Effect of instruction on ESL students’ synthesis writing

Transcript of Effect of instruction on ESL students’ synthesis writing

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

Journal of Second Language Writing 22 (2013) 51–67

Effect of instruction on ESL students’ synthesis writing

Cui Zhang *

Eastern Kentucky University, Department of English and Theatre, 521 Lancaster Avenue, Richmond, KY 40475, United States

Abstract

Synthesis writing has become the focus of much greater attention in the past 10 years in L2 EAP contexts. However, research on

L2 synthesis writing has been limited, especially with respect to treatment studies that relate writing instruction to the development

of synthesis writing abilities. To address this research gap, the present study examines the effect of instruction on ESL students’

synthesis writing. Participants were from two intact ESL classes; one class was randomly chosen to be experimental and the other

the control. During a one-semester treatment, the experimental group received five iterations of discourse synthesis instruction

while the control group worked on a comparable amount of reading and writing practice. Students’ discourse synthesis skills were

measured by pre- and post-tests, for which they wrote problem-solution essays using two source texts. Results showed that (1) the

experimental group performed significantly better at the post-test and (2) the experimental group improved significantly more from

pre-test to post-test than the control group. These results suggest a positive effect of instruction on discourse synthesis writing. More

importantly, the study demonstrates the feasibility of incorporating synthesis writing instruction into an ESL course without

significantly disrupting the curriculum.

Published by Elsevier Inc.

Keywords: Discourse synthesis; ESL; L2 writing; Reading writing instruction; Writing from sources

Introduction

Research on the frequently required types of writing tasks in university academic contexts has shown that most

writing depends on reading input to a large extent—either directly from source texts, or indirectly from background

knowledge, which itself results from experience with texts (Bridgeman & Carson, 1984; Hale et al., 1996; Horowitz,

1986; Zhu, 2004). This practice reflects the greater importance given to critical writing skills in contexts in which

academic writing is a crucial part of academic success (Leki & Carson, 1997; Rosenfeld, Leung, & Oltman, 2001).

One common type of reading-based writing in this setting is the discourse synthesis, which involves the integration of

information from multiple sources. The discourse synthesis (e.g., in-class or take-home essay exams, research papers,

and various writing-from-sources tasks) is a widely required academic genre; it not only involves reading and writing

(and students’ accountability for correct representation and integration of content information) but also is expected to

enhance students’ critical thinking ability (McGinley, 1992).

Because a discourse synthesis taps into a writer’s reading, writing, and critical thinking abilities, it is a difficult

task for students to perform. In an analysis of synthesis essays completed by 45 students from four educational

levels in Spain (first and third year middle school, high school, and university), Mateos and Sole (2009) painted a

* Tel.: +1 8596223177.

E-mail address: [email protected].

1060-3743/$ – see front matter. Published by Elsevier Inc.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2012.12.001

C. Zhang / Journal of Second Language Writing 22 (2013) 51–6752

stark picture: the majority of the student essays illustrated poor comprehension of source texts and/or lack of

integration, thus they were not successful syntheses. Synthesis writing was even challenging for university

students, because only two out of the 11 university student essays were judged, according to the researchers’

criteria, as successful syntheses.

Several studies have looked into the composing process of discourse syntheses and have identified factors that

contribute to task difficulty: degree of writer’s topic familiarity, level of writer’s reading ability, difficulty of source

texts, complexity of relationship between texts, and type of discourse synthesis required (Risemberg, 1996; Spivey,

1997; Spivey & King, 1989; Wiley & Voss, 1999). When second language (L2) learners were the focus group, further

factors—including L2 proficiency level, previous experience with task, and first language (L1) reading and writing

ability—may also come into play in their discourse synthesis writing (Plakans, 2009a, 2009b). However, we still do

not know if instruction has a positive effect on L2 students’ ability to write discourse synthesis essays.

Effective instruction in synthesis writing is needed in the English for Academic Purpose (EAP) context. Students

graduating from EAP programs have said that they wanted to have learned discourse synthesis writing better to

successfully fulfill their content courses’ writing requirements (Leki & Carson, 1994). Plakans (2010) analyzed

English as a second language (ESL) students’ task representation for synthesis and independent writing tasks and

found that over half of the participants did not interpret the two tasks as different types. She suggested that EAP

teachers should guide students ‘‘in the synthesis writing process, including strategies to comprehend, select from, and

integrate reading with writing’’ (p. 193). These studies indicate that synthesis writing instruction would greatly benefit

ESL students in university contexts. However, research that investigates instructional effects on ESL students’

synthesis writing has not yet been conducted. For this reason, this study investigates, with the ultimate goal of

providing pedagogical implications, whether classroom instruction can have a positive effect on ESL students’

discourse synthesis quality after one semester.

In the sections that follow, previous literature on discourse synthesis writing is reviewed, as it provided the

foundation for identifying important elements in discourse synthesis in both first and second language writing.

Research on students writing discourse syntheses in their L1 is first discussed, focusing on Spivey’s (1997) model of

discourse synthesis because it provided the framework for the present study. Next, relevant descriptive studies on

synthesis writing in L2 are reviewed, followed by the close analysis of three L1 instructional studies of synthesis

writing that informed the present study.

Discourse synthesis research in L1

In English L1 writing contexts, Spivey (1990, 1997) has proposed a constructivist model of discourse synthesis that

features three central operations for the construction of meaning from multiple texts in the composing process:

organizing, selecting, and connecting. Because writers have to take on roles of both reader and writer, each of the three

operations works under two conditions: meaning construction and textual transformation. In both the meaning

construction and textual transformation processes, the writer consciously or unconsciously integrates the immediate

source texts and previously acquired knowledge. In the meaning construction process, the reader (a) uses previously

acquired knowledge on the topic to facilitate reading comprehension, (b) organizes mental information to reflect

information selected from the texts, and (c) connects the pieces of information he/she generates from different texts.

When composing, the writer (a) performs textual transformations to organize selected information from the texts and

(b) connects this information in a way that is appropriate for the task environment.

In two studies of university-level students’ discourse syntheses, Spivey (1997) found that the students’ selecting,

organizing, and connecting operations during the writing process were closely related to their synthesis essay quality.

In one study, Spivey examined synthesis essays written by 40 upper-level undergraduate students based on three

informational texts on a single topic. The other study involved 30 undergraduate students writing comparison synthesis

essays based on two source texts. Both studies showed that: (1) students selected important information from source

texts to include in their essays and (2) the quality of the essays were closely linked to essay organization, connection of

information, and comprehensiveness.

Other English L1 studies of synthesis writing have also indicated the importance of reading ability to students’

synthesis writing quality. One study conducted by Spivey and King (1989) with accomplished and weaker readers

from sixth, eighth, and tenth grade levels showed that the better readers were able to include more idea units and

illustrate deeper understanding of the source texts in their synthesis essays. Another study conducted by Risemberg

C. Zhang / Journal of Second Language Writing 22 (2013) 51–67 53

(1996) with 71 college freshmen suggested that students’ reading ability (together with task-information seeking

skills) was a unique contributor to their synthesis writing quality.

