Escalating American Consumerism 2015 UPDATE

-

Upload

derek-m-lough -

Category

Documents

-

view

164 -

download

0

Transcript of Escalating American Consumerism 2015 UPDATE

Running Head: ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM

Escalating American Consumerism:

Effects on the Family Unit, Healthcare, and Politics

Derek Lough

University of San Francisco

Contact: [email protected]

Updated 4/3/2015

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 2

The effects of a 2008 recession in the United States of America are still prevalent, yet

Americans spent a record amount of money over the 2011 Black Friday Weekend (Dickler,

2011). Most American consumption over the holiday weekend focused on “discretionary

purchases” instead of necessities (Dickler, 2011) despite a social movement focusing on how

greed’s effects on society resulting in hundreds of the most populated cities in the country being

“Occupied”. How has this escalation of American consumerism affected the family unit? Or

healthcare? Or politics? Though only 5 percent of the Occupy Wall Street movement call for

abandoning capitalism (Hayat, 2011), I was still shocked that my fellow Americans would

continue to consume in an escalating fashion especially as the net worth of people under thirty-

five fell by 68 percent between 1984 and 2009 (Cohn, 2011) and 19.8 percent of high school

students in 2010 were living in poverty (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). This review of literature

focused on American consumerism will address its effects on the family unit, healthcare, and

politics.

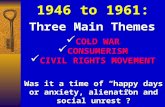

In the first section, the material will focus on the evolution of consumption in America

and the appropriate educational framework from which to analyze it, beginning with a review of

the paradigm shift that occurred between the 1950s family unit and that of today, as well as the

development of its progeny. Then I will look at how this consumption affects Americans’ health

in relations to advertising and consumerist ideals present in the healthcare industry. An

examination of the literature concerning consumerism and three varied political responses will

conclude this review. It is my hope to draw critical awareness to how this intensification of

consumption-culture in the United States affects us as individuals, in our most intimate

relationships, as well as the balance of power in politics.

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 3

Cultural Analysis of American Consumerism

Consumption under a Cultural Framework

Though every person on the planet is affected by consumerism on some level, few

scholars acknowledge the powerful role consumption plays in education. Reframing adult

educators to embrace their role as facilitators of political influence, Sandlin (2005) argues that it

is essential to recognize different models of behavior concerning consumerism and enlighten

students to the different reactions possible under the current economic system. The purpose of

transitioning consumer education from the collection of skills and knowledge - needed to

effectively make decisions, manage resources, and participate as a citizen-consumer - to focusing

on limiting consumption, combating over-capitalism, and “jamming corporate-sponsored

consumer culture (Sandlin, 2005, p. 166) lies in the unseen political nature of educators. As

Sardar and Van Loon (1999) point out, the purpose of cultural studies “is to expose power

relationships and examine how these relationships influence and shape cultural studies” (as cited

in Sandlin, 2005). While the original nature of consumer education is framed within the current

economic system, the Occupy Movement - in addition to the grievances articulated in this review

- expresses the importance of imparting critical thinking to students, giving them the skills to

reassess a system for the future.

Control as a Necessity

In order to understand the culture of consumerism that exists in the United States, it is

essential to understand how much of a necessity the feeling of control is to the lives of

Americans. Gans (1988) narrows the restraints of his analysis to middle America and its

perpetual need for control through individualism. By stating the lack of control concerning the

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 4

systems of economics and politics, personal employment and allocation of national resources,

Gans argues that the highly diverse population is unable to influence the organizational impact of

government (p. xi). This dissatisfaction with political and economic institutions leads the

population to determine their own happiness within the terms of their everyday lives. Gabriel and

Lang (1995) argue this happiness is found in consumption due to the many choices and ability to

acquire possessions which reflects personal freedom (p. 8).

