Elements of the Historic Jazz Setting in a High School Setting

description

Transcript of Elements of the Historic Jazz Setting in a High School Setting

-

University of Illinois Press and Council for Research in Music Education are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education.

http://www.jstor.org

Council for Research in Music Education

Utilizing Elements of the Historic Jazz Culture in a High School Setting Author(s): Andrew Goodrich Source: Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, No. 175 (Winter, 2008), pp. 11-

30Published by: on behalf of the University of Illinois Press Council for Research in Music

EducationStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40319410Accessed: 11-05-2015 08:12 UTC

REFERENCESLinked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40319410?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Utilizing Elements of the Historic Jazz Culture in a High School Setting

Goodrich Jazz Culture

Andrew Goodrich Northwestern State University Natchitoches, Louisiana

ABSTRACT This qualitative study is an examination of the incorporation of elements of the historic jazz culture in a high school jazz band. Ethnographic techniques were used during one semester of instruction to explore the role of a director and students in learning jazz music via traditional methods. Data analysis revealed that elements of the historic jazz culture can occur in a high school setting under the supervision of the director. In this study three themes emerged which served as the filtered elements of the historic jazz culture utilized by the director of this ensemble: (a) listening for style, (b) improvisation, and (c) learning the lingo.

Jazz, created in America through the blending of the music of many other cultures and hailed by Europeans as the one "truly American" gift to music, has progressed from the bars and bordellos of New Orleans, through the speakeasies of the twenties, across the dance floors of the Glenn Miller era, into the nightclubs of today (Murphy & Sullivan, 1968, p. 17).

For the first half of the twentieth century the performance context of jazz music resided primarily in dance halls, clubs, brothels, and via the radio and phonograph recordings (Gottleib, 1996). The informal learning environment for jazz most often occurred in these locales and media late at night and provided the primary aural con- texts for jazz consumption. Historically, mentoring in the jazz culture served as the

primary medium for learning this music. Musician Sam Price recalled his experiences with jam sessions in Kansas City, one of the cradles of early jazz:

I remember once at the Subway Club, on 18th Street, I came by a session at about 10 o'clock and then went home to clean up and change my clothes. I came back a little after one o'clock and they were still playing the same song (Shapiro & Hentoff, 1955, p. 288).

Performing in these locales with patrons of questionable character formed a key com-

ponent of the jazz lifestyle. Mary Lou Williams reminisced about life as a jazz musician in Kansas City in the 1920s:

11

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education Winter 2008 No. 175

Now, at this time, which was still Prohibition . . . most of the night spots were run by politicians and hoodlums, and the town was wide open for drink- ing, gambling, and pretty much every form of vice. Naturally, work was plentiful for musicians, though some of the employers were tough people (Shapiro & Hentoff, 1955, p. 288).

With jazz performance came a lifestyle of living on the road, playing in clubs, and learning a whole new language of phrases. As jazz music evolved, verbal lingo also formed an integral component of the jazz experience. In addition, jazz "unlike some forms of Western music . . . has been based primarily on a tradition of listening and

performing" (Horowtiz and Nanry, 1975, p. 25). Jazz music, spawned in these less than desirable venues, quickly transformed into

the popular music of its day. Writers, including F. Scott Fitzgerald, helped to sum up this lifestyle in the 1920s as "The Jazz Age" (Horowitz and Nanry, 1975). How then, could a music forged in the depths of prostitution, gambling, and alcohol have found its way into the school environment?

The purpose of this study was to examine a successful high school jazz band and to gain insight into which elements of the historic jazz culture occurred in this particular jazz ensemble. During the course of this study it became evident that elements of the historic jazz culture were present in this ensemble. Questions that guided this study included:

1. What elements of the historic jazz culture occurred in this high school jazz band?

2. How did the director in this study filter and incorporate these elements into a high school setting?

The inclusion of the historic jazz culture will be discussed in the following sections with the following headings: History of Jazz in the Schools, Definitions of Culture; and Studies of Jazz Culture.

History of Jazz in the Schools Jazz music entered into the schools via extracurricular routes (Suber, 1976). Students at historically black colleges including Fisk University and Alabama State performed in dance bands at their schools during the 1920s and 1930s (Ferriano, 1974; Goodrich, 2001). These extra curricular dance bands, often referred to as "stage bands" to avoid the sinful connotations of jazz music in the South, provided an opportunity for students to hone their jazz skills in an informal learning environment (Suber, 1976).

During the post war era jazz ensembles entered the schools at a swift rate, and in 1947 North Texas State College became the first college to offer a degree program in jazz (Scott, 1973). This proliferation of jazz ensembles paralleled the growth of concert bands in the public schools earlier in the twentieth century (Mark, 1987) and can be attributed to two factors: World War II and the evaporation of the professional big band scene in jazz music. World War II veterans, many of which had jazz experience,

12

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Goodrich Jazz Culture

attended college on the G.I. Bill, graduated, and became music educators (Suber, 1976). Concurrently, the demise of the popularity of the jazz big bands sent many jazz musicians looking for other means of employment, which they found as secondary and

college level music educators, forming jazz bands in their school music programs (Hall, 1969).

As jazz music moved from functioning as an art form within the larger culture to an educational medium within the schools, certain elements of jazz were either lost or

homogenized. Music educators who were World War II veterans retired, and teachers trained in the formal procedural knowledge of concert bands became the new jazz band directors, possessing little or no jazz experience. With this transformation, many music educators no longer taught their students how to perform jazz music via the informal traditional aural methods - learning songs by ear, modeling a favorite player or players, or by listening to jazz groups. Instead, a greater emphasis was placed upon learning how to read music and play the correct articulations from a printed page. Improvising became an art form relegated to reading written solos, or at best reading chord symbols, instead of relying solely on developing ones ear. Jazz lingo was replaced with a new terminology borrowed from the concert band idiom including, "Be sure to release this note on the third beat," or "Use the proper amount of air when articulating this quarter note." Jazz culture historically is different from school culture. Today, jazz ensembles are prevalent in

public schools, colleges, and universities. The International Association for Jazz Education

(IAJE) boasts an active membership of 8,000 teachers, musicians, students, music indus-

try representatives, and enthusiasts in thirty-five countries (www.iaje.org).

