Effect of timing of postoperative chemotherapy on survival of dogs with osteosarcoma

Transcript of Effect of timing of postoperative chemotherapy on survival of dogs with osteosarcoma

1343

Effect of Timing of Postoperative Chemotherapy onSurvival of Dogs with Osteosarcoma

BACKGROUND. After excision of primary tumors, initiation of chemotherapy forJohn Berg, D.V.M.1

micrometastases is often delayed for 2 to 4 weeks to permit patient recovery andMark C. Gebhardt, M.D.2

early healing of the surgical wound. However, studies using murine tumors haveWilliam M. Rand, Ph.D.3

indicated that removal of a primary tumor may cause increased cell proliferation

within micrometastases during the first 7 to 10 days after surgery, potentially1 Department of Surgery, School of Veterinaryrendering the micrometastases more susceptible to chemotherapy. Clinical trialsMedicine, Tufts University, North Grafton, Mas-

sachusetts. assessing the value of early postoperative initiation of chemotherapy for human

breast carcinoma have yielded conflicting results. Osteosarcoma of dogs is a natu-2 Orthopedic Research Laboratory, Massachu-rally occurring model for human tumors likely to have micrometastases at thesetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.time of diagnosis.

3 Department of Community Health, School of METHODS. Before surgery, 102 dogs with osteosarcoma were randomized to receiveMedicine, Tufts University, Boston, Massachu- cisplatin and doxorubicin chemotherapy beginning either 2 days or 10 days aftersetts.

amputation. Survival analysis was performed for each treatment group and for a

historic control group comprised of 162 dogs treated by amputation alone.

RESULTS. Median survival times for dogs treated by amputation alone and for dogs

receiving chemotherapy beginning 2 or 10 days after surgery were 5.5, 11.5, and

11.0 months, respectively. Survival was significantly longer for each of the two

groups of dogs receiving chemotherapy than for control dogs (P õ 0.0001). There

was no significant difference in survival between treatment groups (P Å 0.727).

CONCLUSIONS. These results do not disprove the theory that removal of a primary

tumor alters the growth kinetics of metastases, but do imply that there is no

substantial advantage to early postoperative initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy

for spontaneous tumors of large species. Cancer 1997;79:1343–50.

q 1997 American Cancer Society.Abstract presented at the meetings of the Veteri-nary Cancer Society, Monterey, California, Octo-

KEYWORDS: animal models, osteosarcoma, canine, metastases, chemotherapy.ber 20–23, 1996, and the American College ofVeterinary Surgeons, San Francisco, California,

TNovember 3–6, 1996. he optimal time to initiate chemotherapy for micrometastases aftersurgical removal of a primary tumor is unknown. In clinical prac-

Supported by The Greenwall Foundation, New tice, initiation of chemotherapy often is delayed for 2–4 weeks toYork, New York. permit patient recovery and early healing of the surgical wound. How-

ever, historically, three theoretic benefits of initiating chemotherapyThe authors thank Dr. Robert C. Rosenthal (Vet-

during the early postoperative period have been proposed. First, it iserinary Specialists of Rochester, Rochester,possible that perioperative chemotherapy may eliminate tumor cellsNew York) for treating five of the dogs describedreleased into the circulation at the time of surgery. This in part wasin this article.the rationale behind clinical trials investigating the efficacy of a single

Address for reprints: John Berg, D.V.M., De- course of perioperative chemotherapy for patients with breast carci-partment of Surgery, Tufts University School noma.1–4 Second, the Goldie-Coldman hypothesis suggests that at aof Veterinary Medicine, 200 Westboro Rd., N. very early stage in the growth history of tumors, spontaneous muta-Grafton, MA 01536.

tions begin to produce clones of cells with inherent drug resistance,and that even a short delay in the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapyReceived September 12, 1996, revision receivedmay seriously compromise the response to treatment.5 Finally, studiesNovember 27, 1996; accepted December 13,

