Emotion Embodiment and Mirror Neurons In

-

Upload

jason-reyes -

Category

Documents

-

view

221 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Emotion Embodiment and Mirror Neurons In

Emotion, Embodiment, and Mirror Neurons in Dance/Movement Therapy: A Connection Across Disciplines

Allison F. Winters

Published online: 21 October 2008

� American Dance Therapy Association 2008

Abstract The current study questions whether our emotions change depending on

whether we watch a person model postures or, rather, embody the postures our-

selves. The posture photographs from the Diagnostic Analysis of Nonverbal

Accuracy Test of Posture (DANVA2-POS) were used as the stimuli by which to rate

levels of agreement among participants. Forty-one individuals were randomly

allocated to one of two groups (observing or embodying) and invited to rate, in

open-ended written responses, twenty-four postures by describing the emotion or

feeling associated with each posture. The responses were then coded as happy, sad,

angry, fearful, shameful, or surprised. A comparison of means demonstrated that

there were no differences in response among all emotions except anger. A signifi-

cantly higher anger response was shown for the embodying condition than for the

observing condition.

Keywords Embodiment � Emotions � Mirror neurons � Posture �Dance/movement therapy

Introduction

To what extent do people agree on which emotions are associated with specific body

postures? The literature suggests that people agree at above chance levels (Coulson,

2004; De Silva & Bianchi-Berthouze, 2004; Ekman, 1965; Ekman & Friesen, 1967;

Pitterman & Nowicki, 2004; Schouwstra & Hoogstraten, 1995; Wallbott, 1998),

based on studies that asked participants to judge images of various body postures.

Problems arise, however, when looking at body postures and emotions, depending

on how the postural stimulus is administered (photograph vs. live model vs.

A. F. Winters (&)

1166 Pelham Pkwy South, Bronx, NY 10461, USA

e-mail: [email protected]

123

Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105

DOI 10.1007/s10465-008-9054-y

embodiment). The purpose of this study is to take a closer look at the issue. Is there

a difference in recognition accuracy when one embodies a posture as compared to

simply observing another? The current study questions whether emotions that we

associate with body postures change depending on whether we watch a person

model postures or if we embody the postures ourselves. Recent research on mirror

neurons suggests that there is no difference; observing engages the same

neurological processes as embodying does (Gallese, 2005; Iacoboni, 2008;

Rizzolatti, Fogassi, & Gallese, 2001). This study is particularly intended to enrich

the body of literature in the field of dance/movement therapy, as well as to help

bridge the gap between body-oriented psychotherapeutic work and other mental

health professions.

The History of Posture and Emotion

Posture has been found to be a particularly powerful tool in both expressing and

recognizing emotion (Bianchi-Berthouze, Cairns, Cox, Jennett, & Kim, 2006).

Studies on posture and emotion have provided insight into a plethora of issues, such

as motivation, intent, therapeutic interactions, relationships, and mental disorders.

In the literature on emotion, the focus on body posture can be credited to William

James (1932) for his study of reactions to photographs of people in various postures.

Since then, body posture has been studied to gain insight into the emotions that are

supposedly connected with them. Some studies have looked at specific differences

in recognition of emotion in posture, such as cultural diversity (Kleinsmith, De

Silva, & Bianchi-Berthouze, 2005, 2006; Kudoh & Matsumoto, 1985; Russell,

1994), age (Boone & Cunningham, 1996, 1998; Montepare, Koff, Zaitchik, &

Albert, 1999; Petti, Voelker, Shore, & Hayman-Abello, 2003), and successful social

interactions (Bickmore, 2004; Sternglanz & DePaulo, 2004).

Other studies have even looked to computer technology for its usefulness in

measuring people’s judgments of body postures (Bente, Kramer, Petersen, & De

Ruiter, 2001; De Silva & Bianchi-Berthouze, 2004). This work has created an

important base of knowledge regarding emotion and posture. Yet, questions still

remain. Specifically, how accurate are people in judging body postures and

emotion? What emotions are equated with which body postures? Although there has

been extensive discussion about the importance of people’s accuracy in recognizing

emotion in body posture, few studies have been conducted to explore this area of

interest.

Basic Emotions and the Question of Methodology

Since Darwin (1872), researchers have studied how people express emotion through

various nonverbal channels, such as facial expression, voice, and body posture.

Interest in people’s perceptions of emotion was especially heightened as a result of

Ekman’s original body of work (Ekman, 1970, 1972, 1973; Ekman & Friesen, 1971;

Ekman, Sorenson, & Friesen, 1969), which measured attributions of emotions to

facial expressions cross-culturally. It was found that across cultures, people tend to

Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105 85

123

ascribe particular emotions to specific facial expressions at above chance levels.

This study gave rise to the concept of basic emotions, which has since been used as

a standard by which to test people’s perceptions of nonverbal behavior. As a result,

the literature on body posture and emotion is largely focused on these basic

emotions.

Methodologically, the best way to test accuracy in recognizing emotions

associated with particular body postures is unclear. Part of the problem is that

researchers do not agree about which emotions are associated with which body

postures. Underlying the disagreement is the question of what the basic emotions

are and whether they are universal (Ekman, 1992, 1994; Izard, 1994; Ortony &

Turner, 1990, 1992; Panksepp, 1992; Russell, 1994). Researchers have used basic

emotions as a standard to test people’s recognition of various nonverbal cues.

Unfortunately, the standard seems to vary from study to study. Both the number of

basic emotions and the terms used to describe them seem to differ, depending on the

author. Ekman (1972) suggested six original basic emotions: happiness, anger, fear,

sadness, surprise, and disgust. Studies on body posture and emotion have used

anywhere from four to seven basic emotions, including emotions in addition to the

original six, such as shame, pride, and confusion (see Coulson, 2004; De Silva &

Bianchi-Berthouze, 2004; Keltner & Shiota, 2003; Pitterman & Nowicki, 2004;

Schouwstra & Hoogstraten, 1995; Wallbott, 1998). This causes difficulties in

comparing results across studies.

There has been some debate in the literature about the reliability of posed versus

spontaneous postures (Russell, 1994; Wallbott, 1998; Wallbott & Scherer, 1986), as

well as whether still photographs represent emotions as accurately as video (Ekman

& Friesen, 1967; Wallbott & Scherer, 1998). In the same vein, there has been some

disagreement about the use of actors to portray emotion as opposed to behavioral

observation, citing the actors’ representation as possibly being too simulated or

stereotyped (Wallbott, 1998; Wallbott & Scherer, 1986). The participant’s

viewpoint on the particular body posture has also been of some concern. Not

surprisingly, perspective can play an important role in determining how a person

recognizes a particular emotion from posture. There is some evidence to suggest

that some postures do not elicit the same response when viewed from different

angles (Coulson, 2004; Daems & Verfaillie, 1999). To complicate the issue further,

as Darwin (1872) postulated, the complex emotions (e.g., jealousy, greed, revenge,

guilt) are usually too difficult to detect in others (Chodorow, 1995). Introduction of

the so-called ‘‘background emotions,’’ including states such as calm and well-being

(Damasio, 1999), has added yet another level of emotional information to consider.