Definitions of Culture Beattie (1964) defines culture as "the whole range of human activities which are learned . . . and which are transmitted from generation to generation through vari- ous learning processes" (p. 20). Ortner (1990) describes the interactions involved in cultural transmission [informal learning] that can be structured "with the sponsoring person(s) defined as the host(s), [and] the recipient(s) of the largesse as the guest(s)" (p. 60). Rogoff(2003) cites Vygotsky who identifies components of a culture in which "Cultural-historical development changes across decades and centuries, leaving a legacy for individuals in the form of symbolic and material technologies (such as literacy, number systems, and computers) as well as value systems, scripts, and norms" (p. 65). Rogoff (2003) explains the participants' perspective in a culture as "People develop as

participants in cultural communities. Their development can be understood only in

light of the cultural practices and circumstances of their communities - which also

change" (RogofF, 2003, p. 3). For the purpose of this study jazz culture is defined as the transmission of knowl-

edge of historical jazz practices (both informal - mentoring; and formal - private les-

sons) through interaction between the teacher and student via guided learning. The goal

13

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education Winter 2008 No. 175

is for the students to become participants in the jazz cultural community which may include an "accumulated store of symbols, ideas, and material products associated with a social system" (Johnson, 1995, p. 68). Jazz music includes symbols (e.g., notation; his- toric personalities; musical gestures), ideas (e.g., performance practices; improvisation; cultural, ethnic, gender stereotypes), and materials (e.g., charts, recordings).

Studies of Jazz Culture Researchers have examined the cultural impact and uniqueness of jazz music in American society and argue for its inclusion in the public schools (Arnold, 1979; Hall, 1969). Horowitz and Nanry (1975) describe jazz as a social phenomenon, a "manifesta- tion of collective behavior" that is not "bounded by individuals" (p. 25).

Jazz musicians form their own communities (Stebbins, 1964) and need to be open to new identities in jazz if it is to remain "a vital ground of social and cultural renewal" (Ake, 1998, p. 273). In his book, Thinking in Jazz, Berliner (1994) interviewed numer- ous well-known jazz musicians to discover their opinions and expertise on how they improvise in jazz.

Students who perform in a school jazz ensemble learn the procedural knowledge of their instrument from their participation in a concert band. Leavell (1996) reflects on this issue, noting that students have to accommodate musical techniques in jazz band that are different from those used in concert band from both a cognitive and physical standpoint.

Evidence exists to support the notion that students emulate professional jazz musi- cians through interaction at clinics, festivals, listening to recordings of professionals, and by performing their arrangements (Ferriano, 1974). Researchers have examined the teaching of improvisation. In his landmark study, Payne (1973) discovered that the most common method for teaching improvisation included guided listening and improvising using chordal and blues approaches. Jazz instructional aids including play- along recordings do provide a benefit for learning jazz improvisation (Flack, 2004). Bash (1983) reminds practitioners of jazz education "that jazz performance is an aural experience" and that guided listening is essential for developing one's ears (p. 110). Directors need to encourage all of their students in the jazz ensemble to improvise (Mack, 1993). Developing musicianship while improvising contributes to a higher level of learning and performance (Di Girolamo, 1974) as does modeling jazz innovators (Carlson, 1980; Moorman, 1984; Williams & Richards, 1988). Teaching improvisa- tion can include jazz theory, how to imitate melodies and solos, and listening to live jazz performances and recordings (Madura, 1996), in addition to experimentation with melodic and rhythmic development and manipulation of expressive elements of improvisation (May, 2003).

14

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Goodrich Jazz Culture

METHOD Site and Participants The site selected for this study was Crescent Valley High School in the northern suburbs of a large metropolitan area with an enrollment of approximately 1600 students for the 2000-2001 academic year. Criteria for selection of a high school jazz band for this study included the reputation of the director and jazz band, honors and awards earned by the ensemble at the state level, and a high performance level and dedication from the student members. The Crescent Valley High School Jazz Band I has a reputation in the state as an exemplary high school jazz band. A director of jazz studies at a university in the area along with public school educators helped to confirm that this program war- ranted study. The jazz band has won superior ratings at a nearby University Jazz Festival and also at the district and state level. Participants in this study included the director and students in the Crescent Valley High School Jazz Band I.

Ray Hutchinson, the director, has earned a bachelors degree in music education and a masters degree in music education. Hutchinson has taught at Crescent Valley High School for six years. Prior to teaching at Crescent Valley, Hutchinson taught in Ontario, Canada for four years. Despite ten years of teaching experience, Hutchinson remarked, "I don't really consider myself a jazz musician. I'm more of a jazz experimen- talist." During the year of this study Hutchinson held the office of president-elect for the state chapter of the International Association for Jazz Education (IAJE).

The Program The jazz program at Crescent Valley High School consists of three jazz ensembles. The

top two ensembles are big bands comprised of 21 students each, utilizing traditional instrumentation: five trumpets, five trombones, five saxophones (two altos, two tenors, one baritone), and a four-piece rhythm section consisting of drums, piano, bass guitar, and electric guitar. Two drummers and two piano players alternate on each song. The third jazz ensemble is a lab class for students to practice improvising. The instrumenta- tion and size of this class varies each semester.

The rationale for studying Jazz I included criterion-based selection to allow for a rich data set and thick description (Maxwell, 1996). In addition, I utilized purposeful sampling to help select an information-rich case study and chain sampling - I sampled people who knew people who knew which jazz band would yield a plethora of informa- tion - to help determine which school jazz ensemble I should study (Patton, 2002, p. 243). Participants in Jazz I range in age from 14 to 18 years old. The gender and ethnic

composition of this ensemble included nineteen males and two females; three Hispanic students, and 18 Caucasian members. The majority of the students began playing their instruments in the fifth grade, and many of the students in this study reported as having prior performing experience with a jazz ensemble in junior high school. All of the Jazz I members perform in one of the concert bands at Crescent Valley High School and

15

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education Winter 2008 No. 175

are required to participate in the marching band, including members who do not play a traditional marching band instrument. Rhythm section members (piano, guitar, bass guitar) are encouraged to join the percussion section if they do not play other instru- ments. During the time of this study the pianists played marching French horns and the bass guitarist played the trumpet. This requirement does not apply to the lab class, which is an improvisation class open to any student in the school.

