Egipto 123

Transcript of Egipto 123

centuriespast:

Egypt (made)

1400BC-400BC (made)

Protective amulets taking the shape of gods, animals or various symbols were often placed in tombs. In Ancient Egypt, gold was the colour of divinity. Taweret was the goddess of maternity and childbirth, who protected women and children. She was depicted as a combination of a hippopotamus, a crocodile and a lion, all of these animals were fierce when protecting their young. Amulets of Taweret were popular, used by expectant mothers. In the Book of the Dead, Taweret was also seen as a goddess who guided the dead into the afterlife. Many of the deities relating to birth also appear in the undeworld to help with the rebirth of the souls into their life after death.

The Victoria and Albert Museum

sans-merci:

Falcon Shaped Horus

ca. 1070-525 BC (Third Intermediate-Late Period)

The Walters Art Museum

The falcon god Horus represented the sky and was also associated with kingship from the late 4th millennium. This small falcon figure is made from gold and has a silver double-crown (which stands for Upper and Lower Egypt) attached.

artpedia:

Seated Statue of Hatshepsut, 1473–1458 B.C.Indurated limestone and paint

From the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC:

Hatshepsut, the most successful of several female rulers of ancient Egypt, declared herself king sometime between years 2 and 7 of the reign of her stepson and nephew, Thutmose III. She adopted the full titulary of a pharaoh, including the throne name Maatkare, which is the name most frequently found on her monuments. Her throne

name and her personal name, Hatshepsut, are both written in cartouches making them easy to recognize. This life-size statue shows Hatshepsut in the ceremonial attire of an Egyptian pharaoh, traditionally a man’s role. In spite of the masculine dress, the statue has a distinctly feminine air, unlike most other representations of Hatshepsut as ruler. Even the kingly titles on the sides of the throne are feminized to read “the Perfect Goddess, Lady of the Two Lands (Upper and Lower Egypt)” and “Bodily Daughter of Re (the sun god).”Traces of blue pigment are visible in some of the hieroglyphs on the front of the statue and a small fragment on the back of the head shows that the pleats of the nemes headcloth were originally painted with alternating blue and yellow.

Imhotep (c. 2667-2648 BCE)

Imhotep was chief architect to the Egyptian pharaoh and was responsible for the Step Pyramid. During his lifetime he was often represented as a priest and was considered a man of great learning. He does not seem to have practised as a doctor during his life, but medical texts describing the diagnosis and treatment of over 200 diseases were attributed to him. After his death Imhotep began to be worshipped as a god, and miracles were reported at his shrines.

When the Greeks conquered Egypt in 332 BCE, they saw many similarities between Imhotep and their medical god Asklepios and continued to build temples to him.

In 1930 a papyrus named after the American collector Edwin Smith was translated. Written about 1700 BCE, it described Egyptian surgical and medical practice, with little of the magical content that was normally associated with Egyptian medicine. The work described ideas at least a thousand years old, which have been attributed to Imhotep. However, as with Hippocrates, it is not clear whether Imhotep himself, or his students or followers, wrote the text.

Previous Next

ancientpeoples:

Hathor is the Ancient Egyptian goddess who personifies the principles of love, beauty, music, dance, motherhood and joy. She is one of the most important and popular deities throughout the history of Ancient Egypt. Hathor was worshiped by Royalty and non royals alike in whose tombs she is depicted as “Mistress of the West” welcoming the dead into the next life. In other roles she was a goddess of music, dance, foreign lands and fertility who helped women in childbirth, as well as the patron goddess of miners.

The cult of Hathor pre-dates the historical period and the roots of devotion to her are, therefore, difficult to trace, though it may be a development of predynastic cults who venerated the fertility, and nature in general, represented by cows.

Hathor is commonly depicted as a cow goddess with head horns in which is set a sun disk with Uraeus. Twin feathers are also sometimes shown in later periods as well as a menat necklace. Hathor may be the cow goddess who is depicted from an early date on the Narmer Palette and on a stone urn dating from the 1st dynasty that suggests a role as sky-goddess and a relationship to Horus who, as a sun god, is “housed” in her.

The Ancient Greeks identified Hathor with the goddess Aphrodite and the Romans as Venus.

As Hathor’s cult developed from prehistoric cow cults it is not possible to say conclusively where devotion to her first took place. Dendera in Upper Egypt was a significant early site where she was worshiped as “Mistress of Dendera”. From the Old Kingdom era she had cult sites in Meir and Kusae with the Giza-Saqqara area perhaps being the centre of devotion. At the start of the first Intermediate period Dendera appears to have become the main cult site where she was considered to be the mother as well as the consort of “Horus of Edfu”.Deir el-Bahri, on the west bank of Thebes, was also an important site of Hathor that developed from a pre-existing cow cult.

Temples (and chapels) dedicated to Hathor:

The Temple of Hathor and Ma’at at Deir el-Medina, West Bank, Luxor. The Temple of Hathor at Philae Island, Aswan. The Hathor Chapel at the Mortuary Temple of Queen Hatshepsut. West Bank,

Luxor.

ancientpeoples:

Bronze mirror decorated with two falcons

From EgyptMiddle Kingdom (about 2040-1750 BC)

The form of the ancient Egyptian mirror changed little from its first appearance in the Old Kingdom (about 2613-2160 BC) and consisted of a polished disc of bronze or copper, attached to a handle. The reflective surface was interpreted as the sun disc, because of its shape and shiny qualities. The falcons on this example might represent the sun-god Re.

The handle of the mirror was of wood, metal or ivory. This example has been made to appear as if it has been plaited. A papyrus stalk, or the figure of Hathor were also common. The handle could also be surmounted by the head of Hathor. She was particularly associated with the mirror, which had connotations of sexuality and rebirth.

The same theme can be seen in the handles in the form of nude female figures. They sometimes have their arms outstretched to hold the crosspiece below the disc. Adults were seldom shown without clothes, as this could be interpreted as a lack of status. One exception was dancers, whose erotic dances in tomb scenes, like the figures on the mirrors, were associated with rebirth in the Afterlife.

collective-history:

Statuette of Amun, Third Intermediate Period, Dynasty 22, ca. 945–715 B.C.

