EnergyPolicy SolarPowerintheUS Perez Zweibel Hoff

-

Upload

dhita-rurin-adistyaningsih -

Category

Documents

-

view

220 -

download

0

Transcript of EnergyPolicy SolarPowerintheUS Perez Zweibel Hoff

-

8/14/2019 EnergyPolicy SolarPowerintheUS Perez Zweibel Hoff

1/16

-

8/14/2019 EnergyPolicy SolarPowerintheUS Perez Zweibel Hoff

2/16

R.Perez,K.Zweibel,T.Hoff

Figure1:Comparingfiniteandrenewableplanetaryenergyreserves(Terawattyears).

Totalrecoverablereservesareshownforthefiniteresources.Yearlypotentialisshown

fortherenewables(source:Perez&Perez,2009a)

2 6 per year2009 World energyconsumption

16 TWy/year

COAL

Uranium

900Total reserve

90-300Total

Petroleum

240total

Natural Gas

215

total

WIND

Waves1

0.2-2

25-70per year

OTEC

Biomass

3 -11 per year

HYDRO

3 4 per year

TIDES

SOLAR10

23,000 TWy/year

Geothermal0.3 2 per year

R. Perez et al.

0.3 per year2050: 28 TWy

finiterenewable

EuropeandAsia.Without incentives,however,theneededrevenuestreamforsolargenerationisstill

considerably higher than the least expensiveway to generate electricity today, i.e., viaunregulated,

minemouth coal generation. This large apparent gridparity gap canhinder constructivedialogue

with keydecisionmakers and constitutes apowerful argument toweakenpolitical support for solar

incentives,especiallyduringtightbudgetarytimes.

Inthispaper,weapproachtheapparentgridparitygapquestiononthebasisofthefullvaluedelivered

bysolarpowergeneration. Wearguethattherealparitygap i.e.,thedifferencebetweenthisvalue

andthecost todeploy the resource isconsiderablysmaller thantheapparentgap,andthat itmay

well have already been bridged in several parts of theUS. This argumentation is substantiated and

quantifiedbyfocusingonthecaseofPVdeploymentinthegreaterNewYorkCityarea.Sincethisisnot

oneof the sunniestplaces in theUS, thispaper should serve as an applicable case toother regions

and/orsolartechnologies.

SolarResource

Fundamentals

Itisusefultofirstreviewacoupleoffundamentalfactsaboutthesolarresourcethatarerelevanttoits

value.

Vastpotential:Firstandforemost,thesolarenergyresourceisverylarge(Perezetal.,2009a).Figure1

comparesthecurrentannualenergyconsumptionoftheworldto(1)theknownplanetaryreservesof

thefinitefossilandnuclearresources,and(2)totheyearlypotentialoftherenewablealternatives.The

volume of each

sphere represents

the total amount

of energy

recoverable from

the finite reserves

and the annual

potential of

renewable

sources.

While finite fossil

and nuclear

resourcesarevery

large,particularly

coal, they are not

infiniteandwould

lastatmosta few

generations,

notwithstanding

theenvironmental

-

8/14/2019 EnergyPolicy SolarPowerintheUS Perez Zweibel Hoff

3/16

R.Perez,K.Zweibel,T.Hoff

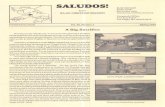

Figure2:Cloud

cover

during

aheat

wave

in

the

US

impactthatwillresultfromtheirfullexploitation ifnowuncertaincarboncapturetechnologiesdonot

fullymaterialize.Nuclear energymaynotbe the carbonfree silverbullet solution claimedby some:

putting aside the environmental and proliferation unknowns and risks associatedwith this resource,

therewouldnotbeenoughnuclearfueltotakeovertheroleoffossilfuels1.

Therenewable

sources

are

not

all

equivalent.

The

solar

resource

is

more

than

200

times

larger

than

all

the others combined.Wind energy could probably supply all of the planets energy requirements if

pushed toaconsiderableportionof itsexploitablepotential.However,noneof theothersmostof

whichare firstandsecondorderbyproductsof thesolar resource could,alone,meet thedemand.

Biomass in particular could not replace the current fossil base: the rise in food cost that paralleled

recentrisesinoilpricesandthedemandforbiofuelsissymptomaticofthisunderlyingreality.

On theotherhand,exploitingonlyaverysmall fractionof theearthssolarpotentialcouldmeet the

demandwithconsiderableroomforgrowth.Thus,leavingthecost/valueargumentationasidefornow,

logic alone tells us, in view of available

potentials, that the planetary energy

futurewillbe solarbased. Solarenergy

is the only readytomassdeployresource that is both large enough and

acceptableenoughtocarrytheplanetfor

thelonghaul.

Builtin peak load reduction capability:

For a utility company, Combined Cycle

GasTurbines (CCGT)arean ideal source

of variable power generation because

theyaremodular,canbequicklyramped

upordownandanswerthequestion:is

poweravailable

at

will?

As

such

CCGT

haveahighcapacityvalue.

Solar generators, distributed PV in

particular, arenot available atwill2,but

theyoftenanswerasimilarquestion:is

power availablewhen needed? and as

such can capture substantial effective

capacityvalue(Perezetal.,2009b). This

is because peak electrical demand is

driven by commercial daytime air

conditioning

(A/C)

in

much

of

the

US

reachingamaximumduringheatwaves.

1Ofcoursethisstatementwouldhavetoberevisitedifanacceptablebreedertechnologyornuclearfusion

becamedeployable.Nevertheless,shortoffusionitself,evenwiththemostspeculativeuraniumreservesscenario

andassumingdeploymentofadvancedfastreactorsandfuelrecycling

,thetotalfinitenuclearpotentialwould

remainwellbelowtheoneyearsolarenergypotential(ref1)2ConcentratingSolarPower(CSP)technologyhasseveralhoursofbuiltinstorageandcouldbepartiallyavailable

atwill.

-

8/14/2019 EnergyPolicy SolarPowerintheUS Perez Zweibel Hoff

4/16

R.Perez,K.Zweibel,T.Hoff

Thefuelofheatwaves isthesun;aheatwavecannottakeplacewithoutamassive localsolarenergy

influx.ThebottompartofFigure2illustratesanexampleofaheatwaveinthesoutheasternUSinthe

springof2010andthetoppartofthe figureshows thecloudcoveratthesametime:thequalitative

agreementbetweensolaravailabilityandtheregionalheatwave isstriking.Quantitativeevidencehas

also shown that themean availabilityof solar generationduring the largestheatwavedriven rolling

blackoutsintheUSwasnearly90%ideal(Letendreetal.2006).Oneofthemostconvincingexamples,

however, is the August 2003Northeast blackout that lasted several days and cost nearly $8 billionregionwide (Perez et al., 2004). The blackout was indirectly caused by high demand, fueled by a

regionalheatwave3.As littleas500MWofdistributedPV regionwidewouldhavekeptevery single

cascadingfailure fromfeeding intooneanotherandprecipitatingtheoutage.Theanalysisofasimilar

subcontinentalscale blackout in the Western US a few years before that led to nearly identical

conclusions(Perezetal.,1997).

Inessence,thepeakloaddriver,thesunviaheatwavesandA/Cdemand,isalsothefuelpoweringsolar

electric technologies.Becauseof thisnatural synergy, the solar technologiesdeliverhardwiredpeak

shavingcapability for the locations/regionswith theappropriatedemandmix peak loadsdrivenby

commercial/industrialA/C that is to say,muchofAmerica.Thiscapability remains significantup to

30%capacity

penetration

(Perez

et

al.,

2010),

representing

adeployment

potential

of

nearly

375

GW

in

theUS.

Renewable energy breeder: The mainstream (crystalline silicon PV) solar electric technology has a

proven recordof lowdegradation (

-

8/14/2019 EnergyPolicy SolarPowerintheUS Perez Zweibel Hoff

5/16

R.Perez,K.Zweibel,T.Hoff

(2) Theutilityanditsratepayerswhopurchasetheenergyproducedbytheplant;4(3) Thesocietyat largeand itstaxpayerswhocontributeviapublicR&Dandtaxbased incentives

andreceivebenefitsfromtheplant.

The transaction is often perceived as onesided in favor of the investor/developerwhose return on

investment

e.g.,

the

necessary

20

30

cents

breakeven

cash

flow

equivalent

for

distributed

PV

is

forced upon the two other parties. However, these parties do receive tangible value from solar

generation.

Valuetotheutilityanditsratepayersaccruesfrom:

Transmission(wholesale)energy,611/kWh:energygeneratedlocallybysolarsystemsisenergythatdoesnotneedtobepurchasedonthewholesalemarketsattheLocationalbasedMarginal

Pricing(LMP).Perez&Hoff(2008)haveshownthatinNewYorkState,thevalueoftransmission

energyavoidedby locallydeliveredsolarenergyrangedfrom6to11centsperkWh,withthe

lower number applying to the wellinterconnected western NY State area, and the higher

numberapplyingtotheelectricallycongestedNewYorkCity/LongIslandarea.Thisismorethan

themean LMP in both cases (respectively 5 and 9 cents per kWh) because solar electricity

naturallycoincideswithperiodsofhighLMP.

Transmission capacity, 05 /kWh: becauseof demand/resource synergydiscussed above, PVinstallationscandelivertheequivalentofcapacity,displacingtheneedtopurchasethiscapacity

elsewhere, e.g., via demand response (Perez&Hoff, 2008). In the above study, Perez et al.

calculated the effective capacity creditof lowpenetration PV inmetropolitanNew York and

showedthatPVcouldreliablydisplaceanannualdemandresponseexpenseof$60perinstalled

solarkW,i.e.,amountingto4.5centsperproducedsolarKWh5.

Distributionenergy(losssavings),01/kWh:distributedsolarplantscanbesitednearthe loadwithinthedistributionsystemwhetherthissystem isradialorgriddedtherefore,theycan

displace electrical losses incurred when energy transits from power plants to loads on

distributionnetworks(thisisinadditiontotransmissionenergylosses).Thislosssavingsvalueis

ofcoursedependentuponthe locationandsizeofthesolarresourcerelativetothe load,and

uponthespecsofthedistributiongridcarryingpowertothecustomer.Adetailedsitespecific

study in theAustin Electric utilitynetwork (Hoff et al., 2006) showed that loss savingswere

worthinaverage510%ofenergygeneration.InthecaseofNewYorkthiswouldthusamount

to0.51centperkWh.

Distribution capacity, 03 /kWh: As with transmission capacity, distributed PV can delivereffectivecapacityatthefeederlevelwhenthefeederloadisdrivenbyindustrialorcommercial

A/C,hencecan reduce thewearandtearof the feedersequipmente.g., transformers as

well as defer upgrades, particularly when the concerned distribution system experiences

growth. As above, this distribution capacity value is highly dependent upon the feeder and

4Sometimesthisentitymaybereplacedbyadirectcustomerasisdoneinpowerpurchaseagreements(PPAs)

however,becausetheutilitygridisalwaysthebuffer/conduitofsolarenergygeneration,PPAornot,thebig

picturecostvalueequationremainsthesame.51kWofPVinNewYorkStategenerateson~1,350KWh/year.Therefore$60perkWperyearamountsto4.5

centsperkWhproduced.

