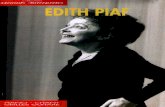

Edith Piaf

description

Transcript of Edith Piaf

http://www.little-sparrow.co.uk/

Edith Piaf (December 19, 1915 - October 11, 1963) was one of France's most beloved singers, with much success shortly before and during World War II. Her music reflected her tragic life, with her specialty being the poignant ballad presented with a heartbreaking voice. The most famous songs performed by Piaf were La Vie en Rose (1946), Milord (1959), and Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien (1960).

She was born Édith Giovanna Gassion in Paris, France; her mother worked as a cafe singer and her father was a well-known travelling acrobat. Abandoned by her mother, she was raised by her paternal grandmother, who ran a brothel in Normandy. From age 3 to 7, she was blind. As part of Édith Piaf's legend, she allegedly recovered her sight after her grandmother's prostitutes went to a pilgrimage to Saint Thérèse de Lisieux. Later she lived for a while with her alcoholic father, whom she left by age 15 to become a street singer in Paris.

In 1935, Édith was discovered by the nightclub owner Louis Leplée whose club was frequented by the upper and lower classes alike. He convinced Édith to sing despite her extreme nervousness, and gave her the nickname that would stay with her for the rest of her life: La Mome Piaf (The Little Sparrow). From this she took her stage name. Her first record was produced in the same year. Shortly thereafter, Leplée was murdered and Piaf was accused of being an accessory; she was acquitted.

In 1940, Jean Cocteau wrote the successful play Le Bel Indifferent for her to star in. She began to make friends with famous people, such as the actor Maurice Chevalier and the poet Jacques Borgeat.

She wrote her signature song, La Vie en Rose, in the middle of the German occupation in World War II. During this time, she was in great demand and very successful. Singing for high-ranking Germans at the One Two Two Club earned Édith Piaf the right to pose for photos with French prisoners of war, ostensibly as a morale-boosting exercise. Once in possession of their celebrity photos, prisoners were able to cut out their own images and use them in forged papers as part of escape plans. Today, Édith Piaf's association with the French Resistance is well known and many owe their lives to her. After the war, Édith toured Europe, the United States, and South America, becoming an internationally known figure.

She helped to launch the career of Charles Aznavour, taking him on tour with her in France and to the United States.

Piaf had one child, a daughter, Marcelle, who died at the age of two in 1935; the child's father was Louis Dupont. The great love of Piaf's life, the boxer Marcel Cerdan, died in 1949. Piaf was married twice. Her first husband was Jacques Pills, a singer; they married in 1952 and divorced in 1956. Her second husband, Theophanis Lamboukas (a.k.a. Théo Sarapo), was a 20-years-younger hairdresser turned singer and actor; they married in 1962.

The Paris Olympia is the place where Édith Piaf achieved fame and where, just a few months before her death, she gave one of her most memorable concerts while barely able to stand. In early 1963, Édith recorded her last song, L'homme de Berlin.

1

Piaf died of cancer in Cannes on October 11, 1963, the same day as her friend Jean Cocteau. She was buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris. Although forbidden a Mass by the Roman Catholic archbishop of Paris (because of her lifestyle), her funeral procession drew hundreds of thousands of mourners onto the streets of Paris and the ceremony at the cemetery was jammed with more than forty thousand fans. Charles Aznavour recalled that Piaf's funeral procession was the only time, since the end of World War II, that Parisian traffic came to a complete stop.

There is a museum dedicated to Piaf, the Musée Édith Piaf at 5, rue Crespin du Gast, 75011, Paris.

Today she is still remembered and revered as one of the greatest singers France has ever produced. Her life was one of sharp contrasts: the range of her fame as opposed to her tragic personal life, and her fragile small figure on stage with the resounding power of her voice.

