ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

-

Upload

wiss-mahfouz -

Category

Documents

-

view

223 -

download

0

Transcript of ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

1/96

Energy Sector Management Assistance Program

Regulatory Reviewof Power Purchase

Agreements: A

Proposed Benchmarking

Methodology

Formal Report 337/08

October 2008

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

2/96

Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP)

Purpose

The Energy Sector Management Assistance Program is a global knowledge and technical assistance

partnership administered by the World Bank and sponsored by bilateral official donors since 1983.

ESMAPs mission is to assist clients from low-income, emerging, and transition economies to secure

energy requirements for equitable economic growth and poverty reduction in an environmentally

sustainable way.

ESMAP follows a three-pronged approach to achieve its mission: think tank/horizon-scanning, opera-

tional leveraging, and knowledge clearinghouse (knowledge generation and dissemination, training

and learning events, workshops and seminars, conferences and roundtables, website, newsletter, and

publications) functions. ESMAP activities are executed by its clients and/or by World Bank staff.

ESMAPs work focuses on three global thematic energy challenges:

Expanding energy access for poverty reduction;

Enhancing energy efficiency for energy secure economic growth, and

Deploying renewable energy systems for a low carbon global economy.

Governance and Operations

ESMAP is governed and funded by a Consultative Group (CG) composed of representatives of Aus-

tralia, Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Iceland, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, the United

Kingdom, the U.N. Foundation, and the World Bank. The ESMAP CG is chaired by a World Bank Vice

President and advised by a Technical Advisory Group of independent energy experts that reviews

the Programs strategic agenda, work plan, and achievements. ESMAP relies on a cadre of engineers,

energy planners, and economists from the World Bank, and from the energy and development com-

munity at large, to conduct its activities.

Further Information

For further information or copies of project reports, please visit www.esmap.org. ESMAP can also be

reached by email at [email protected] or by mail at:

ESMAP

c/o Energy, Transport and Water Department

The World Bank Group

1818 H Street, NW

Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A.

Tel.: 202-473-4594; Fax: 202-522-3018

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

3/96

Energy Sector Management Assistance Program

Formal Report 337/08

Regulatory Reviewof Power Purchase

Agreements: A

Proposed Benchmarking

Methodology

John Besant-Jones

Bernard Tenenbaum

Prasad Tallapragada

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

4/96

Copyright 2008The International Bank for Reconstruction

and Development/THE WORLD BANK GROUP1818 H Street, N.W.Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A.

All rights reservedProduced in the United States of AmericaFirst Printing October 2008

ESMAP Reports are published to communicate the results of ESMAPs work to the development communitywith the least possible delay. Some sources cited in this paper may be informal documents that are not readilyavailable.

The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this report are entirely those of the author(s) and

should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, or its affiliated organizations, or to members of itsboard of executive directors or the countries they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracyof the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility whatsoever for any consequence of theiruse. The boundaries, colors, denominations, other information shown on any map in this volume do not implyon the part of the World Bank Group any judgment on the legal status of any territory or the endorsement oracceptance of such boundaries.

The material in this publication is copyrighted. Requests for permission to reproduce portions of it should besent to the ESMAP manager at the address shown in the copyright notice. ESMAP encourages disseminationof its work and will normally give permission promptly and, when the reproduction is for noncommercialpurposes, without asking a fee.

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

5/96

Acknowledgments v

Abbreviations and Acronyms vii

1. Introduction 1

Other Possible Regulatory Approaches for Power Purchases 3

Suggestions for a Possible Way Forward 5

2. Purpose of Regulatory Review of PPAs 7

Basic Purpose of Regulatory Review of PPAs 7Importance of Regulatory Review of PPAs 8

3. The Proposed Process for Review of PPAs in Nigeria 9

Legal Authority 9The Proposed Regulatory Review Process 10

NERC Will Review a PPA, Rather than Approve It 10NERC Is Proposing a Two-stage Regulatory Process for the Review of Generation Licenses

and Associated PPAs 10The Seller Files the Application for a PPA Review, Accompanied by a Declaration by the Purchaser 11The Seller and Purchaser Must Use Plain English for Their Answers 11NERC Will Select an Independent Party to Analyze the Sellers Answers, and the Seller

and Purchaser Will Pay for This Service 12NERC Proposes to Make Public the PPA, the Sellers Answers to the Questionnaires and

Tables, and NERCs Comments on the PPA 12NERC Does Not Intend to Review All PPAs 12

Possible Further Development of the Regulatory Process 13NERC Will Examine the Scope for a More Limited Regulatory Review 13NERC Will Develop a Database of PPA Terms and Conditions for Benchmarking Future PPAs 13

4. The Proposed Methodology for the Review of PPAs in Nigeria 15

Methodological Issues 15

Approach to Assessment of PPAs 15Assessment of the Completeness of an Applicants PPA 17

5. Average Purchase Price Analysis 19

Structure of Power Purchase Price 19Purchasers Price versus Sellers Cost 20Benchmarking the Average Purchase Price of Power 21Affordability of the PPA for the Purchaser 21

6. Risk Assessment 23

Analysis of Risk Factors 24Assessment of Risk Exposure 25

iii

Contents

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

6/96

7. The Price-Risk Trade-off Approach to Assessing PPAs 27

Annex 1 Questionnaire for Computing the Average Purchase Price of Power Under

a Power Purchase Agreement for a New Fossil-Fueled Generation Plant 29

Annex 2 Summary of Key Factors Affecting a Power Purchase Agreement for aNew Fossil-Fueled Generation Plant 35

Annex 3 Purchasers Declaration About Affordability of Its Payment Obligations Under a

Power Purchase Agreement for a New Fossil-Fueled Generation Plant 37

Annex 4 Questionnaire on Risk Allocation Under a Power Purchase Agreement for aNew Fossil-Fueled Generation Plant 39

Annex 5 Table for Risk Assessment of a Power Purchase Agreement for a New

Fossil-Fueled Generation Plant 51

Annex 6 Illustrative Risk Assessment of a Power Purchase Agreement for a New

Fossil-Fueled Generation Plant 57

Annex 7 Purchasers Declaration About Sellers Responses to Questionnaires and TablesUnder a Power Purchase Agreement for a New Fossil-Fueled Generation Plant 63

List of Formal Reports 65

Boxes

Box 5.1 General Formula for Calculating the Average Purchase Price Under a PPA 20

Figures

Figure 4.1 Overview of NERCs Proposed Approach for Reviewing PPAs 16

Figure 4.2 Links between the Review Approach and the Questionnaires and Tables 17Figure 7.1 Price-Risk Trade-off Chart for PPAs 27

Tables

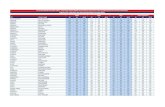

Table 1.1 Benchmarks Adopted by the Andhra Pradesh Electricity Regulator 3Table 1.2 Possible Approaches to Regulatory Review of Power Purchase Costs 4Table 4.1a Typical Main Clauses/Articles in a PPA for a New Fossil-Fueled Power Plant 18Table 4.1b Typical Main Schedules Annexed to a PPA for a New Fossil-Fueled Power Plant 18Table 6.1 Methodology for Risk Assessment 26

iv

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

7/96 v

This paper is an outgrowth of a notice of proposed rulemaking that was issued by the Nigerian ElectricitRegulatory Commission (NERC) in December of 2006. That document is now in the public domain ancan be downloaded at www.nercng.org. NERC has always viewed this project as simply the first stepof ongoing dialogue with regulated entities and their customer on how to acquire future sources opower supply that are efficient and fair to both sellers and buyers. The authors gratefully acknowledg

the financial and technical support of the Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP)

The World Banks assistance to NERC was made feasible by the active and ongoing support of itchairman, Dr. Ransome Owan, and the projects lead commissioner, Abimbola Odubiyi. Their sustaineassistance and encouragement was essential for bringing the project to fruition. The collaboratiobetween NERC and the Bank staff was intense. It was manifested in many hours of video and audiconferences and face-to-face meetings in both Abuja and Washington. The authors are grateful tChairman Owan and the NERC commissioners and staff for the opportunity to assist them and for theicomments and suggestions. We are especially grateful to Commissioner Odubiyi. He brought visionpersistence and intellectual integrity to the project. We believe that NERCs efforts are pioneering andcould be used by regulators elsewhere in Africa and other regions of the world. The authors extendtheir appreciation to the following peer reviewers: Beatriz Arizu de Jablonski, Tonci Bakovic, PankaGupta, and Scot Sinclair. Special thanks to Marjorie K. Araya (ESMAP) for coordinating the editingproduction and dissemination of the final report.