-

8/14/2019 EnergyPolicy SolarPowerintheUS Perez Zweibel Hoff

6/16

R.Perez,K.Zweibel,T.Hoff

Figure3:Finiteenergycommoditypricetrends20072011

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

2007 2007.5 2008 2008.5 2009 2009.5 2010 2010.5 2011

Coal($/Ton)

Uranium($/lb)

oil($/Barrel)

NaturalGas($/MBTU rightaxis)

locationofthesolarresourceandcanvaryfromnovalueuptomorethan3centspergenerated

solarKWh(e.g.,seeShugar&Hoff,1993,Hoffetal.,1996,Wengeretal.,1996andHoff,1997).

Fuel pricemitigation, 35 /kWh: Solar energy production does not depend on commodities6whoseprices fluctuateonshort termscalesandwill likelyescalatesubstantiallyoverthe long

term.Whenconsideringfigure1,itishardtoimaginehowthecostofthefinitefuelsunderlying

thecurrent

wholesale

electrical

generation

will

not

be

pressured

up

exponentially

as

the

available pool of

resources contracts and

thedemandfromthenew

economies of the world

accelerates.Thecostofoil

may be the most

apparent, but all finite

energy commodities,

including coal, uranium

andnatural

gas,

tend

to

followsuit,astheyareall

subjecttothesameglobal

energy demand

contingencies. Even

before the 2011 Middle

East political disruptions,

inastillsluggisheconomy,energycommoditypriceshadrampeduppasttheir2007levelswhen

theworldeconomywasstronger(seefig.3).Solarenergyproductionrepresentsaverylowrisk

investmentthatwillprobablypanoutwellbeyondastandard30yearbusinesscycle(Zweibel,

2010). InastudyconductedforAustinEnergy,Hoffetal.quantifiedthevalueofPVgeneration

asahedgeagainstfluctuatingnaturalgasprices(Hoffetal.,2006).Theyshowedthatthehedge

valueofalowriskgeneratorsuchasPVcanbeassessedfromtwokeyinputs:(1)thepriceofthe

displacedfiniteenergyoverthelifeofthePVsystemasreflectedbyfuturescontracts,and(2)a

riskfree discount rate7for each year of system operation. Focusing on the short term gas

futuresmarket(lessthan5years)ofrelevancetoautilitycompanysuchasAustinEnergy,and

takingastableoutlookongaspricesbeyondthishorizon,theyquantifiedthehedgedvalueof

PVat roughly50%of currentgeneration cost i.e.,35centsperkWh in thecontextof this

article,assumingthatwholesaleenergycost(seeabove)isrepresentativeofgenerationcost.

6Conventionalenergyiscurrentlyrequiredforthemanufactureofsolarsystemsbut,asarguedabove,thisinput

willeventuallybedisplacedbecauseoftheresourcesbreedereffect.7Discountratesareusedtomeasurethepresentdecisionmakingweightoffutureexpenses/revenuesasa

functionoftheirdistancetothepresent.Ahighdiscountrateminimizestheimpactoffutureeventssuchasfuel

costincreases,whilealowrategivesmoreweighttotheseevents(e.g.,seeRef15).Fromaninvestorsstand

point,thediscountraterepresentsthereturnofahypotheticalinvestmentagainstwhichtobenchmarka

particularventure.Lowriskinvestmentsarecharacterizedbylowreturnrates(e.g.,Tbills)whilehighriskventures

requirehighratestoattractprospectiveinvestors.

-

8/14/2019 EnergyPolicy SolarPowerintheUS Perez Zweibel Hoff

7/16

R.Perez,K.Zweibel,T.Hoff

Thereareadditionalbenefitsthataccruetothesocietyatlargeanditstaxpayers:

Grid securityenhancement,23 /kWh:because solargeneration canbe synergisticwithpeakdemandinmuchoftheUS,theinjectionofsolarenergynearpointofusecandelivereffective

capacity, and therefore reduce the risk of the power outages and rolling blackouts that are

causedby

high

demand

and

resulting

stresses

on

the

transmission

and

distribution

systems.

The

capacityvalueofPVaccruestotheratepayerasmentionedabove.However,whenthegridgoes

down, the resultinggoodsandbusiness lossesarenot theutilitys responsibility: societypays

theprice,via lossesofgoodsandbusiness,compounded impactson theeconomyand taxes,

insurancepremiums,etc. ThetotalcostofallpoweroutagesfromallcausestotheUSeconomy

hasbeenestimatedat$100billionperyear(Gellings&Yeager,2004).Makingtheconservative

assumptionthatasmallfractionoftheseoutages,say510%,aretheofthehighdemandstress

typethatcanbeeffectivelymitigatedbydispersedsolargenerationatacapacitypenetrationof

20%,itisstraightforwardtocalculatethatthevalueofeachkWhgeneratedbysuchadispersed

solarbasewouldbewortharound3centsperkWhtotheNewYorktaxpayer(seeappendix).

Environment/health,36/kWh: It iswellestablished that theenvironmental footprintofsolargeneration (PV and CSP) is considerably smaller than that of the fossil fuel technologies

generatingmostofourelectricity (e.g.,Fthenakisetal.,2008),displacingpollutionassociated

withdrilling/mining,andemissions.Utilitieshave toaccount for thisenvironmental impact to

some degree today, but this is still only largely a potential cost to them. Ratebased Solar

Renewable Energy Credits (SRECs) markets that exist in some states as a means to meet