Though symptoms of consumerism can be traced to as early as the mid-nineteenth

century (Stearns, 2006, p.48), it wasn’t until the 1950s in post-WWII America that the escalation

of this culture boomed (p. 77). While the significance of the factors that led to this evolution has

been debated, the results are evident worldwide in nearly every conceivable fashion. The focus

of this literature review remains on the family, healthcare, and politics, yet consumerism

influences psychology, entertainment, athletics, and many other facets of everyday life. One

reason for that comes from the planned launch of this phenomenon as an effort to capitalize on

the high levels of production the United States enjoyed during the Second World War. Victor

Lebow (1955) succinctly laid the foundation for the ideology of American consumerism as a

means for economic prosperity:

“Our enormously productive economy… demands that we make

consumption our way of life, that we convert the buying and use of

goods into rituals, that we seek our spiritual satisfaction, our ego

satisfaction, in consumption… We need things consumed, burned

up, worn out, replaced, and discarded at an ever increasing rate.”

Annie Leonard’s use of this quote in The Story of Stuff (2011) creates a powerful argument for

the purposeful design of an economic system relying on the manipulation of citizens at the cost

of natural resources and human lives (p. 10). Whether the corporations and government actively

pursued this objective or not, the societal values that were important prior to the 1950s no longer

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 5

remained imperative; instead our place in the consumer hierarchy rose to vital concern for the

majority (Hill, 2002, p. 274).

Identity Formation

In this current economic system, rather than preserving the societal identities formed

around community, meritocracy, and service that were deemed precious prior to WWII, Annie

Leonard emphasizes the lack of value members of the human race have when they are not

purchasing or possessing items meant for consumption (Leonard, 2011, p. 4). Hill (2002)

continues on this line of thought when he cites Slater (1997), who argues that the consumption of

goods forms our social identities and positions us to exhibit these identities within society.

Focusing on middle America and the working class, this creation of this role can be traced back

to the transformation of advertising from utility to linking consumer goods with essential human

needs (Hill, p. 274).

Advertising, as Chin argues, derives from the idea that the targets are of middle-class

regarding their goals and resources (as cited in Hill, 2002). Due to the economic prosperity

perceived as nearly holistic in the 1950s, manufacturers and producers used mass psychology to

push a new definition of class on the population (Stearns, 2006) shifting their themes towards

self-improvement and image (p. 137). The middle-class of the United States indulged in many

consumer goods as an expression of desire for a better life. This transformation was made

possible due to the escalating availability of television sets across the nation, as Stearns denotes

that advertising and television were united from conception (p. 140). This eventually evolved to

cross-selling and shared-advertising between television and film entertainment, the music

industry, toy manufacturing, and sustenance using mass-marketing (Stearns, p. 140). Reinforcing

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 6

the concept that material abundance is a means towards happiness, the variety of advertising and

products for consumption provided limitless paths towards personal growth and satisfaction still

prevalent today.

Unfortunately for the working class, systemic poverty does not allow them to participate

in the hierarchy of American consumerism to the same extent that middle-class prosperity

allowed the majority of the country to fuel their desires for most of the past fifty years (Hill,

2002). This does not mean that those living in poverty are not subjected to the same 3000

advertisements that other Americans view each day (Leonard, 2011). Television, radio, and ads

in public spaces all attribute to the collective desire for material possessions. The reaction to this

bombardment has been dually analyzed by various scholars, with some views receiving

particular criticism. Hill (2002) reviews the literature of Oscar Lewis (1959) whose “culture of

poverty” theorizes that those without access to material wealth respond with low-self esteem and

despair (p. 275). Harsh criticism followed Lewis, as Hill points to Leeds (1971), providing the

dissent that the behaviors exhibited in poverty would coincide with those of the wealthy if

monetary restrictions disappeared (p. 276). Eventually the various industries provided choice

enough to bring the poor and disenfranchised into the fold of consumerism, so well in fact that

“by 2001…over half of all Americans had almost no savings and a third lived paycheck to

paycheck, often in considerable consumer debt” (Stearns, p. 142). The process by which these

statistics occurred will be reviewed forthwith, specifically focusing on American consumerism’s

deconstructive effect on the family, healthcare, and politics in the United States.