Edith Piaf is almost universally regarded as France's greatest popular singer. Still revered as an icon decades after her death, "the Sparrow" served as a touchstone for virtually every chansonnier, male or female, who followed her. Her greatest strength wasn't so much her technique, or the purity of her voice, but the raw, passionate power of her singing. (Given her extraordinarily petite size, audiences marveled all the more at the force of her vocals.) Her style epitomized that of the classic French chanson: highly emotional, even melodramatic, with a wide, rapid vibrato that wrung every last drop of sentiment from a lyric. She preferred melancholy, mournful material, singing about heartache, tragedy, poverty, and the harsh reality of life on the streets; much of it was based to some degree on her real-life experiences, written specifically for her by an ever-shifting cast of songwriters. Her life was the stuff of legend, starting with her dramatic rise from uneducated Paris street urchin to star of international renown. Along the way, she lost her only child at age three, fell victim to substance abuse problems, survived three car accidents, and took a seemingly endless parade of lovers, one of whom perished in a plane crash on his way to visit her. Early in her career, she chose men who could help and instruct her; later in life, with her own status secure, she helped many of her lovers in their ambitions to become songwriters or singers, then dropped them once her mentorship had served its purpose. By the time cancer claimed her life at age 47, Piaf had recorded a lengthy string of genre-defining classics -- "Mon Légionnaire," "La Vie en Rose," "L'Hymne à l'Amour," "Milord," and "Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien" among them -- that many of her fans felt captured the essence of the French soul.

Piaf was born Edith Giovanna Gassion on December 19, 1915, in Ménilmontant, one of the poorer districts of Paris. According to legend, she was born under a street light on the corner of the Rue de Belleville, with her mother attended by two policemen; some have disputed this story, finding it much likelier that she was born in the local hospital. Whatever the case, Piaf's origins were undeniably humble. Her father, Louis Gassion, was a traveling acrobat and street performer, while her Moroccan-Italian mother, Anita Maillard, was an alcoholic, an occasional prostitute, and an aspiring singer who performed in cafés and on street corners under the name Line Marsa. With her father serving in World War I, Edith was virtually ignored by both her mother and grandmother; after the war, her father sent her to live with his own mother, who helped run a small brothel in the Normandy town of Bernay. The prostitutes helped look after Edith when they could; one story goes that when five-year-old Edith lost her sight during an acute case of conjunctivitis, the prostitutes shut down the brothel to spend a day praying for her in church, and her blindness disappeared several days later.

2

Edith's father returned for her in 1922, and instead of sending her to school, he brought her to Paris to join his street act. It was here that she got her first experience singing in public, but her main duty at first was to pass the hat among the crowd of onlookers, manipulating extra money from whomever she could. She and her father traveled all over France together until 1930, when the now-teenaged Edith had developed her singing into a main attraction. She teamed up with her half-sister and lifelong partner in mischief, Simone Berteaut, and sang for tips in the streets, squares, cafés, and military camps, while living in a succession of cheap, squalid hotels. She moved in circles of petty criminals and led a promiscuous nightlife, with a predilection for pimps and other street toughs who could protect her while she earned her meager living as a street performer. In 1932, she fell in love with a delivery boy named Louis Dupont, and bore him a daughter. However, in a pattern she would repeat throughout her life, she tired of the relationship, cheated, and ended it before he could do the same. Much like her own mother, Edith found it difficult to care for a child while working in the streets, and often left her daughter alone. Dupont eventually took the child himself, but she died of meningitis several months later. Edith's next boyfriend was a pimp who took a commission from her singing tips, in exchange for not forcing her into prostitution; when she broke off the affair, he nearly succeeded in shooting her.

Living the high-risk life that she did, Edith Gassion almost certainly would have come to a bad end had she not been discovered by cabaret owner Louis Leplée while singing on a street corner in the Pigalle area in 1935. Struck by the force of her voice, Leplée took the young singer under his wing and groomed her to become his resident star act. He renamed her "La Môme Piaf" (which in Parisian slang translates roughly as "the little sparrow" or "the kid sparrow"), fleshed out her song repertoire, taught her the basics of stage presence, and outfitted her in a plain black dress that would become her visual trademark. Leplée's extensive publicity campaign brought many noted celebrities to Piaf's opening night, including Maurice Chevalier; she was a smashing success, and in January 1936, she cut her first records for Polydor, "Les Momes de la Cloche" and "L'Étranger"; the latter was penned by Marguerite Monnot, who would continue to write for Piaf for the remainder of both their careers.