All three jazz ensembles met for course credit. Crescent Valley High School is on a four period block schedule. Jazz I rehearses daily from 6:30 a.m. to 7:30 a.m. during "zero hour," Jazz II rehearses after school on Tuesdays from 3:00 - 4:00 p.m., and the lab class meets during fourth period of the school day.

Data Collection Data collection during this study adhered to ethnographic techniques including field notes in rehearsals and sectionals observations, audio and video recordings, formal inter- views, informal conversations, and collection of artifacts. In accordance with Creswell (1998) who states, "An ethnography is a description and interpretation of a cultural group or system," data collection methods utilized in this study also aided in helping me to "examine the group s observable and learned patterns of behavior, customs, and ways of life." (p. 58)

I chose a non-intervention protocol for observations, which allowed for minimum distraction on my part with the participants involved in this study during rehearsals. I observed eight rehearsals of the Crescent Valley High School Jazz I over a two-and-a- half month period during the fall semester of the 2000-2001 academic year. Field notes were written by hand on a yellow legal pad during rehearsal observations with times indicated in the left hand margin to indicate events in a chronological order. Field notes were retyped in word format for ease of reading and coding of data.

I developed an interview protocol at the beginning of this study to aid in my field notes taken during the interviews and to organize materials including headings and concluding thoughts at the end of each interview. Interview questions were designed to discover information relating to the learning culture of this jazz band and whether any elements of the historic jazz culture were present. I interviewed five participants based on the directors recommendations in addition to my observations of student leader- ship. Interviews were conducted on a one-to-one basis, audio-taped, and occurred at the school. Interviewees included the director, who was Caucasian, and five students of which two were Hispanic and three were Caucasian. No African Americans or other races were represented in the ensemble.

I collected data via informal conversations with the participants in this study. The use of unstructured interviews allowed me to remain flexible and open to individual differences and changes throughout the study (Patton, 2002). For example, I often gained information from the director as he walked around the Fine Arts complex in the

16

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Goodrich Jazz Culture

morning unlocking all of the doors. I also spoke with the students as they entered the

building and occasionally during a break in their warm up process before rehearsals. In addition to observations and interviews, the collection of artifacts provided

an additional contextual dimension of data collection for this study (Glesne, 1999). Artifacts included concert programs, recordings of the ensemble, and hand written notes (e.g., ensemble rehearsal schedule for the next week) from the director.

Data Analysis and Trustworthiness Data analysis occurred throughout the entire duration of this study and contributed to a

systematic and in-depth interpretation of the data collected (Patton, 2002). Procedures utilized for analyzing data included transcribing and coding the data. Themes and

concepts grounded in the data emerged from the data analysis, and I developed these

concepts in the writing process which resulted in a rich data set and allowed for thick

description in the final report (Maxwell, 1996). Trustworthiness in this study was

accomplished via the triangulation of data, conducting member checks, peer review, and external audits in addition to the reporting of my biases.

Field notes from the observation and interview protocols revealed three types of information including the descriptions of the site and participants, rehearsal activities and materials used, and interactions among the director and student participants. Field notes and interviews were transcribed the same day upon completion of the observation or interview.

Once the transcription process was completed I then analyzed the information for

specific data based upon a system of coding. Coding revealed key themes that emerged throughout the analysis process. Themes identified in this study received a two or three letter code designation.

The letter "D," for example, represented the director of the jazz band, and the let- ters "DT" signified the director teaching. I notated codes by hand in the left margin of the transcripts of observations, rehearsals, and interviews for ease of reading and identification. I then grouped the coded data in a computer file using separate the- matic headings (e.g., "JC" for Jazz Culture). I reviewed each theme file to discover sub

categories (e.g., including listening for style, learning the lingo, and improvisation.), then further analyzed each subcategory and wrote drafts of each section. Sections were

gradually revised and merged into this document. At the time of this study I had several years of experience as a junior high school

and high school band director of which directing a jazz band, coaching a combo, and

teaching jazz improvisation comprised part of my teaching duties. I also had begun my second year of a teaching assistantship in jazz at [name suppressed] State University. The non-intervention protocol aided me in not influencing the learning culture of this ensemble, and threats to validity in terms of bias were identified with research memos written during and after each observation to aid in reporting my bias.

17

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education Winter 2008 No. 175

The audiotapes of rehearsals and interviews ensured trustworthiness of the field notes. Data from observations, interviews, and artifacts were triangulated to ensure further validity. I analyzed each data record for evidence of elements of the historic jazz culture, then presented my findings with a local director of jazz studies to determine whether I was, in fact, observing elements from the historical jazz culture. Research col- leagues aided with peer review of field notes of observations and interviews. I utilized an external audit by a qualitative researcher in which "an outside person examines the research process and product through 'auditing' your field notes, research journal, ana- lytic coding scheme, etc." (Glesne, 1999, p. 32). Member checks in this study occurred in the form of student participants and the director offering their comments and per- spectives upon review of the findings.

In the following sections I will portray a typical rehearsal which I have included to help offer a description and sense of the environment for the reader (Creswell, 1998), followed by the presentation of three themes which emerged throughout the data analy- sis process: (a) listening for style, (b) learning the lingo, and (c) improvisation.

A TYPICAL REHEARSAL At 6:20 a.m. only two students matriculate in the band room. A student with a glazed look on his face stares at the north wall in a rather trance-like state. The other student unlocks his saxophone case in a lethargic manner, puts his neck strap on, and begins to soak a reed.

The morning events appear to unfold in slow motion as the director, Ray Hutchinson, unlocks the doors to all of the rooms in the Fine Arts complex. Hutchinson moves in a speed contradictory to what I just witnessed with the students. With a plethora of keys dangling from his belt, Hutchinson moves at a brisk pace, considering the time of day. "That's one of the problems with being the first teacher here. I have to unlock all of the doors," he explains to me as he unlocks a percussion cabinet near to where I am sitting. Upon completing his rounds, Hutchinson goes into his office to check his answering machine. The bags under his eyelids become apparent as he furiously scribbles down mes- sages on a piece of scratch paper while taking messages left on the machine overnight.