The god Amun (“the hidden one”) first came into prominence at the beginning of the Middle Kingdom. From the New Kingdom onward, Amun was arguably the most important god in the Egyptian pantheon. As a creator god, Amun is most often identified as Amun-Re (in the typical Egyptian blending of deities, Amun is combined with Re, the principal solar god). His main sanctuary was the immense temple complex at Karnak on the east bank of the Nile at the southern edge of modern Luxor.

In this small representation, Amun stands in the traditional pose with the left leg forward. He is identified by his characteristic flat-topped crown, which originally supported two tall gold feathers, now missing. He wears the gods’ braided beard with a curled tip and carries an ankh (“life”) emblem in his left hand and a scimitar across his chest. On pylons and temple walls of the New Kingdom, Amun-Re is often depicted presenting a scimitar to the king, thus conferring on him military victory.

This statuette, cast in solid gold, is an extremely rare example of the sculpture made of precious materials that, according to ancient descriptions, filled the sanctuaries of temples. The figure could have been mounted on top of a ceremonial scepter or standard. If traces on the back are rightly interpreted, it was fitted with a loop that could have been employed for attachment, even possibly to an elaborate necklace. For the Egyptians, the color of gold and the sheen of its surface were associated with the sun, and the skin of gods was supposed to be made of gold.

ancientpeoples:

Model Faience wig for a statue

Said to be from Thebes, Egypt18th-19th Dynasties, about 1350-1250 BC

This wig was probably one of a number of faience and glass elements placed on a (probably wooden) royal statue. It is made of a particularly glossy type of faience, one that was very common around the time of the Amarna Period (1390-1327 BC). However, the round wig is more commonly seen on royal statues of the Nineteenth Dynasty (about 1295-1186 BC).

Set into the wig is a representation of a headband, with attached streamers of gold inlaid with red and blue glass as substitutes for carnelian and turquoise. On the end of one streamer is a cobra. A hole in the top of the wig may indicate a place for a crown, while

another hole in the brow is for the attachment of a uraeus. A layer of plaster on the inside probably indicates how the wig was attached to the statue.

that1randomweirdchick:

Info from http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/ankh.htm

The Ancient Ankh, Symbol of Lifeby Jimmy Dunn writing as Taylor Ray Ellison

The Ankh was, for the ancient Egyptians, the symbol (the actual Hieroglyphic sign) of life but it is an enduring icon that remains with us even today as a Christian cross. It is one of the most potent symbols represented in Egyptian art, often forming a part of decorative motifs.

The ankh seems at least to be an evolved form of, or associated with the Egyptian glyph for magical protection, sa. However, what the sign itself represents is often disputed. For example, Sir Alan Gardiner thought that it showed a sandal strap with the loop at the top forming the strap, but if so, the symbolism is obscure and so his theory has found little real favor early on. However, this interpretation seems to have received some acceptance among modern writers. It would seem that the ancient Egyptians called that part of the sandal ‘nkh (exact pronunciation unknown). Because this word was composed of the same consonants as the word “life”, the sign to represent that particular part of the sandal, was also used to write the word “life”.

Another theory holds that the ankh was symbolic of the sunrise, with the loop representing the Sun rising above the horizon, which is represented by the crossbar. The vertical section below the crossbar would then be the path of the sun.

Wolfhart Westendorf felt it was associated with the tyet emblem, or the “knot of Isis”. He thought both were ties for ceremonial girdles. Winfried Barta connected the ankh with the royal cartouche in which the king’s name was written, while others have even identified it as a penis sheath. The presence of a design resembling a pubic triangle on one ankh of the New kingdom

seems to allow for the idea that the sign may be a specifically sexual symbol. In fact, guides in Egypt today like to tell tourists that the circle at the top represents the female sexual organ, while the stump at the bottom the male organ and the crossed line, the children of the union. However, while this interpretation may have a long tradition, there is no scholarly research that would suggest such an exact meaning.

The ankh, on some temple walls in Upper Egypt, could also symbolize water in rituals of purification. Here, the king would stand between two gods, one of whom was usually Thoth, as they poured over him a stream of libations represented by ankhs.

The ancient gods of Egypt are often depicted as carrying ankh signs. We find Anqet, Ptah, Satet, Sobek, Tefnut, Osiris, Ra, Isis, Hathor, Anibus and many other gods often holding the ankh sign, along with a scepter, and in various tomb and temple reliefs, placing it in front of the king’s face to symbolize the breath of eternal life. During the Amarna period, the ankh sign was depicted being offered to Akhenaten and Nefertiti by the hands at the end of the rays descending from the sun disk, Aten. Therefore, the ankh sign is not only a symbol of worldly life, but of life in the netherworld. Therefore, we also find the dead being referred to as ankhu, and a term for a sarcophagus was neb-ankh, meaning possessor of life.

It is at least interesting that the ankh word was used for mirrors from at least the Middle Kingdom onward, and that indeed, many mirrors were shaped in the form of an ankh sign. Life and death mirror each other, and in any number of ancient religions, mirrors were used for purposes of divination.

In fact, the ankh sign in ancient Egypt seems to have transcended illiteracy, being comprehensible to even those who could not read. Hence, we even find it as a craftsman’s mark on pottery vessels.

As the Christian era eclipsed Egypt’s pharaonic pagan religion, the sign was adapted by the Coptic church as their unique form of a cross, known as the crux ansata.

King Akhenaten and his wife Nefertiti praying to the sun-god Aten who provided his rays to the king and the queen. The sun rays end up with hands holding the key of life offering it to the royal family.

Akhenaten and Nefertiti changed Egypt’s official religion to devotion to Aten, angering many powerful priests of the traditional multi-god religion. The sun-disk, during the Amarna period usually depicted with sun rays ending in hands that offer the sign of life (ankh) to the king and his family. The Aten was first regarded as a god during the 18th Dynasty and gained popularity under Amenhotep III (Akhenaten). Akhenaten abolished all other gods in favour of the Aten, and composed royal names and titles for his god. His “monotheistic” Aten-veneration was abandoned after his death.