Tragedy struck in April 1936, when Leplée was shot to death in his apartment. Police suspicion initially fell on Piaf and the highly disreputable company she often kept, and the ensuing media furor threatened to derail her career even after she was cleared of any involvement. Scandal preceded her when she toured the provinces outside Paris that summer, and she realized that she needed help in rehabilitating her career and image. When she returned to Paris, she sought out Raymond Asso, a songwriter, businessman, and Foreign Legion veteran; she had rejected his song "Mon Légionnaire," but it had subsequently been recorded by Marie Dubas, one of Piaf's major influences. Intensely attracted to Piaf, Asso began an affair with her and took charge of managing her career. He partially restored her real name, billing her as Edith Piaf; he barred all of Piaf's undesirable acquaintances from seeing her; he set about making up for the basic education that neither Edith nor Simone had received. Most importantly, he talked with Piaf about her childhood on the streets, and teamed up with "L'Étranger" composer Marguerite Monnot to craft an original repertoire that would be unique to Piaf's experiences. In January 1937, Piaf recorded "Mon Légionnaire" for a major hit, and went on to cut the Asso/Monnot collaborations "Le Fanion de la Légion," "C'est Lui Que Mon Coeur a Choisi" (a smash hit in late 1938), "Le Petit Monsieur Triste," "Elle Frequentait la Rue Pigalle," "Je N'en Connais Pas la Fin," and others. Later that year, Piaf made concert appearances at the ABC Theater (where she opened for Charles Trenet) and the Bobino (as the headliner); the shows were wildly successful and made her the new star of the Paris music scene.

3

In the fall of 1939, Asso was called to serve in World War II. Early the next year, Piaf recorded one of her signature songs, "L'Accordéoniste," just before its composer, Michel Emer, left for the war; she would later help the Jewish Emer escape France during the Nazi occupation. In Asso's absence, she took up with actor/singer Paul Meurisse, from whom she picked up the refinements and culture of upper-class French society. They performed together often, and also co-starred in Jean Cocteau's one-act play Le Bel Indifférent; however, their relationship soon deteriorated, and Piaf and Simone moved into an apartment over a high-class brothel. By this time, the Nazis had taken over Paris, and the brothel's clientele often included Gestapo officers. Piaf was long suspected of collaborating with -- or, at least, being overly friendly to -- the Germans, making numerous acquaintances through her residence and performing at private events. She resisted in her own way, however; she dated Jewish pianist Norbert Glanzberg, and also co-wrote the subtle protest song "Où Sont-Ils Mes Petits Copains?" with Marguerite Monnot in 1943, defying a Nazi request to remove the song from her concert repertoire. According to one story, Piaf posed for a photo at a prison camp; the images of the French prisoners in the photo were later blown up and used in false documents that helped many of them escape.

Before the war's end, Piaf took up with journalist Henri Contet, and convinced him to team up with Marguerite Monnot as a lyricist. This proved to be the most productive partnership since the Asso years, and Piaf was rewarded with a burst of new material: "Coup de Grisou," "Monsieur Saint-Pierre," "Le Brun et le Blond," "Histoire du Coeur," "Y'a Pas D'Printemps," and many others. Her affair with Contet was relatively brief, but he continued to write for her after they split; meanwhile, Piaf moved on to an attractive young singer named Yves Montand in 1944. Under Piaf's rigorous tutelage, Montand grew into one of French pop's biggest stars within a year, and she broke off the affair when his popularity began to rival her own. Her next protégés were a nine-member singing group called Les Compagnons de la Chanson, who toured and recorded with her over the next few years (one member also became her lover). Now recording for the Pathe label, she scored a major hit in 1946 with "Les Trois Cloches," which would later become an English-language smash for the Browns when translated into "The Three Bells." Later that year, she recorded the self-composed number "La Vie en Rose," another huge hit that international audiences would come to regard as her signature song.

Piaf embarked on her first American tour in late 1947, and at first met with little success; audiences expecting a bright, gaudy Parisian spectacle were disappointed with her simple presentation and downcast songs. Just as she was about to leave the country, a prominent New York critic wrote a glowing review of her show, urging audiences not to dismiss her out of hand; she was booked at the Café Versailles in New York, and thanks to the publicity, she was a hit, staying for over five months. In that time, she met up with French boxer Marcel Cerdan, an acquaintance of about a year. In spite of Cerdan's marriage, the two began a passionate affair, not long before Cerdan won the world middleweight championship and became a French national hero. Unfortunately, tragedy struck in October 1949, when Cerdan was planning to visit Piaf in New York; wanting him to arrive sooner, she convinced him to take a plane instead of a boat. The plane crashed in the Azores, killing him. Devastated by guilt and grief, Piaf sank into drug and alcohol abuse, and began to experiment with morphine. In early 1950, she recorded "L'Hymne à l'Amour," a tribute to the one lover Piaf would never quite get over; co-written with Marguerite Monnot, it became one of her best-known and most heartfelt songs.