RenewablePortfolioStandards(RPS)areapreliminaryembodimentofincludingexternalcosts,

but they are largely drivenmore by politicallynegotiated processes than by a reflection of

inherent physical realities. The intrinsic physical value of displacing pollution is very real

however: each solar kWh displaces an otherwise dirty kWh and commensurately mitigates

severalof

the

following

factors:

greenhouse

gases,

Sox/Nox

emissions,

mining

degradations,

groundwatercontamination,toxicreleasesandwastes,etc.,whichareallpresentorpostponed

coststosociety. Severalexhaustivestudiesemanatingfromsuchdiversesourcesasthenuclear

industry or the medical community (Devezeaux, 2000, Epstein, 2011) estimate the

environmental/health cost of 1 kWh generated by coal at 925 cents, while a [nonshale8]

naturalgaskWhhasanenvironmentalcostof36centsperkWh. GivenNewYorksgeneration

mix(15%coal,29%naturalgas),and ignoringtheenvironmentalcostsassociatedwithnuclear

andhydropower,theenvironmentalcostofaNewYorkkWh isthus2to6centsperkWh.Itis

importanttonotehoweverthattheNewYorkgriddoesnotoperateinavacuumbutoperates

withinand issustainedby a largergridwhosecoal footprint isconsiderably larger (more

than45%

coal

in

the

US)

with

acorresponding

cost

of

512

cents

per

kWh.

In

the

appendix,

we

showthatpricingonesinglefactorthegreenhousegasCO2deliversataminimum2cents

persolargeneratedPVkWhinNewYorkandthatanargumentcouldbemadetoclaimamuch

8Shalenaturalgasisbelievedtohaveahigherenvironmentalimpactthanconventionalnaturalgas,including

greenhousegasemissions(Howarth,R.,2011).

-

8/14/2019 EnergyPolicy SolarPowerintheUS Perez Zweibel Hoff

8/16

R.Perez,K.Zweibel,T.Hoff

higher number. Therefore taking a range of 36 cents per kWh to characterize the

environmentalvalueofeachPVgeneratedKWhiscertainlyaconservativerange.

LongTermSocietalValue,34/kWh:Beyondthecommodityfutures5yearfuelpricemitigationhedgehorizonof relevance to autility companyandworth35/kWh (see above),a similar

approachcanbeusedtoquantifyingthe longtermfinitefuelhedgevalueofsolargeneration,

fromasocietal

(i.e.,

taxpayers)

viewpoint

in

light

of

the

physical

realities

underscored

in

figure

1. Prudently,andmanywouldargueconservatively,assumingthatlongterm,finite,fuelbased

generation costswillescalate to150% in real termsby2036, the30year insurancehedgeof

solar generation gauged against a low risk yearly discount rate equal the Tbill yield curve

amounts to47 centsperkWh (seeappendix).Further,arguing theuseofa lower societal

discountrate(Toletal.,2006)wouldplacethehedgevalueofsolargenerationat712centsper

kWh(seeappendix).Takingamiddlegroundof69centsperkWh,thelongtermsocietalvalue

ofsolargenerationcanthusbeestimatedat34centsperkWh(i.e.,thedifferencebetweenthe

societalhedgeandshorttermutilityhedgealreadycountedabove).

Economic growth, 3+ /kWh: The German andOntario experiences,where fast PV growth isoccurring,showthatsolarenergysustainsmorejobsperkWhthanconventionalenergy(Louw

etal.,2010,BanWeissetal.,2010,andseeappendix).Jobcreation impliesvaluetosociety in

many ways, including increased tax revenues, reduced unemployment, and an increase in

general confidence conducive to business development. Counting only tax revenue

enhancementprovidesatangiblelowestimateofsolarenergysmultifacetedeconomicgrowth

value. In New York this low estimate amounts to nearly 3 cents per kWh, even under the

extremelyconservative,but thus far realistic,assumption that80%of themanufacturingjobs

would be either outofstate or foreign (see appendix). The total economic growth value

induced by solar deployment is not quantified as part of this article as itwould depend on

economicmodelchoicesandassumptionsbeyondthepresentscope.Itisevidenthowever,that

the total value would be higher than the tax revenues enhancement component presently

quantified.

Cost: It is important to recognize that there is also a cost associatedwith the deployment of solar

generationon the power gridwhich accrues against theutility/ratepayers. This cost represents the

infrastructuralandoperationalexpensethatwillbenecessarytomanagethe flowofnoncontrollable

solarenergygenerationwhilecontinuingtoreliablymeetdemand.ArecentstudybyPerezetal.(2010)

showedthatinmuchoftheUS,thiscostisnegligibleatlowpenetrationandremainsmanageable fora

solarcapacitypenetrationof30%(lessthan5centsperKWhinthegreaterNewYorkareaatthathigh

penetration level). Up to this levelofpenetration, the infrastructuralandoperationalexpensewould

consistof

localized

(demand

side)

load

management,

storage

and/or

backup

operations.

At

higher

penetration, localizedmeasureswouldquicklybecome tooexpensiveand the infrastructureexpense

would consist of long distance continental interconnection of solar resources, such as considered in

projectssuchasDesertec(Talaletal.,2009).

-

8/14/2019 EnergyPolicy SolarPowerintheUS Perez Zweibel Hoff

9/16

R.Perez,K.Zweibel,T.Hoff

BottomlineTable1summarizesthecostsandvaluesaccruingto/againstthesolardeveloper,theutility/ratepayer

andthe

society

at

large

represented

by

its

tax

payers.

The

combined

value

of

distributed

solar

generationtoNewYorksrateandtaxpayers isestimatedtobe intherangeof1541centsperkWh.

TheupperboundoftherangeappliestosolarsystemslocatedintheNewYorkmetro/LongIslandarea

andthelowerboundappliestoveryhighsolarpenetrationforsystemsinnonsummerpeakingareasof

upstateNewYork.Ineffect,Table1showsthatgridparityalreadyexistsinpartsofNewYork andby

extensioninotherpartsofthecountry sincethevaluedeliveredbysolargenerationexceedsitscosts.

