Epi.2002.Checchi.transRoyalSocTropMedHyg.high Pf Resistance to CQ and SP in Harper Liberia Results...

-

Upload

derekwwillis -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

0

Transcript of Epi.2002.Checchi.transRoyalSocTropMedHyg.high Pf Resistance to CQ and SP in Harper Liberia Results...

-

8/14/2019 Epi.2002.Checchi.transRoyalSocTropMedHyg.high Pf Resistance to CQ and SP in Harper Liberia Results in Vivo and Analysis of Point Mutations

1/6

TRANSACTIONS OFTHEROYALSOCIETYOFTROPICALMEDICINEANDHYGIENE(2002)96,664-669High Plasmodium fa/ciparum resistance to chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in Harper, Liberia: results in vivo and analysis of pointmutationsF. Checchi, R. Durand, S. Balkan, B. T. Vonhm3, J. Z. Kollie, P. Biberson, E. Baron, J. Le Bras2 andJ.-P. Guthmann4 Mt?decins Suns Front&es, 8 rue Saint-Sub& 75011 Park, France; Laboratoire de Parasitologie-Mycologic, Hspital Bichat-Claude Bernard, 46 rue Hem-i Huchard, 75877 Park, France; 3Malana Control Program,Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, Monrovia, Liberia; 4Epicentre, 8 rue Saint-Sabin, 75011 Park, France

AbstractIn Liberia, little information is available on the efficacy of antimalarials against Plasmodium falciparummalaria. We measured parasitological resistance to chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) inHarper, south-west Liberia in a 28-d study in vivo. A total of 50 patients completed follow-up in thechloroquine group, and 66 in the SP group. The chloroquine failure rate was 74.0% (95% confidenceinterval [95% CI] 59.7-85.4%) after 14 d of follow-up and 84.0% (95% CI 70.9-92.8%) after 28 d (nopolymerase chain reaction [PCR] analysis was performed to detect reinfections in this group). In the SPgroup, the failure rate was 48.5% (95% CI 36.2-61.0%) after 14 d and 69.7% (95% CI 57.1-80.4%)after 28 d, readjusted to 51.5% (95% CI 38.9-64.0%) after taking into account reinfections detected byPCR. Genomic analysis of parasite isolates was also performed to look for point mutations associatedwith resistance. Genotyping of parasite isolates revealed that all carried chloroquine-resistant K-76Tmutations at gene pfcrt, whereas the triple mutation (S108N, N511, C59R) at dhfr and the A437Gmutation at dhps, both associated with resistance to SP, were present in 84% and 79% of pretreatmentisolates respectively. These results seriously question the continued use of chloroquine and SP in Harperand highlight the urgency of making alternative antimalarial therapies available. Our study confirms thatresistance to chloroquine may be high in Liberia and yields hitherto missing information on SP.Keywords: malaria, Plasmodium falciparum, chemotherapy, chloroquine, sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, resistance, pfcrt,dhfr dhps, Liberia

IntroductionEvery year in Africa according to a conservativeestimate approximately 200 million cases of PZasmo-dium falcip%rum malaria occur, of which at least onemillion result in death (SNOW et al.. 1999). Thisproblem is further aggravated by widespiead resistanceof l? falciparum to chloroquine (BLOLAND, 2001). Inspite of this, the drug is still the recommended first-linetherapy almost everywhere in Africa. Experience fromsouth-east Asia shows that resistance to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) rises quickly where it is introducedas monotherapy and reports of falling SF cure rates areaccumulating from East African sites where the drughas replaced chloroquine (R~NN et al., 1996; STAEDKEet al., 2001). A scenario may thus be unfolding inwhich entire regions of Africa are left without efflca-cious and affordable therapies for malaria (WHITE etal., 1999).The principal tool to measure resistance to antima-larials remains the assessment of therapeutic efficacy invivo. Conclusions of studies in vivo may, however, bere-enforced by related genomic analyses of DNA pointmutations associated with l? falciparum resistance toantimalarials. Recently, chloroquine resistance in vivohas been conclusively linked to the K-76T mutation inthe pfcrt gene (WELLEMS & PLOWE, 2001). Similarly,many studies report tha t point mutations in the dhfrgene are linked to pyrimethamine resistance (DOUMBOet al., 2000) and that SP treatment failure in vivo isassociated with the simultaneous occurrence of suchmutations, notablv at dhfr codons 5 1, 59, and 108(NAGESH~ et al, 2001). Point mutatidns &-I the dhpsgene have also been associated with sulfadoxine resis-tance in vitro (TRIGLIA et al., 1997).In Liberia, chloroquine and SP are respectively thefirst- and second-line therapies for malaria. Surveil-lance of antimalarial resistance has been scanty with

Address for correspondence: Jean-Paul Guthmann, Epicentre,8 rue Saint-Sabin, 75011 Paris, France; phone +33 1 40 21 2848, fax +33 1 40 21 28 03,e-mail [email protected]

only 5 studies conducted from 1993 to 1999, reportingchloroquine failure rates in vivo between 5% and 38%(B. Vonhm et al., unpublished report). Moreover, toour knowledge no studies of resistance to SP have everbeen conducted in Liberia.Since 1997, Medecins Sans Frontihes (MSF) hasbeen supporting a hospital in the south-eastern Liber-ian city of Harper, the only secondary health carefacility for a catchment area of some 90000 people.According to MSF records, malaria is the most impor-tant health problem in Harper, accounting between1998 and 2000 for about one-third of all consultations(400-450 cases per month, diagnosed mostly on clin-ical signs), and a similar proportion of admissions andhospital deaths. Among children aged < 5 years, thedisease is responsible for almost half o f cases anddeaths. Transmission (represented by monthly out-patient consultations) seems stable year-round and l?falciparum is responsible for nearly all infections (97%)according to hospital laboratory records.Results of 2 14-d efficacy studies in vivo conductedin areas surrounding Harper suggested that antimalar-ial efficacy was declining in this region. In Pleebodistrict (north of Harper) chloroquine resistance was23% (B. Vonhm et al., unpublished report) and, inTabou district of the Ivory Coast (an area across theborder to which Harper residents fled during the1989-96 Liberian civil war), 45% resistance to chloro-quine and 6% resistance to SP were found (VILLADARYet al. 1997). These results, combined with the hugeburden of P: falciparum malaria on site, prompted us tocarry out a &dy&irz viva of parasitological reiistance tochloroauine and SP in Harrier. Genomic analvsis ofparasiti isolates collected duiing the study in v&o wasalso performed, in which polymerase chain reaction(PCI?) genotyping methods-w&e employed to look formarkers of resistance to both chloroauine (K-76T pfcrtmutation) and SP (S108N, N511, ana C59kmuta&nsof dhfr and the A437G mutation of dhps). Study pa-tients were recruited from the outpatient departmentsof 11 Dossen Memorial Hospital and Sacred HeartCl& in Harper. The study was approved and sup-norted bv the Liberian Ministry of Health and SocialiWelfare. .

-

8/14/2019 Epi.2002.Checchi.transRoyalSocTropMedHyg.high Pf Resistance to CQ and SP in Harper Liberia Results in Vivo and Analysis of Point Mutations

2/6

PLASMODIUM FALCIPARUM DRUG RESISTANCE

Materials and MethodsSample sizeFor samnle size determination in the study in vivo, aresistance ;o ch loroquine of 40% was hypothesized,with a desired urecision of 10%. Similarlv. 10% resis-tance to SP was estimated, to be detected with 7.5%precision. At a significance level of 0.05 and with apower of 0.80, we required 93 inclusions in the chloro-quine group and 62 in the SP group. Including a 10%loss to follow-up, a target o f 171 inclusions was thusset.Enrolment proceduresOur methodology in vivo was an adaptation of theWHO (1996) protocol for the assessment of therapeu-tic efficacy of antimalarial drugs in areas of intensetransmission. Accordingly, clinicians were asked torefer to the study all children aged 6-59 months withclinically suspected malaria. Referrals were assessed bya study clinician and sent to the laboratory, where thickand thin blood films were obtained. Children wereeligible for enrolment if they met the following inclu-sion criteria: (i) age 6-59 months; (ii) fever (axillarytemperature 2 37.5 C) or history of fever in the past24 h; (iii) l? falciparum monoinfection with asexualparasitaemia 1OOO- 100 OOO/pL; and (iv) residence lessthan 1 h walking distance from the hospital. Exclusioncriteria were: (i)-danger signs or signs of severe malaria(WHO. 1996): (ii) nresence of concomitant febrileillnesses; (iii) serious underlying condition; (iv) historyof allergy to either chloroquine or SF; and (v) anyantimalarial intake in the past 7 d according to theparent or guardians account. Written informed con-sent was obtained from parents and guardians of allchildren enrolled. A llocation to either the chloroquineor SP treatment group was randomized.Treatment and follow-upChildren in the chloroquine group received25 mg/kg bodyweight of oral chloroquine (I 50 mg basetablets, Laboratoires Creat, Vernouillet, France) over3 d (10 mg/kg on day 0 , 10 mg/kg on day 1, and5 mg/kg on day 2). Patients in the SP group received asingle dose of oral SP tablets (500 mg sulfadoxi-ne + 25 mg pyrimethamine, Fansida@, LaboratoiresCreat) on day 0 (at 1.25 mg/kg bodyweight pyrimetha-mine). Dosages were expressed as fractions of tablets.Study d rug administration on days 0, 1, and 2 occurredon site and was directly observed for 30 min. Tabletswere crushed in small amounts of water if needed, andreadministered in case of vomiting after a 30-min restperiod.After the treatment period, all parents and guardianswere asked to bring the ir children for follow-up visitson day 3, day 7, day 14, and day 28 (or any other day ifthe childs condition was of concern). At each visit, aclinical assessment was made by the nurse clinician andthick and thin films were obtained. Children who metthe definitions of treatment failure received immediaterescue treatment: this consisted of SP 1.25 m&kgfor chloroquine failures, and quinine hydroch&ide10 mg/kg/8 h for 5 to 7 d for SP failures. Defaulterswere traced by a home visitor and encouraged to returnas soon as possible: if they did not return after 2 homevisits, they were considered lost to follow-up. Patientswere withdrawn from the study for any of the followingreasons: (i) failure to take any study d rug dose; (ii)vomiting any study dose twice; (iii) severe allergicreaction to the study drug; (iv) onset of a non-malariafebrile illness during follow-un; (v) self-medication withantimalarials during follow-upf and (vi) decision ofparent/guardian.Therapeutic outcomesPatients were classified as early treatment failure(ETF) if they met the following criteria: (i) progression

665

to severe malaria on days 1, 2, or 3; (ii) parasitaemia ondav 2 higher than on dav 0 in the nresence of fever; (iii)any parisitaemia in thhpresence-of fever on day 3: or(iv) day 3 parasitaemia 2 25% of the day 0 count,irrespective of fever. Patients were classified as latetreatment failure (LTF) if any parasitaemia was ob-served after the day 3 visit, irrespective of symptoms.All others were classified as adequate treatment re-sponse (ATR), provided that they completed per-pro-tocol follow-up.Laboratory proceduresThick and thin films were Giemsa-stained (10%dilution for 13 min) and asexual counts were obtainedon the thick smear bv counting the number of tro-phozoites against 206 leucocytes (white blood cells[WBC]), assuming a normal blood level of 8000WBC/uL. A sample of thick slides was re-read by anexperienced technician. Capillary blood samples- forgenomic analysis were collected on Whatmann No. 3filter-paper in 50 + aliquots, dried, and stored in thedark in sealed bags at room temperature. Parasite DNAwas extracted using Chelex-100 Resin (Bio-Rad La-boratories, Hercules, CA, USA) as described elsewhere(PLOWE et al., 1995).PCR genotyping for detection of reinfectionsCapillary blood samples were analysed to distinguishrecrudescences from reinfections according to a meth-od previously described (SNOUNOU et al., 1999). Apolymorphic region of the l? falciparum msp2 gene wasamplified by nested PCR and amplification productswere run on a 2% agarose gel. The band profiles ofpaired pretreatment and failure-day samples were thencompared. Paired samples with different band profileswere classified as reinfections and similar band profileswere classified as a recrudescence. Similar profiles withadditional or missing bands in either sample were alsoclassified as a recrudescence: the difference in the num-ber of bands was explained by selection of previouslyundetected clones, presence of a novel infection super-imposed on the recrudescent one or disappearance ofdrug-sensitive clones present in the pretreatment infec-tion. For logistical reasons PCR genotyping could notbe performed in the chloroquine group.Analysis of resistance markersThe amplification of a portion of the pfcrt genespanning codon 76 was performed as previously de-scribed (DURAND et aZ., 2001). Codon 108 of the dlzfigene was determined by PCR and molecular beaconsas nreviouslv described (DURAND et al.. 2000). A 116-bp-DNA fragment spanning codons 51 and 59 of thedhfi gene and a 525&p DNA fragment spanning codon437 of the dhas gene were also amnlified. The se-quences of prime& used were as follows: dhfi 51, 595-CACATTTAGAGGTCTAGGAAATAAAGGA-3(sense) and 5-TCAATTTTTCATATTTTGATTCATTCAC-3 (antisense), dhps 437 5-TTTGTTGAACCTAAACGTGCTG-3 (sense) and 5-TCTTCGCAAATCCTAATCCAAT-3 (antisense). Amplifi-cations were performed in a 25 @ reaction mixturecontaining 0.3 @vl of each primer, 200 @vl of dNTPs,buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 1 mMMgC&), and 0.5 U of Thermus aquaticus DNA poly-merase (AmpliTaq GoldTM, Perkin Elmer, Branchburg,NJ, USA). The samples were incubated for 7 min at95 C for denaturation prior to cycles (94 C X 45 s,56 C [dhfi 51 and 591 or 59 C [dhps 4371 X 45 s, and72 C X 45 s). After 30 cycles, primer extension wascontinued for 5 min at 72 C. PCR products of pfcrt,dhfr, and dhps genes were sequenced by use of an-ABIPRISM@ Big: Dve Terminator Cvcle seauencinn K it(Perkin-Elm& detus@) following* the manufact~rersprotocol (P/N 4303149 Revision C, 1998). PCR pro-ducts were purified by use of a QIAquick@ PCR Pur-