1996. using experimental murine tumors have indicated that surgical exci-

q 1997 American Cancer Society

/ 7b52$$0973 03-04-97 16:17:41 cana W: Cancer

1344 CANCER April 1, 1997 / Volume 79 / Number 7

sion of primary tumors may result in a transient in- vant chemotherapy.1 Although chemotherapy im-proved long term survival, the benefits of adjuvantcrease in cell proliferation within micrometastases

during the early postoperative period, potentially ren- therapy appeared to be lost when its initiation wasdelayed for 3 weeks, suggesting that the timing of ther-dering the micrometastases more susceptible to che-

motherapy.6–12 The latter studies, which are briefly de- apy significantly influenced its efficacy. In a study per-formed by the Ludwig Breast Cancer Study Group, pa-scribed below, provided the rationale for the current

study. tients with lymph node positive breast carcinoma wererandomized to receive several cycles of combinationAn early observation regarding the effect of a pri-

mary tumor on the growth of metastases was that in chemotherapy beginning either within 36 hours ofmastectomy or 25–32 days after surgery.2 There wasmice with transplanted Lewis lung carcinoma, the

growth of lung metastases decreased as the primary no significant difference in 4-year survival betweengroups. In a similar trial conducted by an Italian coop-tumor enlarged, and increased after the primary tumor

was removed.6 Subsequent studies using the same tu- erative group, patients with lymph node positivebreast carcinoma were randomized to receive combi-mor model,7 murine mammary adenocarcinoma,8,9

and murine osteosarcoma10 confirmed this finding. nation chemotherapy beginning either within 48–72hours of surgery or within 30 days of surgery.4 NoUsing thymidine labeling, these studies also docu-

mented increased cell proliferation within metastases significant difference in 5-year survival was detectedbetween groups. The latter studies suggest that initia-after primary tumor removal,7–10 and showed that the

change in growth kinetics was caused by recruitment tion of chemotherapy during the early postoperativeperiod is not of critical importance.of noncycling cells into the proliferating pool.8 Cell

proliferation increased within 24 hours of surgery, was Canine osteosarcoma is a well established, natu-rally occurring animal model for human osteosar-maximal at 2 or 3 days, and returned to normal within

7–10 days.8,9 Studies were next undertaken to deter- coma.15 More broadly, the tumor is an excellent modelfor any human primary tumor likely to have microme-mine whether this phenomenon could be exploited

therapeutically by administering chemotherapy dur- tastases at the time of surgical resection. Canine osteo-sarcoma arises most commonly in the metaphyses ofing the period of increased cell proliferation. In mice

with mammary adenocarcinoma, metastatic growth the long bones of the extremities, and occurs exclu-sively in large and giant breeds of dogs.15–17 As in hu-was significantly decreased and survival was signifi-

cantly improved if chemotherapy was given on the day mans,the relatively young are most often affected.15–17

Virtually all dogs have the same stage of disease at theof surgery as opposed to 3 or 7 days after surgery.11 Ina murine osteosarcoma model, a significant improve- time of diagnosis (i.e., there is regional invasion of soft

tissues by the primary tumor, and micrometastasesment in mean survival and a significant reduction inmetastatic burden at 9 weeks after initiation of treat- are present).15–17 The most common metastatic site is

the lung.15–17 After treatment by amputation alone, thement were found when chemotherapy was given peri-operatively rather than 2 weeks postoperatively.12 Re- median survival time is approximately 5 months, and

only 10% of dogs survive beyond one year.16,17 Severalcent studies have demonstrated that a primary murineLewis lung carcinoma inhibits growth and vasculariza- studies, performed by the authors and others, have

shown that survival is improved by the administrationtion of its lung metastases,13 that this inhibition is re-versed by removal of the primary tumor,13 and that of adjuvant cisplatin,18–22 doxorubicin,23 or both.24 The

median survival time after administration of eithervarious transplantable human primary tumors inhibitcorneal angiogenesis in mice.14 These studies support drug is approximately 1 year, although adjuvant che-

motherapy is rarely curative.18–24 Use of chemotherapythe concept that a primary tumor may inhibit thegrowth of its metastases, and suggest that this inhibi- has been associated with an increase in the frequency

of treatment failures caused by metastases totion may be in part mediated by control of angiogene-sis. bone.18,22–24 Prognostic factors that have been identi-

fied to date are patient age (survival times are greatestClinical trials have been conducted to assess theimportance of initiating chemotherapy during the for dogs between 7 and 10 years of age, and shorter

for both younger and older dogs17) and tumor sizeearly postoperative period in the treatment of humanbreast carcinoma. These trials have yielded conflicting (time required for the development of radiographically

apparent pulmonary metastases is inversely related toresults. In a study performed by the Scandinavian Ad-juvant Chemotherapy Study Group, patients received tumor size25).