Acknowledgments

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

8/96

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

9/96

vii

CCAPACITY

Maximum Declared Availability of the FacilityC

NOMINALNominal Capacity of the Facility

CP Capacity Purchase ChargeCP

AVAverage Capacity Purchase Charge

CPCALC

Calculated Capacity Purchase Charge

CPGEN General and Administration Costs for the FacilityCPLEV

Levelized Average Capacity Purchase ChargeCP

INSURCost of all forms of Insurance for the Facility

CPINV

Investment component of the Capacity Purchase ChargeCP

OFFixed Operation and Maintenance Cost for the Facility

CPOTHER

Other Capacity Related CostsD

iAverage Annual Interest Rate on the Long-Term Debt

Dp

Proportion of Total Investment financed through Long-Term DebtE Energy Purchase ChargeE

AVEnergy Charge Payable at the expected date of commercial operation

ECALC

Calculated Average Energy Purchase ChargeE

ENERGY

Amount of Energy PurchasedE

FFuel Cost component of the Energy Purchase Charge

Ei

Target Pre-tax Average Return on EquityE

OVVariable Operation and Maintenance Cost for the Facility

Ep

Proportion of the Total Investment financed through EquityEPSR Act Electricity Power Sector Reform Act of 2005ESMAP Energy Sector Management Assistance ProgramF

calAverage Calorific Value of Fuel used in the Facility

Fconv

Average Energy Conversion Efficiency in the first full year of operation of theFacility

Fcost

Unit Cost of the Fuel in the first full year of operation of the Facilityi Seller s Weighted Average Cost of Capital

I Total Investment in the FacilityIPP Independent Power ProducerMYT Multiyear Tariffn Duration of the PPA (in years)N Number of payments due under the PPANERC Nigerian Electricity Regulatory CommissionNOPR Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

Abbreviations and Acronyms

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

10/96viii

Paux

Proportion of Energy Generated consumed in the FacilityP

AVAverage Purchase Price of power under the PPA

Pmin

Minimum Monthly Payment for EnergyPLF Plant Load FactorPPA Power Purchase AgreementPRG Partial Risk GuaranteeS Supplemental ChargesS

AVAverage Supplemental Charge

SSA Sub-Saharan Africa

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

11/96

Power purchase agreements (PPAs) are centralto the health of power sectors, particularlyin countries that have opted for single-buyermarket structure. The capital costs of electricity-generating plants often constitute a large share

of the final cost of power delivered to retailcustomers. In addition, in the case of thermalgeneration fueled by imported oil, input fuelcosts have experienced major escalationsbecause of large increases in world oil prices. Ifthe risk allocation and sale price in the PPA areone sided, the bulk supply price of power thatresults from the PPA may turn out to be veryhigh and economically unsustainable.

There are around 700 electicity-generationplants in developing countries that havebeen financed, constructed, and operated byindependent power producers (IPPs), of whicharound 28 are in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).Almost all the PPAs for these plants have take-or-pay features, and the price of power rangesbetween 4 cents per kWh to around 40 centsper kWh, depending on the fuel used.1 Mostof the utilities in Sub-Saharan Africa are notable to meet their financial obligations underthese PPAs. As a consequence, governmentsare often forced to meet this shortfall from theirgeneral revenues. This, in turn, often creates

an unsustainable macroeconomic burden. Itis therefore very important for developingcountries in general and SSA countries inparticular to develop effective mechanisms toevaluate PPAs.

1

Introduction1

Competitive procurement of bulk power canhelp to address this situation. But competitiveprocurements are still the exception rather thanthe rule in Sub-Saharan Africa.2 Full competitivebidding is generally feasible only when bidders

are bidding on a relatively standardized andwell-specified commodity and the potentialbidders are bidding on a single attribute (i.e.,price) or several attributes that can be scored ona relatively objective basis. Since the conditionsfor this type of bidding do not exist in mostAfrican countries, the best that may be possiblein the near future is some hybrid form of biddingthat combines elements of competition andnegotiation.

An additional complication in Africa isthat the buyer, usually a state-owned powerenterprise, is rarely commercially viable. Asa consequence, most IPPs are not willing tosign PPAs unless the PPA is also accompaniedby a government support package (such assovereign guarantees, tax holidays, escrowaccounts, currency conversion, repatriationof profits, protection against nationalization,and expropriation). Given the large amountsof money associated with PPAs, it is perhapsnot surprising that there have been widespreadallegations of corruption in purchases from IPPs

in Guatemala, Pakistan, Philippines, Tanzania,and Nigeria. It is not unknown for ministersand prime ministers to present a PPA as afait accompli to utility managers. There havealso been reports of utility managers being

1 See Gratwick and Eberhard, An Analysis of Independent Power Projects in Africa: Understanding Development and InvestmentOutcomes, University of Cape Town Graduate School of Business, Novemeber 2006, www.gsb.uc.ac.za/mir.

2 Idem.

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

12/96

REGULATORY REVIEW OF POWER PURCHASE AGREEMENTS: A PROPOSED BENCHMARKING METHODOLOGY

2

instructed to sign on the dotted line, withlittle or no opportunity to analyze the costs orrisks for the utility created by the PPAs. Giventhese ad hoc and nontransparent procurements, itshould not be surprising that there is often wide

variation in the costs of PPAs for similar projectsacross different countries.

In this context, Africas new regulatoryinstitutions can play a critical role. Though thePPAs are essentially bilateral contracts betweenutilities and IPPs, these bilateral contractswill have major financial implications for theconsumers that pay for the power in their retailbills or for taxpayers (who may or may not beelectricity consumers) who pay for the shortfallsthrough higher taxes.

A recent development in Africa is thatthe new regulatory statutes in a number ofAfrican countries now require the regulator toreview the prudence and reasonablenessof such purchases, as well as their effect on thepurchasing utilitys finances and retail tariffs.The interpretations of how this review shouldbe done vary from country to country. In somecases, regulators have chosen to approve ordisapprove PPAs. In other cases (such as inNigeria), they have chosen to advise the

government, the purchasing utility and theIPP on the implications of the PPA with issuingformal approvals or disapprovals. Under bothapproaches, the regulatory entity has to unpackthe PPA into several elements and examinethese elements individually. The regulatorsmay view the PPA from several perspectives:the reasonableness of costs, how the costscompare with other PPAs operating undersimilar environments, and the risk allocationto the various parties to the transaction. Suchreviews have usually been performed on an adhoc basis. This paper proposes a systematic approachto evaluating price and risk allocation in proposedPPAs.

This paper reports on a proposed methodologythat would facilitate a regulatory review of PPAsfor fossil-fuel plants by explicitly benchmarkingthem for price and risk allocation. As part of thisexercise, the energy unit of the Africa Region of

the World Bank (AFTEG), with support from theEnergy Sector Management Assistance Program(ESMAP) of the World Bank, collaborated withthe Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission(NERC) as part of the World Banks Nigeria

country engagement. Chapter 2 presentsthe rationale for regulatory review of PPAs.Chapter 3 describes the specific process thatwas proposed in Nigeria. The substantivemethodology described in this paper wasformally proposed by NERC in a December 2006Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NOPR). Thismethodology is described in Chapters 4 through7 and Annexes to these chapters. A NOPR is thewritten equivalent of a public consultation by aregulator. This paper supplements NERCs NOPR

in two ways. First, it provides NERC and thefederal government of Nigeria with a referencedocument that describes the technical details ofthe methodology proposed in the NOPR. Second,since many African countries besides Nigeria facethe challenge of getting balanced PPAs, the paperis intended to familiarize regulators, utilities, andother stakeholders with a methodology that maybe equally useful in their countries.Although themethodology was designed for regulatory review, itcould also be useful for utility managers that have

to evaluate competing offers of long-term powersupplies.Benchmarking can be performed on a

parameter-by-parameter basis, as has beendone in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh,or on an overall basis, as is proposed byNERC in its NOPR. Under the first approachthe benchmarking is highly disaggregated. Itrequires reviewing numerous specific technicaland commercial parameters. In AndhraPradesh, the regulator has revised proposedPPAs by mandating specific values for anumber of key parameters such as auxiliarypower consumption, open cycle or combinedcycle stabilization periods, the station heat rate,specific oil consumption and the plant loadfactor (PLF). In addition, the regulator has setfinancial norms for initial capital costs of theplants and for operating costs. Typically, suchreviews require reviews of financing charges,