Thisobservationjustifiestheexistenceof(orrequestsfor)incentivesasameanstotransfervaluefrom

thosewhobenefittothosewhoinvest.TABLE1

Conservativeestimate:Itisimportanttostressthatthisresultwasarrivedatwhiletakingaconservative

floorestimate forthedeterminationofmostbenefits,andthatasolidcasecouldbemade forhigher

numbersparticularlyintermsofenvironment,fuelhedgeandbusinessdevelopmentvalue. Inaddition,

several other likely benefits were not accounted for because deemed either too indirect or too

controversial. Someoftheseunaccountedvalueaddersareworthabriefqualitativemention:

Developer/Investor

Distributed solar*systemCost 2030 /kWh

TransmissionEnergyValue 6 to11/kWh

TransmissionCapacityValue 0 to5/kWh

DistributionEnergyValue 0 to1/kWh

DistributionCapacityValue 0 to3/kWh

FuelPriceMitigation 3 to5/kWh

SolarPenetrationCost 0 to5/kWh

GridSecurity

Enhancement

Value 2

to

3/kWh

Environment/healthValue 3 to6/kWh

LongtermSocietalValue 3 to4/kWh

EconomicGrowthValue

TOTALCOST/VALUE 2030 /kWh

*Centralizedsolarhasachievdacostof1520centsperkWhtoday.Howeverlessoftheabovevalueitemswould apply.The

distributionvalueitemswouldnotapply.Transmission capacity,andgridsecurityitemswouldgenerallybetowardsthebottomof

theaboveranges,whilepenetration costwouldbetowardsthetopoftherangesbecauseoftheburdenplacedontransmission

andthepossibleneedfornewtransmissionlines nevertheless,avalueof1430centsperkWhcouldbeclaimed.

Utility/Ratepayer Society/Taxpayer

15to41/kWh

3+/kWh

-

8/14/2019 EnergyPolicy SolarPowerintheUS Perez Zweibel Hoff

10/16

R.Perez,K.Zweibel,T.Hoff

No value was claimed beyond 30 year life cycle operation for solar systems, although thelikelihoodofmuchlongerquasifreeoperationishigh(Zweibel,2010)

Thepositive impacton internationaltensionsand the reductionofmilitaryexpense tosecureever more limited sources of energy and increasing environmental disruptions was not

quantified.

The factdispersedsolargenerationcreates thebasis forastrategicallymore securegridthanthecurrenthubandspokepowergrid inanageofgrowingterrorismandglobaldisruptions

concernswasnotquantified.

Economicgrowthimpactwasnotquantifiedbeyondtaxrevenueenhancement. The question of government subsidies awarded to current finite energy sources (i.e.,

displaceabletaxpayersexpense)wasnotaddressed.

Taxpayervs.ratepayer:Unlikeconventionalelectricitygeneration,thevalueofsolarenergyaccruesto

twoparties.Thismayexplainwhytheperceptionofvalueisnotasevidentastheabovenumberswould

suggest. In particular, public utility commissions are focused on defending the interests of utility

ratepayers,and

ifonly

the

utility/ratepayers

value

is

considered,

the

case

for

solar

is

marginal

at

best

(425centsofvalueperkWh).However,focusingontheratepayersinterestaloneignoresthefactthat

ratepayersandthetaxpayersareoneandthesame.Supportingonetotheexclusionoftheotherends

uppenalizingthewholeperson.

TangibleValue:Anotherreasonwhyperceptionofvalueisnotevidentisbecausethosewhopayforthe

coststhatsolarwoulddisplaceareoftennotawareofthesecosts.Fortheratepayers items(energy&

capacity),thetradeoff isobvious,butnotsofortheother items.However,costsare incurred inmany

indirect,diffuse,butneverthelessveryreal ways e.g., insurancepremiums,highertaxestomitigate

impacts, deferred costs (environment, future replacements of short term infrastructures, energy

increases),and

missed

economic

growth

opportunities.

Stablevalue:Oneof the characteristicsof thesolar resource is itsubiquityand stability: it ispresent

everywhereanddoesnotvarymuchfromoneyeartothenextalthoughshorttermvariability(clouds,

weather,seasons)oftentendtoovershadowthisperception (Hoff&Perez,2011).Similarly,thevalue

deliveredbysolargeneratorsisverystableandpredictable.

The two primary factors that do determine value per kWh produced are (1) location and (2) solar

penetration9. Location is important because the value delivered by solar generation in terms of

transmissionanddistributionenergyandcapacity,aswellasblackoutprotectionislocationdependent:

a system inwinterpeaking ruralupstateNewYorkwilldeliver lessvalue thana system inagrowing

commercialsector

of

Long

island.

Penetration

is

important,

because

some

of

the

benefits,

in

particular

the capacity benefits, tend to erodewith penetration; and the cost to locallymitigate this erosion

increases(see,Perezetal.,2010).

9Technologyandsolarsystemspecs(e.g.,arraygeometry)arealsorelevant:highestvalueinNYCwouldbefor

systemsdeliveringnearmaximumoutput at4PMi.e.,fixedtilt,orientedSW.

-

8/14/2019 EnergyPolicy SolarPowerintheUS Perez Zweibel Hoff

11/16

R.Perez,K.Zweibel,T.Hoff

Therefore, ifonewere todesignaneffectivesystem toprovidesolargenerationwiththe fairvalue it

deservesfromrate/taxpayers,itwouldhavetobeastableandpredictablesystemthataccountsforthe

locationandpenetrationfactors. AuctionbasedSRECScouldbeengineeredtomeetthesecriteria,but

asmartvaluebasedFITthatisstableandtunablebydesign,appearstobeamorelogicalmatch10.