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 7

Family-Consumerist Dynamics

Deconstructing the Family

The formation and sustainability of the family dynamic in the United States has been

deconstructed and changed through the escalation of American consumerism. Stearns (2006)

offers support for this process by analyzing the creation of the family through the processes of

courtship and dating. The values of the traditional courtship, like many other values, transformed

after 1910 due to consumerism (p. 58). The focal division from conventional to new may be

reflected in the how young couples spend their time and money. As consumption rose, Stearns

postulates that dating served to compare various suitors for their prowess as a consumer;

combining romantics and a costly event provided a baseline for material affection for both men

and women (2006).

Material wealth is the driving force behind many familial decisions about living

arrangements, employment, and even having children. So many factors for both the middle and

working classes are affected by American consumerism that Hill (2002) provides a thematic

interpretation of data concerning various subpopulations of the United States. One of the

descriptions reflects a family forced to move out of their home when a coal mining operation

closes. Due to insufficient employment options for comparable living standards, the husband and

wife move into a trailer, spending the next few years watching their possessions fall to disarray

due to the decline in pay, various negative emotions overwhelm them until prayer is their only

redress. (Hill, p. 280). Furthermore, Hill describes another case of material wealth depletion

where a husband is forced to commute hundreds of miles for an equivalent position, in order to

keep the same standard of living, even if he was forced to be away from his family to achieve it

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 8

(p. 282). The prevalence of material restrictions can have a wide variety of negative effects on

the family.

One such circumstance is the high probability of divorce. Stearns (2006) argues that

consumerism has affected the divorce rates in the United States due to bickering over living

standards. Amato and Keith (1991) agree that divorce has steadily risen since the 1950s, with

over 1 million new children facing the legal dissolution of their family unit every year (p. 26). A

shocking projection by Bumpass (1984) shows that nearly twice as many black children born to

married parents will face divorce as compared to white children (as cited in Amato). As finances

are the 2nd

most cited reason for divorce in the United States this statistic is less surprising when

taking into consideration the fact that white households have a median wealth twenty times that

of African-American households (Kochhar, 2011). There are as many examples of this as there is

children experiencing divorce, but Amato maintains that the child tends to come into conflict

with one parent or both due to decisions by one parent or the other (Amato, 1986, as cited in

1991). One method of parents currying favor with the child is through consumerism.

Raising the Consumer-Child

Childrearing has increasingly shifted from a community venture to an individualized

effort, the socio-psychological effects of which may only be becoming visible now. Stearns

(2006) discusses the entrance of consumerism on the parental behaviors concerning how they

nurture their child, arguing that advice manuals and limited time promote the gifting of consumer

goods to children as an adequate substitution for affection and presence. Worse yet, he

convincingly makes his case that replacing negative emotions with objects of desire has become

a normal parental process—as well as something that is passed on generationally—so much so,

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 9

in fact, that most of the population believes that this is a normal response. Introducing these

consumerist tendencies so early allows a more expansive blossoming of compensation for

unsatisfactory lives later in life (Stearns, 2006, p. 60). This naturalization of consumption from

parent to child is the foundation of escalating American consumerism, perpetuating itself from

generation to generation (Stearns, 2006).

Consuming Religion

Stearns (2006) continues to provide a timeline for escalating American consumption with

his book Consumerism in World History: The Global Transformation of Desire, where he

discusses the earliest religious protests against excess expenditure occurring in the early to mid-

19th

century (p. 68). This didn’t stop American missionaries from exporting their consumerist

ideals “virtually everywhere they went” (p. 64). Furthermore, he discusses Protestant criticisms

by ministers in the United States, addressing the lack of moral fiber exhibited in the “parade of

luxury” when such time could be spent worshiping God (Stearns, p. 57). Using Max Weber’s

model from his paper The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism where he argues than due

to a lack of emphasis on the Catholic “grace,” Protestants believed that if you worked hard and

were a devout Christian, God would reward you with financial prosperity (Weber, 1904),

Cantoni (2010) contends that Protestants and Catholics lacked any significant different in

regional wealth in the long run (p. 34).

As if purchasing the latest styles and products guaranteed favor with the Lord, Americans

took this philosophy to heart when celebrating holidays nationwide. Stearns contends that the

earliest Christmas presents purchased commercially provided happiness for families one-hundred

and eighty years ago (2006, p. 58), yet through escalation it is more likely a child today will feel

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 10

disappointment on Christmas than joy (Hill, 2002). Through the creation of holidays in the

United States, the commercialization of familial sentiments has been completed, and paper cards

for Valentine’s day and the innovation of birthday gifts has exploded into a worldwide

phenomenon since 1855 (Stearns, 2006). The exploitation of the family continued in the 1900s

with the invention of Mother’s Day. What was meant to be a day of reflection, joy, and

togetherness became something more recognizable as consumerism today. Anna Jarvis, an

original advocate for the holiday, changed her tune only nine years after its conception, “This is

not what I intended, I wanted it to be a day of sentiment, not profit” (Stearns, p. 58). One only

needs to walk through a department store any day between Black Friday and Christmas to

understand the transformation religious and familial holidays have incurred in the last century.

Health Consumption and Consumerist Healthcare

Body Image

If the escalation in American consumerism actively deconstructed the 1950s concept of

the family unit, could it have a similar effect on citizens at the personal level? Featherstone

(2010) explores how the body, image and consumption interact in society in relation to the

prevalence of video and photography. He argues that the dominant mode of representation

relating to one’s self-image evolved from the increased use of photography by all areas of public

and society (Featherstone, 2010). During the Second World War, and immediately after, there

was an increased advertisement campaign to push low self-esteem on the population, shrouding

the message of poor body image with moral connotation (Stearns, 2006). In a study analyzing the

effects of television advertising, Lavine (1999) found that women exposed to sexist ads judged

their own bodies as larger than it was in reality and that men judged themselves thinner than their

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 11

ideal body size (as presented in the ads). Considering that over 90 percent of American homes

have a television (Nielson, as cited in Lavine, p. 1049), Featherstone (2010) argues that women

assume that by transforming themselves into the women they perceive as ideal, and desire to

become, they be “better able to move through interpersonal spaces and [be] more able to enjoy

the full range of lifestyle opportunities and pleasures on offer” (p. 196). These transformations

can be achieved using various methods from dieting and exercise, pills, or cosmetic surgery;

however the individual pursues it, personal metamorphosis has become a cultural archetype in

the United States (Featherstone, 2010).

Transformation

Though Featherstone (2010) argues that in order to completely change oneself they must

methodically act and look in such a way that they pretend to be the person they wish to become

(p. 196), Americans use a variety of techniques to fulfill themselves emotionally and physically.

Though the world of fashion mostly lay at the feet of women beginning in the 1950s,various self-

image products began being consumed by men at a rapid and escalating pace in the 1980s and

1990s (Stearns, 2006). Today any walk through a major value store would present dozens (if not

hundreds) of different cosmetic, athletic, and hygienic products targeted specifically at men.

Aside from material items for purchase, Americans employ dieting supplements and elective

surgery to complete their metamorphosis. The increased use of these processes, Featherstone

(2010) argues, is due to the innovation of reality television programming where ordinary women

were able to become younger-looking and aesthetically pleasing on a regular basis. Considering

the Botox industry is now valued at more than a billion dollars a year (Cooke, 2008, as cited in

Featherstone), it seems that both men and women have fewer concerns about the ability to

express certain emotions than they do about the health concerns of a neurotoxin.

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 12

Choice in Healthcare

An aging population should certainly rank healthcare as one of the their primary concerns,

yet the discussion over how American consumerism affects the industry is incomplete. Gilleard

and Higgs (1998) contend that the those with material wealth, but post retirement benefit the

most from the shifting paradigm of a government safety net to the ensuring of customer

satisfaction through a consumerist perspective (p.236). Furthermore, they argue that the elderly

with limited material wealth must rely on the government or are unable to participate in the life-

extending industry, as opposed to those with the material wealth to actually “exercise choice

between competing providers in public health and social care market, those without such power”

(Gilleard, 236). According to the US Census Bureau, as of 2011 a full twenty-percent of fourth-

agers (those aged sixty-five years and older) have less than 400 dollars in assets and must depend

fully on the state for their healthcare (as cited in Vornonitsky, p. 7).

The concept of choice in healthcare extends to the younger generations as well. Scholars

have shown that escalating consumerism in these fields is detrimental to children (Lindley, 2004).

A study of children suffering from functional abdominal pain (FAP) shows that continued

negative results after several referrals over a 12 months period “was associated with

psychological services” for the family and patient, whereas those who maintained a unilateral

doctor-patient relationship, showing trust in the advice of the medical professional has positive

outcomes (Lindley, 2004). Whether distrust of doctors or a consumerist mentality - where the

family continuously sought a more favorable option - this behavior often led to aggression and

manipulative complaints, resulting in continued poor health. Gilleard and Higgs (1998) argue

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 13

that the United States model of personal assistance afforded to independent living and those with

disabilities led to the “consumer-directed” attitude visible in the healthcare industry (p. 244).

Healthcare plays a prominent role in American politics; and as the final section of the review will

show, so too does the escalation of American consumerism.

Politics of Consumption

Good Consumer-Citizens

In the weeks after September 11, 2001 President Bush told the nation to go shopping and

strengthen tourism. Some argue his act of “popular deference” instead of a call for engaged

citizenry was meant to distract from the allegations against Iraq (Bacevich, 2008), and as a

means to fund a two-front war without raising taxes. Americans escalated their consumption per

his request, and as Dickler (2011) points out, even in the time of recession that rampant

consumerism did not stop. Even prior to the terrorist attacks of 9/11, adhering to capitalist ideals

had been praised since the fifties as a way to combat the United States enemies. Demonizing

communism and fascism during WW-II and beyond (Stearns, 2006), the Bush Administration

only reinforced what had become habitual and normal—outspending our financial capacity. Even

traditional consumer education teaches its students that to navigate the complicated free-market

is to gain an advantage over everyday consumers (Sandlin, 2005). Moreover, like President Bush,

this paradigm shifts the critical eye of the consumer onto the producers rather than the system

itself (Sandlin, p.175), focusing in the symptoms rather than the root cause. Soper argues in Re-

thinking the ‘Good Life’ than no citizen would righteously agree that naming their familial

connections and best interests to be subsidiary to those of the state (p. 207) is their duty to their

government, yet Americans escalated their addiction to spending when the states requested it.

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 14

However, as not every citizen participated in this shopping extravaganza, further research should

point towards reasons middle and working class consumers might possess when choosing not to

spend their money.

Individualism: Altruism and Hedonism

Sandlin (2005) argues that consumer education as a political site raises the critical-

thinking skills of students to such a degree that another type of consumer is formed, one

concerned with the effects this consumption culture has on other facets of life (p. 175). Building

on that, maintaining high standards of living is deeply-interconnected to more consideration

being taken with “freedom, environmental preservation, and sustainability” (Soper, 2007, p. 210).

This altruistic consumer would probably have been an individual who once had faced injustice in

terms of consumption decisions leading to a new awareness of wider concerns related to their

personal experience (Soper, 2007).

The consumer can evolve his or her behavior internally to reflect a hope of a wider

alternative behavior eventually being adopted. Various studies support this line of thinking,

postulating key variables of these consumers as young with a high level of discontent, unlikely to

possess much faith in government enacting their personal choice of policy, with a higher

education, an interest in politics, and high level of civic initiative (Newman, p. 9). Another study

contributes to these findings, with results showing that “individuals who express environmental

concerns tend to consume public affairs programming and nature documentaries at higher levels”

(Shah, 2007, p. 221). Furthermore, scholarly work by Soper adds that this framework, while

enlightening some consumers, polarizes the majority, due to the assigning of blame for society’s

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 15

larger issues to the one doing the consumption (p. 208). Not every scholar’s work concludes that

these individual choices are altogether altruistic.

Dubbed “alternative hedonism” by Soper, she contends that some consumers choose a

lifestyle similar to those citizens described above, yet is derived from the selfish behavior

patterns noticeably consistent with the Gans (1988) definition of middle American individualism

where a consumer would change his or her lifestyle and consumption choices due to externalities

personally affecting them, such as forfeiting the use of a car in exchange for utilizing the

diminishing public area preserves before they disappear or for personal body transformation

(Soper, 2007). The loss of traditions, experiences, opportunities and advantages which are no

longer available due to societal and corporate forces shifts the paradigm of desire from objects

available today to those that will never be present again (Soper, 2007). This yearning for

fulfillment doesn’t reside only in the individual, however; organized and determined groups of

citizens, either with an altruistic mindset or personal experience of injustice utilize their

collective citizenry to affect political change as well.

Collective Action

Just as escalating consumerism in the United States inspires individuals to change their

consumption practices, groups of citizens have shown to be particularly effective at collectively

politicizing their demands to the point of changing government and corporate practices. One

method with many examples of this comes in the form of boycotts, beginning as early as the

Boston Tea Party in 1773 (Jacobs, 2001). A different and sustained form of collected citizenry

can be viewed today at the site of Occupy Wall St; termed a social movement, this type of

consumption politics directs and acquires groups of Americans from across the country to protest

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 16

similar or identical political or corporate methodologies (Sandlin, 2005). A social media

revolution in the United States dubbed “Bank Transfer Day” directly resulted in the preemptive

dissolution of Bank of America’s recently announced debit card fee policy (Berman, 2011).

Soper (2005) contends that a third facet of cultural consumer education addressing collective

politicizing is the result of consumers critically questioning the entire system and structure of

consumption in the United States as it pertains to their lives and the lives of their fellow citizens,

creating anti-consumers (p. 177).

Aside from social movements like the Students Against Sweatshops, another tactic for

change is for citizens to “culture jam,” or to utilize the same strategies and mediums used for

advertisement against the enemy industries (Sandlin, p. 177). Organizations such as Adbusters

Media Foundation target television consumers by substituting advertisements for goods with

messages meant to break the ideological hold on citizens. As Leonard (2011) stated, the average

American views over 3000 advertisements each day, and “culture jammers” seek to break that

monotony by communicating anti-consumerist critical-thinking ideals directly, or as one scholar

put it, those on the weak end of the power spectrum are “able to use the resources provided by

the strong in their own interests, and to oppose the interests of those who provided the resources

in the first place” (Fiske, 2000, p. 314, as cited in Sandlin). Via collective actions, few are able to

propel the interests of the majority against the powers of the minority, despite varied results.

In Summary

Prior to the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), one can trace the

escalation of American consumerism using the thread of government-policy decisions, where it

preserved a booming national-turned-global economy born from a decisive military victory in the

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 17

Second World War. Suggestions for further research include examining how the implementation

of the Affordable Care Act has positively, or negatively, affected the areas stated above—in

terms of psychology and material wealth. Prior to the ACA, consumerism found traction through

advertisements and increasingly-sophisticated technology endorsing a myriad of goods while

simultaneously structuring individualistic identity formation through promoting superficial

political participation; sustained by a barrage of desire-inducing images beginning at infancy,

trends in consumption show the need to consume grows stronger over time unless deterred

(Stearns, 2006; Gans, 1998). While utilizing a cultural framework, one views this multi-

generational feat in terms of the relationship between those in power and those without (Sandlin,

2005). Reviewing the effects of this escalation with specific attention on the family unit show a

rising decrease in material wealth, a shift from the 1950s nuclear family, changes in parental

behavior as well as the manner in which families celebrate religion and holidays. Industry and

innovation inspired transformations of body and identity; in doing so, it also monetized the value

of health and brought detrimental consumerism into healthcare. Employing various methods of

consumer education can result in critically aware consumers and anti-consumers, drawing private

and public attention to corporate and government policies while inviting citizens to join together

in an effort for change.

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 18

References

Amato, P. R., & Keith, B. (1991). Parental Divorce and the Well-Being of Children: A Meta

Analysis. Psychological Bulletin, Volume 110, No. 1, 26-46. DOI: 10.1037/0033-

2909.110.1.26.

Bacevich, A. (October 5, 2008). He Told Us to Go Shopping. Now the Bill is Due. Washington

Post. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-

dyn/content/article/2008/10/03/AR2008100301977.html.

Berman, J. (November 4, 2011). Bank Transfer Day, Occupy Wall Street Share Sentiments, But

Take Different Approaches. Huffington Post. Retrieved from

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/11/04/bank-transfer-day-occupy-wall-

street_n_1077088.html.

