Effects of Religious Orientation and Gender on Cardiovascular Reactivity Among Older Adults

-

Upload

ancuta-elena -

Category

Documents

-

view

5 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Effects of Religious Orientation and Gender on Cardiovascular Reactivity Among Older Adults

http://roa.sagepub.com/Research on Aging

http://roa.sagepub.com/content/27/2/221The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/0164027504270678

2005 27: 221Research on AgingKevin S. Masters, Tera L. Lensegrav-Benson, John C. Kircher and Robert D. Hill

Effects of Religious Orientation and Gender on Cardiovascular Reactivity Among Older Adults

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

can be found at:Research on AgingAdditional services and information for

http://roa.sagepub.com/cgi/alertsEmail Alerts:

http://roa.sagepub.com/subscriptionsSubscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navReprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.navPermissions:

http://roa.sagepub.com/content/27/2/221.refs.htmlCitations:

What is This?

- Jan 26, 2005Version of Record >>

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

10.1177/0164027504270678ARTICLERESEARCH ON AGINGMasters et al. / RELIGIOUS ORIENTATION

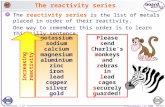

Effects of Religious Orientation andGender on Cardiovascular Reactivity

Among Older Adults

KEVIN S. MASTERSSyracuse University

TERA L. LENSEGRAV-BENSONUtah State University

JOHN C. KIRCHERROBERT D. HILL

University of Utah

Recent attention has focused on the relationship between religiosity and health.Although many pathways have been proposed to account for this relationship, littleempirical research has investigated specific pathways in relation to specific physio-logical functions. This study assessed the roles that religious orientation and genderplay in moderating psychophysiological reactivity to laboratory stressors amongolder adults. Those participants characterized by an intrinsic religious orientation(IO) demonstrated less reactivity than did those characterized by an extrinsic reli-gious orientation. Gender did not influence reactivity. There was some evidencethat the effect of religious orientation is more pronounced for interpersonal thancognitive-type stressors, although the strongest findings were evident when stressorswere aggregated. The magnitude of these effects suggests that they are of practicalsignificance. Given these results and the known relationship between reactivity andhypertension, it is proposed that IO may result in decreased risk of developing hyper-tension in older adults.

Keywords: religion; religious orientation; reactivity; aging; intrinsic

The relationship between religiosity and health has been the subject ofincreased interest among health researchers in recent years as demon-strated by this special issue and by the number of other respected scien-tific journals that recently published special issues on this topic or pre-sented a series of articles on it (e.g., American Psychologist, Annals ofBehavioral Medicine, Health Education & Behavior, Journal of Health

221

RESEARCH ON AGING, Vol. 27 No. 2, March 2005 221-240DOI: 10.1177/0164027504270678© 2005 Sage Publications

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Psychology, Psychological Inquiry). (Religiosity will be used inter-changeably with spirituality or religiousness. Use of these terms hasbeen discussed elsewhere [Hill and Pargament 2003; Miller andThoresen 2003; Thoresen 1999].) It has been argued on the basis of avariety of empirical studies that something beneficial related to healthand well-being is associated with religion. What is not understood,and barely studied, are particular aspects of religiosity that relate tospecific indicators of health or disease. Authors recently suggestedthat religiosity and health research move away from general measuresthat have dominated the field, such as church attendance or denomina-tional affiliation, and move toward more conceptually groundedmeasures (Hill and Pargament 2003; Powell, Shahabi, and Thoresen2003). Hill and Pargament (2003) noted that the commonly usedindexes underestimate the complexity of religion and overlook thepossibility that something inherent within religious experience influ-ences health.

Although they have not been adequately studied, several pathwaysconnecting religion and health have been proposed (George, Ellison,and Larson 2002). Of importance to this article are the effects of beliefsystems or forms of religious orientation on psychological and physi-cal functioning (George et al. 2002; Hill and Butler 1995; Levin andVanderpool 1991; McIntosh 1995; McIntosh and Spilka 1990).George and colleagues (2002) suggested that religious orientation hasbeen understudied with respect to health. Nevertheless, previous stud-ies reviewed by Donahue (1985) and Masters and Bergin (1992) indi-cate this may be a fertile area of inquiry because the intrinsic religiousorientation (IO) has been found to consistently relate to better mentalhealth (e.g., lower anxiety, lower depression, greater tolerance andself-control), whereas extrinsic religious orientation (EO) relates topoorer psychological functioning.

222 RESEARCH ON AGING

AUTHORS’ NOTE: This research was supported in part by grant 1 R03 AG 18554-01awarded by the National Institute on Aging. We thank Timothy W. Smith, James A. Blumenthal,Carl E. Thoresen, Edward M. Heath, and Jennifer A. Fallon for their assistance. Correspondenceconcerning this article should be directed to Kevin S. Masters, Department of Psychology, Syra-cuse University, 430 Huntington Hall, Syracuse, NY 13244; phone: (315) 443-3666; fax: (315)443-4085; e-mail: [email protected].

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

RELIGIOUS ORIENTATION

IO and EO were conceptualized by Allport and Ross (1967) basedon the assumption that church attenders are not a homogeneous group.They defined IO as characteristic of individuals who view religionitself as an end or master motive. These individuals embrace a reli-gious creed, internalize it, and attempt to follow it. Other needs areless important and are, therefore, met only to the degree that they cor-respond with the central religious beliefs. Attendance at church forthose characterized by IO may be thought of as motivated by desire forspiritual growth. EO, on the other hand, is characterized by individu-als who use their religion to serve utilitarian purposes such as enhanc-ing their security or status, providing self-justification for actions, orpromoting social or political aims. Their church attendance is lessmotivated by a desire for spiritual growth and more influenced byother factors.

Although Allport and Ross’s formulation is less than 40 years old,the basic concept that religious involvement may be fueled by intrin-sic or extrinsic motives is prominent throughout history. For example,the Book of Job tells that Job is accused by his adversary as being abeliever who will lose faith if he does not maintain the rewards towhich he is accustomed. Job is accused of possessing EO. WilliamJames (1902) similarly discussed the concepts of firsthand direct reli-gion versus secondhand institutional religion.