It is now 6:25 a.m. and two more students filter into the band room. A couple of trumpet players now sit in their chairs buzzing on their mouthpieces. More students arrive; no one says much. They walk like pre-programmed zombies as they put their instrument cases down, take out their music, grab their instruments, and sit in their chairs. A trombonist plays through some of the current repertoire of the jazz band.

Hutchinson finishes checking his messages and plays a CD for the students to lis- ten to. The song is "88 Basie Street" from the CD by the same name of the Count Basie Band. This particular song is in the band's repertoire for their upcoming concert.

More students have arrived. I am amazed that within ten minutes the jazz band is nearly complete. A couple of band members assemble the drum set while another sets

18

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Goodrich Jazz Culture

up an ancient Fender Rhodes piano. Electrical tape and duct tape adorn the electric

piano hinting at years of transport to and from performances. Three students practice "88 Basie Street" while others play lip slurs and pedal tones to warm up. It is 6:30 a.m. and Hutchinson walks around the room talking to students, answering their questions, and finding out how they are doing. "What are we doing in marching band today?" asks a trombonist. "We are charting pages six through ten on the field today," replies Hutchinson. A student with an alto saxophone asks Hutchinson "Which field are we on? Can we be in the stadium today? Please?" Hutchinson responds, "What's wrong with our practice field? You can relax, we are at the stadium today."

At 6:32 a.m. Hutchinson begins the rehearsal with a blues in b-flat. Hutchinson counts off the rhythm section and they play a couple of choruses while Hutchinson tells the band to play "head number 2" out of an Aebersold play-along book. The band starts the head, or melody of the song, when the rhythm section gets to the third chorus. After

playing the head twice the band begins outlining the arpeggios of the chords in the blues. After three measures Hutchinson stops the jazz band and says, "You guys need to learn your mixolydian scales better. It's like a major scale, but with a lowered seventh. Let's run it slowly." He has the band run through an F mixolydian scale a few times, first with whole note values, then quarter notes, and finally eighth notes. Hutchinson counts off the jazz band again, and they continue outlining the arpeggios. This time the jazz band sounds much better. Hutchinson acknowledges the improvement with an

emphatic "Yes!" as they make it through a chorus without any mistakes. The jazz band plays the arpeggios for two choruses and they "nail it" the second

time. The rhythm section continues to play as Hutchinson motions for the rest of the band to quit playing. He points at the lead alto player, who takes the first solo. The stu- dent stays with the notes of the blues scale for the first several measures, and then ven- tures outside of the chord changes. Hutchinson immediately stops the band and tells him to play the same changes as the rhythm section. Hutchinson tells the student to

play the correct scales by himself. After the student plays the scales correctly Hutchinson

replies, "Now, doesn't that sound much better? Use those scales when you improvise." He then counts off the rhythm section, and now the student plays a solo that lines

up with the same harmony as the rhythm section. The lead alto finishes his solo and Hutchinson points to the lead tenor, who plays next. This process continues with appar- ently no predetermined solo order. After four students play solos Hutchinson yells to the jazz band to "Barn house." I am momentarily puzzled by this term until the entire band improvises at the same time. I quickly realize that I mis-interpreted Hutchinson's Canadian accent. He told the band to "burn house," indicating that everyone in the band will solo at the same time. After the jazz band "burns house" for two choruses the bari sax player takes a solo. Four students solo individually, then everyone plays at the same time. This process repeats until everyone has an opportunity to improvise a solo. The jazz band plays through "head number 2" and finishes the song. "Well, what do

you think?" Hutchinson asks the band. "Improvisation is where it's at. Keep practicing 19

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education Winter 2008 No. 175

those scales and arpeggios, okay?" he tells the jazz band. Hutchinson continues, "Get out '88 Basie Street.' I am going to play the recording for you. We're going to listen to the Basie band play this again. Listen for where they place their eighth notes in the groove. They swing better than anyone else. Listen to the style of the eighth note." The students quickly pull the song out of their folders and listen to the recording. While the music pipes through the sound system the drummer "air drums" to the song. Within a few measures the entire band is fingering along, mimicking the Basie band.

After the students listen to the recording Hutchinson tells them to play the last four measures of the song. The jazz band plays the four measures. Hutchinson tells them, "We're not swinging our parts like the Basie band does. This time sing your parts while the rhythm section plays." Hutchinson continues, "This time, exaggerate to the point where you think you will fall off of the beat." They play the four measures for a second time. Next, Hutchinson asks the lead trumpet player, lead trombone player, and the bass trombonist to play the last phrases of the song. They play through it twice, and Hutchinson is displeased with the intonation. "Guys, find the shelf," he tells them. The entire band now rehearses the last phrase. Hutchinson says, "You guys are starting to play it in tune, but now you're not releasing together." Hutchinson jokes with them, "Now let's play it from the top and here's the deal. You will get $500.00 for playing this song. There will be a $20.00 bonus every time the band releases together." The band plays through the song and the releases are much better.

According to the clock in the band room it is now 7:00 a.m. Hutchinson asks the band to pull out "A Night in Tunisia" from their folders. As the band takes the music out of their folders the drummer immediately starts playing an Afro-Cuban rhythm that is predominant in this chart. Hutchinson tells the band, "Before we play through this as a group we need to clean up some of the rhythms and articulations. Go into sectionals for a few minutes. All of the rooms are unlocked." The rhythm section remains in the band room while the other sections quickly scatter throughout the Fine Arts complex to work on their parts. Soon a myriad of sounds can be heard flowing out of several rooms as the section leaders drill their sections on "A Night in Tunisia." Approximately fifteen minutes pass before Hutchinson walks around the complex and tells everyone in the jazz band to return to the band room so they can run through the entire chart.