Discourse synthesis research in L2

In the L2 context, many researchers have studied ESL or English as a foreign language (EFL) students’ writing

from sources. Most studies focused on the students’ use of source texts, such as university-level students’ text-

borrowing behaviors and the functions they served in writing-from-sources tasks, surveyed university instructors’

attitudes toward students’ text appropriation, and identified multiple factors influencing students’ textual

appropriations (Plakans & Gebril, 2012; Shi, 2006, 2010, 2011). In some other studies, researchers have examined

the effect of instruction on ESL students’ use of sources (Wette, 2010). This research of students’ text borrowing

practices and instructional effects on the use of source texts is important in understanding and improving ESL/EFL

students’ writing from sources.

The other strand of research on ESL students’ writing from sources looked into students’ composing processes and

factors influencing the written product. Recently, Plakans (2008, 2009a, 2009b) has published several studies that

analyzed the composing process and written product of 12 ESL students’ discourse syntheses. The students had

different L1s, English proficiency levels, major fields of study, and academic status (pre-university, undergraduate, and

graduate). The students wrote one independent task and one synthesis task from two source texts while thinking aloud,

and their essays were scored by a holistic rubric modified from the TOEFL iBT integrated scoring rubric. Comparison

between these ESL students’ writing processes for independent and synthesis writing tasks showed that synthesis

writing required more interaction in reading and writing (Plakans, 2008).

ESL students’ think-aloud protocols during their synthesis writing processes revealed that: (1) the students’ essay

quality was influenced by their overall reading comprehension ability as well as two specific reading strategies—

global strategies (e.g., goal setting) and mining strategies (i.e., purposefully looking for useful information from the

source texts) (Plakans, 2009a); (2) the students used organizing, selecting, and connecting operations in their writing

processes; and (3) students’ English proficiency and experience with this type of synthesis task influenced their

synthesis essay quality (Plakans, 2009b). In addition, relationships among source texts and task type (informative vs.

argumentative) influenced the ESL students’ organizing decisions and use of source text information in the synthesis

writing process and product (Shi, 2004; Zhu, 2005).

As Spivey’s constructivist model and the above discussed studies suggest, many reading and writing operations are

involved in the discourse synthesis writing process, and because of this, factors such as reading ability, L2 proficiency,

and type of task could influence synthesis writing process and product. Without measuring or controlling these factors

in the research design, it is difficult to determine L2 students’ abilities to perform synthesis tasks. More importantly, as

Hirvela (2004) noted, academic writing that incorporates information from source texts requires that a student know

how to locate and identify relevant information in the reading and then incorporate it into the writing. Thus, it is

important to identify effective instructional methods that will help students locate, connect, and integrate information

from source texts in their writing.

Instructional studies of synthesis writing

While many researchers have emphasized the need for synthesis writing instruction, only three recent studies have

explored the effect of explicit instruction on adult learners’ discourse synthesis writing, all of which involved students

writing synthesis essays in their L1. Boscolo, Arfe, and Quarisa (2007) examined the effect of explicit instruction on

52 undergraduate university students’ discourse synthesis writing quality. In this study, intervention was provided

through ten sessions of after-class discourse synthesis workshops. During the intervention, students listened to

lectures, practiced writing, received teacher feedback, and discussed examples of good and bad synthesis writing.

Students’ pre-test and post-test synthesis essays were assessed from three perspectives: informativeness (selection of

information), integration (connection of information from source texts), and organization (cohesion and text

structure). Results from t-tests showed a significant improvement from pre-test to post-test in all the measures except

integration, suggesting an overall positive effect of instruction on students’ synthesis writing.

Segev-Miller (2004) conducted an intervention study with 24 elementary education in-service teachers for one

semester. They were assigned a literature review task at the beginning and the end of the semester. Instructional

C. Zhang / Journal of Second Language Writing 22 (2013) 51–6754

activities for these participants included presentations, explanations, demonstrations, and practice with strategy use for

source text processing and writing, as well as written product evaluations using a set of assessment criteria that were

essential for discourse synthesis tasks and academic writing. Using the same set of assessment criteria, the participants

self-assessed their literature reviews written at the end of the semester as significantly better than those written at the

beginning of the semester. Aside from showing the effect of instruction, this study demonstrated the importance of

modeling strategy use and communicating assessment criteria to students in classroom instruction.

The third study on instruction and L1 synthesis writing included students from secondary schools and was the only

study that included a control group (Kirkpatrick & Klein, 2009). The researchers compared the effect of three-week

instruction on 7th and 8th graders’ compare-contrast synthesis essays with a control group. During the instruction (six

lessons), experimental students received explicit instruction on compare-contrast structure, practiced using a planning

table to organize source text information, and wrote synthesis essays. During the three weeks, control students received

standard writing instruction their teachers had planned. All students completed a pre-test and a post-test, for which they

wrote compare-contrast essays on two counter-balanced topics. Results showed that the experimental students’ post-test

essays were better than the control students’ essays in both overall quality and text structure, but their text structure

improvement did not meet the researchers’ expectation. This study suggested the importance of using a planning tool to

help students select, organize, and connect information from source texts. However, the instructional time was relatively

short, during which the experimental students only wrote one teacher-guided essay and one practice essay; had the

instruction lasted longer, students could have made larger improvement in their synthesis essays’ structure.

The three instructional studies discussed above suggest a positive effect of instruction on the participants’ synthesis

writing quality and understanding of task requirements. It is important to note that in both studies the instruction of

synthesis writing comprised explicit explanation of synthesis writing, modeling/demonstrations, practice, and teacher

feedback/evaluation. As Tardy’s (2006) review of research in genre learning suggests, experience and practice play an

important role in genre learning for both L1 and L2 writers. Linking student practice with explicit instruction, then, is

seen as a crucial component in the current study. As more English L2 students work in English-medium universities,

there is a greater need to prepare them for academic success. Thus, it is important to examine the extent to which

students can be taught, with ample practice, to improve their synthesis writing skills.

The present study was designed specifically to investigate the extent to which classroom instruction, including practice,

can improve intermediate-level L2 writers’ discourse synthesis essays over a semester. Drawing from the constructivist

theory proposed by Spivey (1997), the instructional activities focused on students’ selecting and connecting of source text

information in reading and writing processes. A pre-test/post-test design was used to detect whether students improved in

synthesis writing after the semester-long instruction. Two research questions guided the present study:

1. D

oes the quality of intermediate ESL students’ synthesis essays improve after one semester’s instruction?2. W

hat is the effect of instruction on intermediate ESL students’ overall synthesis essay quality compared to thestudents who did not receive instruction?

Method

Research setting

The study was conducted in an intensive English program (IEP) at a U.S. university. At the time of study, there were

around 190 students studying at five different levels in the IEP. Depending on their level of study, students in the program

took 24–26 hours of English instruction per week, including skills courses (reading and writing, listening and speaking),

skills-support course (reading lab), content based instruction (CBI), computer assisted language learning (CALL), and

electives in language improvement (ELI). The IEP developed its own placement and exit examinations modeled after the

TOEFL iBT test, which were administered at the beginning and the end of each semester. Based on their course grades

and placement/exit exam scores, students would be promoted to the next highest level or exit the IEP.

Participants

Participants for the study were students from two Level 4 classes in the IEP. Based on their placement exam scores

and instructional level, the students’ English proficiency could be categorized as intermediate (approximately 53–62

C. Zhang / Journal of Second Language Writing 22 (2013) 51–67 55

TOEFL iBT score range). In the semester of study, students took 26 hours of instruction per week, including 6 hours of

Reading and Writing, 6 hours of Listening and Speaking, 8 hours of CBI, 2 hours of Reading Lab, 2 hours of CALL,

and 2 hours of ELI.

Participants for the study included new incoming international students and students who were promoted from a

lower level. The initial 44 students were randomly assigned to two classes using a research randomizer (Perry, 2011).

Independent samples t-test showed no significant difference in either the two groups’ overall English proficiency

(placement exam scores) or their reading/writing ability (combined Reading and Writing section scores from the

placement exam). One class was randomly assigned to be the experimental class and the other the control. I was the

Reading and Writing course instructor for both classes. To prevent researcher’s bias toward the experimental group, I

kept teaching journals that recorded my teaching activities, student participation, and content coverage for each class

taught. I also constantly checked the journals against my lesson plans to ensure that the two classes received the same

quality and amount of instruction.

Due to students’ attrition during the semester and incomplete participation in data collection, the final number of

participants was 14 students for the experimental group and 15 students for the control group. There were seven female

students in each group. The experimental group was comprised of six Arabic and eight Chinese L1 speakers. The

control group had four Arabic, nine Chinese, one Japanese, and one Spanish L1 speakers. There was no significant

difference between the two participating groups in their overall English proficiency (t = .907, p = .372) or English

reading and writing ability (t = .608, p = .548).

Materials

Materials for the study included both instructional materials and pre-test/post-test materials. For the experimental

group, five iterations of discourse synthesis writing instruction were integrated into the existing course curriculum,

which was built upon reading, writing, and vocabulary instruction from two textbooks. For the control group, an

equivalent amount of reading and writing practice in writing other than discourse syntheses was integrated into the

same curriculum. The identical instructional materials for both classes, as well as materials for each class, are

described as follows.

Instructional materials

Two textbooks were required for the Reading and Writing course: NorthStar reading and writing 4 (2nd ed.) edited

by English and English (2009) and Vocabulary power 2 (Dingle & Lebedev, 2007). Students in both classes received

the majority of content instruction from these two textbooks. Reading texts in the NorthStar textbook were of several

different genres: narrative, expository, argumentative, and fiction. Two of the writing tasks required for the two groups

were the same: one response essay at the beginning of the semester and one argumentative essay at the end of the

semester. Each unit of the Vocabulary power textbook included 10 vocabulary words, one reading to present the words

in context, and various vocabulary exercises. Students in both classes were also provided with short readings (300–500

words) selected from other books appropriate to their level for in-class timed and speed-reading activities.

In addition to the reading and writing tasks used in both classes, five sets of discourse synthesis instructional

materials were developed particularly for the experimental group. These materials included five pairs of

supplementary reading texts, reading guides that accompanied these texts, five writing prompts, connections exercises,

and two analytic scoring rubrics. The reading texts were found from the Internet; their themes matched to five units in

the NorthStar textbook, and they were modified to meet the students’ reading level in terms of length, readability level,

and vocabulary profile. Table 1 illustrates characteristics of the supplementary texts. A reading guide was also created

for each text to facilitate students’ understanding, including questions on author and title of a text, prediction of

content of the text, and main ideas and organization of the text, as well as reflections on the reading based on their

existing knowledge on the topic. Based on the relationship between the two texts in each set, a connection exercise was

created to help students make connections between the two readings. Informative and problem-solution types of

writing prompts were created for the writing tasks. Analytic scoring rubrics were developed to provide feedback to

students on essay structure, rhetorical pattern, content, use of source texts, and language.

Because five sets of synthesis writing instruction materials additional to the textbook were provided to experimental

students, to ensure that students in the two classes were exposed to similar amounts of reading and writing, students in

the control group were engaged in web-based reading. The web-based readings were found by the students on themes

C. Zhang / Journal of Second Language Writing 22 (2013) 51–6756

Table 1

Instructional texts description.

Text Unit Topic Length

(words)

Readability

(Flesh-Kincaid)

Vocabulary profile

K1 + K2 (%) AWL (%)

Set 1

Laughter may be the best medicine 3 Positive thinking 335 Grade 10.4 85.96 3.51

Power of positive thinking 3 Positive thinking 394 Grade 10.7 84.34 8.33

Set 2

The study of animal intelligence 4 Animal intelligence 269 Grade 11.7 85.92 10.11

Animal mind 4 Animal intelligence 430 Grade 8.5 83.14 5.69

Set 3

Why service-learning is bad 6 Service Learning 384 Grade 11.9 89.00 7.00

How to make service-learning work 6 Service learning 388 Grade 11.9 86.35 9.93

Set 4

Why some people are against

home schooling

7 Home Schooling 402 Grade 9.4 90.84 4.46

Make homeschooling work:

problems to address

7 Home schooling 465 Grade 10.3 88.37 4.65

Set 5

New study links fast food to

increased weight

8 Fast food 308 Grade 9.4 84.71 6.05

Exploring healthier fast food choices 8 Fast food 336 Grade 9.2 85.13 1.46

related to the textbook units, and were the bases for class discussion and writing. Writing prompts from the NorthStar

textbook and other sources were used for students’ writing practice. The types of writing students in the control group

practiced included cause-effect, problem-solution, explanation, and argument.

Pre- and post-test materials

Materials designed for the pre- and post-tests included two sets of reading texts, two sets of writing instructions, and

a holistic scoring rubric. The type of discourse synthesis pattern used was problem-solution because of its prevalence

in the university setting. To avoid an assessment practice effect, two writing topics and accompanying reading texts

were designed for the pre- and post-tests: study abroad and global warming. Both sets of reading texts were designed at

the students’ reading level, including length of text, Flesh-Kincaid grade level, and vocabulary profile (see Table 2).

The source texts and writing prompt on study abroad are presented in Appendix A. To measure students’ overall

discourse synthesis writing quality, a holistic scoring rubric (Appendix B) was adapted from Plakans’ (2009a) holistic

rubric for argumentative synthesis. While Plakans’ (2009a) rubric measures students’ ability to integrate information

from source texts to support their arguments, the holistic rubric for the present study evaluates the overall quality of

students’ problem-solution synthesis essays.

Table 2

Pre-test and Post-test Reading Texts.