In 1951, Piaf met the young singer/songwriter Charles Aznavour, a future giant of French song who became her next protégé; unlike her others, this relationship always remained

4

strictly platonic, despite the enduring closeness and loyalty of their friendship. Aznavour served as a jack-of-all-trades for Piaf -- secretary, chauffeur, etc. -- and she helped him get bookings, brought him on tour, and recorded several of his early songs, including the hit "Plus Bleu Que Tes Yeux" and "Jézébel." Their friendship nearly came to an early end when both were involved in a serious car accident (as passengers); Piaf suffered a broken arm and two broken ribs. With her doctor prescribing morphine for pain relief, she soon developed a serious chemical dependency to go with her increasing alcohol problems. In 1952, she romanced and married singer Jacques Pills, who co-wrote her hit "Je T'ai Dans la Peau" with his pianist, Gilbert Bécaud; Bécaud would soon go on to become yet another of the pop stars launched into orbit with Piaf's assistance. Meanwhile, Pills soon discovered the gravity of Piaf's substance abuse problems, and forced her into a detox clinic on three separate occasions. Nonetheless, Piaf continued to record and perform with great success, including appearances at Carnegie Hall and Paris' legendary Olympia theater. She and Pills divorced in 1955; not long afterward, she suffered an attack of delirium tremens and had to be hospitalized.

As an interpretive singer, Piaf was at the height of her powers during the mid-'50s, even in spite of all her health woes. Her international tours were consistently successful, and the devotion of her massive French following verged on worship. She scored several more hits over 1956-1958, among them "La Foule," "Les Amants D'un Jour," "L'homme à la Moto," and the smash "Mon Manège à Moi." During that period, she also completed another stay in detox; this time would prove to be successful, but years of drug and alcohol abuse had already destabilized her health. In late 1958, she met another up-and-coming songwriter, Georges Moustaki, and made him her latest lover and improvement project. Teaming once again with Marguerite Monnot, Moustaki co-wrote "Milord," an enormous hit that topped the charts all over Europe in early 1959 and became Piaf's first successful single in the U.K. Later that year, she and Moustaki were involved in another car accident, in which her face was badly cut; in early 1960, while performing at the Waldorf Astoria in New York, she collapsed and began to vomit blood on stage, and was rushed to the hospital for emergency stomach surgery. Stubbornly, she continued her tour, and collapsed on-stage again in Stockholm; this time she was sent back to Paris for more surgery.

Piaf was soon back in the recording studio, eager to record a composition by the legendary French songwriter Charles Dumont. "Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien" became one of her all-time classics and a huge international hit in 1960, serving as something of an equivalent to Frank Sinatra's "My Way." Piaf went on to score further hits with more Dumont songs, including "Mon Dieu," "Les Flons-Flons du Bal," and "Les Mots D'Amour." She staged a lengthy run at the Olympia in 1961, and later that year met an aspiring Greek singer named Théo Sarapo (born Theophanis Lamboukis), who became her latest project and, eventually, second husband. Sarapo was half her age, and given Piaf's poor health, the French media derided him as a gold digger. Nonetheless, they cut the duet "À Quoi Ça Sert l'Amour" in 1962, and performed together during Piaf's final engagement at the Olympia that year. Despite her physical weakness -- on some nights, she could barely stand -- Piaf had lost very little of the power in her voice.

Piaf and Sarapo sang together at the Bobino in early 1963, and Piaf also made her final recording, "L'Homme de Berlin." Not long afterward, Piaf slipped into a coma, brought on by cancer. Sarapo and Simone Berteaut took Piaf to her villa in Plascassier, on the French Riviera, to nurse her. She drifted in and out of consciousness for months before passing away on October 11, 1963 -- the same day as legendary writer/filmmaker Jean Cocteau. Her body

5

was taken back to Paris in secret, so that fans could believe she died in her hometown. The news of her death caused a nationwide outpouring of grief, and tens of thousands of fans jammed the streets of Paris, stopping traffic to watch her funeral procession. Her towering stature in French popular music has hardly diminished in the years since; her grave at Père-Lachaise remains one of the famed cemetery's most visited, and her songs continue to be covered by countless classic-style pop artists, both French and otherwise. ~ Steve Huey, All Music Guide

Singer, actress

"A thousand years from now," wrote Monique Lange in Piaf, her biography of French songstress Edith Piaf, "Piafs voice will still be heard, and each time we hear it we will wonder anew at its strength, its violence, its lyrical magic." Edith Piafs rise from street urchin to concert-hall chanteuse was more romantic than any novel. Her end in drug and alcohol dependency was sadder than any melodrama. Her voice expressed the agony of millions, and millions followed her love affairs and her divorces, knew her songs, and revelled in the triumphant comebacks she made time and again. She was adored everywhere, but she never stopped searching for love.