A major aspect of religiosity for those who are characterized by IOis that religions provide a coherent and comprehensive worldview thatprovides meaning in life (Ellison 1991; Hill and Pargament 2003) anda way to understand, or even construct beneficial explanations for,life’s potentially stressful circumstances. For example, religions teachthat despite whatever challenges may be presently faced, God isbenevolent and will provide peace or a way of coping in this life andreward in the next. Someone abiding by these principles, aspects ofIO, would seemingly be less likely to respond to a variety of stressorswith arousal or anger. This is not assumed for EO, however, which is aless principled approach to religiosity and lacks guidance for copingstressful encounters.

Prominent within religions are teachings specifically regardingproper attitudes and conduct in interpersonal situations. Williams(1989) noted that the world’s prominent religions instruct regarding

Masters et al. / RELIGIOUS ORIENTATION 223

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

the value of service, hope, trust, and kindness toward others. Incorpo-ration of these characteristics into one’s cognitive schema and behav-ioral response style is likely to result in less stress and arousal in anumber of situations, most prominently those that are interpersonal innature, as compared to adoption of characteristics that religions typi-cally denounce or try to limit such as cynicism, self-absorption, andbasic mistrust of others. Similarly, Hill and Pargament (2003) notedthat the world’s great religions emphasize both the Golden Rule andthe value of human relationships. In fact, these relationships may beseen as a metaphor for one’s relationship with God (Buber 1970).Those intrinsically devoted to their religious creed should, therefore,be more committed to their relationship with God and to behaving inaccord with God’s instruction regarding the values associated withinteracting with other humans than would those characterized by EO.In fact, EO-type individuals may view relations with others through autilitarian prism that may increase the stressful properties of such rela-tionships. The Christian principle of “love thy neighbor” is relevant.Consequently, given the religious emphasis placed on achieving andmaintaining loving and kind relationships, it follows that those whoincorporate these edicts into their lives will experience less interper-sonal stress, and this reduced stress will be manifest in many ways,including decreased psychophysiological indicators of stressresponse.

RELIGION, HYPERTENSION, AND REACTIVITY

A particular area of interest for religion and health research gener-ally, and for studies of psychophysiological reactivity in particular,pertains to how religion may influence the development and course ofhypertension; a significant health concern in the United States. Recentfigures suggest that hypertension afflicts 50 million Americans (Izzo,Levy, and Black 2000). Because blood pressure (BP) steadilyincreases with age, the risk of developing clinically significant hyper-tension is more pronounced among older adults. Interestingly, severalinvestigators (Hixson, Gruchow, and Morgan 1998; Koenig et al.1998; Levin and Vanderpool 1989; Seeman, Dubin, and Seeman2003) report the intriguing possibility of a protective effect of religionsuch that individuals demonstrating higher levels of religiosity are aptto have lower measures of BP. Of particular interest, Hixson and col-

224 RESEARCH ON AGING

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

leagues (1998) and Nelson (1989) suggested that IO may be a signifi-cant factor accounting for the beneficial influence of religion on BP.

Presently, between 80% and 90% of cases of hypertension have noknown cause, although many theories are being advanced (Gibbons1998). Psychological factors and the sympathetic nervous systemhave long been suspected as playing key roles in at least some of thesecases. For many years, investigators hypothesized that chronic, exag-gerated psychophysiological reactivity to stress has a connection withhypertension. Psychophysiological reactivity is typically defined asthe change from baseline on a physiological measure that occurs inresponse to the presentation of a stressor stimulus. The most com-monly investigated physiological variables in reactivity studies relatedto hypertension are BP and heart rate (HR), although a number ofother relevant variables have been examined (e.g., sodium and potas-sium excretion; aspects of renal hemodynamics; renin, catechol-amine, and cortisol levels), and studies using impedance cardiographyhave supplied evidence for the presence of different hemodynamic(e.g., increased peripheral resistance versus increased HR) responsepatterns to reactive stimuli based on ethnicity, type of stimulus, cop-ing activities, and other variables. Various stimuli have also been usedto induce reactivity in laboratory studies. Recent writers have focusedon the particular importance of interpersonal stressors (Linden, Gerin,and Davidson 2003; Waldstein et al. 1998) as well as the need for mul-tiple stressors within studies (Kamarck and Lovallo 2003; Kamarcket al. 1992; Schwartz et al. 2003). In the strong form, heightened reac-tivity is hypothesized to be causally linked with hypertension, where-as in the milder form, exaggerated reactivity is limited to the role ofmarker for hypertension risk (Gerin et al. 2000). Debate regarding theadequacy of the evidence for a causal link between reactivity andhypertension continues (Gerin et al. 2000; Linden et al. 2003; Lovalloand Gerin 2003; Schwartz et al. 2003); however, support for the pre-dictor model has solidified (Treiber et al. 2003). Even if it is eventu-ally demonstrated that reactivity is not causally related to hyperten-sion, its status as a marker of future risk has importance and clinicalusefulness in studying disease processes.

Older adults are not only more likely to develop hypertension butare also characterized as generally more religious than their youngercounterparts (Koenig 1997). Consequently, investigation of the spe-cific nature of the relationship between religion and hypertension

Masters et al. / RELIGIOUS ORIENTATION 225

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

among older adults is particularly important. Furthermore, olderadults are underrepresented in reactivity studies (Uchino et al. 1999;Vitaliano et al. 1993) in general, and there are no studies of the effectsof religiosity on reactivity in this population. Adding to the impor-tance of studying reactivity in older adults are findings indicating pos-sible age-related differences in reactivity profiles. For example, it hasbeen documented that older individuals tend to demonstrate smallerHR increases in response to psychological stress but show greater BP,particularly systolic BP (SBP), reactivity (Folkow and Svanborg 1993;McNeilly and Anderson 1996; Uchino et al. 1999; Uchino, Kiecolt-Glaser, and Cacioppo 1992). Perhaps of even more importance is theobservation of variability within the older population (Folkow andSvanborg 1993; Uchino et al 1999). Jennings and colleagues (1997),for example, in a study of reactivity among middle-aged men con-cluded that individual differences (e.g., personality traits, social fac-tors) were likely to play a major role in determining reactivity. Overthe course of many years, the effects of variables that influence cardio-vascular response to stress are likely enhanced, producing either moreor less favorable reactivity profiles among aging individuals. Conse-quently, religious orientation constitutes a promising construct forevaluating religiosity and reactivity in this population.