This alabaster carving is from the tomb of Akhenaten.

09/12

Abren las tumbas de los toros sagrados en Egipto

Representaban al dios Apis de la fertilidad egipcia cuya veneración nació en el siglo VII a.C. y se extendió catorce siglos

Las tumbas en las que eran sepultadas las momias de los toros sagrados, que representaban al dios Apis en la tierra de los faraones egipcios, volvieron a abrirse al mundo hoy después de un proceso de restauración de diez años.En el complejo arqueológico del Serapeum, ubicado en la ribera occidental del Nilo, cerca de la pirámide de Saqara y a unos 25 kilómetros al suroeste de El Cairo, desde un total de 24 nichos con enormes sarcófagos de granito.Un paseo por este lugar tenebroso permite observar los gigantes ataúdes de color negro, cada uno de los cuales pesa 65 toneladas y mide ocho metros de largo y cuatro de ancho.Muchos de estos sarcófagos están cerrados con losas de la misma piedra, mientras que los suelos originales se pueden entrever por debajo de los pasillos que combinan suelos

de madera con espacios de cristal iluminados.No hay ni rastro en el recinto de las momias de los toros sagrados que albergaban las tumbas, donde en el pasado solo se encontró un ejemplar de estas figuras.El Serapeum es un gran complejo funerario que comprende pasillos de 170 metros de largo y que fue cerrado en 2002 para ser sometido a trabajos de reparación aprobados dos años después.En el sitio, descubierto en 1850 por el arqueólogo francés Auguste Mariette, se enterraban las momias de toros que representaban a Apis, el dios de la fertilidad, cuya veneración comenzó en el siglo VII a.C. y se extendió hasta el periodo grecorromano durante más de catorce siglos.El culto del toro Apis estuvo ligado al de Ptah, el dios principal de Menfis, la antigua capital de Egipto que tuvo gran importancia estratégica, histórica y religiosa durante la época faraónica y cuya área alberga también las conocidas pirámides de Guiza.Considerado un animal sagrado y adorado en vida, Apis era enterrado a su muerte en el Serapeum con todos los honores y luego se elegía a uno nuevo.Además de ser un complejo funerario, el Serapeum comprendía edificios destinados a los sacerdotes, albergues para los peregrinos y un santuario dedicado a Anubis, el dios con cabeza de chacal considerado protector de los muertos.

TEAVISA

ancientpeoples:

Amulet in the Form of a Ba as Human-Headed Bird

26th Dynasty

Late Period/Ptolemaic Period(?)

Ba is the Egyptian concept closest to what is meant by the English word “soul.” Its composite human-and-bird form symbolizes its ability to travel to different realms. This extremely fine amulet may date to the Ptolemaic Period, but various types of gold amulets inlaid with colored stones are known from burials of Dynasties 26 through 30 (c.664–342 B.C.)

Previous Next

gardant:

Mummy Board of Henettawy (C), Probable Sister-Wife of High Priest of Amun SmendesThird Intermediate Period, 21st Dynasty, ca. 990-970 B.C.EgyptMetropolitan Museum of Art

Discovered in a communal tomb dug in the courtyard of Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el-Bahri, this is the innermost element of a nest of coffins belonging to the Mistress of the House, Singer of Amun, Chief of the Harim of Amun, Flutist of Mut, and God’s Mother of Khonsu Henettawy (C).

The original gilding on the hands, breasts, earrings, and face on the outer surface of the board was hacked away by robbers. On the inner side, a figure of Imentet, goddess of the West (land of the dead), stands and offers ankhs (signifying life) to two human-headed birds representing the ba (soul) of the deceased. Flanking Imentet are two cobra-headed deities, then two emblems of the west symbolizing the goddesses Selket and Neith. In the lowest register, two mummiform images of Henettawy bracket a scepter that stands in for Anubis, god of embalming.

Los antiguos egipcios y el mundo de los muertosAmpa el 24 octubre, 2012 — Hacer un Comentario

LA GUÍA EN EL MÁS ALLÁ

Texto de Ampa Galduf/Arquehistoria

En su obsesión por alcanzar la vida eterna, los antiguos egipcios, se hicieron enterrar acompañados de una serie de fórmulas mágicas que les permitieran

llegar al Más Allá. Eran éstas, unas indicaciones, a modo de guía, para sortear los posibles peligros de un enigmático viaje de ultratumba que les

habría de llevar a una nueva vida.

Esta especie de consejos para facilitar al difunto la nueva vida, fueron inscritos en distintos soportes; papiro, paredes de las tumbas, sarcófagos, objetos del ajuar funerario del difunto, incluso en las vendas de lino de las momias, y hoy son conocidos como el Libro de los muertos.

Detalle de pintura egipcia representando el Ka y el Ba

Un egipcio moría cuando su Ka (o energia) abandonaba su cuerpo.

A partir de ahí, desposeído de su flujo vital dejaba de existir. En ese instante era cuando el BA (alma) se dirigía al encuentro

con los dioses para la realización de su juicio.

El difunto era llevado ante Osiris y su corazón pesado en una balanza frente a una pluma que representaba a Maât, la diosa

de la verdad y de la justicia.

Los que habían sido buenos accedían a la vida nueva como

espíritus transfigurados.

El difunto se salvaba cuando la pluma y el corazón quedaban en equilibrio

Los antiguos egipcios conservaron, durante más de tres milenios, su religión y sus creencias funerarias, fundamentadas, en esa desconocida otra vida. Ideas que, les llevaron a;

la elaboración de una serie de complejos rituales de embalsamamiento y momificiación, y

a enterrar a sus muertos en ricos recintos funerarios; templos, mastabas o pirámides.

Hacia el final del tercer milenio a.d.c, ya aparecen tempranos textos funerarios escritos sobre distintos objetos.

Estos textos inscritos en los sarcófagos de altos funcionarios del Imperio Medio comprendían más de 1000 sortilegios con las indicaciones sobre la vida bajo la tierra, en el reino de Osiris.

Allí los difuntos trabajarían en los Campos de las ofrendas y de los juncos. En estos textos se nos habla por primera vez del Juicio de los muertos, para alcanzar una vida nueva.

Más tarde, hacia el Tercer período Intermedio, XI-VII a. C. otras fórmulas mágicas, a modo de capítulos, formaron parte de los textos funerarios que hoy se conocen como “el Libro de los muertos” que siguieron las mismas pautas que aquellos primigenios sortilegios.

EL RITUAL FUNERARIO

Ritual egipcio de la apertura de la boca

Toda vez que la momia había sido preparada, el sacerdote realizaba el “Ritual de la Apertura de la Boca” para que eran una serie de conjuros mágicos.

Según un artículo de Historia National Geographic;[" Los egipcios creían que el difunto emprendía un viaje subterráneo desde el oeste hacia el este, como Ra, el sol, que tras ponerse vuelve a su punto de partida. Durante ese trayecto el fallecido, montado en la barca de Ra, se enfrentaría a seres peligrosos

que intentarían impedir su salida por el este y su renacimiento. El peor de ellos era Apofis, una serpiente que trataba de impedir el avance de la barca solar con el objeto de romper el Maat, la justicia y el orden cósmico, y forzar el caos. Apofis cada día amenazaba a Re durante su viaje subterráneo".]

¿Qué le esperaba al difunto en la otra vida?

El alma del fallecido con el beneplácito de Osiris tenia alguna de estas posibilidades;

Dirigirse al “Campo de paz” Acceder al cielo para vivir como las estrellas, Ser uno más junto a Osiris en un “mundo superior”, Viajar con Ra en su barca solar; o bien, una combinación de estos cuatro estados.

Los que eran juzgados como malos, eran lanzados a la diosa Amémet, “la tragona”, que fue representada con la parte

posterior de hipopótamo, la parte anterior de león y con cabeza de cocodrilo.

LA ETERNA MORADA DEL KA

Estatua de la pareja formada por Katep y Hetepheres encontrada en un tumba de Giza. La estatua servía para mantener viva la memoria de los dueños y su personalidad aunque su cuerpo fuera destruido

Tras la muerte, el Ka continuaba cerca del cuerpo del difunto. Los egipcios creían que el sarcófago o las esculturas y eran la morada eterna del

difunto, de su espíritu vital. Esa energía quedaba encadenada eternamente al sepulcro.

Es por ello, que se creyó en la necesidad de alimentarlo con todo aquello que solía formar parte de la vida cotidiana del difunto.

Los faraones eran enterrados con sus preciados objetos reales, y los egipcios pertenecientes a las clases altas junto a sus servidores que debían acompañarlos también en su otra vida.

Los que no eran ricos eran rodeados por estatuillas, o grabados que los representaban.

Los egipcios creían que “la representación de un objeto poseía las mismas cualidades del propio objeto”.

EL LIBRO DE LOS MUERTOS

Se convirtió en una especie de cara necesidad, enterrar a las momias con toda aquella literatura funeraria, consistente en una serie de instrucciones y ayuda

al difunto para dirigirse a la otra vida.

En el Imperio Antiguo, solo el faraón tenía derecho a estos hechizos e instrucciones pero, con el tiempo, éstas evolucionaron hasta conformar lo que

se conoce como “El Libro de los Muertos”.

Eso sí solo aquel que pudiera pagarlo, tendría acceso a él.

Este libro contiene cerca de 190 capítulos de fórmulas mágicas y rituales, ilustradas con dibujos para asistir al difunto en su viaje hacia la eternidad. Los

sacerdotes de los principales centros de culto como Menfis, Tebas o Hermópolis trataron de ponerlas en orden.

Las selecciones del “Libro de los Muertos” están contenidas en los papiros de Ani, Hunefer y Anhai, aunque entre sí guardan cierta confusión.

Como curiosidad:

En su sentido práctico, estos antiguos egipcios confeccionaron ejemplares “homologados” del Libro de los Muertos.

En estos papiros, el texto se escribía dejando en blanco el lugar correspondiente al nombre del difunto. Después el hueco era rellenado con el

nombre del comprador.

El precio de estos ejemplares era bastante más económico que el de los hechos por encargo, que podían llegar a costar un deben de plata, la mitad de

la paga anual de un campesino.

Aunque para los egipcios, el valor de este texto era incalculable, dado el inmesno valor que tenia para orientar a

sus difuntos en su otra vida.

Bibliografía: Donadoni Roveri, Ana Mª; Las Creencias Religiosas. Editorial. Electa

Turín Italia, 1988 Michalowki,K; El Arte en el Antiguo Egipto. Editorial. Electa

Turín(Italia) 1988 Wikipedia. El Libro egipcio de los Muertos

Imágenes:

Google images Wikimedia commons

ABYDOS; SECRETOS DE EGIPTO

Texto de José Manuel Peque/Paisajes del Pasado

Abydos es un lugar célebre y mágico, reverenciado por los egipcios durante toda su historia. Un sitio sagrado y mítico, donde la diosa Isis llevó los restos de su esposo Osiris para

resucitarlo. Después Osiris ingresaría en el inframundo-la Duat egipcia- para gobernarlo.

En Abydos se inica el culto a Osiris con los “Misterios de Osiris” que rememoraban la muerte, entierro y resurrección de del dios de los muertos. Fue una de las celebraciones más importantes del Imperio Medio, que premiaba a los devotos egipcios con la

promesa de vida eterna para ellos y sus

difuntos. Osiris rey de los muertos en la mitología egipcia, presidia el tribunal del

J uicio de los difuntos .

Su culto representaba el ritual de la muerte y resurección.

El país del Nilo, tiene muchos lugares cuyo nombre ha pasado a la Historia y que serán eternamente recordados por las maravillosas obras que albergan, de las cuales, muchas están aún por descubrir.

Sin embargo, existe un lugar, quizás menos conocido por los turistas pero, sin embargo, de gran interés por el arqueólogo y también para el estudioso de la cultura y la religión egipcia por la enorme carga emocional y simbólica que contenía para los antiguos egipcios.

Ese lugar es Abydos.

Bajorrelieve de Sethi I, en su templo funerario de Abidos.

Situado en ciudad de Tinis en el Alto Egipto, Abydos alberga una importante necrópolis donde fueron enterrados muchos reyes predinásticos.