The body can also play a part in identifying emotions in others (Duclos et al.,

1989). In some situations, emotion can be detected by subtle details of body posture,

musculoskeletal changes, shaping of body movement, speed and contour of

movement, minimal changes in the amount and speed of eye movements, and the

degree and contraction of facial muscles (Damasio, 1999). In fact, some research

(Meeren, van Heijnsbergen, & de Gelder, 2005) suggests that recognition of

emotion in another is biased toward bodily expression, overriding what a face alone

might be expressing. Still other research has focused on how taking on or

86 Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105

123

embodying a posture can affect recognition accuracy (Barsalou, Niedenthal, Barbey,

& Ruppert, 2003).

Study Background

Winters (2005) attempted to answer some of these questions to bridge gaps in the

literature. The purpose of her study was to examine whether the format of the

question elicits different responses to images of body postures. To do this, the

Diagnostic Analysis of Nonverbal Accuracy Test of Posture (DANVA2-POS) was

used as a stimulus to measure judgment accuracy. The original test asks participants

to categorize 24 photographs of people in various postures by choosing among four

options: happy, sad, angry, and fearful. The study contrasted this forced-choice

methodology with the option to select ‘‘none of the above’’ and an open-ended

format (Winters, 2005). Rates of agreement were determined by comparing

participant responses to the DANVA2-POS between the three different conditions

(forced choice vs. ‘‘none of the above’’ vs. open-ended). Results suggested that

ratings of postures differ significantly under the three different conditions.

Participants whose options included ‘‘none of the above’’ were reliably less likely

to agree with the standard than those without a ‘‘none of the above’’ option.

Participants whose response options were open-ended disagreed with the standard at

even higher rates and tended to generate standard emotion words (or derivations or

synonyms of those words) far less often.

The differences in agreement may most likely be attributed to the lack of

consistency across studies aiming to measure agreement levels on posture and

emotion. Differences in choice of stimulus (photographs vs. computer-generated

figures), viewpoint differences, and forced-choice vs. open-ended response formats

could all affect agreement levels. The drop in agreement across the three conditions

implies that the emotions that participants associate with body postures are not so

clearly defined. It could also suggest that laboratory settings are not so conducive to

eliciting authentic emotional responses. Based on these findings, there appears to be

a much deeper level of processing occurring. Participants not only associate

postures with other ‘‘incorrect’’ emotions, but with non-emotions as well. It might

be helpful (and insightful) to consider emotions as Haidt and Keltner (1999) did, as

falling along a gradient of recognition. The basic emotions are basic because there is

evidence of them from infancy, yet they appear to exist on a ‘‘continuum of

intensity, from mild to extreme’’ (Chodorow, 1995, p. 100). It may not be practical

to measure people’s perceptions of body postures by restricting their responses to a

list of specified emotions.

The open-ended option generated a wide range of responses. Although the

instructions specified that participants were to write the emotion or feeling they

associated with each posture in the photographs, some responses consisted of non-

emotion words and phrases. In viewing these issues from a dance/movement therapy

perspective, rather than a cognitive psychology perspective, it became clear that

incorporating the body into this study was an important next step in this research.

Would the use of a different stimulus change the results? Would having people

Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105 87

123

observe an actual person embody these very same postures change the agreement

level? What if participants embodied the postures themselves? Would that change

the percentage of standard emotion responses in people’s responses?

The Body and Emotions

Since the early work on posture and emotion (James, 1932), little has been done to

further research on this topic. Much of the work has been focused on the

relationship between facial expressions and emotion. There does, however, seem to

be some agreement in the literature that the body plays a part in emotional

experience (Duclos et al., 1989). In fact, some research (Meeren, Van Heijnsbergen,

& de Gelder, 2005) suggests that recognition of emotion is hampered if facial

expression and body language are in disagreement; people actually tend to be biased

toward the emotion expressed by the body over what the face is expressing.

Furthermore, we process this difference on an unconscious level, which suggests

that we automatically read nonverbal cues and innately know when emotional

expression is ‘‘off.’’ Reading emotion in others appears to be a necessary function in

our sensory perception. Other research has focused on how taking on or embodying

a posture can affect one’s mood (Riskind, 1984; Riskind & Gotay, 1982).

In the dance/movement therapy literature, empirical research that looks at the

relationship between body, emotion, and perception is sparse. Chodorow (1995)

discusses fundamental (basic, primary) emotions and their connection to the body

and the psyche. She states, ‘‘emotions motivate and shape the way we move. An

emotion is at once somatic and psychic… In the depths of the unconscious, it is the

emotions that mediate between the realms of body and psyche, instinct, and spirit’’

(p. 98). Dance/movement therapy is rooted in the assumption that body and emotion

are intertwined. Dance/movement therapists speak of the powers of dance/

movement therapy and of how individuals have transformed before their eyes,

using their bodies to move through pain and gain insight into their deepest levels of

unconscious processing. These observations are often difficult to explain beyond a

feeling and, thus far, have been little explored in empirical research.

Training in dance/movement therapy requires the development of fine-tuned

observational skills. Dance/movement therapists are trained to ‘‘pick up’’ on

nonverbal cues and use that information to communicate with patients. The dance/

movement therapist understands the relationship between body and emotion and

uses it in the therapeutic process. Not only has she a heightened awareness of the

other, what is called kinesthetic empathy (Dosamantes Alperson, 1980, 1984;

Dosamantes-Beaudry, 2003; Berger,1972; Levy, 1988), but she is also skilled in

reading the body, its movements and emotional qualities through the Laban/

Bartenieff system.

Rudolph Laban proposed an analytical framework to understand the body and its

movement capabilities (Bartenieff & Lewis, 1980). He spoke of efforts, specifically,

space, weight, time, and flow, and provided a vocabulary to explain movement.

Movement can be a combination of efforts: indirect or direct (space), light or strong

(weight), sustained or quick (time), free or bound (flow). His student, Imgard

Bartenieff (Bartenieff & Lewis, 1980) used these efforts to understand the

88 Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105

123

psychiatric patients she worked with. She observed vast differences between

patients based on their psychiatric illnesses. In comparing two depressed patients

and a schizophrenic patient, she observed significant differences in the expression of

their effort qualities. The depressed patients exhibited heaviness with some

directional movement, and neutral weight, flow, and time. The schizophrenic patient

exhibited a rigid posture, disorganized use of direction, and varying use of flow,

vacillating between extremes of being bound and free. Bartenieff (Bartenieff &

Lewis, 1980) exhibited the usefulness of Laban analysis in connecting specific body

postures and movement to emotional states.

Embodiment

The view of the mind and body as separate entities is found in the works of early

Greek philosophers (Gomperz, 1955) and, in modern philosophy, in Descartes

(1641). Body and mind have traditionally been separated in scientific research,

with a focus on studying the intricacies of the brain (Damasio, 1999). Recent

research has begun to join the two entities, or, rather, has begun to recognize that

they are part of the same integrated system. The literature on embodiment

(Barsalou, Niedenthal, Barbey, & Ruppert, 2003; Koch, 2006; Niedenthal,

Barsalou, Winkielman, Krauth-Gruber, & Ric, 2005) takes a closer look at the

relationship between posture and emotion. Embodied knowledge, or the ‘‘ground-

ing of knowledge in a bodily state’’ (Niedenthal et al., 2005, p. 186), has gained

interest in a number of fields, specifically, linguistics, neuroscience, artificial

intelligence, psychology, social psychology, memory research, and developmental

psychology (Koch, 2006). Particularly important to the work of dance/movement

therapists is the recent work in social psychology and neuroscience, which has

provided sociological and biological explanations for body- and movement-based

therapeutic interactions.

The computer metaphor is the traditional view of information processing in

both social and cognitive psychology. The theory assumes that the software of

the mind is separate from the hardware of the body and the brain (Niedenthal

et al., 2005). That is, the mind functions independently from the physical

functions of the body. Information is received and processed separately from

bodily functions and experience. Since dance/movement therapy assumes an

integration of mind and body, dualism has been seen as antagonistic to the work

of dance therapists.

The dualistic view of cognition, however, has begun to shift in social psychology.

Many researchers and theorists (Niedenthal et al., 2005; Barsalou et al., 2003) are

focusing on an embodiment approach, positing that cognition, attitudes, and

emotions are all grounded in the body (Koch, 2006). Specifically, the literature

increasingly states that perceived bodily states in others produces similar bodily

states in the perceiver (Bavelas, Black, Lemery, & Mullet, 1986; Gallese, 2005;

Iacoboni, 2008; Keysers et al., 2003; Rizzolatti, Fogassi, & Gallese, 2001), and felt

bodily states produce affective experiences in others (Duclos et al., 1989; Riskind,

1984; Riskind & Gotay, 1982).

Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105 89

123

Neurobiology and Mirror Neurons

The recent discovery of mirror neurons sheds light on the neurological underpin-

nings of embodiment. Mirror neurons were originally discovered by Giacomo

Rizzolatti and his colleagues at the University of Parma, in Italy, while studying

monkeys’ motor activities. Those special neurons respond to audio, visual, and

somatosensory stimuli. They fire when the monkey performs an action as well as

when the monkey observes another performing the same action (Keysers et al.,

2003; Rizzolatti, Fogassi, & Gallese, 2001). Similar results have been found in

human subjects (Gallese, 2005; Iacoboni, 2008). Certain parts of the brain have

been found to help us identify individuals when facial cues are not available

(Urgesi, Candidi, Ionta, & Aglioti, 2007). The extrastriate body area, in the lateral

occipital cortex in particular, appears to become active when we view the body and

its parts to enable us to interpret the actions of others without seeing the entire body

or face. This process is implicit, as suggested by Meeren et al. (2005).

The implications of this research are profound. The discovery of mirror neurons

has provided us with a scientific explanation of how humans perceive actions,

how action perception is linked to kinesthetic modes of communication,

kinesthetic empathy first and then empathy, as a mental state (Braten, 2007).

The research on mirror neurons is particularly pertinent to the work of dance/

movement therapists in that it provides scientific support for the mirroring

technique used in dance/movement therapy practice (Berrol, 2006). The purpose

of using mirroring in dance/movement therapy is to both attune to the client and

create an empathic connection. By physically and empathically attuning to clients,

dance therapists activate their patients’ mirror neurons, thus creating a stronger

therapeutic relationship. The capacity of patients to derive meaning from their

bodily-felt experiences has been correlated with positive psychotherapeutic

outcomes (Dosamantes-Beaudry, 1997). But the question remains: How is action

perception related to emotion perception?

In a study by Jackson, Meltzoff, and Decety (2005), functional magnetic

resonance images (fMRIs) were taken of individuals witnessing photographs of

human hands and feet in seemingly painful positions. It was found that when

viewing these pictures, the area of the brain that is associated with pain and affective

experiences was activated. The results indicate that witnessing pain in others

activates the brain in a similar way to feeling pain in oneself. de Gelder, Snyder,

Greve, Gerard, and Hadjikhani (2004) also used fMRI technology to observe

subjects’ neurological responses to images of bodily expressions of fear. It was

found that when viewing these images, areas of the brain known to be associated

with emotional processing were activated, such as the amygdala and the posterior

cingulate. Additionally, areas of the brain dedicated to action representation (e.g.

inferior and middle frontal gyri, precentral gyrus) in motor areas were also

activated, suggesting that emotion is a combination of both neural and motor

processes. In related research, emotion has been found to be a result of the

interaction of cognitive, neural, attentional, and sensory processes (LeDoux, 1995,

1998).

90 Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105

123

The Role of Context

When examining the connection between posture and emotion, it is important to

remember that context most certainly plays a role. Posture is not necessarily viewed

separately from facial expressions. Additionally, emotional feeling and expression

are usually in response to a particularly stimulating situation. Emotions are

regulatory and automatic, and assist both humans and animals in maintaining life

(Damasio, 1999). Emotions exist in order for us to survive (Darwin, 1859; LeDoux,

1998). The primal nature of emotions makes it difficult to induce particular

emotional states or even to simulate situations that might evoke an emotional state.

There is always a chance that simulated emotional states or situations in research

become contrived or inauthentic (Wallbott, 1998; Wallbott & Scherer, 1986).

Additionally, despite research that has shown the universal experience of emotions

across cultures, learning and culture may still affect our emotional processes

(Damasio, 1999).

Regardless of these barriers, it is still important to examine the relationship

between body and emotions. These two topics have been largely ignored as important

areas of study and research. It is only recently that scientific research has found ways

to measure the connections between body and emotions. However, there are questions

still unanswered and clarifications yet to be made. Furthermore, the field of dance/

movement therapy lacks an extensive collection of empirical data on these topics.

This study is an attempt to contribute to this newly burgeoning body of literature and,

additionally, connect it with the field of dance/movement therapy. Context is an

important consideration when studying people’s perceptions of emotions, but steps

must be taken to parse the various elements in this area of exploration. In this study,

posture was used as a means to begin to understand the relationship between the body,

emotion, and perception. Posture was utilized specifically to isolate the body and to

engender a bodily-felt experience in the participants.

Purpose of this Study

The literature review indicates that (1) embodying specific postures can induce

affective states; (2) witnessing others in affective states can also induce affective

states within us; (3) whether we are observing or embodying, similar neurological

functions are being activated. The body and emotions are essential components of

dance/movement therapy, yet there is little empirical research in the field on the

interaction of the two. Hence the purpose of this study is to compare the differences

in emotional experience through embodying and observing.

Method

To explore the difference in emotional recognition between observing and

embodying, the Diagnostic Analysis of Nonverbal Accuracy Test of Posture

(DANVA2-POS) was used as a stimulus to measure judgment accuracy. The

Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105 91

123

original test, as mentioned previously, asks participants to categorize specific

photographs of people in various postures by choosing from four options: happy,

sad, angry, and fearful. There are 24 photographs in total. The purpose of the test is

to measure people’s accuracy in identifying the correct emotion for specific

postures. The current study uses an open-ended format, rather than the original

forced-choice methodology, to allow for greater range of responses from

participants. Two conditions were administered: (1) participants observed a model

embodying each posture from the DANVA2-POS and (2) participants viewed a

photograph of each posture and then embodied the posture. Participants’ written

responses were coded in terms of the basic emotions of sad, happy, angry, fearful,

surprised, and embarrassed/ashamed (see Table 1).

The coding was further differentiated by considering whether participants

responded with words descriptive of emotion or action, while an additional category

of ‘‘non-emotion’’ (no emotional content in responses at all) was also included (see

Appendix for complete lists). Results were compared. Five dance/movement

therapists (with the higher ADTR credentials) were given the researcher’s coding

system in order to validate the categories. Some of the dance/movement therapists

had additional graduate and professional degrees.

Participants

Forty-one people participated in this study; four were male and 37 were female. All

were 18 years of age or older, ranging in age from 23 to 57. Participants were

recruited from the New York City metropolitan area by word-of-mouth and

comprised 16 White/Caucasian, 20 Black/African-American, and 5 Hispanic/Non-

Caucasian individuals. Participants were students in a master’s degree program in

creative arts therapy (dance and art) (classmates of the researcher) or undergraduate

psychology majors (students of the researcher). All participants participated

voluntarily and were randomly assigned to one of the two categories.

Apparatus and Procedure

All research was conducted in classrooms either on the Pratt Institute campus in

Brooklyn, or at The College of New Rochelle, School of New Resources campus in

South Bronx, New York. Participants were asked either to embody each posture

after viewing a photograph of the posture or to observe a trained model (also a

dance/movement therapy student) embodying each posture. The model’s face was

covered to control for biasing effects of facial expressions. The model held each

posture for approximately two seconds. In both conditions, participants were asked

to write the emotion or feeling they associated with each posture. Identical answer

sheets were used for both conditions.

After forms consenting to participation in the study were read and signed, the

researcher explained that the study was looking at the relationship between posture

and emotion and that each participant would be asked (a) to observe someone

embodying postures or (b) to look at photographs of postures and embody the

posture. The participants were then told that they would be asked to write a response

92 Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105

123

after viewing/embodying each posture and that they should respond quickly, writing

their initial response.

Data Analysis

Responses were analyzed based on a coding system developed for the purposes of

the study. Responses were coded based on whether they included the words sad,

happy, angry, fearful, shame, or surprise. The SPSS statistical program was used to

calculate and analyze all data. Responses were recorded in SPSS as ‘‘1’’ if they

Table 1 Mean emotion

responses: standard emotion,

derivation, or synonym

Sad Surprise Embarrassment/Shame

Sad(ness) Wonderment Shy (little girl)

Upset Surprised Shame

(Feel) Lonely Shock(ed) Embarrassed

Feeling sorry Stunned Ashamed

Hopeless Self-conscious

Depressed Fear Regret

Withdrawn Fearful

Mournful Frightened Angry

Rejected Nervous(ness) Angry

Disappointed(ment) Anxious Enraged

Hurt Scaredy cat Mad

Dejected Scared Furious

Let down Worry(ied) Impatient(ce)

Empty Afraid Frustrated

Not too happy Jumpy Fury

Solitary Anticipating(ion) Annoyed

Put down Concerned Defensive(ed)

Alone Apprehensive Rageful

Intimidating Defiant

Happy Cautious Irritated

Happy On edge Passive aggressive

Excited Alert Rebellious

Overjoyed Shaken Pissed off

Complacent Uneasy Uptight

Exhilarated Reserved Extremely intense

Carefree Vulnerable

Enjoyable

Elated

Free

Relaxed

No cares

Comfortable

Gay

Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105 93

123

included a derivation or synonym of any of the words. Action descriptions of

emotional experiences were also coded and were recorded as a ‘‘2.’’ If no emotion

terms were written then the response was recorded as non-emotion and was

recorded as ‘‘0’’ in SPSS. Independent t-tests were performed to compare the mean

responses for each emotion between conditions. A difference in mean responses

between conditions was found to be statistically significant when alpha levels were

greater than .05 (p [ .05).

Results

Results indicate that overall, in this sample, N = 41, participants’ ratings of

postures do not differ on the basis of on whether they are observing a person

embodying postures or whether the participants are embodying the postures

themselves. A comparison of means shows that there is a pattern of agreement

between conditions (see Table 2).

Table 2 t-Test results of subjects

DANVA2-POS answer key Observe condition Embody condition

Posture 1. Sad Sad (.40) Sad (.52)

Posture 2. Fear Fear (.20) Fear (.29)

Posture 3. Fear Fear (.75) Angry (.55)

Posture 4. Happy —Non-emotion— Shame (.05)

Posture 5. Angry Angry (.25) Angry (.43)

Posture 6. Fear Angry (.40) Angry (.38)

Posture 7. Sad Sad (.55) Angry (.29)

Posture 8. Angry Angry (.95) Angry (.71)

Posture 9. Fear Fear (.15) Angry (.29)

Posture 10. Angry Angry (.55) Angry (.81)

Posture 11. Sad Sad (.10) Sad/Angry/Happy (.05)

Posture 12. Sad Sad (.35) Sad (.67)

Posture 13. Happy Angry/Happy (.05) Happy (.14)

Posture 14. Happy Happy (.65) Happy (.50)

Posture 15. Angry Angry (.80) Angry (1.00)

Posture 16. Sad Sad (.35) Sad (.29)

Posture 17. Fear Fear (.30) Fear (.24)

Posture 18. Sad Sad (.35) Sad (.38)

Posture 19. Happy Happy (.20) —Non-emotion—

Posture 20. Happy —Non-emotion— Happy (.14)

Posture 21. Angry Angry (.10) Angry (.33)

Posture 22. Fear Fear (.70) Fear (.43)

Posture 23. Happy Angry/Happy (.20) Happy (.62)

Posture 24. Angry Angry (.30) Angry (.52)

Data codes: 0 = non-emotion; 1 = standard, synonym or derivation; 2 = action description

94 Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105

123

Independent t-tests showed no significant difference in responses between

conditions, except for the emotion of anger, which supports the hypothesis that

embodying a posture and observing a posture elicits similar emotional responses

(see Table 3).

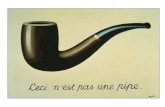

However, it is notable that the participants were found to identify the emotion of

anger more often in the embodiment condition (see Fig. 1).

An independent t-test showed a significant difference (.005) in responses between

conditions for anger. This finding does not support the hypothesis that embodying

and observing produce similar responses; rather, embodying particular postures

generates an anger response more often than simply observing a person embodying

the same postures.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that, generally, people tend to have the same

emotional response whether embodying a posture or observing someone else

embodying the same posture. This supports recent findings in mirror neuron

research, which holds that the same neurological mechanisms are at work when

embodying an action as when watching someone embody the same action. In the

case of the emotion of anger, however, results differed. Participants tended to

identify anger at much higher levels when embodying postures than when observing

postures. One possible explanation for this difference is that the processing of anger

starts first at the limbic brain level (MacLean, 1990; Panksepp, 1992). When the

limbic system (the amygdala, the hypothalamus, and the hippocampus) is

stimulated, body sensations arise in response to threats (fight-flight response) or

physiological needs (hunger, thirst, sleep, etc.), which in turn determine specific

body actions.

The primitive, unconscious, and immediate nature of anger may explain the

differences found specifically with the varying conditions associated with anger. It

is posited that the act of embodying particular postures may have unconsciously

triggered feelings of anger, thereby causing participants in this group to experience

and identify anger more intensely, thus generating a higher agreement level than

those observing others.

In looking at the data, there are clear similarities between the postures that

participants identified as predominantly angry. Postures with crossed arms tended

to be associated with anger. The two postures leaning forward, in a confronta-

tional stance, were associated with anger. All the postures with fists were also

linked with anger. In Laban terms, these postures can be seen as direct, strong,

and bound, which are considered fighting efforts and can be associated with

resistance, confrontation, power, and sometimes even violence (Bartenieff &

Lewis, 1980). A relationship has also been found between making a fist and

feelings of power and hostility, which are feelings often associated with anger

(Schubert, 2004).

Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105 95

123

Tab

le3

Ind

epen

den

tt-

test

resu

lts

Ind

epen

den

tsa

mp

les

test

Lev

ene’

ste

stfo

req

ual

ity

of

var

ian

ces

t-T

est

for

equ

alit

yo

fm

eans

FS

ig.

td

fg

.(2

-tai

led

)M

ean

dif

fere

nce

Std

.er

ror

dif

fere

nce

95

%C

on

fid

ence

inte

rval

of

the

dif

fere

nce

Lo

wer

Up

per

Sad

Eq

ual

var

ian

ces

assu

med

2.9

08

.08

8.8

20

98

2.4

12

.02

.02

1-

.02

4.0

58

Eq

ual

var

ian

ces

no

tas

sum

ed.8

23

97

4.4

92

.41

1.0

2.0

21

-.0

24

.05

8

An

gry

Eq

ual

var

ian

ces

assu

med

27

.32

8.0

00

2.7

25

98

2.0

07

.09

.03

3.0

26

.15

7

Eq

ual

var

ian

ces

no

tas

sum

ed2

.738

96

0.6

01

.00

6.0

9.0

33

.02

6.1

57

Hap

py

Eq

ual

var

ian

ces

assu

med

3.4

47

.06

4.9

31

98

2.3

52

.02

.02

0-

.02

1.0

59

Eq

ual

var

ian

ces

no

tas

sum

ed.9

34

97

1.5

86

.35

0.0

2.0

20

-.0

21

.05

9

Fea

rE

qu

alv

aria

nce

sas

sum

ed.8

31

.36

2-

.42

09

82

.67

5-

.01

.02

5-

.06

0.0

39

Eq

ual

var

ian

ces

no

tas

sum

ed.4

19

96

5.3

04

.67

5-

.01

.02

5-

.06

0.0

39

Sh

ame

Eq

ual

var

ian

ces

assu

med

10

.68

1.0

01

1.6

25

98

2.1

04

.02

.01

3-

.00

4.0

46

Eq

ual

var

ian

ces

no

tas

sum

ed1

.643

84

9.3

35

.10

1.0

2.0

13

-.0

04

.04

6

Su

rpri

seE

qu

alv

aria

nce

sas

sum

ed.1

09

.74

2.1

65

98

2.8

69

.00

.00

8-

.01

4.0

17

Eq

ual

var

ian

ces

no

tas

sum

ed.1

65

98

1.9

49

.86

9.0

0.0

08

-.0

14

.01

7

No

emo

tio

nE

qu

alv

aria

nce

sas

sum

ed1

0.3

75

.00

11

.602

98

2.1

10

.01

.00

6-

.00

2.0

22

Eq

ual

var

ian

ces

no

tas

sum

ed1

.623

78

9.9

93

.10

5.0

1.0

06

-.0

02

.02

1

No

n-e

mo

tio

nE

qu

alv

aria

nce

sas

sum

ed2

.319

.12

8.7

70

98

2.4

41

.02

.03

1-

.03

7.0

86

Eq

ual

var

ian

ces

no

tas

sum

ed.7

70

97

8.7

54

.44

1.0

2.0

31

-.0

37

.08

6

96 Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105

123

As with most research, there are certain limitations in regards to the validity

of the study. An important factor in any research study is the demographics.

Age, gender, educational level, ethnicity, and culture should always be

considered. An obvious potential limitation in this study is gender. Specifically,

37 of the 41 participants were female, which may have skewed the identification

with particular emotions. A gender-balanced participant pool may produce

different results. Also, the participants, trained in dance/movement therapy, had

a heightened awareness level regarding the relationship between body and

emotion. Their responses may possibly have raised the agreement level in this

study more than if none of the participants had been trained in dance/movement

therapy.

Measurement error should also be taken into account. The coding categories were

chosen at the researcher’s discretion and levels of rater agreement were not

determined. Coding the data in a different way may have yielded different results.

Also, as mentioned earlier, the context of the testing environment should always be

considered, especially when studying emotions. Attempting to induce authentic

emotional responses in a laboratory, or (in this case) a classroom setting, may have

produced unreliable results.

Despite such limitations, the study’s findings are important for the field of

dance/movement therapy. The connection between body and emotion are integral

to the work of dance/movement therapists, the direct relationship of these two

entities being at the core of the therapeutic process. The study has provided insight

into these relationships that are difficult to articulate. One, it appears evident that

both embodying a posture and observing someone else embody the same posture

condition21

Mea

n

.3

.2

.1

0.0

SAD

ANGRY

HAPPY

FEAR

SHAME

SURPRISE

Condition 1: Embodiment Condition 2: Observation

Fig. 1 Mean emotion content of participant responses

Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105 97

123

generates similar emotional responses, which is supported by the current

neuroscientific and social psychology literature and research. The findings suggest

that individuals who simply observe others moving in a dance/movement therapy

group experience feelings similar to those members of the group who are moving.

Secondly, anger, being a primary emotion (Cozolino, 2006) and one that is often

viewed as a culturally inappropriate expression, appears to be strongly evoked by

embodying certain bodily postures and gestures. The result directly supports the

therapeutic work often done in dance/movement therapy, where exploration of

anger through embodiment is both appropriate and encouraged.

Further research on these topics is needed, not only to enrich the field of dance/

movement therapy, but also to strengthen and validate the connections between

dance/movement therapy and neuroscience.

Conclusions

To what extent do people agree on which emotions are associated with specific

body postures? The purpose of this study is to take a closer look at the issue,

specifically, to compare the differences in emotional experience through

embodying and observing. Is there a difference in recognition accuracy when

one embodies a posture as compared to simply observing another? The research

on mirror neurons suggests that there is no difference; observing someone

embodying a posture engages the same neurological processes as embodying the

same posture. The results of this study support the mirror neuron research,

indicating that, generally, people tend to have the same emotional response

whether embodying a posture or observing someone else embodying the same

posture. Interestingly, participants tended to identify anger more frequently when

embodying a posture than when observing a posture. Embodying particular

postures may have unconsciously triggered primitive feelings of anger, gener-

ating a higher agreement level from participants in a way that observing others

did not.