-

8/14/2019 Epi.2002.Checchi.transRoyalSocTropMedHyg.high Pf Resistance to CQ and SP in Harper Liberia Results in Vivo and Analysis of Point Mutations

3/6

666

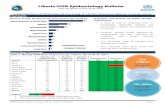

ification Kit (Qiagen@, Hilden, Germany). FluorescentPCR products were sequenced in an ABI [email protected] entry and analysisData were entered on Epi-Info 6.04 software (CDC,Atlanta, GA, USA) and individually checked for accu-racy. Failure rates for each drug were expressed as thenumber of failures (ETF and LTF) over the total num-ber of patients followed-up according to protocol, withassociated 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Re-infections detected by PCR analysis were reclassified asATR. Failure rates in the 2 treatment groups werecompared by Mantel-Haenszel x2 test.ResultsResponse to chloroquine and SP treatmentIn total, 311 children were referred to the studybetween September and November 2000, out of whom141 were included (Figure). Of the 170 exclusions, 65(38%) had a history of previous antimalarial intake, 57(34%) presented with concomitant acute respiratoryinfection or otitis, 52 (3 1%) had a negative smear, and47 (28%) had a parasite density below the inclusionthreshold. Children treated with chloroquine and SFwere similar in their baseline characteristics (Table 1).Parasitaemia was generally low: only 27/141 children(19%) had a density above 10 OOO/pL. The apparentdifference in gender ratio was not statistically signifi-cant (P = 0.46).Due to the alarming preliminary results, chloroquineenrolment was ended early, and a total of 61 childrenwere assigned to this group. As can be seen from theFigure, 50 children (82%) completed 14-d and 28-dfollow-up. Table 2 shows the therapeutic responses of

F. CHECCHI ETAL.

the children to chloroquine at day 14 and day 28.Overall, a mere 8/50 (16%) of children treated withchloroquine completed 28 d of follow-up without ex-periencing recurrent parasitaemia.In the SP group, 80 children were included; 68(85%) completed 14 d of follow-up, and 66 (83%)completed 28 d (Figure). Only 20/66 (30%) of chil-dren treated with SP responded to treatment andremained parasite-free for the duration of follow-up(Table 2). PCR analysis was performed on 15 out ofthe 36 late failures in the SP group (42%) and 5reinfections and 10 recrudescences were detected. As-suming that the 21 failures not genotyped were recru-descences, the PCR-adjusted day 28 failure rate for SPthus becomes 41/66 (62.1%, 95% CI 49.3-73.8%).Alternatively, we can apply the proportion of reinfec-tions observed among the 15 LTF genotyped (5/15) tothe 21 LTF not genotyped, and extrapolate a morerealistic SP failure rate of 34/66 (51.5%, 95% CI38.9-64.0%).SP was significantly better than chloroquine in termsof proportion of early failures (15% vs. 36%, P = 0.01)and failure rate at day 14 (49% vs. 74%, P=O.O06).No statistical difference in baseline characteristics wasobserved between children who completed the studyand study withdrawals/losses to follow-up. A qualitycontrol of malaria diagnosis, performed on 109 slides(11% of total), yielded 93.3% agreement.Results of genomic analysisThe pfcrt 76 codon was determined in pretreatmentisolates from 23 children. All isolates carried the K-76T mutation, either alone (21 isolates) or mixed withthe wild-type allele (2 isolates). The K-76T mutationwas also found in 7 out of 7 post-chloroquine treatment