At 7:15 a.m. the band filters into the band room and they "noodle" on their instruments for approximately forty-five seconds before Hutchinson cuts them off. He explains to the students that Dizzy Gillespie wrote "A Night in Tunisia" on the bottom of a garbage can as he points to a picture of Dizzy Gillespie on the wall of the band room. Hutchinson counts off the rhythm section and they play by themselves to get the groove going first. Hutchinson lets them play for close to a minute before he counts off the rest of the band. He is immediately displeased and stops. He looks at the sax and brass sections and says, "Guys, what are you doing? You are not playing the same time as the rhythm section. You need to internalize the groove." Hutchinson asks the horn players to sing their parts while the rhythm section is playing. After a few repetitions, 20

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Goodrich Jazz Culture

he starts the band again. Hutchinson smiles this time, indicating he is happier with the time-feel. The band plays through the ensemble sections up to where the trumpet solo

begins. The trumpet soloist plays a couple of notes when Hutchinson cuts him off and tells the band "We're out of time. We'll get to the solo tomorrow. You need to be on the field in half an hour." It is 7:31 a.m. and the rehearsal is over. As the students get up to put their instruments and music away, the trumpeter improvises his solo a cappella. After the trumpeter finishes practicing his solo Hutchinson tells him, "Tomorrow I will

bring in ten CDs with 'A Night in Tunisia' on them and I will let you borrow them." "Awesome," replies the student who quickly puts his trumpet away. The jazz band scat- ters as they all prepare for marching band.

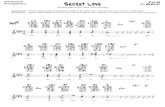

Listening for Style Historically, jazz musicians learned how to play jazz music through aural transmission.

Listening occurred at Crescent Valley High School in two ways: listening to recordings of professional jazz musicians and listening to each other. Hutchinson advocated listen-

ing to recordings before and during rehearsals. During the course of my observations Hutchinson always had jazz music playing in the background on the sound system as students entered the band room and warmed up on their instruments. Hutchinson

played music of current repertoire of the jazz band in addition to music in a similar

style (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Recordings played for the Crescent Valley High School Jazz I:

Hutchinson referred to these listening examples and to jazz artists during rehearsals to help the students with style and improvisation. He guided the students through the

listening process and often offered comments ranging from, "Listen to how the Basie band plays behind the beat" to "Listen to how this player leaves space in their solo. Less

21

1 . 88 Basie Street Sammy Nestico, composer. Originally performed by Count Basie.

I. Hayburner Sammy Nestico, composer. Originally performed by Count Basie.

5. A Night in Tunisia John Birks Gillespie, composer; Sammy Nestico, arranger. A jazz standard originally performed by John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie.

i. I've Got Rhythm George and Ira Gershwin, composers; Rob McConnell, arranger. Performed by Rob McConnell and the Boss Brass on the CD "All in Good Time."

>. You've Got It Tom Garvin, composer. Performed by Maynard Ferguson and Big Bop Nouveau on the CD "One More Trip to Birdland."

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education Winter 2008 No. 175

is more. Leave more space in your solos." In addition to guiding the students through the listening process in rehearsals, Hutchinson also stressed the importance of students

listening to recordings on their own. Following one rehearsal he gave a trumpet soloist ten recordings of "A Night in Tunisia" to help the student with his improvised solo. These recordings included versions by legendary trumpet players Arturo Sandoval, Dizzy Gillespie, Kenny Dorham, and Clifford Brown. Hutchinson hoped that by listen- ing to professionals the students will learn and absorb musical ideas that will aid them in their improvisation and also help them to play with the correct style.

In addition to advocating listening to professional recordings for style and musical ideas, Hutchinson stressed the importance of the students listening to each other in rehearsal. He frequently used metaphors to direct student listening. In one rehearsal he told the jazz band to "... listen to the lead trumpet player. He's the leader of the house." In another rehearsal Hutchinson called out, "Articulations from the bass bone are the foundation. The lead trumpet is the roof. If its right, we'll have a mansion instead of a bungalow."

Jazz articulations comprise a very important component of performing big band jazz music in the correct style and differ substantially from those used in other styles and genres. These articulations have their own language. When playing an accented quarter note in jazz, a performer says "dot" when they articulate the note. An eighth note is "dit" and successive eighth notes can be "doo-ah doo-ah." The language of jazz articulations varies depending upon the length of the note and whether it has an accent or not. Hutchinson often found different ways to explain jazz articulations to the band in rehearsals. For example, he told the band. "Instead of saying dot, you need to say d-o-u-g-h-t to make the quarter notes longer." Students adjusted their playing accord- ingly. Hutchinson maintained high expectations for ending notes and phrases together. To aid in this, he often had the jazz band sing their parts with the rhythm section accompanying. Jason, lead trumpet, commented that he thought this was an excellent way to rehearse.

Learning the Lingo Jazz musicians often use their own lingo when speaking with each other, and Hutchinson used this lingo as part of his teaching vocabulary to assist the jazz ensemble in playing the appropriate correct style and to obtain a better feel for the idiom. When Hutchinson sensed the jazz band could swing harder or play with a better time-feel, he told the group, "Let the groove get established," or "Guys, we need to groove on this chart," rather than simply saying "Swing." Hutchinson would tell the group to "play it greasy, man," when the ensemble needed to lay back on the beat and when he wanted the jazz band to improve their intonation he instructed them to "find the shelf." Melody is referred to as "the head" of a song, a term utilized by Hutchinson and the group along with "chart," a common name for sheet music in the jazz world.

22

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Goodrich Jazz Culture

Although it appeared to me during the course of my observations that the students understood the jazz lingo used by Hutchinson, I was curious, however, if they really com-

prehended what Hutchinson was saying. Linda, the lead trombone player, said the lingo was "... kind of like a visualization. My freshman year he gave us 'greasy,' as, like, you should play it like the grease rolling off it. So, okay, lay back." Jason commented, "I under- stand it. I didn't quite get it at first, but I don't even think about it now." Eric pointed out that jazz band "... was all about Basie. It comes down to playing greasy, man."

Improvisation Hutchinson attended to improvisation - the original mode for performing this music - when he rehearsed the jazz band. During the course of my observations every rehearsal

began with improvisation. The jazz band improvised to a blues, in the key of B flat or F, at various tempi and in various styles (e.g., swing feel, bossa nova, rock). The blues

began with the ensemble playing the head, or melody, followed by the students outlin-

ing the chords for either one or two choruses. Upon completion of this regimen the students began soloing. If a student had difficulty improvising to the chord changes, or had problems with musical ideas, Hutchinson stopped the group immediately and worked with the student. In one of the rehearsals that I observed, the lead alto saxo-

phonist, Alex, had problems hearing the IV chord. Hutchinson told the student to

begin his solo again, and every time the IV chord occurred Hutchinson held up four

fingers and yelled "four" until it was clear that Alex had learned where the IV chord occurs in the structure of the blues. In another rehearsal, the second trumpet player, Gottfried, did not play a solo that went with the chord changes. Hutchinson quickly stopped the band and explained the importance of emphasizing the thirds and sevenths of the chords for establishing proper harmonic rhythm. Hutchinson asked Gottfried to

play the thirds and sevenths of the chords while the rhythm section accompanied him. Gottfried played through the form three more times, followed by another attempt at

improvisation. This time Gottfried played a solo that fit the chord changes and both he and Hutchinson appeared quite pleased.