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

13/96 3

Introduction

related escalation factors, as well as proposedformulas for dealing with future changes inthe cost of operating and maintaining theplants. The Andhra Pradesh regulator hasalso attempted to take account of inflation

and foreign exchange risk by capping theirmaximum effect on the PPA tariff. With respectto financing charges, these were reviewed bytaking into account the prevailing interest ratesat the time of financial closure. Additionally, thewholesale price index and the consumer priceindex were used to normalize the benchmarkedprices. Two criticisms of the Andhra Pradeshapproach, a regulator reviewing a PPA on aparameter-by-parameter approach, are that itleads to a high level of second guessing and

micromanaging and that it may fail to capturetradeoffs because of its focus on individualparameters. But its proponents argue that aregulator has no other choice when presentedwith a PPA that may have been negotiated byan inexperienced buyer or where there areallegations of corruption.

Table 1.1 summarizes the benchmark valuesmandated by the Andhra Pradesh regulator. 3

Other Possible

Regulatory Approachesfor Power Purchases

Benchmarking, whether performed on aparameter-by-parameter or overall basis, is notthe only tool available to regulators when facedwith the need for reviewing power purchasecosts. As can be seen in Table 1.2, regulatorsaround the world have adopted a variety ofapproaches in reviewing power purchase coststhat would affect the retail tariffs paid by captive

customers. The observed regulatory approachesseem to fall into two general categories: those thatrelate to regulating conduct of the buyer, seller, orboth, and those that relate to regulating outcomes.The benchmarking approach proposed by NERCfalls into the latter category. It does not examinethe process by which the PPA was brought forth.

3 Developing regulatory benchmarks-G.P.. Rao-Andhra Pradesh Electricity Regulatory Commission, India.

PPA Component Benchmark

Auxiliary powerconsumption

79%

Coal plant Stabilization period: 1.5%

Gas plant (open cycle) Subsequent period: 1.0%

Gas plant (combined cycle) Stabilization period: 3.5%

Subsequent period: 3.0%

Station heat rate Coal based plants: 2050 to 2350 kcal/KWh

Gas plants: 1850 Kcal/KWh

Specific gas consumption 2.0 ml/KWh

Plant load factor (PLF) 85%

Wholesale price index 60%

Consumer price index 40%

Rate of return 16% (subject to prevailing interest rates)

Incentive to investors A cap of 0.5% if 85% PLF was achieved (Deemed generationnot eligible)

Table 1.1 Benchmarks Adopted by the Andhra Pradesh Electricity Regulator

Source: Besant-Jones, Tenenbaum and Tallapragada.

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

14/96

REGULATORY REVIEW OF POWER PURCHASE AGREEMENTS: A PROPOSED BENCHMARKING METHODOLOGY

4

Instead, it focuses on the proposed outcomeas manifested in the prices and risk allocationembedded in the PPA. And it proposes a specificmethodology for benchmarking these outcomesagainst the terms and conditions in other PPAs

for fossil fuel IPPs (bottom line in Table 1.2).4The NERC approach is not the only possible

form of benchmarking. For example, regulatorsin Colombia and the Netherlands have attemptedto benchmark the overall prices paid bydistribution companies that arise from all oftheir short-, medium- and long-term purchases.Unlike NERC, the Dutch and Colombianregulators do not look at individual PPAs orindividual purchases. Instead, they comparethe overall average power purchase prices of

the different distribution companies under theirjurisdiction. These prices are the end result of amix of short-, medium- and long-term purchases.This type of benchmarking is feasible only if

there are a number of separate distributioncompanies under the regulators jurisdiction andthere is a relatively active and open wholesalepower market. Some have argued that suchcomparisons are not necessary if a distribution

company purchases power in competitivewholesale market. However, the regulatorypresumption is that even if the wholesalemarket is competitive, this, by itself, does notguarantee that different distribution companieswill all buy with equal skill. Moreover, thecompetitive wholesale market structures thatexist in Colombia and the Netherlands do notcurrently exist in Nigeria or elsewhere in Sub-Saharan Africa. In addition, the norm in Sub-Saharan Africa is one distribution company in

the country, or a distribution company that hasno control over its power purchases becauseall of its power supplies are acquired from anentity that is buying on its behalf. Therefore, the

Type Regulatory Action Observations

CONDUCT

Assist in negotiating PPAs Kenya (Second wave of IPPs)

Before or after the factregulatory approval of PPAs

Andhra Pradesh (India) and United States (1980s andearly 1990s) and Panama

Standardized/model PPA Proposed in Pakistan and India; must allow forexceptions

Mandated (competitive)procurement guidelines

Proposed in Laos and Florida

Independent procurementmonitor

Issue public reportsSoutheastern United States: the affiliate problem

PERFORMANCE

Administratively specify amaximum price

Chile: too lowPakistan: too high initially (did not benefit fromcompetition)Nigeria: proposed as the generation component of theMYTO

Tie maximum price tocompetitive power sales

Chile: maximum price in nonfree market can be nohigher than 15% of free market price

Benchmarking of overallpower purchase costs ofdiscos

Colombia and Netherlands; need multiple discos

Benchmarking of individualPPAs

Proposed in Nigeria (12/2006)

Table 1.2 Possible Approaches to Regulatory Review of Power Purchase Costs

4 See Arizu, Maurer and Tenenbaum. Pass Through Power Purchase Costs: Regulatory Challenges and International Practices. WorldBank, Energy and Mining Sector Board Discussion Paper No. 10, February 2004, www.worldbank.org/energy.

Source: Besant-Jones, Tenenbaum and Tallapragada.

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

15/96 5

Introduction

average price benchmarking approach usedin Colombia and the Netherlands is simply notfeasible, at least in the near term, for Nigeria andother countries in SSA.

Regulators need not be limited to using a

single approach. For example, NERC stated inits December 2006 NOPR that it was consideringadopting model PPAs (line 3) and mandatedcompetitive procurement guidelines, in additionto the PPA benchmarking proposed in theNOPR. NERCs underlying presumption isthat a combination of regulatory approachesthat examine both conduct and outcomes mayproduce a better result than a single approachthat is limited to benchmarking proposedPPAs.

Suggestions for aPossible Way Forward

If the December 2006 NOPR is viewed as Phase I,we think that it is important for NERC toconsider elements of a possible follow-up in aPhase II. Based on our discussions with NERCover the last several months, it appears that thereis now a consensus on the following possiblecomponents for a Phase II:

i. Model PPA: Develop a model PPA or PPAsthat can be used as the basis for vestingcontracts and that provides guidance forboth buyers and sellers for future long-termpower transactions in Nigeria.

ii. PPA benchmarking: Test the feasibility ofusing the PPA price and risk assessmentmethodology proposed in the December2006 NOPR.

iii. Competitive power procurement guidelines:Develop guidelines for Competitive PowerProcurement for future long-term purchasesof power by a single buyer or other entities(e.g., distribution companies) serving captive

customers.iv. Independent monitoring: Assess the

feasibility of using one or more independentmonitors for determining compliance withthe CPP guidelines.

The NOPR proposed a specific methodology.But it has yet to be tested on any PPAs actuallyused in Nigeria or elsewhere. So a criticalcomponent of any follow-up is the testing ofthe NOPR methodology on actual PPAs to

see whether it provides a workable regulatoryapproach, and, if not, to see how it should bemodified to make it workable (component ii).The rationale for the other components is thatNERC should not put all of its eggs in onebasket. As seen in Table 1.2, there are a varietyof regulatory approaches to encourage thesigning of efficient, fair, and sustainable PPAs.The three other components of Phase IIa modelPPA that could be used in vesting contracts,competitive power procurement guidelines, andindependent monitoring of compliance withthese guidelinesare techniques that have beentried or are under consideration by electricityregulators in other countries. If NERC concludesthat these are potentially useful approaches,The World Bank would be pleased to work withNERC funding Phase II technical assistance thatwould examine how these other approachesmight work in the current conditions in theNigerian power sector.