También es interesante Abydos, para los arqueólogos, por el posible descubrimiento algo muy disputado entre sumerólogos y egiptólogos, de las más antiguas muestras de escritura presentes en pequeños fragmentos de tablillas y cerámicas fechadas en torno al 3300 – 3200 anteriores a nuestra era, precisamente en lo que se cree el sepulcro del Rey Escorpión.

EL CULTO A OSIRIS

Pero, aún es más interesante, si cabe, si a través de la mitología egipcia conocemos que, Abydos fue el lugar donde la gran diosa Isis llevó los restos

de su esposo Osiris y donde lo resucitó y concibió a Horus y, donde, finalmente, Osiris ingresó en el inframundo para convertirse en su

gobernante.

Por ello este lugar, Abydos, fue reverenciado por los egipcios durante toda su historia y considerado un sitio sagrado, como confirman los miles de restos de ofrendas descubiertas por el arqueólogo alemán Günter Dreyer sobre el terreno.

Tiene tantas connotaciones y posibles enigmas esta antigua necrópolis que incluso el geólogo Robert Schoch estudió el semisepultado Osireion para tratar de encontrar una evidencia arqueológica que demuestre su hipótesis

sobre la antigüedad de la Esfinge de Gizeh.

Por todo ello, queda por decir que Abydos, a medio camino entre la realidad, la hipótesis y la leyenda, quizás, sea el lugar que mejor representa todo lo que

significó y significará Egipto para las generaciones presentes, pasadas y futuras.

Artículo relacionado: Los egipcios y el mundo de los muertos

omgthatartifact:

Hatnefer’s Chair

Egypt, 1492-1473 BC

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

“Hatnefer was the mother of Senenmut, one of Hatshepsut’s best known officials. Her undisturbed tomb was discovered by the Museum’s Egyptian Expedition in 1936 on the hillside below Senenmut’s tomb chapel. This chair was found in front of the tomb’s entrance and was given to the Museum in the division of finds by the Egyptian government. Hatnefer’s chair is a fine example of Egyptian woodworking. The various elements were assembled with mortise-and-tenon joinery, and pegs were used to hold the tenons in place. Pegs also fasten the braces to the back and seat. The joins were reinforced with resinous glue. The decoration on the back of the chair includes a row of protective symbols. In the center is the god Bes, a deity who protected the home. On either side of the god are the tit amulet which is closely associated with the goddess Isis, and the djed pillar, which symbolizes stability and endurance. The seat, made of linen cord, is original.”

Previous Next

theancientworld:

Bracelets, Lapis Lazuli and gold, 940 BCE, 22nd Dynasty Ancient Egypt

“Gold cuff bracelet of Prince Nemareth: the inner side of the smaller segment of this bracelet is inscribed for a man with the Libyan name of Nimlot (also rendered as Nemareth or the like). The external decoration of the bracelet consists of geometric decoration and a figure of a child god. The god is represented in a typical ancient Egyptian manner for a male child: nude, wearing a long sidelock of hair and with a finger to the mouth. That this is not a mere human child, however, is indicated by his crook-shaped scepter of rule, the uraeus on his forehead, and his headdress, which is a lunar crescent and disk. The deity depicted on these bracelets is most probably Harpocrates. Two uraei guard the lunar symbols. Presumably, they represent the protective goddesses of Upper and Lower Egypt, which the Egyptians often equated with the ordered universe. And the blue lotus, on several of which the deity squats, is a symbol of creation from the primordial ocean, from which the sun first rose, and of birth and rebirth, presumably because that flower rises above the water when it opens each dawn. The bracelet was once inlaid with lapis lazuli.”

The British Museum

theancientworld:

Mummy Case, Egypt, Roman Period, Early 2nd century

“Mummy of a Greek youth, aged 19-21, named Artemidorus in a cartonnage body-case with mythological decoration in gold leaf and an encaustic on limewood portrait-panel covering the face and inscription on the chest. There is an inscription in Greek on the mummy-case.”

10.2012 - Natural Sciences Sector

Las lecciones que nos brindan las sequias del pasado

CC, Wikimedia Commons. Escena agrícola de la tumba de Nakht, 18a dinastía, Tebas

Un proyecto interdisciplinario involucrando a la comunidad de las ciencias de la Tierra y a biólogos, arqueólogos, historiadores, meteorólogos y astrofísicos dio un paso hacia el pasado para entender la velocidad a la que los ecosistemas y las civilizaciones eran capaces de recuperarse de sucesos catastróficos. Trabajando al unísono, juntaron las piezas de los eventos que pusieron de rodillas a los faraones, y como Egipto salió adelante.

Hace 11 300 años, el Sahara estaba lleno de lagos, jirafas, hipopótamos, leones, elefantes, cebras, gacelas, bovinos y caballos retozando en las praderas que se beneficiaban verdaderamente de una pluviosidad diez veces más abundante que la actual.

Hace 9 000 años, poblaciones de pastores ya habían colonizado una buena parte del Sahara. Ellos prosperaron durante todavía unos 3 000 años hasta que un deslizamiento de la zona de los monzones hacia las latitudes más bajas desvió las lluvias potenciales hacia fuera del continente, provocando catastróficas sequías. Las poblaciones se refugiaron en el Sahel, región de altiplanos, y en el valle del Nilo, donde dieron origen a numerosas culturas africanas, como la del Egipto de los faraones.

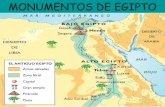

Las que se asentaron en el valle del Nilo tuvieron que abandonar el pastoreo nómada debido a la escasez de lluvias estivales. Adoptaron entonces un modo de vida agrícola. Las pequeñas comunidades sedentarias se unieron hasta formar importantes grupos sociales. Hace aproximadamente 5 200 años, el primer faraón logró unificar el Alto y el Bajo Egipto en un solo estado con Menfis como capital.

Un largo período de prosperidad iba a continuar, caracterizado por las crecidas del Nilo que producían abundantes cosechas de cereales. Fortalecidos por esta prosperidad, los faraones sucesivos lanzaron programas ambiciosos de construcción de pirámides con el fin de ofrecerse tumbas dignas de su rango. Los faraones afirmaban su autoridad sobre la población al reivindicar el poder de interceder ante los dioses para que el Nilo inunde la llanura cada año. La estrategia funcionaba perfectamente hasta 4 200 años antes de nuestra era, cuando las cosechas resultaron insuficientes durante seis largas décadas. Provocada por un descenso de la pluviosidad al nivel de las fuentes etíopes del Nilo durante un ciclo prolongado de El Niño, esta sequía fue tan larga y ruda que se podía atravesar el Nilo a pie enjuto. Ante la impotencia del faraón para impedir la hambruna generalizada, los gobernadores de las regiones se ampararon del poder.

Fueron necesarios 100 años a Egipto para reunificar y poner fin a ese siglo de caos político y social conocido como el Primer Período Intermediario. El retorno a la estabilidad anunciaba el advenimiento del Imperio Medio. Esta vez, los faraones estaban decididos a no repetir los mismos errores. Para evitar el fin de sus imprevisibles predecesores, invertirían masivamente en la irrigación y el almacenamiento del grano.

Esta investigación se realizó en 2003-2007en el marco de un proyecto Programa Internacional de Ciencias de la Tierra (PICG) sobre el papel de las catástrofes ambientales del Holoceno en la historia de la humanidad. La investigación interdisciplinaria de las catástrofes geológicas tiene interés para las civilizaciones y los ecosistemas futuros. Es necesario estudiar el pasado y, al hacerlo, las ciencias de la

Tierra pueden aportar información con una alta definición temporal (a escala social), además de determinar los indicadores fundamentales de los futuros cambios. El objetivo era examinar la velocidad a la que los ecosistemas y las civilizaciones eran capaces de recuperarse de sucesos catastróficos. Los estudios multidisciplinarios ya han dejado claros los efectos de cambios rápidos y catastróficos sobre sociedades anteriores, y este proyecto era una buena ocasión para evaluar la vulnerabilidad de las sociedades modernas hacia futuras catástrofes ambientales.

Suzanne Leroy

The Great Harris Papyrus

ancienthistorymjh:

The Great Harris Papyrus

From: Thebes, probably Deir el-Medina, Egypt

Date: around 1200 BC

Papyrus is a kind of paper made out of reeds. This particular papyrus rolls out to be an amazing 42 metres long (that’s almost as long as an Olympic sized swimming pool).

The papyrus is divided into five parts, each telling stories from the life of King Ramesses III. The first three parts show the King giving presents (called ‘offerings’) to the gods to keep them happy. You can see him on the right in the picture, wearing the special king’s head-dress, sash and kilt. He is facing three gods. The hieroglyphs say that he is giving them an incredible 309,950 sacks of grain. The final part of the papyrus shows a history of the reign of Ramesses, ending with his death in 1153 BC.

Animales en el Antiguo EgiptoAmpa el 20 noviembre, 2012 — Hacer un Comentario

LA RELACIÓN DE LOS ANTIGIOS EGIPCIOS CON LOS ANIMALES

Texto de J.Luis López de Guerñu Polán/ Mil historias

La mujeres y hombres de las antiguas civilizaciones, tenían un contacto más directo con los elementos de la naturaleza, y con los animales que habitaban en ella, a algunos de ellos los domesticaron, pero, en general los animales de todas las especies, incluso las fieras, formaban parte de su vida cotidiana como no ocurre en la actualidad, al menos entre las civilizaciones urbanas:

¿Como no divinizar a unos animales y tener versiones fantásticas sobre otros?

De hecho, los antiguos egipcios, como seguramente otras civilizaciones de las que tenemos menos noticias, tenían una idea distinta de los animales como tenemos en la actualidad.

Los veían como seres que reunían características comunes con los humanos creyendo que quizás estuvieran dotados de alma.

Lo cierto es, los antiguos habitantes del país del Nilo, mantuvieron una relación muy estrecha con el reino animal que en cada caso y momento era objeto de veneración o de alimento. Incluso los propios faraones eran representados con las partes del cuerpo de algunos animales, siendo comparados con aquellos a los que se consideraban dotados de virtuosas cualidades.

Hacia la época tardía aumentó el culto a los animales y en especial al gato, y se crearon leyes que castigaban a los que maltrataran a este felino.

Diosa egipcias Bastet, se la representaba bajo la forma de un gato doméstico

Aunque no se puede generalizar cuando del antiguo Egipto se habla, pues según nos encontremos en el norte o en el sur, en una ciudad o en otra, el trato que recibían los animales pudo ser muy distinto. Eso sí, los egipcios sentían temor hacia a un gran número de animales salvajes como los hipopótamos, cocodrilos o reptiles como las serpientes boas, pitones, cobras, sin olvidar a los felinos leones, panteras, o chacales.

En cambio, domesticaron a perros y gatos. Estos últimos eran animales sagrados por los que sentian especial adoración y gran respeto por sus vidas. Ambas mascotas eran momificadas y enterradas, a menudo, junto a sus dueños o en cementerios especiales para ellos en ataúdes propias y tras su muerte, incluso, se guardaba luto.

Nos han llegado numerosos relieves y pinturas que reflejan el papel espiritual y social del gato.También se solían hacer ofrendas de gatos momificados a la diosa Bastet a cambio de su protección, siendo vendidas por las sacerdotes.

El historiador griego Heródoto, fascinado por las culturas antiguas como la egipcia, dedicó uno de sus libros, el tomo II de Historias, a las costumbres egipcias.

Concibe su misión como historiador en un sentido muy amplio, pues nos habla de costumbres, paisajes, climas, fauna, vegetación… En cierto modo es un antropólogo que estudia las formas de vida y creencias de los diversos grupos humanos. Nos dejó escrito que

“Egipto no abunda mucho en animales, pero los que hay, sean o no domésticos y familiares, gozan de las prerrogativas de cosas sagradas. ¡Triste del egipcio que mate a propósito alguna de estas bestias!… Y ¡ay del que matare alguna ibiso algún gavilán! Sea de acuerdo, sea por casualidad, es preciso que muera por ello.