Finally, the influence of gender on reactivity as it reacts with reli-gious orientation is of interest. Women are recognized as generallybeing more religious than men, and there have been suggestions ofgender differences in reactivity among older people. For example,Seeman and colleagues (2001) found that older women demonstratedgreater hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) response to challenge,as measured by salivary cortisol, when compared with older men.Vitaliano et al. (1993) found increased BP reactivity for older womencompared with older men but only in response to an emotional task (5minutes speaking about current relationship with spouse) and not to acognitive stressor. Uchino and colleagues (1999) found no differenceson measures of reactivity to a speech and math stressor between menand women who ranged in age from 30 to 70 years. They noted thatfew studies have compared older adult men and women within thesame sample. Given the greater religiosity among women and unclearpatterns of reactivity noted in previous studies, it is not known if andhow gender will influence reactivity when considered along withreligious orientation.

226 RESEARCH ON AGING

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

STUDY PURPOSE

This study was designed to determine the influence of religious ori-entation, separately and crossed with gender, on cardiovascular reac-tivity to laboratory stressors in a sample of older adults. It was hypoth-esized that individuals characterized by IO would demonstrate lessaggregated reactivity than EO participants. No specific hypotheseswere developed regarding the interaction of gender and religious ori-entation because this has not been previously tested, and theoreticalarguments could be advanced for either more or less reactivity.Because type of stressor has proven to be an important variable in pastreactivity research (Kamarck and Lovallo 2003; Waldstein et al. 1998)and because religious teachings and values may have more saliencefor interpersonal or confrontational interactions than for less personalstressors, exploratory analyses investigating the influence of religiousorientation on different types of stressors were conducted. It washypothesized that IO participants would demonstrate less reactivity tothe interpersonal situation than EO participants and that there wouldbe no differences on the cognitive task.

Method

RECRUITMENT

Participants were self-selected in response to advertisements inlocal newspapers and on television programs that announced a studyof “religion and stress.” Targeted recruitment was also conducted viaannouncements to seniors’ groups. For inclusion, individuals wererequired to be between the ages of 60 and 80 years. Individuals werefurther screened for depression (Geriatric Depression Scale–ShortForm [Yesavage et al. 1983] inclusion cutoff score > 5), dementia(Mini-Mental State Examination [Folstein, Folstein, and McHugh1975] inclusion cutoff score < 24), and recent history (past 5 years) ofmyocardial infarction or cerebrovascular accident. Those exhibitingany of these conditions were excluded from the study. Individuals stillqualified underwent a final screening wherein they completed theReligious Orientation Scale (ROS) to determine if they met classifica-tion criteria for either IO or EO.

Masters et al. / RELIGIOUS ORIENTATION 227

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

The ROS measures religious orientation using 20 items dividedbetween two scales (i.e., intrinsic and extrinsic). A prototypic intrinsicitem is “My religious beliefs are what really lie behind my wholeapproach to life,” whereas a representative extrinsic item is “Thechurch is most important as a place to formulate good social relation-ships.” The ROS is the most widely used measure in the empiricalstudy of religion and has been the subject of much discussion (Kirk-patrick and Hood 1990, 1991; Masters 1991). Donahue (1985) con-ducted a comprehensive review and meta-analysis and concluded thatthe ROS provides a powerful instrument to resolve controversies sur-rounding religion and mental health. Burris (1999) ended his reviewof the ROS by concluding that the research on its theoretical basis andpsychometric properties was “generally supportive” (p. 150). Internalconsistency estimates for the intrinsic scale are typically in the mid.80s and for the extrinsic scale are in the .70s. Two-week test-retestreliabilities of .84 and .78 for intrinsic and extrinsic have beenreported (Burris 1999). Consistent with Donahue’s (1985) recom-mendation for use of the scale to obtain distinct types and maintainconsistency across samples, participants had to score either above 27on the intrinsic scale and below 33 on the extrinsic scale (the respec-tive theoretical midpoints) to qualify as demonstrating IO, or they hadto score below 27 on the intrinsic scale and above 33 on the extrinsicscale to qualify as exhibiting EO.

PROCEDURES

Baseline. Qualified individuals were scheduled for an appointmentat the psychophysiology laboratory at one of two western U.S. univer-sities where they individually participated in the experiment. Theywere instructed to abstain from caffeine (coffee, tea, and colas) for 12hours and refrain from cigarette smoking for 1 hour prior to theirappointment. Upon arrival, all participants were greeted by a researchassistant, completed institutional review board approved writteninformed consent statements, and identified the most important per-son in their lives (e.g., grandchild, boy/girl friend, etc.). A finger cufffor recording continuous BP was then attached to the middle phalanxof the middle finger of their nondominant hand. The nondominantlower arm was positioned at heart level and held stationary on a sup-portive table throughout the experiment. Subsequently, participants

228 RESEARCH ON AGING

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

entered a 10-minute baseline period in which they completed a mini-mally involving activity (i.e., reviewing National Geographic maga-zines and choosing their favorite story).

Reactivity manipulations. The first of two reactivity tasks was thenintroduced. Order of presentation of the two tasks was counterbal-anced, and all participants completed both tasks, that is, a cognitivestressor task (mental arithmetic) and interpersonal challenge (roleplay). The effect of verbal behavior was controlled by having partici-pants speak continuously for equal time intervals on both tasks.

The mental arithmetic challenge required participants to performserial subtractions of 13 and additions of 7 (starting at 600) aloud for180 seconds. Participants were instructed to work as quickly as theycould without making mistakes. During the trial, participants were leftalone in the lab (reducing the immediate interpersonal element in thestressor) but informed that their performance was being recorded on acassette tape sitting visibly nearby.

The interpersonal challenge required participants to role-play con-frontation with an insurance adjuster who had just denied payment fora medically necessary intervention (bone marrow transplantation) forthe person they had earlier identified as most important to them. Theywere told that the insurance coverage was denied because of theexpense and scarcity of local providers who were authorized by theinsurance company to perform the procedure even though competentand experienced physicians capable of performing it practiced nearby.Participants were instructed to take 5 minutes to prepare theirresponse (180 seconds) to be given in front of the research assistantand a small audience consisting of three experimental assistants(increasing the salience of the interpersonal nature of the task). Afterthe first task, participants entered a second 10-minute baseline periodidentical to the first before being introduced to the second reactivitytask. At the conclusion of the second reactivity task, the participantswere paid $30 and thanked for their cooperation.

MEASURES

Physiological. Recordings of BP and HR were monitored duringbaseline and experimental periods using a procedure adapted fromSmith and colleagues (1997). A 2300 Finapres portable Blood Pres-

Masters et al. / RELIGIOUS ORIENTATION 229

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

sure Monitor (Ohmeda, Englewood, CA) provided the measures. Pre-vious studies have documented the reliability and validity of HR aswell as SBP and diastolic BP (DBP) reactivity assessments using theFinapres (Parati et al. 1989; Podlesny and Kircher 1999), and it hasbeen used in a number of previous reactivity studies.

Baseline physiological functioning was determined by averagingreadings of BP and HR collected at 15-second intervals throughoutthe last three minutes of the baseline period prior to presentation ofeach stressor. Thus, a single mean baseline measure was recorded foreach participant prior to exposure to each stressor condition. Mea-sures of BP and HR were collected at 15-second intervals during thethree minutes of exposure to the stressor situations as well. Theseobservations were then averaged to produce mean SBP, DBP, and HRfor each stressor.

Covariates. Previous research suggests a number of variables thatmay influence reactivity. Although it is not possible to control all ofthem in any one study, we collected measures of education level, ade-quacy of social contacts (rated from inadequate to adequate), traitanger (State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory–2 [STAXI-2]; Spiel-berger 1999), and physical activity (CAPS Typical Week PhysicalActivity Survey [CAPS]; Ainsworth et al. 2000) to use as covariates.There is evidence that each of these variables may influence reactivity.For complete psychometric information on the STAXI-2 and CAPS,readers are referred to the original references.

DATA ANALYSIS

Consistent with recommendations about the choice of reactivityindexes (Llabre et al. 1991) and publications in this field (Smith et al.1997), mental arithmetic minus baseline and role play minus baselinechange scores were calculated for each dependent measure. Thesescores were then aggregated in accord with the literature for improv-ing the reliability of laboratory reactivity measures (Gerin et al. 2000;Kamarck et al. 1992; Schwartz et al. 2003). Aggregated physiologicalchange scores were analyzed in a 2 (religious orientation) × 2 (gender)analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), where measures of educationlevel, adequacy of social contacts, trait anger, and total met minutes ofweekly physical activity served as covariates. Subsequent exploratory

230 RESEARCH ON AGING

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

calculations used the same analytic strategy with stressor type addedas a within-subjects independent variable. Standardized effect sizeswere also estimated to assess the magnitude of significant effects.

Results

PARTICIPANTS

The final sample consisted of 75 older adults (48% female, 95%European American) divided equally between IO (n = 37 ) and EO(n = 38) groups. Men and women distributed evenly among religiousorientation groups. The sample averaged 71.65 years of age, had amean income of $44,148 per year (median = $40,000), and approxi-mately half possessed a four-year college degree. Half of the womenwere taking some form of hormone replacement medication, and theywere distributed equally among religious orientation groups.

REACTIVITY OUTCOMES

Mean aggregate change scores for SBP, DBP, and HR are displayedin Table 1.

SBP. The 2 × 2 ANCOVA calculated on SBP revealed a significantmain effect for religious orientation, F(1, 66) = 7.57, p < .01. The IOgroup demonstrated less SBP reactivity than the EO group. The inter-action was not significant and neither was the main effect of gender.

Masters et al. / RELIGIOUS ORIENTATION 231

TABLE 1

Mean and Standard Deviation Blood Pressure and Heart Rate ReactivityChange Scores Aggregated Across Stressors

SBP DBP HR

M SD M SD M SD

All IO (n = 37) 18.914 20.343 11.341 8.857 7.671 9.451All EO (n = 38) 32.174 18.584 17.176 10.464 5.540 5.827All female (n = 36) 26.729 16.996 15.310 8.851 6.521 7.690All male (n = 39) 24.421 23.466 13.262 11.121 6.686 8.140

NOTE: SBP = systolic blood pressure; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; HR = heart rate; IO = in-trinsic religious orientation; EO = extrinsic religious orientation.

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

DBP. For DBP, the 2 × 2 ANCOVA again revealed a significantmain effect for religious orientation, F(1, 66) = 5.44, p < .05. As withSBP, the IO group demonstrated dampened reactivity relative to theEO group. The interaction and main effect of gender were notsignificant.

HR. The data for HR do not follow the trend for BP. The 2 × 2ANCOVA was not significant, although the main effect of religiousorientation approached the traditional cutoff (p = .10). In this case,however, it is the EO group that demonstrated marginally lowerreactivity.

Clinical significance. The following analyses shed light on theextent that the statistically significant findings described above are ofsufficient magnitude to be practically meaningful. One method usedto make such estimates is to calculate an effect size statistic using thestandardized mean difference; d = (M1 – M2) /SD pooled. This provides anestimate of the magnitude of the effect independent of sample size.Cohen (1992) developed guidelines for interpreting these effects inbehavioral research. The effect sizes for the comparisons between IOand EO for SBP and DBP are .68 and .61, respectively. According toCohen’s (1992) system, these are in the medium size range.

EXPLORATORY ANALYSES

Because it was tentatively hypothesized that the salient aspects ofIO would be more influential in interpersonally stressful situationsand because previous research has documented the importance of typeof stressor, particularly social stressors (Kamarck and Lovallo 2003;Larkin et al. 1998; Linden, Rutledge, and Con 1998; Waldstein et al.1998), in reactivity research, exploratory analyses (ANCOVA) identi-cal to those above, except for the inclusion of stressor type as a within-subjects variable, were conducted. None of the interaction terms thatincluded stressor type were significant, although the Stressor Type ×Religious Orientation interaction approached significance (p = .07)for SBP. Subsequent exploratory analyses showed that IO and EO dif-fered significantly during the role play (p < .01), with IO demonstrat-ing reduced reactivity, but not during the mental arithmetic. The effectsize of this significant difference was d = .66, a medium effect.

232 RESEARCH ON AGING

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Discussion

This study showed that older adults who vary in their religious ori-entation demonstrate significantly different BP reactivity to aggre-gated laboratory stressors. The differences remained when the effectsof education level, perceived adequacy of social contacts, trait anger,and weekly physical activity were statistically controlled. Specifi-cally, older participants characterized by IO displayed reduced BPreactivity, both SBP and DBP, when compared with EO individuals.Furthermore, the magnitude of these differences suggests they areclinically meaningful, particularly if they are generally characteristicof the individuals’ typical functioning. The effect sizes found here arelarger than those for many established cardiovascular disease risk fac-tors, including lack of exercise, Body Mass Index, and waist:hip ratio(Rutledge and Loh 2004).

The BP reactivity differences underscore the importance of study-ing individual-difference variables within the older population.Although aging results in predictable patterns of change in cardiovas-cular and other body systems, these changes are not invariant in termsof rate or type. Identification of factors that influence the process ofphysical change experienced by individuals as they age is important.This study suggests that religious orientation is one such variable, andit should be added to a small but growing database of research on psy-chologically relevant individual-difference variables that influencecardiovascular reactivity among older persons (Uchino et al. 1999). Itwas also noted in the exploratory analyses that although there wassome support for the specificity of IO with regard to type of stressor,the bulk of the evidence herein suggests that religious orientation isinfluential across stressors.

Although it is true that religious creeds specifically teach theimportance of relationships with others based on kindness and love,they also offer general suggestions of comfort in all of life’s circum-stances based on the premise that a God sympathetic to the challengesencountered by believers will ease their pain and angst. Ultimately forthe religious mind, transcendence of the material world will bringabout lasting peace. Those who internalize these tenets of faith (IO)may be predisposed to generally see the world as less threatening andmore psychologically safe. This may be exhibited in an overalldampening of stress reactivity.

Masters et al. / RELIGIOUS ORIENTATION 233

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Another possible, perhaps complementary, explanation for thereduced reactivity of IO individuals could lie in the strength thatcomes from adopting a coherent and comprehensive worldview thathas explanatory power and provides meaning to life (Ellison 1991;Hill and Pargament 2003). Antonovsky (1979) referred to this as asense of coherence, and Ryan, Rigby, and King (1993) termed it iden-tification; a form of religious internalization. Ellison (1991), investi-gating the related concept of existential certainty, found that this con-struct mediated the relationship between church attendance andpsychological well-being. Intrinsic religiosity may offer one pathwayto a meaningful worldview and/or existential certainty. This is notmeant to imply that IO, or any religious construct for that matter, pro-vides the only path to meaning in life (cf. Masters, Ives, and Shearer1997; Ross 1990). Yet, particularly toward the end of life, having asense of a firmly held religious worldview may prove comforting inthe face of daily hassles or larger life stresses.

Findings regarding HR did not conform to the patterns found forBP. Religious orientation did not have a significant effect, but thetrend in the data was in the opposite direction, that is, lower HR reac-tivity for the EO group. Considering the hemodynamic pattern of allthree cardiovascular measures, it is clear that the differentiallyincreased BP reactivity experienced by those in the EO condition wasnot due to differentially increased HR and is therefore due to eitherincreased stroke volume, greater vascular peripheral resistance, orboth. Given what is known about functioning of the autonomic ner-vous system during stressful encounters and the effects of aging on thevasculature (Folkow and Svanborg 1993; McNeilly and Anderson1996), it seems likely that peripheral resistance was at least a contribu-tor to the greater BP reactivity for the EO participants. More impor-tant, it is believed that the general age-related increase in BP found inWestern societies is largely the result of stiffening arterioles and otherfactors that result in increased peripheral resistance (Gibbons 1998;Lakatta 1990) rather then being due to increased cardiac output. Thepattern of reactivity demonstrated by the EO participants is consistentwith what has been termed a vascular response, that is, a responsemediated by alpha-adrenergic activity that is characterized by restric-tion in the periphery (Kline et al. 2002; Saab and Schneiderman1995). This pattern, in turn, has been implicated as more likely to pre-dict increased BP and a variety of other negative outcomes (e.g., vas-

234 RESEARCH ON AGING

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

cular endothelial dysfunction, left-ventricular hypertrophy) than hasthe beta-adrenergic response that seems more characteristic of theIO participants. The beta-adrenergic response is associated withincreases in myocardial activity but not by increased circulatory resis-tance. If true, this indicates that older adults who demonstrate EO alsodemonstrate a pattern of reactivity that is generally considered tomore strongly predict subsequent pathologic end points. Speculationregarding the patterns of reactivity as they relate to religious orienta-tion needs investigation through direct examination via impedancecardiography techniques. Simple BP and HR data cannot confirmthese hunches, although they provide an intriguing beginning.

Similar to what has been found in at least some of the limitedresearch with older adults, there were no findings of differences inreactivity based on gender. Because a variety of factors, includingsmall sample size, can produce null findings, effect sizes were calcu-lated for comparisons that included gender. None of these reached thelevel of a small effect, that is, d = .20. Thus, among older adults, itappears that neither gender alone nor gender in combination with reli-gious orientation influences reactivity to stress. Nevertheless, givenprevious findings on the effects of menopause on reactivity (Faraget al. 2003) and the fact that few studies have considered genderamong older adults in a reactivity paradigm, it is too soon to rule outgender as a variable. Furthermore, pertaining to reactivity and religi-osity, the present investigation is the only study yet conducted on anolder sample, and it is known that male-female differences exist inreligious commitment and experience. Thus, until a substantial data-base has developed that includes studies incorporating a variety oftypes of psychological stressors (cf. Vitaliano et al. 1993), researchersare encouraged to continue investigating effects of gender in reactiv-ity studies with older adults.

There are several limitations of this study. A significant one thatdirectly suggests possibilities for future research is the lack of mea-surement of variables that, as indicated in the discussion, may mediatethe religious orientation-reactivity relationship. For instance, therewere no measures of sense of coherence or purpose in life. Follow-upstudies of these and other possible mediators is indicated. Similarly,only some of the many potentially important confounding variableswere assessed and statistically controlled. Reactivity research hasgrown in many directions, and it is not possible to control all potential

Masters et al. / RELIGIOUS ORIENTATION 235

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

confounds in one study. The effects seen in this study could poten-tially vanish if controls for other variables were implemented. Itshould be noted, however, that the interpretive significance of co-variate effects depends on the theoretical and practical issues involvedwith the particular variables in the context of the particular study.Another limitation of the present study is that the stability and ecolog-ical validity of the findings remain unknown. This study establishesreligious orientation as a variable to be considered in reactivity assess-ments, but the extent to which these laboratory-based results concurwith those obtained by ambulatory measures in the field awaits furtherinvestigation. The relation between these findings and actual healthoutcomes is also not known.

This study included only two of the four possible religious orienta-tion types that may be obtained with the ROS (IO; EO; nonreligious—low scores on both scales; indiscriminately pro-religious—high scoreson both scales), and religious orientation is only one of the many waysof conceptualizing and specifying the broad phenomenon of religios-ity. Studies using all four types and studies incorporating other reli-gious constructs into reactivity investigations are indicated. Finally,there has been debate about the precise nature of the IO and EO con-structs. In keeping with the previous recommendation, some investi-gators may want to measure finer aspects of these orientations to see ifIO and EO may be further divided in ways that are useful in terms ofhow they relate with psychophysiological reactivity to varying stress-ful stimuli. For example, some may want to study the personal (Ep)and social (Es) dimensions of extrinsic religiosity proposed by Kirk-patrick (1989) and determine if these predict reactivity differentlydepending on the stressor involved. Nevertheless, given these resultsand those of previous studies, it seems that the molar concept of reli-gious orientation remains worthy of further investigation in its ownright.

REFERENCES

Ainsworth, Barbara E., Michael J. LaMonte, Melicia C. Whitt, Melinda L. Irwin, and KatrinaDrowatzky. 2000. “Development and Validation of a Typical Week Physical ActivityQuestionnaire to Assess Moderate Intensity Activity in Minority Women, Ages 40 and

236 RESEARCH ON AGING

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Older.” Presented at the NIH Women’s Health Community Research Conference, October,Bethesda, MD.

Allport, Gordon W. and J. Michael Ross. 1967. “Personal Religious Orientation and Prejudice.”Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 5:432-43.

Antonovsky, Aaron. 1979. Health, Stress, and Coping. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.Buber, Martin. 1970. I and Thou. New York: Scribner.Burris, Christopher T. 1999. “Religious Orientation Scale (Allport & Ross, 1967).” Pp. 144-54 in

Measures of Religiosity, edited by Peter C. Hill and Ralph W. Hood Jr. Birmingham, AL:Religious Education Press.

Cohen, Jacob. 1992. “A Power Primer.” Psychological Bulletin 112:155-59.Donahue, Michael J. 1985. “Intrinsic and Extrinsic Religiousness: Review and Meta-Analysis.”

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 48:400-19.Ellison, Christopher G. 1991. “Religious Involvement and Subjective Well-Being.” Journal of

Health and Social Behavior 32:80-99.Farag, Noha H., Wayne A. Bardwell, Richard A. Nelesen, Joel E. Dimsdale, and Paul J. Mills.

2003. “Autonomic Responses to Psychological Stress: The Influence of Menopausal Status.”Annals of Behavioral Medicine 26:134-38.

Folkow, Björn and Alvar Svanborg. 1993. “Physiology of Cardiovascular Aging.” PhysiologicalReviews 73:725-64.

Folstein, Marshal F., Susan E. Folstein, and Paul. R. McHugh. 1975. “Mini-Mental State: A Prac-tical Method of Grading the Cognitive State of Patients for the Clinician.” Journal of Psychi-atric Research 12:189-98.

George, Linda K., Christopher G. Ellison, and David B. Larson. 2002. “Explaining the Relation-ship Between Religious Involvement and Health.” Psychological Inquiry 13:190-200.

Gerin, William, Thomas G. Pickering, Laura Glynn, Nicholas Christenfeld, Amy Schwartz,Douglas Carroll, et al.. 2000. “An Historical Context for Behavioral Models of Hyperten-sion.” Journal of Psychosomatic Research 48:369-77.

Gibbons, Gary H. 1998. “Pathobiology of Hypertension.” Pp. 2907-18 in Comprehensive Car-diovascular Medicine, edited by Eric J. Topol. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott.

Hill, Peter C. and Eric M. Butler. 1995. “The Role of Religion in Promoting Physical Health.”Journal of Psychology of Christianity 14:141-55.

Hill, Peter C. and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2003. “Advances in the Conceptualization and Mea-surement of Religion and Spirituality: Implications for Physical and Mental HealthResearch.” American Psychologist 58:64-74.

Hixson, Karen A., Harvey W. Gruchow, and Don W. Morgan. 1998. “The Relation Between Reli-giosity, Selected Health Behaviors, and Blood Pressure Among Adult Females.” PreventiveMedicine 27:545-52.

Izzo, Joseph L., Daniel Levy, and Henry R. Black. 2000. “Importance of Systolic Blood Pressurein Older Americans.” Hypertension 35:1021-24.

James, William. 1902. The Varieties of Religious Experience. New York: Random House.Jennings, J. Richard, Thomas Kamarck, Stephen Manuck, Susan A. Everson, George Kaplan,

and Jukka T. Salonen. 1997. “Aging or Disease? Cardiovascular Reactivity in Finnish MenOver the Middle Years.” Psychology and Aging 12:225-38.

Kamarck, Thomas W., J. Richard Jennings, Thomas T. Debski, Ellen Glickman-Weiss, Paul S.Johnson, Michael J. Eddy, et al. 1992. “Reliable Measures of Behaviorally-Evoked Cardio-vascular Reactivity From a PC-Based Test Battery: Results From Student and CommunitySamples.” Psychophysiology 29:17-28.

Kamarck, Thomas W. and William R. Lovallo. 2003. “Cardiovascular Reactivity to Psychologi-cal Challenge: Conceptual and Measurement Considerations.” Psychosomatic Medicine65:9-21.

Masters et al. / RELIGIOUS ORIENTATION 237

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Kirkpatrick, Lee A. 1989. “A Psychometric Analysis of the Allport-Ross and Feagin Measures ofIntrinsic-Extrinsic Religious Orientation.” Pp. 1-30 in Research in the Social Scientific Studyof Religion, vol. 1, edited by Monty L. Lynn and David O. Moberg. Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Kirkpatrick, Lee A. and Ralph W. Hood Jr. 1990. “Intrinsic-Extrinsic Religious Orientation: TheBoon or Bane of Contemporary Psychology of Religion?” Journal for the Scientific Study ofReligion 29:442-62.

. 1991. “Rub-a-dub-dub: Who’s in the Tub? Reply to Masters.” Journal for the ScientificStudy of Religion 30:318-21.

Kline, Keith A., Patrice G. Saab, Maria M. Llabre, Susan B. Spitzer, Jovier D. Evans, Paige A. G.McDonald, et al. 2002. “Hemodynamic Response Patterns: Responder Type Differences inReactivity and Recovery.” Psychophysiology 39:739-46.

Koenig, Harold G. 1997. Is Religion Good for Your Health? Binghamton, NY: Hawthorn.Koenig, Harold G., Linda K. George, Judith C. Hays, David B. Larson, Harvey J. Cohen, and Dan

G. Blazer. 1998. “The Relationship Between Religious Activities and Blood Pressure inOlder Adults.” International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 28:189-213.

Lakatta, Edward G. 1990. “Similar Myocardial Effects of Aging and Hypertension.” EuropeanHeart Journal (Supplement G) 11:29-38.

Larkin, Kevin T., Elizabeth M. Semenchuk, Nicole L. Frazer, Sonia Suchday, and Robert L. Tay-lor. 1998. “Cardiovascular and Behavioral Response to Social Confrontation: MeasuringReal-Life Stress in the Laboratory.” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 20:294-301.

Levin, Jeffrey S. and Harold Y. Vanderpool. 1989. “Is Religion Therapeutically Significant forHypertension.” Social Science Medicine 29:69-78.

. 1991. “Religious Factors in Physical Health and the Prevention of Illness.” Preventionin Human Services 9:41-64.

Linden, Wolfgang, William Gerin, and Karina Davidson. 2003. “Cardiovascular Reactivity: Sta-tus Quo and a Research Agenda for the New Millenium.” Psychosomatic Medicine 65:5-8.

Linden, Wolfgang, Thomas Rutledge, and Andrea Con. 1998. “A Case for the Usefulness of Lab-oratory Social Stressors.” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 20:310-16.

Llabre, Maria M., Susan B. Spitzer, Patrice G. Saab, Gail H. Ironson, and Neil Schneiderman.1991. “The Reliability and Specificity of Delta Versus Residualized Change as Measures ofCardiovascular Reactivity to Behavioral Challenges.” Psychophysiology 28:701-11.

Lovallo, William R. and William Gerin. 2003. “Psychophysiological Reactivity: Mechanismsand Pathways to Cardiovascular Disease.” Psychosomatic Medicine 65:36-45.

Masters, Kevin S. 1991. “Of Boons, Banes, Babies, and Bath Water: A Reply to the Kirkpatrickand Hood Discussion of Intrinsic-Extrinsic Religious Orientation.” Journal for the ScientificStudy of Religion 30:312-17.

Masters, Kevin S. and Allen E. Bergin. 1992. “Religious Orientation and Mental Health.”Pp. 221-232 in Religion and Mental Health, edited by J. F. Schumaker. New York: OxfordUniversity Press.

Masters, Kevin S., Dune E. Ives, and David S. Shearer. 1997. “Religious Orientation as a Media-tor of Type A Hostility.” Presented at the 105th annual convention of the American Psycho-logical Association, August 18, Chicago.

McIntosh, Daniel N. 1995. “Religion-as-Schema, With Implications for the Relation BetweenReligion and Coping.” International Journal of Psychology of Religion 5:1-6.

McIntosh, Daniel N. and Bernard Spilka. 1990. “Religion and Physical Health: The Role of Per-sonal Faith and Control Beliefs.” Pp. 167-94 in Research in the Social Scientific Study of Reli-gion, vol. 2, edited by Monty L. Lynn and David O. Moberg. Greenwich, CT: JAI.

McNeilly, Maya and Norman B. Anderson. 1996. “Age Differences in PhysiologicalResponses.” Pp. 163-201 in Aging and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, edited by Paul E.Ruskin and John A. Talbott. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

238 RESEARCH ON AGING

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Miller, William R. and Carl E. Thoresen. 2003. “Spirituality, Religion, and Health: An EmergingResearch Field.” American Psychologist 58:24-35.