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

16/96

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

17/96

Basic Purpose of RegulatoryReview of PPAs

The overall purpose of a regulatory review ofPPAs is to ensure that the terms of the PPAs

are fair and balanced to all parties who willbe directly and indirectly affected by thesetransactions. In particular, the prices paid bypurchasers of power (typically a distributoror a single buyer) under the PPAs should becompatible with fair pricing to consumerssupplied with power procured under thePPAs. In addition, the prices received by sellersof power (typically an IPP) under the PPAsshould be sufficient to allow the sellers tofinance the development and construction oftheir generation facilities and to earn reasonablereturns on capital invested under efficientoperation of these facilities.

The regulatory review of PPAs discussedin this chapter covers the individual reviewof a PPA before it is signed by the parties tothis transaction (ex ante review).5 The Nigerianregulators current proposal is to evaluate thereasonableness of the prices, risk allocation, andother contract terms. Based on its assessment,the regulator may approve full passthrough ofpayments for power procured under the PPA to

retail customers, especially if its comments areproperly reflected in the signed PPA. Otherwise,the regulator may not allow full passthroughof these payments. Or, in the alternative, theevaluations may be strictly advisory and the realregulatory control may be a specified generation

7

Purpose of RegulatoryReview of PPAs2

component of an annually adjusted multiyeartariff that establishes the generation componentof a maximum nationwide retail price. Atpresent, it appears that NERC has adopted theadvisory approach with the real regulatory

control exercised through a proposed multiyeartariff (MYT) setting mechanismIn other countries, such as Guatemala,

Panama, and Nicaragua, the electricity lawsmandate competitive procurement for thedistributors, and the power purchase contractshave to be approved by the regulator before theprices can be passed through in retail tariffs. Oncethe contracts are approved, there is a usually aguarantee of full passthrough as long as noamendments are made to the contracts withoutregulatory approval. Mandated competitiveprocurement was the dominant regulatoryapproach used during the 1980s throughoutthe United States. More than 100 competitiveprocurements of new power supplies took placein the United States between 1984 and 1993.

An ex ante review has the advantage ofhelping to minimize the level of regulatoryintervention in market-based transactions, sincea good review can reduce the need for regulatoryintervention during the term of the PPA. It doesnot, however, remove the need for the regulator

to retain some form of intervention during thelife of the PPA. And both an ex ante review andan ex post review expose the regulator to therisk of being held responsible by the partiesto the PPA for the performance of the PPA, onthe grounds that the regulator became more of

5 See Arizu, Maurer and Tenenbaum. Pass Through of Power Purchase Costs: Regulatory Challenges and International Practices, WorldBank, Energy and Mining Sector Board Discussion Paper No. 10, February 2004, www.worldbank.org/energy.

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

18/96

REGULATORY REVIEW OF POWER PURCHASE AGREEMENTS: A PROPOSED BENCHMARKING METHODOLOGY

8

a manager than a regulator when it assumedthe role of reviewing contracts and requiringchanges in one or more contract provisions. Theregulator should avoid this risk by followingclear guidelines for its reviews of PPAs.6 As

a general rule, it is preferable for a regulatorto review a PPA before it is signed. Reviewsthat take place after a PPA is signed can causemajor delays that are politically dangerous incountries like Nigeria that are facing majorpower shortages.

Importance of RegulatoryReview of PPAs

A regulator must be concerned about powerpurchase costs under PPAs whenever the powerpurchaser sells power directly or indirectly tocaptive customers (i.e., customers who do nothave the legal right to purchase from alternativesuppliers or choose not to exercise this right).The challenge is to create regulatory mechanismsto provide purchasers with incentives forgood procurement of bulk power, while alsoproviding IPPs with financial incentives tobuild and operate the plant efficiently. Hence,the regulator has to consider the needs of both

purchasers and sellers when reviewing PPAs.When the purchaser is a distributor that

supplies captive customers by means of amonopoly franchise, the regulator should beconcerned that the distributor may not be buyingor building efficiently and thereby is hurting itscaptive customers. This is important because thecost of bulk power supply, irrespective of thestructure of the power supply industry, typicallyrepresents between 50 percent and 70 percentof the distributors total costs of supplying

power to consumers. Distributors argue thatthese costs should be fully passed through inthe tariff-setting process through automaticpassthrough mechanisms because the costsare largely beyond their control. In contrast,regulators are generally wary of automaticpassthrough mechanisms, since they blunt the

incentives to procure efficiently and carefully.There is evidence that automatic passthroughmechanisms can lead to generally inefficient andsloppy procurement practices; sweetheart dealswith affiliated generators; or even corruption.

The regulator should presume, therefore, that,the distributor has some influence over the pricethat it pays for purchased power.

When the seller is an IPP that must invest innew generation capacity to meet its obligationsunder a PPA, the regulator must recognizethat the IPP and its financiers will evaluatethe possibility that the purchasers will misspayments or make late payments under thePPA. If there is a high risk that buyer will missor delay payments, the IPP will inevitably face a

higher cost of capital. This will lead to a higherprice for the power supplied by the IPP and,in turn, a higher retail price of power. Evenif there is a backup payment guarantee fromthe government, an IPP may be concernedthat the government will not actually step inand make payments without involving the IPPin considerable litigation. At the time of thiswriting, the Federal Government of Nigeria andthe World Bank are exploring the possibility ofan alternative payment guarantee mechanism

that is known as a partial risk guarantee(PRG). Under a PRG, the World Bank willguarantee some amount of payments to the IPPif the government is willing to issue a counterguarantee to the World Bank.

The regulator should be concerned, therefore,that the purchaser can afford to meet its paymentobligations under the PPA in the context ofthe policies laid down by government andthe regulator for retail power tariffs and passthrough of bulk supply costs to retail powertariffs. Distributors will not find willing suppliersif the regulator sets an artificially low cap onpassthrough of power purchase costs, whichwould jeopardize the long-term expansion ofpower supply. This is particularly the case incountries in which bulk power markets are inthe early stages of development.

6 One obvious exception to this rule is when a review is necessitated after a PPA is signed because evidence emerges of corruption connectedwith the PPA.

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

19/96

Legal Authority

NERC is required to perform regulatory reviewsof PPAs under the Electricity Power SectorReform Act of 2005 (EPSR Act). Under thisAct, NERC is obliged to ensure that the pricescharged by licensees are fair to consumers andare sufficient to allow the licensees to financeand to allow for reasonable earnings for efficientoperation. In addition, NERC has authorityunder the EPSR Act to specify terms andconditions in a license to ensure that a licenseewill purchase power and other resourcesin an economical and transparent manner.NERC also has authority under the EPSR Act(Section 71) to vary its regulatory requirementsby imposing appropriate terms and conditions

depending on the type of entity that is beingregulated.

These provisions form the legal basis forthe proposals contained in NERCs Notice ofProposed Rulemaking (NOPR) that it publishedfor public consultation in December 2006.7 TheNOPR proposes that a regulatory review will berequired only for PPAs for which the purchaserwill be purchasing power that will resoldeither directly (e.g., a distribution company)or indirectly (e.g., a bulk reseller) to captive

customers. This requirement applies whetherthe PPAs for the sale of such power are contractsbetween affiliated or unaffiliated parties.

NERC interprets its legal obligation to ensurethat a purchase is economical in three ways:

i. The right plant in the right place. The generalcharacteristics of the proposed generation

9

The Proposed Process forReview of PPAs in Nigeria3

facility must be reasonable. Specifically,NERC must see evidence at a general levelthat the entity seeking the license is proposingan appropriate technology, an appropriatefuel and will locate the plant at a reasonable

location. In addition, the application for alicense must be consistent with any formallyenunciated energy policies of the federalgovernment of Nigeria.

ii. A reasonable combination of price and risk.NERC must see evidence that the proposedcombination of price and risk allocation inthe PPA is both fair and efficient.

iii. Affordable to the buyer. NERC must seeevidence that the purchaser will be able toafford to purchase the electricity with therevenues that it is likely to receive from itscustomers and, if available, government-provided subsidies or guarantees. Inparticular, NERC will require an assurancefrom the purchaser that it will be able toafford its payment obligations under the PPAunder existing or expected retail tariffs withthe support of subsidies or guarantees.

