7. November 2013

* Η μετάφραση έγινε από την Βικτώρια Λαμπροπούλου, Μεταπτυχιακή Φοιτήτρια Νομικής Αθηνών.

Ε Π Ι Κ Α Ι Ρ Ο τ η τ Α 15

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

Interview published on the website www.fnf-europe.org of the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom, 7. November 2013

f Η Καγκελάριος της Γερμανίας έχει κατακριθεί σκληρά, κυρίως στην Ελλάδα, για τα αυστηρά μέτρα λι-τότητας και τη γερμανική επιρροή στην αντιμετώπιση της κρίσης× Έχετε την εντύπωση ότι η Γερμα-νία γίνεται αντιληπτή ως υπερβο-λικά κυριαρχική ως προς τα υπόλοι-πα κράτη-μέλη;«Πρόσφατη έρευνα του Ινστιτού-

του Pew δείχνει ότι η κοινή γνώμη σε όλα σχεδόν τα κράτη- μέλη- συμπε-ριλαμβανομένων της Κύπρου, της Ελλάδας, της Πορτογαλίας και της Ιρλανδίας- εξακολουθούν να τίθενται υπέρ των περικοπών στις δημόσιες δαπάνες για τη μείωση του εθνικού χρέους. Ο σεβασμός για το πρόσωπο της AngelaMerkel σε όλη την Ευρώπη είναι αξιοσημείωτα υψηλός. Οι διαμαρ-τυρόμενοι της αριστεράς αποτελούν μειοψηφία. Μεγαλύτερη ευρωπαϊκή ολοκλήρωση είναι σημαντική, παρό-λα αυτά, ώστε να καταδειχθεί ότι οι επιδιωκόμενες πολιτικές είναι αυτές της ΕΕ κι όχι απλά της γερμανικής κυβέρνησης.»

f Η ενεργειακή μετάβαση της Γερμα-νίας λ.χ. η σταδιακή κατάργηση της πυρηνικής ενέργειας, τα βιοκαύσι-μα, η Πράξη για τις Ανανεώσιμες Πηγές Ενέργειας περισσότερο ένα μοντέλο ή μία καρικατούρα για τα κράτη της Ευρώπης;

«Οι πολιτικές δράσης πρέπει να θέτουν παράδειγμα για άλλες χώρες. Οι κίνδυνοι που προκαλούνται από την τεχνητή κλιματική αλλαγή είναι υπερβολικά σπουδαίοι για να συνεχί-ζουμε με το μότο «business as usual”. Η ανθρωπότητα υπέχει καθήκον έναντι των μελλοντικών γενεών να διαφυλάξει υπεύθυνα τον πλανήτη τον οποίο κα-

τοικούμε.» f Τέλος, μία ματιά στο μέλλον: Ποια θα είναι η εικόνα της Ευρωπαϊ-κής Ένωσης το 2020 και θα υπάρ-χει ακόμα το ενιαίο ευρωπαϊκό νό-μισμα;

«Πιστεύω ότι θα έχουμε ξεπεράσει περιόδους ύφεσης και χαμηλής ανά-πτυξης προκληθείσες από το οικονο-

μικό τσουνάμι του 2008. Η ΕΕ θα είναι ακόμα πιο ενοποιημένη και το ευρώ θα ευδοκιμεί. Αλλά θεωρώ ότι μας περι-μένει μια δύσκολη περίοδος από τώρα ως το 2018 και το να κρατήσουμε τη ψυχραιμία μας θα είναι απαραίτητο.»

Η συνέντευξη πραγματοποιήθηκε τον Σεπτέμβριο του 2013.