Edith Giovanna Gassion was born on December 19, 1915, into a less-than-glamorous life in a working-class neighborhood of Paris. Her father, Louis, was an itinerant acrobat who traveled from town to town, performing at streetside for tips. Edith's mother, Anetta—who was many years her husband's junior—worked at a carnival, sang on the street, and later sang in cafes.

Edith's childhood was spent either on the road with her parents or shuttling between relatives. When she was still quite young, her father was drafted to fight in World War I. The poverty-stricken Anetta found it too difficult to care for a child on her own and abandoned Edith, leaving the youngster with her mother. Edith's existence with her grandmother was not a happy one: she was rarely fed, washed even less often, and was given wine to put her to sleep whenever she cried.

Lived With Madame Grandmother

Edith's father was appalled at the condition in which he found his daughter when he returned home on leave from the army. He took her to stay with his mother, who ran a whorehouse in Normandy. Life for the young Piaf in a brothel was better than one might expect. The ladies doted on Edith, and she was better fed than she had been thus far in her life. Unfortunately this arrangement did not last. When a local priest suggested that a brothel was not the best place to raise a child, Edith's father took her on the road.

Edith toured through France and Belgium with her father, collecting money proffered by passersby while he performed his tricks. Sometimes he told her to play upon the sympathies of women and ask them to be her mother. Other times he sent her out to sing; even as a child she had the kind of voice that could draw a crowd.

When she was 15 Edith left her father and, with her friend Mamone, began making her own way on the streets of Paris. To support themselves Edith would sing and Mamone would collect money. Sometimes they made enough for a room; other times they spent their earnings in a saloon and slept in parks or alleyways.

6

It was during this period that Edith met Louis Dupont. He and Edith began living together, and in February of 1933 they had a daughter, Cecille. In an effort to assert his dominance, Dupont forced Edith to stop singing. They each took low-paying jobs—which Edith was rarely able to keep—and spent the rest of their time in a cramped apartment in a Paris slum. Edith could not tolerate the loss of freedom for long. She eventually returned to her former life on the streets, taking Cecille with her. Sadly, the child died of meningitis before reaching her second birthday.

"Piaf Took Flight

Not long after Cecille's death, yet another Louis came into Edith's life. In her autobiography, The Wheel of Fortune, Edith described her first meeting with Louis Leplee: "I was pale and unkempt. I had no stockings and my coat was out at the elbows and hung down to my ankles. I was singing a song by Jean Lenoir.... When I had finished my song .. . a man approached me.... He came straight to the point: 'Are you crazy? You are ruining your voice.'" Leplee, the owner of Gurney's—a very popular Paris night spot at the time—knew talent when he heard it, even if it was ill-dressed and dirty. He offered Edith a job and gave her the name "La Mome Piaf" ("Kid Sparrow"). Within a week, the four-foot, ten-inch Piaf was appearing on stage in her trademark black attire. Within a few months she made her first recording, "L'Etranger" ("The Stranger") on Polydor Records.

Piafs meteoric rise came to an abrupt halt six months later. On April 7, 1936, Louis Leplee was found murdered in his Paris apartment. Piaf was stricken by the news. The press went wild, splashing her picture all over the tabloids and calling her a suspect. Paris audiences grew so hostile that Piaf was forced to leave the city. She subsequently performed in the Paris suburbs, in Nice, and in Belgium.

When the scandal had died down and Piaf was able to return to Paris, in 1937, she began an important association with songwriter Raymond Asso. It was Asso, along with Marguerite Monnot, who wrote Piafs first hit, "Mon Legionnaire" ("My Legionaire"). This song, like so many others she sang, told the story of a woman abandoned.

Asso became much more than a songwriter to Piaf. For three years he guided her career, teaching her how to be a star, and was her lover. In Margaret Crosland's Piaf, Asso stressed, "I trained her, I taught her everything, gestures, inflection, how to dress." Piaf, for her part, though she owed much to Asso, took a new lover when the French Army called him in August of 1939.

The War Years

Oddly, the years during the war were some of the best of Piafs career. The cafes and theaters remained open during the German occupation of France, and she continued to sing. It was also during this time that her career expanded to include more roles on the stage and screen. In 1940 she appeared in Jean Cocteau's play Le Bel indifferent, and she had a role in Georges Lacombe's 1941 film Montmartre-sur-Seine, for which she also wrote several songs.

For the Record. . .

Born Edith Giovanna Gassion, December 19, 1915, in Paris, France; died October 10, 1963 in Placassier, France; daughter of Louis Alphonse (an acrobat and circus performer) and Anetta (a cafe singer; maiden name,

7

Maillard) Gassion; married Jacques Pills (a singer), September, 1952 (divorced, c. 1953); married Theo Sarapo (a singer), October 9, 1962; children: (with Louis Dupont) Cecille (died of meningitis c. 1934).

Began singing on the streets, c. 1925; debuted professionally at Gumey's, Paris, France, appearing for six months beginning in 1935; made first recording, "L'Etranger" ("The Stranger"), Polydor, 1936; made American debut in New York City, 1947; comeback appearance, Olympia Theater, Paris, 1960. Actress appearing in motion pictures, including La Garçon, 1936, Montmartre-sur-Seine, 1941, Etoile sans lumiere, 1946, Neuf Garcons, un coeur, 1947, Paris chante toujours, 1951, Boum sur Paris, 1952, Si Versailles m'tait conte, 1953, French Cancan, 1954, Les Amants de demain, 1958; and in plays, including Le Bel indifferent, 1941. Author of The Wheel of Fortune, Chilton Books, 1965.

But while Piaf advanced her career, she also knew her role as a French citizen and did her part to help the war effort. She was a savior to the French prisoners of war at Stallag III, whom she entertained on two different occasions. After the first performance, she asked the Germans if she could have pictures taken with the prisoners for their families in France. When she returned to the camp for her second performance, she brought forged identity papers, which allowed many prisoners to escape.

After the war Piaf set out to make herself an international star. Her 1946 release of "La Vie en Rose" became a major American hit. She arrived in New York City in 1947 to begin a series of American engagements. The petite Piaf, with her simple black dress and songs of struggle and abandonment, was not the sexy, sophisticated Frenchwoman many Americans expected, and she initially met with little success. It was not until a performance at the Versailles—one of the most elegant supper clubs in New York—and several glowing reviews that Edith Piaf became the toast of Manhattan and later Hollywood society.

Love and Decline

While in New York, Piaf began an affair with Marcel Cerdan, the French boxer and newly crowned middle-weight champion. Like all of her romances, the union was a torrid one. As a boxer, Cerdan traveled extensively, though Piaf wanted him to be with her. He was in the Azores when Piaf phoned and persuaded him to fly back to New York. Tragically, the plane on which he was returning crashed, killing everyone on board. Of Cerdan's death, in October of 1949, Piaf biographer Monique Lange declared, "It marked the beginning of her decline, of the period when she fell completely apart."

Throughout the 1950s Piaf appeared in films and had continued success as a performer and recording artist. But these successes were interspersed with periods of illness, drug use, and mental instability. In September of 1952 she married the singer Jacques Pills—an arrangement that soon ended in divorce. In the late 1950s a series of car accidents pushed her further into a dependence on morphine and other painkillers. In Piaf, Lange reported, "At the end of her life, when she was practically incapable of even getting up on stage, she had to have an injection in order to sing."

Despite rumors that she had died, by the late 1950s Piaf's career was once again on the upswing. Her 1959 recording "Milord" was one of her biggest hits, as was "Non je ne regrette," released in 1960. On December 29, 1960, she made a triumphant appearance at Paris's Olympia Theater, proving she still retained the adulation of France. She followed up these achievements by going on tour.

8

Unfortunately Piaf's renewed success did not last. Though she fell in love with and married the young French singer Theo Sarapo, her health was still declining. She died on October 10, 1963, leaving the world feeling the loss of its "La Mome Piaf."

Selected discography

At the Paris Olympia, EMI, 1990.The Voice of the Sparrow: The Very Best of Edith Piaf, Capitol, 1991.At Carnegie Hall, Capitol.The Best of Edith Piaf, Capitol.The Best of Edith Piaf, Volume 2, Capitol.L'Integrale (Complete Recordings) 1936-1945, Polydor.Master Series, Polydor.Piaf, Capitol.Piaf: Her Complete Recordings, 1946-1963, Angel.

Sources

Crosland, Margaret, Piaf, G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1985.Lange, Monique, Piaf, Seaver Books, 1981.Piaf, Edith, The Wheel of Fortune, Chilton Books, 1965.—Jordan Wankoff

9