Respecto a los gatos, Heródoto escribió:

Los gatos después de muertos son llevados a sus casillas sagradas; y adobados en ellas con sal, van a recibir sepultura en la ciudad de Bubastris. Las perras son enterradas en sagrado en su respectiva ciudad, y del mismo modo se sepulta a los icneumones.

Bubatris alcanzó notoriedad en el siglo XVIII antes de Cristo, en la parte oriental del delta, y fue centro de culto a la diosa felina Bastet. Los icneumones eran ratas grandes (del tamaño de un gato) que cazaba reptiles. De ellos, el escritor griego, Claudio Eliano residente en Roma en el s.II, dijo que eran a la vez machos y hembras, pues tienen la capacidad de fecundar y de parir. Las mígalas -musarañas- y gavilanes son llevados a enterrar.Por otro lado Heródoto afirmaba que

“Egipto es un don del Nilo”, un río que impregnó todos los aspectos de la vida, incluida la mitológia:

Los egipcios veneran como sagradas las nutrias que se crian en sus ríos, y con particularidad entre todos los peces al que llaman lipdoto o escamoso, y a la anguila, pretendiendo que estas dos especies están consagradas al Nilo, como lo está entre las aves el ‘vulpanser’ o ganso bravo.

De los cocodrilos dijo que eran par algunos sagrados, para otros alimento. Otros incluso trataban de domesticarlo y adornándolo con joyas:

“Los cocodrilos son para algunos egipcios sagrados y divinos; para otros, al contrario, objeto de persecución y enemistad. Las gentes que moran en el país de Tebas o alrededor de la laguna Meris, se osbtinan en mirar en ellos una raza de animales sacros, y en ambos países escogen uno comunmente, al cual van criando y amansando de modo que se deje manosear, y al cual adornan con pendientes en las orejas, parte de oro y parte de piedras preciosas y artificales, y con ajorcas en las piernas delanteras.

Sobek, era desde las primeras dinastías egipcias, el Señor de las aguas, representado con cuerpo humano y cabeza de cocodrilo.

Regalado portentosamente cuando vivo, a su muerte se le entierra bien adobado en sepultura sagrada. No así los habitantes de la comarca de

Elefantina, que lejos de respetarlos como divinos, se sustentan con ellos a menudo.

Respecto a los hipopótamos dijo que

“Solo en la comarca de Papremis los hipopótamos o caballos de rio son reputados como divinos, no así en lo demás de Egipto. El hipopótamo… tiene unas uñas hendidas como el buey, las narices romas, las crines, la cola y la voz del caballo, los colmillos salidos, y el tamaño de un toro más que regular.”

La ciudad de Tebas estaba en el alto Egipto, relativamente cerca de Nubia. La laguna Meris de la que habla Heródoto, es la que se encuentra cerca de El Fayum, hoy un lago salado, al suroeste del delta. Elefantina es una isla rodeada por dos brazos del Nilo en el alto Egipto.

No Regular Man

Photograph courtesy Hendrickx/Darnell/Gatto, Antiquity

This ancient rock picture near Egypt's Nile River was first spotted by an explorer more than a century ago—and then almost completely forgotten.

Scientists who rediscovered it now think it's the earliest known depiction of a pharaoh.

The royal figure at the center of the panel wears the "White Crown," the bowling pin-shaped headpiece that symbolized kingship of southern Egypt, and carries a long scepter. Two attendants bearing standards march ahead of him; behind him, an attendant waves a large fan to cool the royal head. A hound-like dog with pointed ears walks at the ruler's feet. Surrounding the king are large ships, symbols of dominance, towed by bearded men pulling on ropes.

(See "Pictures: Secret Tunnel Explored in Pharaoh's Tomb.")

The picture, which was engraved on a sheer cliff face in the desert northwest of the city of Aswan, was probably created between roughly 3200 and 3100 B.C., according to researchers who published their discovery in December's issue of the journal Antiquity.

At around the same time that the picture was crafted, northern and southern Egypt were united under the reign of a supreme monarch, or pharaoh. The pharaoh in the picture may be Narmer, the king who overcame the last vestiges of northern resistance to

southern rule and is considered by many to be Egypt's founding pharaoh. (Read about Egypt’s first pharaohs in National Geographic magazine .)

This rock art picture, known as tableau 7a, is nearly ten feet (three meters) wide. That makes it the largest of the pictures at the site, called Nag el-Hamdulab after the neighboring village.

Earlier Egyptian art tends to show not kings themselves, but emblems of royal or divine power, said Yale University's John Darnell, one of the paper's authors. An image of a bull or falcon, for example, was often used as a stand-in for the king. When human rulers were shown, they were small and peripheral, as if they didn't count for much.

But here, for the first time, the king is dominant. "It's an amazing depiction, artistically and textually, of the birth of dynastic Egypt," Darnell said.

The change in the king's depiction reflects changes in the nature of kingship at the time, said Yale University archaeologist Maria Gatto, another author of the paper.

"He's not just a regular man like everyone else," she said. "He's a god, someone special who can help you be in contact with the supernatural."

—Traci Watson

Published November 29, 2012

El busto de Nefertiti, 100 años de belleza egipciaAmpa el 5 diciembre, 2012 — 3 Comentarios

El conocido busto de Nefertiti tiene unos 3.400 años de antigüedad, sin embargo, sólo hace un siglo que fue

descubierto a los ojos del mundo.

Desde entonces es considerado uno de los hallazgos más importantes del Antiguo Egipto.

Ludwig Borchardt, fue el egiptólogo que el 6 de diciembre de 1912 convirtió a la misteriosa esposa de Akenatón de la dinastía XVIII, en una verdadera diosa del arte egipcio. Tras su hallazgo, el busto fue adquirido por un coleccionista alemán que lo donó al Museo Egipcio de Berlín pasando a ser expuesto en el Neues Museum hasta la destrucción del edificio durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Por fortuna el busto fue salvaguardado.