Α Π Ο Ψ Ε Ι ς16

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

Regional integration in Europe Some thoughts about lessons from outside

by Victor Sukup*

European regional integration has long been hailed as an example for similar experiences worldwide. This was espe-cially the case in latin america, a region characterized by the existence of -altogether twenty- more or less small national markets limiting seriously their possibilities of industrial development, and which has seen a great num-

ber of such initiatives since the 50s when the European Economic Community (EEC) was launched. Some of them, like the latin american Free Trade association and the Central american Common Market (alalC and MCCa in their Spanish acronyms), seemed quite successful for several years before they went into trouble due to internal differences and the unequal distribution of benefits and costs, benefitting especially the bigger and more advanced countries and the multinational enterprises. anyway, the dynamism of European economies until the mid-70s –in fact, largely due to the reconstruction boom and cheap oil as well as keynesian and social democratic economic policy- seemed to justify the imitation of the EEC model for creating larger markets by breaking obstacles to commercial exchange and thus enhanc-ing the international competitiveness of regional blocs.

later, after the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system and the “oil shocks”, the multiple difficulties of

what finally became the European Union in 1993 cooled down the en-thusiasm for European examples,

while soon new initiatives like the Mercosur (Southern Common Mar-ket) seemed for some years to be quite

* Economist and politologist specialized in European affairs. Professor of international economy at the University of Buenos Aires in the 90s and European Commission official from 2000 to 2012.Author of several books on Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, especially about “Europe and the globalization”, Buenos Aires, 1998.PhD thesis on regional integration and development in Latin America, University of Paris-III, 1987.

Πηγή: www.spiegel.de

Α Π Ο Ψ Ε Ι ς 17

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

an adequate answer of middle-income latin american countries to the globalization challenge by creating also larger regional markets within a somewhat ambiguous context of “open regionalism”. The North american Free Trade association (NaFTa) at-tracted crisis-shaken Mexico, with very mixed results including a boost in industrial exports, aggravated social polarization, bankruptcy of millions of small peasants and mass emigration. at the same time, East and South East asian countries showed increasingly other forms of integration into greater regional (asian-Pacific, in this case) and world markets able to develop much more real dynamism while also contributing more efficiently to the satisfaction of key social objectives like poverty reduction.

Realistic reflections had certainly already warned long ago against over-enthusiasm with regional integration as a means of achieving by itself rapid economic progress. of course, classi-cal authors had introduced very useful basic concepts in the ‘50s, like trade creation and trade diversion (Jacob Viner), direct and indirect effects of integration (Jan Tinbergen) and pôles de croissance as geographical development engines (François Per-roux). But as Sidney dell stated in his still very recommendable book published in 1963 on Trade blocs and common markets, politicians used in fact to emphasize the expected eco-nomic gains while economists often preferred to underline the political advantages of the EEC in overcoming centuries-old national rivalries. and while economies of scale and special-ization, increased competition and the principle of “together we are stronger” are certainly factors of great poten-tial gains, they should, dell said, be thoroughly relativized: already quite open economies like those of Western

Europe could possibly not reach really significant gains from all that, while governments and unions would lose power, new oligopolies on regional scale could reproduce and even ag-gravate the problems posed by such oligopolies on a national level, and the group’s enhanced economic and nego-tiation power risked to be used more against Third World countries than against any of both super-powers. So-viet economists like abram Frumkin used to emphasize, not without some reason, “inter-imperialist rivalries” and contradictory interests between the big international monopolies behind the many tensions and contradictions of capitalist integration initiatives. Fritz Machlup, then president of the International Economic association, recalled around 1976 that it should not be forgotten that regional integration must always be seen also in the light of simultaneous other integration processes on national and interna-tional scale. and a quarter of a century after dell’s book, just when the EEC was taking a new start to become the EU and prepare the future monetary union, French “Green” economist alain lipietz found, in an article for the business weekly l’Expansion, in 1988, that precisely the smaller countries which had stayed outside the EEC like Switzerland, austria and Sweden -even being narrowly linked to it economically, but not part of its machinery- showed clearly better in-dicators in employment, GdP growth and other important fields. and now, another quarter of a century later, Eu-rope’s richest countries -Switzerland, Norway and Iceland- show less interest than ever in joining the Union, while poor and backward Balkan and others like Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia are or want to be candidates or hesitate a lot between the EU and Russia, like the largest of them, Ukraine.

For less developed European countries, can EU integration be the way forward?

The accession of the southern member states to the EEC in 1981 and 1986 was certain-

ly more politically than economi-cally motivated and should therefore be seen especially in this light: as an economist underlined, with the acces-sion of Greece, Spain and Portugal, the combined GdP of the Community had expanded by 10%, its population by 22%, the number of people working in the agricultural sector by 57% and its regional problems „so to say by 100%“. But important economic and social progress seemed anyway be made, thanks not only to dynamic changes under reform-minded post-dictatorial leaders like the several-terms-long so-cial democratic PSoE government of Felipe González in Spain (1982-96), but also to the accession to a large market, abundant capital inflows and substan-tial aid in the form of regional and “co-hesion” policies as well as agricultural subsidies. So the new southern mem-ber states, as well as also very back-ward Ireland, became effectively nota-bly more “equal” to the core members of West European integration, espe-cially in terms of GdP per capita, but also with respect to industry and phys-ical infrastructures, especially motor-ways which improved considerably the communications, like between France and Spain, maybe with some negative effects on the fragile Spanish national cohesion.

Ireland was a spectacular, albeit very specific case with particular cir-cumstances like massive US direct investment attracted by low taxes combined with important national efforts in education and state guid-ance and generous EEC/EU subsidies

Α Π Ο Ψ Ε Ι ς18

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

reaching, as in the case of Greece, up to 3-4% of GdP: around 15 years after EEC accession it began to move from being originally (at its accession in 1973) by far the poorest member state to be, after another 15 years, the rich-est one except tiny luxemburg in GdP per capita terms.

Spain also moved rapidly forward to become a modern industrial coun-try like Italy, Portugal and Greece notably less but also reduced, thanks largely to EU “generosity” -the term might be possibly put without brack-ets-, the distance to core EU member states, even if there were also a high price to be paid for this, as was the rapidly increasing domination of foreign business and capital evict-ing national ones. anyway, the euro crisis later showed that much of that progress was uncertain in a long-term view and rather the result of a credit bubble than that of genuine rise on the ladder of development levels. and the euro proved being, overall, much more favorable to Germany and other Northern member states than to the southern partners which lost rapidly competitiveness, after the introduc-tion of the common currency, due to the excessive affluence of capital flows reinforcing inflationary pressures and speculative tendencies, while the “Northerners” benefitted from a relatively low currency exchange rate which favored greatly their exports …

For the former Eastern Bloc countries, the balance of over 20 years of neo-capitalist conversion and progressive absorption in the EU is far from clear. Modernization of production processes and even more of consumption patterns has taken place, Western-style democracies have been established, and after a steep fall in GdP in the first years economic growth has been comparatively sat-isfactory. But social inequalities and

marginalization have risen strongly, as the drama of the Romas tell us, mass emigration has for instance reduced Bulgaria’s population by around one fifth, political tensions have given rise to powerful extreme-right groups like furiously anti-Semitic Jobbik in hun-gary. Even in the relatively prosperous Czech Republic, political instability and europhobic attitudes, as well as heavy corruption scandals, are noto-rious. all this and other phenomena show clearly that integration into the Western bloc has not really been a journey to prosperity and welfare for everybody and that the overall balance is not too convincing. anyway, if “real socialism” was certainly far from suc-cessful in historical perspective and had the well-known aspects of harsh political repression, excessive bureau-cracy etc., the later experience of “real capitalism” of the former Eastern bloc countries joining the EU does not seem to have been, up to now, a solid key to real rapid and balanced economic and social progress: not only some nostalgics of communism do not like very much that other “Union” which now dominates them, imposing its not always adequate prescriptions, and it is clear that the EU will remain for some more time being destabilized both by a deep North-South contradiction and an equally serious West-East divide. as an editorial put it, “Eastern Europe is failing to catch up with the west”.

Lessons, experiences and examples from outside

If there are highly interesting pos-itive and, as indicated, not-so-positive lessons from Europe for

others, which should certainly be re-considered with realism in the light of all this, we should also have a look on possible examples in the opposite direction. There are some good and

others not-so-good or even quite un-convincing experiences of regional in-tegration, which are all also very useful for the overall picture.

For instance, the Soviet Bloc group-ing known as CMEa or CoMECoN aimed to organize a kind of “socialist international division of labor” based on “internationalism” and solidar-ity of the socialist bloc, but backward Rumania did not like to be reduced to its role as a producer of agricultural machinery while richer partners like Czechoslovakia and East Germany were hardly enthusiastic in giving substantial aid to the poor develop-ing countries Mongolia, Cuba and Vietnam which also joined the group. Even so, a correct overall balance of CoMECoN might also show that the “communist common market”, as some Western analysts called it, was able to reach some real industrial and social progress in its member coun-tries -most of which had been very backward in European terms- and a certain reduction of their intra-bloc differences in levels of development. The same can certainly be said about the logically dominating leader coun-try which covered nearly one sixth of the earth and had a population much larger than all the partners together: the evolution of intra-Soviet levels of development showed, more than an “empire” exploiting its internal colo-nies, rather a kind of large technocratic machinery which was able to promote important industrial development and social progress also in very backward regions in Central asia, not without at least one big ecological disaster. on the other hand, the most developed Soviet republics in the Baltic region, also its most Western parts in geographical and cultural terms, became the most unsatisfied and initiated therefore the break-up of the multiethnic country which had received, nearly unchanged

Α Π Ο Ψ Ε Ι ς 19

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

in its borders, the difficult and complex inheritance of the Czarist empire.

Maybe the main lesson -on national and regional level- for Western Europe is that central planning can be relatively efficient in itself -whatever is to be said about the tremendous political and human rights aspects of Stalinism, Maoism, Titoism etc.- in the very initial stages of industrial development, also for raising the education level and promote womens’ rights, but much less in fur-ther developed countries, as shown by the Prague spring of 1968, the Solidarnosc-movement in Poland a dozen years later and finally the break-up of the bloc and even of the Soviet Union itself beginning in 1988. Secondly, the preservation of environment was hardly a priority, despite the absence of large private oligopolies pursuing their egoistic corporate interest with-out regard for such things, even less than in advanced capitalist countries where it became increasingly a subject of numerous citizens’ concern. But there might be also a third one: must certainly there be more efficient and more recommendable ways of régime change than those, more based on the “Washington consensus” than on the “European social model”, experienced in the following years in the former Soviet Bloc and in the former USSR itself, with enormous and often unnec-essary high social and other costs, all this preserving or even consolidating a new West-East-divide inside the EU, as mentioned before.

Turning to a very different region, we might consider that the Caribbean, with its more than a dozen of very small and even microscopic states,

some of which with less than 100.000 inhabitants, is the one region which really calls for important progress towards the integration of their weak economies. There have been some steps forward in four decades of the Caribbean Community (CaRICoM), but mostly tiny islands with their own quite differentiated identities -not only between English-, French-, Spanish- and dutch-speaking islands-, hardly complementary economies and high transport costs have certainly also enormous difficulties in realizing significant steps towards regional integration. Even so, there are some interesting initiatives like the Univer-sity of the West Indies, with campuses in several English-speaking member states, and joint diplomatic representa-tions, which could be useful examples for others, even in Europe. For in-stance, culture, education and better understanding between European people have undoubtedly benefited from millions of Erasmus scholarships, but besides the Colleges of Europe in Bruges (Belgium) and Natolin (Poland) and the European University Institute

of Florence there should be more of that kind of initiative if better under-standing between the people of Europe is to be promoted in a way to efficiently fight rising euroskeptical and even outright europhobic tendencies.

Joint diplomatic representations are becoming common practice and the newly established European

External action Service is supposed to be something like that. But there is still a long way for a kind of joint foreign policy and of “speaking with one voice” in world affairs, as shown by the chronic cacophonies in the relations with the USa, Russia or China, or even with the neighboring arab-Islamic world. The same thing can be said, it is true, of the Caribbean countries, where some maintain relations with Taiwan and others with China, some have sided with Venezuelan-Cuban sponsored “socialist” alBa group -with some risks for their crucial links to the USa and Europe- while others did not …

There are many other questions around the complicated and often con-

Α Π Ο Ψ Ε Ι ς20

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

troversial integration problématique, like the necessarily very differenti-ated treatment of the EU’s outermost regions (régionsultrapériphériques which are the French overseas de-partments, the Canary Islands, the azores and Madeira; the island regions generally, like very mountainous and sparsely populated Corsica and the numerous, often very little populated Greek islands; the difficult “integra-tion” in one large region of a “rich” oil exporting country like Venezuela and a poor mountainous one like Bolivia; the “integration” of an “underdevel-oped” country like Mexico with two of the most developed ones, the possible marginalization of far-away provinces outside the main developed core re-gions etc.

of course, we should also take lessons from East asia. Europe can learn a lot not only from millennia of Chinese civilization and wisdom but also from China’s recent rebirth as an economic superpower, following previous examples of Japan, korea and Taiwan particularly that applied their recipes intelligently - not without big problems and mistakes, inevitably- to the circumstances of its enormous population and territory. They all show that dynamic integration into world markets can also be realized without formal regional markets and integration mechanisms, and that over-reliance on market mechanisms is certainly not the most promis-ing policy. Combinations of market mechanisms with different forms of strong state intervention including important protectionist measures are obviously an alternative which appears to have often been very successful in obtaining rapid economic growth and at the same time important social im-provements like the rapid elimination of illiteracy and a sharp reduction in poverty levels.

all this certainly does not mean that Europe should abandon its regional integration goals, but that it ought certainly to rethink them thoroughly and at the same time be much more imaginative in its choices of economic and industrial strategy, striking an imaginative and construc-tive balance between market forces and some kind of government inter-vention, on national and on European levels. after all, integration projects are always the result of one basic real-ity: if david Ricardo’s classical theory of comparative advantages justifying worldwide unrestricted free trade were really applicable such as proposed in his Principles …, no free trade asso-ciation or common market of any sort would be useful; and if Friedrich list’s idea of the convenience of temporary, selective and rather moderate protec-tionism against third countries were always suitable as he rightly viewed for the case of the German states on their way to national unity, but much less for isolated smaller countries, no integra-tion project would have any sense ei-ther. What can be concluded from this is that all regional integration projects always need for obvious reasons some measure of protectionism or prefer-ence communautaire in EU terms against too powerful third countries, including the resulting elements of state interventionism, and should not be based on a fundamentalist view of market mechanisms as the practically sole guiding principle of economy.

Is Germany, after all, the key prob-lem of the European Union?

By the end of 2013, rather be-latedly, the European Com-mission, after several warning

shots coming from other sides in-cluding the IMF and the US Treasury complaining about probable deflation-

ary effects of Germany’s efficiency on European recovery and world trade, began an inquiry into the recurrent “excessive” German current account surplus, which had reached more than 6% of GdP for several years now. There are arguments to judge Germany at least partially responsible of the en-tire euro problem and the commercial deficits of its partners: the lack of a le-gal minimum salary and its large low-salary-sector contribute to the Union’s imbalances, as shown by the meat-packing industry where danish and French enterprises have been pushed into bankruptcy by “unloyal” German competition based on very low salaries paid to foreign workers on those “mini-jobs”. as a German automobile worker said in a cartoon, they had to export the cars because they could not afford to buy them themselves … If Germa-ny runs a heavy surplus, anyway, other countries must of course have deficits, and the big question is if there is not an important responsibility of Germa-ny in the southern countries’ deficits and resulting crisis. apparently, yes, due also to the simultaneous capital flows from German (and other) banks southwards in the years 00’ which fu-elled the consumption and real es-tate speculation there, the resulting higher inflation and the loss of com-petitiveness. according to one article, Germany has since 2011 the highest surplus of any current account (238 billions of $ against 193 for China in 2012), its unitary labor costs have only risen by 4% since 2000 against 23% in France, 19% in the eurozone and 16% in the USa, and from 2009 to 2013 the percentage of people living under the poverty level rose from 12.2 to 15.9 in Germany, against from 13 to 13.8 in France. It would be over-simplification to talk of one “villain” and the others as “poor victims”, but responsibilities of the euro crisis and the resulting EU ex-