Veryhighpenetrationsolar?Someof thebenefits identified in thisarticleapply roughlyup to30% solarpenetration.Thisalready

representsa375GWhighvalue solardeploymentopportunity for theUS avery largeprospective

marketwithalargenationalpayoff;butwhathappensbeyondthatpoint?Atveryhighpenetration,the

issues facing solarwouldbecome similar towindgenerations issues,albeitwithamuch smallerand

more [aesthetically] acceptable footprint.Many of the value itemsmentioned abovewould remain

(longterm,wholesale energy, fuel price hedge, environment)while otherswould not (regional and

localized capacity). The solutions envisaged today, including large scale storage and

continental/international interconnectionstomitigate/eliminateweather,seasonsanddailyvariability,

arecurrently

on

the

drawing

board

(e.g.,

Perez,

2011,

Lorec,

2010,

Talal

et

al.,

2009).

FinalWord:TheValueofSolarIt is clear that somepossibly largevalueof solarenergy ismissedby traditionalanalysis.Mostofus

recognize this in our perception of solar as more sustainable than traditional energy sources. The

purposeofthisarticle istobeginthequantificationofthisvaluesothatwecanbettercometoterms

with the difficult investments we may make in solar despite its apparent grid parity gap with

conventionalenergy.Societygainsbacktheextrawepayforsolar.Itgains itback inahealthier,more

sustainableworld,economically,environmentally,andintermsofenergysecurity.

AcknowledgementsManythankstoMarcPerez,forconstructivereviewsandforcontributingbackgroundreferences. Many

thanks to Thomas Thompson and Gay Canough for their feedback, and pushing us to produce this

document.

Reference1. BanWeissG.etal.,SolarEnergyJobCreationinCalifornia,UniversityofCaliforniaatBerkeley2. Chianese, D, A. Realini, N. Cereghetti, S. Rezzonico, E. Bura, G. Friesen, (2003), Analysis of

WeatheredcSiModules,LEEETISO,UniversityofAppliedSciencesofSouthernSwitzerland,Manno.

3. Devezeaux J.G., (2000): Environmental Impacts of ElectricityGeneration. 25thUranium InstituteAnnualSymposium.London,UK(September,2000).

10ItisimportanttostatethatwearetalkinghereaboutavaluebasedFIT,wheretheFITistheinstrumentto

transfervaluefromthosewhobenefittothosewhoinvest.ThisisunlikeFITimplementationsinotherpartsofthe

world,notablyinSpain,whereFITswereprimarilydesignedtoprovideaboosttosolarbusinessdevelopment.

-

8/14/2019 EnergyPolicy SolarPowerintheUS Perez Zweibel Hoff

12/16

R.Perez,K.Zweibel,T.Hoff

4. Epstein,P.(2011):Fullcostaccountingforthelifecycleofcoal.AnnalsoftheNewYorkAcademyofSciences.February,2011.

5. Fthenakis,V.,Kim,H.C.,Alsema,E.,EmissionsfromPhotovoltaicLifeCycles.EnvironmentalScienceandTechnology,2008.42(6):p.21682174

6. Gellings,C.W.,andK.Yeager,(2004):Transformingtheelectric infrastructure.PhysicsToday,Dec.2004.

7. Hoff,T.,H.Wenger,andB.Farmer(1996):DistributedGeneration:AnAlternativetoElectricUtilityInvestmentsinSystemCapacity.EnergyPolicyVolume24,Issue2,pp.137147.

8. Hoff, T. (1997): Identifying Distributed Generation and Demand Side Management InvestmentOpportunities.TheEnergyJournal17(4):89105.Hoff,T.E.(1997).

9. HoffT.,R.Perez,G.Braun,M.Kuhn,andB.Norris,(2006):TheValueofDistributedPhotovoltaicstoAustinEnergyandtheCityofAustin.FinalReporttoAustinEnergy(SL04300013)

10.Howarth,R., (2011):PreliminaryAssessmentof theGreenhouseGas Emissions fromNaturalGasObtainedbyHydraulicFracturing.CornellUniversity,Dept.ofEcologyandEvolutionaryBiology.

11. IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, (2007): Summary for Policymakers. ClimateChange

2007

Mitigation

of

Climate

Change,

IPCC

26th

Session.

12.Letendre S. and R. Perez, (2006): Understanding the Benefits of Dispersed GridConnectedPhotovoltaics: From Avoiding theNextMajorOutage to TamingWholesale PowerMarkets. The

ElectricityJournal,19,6,6472

13.Lorec,P.,UnionfortheMediterranean:TowardsaMediterraneanSolarPlan.RpubliqueFranaise MinistredeL'Ecologiedel'Energie,duDveloppementDurableetdelaMer,2010

14.Louw, B., J.E.Worren and T.Wohlgemut, (2010): Economic Impacts of Solar Energy inOntario.CLearSkyAdvisorsReport(www.clearskyadvisors.com)

15.E.g.,Nordhaus,,William(2008)."AQuestionofBalance WeighingtheOptionsonGlobalWarmingPolicies".YaleUniversityPress.

16.Perez,M,(2011):FacilitatingWidespreadSolarResourceutilization:GlobalSolutionsforovercomingtheintermittencyBarrier(akaContinentalScaleSolar).ColumbiaUniversityPhDProposal

17.Perez,R.,R.Seals,H.Wenger,T.HoffandC.Herig, (1997):PVasaLongTermSolution toPowerOutages. Case Study: The Great 1996 WSCC Power Outage. Proc. ASES Annual Conference,

Washington,DC,

18.PerezR.,B.Collins,R.Margolis,T.Hoff,C.HerigJ.WilliamsandS.Letendre,(2005)SolutiontotheSummer Blackouts How dispersed solar power generating systems can help prevent the next

majoroutage.SolarToday19,4,July/August2005Issue,pp.3235

19.PerezR. andT.Hoff, (2008):Energy andCapacityValuationofPhotovoltaicPowerGeneration inNewYork.PublishedbytheNewYorkSolarEnergyIndustryAssociationandtheSolarAlliance