In addition to teaching harmonic basics of improvisation, Hutchinson also stressed the importance of motivic development in solos. Hutchinson often gave the students

specific practicing directives and strategies during rehearsals. An example of a practicing directive included teaching the students how to practice scales used in the blues over the full ranges of their instruments. He explained that, "Long notes can create tension. Now, everyone try it ... think about developing your solo." The students quickly tried his suggestion in their solos and they seemed pleased with the results.

Although insistent with regards to developing improvising skills, Hutchinson sym- pathized with individual levels of ability among the students. He related in an interview

remembering feeling intimidated when first learning to improvise, and felt he could

"put [himself] in their shoes." He noted that when he saw a wide-eyed "fish look" on

23

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education Winter 2008 No. 175

a student's face in a rehearsal, he would have the band "burn house," or play a solo together until the student gained enough confidence to improvise alone.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS If a student participates in a school jazz ensemble, are they really performing jazz music? Historically, the jazz culture contained many nonmusical elements not suitable for a high school setting including drug abuse, drug dealing, crime, prostitution, and gam- bling in addition to more desirable elements including lingo, listening, and improvisa- tion which can result in negative connotations today with music educators (Johnson in Cooke, 2002). Utilizing the historic jazz culture, however, allows us to "think about the present reflexively. And with an understanding of the past, the contours of the present suddenly become clearer" (Ohnuki-Tierney, 1990, p. 1). Although not all jazz musicians subscribed and practiced these undesirable characteristics, these elements did comprise the fabric of the historic jazz culture. With the introduction of jazz music into the schools, jazz lost some of its aural traditions and expressive vocal language. It is the role of the director to choose which elements of the jazz culture to introduce to the jazz ensemble. In this study, the director, Ray Hutchinson, served this role via acting as a filter for deciding which elements to include in his teaching of the ensemble.

Hutchinson utilized the following elements from the historic jazz culture: listening for style, lingo, and improvisation. Introducing elements of the historic jazz culture can aid in providing a real jazz experience for the students. Ake (1998) states that students and directors need to be open to new experiences in jazz. Introducing "old school" concepts including listening for style, lingo, and improvisation can open up new ways of thinking, listening, and performing for todays high school students and provide a deeper connection to this important era in American history. If students and their directors are open to these new experiences then students who play in a high school jazz band are opening themselves up to the possibility of transcending the performance of mere notes and participating in the jazz experience. Arnold (1979) states that "perhaps as music educators we need to go beyond reading notes from the page and teach our students various cultural elements of jazz music so they can gain a better understanding of the music" (p. 7).

How did Hutchinson filter and incorporate these elements into a high school jazz ensemble? During the course of this study he taught the students to delve deeper into the music, to go beyond playing only the correct notes, rhythms, and articulations. Elliott (1995) maintains that:

The kinds of musical knowing required to listen competently, proficiently, or expertly for the works of a given musical practice are the same kinds of knowing required to make the music of that practice: procedural, formal, informal, impressionistic, and supervisory musical knowledge (p. 96).

24

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Goodrich Jazz Culture

Hutchinson teaches the students procedural knowledge (e.g., fingerings), formal learn-

ing (e.g., rhythms, articulations), informal learning (e.g., lingo, advocating student

listening, modeling of sounds and style), impressionistic (e.g., use of analogies, imag- ery), and supervisory musical knowledge (e.g., guided listening in rehearsals). Further, Elliott (1995) states that solutions to realistic musical problems are solved in relation to standards (musical notation, concert band procedural knowledge); traditions (band culture and jazz culture); history (Hutchinson teaches jazz history - "This is how the Basie band played this" and the lore of musical context (lingo; analogies; teaching the students where jazz was originally performed - "Dizzy Gillespie wrote this on the bot- tom of a garbage can") (p. 64).

The students in the Crescent Valley High School Jazz Band I learn and perform the music with elements similar to how jazz musicians learned the music in the historic jazz culture, without the negative cultural traits. Jazz music "constrains, historically, the behavior of those who would join themselves to the jazz tradition" (Horowitz and

Nanry, 1975, p. 25). Does a hierarchy exist for filtered elements of the historic jazz culture? Is pres-

ervation of lingo really as important as the aural foundations of improvisation or the

emphasis placed on individual musicianship (as opposed to ensemble alone)? Stebbins (1964) discovered that jazz musicians form their own community, of which lingo is a crucial component. Marsalis (2000) adds that the use of jazz lingo is critical when

teaching this music. If lingo is used, however, is there a potential for it to be discon- nected from the jazz culture? Only if it is not first introduced within the context of

rehearsing and performing the music. Hutchinson transforms lingo into an authentic

jazz rehearsal practice to focus and enhance listening skills among the students in rehearsals. Further, he utilizes lingo in conjunction with non-jazz cultural teaching elements including metaphors, analogy, and imagery, making it more accessible for his students. For example, when guiding the students to listen for improved intona- tion, Hutchinson often told them to "put the notes on the shelf." For problems with time-feel in rehearsals he would remark "It's gotta groove. Listen. Its gotta get into the

groove." In turn, his students used the lingo when they spoke in interviews (e.g., Eric, "It was all Basie, man"). By doing so, Hutchinson places himself and the students into the realm of creating real jazz music and helps the students connect to the oral tradition of jazz music.