-v., 170 excluded /f141 includedr;..-l.reatment allocation

1 6 1 treated with CO 1 t/ 80 treated withSl 1/9 withdrawn

6 acute respiratmyinfection

.1 meningitis1 severe injury1 mistakenly received

rescue medication2 lost to follow-up

I / I

pg. l lIPiefollow-up

I

9 withdrawn6 acute respiratory

infection

.1 measles1 unknown fever1 mistakenly received

rescue medication2 lost to follow-up

Figure. Study enrolment details for 311 children with clinically suspected malaria, Harper, Liberia, 2000.

-

8/14/2019 Epi.2002.Checchi.transRoyalSocTropMedHyg.high Pf Resistance to CQ and SP in Harper Liberia Results in Vivo and Analysis of Point Mutations

4/6

667LASMODIUM FALCIPARUM DRUG RESISTANCETable 1. Baseline characteristics of 141 study children, Harper, Liberia, 2000

Treatment groupCharacteristicMean (SD) age (months)Gender ratio (M/F)Mean (SD) weight/height as % of medianMean (SD) initial axillary temperature (C)Geometric mean (range) initial parasitaemia (/pL)SF,sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine.

Chloroquine (n = 61)22.0 (13.9)0.91 (29132)98.1 (8.4)37.9 (0.9)4016 (1000-90 000)

SP (n = 80)26.2 (15.6)0.70 (33/47)97.8 (7.8)37.9 (1.1)4111 (1000-23780)

Table 2. Therapeutic response of study children to chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine at day14 and day 28, unadjusted for polymerase chain reaction analysis, Harper, Liberia, 2000Chloroquine Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine

Outcome at day 14Early treatment failureLate treatment failureFailureAdequate treatment responseTotalOutcome at day 28Early treatment failureLate treatment failureFailureAdequate treatment responseTotal

n (%I 95% CI n (%I 95% CI18 22.9-50.8 10 7.3-25.419 lZi 24.7-52.8 23 fEj 22.8-46.337 59.7-85.4 36.2-61.013 g:g 14.6-40.3 2; g;j 39.0-63.850 (1oo:o) 68 (1oo:o)18 22.9-50.8 1024 33.7-62.6 36 i:z; 7.5-26.141.8-66.942 70.9-92.8 467.2- 29.1 20 ~;;I:{ 57.1-80.419.6-42.966 (100.0)

95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

failure isolates. DNA sequencing also showed a veryhigh frequency of a triple dhfr mutation at codons 108,51, and 59 (S108N, N511, C59R): 21 out of 25pretreatment isolates (84%) and all (17/17) post-SPtreatment isolates had triple dh fr mutants. Among the14 tested pretreatment isolates, 11 (79%) possessed theA437G mutation at gene dhps, either alone (6 isolates)or mixed with the wild-type allele (5 isolates); 3 isolateshad the wild-type allele alone. Nine isolates carryingthe A437G mutation at gene dhps also had the tripledhfr mutation.DiscussionResults o f this study in viva showed alarming levelsof parasitological resistance to both chloroquine andSP in this area of Liberia. The true parasitologicalfailure rate for chloroquine may be somewhere between74.0% (result at day 14) and 84.0% (result at day 28).Given the intensity of transmission, many episodes ofrecurrent parasitaemia occurring between day 14 andday 28 are likely to have been reinfections. Even if weonly consider results up to day 14, our study suggeststhat resistance to chloroquine has reached unacceptablelevels in Harper. Of particular concern among childrentreated with this drug is the high proportion of earlyrecrudescences (36%).Our results for chloroquine in viva are further corro-borated by findings of the related genomic analysis.The ubiquity of the pfcrt I