Nelson, Patricia B. 1989. “Ethnic Differences in Intrinsic/Extrinsic Religious Orientation andDepression Among the Elderly.” Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 3:199-204.

Parati, Gianfranco, Roberto Casadei, Antonella Groppelli, Marco Di Rienzo, and GiuseppeMancia. 1989. “Comparison of Finger and Intra-Arterial Blood Pressure Monitoring at Restand During Laboratory Testing.” Hypertension 13:647-55.

Podlesny, John A. and John C. Kircher. 1999. “The Finapres (volume clamp) Recording Methodin Psychophysiological Detection of Deception Examinations: Experimental ComparisonWith the Cardiograph Method.” Forensic Science Communication 1:1-17.

Powell, Lynda H., Leila Shahabi, and Carl E. Thoresen. 2003. “Religion and Spirituality: Link-ages to Physical Health.” American Psychologist 58:36-52.

Ross, Catherine E. 1990. “Religion and Psychological Distress.” Journal for the Scientific Studyof Religion 29:236-45.

Rutledge, Thomas and Cathy Loh. 2004. “Effect Sizes and Statistical Testing in the Determina-tion of Clinical Significance in Behavioral Medicine Research.” Annals of Behavioral Medi-cine 27:138-45.

Ryan, Richard M., Scott Rigby, and Kristi King. 1993. “Two Types of Religious Internalizationand Their Relations to Religious Orientations and Mental Health.” Journal of Personalityand Social Psychology 65:586-96.

Saab, Patrice G. and Neil Schneiderman. 1995. “Biobehavioral Stressors, Laboratory Investiga-tion, and the Risk of Hypertension.” Pp. 49-82 in Cardiovascular Reactivity to PsychologicalStress and Disease, edited by Jim Blascovich and Edward S. Katkin. Washington, DC:American Psychological Association.

Schwartz, Amy R., William Gerin, Karina W. Davidson, Thomas G. Pickering, Jos F. Brosschot,Julian F. Thayer, et al. 2003. “Toward a Causal Model of Cardiovascular Response to Stressand the Development of Cardiovascular Disease.” Psychosomatic Medicine 65:22-35.

Seeman, Teresa E., Linda F. Dubin, and Melvin Seeman. 2003. “Religiosity/Spirituality andHealth: A Critical Review of the Evidence for Biological Pathways.” American Psychologist58:53-63.

Seeman, Teresa E., Burton Singer, Charles W. Wilkinson, and Bruce McEwen. 2001. “GenderDifferences in Age-Related Changes in HPA Axis Reactivity.” Psychoneuroendocrinology26:225-40.

Smith, Timothy W., Jill B. Nealey, John C. Kircher, and Jeff P. Limon. 1997. “Social Determi-nants of Cardiovascular Reactivity: Effects of Incentive to Exert Influence and EvaluativeThreat.” Psychophysiology 34:65-73.

Spielberger, Charles D. 1999. STAXI-2 State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory–2. Odessa, FL:Psychological Assessment Resources.

Thoresen, Carl E. 1999. “Spirituality and Health: Is There a Relationship?” Journal of HealthPsychology 4:291-300.

Treiber, Frank A., Thomas Kamarck, Neil Schneiderman, David Sheffield, Gaston Kapuku, andTeletia Taylor. 2003. “Cardiovascular Reactivity and Development of Preclinical and Clini-cal Disease States.” Psychosomatic Medicine 65:46-62.

Uchino, Bert N., Janice K. Kiecolt-Glaser, and John T. Cacioppo. 1992. “Age-Related Changesin Cardiovascular Response as a Function of a Chronic Stressor and Social Support.” Journalof Personality and Social Psychology 63:839-46.

Uchino, Bert N., Darcy Uno, Julianne Holt-Lunstad, and Jeffrey B. Flinders. 1999. “Age-RelatedDifferences in Cardiovascular Reactivity During Acute Psychological Stress in Men andWomen.” Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences 54B:339-346.

Masters et al. / RELIGIOUS ORIENTATION 239

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Vitaliano, Peter P., Joan Russo, Sandra L. Bailey, Heather M. Young, and Barbara S. McCann.1993. “Psychosocial Factors Associated With Cardiovascular Reactivity in Older Adults.”Psychosomatic Medicine 55:164-77.

Waldstein, Shari R., Serina A. Neumann, Halina O. Burns, and Karl J. Maier. 1998. “Role-Played Interpersonal Interaction: Ecological Validity and Cardiovascular Reactivity.”Annals of Behavioral Medicine 20:294-301.

Williams, Redford. 1989. The Trusting Heart. New York: Times Books.Yesavage, Jerome A., T. L. Brink, Terence L. Rose, Owen Lum, Virginia Huang, Michael Adey,

et al. 1983. “Development and Validation of a Geriatric Depression Screening Scale: A Pre-liminary Report.” Journal of Psychiatric Research 17:37-49.

Kevin S. Masters is an associate professor of psychology and director of ClinicalTraining at Syracuse University. His Ph.D. in clinical psychology is from BrighamYoung University, and he completed a health psychology internship at Duke Univer-sity Medical Center. His research includes religion and health, exercise psychology,and presurgical psychological evaluations.

Tera L. Lensegrav-Benson received her M.S. from Utah State University where she iscurrently a doctoral student in psychology. She recently completed her thesis on reli-gious orientation, health, and physical activity. Her other research interests includedementia and physical activity, eating disorders, and psychology in primary care set-tings.

John C. Kircher received his Ph.D in experimental psychology from the University ofUtah. He is director of the Learning, Cognition, and Research Methods program inthe Department of Educational Psychology at the University of Utah. He has an ac-tive program of research in the area of detection of deception.

Robert D. Hill is a professor and chair of the Department of Educational Psychologyat the University of Utah. He received his Ph.D. from Stanford University. In 2004, hecompleted a Fulbright Fellowship at Maastricht University in the Netherlands. Hisareas of interest include health psychology, life span development, and aging.

240 RESEARCH ON AGING

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on April 30, 2014roa.sagepub.comDownloaded from