Listening comprises a vital component of the jazz curriculum at Crescent Valley High School. Hutchinson guides the students through the listening process to teach the students to listen to each other and to develop their listening skills. Alperson (1988) recommends that one should "listen to live and recorded performances" in order "to learn the 'language' of the style" (p. 46). Hutchinson exposes the students to a vast

array of jazz music the moment they enter the band room with recordings of jazz music either in the band's current repertoire for a performance or jazz music in a similar style. Ferriano (1974) discovered in his survey of music educators that students emulated pro-

25

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Bulletin of the Council for Reseorch in Music Education Winter 2008 No. 175

fessional jazz musicians in part through listening to recordings of professionals. During this study the Crescent Valley Jazz Band I rehearsed and performed "classics" of the jazz repertoire including Count Basie and his band, a practice advocated by Williams and Richards (1988). Hutchinson pays attention to rehearsal details which Elliott (1988) asserts that uninhibited actions, or time-feel in jazz, is based upon structure, perfor- mance, and the experienced listener. Hutchinson sets up the jazz band with high expec- tations for levels of performance and teaching and/or creating experienced listeners.

Having the students improvise in the jazz band helps connect them to the aural tradition of learning and performing jazz music. Mack (1993) discovered that a stu- dents ability to improvise combined with a directors encouragement contributes to the success of a jazz program. Hutchinson stresses the importance of hearing the chord

changes and playing the correct scales/note choices over the changes. Improvising helps the students develop aural skills. Pressing (1998) notes that improvisers learn from

"working with a teacher in a directed situation" (Pressing in Kenny & Gellrich, 2002, p. 126). Although Hutchinson does teach improvisation, it is a synthesis of "old school" and modern jazz methods, e.g., the chord/scale approach, a common method today for teaching and learning improvisation. Payne (1973) found that the most common method for teaching improvisation included guided listening and playing using chordal and blues approaches and May (2003) recommends that instruction in jazz improvisa- tion include teaching of jazz scales and chords.

During the course of this study I never observed Hutchinson improvise in rehears- als. Although improvising is taught, I found the level of improvising lower than the over- all quality of the ensemble. Teaching improvisation to all of the students is an excellent way to develop their ears, but the sixty-minute rehearsal time did not seem sufficient to both rehearse the band and work with soloists to develop their playing to a higher level. The jazz lab emphasizes improvising, but also includes students who could not make the top two bands. Further, Hutchinson reports that only 40 to 50 percent of the students in the top bands enrolled in the lab class. The addition of a jazz combo may allow the students who are serious about improvising to develop their skills to a higher level. The small group would allow everyone more time to work with individual students.

If connecting to the aural/oral traditions of jazz music is so important, why are not more directors doing this? Jazz bands in the public schools are based out of the concert band tradition. Although listening skills are taught in the concert band tradition, it is still primarily a visual based music where emphasis is placed upon reading music. Johnson (2002) notes that we live in a vision-based society and that "ocularcentrism . . . traps us in a particular regime [making] vision highly appropriate to the dominant epistemology of the modern epoch" (Johnson in Cooke, p. 101). As a result, argues Johnson, Jazz music, "is less comfortable than conventional art music to the dominant episteme" (2002, p. 100). Music educators untrained in improvisation are often uncomfortable with teaching this form of music. Hutchinson recognizes this dilemma and has taken it upon himself to learn and improve his improvisation and listening skills.

26

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Goodrich Jazz Culture

Expectations of the listener are another factor. Elliott (1988) discusses listener's

expectations in music where harmonic patterns are the norm and improvisations are the deviations. This helps to explain why many jazz bands excel at playing the correct notes but few have outstanding improvisers - teachers formed in this mold with concert band

procedural knowledge - and Hutchinson, a self-proclaimed "jazz experimentalist" pos- sesses a musical background with primarily classical training. Hutchinson has evolved

beyond his training and sets up an environment where improvisation is the norm. Hutchinson, a successful high school band director, understands the jazz idiom, the

lingo, the aural tradition, and the performance skills necessary for success. Although the

participants at Tanglewood nearly forty years ago recommended that "Teachers must be trained and retrained and understand the specifics of a multiplicity of music . . . (includ- ing) . . . various mutations of jazz" (Choate, 1968, p. 135), Hutchinson self-selected the

experiences that enabled him success. His formal music training did not include jazz music as part of the required curriculum in his education.

The directors teaching in this particular situation worked. But what about music educators or music education students who are not jazz performers or have not had similar experiences? What kinds of experiences do music students need to have in order to be prepared to teach jazz music in the schools? How do we prepare music education students to direct jazz bands in the public schools? Being a jazz performer certainly helps, as there is no substitute for performing the music. Even secondary instrument

experiences can be valuable (e.g., flutist or clarinetist doubling on a saxophone). Jazz pedagogy, jazz ensemble rehearsal techniques, jazz methods, or playing in a jazz lab band can aid students in becoming jazz educators. Balfour (1988) conducted a survey of California music educators and found that a majority of respondents believed that more attention needed to be given to jazz pedagogy and curriculum reform in the

preparation of music educators. Fisher (1981) suggests the four most important courses for the preparation of music education majors based upon a survey he conducted are

Jazz Band Methods, Jazz Improvisation, and Jazz History and Literature. Studying jazz music can also complement academic classes in the music curriculum (Dobbins, 1988). In the very least listening to jazz recordings and attending live jazz performances will

certainly help. Within the process of filtering out the undesirable elements of the historic jazz

culture, Hutchinson utilized these filtered elements in conjunction with the music

making, keeping the musical experience at the core of the students' experience. This aided Hutchinson in deciding which elements to filter and utilize with his ensemble.

Although Hutchinson related that he was "forced to play jazz as a classical musician" at age 16, he has discovered a way to teach authentic jazz music in an authentic jazz learning context, without the potential negative sociocultural contexts of jazz music. Hutchinson kept the musical experience at the core of the learning experience.

Over the last one hundred years jazz has made the transition from dance hall to classroom. The school of jazz was originally held in a nightclub and the bell rang for

27

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education Winter 2008 No. 175

class to begin at 12:00 a.m. Generations of jazz musicians crafted their art listening to their idols playing in these clubs. The jazz musician spent time wearing out records as he/she copied their favorite players note for note. In the middle of the twentieth century jazz music invaded band rooms at a rapid rate. With this invasion came a new style of learning how to play this music. Sheet music became the norm and a whole new jazz language evolved, a language spoken by articulations, releases, and actually having to read music.

The Crescent Valley High School Jazz Band I is a syncretization of the history of jazz. Hutchinson stressed listening to recordings and learning how this music was played from the masters. He taught the students how to listen to not only themselves but also to each other. When the bell rings at Crescent Valley High School, the school of jazz is definitely in session.