The results are particularly intended to enrich the body of literature in the field of

dance/movement therapy as well as to help connect body-oriented psychothera-

peutic work and other mental health professions. The body and its emotions are

essential components of dance/movement therapy, yet there is little empirical

research in the field on the interaction of the two. The findings carry importance for

the field of dance/movement therapy, having helped define the relationship between

body and emotions. This is one step towards bridging the gap between dance/

movement therapy and other disciplines as well as validating the connection

between dance/movement therapy and neuroscience.

98 Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105

123

Appendix

Standard emotion action descriptionASadBad newsSolitaryLet it all outClosed/withinLike at a funeral.Something very melancholy just occurred.Depression is killing me. I have to find a way out of this problem.Keeping it within.Retreat within.Holding within emotions and speech.I’m down andI’m feeling like I’m thinking about something serious.

AngryYellingShouting at someoneScowlingYou want a piece of me!!!Ready to fight(Being) Aggressive(ness)So what!Ready to get loud.Not getting her wayAttackCombativeDon’t give me attitude!Confrontational“I’ll tell you what!”Ready to fightWanting to explodeTightGuardedTenseLookin’ for a fightConfrontational. In your face.Feeling clenched and also ready to burst.Here I am about to leap up at a negative reaction someone caused me.Ooh! I just wanna…I am really trying to hold back from expressing my feelings (frustration).Here I am refraining from jumping up from my seat to interact angrily at something!This made me think about karate.I’m fed up with the whole thing. Attitude! I don’t care!Stop bothering me. When I express myself this way I feel everyone will take me seriously.I don’t want to hear it. We’ll talk later.I can fight. Don’t get me wrong.Why don’t kids ever listen? I feel like it’s time to put them in their place.About to pop.Ready to pounce.Pre-emptive defensesGet away!Stop! Don’t!Now wait a minute!Not trying to hear anyone right nowCome and get me or take me as I amDefensive or to do something or perhaps strike someone.Stop.Stop, don’t do thatOn the verge of burstingStop! Enough.Why is life so hard? Especially when you are looking for a better life?Scolding someone.

HappyYeah! I did it.Oh boy!Life is great!Wow that was greatIn loveOpenSurrenderYelling hoorayLightFree but also strong.Release—let go

FearSaw something horribleNot open, guardedI am going to get youThreatenedStay back“On edge”AvoidingWarding offStay away you will contaminate me.Looking with concernI felt as thought I walked into the middle of a hold up.This feels like a readiness stance where I should be preparing for something.I’m so nervous that I don’t know if I did a good job today at work.Look at me when I’m speaking. I’m not afraid of you.Oh my God there’s a rat on the floor. Do something!Bracing(ed) oneself (for something)Wanting to leave my chair as soon as possible.RigidProtective/ProtectedBoundStressed outSuddenly “frozen.”I feel confused and I don’t know what to do with this problem. It bothers me so much, I have a headache.The endFeeling stressedCan’t let goThere is a problemSomewhat uncomfortable and tense.Braced.

Embarrassment/ShameVery low self esteem. Everybody is looking nice except for me.HidingTrying to cover something up.Not confident presence.Self-consciousWhat did I do? Why did I do that? Regret.

No Feeling Numb, no feeling associatedDissociatedNo strong feeling associatedFeeling very minimum emotion. This person can’t extend themselves outward.Detached from below.Detached.“checked out”EmptyRemoved

Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105 99

123

Appendix continued

Non-emotion responses and action descriptions

Relaxed(ing)GazingThinking (hard) (hard about something) (about something heavily)In conversationInterrogating someoneTiredLazyPosingPatientStretchingElegantListening (to someone)Observing (something)QuestioningLooking (at something)Chilling (out)Seeing a girlfriendGetting up from her chairPaying attentionSitting like a dudeWaiting (for something) (on Mr. Right) (for the train) (for a response while sitting down)

(for a bus) (for her stop)Staring at a painting or artDon’t know the answerIt’s not coming outThat guy looks good over thereSo you do like him huh!Now that sandwich looks good on her plate.Watching a movieAsleep, SleepingRiding the bus (train)Looking at her new shoesIt’s easy!But what happenThis class is boringStudy(ing something)RestingHelloRiding a bikeLooking like a psychologistCreepingPraying (to God)Frozen in thoughtAttentiveCalmTired ofNot interestedTrying hard to pay attention, but boredProper-attentionOpennessHanging (out)LeaningPlaying

NappingSkiingEntertainingStrainingStanding in lineTrying to stopMeditatingWhatever!!NoisyDon’t care!StrongBeing a manHey, I am here!Range modeLooking (at a man)(Trying to be) sexyTell me what!What!!!Ask me if I care.AdvertisingWhat happenLaid backGangsta leanLeg crossedTake my pictureI have to use the bathroomThinking about boysWaitStarringBoredHolding her kneeFolding armsHolding her headCrossing/folding armsStanding firmWave and say hiGetting attentionSitting with gestureGesture like a manFlyingWhat do you want?Educated woman sittingMan styleStand(?) settingWanderingFriendlyWhat will I have to eat today?I’m convinced!I’m the shit!!PowerfulConfidentLeave me aloneWhen will this train arrive?I’m hungryVery smart (educated)

B

100 Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105

123

Appendix continued

I give my all to youFallingTalking movementEagerHo-humContemplativeDaydreamingLady likeTrying to pick up a girl (cool dude pose)Perfect posture (trained)Holy/to the angelsThe way we sit in class or at the moviesToughBoredomAloofOff-guard“What!?”“Wait!”Nonchalant“cool”GivingPraisingInterestedAwake/aliveConfusedPensiveWith attitudeSleepyCuriousColdUm…Too cool for school“Let me tell you something...”Is it time to go yet?ArrogantAwaitingExpecting“Stop”DisciplineStrictEagerSeductiveLooseRudeUnconsiderateSelf-centeredSternHeld togetherIntrospectiveCasualOn showEntertainingNot fully comfortableReady to moveStrainedIn painForcingSecureReaching (out)InvestedPresentComposed

GroundedTrustingUnder control(led)ReliefDay dreamingStationaryMockingSitting on a toiletFalling asleepSolitaryMasculineEpiphanyReflectiveEngagedReady, waiting, in controlConflictedOver-looking somethingDisinterestedPassiveUncertaintyNeutralEnlightenedReceiving of the worldWell-manneredPoliteUnsureUnstableI’m the boss.Distracted from the moment, but focused on something.Keeping it cool and relaxed.Adjusting on the toilet.ContainedStatueSet in a purposed state.WelcomingCerebralUnsureBlunt.Don’t care or want to seem that way.Childish response.Feeling very uncomfortable and wrong.Uncertain with the body.Putting eyes down out of respect.Up and away!Nonchalant.Hug for myself.Ready for the act.Resisting.Strong, still, and open.Inviting (others). Receptive.At easeWaiting/anticipatoryInquisitiveReservedSafeThoughtfulUncomfortableHungryOpen for discussionOut of control

Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105 101

123

Appendix continued

RestrictedUnbalancedThought provokingunaffectionatein a conversationWittyLooking at tvTalkingInquisitiveExerciseNot sure what just happenedWonderingDebatingSmoking a cigaretteBehind is hurtingUndecidedLaid backTaking a breatherInterviewingJust sittingUsing good postureLooking at my heelHere I am.CalmGetting upIntriguedIn church/praiseExercisingThinking of thingsWait a minute, stopLack of interestFocusedYawningConcentratingProcessing thoughtsHere I amWaiting to talkDeep in thoughtExhalingGetting ready to get upContemplationOpen with anticipationRelievedSchemingPondering about somethingNoddingReached a goalPuzzledThis makes me feel like I’m standing and checking out the area.Here I am casually standing, talking with friends.I thought that something was over and began to get up too quick.This position makes me feel as though I am surrendering my whole being to “God.”Makes me feel like I’m getting involved with something.