20.Perez,R.andM.Perez,(2009a):Afundamentallookatenergyreservesfortheplanet.TheIEASHCSolarUpdate,Volume50,pp.23,April2009

21.PerezR.,M.Taylor,T.HoffandJ.PRoss,(2009b):RedefiningPVCapacity.PublicUtilitiesFortnightly,February2009,pp.4450

22.Perez,R.,T.HoffandM.Perez,(2010):QuantifyingtheCostofHighPVPenetration.Proc.ofASESNationalConference,Phoenix,AZ

-

8/14/2019 EnergyPolicy SolarPowerintheUS Perez Zweibel Hoff

13/16

R.Perez,K.Zweibel,T.Hoff

23.Perez R. & T. Hoff (2011): solar resource variability, myths and facts, Solar Today (upcoming,Summer2011)

24.Peters,N.,(2010):PromotingSolarJobsAPolicyFrameworkforCreatingSolarJobsinNewjersey25.Shugar,D., andT.Hoff (1993):Gridsupportphotovoltaics:Evaluationof criteria andmethods to

assess empirically the local and system benefits to electric utilities. Progress in Photovoltaics:

Researchand

Applications,

Volume

1,

Issue

3,

pp.

233250.

26.Talal,H.B.,etal., (2009)CleanPowerfromDeserts:TheDESERTECConcept forEnergy,WaterandClimate Security,G. Knies, Editor. TanakaN., (2010): The Clean Energy Contribution,G20 Seoul

Summit:SharedGrowthBeyondCrisis.

27.TolR.S.J.,J.Guo,C.J.Hepburn,andD.Anthoff(2006):DiscountingandtheSocialCostofCarbon:aCloserLookatUncertainty,EnvironmentalScience&Policy,9,205216,207

28.Wenger,H.,T.Hoff,and J.Pepper (1996):PhotovoltaicEconomicsandMarkets:TheSacramentoMunicipalUtilityDistrictasaCaseStudy.Report. www.cleanpower.com

29.Zweibel,K,2010,ShouldsolarPVbedeployedsoonerbecauseoflongoperatinglifeatpredictable,lowcost?Energypolicy,38,75197530.

APPENDIXGridsecurityenhancement: 20%USpenetrationwouldrepresentroughly250GWofsolargeneratingcapacity.UsingaNewYorkrepresentativeproduction levelof1,350kWhperKWperyear, the solar

productionwouldthusamountto375billionkWh/year,worth$510billionsinoutagepreventionvalue

underthe

conservative

assumption

selected

here,

amounting

to

23cents

per

kWh.

EstimatingsolarCO2mitigationvalue:ThevalueofsolargenerationtowardsCO2displacementmaybegaugedusingseveraldifferentapproaches.

(1) Bystartingfromthecarbontax/capandtradepenalty levelsthatarebeingenvisagedtoday at$3040/tonofCO2(e.g.,Nordhaus,2008). GiventheenergygenerationmixinastatelikeNewYork,

each locallydisplacedkWh (i.e., solargenerated)would remove500600gramsofCO2,and thus

wouldbeworthnearly2cents.

(2) Bystarting from the figureof1.5%ofworldGDPperyearadvancedby the IPCCastheminimumnecessarytopreventarunawayclimatechange(IPCC,2007).1.5%ofGDPrepresents$900billions.

GlobalCO2emissionsare~30billionstons.Displacing2/3rdsoftheseemissionstobringusbacktoa

1960s level, and again, and takingNew Yorks current generationmix as an emission reference

amountstoavalueof3centsforeachkWhdisplacedbysolargeneration.

(3) Alsobystarting from the1.5%GDP figure,but recognizing thatsolutions todisplacegreenhousegasesneed tobeprimedandencouragedbefore theycanbeeffectiveand reach theirmitigation

objectives. Ifweassume,veryconservatively, that solarenergy representsonly10%of theglobal

-

8/14/2019 EnergyPolicy SolarPowerintheUS Perez Zweibel Hoff

14/16

R.Perez,K.Zweibel,T.Hoff

warmingsolution11andshouldthusbefullyencouragedtothetuneof0.15%GDP,thengiventhe

current installed solarcapacityof2030GWand thecurrent installation rateapproaching20GW

annuallyworldwide, encouraging the development of solarwould amount to distributing ~ 150

centsperkWhtoeachexistingandnewsolarsystem.Thisvaluewouldthendecreasegraduallyover

the years as the installed solar capacity grows, ultimately reaching a value commensuratewith

points(1)

and

(2).

Longtermfossilfuelpricemitigation/societalvalue:ThelongtermfuelpricemitigationvalueofasolarkWh isthepresentvalueofthedifferencebetweenwhatonewouldhavetopayforenergyescalating

over the lifeof the solar systemandwhatonewouldhave topay ifenergycost remained constant.

Undertheassumptionsofthisarticle150% increaseoffiniteenergy in25yearsandapresentvalue

assessedusingayearlylowriskdiscountrateequaltotheTBillyieldcurve,thisdifferenceisabout60%.

Hence,takingthesolarcoincidentwholesalegenerationcostof611centsasgaugeofcurrentenergy

productioncost,thelongtermmitigationvalueofasolarkWhis4to7centsperkWh.Interestingly,this

estimateiscommensuratewiththeInternationalEnergyAgencyscontentionthataCO2taxworth$175

perton

should

be

necessary

to

encourage

the

development

of

renewables

and

displace

fossil

fuel

depletion (Tanaka,2010)whilemitigating theirdepletionandkeeping their long termpricesnear the

presentrange. BasedontheNewYorksgenerationmix,$175pertonamountsto910centsperkWh.

It is important to remark that alternative and less conservative approaches can be considered and

defended to determine the value of the low risk/long life solar investment to society. In particular,

comparingthedifferencebetweensolarsavingsassessedwithabusinessasusualdiscountrateanda

societal discount rate provides ameasure of the long term societys benefit that is not taken into

account using shortterm oriented business as usual approaches. Evenwhen using a verymodest

businessasusualdiscountrateof7%,thepresentvalueofconventionalgenerationappearsreasonable:

futureoperatingcostsincreasebutdonotmattermuchbecausetheyarediscountedat7%theweight

ofexpense/revenue

30

years

into

the

future

in

terms

of

present

decision

making

is

discounted

by

nearly

85%(at10%discountrate,theweightwouldbediscountedbyover95%).However,thispracticeheavily

penalizes future generations. It also penalizes solar: Solar power plants are upfrontloaded with

relativelyhigh installationcosts,and thequasi freeenergy theywillproduce for the long term isnot

valued as it should, since it is heavily discounted. Nevertheless, the intergenerational, longterm

societalvalueofpresentday solar installation isvery real.Asa remedy to thisdichotomy, societal

discount rates are sometimes used by governments to justify investments which are deemed

appropriate forthe longtermwellbeingofthesociety (Toletal.,2006)solargenerationclearlyfits

thisdefinition.Comparinga2%societaldiscount rateanda7%businessasusual rateandcalculating

thevalueof solaras thepresentdifferenceof the twoalternatives, the societalhedgevalueof solar

energygeneration

would

be

712

cents

per

kWh.

Taxrevenueenhancement:TheGermanexperienceindicatesthateachMWofPVinstalledimplies1015modulemanufacturingjobs,815installationjobsand0.3maintenancejobs,asconfirmedbyrecent

numbers fromOntario (Louw et al., 2010, Peters, 2010). Solarjobs representmore than ten times

11GiventhepotentialsshowninFigure1,itisprobablymuchhigherthanthat.Ahigherpercentagewouldyielda

highersolarvalue.

-

8/14/2019 EnergyPolicy SolarPowerintheUS Perez Zweibel Hoff

15/16

R.Perez,K.Zweibel,T.Hoff

conventionalenergyjobsperunitofenergyproducedi.e.,tennewsolarjobswouldonlydisplaceone

conventionalenergyjob.

Althoughthesenumbersmaybeskewedbythefactthatastillexpensiveandnascentsolar industry is

overlyjobintensive,aquickrealitycheckrevealsthattherelativehigherpriceofthesolartechnology

todayalso

implies

ahigher

job

density:

the

necessary

20

30

c/kWh

solar

revenue

stream

underlying

discussions inthisarticlecorrespondstoaturnkeycostof$4millionpersolarMW. InthecaseofPV,

this cost can be assumed to divide evenly between technology (modules/inverters) and system

installation(construction,structures)representing$2MperMWforeach.Conservativelyassumingthat

50%oftechnologyand75%ofinstallationcostsaredirectlytraceabletosolarrelatedjobsandassuming

a job+overhead rate of $100K/year, this simple reality check yields 10 manufacturing and 15

constructionrelatedjobs.Demonstratingthatthesolarjobdensityofthesolarresource ishigherthan

that of conventional energy is also straightforward to ascertain from first principles: comparing a

$4/Watt turnkey solar system producing 1,500 kWh/KW/year to a $1/Watt turnkey CCGT producing

5,000kWh/kW/year,andassuming that thejobdensityper turnkeydollar is the same inbothcases,

yields13

times

more

jobs

for

the

solar

option

per

kWh

generated.

Astheturnkeycostofsolarsystemsexpectedlygoesdown,thejobdensitywillofcoursebereduced,

but,moreimportantly,sowillthenecessarybreakevenrevenuestream.

Fornow,giventhepremiseofthispaper arequiredsolarenergyrevenuestreamof2030centsper

solarkWh letuscalculatethevaluethatsocietyreceivesunderthisassumption.

Thefollowingassumptionsareusedforthiscalculation:

EachnewsolarMWresultsin17newjobs.Thereare2newmanufacturingjobs(it isassumedthat

80%

of

the

manufacturing

jobs

are

foreign

and

do

not

generate

any

federal

or

state

tax

revenue)andthereare15newinstallationjobs.

Solarsystemsarereplacedafter30years,sotheamountofjobscorrespondingtoeachinstalledMW isthepresentvalueofa30yearjobreplacementstream.Withadiscountrateof7%,17

jobstimesanannualizedfactorof0.08translatesto1.36jobsperMWperyear.

Systemmaintenancerelatedjobsamountto0.3jobsperMW12(Germanexperience) ThetotalamountofsustainedjobsperMWisthereforeequalto1.66. Assumingthattensolarjobsdisplaceoneconventionalenergyjob,thenetsustainablenewjobs

persolarMWarethereforeequalto1.49(90%of1.66).

Thesalaryforeachsolarjobis$70K/year. Current federal and New York tax rates for an employee making $70,000 per year pays a

combinedeffectiveincometaxrateof23%.

1MWofPVgenerates1,500,000kWhperyear.

12ThiscorrespondstoaveryreasonableO&Mrateof0.5%undertheassumptionsofthisstudy.

-

8/14/2019 EnergyPolicy SolarPowerintheUS Perez Zweibel Hoff

16/16

R.Perez,K.Zweibel,T.Hoff

Finally, direct job creation translates to the additional creation of indirect jobs. It isconservativelyassumedthattheindirectmultiplierequals1.7(i.e.everysolarjobhasanindirect

effectintheeconomyofcreatinganadditional0.7jobs).13

Puttingthepiecestogether,thetaxbenefitfromjobcreationequalsabout3centsperkWh.

13Indirectbasemultipliersareusedtoestimatethelocaljobsnotrelatedtotheconsideredjobsource(heresolar

energy)butcreatedindirectlybythenewrevenuesemanatingfromthenew[solar]jobs.