Overall, NERC considers that the regulatoryprocess proposed in the NOPR will produce fourmajor benefits.

i. It will allow NERC to fulfill its legalobligation to ensure that its regulatoryactions are fair and balanced and thatlong-term power purchases made on behalfof captive customers are economical.

ii. It will provide a checklist of terms andprovisions and risks that must be considered

7 This NOPR be downloaded from www.nercng.org.

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

20/96

REGULATORY REVIEW OF POWER PURCHASE AGREEMENTS: A PROPOSED BENCHMARKING METHODOLOGY

10

in developing PPAs. This should ensurebetter-quality PPAs in the future and avoidunnecessary and costly disputes.

iii. It will provide NERC with better informationthat can be used to develop projections of

the generation costs that constitute a majorcomponent of future end-use tariffs.

iv. It will ensure that the general public will havebetter knowledge of the basis for NERCsdecisions and will have the opportunity toprovide NERC with informed commentsbased on facts rather than hearsay.

As a general rule, NERC considers that thetwo parties to a contract should have substantialdiscretion in writing the terms and conditions

of the contract, subject to any general guidancethat NERC decides to give in the future andany overall caps on retail tariffs that may beestablished as part of a future multiyear tariffsetting system. However, NERCs fundamentalregulatory concern is that such contracts canalso have a major impact on the prices paid byconsumers of electricity who are not direct partiesto the contract. Therefore, NERC considers thatit has a clear regulatory responsibility to ensurethat the terms and conditions of such contractsare fair and efficient in order to protect thoseNigerian consumers who will ultimately payfor the electricity but who are not signatoriesto the PPA.

The Proposed RegulatoryReview Process

NERC Will Review a PPA, Ratherthan Approve It

NERC will not approve or disapprove of a

PPA. Instead, NERCs review will be limitedto providing comments and observations onthe submitted PPA. The ultimate and bindingcontrol on the prices to consumers of electricitythat result from a PPA will be exercised throughNERCs system of setting retail tariffs for end

users. NERC intends to establish end-user tariffsthrough a multiyear tariff setting system that isthe subject of a separate NOPR.

The seller and purchaser will have theflexibility to decide how they incorporate NERCs

comments into their PPA when they negotiate afinal signed version of the PPA.8 However, theydo so at their own risk. If the parties choose toignore NERCs comments and observations,they are more likely to run the risk of failing tosatisfy the implicit annually adjusted cap on thepower purchase costs that distribution entitieswill be allowed to pass through to their captivecustomers under NERCs planned multiyeartariff setting system.

NERC Is Proposing a Two-stageRegulatory Process for theReview of Generation Licensesand Associated PPAs

In the first stage, the application for a generationlicense will be reviewed according to NERCsstandard review of such applications and thelicense issued if the application meets all ofthe requirements of its licensing regulations.This involves a review of the legal, technical,

and financial elements of the applicant andits proposed generation facility. NERC issuesa generation license to an applicant that hasshown the legal, financial, and technicalcapacity to build and operate the proposedgeneration facility. However, the granting ofa license does not imply that NERC has givenapproval to the terms of any PPA that will beused to sell the power produced from thisgeneration facility.

In the second stage, NERC will review thesubmitted documents to facilitate compliancewith its legal obligation to ensure that thepower is purchased economically and with areasonable allocation of risk. It will providewritten comments to the purchaser and seller.The process for this stage is described in thischapter.

8 The seller will also be required to file the final executed version of the PPA with NERC. This final executed version will be a publiclyavailable document.

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

21/96 11

The Proposed Process for Review of PPAs in Nigeria

NERC considers that this two-stage processhas several advantages. First, it avoids the risk ofdelay to the process of reviewing an applicationfor a generation license. Such delays are likelyto occur if NERC required explicit review of

a PPA as a prerequisite for the issuance of ageneration license. Second, a PPA is likely tobe more accurate and complete if it is reviewedsome time after a license is issued. Third, byconducting the review before a PPA is signed,NERC will be able to give timely feedback to thepurchaser and seller of power about price andnonprice provisions in the PPA that could lead tooutcomes that are too costly, too risky, or both.

To ensure compliance with this two-stageprocess, NERC will attach conditions to the

licenses of entities that will be buying orselling power on behalf of captive customers(e.g., a bulk supplier, generator, or distributor)requiring that these entities provide NERC withthe information needed to conduct its review ofthe PPA as presented in the questionnaires andtables in the annexes attached to its NOPR (anddescribed later in this paper).

The Seller Files the Applicationfor a PPA Review, Accompanied

by a Declaration by the PurchaserIn the second stage, once the PPA has beenfully negotiated (though not executed) betweenthe purchaser and the seller, the seller will berequired to submit the proposed PPA to NERCand also complete the questionnaires and tablesabout prices and risk allocation under the PPA.The seller will be required to vouch by means ofa declaration for the accuracy of the informationthat it submits in the questionnaires and tables.Separately, the purchaser will be formally

required to vouch by means of a declaration that

it can afford its purchase obligations under thePPA.9 In addition, the purchaser will be requiredto state whether it agrees or disagrees with theanswers provided by the seller.

NERC will encourage early submission of

completed questionnaires and tables with theaccompanying PPA so that its review can begiven in a timely manner. In all instances, NERCsreview will be contingent (i.e., conditional) onthe filing of a final and legally binding versionof the PPA with NERC.

The Seller and Purchaser Must UsePlain English for Their Answers

The answers about prices and risk allocation

must be complete, concise, and written inplain English. If the answers do not meet thisstandard, NERC will view the application asbeing not compliant with these requirementsand will not consider the application further. Allother things being equal, applicants are morelikely to get a faster and positive evaluationfrom NERC if they provide accurate, clear, andcomplete answers.

Completion of the questionnaires and tablesabout prices and risk allocation will not imposean undue burden on sellers because sellershave to provide much of the same informationto equity and debt investors in order for theseinvestors to conduct a due diligence review priorto making their investment decisions.

NERC will combine the appraisal ofboth factual information (e.g., charges, plantspecification) and subjective evaluations(e.g., assessments of how risks are allocatedbetween the purchaser and seller) providedabout a PPA by the seller according to theproposed methodology set out in the NOPR

(and described later in this paper). It reserves

9 One reviewer of this report argued that the affordability of the PPA is critical and that NERCs current proposal is inadequate becauseit relies on some subjective questions that are posed to the purchaser by way of self-assessment and it is hard to see why he would haveincentives to answer these questions truthfully. She recommended that the questionnaire be supplemented with some basic numbers[that] could be collected that would allow a simple test of affordability that is grounded in objective financial data. The reviewer suggestedseveral possible statistics: (i) the average price of power provided under the PPA compared to the distributors current average cost ofpower; and (ii) the average price of power provided by the PPA as a percentage of the current end-user tariff; and (iii) the cost of the PPA as apercentage of the utilitys total costs; and (iv) the percentage of the utilitys total power distributed that would come from the new PPA.

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

22/96

REGULATORY REVIEW OF POWER PURCHASE AGREEMENTS: A PROPOSED BENCHMARKING METHODOLOGY

12

the right to seek clarifications from an applicantwhere it finds evidence of inaccuracies andmisrepresentations. It also reserves the rightto use its own assessment of a particularprovision where it considers that the applicants

assessment is not accurate.The accuracy and completeness of

information supplied about prices and riskallocation must be vouched for by a designatedofficer of the companies that are filing theapplication for review.

NERC Will Select an IndependentParty to Analyze the SellersAnswers, and the Seller and

Purchaser Will Pay for This ServiceTo ensure that the review is both objective andinformed, NERC will hire one or more expertsto conduct a written evaluation of the answersgiven by the purchaser and seller. NERC needsthis help to review a PPA comprehensivelybecause a PPA is usually a lengthy documentwith complicated and subtle relationshipsamong its many parts.