I felt like I was in a Michael Jackson video.I’m listening to my professor trying to stay focused.Just laid back, not a care in the world, my mind is just wandering.I felt as though I were refusing to do somethingLook at him standing like that. He thinks he is all that and cool.Exercising the legs and pushing myself up helps me be in shapeStretching back helps me relaxWhat’s wrong? Anything I can do for you. I’m listening.Working all day makes me want to go to sleep on this chair.I feel like a macho man. I see the world differently.Stretching myself. Standing up. Pull my hands out. Brings back my energy.I like to listen to people when they are speaking. I like to touch my legs.The thinking chair, and also it’s very relaxing.Everything is working nice and smooth. I can do this.Stand up and having my hands crossed. That means I’m ready to go home.My arms are open if anybody needs a hug.Who cares what people think of me? I can sit however I want.Jerking.Like I’m cool; a smart aleck – cool guy.As if I’m slightly raising my hand to answer a question.Attempting as though I was about to get up suddenly.As I am trying to learn a step or new move.Just sitting awaiting to hear my call.Feeling as if I am waiting patiently for my turn to come up.Like a man sitting with his leg crossed.Attempt to exhaust the body.Feel like I’m in a waiting room dealing with the surroundings of people.I feel I was sitting at attention.Going into a relaxation mode.Observing or listening to someone or watching something that has my attention.Promiscuous; flirting, “rebel-ish” with relaxing to be the assumptionAttentive; observantStanding feeling feminine – daintySubmissive; being looked at/watchedFeel as though I am close-minded, ready to depart from where I am at.I felt as though I were under arrest and asking “why?”

102 Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105

123

References

Barsalou, L. W., Niedenthal, P. M., Barbey, A. K., & Ruppert, J. A. (2003). Social embodiment. In B.

Ross (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 43, pp. 43–92). San Diego: Academic

Press.

Bartenieff, I., & Lewis, D. (1980). Body movement: Coping with the environment. New York: Gordon and

Breach.

Bavelas, J. B., Black, A., Lemery, C. R., & Mullet, J. (1986). ‘‘I show how you feel’’: Motor mimicry as a

communicative act. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(2), 322–329.

Bente, G., Kramer, N. C., Petersen, A., & De Ruiter, J. P. (2001). Computer animated movement and

person perception: Methodological advances in nonverbal behavior research. Journal of NonverbalBehavior, 25(3), 151–166.

Berger, M. R. (1972). Bodily experiences and expression of emotion. American Dance TherapyAssociation, Monograph 2, 191–230. Columbia, MD: ADTA.

Berrol, C. F. (2006). Neuroscience meets dance/movement therapy: Mirror neurons, the therapeutic

process and empathy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 33, 302–315.

Bianchi-Berthouze, N., Cairns, P., Cox, A., Jennett, C., & Kim, W. W. (2006). On posture as a modality

for expressing and recognizing emotions. Emotion and HCI workshop at BCS HCI London,

September, 2006.

Bickmore, T. (2004). Unspoken rules of spoken interaction. Communications of the ACM, 47(4), 38–44.

Boone, R. T., & Cunningham, J. G. (1996). Children’s understanding of emotional meaning in expressivebody movement. Poster presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child

Development, Washington, DC.

Boone, R. T., & Cunningham, J. G. (1998). Children’s decoding of emotion in expressive body

movement: The development of cue attunement. Developmental Psychology, 34, 1007–1016.

Braten, S. (Ed.). (2007). On being moved: From mirror neurons to empathy. Amsterdam: John Benjamin

Publishing Company.

Chodorow, J. (1995). Body, psyche, and the emotions. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 17(2),

97–114.

Coulson, M. (2004). Attributing emotion to static body postures: Recognition accuracy, confusions, and

viewpoint dependence. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 28(2), 117–139.

Cozolino, L. (2006). The neuroscience of human relationships: Attachment and the development of thesocial brain. New York: Norton.

Daems, A., & Verfaillie, K. (1999). Viewpoint-dependent priming effects in the perception of human

actions and body postures. Visual Cognition, 6(6), 665–693.

Damasio, A. R. (1999). The feeling of what happens: Body and emotion in the making of consciousness.

Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace.

Darwin, C. (1859). On the origin of species. London: J. Murray.

Darwin, C. (1872). The expression of the emotions in man and animals. London: J. Murray.

de Gelder, B., Snyder, J., Greve, D., Gerard, G., & Hadjikhani, N. (2004). Fear fosters flight:

A mechanism for fear contagion when perceiving emotion expressed by a whole body. Proceedingsof the National Academy of Sciences, 101(47), 16701–16706.

De Silva, P. R., & Bianchi-Berthouze, N. (2004). Modeling human affective postures: An information

theoretic characterization of posture features. Computer Animation and Virtual Worlds, 15, 269–

276.

Descartes, R. (1641). Meditations on first philosophy (with selections from the objections and replies).(M. Moriarty, Trans., 2008). New York: Oxford University Press.

Dosamantes Alperson, E. (1980). Contacting bodily-felt experiencing in psychotherapy. In J. E. Shorr, G.

E. Sobel, P. Robin, & J. A. Connella (Eds.), Imagery: Its many dimensions and applications (pp.

223–250). New York: Plenum.

Dosamantes Alperson, E. (1984). Experiential movement psychotherapy. In P. L. Bernstein (Ed.),

Theoretical approaches in dance/movement therapy (Vol. 2, pp. 257–291). Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/

Hunt.

Dosamantes-Beaudry, I. (1997). Somatic experience in psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic Psychology,14(4), 517–530.

Dosamantes-Beaudry, I. (2003). The arts in contemporary healing. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105 103

123

Duclos, S. E., Laird, J. D., Schneider, E., Sexter, M., Stern, L., & Van Leighten, O. (1989). Emotion

specific effects of facial expressions and postures on emotional experience. Journal of Personalityand Social Psychology, 57(1), 100–108.

Ekman, P. (1965). Differential communication of affect by head and body cues. Journal of Personalityand Social Psychology, 2(5), 725–735.

Ekman, P. (1970). Universal facial expressions of emotion. California Mental Health Research Digest, 8,

151–158.

Ekman, P. (1972). Universals and cultural differences in facial expressions of emotion. In J. Cole (Ed.),

Nebraska symposium on motivation 1971 (Vol. 19, pp. 207–283). Lincoln, NE: University of

Nebraska Press.

Ekman, P. (1973). Darwin and facial expression; A century of research in review. New York: Academic

Press.