Text title Topic Length

(words)

Readability

(Flesh-Kincaid)

Vocabulary Profile

K1 + K2 (%) AWL (%)

Pre/post test set 1

International students experience culture

shock in colleges abroad

Study abroad 423 Grade 11.0 84.17 8.00

How to survive as an international student Study abroad 498 Grade 9.9 88.80 7.80

Pre/post test set 2

Consequences of global warming Global warming 467 Grade 10.9 84.57 4.86

How going green can reduce global warming Global warming 430 Grade 10.0 80.83 9.47

C. Zhang / Journal of Second Language Writing 22 (2013) 51–67 57

Procedure

At the beginning of the semester, students in both classes were invited to participate in a study to examine the effects

of instruction on second language writing, which would involve the collection and analysis of their in-class writings

and interviews. Because some students chose not to participate in the study, to make sure all students were treated the

same, the pre- and post-tests were built into the course syllabus to be counted toward all students’ in-class writing

grade. Only essays written by participating students were included in the present analysis.

The pre-test was administered early in week two when students in the two classes had their Reading and Writing

class on the same day. In each class, packets for the study abroad topic were given to half of the students at random, and

the other students received the global warming topic. In each packet there were two reading texts, one set of writing

instructions, and lined blank paper. Students were told that they could use the entire class time (2 hours) to complete

the task. The whole packet was collected upon each student’s completion of the task.

During the semester, students in both classes received reading and writing instruction based on the two required

textbooks. Eight units from the NorthStar textbook and ten units from the Vocabulary textbook were covered in the

semester. Students received instruction from the two textbooks on reading, vocabulary, and grammar. Students also

received the same instruction in general essay structure, essay prompt analysis, summary writing, citation (quotation

and paraphrasing), library research, and rhetorical patterns of different types of essays. The only difference in

instruction between the two classes was whether there was instruction on (and therefore practice in) synthesis writing.

Table 3 illustrates the same and different instructional activities between the experimental and the control classes in

reading and writing.

In addition to the textbook content, students in the experimental class received five cycles of synthesis writing

instruction. For each synthesis writing cycle that took place after finishing a NorthStar textbook unit, they were given

two reading texts related to the unit theme and reading guides as homework. During the next class, they participated in

small-group and teacher-guided whole-class discussions of the texts focusing on the identification of textual structure,

main ideas, and details. The group and teacher-guided discussions also included connecting the two texts (using the

connection exercise) by selecting important information from texts and connecting different pieces of information to

fulfill the requirement of the informative and problem-solution types of synthesis essay. For the informative syntheses,

they were guided to find common ideas or important complementary ideas from the two texts and integrate the ideas

together to explain the topic. For the problem-solution syntheses, they were guided to find problems and solutions from

the texts and match the solutions to the problems. They were then given the essay assignment as homework or as an in-

class writing activity; drafted their essays; did peer review on essay format and structure (for essays completed out of

Table 3

Instructional activities for experimental and control classes.

Type of activity Experimental class Control class

Reading activities Textbook readings from eight units Textbook readings from eight units

Timed and speed readings Timed and speed readings

Supplementary reading texts for synthesis tasks Student-selected web-based reading texts

from the Internet

Writing activities Summarizing and paraphrasing exercises Summarizing and paraphrasing exercises

Response essay (2–3 pages) Response essay (2–3 pages)

Informative synthesis (1–2 pages) Opinion essay based on textbook reading

(textbook prompt) (1–2 pages)

Informative synthesis (1–2 pages) Informative essay based on textbook reading

(textbook prompt) (2–3 pages)

Problem-solution synthesis (1–2 pages) Cause-effect essay using information from 2

source texts (2–3 pages)

Problem-solution synthesis (2–3 pages)

Problem-solution synthesis (1–2 pages) Problem-solution essay using information from

web-based reading texts (1–2 pages)

Argumentative essay using information from

multiple source texts (4–6 pages)

Argumentative essay using information from

multiple source texts (4–6 pages)

C. Zhang / Journal of Second Language Writing 22 (2013) 51–6758

class); received instructor’s comments on organization, use of source text, and language; revised their essays; and

received scores and comments on their final drafts.

While students in the experimental class worked on synthesis reading and writing activities, students in the control

group worked on a similar amount of reading and writing practice in other genres/essay forms. They were directed to

do web-based research and find articles published on the Internet that were closely related to the textbook unit topics.

The articles that they found were used as reading materials, resources for class discussion, and (on one occasion)

sources for writing. They wrote essays of various types, including a response essay, an informative essay, an

argumentation essay, a cause and effect essay, and a problem-solution essay. All of the essays were reading-based, and

most essay topics were related to the unit themes of the NorthStar textbook. The problem-solution type of essay was

introduced to the control group to minimize the possible influence of essay type familiarity on the pre- and post-test

results.

The post-test was administered in week 15 during one Reading and Writing class. At the post-test, students worked

on the topic they did not work on for the pre-test. The test administration procedure was the same as the pre-test, and

only essays from participating students were transcribed for analysis.

Data coding and analysis

Participating students’ pre- and post-test essays from both classes were typed up using Notepad. This was done to

avoid the possible influence of students’ hand-writing on the scoring process. During the transcription process, the

student essays were kept the same as the original (including essay structure and organization, spelling, capitalization,

punctuation, etc.). Two raters (other than the researcher) scored the essays using the holistic scoring rubric in two

scoring sessions within two weeks. During the norming sessions prior to scoring, the two raters were given the source

texts, writing prompts, and sample essays to score and discuss. After the scoring process, they cross-checked their

scores and discussed their scoring decisions when they had score differences of more than one point. Pearson

correlation analysis showed that the two raters’ inter-rater reliability was high for the first scoring session (r = .881,

p < .05) and was moderate for the second scoring session (r = .704, p < .05). Each essay received an average score

computed from the two raters’ scores.

To answer research question one, a paired-samples t-test was run for the experimental group’s pre-test and post-test

essay scores to detect whether there was a significant difference. To answer research question two, descriptive statistics

were calculated for each of the two groups at pre-test. Because of the small number of participants and small difference

between the two groups at pre-test, gained scores from pre-test to post-test were computed for each student, and an

independent samples t-test was run between these two sets of scores to detect whether there was significant difference

between the two groups for the students’ gained scores. In both cases, if there was a significant difference, Cohen’s d

was computed for effect size using each group’s mean score and standard deviation (SD).

Results and discussion

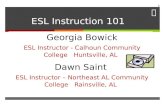

Table 4 shows the descriptive statistics for the two groups at the two testing times. Fig. 1 provides a visual

representation of the mean holistic scores for the two groups’ pre- and post-test essays. Both Table 4 and Fig. 1 illustrate

that the two groups were similar in terms of their holistic scores at the time of pre-test, and both groups increased their

essay scores at post-test, but the experimental group was able to improve their mean score more at post-test.

To answer the first research question, a paired samples t-test was run to detect whether the difference between the

experimental groups’ pre-test and post-test scores were significant. Result showed a significant difference between the

Table 4

Descriptive statistics.

Group N Pre-test Post-test

M SD M SD

Experimental 14 2.29 .87 3.89 .66

Control 15 2.57 .62 3.17 .65

C. Zhang / Journal of Second Language Writing 22 (2013) 51–67 59

Fig. 1. Effectiveness of instruction overtime.

pre-test and post-test scores (t = 6.663, p = .000). To detect the effect size of this difference, Cohen’s d was computed

using the mean score and standard deviations, and the result showed a large effect size (d = 2.08). This means that at

post-test, the students on average improved their writing quality by 1.6 points on a 6-point scoring scale. A paired

samples t-test indicated that this was a significant improvement over the semester. More specifically, students who

received instruction and practiced discourse synthesis essays were able to perform better in the problem-solution type

of synthesis writing at the end of the semester.

This result was congruent with previous studies on instructional effects of synthesis writing with L1 students by

Segev-Miller (2004) and Boscolo et al. (2007). In Segev-Miller’s (2004) study, the participants self-assessed that their

writing improved with respect to the type of discourse synthesis they received instruction on, namely the literature

review. Students in the Boscolo et al.’s (2007) study improved in their ability to write argumentative discourse

syntheses. The finding of the present study also adds to the research on the instructional effects of discourse synthesis

writing. This study showed that instruction in discourse synthesis writing could improve L2 students’ synthesis writing

even though their English still needed improvement (as the participants were studying in an IEP). It is clear that, with

instruction, students at an intermediate English proficiency level were able to improve their quality with one

commonly recurring type of essay—a problem-solution synthesis. However, whether instruction on other types of

discourse synthesis writing produces a similar effect still needs further research.

The second research question investigated whether the improvement in the experimental group’s discourse

syntheses could be attributed to synthesis writing instruction. To answer this question, descriptive statistics were

computed for the gained scores from pre-test to post-test for both groups. Results showed students in the experimental

group (M = 1.61, SD = .90) on average improved more over the semester than the students in the control group

(M = .60, SD = .47). Independent samples t-test indicated that this difference in gained scores between the two groups

was significant (t = 3.73, p = .001), and the effect size was large (Cohen’s d = 1.41). This means that the two groups

started at a similar point, with the control group’s average essay score slightly higher than the experimental group’s

score at pre-test. At the end of the semester, both groups were able to improve in their discourse synthesis writing;

however, students in the experimental group improved their scores to a much larger extent. Independent samples t-test

indicated the difference between the two groups’ pre-to-post gain scores was significant, and the difference was large

enough for it to be reasonably attributed to instruction. Because students in both classes had a six-hour Reading and

Writing course per week, the improvement made by students in the control group could be attributed to improvement

in overall reading and writing abilities, while students in the experimental group were able to perform better

specifically on discourse synthesis tasks due to classroom instruction and practice. This result is similar to that of

Kirkpatrick and Klein (2009) in that the experimental group received higher overall essay scores than the control

group. Results from both the current study and Kirkpatrick and Klein’s (2009) study suggest that improvement in

students’ discourse synthesis essay quality is indeed the result of focused instruction, including repeated practice in

synthesis writing.

To provide more concrete information on the experimental and control group students’ synthesis writing, three

sample student essays were closely examined. The three aspects important for synthesis writing—selecting,

connecting, and organizing—were the focus of the examination of these essays. To make the comparison more

C. Zhang / Journal of Second Language Writing 22 (2013) 51–6760

straightforward, all three essays selected were based on the Study Abroad topic (source texts and essay prompt

provided in Appendix A). One essay was written by the experimental group student at pre-test (Appendix C), one was

written by a control group student at post-test (Appendix D), and the third was written by an experimental group

student at post-test (Appendix E). These essays were selected because they represent the control and experimental

group students’ synthesis essay mid-group performance at the two test times.

The pre-test essays from all students generally fall into two categories: they either rely heavily on one source text or

simply neglect both source texts. Appendix C represents the first type and is a sample essay written by an experimental

group student at the time of pre-test. As the sample illustrates, the essay is on topic and discusses problems and

solutions of studying abroad in the U.S. Also, the student uses some information (although not a lot) from the source

texts, especially in the second paragraph when the student writes about problems of studying abroad. However, no

citation is provided despite the paraphrases and many exact phrases directly copied from the source texts. In terms of

connections, the student does not illustrate his/her understanding of the relationships between the two source texts.

When the student discusses the problem of culture shock, he/she does not provide solutions to solve this problem, but

some of the solutions from the source texts are used in a later paragraph that discusses adapting to the new culture. In

general, the student writes the essay in a problem-solution pattern but does not select important ideas from the source

texts to discuss problems and solutions of studying abroad, nor does the student organize the information in a logical

order.

Appendix D is a sample essay written by a student from the control group at post-test. The student recognizes that

the essay required the discussion of problems (and maybe solutions) of studying abroad, and the student does stay on

topic. The student’s essay employs the point-by-point organizational pattern, which provides a solution immediately

following the discussion of a problem before moving on to the next problem. Compared to the pre-test essay in

Appendix C, this essay utilizes more information from the source text, including identifying the two major problems

(culture shock and difficulty in making friends) and providing detailed discussion of each problem with some citations.

However, the student provides simple solutions based on his/her understanding of the problem, rather than using

information from the other source text. The student suggests that, to deal with culture shock, international students

need ‘‘to be hard on them self [. . .], and they will be better after a while,’’ and for making friends, the students should

‘‘look for student from their country.’’ This essay uses more information from the source texts compared to the pre-test

essay, but the student only uses information from one article, indicating a lack of understanding of the connection

between the two source texts. In addition, even though all students did citation exercises and practiced using citation in

their essays during the semester, there is still direct text copying in this essay, which is a common problem in ESL

students’ essays when textual citation is required. Overall, this essay is stronger than the student’s pre-test essay in

terms of selecting and citing information from one source text, but it fails to make connections between the two source

texts.

Appendix E is an essay written by a student in the experimental group at post-test. This essay employs a block

organizational pattern for problem-solution essays, which is all problems-transition-all solutions. It is worth noting,

however, that some other students used the point-by-point organizational pattern which is illustrated in Appendix D. In

this essay, the student discusses the problems and solutions of studying abroad in detail, using information from the

source texts to support his/her main ideas. As the essay illustrates, the student selects important pieces of information

from the source texts. For example, with the discussion of the problem of difficulty in making friends, the student is

able to mention the two possible reasons that lead to the problem. More importantly, the problems and solutions are

connected well. The student provides a transition paragraph after the discussion of problems, sums them up, and then

notes that there are solutions to these problems. When discussing solutions to the problems, the student writes ‘‘the one

important [thing] to avoid culture shock is to [. . .]’’ to link it to the culture shock problem and ‘‘Making friends is very

difficult in U.S. college, [. . .]’’ to connect it to the second problem. The summary of problems after detailed

discussion, the transition between the problems and solutions sections, and the re-mentioning of each problem before

discussing solutions make the essay tightly organized and logically developed. The essay illustrates the student’s

understanding of the relationship between the two source texts and his/her ability to connect ideas from different

source texts in a synthesis essay. In addition, the student uses citations well. For example, the student paraphrases

information about the culture shock problem; the student not only writes down the source of the information ‘‘as Dr.

Sara Maggitti [. . .] said’’ but also mentions her credentials ‘‘a counselor at Cabrini College’’ to make the information

more credible. The student also uses a variety of introduction phrases before paraphrases such as ‘‘as Dr. Sara Maggitti

[. . .] said’’ and ‘‘she even points out that [. . .]’’ and successfully integrates the cited information into his/her own essay.

C. Zhang / Journal of Second Language Writing 22 (2013) 51–67 61

Overall, this essay illustrates the student’s ability to select important information from source texts, cite the

information appropriately, make connections among the selected information, and organize the essay logically.

Conclusion, implications and limitations

This study explores the possible effect of instruction on intermediate level ESL students’ problem-solution type of

synthesis writing with the ultimate aim of providing pedagogical practices/implications for ESL writing teachers.

Comparison of the experimental group students’ essays written at post-test with those written at pre-test shows that the

students significantly improved in their overall quality of synthesis essays. Compared to the control group students

who did not receive synthesis writing instruction, the experimental group students also wrote significantly better

essays at the time of the post-test. Detailed analysis of sample student essays from the pre-test and post-test illustrates

that the essay written by the experimental student at post-test is better than the pre-test experimental-group essay and

the post-test control-group essay in the areas of selecting important information, connecting different pieces of

information, and citing information from source texts. On the other hand, improvement in the control group students’

essays between pre- and post-test regarding the amount of information used from source texts and appropriate citation

does not also mean clear improvement in terms of selection and integration of source text information. Both the

holistic essay rating and detailed analysis of sample essays revealed the effects of instruction in these ESL students’

ability to write synthesis essays from two source texts.

Even though the present study only investigated the effect of instruction on ESL students’ ability to synthesize texts

with one specific task type, it provides a starting point for integrating synthesis writing instruction into an ESL writing

course while still working effectively with the course textbook. In the present study, the theme of each set of source

texts, the timing to introduce and practice synthesis writing, and the essay prompts were carefully controlled so that

synthesis writing instruction was an integral part of the course curriculum. Despite the relatively short amount of

classroom time spent on synthesis writing instruction (about 14 hours), students in the experimental group made

significant improvements. Results from this study suggest that integrating synthesis instruction into an ESL classroom

is possible without interrupting the existing ESL writing curriculum and that doing so can have a positive effect on

students’ synthesis writing.

Discourse synthesis is a difficult task to complete even for students at the university level because it involves many

different skills and knowledge resources; however, it is still teachable in a writing classroom. University composition

classes may include discourse synthesis as one type of essay in their curriculum; however, how to write this type of

essay is often not explicitly taught to L2 students. From a pedagogical point of view, discourse synthesis instruction

could be integrated into a writing curriculum even for students with relatively low L2 proficiency. To successfully do

this, however, the teacher needs to use level-appropriate materials, facilitate students’ text comprehension, help

students engage in repeated practice, and support students through challenging tasks such as discourse synthesis

writing.

One way to support students through the completion of challenging tasks is teacher scaffolding in the classroom.

Teacher scaffolding is important especially for the first time students encounter a new task (in this case, synthesis

writing and two types of synthesis essays), as the teacher illustrates how to use the reading guides and the connection

exercises and monitors students’ reading comprehension and task completion. In the present study, various methods—

reading guides, connection exercises, and peer and teacher feedback on their first drafts—were used to scaffold

students’ synthesis writing practice. The reading guides, through pre-reading, during-reading, and post-reading

questions, helped learners build good reading habits, pay attention to text structure, and distinguish main ideas and

supporting details. The connection exercises offered another chance to examine the content of the two source texts and

integrate pieces of information from the texts. Teacher and peer feedback facilitated the students’ writing process

because it helped them revise misunderstandings of the writing task and further develop their essays. The experimental

group of students thought highly of the usefulness of these activities for their discourse synthesis essays, especially the

connection exercises and teacher feedback.

This study also suggests that sequencing a large instructional project into smaller manageable steps can facilitate

students’ learning processes, especially in the early stages. In the present study, experimental group students were

guided through the discourse synthesis writing process: reading source texts, identifying main ideas, rereading the

source texts to find connections between them, selecting information, organizing information, and finally writing the

essay. Once a difficult task is broken down into a smaller set of practices, it will be more accessible for ESL students.

C. Zhang / Journal of Second Language Writing 22 (2013) 51–6762

This study shows that, with careful instruction, intermediate-level ESL students are able to complete discourse

synthesis tasks that integrate information from two texts. It would be interesting to see, in the future, whether similar

instructional support can help ESL students learn to handle more challenging discourse syntheses which involve more

than two source texts.

There are several limitations in the study. First of all, due to the small size of participants (n = 29) and the limited

variety of students’ L1 background, results from the study should only be generalized with other ESL students and

teaching contexts with caution. The number of participants in each group is relatively small; however, there were no

outliers who might have skewed the data in the present study, and having 14–15 students in one ESL class was ideal for

learning. On the other hand, students in the two classes were mainly from two L1 backgrounds: Chinese and Arabic.

These two groups may possess some characteristics distinct from other L1 groups (e.g., many Chinese students receive

more practice in reading and writing while Arabic students are often better in listening and speaking), and thus the

generalizability of the study is limited. To test whether discourse synthesis writing instruction is effective for a wider

range of ESL/EFL students, more studies are needed in which other L1 groups and teaching contexts are involved.

Apart from the limited number of participants and L1 groups, the fact that I was the instructor for both experimental

and control classes could be perceived as another source of limitation. As mentioned in the methods section, I

implemented several procedures to prevent potential researcher’s bias toward the experimental group. Despite these

precautions, there still may be bias, and future research may investigate other teachers’ classes.

Lastly, for the present study, ‘‘explicit instruction’’ (analysis of models, guidelines for writing syntheses, and teacher

guided selection and connection activities) and ‘‘practice’’ in writing syntheses were all subsumed under the construct of

instruction. While this may reflect most instructional practice, it might also be useful in future research to disentangle the

two a bit more to explore which aspects of instruction could have had the most (or different kinds of) impact.

Acknowledgments

I sincerely thank Dr. William Crawford and Jackie Evans for their support of my data collection, my students for

their active participation in my research, and Dr. William Grabe for his support of the research project and insightful

comments on earlier drafts of this article. I am also grateful to the editor and reviewers for their help in revising this

article.

Appendix A. Text 1: International students experience culture shock in colleges abroad: July 21, 2009, by

Tuna Asino

(1) Jolyon Girard, a professor and former chairman of the History and Political Science department at Cabrini College,

said one day to his modern Middle Eastern history class, ‘‘You think all there is to American culture is Britney

Spears and McDonalds, don’t you?’’ There is definitely more to American culture, and international students

coming here to the United States have to deal with a lot. Two main issues that students coming to the United States

have to deal with are cultural shock and the difficulty of making friends.

(2) C

ulture shock describes the loss of emotional balance when a person moves to an unfamiliar environment. Dr. SaraMaggitti, a counselor at Cabrini College, does not think that the term is being over-emphasized or exaggerated. She

said, ‘‘In my personal and professional experience, culture shock can have a significant impact on the individual

and can be debilitating.’’ She even thinks that an individual can subsequently develop emotional illness from

extreme culture shock.

(3) J

ennifer Marks-Gold, the international student adviser who has been working with international students for thepast 13 years, agrees with Maggitti. When asked if it is a sign of weakness for one to feel cultural shock symptoms,

she replied, ‘‘No, not at all. Many students experience culture shock but in various forms and at different times. It is

not a weakness. This is a documented psychological occurrence.’’

(4) A

second major issue international students have to deal with is making friends. Friendship is something that isdifficult to develop at college, and American schools are no exceptions. American students may be very friendly—

they may talk, smile and joke—but this does not necessarily mean a commitment to friendship.

(5) O

ne reason why American students do not make quick friendships is because they are interested in establishingpersonal freedom and finding their own ways, so they tend to be cautious about making commitments. People are

not always very open to others, or to new experiences outside of their comfort zones.

C. Zhang / Journal of Second Language Writing 22 (2013) 51–67 63

(6) D

r. Christine Lysionek, vice president of student development, has a different point of view: ‘‘American students havea difficult time making friends with international students; however, this is not because American students want their

independence. I think college students tend to become friends with others who live in close proximity to them in the

residence halls, who belong to the same student organizations as they do, or who share similar interests.’’

(7) A

nother main issue for international students is the class settings. Some instructors do not seem to notice there areinternational students in their classes. The topics for discussions are not ‘‘international friendly.’’ Yet all the

students are expected to participate because they will get grades for class participation.

Text 2: How to survive as an international student: August 07, 2009, by Patrick Coomer

(1) Pursuing education in a foreign country poses a mix of positive and negative feelings. On a good note, studying

abroad will create a lot of new opportunities. You will get to meet new friends and experience diverse cultures.

However, timid students may be unenthusiastic about this idea. They may see studying abroad as awkward and

isolating. Whatever the case, international students will naturally feel the pressure and anxiety of living lives away

from their families and usual lifestyles. Nevertheless, here are some useful tips that will equip you, as an

international student, in surviving international schooling amidst the excitement of a new environment.

(2) T

here are many things you have to get used to when living in another country. When you come to a new culture thatis drastically different from your home culture, you are likely to experience culture shock. What strategies can you

use to minimize, and cope with, culture shock? Research has shown that our expectations affect how we react to a

new country. Therefore, thorough pre-departure preparations are necessary. Before coming to the U.S., it is

beneficial to read the pre-departure materials that your school sends to you and ask friends who have studied in the

U.S. for advice. Also, before leaving home, it is helpful for you to develop some social survival skills such as how

to address people in different social groups and to know acceptable social behaviors in a range of everyday settings.

(3) A

fter arriving at your new university or college, several things may assist you in reducing the strain of cultureshock. Soon after arriving, explore your immediate environment. After having gotten advice on personal safety,

walk around and get to know your neighborhood. Be courageous and introduce yourself to your neighbors. If you

live in a university dorm, they are likely to be other students who feel just the way you do. Also, feel free to ask

questions about social customs from people with whom you feel comfortable. You should always be able to find

someone who will assist you in finding out about life in the U.S. In addition, keep in touch with your own culture;

this will help lessen your homesickness.

(4) M

aking friends is difficult but not impossible. For a new international student to function well in this newenvironment, you have to be in shape holistically. This means that you are well-nourished physically,

mentally, emotionally, and socially. Even if you are drowning from school work, you still have to attend to

your other necessities. To make friends, you need to take a break from studying and participate in social

activities. It is very important for you to join clubs and organizations and participate fully in all of the out-of-

class activities at your university because those things provide structured opportunities to meet other people

and make new friends.

Essay prompt

Instructions: Read the following essay prompt and write your essay on the lined papers provided to you. If you need

more paper, please let me know.

Essay prompt: More and more students from different countries choose to study in United States colleges and

universities. However, students who choose to study abroad in the U.S. have some problems. Based on the two texts

you read, write an essay. In your essay, discuss the major problems that international students face when studying in the

U.S. and possible solutions to their problems.

In your essay, you should:

� U

se information from these two supplementary texts:� ‘‘International students encounter culture shock in colleges abroad’’

� ‘‘How to survive as an international student’’

C. Zhang / Journal of Second Language Writing 22 (2013) 51–6764

� P

lan and write your essay following the general essay organization: introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion.� U

se correct quotations and paraphrases.� D

o not directly copy long phrases or sentences from the texts.Your essay will be evaluated on its organization, format, use of information from both texts, and language use.

Appendix B

Adapted Plakans’ holistic scoring rubric.

Score

Task description5

A response at this level:� Successfully addresses the assignment through the use of a clear problem-solution organizational pattern

� Successfully presents all important information from source texts in relation to prompt

� Is well organized with well-developed content

� Occasional language errors that are present do not result in inaccurate or imprecise presentation of content or connections

4

A response at this level:� Adequately addresses the assignment through the use of a relatively clear problem-solution organizational pattern

� Is generally good in coherently and accurately presenting relevant information from source texts, although the response may have

information not (correctly) referenced

� Has clear organization and logical development

� Contains more frequent or noticeable minor language errors that do not result in anything more than an occasional lapse of clarity

or in the connection of ideas

3

A response at this level:� Largely addresses the assignment; problem-solution organizational pattern is present but may need reader effort to identify

� Presents most important information from source texts, but may be lack of one or two problems/solutions, or problems and

solutions may be mismatched

� Occasionally lacks cohesion but has a basic organizational structure and development

� Includes many usage and grammar errors that may result in noticeably vague expressions or obscured meanings

2

A response at this level:� Partially addresses the assignment; only parts of problems and/or solutions are present

� Contains some relevant information from the readings, but is marked by significant omission or inaccuracy of important ideas from

the readings or largely copied texts

� Lacks logical organizational coherence and development

� Contains language errors or expressions that largely obscure connections or meaning at key junctures, or that would likely obscure

understanding of key ideas

1

A response at this level:� Addresses the assignment to a very limited degree; problem-solution pattern is not evident

� Provides little or no meaningful or relevant coherent content from the readings and does not follow an organization pattern or

develop content

� Most language in the writing is copied or includes language that is so low it is difficult to derive meaning

0

A response at this level:� Either merely copies sentences from the reading, rejects the topic, not connected to the topic, is written in a foreign language,

or is blank

Appendix C. Sample student essay written at pre-test: study abroad in the U.S.

Students who come from different countries choose to study in America. The number is increased year by year.

When we study in an unfamiliar environment, we may become more independent than before. And having a general

idea about the different culture. Obtaining knowledge via a new educational system. However, there are many

problems which we will come across.

C. Zhang / Journal of Second Language Writing 22 (2013) 51–67 65

Culture shock is a big problem. Dr. Sara Maggitti, a counselor at Cabrini College said, ‘‘In my personal and

professional experience, culture shock can have a significan impact on the individual and can be debilitating.’’ She

even think thinks that an individual can subsequently develop emotional illness from extreme culture shock. Actually,

because of culture shock, we may have the difficulty of making friends. Friendship seem to difficult to develop. Some

Americans look like very friendly—they say Hi, Hello to you, smaile and play games—but it doesn’t mean making

friends or friendship. Without many friends arround us, we may feel longly sometimes. We have few chance to share

the happy things or sadness with other people. It is hard to join in a discussion with American students. We almost

don’t have the similar interests. If we refuse to experience diverse cultures, we will go instant. We need try to adapt to a

new environment. In a foreign country, making friends is difficult but not impossible. When you take a break from

studying, it’s very necessary for us to participate in some organizations or some kinds of clubs or out-of-class activities

in our university. Those thing provide opportunities for us to make new friends.