The cost of this evaluation will be borne by theseller, or by the purchaser, or shared by the two

parties in whatever way they deem appropriate,and NERC will require the application to specifythe payment arrangements. The written expertevaluation will be made public. NERC willestablish a roster of experts and will determinewhich expert will be used to evaluate theanswers provided in an application. NERCwill also specify the terms of reference for theexperts evaluations. NERC anticipates that theevaluation will take between 10 to 20 person-days, depending on the complexity of the PPA.In selecting the roster of experts, NERC will givepreference to individuals or firms who committo training Nigerian citizens in the relevantevaluation techniques.

NERC Proposes to Make Publicthe PPA, the Sellers Answers tothe Questionnaires and Tables, andNERCs Comments on the PPA

NERC proposes that the answers to thesequestionnaires and the PPAs on which theseanswers are based will be public documents,since it places considerable emphasis on thetransparency of its regulatory processes. Suchtransparency is important, given the largequantities of money involved in transactionsunder PPAs.10 Such participation will be effective(because it will be informed) when the generalpublic has access to the key documents thataffect the prices that they will have to pay over

the life of the PPA. In addition, the fundamentallegitimacy of NERCs new regulatory systemrequires that the general public must haveconfidence in the fairness and impartiality ofboth the process that NERC employs and thedecisions that it renders. This confidence can bedeveloped when the general public understandsthe logic of NERCs decisions and providesinformed inputs to its decisions by havingaccess to the necessary information. Purchasersand sellers will also benefit from the greater

sustainability of their transactions over the longrun when NERC adopts open and transparentprocesses.

NERC Does Not Intend to ReviewAll PPAs

NERC will exempt two types of transactionsinvolving PPAs from its proposed requirementsfor regulatory review. First, NERC will notreview PPAs where the purchasers customerswill have alternative sources of supply and

are therefore less vulnerable to the exercise ofmarket power by a seller such as the purchaserunder the PPA.11 This might occur, for example,

10 NERCs previously issued regulations for the review of license applications require that the general public must be able to participatein such regulatory processes.

11 These customers are defined as eligible customers under Section 27 of the EPSR Act.

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

23/96 13

The Proposed Process for Review of PPAs in Nigeria

if a generator proposes to sell to an industrialcustomer or a group of commercial customersthat have alternative sources of supply.

NERC will also not require generators witha rated capacity of 100 MW or less to fill out

the questionnaire and matrix related to riskallocation, so as to lighten the regulatory burdenon smaller generators. However, NERC willrequire that these smaller generators completethe questionnaire and table about the averagepurchase price, because it will still need toknow the prices at which these generatorswill sell power to entities that supply captivecustomers. The purchasers in these transactionswill still have to complete the declaration ofaffordability.

Possible FurtherDevelopment of theRegulatory Process

NERC Will Examine the Scope fora More Limited Regulatory Review

NERC intends to match its regulatory methodsand standards of review with the processby which the power supply is acquired.12

In the future, if NERC is satisfied that thePPA accompanying the generation licenseapplication is the outcome of a competitiveprocess such as has been employed successfullyin other countries, NERC will employ a fasttrack and more limited form of regulatory

review. This is based on the presumption thatconsumer interests can be best protected byeffective competition and, where competitionexists, regulation can and should be more light-handed. Therefore, NERC intends to initiate a

consultation that will focus on the necessaryelements of open and competitive procurementsfor new generation capacity, as well as possibleelements of one or more model PPA that willbe fair and efficient for sellers, purchasers andretail customers. Standardized PPAs may beespecially beneficial for smaller IPPs.13

NERC Will Develop a Databaseof PPA Terms and Conditions for

Benchmarking Future PPAsConsistent with its emphasis on the importanceof transparency, NERC intends to use theinformation provided in the questionnairesand tables to create a reference database of PPAterms and conditions. It will use this database toderive benchmarks for reviewing the terms andconditions in PPAs submitted in association withapplications for generation licenses. NERC willperiodically update this database and make itpublicly available. Since many energy regulatory

agencies in Africa and elsewhere appear to havesimilar legal obligations to review PPAs, NERCalso intends to explore how this information canbe shared with these agencies to develop betterinformation than would be obtainable on a singlecountry basis.14

12 As noted earlier, Section 71 of the ESPR Act clearly gives NERC the authority to vary its regulatory methods.

13 This does not imply that an IPP would have to adopt the standard PPA exactly as given. Instead, it would be a starting point andmodifications would be allowed if they are highlighted and explained. For example, binding and nonbinding model PPAs have beendeveloped by government authorities in Pakistan and India.

14 In any decision to issue a license, the Ugandan electricity regulator must review the costs of the project (Section 38.1.e) and the price ortariff offered (Section 38.1.k) (The Electricity Act, 1999). In setting tariffs, the Public Utilities Regulatory Commission of Ghana is requiredto take account of the the cost of production of the service (Section 16) and whether the cost of production is justified and reasonable.(PURC Act, 1997). In South Africa, the National Energy Regulator may facilitate the conclusion of an agreement to buy and sell power

between a generator and a purchaser of electricity. (Electricity Regulation Act, 2006, Section 46 (3) (b)). In Tanzania, the new electricitylaw states that a distribution licensees obligations pursuant to a power purchase agreement may only influence a licensees regulatedtariffs if the Authority deems that the costs were prudently incurred. (Electricity Act, 2008, Paragraph 25).

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

24/96

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

25/96

Methodological Issues

The main informational issues for NERCsproposed methodology are: (i) what types ofcost are reviewed; (ii) what types of risks areassessed; and (iii) how these two categories ofinformation will be assessed jointly. This chapteroutlines NERCs proposed methodology fordealing with these issues, and the chapters thatfollow this one provide a detailed descriptionof the methodology.

NERCs proposed methodology requiresthat the applicants provide information on bothprice and risk allocation between the seller andthe purchaser because both factors influence theactual payments made by the purchaser undera PPA. For example, a PPA may propose low

initial prices for capacity and energy but transfermost performance risks (e.g., target availability)to the purchaser, so that the purchaser mayactually pay a lot more for power procuredunder the PPA than under another PPA withhigher initial prices but with more risk borne bythe seller. If a licensee proposes to bear more riskthan usual, it will generally incur an additionalcost for bearing this risk and it will expect tobe compensated for this cost. The proposedmethodology tries to capture this trade-off

between risk and price under a PPA.The pattern of risk allocations that is feasible

in Nigeria at this time may be quite differentfrom patterns of risk allocation that are feasibleand observed in more developed power sectors(e.g., power sectors where there is betterquality of service, lower levels of technical andcommercial losses, an average tariff that recoverscosts, more extensive metering and sufficient

15

The Proposed Methodologyfor the Review of PPAs

in Nigeria

4

generation capacity). Therefore, the prices andrisk allocations observed in other countries withhealthier power sectors may not be appropriate toNigeria. In addition, one particular combinationof price and risk may not be appropriate at all

times and all circumstances (e.g., different fuelsand technologies) in Nigeria.

Approach toAssessment of PPAs

As noted earlier, NERCs assessment will belimited to PPAs where the purchaser will beselling directly (through distribution companies)or indirectly (e.g., as a bulk reseller) resellingthis power to captive customers, and the seller

is selling the electricity from a plant with a ratedcapacity of 100 MW or greater.

NERC proposes to adopt the following three-step approach for assessing the reasonablenessof PPAs under the second stage of its reviewprocess:

i. Assessment of a PPAs completenessii. Performance of the average purchase price

analysis, affordability analysis, and riskassessment of the PPA

iii. Application of the price-risk trade-off

approach to assessing PPAs

This approach is depicted in Figure 4.1.The first step in NERCs review of PPAs is

designed to separate PPAs that are completefrom those that are not. In this step, NERC willdetermine whether the PPA satisfies certainminimum, or threshold, conditions that justifyfurther regulatory review. If the PPA does not

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

26/96

REGULATORY REVIEW OF POWER PURCHASE AGREEMENTS: A PROPOSED BENCHMARKING METHODOLOGY

16

satisfy the minimum, or threshold, conditions, thenNERC cannot justify using its limited regulatoryresources on further review of the PPA.