Finalizada la guerra, y tras décadas de peregrinaje, la escultura se exhibió en diversos museos alemanes, hasta su regreso al rehabilitado Neues Museum de Berlín, en 2009. Allí el busto de la reina Nefertiti se expone ahora de modo especial con motivo de este 100 aniversario de su descubrimiento. Los egipcios ansían el momento de que el busto de la reina Nefertiti regrese a Egipto. Recientemente, han resurgido controversias que afirman que el busto de Nefertiti se sacó de Egipto con la escusa de que era un simple objeto de yeso, sin más valor.

UNA ESCULTURA CON DOS ROSTROS

Para desentrañar los misterios de este rostro femenino egipcio, la obra fue examinada utilizando TC- tomografría computerizada- por primera vez en 1992. Uno de los últimos estudios del famoso busto, realizado en 2009 por unos investigadores de Berlín con los avances más recientes de la técnica de TC, permitió descubrir bajo la parte exterior de esta escultura, un sorprendente rostro, esculpido en el núcleo interno de la piedra caliza.

La TC revelaba el verdadero rostro de la reina Nefertiti, oculto bajo la capa externa de su conocidísima escultura. Un rostro más imperfecto de lo que se creía :

Tenía arrugas en la comisura de los labios y en las mejillas, unos pómulos menos prominentes y una nariz imperfecta.

Los investigadores creen que el artista encargado de esculpir sobre piedra caliza la belleza de la reina, decidió añadir una nueva capa de estuco sobre la primera versión del busto, para adaptarla a los cánones estéticos de la época.

Una obra de arte en su interior

Se trata de un núcleo de piedra caliza cubierto p

or varias capas de estuco de diferente grosor.

Los resultados mostraron que se utilizó un proceso en múltiples pasos para crear la escultura.

La capa de estudio de la cara y las orejas es muy fina, pero la parte posterior de la corona reconstruida contiene dos capas de estuco gruesas. Las imágenes de TC mostraban varias fisuras y una unión no uniforme entre las capas.

La cara interna de piedra caliza fue esculpida con delicadeza y ligeramente simétrica.

En comparación con la cara de estuco más externa, la cara interna mostraba algunas diferencias: menos profundidad en las esquinas de los párpados, pliegues alrededor de las esquinas de la boca y las mejillas, pómulos menos prominentes y una ligera prominencia de la nariz. Las orejas de la escultura interior eran similares a las visibles en el exterior.

Por lo que este núcleo de piedra caliza no sólo fue un molde sino que se trató de una obra de arte, en la que el artista pudo hacer unos cuantos retoques siguiendo los cánones estéticos de su tiempo.

Alexandre Huppertz, director del estudio realizado por estos Investigadores del Imaging Science Institute de Berlín asegura que:

“hemos conseguido mucha información sobre cómo se realizó el busto hace más de 3.400 años por el escultor real. Descubrimos que la escultura tiene dos rostros ligeramente diferentes y hemos averiguado con las imágenes de TC cómo evitar los daños en este objeto tan valioso”.

Artículo relacionado Akenaton el faraón hereje

Queen Puabi’s Headdress, Diadem, Beaded Cape, and JewelryEarly Dynastic III (2550-2450 BCE)Royal Cemetery, Ur (modern day Iraq)

With Art Philadelphia:

Queen Puabi’s headdress, beaded cape and jewelry, all ca. 2550 BCE (includes comb, hair rings, wreaths, hair ribbons, and earrings) of gold, lapis lazuli, and carnelian, was excavated in the early 1930s by a joint Penn Museum/British Museum team, at the ancient Mesopotamian Royal Cemetery of Ur, in what is now Iraq. The Queen went to her final resting place accompanied by several hundred female attendants, several

guards, and a rich cache of objects. Puabi’s headdress included a frontlet with beads and pendant gold rings, two wreaths with poplar leaves, a wreath with willow leaves and inlaid rosettes, and a string of lapis lazuli beads. The comb would have been inserted in her hair at the back, leaving the flowers floating over her head. Her beaded cape and jewelry includes pins of gold and lapis lazuli, a gold, lapis lazuli and carnelian garter, lapis lazuli and carnelian cuff, and gold finger rings.

View images of the Penn Museum staff assembling the headdress here, and watch a video here.

art-of-swords:

The Sword of Tutankhamen

Created: 1333 BC - 1323 BC Culture: Pharaonic Technique: Metal Techniques Cast Style: New Kingdom Medium: Bronze

Tribute post: November 26th, 1922 archaeologist Howard Carter opened Tutankhamen’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt - thus I’m going to feature a special weapon today, the sword of Tutankhamen.

“King Tut” or Tutankhamen (alternately spelled with Tutenkh-, -amen, -amon), lived approx. 1341 BC – 1323 BC, was an Egyptian pharaoh of the 18th dynasty (ruled ca. 1332 BC – 1323 BC in the conventional chronology), during the period of Egyptian history known as the New Kingdom. His original name, Tutankhaten, means “Living Image of Aten”, while Tutankhamen means “Living Image of Amun”.

The sword of King Tutankhamen was an Egyptian Khopesh, the common sword used in Ancient Egypt times and was made by a single piece of bronze divided into three parts. The first part is the hilt, which is black. The second and third parts form the blade.

The second part is straight, on the same level as the handle, and is engraved with the figure of a lotus flower with a long stem. The third part is bent to form a curve, and is engraved with a long stripe.

The shape of this sword is the same as the sword held by the figure of the king, depicted on the perforated and gilded wood votive shield that was found in the tomb, and is considered to be ceremonial in purpose.

kemetically-ankhtified:

Black History Month fact #7

Toilets and sewerage systems existed in Kemet (aka Ancient Egypt). One of the pharaohs built a city now known as Amarna. An American urban planner noted that: “Great importance was attached to cleanliness in Amarna as in other Egyptian cities. Toilets and sewers were in use to dispose waste. Soap was made for washing the body. Perfumes and essences were popular against body odour. A solution of natron was used to keep insects from houses … Amarna may have been the first planned ‘garden city’.”

Aromatherapy dates back to Kemet, where natural perfumes were created and utilized as an art, a science, and a spiritual practice, used for cosmetic, medicinal, and ritual purposes. The Egyptians/Kemetians were the first to used herbs and spices as a fragrance.