-

8/14/2019 Epi.2002.Checchi.transRoyalSocTropMedHyg.high Pf Resistance to CQ and SP in Harper Liberia Results in Vivo and Analysis of Point Mutations

5/6

F. CHECCHI TAL.Referencesrom areas where the drug is not used as first-linetherapy (MUTABINGWA et al., 2001). The rapid selec-tion of dhfr point mutations at codons 108, 51, and 59under antifolate pressure has also been described(DOUMBO et al., 2000). In any case, these findings onceagain show the ease with which mutations encoding

resistance to SP arise and support the hypothesis thatSP monotherapy will have a limited lifespan in Africa.Our estimates of resistance in viva rely on a parasito-logical definition of recrudescence and might have beenlower had we used the WHO (1996) definitions of LTF(parasitaemia if accompanied by fever). Nevertheless,evidence shows that most children who remain para-sitaemic after antimalarial therapy eventually developsymptoms (thereby fulfilling the clinical criteria of fail-ure); however, this often occurs beyond the follow-upperiod, thus leading to misclassification of failures asadequate responders (BLOLAND et al., 1993; MUTA-BINGWA et al., 2001). In any case, we consider thatabsence of symptoms (fever) should not lead to classifi-cation of parasitological recrudescences as adequateresponses. In addition, when the study population con-sists of children and there is a strong suspicion of highresistance to the study drug, failure to administer im-mediate rescue medication to asymptomatic failurescarries considerable risks for the patient, notably sud-den aggravation and further decline in haemoglobinlevels, with consequent risk of severe anaemia if para-sitaemia persists (SLUTSI(ER t al., 1994).In Harper, low chloroquine and SP efficacy is likelyto lead to increased malaria-related morbidity andmortality, as demonstrated in other settings (TRAPE,2001). The effect might be particularly dire in this poorcommunity, where resources to prevent infective ano-pheline mosquito bites are limited and, apart fromquinine, no other therapies are available. Our resultsthus underline the urgent need to deploy more effica-cious antimalarials as Replacement for boih chloroquineand SP in Haroer. Combinations based on artemisininderivatives off& the fastest reduction in parasitaemia,lead to greatly improved cure rates and may reducecommur&y tr&sm&sion of the disease becausk of theirsametocidal effect (WHITE & OLLIARO, 1996). Theartemisinin componknt, however, must be associatedwith a sufficiently efficacious partner drug. Amodia-quine seemed like a possible candidate for an artesu-nate combination therapy in Harper, and a study of itsefficacy has been conducted (CHECCHI et al., 2002).Elsewhere in Liberia, chloroquine remains the main-stay of antimalarial treatment, with SP as second-linetherapy. While care should be taken to extrapolatethese results to other sites in the country, our studydoes show that chloroquine-resistant l? falciparumstrains may be highly prevalent throughout this region.It also provides hitherto missing information on resis-tance to SF in Liberia. We strongly recommend thatsurveillance of antimalarial resistance in Liberia andneighbouring regions be intensified and include bothchloroquine and SP at multiple sentinel sites.

AcknowledgementsWe thank the children and families who consented toparticipate in this study. We are grateful for the excellent workof our study team members (data collector Andrew Colley,laboratory technician Alfred Nyuma, nurse aide Agatha Satia,home visitors Robert Kun and John Weah, counsellor NanuYancy) and for the support of clinicians and authorities of JJDossen Hospital and Sacred Heart Clinic. Many thanks toKatleen Willems and Katherine Johnson, for the quality con-trol of malaria slides, and to Sayeh Jafari for sequencing ofparasite DNA. Thanks also to Dounia Bitar, Marc Gastellu,Graziella Godain and Brigitte Vasset (MSF headquarters,Paris), for support and advice during the study, and to Domin-ique Legros (Epicentre) for advice and technical review of themanuscript.

Basco, L. K., Tahar, R., Keundjian, A. & Ringwald, P.(2000). Sequence variations in the genes encoding dihy-dropteroate synthase and dihydrofolate reductase and clin-ical response to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in patients withacute uncomplicated falcipalum malaria. 3ournal of InfectiousDiseases, 182, 624-628.Bloland, P. B. (2001). Drug resistance in malaria. Geneva:World Health Organization, WHO/CDSICSRIDRS/2001.4.Bloland, P. B., Lackritz, E. M., Kazembe, P. N., Were, J. B.O., Steketee, R. J. & Campbell, C. C. (1993). Beyondchloroquine: implications of drug resistance for evaluatingmalaria therapy efficacy and treatment policy in Africa.Journal of Infectious Diseases, 167, 932-937 .Bojang, K. A., Schneider, G., Forck, S., Obaro, K., Jaffar, S.,Pinder, M., Rowley, J. & Greenwood, B. M. (1998). A trialof Fansida@ plus chloroquine or Fansidarm alone for thetreatment of uncomplicated malaria in Gambian children.Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine andHygiene, 92, 73-76.Checchi, F., Balkan, S., Vonhm, B. T., Massaquoi, M.,Biberson, P., Eldin de Pecoulas, P., Brasseur, P. & Guth-mann, J.-P. (2002). Efficacy of amodiaquine for uncompli-cated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Harper, Liberia.Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine andHygiene, 96, 670-673.Diourtk, Y., Djimdk, A., Doumbo, 0. K., Sagara, I., Couli-baly, Y., Dicko, A., Diallo, M., Diakitb, M., Cortese, J. F. &Plowe, C. V. (1999). Pyrimethamine-sulfadoxine efficacyand selection for mutations in Plasmodium falciparum di-hydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthase in Mali.American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 60 ,475-478.Doumbo, 0. K., Kayentao, K., Djimde, A., Cortese, J. F.,Diourte, Y., Konare, A., Kublin, J. G. & Plowe, C. V.(2000). Rapid selection of Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofo-late reductase mutants by pyrimethamine prophylaxis. 302~nal of Infectious Diseases, 182, 993-996.Durand, R., Eslahpazire, J., Jafari, S., Delabre, J. F., Marmor-at-Khuong.. A.. Di Piazza. 1. P. & Le Bras. 1. (2000). Use ofmolecular-beacons to de&t an antifola& resistance-asso-ciated mutation in Plasmodium falciparum. AntimicrobialAgents and Chemotherapy, 44, 3461-3464.Durand. R.. Tafari. S.. Vauzelle. 1.. Delabre. T. F.. Tesic. Z. &Le Bias, J: (2061): Analysis

-

8/14/2019 Epi.2002.Checchi.transRoyalSocTropMedHyg.high Pf Resistance to CQ and SP in Harper Liberia Results in Vivo and Analysis of Point Mutations

6/6

PLASMODIUM FALCIPARUM DRUG RESISTANCE 669

in Tanzania. Transactions of the Royal Society of TropicalMedicine and Hygiene, 90, 179- 18 1.Slutsker, L., Taylor, T. E., Wirima, J. J. & Steketee, R. W.(1994). In-hospital morbidity and mortality due to malaria-associated severe anaemia in two areas of Malawi withdifferent patterns of malaria infection. Transactions of theRoyal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 88, 548-55 1.Snounou, G., Zhu, X., Siripoon, N., Jarra, W., Thaithong, S.,Brown, K. N. & Viriyakosol, S. (1999). Biased distributionof mspl and msp2 allelic variants in Plasmodium falcipaumpopulations in Thailand. Transactions of the Royal Society ofTropical Medicine and Hygiene, 93, 369-374.Snow, R. W., Craig, M., Deichmann, U. & Marsh, K. (1999).Estimating mortality, morbidity and disability due to malar-ia among Africas non-pregnant population. Bulletin of theWorld Health Organization, 71, 624-640 .Staedke, S. G., Kamya, M. R., Dorsey, G., Gasasira, A.,Ndeezi, G., Charlebois, E. D. & Rosenthal, I. J. (2001).Amodiaquine, sulfadoxineipyrimethamine, and combina-tion therapy for treatment of uncomplicated falciparummalaria in Kampala, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet,358,368-374. - -Trape, J.-F. (2001). The public health impact of chloroquineresistance in Africa. American Journal of Tropical Medicineand Hygiene, 64, supplement 1, 12- 17.Triglia, T., Menting, J. G. T., Wilson, C. & Cowman, A. F.(1997). Mutations in dihydropteroate synthase are respon-

sible for sulfone and sulfonamide resistance in Plasmodiumfalciaarum. Proceedings of the National Academv of Sciences of