The purpose of this study was to investigate theeither a single 6-day course of cyclophosphamide be-ginning immediately after surgery, identical chemo- influence of the timing of postoperative chemotherapy

on the survival of dogs with osteosarcoma.therapy beginning 3 weeks after surgery, or no adju-

/ 7b52$$0973 03-04-97 16:17:41 cana W: Cancer

Timing of Postoperative Chemotherapy/Berg et al. 1345

MATERIALS AND METHODS etal radiography, abdominal ultrasonography, biopsy,or postmortem examination. Survival time was de-Animals

One hundred and two dogs with previously untreated, fined as the time from surgery until death or euthana-sia because of metastasic disease.histologically confirmed osteosarcoma of a long bone

of an extremity were entered in the study betweenJanuary 1992 and January 1995. All dogs were evalu- Statistical Methods

All statistical computations were performed using aated prior to treatment with a complete blood count,serum chemistry profile, and thoracic radiographs. To software package (SPSS for Windows, Release 6.0; SPSS

Inc., Chicago, IL). To document that the randomiza-document that chemotherapy was effective in improv-ing survival of the treated dogs, the survival of these tion process minimized the potential confounding ef-

fects of the known clinical prognostic factors for ca-dogs was compared with the survival of 162 dogs withappendicular osteosarcoma treated by amputation nine osteosarcoma, the mean ages of the dogs in each

treatment group were compared with a two-samplealone. The authors recently described detailed survivaldata for this historic control group.17 All treated and Student’s t test, and the distribution of tumor locations

(proximal to the knee or elbow versus distal to thecontrol dogs were free of radiographically detectablepulmonary metastases and complicating concurrent knee or elbow), a reflection of tumor size, were com-

pared with a chi-square test.diseases prior to treatment.As the study progressed, an apparent difference

between treatment groups in the frequency of clini-TreatmentPrior to surgery, the 102 treated dogs were randomized cally apparent myelosuppression after the first cycle

of chemotherapy was noted. The proportions of dogsto receive postoperative cisplatin and doxorubicinchemotherapy beginning either 2 days or 10 days after that became ill due to myelosuppression in each treat-

ment group were compared using a chi-square test.amputation. Randomization was performed by one in-vestigator (J.B.). Fifty-three dogs received chemother- The proportions of dogs that died or were euthana-

tized due to signs of myelosuppression in each treat-apy beginning 2 days after surgery, and 49 dogs re-ceived chemotherapy beginning 10 days after surgery. ment group were compared using Fisher’s exact test.

One dog that received chemotherapy beginning 10After the first cycle of chemotherapy, 6 dogs treated 2days after surgery and 2 dogs treated 10 days after days after surgery developed severe neutropenia (45

neutrophils/mL 1 week after treatment) but did notsurgery died or were euthanatized because of severemyelosuppression, leaving 47 dogs in each treatment become ill, possibly because prophylactic oral antibi-

otics were given throughout the treatment period. Thisgroup. Each of these dogs received a total of 3 cycles ofchemotherapy at 3-week intervals. Cisplatin (Platinol; dog was omitted from these analyses. Neutrophil

counts at matched time intervals in the two treatmentBristol Laboratories, Syracuse, NY) was administeredat a dosage of 60 mg/m2 , intravenously (i.v.), using a groups were compared using repeated measures anal-

ysis of variance.6-hour diuresis protocol.26 Doxorubicin (Adriamycin;Adria Laboratories,Columbus, OH) was administered Survival analyses were performed both including

and excluding dogs that died or were euthanatized1 to 2 hours prior to cisplatin, at a dosage of 15–20mg/m2 i.v. Complete blood counts were obtained 1 because of chemotherapy toxicity. Kaplan–Meier

product limit estimates of survival were generated forand 2 weeks after each of the first 2 treatments, anda complete blood count and serum creatinine level all three groups. Comparisons of survival between

groups were performed using the log rank test. Thewere obtained immediately prior to each treatment.For dogs that developed severe gastrointestinal toxic- proportions of treated and control dogs that were eu-

thanatized because of bone metastases were com-ity or clinical signs of myelosuppression after the firsttreatment, the subsequent doxorubicin dose was re- pared using a chi-square test.