Α Π Ο Ψ Ε Ι ς 21

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

istential doubts are certainly divided.on the other hand the Germans

can be right in defending the useful-ness of their past liberal reforms, or of some of them, and in emphasizing that their high competitiveness in countries like China -Germany; with 45% of EU exports to China and 21% of EU imports from there in the first semester of 2013, has practically alone a trade surplus with it- is also welcome for the entire EU, reducing thus its huge bilateral deficit with the Eastern giant. and why should Germany be sanctioned, after all, they ask, for its higher efficiency in indus-trial innovation, vocational training and successful R&d efforts, which contributes greatly to avoid the entire bloc’s fall into irrelevance in terms of international industrial competitive-ness? Should we, maybe, forbid our enterprises like Siemens or Mercedes to export to China?

The discussions will certainly last for several more years, with these and other arguments, but three aspects must also be taken into account: a), there are always some problems with the strongest or largest member state of a regional group, be it Brazil in Mercosur, Nigeria in West africa or the USa in NaFTa, all much more dominating economically and demo-graphically than Germany in their respective group; b) historical reasons make the German case particularly sensitive, as shown by recent reac-tions in Greece calling for German reparation payments for its wartime crimes in the country and of others accusing the Germans of dreaming of some kind of “Fourth Reich”; c), if the EU mechanisms for convergence between development and income levels seem to have worked reasonably well in the 80s and 90s, this has not been the case in later years: an ill-conceived currency union, far from

bringing an “ever closer union”, caused a Northern-credit-fuelled speculation and consumption bubble in the south (and in Ireland) aggravating notably the distances between “richer” and “poorer” member states and in the end the resulting euro crisis which benefit-ted in fact also Germany thanks to a still relatively undervalued currency -and now also the very low interest rates for a country seen as refuge haven for capital looking for security-, and the other supposedly “virtuous” countries Netherlands, austria and Finland …

Whatever the conclusions about all this might be, it is obvious that the rig-id EU austerity policy towards Greece and the other peripheral countries, largely dictated by Germany, appears as a disastrous social, political and also economic failure which has put the whole eurozone and even the EU on a road to a maybe inevitable disintegra-tion. What remains to be seen is less if, as some illusionists try to convince the public, that the recipe is finally working and that those countries are on the road to recovery, than if a more adequate reform policy can be put into practice before it is too late, as should be favored by better understanding of the realities and the advisable change of strategy by the German government and the technocratic machinery of Brussels.

An interesting “exotic” case which might give some good ideas: the Andean Pact

as the new Pope Francis said right after his election, his colleagues of the conclave had

found the new chief of the Catholic Church “at the end of the world”. May-be something similar could be useful also in economy, or more precisely in the field of regional integration.

looking around the globe, there seems to exist, finally, one rather exotic experience which could de-serve particularly to be analyzed: the andean Pact founded in 1968. despite the obvious underdevelopment and specificities of the andean countries from Venezuela to Chile, there are three ideas which seem to be useful to be taken into account, even if the andean experience has not been suc-cessful, if the European realities are of course hardly comparable to those of South america, and if world realities have also obviously changed a lot in the last 45 years. The andean Pact, today called andean Community but sharply divided now between oppos-ing political options, was certainly not successful in the long and even middle term due to a series of circumstances -impact of the oil shocks, political changes towards right-wing regimes, enormous socio-economic differences between “haves” and “have-nots”, ex-tremely high transport costs etc.-, but even so its basic ideas deserve to be analyzed as potentially useful ingredi-ents of any other regional integration project.