Cantoni, D. (2009). The Economic Effects of the Protestant Reformation: Testing the Weber

Hypothesis in the German Lands. Harvard University Department of Economics. Job

Market Paper. Retrieved from http://www.econ.upf.edu/docs/seminars/cantoni.pdf.

Cohn, D., Livingston, G., Taylor, P., & Fry, R. (Novermber 7, 2011). The Rising Age Gap in

Economic Well-Being: The Old Prosper Relative to the Young. Pew Research Center.

Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2011/11/07/the-rising-age-gap-in-

economic-well-being/.

Dickler, J. (November 29, 2011). Record Black Friday Sales? Don’t Get Too Excited. Retrieved

from http://money.cnn.com/2011/11/29/pf/holiday_sales/.

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 19

Divorce in America. (2007). [Graph illustration October 24, 2013]. Daily Infographic. Retrieved

from http://www.dailyinfographic.com/divorce-in-america-infographic.

Featherstone, M. (2010). Body, Image and Affect in Consumer Culture. Body & Society, 16,

193-221. DOI: 10.1177/1357034X09354357

Gabriel, Y., & Lang, T. (1995). The Unmanageable Consumer. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gans, H. (1988). Middle American Individualism: The Future of Liberal Democracy. New York,

NY: The Free Press.

Gilleard, C., & Higgs, P. (1998). Old people are users and consumers of healthcare: a third

rhetoric for a fourth age reality. Ageing and Society, 18, 233-248. Cambridge University

Press.

Hayat, A. (November 29, 2011). Capitalism, Democracy, and the Occupy Wall Street Movement.

Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/ali-hayat/occupy-wall-

street-capitalism_b_1119247.html?ref=politics.

Hill, R. P. (2002). Consumer Culture and the Culture of Poverty: Implications for Marketing

Theory and Practice. Marketing Theory, 2(3), 273-293.

doi:10.1177/1470593102002003279

Kochhar, R., & Fry, R., & Taylor, P. (2011). Wealth Gaps Rise to Record Highs Between Whites,

Blacks, and Hispanics. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from

http://pewresearch.org/pubs/2069/housing-bubble-subprime-mortgages-hispanics-blacks-

household-wealth-disparity.

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 20

Lavine, H., & Sweeney, D., & Wagner, S. (1999). Depicting Women as Sex Objects in television

Advertising: Effects on Body Dissatisfaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,

25, 1049-1058. DOI: 10.1177/0461672992511012

Leonard, A. (2011). Story of Stuff, Referenced and Annotated Script. Retrieved at

http://dev.storyofstuff.org/wp-

content/uploads/2011/10/annie_leonard_footnoted_script.pdf.

Lindley, K. J., Glaser, D., Milla, P. J. (2005). Archive of Disease in Childhood, 90, 335-337.

DOI: 10.1136/adc.2003.032524

Newman, B. J. & Bartels, B. L. (2010). Politics at the Checkout Line: Explaining Political

Consumerism in the United States. Political Research Quarterly. DOI:

10.1177/1065912910379232.

Sandlin, J. (2005). Culture, Consumption, and Adult Education: Refashioning Consumer

Education for Adults as a Political Site Using A Cultural Studies Framework. Adult

Education Quarterly, Vol. 55, No. 3, p. 165-181. DOI: 10.1177/0741713605274626

Soper, K. (2007). Rethinking the ‘Good Life’: The citizenship dimension of consumer

disaffection with consumerism. Journal of Consumer Culture, 7, 205. DOI:

10.1177/1469540507077681

Stearns, P. (2006). Consumerism in World History: The global transformation of desire. New

York, NY: Routledge.

United States Census Bureau. (2010). Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates. Retrieved from

http://www.census.gov/did/www/saipe/data/highlights/files/2010highlights.pdf.

ESCALATING AMERICAN CONSUMERISM 21

Vornonitsky, M., Gottschalck, A., & Smith, A. (2011). Distribution of Household Wealth in the

US.: 2000 to 2011. Retrieved at

https://www.census.gov/people/wealth/files/Wealth%20distribution%202000%20to%202

011.pdf