For all statistical analyses, Põ 0.05 was consideredduced by 25%. There were 14 dose reductions for the47 dogs treated 2 days after surgery, and 8 dose reduc- significant. All tests of statistical significance were two

sided.tions for the 47 dogs treated 10 days after surgery.

Follow-Up Evaluations RESULTSPatient Characteristics and Tumor LocationsFollow-up information was obtained by telephone

contact with owners at 3-month intervals. When clini- Patient characteristics and tumor locations for thegroups are given in Table 1. All dogs weighed ú 20 kg,cal signs compatible with metastatic disease devel-

oped, physical examinations were performed and me- and a wide range of breeds was represented. Therewere no significant differences between treatmenttastases were confirmed by thoracic radiography, skel-

/ 7b52$$0973 03-04-97 16:17:41 cana W: Cancer

1346 CANCER April 1, 1997 / Volume 79 / Number 7

TABLE 1Patient Characteristics and Tumor Locations

Group

Chemotherapy 2 days Chemotherapy 10 days Amputation aloneParameter after surgery (n Å 47) after surgery (n Å 47) (n Å 162)

Age (yrs)Range 1.25–13.33 1.75–12.00 0.75–13.00Mean 7.07 7.97 7.90

GenderMale intact 5 7 62Male neutered 22 12 24Female intact 1 1 21Female neutered 19 27 55

Tumor locationsProximal humerus 14 16 53Proximal femur 1 1 6Distal femur 8 6 23Scapula 1 0 3Distal radius 16 12 45Distal ulna 2 1 4Proximal tibia 1 3 16Distal tibia 4 8 12

Proximal limb-total 24 23 85Distal limb-total 23 24 77

groups in distribution of patient ages (P Å 0.10) ortumor locations (P Å 0.87).

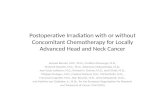

ToxicosesAfter the first chemotherapy treatment, 16 of the 53dogs (30.2%) that received chemotherapy 2 days aftersurgery became clinically ill due to myelosuppression.Omitting the dog that received prophylactic oral anti-biotics, 8 of 48 dogs (16.6%) that received chemother-apy 10 days after surgery became clinically ill due tomyelosuppression. This difference was not significant(P Å 0.11). Six of the 53 dogs (11.3%) that receivedchemotherapy 2 days after surgery and 2 of the 48 FIGURE 1. Mean neutrophil counts at various time intervals for dogs

with osteosarcoma treated with chemotherapy beginning either 2 days ordogs (4.2%) that received chemotherapy 10 days aftersurgery died or were euthanatized due to myelosup- 10 days after surgery. The first cycle of chemotherapy was given at Week

0, and the second cycle was given at Week 3. There were no significantpression. This difference was not significant (PÅ 0.27).There were no significant differences between treat- differences between treatment groups in neutrophil counts at various time

intervals. Pre: neutrophil counts prior to surgery.ment groups in neutrophil counts at various time in-tervals (Fig. 1). Toxicoses other than myelosuppressionwere rare. One dog in each group developed an inci-sional infection. ment groups than for the control group (P Å 0.0004).

Survival data for the dogs are summarized in Table 3.Survival was significantly longer for each of the twoSurvival Data

The status of the dogs at the time of reporting and sites groups of dogs receiving chemotherapy than for con-trol dogs (P õ 0.0001)(Fig. 2). There was no significantof metastases in dogs that died or were euthanatized

because of metastatic osteosarcoma are given in Table difference in survival between dogs receiving chemo-therapy beginning 2 days after surgery and dogs re-2. The proportion of dogs euthanatized because of

bone metastases was significantly higher for the treat- ceiving chemotherapy beginning 10 days after surgery

/ 7b52$$0973 03-04-97 16:17:41 cana W: Cancer

Timing of Postoperative Chemotherapy/Berg et al. 1347

TABLE 2Patient Status and Sites of Metastases

Group

Chemotherapy 2 days Chemotherapy 10 days Amputation aloneStatus after surgery (n Å 47) after surgery (n Å 47) (n Å 162)

Alive, NED 7 6 8Died or euthanatized,

nontumor-related 3 5 39Lost to follow-up 0 0 1Local tumor recurrence 0 0 3Euthanatized, metastases 32 33 107Died, metastases 5 3 4Sites of metastases

Lungs 19 (51.4%) 18 (50.0%) 93 (83.8%)Bone 11 (29.7%) 9 (25.0%) 8 (7.2%)Lungs and bone concurrently 3 (8.1%) 3 (8.3%) 7 (6.3%)Other 4 (10.8%) 6 (16.7%) 3 (2.7%)

NED: no evidence of disease.

TABLE 3Summary of Survival Data

Group

Chemotherapy 2 Chemotherapy 10 Amputationdays after days after surgery alone

Parameter surgery (n Å 47) (n Å 47) (n Å 162)

Median survival (mos) 11.5 11.0 5.51-year survival rate 48.0% 46.2% 11.5%2-year survival rate 28.3% 27.5% 2.0%3-year survival rate 15.3% 18.0% 2.0%

FIGURE 2. Kaplan–Meier estimates of survival for dogs with osteosar-(P Å 0.727). The 95% confidence interval for the differ- coma treated by amputation alone and for dogs receiving chemotherapyence in median survival time between treatment beginning either 2 days or 10 days after surgery. Survival times weregroups was04.3 to 5.3 months. When dogs that died or significantly longer for dogs receiving chemotherapy than for dogs treatedwere euthanatized because of myelosuppression were by amputation alone (P õ 0.0001). There was no significant difference inincluded in the survival analysis, there was no signifi- survival between dogs receiving chemotherapy beginning 2 days aftercant difference survival between treatment groups. surgery and dogs receiving chemotherapy beginning 10 days after surgery.

(P Å 0.727). Open marks: censored observations.DISCUSSIONThis study demonstrates that adjuvant chemotherapysignificantly prolongs the survival of dogs with sponta- Although studies conducted by the authors12 and

others11 using transplantable murine tumors have in-neous osteosarcoma. The survival data reported hereare similar to data reported elsewhere for dogs treated dicated that the response to adjuvant chemotherapy

may be improved by initiating chemotherapy duringwith cisplatin and/or doxorubicin.18–24 Although ap-proximately 60–65% of humans with osteosarcoma the early postoperative period, the timing of chemo-

therapy was not found to influence survival in the cur-treated with adjuvant chemotherapy survive withoutrecurrence,27 adjuvant chemotherapy rarely is curative rent study. This result is consistent with the results of

clinical trials investigating the value of early postoper-for canine osteosarcoma. This difference is likely dueto the less intensive nature of the chemotherapy pro- ative initiation of chemotherapy in the treatment of

human breast carcinoma.2,4 Because the current studytocols used for treatment of the canine disease.

/ 7b52$$0973 03-04-97 16:17:41 cana W: Cancer

1348 CANCER April 1, 1997 / Volume 79 / Number 7

was conducted using a spontaneous tumor of different that the changes observed in the growth kinetics ofmetastases after excision of experimental primary tu-histogenesis, arising in a different species, it provides

important additional evidence that early postoperative mors in mice occur to a lesser degree, or over a moreprotracted time course, after excision of spontaneousinitiation of chemotherapy is not of critical impor-

tance in the management of metastatic cancer. tumors in larger species. In these species, convention-ally timed chemotherapy may be appropriate from theThere are several possible explanations for the dif-

ference between the current study results and the re- standpoint of cell kinetics within metastases. The re-sults of the current study do not disprove the theorysults of earlier studies using experimental murine tu-

mors. In designing this study, the authors considered that removal of a primary tumor alters the growth ki-netics of metastases, but do imply that there is noboth the current knowledge of the growth kinetics of

metastases and the practicalities of clinical chemo- substantial advantage to early postoperative initiationof adjuvant chemotherapy for spontaneous tumors oftherapy administration. Postoperative Days 2 and 10

were selected for initiation of chemotherapy based on large species.Preoperative or neoadjuvant chemotherapy, usu-the observation that in mice, cell proliferation in me-

tastases appears to peak 2 or 3 days after resection of ally combined with continued chemotherapy after sur-gery, has become a standard practice in the treatmenta primary tumor, and returns to normal by 10 days.5,9

However, in the murine studies that have shown an of human osteosarcoma, and is being investigated inthe management of other human tumors, includingadvantage to early chemotherapy administration, che-

motherapy was initiated on the day of surgery.11,12 The breast carcinoma. The principal rationale for the pre-operative initiation of chemotherapy is to reduce theauthors believed that from a practical standpoint, ad-

ministration of combination chemotherapy prior to size of the primary tumor, potentially allowing lessradical surgery. In addition, preoperative chemother-the second postoperative day would be associated

with an unacceptable level of stress and discomfort for apy allows the earliest possible therapy for microme-tastases, because it eliminates the delay required forthe dogs. It also is possible that a significant difference

between groups would have been observed if initiation surgery and postoperative recovery. (However, in a re-cent randomized clinical trial conducted by the Pedi-of chemotherapy had been delayed beyond 10 days in

the group receiving conventionally timed chemother- atric Oncology Group, preoperative initiation of che-motherapy for osteosarcoma did not produce a detect-apy. A delay of 2–4 weeks would have more closely

simulated common practice in the treatment of hu- able improvement in disease free survival29). The effectof preoperative administration of chemotherapy onman tumors; however, the goal of the current study

was to test as rigorously as possible observations re- postsurgical alterations in the growth kinetics of me-tastases, and any potential implications for the timinggarding growth kinetics of metastases and timing of

chemotherapy that have been made using murine tu- of the reinstitution of chemotherapy after surgery,have not been thoroughly studied. In a murine mam-mors. Because the survival times of dogs with osteo-

sarcoma are relatively short, a delay that approached mary adenocarcinoma model, administration of che-motherapy 5–7 days prior to primary tumor removal4 weeks might have produced a difference in survival

between groups that was not strictly related to postop- completely prevented the postoperative increase incell proliferation within metastases.11 This observationerative alterations in the growth kinetics of metastases.

It also is possible that a difference between groups suggests that in patients receiving preoperative che-motherapy, early postoperative reinstitution of che-would have been apparent if chemotherapy had been

comprised exclusively of cell cycle-dependent drugs motherapy is unlikely to have an advantage over con-ventionally timed postoperative therapy.such as antimetabolites, because part of the rationale

for the early postoperative initiation of adjuvant ther- An unexpected finding was that after the first cycleof chemotherapy, the frequency of clinically apparentapy is to deliver chemotherapy during a period of max-

imal proliferation of metastatic cells. The use of doxo- myelosuppression in dogs receiving early chemother-apy was nearly twice that observed in dogs receivingrubicin and cisplatin may have slightly obscured a po-

tential difference in survival between groups because conventionally timed treatment. Although this differ-ence was not statistically significant, the lack of sig-both drugs are thought to have some activity against

noncycling cells.28 However, both drugs are most ac- nificance may have been related to sample size. Anincrease in the proliferation of immature granulocytestive against proliferating cells,28 and murine studies

demonstrating an advantage to early postoperative during the first few days after major surgery may haveincreased the risk of myelosuppression among dogsinitiation of chemotherapy have used either doxoru-

bin12 or cyclophosphamide,11 which has activity that receiving chemotherapy during this period. Althoughthere were no statistical differences in neutrophilis independent of the cell cycle.28 Finally, it is possible

/ 7b52$$0973 03-04-97 16:17:41 cana W: Cancer

Timing of Postoperative Chemotherapy/Berg et al. 1349

counts between treatment groups at 1 and 2 weeks advantage to the early postoperative initiation of adju-vant chemotherapy in the treatment of canine osteo-after the first chemotherapy treatment, nadir neutro-

phil counts were not determined. Primarily because sarcoma. In addition, the results of the current studysuggest that the initiation of chemotherapy within theof the difference in the frequency of myelosuppression

after the first cycle of chemotherapy, there was a larger first few days after major surgery may increase the riskof myelosuppression. Based on these results and thenumber of subsequent reductions in doxorubicin dose

among dogs receiving chemotherapy 2 days after sur- model of Goldie and Coldman,5 adjuvant chemother-apy should be initiated after a short delay adequate togery than among dogs receiving chemotherapy 10 days

after surgery; however, this difference was not of a allow patient recovery and early healing of the surgicalwound.magnitude likely to have significantly effected the out-

come of the study. An increased frequency of dosereductions after use of early postoperative chemother- REFERENCESapy also has been observed in the treatment of women 1. Nissen-Meyer R, Host H, Kjellgren K, Mansson B, Norin T.

Short perioperative versus long-term adjuvant chemother-with breast carcinoma.2

apy. Recent Res Cancer Res 1985;98:91–8.Consistent with previous reports,22,23 a significant2. Ludwig Breast Cancer Study Group. Combination adjuvantincrease in the proportion of treatment failures caused

chemotherapy for node-positive breast cancer: inadequacyby metastases to bone was observed among dogs re- of a single perioperative cycle. N Engl J Med 1988;319:677–ceiving adjuvant chemotherapy. The skeletal system 83.

3. Ludwig Breast Cancer Study Group. Prolonged disease-freealso has become a more common site of initial relapsesurvival after one course of perioperative adjuvant chemo-among humans receiving chemotherapy for osteosar-therapy for node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Medcoma.30,31 Although the cause of this phenomenon is1989;320:491–6.

unknown, it is possible that in patients whose pulmo- 4. Sertoli M, Pronzato P, Rubagotti A, Queirolo P, Catturichnary metastases respond well to chemotherapy, pro- A, Canavese G, et al. A randomized study of perioperative

chemotherapy in primary breast cancer. In: Salmon SE (edi-longed survival allows bone metastases to becometor). Adjuvant therapy of cancer. Philadelphia: W.B. Saun-clinically apparent. In dogs with osteosarcoma, accu-ders, 1990:196–203.rate determination of disease free survival (if defined

5. Goldie JH, Coldman AJ. A mathematic model for relatingas time until development of metastases detectable by the drug sensitivity of tumors to their spontaneous mutationclinical imaging tests) requires thoracic radiography rate. Cancer Treat Rep 1979;63:1727–33.

6. DeWys WD. Studies correlating the growth rate of a tumorand bone scintigraphy at regular intervals after treat-and its metastases and providing evidence for tumor-relatedment. Principally because treatment of clinically ap-systemic growth-retarding factors. Cancer Res 1972;32:374–parent metastases in any site is not practical in dogs,9.

these tests were not routinely performed in the current 7. Simpson-Herren L, Sanford AH, Holmquist JP. Effects of sur-study. gery on the cell kinetics of residual tumor. Cancer Treat Rep

1976;60:1749–60.This study illustrates the value of spontaneous an-8. Gunduz N, Fisher B, Saffer EA. Effect of surgical removalimal tumors in addressing questions regarding therapy

on the growth and kinetics of residual tumor. Cancer Resof human cancers. The best defined animal models of1979;39:3861–5.

human cancers are canine osteosarcoma and canine 9. Fisher B, Gunduz N, Saffer EA. Interrelation between tumormalignant lymphoma (an excellent model for high cell proliferation and 17-fluoresceinated estrone binding fol-

lowing primary tumor removal, radiation, cyclophospha-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma), although there aremide, or tamoxifen. Cancer Res 1983;43:5244–7.many other tumors of dogs and cats that closely re-

10. Gebhardt MC, Cheng EY, Roth YF, Litwak GJ, Taira K, Suitsemble human cancers. From a research perspective,HD, et al. Accelerated growth of a secondary tumor focus

the clearest advantage of these tumors over experi- after surgical resection of a primary murine osteosarcoma.mentally induced tumors is that they are naturally oc- Cell Tissue Kinetics 1988;21:60.

11. Fisher B, Gunduz N, Saffer EA. Influence of the interval be-curring. In addition, the incidence of many spontane-tween primary tumor removal and chemotherapy on kinet-ous animal tumors is high, allowing the accrual of largeics and growth of metastases. Cancer Res 1983;43:1488–92.case numbers in short periods of time. The natural

12. Bell RS, Roth YF, Gebhardt MC, Bell DF, Rosenberg AE, Man-histories for most animal tumors are well defined, and kin HJ, et al. Timing of chemotherapy and surgery in a mu-because these tumors tend to have more rapidly devel- rine osteosarcoma model. Cancer Res 1988;48:5538–8.

13. O’Reilly MS, Holmgren L, Shing Y, Chen C, Rosenthal RA,oping clinical courses than their human counterparts,Moses M, et al. Angiostatin: a novel angiogenesis inhibitorthe results of therapy can be evaluated more quickly.that mediates the suppression of metastases by a Lewis lungDespite these advantages, spontaneous cancers of ani-carcinoma. Cell 1994;79:315–28.

mals remain a largely untapped resource for clinical 14. Chen C, Parangi S, Tolentino MJ, Folkman J. A strategy toand basic research. discover circulating angiogenesis inhibitors generated by

human tumors. Cancer Res 1995;55:4230–3.In conclusion, this study did not demonstrate an

/ 7b52$$0973 03-04-97 16:17:41 cana W: Cancer

1350 CANCER April 1, 1997 / Volume 79 / Number 7

15. 24. Mauldin GN, Matus RE, Withrow SJ, Patnaik AK. CanineBrodey RS. The use of naturally occurring cancer in domesticosteosarcoma: treatment by amputation versus amputationanimals for research into human cancer: general considera-and adjuvant chemotherapy using doxorubicin and cis-tions and a review of canine skeletal osteosarcoma. Yale Jplatin. J Vet Int Med 1988;2:177–80.Biol Med 1979;52:345–61.