Under the second step in NERCs review,the seller must provide NERC with a completed

copy of the questionnaires and tables shown inthe NOPR and reproduced herein in Annexes1, 2, 4, and 5. The seller must vouch forits responses to these questionnaires andtables by attaching a declaration to them. Thefocus of these questionnaires and tables is toabstract basic information from the lengthyand complex documents that are typical ofPPAs. That information will be used to evaluatesystematically the reasonableness of the priceand nonprice terms of PPAs. Specifically, the

sellers analysis of the average purchase priceand risk allocation for its PPA provides a set ofvalues for these key variables that is used in thethird step: the review of the price-risk trade-off.These questionnaires and tables also incorporatea considerable amount of standardization to helpNERC to benchmark PPAs.

Annex 6 is a sample of a completed versionof the risk assessment (Annex 5). This versionis entirely illustrative.

The purchaser carries out the affordabilityanalysis under this stage, for which it providesa declaration to NERC. The purchaser mustcomplete and vouch for its responses to Annex 3by attaching a declaration to it. The purchaser

must also complete Annex 7 about the extentto which it agrees or disagrees with the sellersresponses to the questionnaires and tables.The purchaser should be able to provide thisinformation from its due diligence on the PPAand related documentation.

In summary, NERCs review of a PPA will becarried out by means of the following annexes:

Annex 1: Questionnaire for Computing theAverage Purchase Price of Power under a

Power Purchase Agreement Annex 2: Summary of Key Factors Affectinga Power Purchase Agreement

Annex 3: Purchasers Declaration aboutAffordability of Its Payment Obligationsunder a Power Purchase Agreement

Annex 4: Questionnaire on Risk Allocationunder a Power Purchase Agreement

Annex 5: Table for Risk Assessment of aPower Purchase Agreement

Figure 4.1 Overview of NERCs Proposed Approach for Reviewing PPAs

Source: Besant-Jones, Tenenbaum and Tallapragada.

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

27/96 17

The Proposed Methodology for Review of PPAs in Nigeria

Annex 6: Illustrative Risk Assessment of aPower Purchase Agreement

Annex 7: Purchasers Declaration aboutSellers Responses to Questionnaires andTables under a Power Purchase Agreement

These annexes apply to the case of a newfossil-fueled generation plant. The links betweenthese annexes and the three-stage review processare depicted in Figure 4.2.

Assessment of theCompleteness of anApplicants PPA

Assessment of the completeness of an applicants

PPA is the first step of NERCs approach toreviewing a PPA. Once NERC deems the PPA

to have satisfied this minimum standard, it willevaluate the PPA for price and the risk exposureto the purchaser under the PPA.

A PPA should cover all critical subjectsand not have omissions that might disrupt the

operation of the PPA or cause avoidable costsfor the seller or purchaser during the life ofthe agreement. NERC may decide to suspendfurther analysis of a PPA that is not complete inthis respect.

NERC will create checklists for PPAs for fossil-fueled and other power generation technologies.An illustrative checklistexcluding standardlegal provisionsfor a typical PPA for a newfossil-fueled power project is shown in Tables 4.1aand 4.1b.15

Figure 4.2 Links between the Review Approach and the Questionnaires and Tables

15 The terminology used in Tables 4.1a and 4.1b to describe these clauses, articles and schedules is not prescriptive since it varies amongPPAs. The importance of these terms lies in the substantive content that they cover.

Source: Besant-Jones, Tenenbaum and Tallapragada.

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

28/96

REGULATORY REVIEW OF POWER PURCHASE AGREEMENTS: A PROPOSED BENCHMARKING METHODOLOGY

18

Definition of ContractTerms

Sellers Responsibilities PurchasersResponsibilities

Construction of the power

plant

Compliance with

technical, operational andenvironmental standardsand regulations

Compliance with the grid

code

Compliance with meteringand telecommunicationspecifications

Control, operation, anddispatch of the powerplant and maintenancecoordination

Interconnection withtransmission system

Supply of fuel Availability commitmentsand capacity testingprocedure

Supply of and payment forelectricity

Fees, pricing and billing Time and place of payment Compliance with laws

Liability andindemnification

Payment guarantee (if any) Contract term

Insurance Force majeure Taxes

Liquidated damages Suspension, events ofdefault and termination,and buy-out

Assignment of rights,benefits and obligations

Dispute resolution Law, jurisdiction; agents forservice

Representations andwarranties

Table 4.1a Typical Main Clauses/Articles in a PPA for a New Fossil-Fueled Power Plant

Specifications forElectricity

Plant OperatingParameters

Milestone Schedule

Guaranteed completiondate

Compliance with grid code,transmission connection,dispatch, coordination andscheduling, and emergencyprocedures

Description of site

Delivery point Transmission LineSpecifications

Electricity deliveryprocedures

Metering and recording ofelectricity, collection and

validation procedures

Calculation of Payment Capacity and performancetesting procedures

Guarantor supportprovisions

Seller and purchaserinsurance requirements

Governmental approvals

Table 4.1b Typical Main Schedules Annexed to a PPA for a New Fossil-Fueled Power Plant

Source: Besant-Jones, Tenenbaum and Tallapragada.

Source: Besant-Jones, Tenenbaum and Tallapragada.

Note: Clauses/articles form the main part of the PPA. Schedules are attached to the PPA and contain detailed provisions relating to clauses/articles. Both

clauses/articles and schedules are integral parts of the PPA, and the PPA is not complete without all of them.

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

29/96

Analysis of the average price of purchasedpower under a PPA forms the first componentof the second step of NERCs assessment of thereasonableness of a long-term PPA.

Structure of PowerPurchase Price

The average price of power purchased undera PPA is estimated from the rates payable fora specified level of power purchased over thelife of the PPA. These rates typically includethe following components under a PPA for afossil-fueled generation plant that is financed,constructed and operated by an independentpower developer (IPP): 16

Capacity purchase charge Energy purchase charge Supplemental charges

The capacity purchase charge consists of aperiodicusually monthlypayment that istypically tied to a declaration by the seller thatthe plant has available production capacity at alevel that is periodically verified according toa procedure specified in the PPA. This chargeis usually defined to cover the sellers cost for

investment in developing and constructingthe power plant, as well as the fixed operatingcosts such as insurance and fixed operating andmaintenance costs for the plant.

19

Average Purchase PriceAnalysis5

The energy purchase charge consists of aperiodic payment for the amount of energyproduced and purchased under the PPAduring a specified period. It is usually definedto cover fuel costs and variable operation and

maintenance costs.The supplemental charge may cover plantstart-up and ramp-up costs, the costs of providingancillary services to the system operator such asreactive power, frequency response, black startand fast start, and miscellaneous costs.17

The schedule for the calculation of paymentsdue under the PPA will typically give a base setof rates for capacity purchase charge, energypurchase charge and supplemental chargesand various specified adjustment mechanisms.The rates charged will be heavily affected bythe investment cost for the plant, the foreignexchange rate, the foreign inflation rate, thedomestic inflation rate, and the price of fuelconsumed by the plant.

The average purchase price of power purchasedunder the PPA is computed from these chargesaccording to a basic general formula given inBox 5.1.

There are various formulations that can beused to compute the values of the charges thatmake up this expression for the average purchase

price of power. NERC has selected simpleformulations to facilitate its review process,even though these formulations may not capturesecondary factors that could influence the

16 NERC does not favor a price structure that is based on a single charge for all costs based on the amount of energy sold under thePPA, because payments under this structure do not reflect the actual costs involved in supplying power. Instead, it prefers separationof charges into components that reflect the actual costs, such as the three shown here (capacity charge, energy charge, and supplementalcharges).

17 NERC encourages sellers to accept obligations to provide ancillary services, so as to improve the overall reliability of supply in theNigerian power system.

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

30/96

REGULATORY REVIEW OF POWER PURCHASE AGREEMENTS: A PROPOSED BENCHMARKING METHODOLOGY

20

level of charges under the PPA. NERC expects,however, the seller and purchaser to consider allthe relevant factors in their analysis.