In our country, we have ourselves life style about eating habits and life pace. When we go abroad, we should

change some habits as soon as possible. We have to accept the fast food. When start, it might be difficult.

However, times go by. It can be very helpful for us to develop many survival skills. After arriving in our new

university. The first thing is gotten advice on personal safety, then, walk around the campus, we will know

something such as where are the buildings located in—supermarket, dorms—It may be easier for you life. Don’t

forget to keep in touch with your parents and you hometown friend, because it will help lessen your

homesickness.

In conclusion, study abroad is not an easy thing. I should solve many problems by myself. We will come across lots

of chanllenges. On the coutrary, why not to say there are lots of oppotunities waiting for me?

Appendix D. Sample control group student essay at post-test

Most of the international student choose to study the university in the U.S. The U.S have a lot of strong university.

While the U.S is a big country, but the international student face a lot of problem. The two important problem its the

‘‘culture shock’’ and ‘‘making friend’’, we could solve this problem but after a while.

The culture the first problem the international student face when they arrived to the U.S. The culture shock mean

lost of emotion balance when the student move to a new place that he know nothing about it. When the student first

come to the U.S and he face this problem, so he do not feel comfortale, that make to think about going back home and

leave everything behind him, some other people start feel homesick which they make it bigger more than it seem, but it

depend on the person and the way he think, some people give up so fast, and some keep trying. According to Mark-gold

(2009) ‘‘many student experience culture shock but in various forms and at different times. It’s not a weakness. This is

a documented psychological occurrence.’’ So the student have to be that hard on them self because the donot have

many option, and they will be better after a while.

The second problem that international student feel bad because of it, it’s hard to make friend or any relationship

with American people, not because they are selfesh or they donot like the international student, but there’s some other

reasons. They can be so nice to you but does not mean there’s a relationship between them. There’s many reason that it

hard to make a friendship with American student. American student are thinking and trying to creat thier personal

freedom and get their own ways in life, so they are busy to make friendship, and some other don’t like to make

relationship with who are outside their nigborhood, according to Lysionek (2009) ‘‘American student have a diffecult

time making friend’s with international’’ that not because American don’t like the international student, because

American student have a friend just from the niegherhood, or they live in the same hall. So it’s hard to make friendship

with American. I think student should look for student from their courtry so they understand each other, so they dont

feel lonely and think about going back home.

In conclusion, every new international student who dont have relative in U.S. he will suffer in the beginning, but

after few months he will be more than good, and most of student wont go back home after they finish, but we must

know that our goal is to study and succeed.

Appendix E. Sample experimental group student essay at post-test: international students

Many people now notice that the earth become more and more smaller. The connection between countries is very

convenent now, and it is very easy to go abroad. So many students from different countries choose to study abroad, and

C. Zhang / Journal of Second Language Writing 22 (2013) 51–6766

the United States has a well-known good quality of education. More and more students come to study in United States

colleges and universities.

However, studying abroad in United States is not all perfect. There are many problems that the international

students have to face. I am a international students in U.S. as well. I also have some problems. To pursuit a good study

environment in U.S. there are also have some advices and solutions we should know. I find some problems and

solutions from two articles.

Jolyon Girard, a professor and former chairman of the History and Political Science department at Cabrini College

said the words mentioned one issues that international students in U.S. have to deal with. He said that all American

culture the international students know is about Britney Spears and McDonalds staff (Asino, 1). The one main issue is

culture shock.

As Dr. Sara Maggitti, a counselor at Cabrini College said, the culture shock which the international

students face have a significant impact on the individual and can be debilitating. She even points out that the

international students who have extreme culture shock can be very lonely and become emotional illness

(Asino, 2). The culture shock makes the students seprated from the group they live, and many students experience

culture shock.

A second main issue of international students is about making friends. Developing a friendship is very difficult at

college, it is the same in American college. Although American students may be very kind and friendly, to develop the

friendship, as well is very hard (Asino, 4). It becomes much diffcult for international students to make friends with

native American students. The American students don’t make quick friendships because they are indenpdent and they

like to live in the way they joy the live. So they make friends with the one who lives in same culture or who has similar

interents (Asino, 6). For the international students who come from the different countries, have extremly different

culture, it is hard to take part in the American friendship environment. It lets them isolate from American students, the

loneiness will become stronger.

Another problem for international students is the class settings. In U.S., some instructors do not pay more attention

to international students. They make some topics that is not normal or interesting for international students. That

makes the students so hard to enjoy the discussions, just for the grades (Asino, 7).

The culture shock, making friends and class settings problems, let international students feel studing abroad is

isolating, and will have much pressure. According an article by Patrick Coomer, there are some advices which the

international students can follow.

The one important thing to aviod culture shock is to do the pre-dearture preparations. Before coming to the U.S., the

students can read some materials about their school and culture. They can ask their friends who have studied in the

U.S. to give them some advices. They also need to papare some information to help them solute the social skills issues

(Coomer, 2).

When international students in the U.S. university or college, for lessening the culture they can explore their

immediate environment. Depend on keeping themselves safe, they can walk around to know the basic environment.

They also can get to know their neighborhood to introduce themselves. To ask some questions about social customs

from the person who is friendly is another good way to lessen the culture shock. Besides, keep in touch with family and

friends in their own countries can lessen the feeling of homesick (Coomer, 3).

Making friends is very difficult in U.S. college, but it doesn’t mean that international students can not make

friends wit American students. To join clubs and organizations and participate fully in all of the out-of-class

activities, it will make more chances for the students to make friends, it is easy to find someone who has the same

interests (Coomer, 4). Also, the international students have their own charming thing. They come from different

countries, so it makes them very eomxtic to American students. The curiorsty from each other also can let them to

make more new friends.

Studying abroad in U.S. is a very good opportunity. The high quality of education and the freedom of study attract

more and more students coming to study. The culture shock and making friends problems also worried by international

students. But if they have well-papared, and more postive to face those problems. They can have a better exprience in

U.S., and it can influnce them have a better life in the future. I hope every international students can find their ways to

fit the study enviroment and life in U.S.

Work cited

Tuna Asino, International students experience culture shock in colleges abroad. July 21, 2009.

Patrick Coomer, How to survive as an international student. August 07, 2009.

C. Zhang / Journal of Second Language Writing 22 (2013) 51–67 67

References

Boscolo, P., Arfe, B., & Quarisa, M. (2007). Improving the quality of students’ academic writing: An intervention study. Studies in Higher

Education, 32, 419–438.

Bridgeman, B., & Carson, S. (1984). Survey of academic writing tasks. Written Communication, 1, 247–280.

Dingle, K., & Lebedev, J. R. (2007). Vocabulary power 2: Practicing essential words. Pearson Education.

English, A. K., & English, L. M. (2009). NorthStar reading and writing 4 (3rd ed.). White Plains, NY: Pearson Education.