Ekman, P. (1992). Are there basic emotions? Psychological Review, 99(3), 550–553.

Ekman, P. (1994). Strong evidence for universals in facial expressions: A reply to Russell’s mistaken

critique. Psychological Bulletin, 115(2), 268–287.

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1967). Head and body cues in the judgment of emotion: A reformulation.

Perceptual and Motor Skills, 24, 711–724.

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1971). Constants across cultures in the face and emotion. Journal ofPersonality and Social Psychology, 17, 124–129.

Ekman, P., Sorenson, E. R., & Friesen, W. V. (1969). Pan-cultural elements in facial displays of

emotions. Science, 164(3875), 86–88.

Gallese, V. (2005). Embodied simulation: From neurons to phenomenal experience. Phenomenology andthe Cognitive Sciences, 4, 23–48.

Gomperz, T. (1955). Greek thinkers: A history of ancient philosophy (Vol. I–IV). New York: The

Humanities Press.

Haidt, J., & Keltner, D. (1999). Culture and facial expression: Open-ended methods find more expressions

and a gradient of recognition. Cognition and Emotion, 1, 250–256.

Iacoboni, M. (2008). Mirroring people: The new science of how we connect with others. New York:

Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Izard, C. E. (1994). Innate and universal facial expressions: Evidence from developmental and cross-

cultural research. Psychological Bulletin, 115(2), 288–299.

Jackson, P. L., Meltzoff, A. N., & Decety, J. (2005). How do we perceive the pain of others? A window

into the neural processes involved in empathy. NeuroImage, 24, 771–779.

James, W. (1932). A study of the expression of bodily posture. Journal of General Psychology, 7,

405–437.

Keltner, D., & Shiota, M. N. (2003). New displays and new emotions: A commentary on Rozin and

Cohen (2003). Emotion, 3(1), 86–91.

Keysers, C., Kohler, E., Umilta, M. A., Nanetti, L., Fogassi, L., & Gallese, V. (2003). Audiovisual mirror

neurons and action recognition. Experimental Brain Research, 153, 628–636.

Kleinsmith, A., De Silva, P. R., & Bianchi-Berthouze, N. (2005). Recognizing emotion from postures:

Cross-cultural differences in user modeling. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 3538, 50–59.

Kleinsmith, A., De Silva, P. R., & Bianchi-Berthouze, N. (2006). Cross-cultural differences in

recognizing affect from body posture. Interacting with Computers, 18(6), 1371–1389.

Koch, S. C. (2006). Interdisciplinary embodiment approaches: Implications for creative arts therapies. In

S. C. Koch & I. Brauninger (Eds.), Advances in dance/movement therapy: Theoretical perspectivesand empirical findings (pp. 17–28). Berlin, Germany: Logos Verlag.

Kudoh, T., & Matsumoto, D. (1985). Cross-cultural examination of the semantic dimensions of body

posture. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(6), 440–446.

LeDoux, J. (1995). Emotions: Clues from the brain. Annual Review of Psychology, 46, 209–235.

LeDoux, J. (1998). The emotional brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. New York:

Simon & Schuster.

Levy, F. J. (1988). Dance movement therapy: A healing art. Reston, VA: AAHPERD.

MacLean, P. D. (1990). The triune brain in evolution: Role in paleocerebral functions. New York:

Springer.

Meeren, H. K. M., van Heijnsbergen, C. C. R. J., & de Gelder, B. (2005). Rapid perceptual integration of

facial expression and emotional body language. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,102(45), 16518–16523.

104 Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105

123

Montepare, J., Koff, E., Zaitchik, D., & Albert, M. (1999). The use of body movements and gestures as

cues to emotions in younger and older adults. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 23(2), 133–152.

Niedenthal, P. M., Barsalou, L. W., Winkielman, P., Krauth-Gruber, S., & Ric, F. (2005). Embodiment in

attitudes, social perception, and emotion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(3), 184–211.

Ortony, A., & Turner, T. (1990). What’s basic about basic emotions? Psychological Review, 97(3), 315–

331.

Ortony, A., & Turner, T. (1992). Basic emotions: Can conflicting criteria converge? PsychologicalReview, 99(3), 566–571.

Panksepp, J. (1992). A critical role for ‘‘affective neuroscience’’ in resolving what is basic about basic

emotions. Psychological Review, 99(3), 554–560.

Petti, V. L., Voelker, S. L., Shore, D. L., & Hayman-Abello, S. E. (2003). Perception of nonverbal

emotion cues by children with nonverbal learning disabilities. Journal of Developmental andPhysical Disabilities, 15, 23–36.

Pitterman, H., & Nowicki, S. (2004). A test of the ability to identify emotion in human standing and

sitting postures: The diagnostic analysis of nonverbal accuracy-2 posture test (DANVA-POS).

Genetic, Social and General Psychology Monographs, 130(2), 146–162.

Riskind, J. H. (1984). They stoop to conquer: Guiding and self-regulatory functions of physical posture

after success and failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 479–493.

Riskind, J. H., & Gotay, C. C. (1982). Physical posture: Could it have regulatory or feedback effects on

motivation and emotion? Motivation and Emotion, 6, 273–298.

Rizzolatti, G., Fogassi, L., & Gallese, V. (2001). Neuropsychological mechanisms underlying the

understanding and imitation of action. Neuroscience, 2, 661–670.

Russell, J. A. (1994). Is there universal recognition of emotion from facial expression? A review of the

cross-cultural studies. Psychological Bulletin, 115(1), 102–141.

Schouwstra, S. J., & Hoogstraten, J. (1995). Head position and spinal position as determinants of

perceived emotional state. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 81, 673–674.

Schubert, T. W. (2004). The power in your hand: Gender differences in bodily feedback from making a

fist. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(6), 757–769.

Sternglanz, R. W., & DePaulo, B. M. (2004). Reading nonverbal cues to emotions: The advantages and

liabilities of relationship closeness. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 2(4), 245–266.

Urgesi, C., Candidi, M., Ionta, S., & Aglioti, S. M. (2007). Representation of body identity and body

actions in extrastriate body area and ventral premotor cortex. Nature Neuroscience, 10(1), 30–31.

Wallbott, N. (1998). Bodily expression of emotion. European Journal of Social Psychology, 28, 879–896.

Wallbott, H. G., & Scherer, K. R. (1986). Cues and channels in emotion recognition. Journal ofPersonality and Social Psychology, 51(4), 690–699.

Winters, A. (2005). Perceptions of body posture and emotion: A question of methodology. The NewSchool Psychology Bulletin, 3(2), 35–45.

Author Biography

Allison F. Winters, MA, MS, DTR Ms. Winters holds two master’s degrees, one in dance/movement

therapy from Pratt Institute, New York, the other in psychology from The New School in New York. Her

research, Perceptions of body posture and emotion: A question of methodology, was published in The

New School Psychology Bulletin. She is a therapist in the inpatient psychiatry department at Mount Sinai

Hospital in New York City and adjunct faculty at the graduate school of The College of New Rochelle

(New Rochelle, New York).

Am J Dance Ther (2008) 30:84–105 105

123