Sellers will be required to provide theinformation needed to compute the averagepurchase price of power under the PPA bycompleting the questionnaire reproduced inAnnex 1. They will also be required to completea summary table shown Annex 2, based on theirresponses to the questionnaire in Annex 1. Thepurpose of Annex 2 is to provide a convenientsummary of the key components of overall averagepurchase price of power and the factors that affectthis average price. In the event that informationgiven in Annex 2 is not consistent with information

given in Annex 1, NERC will use the informationgiven in Annex 1 for its assessment.

Purchasers Priceversus Sellers Cost

The averagepurchaseprice is calculated from thepurchasers perspective under the PPA. It dependson the actual costs incurred by the seller indeveloping, constructing, operating, andfinancing the plant over the life of the plant(life-cycle cost).

The capacity purchase charge spreads(levelizes) over a period of years specified inthe PPA the construction and other initial costs

Box 5.1 General Formula for Calculating the Average Purchase Price Under a PPA

The main components of the average purchaseprice (P

AVexpressed in US$/kWh) are:

Capacity purchase charge (CP) Energy purchase charge (E)

Supplemental charges (S)

These components are expressed in US$/month

(since a month is the usual billing period): 1

PAV

= (CP + E + S) /EENERGY

where EENERGY

is the amount of net electricalenergy supplied during the month that is metered

at a delivery point specified in the PPA (expressedin kWh/month).

The capacity purchase charge (CP) covers thecosts of the following components:

Investment for power plant and equipment,dedicated fuel supply link, and dedicatedtransmission link (CP

INV)

Operation & maintenance Fixed portion

(CPOF

) Insurance (CP

INSUR)

General and administration (CPGEN

)

These unit costs are usually expressed in terms ofUS$/kW/month. This charge is payable independently

of the amount of energy supplied under the PPA:CP = (CP

INV+ CP

OF+ CP

INSUR+ CP

GEN) xC

CAPACITY

where CCAPACITY

is the average available capacityprovided during the month (expressed in kW).

The energy purchase charge (E) covers thecosts of the following components:

Fuel (EF) Operation and MaintenanceVariable portion

(EOV

)

These unit costs are usually expressed in terms

of US$/kWh.

E = (EF

+ EOV

) x EENERGY

Unless the fuel market that supplies the powerplant is fully liberalized, the cost of fuel is usually

indexed to the prevailing market price of this fuelor a benchmark fuel price, which passes throughthe fuel price risk to the purchaser.

Supplemental charges (S, usually expressed

in US$/month) cover charges such as plantstart-up and ramp-up costs above a maximumnumber of such events per period specified inthe PPA (in which case, the monthly charge is the

charge per event times the chargeable numberof these events), as well as the costs of providingancillary services and miscellaneous costs specifiedin the PPA.

Note 1: The selection of U.S. dollars in this

illustration as the currency for expressing costsdoes not preclude the adoption of the naira in

practice, where appropriate. An advantage ofexpressing the values in U.S. dollars is that it

will facilitate comparisons with PPAs in othercountries.

Source: Besant-Jones, Tenenbaum and Tallapragada.

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

31/96 21

Average Purchase Price Analysis

incurred by the seller in developing the powerfacility. Usually for new generation facilities, thisperiod is at least as long as the repayment periodfor the sellers long-term debt used to financethese costs. Hence, the formula for the average

purchase price given in the box represents alevelized cost for power under the PPA for thepurchaser. In a PPA where the capacity purchasecharge is reduced after a period of years specifiedin the PPA, the average purchase price of powerover the term of the PPA is a function of bothlevels of capacity purchase charge.

Both the seller and the purchaser enter intolong-term financial obligations under the PPAthat expose them to financial risks.18 Whereasthe cost of the sellers risk exposure is normally

reflected in the sellers cost of capital that isrecovered in the capacity purchase charge,19 thecost of the purchasers risk exposure (e.g., theunwillingness or inability of the purchaserscustomers to pay the purchaser in full orpromptly for power sold by the purchaser tothem) is not reflected in the rates for powersupplied under PPA.

The purchasers risk exposure is thereforeassessed separately in the affordability analysisand the risk assessment. These two key

dimensions of any PPAaverage price andrisk exposureare then combined in a way thattrades off low price with high riskand viceversa as a basis for comparing a number ofPPAs that have various combinations of thesevariables. The underlying assumption is that afull and objective regulatory review requires anexamination of both dimensions of the PPA andthe trade-offs between them.

Benchmarking the Average

Purchase Price of PowerNERC will compare the average purchase priceof power computed from rates given in a PPAwith a benchmark of prices for other PPAs.

This comparison will complement the riskassessment by indicating any unusual featuresof the payments to be made under the PPA. Itwill draw on NERCs reference database of PPAsas well as other data sources.

Differences in subsidies received and taxespaidin both their direct and indirect formsfor power projects can strongly influence theprice of purchased power under a PPA. Animportant example in the case of a fossil-fueledpower plant is any subsidies and taxes on fuelsused for generating power from the plant.The questionnaire on average purchase price(Annex 1) therefore asks for information aboutany subsidies received and taxes payable by theproject company for the generating plant and

that will be incorporated into the costs specifiedin the PPA. NERC will adjust the costs for themain components of the average purchase priceof power to take account of these subsidies andtaxes, and compute an adjusted average purchase

price of power from these adjusted rates. NERCwill use this cost when comparing averagepurchase prices of power under PPAs.

Affordability of the PPA

for the PurchaserAffordability analysis forms the second componentin the second step of NERCs assessment of thereasonableness of a long-term PPA.

NERC recognizes that even if a PPA is fairand efficient for the parties to the agreement, thePPAmay still not be affordable for the purchaser (orto distributors or final consumers of electricitythat bear the costs passed through by thepurchaser under the terms of the PPA). In otherwords, the PPA may create payment obligations

that are simply not affordable for the purchaserbecause the payments cannot be covered withrevenues that the purchaser will receive from itsretail customers for power procured under thePPA. For NERC to make a determination that a

18 In the case of a new 500MW plant with combined-cycle gas turbines that burn natural gas, for example, the seller can invest aroundUS$400 million in the plant, and the purchaser may enter into payment obligations of around US$130 million per year for capacity, energyand supplementary charges under the PPA when the plant is operated near to its capacity.

19 A basic justification for the long-terms of PPAs is to reduce the sellers cost of capital.

-

8/2/2019 ESMAP 337-08 Regulatory

32/96

REGULATORY REVIEW OF POWER PURCHASE AGREEMENTS: A PROPOSED BENCHMARKING METHODOLOGY

22

purchase is economical, therefore, it must beable to examine the revenues that will be earnedby the purchaser and the possible impact of thispurchase on regulated electricity tariffs.20 And ifthe tariff increase is not affordable to Nigerian

consumers, the Nigerian government is likelyto find itself paying for the shortfall underguarantee or securitization agreements. But ineither case, Nigerian citizens will ultimately payfor the shortfall either as electricity consumersor as taxpayers.

This does not imply that NERC will use itsreview of the PPA to conduct a full evaluationof the level and structure of the basis for thepurchasers revenues. This will require a separateregulatory tariff review that NERC intends

to conduct in the context of its proceedingsdealing with the setting of multiyear tariffs fordistribution entities and the establishment ofregulations for the passthrough of changes ingeneration costs to retail tariffs. Nevertheless,NERCs regulatory review of a PPA would havelittle point if it had good reason to considerthat the purchaser cannot afford its paymentobligations under the PPA due to the impact ofthis commitment on regulated tariffs.

NERC recognizes the seller will probablynot have accurate information about theaffordability of the PPA for the purchaser.21Such information is likely to be known onlyby th e purchaser. Th eref ore, NE RC wi ll

require that the purchaser shall complete aseparate questionnaire (Annex 3) that must beaccompanied by a signed statement from anauthorized representative of the purchaser thatprovides answers to the following questions:

i. Can you afford to make this proposedpurchase under your existing tariff(s) to yourown customers?

ii. If the answer is no, what is your currentestimated revenue shortfall without the

addition of this PPA?iii. If nothing else changes, by how much would

your current expected revenue shortfallincrease on a percentage and absolute basisas a result of the expected payments underthe PPA?

iv. Estimate the required percentage increasein your average tariff(s) to eliminate anyadditional shortfall as a result of this PPA.