25. Forrest LJ, Dodge RK, Page RL, Heidner GL, McEntee MC,16. Brodey RS, Abt DA. Results of surgical treatment in 65 dogsNovotney CA, et al. Relationship between quantitative tu-with osteosarcoma. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1976;168:1032–5.mor scintigraphy and time to metastasis in dogs with osteo-17. Spodnick GJ, Berg J, Rand WM, Schelling SH, Cuoto G, Har-sarcoma. J Nucl Med 1992;33:1542–7.vey HJ, et al. Prognosis for dogs with appendicular osteosar-

26. Ogilvie GK, Krawiec DR, Gelberg HB, Twardock AR, Reschkecoma treated by amputation alone: 162 cases (1978–1988).RW, Richardson BC. Evaluation of a short-term diuresis pro-J Am Vet Med Assoc 1992;200:995–9.tocol for the administration of cisplatin. Am J Vet Res18. Shapiro W, Fossum TW, Kitchell BE, Couto CG, Theilen GH.1988;49:1076–8.Use of cisplatin for treatment of appendicular osteosarcoma

27. Malawer MM, Link MP, Donaldson SS. Sarcomas of bone.in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1988;192:507–11.In: DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer:19. Kraegel SA, Madewell BR, Simonson E, Gregory CR. Osteo-principles and practice of oncology. 4th edition. Philadel-genic sarcoma and cisplatin chemotherapy in dogs: 16 casesphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1993:1509–66.(1986–1989). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1991;199:1057–9.

28. Cooper MR, Cooper MR. Principles of medical oncology. In:20. Straw RC, Withrow SJ, Richter SL, Powers BE, Klein MK,

Holleb Al, Fink DI, Murphy GP, editors. American CancerPostorino NC, et al. Amputation and cisplatin for treatment Society textbook of clinical oncology. Atlanta: Americanof canine osteosarcoma. J Vet Int Med 1991;5:205–10. Cancer Society, 1991:47–68.

21. Thompson JP, Fugent MJ. Evaluation of survival times after 29. Goorin A, Baker A, Gleser P, Ayala A, Gebhardt M, Harris M,limb amputation, with and without subsequent administra- et al. No evidence for improved event free survival withtion of cisplatin, for treatment of appendicular osteosar- presurgical chemotherapy for non-metastatic extremity os-coma in dogs: 30 cases (1979–1990). J Am Vet Med Assoc teogenic sarcoma: preliminary results of randomized pediat-1992;200:531–3. ric Oncology Group trial 8651. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol

22. Berg J, Weinstein MJ, Schelling SH, Rand WM. Treatment of 1995;14:444.dogs with osteosarcoma by administration of cisplatin after 30. Goldstein H, McNeil BJ, Zufall E, Jaffe N, Treves S. Changingamputation or limb-sparing surgery: 22 cases (1987–1990). indications for bone scintigraphy in patients with osteosar-J Am Vet Med Assoc 1992;200:2005–8. coma. Radiology 1980;135:177–80.

23. Berg J, Weinstein MJ, Springfield DS, Rand WM. Results of 31. Jaffe N, Smith E, Abelson H, Frei E. Osteogenic sarcoma:surgery and doxorubicin chemotherapy in dogs with osteo- alterations in the pattern of pulmonary metastases with ad-

juvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 1983;1:251–4.sarcoma. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1995;206:1555–60.

/ 7b52$$0973 03-04-97 16:17:41 cana W: Cancer

![· Web viewIn general treatment options are similar to pancreatic cancer (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy) [18]. Treatment of osteosarcoma in many cases requires amputation,](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/5e5d423808931055f4741480/web-view-in-general-treatment-options-are-similar-to-pancreatic-cancer-surgery.jpg)