Three fundamental elements char-acterize the andean integration model in its initial years, when reformers where largely dominating the region’s politics in Peru, Chile etc.:

a. Rather than letting “market mechanisms” determine all essential economic development, Sectorial In-dustrial development Programs were prepared in order to distribute new industries like that of cars and other machinery more evenly between the member states, avoiding their concen-tration in the most advanced or richest countries of the group, Venezuela and Colombia;

b. For Bolivia and Ecuador, of-ficially recognized as economically less developed countries of the group,

Α Π Ο Ψ Ε Ι ς22

ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΗ • τ. 90 • 3o ΤΡΙΜΗΝΟ 2013

special measures allowed slower intra-group tariff elimination and other advantages in order to expose their enterprises less brutally to the nascent regional common market;

c. The multinational enterprises were asked to stay out of certain sectors like publicity, communica-tion and local transports, and their profit remittances should not exceed a “reasonable” level, while andean Pact member countries agreed on a com-mon policy towards them in order to avoid ruinous tax and other competi-tion in attracting them.

These three aspects can be seen separately or combined; but it appears that they give quite interesting an-swers to some basic problems suffered by all regional integration projects: the balance between market mechanisms and state intervention, the specific dif-ficulties of the less developed member countries, and the controversial role of multinationals. as analyzed by one specialist, “common markets in developing countries” need certainly some state guidance and even intra-bloc positive discrimination, and after decades of EU integration and the euro crisis we might conclude that in Europe it is not different. Moreover, there are some useful hints here for more constructive and balanced North-South and EU-Third-World-relations generally, for which there is a lot to do in order to improve its policies, and for how to initiate really the very necessary “energy transition” to a low-carbon economy, probably the main key for the salvation of what Jeremy Rifkin called, only one decade ago, the European dream …

Some preliminary conclusions

If we look at today’s acute and ap-parently unresolvable EU’s prob-lems, we see the interest in taking

some of all these lessons, examples

and ideas very seriously. obviously Europe’s, or rather the EU’s long-last-ing stagnation without perspectives of improvement, the rapidly rising popu-lar frustrations -with their inevitable consequences of a dangerous rise of extreme-right and europhobic popu-lism in many EU countries, especial-ly in countries as different as Greece, France, austria and hungary- due to a deteriorating social reality and the in-capacity of political leaderships to find adequate solutions, and the still loom-ing bankruptcy of the euro system, are all largely due to three factors:

a) the lack of any “industrial policy”, together with coherent energy and transport policies etc., to counter the rising difficulties of competing successfully with other economic powers like the US and China, and the incapacity of determining some kind of a convenient coherent foreign trade policy including some useful measures of protectionism; at the same time, Eu-rope’s role as one of the world’s leaders would certainly have to be based on a decided emphasis on really “sustain-able development” and a thorough redefinition of what is real progress, rejecting the superficial and misguided ideology of blind GdP growth and preparing seriously a constructive and imaginative “energy transition”;

b) the structural problems of its “less developed countries” like Greece and Portugal -and also Spain, Italy etc.- which are seriously undermin-ing the cohesion of the group by the looming danger of an explosion of the common currency and maybe the Union itself; and

c) the often fierce competition in attracting investments at any price by tax breaks and similar methods, as exemplified by several countries like Ireland, Slovakia and Estonia.

It thus appears that the triple idea of that other regional group created

nearly half a century ago in a very different historical and geographic context could provide a good start-ing point to overcome the EU’s most dangerous crisis of which no way out is to be seen right now; at the same time, the East asian countries show some very interesting examples of how to find more balanced and more efficient ways to combine market mechanisms with an active role of the state in view of confronting the problems of the present and in preparing the future. otherwise, as happened precisely in the EU, the market, from framework for its economic functioning, becomes gradually the very purpose of the union, losing thus any middle- and long-term view of its possible and desirable future.