REFERENCES Alce, D.A. (1998). Being jazz: Identities and communities. Dissertation Abstracts International, 54

(11), 4001. (UMI No. 9912620)

Alperson, P. (1988). Aristotle on jazz: Philosophical reflections on jazz and jazz education. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 95, 40-6 1 .

Arnold, R. (1979). Jazz - a purely American cultural heritage. Jazz Educators Journal, 13 (4), 7-8. Balfour, W.H. (1988). An analysis of the status of jazz education in the preparation of music educa-

tors in selected California universities. Dissertation Abstracts International, 49 (12), 3651. (UMI No. 8901736)

Bash, L. (1983). The effectiveness of three instructional methods on the acquisition of jazz improvi- sation skills. Dissertation Abstracts International, 44(07), 2079. (UMI No. 8325043)

Beanie, J. (1964). Other cultures: Aims, methods, and achievements in social anthropology. London: Cohen and West.

Berliner, P. (1994). Thinking in jazz. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. Carlson, W.R. (1980). A procedure for teaching jazz improvisation based on an analysis of the per-

formance practice of three major jazz trumpet players: Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, and Miles Davis. Dissertation Abstracts International, 42 (03), 1042. (UMI No: 81 18663)

Choate, R.A. Ed. (1968). Documentary report of the Tanglewood symposium. Washington, D.C., Music Educators National Conference.

Creswell, J.W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA. SAGE Publications.

DiGirolamo, O. (1974). A guide for the development of improvisational experience through the study of selected music for the high school instrumentalist. Dissertation Abstracts International, 35 (10), 6749. (UMI No: 7507832).

Dobbins, B. (1988). Jazz and academia: Street music in the ivory tower. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 96, 30-4 1 .

Elliott, D.J. (1988). Structure and feeling in jazz: Rethinking philosophical foundations. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 95, 14-39.

Elliott, D.J. (1995). Music matters: A new philosophy of music education. New York: Oxford University Press.

28

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Goodrich Jazz Culture

Ferriano, F. (1974). A study of the school jazz ensemble in American music education. Dissertation Abstracts International, 35 (10), 6359. (UMI No. 7507833)

Fisher , L.F. (1981). The rationale for and development of jazz courses for the college music educa- tion curriculum. Dissertation Abstracts International, 42(07), 3051. (UMI No. 8129159)

Flack, M.A. (2004). The effectiveness of Aebersold play-along recordings for gaining proficiency in jazz improvisation. Dissertation Abstracts International, 55 (06), 2019. (UMI No: Not Available)

Glesne, C. (1999). Becoming qualitative researchers (2nd ed.). New York: Longman. Goodrich, A. (2001). Jazz in historically black colleges. Jazz Educators Journal, 34 (3), 54-58. Gottleib, R. (Ed). (1996). Reading jazz: A gathering of autobiography, reportage, and criticism from

1919 to now. New York: Vintage books.

Hall, M.E. (1969). How we hope to foster jazz. Music Educators Journal, 55 (7), 44-48.

Horowitz, L, & Nanry, C. (1975). Ideologies and theories about American jazz. Journal of Jazz Studies, 2,24-41.

Johnson, A. G. (1995). The Blackwell dictionary of sociology: A user 's guide to sociological language. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Reference.

Johnson, B. (2002). Jazz as cultural practice in Cooke, M. & Horn, D. (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to jazz (pp. 96-1 13). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Leavell, B. (1996). Making the change: Middle school band students' perspectives on the learning of mus i cal -tech ni cal skills in jazz performance. Dissertation Abstracts International, 57 (01), 2931. (UMI No. 9638480)

Mack, K.D. (1993). The status of jazz programs in selected secondary schools of Indiana. Dissertation Abstracts International, 54(03), 856. (UMI No. 9319884).

Madura, P.D. (1996). Relationships among vocal jazz improvisation achievement, jazz theory knowledge, imitative ability, musical experience, creativity, and gender. Journal of Research in Music Education, 44 (03), 252-267.

Mark, M. (1987). The acceptance of jazz in the music education curriculum: A model for interpret- ing historical process. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 92, 15-21.

Marsalis, W. (2000). Jazz education in the new millenium. Jazz Educators Journal, 33, No. 2, 46-53.

Maxwell, J.A. (1996). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

May, L.F. (2003). Factors and abilities influencing achievement in instrumental jazz improvisation. Journal of Research in Music Education, 51 (3), 245-259.

Moorman, D.L. (1984). An analytic study of jazz improvisation with suggestions for performance (theory). Dissertation Abstracts International, 45 (07), 2023. (UMI No: 8421463)

Murphy, J., & Sullivan, G. (1968). Music in American society. Washington, D.C.: Music Educators National Conference.

Ohnuki-Tierney, E. (1990). Introduction: The historicization of anthropology in Ohnuki-Tierney, E. (Ed.), Culture through time: Anthropological approaches (pp. 1-25). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Ortner, S.B. (1990). Patterns of history: Cultural schemas in the foundings of Sherpa religious institutions in Ohnuki-Tierney, E. (Ed.), Culture through time: Anthropological approaches (pp. 57-93). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Patton, M.Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA. SAGE Publications.

Payne, J.R. (1973). Jazz education in the secondary schools of Louisiana: Implications for teacher education. Dissertation Abstracts International, 34-06A, 3038.

29

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education Winter 2008 No. 175

Pressing, J. (1998). Improvisation: Methods and models. In J. Sloboda (Ed.), Generative processes in music: The psychology of performance, improvisation, and composition (pp. 129-178). Clarendon: Oxford Publishing.

Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. New York: Oxford University Press.

Scott, A. (1973). Jazz education, man. Washington, D.C., American International Publishers.

Shapiro, N., & Hentoff, N. (1955). Hear me talkin to ya. New York, Dover Publications. Stebbins, R.A. (1964). The jazz community: The sociology of a musical subculture. Dissertation

Abstracts International, 26(10), 6225. Suber, C. (1976). Jazz Education. The encyclopedia of jazz in the seventies. New York, Horizon Press.

Williams, M., & Richards, D. (1988). A historical and critical survey of recent pedagogical materials for the teaching and learning of jazz. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 96, 1-6.

30

This content downloaded from 129.78.139.29 on Mon, 11 May 2015 08:12:56 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions